ABSTRACT

This systematic review aims to verify whether tools designed to assess Ayres Sensory Integration constructs take into account the basic principles of current early childhood intervention approaches, namely the family-centered approach, child and family routines, and natural contexts. This systematic review was based on a standard protocol constructed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) statement and included 323 publications. From these publications, we identified seven sensory integration assessment instruments for children up to 6 years old which are compatible with recommended early intervention practice. This study identified the instruments for sensory integration assessment in young children and related them with current principles of early childhood approaches. The findings may help researchers and clinicians choose instruments.

Introduction

Early identification and intervention for developmental disorders, delays, or vulnerabilities are critical to the well-being of children and their families and fall under the responsibility of health and education services and professionals (Lipkin et al., Citation2020). According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), educational and health areas have made significant progress in early screening, assessment, and intervention of children with developmental and behavioral disorders and issues (Lipkin et al., Citation2020). Developmental screening of children without known developmental risks should emphasize the role of the family, the behavior of the child in daily activities and routines, and the various contexts where these activities and routines take place (home, kindergarten, and community) (Division for Early Childhood DEC, Citation2014). In Bronfenbrenner’s ecological perspective of human development and learning, the family is viewed as the most proximal influence in child development. Thus, the family has significant opportunities to influence their children’s development and growth (Bruder, Citation2000; Colyvas, Sawyer, & Campbell, Citation2010). Family routines are generally considered positive experiences, and natural contexts represent a source of learning and developmental opportunities for children and their families (Pereira, Jurdi, Reis, & Sousa, Citation2022).

The family-centered approach is extensively established as the recommended model of professional practice in Early Childhood Intervention (ECI) (McCarthy & Guerin, Citation2022). ECI has been defined as a system of coordinated services and resources for young children (ages 0 to 6) with disabilities or at risk for developmental delay and their families (Division for Early Childhood DEC, Citation2014). Thus, any early intervention program should include a family-centered approach, assuming that each family has its own competences that arise from the family’s abilities, talents, possibilities, values, and expectations (Dunst, Trivette, & Hamby, Citation2007; Pereira & Serrano, Citation2014; Swanson, Raab, & Dunst, Citation2011). According to the Division for Early Childhood (Division for Early Childhood DEC, Citation2014), professionals should consider aspects such as: including family members to make decisions and work together; interventions focused on functionality (e.g. involvement, autonomy, and social relationships) in their natural contexts; the priorities of the child and the family should be seen as goals to be achieved by the team, when they are related to the participation of the child in daily life activities; the routines of the child and family should be considered as natural opportunities for assessment and intervention; professionals should empower and make families co-accountable so that they can support the development of their children with the greatest possible parenting competence; intervention and assessment practices should be mindful of the priorities and diversity of each family. In accordance with these recommendations, the implementation of a family-centered approach in ECI has four components (Dalmau et al., Citation2017): (a) adoption of an ecological and systemic approach, (b) consideration of the importance of the natural environments of families, (c) family empowerment, and (d) collaborative partnership with families. One of the models that inspired this change is the routines-based model (McWilliam, Citation2010). This model focuses on children’s functioning in everyday routines and on family concerns, priorities, and competences (McWilliam et al., Citation2020). ECI aims to empower children and their environments in order to ensure children’s full participation and development in their natural settings. In this sense, it is particularly relevant not only to consider the underlying complexity of the conceptions and assessment practices in ECI but also to consider the need to deepen our understanding of each family’s daily challenges. Furthermore, the assessment instruments used must be adjusted to the diversity of families supported by ECI, instruments that should include the active and interactive participation of professionals and families in order to make possible the development of a shared and holistic vision of the child (Pereira, & Serrano, Citation2014). Practices for the assessment of children at early ages emphasize the practices of an authentic assessment (Bagnato, Citation2008). Authentic assessment is a process of evaluating the functional competence of children in their natural contexts (e.g. home and community) and must reflect the reality of the child and family. Authentic assessment relies on the observations, reports, and perceptions of familiar and knowledgeable caregivers in a child’s life (Bagnato, Goins, Pretti-Frontczak, & Neisworth, Citation2014; Macy, Bagnato, & Weiszhaupt, Citation2019). Taking into account the results of the evaluation, professionals should plan the intervention adjusted to the characteristics, needs, and priorities of the family and child (Macy, Bagnato, & Weiszhaupt, Citation2019).

Considering the above-mentioned considerations, ECI plays a fundamental role in preventing negative results and maximizing developmental and learning opportunities. Moreover, it is well accepted that all young children need access to equitable opportunities to enable developmental screening of early identification of delay, risk, vulnerabilities, or disabilities (Smythe, Zuurmond, Tann, Gladstone, & Kuper, Citation2021). The process of conducting a developmental screening involves gathering information for making decisions about the need for a deeper and more comprehensive assessment. The AAP recommends developmental screening for all children in the early years of life, in order to guide families to the most appropriate services for the follow-up of their children (Lipkin et al., Citation2020).

Childhood sensory integration difficulties have been studied and treated by occupational therapists since the 1960s, when the work of Dr. A. Jean Ayres (Citation1969, Citation1972) brought new understanding to child development. Vulnerabilities in terms of sensory integration (SI) have been described extensively in the literature for their negative influence on the participation of children in their daily occupations and routines, including sleep, feeding, toileting, learning, play, and socialization (Appleyard et al., Citation2020; Ayres, Citation1969; Baranek et al., Citation2019; Lane, Leão, & Spielmann, Citation2022; Mulligan, Schoen, Miller, Valdez, & Magalhaes, Citation2019; Pfeiffer, May-Benson, & Bodison, Citation2018; Schaaf et al., Citation2014; Zobel-Lachiusa, Andrianopoulos, Mailloux, & Cermak, Citation2015). SI also contributes to children’s ability to regulate behavior, based on the needs and expectations of the surrounding environment (Mulligan, Douglas, & Armstrong, Citation2021). The Ayres Sensory Integration (ASI®; Ayres, Citation1972) postulates how the brain processes sensory input to produce desired motor and behavioral responses. SI refers to the ability to detect, modulate, and process sensory information from one’s own body and from the environment and makes it possible to respond appropriately to meet the demands of everyday life (Ayres, Citation1972; Mulligan et al., Citation2018). Ayres identified basic sensory functions that underlie development and participation: sensory discrimination, sensory-based postural-ocular-bilateral functions, sensory-based praxis, and sensory reactivity. Ayres’s model of SI processing shows how the interactions among the sensory systems (auditory, vestibular, proprioceptive, tactile, and visual) contribute to increasingly complex behaviors (Bundy & Lane, Citation2020). For example, rest and sleep are documented to be affected most by sensory reactivity (Lane, Leão, & Spielmann, Citation2022); play and social participation are affected by sensory reactivity, sensory discrimination, somatopraxis, and vestibular bilateral integration (May-Benson et al., Citation2020; Smith-Roley et al., Citation2015); activities of daily living such as dressing/undressing require adequate sensory discrimination to develop body awareness and thoughtful planning and execution of motor skills (Schaaf et al., Citation2014); atypical defecation habits are associated with issues in sensory reactivity (Beaudry-Bellefeuille, Lane, & Lane, Citation2019).

In recent updates to Ayres’s original work (ASI®), Bundy and Lane (Citation2020) provide a schematic representation of sensory integrative dysfunction highlighting two main constructs: sensory modulation dysfunction and dyspraxia (sensory discrimination/praxis deficits). Sensory modulation dysfunction, also known as sensory reactivity dysfunction, refers to exaggerated (either hyper-reactive or hypo-reactive) responses to sensation which interfere with engagement in daily activities (Bundy & Lane, Citation2020). Dyspraxia refers to difficulty planning new motor actions and is thought to be associated with deficits in vestibular, proprioceptive, or tactile discrimination. Clinically, children with sensory-based dyspraxia may present poor postural-ocular control, poor sensory discrimination, and poor body scheme which can all impact engagement in occupations (Bundy & Lane, Citation2020; Lane et al., Citation2019).

Overall, young children with early sensory issues are more likely to experience developmental challenges by school age (Chen, Sideris, Watson, Crais, & Baranek, Citation2023). Consequently, the reciprocal relationship between SI and development/occupational participation reinforces the need and importance of early identification in order to minimize the impact of sensory vulnerabilities on development, self-care, engagement in play, sleep, emotion regulation, and school participation. Briefly, the screening and identification of SI challenges is crucial for referral to the appropriate early childhood intervention services (Critz, Blake, & Nogueira, Citation2015).

