ABSTRACT

Despite being recognised as the foundational process of an extremist group exit [Morrison, J. F., Silke, A., Maiberg, H., Slay, C., & Stewart, R. (2021). A systematic review of post-2017 research on disengagement and deradicalisation. Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats. https://crestresearch.ac.uk/download/3797/21-033-02.pdf], identity transformation is surprisingly under-investigated. This paper therefore explores how identity is represented in the exit process by examining ten autobiographies written by right-wing formers. The data were analysed using thematic analysis, and three themes were developed and named: ‘is this who I am?’, fatherhood, and reinventing the self. Drawing on social identity theory [Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–37). Brooks/Cole], the article proposes that emotionally laden cognitive openers can alter intergroup evaluation and social identity satisfaction. Certain cognitive openers, such as fatherhood, were seen to strongly influence the former’s self-categorisation and personal identity. The analysis also found that rebuilding an alternative identity after leaving the group took significant time and effort. The paper highlights the complexities of identity transformation during and after an extremist group exit and suggests that the process can involve changes to both personal and social identity structures.

Introduction

Recent terrorism and extremism research increasingly focuses on the processes of disengagement (behavioural change), deradicalisation (ideological change) and reintegration (see e.g. Barrelle, Citation2015; Bjørgo & Horgan, Citation2009; Horgan et al., Citation2017; Marsden, Citation2016; Morrison et al., Citation2021; Silke et al., Citation2021; Windisch et al., Citation2016). Several scholars have performed a systematic review of the field in order to provide an overview of group exit factors. Dalgaard-Nielsen (Citation2013), for example, examined the literature published between 1990 and 2012 on voluntary disengagement from violent extremism and found an array of internal and external factors including ideological doubt, dissatisfaction with internal dynamics, and personal and practical circumstances. Windisch et al. (Citation2016) conducted a systematic review of 114 articles published between 1970 and 2015. By examining the broader multidisciplinary disengagement literature, they found disillusionment and social relationships outside the movement to be the main reasons for disengagement. In 2018, Dalgaard-Nielsen performed a second literature review on voluntary disengagement in the West. In her review of case studies and articles using primary sources between 1990 and 2016, Dalgaard-Nielsen identified three cross-cutting themes: ideological disillusionment, disappointment in peers or leaders, and changes in the group member’s personal priorities (Citation2018).

Although these early works often found similar push-and-pull factors influencing the decision to leave extremist groups, they were criticised for lacking empirical support and for using secondary sources (Schuurman & Eijkman, Citation2013). However, in the last couple of decades, researchers have tended to use more primary sources and better data-gathering procedures (Schuurman, Citation2020), and generated sounder theories (Silke & Schmidt-Petersen, Citation2017). Because of this shift, Morrison and colleagues (Citation2021) performed a literature review of the 29 most analytically sound articles published in the field of disengagement and deradicalisation research between 2017 and early 2020. This review prompted the development of the Phoenix model of disengagement and deradicalisation (Silke et al., Citation2021). The model presents three groupings of catalytic processes associated with extremist group exits: actor catalysts (family and friends, programme interventions and formers), psychological catalysts (disillusionment and mental health), and an environmental catalyst (prison). Additionally, (dis)trust, perceived opportunity, and security concerns were found to be ‘filter variables’ pivotal to creating a successful reintegration. Most importantly, and markedly different from previous literature reviews, the Phoenix model presents identity transformation – either the creation of a new identity or the re-emergence of elements of an old one – as foundational to an exit process.

Despite the importance of identity transformation in exiting extreme groups, there is little research focusing on it. Ebaugh (Citation1988) has explored the process of ‘becoming an ex’ from a range of roles including ex-convicts, and her work has been used in studies of extremist group disengagement (see e.g. Altier et al., Citation2014; Horgan et al., Citation2017). Ebaugh describes the importance of incorporating the old role identity into the new self-concept, which, according to Joyce and Lynch (Citation2017), is an area that needs exploring within research on political offenders. Indeed, Syafiq (Citation2019) notes tension in the sense of self of former Jihadi prisoners in Indonesia that was caused by previous group-related identities. Simi et al. (Citation2017) discuss unwanted behavioural, emotional and cognitive group-related ‘identity residuals’ that can persist long after leaving, and Christensen (Citation2019) argues that ‘self-transformation’ is an important and lengthy part of reintegration after participating in an extremist right-wing (RW) group, requiring both personal strength and high motivation. One study of ten interviews with former RW extremists in Canada reported that formers felt directionless when they chose to exit because they lacked a social network and a ‘prescriptive ideological framework’ (Bérubé et al., Citation2019, p. 83), and Hakim and Mujahidah (Citation2020) found that lack of support can make the new identity difficult to maintain and may lead to recidivism. All in all, previous research on identity transformation in the exit from extremist groups depicts a difficult and complex process.

Given the foundational role attributed to identity transformation in Silke et al.'s (Citation2021) Phoenix model, the concept could benefit from drawing on established identity theories, as has already been done in relation to the recruitment process (see e.g. Hogg, Citation2007). This article will make use of Tajfel and Turner’s (Citation1979) social identity theory (SIT) to shed light on how identities are transformed in the exit process. It will do so by analysing how individuals describe the self, thus addressing two research questions:

How is identity transformation in the exit process narrated by male former members of RW extremist groups?

How can theories of identity contribute to understanding these exit processes?

Autobiographies

In order to answer the research questions, the researcher needed rich data that described changes to identity over time. Despite an early call for scholars to take an emic perspective using memoirs written by terrorists (Rapoport, Citation1987), very little research has in fact done so (see Altier et al., Citation2017 for an excellent exception). Indeed, primary sources are underutilised in terrorism research, particularly within RW extremism (Neumann & Kleinmann, Citation2013; Silke, Citation2018). Autobiographies written by former members of extremist groups were therefore chosen as the data source for this analysis, as they provide an emic perspective on the process of identity transformation. This section will discuss what an autobiography is and the benefits and limitations of using autobiographies as empirical data.

Typically, an autobiography is ‘the history of the life-story of the author’ (Sargar, Citation2013, p. 2) – a story written about and by the same person. The author of an autobiography chooses what to present, often with the aim of creating a story of personality growth (Gergen & Gergen, Citation1988). To create a sustained and interesting narrative, autobiographies often focus on critical events (Altier et al., Citation2012). Although the focus in an autobiography is largely the individual’s personal experience, it also presents the social structure in which the self is negotiated (Sargar, Citation2013) and can therefore provide insight into both individual and social contexts (Brockmeier, Citation2012).

