ABSTRACT

A prominent phenomenon in education in Europe and internationally is the demand for research-based education, which is also the case in Sweden, the context of this study. Therefore, greater academic demands have been placed on teachers, which can present a distinctive challenge for teachers who were educated when teacher education prioritised practical teacher training rather than academic training. Therefore, it is especially important to explore what and how experienced teachers learn and develop when moving towards a research-based education. The theoretical framework builds on communities of practice and social learning. The empirical data consists of written reflections from 50 teachers in preschool, compulsory and upper secondary school, who participated in action research projects that aimed to help build research-based education. The findings show that the teachers’ professional learning entailed changes in the ways they think, act and relate to others in three areas: teaching, research and collaboration. The study offers insights into the importance of a professional development process being based on a bottom-up perspective, collaborative, context-specific and integrated in teachers’ work. Lastly, the study points to the benefit of engagement on multiple levels – principals, lead teachers, teachers and researchers – to achieve lasting success in building research-based education.

Introduction

A prominent phenomenon in education in Europe and internationally is the demand for research-based education, which has spread from the US and UK to the Scandinavian countries and the rest of Europe (Cain Citation2015, Lambirth et al. Citation2019). Research-based education is designed to increase the quality of the education system in each country, raising teacher professionalism and producing better student results (OECD Citation2018). In Sweden, the context of this study, it is emphasised in the Education Act that ‘Education should be based on a scientific ground and proven experienceFootnote1’ (Swedish Government Citation2010, §5). Even though there exist understandings of the concepts ‘scientific ground’ and ‘proven experience’ (central concepts of a research-based education), the law demand was actually framed in a rather vague way in the Education Act and was therefore left to education authorities and actors at the school level to decide how to enact it in practice (Rapp et al. Citation2017). In particular, proven experience is hard to define for teachers and principals, as the Education Act did not stipulate how much experience is needed and how it should be documented, analysed and spread to a wider audience in order to be regarded as proven (Bergmark and Hansson Citation2020).

As a consequence of the law, greater academic demands have been placed on teachers, implying that teachers should possess and apply academic knowledge in their teaching, extend their collaboration with researchers and study their own practice as researching teachers (Kyvik Citation2009). This can present a distinctive challenge for teachers who were educated when teacher education prioritised practical teacher knowledge rather than academic knowledge.Footnote2 It is therefore especially important to explore how experienced teachers work with research-based education, which may entail supplemental training to add academic knowledge to their existing professional teacher knowledge through various forms of professional learning initiatives. As the application of research into teachers’ work is a growing area of interest in contemporary education in an international perspective, the experience of Swedish teachers will be used to illustrate the content of teachers’ professional learning and how they learn and develop when moving towards a research-based education model.

Teachers’ professional learning

The way teachers learn and develop professionally has changed over time. Professional development has historically focused on single events, such as lectures and workshops led by external experts, to promote a teacher’s mastery of certain skills and competencies. Often, such development was based on a deficit approach: teachers are lacking the sufficient skills and knowledge and need to be educated by experts (Clarke and Hollingsworth Citation2002). This approach to professional development represents a top-down perspective and is designed independent of the teaching context and therefore risks being overly abstract and detached from school practice, which could hamper professional development and, in many cases, prove useless for teachers (Timperley Citation2011). Lloyd and Davis (Citation2018) among others, note that teacher professional development has been affected by performativity and accountability, which results in teachers’ limited ownership of the professional development processes and decreased relevance for teaching practice. Therefore, the authors argue for a pragmatic model of professional development that moves beyond performativity, emphasising purposeful professional learning directed to improved student outcomes. This is also in line with other approaches that emphasise a teacher’s professional learning, which stand in contrast to the ‘event-based’ professional development (Timperley Citation2011). These are collaborative approaches that are integrated into the daily work of teachers, context-specific and emanate from identified needs for teacher development – a bottom-up perspective (Opfer and Pedder Citation2011). These processes are also cyclical in nature and not predetermined, where teacher learning and development are dependent on the evolution of the process (Clarke and Hollingsworth Citation2002). They are also teacher-driven, purposeful for teaching practice and directed towards improving student learning (Lloyd and Davis Citation2018).

Action research represents one example of a professional learning process that is designed to be an integrated part of the teachers’ work. These processes are collaborative, based on teacher-identified areas, built on contemporary research and the experiences of teachers and their contextual knowledge. Such research seeks to bring together action and reflection as well as theory and practice (Reason and Bradbury Citation2008) and is often done in collaboration between teachers and academic researchers (Kemmis Citation2009, Scott et al. Citation2012). In schools, action research could represent one way to study and improve teaching and learning for both students and teachers, as it is considered an effective way to contribute to the professional learning of teachers (Noffke and Somekh Citation2013).

Against this backdrop, the focus of this paper is an exploration of the professional learning of experienced teachers who engage in action research as a way to meet the demand to establish research-based education. The specific aim is to analyse and problematise the content of the teachers’ professional learning and how they learn when working with action research projects. The research questions are: In what areas did the professional learning of teachers take place during the action research? What challenges did the teachers experience during the action research process? What contributed to the teachers’ professional learning?

Communities of practice and social learning

Work conducted within an action research process can be viewed as a community of practice (CoP),Footnote3 as discussed in previous research (Taylor et al. Citation2012, Ampartzaki et al. Citation2013). Learning is about more than knowledge acquisition, as it is also about creating a learning community where people can interact with one another and share experiences. According to Wenger (Citation1998), who argues that humans are social beings and learning takes place in a social context. Learning is ongoing and is about the ability to create meaning and understanding from our experiences. Our identities are developed and changed in learning processes, which involves a process of becoming. When learning contributes to the human process of becoming, it also supports meaning-making processes. The learning experience occurs in a relationship between the individual and the social world, and these have a mutual impact on each other (Farnsworth et al. Citation2016).

