Abstract

Management culture shapes economic performance in social enterprises. Entrepreneurial orientation, taking care of the internal communication culture and a good anchoring of organisational goals and strategies lead to high achievement in a broad range of economic goals. These findings are based on a survey of 257 Swiss social enterprises. The statistical analyses reveal that the relevance of the elements of management culture differs from one performance criterion to another. This leads to important practical implications that are discussed in the light of a shifting welfare regime, in which SEs are increasingly under pressure to act in a pro‐business and pro-market manner.

Introduction

Social enterprises (SEs) delivering services in the educational, cultural, health, and social sectors to either society as a whole or to disadvantaged groups find themselves under increasing pressure to prove their credentials. Intensified competition for dwindling public funds and donations (Dees Citation1998; Haugh Citation2007; Weerawardena and Mort Citation2006) drives them to earn increasing shares of their budget from marketable services (LeRoux Citation2005; Suykens, De Rynck, and Verschuere Citation2019). Neoconservative, pro‐business, and pro-market ideological and political values have become guiding principles for many SEs and they are being increasingly understood and practiced in narrower commercial and revenue‐generation terms (Dart Citation2004). SEs are expected to incorporate proven business concepts to demonstrate their professionalism (Lu and Park Citation2018). This trend is especially noticeable in countries with well-developed welfare structures (Erpf, Bryer, et al. Citation2019), where SEs are under increasing pressure not only to be socially committed but also increasingly to be economically oriented (Bull and Crompton Citation2006). In other words, their social effectiveness is traditionally recognised, while their economic effectiveness and efficiency are increasingly questioned.

The political or social question of how meaningful these developments are will not be answered here. What we want to address are the questions of how SEs can meet these requirements, how they can be economically successful, and with which organisational management measures they can influence their performance. This leads us to the central research question of this article:

Which Aspects of Management Culture Lead to Economic Performance of SEs?

This study contributes to the literature and practice on SEs in three ways:

Systematic and statistically-based performance measurement with its determinants in SEs is a field that still lacks systematic investigation (e.g. Arena, Azzone, and Bengo Citation2015). SE research and the literature on social entrepreneurship especially include only a few publications that conceptually discuss and empirically examine the relationship between management culture and economic performance since research on SEs is still overwhelmingly dominated by conceptual contributions and qualitative case studies while only a small number of studies employ quantitative methods (Gupta et al. Citation2020; Sassmannshausen and Volkmann Citation2018; Short, Moss, and Lumpkin Citation2009). The present study develops an original research model and tests it in a quantitative manner.

This study echoes the current academic discussion that considers entrepreneurial orientation (EO) as a possible solution for SEs to meet the demand for intensified economic performance (Alarifi, Robson, and Kromidha Citation2019; Lurtz and Kreutzer Citation2017). It is considered whether this approach could lead SEs to become more entrepreneurial and develop organisational cultures that enable them to respond to changing conditions with flexibility and innovation and to open up new fields of activity and working methods.

This contribution provides very concrete recommendations for the practice and its leaders of SEs and says which aspects of a management culture they can promote to be economically successful.

Current State of Research on Factors Enabling Performance for Social Enterprises

Research on SEs and social entrepreneurship in the last years has frequently focussed on the relationship between economic and social goals (Alegre Citation2015). The initial assumption was that management and staff members predominantly experience conflicts around goals and that this weakens the achievement of the organisation’s social mission overall. For example, the study by Stevens, Moray, and Bruneel (Citation2015) demonstrates a negative correlation between social and economic missions. However, recent studies demonstrating how social and economic goals can be mutually dependent and even support each other have achieved prominence (Child Citation2016; Di Zhang and Swanson Citation2013; Erpf, Ripper, et al. Citation2019; Fitzgerald and Shepherd Citation2018; Smith et al. Citation2010).

Miller-Stevens et al. (Citation2018) investigated the degree to which the values of managers of profit-oriented SEs differ from those of managers of classic NPOs in the USA. The NPO managers put a stronger emphasis on service orientation, charity and altruism, integrity and justice as well as responsibility, but also efficacy and efficiency. Managers from profit-oriented SEs rated themselves higher on only two values, namely entrepreneurship and innovation. There were no significant differences in values like transparency, equality and fairness, flexibility, freedom, and individualism. These results suggest that even within a single sector, profit orientation influences which working methods and management principles play a dominant role. Several studies have investigated which features of leadership and management have a positive effect on the target system of SEs. Based on two data sets on British and Japanese SEs, Liu, Takeda, and Ko (Citation2014) show that a pronounced entrepreneurial and market orientation is associated with above-average performance on both economic and social targets. The newest study by Bhattarai, Kwong, and Tasavori (Citation2019) confirms this view with data on British SEs, although in this case, it does so with respect to market orientation and the capacity for innovation. On the other hand, Duvnäs et al. (Citation2012) do not find any such correlation for Finnish SEs. However, they point out that this might be explained by the limited degree of freedom of Finnish managers since the activities of SEs are tightly regulated in Finland. An Australian study by Miles et al. (Citation2013) also showed no significant positive influence of an entrepreneurial orientation. The authors explain this result not only by referring to institutional restrictions, but also expressed the suspicion that conflicts around goals might be generated by an increased focus on economic conditions: there is a risk of diverting attention away from the organisation’s purpose towards the pursuit of monetary goals. Another Australian study by Newman et al. (Citation2018) focuses on management relations and shows that a markedly entrepreneurial orientation, on the one hand, increases the staff’s willingness to innovate, but, on the other hand, has no effect on staff retention. Results by Shier, Handy, and Jennings (Citation2019) suggest that strong employee involvement and integration are in themselves important factors for an organisation’s capacity to innovate; in SEs lacking a pronounced profit orientation, a drive towards innovation would thus be more likely to be found at the staff level than among the leadership. The Finnish study by Tykkyläinen et al. (Citation2016) investigating the growth orientation of SEs shows how, on the one hand, a social mission can act as an impulse towards development that furthers growth targets; on the other hand, a strong mission orientation can also impede growth when the latter is perceived as an expression of purely commercial interests. In a recently published study, Alarifi, Robson, and Kromidha (Citation2019) show that in SEs in Saudi Arabia, innovation and proactiveness correlate positively with organisational performance, but there is no such correlation between risk-taking and performance.

gives an overview of the most important measures of performance used in the studies mentioned above. Here it can be noted that (1) the measures of performance are very heterogeneous, (2) the factors contributing to performance turn out to be different depending on which measure of performance is used, and (3) a common feature of all studies is that performance is measured based on subjective assessments. This approach is also used in the present study. To arrive at a meaningful and practically workable selection, we have discussed the economic performance measures (highlighted in in italics) in detail in expert interviews with SE managers (for more information see method chapter).

