ABSTRACT

Only one-third of U.S. fourth-grade public school students score at or above reading proficiency on national standardized tests. Current language-based reading instruction methods do not appear to meet many students’ needs. This study explores the role of visual perception in word recognition skills amongst typically developing first graders. It is hypothesized that visual perception is a crucial component of word recognition. This quantitative correlational study explored the relationship between visual perception and word recognition skills in first grade students participating in general education. The findings revealed that several statistically significant relationships exist between visual perceptual functions and skills recruited for word recognition. Phonological processing is strongly associated with spatial relations (r = .35) and sequential memory (r = .38). These correlations are significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Form constancy (r = .28) p < .05 is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). These relationships suggest that visual perceptual skills and phonological processing are concurrently developed in these participants and that these skills are likely recruited simultaneously when engaging in occupations, such as learning to read. This study highlights the role of visual perception in early reading development. Educators may consider consulting with school-based occupational therapists to explore the potential impact of visual perception when supporting students who struggle with reading.

Introduction

Reading is a fundamental skill that we use throughout our lifetimes; in fact, one’s academic, financial, and social success is closely linked with their ability to read (Ritchie & Bates, Citation2013). Unfortunately, only one-third of fourth-grade public school students score at or above reading proficiency on national standardized tests (National Assessment of Education Progress [NAEP], Citation2022) and students’ reading scores on these tests have remained stagnant for over a decade (National Assessment of Education Progress [NAEP], Citation2023). These results are perplexing given the extensive resources devoted to reading education in the U.S. Perhaps reading relies on areas of functioning that are currently overlooked in existing instructional methods. This study explores these potentially overlooked aspects of reading development and considers the role occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) may play to support students in meeting their reading outcomes.

Several evidence-based educational models have been implemented in schools to support struggling students in meeting grade level expectations in reading. The most common support is known as Response to Intervention (RtI) (Cortiella & Horowitz, Citation2014), which is comprised of up to four levels of instruction (known as tiers), in any core subject, that increase in frequency, duration, and intensity. The most common implementation of RtI is in reading instruction (Connor et al., Citation2014). In this domain, RtI is provided as an intervention for students reading below grade-level benchmarks, including decoding text, having difficulty comprehending passages, or experiencing both. In addition to being the most implemented model for reading, 66% of schools used RtI as a factor when considering a referral to Special Education (Cortiella & Horowitz, Citation2014). In practice, students who do not respond to RtI may be classified as having a disability and thus be eligible for educationally relevant support services through special education (Gersten & Dimino, Citation2006). Another support that has been implemented is Multi-Tiered Support Service (MTSS) (Stoiber & Gettinger, Citation2016, pp. 121–141). Students who struggle academically often display avoidant, and sometimes disruptive, behaviors. They benefit from MTSS, as this tiered model addresses students’ academic, behavioral, and social needs (Nitz et al., Citation2023).

RtI, MTSS, and other supplemental reading supports provided in schools have achieved some success; however, these models pose several challenges (Berkeley et al., Citation2020). RtI requires educators to increase levels of support if the student does not respond to typical classroom instruction, evidenced by the failure to meet grade-level expectations. The assumption is that more intense instruction will yield better outcomes; however, the preponderance of poor scores on standardized tests suggests that this model does not meet all students’ needs (Cassidy et al., Citation2016; Kena et. al., Citation2015; NAEP, Citation2023; NCES, 2019). Sanford and Horner (Citation2013) state that matching the reading instructional level to the student’s skill level is integral to increasing academic engagement and decreasing problem behaviors. However, increasing the level of frequency and intensity of instruction, as prescribed by the RtI model, may be ineffective if the deficits contributing to the reading difficulty are occluded. OTPs utilize holistic approaches by exploring contexts, performance patterns, performance skills, and client factors that influence participation in occupations (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2020). This extends to reading, as OTPs can support students who struggle with reading by considering the spectrum of factors involved in this occupation, thereby expanding the current conceptualization of reading as primarily a language and cognitive based skill.

Reading instruction and reading intervention techniques employed in RtI focus on the language and cognitive components of reading development. Although these evidence-based programs identify phonological processing, vocabulary, and comprehension, as core components of reading development, a body of research suggests that deficits in visual-perceptual processing may contribute also to reading difficulties (Gori & Facoetti, Citation2014; Zhou et al., Citation2014). In fact, The National Early Literacy Panel (Lonigan & Shanahan, Citation2009) states that the ability to match and discriminate between visual symbols is one of the key skills necessary to learn to decode text. Herein lies another issue with the RtI model. If many reading curricula focus on the language aspects of reading, and struggling students are provided with more frequent and intense instruction in these language and cognitive skill-based programs, then students who experience visual perceptual difficulties will not have the support they require to learn how to visually discriminate between symbols for decoding text. This cycle may continue until the student fails to make sufficient progress and is then referred for more specialized evaluation through Special Education. This too, is an example of a potentially missed opportunity to support students in the early stages of reading development, as language-based instructional methods would have little impact on the student who experiences undetected visual perceptual deficits. Moreover, this approach may inadvertently imperil the policy of educating students within least restrictive environments (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Citation2023).