A CoP is situated in a historic and social context. Such a community is signified by joint domain, mutual engagement and shared repertoire. In the joint domain,Footnote4 people unify in a shared focus, which is the result of a process of negotiation. The domain is defined by the members of the community and is accordingly an integrated part of the same. Mutual engagement defines a CoP, which means that the members actively engage in the joint domain. The quality of mutuality does not imply consensus, rather, each individual is expected to have their unique role and place in the shared work. In a CoP, a shared repertoire is developed to move the joint domain forward. The repertoire can entail words, concepts, rules, routines, symbols and actions that are produced within the CoP, but these may also have been developed beforehand and used in this new context.

In their review of literature, Trabona et al. (Citation2019) point to problems related to CoPs, for example, a lack of time and investment in the processes, a lack of ability among members to adjust to collective decisions of the CoP, the risk that such a community could be resistant to change and that learning outcomes are preserved within the group rather than being disseminated to others outside the group. Wenger et al. (Citation2002) add to the list of challenges: a CoP can become a clique when relationships between the members are so strong, which can exclude potential new members. A CoP can be too large or too diffuse to really engage members, resulting in superficial engagement. Further, members of a CoP can depend too much on a coordinator or leader, which makes the community vulnerable and can result in the silencing of voices and member perspectives.

Methodology

The context of the study and participants

The context of this study was a municipality in Sweden with a special focus on supporting teachers’ and principals’ work to build research-based education, for example, through action research projects.Footnote5 Five action research projects were started in 2018–2019. I acted as a researcher and scientific supervisor in the action research, thereby contributing knowledge on theory and methods as well as guidance on how the teachers should carry out their projects.

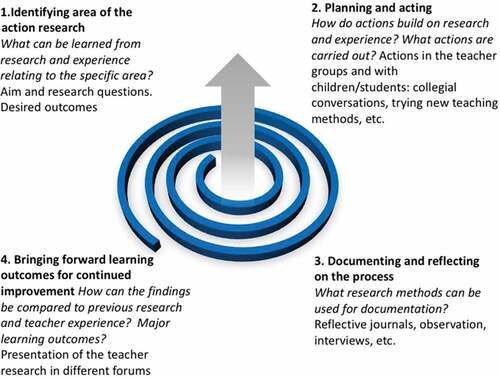

The action research related to multiple topics chosen by teachers working in preschool, compulsory and upper secondary school. Within the projects, 50 teachers participated and each project designated one teacher as a ‘lead teacher’.Footnote6 I supervised the projects in my role as a researcher over a 12-month period, which means that I actively supported and impacted the teachers’ work. I met with the teachers once a month for collegial conversations on different topics relating to different stages of the process. In addition to these meetings, the teachers also met in their own groups with the lead teachers responsible for leading the work. The processes in the action research were cyclical, inspired by the action research spiral: plan, act, observe and reflect, which has been presented in different forms in the history of action research (McNiff Citation2013). In below,Footnote7 the various phases of the action research projects are given. In all projects, teachers kept a reflective journal where they regularly recorded their own reflections (approximately once a week). The journal was treated as a private document. Based on different topics in the collegial conversations, teachers chose to share some of their reflections from the journal they wished to present for discussion. In many of the projects, the teachers also observed each other’s teaching, which is believed to be a good method to promote professional learning (Visone Citation2019).

One basic idea of action research is that it contains both research (‘knowledge generation’) and ‘personal and professional development’ (Noffke and Somekh Citation2013, p. 21). Therefore, action research processes will also be explored in research studies, such as this study. Informed consent was used in compliance with the legal requirements on ethical conduct (Swedish Government Citation2003). The teachers received information about the study orally and in writing informing them of the right to terminate their involvement in the study and that the data in the study will be treated as confidential. All teachers who participated in the study provided their consent.

Data collection and data analysis

On two occasions during the course of the action research, at mid-year and the end of the year, the teachers were invited to do a written reflection on what they had learned, what had helped them and how they wished to proceed. Written reflection provides opportunities for writers to examine their thoughts. Inviting people to write is a fruitful way to create understanding of a phenomenon. Writing enables writers to make thinking more public and explicit, visible on paper, which enables a researcher to study a phenomenon (van Manen Citation1997). In this specific case, the written reflections not only benefitted research processes but also the action research process itself.

There could be some potential weaknesses in the use of written reflections, since the analysis concentrates on what is written and how that can be interpreted. As a researcher, I cannot claim to know the intentions behind the words, unless they are described explicitly in the text. In addition, it was not possible to pose follow-up questions during the data collection. However, to address these possible weaknesses, I decided to use the lead teachers as intellectual contributors in the data analysis, thereby inviting them to give their contextual understanding and additional explanations (as described below). Despite these methodological challenges, the choice of data collection method could be regarded as sufficient based on the described procedures.

The written reflections were analysed using content analysis (Graneheim and Lundman Citation2004). As the researcher, I analysed the individual written teacher reflections with the research questions in mind and a focus on the outcomes of the teachers’ professional learning and how they learned. First, I read all the individual written teacher reflections to determine the unit of analysis: teachers’ professional learning through action research; the units of meaning: areas of learning, challenges during the learning process and aspects that contributed to their learning. These two phases facilitated the condensation of the data. Further along in the abstraction phase, similarities and differences were compared, which resulted in evolving themes.

