ABSTRACT

Contemporary research has highlighted the steady rise of individuals becoming radicalised via exposure to extremist discussion on the internet, with the ease of communication with other users that the internet provides playing a major role in the radicalisation process of these individuals. The aim of the present systematic review was to explore recent research into the utilisation of language in extremist cyberspaces and how it may influence the radicalisation process. The findings suggest that there are five prominent linguistical behaviours adopted by extremists online: Algorithmic, Conflict, Hate, Positive, and Recruitment. The results demonstrate that the main purpose of extremist language online is to shape the perceptions of users to see their associated group in positive regard, while simultaneously negatively framing outgroup opposition. This is then followed by encouraging conflict against the promoted ideologies’ perceived enemies. Limitations, future research, and implications are discussed in detail.

The constant threat of violent acts of extremism being committed by terrorist organisations, not only compromises the security and safety of innocent lives daily (Kruglanski et al., Citation2014), but is more prevalent than mainstream media claim (Patrick, Citation2014). Research exploring this threat, has highlighted the growing emergence of individuals becoming radicalised and adopting extremist ideologies (Neumann, Citation2008), with radicalisation becoming a key focal point for policymakers to consider when applying counter terrorism interventions (Kundnani, Citation2012). Radicalisation, as explained by Doosje et al. (Citation2016), is the process of an individual adopting extreme ideologist beliefs as their own and identifying as a member of the groups that hold these views. This gradual process of an individual becoming radicalised, eventually encourages and motivates the individual to resort to means of violence and action to gain the societal and political changes their newfound ideology aims for (Vergani et al., Citation2020).

The step between owning a radical opinion and carrying out radical action is varied and dependent on the personality of the individual (McCauley & Moskalenko, Citation2017). The action taken by the radicalised individual also depends on the depth of their internalisation with the ideology they have adopted, with less enthuastic individuals being less likely to engage in acts of violence and terror (McCauley & Moskalenko, Citation2014). However, with the number of individuals becoming radicalised and adopting extremist ideologies steadily increasing, and the consequences of individuals becoming radicalised potentially involving violent action (Vergani et al., Citation2020), there is an urgent need for research to not only explore how to prevent this process but to try to gain a further understanding as to why this process occurs and why it is increasing in prevalence.

One potential explanation for this consistent increase in radicalisation, may be the equally growing prevalence of the internet in our everyday lives (Conway, Citation2017). It has been suggested that the internet has not only caused an increase in the number of individuals becoming radicalised by extremist ideologies but has also become a fundamental role in the radicalisation process overall (Bastug et al., Citation2020). This is claimed to be due to the broad availability of extremist content and propaganda on the internet (Benson, Citation2014), which not only allows easy access to further content for interested individuals but can potentially encapsulate exposed individuals into a ‘radicalisation incubator’ (Breidlid, Citation2021). This term ‘radicalisation incubator’ (Breidlid, Citation2021) is used to describe the extremist echo chamber that individuals exploring radical content can find themselves trapped in (Odag et al., Citation2019), where they are consistently exposed to extremist content (Gattinara et al., Citation2018).

Research exploring this indicates that a key fundamental factor involved in the process of radicalisation and how propaganda is received and presented, is the language used in the online activities and communication between extremist recruiters, enthusiasts, and interested individuals. It is also theorised that the language used by extremist recruiters and the discourse involved in the promotion of propaganda online, can have a massively influential effect on whether that individual engages with and eventually becomes radicalised to that extremist ideology (Baugut & Neumann, Citation2020), highlighting the potential importance of language in the online radicalisation process.

Focusing on this claim that language is a vital component of online radicalisation, previous research has highlighted the ambiguity surrounding linguistic cues and language patterns that have been claimed to promote radicalisation (Koehler, Citation2015). There is also evidence to suggest that the language typology for female radicalisation may differ from the radicalisation language of male extremists (Windsor, Citation2020), demonstrating further the lack of general language patterns of radicalisation. This issue was discussed further by Scrivens et al. (Citation2018) who claimed that current research exploring online extremist language has not been able to identify clear and definitive characteristics of radical extremists, with a wide range of online behaviours that extremist radicals could exhibit. This suggests that further understanding of how language is used online and how it effects the radicalisation process could provide vital advancements to current online counterterrorism efforts (Abbasi & Chen, Citation2005).

Although the link between radical opinion and radical action is relatively small, with radicalisation on the rise due to the influence of the internet, there is the real possibility that these two elements will become more prevalent simultaneously. This could result in the prevalence of radical action increasing, which has the potential to have devastating consequences on the safety of security officials and members of the public in general. This highlights the need for further exploration of the effect language has during the radicalisation process, potentially investigating any patterns in research findings that may have been overlooked or not seen as an important factor when identified in singular research only.

The current systematic review serves the aforementioned purpose, and attempts to address questions regarding uncertain and varied phenomena, with the aim to provide informative results for future research and decision-making (Munn et al., Citation2018). It is also the most appropriate form of review to undertake when exploring a broad range of vague key terms and factors (Christmann, Citation2012).

Aim of the review

This systematic review aims to examine and compare academic research that explored the linguistic behaviours involved in the facilitation of online radicalisation, focusing on research that has identified key fundamental factors in online discourse that encourage the radicalisation process in individuals. Furthermore, by reviewing numerous studies exploring radicalisation language, this review aims to identify key overarching findings and language characteristics involved in the process and facilitation of online radicalisation; and clarify how language is used in the cyberspace for extremist and terrorist recruitment (Koehler, Citation2015).