Reading development relies on the progression of fundamental to more complex abilities, and any deficit along this continuum will impact subsequent stages of reading development. Therefore, most educators agree that early identification of reading difficulties greatly enhance outcomes (Connor et al., Citation2014), as immediately addressing the obstacle in learning to read is crucial to avoiding compounding delays. The RtI model promotes the assessment of reading progress at regular intervals throughout each school year, serving as consistent monitoring of student performance to avoid late identification of struggling students. Here too, occupational therapy can be provided as a complementary support to students along with RtI. OTPs may consult with educators to identify factors impeding reading success that are not measured by reading assessments. This practice may also help to avoid a missed opportunity in supporting students with their reading outcomes between reading assessments. Children identified as having a disability may also benefit from occupational therapy, as a direct service, if they display deficits which fall within our domain of practice and impact reading progress. Arguably the conceptualization of reading assessment and reading intervention should be broadened, by considering additional component skills that may impede one’s achievement of their reading outcomes. The inclusion of occupational therapy in RtI may facilitate early identification of additional factors that contribute to reading difficulty. As a result, more effective interventions may be provided to support struggling students.

Uncovering underlying factors that contribute to reading difficulty is compelling. To that end, this study aims to discover overlooked components of reading development, as an initial step in understanding how to support students who struggle with reading and do not respond to existing instructional methods. In this study, the role of visual perception is presented as a potential factor in reading development. To examine this possibility more closely, this study explores the role of visual perception in word recognition skills amongst typically developing first graders. It is hypothesized that visual perception is a crucial component of word recognition, which is currently overlooked in the reading research that informs instruction and curricula.

Much of the literature related to reading difficulty references the Phonological Deficit Theory (Snowling, Citation1995). The Phonological Deficit Theory hypothesizes that deficits in the ability to process and associate the meaning of sounds are the obstacle that impedes reading acquisition. This deficit focused theory lacks the holistic conceptualization of the complex interplay of skills needed for reading. In contrast, OTPs analyze occupational performance by considering the interactions between the demands of the occupation and of the person’s contexts, performance patterns, performance skills, and factors (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2020); therefore, the theoretical perspectives we employ focus on these elements instead of deficits. For example, the Frame of Reference for Visual Perception (Schneck, Citation2018) explains the hierarchy of visual perceptual skills and its impact on function. Complementing the theoretical bases that guide this frame of reference, is a dynamic theory that explains the components of achieving reading competence. This theory addresses the skills necessary to achieve reading success and is more consistent with the occupational therapy approach to practice. This theory, known as The Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, Citation1986), identifies the integration of both word recognition and language comprehension as the key to learning to read, and it explains the relationship between skills that impact the rate and quality of reading development. This theory is most appropriate for this study, despite its apparent age, because this study aims to explore the role of visual perception on the development of word recognition, and not the impact of deficits on the acquisition of grade-level reading skills.

Gough and Tunmer (Citation1986) stated that mature reading may only emerge when word recognition and language comprehension are both strongly developed. In other words, decoding and recognizing words along with an understanding of their meanings, functions, and discourse are the core components of reading. Most importantly, both are necessary for developing reading competence. The Simple View also asserts that strength in one area will not compensate for a weakness in the other. Instead, Gough and Tumner argue that one’s reading ability will only be as strong as the weaker skill (word recognition, language comprehension, or both). Therefore, each component skill is equally important to reading development.

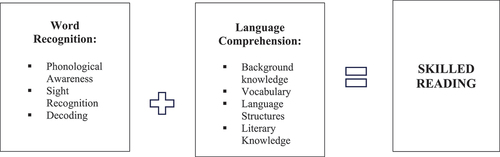

Scarborough et al. (Citation2009) expounds on Gough and Tumner’s theory by explaining that skilled reading also relies on fluency, which is the ability to read with appropriate phrasing and expression. Additionally, word recognition strengthens fluency and further supports reading mastery. Most importantly, the contribution of word recognition to fluency is essential to reading comprehension as it allows the reader to devote full attention to the meaning of text. According to this view, word recognition relies on phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition. Comprehension relies on background knowledge, vocabulary, understanding language structures, verbal reasoning, and knowledge of literacy concepts (Scarborough et al., Citation2009). Despite its development as far back as 1986, The Simple View of Reading continues to be validated by research (Catts, Citation2018; Hoover & Tunmer, Citation2018; Snow, Citation2018). The elements of skilled reading is illustrated in .