Researchers have identified a high prevalence of SI difficulties among children with and without diagnosis. As many as 88% of the children with disabilities, 96% of the children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), 40% to 50% of the children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and 39% to 52% of the infants born preterm are reported to have SI challenges (Bevans, Piller, & Pfeiffer, Citation2020; Yeung & Thomacos, Citation2020). Recent research has identified that 5% to 20% of the children without diagnosed disabilities have difficulties in SI (Flanagan, Schoen, & Miller, Citation2019; Galiana-Simal et al., Citation2020; Mulligan, Schoen, Miller, Valdez, & Magalhaes, Citation2019; Pfeiffer, May-Benson, & Bodison, Citation2018). However, commonly used developmental screening tools focus on developmental milestones and this is not a reliable way to identify more subtle problems such as SI dysfunction. Furthermore, better identification and acknowledgment of infant’s issues may lead to a more comprehensive understanding of children’s behavioral issues when they participate in daily activities and routines (Gourley, Wind, Henninger, & Chinitz, Citation2013). According to Thomas, Bundy, Black, and Lane (Citation2015), early identification and intervention could minimize the impact of sensory difficulties on attachment, emotion regulation, and, later engagement in play, self-care, sleep, and school participation. Omairi, Mailloux, Antoniuk, and Schaaf (Citation2022) show that improvements in sensory integration not only help children participate in activities and tasks more successfully but also assist families in completing tasks and participating in chosen activities. Schaaf et al. (Citation2014)show that improvements in sensory modulation and praxis skills may underlie the gains seen in the participation in activities of daily living and social skills. These studies (Omairi, Mailloux, Antoniuk, & Schaaf, Citation2022; Schaaf et al., Citation2014) used Occupational Therapy using Ayres Sensory Integration®, which considers both the underlying sensory issues and the daily participation challenges at all levels of the intervention process (assessment, clinical reasoning, goal setting, treatment planning, direct treatment, adaptations to daily routines, etc.).

Development is continually shaped and guided by transactions between the child and the context, so it is important to combine bottom-up approaches with top-down approaches throughout the entire intervention process. In the bottom-up approach, the focus of the assessment is to analyze the body function and structure-level skill components (such as underlying sensory integration components) and in the top-down assessment approach the focus is the activity and participation (Lalor, Brown, & Murdolo, Citation2016). Both bottom-up and top-down focus is needed; the bottom-up approach for the measurement of underlying factors (proximal outcomes) that may influence successful participation and the top-down approach for the assessment of participation-based challenges (distal outcomes) (Bundy & Lane, Citation2020; Schaaf et al., Citation2014). ASI® postulates that sensorimotor abilities provide a foundation for higher-level skills and behaviors, including daily living skills, socialization, playing, and learning. Therefore, it is important to assess the underlying reasons (body function and structure-level skill components) for why a child may be experiencing difficulties with occupations, such as participating in home and community, all the while considering the values, needs, and priorities of the family and child. In this sense, health professionals must use the most appropriate methods to help caregivers to 1) learn about and understand their child’s difficulties; 2) improve specific areas of vulnerabilities in their child’s performance that are of concern to them; 3) use or maximize child strengths. Caregivers of children with sensory integration difficulties have reported a desire to develop a better understanding of their child’s behavior and to learn supportive strategies to be able to help their child (Miller-Kuhaneck & Watling, Citation2018).

In summary, screening tools to identify sensory issues at an early stage, compatible with best practice recommendations in early childhood intervention, are needed. Such tools are required to obtain valid and reliable information capable of substantiating decision-making so that professionals are legitimately entitled to refer the child to specialized services (Bagnato, Citation2008). Knowing which tools are available for this purpose is crucial. Eeles et al. (Citation2013) described in their systematic review that SI is measured by more than 30 instruments. However, only three assessments can be used to evaluate SI within the first 2 years of life. In the systematic review carried out by Shahbazi and Mirzakhani (Citation2021), nine SI assessment tools for children aged between 0 and 14 years were identified between 1990 and 2019. According to Jorquera-Cabrera, Romero-Ayuso, Rodriguez-Gil, and Triviño-Juárez (Citation2017), fifteen tests are available and supported by psychometric studies; nine of the tests can be applied to children in preschool to grade 12; three of them are designed solely for preschool children, and most tests are only available in English and are designed for the US population.

According to the practices recommended by Macy, Bagnato, and Weiszhaupt (Citation2019), professionals should use instruments that capture the child’s behaviors in their routines with information provided directly from families and caregivers, considering the child’s natural contexts. In addition to being aware of the basic principles of early childhood intervention, professionals must assess the child using instruments and procedures that encompass several areas of development such as sensory, motor, and behavior. In this sense, it is important to include SI assessment methods and instruments, which consider family routines and contexts (Gourley, Wind, Henninger, & Chinitz, Citation2013).

This systematic review aims to identify and verify whether tools designed to assess SI abilities in young children take into account the basic principles of current early childhood intervention approaches, namely the family-centered approach, child and family routines, and natural contexts.

Methods

This systematic review aims to answer the following questions: Which tools exist, for use by early childhood professionals, for the assessment of ASI® constructs in young children (0–6 years)? How do these assessment tools relate to current principles of early childhood intervention, namely family-centered approach, child and family routines, and natural contexts? Considering the descriptive nature of the study, the PEO model (population, exposure, and outcome) for systematic review has been used to formulate the research questions. The elements of the PEO question are as follows: 1) population: children from 0 to 6 years old; 2) exposure: assessment of SI functions; and 3) outcomes or themes: relationship between assessment of SI functions and family-centered approach, child and family routines, and natural contexts. The population of interest was children aged 0–6 years because the Portugal Early Childhood Intervention System supports children up to 6-years old and their families (Leite & Pereira, Citation2019). The study was approved by the research Ethics Committee of the University of Minho (CEICSH Process 123/2020).

Search Strategy

The study structure was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review (PRISMA) (Moher et al., Citation2009). We conducted a search in PubMed (271), SCOPUS, namely, Academic Search Ultimate and APA PsycInfo (773), EBSCO (260), and WEB OF SCIENCE, namely, Core Collections (486) databases, and included all citations from the inception of each database through April 2022. In order to limit our search to relevant articles, we used the following search strategy and keywords: (“infant” OR “child” OR “pediatrics”) AND (“Outcome and Process Assessment” OR “assessment” OR “evaluation”) AND (“Sensory Processing” OR “Sensory Integration” OR “Sensory Modulation” OR “Praxis” OR “Sensory Discrimination”). The chosen terms were based on a preliminary review of the most employed terms in studies using tools for assessment of Sensory Processing/Integration. The search strategy and the chosen keywords were developed and revised by the first and last authors.

Data Selection

Based on our research questions, we set the inclusion criteria to be as follows: 1) articles published in peer review journals, written in English, Spanish, or Portuguese and have full text available through our university providers or the internet; 2) publication dates ranging from 2007 to 2022; 3) focused on assessing SI in children aged between 0 and 6 years (regardless of gestational age at birth); 4) SI assessment tools with reported psychometrics properties (for example, questionnaires created by clinicians and not submitted to validity studies were not included); 5) compatible with one or more constructs of ASI® (sensory reactivity, sensory discrimination, postural-ocular, and bilateral integration, praxis; Mailloux et al., Citation2011); and, 6) include consideration of current principles of early intervention, namely family-centered approach, child and family routines, and natural contexts. We opted for articles published from 2007 onwards because in 2007 Parham and colleagues (Parham, Ecker, Kuhaneck, Henry, & Glennon, Citation2007) identified the core elements of Ayres sensory integration intervention in the ASI® Fidelity Measure. This tool guides practice and research to maintain coherence to the core principles of ASI (Parham, Ecker, Kuhaneck, Henry, & Glennon, Citation2007). Publications prior to 2007 often erroneously depict ASI®.

Publications were excluded if 1) studies conducted with animals; 2) assessment tools principally focused on measuring a child’s motor ability (if more than 70% of the items referred to motor skills); 3) assessment tools aimed mainly at measuring behavior, cognition, communication, or a child’s relationship with parents, family members, peers, and others, and 4) no clear mention of SI/processing assessment tools.