Table 1. Measuring the performance of SEs.

Method

Sampling and Data Collection

The population of the present study covers 1’198 SEs in Switzerland. Neither an official nor even an approximately comprehensive register of SEs exists in Switzerland. Thus we carried out a separate investigation to determine the population. Using membership directories of relevant associations (such as Arbeitsintegration Schweiz, Insos, Curaviva, Heiminfo, or Cisa Schweiz), we identified the organisations listed through internet searches, and, where possible, obtained out the managing directors’ contact information. Additionally, we searched the internet (using keywords, such as work integration, social venture, social enterprise, social company, social business, or social enterprise) and social media to find additional organisations until no further results were found, respectively data saturation was achieved.

According to the ‘International Typology of Social Enterprise Models’ initiated in the scope of the ICSEM-Project and developed by Defourny and Nyssens (Citation2017), the sample of this study consists mainly of so-called ‘Work Integration Social Enterprises (WISE)’. The main goal of these organisations is to reintegrate disadvantaged groups and long-term unemployed persons into labour market and society. Thus their main focus is on professional and social integration.

Prior to the survey, the study model was discussed intensively with 12 SE-leaders in semi-structured interviews. Questions were for instance: What are your performance goals and measures, how do you try to reach them, and what are you doing to be better than other organisations and potential competitors? In addition, we sent them the questionnaire plus the variables and discussed their practicability. Research on SEs often focuses on the challenge of conceptually understand the social dimension (Dacin, Dacin, and Matear Citation2010) and to measure social impact (see social performance factors in and the review article by Rawhouser, Cummings, and Newbert Citation2019). As discussed in the introduction and clarified in the research question, this is not methodologically addressed here. The answers in the interviews confirmed this strategic research decision. The reasons for this specific focus are the following: (1) In Switzerland, the social mission of SEs is not questioned but is accepted as an important contribution to a functioning welfare regime. (2) However, economic performance and its measurement are increasingly becoming important and required. In other words, the ‘E’ for entrepreneurial is increasingly being demanded, while the ‘WIS’ for social work integration is being seen as legitimate and given (see WISE definition of Defourny and Nyssens Citation2017). (3) The federal structure of Switzerland has led to a heterogeneous social performance measurement system and to equally different measures of social goal attainment. These aspects lead to ambiguities when SEs try to receive cantonal or state funding or when they aim to conclude service contracts with the state. (4) This in turn means that SEs that are not funded often have to take up cases that are more difficult to integrate, which makes them look less successful on a supposedly uniform measurement scale for social performance. (5) This ultimately leads to distorted incentives in the sense of cherry-picking and to competition after cases of integration and rehabilitation with a high probability of ‘success’.

After the interviews and the adaption of the model and the questionnaire, top managers from all the 1’198 organisations in the population were contacted by e-mail and invited to fill out an online survey. Overall, the survey collected 257 evaluable questionnaires. The response rate was 21.5%. Representativeness testing showed that the distribution of size categories in the sample largely reflected that of the population.

The 257 SEs show significant diversity in several aspects: their median yearly revenue is almost 5 million Swiss Francs (around 5.15 million USD), where 18% make <1 million and on the other hand, and 27% make more than 10 million. On average, they employ about 40 staff members (full-time equivalents) and offer places for 60 clients. The average SE in this sample still earns 90% of its income via government service agreements or subsidies. 54% of the organisations derive income from market services, which constitute an average of 20% of the total income; only for 1 in 14 organisations does market income constitute more than half of annual revenue. Finally, half of the organisations also fund themselves via donations from other organisations or individuals, with this constituting only 2–3% of their income on average. When asked about their areas of activity, 67% of the organisations reported managing places of residence and 56% were active in labour market integration.

Three-quarters of the organisations function legally as foundations (39%) or associations (37%); 8% are stock corporations, 5% are limited liability companies, and 3% are cooperatives; the remainder consists above all of the public sector organisations.

When asked about their profit orientation, 34% of the organisations declared that the ‘not-for-profit’ idea is absolutely paramount, while 12% stated otherwise. Using a 10-point scale, 52% of the survey subjects indicated that profitability was either high or very high importance; for another 12% it was the most important factor.

Research Model

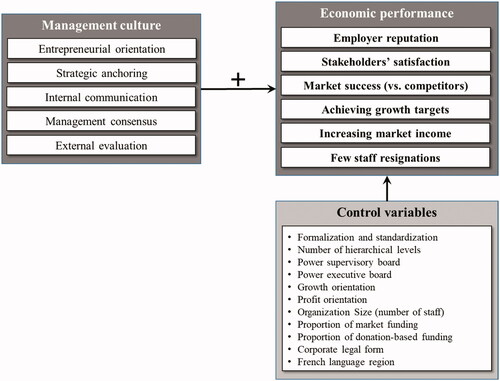

The goal of this study was to identify factors influencing the economic performance of SEs. Thus, this model analyses several aspects of management culture as potential determinants of performance in SEs. These determinants, as well as the multidimensional measure of economic performance, consist of sub-variables that are separately discussed and later tested in the model. For clarity, not every single independent variable is connected to every single dependent variable with an arrow in . Furthermore, not each hypothesis is listed here separately, because the assumptions are all the same and a positive relationship or influence of each independent variable on each dependent variable is assumed. In this respect, the present study is also of an exploratory character. below illustrates the model considerations and relationships.

Economic Performance Measures (Dependent Variables—DV)

The range of performance measures reflects the multidimensional goal system of SEs. For this purpose, we chose six different measures of economic performance. Our starting point was aspects of perceived economic performance commonly used in SEs as well as NPO and general management research (e.g. Barrett, Balloun, and Weinstein Citation2005; Bhuian, Menguc, and Bell Citation2005; Chen and Hsu Citation2013). These had to be, on the one hand, common in scholarly studies (see also literature review section and ) on the other hand, they had to above all appear meaningful in the daily practice of the surveyed SEs (see also explanations to interviews in the method chapter).

The first three dependent variables consisted of self-ratings representing the external perception, respectively field of activity of SEs.

DV1—Reputation as an Employer

This aspect, also labelled employer attractiveness, is highly relevant to attract and retain qualified staff and is seen as a substantial element of organisational performance. It has been analysed and discussed in many studies and contexts (Berthon, Ewing, and Hah Citation2005; Dögl and Holtbrügge Citation2014; Moser, Tumasjan, and Welpe Citation2017). For this reason, we included this variable in our model (Based on a large number of applications, often spontaneous applications, and very positive feedback from employees, I believe that we are an attractive employer with a good reputation).

