ABSTRACT

The future of the Nordic model of welfare has been widely debated in the academic literature. Some argue that the Nordic model is not sustainable under the conditions of globalization, while others argue that the way in which the Nordic model has produced long-term stability under uncertain structural conditions is evidence of the opposite. This article advances a different perspective through analyzing discourses and frameworks of meaning associated with the Nordic model, using Sweden and Finland as cases. Based on semi-structured elite interviews, I argue that while there is a consensus on the benefits of maintaining a Nordic model, the very ideas concerning the value foundations and institutional architecture of the model differ greatly between elites. There exists a variety of legitimate ideas associated with the Nordic model and, consequently, these approaches, all of which claim ownership of the term, represent legitimate facets of it, even when they initially would seem to contradict each other.

Introduction

A vast literature exists on ‘the Nordic model’ of welfare. Scholarly contributions, such as Esping-Andersen’s Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (Citation1990), have contributed toward the Nordic model being discussed widely as a distinctive approach to welfare politics. The label ‘social democratic’ has also been frequently attached to it and Sweden in particular has been considered as the emblematic Nordic case. Outside of the academic debate, political parties have also literally fought over the Nordic model. After the Swedish center-right government made an ownership claim toward the concept, social democrats swiftly reacted and applied for a patent for it (Edling, Petersen, and Petersen Citation2014, 28–29). The oscillating meanings of the Nordic model certainly demonstrate that, despite some claiming that it is an essentially social democratic concept, it is common property and a powerful symbol of national identity (Béland and Lecours Citation2008, 208; Kuisma Citation2007a). Social policy can become an expression of national identity, as social policy preferences are often discussed in terms of values that inform both economic principles and political ideologies and define the national project (Béland and Lecours Citation2008, 197).

After years of crises and challenges, it has been often asked what is left of the Nordic model and to what extent it can be sustained in the future. Cox (Citation2004) suggests that the future shape of the Nordic model and the impact of austerity on it is possibly an irreconcilable argument, yet there is evidence to suggest that the very idea of the Nordic model is sticky. Indeed, the spat over conceptual ownership between the Swedish parties is evidence of it. This article builds on Cox’s perspective by analyzing ideational representations of the Nordic model, using Sweden and Finland as cases. Therefore, instead of offering yet another evaluation of the future prospects of the Nordic model as something that exists ‘out there’ (Ryner Citation2007, 62), the term is used here as a heuristic device and its meanings are explored through language and discourse.Footnote1 Rather than a concrete policy program, it is the central ideas associated with the Nordic model – communicated through language and discourse – that are then shaped and recast against ideas of what are understood as structural challenges, such as globalization, demographic change and global financial crisis (see also Kuisma Citation2013). Discourse analysis can help us understand the central cognitive filters ‘through which actors interpret the strategic environment’ (Hay Citation2002, 214) and which inform their preferences and decisions for political practice.

The article is based on qualitative data consisting of semi-structured interviews with social and political elites in Finland and Sweden. The data are used in an attempt to analyze the ideational representations of the Nordic model in elite discourses. While most participants interviewed were reticent to talk about one concrete policy model, many of them considered the ideas and institutions around the Nordic welfare states as particular in comparison to other countries and regions, and they considered it legitimate to use the term. While differing from each other, the views and accounts of elites form legitimate yet competing narratives of the core principles and characteristics of the Nordic model and, as such, challenge the ideal-typical representation as an internally coherent and predominantly (Swedish) social democratic political project. Based on the qualitative data presented here, I argue that there are a variety of ideational representations of the Nordic model of welfare in Sweden and Finland. These range from the obvious national variations to intra-national interpretations and, while they might differ significantly in their logics of appropriateness, they all are equally legitimate narratives of the Nordic model.