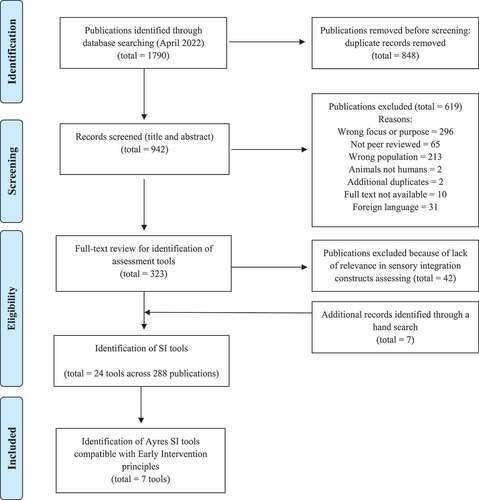

Selection of publications and assessment tools was done using a three-phase process. The goal of the first phase was to identify publications, based on the reading of the title and abstract, that fulfilled our first three inclusion criteria. Two reviewers (independently and blinded to each other’s decision) screened all records for eligibility (using Rayyan QCRI). In case of disagreement, a third researcher was involved to decide if the article should be included. In the second phase, based on full-text reading of the retained articles, a list of all the identified SI assessment tools was created. At this phase, our fourth inclusion criteria were verified, and the psychometric properties and method of administration of each tool were identified. In the third phase, we examined the details of each tool to identify those that met all of the remaining inclusion criteria (compatible with one or more constructs of ASI®; include consideration of current principles of early intervention). Details of article selection (including reasons for exclusion) were registered using Rayan QRCI and reported in the PRISMA Flow Diagram (). Given that the aim of the review was to identify and posteriorly analyze assessment tools, we did not consider evaluating the quality of the studies as such, as this was not relevant to our research question.

Results

Phase 1: Selection of Publications to Be Reviewed

Initially, 1790 articles were identified using the search strategy. Of these, 848 duplicate articles were removed, and a total of 942 articles were screened by title and abstract for our first 3 inclusion criteria by two reviewers (conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer). Through this process, 323 articles were retained and 619 articles were excluded. Articles were excluded for the following reasons: 2 were studies conducted with animals; 2 articles were additional duplicates; 10 articles did not have full text available through our providers or the internet; 213 articles collected data from populations aged over 6 years; 296 studies did not focus on SI assessment; 31 articles were not written in English, Spanish, or Portuguese; and, 65 studies had not been published in peer reviewed journals.

Phase 2: Sensory Integration Assessment Tools Identified

The full text of the 323 retained articles was reviewed to confirm the inclusion criteria of phase 1 and verify our fourth criteria, SI assessment tools with reported psychometric properties. We removed 42 articles because they did not mention SI assessment tools. In the process of full-text reading, we identified seven additional publications, which met our first four inclusion criteria. Finally, 288 articles were retained from which we identified 24 assessment tools and a data extraction table was used to organize the information about each tool (). A short description, the method of administration, additional information, as well as the psychometric properties of the instruments are included in the table.

Table 1. Sensory Integration Assessment Tools identified in Phase 2.

Among the tools identified in this phase the most commonly used include the Sensory Integration and Praxis Test (SIPT, Ayres, Citation1989), the Test of Sensory Function in Infants (TSFI; DeGangi & Greenspan, Citation1989), the Sensory Profile, or the more recent Sensory Profile 2 version (SP or SP 2; Dunn, Citation1999, 2006, Dunn, Citation2014), the Sensory Processing Measure (SPM; Parham, Ecker, Kuhaneck, Henry, & Glennon, Citation2007), the Sensory Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ; Baranek, David, Poe, Stone, & Watson, Citation2006), the Sensory Processing 3-Dimensions Assessment (SP-3D Assessment; Mulligan et al., Citation2018) and the Sensory Processing Assessment (SPA; Baranek, Boyd, Poe, David, & Watson, Citation2007).

Phase 3: Sensory Integration Assessment Tools Meeting All Criteria

We examined the details of the 24 tools identified in phase 2 and screened them for the remaining inclusion criteria (compatible with the constructs of ASI®; include consideration of current principles of early intervention) in order to identify ASI® assessment tools that incorporate concerns reported by the family in daily routines and in natural contexts.

In accordance with our established criteria concerning the consideration of current principles of early intervention, we excluded some of the most commonly used tools such as SIPT, TSFI, SP-3D Assessment, and SPA. Other assessment tools referenced in the articles were also excluded as they did not consider current principles of assessment in early intervention, such as DeGangi–Berk Test of Sensory Integration (DeGangi–Berk Test of SI; DeGangi & Berk, Citation1983), Preschool Imitation and Praxis (PIPS; Vanvuchelen, Roeyers, & Weerdt W, Citation2011), Test of Ideational Praxis (TIP; May-Benson & Cermak, Citation2007), Sensory Adventure Measure (SAM; Liberman, Sevillia, Shaviv, & Bart, Citation2021), Sensory Processing Scale Assessment (SPS Assessment; Schoen, Miller, & Sullivan, Citation2014), Evaluation in Ayres Sensory Integration® (EASI®; Mailloux, Parham, Roley, Ruzzano, & Schaaf, Citation2018), Comprehensive Observations of Proprioception (COP; Blanche, Bodison, Chang, & Reinoso, Citation2012), Sensory Integration Clinical Observations (SI Clinical Observations; May-Benson, Citation2015), Gravitational Insecurity Assessment (GI Assessment; May-Besson & Koomar), Miller Assessment for Preschoolers (MAP; Miller, Citation1982), Tactile Defensiveness and Discrimination Test-Revised (TDDT-R; Baranek, Citation2010), and Postrotary Nystagmus Test (PRN Test; Mailloux et al., Citation2014). The Pediatric Eating Assessment Tool (PediEAT; Thoyre et al., Citation2014) is a tool that provides vital information related to the mealtime routine in the assessment of children with feeding disorders, but we excluded the instrument because only 13 of the 78 items potentially assess sensory issues and compatibility with ASI® is unclear.

In summary, we excluded in Phase 3 the tools that used a structured assessment, based on carrying out instructions and tasks as well as tools that involved the observation of the child in the exploration of materials/toys provided by the therapist. We therefore retained seven tools that are compatible with one or more of the constructs of ASI®, are based on information collected from parents or a close caregiver, take into account the children’s daily activities, and consider the natural contexts of the family: SPM (Parham, Ecker, Kuhaneck, Henry, & Glennon, Citation2007), SP (Dunn, Citation1999, Citation2006, Dunn, Citation2014), Participation and Sensory Environment Questionnaire (P-SEQ; Pfeiffer, Piller, Bevans, & Shiu, Citation2019), SEQ (Baranek, David, Poe, Stone, & Watson, Citation2006), Sensory Processing Scale Inventory (SPSI; Schoen, Miller, & Sullivan, Citation2017), Toileting Habit Profile Questionnaire-Revised (THPQ-R; Beaudry-Bellefeuille, Bundy, Lane, Ramos-Polo, & Lane, Citation2018) and Sensory Rating Scale (SRS; Provost & Oetter, Citation2009). We created two data extraction tables in this phase: lists the publications that mention the retained tools; describes the SI tools (areas of SI, instructions, scoring, number of items, time to administer and link to family routines and natural contexts).

Table 2. Studies including the Assessment Tool identified in Phase 3.

Table 3. Sensory Integration Assessment Tools identified in Phase 3.

See supplemental data file for full references of the mentioned studies.

The seven tools retained in Phase 3 consist of items that ask about a child’s responses to sensory experiences in the context of everyday life activities and are rated in terms of the frequency of the behavior on a 4 or 5-point Likert type scale (SPM, SP, P-SEQ, SEQ, and SRS) or a binary scoring system (THPQ-R and SPSI).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify assessment tools compatible with ASI® constructs that also include consideration of the basic principles of current early childhood intervention approaches, namely the family-based approach that contemplates routines and natural contexts. This review included a total of 323 articles, from which we identified 7 assessment tools. The specific psychometric properties of all the tools identified in this review are reported and need to be considered by the professionals and institutions who choose to use them.

The SPM is anchored in ASI® and items provide information on reactivity and discrimination vulnerabilities within sensory systems, as well as information on praxis and postural control. The SPM links SI with the child’s daily performance but it is organized and scored around the sensory systems and sensorimotor abilities. An adequate interpretation of the results requires knowledge about SI Theory and its impact on the child’s performance and participation in activities of daily life (Parham, Ecker, Kuhaneck, Henry, & Glennon, Citation2007).