In their evaluation of autobiographies as data in terrorism research, Altier et al. (Citation2012) argue that autobiographies enable the study of processes over time, as they typically span most of the individual’s life and many aspects of group involvement. Furthermore, unlike interviews, using autobiographies as data means that the primary text is not influenced by the researcher’s own questions, opinions or preconceptions, nor by the power dynamics of the interview or the particularities of the setting. There are practical advantages to using autobiographies, too. Studying written accounts helps reduce the number of interview requests many formers receive, avoids the ethical challenges related to interviewing formers and reduces the time and money spent obtaining appropriate data.

Scrivens et al. (Citation2020) argue that autobiographies have particular value for research into disengagement and the combating of violent extremism due to the complexity of these processes, as well as the unique insights formers can provide. The autobiography is a form that allows authors to think deeply about the stories they wish to tell. Another advantage of using autobiographies is the opportunity they provide to explore psychological and unobservable elements of extremist group participation, given the need to look at what is important to the individuals themselves in relation to their group participation (Blee, Citation2021). The length and detail of autobiographies allows authors to explore these everyday aspects of group participation.

Analysing autobiographies also brings challenges, however. A major consideration is that formers will be selective about the information they are willing to present to a broader audience and can be motivated by political goals (Cordes, Citation1987). This may be particularly relevant here, as most of the authors of the autobiographies selected for this research have gone on to work in preventing and countering violent extremism (P/CVE). The books are reviewed by a publishing editor, who may choose to exclude controversial events due to safety risks (Altier et al., Citation2012), or may only want to publish sensational stories or choose to promote certain aspects of the narrative to increase interest in the book. One may also speculate that individuals who write autobiographies are not typical of all extremist group members (Shapiro & Siegel, Citation2012), as is also the case for formers who agree to be interviewed (Altier et al., Citation2021). For example, many of the authors held leading positions in their groups and have high-profile media presence after leaving. It is also reasonable to assume that individuals who struggled with their reintegration process are less likely to write about their past for publication. All of these factors mean that one must be cautious in generalising the findings to a larger population, and replication of the analysis with different types of data is strongly encouraged. Nevertheless, studying autobiographies is a way of gaining insight into the exit processes of ‘successful’ formers.

Theoretical framework

The main theoretical framework for this article is SIT. This was first introduced to help understand intergroup conflict and prejudice (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979) and has since been used to explain dynamics within terrorism recidivism (Hakim & Mujahidah, Citation2020) and ex-political prisoners’ understanding of their new roles as prevention workers (Joyce & Lynch, Citation2017). SIT proposes that individuals have a fundamental need to develop a positive social identity by participating in a group where members value distinctiveness from other groups. Self-esteem and positive self-evaluation are therefore a result of the individual’s perceived social position and belief in the in-group, a key term in SIT (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979; Turner & Oakes, Citation1986). Social categorisation – the process of assigning oneself to a certain group – is internalised over time and can sometimes become more powerful than individual self-interest (Turner, Citation1975, Citation1978). Personal identity, understood as the self-categories that define the uniqueness of a person compared to other in-group members (Turner et al., Citation1992), can therefore become less important as social identity is strengthened (Turner, Citation1982).

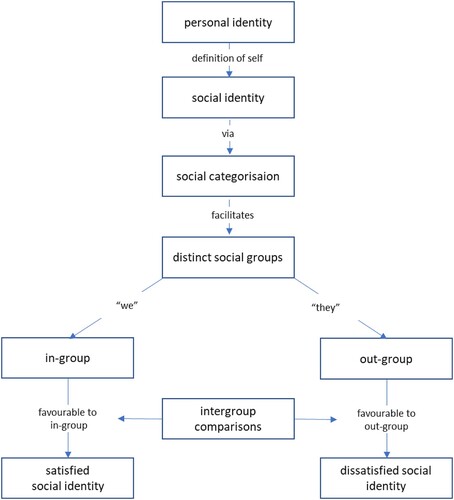

SIT explains prejudice as a result of intergroup relations rather than attributing it to the personality of the individual (Turner & Reynolds, Citation2010). In turn, intergroup relations shape the group’s and the individual’s collective and ideological behaviour (Turner & Reynolds, Citation2010). shows the central position of personal identity and intergroup comparisons in the creation and maintenance of a social identity.

Although SIT does not primarily focus on social identity transformation, it posits that transformation can occur when intergroup comparisons favour the out-group, creating dissatisfaction with the current social identity. SIT is therefore useful for the present study because it provides a framework to explain why people chose to stay or leave an extremist group based on their understanding of self. More specifically, the theory can help explain the different ways in which an individual can go from favouring an in-group to opposing it.

Self-categorisation theory (SCT) extends the conceptualisation of social identity by emphasising the distinction between personal and social identity (Turner & Reynolds, Citation2001), and the change to one’s self-categorisation (the way an individual positions themselves in relation to others) (Turner, Citation1975). Individuals are strongly motivated to maintain both a positive self-categorisation and to be in harmony with their group (Turner & Reynolds, Citation2010). SCT hypothesises that group processes happen when individuals start thinking of themselves as a social category rather than as an individual, and such processes have previously been highlighted in relation to radicalisation into extremist groups (see e.g. Harris et al., Citation2014). Thus, self-categorisation is a reflexive process of social contextual judgement (Turner, Citation1988; Turner et al., Citation1992). This theory is particularly useful when trying to explain why certain experiences have greater influence than others over the decision to leave by exploring how changes to the categorisation of self can create behavioural and ideological change.

Methods

Data selection

The autobiographies included in this analysis were found on the publicly available resource page created by the CitationCentre of Research on Extremism (C-REX). As all the autobiographies were in the public domain, it was not necessary or relevant to apply for permission to use this data. They were selected according to the following criteria:

– Written in English or a Scandinavian language, which are the languages the researcher understands.

– Written by men. The inclusion of women would not have altered the research questions or theoretical framework but may have changed the findings, as previous research has indicated gender differences in the way in which an exit is experienced (Latif et al., Citation2020). Reversely, we cannot assume that the narratives would be markedly different. Future studies including authors of all genders would therefore be desirable.

– Include a substantial amount of self-reflection.

– Written by or with the former to ensure closeness to the source and strong validity (Ross, Citation2004). Collaborative autobiographies were included because they were presented in the voice of the former and provided answers to the research questions under investigation.

Table 1. An overview of analysed autobiographies, with translated titles in italics.

Analysis

The analysis was carried out in 2021–2022 and builds on principles from thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). During the reading of the first book which was written by Eiternes, a list of potential codes was developed. As further books were read, more codes were created, usually exemplified with a quote. It became clear that the codes described different parts of the exit process, and overarching themes started to emerge. Each new autobiography offered an opportunity to identify, confirm, redefine, and merge new codes and consider how they related to the overarching themes. If new codes were developed, the researcher would return to the previous books to see whether this new code had relevance there too. The analytical process was therefore a dynamic and labour-intensive endeavour. No coding software was used. After reading the ten autobiographies, the list of codes and themes was revisited. Some codes were combined and others were dropped, such as those primarily relating to identity during the recruitment process or group involvement. Three themes that represented topics central to the former’s description of identity transformation were developed and given descriptive names. The themes cover different aspects of identity transformation during the exit process and help answer the research questions. Subcategories were also developed for each theme. Importantly, the research questions, the chosen theoretical framework and the researcher’s background as a clinician guided the reading of the material, so there will necessarily be other ways in which the books can be read that can offer insights and value to reintegration initiatives.