As a follow up, I invited the lead teachers to reflect on my tentative analysis, which is a method used in action research (Reason and Bradbury Citation2008) that allows different voices to be heard and enables a contextual understanding of the data. The lead teachers were invited to reflect on the questions: Do you recognise yourself in the findings? Were some aspects you found important during the action research process missing or not clearly expressed? If you were to write the discussion, what are the main findings you would emphasise? The teachers wrote down their reflections which was used as data. Overall, the lead teachers confirmed my tentative analysis. They recognised themselves. ‘Yes, especially the major features: that it is a group that had collaborated, working towards a shared goal. Despite the diversity in teaching groups and levels, the findings show that all express a visible and increased professionalism’ (lead teacher reflection). However, the teachers also added additional nuance to the analysis, which was integrated in the final analysis presented in the findings section below.

Findings

Changes in ways of thinking, acting and relating to others in teaching, research and collaboration

The content of the teachers’ professional learning included changes in thinking, acting and relating to others in three areas: teaching, research and collaboration.

Teaching

Changes in the ways of thinking, acting and relating to others in the area of teaching were connected to the teacher role and teaching methods. The teachers perceived that they expanded the ways they think about and understand themselves as teachers and the ways they can change their teaching. In many of the projects, the process started with an investigation of a teacher’s current approach to teaching. This served as a baseline upon which change actions could be enacted. For example, this first mapping resulted in insights like: ‘I have gained the insight that my goal has been to found my teaching on the right learning theories, but in reality, the learning theories shift depending on what you do’ (Preschool Teacher 5).

Teachers reflected on the situated nature of teaching: the fact that many factors impact teaching and learning and their use of diverse methods and learning theories depending on the situation at hand. Writing in the reflective journal contributed to the teachers’ increased awareness. ‘Writing in the reflective journal in a structured way has developed my teaching, and I have been aware of things I previously had not seen, for example, silent students’ (Compulsory School Teacher 17).

The teachers perceived they developed in their teaching role, learned to negotiate between leading processes and were able to allow children and students to participate in and influence the teaching process to a greater extent. One teacher wrote:

Previously, I have felt uncertainty regarding the teaching and letting the children explore by themselves. I have not wanted to govern them too much, but at the same time realised that I cannot leave them on their own … I have reflected on and discussed this with my colleagues … and now I feel more satisfied to direct the children based on my purpose for the activity … as long as the work is based on their experiences and they can relate to these (Preschool Teacher 13).

The teachers have become more flexible and responsive to the students and the teaching situation, thereby developing their teaching. ‘I have developed my flexibility, which is about adjusting to different situations, different students, different texts and different tasks and daring to let go of detailed plans. I have also dared to invite the students in the planning where it was possible’ (Upper Secondary School Teacher 2). Increased student participation included involving students to a higher degree in the lesson plans and making more room for student opinions to impact teaching. The quote underlines the change in the teacher’s actions and, by extension professional learning: distributing the power of influence to the students, without giving up the leading role as teacher.

Through the action research, the teachers have tried new ways of teaching. ‘It feels like my curiosity to try new teaching methods has grown. Above all, it does not stop with curiosity, but I dare to try as well’ (Compulsory School Teacher 5). The quote reflects the connection between thinking and acting in teachers’ professional learning. The introduction of new methods has resulted in the development of teaching.

Issues connected to the teaching context could relate to the problem of engaging all students in the lesson and the fact that the ‘perfect lesson’ does not exist. ‘The ultimate literary conversation might not exist in reality but is nothing more than a pipe dream. The well-known expression ”begin to find one’s feet” could work as a metaphor for how I perceive my newly developed profession’ (Upper Secondary School Teacher 6). This quote underlines the high expectation this teacher has on his or her teaching and the fact that the development of a teacher’s knowledge of his or her craft is in constant development. Professional learning takes time, effort and critical reflection in order to make a difference in practice.

Research

Changes in the ways of thinking, acting and relating to others in the area of research included research processes in schools and the role of reflection. The development of an understanding of concepts relating to the new Education Act mandate was highlighted. ‘The word “research” felt big, and I did not exactly know what was expected of me. Now, after some time, I don’t grasp everything, but it feels like I am going to have use of it in my teaching practice’ (Compulsory School Teacher 9). Here, the connection between the two areas research and teaching is underlined, emphasising the potential offered by using research to develop one’s practice. The fear of research was also underlined by the lead teacher group in their reflections: ‘In the beginning, we experienced that many of the teachers were afraid of and unsure how to work with research’. Despite the initial hesitation, the teachers managed to cope with this new task. ‘I have managed to develop my scientific competency (hurray), despite resistance to all complicated words and complex texts, but now I understand most of it’ (Compulsory School Teacher 4). The teachers also gained an understanding of research results in the specific area of the action research, which offered an opportunity to connect their teaching to research results. ‘During the action research, I feel it is easier to understand and use research while you can relate to the teaching you are doing’ (Compulsory School Teacher 16). Existing research also reaffirmed the teachers’ proven experience, which resulted in trust in their own competence.

During the action research, the teachers also developed their understanding of different methodologies, learned how to use different research methods for documentation and discovered that an analysis of teaching can help them gain a deeper understanding of the teaching process. Again, the connection between teaching and research is emphasised in the teachers’ professional learning. The teachers have learned the value of reflection as a scientific resource and developed a positive attitude towards the use of different tools to explore their teaching practice, for example, through documentation. ‘Reflection is essential. Being aware that I am aware is an especially important quality if you want to learn, or at least to avoid making the same mistake over and over again’. (Upper Secondary School Teacher 6).

Reflecting in the journal and being consistent in one’s writing was seen as a difficult task in beginning. For example, one teacher wrote:

In the beginning of the project, I found it hard to start reflecting in my journal, and I had to struggle to take the time to do it. Now I have created a routine that works for me, and I think it is very positive to read it afterwards. My ambition, however, is to get better in deepening my reflections, as I think that they sometimes are too scanty now (Compulsory School Teacher 11).