The SP, based on the Sensory Processing Model (Dunn, Citation2014), links sensory processing with the child’s daily life activities and also involves parents in the assessment process. The model devised by Dunn includes four patterns of sensory responsiveness: low registration, sensation seeking, sensory sensitivity, and sensory avoidance. The questionnaire describes behaviors or responses to various sensory experiences within the different sensory systems and scores identify the sensory dysfunction patterns identified in the model (Dunn, Citation2014). Although these patterns are not fully compatible with ASI®, some aspects overlap and since caregiver perspective is included, we decided to include the SP in our selection of tools.

The SRS fulfills our selection criteria as it measures sensory hyper-reactivity in daily situations in children up to 3 years (e.g., “dislikes being held or cuddled, seems irritable, seems to be a difficult child”) (Provost & Oetter, Citation2009). Another tool, the SPSI also includes items that are based on observations of children within their daily activities. The SPSI includes the constructs of sensory over-reactivity and under-reactivity and therefore the tool was retained (Schoen, Miller, & Sullivan, Citation2015).

The SEQ includes the reactivity construct of ASI® and is designed specifically to identify sensory issues in young children with autism or those at risk for autism (Baranek et al., Citation2019). The P-SEQ (Pfeiffer, Piller, Bevans, & Shiu, Citation2019) also includes the reactivity construct and is intended to assess parent or caregiver perceptions of the degree to which the sensory environment impacts young children’s participation in home-based activities and is therefore consistent with the family-centered approach principles. Finally, we identified the THPQ-R (Beaudry-Bellefeuille, Bundy, Lane, Ramos-Polo, & Lane, Citation2018), a caregiver questionnaire designed to identify challenging defecation behaviors potentially related to sensory reactivity or discrimination issues.

In summary, the instruments described above are completed by the child’s caregivers and include one or more constructs of ASI®. The minimum testing time was 5 to 10 min for the SP 2, and the maximum testing time was 20 min for most instruments. These tools are meant to be interpreted by health professionals with expertise in SI; occupational therapists have developed expertise in the assessment and intervention of children who have difficulties in accomplishing everyday activities linked to SI dysfunction (Bodison & Parham, Citation2018).

In accordance with the aim of our review we excluded some of the most frequently mentioned assessment tools, namely the SIPT and others such as the TSFI, SP-3D Assessment, and SPA. Although the SIPT is the “gold standard” test for assessing SI functions (sensory discrimination, praxis, and postural control), it does not specifically include considerations related to the family, context, or routines of the child. The SIPT consists of 17 subtests designed to assess four overlapping areas: visual form and space perception, tactile discrimination, praxis and vestibular and proprioceptive processing. The SIPT is usually administered by an occupational therapist with post-graduate training in ASI® (Ayres, Citation1989). Similarly, the SP-3D Assessment is designed to assess sensory functions and can be used by trained occupational therapists (Mulligan et al., Citation2018). The TSFI is often used in the assessment of SI and reactivity in infants (ages 4–18 months) and includes 5 subdomains (reactivity to tactile deep pressure, adaptative motor functions, visual-tactile integration, ocular-motor control, and reactivity to vestibular stimulation). However, once again the administration of the items is performed by the occupational therapist and consideration of family, contexts, and routines is lacking (DeGangi & Greenspan, Citation1989). Finally, the SPA is a play-based observational assessment used to identify approach/avoidance behaviors in response to novel sensory toys, orienting/habituating responses to sensory stimuli, and initiation of novel action strategies, as well as stereotyped behaviors. It is also a performance-based test that requires the administration to be performed preferably by an occupational therapist specializing in the area of SI (Baranek, Boyd, Poe, David, & Watson, Citation2007). Although these tests all have good to excellent validity and reliability and may be useful to understand underlying sensory issues impacting daily life, they are not specifically designed to identify the impact that sensory issues may have in daily life and were therefore excluded.

Recent recommendations in early childhood intervention have promoted considerable changes in the assessment of young children, highlighting the family-centered approach and the valorization of routines within the family’s life contexts, thus embracing a holistic and ecological vision (Division for Early Childhood DEC, Citation2014). According to Dunst, Trivette, and Hamby (Citation2007), the family-centered approach promotes beliefs of family self-efficacy, leading to more parental engagement in the assessment and intervention of the child, which leads to better results and sense of mutual trust.

In this regard, it is of particular importance to use assessment and screening tools that contemplate and enhance active listening, as well as, the concerns and the priorities of the family regarding the child’s functioning in significant contexts. Several authors state that current practices in assessment do not adapt to the variability of children’s characteristics in early age, do not appear to detect the most subtle difficulties and vulnerabilities of young children, and do not focus on the child’s functioning in routines in natural contexts (Bagnato, Goins, Pretti-Frontczak, & Neisworth, Citation2014; Lee, Bagnato, & Pretti-Frontczak, Citation2016; Macy, Bagnato, & Gallen, Citation2016). According to ECI professionals, the identification of family concerns and priorities is an integral and crucial part of the assessment process. In this regard, the family must define and prioritize their concerns based on their experience in different daily routines (Pereira, Jurdi, Reis, & Sousa, Citation2022).

Considering the fragilities of the traditional assessment process in early childhood intervention approach and the recommended practice by the National Association for the Education of Young Children and the Division of Early Childhood Intervention (Division for Early Childhood DEC, Citation2014), a new concept is proposed; authentic assessment (Bagnato, Citation2008). So, the assessment tools must capture the child’s behavior in routines through direct information from the family and other caregivers, and the results should be used to guide the intervention process (Bagnato, Citation2008).

With this in mind, our aim was to identify assessment tools of the ASI® framework that consider the above mentioned principles in early childhood intervention. In recent decades, SI vulnerabilities have been increasingly researched and discussed in the literature together with the potentially negative effects that SI issues can have on practically every aspect of a child’s life (sleeping, feeding, toileting, hygiene, self-regulation, learning, attachment, etc.), family functioning and long-term development (Chen, Sideris, Watson, Crais, & Baranek, Citation2023). Early identification of SI issues along with an understanding of which moments of the child’s and family’s daily routine need support, is crucial (Parham, Ecker, Kuhaneck, Henry, & Glennon, Citation2007). Through early childhood intervention that incorporates education, modeling, collaboration, and active problem-solving, caregivers become better observers and improve their ability to make their own modifications and adaptations in sensory aspects of daily activities (Dunst et al., Citation2014). This process requires a thorough understanding of the underlying sensory challenges as well as a consideration of the challenges in daily routines. Therefore, professionals should collaborate with caregivers to identify sensory-related challenges within the daily routines and contexts in order to develop strategies to optimize the daily environment and activities to improve comfort and active participation for young children with sensory challenges (Bundy & Lane, Citation2020). ASI® can help caregivers incorporate the appropriate types of activities into daily routines and modify aspects such as the timing and intensity of the sensory aspects of the activity to enhance the development of sensory integrative functioning.

In this sense, screening tools to determine whether sensory concerns are present and how they interfere with a child and family’s routines are needed. This information is very important to guide and refer parents to appropriate services, namely, the need for a more in-depth assessment in occupational therapy using an SI approach.

The profession of occupational therapy has always been linked to promoting participation in daily occupations and has developed expertise in the assessment and intervention of SI issues. The administration of SI assessment tools provides detailed information regarding preferences and tolerance to various activities, interactions, and environmental stimuli relative to processing of sensory input (e.g., vestibular, tactile, proprioceptive, and visual). Most tools require a detailed analysis by an occupational therapist specialized in ASI® and may not always fully capture the challenges the child and family experience in their daily routines. Additional tools, designed to specifically explore daily participation from an ASI® perspective are needed to better document daily life challenges and the possible links with underlying sensory issues. Furthermore, client-centered practice, the inclusion of assessments and interventions focused on functionality in natural contexts, therapeutic goals based on the client’s participation priorities and mindfulness toward diversity is well established within the profession of occupational therapy (Pollock, Citation1993).