Findings and discussion

In this section the three themes are presented: ‘is this who I am?’, ‘fatherhood’ and ‘reinventing the self’. Each theme ends with a subsection discussing the findings from a theoretical perspective.

Is this who I am?

This theme is concerned with the psychological processes that were described by the authors as triggering an identity transformation and leading to the decision to leave the group. The three subcategories within this narrative describe a particularly important moment that starts the exit process, the emotional nature of this moment, and recurrent moments of uncertainty. The final subcategory discusses theoretical considerations related to this theme.

Turning point

Towards the end of his book, Christian, a former leader of the white-power skinhead group Hammerskins and a singer in a supremacist punk band, writes: ‘Along with my breath, my commitment was knocked out of me for the first time, and for a brief moment I clearly saw there was a serious problem with my reality’ (Picciolini, Citation2017, p. 211). Christian has just experienced a sudden yearning to be at home with his pregnant wife rather than at the Klu Klux Klan rally he is attending. Such sudden turning points occur in eight of the ten autobiographies, and they are all described as surprising and unexpected. They were not, therefore, situations that the formers had approached with the intention of having their views questioned or altered. For Ray, a founder member of the British National Party in the 1970s, the turning point was a chance meeting with a family who were living on the street as a result of his group having campaigned for their eviction. Tom, a former neo-Nazi from Norway, was not shot whilst being robbed by a group of young South African men in Johannesburg despite expecting to be because the young men were black. Participation in an especially violent attack on elderly minority women was the turning point for Matthew, a former member of Hammerskins in the UK, as he realised they were harmless and not the real enemy. For Christian, Johan (a Swedish RW former), Tony (a former member of White Aryan Resistance in Canada), and Arno (a former skinhead and vocalist in a white-power band in the USA), becoming a father was the turning point. Because of its particular significance for many of the formers, as well as the unique identity transformation that it occasioned, the theme of fatherhood will be presented separately.

Emotional breakthrough

One prominent feature of these turning points is that they are consistently interpersonal and emotional. The emotional turning point contrasts with the previous non-responsiveness to both ideological and experiential situations. That is, none of the turning points were triggered by an incident directly linked to ideological pushback but were described as highly emotional experiences that precipitated the re-evaluation of RW ideology and the individual’s role within the group. Johan talks about how the overwhelming emotion of holding his son Leon for the first time made him immediately feel different within himself: ‘There and then I could feel how my heart was reopened, after all these years someone finally managed to tear down the walls that I had built up. In only a few seconds’ (Egonsson, Citation2012, p. 122, online version). This powerful experience ultimately led Johan to make the final decision to leave his violent existence behind: ‘There and then I gave myself and Leon a promise, all the arguing and fighting would end from now on’ (Egonsson, Citation2012, p. 122, online version).

The futility of using ideological arguments to encourage attitudinal or behavioural change is also discussed. Christian describes how he tried this very thing himself, despite knowing it would not help: ‘I had arguments with my brother about the path he was on, lecturing him even though I knew there was no way my words would penetrate’ (Picciolini, Citation2017, p. 258). Tony describes his strong commitment to the ideology at the height of his group membership: ‘There was nothing anyone could have said or done then that would have convinced me to alter my path’ (McAleer, Citation2019, p. 110). When asked by a tour guide whether he would have believed the Holocaust had happened if he had gone to Auschwitz during the time of his group membership, he responds:

To that I had to honestly answer no. During this time in my life, I was too emotionally numb to have been able to feel this place, too arrogant, with too much invested in my identity that was wrapped around white supremacist ideology, to be able to admit that I was wrong. (McAleer, Citation2019, p. 203)

Reinforcement

Whilst the turning point is described as powerful, many incidents follow that are described as reinforcing the psychological turning point before an ideological and/or behavioural exit from the group takes place. As Ray puts it, the first turning point event wasn’t ‘entirely a road to Damascus conversion’ (Hill & Bell, Citation1988, p. 60). The recollection of several important turning points is particularly apparent in Johan, Tony and TJ’s books, but all the formers acknowledge that several events led to their group exit. A period of re-evaluation seems to be an integral part of group exit for all ten authors, though it varies greatly in timespan and intensity.

Many of the subsequent incidents are meetings with individuals from the out-group, meetings the authors might not have permitted themselves prior to the initial turning point. For example, Ray became friendly with some Jewish men who didn’t judge him, and Frank, a former white supremacist skinhead from Philadelphia, started working for a Jewish antiques dealer. These interactions are described as eye-opening because they contradict previously held beliefs. Frank talks about his Jewish boss like this:

I realized something about the Jews: until Keith, I’d never met one … But I had a whole lot of theories about the Jews, and until I met Keith Goldstein, I would’ve sworn I had facts to back every one of those theories. Then I met Keith and the fact was he disproved every theory I had. (Meeink & Roy, Citation2017, p. 226)

‘Is this who I am?’ – theoretical considerations

Unexpected moments of insight are frequently presented as the first crucial challenge to identity. Ebaugh also describes a turning point, though for many of the informants in her study specific events served to crystallise an already held ambivalence (Citation1988, p. 125). In the crime desistance literature, cognitive transformations (including ‘hooks for change’, which is similar to what is described here) have been found to direct future normative behaviours (Giordano et al., Citation2002).

In the psychological literature, a turning point that induces radical change to a belief system has been aptly described as a ‘cognitive opening’. The concept was introduced as part of social movement theory to explain recruitment into radical Islamism (Wiktorowicz, Citation2004). It is defined as an incident or crisis that ‘shakes certainty in previously accepted beliefs and renders an individual more receptive to the possibility of alternative views and perspectives’ (Wiktorowicz, Citation2004, p. 7). A cognitive opening can be induced by economic change (loss of job, perceived social immobility), social/cultural experiences (racism, humiliation), political hardship (political discrimination, torture, repression) and/or personal incidents (death in the family, family feuds) (Wiktorowicz, Citation2004).

Although Wiktorowicz uses cognitive openings in relation to the recruitment process, they can also be understood as a moderating factor of intergroup evaluation. While their in-group and out-group may not have changed, the authors describe a sudden re-evaluation of them. The cognitive opening therefore creates discord in the intergroup comparison, allowing the legitimacy of the group’s ideology and the member’s social identity to be questioned.