Method

Search strategy

All articles selected for this systematic review were sourced from academic search engines, including but not limited to: Science Direct, PsychInfo and SpringerLink, and for a more broad and extensive search effort, general research search engines such as Scopus and Google scholar were also utilised. To identify appropriate and relevant articles, all searches involved a varied combination of certain keywords. These keywords were: Cyberspace, Discourse, Extremism, Internet, Language, Online, Propaganda, Radicalisation, Self-Radicalisation, Terrorism.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To identify relevant studies, the abstracts were inspected for information related to the effect of language on online radicalisation. The inclusion criteria are presented below:

The studies had to explore and investigate the language/discourse/words exposed to individuals experiencing online radicalisation.

And/or, studies had to explore discussions focussed on extremist topics via the internet, focusing on the language of these discussions.

All studies had to have been peer-reviewed.

All articles had to be written in the English language.

Studies were not focused on radicalisation via physical interaction.

Studies had to examine or outline the specific words that appear most frequently amongst the radicalisation language.

Extraction of data and analysis

The relevant information for this review from the collected sources was extracted into a summary table (Appendix). The relevant information presented in the table consisted of: The author of the publication, the year of publication, the population of the sample, the measures utilised and the findings of the study. As for analysis, the studies selected were diverse in character and content, mostly consisting of qualitative methods and detailed results. Therefore, due to the heterogeneity of the selected literature, the results will be presented as a narrative.

Results

The initial literature search produced a literature pool consisting of 107 independent research articles, mostly acquired through the search engine google scholar and all published in a wide range of research articles based in various disciplines such as psychology, sociology, and criminology. After this initial search, a full-text review was conducted, resulting in a final sample size of 16 being selected for this review. Of the articles that were excluded, they were mainly omitted from the final sample due to either not fulfilling the inclusion criteria of focusing their research on the language involved with online radicalisation or did not provide an analysis or discussion on the specific words that are involved in online radicalisation language.

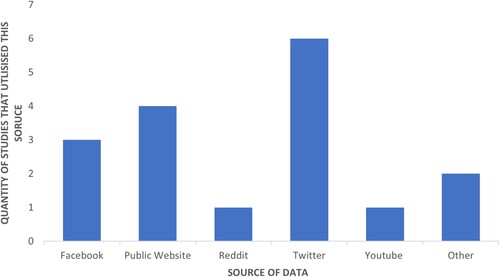

16 separate research studies were explored, all focused on how language is utilised on the internet by extremists, and how this influences the radicalisation process. A summary of the selected research and their characteristics is showcased in the Appendix. The studies utilised different data sources, with the social media site Twitter being the most predominately used source to acquire a data sample out of the selected studies (). Regarding this, displays a higher value than the total number of studies included in this current review, due to some of the selected research studies utilising data from multiple different sources, such as Awan (Citation2017) who examined data from both Facebook and Twitter. Data extracted that were labelled as ‘other’, included studies that used offline methods of acquiring information about online extremist use (e.g. Interviews with former extremists: Koehler, Citation2015).

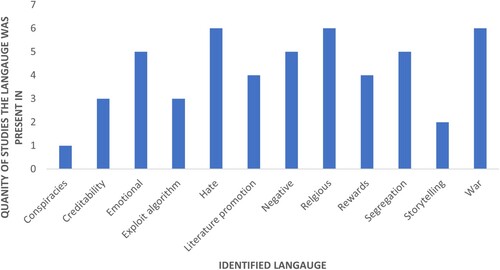

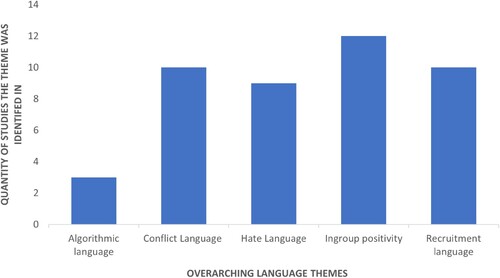

Out of the 16 studies selected for this systematic review, 12 overarching behaviours were identified (), with the findings on each of these linguistic behaviours being grouped into five main themes.

These five main themes are: Recruitment language, Algorithmic language, Ingroup positivity, Hate language, and Conflict language ().

Recruitment language

Most of the literature included in this study found that online extremist recruiters will seek out vulnerable and interested individuals, to openly discuss and influence their ideological opinion, with the aim of encouraging the individual to undergo the radicalisation process and become a follower of the recruiter’s extremist group. These recruitment methods were found to be utilising, at minimum, one of the following four overarching linguistical techniques identified in this review: Literature promotion, Emotional language, Conspiracy language, and Storytelling language.

Literature promotion

Caiani and Parenti in Citation2009 found that 56.3% of the right-wing websites they examined contained a forum feature, which allowed members to discuss ideological policy together and encouraged new members to engage in their discussion. They also found that 52.2% of these sites contained multimedia content and ideological literature, with extremist ‘preachers’ encouraging followers to engage with the bibliographical references they were promoting on their site.

Similarly, Baugut and Neumann’s (Citation2020) identified that followers were advised to read the ideological literature to solve their own real-life personal problems. These famous works of literature on the ideology were often quoted and utilised in the language of the preachers when posting to larger audiences. Prior to that, Gerstendfeld et al. (Citation2003) had found that 31.8% of the tweets in his sample contained quotations from renowned white supremacist literacy works (e.g. Mein Kampf). Whereas, Klausen (Citation2015) identified that literature promotion was one of the most prevalent forms of twitter language by Jihadi preachers on Twitter (38.5%).