Johnson-Ecker and Parham (Citation2000), state that caregiver questionnaires are useful clinical assessment tools to assess children with known or suspected SI difficulties. In addition, caregivers provide important information about a child’s behavior across multiple contexts, at various times in the daily routine. Our review identified several sensory questionnaires that are available for evaluating young’s children SI concerns, including the SP, the SP2 (Dunn, Citation2014), SPM (Parham, Ecker, Kuhaneck, Henry, & Glennon, Citation2007), the SRS (Provost & Oetter, Citation1993), the SEQ (Baranek, David, Poe, Stone, & Watson, Citation2006) and the SPSI (Schoen, Miller, & Sullivan, Citation2014). These questionnaires can improve the ecological validity of examiner-administered tests and sustain a family-centered approach (Schoen, Miller, & Sullivan, Citation2014). We identified one questionnaire (THPQ-R; Beaudry-Bellefeuille et al., Citation2019) that focused on sensory reactivity and discrimination linked to toileting, an important activity of daily living. Identifying sensory concerns that may affect participation in key activities of daily living is important to guide intervention, however, most tools do not focus on daily occupations but rather on sensory systems and measure mainly sensory reactivity, representing but one construct of ASI®.

Schaaf et al. (Citation2014) state that tools are needed to ensure a comprehensive assessment of ASI®, which include the full array of sensory and motor factors that may influence function and participation. The same authors refer that assessment measures need to be developed to address a wider age range. Current recommendations for early identification of SI issues indicate that reliable and valid tools of SI and praxis for young children are essential, yet few adequate tools are available (Bundy & Lane, Citation2020). Furthermore, most of the assessment tools included in our review have been designed in North America and validated with North American samples; use of these tools in other cultures may require further validation.

The assessment tools identified in this review () are administered preferably by occupational therapists with expertise in sensory processing and integration. They involve caregivers in the assessment process and are helpful in obtaining information about the child’s performance in natural contexts to identify factors that challenge the child’s successful participation in daily activities. Nevertheless, one must keep in mind that early identification of neurodevelopmental problems is usually the responsibility of the pediatrician, by means of health supervision appointments and surveillance checkups (Oliveira, Citation2009). However, screening tests used by pediatricians focus on developmental milestones or red flags for specific developmental conditions such as autism (Lipkin et al., Citation2020; Zwaigenbaum et al., Citation2015) and consequently, subtle sensory issues that impact daily routines may be missed. For example, children with ASD commonly display unusual responses to sensory input that impact participation in daily activities such as feeding long before a formal diagnosis is made (Emond, Emmett, Steer, & Golding, Citation2010). Furthermore, sensory issues can limit or change the way families participate in various activities and routines (Kirby et al., Citation2019), potentially leading to a lack of exposure to beneficial enriched sensorimotor experiences. Given the benefits of early intervention, it becomes important to use screening tools that can be applied by pediatricians to identify children with sensory issues and problems participating in daily routines at an early age, so as to refer them to specialists before they skip developmental milestones and before clear diagnostic criteria for developmental disorders are present. The surveillance and screening of developmental disabilities can be performed by several professionals related to health and education. Specific efforts have focused on improving screening methods, such as incorporating developmental surveillance at 9, 18, and 30 months as well before the beginning of school (Lipkin et al., Citation2020). According to Oliveira (Citation2009) the family doctor is the professional in a privileged position due to regular contact with the child and his family. Thus, it is important to create and make available, culturally relevant and psychometrically sound tools for the early identification of sensory integration difficulties, taking into account the basic principles of current early childhood intervention approaches, namely the family-centered approach, child and family routines, and natural contexts. These tools should be available to all health and education professionals, who are in daily contact with children in various contexts. Early referral to occupational therapy for a comprehensive assessment of participation in daily routines as well as SI strengths and challenges can support an earlier diagnosis and, consequently, contribute to providing the most appropriate support or service to the child and family.

Limitations and Future Research

The systematic review included studies published in English, Portuguese, and Spanish language and according to specified search and inclusion criteria; tools used in studies published in other languages or outside of our search strategies and inclusion criteria may have been missed.

Conclusion

Understanding the relationship between SI and participation, development and behavior has important implications for clinicians and healthcare professionals working with young children. Screening for SI and participation issues and referring to specialists for comprehensive assessment and individually tailored intervention when needed may help tackle a broad range of participation, developmental and behavioral challenges early on, potentially changing atypical developmental trajectories toward more adaptive ones. The tools used in the screening and assessment of the child’s vulnerabilities have a significant impact on the decisions we make. Currently, pediatricians use screening tools that focus on developmental milestones or developmental conditions which may miss sensory and participation issues.

Existing tools to assess SI mainly evaluate children’s ability to organize, integrate, and react to sensory input. However, the degree to which SI challenges affect child’s participation in home and community contexts is underrepresented. Therefore, it is necessary to design new tools to assess SI vulnerabilities in children, considering the basic principles of current early intervention approaches, namely routines, natural context, and the family-based approach. Our review shows an increase in recent years in the number of tools available to measure SI functions, however most tools require a detailed analysis by an occupational therapist specialized in SI to assess the impact on daily participation and none of them are specifically designed to be used as screening tests by pediatricians and other health professionals.

Several important areas regarding assessment and future research in SI emerged from this review, in particular the importance of designing screening tools for early identification of SI and participation issues by pediatricians. Furthermore, therapists using ASI® must be knowledgeable of early intervention principles and carry out comprehensive assessments, which promote collaboration between parents and professionals because this can facilitate planning and contribute to individually tailored interventions for the child and family (Macy, Bagnato, & Weiszhaupt, Citation2019).

Author Contributions

All authors conducted the search of literature, reviewed the articles, and formal analysis. They also all contributed to the writing, review, and editing of the article.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Portuguese national funds through the FCT (Foundation for Science and Technology) within the framework of the CIEC (Research Center for Child Studies of the University of Minho) projects under the references UIDB/00317/2020 and UIDP/00317/2020. Cátia Lucas also thanks the FCT for the PhD scholarship BD.2020.07797. The authors would like to thank the Ângela Fernandes, occupational therapist, for her review of abstracts in the initial selection of articles.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abu-Dahab, S. M. N., Malkawi, S. H., Nadar, M. S., Al Momani, F., & Holm, M. B. (2014). The validity and reliability of the Arabic Infant/Toddler sensory profile. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 34(3), 300–312. doi:10.3109/01942638.2013.823474

- Adams, J. N., Feldman, H. M., Huffman, L. C., & Loe, I. M. (2015). Sensory processing in preterm preschoolers and its association with executive function. Early Human Development, 91(3), 227–233. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.01.013

- Ahmad, N. M., Kadar, M., Chai, S. C., Mohd Rasdi, H. F., Razab, R., & Dzalani-Harun, N. A. (2020). Adaptation, validation and reliability testing of sensory processing measure home form Malay version for children with autism. Jurnal Sains Kesihatan Malaysia, 18(1), 37–45. doi:10.17576/jskm-2020-1801-06

- Akarsu, R., Savas, M., Karali, F. S., & Çelik, Y. (2020). Evaluation of sensory processing skills of children with autism spectrum disorder. Turkiye Klinikleri Pediatri, 29(2), 47–56. doi:10.5336/pediatr.2019-71761

- Alcañiz-Raya, M., Chicchi-Giglioli, I. A., Marín-Morales, J., Higuera-Trujillo, J. L., Olmos, E., Minissi, M. E. … Abad, L. (2020). Application of supervised machine learning for behavioral biomarkers of autism spectrum disorder based on electrodermal activity and virtual reality. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 14(90). doi:10.3389/fnhum.2020.00090

- Alkhalifah, S. (2019). Psychometric properties of the sensory processing measure preschool-home among Saudi children with autism spectrum disorder: Pilot study. Journal of Occupational Therapy Schools & Early Intervention, 12(4), 401–416. doi:10.1080/19411243.2019.1683118

- Alkhalifah, S. M., AlArifi, H., AlHeizan, M., Aldhalaan, H., & Fombonne, E. (2020). Validation of the Arabic version of the two sensory processing measure questionnaires. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 78. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101652

- Alkhamra, R. A., & Abu-Dahab, S. M. N. (2020). Sensory processing disorders in children with hearing impairment: Implications for multidisciplinary approach and early intervention. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 136, 136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110154

- Allen, S., & Casey, J. (2017). Developmental coordination disorders and sensory processing and integration: Incidence, associations and co-morbidities. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 80(9), 549–557. doi:10.1177/0308022617709183

- Andelin, L., Reynolds, S., & Schoen, S. (2021). Effectiveness of occupational therapy using a sensory integration approach: A multiple-baseline design study. American Occupational Therapy Association, 75(6), 7506205030. doi:10.5014/ajot.2021.044917

- Anguera, J. A., Brandes-Aitken, A. N., Antovich, A. D., Rolle, C. E., Desai, S. S., Marco, E. J., & van Wouwe, J. P. (2017). A pilot study to determine the feasibility of enhancing cognitive abilities in children with sensory processing dysfunction. PloS One, 12(4), e0172616. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172616

- Angulo, R. F., Zuleta, N. M., Crissien-Quiroz, E., & Blumtritt, C. (2020). Sensory profile in children with autism spectrum disorder. Archivos Venezolanos De Farmacologia y Terapeutica, 39(1), 105–111. Retrieved from www.scopus.com/

- Anto Prakash, A. J., & Vaishampayan, A. (2007). A Preliminary Study of the Sensory Processing Abilities of Children with Cerebral Palsy and Typical Children on the Sensory Profile. Indian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 39(2), 27–34.