Prior to the cognitive opening, most of the author’s interpretive framework was rooted within the group’s ideology, which resulted in a favourable in-group comparison and a satisfied social identity. The cognitive opener is occasioned by important incidents where the intergroup comparisons favour the out-group, providing the group member with an opportunity to consider alternative theories/beliefs. This cognitive opener is crucial to the former’s narrative because it represents the start of a more balanced intergroup comparison, which in turn increases the dissatisfaction with the currently held social identity. Similarly, Hareven and Masaoka (Citation1988) propose that a turning point is a process involving ‘course correction’ rather than an isolated event that causes a sudden jump from one phase to another.

Although the nature of the incidents differs, they result in increased scepticism of the in-group and decreased scepticism of the out-group. A reoccurring and important example of the latter is positive interactions with out-group members, which reduce the strength of a social identity that is dependent on intergroup conflict. These interactions play a significant part in the exit process for the majority of the authors. The positive effect of out-group interaction could be explained by intergroup contact theory (Pettigrew, Citation1998). In a meta-analysis of 515 studies, Pettigrew et al. (Citation2011) found that intergroup contact reduces prejudice in most cases. They found that reduced prejudice extends beyond individuals to the entire group they represent, and even to other groups that are not involved in the actual meeting.

Fatherhood

The second theme is concerned with becoming a father, which was described as key to the decision to leave by five of the authors. Fatherhood is presented as a cognitive opener, a new identity and a process of personal growth that is explored and maintained during the author’s group exit and life after leaving. This section concludes with a discussion of how fatherhood can become relevant at different times, influence different phases of the exit process, and can contribute towards the modification of personal identity.

Fatherhood as turning point

All the expectant fathers describe delight about the forthcoming arrival, partly because they see it as a duty to bring more white children into the world. Its particular importance could be explained by most RW groups’ belief in the great replacement theory – the idea that mass immigration of non-whites threatens the existence of white Westerners (see e.g. Obaidi et al., Citation2021). Arno puts it like this: ‘My daughter was conceived in acknowledgement to the shared belief of her mother and I that it was our duty as racially-conscious white people to produce white children’ (Michaelis, Citation2010, p. 93). Although most of the pregnancies were unplanned, the prospect of fatherhood excited the formers because it advanced their ideological cause, and the importance of fathering children was therefore established from the outset.

However, although anticipation of a child’s arrival evoked pro-group emotions, once the child was born it was described as an important cognitive opener. In fact, for most of the fathers, parenthood was the main reason for moving away from the group. This change of function is a remarkable example of the discrepancy between expectation and actual experience. Rather than inducing feelings of empowerment and righteousness, the baby unlocks unexpected emotions and insights. As Christian says: ‘The birth of our son changed my life. I started to imagine the world through his eyes, still unsullied by any prejudice’ (Picciolini, Citation2017, p. 215).

Fatherhood as a process

Although described as life altering, experiencing life with a small child supported a gradual move away from the movement rather than an immediate one. For instance, TJ and Tony were still in the group after the birth of their second children. TJ recognises that fatherhood was not enough to change his mind entirely: ‘The birth of my son made me start to wake up to the dangerous world I had created … but one eye was still closed’ (Leyden, Citation2008, p. 90). TJ does not attribute the initial cognitive opener to his children but to a violent event he participated in. He does, however, describe a powerful moment of realisation when his three-year-old son turns the television off because there are black people on it:

I looked at my child, Tommy, who was sweet and pure and the light of my life. My eyes became open to the innocence I had stolen from him, and that I was doing the same to Konrad. Over the next several months, I began to fiercely question my deepest-rooted beliefs and values. (Leyden, Citation2008, p. 124)

nor did I want her or the child we would have to be any part of the hostility that surged through the gatherings. I had begun to recognize that a paradox existed in the white-power movement – a movement dominated by insecure men – where outwardly we’d praise white women as warriors … but the truth is that in closed quarters women were often treated worse than the people we claimed to hate. (Picciolini, Citation2017, pp. 206–207)

For some fathers, behavioural change precedes ideological change, as the main priority was to remove the child from an unsafe environment. Arno describes this in two phases: ‘Before I had fully shed my ideology, I called off the race war with the realization that my daughter needed me’ (Michaelis, Citation2010, p. 98). He later goes on to label his daughter’s early childhood as a reason for the re-evaluation of his ideological beliefs: ‘The pure beauty of her childhood is what ultimately demonstrated just how terribly wrong I had been’ (Michaelis, Citation2010, p. 100). Arno exemplifies how fatherhood can alter someone’s behavioural and ideological standpoint over time, creating sustained change.

From group member to individual

As the welfare of the child becomes more important than group membership, and being a group member and a good father seem increasingly incompatible, the authors describe a shift in their priorities. Tony presents the change like this: ‘My children had tipped the scale to become priority number one. I was number two, and the movement was now number three. I started to wonder how I could refigure my life to reflect this new order’ (McAleer, Citation2019, p. 138). This quote shows that Tony is consciously creating a demarcation between himself and the group. Self-awareness is also present when the authors reflect on their own fathers and not wanting to recreate the poor father–son relationships they had themselves experienced but to be better role models for their children. Tony has this realisation in a prison cell: ‘I wasn’t there for him. In putting the white supremacist movement before my children, I was acting just like my dad – the father I had sworn never to be like’ (McAleer, Citation2019, p. 119). The lack of a positive father figure is echoed in all the books except Tom’s, where the support of his family played an important role in his reintegration process. Relatedly, the new role as a father can sometimes be reinforced by increased involvement from supportive parents who are invited back into the group member’s life.

Fatherhood – theoretical considerations

Becoming a father is a significant psychological event in most societies (LaRossa, Citation1997), and has been recognised as a reason for leaving extremist groups in the past (Bjørgo, Citation2008; Reinares, Citation2011; Windisch et al., Citation2016). The analysis found fatherhood to be a particularly strong cognitive opener for four of the authors, prompting them to create a new self-categorisation of themselves as more than a group member. From a social identity perspective, bringing white children into the movement should represent a positive contribution to the in-group, strengthening the men’s social identity and status. Parenthood has indeed been found to sustain activism in white-power movements in the U.S. (Simi et al., Citation2016). However, having children had the opposite effect for the authors, initiating doubt about the legitimacy of the group and the social identity they held within it. This is consistent with Wiktorowicz’s (Citation2004) theory that changes in personal situation can trigger cognitive openings. Questioning the legitimacy of a social identity is one of the main drivers for identity change (Turner & Reynolds, Citation2010). It is interesting to note that for the new fathers, the change in intergroup evaluation was consistently the result of changes in their personal circumstances as opposed to changes within the group, the latter of which has been recognised as a reason for group exits elsewhere (see e.g. Barrelle, Citation2015).