Emotional language

Emotional language in the form of battlefield commentary was the most prevalent form of language used by online ‘preachers’ (Klausen, Citation2015; 40.3% of sample). Likewise, Awan (Citation2017) revealed how preachers used the horrors and raw emotions of the battlefield online to recruit new followers, with emotion-provoking terms such as ‘Battlefield’, ‘Killing’, and ‘Slaughter’ being in the top 20 keywords identified. This emotion was also identified by Badawy and Ferrara (Citation2018), who showcased how tweets from identified ISIS followers used language that evoked sympathy and anger in their posts (e.g. I want to see them punished for their crimes against Muslims) when describing the battlefield. Similarly, Scrivens (Citation2021), highlighted how users utilised emotional language and formatting tone to promote violence and hatred towards their perceived oppressors and garner sympathy from viewers of the post. This was further explored by Bouko et al. (Citation2021), who showed evidence of this use of sympathetic language, with preachers in their sample using colloquial and intense metaphors to present their apparent emotional turmoil and distress (e.g. Rivers of blood flow abundantly from the veins of our brothers and sisters in the Muslim world). Moreover, Bouko et al. (Citation2021) stated that these metaphors were a fundamental element of an extremist recruiter’s lexicon and language, being used frequently when talking about the ideology or the perceived threat of the enemy on the battlefield.

Conspiracy language

There was only one study that identified and discussed the use of conspiracy language, but its presence being minimal in this review does not mean that the language theme is rare or uncommon in the extremist cyberspace, just that the selected literature and the samples they included did not contain or identify the language. The present review selected a study that identified this language, and to gain a further understanding as to the language behaviours that are involved in extremist cyberspaces, all languages must be included, regardless of prevalence in the overall literature. Looking at this language behaviour, Riebe et al. (Citation2018) highlighted how the promotion of fake news and use of conspirator language was the fourth most prevalent form of language in their sample of extreme right-wing Facebook posts, with these posts involving high emotional language to display credibility in their claims. Riebe et al. (Citation2018) informed that fake news claims largely increased during political elections and events, reaching a peak of 41% of all the languages included in the sample during the 2016 German elections. These claims were often used to discredit the opposition and portray the candidates negatively.

Storytelling language

Klausen (Citation2015) found that Jihadi preachers on Twitter often used the photographs and videos from the warzone as a storytelling tool (3.4% of sample). This linguistical behaviour of storytelling predominantly involved a narrative of a desperate fight against oppression with visual aids and intense imagery, told using storytelling language that used a narrative format when promoting the message of the group. Bouko et al. (Citation2021) found that these stories promoted by extremists online were often expressed in large posts consisting of between 305 and 1030 words each, which mostly involved the author telling other users their narrative of warzone events and urging sympathises to join their group.

Algorithmic language

Although most of the research samples in this review consisted of individuals who actively searched for and interacted with extremist sites for their own interest and desire, there were instances in some of the literature where it wasn’t the language used by extremists that directly influenced radicalisation, but the language-based search algorithmics of the internet. It was also highlighted in three of the selected studies that extremists are aware of this language-based search function and utilise it to their advantage.

Search suggestions

Some of the interviewees from Baugut and Neumann (Citation2020) claimed that before they were approached by online extremist preachers, they were first exposed to extremist content through the suggestion algorithms of the internet. One of their interviewees claimed that they never explored the internet for an extremist ideology, and that they were just searching for terms such as ‘Islam’ and ‘Preacher’ but were then exposed to a variety of radical content, despite their original search intention. The interviewee claimed that it was this echo chamber of being exposed to numerous extremist material, that began their ideological transformation and radicalisation.

Exploitation of search algorithms

Benigni et al. (Citation2017) highlighted how extremist recruiters exploit these language-based search algorithms, finding that the ISIS preachers and promoters in their sample used the ‘hashtag’ function on Twitter to link their battlefield exploits and increase the volume of online traffic to their battlefield commentary posts. Looking at all the hashtags utilised by ISIS recruiters in Benigni et al. (Citation2017), 75,382 tweets out of the 119,156 tweets sample (63.3%), included a hashtag and content about the group’s ideology, often promoting a discussion about the group’s offline exploits. Awan (Citation2017) also found this linguistical behaviour of recruiters manipulating the search algorithm, highlighting how recruiters used hashtags as a means of quickly spreading a message to numerous followers and users, with assistance from the sites built-in ability to share posts, such as Twitter’s retweet function. This manipulation of search algorithms was one of the most prominent tools of propaganda, highlighting its importance in the process of individuals becoming radicalised via the internet.

Ingroup positivity

A common linguistic behaviour that occurred in the included literature, was the glorification of the group’s extremist action and the positive descriptions they communicated about their chosen ideological cause. Positively framing the ideology not only serves the purpose of encouraging others to join the group but having numerous users praising the groups’ lifestyle and actions increases the credibility of the ideology to an unaware user. This theme was presented using three different language techniques: discussion of the rewards and benefits you’ll receive for joining the group, building the credibility of the group, and discussion involving religious terminology.