DV2—Satisfaction of the Stakeholders

SEs must satisfy the expectations of a wide range of stakeholders. These range from beneficiaries to the public, to donors, to name only a few examples. It is therefore not surprising that the literature on SEs provides several studies dealing with this topic (Bissola and Imperatori Citation2012; Crucke and Knockaert Citation2016; Ramus and Vaccaro Citation2017). We included one item with the respondents’ rating in our model (If you were to survey all of your stakeholders, how satisfied would they be overall with your organisation?).

DV3—Market Success Compared to Competitors

While profit-oriented organisations live in competitive situations, concurrence among SEs or towards other organisational types is a recent phenomenon in the literature (Arenas, Hai, and De Bernardi Citation2021; Leung et al. Citation2019; Lyon Citation2012). Therefore, we included it in our model with one variable (How successfully do you rate your company in terms of market success compared to your key competitors?).

DV4—Achieving Growth Targets

This aspect, highly discussed in the management (Ahlstrom Citation2010; Casson Citation2013; Scott and Bruce Citation1987) as well as NPO literature (Eikenberry and Kluver Citation2004) is increasingly discussed in SEs, as growth is a potential measure of performance of their economic mission (Tykkyläinen, Citation2019; Vickers and Lyon Citation2014). The organisations were asked how important growth has been for them in the last 10 years, and how well they have achieved their growth targets (both questions were answered on an unspecified scale from 1 to 10). Organisations that assigned no or only low importance to growth as a goal (values of 3 or less on the 10-point scale) were excluded from the further analysis.

DV5—Increasing Market Income

There is a lively discussion in the literature that SEs also generate revenue via market income (Achleitner, Spiess-Knafl, and Volk Citation2014; Aiken Citation2006; Young and Grinsfelder Citation2011; Zhao and Lounsbury Citation2016). Hence, we asked how the proportion of proceeds from market services had changed over the last 10 years. Organisations were asked whether this proportion had been constant or had (strongly) increased or decreased. From the answer, in combination with the growth criterion, one can deduce how successfully an organisation responds to the market environment.

DV6—Fewer Staff Resignations

We include this last variable as employee turnover is associated with profit in many studies (Ton and Huckman Citation2008; Hancock et al. Citation2013). The managers were asked what percentage of employees had voluntarily left the organisation every year over the past several years. This provides clues as to how well an organisation is meeting its staff-related goals (for example identification and staff retention). summarises the six dependent variables.

Table 2. Dimensions of economic performance.

The participating SEs, respectively their management are not unexpectedly largely positive about their ability to succeed as the subjective measure of the variables promotes social desirability. Despite being very statistically scattered, these data still allow us to draw inferences on the differences between more vs. less successful SEs.

Dimensions of Management Culture (Independent Variables—IV)

We investigated five dimensions of a management culture that on the one hand are well-known in literature and on the other hand, seemed notable in our expert discussions with SE leaders.

IV1—Entrepreneurial Orientation

This variable consists of nine items (Cronbach’s alpha = .74) based on the established scale by Covin and Slevin (Citation1989). The items were slightly adapted to the organisational reality of SEs based on the previous interviews with experts from this sector. They describe whether an organisation launches new products or services (innovativeness), undertakes risky projects and business activities (risk taking), and acts more proactively and quickly than its competitors (proactiveness). These three dimensions are understood as a reflective and one-dimensional construct (Covin and Slevin Citation1989; Helm and Andersson Citation2010; Miller Citation1983). Seen as a reflective construct, entrepreneurial orientation is an attitude shaping the actions of individuals, groups, or whole organisations. In empirical research, correlations serve as an essential indicator as to whether a construct is reflective or formative. When one measures the levels of expression of these three elements in an organisation and their correlation is high, this points to a reflective construct. This is the case here since the elements show significant correlations [Spearman-correlation = p(t) < .01]: innovativeness and risk taking at +.38, innovativeness and proactiveness at +.40, and risk taking and proactiveness at +.37.

IV2—Strategic Anchoring

IV2—strategic anchoring was assessed by three questions, respectively items about how the organisation’s foundational goals are spelled out, broken down into individual sub-goals, and used to motivate staff (Cronbach’s alpha = .72). In other words, we think that the successful implementation of a strategy has a positive impact on the SEs’ performance. This connection has been confirmed in management literature (Ho, Wu, and Wu Citation2014; Hrebiniak Citation2006).

IV3—Internal Communication

IV3—internal communication consists of five items (Cronbach’s alpha = .82) in which we asked how intensive the exchange and feedback on organisational goals and services is, to what degree staff is included in decision making, and in how far informal meetings take place in an established fashion. This battery of items was equally shaped by the previous interviews and conversations about the research model. We took it into our survey as results from the literature have shown that a well-functioning internal communication has a positive effect on the organisations’ performance (Cowan Citation2017; Tourish and Hargie Citation1996; Yates Citation2006).

IV4—Management Consensus

IV4—management consensus comprises three questions in which managing directors assessed how far their values and ideas agreed with those of the supervisory board (respectively board of trustees) and influenced common strategic guidelines, and how strongly they felt supported by the board (Cronbach’s alpha = .80). The cooperation between the operational and strategic levels is an important and heavily discussed area especially in SEs as it can create tensions since the managing directors are full-time employees whereas the supervisory board is mostly composed of voluntary, respectively honorary. Finally, their relationship and the consensus on important strategic decisions are decisive for organisational performance (e.g. Bernstein, Buse, and Bilimoria Citation2016; LeRoux and Langer Citation2016).

IV5—External Evaluation

Furthermore, we asked whether the organisation undergoes an evaluation by an external body at regular intervals. The rationale behind this is that an organisation is more likely to achieve its economic mission if an external body (e.g. auditor, consultancy) audits its operation and performance (Conley-Tyler Citation2005; Luke, Barraket, and Eversole Citation2013). summarises the potential determinants of performance.

Table 3. Hypothesised determinants of economic performance.