The article proceeds in three stages. First, I will provide a critical overview of the existing debate on the future of the Nordic model. In the literature, the current trends and developments are evaluated against an ideal-typical representation of a Nordic model that belongs to a ‘golden age’ of the welfare state (Wincott Citation2003, Citation2013). Hence, the estimates of its future viability are dependent on the core characteristics of that golden age model and it seems like there is no exact consensus on what its core components actually are. Contrary to the ideal-typical construction of it, it has many facets and it serves many purposes. The second section begins with the analysis of the data, where the initial results are presented through a qualitative content analysis in an attempt to summarize the data. The third and most substantial section concentrates on analyzing the frameworks of meaning related to the Nordic model, using Sweden and Finland as cases.

Method and case selection

This article is built on a ‘paired comparison’ (Tarrow Citation2010) of two country cases, namely Finland and Sweden. In the literature on the Nordic model, Sweden has often been treated as an emblematic ‘social democratic welfare regime’ (Esping-Andersen Citation1990). This can be seen in the terminology as well, as the Swedish and Nordic model are often discussed almost interchangeably. Indeed, as mentioned above, the conceptual overlap between the Swedish and the Nordic model has made it possible for Swedish political parties to fight over the ownership of ‘the Nordic model’. Finland, on the other hand, is the most understudied Nordic case, a late developer that caught up on its Nordic neighbors arguably only in the 1970s (Kettunen Citation2001). A comparison of Finland and Sweden could be considered as a ‘most different’ Nordic comparison, since it is in Sweden where social democracy has been the most hegemonic and Finland where it has traditionally been the weakest (Kuisma and Ryner Citation2012, 326).

In order to analyze ideational representations of welfare, I conducted semi-structured elite interviews. My approach is based on a phenomenological approach to life world interviews (Kvale Citation2007, 51–52), related to Giddensian double hermeneutics, concerned with understanding the national frameworks of meanings and narrative constituted and reconstructed by the elites (Giddens Citation1976, 79). The terminology, metaphors and concepts that are used are not mere tools of communication but are ‘closely tied to political struggles and international exchanges’ (Béland and Petersen Citation2014, 1). The emergence of (what are presented as) new cognitive filters and the discursive construction of these into structural challenges with real consequences, such as globalization, are a part of these struggles and exchanges. Through interviews, we can then explore the ‘repertoire of legitimate stories’ (Czarniawska Citation2004, 5; Silverman Citation2006, 145), in this case, in reference to the Nordic model(s). This is because in an interview, the participant engages in ‘discourse’ and gives ‘accounts’, which represent a culturally available way of packaging experience (Kitzinger Citation2004, 128, cited in Silverman Citation2006, 129). This is significant, ‘because one may assume that it is the same perception that informs their actions’ (Czarniawska Citation2004, 49). As such, these perceptions and accounts are ideational reflections of ‘reality’ and they also shape it, as the narratives will also reflect institutions and influence the direction of policy.

The initial analysis of data is based on qualitative content analysis on transcripts of 26 semi-structured elite interviews (13 participants in both Sweden and Finland). The participants were selected through ‘selective sampling’ (Schatzman and Strauss Citation1973) and included representatives of political parties, trade unions, business organizations and civil society organizations (CSO) ().Footnote2 This follows a criterion based or purposive sampling of participants driven on the key research questions, and where the aim is to put together a heterogeneous sample of elites involved in issues relevant to the welfare state (Ritchie, Lewis, and Elam Citation2003). The qualitative data consist of interviews with a relatively wide set of actors in order to appreciate the complexity of the elite discourse on welfare also beyond party politics. This is particularly relevant in the Nordic context where, as was noted already by Childs (Citation1936), civil society actors and organizations have tended to be close to the state and also its legislative and policy-making functions, a feature that is not entirely uncontroversial for all commentators (Trägårdh Citation2007).

Table 1. Interview matrix.