Benefits and rewards

Bouko et al. (Citation2021) found in their Facebook sample that extremist groups will use linguistical techniques, such as metaphors, to promote the alleged benefits received by the groups’ ingroups’ members, with a large amount of the language used in the sample containing positive framing language about the inspirational figures of the group’s ideology. This often-involved discussion and language about the benefits and rewards these ideological figures gained, and how the user can gain these too, by becoming a member of the group. This was also seen in Windsor (Citation2020); a case study of extremist recruiter Asqa Mahmood, showcasing how language discussing the positive rewards of converting to the ideology were a prominent feature in her online blog. This behaviour was also present in Klausen (Citation2015), where most of the endorsed literature shared by extremist preachers in his Twitter sample, promoted the idea that the individual will only gain meaning from fighting for the ideological goals of the extremist group. Likewise, Baugut and Neumann (Citation2020), found that extremists claimed that they were constantly exposed to martyr propaganda, which described the alleged benefits of dying for the cause and how giving your life for the ideology would allow them to finally find a purpose and gain peace.

Creditability building

Examples of credibility-building language were highlighted by Koehler (Citation2015), where interviewees claimed that the comfortable and accepting language used in online extremist chatrooms and forums, increased the individual’s belief that the extremist group is justified in their violent actions and will succeed in their societal aims. Further positive affirmation was seen in Gerstendfeld et al. (Citation2003), where positive language about the group’s ideology was focussed on the advancement that they were a misunderstood group, with 21.7% of the websites explored containing language promoting the argument that the group does not hate outgroup members. Adding to this, Riebe et al. (Citation2018) highlighted how members of extremist forums will often attempt to discredit any news stories that depict the ideology or its groups negatively, often using language that displays anger and evokes sympathy for their cause, claiming it is being a target by mainstream media.

Religious language

Positive language for the extremist group’s ideology was prominently displayed in the form of religious praise and discussion in Bermingham et al.’s (Citation2009) study, who highlighted how religious references were the most common terminology in their sample of extremist material, with 50% of the top 10 most frequently occurring terms used by users containing religious references (Allah, Islam, Jesus, Muslim, God). Similarly, Torregrosa et al. (Citation2020), reported that not only was religious terminology highly prevalent in their twitter sample, but they also found that extremists used religious terms in their posts more often than the posts of non-extremists. Likewise, Agarwal and Sureka (Citation2015) found religious language to be highly prevalent in their Twitter sample, with a correlation between the use of religious language and language promoting the use of extremist action and activity. Religious language was also most prominent (20%) in Badawy and Ferrara’s (Citation2018) sample. In Windsor’s (Citation2020) case study of Mamood, it was showcased how Mamood used affective language in her blog posts, using both positive and religious language to describe why she does not regret joining ISIS fighters in Syria. She eventually started demonstrating similar linguistical behaviour to the preachers and recruiters in Klausen’s (Citation2015) sample, who utilised religious terminology and positive language in their excerpts when urging users to become a member of the group.

Hate language

Linguistic behaviours that used language to evoke hatred towards individuals who were not a member or follower of the extremist group, were prominent in the results of the selected studies. This behaviour was displayed and presented through two distinct themes: Negative language and hate terminology. Although these themes appear similar, they are distinctly separate, as negative language is identified as any form of language that is used to reject or disagree with something or someone, whereas hate terminology involves language that could be identified as either hostile or offensive.

Negative language

Agarwal and Sureka’s (Citation2015) found that negative emotive language was positively correlated with discussion about ideologies of individuals outside their extremist group. Identified also in Baugut and Neumann (Citation2020), where interviewees claimed that the communication they received and propaganda they read leading up their radicalisation, often involved negative language that portrayed western societies as the enemy and promoted anti-western attitudes. Several participants claimed that the negative language utilised in the extremist propaganda these individuals were exposed to, held western societies as the sole cause of the problematised discrimination Muslim’s experience. Moreover, Bermingham et al. (Citation2009) found negative language being utilised to encourage discrimination against outgroup members but found that males are less negative towards opposing ideologies than females. While Grover and Mark (Citation2019) claimed that negative emotive language had a significant positive correlation with discussions about race and that this negative emotive language increased over time, elevating in every discussion that mentioned outgroup members. Similarly, Riebe et al. (Citation2018) found that majority of their extremist right-wing Facebook comments contained negative language when describing opposing religions and race, often evoking emotive language linked with anger.

Hate terminology

Hate language, which involved offensive terminology against outgroup members, was strongly correlated with Tweets promoting extremist activities in Agarwal & Sureka (Citation2015). Likewise, Badawy and Ferrara (Citation2018), informed that Tweets involving hate terminology made up 6.9% of their overall sample. Bouko et al. (Citation2021) also stated that outgroup members were often referred to as either ‘enemies of Islam’ ‘disbelievers’ or ‘immoral’, highlighting how ISIS promoters would often negatively frame outgroup members as ‘evil’ and utilise up-scaling adverbs (e.g. never, always) to emphasise their claims about outgroup members. Whereas, Gerstendfeld et al. (Citation2003) showcased how hateful language was frequently included in communication on extremist websites, with antisemitic, anti-immigrant, anti-gay, and anti-minority being the most prominent views on these websites. Furthermore, Scrivens (Citation2021) identified hateful language in their sample of extreme right-wing posts, finding the terms ‘vile’, ‘filth’, ‘stupid’, and ‘ignorant’ to be popular terms used by users to describe their perceived enemies, often utilising these terms with derogatory racial and antisemitic terminology. Similarly, Grover and Mark (Citation2019) found hate speech and offensive language were significantly correlated with racial terms, with six of the top eight words utilised by users in their sample containing reference to race. A clear fixation for users of race and racial degradation, was present, often in the form of promoting hate towards outgroup races and ideologies.

Conflict language

The promotion of conflict and violence against outgroup organisations and members was heavily present in majority of the literature, with this high volume of language encouraging conflict being categorised into two separate themes: War language and Segregation language.