It seems like this teacher has overcome this challenge, as a routine was created, and the teacher perceived the benefit of writing in the journal. This teacher now wishes to take the reflection one step further. As emphasised earlier, the development of teaching takes time; likewise the professional learning using research methods requires practice before these methods can be used regularly by teachers.

Many of the teachers have used reflection earlier in their careers, but this was often in oral form. In the action research, they were encouraged to reflect in writing, which promoted a deeper reflection on their own teaching – understanding the present but also finding ways to improve their teaching. The reflection allowed teachers to put their own teaching into words and connect it to scientific concepts that describe their practice, which enabled a critical reflection and analysis of the same. One teacher wrote:

I think I have learnt additional concepts that I can use in professional conversations. Through the action research, we have had the opportunity to talk, reflect and analyse together, and by that, verbalised what we do in a completely different way. In turn, this supports a view of teaching from different angles, which gives depth and diversity (Preschool Teacher 12).

Another procedural problem related to the use of tools for reflection was observation in teaching practice: ‘A difficulty I have experienced is knowing what to observe and reflect on and how to best do this (Compulsory School Teacher 11). Here, it is important for the teacher to find ways to know what to observe and how to do it. Even though it was a challenge in the beginning, the teachers developed their practice and confidence in the use of scientific tools, such as reflective journals, and mutual observation. ‘Now I feel I have improved my skills in documenting my reflections thanks to the structured reflective journal’ (Compulsory School Teacher 16), and ‘I feel more confident now when I am going to observe someone, i.e. to know what to look for and evaluate. I am not as tense as I used to be when I am observed now; more prepared and relaxed’ (Compulsory School Teacher 11).

The teachers have also practiced an entire research process, from formulating questions, collecting and analysing data to presenting their findings. One teacher wrote: ‘I have become more skilled in the practical work of research: formulating interview questions and doing interviews, transcribing and analysing data. I have found a way to work scientifically, which I can use in other areas we want to develop’ (Upper Secondary School Teacher 2).

According to the syllabus in the upper secondary school, students are to develop an understanding of concepts in literary science and be able to use them in practice. Previously, the teachers found it somewhat difficult to find a natural way to include scientific concepts in their teaching of literature, but regular, shared conversations about literature have contributed to students’ learning and use of scientific concepts relating to literature. ‘The students have started to use the scientific literary concepts and are sometimes able to express themselves in new ways through the way we are working’ (Upper Secondary School Teacher 5).

In terms of their ability to build a research-based education, some teachers find that it takes time, but that they are on their way. ‘I think I have come a long way in developing competences related to the action research project, but you’ll never get fully-trained in these areas’ (Preschool Teacher 1). Another teacher stated:

Since I am a slow person, it takes time for me to apply theory into practice. I am still processing all the theoretical knowledge I have gained in order to put into practice. The last article I read made many pieces of the puzzle come together (Compulsory School Teacher 12).

The lead teachers also underlined the fact that building research-based education is a work in progress: ‘We sure have developed and learnt, while we are not full-fledged, we are well on the way’ (lead teacher reflection). The quote emphasises the importance of time in the processing of knowledge. However, the teachers realised that they have employed multiple tools and resources that they will use in coming improvement processes. They have developed knowledge and competence that is useful in the long-term.

Collaboration

Changes in ways of thinking, acting and relating to others in the area of collaboration included the role of relationships in teaching and the importance of collaborating with students, colleagues and researchers. Collaboration can be seen as a driving force in professional development, promoting the professional learning of teaching and research. The action research has contributed to an understanding of what collaboration means and also resulted in creating refined bonds with students and increased participation. ‘I have become more aware about the relationship between me and the students. How do I engage with the students? How do I encourage? How do I “criticise”?’ (Compulsory School Teacher 1). Some teachers realised that they already had skills in establishing relationships with students but gained a deeper awareness of this process. ‘My strength has been to inspire, enthuse and create relationships. Now, more than before, I realise my competence in this area’ (Upper Secondary School Teacher 4). Another teacher reflected on how the relational perspective in teaching has gained attention within the whole group. ‘The relational competence has been a more present part of our working life, a continual reminder of how we treat each other and the students. This focus has changed a lot’ (Compulsory School Teacher 4). The action research has also promoted additional actions which resulted in the establishment of enhanced relationships with students.

Through this working form [literary conversations], I have had weekly lessons with the students, and it has really supported the creation of relationships. I have a new student group and did not know anything about them. Thanks to the fact that we could have the conversations on literature in small groups, I feel I have created better relationships with them. A safer and more comfortable environment makes the students more accepting and supportive to each other (Upper Secondary School Teacher 5).

In this quote, it is emphasised that the conversations concerning literature were especially important when the teacher met with a new group. Also, relationships were created when students stepped forward and shared their thoughts – it became a meeting between human beings, beyond meetings between students and teachers. A teacher reflected on the relational perspective when introducing new teaching methods: ‘Actively working with student participation and an appreciative approach have strengthened my relationship with the students … I have felt positive energy from many students and the joy of success’ (Compulsory School Teacher 3).

The action research has also strengthened collaboration among colleagues and the researcher. The teachers have seen the importance of the teacher community as a place for shared reflection, promoting persistence and allowing each other to experiment and try new things while they learn about their teaching.

I am struck by the fact that much of the work went as planned, but we had a greater need for each other than first anticipated. The weeks of individual reflections have gradually turned into, ‘We might meet each other anyway’. The collegial feel has meant a lot. I can see that we have helped each other to be persistent and achieve our goals (Upper Secondary Teacher 2).