Controls (Control Variables—CV)

Organisational structure, as the first set of control variables, was modelled in two dimensions to keep with the research tradition (see for example the foundational article by Pugh et al. Citation1968). Formalisation and standardisation (CV1) comprise five items concerning the formalisation of individual job descriptions, performance reviews, work processes, and the division of labour between operational and strategic leadership (Cronbach’s alpha = .82). Additionally, we measured the number of hierarchical levels (CV2) as an indication of the length of communication paths between the top and the base, and the influence of strategic and operational management as measured by the power of the supervisory board (CV3) and that of the executive board (CV4). The growth orientation (CV5) and profit orientation (CV6) of the organisations was measured using two simple questions. We first asked whether growth and/or profit goals had been set; if so, we asked whether the organisation had achieved them (scales from 1–10: CV5 mean = 5.69, CV6 mean = 6.20). As further control variables, we took into account the organisation size (CV7), measured by the number of staff in full-time equivalents; the proportion of market funding in the organisation’s total income (CV8 and CV9, because we tested the proportions of market and donations funding separately), whether the legal form (CV10) of the organisation was corporate (e.g. joint-stock company or a limited liability company) and thus an exception from the usual SE legal forms like association or foundation, and the language region (CV11), where we regarded German Switzerland as the typical case (92.2%) and French Switzerland (and Italian) as the exception.

Results

with the correlation matrix indicates that the criteria of economic performance show relatively low mutual correlations, mostly between dependent variables 1, 2, and 3 measuring the external perception, respectively field of activity. Some additional correlation can be found between market success and achievement of growth targets, respectively low staff resignations. However, apart from this, no significant correlations were found, especially not with increment in market income and staff resignations. This is why the criteria of performance are tested and accounted for separately in the following regression model. The independent variables correlate quite strongly with each other, which gives some evidence of multicollinearity (Dormann et al. Citation2013). This was to be expected since they all measure management culture (see ).

Table 4. Non-parametric correlations between variables from economic performance, management culture and control variables.

If we look only at the simple correlations (non-parametric Spearman’s rho coefficients) between the six variables of economic performance on the one hand and the hypothesised influencing factors on the other, we can see some evidence for relationships. Entrepreneurial orientation and strategic anchoring both show an almost pervasive positive effect on the performance variables, except on the staff turnover rate, for which the correlation is close to 0. Internal communication presents a similar picture, however, showing a stronger effect on staff turnover and almost none on increased market income. A consensus in the management correlates with the employers’ reputation, the satisfaction of the stakeholders, and the market success. In addition, external evaluation only positively correlates with fewer staff resignations. shows the correlation matrix.

Summarising all economic performance factors into a single regression model that considers their interdependencies largely confirms the results of the correlation analyses, while further emphasising the variables with the strongest correlations. shows the regression model.

Table 5. Regression analyses for the various criteria of economic performance.

Multiple linear regressions were carried out for employer reputation, stakeholders’ satisfaction, market success compared to competitors, achieving growth targets, increasing market income, and few staff resignations. The sample size is reduced because only full datasets were included (list-based exclusion of cases). Since an increase in market income as a dependent variable can be regarded as interval-scaled only in a limited way, we additionally carried out an ordinal regression analysis to test the robustness of this model: with a pseudo-R-squared (Cox and Snell) of 27%, this method yielded the same significant coefficients as did the multiple linear regression.

Thus the following points can be recorded and discussed as core insights of the regression analyses:

An entrepreneurial orientation strengthens the market success compared to competitors and leads to an achievement of the growth targets.

A strategic anchoring operationalised with three aspects about how the organisation’s foundational goals are spelled out, broken down into individual sub-goals, and used to motivate staff leads to an increased market income.

A well-functioning internal communication strengthens the reputation as an employer and the satisfaction of stakeholders. Consequently, it also results in fewer staff resignations (however with a negligible statistical effect).

When the organisation undergoes an evaluation by an external body at regular intervals, the employer's reputation is improved and more staff remains in the organisation. These relationships have to be interpreted as tendencies since the influence on the statistical models is rather low.

Our regression model showed no significant results for the variables management consensus. On the other hand, an interesting relationship could be found for the control variable growth orientation. While growth-oriented organisations do not surprisingly tend to achieve their growth targets, it is interesting to note that they also tend to increase their proportion of market-derived revenues.

Discussion

Based on the results of the regression analysis, managerial implications (MI) can be formulated, which in turn can lead to new and interesting future research questions (FRQ). In addition, our implications are linked to existing findings in the literature.

MI1: Increase Market Success with an Entrepreneurial Orientation

If an SE is exposed to an intensified competitive environment (e.g. for grants, service contracts with the state, «struggle» for promising clients; see also specific context factors for Switzerland in the method chapter), then it is wise to act in an entrepreneurially oriented manner, because this leads to market success compared to competitors. From the perspective of the SEs investigated and their representatives, entrepreneurial orientation is associated with higher market success. SEs which put special emphasis on innovation in their service range and thereby deliberately differentiate themselves from competitors in the way that they act more proactively and quickly than their competitors and occasionally take considerable risks, act in an entrepreneurial way. Similar results were arrived by Barrett, Balloun, and Weinstein (Citation2005), who analysed organisations in the education and health sector in the USA and found that an entrepreneurial orientation correlates positively with subjectively perceived organisational performance. Coombes et al. (Citation2011) showed that, for cultural organisations in the USA, activism among the board of directors is correlated with an entrepreneurial orientation, which in turn correlates with subjective assessments of achieving the organisation’s mission. Alarifi, Robson, and Kromidha (Citation2019) similarly demonstrated a positive correlation between two elements, innovativeness, and proactiveness, with organisational performance for SEs. The authors tested these dimensions separately against performance, and so did not treat entrepreneurial orientation as a one-dimensional, formative construct.

Regarding the relationship between EO and market success, potential additional research questions can be reflected:

FRQ1: Following the approach of Alarifi, Robson, and Kromidha (Citation2019), it might be interesting to understand EO as a formative and multidimensional construct. A formative operationalisation exists if the expression of the construct is causally determined by the manifest individual indicators. The expression of the indicators is thus modelled as the cause of the expression of the construct. In this case, every dimension could be tested individually with market performance.

FRQ2: Another option is to work with the alternative operationalisation of EO by Lumpkin and Dess (Citation1996), who take up those of Covin and Slevin (Citation1989) and add competitive aggressiveness and autonomy as new dimensions. Especially competitive aggressiveness might be a dimension worth investigation as an independent variable since we measured market success in comparison to the SE’s competitors.

FRQ3: This in turn leads to the question of whether the common constructs of Covin and Slevin (Citation1989) or Lumpkin and Dess (Citation1996), originate in the classical management literature and relate to for-profit organisations, are also entirely useful when applied to SEs. The question is whether established scales for EO can be simply transferred to the functional logic of SEs. For example, in a recent qualitative study, Lurtz and Kreutzer (Citation2017) investigated the roles of entrepreneurial orientation in the pre-start-up phase of SEs. They found that risk-taking has both financial and social dimensions and identified collaborations as an additional element of an entrepreneurial orientation. The role of collaborations as an additional source of resources is certainly a point meriting further investigation as an entrepreneurial element in SEs.