The authors reported a shift from a collective to a more self-aware way of thinking after becoming fathers. As SCT proposes, the importance of personal identity depends on social context (Turner et al., Citation1994). The sudden shift in priorities on becoming a father suggests that fatherhood presents an opportunity for the personal identity to gain, and in some cases regain, relevance. Indeed, SCT claims that social change can lead to a re-evaluation of an individual’s self-categorisation (Turner & Reynolds, Citation2010). Following their re-categorisation as father/protector, the authors describe becoming more aware of their individual needs, thus increasing the importance of their personal identity and reducing their group-related social identity. Although the cognitive opener initially affects self-categorisation, the fathers also describe a gradual change to the intergroup comparison similar to those experienced with other cognitive openers. However, because fatherhood directly affects the group member’s personal identity, additional considerations regarding individual preferences are added to the intergroup comparison. Becoming a father is therefore a particularly robust cognitive opener, because it induces changes to both personal and social identity.

The two-fold influence of fatherhood as a cognitive opener can explain why it sometimes initially causes behavioural rather than ideological change. As the new role initially provides alternative self-categorisation as a protector, behavioural change prompts the prevention of their children experiencing physical or emotional harm. Importantly, most of the fathers retrospectively attribute both behavioural and ideological change to having children, regardless of how long the process took. Very little research has been done on how fatherhood influences exits from extremist groups. However, there are studies within the field of crime desistance that consider fatherhood a turning point away from crime for young offenders (Sampson & Laub, Citation1995; Turner, Citation2017), and a resource for reintegration into society (Sandberg et al., Citation2020) because it allows them to imagine a new future. Although these articles focus on fatherhood rather than becoming a father, they too conclude that fatherhood can play a crucial role in positive change away from belligerent behaviours. SIT and SCT offer a theoretical explanation of why such behavioural changes occur.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that fatherhood may hold such an important narrative position because of its permanence and continuousness. Becoming a father is an easily accessible reference point: the child did not exist prior to recruitment and group involvement but is part of the former’s life, both when the decision to leave is made and during the authoring of the book. Children therefore continue to be a reminder of their role as a father and help maintain a self-categorisation that did not exists before group membership. It should also be noted that although fatherhood is the single most frequently given reason for a change of heart, it is by no means the only one.

Reinventing the self

The last theme includes four interrelated subcategories and will explore the authors’ retelling of their efforts to transform their identity after leaving, an area of research far less explored than disengagement (changes to behaviour) and deradicalisation (changes to beliefs) (Joyce & Lynch, Citation2017). As with the other themes, the final heading discusses theoretical considerations.

Identity and ideology

Most of the formers struggled with exiting their group due to their attachment to their group-related identity. This quotation from Christian succinctly captures the internal conflict most of the formers felt before leaving: ‘Despite my growing reservations about the whole white-power movement, I found it very hard to let it go. It had been my entire identity from the age of fourteen, and I still savored my role as a leader’ (Picciolini, Citation2017, p. 221). Christian found it hard to let go of what had been an all-encompassing group identity. For most of the authors, the group had provided an opportunity to create a strong and distinct identity for the first time in their lives, an identity strongly linked to the group’s ideology. Tony describes it this way:

The difficulty that I had was that so much of my identity was invested in the ideology of white supremacy that I was not yet ready to give it up. The conundrum for anyone who is deeply dedicated to an extremist ideology is that identity and ideology become intertwined. (McAleer, Citation2019, p. 131)

To walk away from the thing you have fought for and believed in for many years is not easy. Sometimes it felt like I was losing the very meaning of life. To lose the ideology was a loss I almost had to grieve before I could move on and create new opinions and values. (Eiternes & Fangen, Citation2002, p. 190)

Feeling lost

Most of the authors describe a period of psychological turmoil after leaving. The former who had made the least progress in his exit process at the time of writing his autobiography, Johan, provides rich insight into how disorientating, laborious and drawn out the process of creating a new and meaningful existence can be. Like the others, Johan describes the struggle to leave in terms of the uncertainty of his imagined future:

It’s not like I enjoyed the life I was living, but it was the only one I knew then. The fear of something new can be scary for anyone. And I had been living in this dark world for so long it was hard for me to break the pattern. (Egonsson, Citation2012, p. 108, online version)

Levels of effort

The authors describe very different levels of effort with regards to social identity formation before and after group membership. For most of the formers, group entry required very little effort. They describe the transition into the group as swift, particularly if they had experienced little satisfaction with their social identity prior to joining. Recruiters knew how to offer a powerful and fully formed social identity. Matthew, a former member of the National Front and Combat 18 in London, described his entry like this: ‘A few meetings in a few pubs, a few hours walking around housing estates with leaflets, and I was a permanently changed individual’ (Collins, Citation2011, p. 24). This lack of regard for consequences during a group entry could be interpreted as a disclaimer, and the authors attempt to portray themselves as innocent and vulnerable in their own recruitment process. Although the descriptions may partly serve this function, the consistency in the stories, and the way in which the RW groups targeted very young people in their recruitment, suggest that these circumstances are common.

The exit process is clearly very different. The authors emphasise that great determination was needed to make their exits. Establishing a positive new identity is difficult because of the enormous loss of social identity. Tony describes more than 1000 hours of therapy, as well as periodic urges to return to the movement. Frank struggled with alcohol and drug abuse long after leaving and still found this a challenge at the time of writing his book. He draws parallels between moving away from the group and the 12 steps followed in AA to stop drinking, a notoriously hard programme that requires a great deal of commitment: ‘I now realized I twelve-stepped my way out of hatred’ (Meeink & Roy, Citation2017, p. 408).

Continuous self

Although the authors describe a critical moment where their identity was first challenged, reservations about group membership are described throughout group membership. For instance, TJ writes about doubts during a drive-by shooting, concerns in relation to increasing drug use in the group, and worries about an ideology that devalued his invalid mother, who had polio. Johan describes doubts when one of his friends died after a racist attack. Kent had doubts about his group due to members’ drug use and criminal activities. Moments of hesitation are also mentioned in Tony’s book, particularly during and after violent episodes.

Another way the authors present the continuation of a positive identity is by making a distinction between their social identity and a hidden and personal self that was uneasy about the group’s ideology and behaviour. Arno describes continual doubts coming from somewhere deep within: ‘I faintly recall whispers of ‘don’t do this … don’t hurt them … ’ coming from somewhere long ago in my soul’ (Michaelis, Citation2010, p. 29). Tony talks about the rejection of his true self like this:

It went against my humanity and my true nature, suppressing my most sensitive inner self. But by donning the mask over and over, the awkwardness went away, the mask became more and more comfortable and the suppression became more and more automatic. (McAleer, Citation2019, p. 53)

Who was Little Tony? The true, authentic essence of who I was, and who I am today. When I was in the darkest time of my life, I was living contrary to my core essence. As I healed I started living more in alignment with Little Tony, and my life started to improve in magnificent ways. (McAleer, Citation2019, p. 153)

Reinventing the self – theoretical considerations

As previously mentioned, the process of establishing a new social identity after leaving a RW group is a relatively unexplored area of research, but it constitutes a substantial part of the autobiographies. Arguably, the struggle of moving away from a social identity created and reinforced within an ideological group presents particular challenges due to the loss of guiding principles (Bérubé et al., Citation2019). SIT posits that an individual’s social identity is strengthened by intergroup differences (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). For ideological groups such as the RW groups described in this study, negative intergroup comparisons that justify and trigger intergroup conflicts are the very essence of the group’s existence; without an enemy the group has no focus, and membership of the group serves little purpose. Thus, group members’ social identity is dependent on intergroup conflict, based on and continually reinforced by the ideological persuasion that ‘we’ – the in-group – have the right and the obligation to fight ‘them’ – the out-group.