Word recognition is the focus of this study. Thus far, the language and cognitive components of word recognition have been thoroughly examined (Scarborough et al., Citation2009). This study hypothesizes that visual perception is an integral component of word recognition but is overlooked in existing reading research. More specifically, this study aims to explore the relationship of visual perceptual skills on elements of word recognition, including letter and word recognition, nonsense word decoding, and phonological processing. Although researchers in the field of reading occasionally reference the possibility of visual influences on the ability to recognize and name letters, known as the alphabetic principle, they do not attribute the role of visual perception as a significant contributor to reading development (Melby-Lervåg et al., Citation2012). This study thoroughly examines the alphabetic principle, and its relationship with visual perception, by utilizing an instrument that measures letter/word recognition skills.

Decoding is another essential component of word recognition, which requires visual and phonetic identification and discrimination skills to master the alphabetic principle (Byrne, Citation2014, p. 1). With this knowledge, students learn to sound out visually presented text and begin to learn and recognize words (Kahmi & Catts, Citation2012, p. 6). Furthermore, the automatic recognition of words, without conscious decoding, is the most efficient and effective form of word recognition and stems from the reader’s establishment of phonological and orthographic representations in the mental lexicon.

Some words cannot be decoded. They are known as sight words (the, light, knee). Recognizing these words relies on the integration of visual and phonological processing, as they defy conventional orthography. Given that a reader must visually recognize letters to then associate them with their sounds, it is plausible that letter and word recognition, as well as decoding, may be impacted by the reader’s visual perceptual skills. This hypothesis is supported in research that asserts the impact of visual processing in recognizing, discriminating between, and forming visual representations of the letters (Apfelbaum & McMurray, Citation2017) along with phonological processing to remember the sounds of the letters (Pattamadilok et al., Citation2017). However, none of these studies thoroughly explored the relationships between specific visual perceptual processes and letter/word recognition, nonsense word decoding, and phonological processing in early reading development. Understanding the dynamic relationships between these skills may be the key to best help struggling students to achieve their reading outcomes. In this study, word recognition is conceptualized as a skill that relies on both visual perceptual and phonological processing.

This study explores the relationship between visual perception and word recognition by measuring and correlating visual perceptual processes with components of word recognition, which include sight recognition of letters and words, decoding, and phonological processing. The rationale is that visual perception is hypothesized to impact word recognition. Comprehension is not the focus of this study, as it is a language-based skill, which does not fall within the occupational therapy domain.

The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (Citation2020, p. 33) cites formal education participation as a domain of practice. This includes academic activities such as reading, which is identified as an occupation that is integral to successful participation in an essential life activity. By extending this conceptualization to the school environment, school-based occupational therapists should address the essential skill of reading as an occupation of students. Therefore, it is appropriate for school-based occupational therapists to provide relevant interventions to support students in achieving their reading outcomes for academic success. Although limited research explores school-based occupational therapists’ involvement in supporting students in reading, OTPs’ unique perspective on occupation, along with our understanding of biological, environmental, and contextual influences on activity performance, may equip us to support students in achieving their reading outcomes. Furthermore, OTPs have specialized training in visual perception and its impact on function. Thus, it is assertable that students who experience reading difficulties stemming from visual perceptual deficits may benefit from occupational therapy as a support in helping them achieve their reading outcomes. It is in this vein that this study was conceived.

Recently, several occupational therapy researchers have shared strategies and potential benefits of occupational therapy on functional literacy. The research is based on theories and frames of references that highlight OTPs role in supporting students by considering contexts, such as behavioral patterns and socio-economic status, as well as performance patterns, such as habits and routines of reading (Arnaud & Gutman, Citation2022). Supporting those aims, this study explores the complex performance skills involved in reading development. The purpose is to expand the conceptualization of reading and include OTPs as members of the interdisciplinary team, by utilizing our expertise, in collaboration with the expertise of other professionals in supporting students who struggle with reading and do not respond to traditional remediation techniques. Therefore, the Simple View of Reading is the most relevant theoretical base for this study and complements theories often included in occupational therapy research.

Following the elements of The Simple View of Reading as theoretical basis this study, the relationship between visual perception and word recognition in early readers is explored by using normed instruments that measure these skills. The hope is to identify overlooked skills necessary for reading success and shed light on why some students do not respond to the traditional, language-based, reading interventions that are commonly implemented in RtI.

Materials and Methods

This quantitative, correlational study explores the relationships between visual perception and word recognition in first grade students within the general education environment. First grade students are most appropriate for this study, as they have already been taught letter identification, letter to sound correspondence, and phonemic awareness, and are now beginning to learn to use these skills for word recognition. Later grades focus on comprehension of text, which is not the focus of this study. This study’s purpose is to explore the potential contributions of OTPs toward supporting students who struggle with reading. By identifying factors that facilitate or inhibit word recognition development in young children, OTPs can participate in the development and implementation of supports to help young children achieve their reading goals. This study was approved by the New York University Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Eighty general education first graders participated in this study. Participants were recruited utilizing a nonrandom convenience sampling plan from a private school in Nassau County, NY. These students were beginning to learn the fundamentals of reading, which corresponded with the optimal time to explore the performance skills in the occupation of learning to read. Prior to the initiation of the study, a letter explaining the details of the study was shared with the parents of the prospective participants in this class. The letter also included a request for parental consent. Parental consent and child assent were obtained prior to participating in the study.