In the preschool groups, the collegial conversations deepened the knowledge of ‘teaching’, which is a newly introduced concept in the Swedish preschool. ‘I think it has been really helpful to discuss with my colleagues how we understand the concepts relating to learning: what does teaching, education and learning mean to us?’ (Preschool Teacher 6). Here, the connections between the themes of collaboration and teaching were visible, as the preschool teachers expanded their views and knowledge about teaching when reflecting together in the action research project. The collegial conversations also strengthened the common ground between teachers who teach different subjects. ‘I have discovered that we have more in common in our teaching than I previous believed, for example, the same challenges, and it has been easier to discuss these common denominators’ (Compulsory School Teacher 3).

The collaboration resulted in changes in actions, for example, a higher degree of engagement in conversations between teachers and researchers and the creation of deeper relationships within the groups. ‘We have become more comfortable with each other in another way; we are comfortable observing and being observed. Our group has been united through regular conversations, which had not happened otherwise’ (Compulsory School Teacher 18). Thus, the action research has created the conditions for and a forum for building relationships within a community, described as a place where teachers feel they can be honest and ask for support and help. ‘Collegial learning does not have to be something threatening, but a place where I can disclose my weaknesses and get help moving forward’ (Compulsory School Teacher 5). It is evident that vulnerability may be an important aspect for teachers in their professional learning. It is also emphasised that feedback is more easily given and more effective in a safe environment: ‘We have been open and honest with each other, dared to open up to others and critically review each other and ourselves to become stronger as teachers’ (Preschool Teacher 2).

The relationships within the different action research groups have been strengthened, but also the relationships to the principals who have supported the work. The action research also promoted increased collaboration with the researcher, which resulted in the acquisition of new skills. ‘From the researcher, I have learned different methods for conversations’ (Compulsory School Teacher 19). The collaboration with the researcher also had a positive impact on teaching. ‘Collaboration between teachers and researchers is extremely fruitful also in practice (not just in theory)’ (Upper Secondary School Teacher 2). The question of creating an open and permissive climate, as described above, also related to the fact that teachers felt comfortable making themselves vulnerable and asking questions of any kind. ‘I have discovered how comfortable it is when a supervisor lets you bring up various “stupid” thoughts and still views them with curiosity and respect’ (Compulsory School Teacher 4). It seems that no question is too little; all questions deserve attention and should be taken seriously.

In the collaboration, some teachers sometimes found it difficult to free up time for collegial conversations. ‘From time to time, it has been difficult to find time and space for collegial meetings. It may have been even more important in the beginning of the process when action research and the specific method of conversing with children was new’ (Preschool Teacher 1). Another challenge relating to collaboration was the question of what will happen after the projects are finished and the need for some form of continued supervision. ‘In the future, it would be really good to have someone who leads us in the research; it will be difficult in the teacher groups to do it ourselves due to lack of time and heavy workload’ (Lead teacher reflection). Also, the teachers expressed a wish to continue with the processes that started within the action research, but with the inclusion of additional colleagues: ‘One challenge is to involve all colleagues, to continue to enthuse and inspire’ (Preschool Teacher 14).

To sum up, the content of the teachers’ professional learning focused on changes in ways of thinking, acting and relating to others in teaching, research and collaboration. The analysis has shown that the three areas are interrelated and can affect each other mutually. Changes in one area might result in development in another area. For example, when the teachers developed their learning of research results, it resulted in changed teaching or deepened collaboration with others. It could also start with changes in one of the two other areas, thereby affecting the other areas.

Aspects contributing to teachers’ professional learning

There are different aspects, such as human, scientific, as well as practical and organisational resources, that contributed to the teachers’ professional learning – which reflect how the teachers learned.

The human resources related to relationships with others and conversations with colleagues, principals and the researcher. Reflection has been an important part of the conversations in the groups, which has supported the teachers’ exchange of experiences and knowledge. ‘The shared meetings where we talked about challenges and joys and gave each other ideas for the continuation of the work has supported my learning’ (Upper Secondary School Teacher 10). Especially important were the reflective questions that the researcher presented along with the experience of doing the research itself: ‘The researcher has, with her experience, been the backbone of the project. She has helped us move on when we were stuck’ (Compulsory School Teacher 19). In the lead teachers’ reflections on the findings, the role of the researcher was further emphasised.

The important role of the researcher, without such a person there would be no action research … through the researcher, we get help seeing things from an outside perspective. We are so caught up in our everyday practice, and the researcher has helped us broaden the perspectives, which is hard to achieve otherwise (lead teacher reflection).

The scientific resources related to the ability to use scientific tools, for example, reading and discussing research literature, participating in lectures, observing, writing reflective journals, transcribing and analysing. Three teachers summarised it like this: ‘We have read relevant literature for our profession. Also valuable were lectures on teaching and action research’ (Preschool Teacher 6), ‘The observations and analyses have absolutely contributed to my learning’ (Compulsory School Teacher 11) and ‘Despite the challenges with writing in the reflective journal … being ‘compelled’ to write more about teaching has contributed to my learning (Compulsory School Teacher 6).

The lead teachers had a special task to work together with the researcher to be responsible for gathering data, through recording the collegial conversations, then transcribing and analysing the data. This process allowed the lead teachers to experience the research first-hand. ‘As I also was able to participate in the process (analysis of gathered data and so on), I think it has been helpful for my own professional development, as I got additional opportunities to reflect and analyse what I do and what we do together’ (Preschool Teacher 12). Being a lead teacher allowed the teacher to understand the phenomenon being researched both from the perspective of a teacher and a researcher, which gave additional perspectives.