The close connection between social identity and group ideology means that leaving an extremist group requires the rejection of beliefs that have previously bolstered the formers’ sense of self. These difficulties were experienced regardless of the nature of their cognitive openings. For instance, some autobiographies suggest that becoming a father does not make the transition into a new social identity any easier, even though it triggers a significant change in their personal identity. Nor did the formers’ more positive evaluation of what had previously been out-groups contribute to an easy identity transformation. The authors seemed to experience a personal and social identity crisis, which in some cases led to anxiety and depression.

Expressions of doubt prior to the cognitive opener were reported in all the autobiographies and have also been described as the first definable stage of role exits by Ebaugh (Citation1988). These doubts support the narrative of the recovery of a suppressed but moral personal identity as part of the reintegration process. The importance of coherence and directionality in an individual’s narrative structure has been discussed elsewhere (Gergen & Gergen, Citation1988), and identity continuity has also been described as important to crime desistance in ex-convicts (Maruna, Citation2001) and in former political prisoners working in violence prevention initiatives (Joyce & Lynch, Citation2017). The alleged discrepancy between one’s group identity and a suppressed moral self serves to convince the reader that a good self existed and was maintained throughout group membership. In practical terms, the preservation of a positive personal identity throughout group membership provided the formers with a foundation to build on when they began to create a new identity outside the group. This idea of re-engaging a previously held identity is consistent with the Phoenix model, where this process is understood to increase the probability of a successful exit (Silke et al., Citation2021). The autobiographies themselves emphasise the creation of a strong new social identity. Although this could be accomplished in many ways, most of the authors did so by working within the field of P/CVE. This work positioned them at the opposite end of the ideological spectrum while allowing them to establish and maintain status in their new in-group.

Finally, writing and publishing the autobiographies can be understood as a way for the formers to affirm their new social identity. For instance, Ray and Matthew spend a lot of time ‘outing’ the group they were involved with, its members and its connections. These two formers explain the inner workings of the group in detail, whereas the others focus more on their individual journeys. By doing so, Ray and Matthew present themselves as identifying wholly with a different social group. Tony spends a lot of time on psychoeducation and makes sense of his transformation using psychotherapeutic terms. Tom used a sociologist to contextualise his experiences, and Johan’s book is structured as a series of therapy sessions in which he works on understanding what he has been part of and how to move forward with his life. The majority of the authors describe in detail how they work within P/CVE and how they help others move away from violent and extremist groups. The autobiography therefore serves more than one purpose for the author. It functions as a way to meticulously work through their identity, as well as presenting this change to the reader. This revised identification is reinforced in the books’ titles, prefaces/prologues and back-cover descriptions. Ray’s final message to the reader succinctly exemplifies this: ‘At last I could be among those whose commitment to democracy and freedom and tolerance I had come to share’ (Hill & Bell, Citation1988, p. 289).

Conclusion

This article has attempted to answer the research questions: how is identity transformation in the exit process narrated by male former members of RW extremist groups? How can theories of identity contribute to understanding these exit processes? Three themes addressing these questions were identified, based on an analysis of ten autobiographies by former members of extremist RW groups. The first theme described the initial emotional turning point that initiated dissatisfaction with group members’ social identity by moderating the intergroup comparisons. These turning points are often portrayed as very unexpected and represent the start of an exit process in all but two of the books. A result of these turning points can be an increase in positive interactions with the out-group, which further alters intergroup evaluation. The article argues that the term cognitive openings, a concept used in social movement theory, can usefully describe the psychological impact of such turning points.

The second theme, fatherhood, is a particularly strong cognitive opener that alters self-categorisation/personal identity and indirectly influenced the intergroup evaluation in this sample. The authors describe a period when intergroup evaluation consistently favours the out-group, eventually resulting in an unsatisfactory social identity and the decision to leave the group. Although this is often considered the final stage of a group exit, this research reconfirms that group-related difficulties persist long after leaving, and this finding constitutes the third theme. The challenge of forming and maintaining a new social identity was emphasised in all the autobiographies, and the article discusses whether the writing and publishing of the books themselves can be viewed as an exercise in social identity transformation and consolidation.

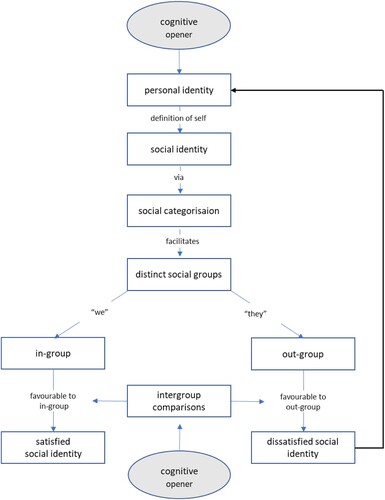

revisits the SIT presented on page 4 and includes additions suggested by the findings in this article: the two cognitive openings discussed in themes one and two, as well as an arrow representing the labour of creating a new social identity after leaving (theme three).

The article is in line with previous findings on the decision to leave extremism behind when it comes to the importance of personal circumstances, ideological doubt (Dalgaard-Nielsen, Citation2013), change in personal priorities (Dalgaard-Nielsen, Citation2018), disillusionment (Dalgaard-Nielsen, Citation2018; Windisch et al., Citation2016), and social interaction with members of the out-group (Windisch et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, the article adds to the knowledge of the field as presented in the Phoenix model by further developing its central element of identity transformation (Silke et al., Citation2021). SIT (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979) helps demonstrate the phenomenon’s complexity and shows that changes can occur in both personal and social identity structures during an exit process. Thus, rather than requiring the re-emergence of an old identity or the creation of a new one, as suggested in Morrison et al.’s (Citation2021) report, a successful reintegration can involve multiple processes in different parts of the identity structure and at different times. The autobiographies described the development of a new self-categorisation resulting in changes to personal identity, a re-engagement of a (suppressed) personal identity, and the creation of a new social identity after leaving as three possible identity transformations that may aid reintegration.