Like in most qualitative research, the sample is not representative of the whole population or all elites, and the aim is not to produce generalizable outcomes, Rather, the aim is to offer a way into exploring and problematizing some key aspects of the discourse through having access to accounts based on personal views and lived experiences of the participants in the spirit of the phenomenological approach to the life world interview. This also contributes toward the development and operationalization of the ideational institutionalist approach.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in order to guarantee not only comparability across the data but also to allow for flexibility in the process and for the interviewer to enter in a dialog with the interviewee (May Citation2001, 123). The material was collected in 2009 and it is a snapshot of particular elite discourses at the time. I am not arguing that this set of ideas on the welfare state in the two countries is conclusive and complete. It is far from it. However, what I argue is that the data presented here provide us with an example of the oscillating quality of the Nordic model and show how it can be approached from different perspectives and appropriated for a variation of purposes. Other participants at another time might provide the same and/or other interpretations.

Rather than coding raw interview data, I conducted ‘directed content analysis’ where the categories of coding are predetermined driven by the main research questions (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005).

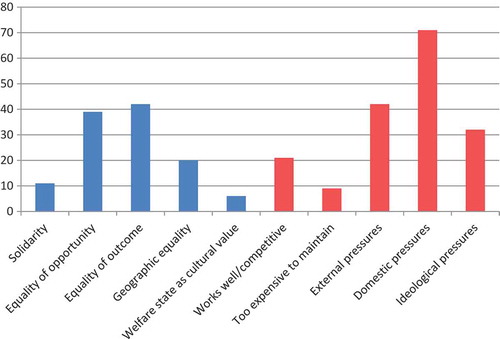

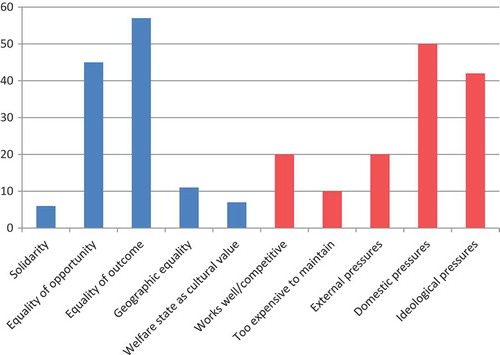

In order to analyze the public philosophy dimension of ideas (Mehta Citation2010), I coded for statements relating to ideas on solidarity, equality of opportunity, equality of income/outcome, geographical equality and welfare as a historical/traditional idea. Within the ideas related to problem definitions, statements relating to the ideas of specific problems and challenges faced by the welfare state were coded. These included domestic and structural challenges, challenges external to the nation-state and ideological challenges. I also coded for statements relating to the absence of specific problems, in other words, statements that claimed that the welfare state has been successful, is able to adapt, can be reformed and so on. The content analysis is by no means exhaustive and is primarily aimed at illustrating the qualitative data in its entirety in order to provide a starting point for the more detailed analysis of the interview material, as a way of combining qualitative content analysis and discourse analysis (Schreier Citation2012).

Ideational institutionalism and Nordic welfare futures

The Nordic model of welfare is more complex than the ideal-typical model discussed in much of the literature. However, some of its core features can be defined. In a nutshell, the Nordic countries have developed an approach to welfare politics where the state, market and society have been able to produce a political–institutional configuration with a capacity to produce high economic efficiency together with high levels of equality (Einhorn and Logue Citation2003). More specifically, the Nordic welfare states are seen to be characterized by a large and expensive public sector, tax-financed welfare benefits and services organized according to universal principles, strong position of women and an autonomous labor market working in a smooth relationship with the state (Christiansen and Markkola Citation2006, 11–12; Kuisma Citation2007b, 11–13). Esping-Andersen (Citation1990) concluded that in international comparison, these were the most ‘de-commodified’ welfare states, i.e. that the principles of access rested, more than in other countries, on rights rather than status or contributions. Furthermore, as I argue below, one of the features of the Nordic model is also that it exists at the level of ideas and that there is no single idea or dominant discourse that would represent what the Nordic model is (see also Kuisma and Nygård Citation2015).