- Appleyard, K., Schaughency, E., Taylor, B., Sayers, R., Haszard, J., Lawrence, J. … Galland, B. (2020). Sleep and sensory processing in infants and toddlers: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(6). 7406205010p1–7406205010p12 doi:10.5014/ajot.2020.038182

- Armstrong, D. C., Redman-Bentley, D., & Wardell, M. (2013). Differences in function among children with sensory processing disorders, physical disabilities, and typical development. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 25(3), 315–321. doi:10.1097/PEP.0b013e3182980cd4

- Asher, A. V., Parham, L. D., & Knox, S. (2008). Interrater reliability of sensory integration and praxis tests (SIPT) score interpretation. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(3), 308–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.62.3.308

- Atchison, B. J. (2007). Sensory modulation disorders among children with a history of trauma: A frame of reference for speech-language pathologists. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 38(2), 109–116. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2007/011)

- Ausderau, K., Sideris, J., Furlong, M., Little, L. M., Bulluck, J., & Baranek, G. T. (2014). National survey of sensory features in children with ASD: Factor structure of the sensory experience questionnaire (3.0). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(4), 915–925. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1945-1

- Ayres, A. J. (1969). Deficits in sensory integration in educationally handicapped children. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 2(3), 160–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/002221946900200307

- Ayres, J. (1972). Types of sensory integrative dysfunction among disabled learners. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 26(1), 13–18. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5008164/

- Ayres, J. (1989). Sensory Integration and Praxis Tests. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

- Backhouse, M., Harding, L., Rodger, S., & Hindman, N. (2012). Investigating sensory processing patterns in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy using the sensory profile. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(6), 271–280. doi:10.4276/030802212X13383757345148

- Bagnato, S. (2008). Authentic assessment for early childhood intervention: Best practices (1ª ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Bagnato, S., Goins, D., Pretti-Frontczak, K., & Neisworth, J. (2014). Authentic assessment as “best practice” for early childhood intervention: National consumer social validity research. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 34(2), 116–127. doi:10.1177/0271121414523652

- Baranek, G. T. (2010). Tactile defensiveness and discrimination test – revised (TDDT-R). Unpublished manuscript.

- Baranek, G. T., Boyd, B. A., Poe, M. D., David, F. J., & Watson, L. R. (2007). Hyperresponsive sensory patterns in young children with autism, developmental delay, and typical development. American Journal of Mental Retardation: AJMR, 112(4), 233–245. doi:10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[233:HSPIYC]2.0.CO;2

- Baranek, G. T., Carlson, M., Sideris, J., Kirby, A. V., Watson, L. R., Williams, K. L., & Bulluck, J. (2019). Longitudinal assessment of stability of sensory features in children with autism spectrum disorder or other developmental disabilities. Journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 12(1), 100–111. doi:10.1002/aur.2008

- Baranek, G. T., David, F. J., Poe, M. D., Stone, W. L., & Watson, L. R. (2006). Sensory experiences questionnaire: Discriminating sensory features in young children with autism, developmental delays, and typical development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 47(6), 591–601. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01546.x

- Baranek, G. T., Watson, L. R., Boyd, B. A., Poe, M. D., David, F. J., & McGuire, L. (2013). Hyporesponsiveness to social and nonsocial sensory stimuli in children with autism, children with developmental delays, and typically developing children. Development and Psychopathology, 25(2), 307–320. doi:10.1017/S0954579412001071

- Barnes, K. J., Vogel, K. A., Beck, A. J., Schoenfeld, H. B., & Owen, S. V. (2008). Self-regulation strategies of children with emotional disturbance. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 28(4), 369–387. doi:10.1080/01942630802307127

- Bar-Shalita, T., Vatine, J. J., & Parush, S. (2008). Sensory modulation disorder: A risk factor for participation in daily life activities. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 50(12), 932–937. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03095.x

- Bart, O., Shayevits, S., Gabis, L. V., & Morag, I. (2011). Prediction of participation and sensory modulation of late preterm infants at 12 months: A prospective study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(6), 2732–2738. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.05.037

- Beaudry-Bellefeuille, I., Bundy, A., Lane, A., Ramos-Polo, E., & Lane, S. (2018). The toileting habit profile questionnaire: Examining construct validity using the rasch model. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 82(4), 235–247. doi:10.1177/0308022618813266

- Beaudry-Bellefeuille, I., Lane, A., Chiu, S., Oldmeadow, C., Ramos-Polo, E., & Lane, S. (2019). The Toileting habit profile questionnaire-revised: Examining discriminative and concurrent validity. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 12(3), 311–322. doi:10.1080/19411243.2019.1590756

- Beaudry-Bellefeuille, I., Lane, S. J., & Lane, A. E. (2019). Sensory integration concerns in children with functional defecation disorders: A scoping review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(3). 7303205050p1-7303205050p13 doi:10.5014/ajot.2019.030387

- Beaudry-Bellefeuille, I., Lane, S., & Ramos-Polo, E. (2016). The Toileting Habit Profile Questionnaire: Screening for sensory-based toileting difficulties in young children with constipation and retentive fecal incontinence. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 9(2), 163–175. doi:10.1080/19411243.2016.1141081

- Benjamin, T. E., Crasta, J. E., Suresh, A. P., Alwinesh, M. J., Kanniappan, G., Padankatti, S. M. … Russell, P. S. (2014). Sensory Profile Caregiver Questionnaire: A measure for sensory impairment among children with developmental disabilities in India. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 81(2), S183–186. doi:10.1007/s12098-014-1603-4

- Ben-Sasson, A., Cermak, S. A., Orsmond, G. I., Carter, A. S., & Fogg, L. (2007). Can we differentiate sensory over-responsivity from anxiety symptoms in toddlers? perspectives of occupational therapists and psychologists. Infant Mental Health Journal, 28(5), 536–558. doi:10.1002/imhj.20152

- Berghmans, J. M., Poley, M. J., van der Ende, J., Rietman, A., Glazemakers, I., Himpe, D. … Utens, E. (2018). Changes in sensory processing after anesthesia in toddlers. Minerva anestesiologica, 84(8), 919–928. doi:10.23736/S0375-9393.18.12132-8

- Bevans, K. B., Piller, A., & Pfeiffer, B. (2020). Psychometric evaluation of the participation and sensory environment questionnaire-home scale (PSEQ-H). The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(3), p74032050501–74032050509. doi:10.5014/ajot.2020.036509

- Bharadwaj, S. V., Daniel, L. L., & Matzke, P. L. (2009). Sensory-processing disorder in children with cochlear implants. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(2), 208–213. doi:10.5014/ajot.63.2.208

- Blanche, E. I., Bodison, S., Chang, M. C., & Reinoso, G. (2012). Development of the comprehensive observations of proprioception (COP): Validity, reliability, and factor analysis. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(6), 691–698. doi:10.5014/ajot.2012.003608

- Bodison, S. C., & Parham, L. D. (2018). Specific sensory techniques and sensory environmental modifications for children and youth with sensory integration difficulties: A systematic review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(1). 7201190040p1–7201190040p11 doi:10.5014/ajot.2018.029413

- Bolaños, C., Gomez, M. M., Ramos, G., & Rios Del Rio, J. (2016). Developmental risk signals as a screening tool for early identification of sensory processing disorders. Occupational Therapy International, 23(2), 154–164. doi:10.1002/oti.1420

- Briet, G., Le Maner-Idrissi, G., Seveno, T., Lemarec, O., & Le Sourn-Bissaoui, S. (2021). Developmental follow-up of children with autism spectrum disorder enrolled in inclusive units in France: Outcomes and correlates of change. International Journal of Disability Development and Education, 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2021.1921123

- Brock, M. E., Freuler, A., Baranek, G. T., Watson, L. R., Poe, M. D., & Sabatino, A. (2012). Temperament and sensory features of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(11), 2271–2284. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1472-5

- Brown, T., Leo, M., & Austin, D. W. (2008). Discriminant validity of the Sensory Profile in Australian children with autism spectrum disorder. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 28(3), 253–266. doi:10.1080/01942630802224983

- Brown, G. T., Rodger, S., Brown, A., & Roever, C. (2007). A profile of Canadian pediatric occupational therapy practice. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 21(4), 39–69. doi:10.1080/J003v21n04_03

- Brown, G. T., & Subel, C. (2013). Known-group validity of the infant toddler sensory profile and the sensory processing measure-preschool. Journal of Occupational Therapy Schools & Early Intervention, 6(1), 54–72. doi:10.1080/19411243.2013.771101

- Bruder, M. B. (2000). Family-centered early intervention: Clarifying our values for the new millennium. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 20(2), 105–115. doi:10.1177/027112140002000206

- Bundy, A., & Lane, S. (2020). Sensory integration: Theory and practice (3ª ed.). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company.