The practical and organisational resources related to time, regularity, digital technology, a shared focus and planning as well as ensuring the process was teacher driven. The groups gathered on a regular basis for shared reflection, which is something important for the success of the projects. ‘The regular collegial meetings, where we followed an explicit plan but at the same time gave room for other discussions … That we had time in our schedule to work with the action research; it has meant a lot’ (Compulsory School Teacher 3). Another practical and organisational resource that was brought up in the lead teachers’ reflection was the use of digital technology.

The digital technology became important for us, something we were forced to try. Now we use a digital platform for communication between teachers but also when we try new teaching methods. We had not done that before, and if we had not been part of an action research project, we still would be analogue (lead teacher reflection).

The teachers emphasised the role of their principals in providing the conditions needed for participation in the action research. A shared focus and working with a long-term focus, were also factors that supported the teachers’ learning. ‘A structure on how we should proceed with both short and long-term goals also helps the development’ (Compulsory School Teacher 4). Having a shared focus provides direction and endurance in a process.

Participating in a project has kept me “on track”. Probably, I could not have kept this focus with the students if I were not part of this project. When lessons do not go as planned, it is easy to end, but this [the action research] has made me continue. I have been relaxed and felt ok, no stress (Upper Secondary School Teacher 14).

The bottom-up perspective was of particular importance for the teachers’ engagement and learning in the action research.

One thing that impacted positively on teachers’ learning was the fact that the projects were based on the teachers’ questions and that, right from the start, they were relevant and legitimate … the projects have been clearly integrated in the teaching … we have felt ownership, and we have talked about the bottom-up perspective and the feeling it gives (lead teacher reflection).

Discussion

The experienced teachers’ learning was signified by a holistic and social view of learning, as it related to cognitive (thinking), behavioural (acting) and relational (relating to others) aspects. As Wenger (Citation1998) claims, learning involves social processes of creating meaning and understanding experiences. The teachers in this study participated in the meaning-making of what research-based education means in their practice and how they can enact it. This resulted in greater understanding and improvement in their teaching as they negotiated and changed their teacher role and tried out new teaching methods. Even though the teachers were experienced, their professional learning in the area of teaching was tangible. As the teachers completed their education before the mandate in the Education Act was introduced, the introduction of research in preschool, compulsory and upper secondary school was seen, in part, as something new and therefore also a challenge. However, the action research contributed to the teachers’ learning in this area as they interpreted, negotiated and enacted the concepts relating to the mandate: scientific foundation and proven experience. They developed a professional language to talk about research in their practice but also improved their use of scientific methods in their teaching. The teachers’ professional learning also involved an awareness of the importance of and strengthened collaboration with children/students, colleagues and the researcher. Accordingly, the value of a community was highlighted. This is in line with Trust and Horrocks (Citation2017), who state that teachers’ engagement in a learning community supports teachers’ changed beliefs and practices and is transformative in nature. The transformation, or the change in the ways teachers think, act and relate to others, had an impact on teachers’ identities as teachers, as they were able to expand their knowledge in these three areas. This transformation involved a process of becoming more skilled in applying a research-based approach to teaching. In just one year, the teachers have come a long way towards the realisation of a research-based education system. However, change takes time and learning and development will continue, meaning – this is a work in progress (Farnsworth et al. Citation2016). Also, the teacher groups represented parts of the whole group of staff in their respective schools or preschools, which means that the work to build a research-based education is ongoing. The necessity to involve additional colleagues in the development of a research-based education is addressed by the teachers; however, this is described as a challenge that demands new initiatives.

Professional learning took place in and was supported by a specific social context, a CoP (Wenger Citation1998). The five action research projects have respectively functioned as a joint domain with clearly defined goals, negotiated by the members of the respective project and manifested by the teachers’ desire for professional development and learning and accompanied by the support offered by the researcher. Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) emphasise belonging to a community as one important step in learning, which was evident in the action research as the teachers identified themselves as part of a group that was clearly defined in comparison to other groups in their practice. Being part of a group as a teacher might also lead to exclusion of others, which might be a disadvantage of CoPs. Therefore, the issue of inclusion–exclusion has to be considered when working with professional development in defined groups such as an action research project. According to Wenger (Citation1998), the development of a CoP could have both positive and negative effects. Overall, the teachers’ experiences working with action research was mostly positive, which can be attributed to certain aspects: participation was voluntary, the teachers were motivated and held high expectations of what could be achieved through the action research. However, the teachers also experienced obstacles and challenges, such as difficulties finding ways to reflect in their journals on a regular basis, observing each other’s teaching and finding time to work with the action research. Visone (Citation2019), who studied peer observation as professional learning, also found that negative emotions, such as anxiety, could be connected to the collegial visits; but the benefits of learning from each other outweighed the challenges, which created an incentive to make peer observations a part of the teachers’ learning on a regular basis. The teachers in this study, together with the researcher, were able to negotiate and fine-tune the processes based on their needs and wants – allowing the professional learning to take time and develop along the way. This reaffirms the findings of Tannehill and MacPhail (Citation2017), who also discovered that teachers in their study highlighted the positive experiences and challenges as evidence of professional learning and development of the community. Accordingly, challenges can also be seen as something self-evident and natural but can be handled within a CoP as the process evolves (Wenger et al. Citation2002). It is therefore important to bring problems to the surface of a professional development process, which creates opportunities to deal with them during the lifetime of a project. The study also suggests that challenges that arise during action research projects may be viewed as a natural part of the learning processes and something that is important to highlight and handle within the CoP. Based on this study, strategies used to deal with challenges or problems were conversations between the teachers and the researcher and between colleagues, and reflective writing in journals.