MI2: Achieve Growth Targets with an Entrepreneurial Orientation

According to this study, SEs that orient themselves entrepreneurially are also more likely to grow, and those that make growth their objective increase their proportion of market-derived income. Growth-oriented SEs in our sample achieve their goal primarily through increased market revenues. In simple words, if you want to grow, you need an entrepreneurial spirit and money. Moreno and Casillas (Citation2008) state that only a few studies, whether theoretically or empirically analyse the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and growth and try to close this gap by studying a sample of 434 SMEs. This research gap is unfilled, especially for SEs, and the present result provides only initial evidence. A single source in a ‘socially’ mission-driven setting could be found by Pearce, Fritz, and Davis (Citation2010) concerning religious communities in the USA, in which an entrepreneurial orientation is also correlated with organisational growth.

FRQ4: These reflections can point out the understudied relationship between EO and growth in SEs. While the meaningfulness of growth aspirations in SEs (Teasdale, Lyon, and Baldock Citation2013) as well as the influencing factors (Hynes Citation2009) have already been discussed, studies linking EO to growth in the specific context of SEs have been lacking so far.

MI3: Increase Market Income with Strategic Anchoring

If an SE wants to increase market revenue, it should optimise its strategic anchoring in such a way that its foundational goals are spelled out, broken down into individual sub-goals, and used to motivate staff. In other words, the successful implementation of a strategy has a positive impact on the increase of market income. The first idea that arises here is that market income is increased if this goal is also anchored in the strategy, communicated internally and externally, and supported jointly by the strategic and operational management. However, it would be especially for SEs to be possible, that they could increase market income by strategically positioning themselves in a deliberately hybrid (balance between social and economic mission) or primarily social way. This raises a potential new research question:

FRQ5: What is the optimal strategic positioning for SEs in the duality between an economic and social mission to increase market income?

MI4: Increase Employer Attractiveness and Strengthen Stakeholder Satisfaction with a Well-Functioning Internal Communication

Our study was able to show that a well-functioning internal communication increases stakeholder satisfaction and increases the attractiveness of an employer. In addition (however with only a slight statistical effect) a good internal communication has a positive effect on staff resignations. Such a communication culture means (respectively was operationalised) that staff is engaged in intensive exchanges about organisational goals and offered services, can give feedback, is involved in decisions, and, additionally, informal meetings take place in an established fashion. This form of communication seems to radiate beyond the organisational boundaries as it improves the external perception in a 2-fold way (employer reputation and stakeholders’ satisfaction). This aspect is interesting and little researched until today. Studies focus for instance on the effects of external communication on the internal brand perception of employees (Piehler, Schade, and Burmann Citation2019) or the internal communication on employee engagement (Mishra, Boynton, and Mishra Citation2014), but not on the effect of internal communication on potential new employees which are attracted by a positive employer reputation. Other studies focus on the effect of external communication on their stakeholders (Scholes and Clutterbuck Citation1998) but not on the effect of internal communication on their stakeholders. This leads to an additional potential research question:

FRQ6: What is the external impact of positive internal communication in SEs (as well as in other organisational forms)?

With negligible statistical effects but still worth being noted, is that one would like to work in SEs which undergo an externally evaluated from time to time because this might have a positive effect on the attractiveness of the employer. A regular external assessment can be perceived as reflecting critically on its own actions, and that again might motivate employees to stay (resulting in lower staff resignations).

MI5: Chose Wisely Your Performance Measures and the Way You Want to Promote Them

In our preliminary literature review on performance measures in SEs we noted that the measures of performance are not only highly heterogeneous but the contributing factors to performance turn out to be different depending on which performance measure is applied. In a concrete example of our study: Whether EO has an impact on performance depends on how we measure performance. The scientific empiricism of management and organisational research will not be able to fully solve this challenge, as it is not an exact science. However, it is possible to derive recommendations for SE leaders: (1) Chose pragmatic performance measures in relation to your economic (and/or social) mission, (2) Be aware that the same influencing factor can have a positive influence on economic performance, but might have a negative influence on your social mission. Thus, while this study shows that EO has a positive impact on market success and growth targets, it does not show whether EO also has a positive impact on the reintegration of socially disadvantaged groups. The measurement of social goals and performance was deliberately not the subject of this study, yet we feel it is important to include this aspect here and it brings us to an additional possible research question.

FRQ7: Does EO have a positive influence on the achievement of social goals? This aspect has not yet been investigated because EO has been studied primarily in profit-oriented organisations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we state that focussing on economic performance factors in SEs and the social sector does not necessarily make an organisation act as a business enterprise, and neither does it imply that the social mission is being betrayed in favour of one-sided managerialism. Apart from an entrepreneurial orientation, taking care of the internal communication culture and a good anchoring of organisational goals and strategies show a strong correlation with successfully achieving economic goals. SEs can attain this performance in ways that match the values and social image of their work, and this can take place outside oversimplified concepts of commercialisation. We cannot completely dismiss the hidden danger that a pronounced economic focus will lead to alienation from the traditional values of integration work and thus not paying the same attention to social goals (Garrow and Hasenfeld Citation2014). However, this may also depend on point of view and attitude, since SEs that act entrepreneurially and are economically stable have greater chances of survival, and thus also the potential to carry out their social mission for longer and with greater success. Finally, as many SEs experience it every day, it is crucial to find a good balance between a diverse set of goals.

Limitations

The present study measured the economic performance factors primarily in terms of output. No measurement of goal achievement in the sense of outcome and impact was carried out in this study, even though there are already several conceptual contributions on this subject (e.g. Arena, Azzone, and Bengo Citation2015; Arogyaswamy Citation2017; Bagnoli and Megali Citation2011). Thus, a future study could aim to include this extensive type of performance measure as dependent variables in a quantitative study design, as was done by Battilana et al. (Citation2015). In this context, a survey among service recipients, respectively clients would also be meaningful and could represent an interesting extension of the research beyond surveying only managers. A fundamental issue that merits critical scrutiny is that a survey of SE leaders asks for subjective assessments but does so from only one perspective; however, the managers’ perspective is not necessarily identical to that of the staff. A further issue is the self-selection bias, which is hard to control in organisational research and can give rise to distortions of representativeness. However, it is a state of the art as shown in with the performance measurement scales. The self-selection bias also means that the SE leaders do not give neutral answers and probably rate their own organisation more positively than average.