Although sampling a homogenous group might restrict the detection of variability in the data, sampling a more heterogeneous group might introduce factors that could influence the relationship between visual perception and reading. While this sampling design offers advantages, it is possible that the findings may not generalize to the population. Inclusion criteria encompassed general education first graders, as it was assumed these students can learn the grade level curriculum. This limits the variability of cognitive and learning abilities of the students within the sample, thereby limiting the influence of these factors on their performance throughout this study. Additionally, students were required to have current vision and hearing screenings on file in the nurse’s office, indicating that their sensory functions fell within normal ranges. This also substantiates the accuracy of the test scores derived from this study. All students who met functioning criteria were included in this study.

It should be noted that the students in this sample met inclusion criteria at the time of this study; however, it is possible that learning needs in some of these students may be detected later. Despite this, the findings from this study would remain valid as the students’ skills were tested during their participation in general education while keeping up with the grade-level curriculum.

Instruments

Two instruments were utilized for this study. The first instrument utilized was the Test of Visual Perception-4th Ed (Martin, Citation2017). The entire Test of Visual Perceptual Skills-4 (TVPS-4) was administered, which included the subtests of Visual Discrimination, Visual Memory, Visual Spatial Relationships, Visual Form Constancy, Visual Sequential Memory, Visual Figure-Ground, and Visual Closure. The second instrument utilized was the Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement 3rd ED (Kaufman & Kaufman, Citation2017). Only portions relevant to reading were selected from the Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement-3 (KTEA-3). The KTEA-3 subtests relevant to reading include Letter/Word Recognition to measure the ability to decode English language words, and to recognize letters and sight words; Nonsense Word Decoding to measure the ability to decode words that have no English language meaning; and Phonological Processing to measure the ability to recognize and process phonological (sound) representations.

The Test of Visual Perceptual Skills-4th ED

The TVPS-4 was originally developed by Morris Gardener in 1982 and has been revised by its publisher Academic Therapy Publications. The most recent version, which was used in this study, was published in 2017. The TVPS-4 was selected because it examines more areas of visual perception than other tests of visual perception. For example, the Developmental Test of Visual Perception-3rd Ed (Hammill et al., Citation2014) tests eye-hand coordination, copying, figure ground, visual closure, and form constancy. Unlike the TVPS-4, the Developmental Test of Visual Perception consists of only 5 subtests and two of those subtests incorporate motor skills, which is irrelevant to this study. The Motor Free Test of Visual Perception (Coloruso & Hammill, Citation2015) tests visual discrimination, spatial relationships, visual memory, figure ground, and visual closure. This instrument provides one composite score, which does not fit the detailed correlation model in this study design. In contrast, the TVPS-4 provides normed scores for each of the subtests, which allows correlations with normed scores derived from the KTEA.

Reliability and Validity

The average Cronbach’s alpha for the overall score on the TVPS-4 is 0.94, with values raging between 0.68–0.81 across the individual subtests. Corrected test-retest correlations based on an average of 17 days yields an overall score of 0.97. Validity evidence based on comparison to the MVPT-4 reveal no significant differences between the mean scores [t(62) = 1.16, p = 0.25].

Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement 3rd ED

The KTEA-3 was developed by Kaufman and Kaufman and most recently revised in 2017. This instrument assesses a wide range of educational skills. The KTEA-3 was selected for this study, as it is a widely accepted instrument used in many schools to measure various aspects of learning. It thoroughly examines the variables of interest in this study (letter/word recognition, decoding, and phonological processing) and is easy to administer. In addition, the subtests are also normed, making it fit the correlational model for analysis. Although the Woodcock Johnson 4th Edition (Schrank et al., Citation2014) is an instrument that is also widely used in schools, it lacks the detailed examination of phonological processing (Villarreal, Citation2015). Therefore, it was not considered for this study, as according to the Simple View of Reading, phonological processing is an essential component of word recognition.

Reliability and Validity

The overall reliability coefficient for the KTEA-3 ranges from 0.87–0.95 (Kaufman & Kaufman, Citation2017). The internal reliability coefficient ranges from 0.77–0.85. The test-retest coefficient based on 1–35 days is 0.90. When compared to the Wide Range Achievement, Peabody Individual Achievement Test, Metropolitan Achievement Test, Stanford Achievement Test, and the ABC, the KTEA achieves correlates ranging from 0.75–0.86 (Breaux & Lichtenberger, Citation2016).