There are limitations to this study. For instance, these autobiographies were written before the emergence of social media; meetings between group members were face-to-face encounters. Information that confirms intergroup conflict and maintains group-related social identity is now so easily available online that one may less readily experience cognitive openings and subsequent interaction with members of the out-group, making an exit from the group even harder. The books portray interpersonal experiences with members of out-groups as a major influence in their exit process, but these encounters may not be available to group members who create their social identity online. Although online CVE programmes are attempting to generate these cognitive openings by providing counter-narratives to vulnerable individuals operating in the online space (Davies et al., Citation2016), little is known about the attitudinal or behavioural impact of these efforts (Helmus & Klein, Citation2018). Conversely, online spaces provide anonymity, which could potentially make an exit easier. Further investigation into identity transformations in exits from extreme online milieus is therefore needed. Finally, although this article focuses on the exit of male RW formers, the theoretical insights offered would be worth exploring in regard to women formers (see Latif et al., Citation2020), other extremist groups, and other sets of autobiographies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hanna Paalgard Munden

Hanna Paalgard Munden is a psychologist and PhD researcher at the Department of Psychology and Center for Research on Extremism (C-REX), University of Oslo. Munden applies theories from social and clinical psychology to help explain some of the processes involved in extremist group participation and exit. These include the development, maintenance and eventual rejection of ideological assumptions, psychosocial dynamics during and after group membership, long-term consequences of group participation, and identity transformations and reintegration of former members of extremist right-wing groups.

References

- Altier, M. B., Horgan, J., & Thoroughgood, C. (2012). In their own words? Methodological considerations in the analysis of terrorist autobiographies. Journal of Strategic Security, 5(4), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.5.4.6

- Altier, M. B., Leonard Boyle, E., & Horgan, J. G. (2021). Returning to the fight: An empirical analysis of terrorist reengagement and recidivism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 33(4), 836–860. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2019.1679781

- Altier, M. B., Leonard Boyle, E., Shortland, N. D., & Horgan, J. G. (2017). Why they leave: An analysis of terrorist disengagement events from eighty-seven autobiographical accounts. Security Studies, 26(2), 305–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2017.1280307

- Altier, M. B., Thoroughgood, C. N., & Horgan, J. G. (2014). Turning away from terrorism: Lessons from psychology, sociology, and criminology. Journal of Peace Research, 51(5), 647–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343314535946

- Barrelle, K. (2015). Pro-integration: Disengagement from and life after extremism. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 7(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2014.988165

- Bérubé, M., Scrivens, R., Venkatesh, V., & Gaudette, T. (2019). Converging patterns in pathways in and out of violent extremism. Perspectives on Terrorism, 13(6), 73–89.

- Bjørgo, T. (2008). Processes of disengagement from violent groups of the extreme right. In T. Bjørgo, & J. Horgan (Eds.), Leaving terrorism behind. Individual and collective disengagement (pp. 30–48). Routledge.

- Bjørgo, T., & Horgan, J. (2009). Leaving terrorism behind. Individual and collective disengagement. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203884751

- Blee, K. (2021, October 12). Researching extremism and radicalisation: In dialogue. Presented at online workshop by DRIVE, Liverpool, England.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brockmeier, J. (2012). Localising oneself: Autobiographical remembering, cultural memory, and the Asian American experience. International Social Science Journal, 62(203/204), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2451.2011.01798.x

- Christensen, T. W. (2019). Former right-wing extremists’ continued struggle for self-transformation after an exit program. Outlines. Critical Practice Studies, 20(1), 04–25. https://doi.org/10.7146/ocps.v20i1.114709

- Collins, M. (2011). Hate: My life in the British far right. Biteback Publishing.

- Cordes, B. (1987). When terrorists do the talking: Reflections on terrorist literature. The Journal of Strategic Studies, 10(4), 150–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402398708437319

- C-REX website: Center for Research on Extremism. https://www.sv.uio.no/c-rex/english/groups/formers/formers_bibliography.html

- Dalgaard-Nielsen, A. (2013). Promoting exit from violent extremism: Themes and approaches. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 36(2), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2013.747073

- Dalgaard-Nielsen, A. (2018). Patterns of disengagement from violent extremism: A stocktaking of current knowledge and implications for counterterrorism. In K. Steiner, & A. Önnerfors (Eds.), Expressions of radicalization (pp. 273–293). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65566-6_10

- Davies, G., Neudecker, C., Ouellet, M., Bouchard, M., & Ducol, B. (2016). Toward a framework understanding of online programs for countering violent extremism. Journal for Deradicalization, 6, 51–86.

- Ebaugh, H. R. F. (1988). Becoming an ex: The process of role exit. University of Chicago Press.

- Egonsson, J. (2012). Ett liv i mörker [A life in the dark]. Forum.

- Eiternes, T. K., & Fangen, K. (2002). Bak nynazismen [Behind the neo-Nazism]. Cappelen Forlag.

- Gergen, K. J., & Gergen, M. M. (1988). Narrative and the self as relationship. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 21, 17–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60223-3

- Giordano, P. C., Cernkovich, S. A., & Rudolph, J. L. (2002). Gender, crime, and desistance: Toward a theory of cognitive transformation. American Journal of Sociology, 107(4), 990–1064. https://doi.org/10.1086/343191

- Hakim, M. A., & Mujahidah, D. R. (2020). Social context, interpersonal network, and identity dynamics: A social psychological case study of terrorist recidivism. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 23(1), 314. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12349

- Hareven, T. K., & Masaoka, K. (1988). Turning points and transitions: Perceptions of the life course. Journal of Family History, 13(1), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/036319908801300117

- Harris, K., Gringart, E., & Drake, D. (2014, December). Understanding the role of social groups in radicalisation. Proceedings of the seventh Australian security and intelligence conference, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Western Australia. https://doi.org/10.4225/75/57a83235c833d

- Helmus, T. C., & Klein, K. (2018). Assessing outcomes of online campaigns countering violent extremism: A case study of the redirect method. Rand Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2813

- Hill, R., & Bell, A. (1988). The other face of terror: Inside Europe’s neo-Nazi network. Grafton Books.

- Hogg, M. A. (2007). Uncertainty—identity theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 69–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)39002-8

- Horgan, J., Altier, M. B., Shortland, N., & Taylor, M. (2017). Walking away: The disengagement and de-radicalization of a violent right-wing extremist. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 9(2), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2016.1156722

- Joyce, C., & Lynch, O. (2017). “Doing peace”: The role of ex-political prisoners in violence prevention initiatives in Northern Ireland. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 40(12), 1072–1090. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2016.1253990

- LaRossa, R. (1997). The modernization of fatherhood: A social and political history. University of Chicago Press.