- Carr, J. L., Agnihotri, S., & Keightley, M. (2010). Sensory processing and adaptive behavior deficits of children across the fetal alcohol spectrum disorder continuum. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(6), 1022–1032. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01177.x

- Castillejos-Zenteno, L., & Rivera-González, R. (2009). The relationship between sensory profile, the functioning of the child-parent relation and psychomotor development in three-year-olds. Salud Mental, 32(3), 231–239. Retrieved from www.scopus.com

- Chen, Y., Rodgers, J., & McConachie, H. (2009). Restricted and repetitive behaviours, sensory processing and cognitive style in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(4), 635–642. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0663-6

- Chen, Y. J., Sideris, J., Watson, L. R., Crais, E. R., & Baranek, G. T. (2023). Early developmental profiles of sensory features and links to school-age adaptive and maladaptive outcomes: A birth cohort investigation. Development and Psychopathology, 1–11. doi:10.1017/S0954579422001195

- Chen, Y. C., Tsai, W. H., Ho, C. H., Wang, H. W., Wang, L. W., Wang, L. Y. … Hwang, Y. S. (2021). Atypical sensory processing and its correlation with behavioral problems in late preterm children at age two. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6438. doi:10.3390/ijerph18126438

- Cheung, P. P., & Siu, A. M. (2009). A comparison of patterns of sensory processing in children with and without developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(6), 1468–1480. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2009.07.009

- Chien, C., Rodger, S., Copley, J., Branjerdporn, G., & Taggart, C. (2016). Sensory processing and its relationship with children’s daily life participation. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 36(1), 73–87. doi:10.3109/01942638.2015.1040573

- Cohn, E., May-Benson, T. A., & Teasdale, A. (2011). The relationship between behaviors associated with sensory processing and parental sense of competence. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 31(4), 172–181. doi:10.3928/15394492-20110304-01

- Colyvas, J. L., Sawyer, L. B., & Campbell, P. H. (2010). Identifying strategies early intervention occupational therapists use to teach caregivers. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(5), 776–785. doi:10.5014/ajot.2010.09044

- Crasta, J. E., Benjamin, T. E., Suresh, A. P., Alwinesh, M. T., Kanniappan, G., Padankatti, S. M. … Nair, M. K. (2014). Feeding problems among children with autism in a clinical population in India. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 81(2), S169–172. doi:10.1007/s12098-014-1630-1

- Critz, C., Blake, K., & Nogueira, E. (2015). Sensory processing challenges in children. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 11(7), 710–716. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.04.016

- Crozier, S. C., Goodson, J. Z., Mackay, M. L., Synnes, A. R., Grunau, R. E., Miller, S. P., & Zwicker, J. G. (2016). Sensory Processing Patterns in Children Born Very Preterm. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70(1), p70012200501–70012200507. doi:10.5014/ajot.2016.018747

- Dalmau, M., Balcells-Balcells, A., Giné, C., Cañadas, M., Casas, O., Salat, Y. … Calaf, N. (2017). Cómo implementar el modelo centrado en la familia en la intervención temprana. Anales de Psicologia, 33(3), 641–651. doi:10.6018/analesps.33.3.263611

- Davis, A. M., Bruce, A. S., Khasawneh, R., Schulz, T., Fox, C., & Dunn, W. (2013). Sensory processing issues in young children presenting to an outpatient feeding clinic. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 56(2), 156–160. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182736e19

- DeGangi, G. A., & Berk, R. A. (1983). The test of sensory integration. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

- DeGangi, G. A., & Greenspan, S. I. (1989). Test of sensory functions in infants. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

- DeSantis, A., Harkins, D., Tronick, E., Kaplan, E., & Beeghly, M. (2011). Exploring an integrative model of infant behavior: What is the relationship among temperament, sensory processing, and neurobehavioral measures? Infant Behavior & Development, 34(2), 280–292. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.01.003

- Di Renzo, M., Bianchi di Castelbianco, F., Vanadia, E., Petrillo, M., Racinaro, L., & Rea, M. (2020). Parental perception of stress and emotional-behavioural difficulties of children with autism spectrum disorder and specific language impairment. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 5, 2396941520971502. doi:10.1177/2396941520971502

- Division for Early Childhood (DEC). (2014). DEC recommended practices in early intervention/early childhood special education. Retrieved from https://www.dec-sped.org/dec-recommended-practices

- Dunn, W. (1999). The sensory profile manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation.

- Dunn, W. (2014). Sensory profile 2 user’s manual. Bloomington, MN: Pearson.

- Dunn, W., Cox, J., Foster, L., Mische-Lawson, L., & Tanquary, J. (2012). Impact of a contextual intervention on child participation and parent competence among children with autism spectrum disorders: A pretest-posttest repeated-measures design. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(5), 520–528. doi:10.5014/ajot.2012.004119

- Dunst, C. J., Bruder, M. B., & Espe-Shervindt, M. (2014). Family capacity building in early childhood intervention: Do context and setting matter?. School Community Journal, 24(1), 37–48.

- Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Hamby, D. W. (2007). Meta-analysis of family-centered help giving practices research. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13(4), 370–378. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20176

- Dwyer, P., Saron, C. D., & Rivera, S. M. (2020). Identification of longitudinal sensory subtypes in typical development and autism spectrum development using growth mixture modelling. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 78, 101645. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101645

- Dwyer, P., Wang, X., De Meo-Monteil, R., Hsieh, F., Saron, C. D., & Rivera, S. M. (2020). Defining clusters of young autistic and typically developing children based on loudness-dependent auditory electrophysiological responses. Molecular Autism, 11(1), 48. doi:10.1186/s13229-020-00352-3

- Eeles, A. L., Anderson, P. J., Brown, N. C., Lee, K. J., Boyd, R. N., Spittle, A. J., & Doyle, L. W. (2013). Sensory profiles obtained from parental reports correlate with independent assessments of development in very preterm children at 2 years of age. Early Human Development, 89(12), 1075–1080. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.07.027

- Eeles, A. L., Spittle, A. J., Anderson, P. J., Brown, N., Lee, K. J., Boyd, R. N., & Doyle, L. W. (2013). Assessments of sensory processing in infants: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 55(4), 314–326. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04434.x

- Ee, S. I., Loh, S. Y., Chinna, K., & Marret, M. J. (2016). Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Malay version of the short sensory profile. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 36(2), 117–130. doi:10.3109/01942638.2015.1040574

- Emond, A., Emmett, P., Steer, C., & Golding, J. (2010). Feeding symptoms, dietary patterns, and growth in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 126(2), e337–342. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2391

- Engel-Yeger, B., Hardal-Nasser, R., & Gal, E. (2011). Sensory processing dysfunctions as expressed among children with different severities of intellectual developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(5), 1770–1775. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.03.005

- Estaki, M., Dehghan, A., Mahmoudi-Kojidi, E., & Mirzakhany, N. (2021). Psychometric evaluation of the child sensory profile 2 (CSP2) among children with dyslexia. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), e112573. doi:10.5812/ijpbs.112573

- Faller, P., Hunt, J., Van Hooydonk, E., Mailloux, Z., & Schaaf, R. (2016). Application of data-driven decision making using Ayres sensory integration® with a child with autism. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70(1), p70012200201–70012200209. doi:https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2016.016881