Regarding the measurement of entrepreneurial orientation three aspects should be viewed critically (as discussed as future research questions in the discussion chapter): It might be interesting to understand EO as a formative and multidimensional construct, it might be clever to work with the five-dimensional operationalisation of EO, including competitive aggressiveness and autonomy as new dimensions, and it should be reconsidered whether the established EO scales require adaptation to the SE logic.

An additional limitation we note is that this study has been conducted in the specific context of only one country and with manageable sample size. However, Switzerland is a federal system in which institutional influences are predominantly determined by the local cantons and environmental conditions are rather diverse. This makes a one-sided distortion rather unlikely.

Another critical point is that this study is probably primarily representative of countries where SEs are still heavily dependent on the state for social integration, as can be seen in the funding mix of the sample. Switzerland, although historically liberal, has increasingly become a welfare regime. SEs and especially work integration SEs with their social mission is seen as an integral and important part of a functioning society. However, economic success and evidence of performance are increasingly required. This motivated us to provide answers to the much-discussed question in science, business, and politics: ‘Which aspects of management culture lead to economic performance of SEs?’.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Achleitner, A. K., W. Spiess-Knafl, and S. Volk. 2014. “The Financing Structure of Social Enterprises: Conflicts and Implications.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing 6 (1): 85–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEV.2014.059404.

- Ahlstrom, D. 2010. “Innovation and Growth: How Business Contributes to Society.” Academy of Management Perspectives 24 (3): 11–24.

- Aiken, M. 2006. “Towards Market or State? Tensions and Opportunities in the Evolutionary Path of Three UK Social Enterprises.” In M. Nyssens (Ed.), Social Enterprise: At the Crossroads of Market, Public Policies and Civil Society (pp. 259–271). Routledge.

- Alarifi, G., P. Robson, and E. Kromidha. 2019. “The Manifestation of Entrepreneurial Orientation in the Social Entrepreneurship Context.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 10 (3): 307–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1541015.

- Alegre, I. 2015. “Social and Economic Tension in Social Enterprises: Does It Exist?” Social Business 5 (1): 17–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1362/204440815X14267607784767.

- Arena, M., G. Azzone, and I. Bengo. 2015. “Performance Measurement for Social Enterprises.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 26 (2): 649–672. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9436-8.

- Arenas, D., S. Hai, and C. De Bernardi. 2021. “Coopetition Among Social Enterprises: A Three-Level Dynamic Motivated by Social and Economic Goals.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 50 (1): 165–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020948615.

- Arogyaswamy, B. 2017. “Social Entrepreneurship Performance Measurement: A Time-Based Organizing Framework.” Business Horizons 60 (5): 603–611. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2017.05.004.

- Bagnoli, L., and C. Megali. 2011. “Measuring Performance in Social Enterprises.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 40 (1): 149–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764009351111.

- Balabanis, G., R. E. Stables, and H. C. Phillips. 1997. “Market Orientation in the Top 200 British Charity Organizations and Its Impact on Their Performance.” European Journal of Marketing 31 (8): 583–603. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569710176592.

- Barrett, H., J. L. Balloun, and A. Weinstein. 2005. “The Impact of Creativity on Performance in Non‐profits.” International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 10 (4): 213–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.25.

- Battilana, J., M. Sengul, A. C. Pache, and J. Model. 2015. “Harnessing Productive Tensions in Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Work Integration Social Enterprises.” Academy of Management Journal 58 (6): 1658–1685. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0903.

- Bernstein, R., K. Buse, and D. Bilimoria. 2016. “Revisiting Agency and Stewardship Theories: Perspectives from Nonprofit Board Chairs and CEOs.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 26 (4): 489–498. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21199.

- Berthon, P., M. Ewing, and L. L. Hah. 2005. “Captivating Company: Dimensions of Attractiveness in Employer Branding.” International Journal of Advertising 24 (2): 151–172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2005.11072912.

- Bhattarai, C. R., C. C. Kwong, and M. Tasavori. 2019. “Market Orientation, Market Disruptiveness Capability and Social Enterprise Performance: An Empirical Study from the United Kingdom.” Journal of Business Research 96: 47–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.042.

- Bhuian, S. N., B. Menguc, and S. J. Bell. 2005. “Just Entrepreneurial Enough: The Moderating Effect of Entrepreneurship on the Relationship between Market Orientation and Performance.” Journal of Business Research 58 (1): 9–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(03)00074-2.

- Bissola, R, and B. Imperatori. 2012. “Sustaining the Stakeholder Engagement in the Social Enterprise: The Human Resource Architecture.” In Patterns in Social Entrepreneurship Research. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bull, M., and H. Crompton. 2006. “Business Practices in Social Enterprises.” Social Enterprise Journal 2 (1): 42–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/17508610680000712.

- Casson, M., ed. 2013. The Growth of International Business (RLE International Business). Routledge.

- Chen, H. L., and C. H. Hsu. 2013. “Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance in Non-profit Service Organizations: Contingent Effect of Market Orientation.” The Service Industries Journal 33 (5): 445–466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2011.622372.

- Child, C. 2016. “Tip of the Iceberg: The Nonprofit Underpinnings of For-Profit Social Enterprise.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45 (2): 217–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764015572901.

- Conley-Tyler, M. 2005. “A Fundamental Choice: Internal or External Evaluation?” Evaluation Journal of Australasia 4 (1–2): 3–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1035719X05004001-202.

- Coombes, S. M., M. H. Morris, J. A. Allen, and J. W. Webb. 2011. “Behavioural Orientations of Non‐profit Boards as a Factor in Entrepreneurial Performance: Does Governance Matter?” Journal of Management Studies 48 (4): 829–856. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00956.x.

- Covin, J. G., and D. P. Slevin. 1989. “Strategic Management of Small Firms in Hostile and Benign Environments.” Strategic Management Journal 10 (1): 75–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100107.

- Cowan, D. 2017. Strategic Internal Communication: How to Build Employee Engagement and Performance. Kogan Page Publishers.

- Crucke, S., and M. Knockaert. 2016. “When Stakeholder Representation Leads to faultlines. A study of Board Service Performance in Social Enterprises.” Journal of Management Studies 53 (5): 768–793. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12197.

- Dacin, P. A., M. T. Dacin, and M. Matear. 2010. “Social Entrepreneurship: Why We Don't Need a New Theory and How We Move Forward from Here.” Academy of Management Perspectives 24 (3): 37–57.