Mutual engagement is signified by the teachers’ and the researcher’s buy-in and active involvement in a shared project. Based on the findings, the members of the community were committed and invested time and energy in the projects. They also shared both the successes and the problems and challenges with each other, which was signified by in-depth conversations on practice, further strengthening collaboration and collegiality. The mutual engagement also resulted in increased perseverance among teachers when facing problems, where rather than giving up, they showed resilience in their efforts and maintained a focus on the goals. They emphasised the importance of the researcher in supporting their professional learning and engagement in the process. Trabona et al. (Citation2019), who studied teachers’ development within prescriptive CoPs with structural protocols driven by task accomplishment, revealed that the processes resulted in superficial meaning-making rather than in-depth conversations on practice. Therefore, the authors argue for professional development initiatives based on teachers’ authentic questions, their engagement in the process and belonging to a community of teachers. In this study, the teachers’ own questions were central to the action research projects. Also, engagement in the processes was expected both from the teachers and the researcher. On a general level, the processes appeared to show evidence of engagement, but it is difficult to determine if all individuals were engaged. Therefore, it may be of interest to further explore engagement on the collective and individual level.

The teachers used a shared repertoire – different forms of collegial meetings as a routine, all teachers kept a reflective journal and teachers observed each other’s teaching. These resources have been used on a regular basis, which has moved each project forward towards the goals. The teachers also experienced some of the challenges of CoPs that are described in the literature, for example, issues relating to time constraints (Trabona et al. Citation2019). Based on the teachers’ own reflections, stress and workload were problems they sometimes encountered, though these were not a significant issue since as a condition for participating in the action research, principals put aside time and space within the teachers’ working hours. Other challenges related to changes in conditions for participation in action research as well as difficulties in learning the skills needed to take a scientific approach and resisting the urge to give up when it takes time to learn new things. Again, this signals the importance of voicing problems and challenges. The problems and challenges might help develop skills and competences.

As the researcher’s support was vital for the teachers’ professional learning, it can make teachers vulnerable to the continued reliance on a researcher’s competence and support in the long-run if the teachers engage in new action research processes on other topics. In the worst case scenario, it could result in the deprofessionalisation of teachers if they come to expect the support of a researcher. This support may be needed in the beginning, when teachers first enter into action research, but in due time, the teachers can lead processes themselves. Here, the lead teachers could play a significant part by taking on the role of facilitators, as they could offer their support to colleagues, thereby strengthening teachers’ professional learning (Trabona et al. Citation2019). It is evident, based on the findings here, that an action research process can be demanding while requiring engagement from individuals on multiple levels of the educational system: the principals – who are creating the conditions for teachers’ participation (time and other resources), the lead teachers- who support their colleagues and act as an intermediate for a researcher, the teachers – who incorporate the work into their teaching practice and the researcher – who facilitates the process. If such an engagement, one with leadership on multiple levels, can be realised, sustainability of the community is promoted, fostering an effective knowledge system (Wenger et al. Citation2002).

According to the literature on professional development, teachers’ learning is directed at improving both teaching skills to teach and student outcomes (Clarke and Hollingsworth Citation2002, Timperley Citation2011). However, within the scope of this article, this study has explicitly focused on teachers’ professional development and learning and not on exploring student outcomes, which may be considered as a limitation. Therefore, it would be of interest to highlight the students’ perspectives and experiences in future studies in relation to teachers’ professional learning.

Conclusions

When building a research-based education, this study offers insights into the content of professional learning – what teachers learned, but also how teachers learned. Teachers learned about three areas: teaching, research and collaboration. Important contributors to their learning were human, scientific, practical and organisational resources. The action research on the establishment of research-based education was based on the teachers’ own questions and desire to improve their own teaching, thus constituting a context-specific approach and starting from a bottom-up perspective (Timperley Citation2011). The processes were cyclical in nature and evolved over time. The process itself informed what the next steps would be and challenges that aroused were handled underway (cf. Clarke and Hollingsworth Citation2002). Further, the teachers’ professional learning was integrated in their work (Opfer and Pedder Citation2011) and was collaborative in nature as the teachers engaged in a community of practice with a joint domain, mutual engagement and shared repertoire (Wenger Citation1998). This study points to the need for engagement on multiple levels – principals, lead teachers, teachers and researchers – if the building of a research-based education model is to be successful and sustainable. Lastly, the role of the teachers’ themselves cannot be underestimated. This study suggests that successful professional development is dependent on teacher ownership and ensuring that the processes are teacher-driven.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Scientific ground can be explained as being research-based knowledge, which represents ‘knowledge developed through a research process … based on analyses of systematic data’. Proven experience can be described as practice-based knowledge, which is ‘based on experiences related to specific actions and contexts’ (Wahlgren and Aarkrog Citation2020, p. 2). The concept of ‘proven experience’ can also be linked to the international concept of ‘best practice’, and ideas of ‘what works’. The policy of research-based education can be traced to different traditions of education: for example, evidence-based and evidence-informed teaching, but it is not the focus of this paper to explore the origin of these traditions (see Bergmark and Hansson Citation2020 for further readings). The focus of this paper is teachers’ professional learning when building a research-based education.

2. Teacher education was formally included in Swedish higher education structures in 1977. Practically, the previous separation of different teacher education programmes continued in a divided system, with some courses conducted in the old teacher education seminaries or colleges and others within the university. New teacher education reforms took effect in 2001 and 2008, with an increased focus on building an education, both in teacher education and schools, based on science and proven experience (Erixon Arreman Citation2005).

3. A concept developed by Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) and further developed in Wenger (Citation1998).

4. In later writings, Wenger-Trayner uses the term ‘domain’ instead of ‘enterprise’ to make a clearer distinction between a CoP and a team: ‘… “domain” is the term that I use now to define the area in which a community claims to have legitimacy to define competence. A team is defined by a joint task, something they have to accomplish together. It is a task-driven partnership, whereas a community of practice is a learning partnership related to a domain of practice’ (Farnsworth et al. Citation2016, p. 143).