Power Analysis

A power analysis was conducted to determine how many participants would be needed to demonstrate statistically significant relationships, if the data supported such findings. To conduct the power analysis, the researcher collected standardized test scores, through a chart review of 13 students who were not considered for participation in this study. Letter/Word Recognition subtest scores were derived from the KTEA-3 and visual perception scores were derived from the Beery Test of Visual Motor Integration-6th Ed (VMI). The VMI was the only visual perceptual test available in these students’ charts. This standardized test has been found to measure the construct of visual discrimination as effectively the TVPS-4 and the subtests are considered interchangeable (Brown & Rodger, Citation2009). The mean score for visual perception was 97.33 with a standard deviation of 9.91. The mean score for Letter/Word recognition was 94.80 with a standard deviation of 10.71. The correlational analysis between VMI and KTEA scores revealed a sample correlation of r = 0.422.

To conduct power analyses, a minimum detectable effect size must be determined. In the context of a simple test for statistically significant correlation, the effect size d is simply the expected bivariate correlation. That is, d = p1 - p0 = p1 – 0 = p1; where p1 is the correlation in the population of students from which the pilot data was drawn (Howell, Citation2013). For this study, the correlation between visual perception and letter/word identification of r = 0.422 was used in the power analysis. Based on this MDES as well as (alpha = 0.05) and a power of 0.80, 36 participants were determined necessary to detect a statistically significant relationship between visual perception and word recognition skills of this magnitude; however, in this study, the researcher examined multiple measures from the same assessments. Multiple hypothesis tests increase the probability of detecting a significant effect by chance where none exists in the population. As a result, a Bonferroni adjustment was used to increase the threshold for rejection of the null hypothesis. This adjustment in the power analysis reveals that a minimum of 61 participants are needed to demonstrate a statistically significant relationship visual perceptual skills scores achieved on the TVPS-4 and the word recognition skills scores achieved on the KTEA-3.

Testing Administration

The school set aside a quiet area with a table and chairs for the researcher to conduct the testing using the TVPS-4 and the KTEA-3. The researcher had worked in school-based practice for 26 years, with extensive experience in administering and interpreting standardized tests. Following receipt of student assent to participate in the testing session, students followed the researcher to the testing area. The three subtests of letter/word recognition, nonsense word decoding, and phonological processing were administered first. Testing using all parts of the KTEA-4 followed. Score sheets were numbered to ensure anonymity of data. Additionally, all anonymized forms were scored after testing administration of all students. This further ensured that no test scores could be traced to any particular student.

Data Analysis

A correlational analysis was conducted between the scores of all seven subtests in the TVPS-4 and the scores of the three KTEA-3 subtests that relate to word recognition skills. Therefore, a Bonferroni adjustment was used for this analysis to increase the threshold for rejection of the null by lowering the p value needed to find a significant result.

Results

This study explored the relationship between visual perception and word recognition skills in 80 general education first graders. The sample consisted of 37 females and 43 males. The students’ visual perceptual skills were tested with the TVPS-4. Scales from the TVPS-4 included visual discrimination, visual memory, spatial relations, form constancy, sequential memory, figure ground, and visual closure. The students’ word recognition skills tested using three scales from the KTEA-3, which included Letter/Word Recognition, nonsense word decoding, and phonological processing. Descriptive statistics of these variables may be found in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

A correlational analysis reveals interesting relationships between variables. Phonological Processing, expectedly, has a strong association with Letter/Word Recognition (r = .44) p < .01 and with Nonsense Word Decoding (r = .24) p < .05. An exciting observation includes a moderate strength relationship between visual memory and Letter/Word identification (r = .387) p < .01. This finding highlights the involvement of visual perception in early reading skills and reinforces the notion that OTPs should participate in the interdisciplinary team, by using our expertise in understanding visual perception, to support students who struggle with reading. Interestingly, several other statistically significant observations exist between variables. Phonological processing is strongly associated with spatial relations (r = .35) and sequential memory (r = .38). These correlations are significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Form constancy (r = .28) p < .05 is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). These relationships suggest that visual perceptual skills and phonological processing are concurrently developed in these participants and that these skills are likely recruited simultaneously when engaging in occupations, such as learning to read ().

Table 2. Pearson correlations of variables.

Discussion

This study examined the correlational relationship between visual perception and word recognition skills in general education first graders. The TVPS-4 and the KTEA-3 were used as standardized instruments to measure how closely related visual perception is to letter/word recognition, nonsense word decoding, and phonological processing, as components of word recognition. This study also compared the strength of these relationships the widely accepted component skill of phonological processing. This approach adds to much of the existing literature, which currently suggests that language skills are the key components necessary to learn to read. The current study reveals that visual memory is a contributor to letter/word recognition. Additionally, aspects of visual perception are strongly correlated with phonological processing, suggesting that these skills are simultaneously recruited in these participants when engaged in testing. One may then suspect that these strongly correlated skills are also recruited when learning to read. Although visual perception was not found to be strongly correlated with nonsense word decoding, the descriptive statistics demonstrate a high negative skew for nonsense word decoding scores attained by this sample. Replication of this study with a different sample might reveal a stronger relationship.