- Dart, R. 2004. “The Legitimacy of Social Enterprise.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 14 (4): 411–424. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.43.

- Dees, J. G. 1998. “Enterprising Nonprofits.” Harvard Business Review 76 (1): 54–67. Accessed January 4, 2020. https://hbr.org/1998/01/enterprising-nonprofits

- Defourny, J., and M. Nyssens. 2017. “Fundamentals for an international typology of social enterprise models.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 28 (6): 2469–2497. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9884-7.

- Di Zhang, D., and L. A. Swanson. 2013. “Social Entrepreneurship in Nonprofit Organizations: An Empirical Investigation of the Synergy between Social and Business Objectives.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 25 (1): 105–125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2013.759822.

- Dögl, C., and D. Holtbrügge. 2014. “Corporate Environmental Responsibility, Employer Reputation and Employee Commitment: An Empirical Study in Developed and Emerging Economies.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25 (12): 1739–1762. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.859164.

- Dormann, Carsten F., Jane Elith, Sven Bacher, Carsten Buchmann, Gudrun Carl, Gabriel Carré, Jaime R. García Marquéz, et al. 2013. “Collinearity: A Review of Methods to Deal with it and a Simulation Study Evaluating their Performance.” Ecography 36 (1): 27–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2012.07348.x.

- Duvnäs, H., P. Stenholm, M. Brännback, and A. L. Carsrud. 2012. “What Are the Outcomes of Innovativeness within Social Entrepreneurship? The Relationship between Innovative Orientation and Social Enterprise Economic Performance.” Journal of Strategic Innovation and Sustainability 8 (1): 68–80.

- Eikenberry, A. M., and J. D. Kluver. 2004. “The Marketization of the Nonprofit Sector: Civil Society at Risk?” Public Administration Review 64 (2): 132–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00355.x.

- Erpf, P., T. A. Bryer, and E. Butkevičienė. 2019. “A Context-Responsiveness Framework for the Relationship between Government and Social Entrepreneurship: Exploring the Cases of United States, Switzerland, and Lithuania.” Public Performance & Management Review 42 (5): 1211–1229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1568885.

- Erpf, P., M. J. Ripper, and M. Castignetti. 2019. “Understanding Social Entrepreneurship Based on Self-Evaluations of Organizational Leaders–Insights from an International Survey.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 10 (3): 288–306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1541014.

- Fitzgerald, T., and D. Shepherd. 2018. “Emerging Structures for Social Enterprises within Nonprofits: An Institutional Logics Perspective.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 47 (3): 474–492. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764018757024.

- Garrow, E. E., and Y. Hasenfeld. 2014. “Social Enterprises as an Embodiment of a Neoliberal Welfare Logic.” American Behavioral Scientist 58 (11): 1475–1493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214534674.

- Gupta, P., S. Chauhan, J. Paul, and M. P. Jaiswal. 2020. “Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Review and Future Research Agenda.” Journal of Business Research 113 (2020): 209–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.032.

- Hancock, J. I., D. G. Allen, F. A. Bosco, K. R. McDaniel, and C. A. Pierce. 2013. “Meta-Analytic Review of Employee Turnover as a Predictor of Firm Performance.” Journal of Management 39 (3): 573–603. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311424943.

- Haugh, H. 2007. “Community–Led Social Venture Creation.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 31 (2): 161–182. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00168.x.

- Helm, S. T., and F. O. Andersson. 2010. “Beyond Taxonomy: An Empirical Validation of Social Entrepreneurship in the Nonprofit Sector.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 20 (3): 259–276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.253.

- Ho, J. L., A. Wu, and S. Y. Wu. 2014. “Performance Measures, Consensus on Strategy Implementation, and Performance: Evidence from the Operational-Level of Organizations.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 39 (1): 38–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2013.11.003.

- Hrebiniak, L. G. 2006. “Obstacles to Effective Strategy Implementation.” Organizational Dynamics 35 (1): 12–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2005.12.001.

- Hynes, B. 2009. “Growing the Social Enterprise–Issues and Challenges.” Social Enterprise Journal 5 (2): 114–125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/17508610910981707.

- LeRoux, K. M. 2005. “What Drives Nonprofit Entrepreneurship? A Look at Budget Trends of Metro Detroit Social Service Agencies.” The American Review of Public Administration 35 (4): 350–362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074005278813.

- LeRoux, K., and J. Langer. 2016. “What Nonprofit Executives Want and What They Get from Board Members.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 27 (2): 147–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21234.

- Leung, S., P. Mo, H. Ling, Y. Chandra, and S. S. Ho. 2019. “Enhancing the Competitiveness and Sustainability of Social Enterprises in Hong Kong: A Three-Dimensional Analysis.” China Journal of Accounting Research 12 (2): 157–176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjar.2019.03.002.

- Liu, G., S. Takeda, and W. W. Ko. 2014. “Strategic Orientation and Social Enterprise Performance.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 43 (3): 480–501. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764012468629.

- Lu, J., and J. Park. 2018. “Bureaucratization, Professionalization, and Advocacy Engagement in Nonprofit Human Service Organizations.” Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance 42 (4): 380–395.

- Luke, B., J. Barraket, and R. Eversole. 2013. “Measurement as Legitimacy versus Legitimacy of Measures: Performance Evaluation of Social Enterprise.” Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management 10 (3/4): 234–258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/QRAM-08-2012-0034.

- Lumpkin, G. T., and G. G. Dess. 1996. “Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking It to Performance.” The Academy of Management Review 21 (1): 135–172. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/258632.

- Lurtz, K., and K. Kreutzer. 2017. “Entrepreneurial Orientation and Social Venture Creation in Nonprofit Organizations: The Pivotal Role of Social Risk Taking and Collaboration.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 46 (1): 92–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764016654221.

- Lyon, F. 2012. “Social Innovation, Co-operation, and Competition: Inter-Organizational Relations for Social Enterprises in the Delivery of Public Services.” In Social Innovation, 139–161. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Meyer, J. P., N. J. Allen, and C. A. Smith. 1993. “Commitment to Organizations and Occupations: Extension and Test of a Three-Component Conceptualization.” Journal of Applied Psychology 78 (4): 538–551. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538.

- Miles, M., M. L. Verreynne, B. Luke, R. Eversole, and J. Barracket. 2013. “The Relationship of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Vincentian Values and Economic and Social Performance in Social Enterprise.” Review of Business 33 (2): 91–102.

- Miller, D. 1983. “The Correlates of Entrepreneurship in Three Types of Firms.” Management Science 29 (7): 770–791. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.7.770.