5. In the education department of the municipality, a scientific leader position and a scientific board have been established, which are intended to support research activities in schools and form structures for school development and the professional development of teachers. The municipality has also hired an in-house researcher (the author of this paper) who studies and promotes the integration of research in schools. Part of the in-house researcher’s work is to lead action research projects.

6. Of the 50 teachers, 15 worked in preschool, 20 in compulsory school and 15 in the upper secondary school; 45 were female and five were male. All teachers have completed an academic teacher education programme.

7. When presenting working flows in models, it is important to state that the processes are not as static or rational as a model may imply. In our case, it meant that the overall process followed the four phases, but in some parts of the processes, we returned to a previous phase before moving forward again. The oscillation between phases two and three was the most common.

References

- Ampartzaki, M., et al., 2013. Communities of practice and participatory action research: the formation of a synergy for the development of museum programmes for early childhood. Educational action research, 21 (1), 4–27. doi:10.1080/09650792.2013.761920.

- Bergmark, U. and Hansson, K., 2020. How teachers and principals enact the policy of building education in Sweden on a scientific foundation and proven experience: challenges and opportunities. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. doi:10.1080/00313831.2020.1713883.

- Cain, T., 2015. Teachers’ engagement with published research: addressing the knowledge problem. The curriculum journal, 26 (3), 488–509. doi:10.1080/09585176.2015.1020820.

- Clarke, D. and Hollingsworth, H., 2002. Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and teacher education, 18, 947–967. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00053-7

- Erixon Arreman, I., 2005. Research as power and knowledge: struggles over research in teacher education. Journal of education for teaching, 31 (3), 215–235. doi:10.1080/02607470500169055.

- Farnsworth, V., Kleanthous, I., and Wenger-Trayner, E., 2016. Communities of practice as a social theory of learning: a conversation with Etienne Wenger. British journal of educational studies, 64 (2), 139–160. doi:10.1080/00071005.2015.1133799.

- Graneheim, U.H. and Lundman, B., 2004. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse education today, 24 (2), 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Kemmis, S., 2009. Action research as a practice‐based practice. Educational action research, 17 (3), 463–474. doi:10.1080/09650790903093284.

- Kyvik, S., 2009. The dynamics of change in higher education: expansion and contraction in an organisational field. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Lambirth, A., et al., 2019. Teacher-led professional development through a model of action research, collaboration and facilitation. Professional development in education, 1–19. doi:10.1080/19415257.2019.1685565.

- Lave, J. and Wenger, E., 1991. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Learning by doing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lloyd, M. and Davis, J.P., 2018. Beyond performativity: A pragmatic model of teacher professional learning. Professional Development in Education, 44 (1), 92–106. doi:10.1080/19415257.2017.1398181.

- McNiff, J., 2013. Action research. Principles and practice. 3rd ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- Noffke, S.E. and Somekh, B., eds, 2013. The SAGE handbook of educational action research. London: SAGE.

- Opfer, V.D. and Pedder, D., 2011. Conceptualizing teacher professional learning. Review of educational research, 81 (3), 376–407. doi:10.3102/0034654311413609.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2018. Teaching in focus. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Rapp, S., Segolsson, M., and Kroksmark, T., 2017. The education act: conditions for a research-based school. A frame-factor theoretical thinking. International journal of research and education, 2 (2), 1–13.

- Reason, P. and Bradbury, H., 2008. The SAGE handbook of action research. Participative inquiry and practice. 2nded. London: Sage Publications.

- Scott, A., Clarkson, P., and McDonough, A., 2012. Professional learning and action research: early career teachers reflect on their practice. Mathematics education research journal, 24, 129–151. doi:10.1007/s13394-012-0035-6

- Swedish Government, 2003. SFS 2003: 460.Lag om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor [Law about ethical vetting of research concerning human beings]. Stockholm: Swedish Government.

- Swedish Government, 2010. SFS 2010:800. Skollagen [Education Act]. Stockholm: Ministry of Education.

- Tannehill, D. and MacPhail, A., 2017. Teacher empowerment through engagement in a learning community in Ireland: working across disadvantaged schools. Professional development in education, 43 (3), 334–352. doi:10.1080/19415257.2016.1183508.

- Taylor, A., et al., 2012. Reconceiving with action research: working within and across communities of practice in a university/community college collaborative venture. Educational action research, 20 (3), 333–351. doi:10.1080/09650792.2012.697390.

- Timperley, H., 2011. Realizing the power of professional learning. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Trabona, K., et al., 2019. Collaborative professional learning: cultivating science teacher leaders through vertical communities of practice. Professional development in education, 45 (3), 472–487. doi:10.1080/19415257.2019.1591482.

- Trust, T. and Horrocks, B., 2017. ‘I never feel alone in my classroom’: teacher professional growth within a blended community of practice. Professional development in education, 43 (4), 645–665. doi:10.1080/19415257.2016.1233507.

- van Manen, M., 1997. Researching lived experience. Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Ontario: Althouse Press.

- Visone, J.D., 2019. What teachers never have time to do: peer observation as professional learning. Professional development in education, 1–15. doi:10.1080/19415257.2019.1694054.

- Wahlgren, B. and Aarkrog, V., 2020. Bridging the gap between research and practice: how teachers use research-based knowledge. Educational action research, 1–15. doi:10.1080/09650792.2020.1724169.

- Wenger, E., 1998. Communities of practice. Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E., McDermott, R., and Snyder, W.M., 2002. Cultivating communities of practice. A guide to managing knowledge. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.