The Pearson correlation analysis of visual perceptual variables with letter/word recognition and nonsense word decoding reveals a positive relationship on all levels and rejects the null hypothesis. This finding supports the smaller body of research that asserts visual perception is a necessary component for learning to read (Perea, et. al., Citation2012; Schneps et al., Citation2013). Often, children with poor reading skills are found to struggle with visual attention. One could argue that weak visual perceptual skills might increase the cognitive load when attempting to recognize words. Subsequently, this added cognitive load could potentially diminish visual attention during reading activities. Perea, et. al. (Citation2012) found an unexpected relationship between visually presented materials and reading performance, as the speed and accuracy of skilled readers were hindered when they were supplied with modified reading materials designed to enhance poor readers’ performance. They concluded that skilled readers recognize whole words, rather than decode individual letters. This conclusion is consistent with the current study’s findings, as first grade students are acquiring automaticity in reading but are not fully proficient at this stage of their academic careers. It is arguable that automaticity may be facilitated by visual perceptual skills, such as visual memory, visual discrimination, and visual closure, as these skills are necessary for recognizing whole words to achieve reading proficiency.

This current study also found statistically significant relationships between three visual perceptual subtests: spatial relations; form constancy; and sequential memory; and phonological processing. This observation may reflect the concurrent emergence of these skills in typically developing children. However, it is also plausible that these skills are recruited simultaneously when engaged in academic tasks, supporting the assertion that visual perception is necessary for learning to read.

The findings in this current study fills a gap in understanding reading development, as it identifies visual perception to be positively correlated with word recognition skills. The National Reading Panel (U.S.), and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U.S.) (Citation2000) identifies five key components necessary for reading development. They include phonics, phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Much of the reading curricula in the United States are based on these findings. According to this research, readers with poor word recognition skills lack adequate phonological skills (Melby-Lervåg et al., Citation2012). However, this current study demonstrates that visual memory is a skill involved in recognizing letters and words. Perhaps the omission of visual memory in reading instruction contributes to the poor reading achievements in American students (NCES, 2019). Given the findings of the current study, educators might consider early screening of visual memory skills when students are first identified as struggling readers. In practice, OTPs may be approached by the interdisciplinary team to assist with screening for visual perceptual skills, including visual memory, might uncover underlying challenges students experience when learning to read. Therapeutic activities that aim to strengthen visual perceptual skills might also augment reading remediation approaches.

Moreover, elementary schools’ reading curricula begins with instruction in the simplest skill of letter-to-sound correspondence and builds with word recognition and comprehension until the complex skill of deriving meaning from text and drawing inferences is mastered (Foorman et al., Citation2003). Although letter-to-sound correspondence is highly dependent on the interplay of language and visual processing skills during reading (Brem et al., Citation2010), visual perception is not highlighted as an essential skill despite the fundamental need to visually recognize letters in order to match them with their sounds. Ehri (Citation2017) proposes a view of sight word reading in which words are recognized by retrieving the associations between the visual form of the word and its meaning; however, there is little mention of the visual perceptual skills involved in this process. Additionally, rapid automatic naming (RAN) has been identified as a predictor of reading success regardless of varying orthographies detected amongst different languages (Landerl et al., Citation2019). It is conceivable that visual memory skills may be recruited when attempting to recall letters quickly and accurately with their associated names.

In practice, overlooking visual memory as a component skill to reading may negatively impact the effectiveness of RtI and other forms of early identification, prevention, and intervention. More specifically, RtI is designed to serve as both an early detection tool and a remediation model for students who struggle to read. However, students who display reading difficulty are screened for their decoding, word recognition and language skills, but not for visual memory skills (Compton et al., Citation2006). As a result, students who experience weakness in visual memory skills may continue to struggle with reading, despite their participation in RtI, if this performance skill is not addressed as part of a comprehensive approach to reading instruction and remediation.

Limitations

This study aimed to explore the relationship between visual perceptual and word recognition skills in first graders, as formal reading instruction is an integral part of this curriculum. To limit the variability of factors that might influence the results, a sample of private school students were selected. This private school is accredited by New York State Board of Regents, and the curriculum meets New York State educational expectations; therefore, the students receive access to the same education as students who attend public school. However, the admissions process considers many student factors which are not employed in public school enrollment. This may have introduced unintended bias in the study. It is possible that this group was too homogenous to detect variability during the analysis. Future studies might sample first grade students, with similar learning profiles, from various schools to introduce some more heterogeneity. Additionally, a somewhat larger sample may have uncovered more significant relationships between the variables. Unfortunately, these options were unavailable during the time this study was conducted.

The academic demands of elementary school curricula increase with each grade. Therefore, students’ learning difficulties are often uncovered as these demands unfold. There is the possibility that students included in this study may experience learning difficulties that have yet to be revealed. If this is the case, some test scores may have been influenced by these students’ undetected learning difficulties and impacted the study’s findings.