- Miller-Stevens, K., J. A. Taylor, J. C. Morris, and S. E. Lanivich. 2018. “Assessing Value Differences Between Leaders of Two Social Venture Types: Benefit Corporations and Nonprofit Organizations.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 29 (5): 938–950. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9947-9.

- Mishra, K., L. Boynton, and A. Mishra. 2014. “Driving Employee Engagement: The Expanded Role of Internal Communications.” International Journal of Business Communication 51 (2): 183–202. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488414525399.

- Moreno, A. M., and J. C. Casillas. 2008. “Entrepreneurial Orientation and Growth of SMEs: A Causal Model.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 32 (3): 507–528. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00238.x.

- Moser, K. J., A. Tumasjan, and I. M. Welpe. 2017. “Small but Attractive: Dimensions of New Venture Employer Attractiveness and the Moderating Role of Applicants' Entrepreneurial Behaviors.” Journal of Business Venturing 32 (5): 588–610. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.05.001.

- Newman, A., C. Neesham, G. Manville, and H. H. Tse. 2018. “Examining the Influence of Servant and Entrepreneurial Leadership on the Work Outcomes of Employees in Social Enterprises.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 29 (20): 2905–2926. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1359792.

- Pearce, J. A., D. A. Fritz, and P. S. Davis. 2010. “Entrepreneurial Orientation and the Performance of Religious Congregations as Predicted by Rational Choice Theory.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34 (1): 219–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00315.x.

- Piehler, R., M. Schade, and C. Burmann. 2019. “Employees as a Second Audience: The Effect of External Communication on Internal Brand Management Outcomes.” Journal of Brand Management 26 (4): 445–460. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0135-z.

- Pugh, D. S., D. J. Hickson, C. R. Hinings, and C. Turner. 1968. “Dimensions of Organization Structure.” Administrative Science Quarterly 13 (1): 65–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2391262.

- Ramus, T., and A. Vaccaro. 2017. “Stakeholders Matter: How Social Enterprises Address Mission Drift.” Journal of Business Ethics 143 (2): 307–322. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2353-y.

- Rawhouser, H., M. Cummings, and S. L. Newbert. 2019. “Social Impact Measurement: Current Approaches and Future Directions for Social Entrepreneurship Research.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 43 (1): 82–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258717727718.

- Sassmannshausen, S. P., and C. Volkmann. 2018. “The Scientometrics of Social Entrepreneurship and Its Establishment as an Academic Field.” Journal of Small Business Management 56 (2): 251–273. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12254.

- Scholes, E., and D. Clutterbuck. 1998. “Communication with Stakeholders: An Integrated Approach.” Long Range Planning 31 (2): 227–238. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(98)00007-7.

- Scott, S. G., and R. A. Bruce. 1994. “Determinants of Innovative Behavior: A Path Model of Individual Innovation in the Workplace.” Academy of Management Journal 37 (3): 580–607. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/256701.

- Scott, M., and R. Bruce. 1987. “Five Stages of Growth in Small Business.” Long Range Planning 20 (3): 45–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(87)90071-9.

- Shier, M. L., and F. Handy. 2015. “From Advocacy to Social Innovation: A Typology of Social Change Efforts by Nonprofits.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 26 (6): 2581–2603. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9535-1.

- Shier, M. L., F. Handy, and C. Jennings. 2019. “Intraorganizational Conditions Supporting Social Innovations by Human Service Nonprofits.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 48 (1): 173–193. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764018797477.

- Short, J. C., T. W. Moss, and G. T. Lumpkin. 2009. “Research in Social Entrepreneurship: Past Contributions and Future Opportunities.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 3 (2): 161–194. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.69.

- Smith, B. R., J. Knapp, T. F. Barr, C. E. Stevens, and B. L. Cannatelli. 2010. “Social Enterprises and the Timing of Conception: Organizational Identity Tension, Management, and Marketing.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 22 (2): 108–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10495141003676437.

- Stevens, R., N. Moray, and J. Bruneel. 2015. “The Social and Economic Mission of Social Enterprises: Dimensions, Measurement, Validation, and Relation.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 39 (5): 1051–1082. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12091.

- Suykens, B., F. De Rynck, and B. Verschuere. 2019. “Nonprofit Organizations in between the Nonprofit and Market Spheres: Shifting Goals, Governance and Management?” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 29 (4): 623–636. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21347.

- Teasdale, S., F. Lyon, and R. Baldock. 2013. “Playing with Numbers: A Methodological Critique of the Social Enterprise Growth Myth.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 4 (2): 113–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2012.762800.

- Ton, Z., and R. S. Huckman. 2008. “Managing the Impact of Employee Turnover on Performance: The Role of Process Conformance.” Organization Science 19 (1): 56–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0294.

- Tourish, D., and C. Hargie. 1996. “Internal Communication: Key Steps in Evaluating and Improving Performance.” Corporate Communications: An International Journal 1 (3): 11–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/eb059593.

- Tykkyläinen, S., P. Syrjä, K. Puumalainen, and H. Sjögrén. 2016. “Growth Orientation in Social Enterprises.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing 8 (3): 296–316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEV.2016.078966.

- Tykkyläinen, S. 2019. “Why Social Enterprises Pursue Growth? Analysis of Threats and Opportunities.” Social Enterprise Journal 15 (3): 376–396. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-04-2018-0033.

- Vickers, I., and F. Lyon. 2014. “Beyond Green Niches? Growth Strategies of Environmentally-Motivated Social Enterprises.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 32 (4): 449–470. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242612457700.

- Voss, G. B., and Z. G. Voss 2000. “Strategic orientation and firm performance in an artistic environment.” Journal of Marketing 64 (1): 67–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764012468629.

- Weerawardena, J., and G. S. Mort. 2006. “Investigating Social Entrepreneurship: A Multidimensional Model.” Journal of World Business 41 (1): 21–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2005.09.001.

- Yates, K. 2006. “Internal Communication Effectiveness Enhances Bottom‐Line Results.” Journal of Organizational Excellence 25 (3): 71–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.20102.

- Young, D. R., and M. C. Grinsfelder. 2011. “Social Entrepreneurship and the Financing of Third Sector Organizations.” Journal of Public Affairs Education 17 (4): 543–567. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2011.12001661.

- Zhao, E. Y., and M. Lounsbury. 2016. “An Institutional Logics Approach to Social Entrepreneurship: Market Logic, Religious Diversity, and Resource Acquisition by Microfinance Organizations.” Journal of Business Venturing 31 (6): 643–662. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.09.001.