War language

Agarwal and Sureka (Citation2015) stated that linguistical features referencing war were predominantly present in Tweets discussing and promoting extremism, with a strong correlation between war-related terminology and hate-promoting language being identified. Awan (Citation2017) found the terms ‘Battlefield’, ‘Victory’, ‘Fight’, and ‘Slaughter’ were some of the most predominant terms used in the sample. While Badawy and Ferrara (Citation2018), identified terminology linked to violence and war was found in 28.4% of the total multiple-themed tweets and was the only theme present in 18.2% of the sample, with the terms ‘To kill’, ‘Fight’, and ‘War’ being some of the most predominantly used terms. Also shared with Benigni et al. (Citation2017), where the promotion of war against the perceived enemy was highly prevalent. Whereas Baugut and Neumann (Citation2020) highlighted how extremist promoters discussed the upcoming ‘apocalyptic’ battle that the group will face, urging followers and other users to join the war and fight for the ideology, aiming their war message against outgroup members, specifically the ‘western enemy’. Lastly, Torregrosa et al. (Citation2020) agreed and reported that extremists utilised words related to upcoming, previous, and predicted wars, often citing territories that the group are currently contesting with their perceived enemies and promoting the upcoming conflict against out-group members.

Segregation language

Caiani and Parenti’s (Citation2009) found that language was used to label ingroup members as ‘allies’ and outgroup members as ‘enemies’, encouraging the segregation between ingroup and outgroup members. Similarly, Awan (Citation2017) found there was a high prevalence of language promoting an ‘Us vs Them’ mentality, with the terms ‘Brothers’ and ‘Rise up’ being some of the most reoccurring words in the sample. Gerstendfeld et al. (Citation2003) also found that the majority of extremist websites involved discourse promoting users to ‘know your enemy’ and promote a unified front with fellow users against outgroup members. Further supported by Bouko et al. (Citation2021), who highlighted that extremist promoters and followers will often use segregation language to promote and empathise the incompatibility of the ingroup and outgroup members, showcasing how ingroup members were described as diverse and moral individuals, whereas outgroup members were depicted as being all similar to each other. Finally, Klausen (Citation2015) found that 13% of all the visual content collected contained linguistic behaviour promoting the brotherhood amongst the group and its fighters.

Discussion

The results revealed that the most predominant language behaviours displayed in the extremist cyberspaces explored by the included research, involved the use of Hate, Negative, Religious, Segregation, and War language. However, despite only one of the three most predominant linguistic behaviours being a subset of the overarching theme ‘Ingroup positivity’ (Religious language), this overarching theme was the most prominent across all the examined research. There was often an overlap between the themes and subsets amongst the literature, with multiple subsets being present in each study. Overall, four of the five overarching language-identified behaviours were prevalent in more than half of the selected literature, except for the language theme ‘Algorithmic language’ which was only identified in three of the selected studies.

Potential dangers of suggestion algorithms

Looking at the overarching theme ‘Algorithmic language’, a potential explanation as to why this language behaviour was only present in a small number of the selected research articles, may have been because of the nature of the present review’s exploration. This review focussed on the language used in extremist cyberspaces, during discussion and interaction with other users in the same cyberspace and selected its studies for review based on whether the research examined extremist language or not. However, the findings were still relevant for the present review, due to the relationship between language and the suggestion functions of the most online cyberspaces. This was demonstrated by the claims made by interviewees in Bauget and Neumann’s study (Citation2020), who claimed it was the use of extremist-linked terminology in their own personal and unrelated online searches that made the algorithm suggest extremist content to them and lead them into the extremist echo chambers that caused their eventual radicalisation. Conway and Mclnerney (Citation2008) discussed this further, highlighting how the online video-sharing platform YouTube can have a massive influence on the radicalisation of an individual, as it uses a suggestion algorithm which provides further content that is similar, or semi-related to the individuals previous watch history. Although the present review was mostly focused on the discourse, language, and narratives that are displayed and communicated throughout the internet, the identified algorithmic language theme highlights an alternative method for individuals to become radicalised online via linguistical influence.

Positive framing as a recruitment tool

This review provides potential evidence that positively framing the ideology and the members of the extremist group is the most common linguistic form of language in online extremist cyberspaces. More specifically, the identified linguistical behaviour ‘religious language’ was the most prominent linguistical method in this prevalent theme, being one of the most identified language types in the whole review. This language was often presented in the format of quotes and references to religious literature, which were often used as a tool to convince new users that the group are justified in their actions, as they are performing them as a service to the religious ideology they follow. The overall effect that this language promoting ingroup positivity appears to have on the users is that it normalises the views of the group and displays the ideology more positively than mainstream medias portray it in (Gagnon, Citation2020). This was showcased further by Huey (Citation2015) who found that one positive framing mechanism utilised by extremist promoters online, is the attempted marketing of Islamic terrorism as a ‘cool’ phenomenon to be a part of, using positive language to describe the ideology and utilising satirically edited images to provoke humorous reinforcement to their messages. By presenting an extreme ideology in a humorous and jovial manner, using positive language, this encourages the viewers of this content to view ideology from a more positive perspective, which possibly normalises the extreme messages the post is promoting.