Conclusion and Recommendations for Future Research

The role of visual perception as a factor in word recognition has been overlooked in most reading research. This quantitative study found a positive relationship between visual perception and word recognition skills, with a statistically significant relationship between visual memory and letter/word recognition. As a result, these findings suggest that visual perception, and visual memory in particular, should be considered as a performance skill in the occupation of learning to read. In practice, aspects of visual perception may be considered during reading instruction. Visual perceptual skills may be assessed along with reading screenings to identify weaknesses that may be contributing to the student’s struggle with learning to read. Strategies that integrate visual perceptual processes into reading remediation, such as RtI and other supplemental reading supports in schools, may enhance the effectiveness of those techniques. Most importantly, the role of OTPs on the school-based team should be considered as a valuable resource for supporting students in achieving their reading outcomes. OTPs’ knowledge of visual perception and its impact on function can further enhance an educator’s mission to help students successfully learn to read.

Future research may build upon this current study by exploring the relationship between visual perception and word recognition utilizing various instruments that assess these skills more comprehensively. The inclusion of cognitive functions in the analyses may further explain the complex interplay of many performance skills implicated in reading development. Longitudinal studies may be conducted to determine the impact of visual perceptual development on automaticity of word recognition as the reader matures. Studies that explore variations in visual perceptual skills between two groups of readers, skilled and struggling, may further enlighten the impact of visual perception on reading proficiency. Finally, studies exploring the impact on visual perceptual interventions on reading proficiency in struggling readers may highlight the role of visual perception in the occupation of learning to read.

Acknowledgements

Portions of this paper are derived from research conducted during my doctoral studies. I am grateful to my dissertation committee, Dr. Kristie Koenig, Chair (New York University); Dr. Sean Corcoran, Statistician, (New York University); and Dr. Susan Masullo, Content Expert, (Columbia University) for guiding and encouraging me through this study.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2), Article 7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

- Apfelbaum, K. S., & McMurray, B. (2017). Learning during processing: Word learning doesn’t wait for word recognition to finish. Cognitive Science, 41, 706–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12401

- Arnaud, L. M., & Gutman, S. A. (2022). Supporting literacy participation for underserved children: A set of guidelines for occupational therapy practice. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 15(2), 111–130.

- Berkeley, S., Scanlon, D., Bailey, T. R., Sutton, J. C., & Sacco, D. M. (2020). A snapshot of RTI implementation a decade later: New picture, same story. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 53(5), 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219420915867

- Breaux, K. C., & Lichtenberger, E. O. (2016). Essentials of KTEA-3 and WIAT-III assessment. John Wiley & Sons.

- Brem, S., Bach, S., Kucian, K., Guttorm, T. K., Brandeis, H., Martin, E., Lyytinen, D., & Richardson, U. (2010). Brain sensitivity to print emerges when children learn letter–speech sound correspondences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(17), 7939–7944. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0904402107

- Brown, T., & Rodger, S. (2009). An evaluation of the validity of the test of visual perceptual skills - revised (TVPS-R) using the rasch measurement model. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(2), 65–78. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.858.7496&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Byrne, B. (2014). The foundation of literacy: The child’s acquisition of the alphabetic principle. Psychology Press.

- Cassidy, J., Ortlieb, E., & Grote-Garcia, S. (2016). Beyond the common core: Examining 20 years of literacy priorities and their impact on struggling readers. Literacy Research and Instruction, 55(2), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2015.1136011

- Catts, H. W. (2018). The simple view of reading: Advancements and false impressions. Remedial and Special Education, 39(5), 317–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932518767563

- Colarusso, R. P., & Hammill, D. D. (2015). Motor-Free Visual Perception Test-4 (MVPT-4). Academic Therapy Publications.

- Compton, D. L., Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Bryant, J. D. (2006). Selecting at-risk readers in first grade for early intervention: A two-year longitudinal study of decision rules and procedures. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(2), 394. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.2.394

- Connor, C. M., Alberto, P. A., Compton, D. L., & O’Connor, R. E. (2014). Improving reading outcomes for students with or at risk for reading disabilities: A synthesis of the contributions from the institute of education sciences research centers. NCSER 2014-3000. National Center for Special Education Research. https://doi.org/10.1037/e606972011-004

- Cortiella, C., & Horowitz, S. H. (2014). The state of learning disabilities: Facts, trends, and emerging issues. National Center for Learning Disabilities, 25. https://www.ncld.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/2014-State-of-LD.pdf

- Ehri, L. C. (2017). Reconceptualizing the development of sight word reading and its relationship to recoding. In Reading acquisition. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351236904-5

- Foorman, B., Breier, J., & Fletcher, J. (2003). Interventions aimed at improving reading success: An evidence-based approach. Developmental neuropsychology, 24, 613–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2003.9651913

- Gersten, R., & Dimino, J. A. (2006). RTI (response to intervention): Rethinking special education for students with reading difficulties (yet again). Reading Research Quarterly, 41(1), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.41.1.5

- Gori, S., & Facoetti, A. (2014). Perceptual learning as a possible new approach for remediation and prevention of developmental dyslexia. Vision Research, 99, 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2013.11.011

- Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258600700104

- Hammill, D. D., Pearson, N. A., & Voress, J. K. (2014). Developmental test of visual perception (3rd ed.). Pro-Ed.