- Fernández-Andrés, M. I., Pastor-Cerezuela, G., Sanz-Cervera, P., & Tárraga-Mínguez, R. (2015). A comparative study of sensory processing in children with and without autism spectrum disorder in the home and classroom environments. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 202–212. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.12.034

- Fernandez-Prieto, M., Moreira, C., Cruz, S., Campos, V., Martínez-Regueiro, R., Taboada, M. … Sampaio, A. (2021). Executive Functioning: A Mediator Between Sensory Processing and Behaviour in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(6), 2091–2103. doi:10.1007/s10803-020-04648-4

- Fetta, A., Carati, E., Moneti, L., Pignataro, V., Angotti, M., Bardasi, M. C. … Parmeggiani, A. (2021). Relationship between sensory alterations and repetitive behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders: A parents’ questionnaire based study. Brain Sciences, 11(4), 484. doi:10.3390/brainsci11040484

- Fjeldsted, B., & Xue, L. (2019). Sensory processing in young children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 39(5), 553–565. doi:10.1080/01942638.2019.1573775

- Flanagan, J. E., Schoen, S., & Miller, L. J. (2019). Early identification of sensory processing difficulties in high-risk infants. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(2), p73022051301–73022051309. doi:10.5014/ajot.2018.028449

- Fonseca-Angulo, R., Moreno-Zuleta, N., Crissien-Quiroz, E., & Blumtritt, C. (2020). Perfil sensorial en niños con trastorno del espectro autista. Archivos Venezolanos De Farmacologia y Terapeutica, 39(1), 105–111. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4068178

- Fox, C., Snow, P. C., & Holland, K. (2014). The relationship between sensory processing difficulties and behaviour in children aged 5–9 who are at risk of developing conduct disorder. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 19(1), 71–88. doi:10.1080/13632752.2013.854962

- Gal, E., Dyck, M. J., & Passmore, A. (2010). Relationships between stereotyped movements and sensory processing disorders in children with and without developmental or sensory disorders. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(3), 453–461. doi:10.5014/ajot.2010.09075

- Galiana, A., Flores-Ripoll, J. M., Benito-Castellanos, P. J., Villar-Rodriguez, C., & Vela-Romero, M. (2022). Prevalence and severity-based classification of sensory processing issues. An exploratory study with neuropsychological implications. Applied Neuropsychology Child, 11(4), 850–862. doi:10.1080/21622965.2021.1988602

- Galiana-Simal, A., Vela-Romero, M., Romero-Vela, V. M., Oliver-Tercero, N., García-Olmo, V., Benito-Castellanos, P. J. … Beato-Fernandez, L. (2020). Sensory processing disorder: Key points of a frequent alteration in neurodevelopmental disorders. Cogent Medicine, 7(1). doi:10.1080/2331205x.2020.1736829

- Galvin, J., Froude, E. H., & Imms, C. (2009). Sensory processing abilities of children who have sustained traumatic brain injuries. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(6), 701–709. doi:10.5014/ajot.63.6.701

- Ganapathy-Sankar, U., & Priyadarshini, S. (2014). Standardization of tamil version of short sensory profile. International Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences, 5(4), B260–266. Retrieved from www./scopus.com

- Germani, T., Zwaigenbaum, L., Bryson, S., Brian, J., Smith, I., Roberts, W. … Vaillancourt, T. (2014). Brief report: Assessment of early sensory processing in infants at high-risk of autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3264–3270. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2175-x

- Ghanavati, E., Zarbakhsh, M., & Haghgoo, H. A. (2013). Effects of vestibular and tactile stimulation on behavioral disorders due to sensory processing deficiency in 3-13 years old Iranian autistic children. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal, 11, 52–57. Retrieved from. www.scopus/.com

- Giudice, C., Rogers, E. E., Johnson, B. C., Glass, H. C., & Shapiro, K. A. (2019). Neuroanatomical correlates of sensory deficits in children with neonatal arterial ischemic stroke. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 61(6), 667–671. doi:10.1111/dmcn.14101

- Glennon, T. J., Kuhaneck, H. M., & Herzberg, D. (2011). The sensory processing measure-preschool (SPM-P)-part one: Description of the tool and its use in the preschool environment. Journal of Occupational Therapy Schools & Early Intervention, 4(1), 42–52. doi:10.1080/19411243.2011.573245

- Glod, M., Riby, D. M., & Rodgers, J. (2019). Short report: Relationships between sensory processing, repetitive behaviors, anxiety, and intolerance of uncertainty in autism spectrum disorder and Williams syndrome. Autism Research, 12(5), 759–765. doi:10.1002/aur.2096

- Glod, M., Riby, D. M., & Rodgers, J. (2020). Sensory processing profiles and autistic symptoms as predictive factors in autism spectrum disorder and Williams syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 64(8), 657–665. doi:10.1111/jir.12738

- Gourley, L., Wind, C., Henninger, E. M., & Chinitz, S. (2013). Sensory processing difficulties, behavioral problems, and parental stress in a clinical population of young children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(7), 912–921. doi:10.1007/s10826-012-9650-9

- Green, D., Lim, M., Lang, B., Pohl, K., & Turk, J. (2016). Sensory processing difficulties in opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. Journal of Child Neurology, 31(8), 965–970. doi:10.1177/0883073816634856

- Hall, L., & Case-Smith, J. (2007). The effect of sound-based intervention on children with sensory processing disorders and visual-motor delays. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(2), 209–215. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.209

- Halliday, J. L., Muggli, E., Lewis, S., Elliott, E. J., Amor, D. J., O’Leary, C. … Anderson, P. J. (2017). Alcohol consumption in a general antenatal population and child neurodevelopment at 2 years. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71(10), 990–998. doi:10.1136/jech-2017-209165

- Hen-Herbst, L., Jirikowic, T., Hsu, L. -Y., & McCoy, S. W. (2020). Motor performance and sensory processing behaviors among children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders compared to children with developmental coordination disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 103, 103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103680

- Holmlund, M., & Orban, K. (2021). Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the performance-based test – evaluation in Ayres sensory integration®. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 28(8), 609–620. doi:10.1080/11038128.2020.1831059

- Howard, A. R. H., Lynch, A. K., Call, C. D., & Cross, D. R. (2020). Sensory processing in children with a history of maltreatment: An occupational therapy perspective. Vulnerable Child and Youth Studies, 15(1), 60–67. doi:10.1080/17450128.2019.1687963

- Inada, N., Ito, H., Yasunaga, K., Kuroda, M., Iwanaga, R., Hagiwara, T. … Tsujii, M. (2015). Psychometric properties of the RBS-R for individuals with autism spectrum disorder in Japan. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 15–16, 60–68. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2015.01.002

- Ishien, L., Pao-Sheng, S., Mei-Liang, W., & Wenchun, W. (2022). The relationship between preschoolers’ sensory regulation and temperament: Implications for parents and early childhood caregivers. Early Child Development and Care, 192(8), 1190–1200. doi:10.1080/03004430.2020.1853116

- Iwanaga, R., Honda, S., Nakane, H., Tanaka, K., Toeda, H., & Tanaka, G. (2014). Pilot Study: Efficacy of sensory integration therapy for Japanese children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Occupational Therapy International, 21(1), 4–11. doi:10.1002/oti.1357

- Johnson-Ecker, C. L., & Parham, L. D. (2000). The evaluation of sensory processing: A validity study using contrasting groups. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54(5), 494–503. doi:10.5014/ajot.54.5.494

- Jorquera-Cabrera, S., Romero-Ayuso, D., Rodriguez-Gil, G., & Triviño-Juárez, J. M. (2017). Assessment of sensory processing characteristics in children between 3 and 11 years old: A systematic review. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 5, 57. doi:10.3389/fped.2017.00057

- Junqueira, P., Dos Santos, D. L. C., Lebl, M. C. G., de Cesar, M. F. C., Dos Santos Amaral, C. A., & Alves, T. C. (2021). Relationship between anthropometric parameters and sensory processing in typically developing Brazilian children with a pediatric feeding disorder. Nutrients, 13(7), 2253. doi:10.3390/nu13072253

- Jutley-Neilson, J., Greville-Harris, G., & Kirk, J. (2018). Pilot study: Sensory integration processing disorders in children with optic nerve hypoplasia spectrum. The British Journal of Visual Impairment, 36(1), 5–16. doi:10.1177/0264619617730859