This normalisation and positive framing of the group and its ideology, potentially encourages the radicalisation process in individuals by increasing their belief that the group follows a justified and positive cause, enticing the individual to want to become a member (Awan, Citation2017). This positive framing of the group’s ideology is then supported by the mass numbers of users on the websites claiming the group is not hate-driven and discrediting any negative comments against the group. This may potentially help build on the perceived credibility of the extremist group to new and outside users, that may potentially be exploring the site out for curiosity or who have been directed there from the suggestive algorithms of the internet. This ingroup positivity helps construct normality in the group’s activities and beliefs, encouraging you to join the group and involve yourself with an online community that have the same social desires and goals (Bouko et al, Citation2021).

Negative framing as a recruitment tool

Whereas ingroup members and activities were positively framed by users of these extremist cyberspaces, outgroup members were described using both derogatory and negative connotations, often framed to be the enemy of all the ingroup members. A potential explanation as to why hate language is a common linguistical tool used by extremists online, is that constant exposure to this derogatory language may decrease an individual’s sensitivity to the harmful content they are being presented to in these extremist cyberspaces (Awan, Citation2017). This then potentially makes them more susceptible to not only joining in on the hateful discourse they are being exposed to, but also being under the mindset that it is acceptable to engage in these hateful discussions (Stevick, Citation2020). Another potential explanation as to why negative and hate language is predominately utilised by extremists on the internet, is that it also helps promote ingroup collectiveness by unanimously publicising that all members of the group have a common enemy, which is most commonly outgroup organisations and members (Bouko et al., Citation2021).

Extremist preachers

One of the most reoccurring linguistical behaviours was the online behaviour of extremist recruiters to metamorphose into a ‘preacher’ role, offering religious advice and instruction to users that approached them. This was often promoted using charismatic and emotional language, facilitating a bond between preacher and follower, building trust and a perceived appearance of honesty to become more approachable (Caiani & Parenti, Citation2009). Baugut and Neumann’s (Citation2020) further stressed that when a preacher approached an interviewee, they first appeared to understand the problems the individual was facing as a vulnerable 15-year-old, suggesting that recruiters attempt to befriend potential new recruits, by acting as a real-world ‘preacher’, listening to the problems of individuals, and offering advice on how to overcome their issues, with their advice often being related to joining the extremist group the preacher is affiliated with.

The present review’s claims are supported by Aly (Citation2017); extremist recruiters will make themselves readily available for engagement in internet cyberspaces and will interact with the online posts of individuals who they identify as potential new recruits. Klausen (Citation2015), previously demonstrated how preachers consistently referred to extremist actions and literature in a narrative language style, before eventually urging an individual to join the battle and find meaning with the ideology. This use of extremist language and promotion of the group through abrasive and unrestricted language, provides the perception that there are no linguistical or authorised constraints on potentially controversial topics within the discussion with the preacher. This then has the potential to provide the illusion of freedom to the individual to discuss controversial topics within the ideological safe space, encouraging the advancement of the radicalisation process (Koehler, Citation2015).

Use of emotional language

Another identified narrative extremist preachers exhibited, was the use of the linguistic device ‘emotional language’, which involved the promotion of battlefield exploits to communicate the story of the battle the group is undergoing against its ‘enemies’ (Bouko et al., Citation2021). This behaviour then encourages group sympathisers to gain hatred for the outgroup opposition inflicting these issues on the group and inspiring these sympathisers to help the group fight their battle (Baugut & Neumann, Citation2020).

Suggesting that, although not majorly represented in the present review, promotion of battlefield exploits might be a fundamental recruitment strategy adopted by online extremist recruiters. This claim is supported by Braddock and Horgan (Citation2016), who found that extremist recruiters will utilise the documentation of their battlefield exploits to provoke emotional reactions from followers and group sympathisers, with these documentation efforts often involving the use of emotional language. The detail that this review was able to identify four subsets of this specific linguistical theme (recruitment language), highlights the varying tactics used by extremist recruiters online. This review overall revealed that preachers seem to use positive framing language to promote a positive image of the ideology, as the main form of linguistical encouragement to influence followers to join their cause. It is then the use of the battlefield connotations and reports to inspire individuals to take the next step and not only support the cause but defend it against perceived opposers.

Promotion of segregation and offline conflict

This desire for individuals to defend their chosen group against perceived enemies would be further influenced by the conflict language that was present in most of the selected literature, which discussed the ongoing ideological war and promoted segregation towards outgroup members. This was also found by Phadke and Mitra’s (Citation2020) cross platform study, where they highlighted a fundamental element of extremist discourse was the purpose of ‘educating’ online audiences about the problems and issues caused by out-group organisations and their members. Adding to this further, Gallacher et al. (Citation2021) stated that extremists use the internet to worsen the relationships between ingroup and outgroup members, with the aim to inspire physically violent offline encounters and discriminatory action towards anyone who is not a follower of the group’s ideology. Therefore, supporting this review’s results, found terminology such as ‘fight’ and ‘slaughter’ (Awan, Citation2017) to be highly prevalent in discourse discussing outgroup members. This language theme of promoting conflict is then utilised to promote a transition in individuals to go from an extremist activist and sympathiser to a radical terrorist who feels justified in their actions and beliefs due to the injustices performed by outgroup oppositions.