- Latif, M., Blee, K., DeMichele, M., Simi, P., & Alexander, S. (2020). Why white supremacist women become disillusioned, and why they leave. The Sociological Quarterly, 61(3), 367–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380253.2019.1625733

- Leyden, T. J. (2008). Skinhead confessions: From hate to hope. Cedar Fort.

- Lindahl, K., & Mattson, J. (2000). Exit: Min väg bort från nazismen [Exit: My journey away from Nazism]. Norstedts Forlag AB.

- Marsden, S. V. (2016). Reintegrating extremists: Deradicalisation and desistance. Springer.

- Maruna, S. (2001). Making good. American Psychological Association.

- McAleer, T. (2019). The cure for hate: A former white supremacist’s journey from violent extremism to radical compassion. Arsenal Pulp Press.

- Meeink, F., & Roy, J. M. (2017). Autobiography of a recovering skinhead. Hawthorne Books.

- Michaelis, A. (2010). My life after hate. Authentic Presence Publications.

- Morrison, J. F., Silke, A., Maiberg, H., Slay, C., & Stewart, R. (2021). A systematic review of post-2017 research on disengagement and deradicalisation. Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats. https://crestresearch.ac.uk/download/3797/21-033-02.pdf

- Neumann, P., & Kleinmann, S. (2013). How rigorous is radicalization research? Democracy and Security, 9(4), 360–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/17419166.2013.802984

- Obaidi, M., Kunst, J., Ozer, S., & Kimel, S. Y. (2021). The “Great replacement” conspiracy: How the perceived ousting of Whites can evoke violent extremism and Islamophobia. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(7), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211028293

- Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49(1), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65

- Pettigrew, T. F., Tropp, L. R., Wagner, U., & Christ, O. (2011). Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(3), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001

- Picciolini, C. (2017). White American youth: My descent into America’s most violent hate movement—and how I got out. Hachette Books.

- Rapoport, D. C. (1987). The international world as some terrorists have seen it: A look at a century of memoirs. The Journal of Strategic Studies, 10(4), 32–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402398708437314

- Reinares, F. (2011). Exit from terrorism: A qualitative empirical study on disengagement and deradicalization among members of ETA. Terrorism and Political Violence, 23(5), 780–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2011.613307

- Ross, J. I. (2004). Taking stock of research methods and analysis on oppositional political terrorism. The American Sociologist, 35(2), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02692395

- Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1995). Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press.

- Sandberg, S., Agoff, C., & Fondevila, G. (2020). Stories of the “good father”: The role of fatherhood among incarcerated men in Mexico. Punishment & Society, 24(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474520969822

- Sargar, S. D. (2013). Autobiography as a literary genre. Galaxy. International Multidisciplinary Research Journal, 2, 1–4.

- Schuurman, B. (2020). Research on terrorism, 2007–2016: A review of data, methods, and authorship. Terrorism and Political Violence, 32(5), 1011–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1439023

- Schuurman, B., & Eijkman, Q. (2013). Moving terrorism research forward: The crucial role of primary sources. The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.19165/2013.2.02

- Scrivens, R., Windisch, S., & Simi, P. (2020). Former extremists in radicalization and counter-radicalization research. In D. M. D. Silva, & M. Deflem (Eds.), Radicalization and counter-radicalization (pp. 209–224). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1521-613620200000025012

- Shapiro, J. N., & Siegel, D. A. (2012). Moral hazard, discipline, and the management of terrorist organizations. World Politics, 64(1), 39–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887111000293

- Silke, A. (2018). The study of terrorism and counterterrorism. In A. Silke (Ed.), Routledge handbook of terrorism and counterterrorism (pp. 1–10). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315744636-1

- Silke, A., Morrison, J., Maiberg, H., Slay, C., & Stewart, R. (2021). The Phoenix model of disengagement and deradicalisation from terrorism and violent extremism. Monatsschrift für Kriminologie und Strafrechtsreform, 104(3), 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1515/mks-2021-0128

- Silke, A., & Schmidt-Petersen, J. (2017). The golden age? What the 100 most cited articles in terrorism studies tell us. Terrorism and Political Violence, 29(4), 692–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2015.1064397

- Simi, P., Blee, K., DeMichele, M., & Windisch, S. (2017). Addicted to hate: Identity residual among former white supremacists. American Sociological Review, 82(6), 1167–1187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122417728719

- Simi, P., Futrell, R., & Bubolz, B. F. (2016). Parenting as activism: Identity alignment and activist persistence in the white power movement. The Sociological Quarterly, 57(3), 491–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/tsq.12144

- Syafiq, M. (2019). Deradicalisation and disengagement from terrorism and threat to identity: An analysis of former jihadist prisoners’ accounts. Psychology and Developing Societies, 31(2), 227–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971333619863169

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–37). Brooks/Cole.

- Turner, E. (2017). ‘I want to be a dad to him, I don’t just want to be someone he comes and sees in prison’: Fatherhood’s potential for desistance. In E. Hart, & E. van Ginneken (Eds.), New perspectives on desistance (pp. 37–59). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95185-7_3

- Turner, J. C. (1975). Social comparison and social identity: Some prospects for intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 5(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420050102

- Turner, J. C. (1978). Social categorization and social discrimination in the minimal group paradigm. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 235–250). Academic Press.

- Turner, J. C. (1982). Towards a cognitive redefinition of the social group. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Social identity and intergroup relations (pp. 15–40). Cambridge University Press.

- Turner, J. C. (1988). Comments on Doise’s “Individual and social identities in intergroup relations”. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18(2), 113–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420180203

- Turner, J. C., & Oakes, P. J. (1986). The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence. British Journal of Social Psychology, 25(3), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1986.tb00732.x

- Turner, J. C., Oakes, P. J., Haslam, S. A., & McGarty, C. (1992, May 7–10). Personal and social identity: Self and social context [Paper presentation]. The Self and the Collective, Princeton, NJ, USA.

- Turner, J. C., Oakes, P. J., Haslam, S. A., & Mcgarty, C. (1994). Self and collective: Cognition and social context. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 454–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205002

- Turner, J. C., & Reynolds, K. J. (2001). The social identity perspective in intergroup relations: Theories, themes, and controversies. In R. Brown, & S. Gaertner (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology. Intergroup processes (Vol. 4, pp. 133–152). Blackwell.

- Turner, J. C., & Reynolds, K. J. (2010). The story of social identity. In T. Postmes, & N. R. Brandscombe (Eds.), Rediscovering social identity: Key readings (pp. 13–32). Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis.

- Wiktorowicz, Q. (2004, May 8–9). Joining the cause: Al-Muhajiroun and radical Islam [Paper presentation]. Roots of Islamic Radicalism conference, Cambridge, MA, USA.

- Windisch, S., Simi, P., Ligon, G. S., & McNeel, H. (2016). Disengagement from ideologically-based and violent organizations: A systematic review of the literature. Journal for Deradicalization, 9, 1–38.