- Hoover, W. A., & Tunmer, W. E. (2018). The simple view of reading: Three assessments of its adequacy. Remedial and Special Education, 39(5), 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932518773154

- Howell, H. C. (2013). Statistical methods for psychology (8th ed.). Wadsworth.

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (2023). A history of the individuals with disabilities education act. https://sites.ed.gov/idea/IDEA-History#2000s-10s

- Kamhi, A. G., & Catts, H. W. (2012). Language and Reading Disabilities (3rd ed.). Pearson Education, Inc.

- Kaufman, A. S., & Kaufman, N. L. (2017). Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement-3 (KTEA-3). NCS Pearson.

- Kena, G., Musu-Gillette, L., Robinson, J., Wang, X., Rathbun, A., Zhang, J., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Barmer, A., & Velez, E. D. V. (2015). The condition of education 2015. NCES 2015- 144. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2015/2015144.pdf

- Landerl, K., Freudenthaler, H. H., Heene, M., De Jong, P. F., Desrochers, A., Manolitsis, G., Parrila, R., & Georgiou, G. K. (2019). Phonological awareness and rapid automatized naming as longitudinal predictors of reading in five alphabetic orthographies with varying degrees of consistency. Scientific Studies of Reading, 23(3), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2018.1510936

- Lonigan, C. J., & Shanahan, T. (2009). Developing early literacy: Report of the national early literacy panel. Executive summary. A scientific synthesis of early literacy development and implications for intervention. National Institute for Literacy. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED508381.pdf

- Martin, N. A. (2017). Test of Visual Perceptual Skills-4 (TVPS-4). Academic Therapy Publications.

- Melby-Lervåg, M., Lyster, S. H., & Hulme, C. (2012). Phonological skills and their role in learning to read: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 322. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026744

- National Assessment of Educaation Progress. (2023). https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/highlights/ltt/2023/

- National Assessment of Education Progress. (2022). https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/reading/#

- National Reading Panel (U.S.), & National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U.S.). (2000). Report of the national reading panel: Teaching children to read: And evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the sub-groups. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf

- Nitz, J., Brack, F., Hertel, S., Krull, J., Stephan, H., Hennemann, T., & Hanisch, C. (2023). Multi-tiered systems of support with focus on nitzbehavioral modification in elementary schools: A systematic review. Heliyon, 9(6), e17506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17506

- Pattamadilok, C., Chanoine, V., Pallier, C., Anton, J., Nazarian, B., Belin, P., & Ziegler, J. C. (2017). Automaticity of phonological and semantic processing during visual word recognition. Neuroimage: Reports, 149, 244–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.02.003

- Perea, M., Panadero, V., Moret-Tatay, C., & Gómez, P. (2012). The effects of inter-letter spacing in visual-word recognition: Evidence with young normal readers and developmental dyslexics. Learning & Instruction, 22(6), 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.04.001

- Ritchie, S. J., & Bates, T. C. (2013). Enduring links from childhood mathematics and reading achievement to adult socioeconomic status. Psychological Science, 24(7), 1301–1308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612466268

- Sanford, A. K., & Horner, R. H. (2013). Effects of matching instruction difficulty to reading level for students with escape-maintained problem behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 15(2), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300712449868

- Scarborough, H. S., Neuman, S., & Dickinson, D. (2009). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis) abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. Approaching Difficulties in Literacy Development: Assessment, Pedagogy, and Programmes, 23, 39. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118092668.ch2

- Schneck, M. (2018). A frame of reference for visual perception. In P. Kramer (Ed.), Frames of reference for pediatric occupational therapy (3rd ed. pp. 348–389). Lippincott Williams & Wlikins.

- Schneps, M. H., Thomson, J. M., Sonnert, G., Pomplun, M., Chen, C., & Heffner-Wong, A. (2013). Shorter lines facilitate reading in those who struggle. PLOS ONE, 8(8), e71161. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071161

- Schrank, F. A., Mather, N., & McGrew, K. S. (2014). Woodcock-Johnson IV tests of achievement. Riverside.

- Snow, C. E. (2018). Simple and not-so-simple views of reading. Remedial and Special Education, 39(5), 313–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932518770288

- Snowling, M. J. (1995). Phonological processing and developmental dyslexia. Journal of Research in Reading, 18(2), 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.1995.tb00079.x

- Stoiber, K. C., & Gettinger, M. (2016). Multi-tiered systems of support and evidence-based practices. In S. R. Jimerson (Ed.), Handbook of response to intervention (pp. 121–141). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7568-3

- U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National center for education statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), 2022 reading Assessment. https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/reading/#

- Villarreal, V. (2015). Review of the woodcock-Johnson IV tests of achievement. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 33(4), 391–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282915569447

- Zhou, Y., McBride Chang, C., & Wong, N. (2014). What is the role of visual skills in learning to read? Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 776–777. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00776