Limitations

As highlighted by Garg et al. (Citation2008), there are potential limitations to the results of a systematic review, such as the interpretations of the selected research findings. This may be due to the research that was selected all containing a broad and diverse range of methodology and samples, which may potentially lead to poor quality studies being affiliated with rigorously performed research (Garg et al., Citation2008). This may then consequently lead to the concluding interpretation of the pooled results being weakened in its precision to accurately identify fundamental features of the explored issue. To prevent this potentially negative influence that the varied methodologies would have on the interpretation of the overall pooled results, the present review used a strict inclusion/exclusion criterion, only including research that produced original information about the research question, and data that was sourced from target samples (extremist forums, ex-extremists). As for ensuring the quality of the research, only studies from highly acclaimed research journals were sourced and selected, with each research paper considered being subject to the research quality assurance scoring system outlined by Tawfik et al. (Citation2019). The selection process was also limited by the amount of research related to the specific subject area it investigated, with there being a limiting amount of research exploring online radicalisation language available to extract at the time of this review. However, the research selected not only fit the criterion for this review but was some of the most superlative research studies conducted in this area of research.

Implications and future research

This review provides a further understanding of how language is utilised in extremist cyberspaces; the results could be implemented into practical interventions and counter radicalisation efforts. Although underrepresented in the results, this review highlights the need for further exploration of the language theme ‘algorithmic language’, as it may identify potential problems in current algorithmic software’s adopted by online cyberspaces that extremists are taking advantage of for recruitment. The present review has also highlighted the prevalence of positive framing by extremists online, suggesting this should be investigated by future research when exploring keywords and themes to incorporate into their extremism detection algorithms in online environments. By identifying the problems within algorithmic software, such as highlighting which language typologies and extremist terminologies are not being detected, solutions can be created to make these software’s more accurate at detecting extremist content online and therefore, may reduce the chances of users of these sites being exposed to extremist content, potentially reducing radicalisation rates. The language subsets of the linguistical theme ‘recruitment language’ may also provide identification markers for extremist recruiters online, helping site administrators and law enforcement officials with the detection of these users, as well as having the potential to educate platform users about the warning and identification signs of an extremist in their cyberspace.

Conclusion

In conclusion, extremists use a wide range of linguistical behaviours in their online activities, with each behaviour having its own driven agenda and purpose, but all with an overall aim to promote radicalisation in vulnerable and interested individuals. Online extremists potentially utilise language to shape the perceptions of other users and vulnerable individuals, therefore stressing the need for future research to explore these identified language themes in more detail individually, as they may showcase how extremists utilise the internet to recruit and encourage the radicalisation process over the internet further.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thomas James Vaughan Williams

Thomas James Vaughan Williams At the time of article submission, Thomas James Vaughan Williams had completed his MSc in Investigative Psychology with a distinction and had been offered a fee waiver for a PhD at the University of Huddersfield. Thomas is currently working towards gaining his Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology with a focus on the language used online by terrorists to radicalise and recruit followers and supporters.

Calli Tzani

Calli Tzani At the time of article submission, Dr Calli Tzani was a senior lecturer for the MSc Investigative Psychology and MSc Investigative Psychology at the University of Huddersfield. Dr Tzani has been conducting research on online fraud, harassment, terrorism prevention, bullying, sextortion, and other prevalent areas. See profile at https://research.hud.ac.uk.

References

- Abbasi, A., & Chen, H. (2005). Applying authorship analysis to extremist-group web forum messages. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 20(5), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIS.2005.81

- Agarwal, S., & Sureka, A. (2015). Using KNN and SVM based one-class classifier for detecting online radicalization on Twitter. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Distributed Computing and Internet Technology, 8956(1), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14977-6_47

- Aly, A. (2017). Brothers, believers, Brave Mujahideen: Focusing attention on the audience of violent Jihadist preachers. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 40(1), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2016.1157407

- Awan, I. (2017). Cyber-Extremism: Isis and the power of social media. Social Science and Public Policy, 54(1), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-017-0114-0

- Badawy, A., & Ferrara, E. (2018). The rise of Jihadist propaganda on social networks. Journal of Computational Social Science, 1(1), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-018-0015-z

- Bastug, M. F., Douai, A., & Akca, D. (2020). Exploring the ‘Demand Side’ of online radicalization: Evidence from the Canadian context. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 43(7), 616–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1494409

- Baugut, P., & Neumann, K. (2020). Online propaganda use during Islamist radicalization. Information. Communication & Society, 23(11), 1570–1592. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1594333

- Benigni, M. C., Joseph, K., & Carley, K. M. (2017). Online extremism and the communities that sustain it: Detecting the ISIS supporting community on Twitter. PLoS ONE, 12(12), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181405

- Benson, D. C. (2014). Why the internet is not increasing terrorism. Security Studies, 23(2), 293–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2014.905353

- Bermingham, A., Conway, M., Mclnerney, L., & O’Hare, N. (2009). Combining social network analysis and sentiment analysis to explore the potential for online radicalisation. Advances in Social Network Analysis and Mining, 1(1), 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1109/ASONAM.2009.31

- Bouko, C., Naderer, B., Rieger, D., Ostaeyen, P. V., & Voue, P. (2021). Discourse patterns used by extremist Salafists on Facebook: Identifying potential triggers to cognitive biases in radicalized content. Critical Discourse Studies, 19, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2021.1879185

- Braddock, K., & Horgan, J. (2016). Towards a guide for constructing and disseminating counternarratives to reduce support for terrorism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 39(5), 381–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2015.1116277

- Breidlid, T. (2021). Countering or contributing to radicalisation and violent extremism in Kenya? A critical case study. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 14(2), 225–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2021.1902613

- Caiani, M., & Parenti, L. (2009). The dark side of the Web: Italian right-wing extremist groups and the internet. South European Society and Politics, 14(3), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608740903342491

- Christmann, K. (2012). Preventing religious radicalisation and violent extremism: A systematic review of the research evidence. Youth justice board. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/396030/preventing-violent-extremism-systematic-review.pdf

- Conway, M. (2017). Determining the role of the internet in violent extremism and terrorism: Six suggestions for progressing research. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 40(1), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2016.1157408

- Conway, M., & Mclnerney, L. (2008). Jihadi video and auto-radicalisation: Evidence from an exploratory YouTube study. European Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics, 5376(1), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-89900-6_13

- Doosje, B., Moghaddam, F. M., Kruglanski, A. W., de Wolf, A., Mann, L., & Feddes, A. R. (2016). Terrorism, radicalization and de-radicalization. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11(1), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.06.008

- Gagnon, A. (2020). Far-right framing processes on social media: The case of the Canadian and Quebec chapters of soldiers of Odin. Canadian Review of Sociology, 57(3), 356–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12291

- Gallacher, J. D., Heerdink, M. W., & Hewstone, M. (2021). Online engagement between opposing political protest groups via social media is linked to physical violence of offline encounters. Social Media + Society, 7(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120984445

- Garg, A. X., Hackam, D., & Tonelli, M. (2008). Systematic review and meta-analysis: When one study is just not enough. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 3(1), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.01430307

- Gattinara, P. C., O’Connor, F., & Lindekilde, L. (2018). Italy, no country for acting alone? Lone actor radicalisation in the Neo-fascist milieu. Perspectives on Terrorism, 12(6), 136–149. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/26544648.pdf

- Gerstendfeld, P. B., Grant, D. R., & Chiang, C. P. (2003). Hate online: A content analysis of extremist internet sites. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 3(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2003.00013.x

- Grover, T., & Mark, G. (2019). Detecting potential warning behaviors of ideological radicalization in an alt-right subreddit. Thirteenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 13(1), 193–204. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/3221

- Huey, L. (2015). This is not your mother’s terrorism: Social media, online radicalization and the practice of political jamming. Journal of Terrorism Research, 6(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.15664/jtr.1159

- Klausen, J. (2015). Tweeting the jihad: Social media networks of western foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 38(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2014.974948

- Koehler, D. (2015). The radical online: Individual radicalisation processes and the role of the internet. Journal For Deradicalisation, 1(1), 116–134. http://journals.sfu.ca/jd/index.php/jd.

- Kruglanski, A. W., Gelfand, M. J., Belanger, J. J., Sheveland, A., Hetiarachchi, M., & Gunaratna, R. (2014). The psychology of radicalization and deradicalization: How significance quest impacts violent extremism. Political Psychology, 35(1), 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12163

- Kundnani, A. (2012). Radicalisation: The journey of a concept. Race & Class, 54(2), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396812454984

- McCauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2014). Toward a profile of lone wolf terrorists: What moves an individual from radical opinion to radical action. Terrorism and Political Violence, 26(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2014.849916

- McCauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2017). Understanding political radicalization: The two-pyramids model.. American Psychologist, 72(3), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000062

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(143), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Neumann, P. R. (2008). Chapter two: Recruitment grounds. The Adelphi Papers, 48(399), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/05679320802686809

- Odag, O., Leiser, A., & Boehnke, K. (2019). Reviewing the role of the internet in radicalization processes. Journal For Deradicalization, 21(1), 261–300. https://journals.sfu.ca/jd/index.php/jd/article/view/289

- Patrick, S. A. (2014). Framing terrorism: Geography-based media coverage variations of the 2004 commuter train bombings in Madrid and the 2009 twin suicide car bombings in Baghdad. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 7(3), 379–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2014.957009

- Phadke, S., & Mitra, T. (2020). Many faced hate: A cross platform study of content framing and information sharing by Online Hate Groups. CHI Conference on human factors in computing systems, Honolulu. Hawaii, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376456

- Riebe, T., Patsch, K., Kaufhold, M. A., Reuter, C., Dachselt, R., & Weber, G. (2018). From conspiracies to insults: A case study of radicalisation in social media discourse. Mensch und Computer 2018: Workshopband. (pp. 595–603). https://dl.gi.de/bitstream/handle/20.500.12116/16795/Beitrag_449_final__a.pdf

- Scrivens, R. (2021). Exploring radical right-wing posting behaviours online. Deviant Behaviour, 42(11), 1470–1484. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2020.1756391

- Scrivens, R., Davis, G., & Frank, R. (2018). Searching for signs of extremism on the web: An introduction to sentiment-based identification of radical authors. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 10(1), 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2016.1276612

- Stevick, E. D. (2020). Is racism a tactic? Reflections on susceptibility, salience, and a failure to prevent violent racist extremism. Prospects, 48(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-019-09450-4

- Tawfik, G. M., Dila, K. A. S., Mohamed, M. Y. F., Tam, D. N. H., Kien, N. D., Ahmed, A. M., & Huy, N. T. (2019). A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Tropical Medicine and Health, 47(46), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-019-0165-6

- Torregrosa, J., Thorburn, J., Lara-Cabrera, R., Camacho, D., & Trujillo, H. M. (2020). Linguistic analysis of pro-ISIS users on Twitter. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 12(3), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2019.1651751

- Vergani, M., Iqbal, M., llbahar, E., & Barton, G. (2020). The three Ps of radicalization: Push, pull and personal. A systematic scoping review of the scientific evidence about radicalization into violent extremism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 43(10), 854. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1505686

- Windsor, L. (2020). The language of radicalization: Female internet recruitment to participation in ISIS activities. Terrorism and Political Violence, 32(3), 506–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2017.1385457