While we should be careful of epochalism in welfare state research (Wincott Citation2013), many make the argument that after the ‘golden age’, or the ‘third phase’ of Nordic welfare state history, from the 1950s to the 1980s (Christiansen and Markkola Citation2006, 21), the Nordic countries faced new challenges, ranging from political and ideological shifts to European and global challenges. In the light of these challenges, there certainly seems to be a considerable disagreement on the current state and future prospects of the Nordic model. Indeed, the debate is characterized by the coexistence of two incommensurable trajectories for Nordic welfare states.

Some authors have concluded that the Nordic model must necessarily bow to the neoliberalizing tendencies of globalization (Scharpf Citation1991; Kitschelt Citation1994; Iversen Citation1999). According to this argument, the realities of the global economy are such that a universal welfare state funded through heavy taxation cannot survive and that the age of a social democratic welfare state is well and truly over. However, others have argued, pointing at inter alia the remarkably strong Nordic economic recovery following the 1990s recession, that the Nordic model could yet again be celebrated as a potentially viable alternative in generally neoliberal times (Geyer Citation2003; Steinmo Citation2003; Pontusson Citation2011; Einhorn and Logue Citation2010). The Nordic welfare states in the late 1990s and early 2000s are considered as a success story of institutional adaptation, introduction of new industries and more centrist social democratic politics compatible with economic globalization. In all this, the welfare state has played a direct role by producing a highly educated and skilled population able to adapt to these changes (Iversen and Stephens Citation2008, 609). So, the story of an anti-market ‘golden age’ Nordic model becoming, at most, a post-industrial neoliberalism with a human face is also an exaggeration, as social democracy itself has proven to be capable of adapting to a changing political and economic environment (Hinnfors Citation2006, 208–209; Béland and Lecours Citation2008).

Both of these sides of the argument are plausible. However, at the same time, both of them struggle to conclusively explain what is actually going on and why. On one hand, the Nordic model is treated as an ideal-typical utopian dream but as one that is still able to adapt to the challenges of its time in order to remain close to its true values. On the other hand, it is seen as an antiquated model out of touch with twenty-first century reality. To provide a new perspective to the debate on the future of the Nordic model, I argue that we also need to look at the role of ideas and welfare discourses in order to appreciate the relevant ideational frameworks that both reflect the institutional practices and inform the processes through which they are reformed. This can offer an insight into the sociology of political and economic institutions by understanding the cognitive filters (Hay Citation2002) that inform much of the debates and the strategic choices of political actors. Here, there are apparent links between the social policy realities of the model and its existence as a national symbol (Béland and Lecours Citation2008). This might not come as a total surprise, as it has been argued widely that centralized systems of authority, such as the ones in the Nordic region, have put much effort in the construction of national identity (Goodman and Peng Citation1996).

In comparative politics and political economy, a rich literature on the role of ideas has emerged (see e.g. Berman Citation1998; Blyth Citation2002; Schmidt Citation2002b; Hay Citation2004; Béland Citation2010; Béland and Cox Citation2010). Much of this literature makes a strong link between ideas and political agency. Blyth (Citation2002, 39–40, 258–259) argues that ideas can be used as political ‘weapons’. He suggests that in a particular crisis situation the institutions that are seen as part of the problem need to be delegitimized by contesting the very ideas that underlie them (39). This is partly what happened in the Nordic countries during the 1990s recession, and it has been argued by some (see Ryner Citation2002) that certain core economic ideas associated with the traditional social democratic welfare model were recast during the 1990s and that rather significant policy change followed this ideational shift. This implies that ideas are used strategically and that political actors are actively able to use them as means to an end. Social policy is one of the policy areas through which governments can reach to the everyday lived experiences of citizens and, as such, it can be used powerfully as a part of political strategy (Béland and Lecours Citation2008, 200). While politicians can deliberately use social policy ideas as strategic weapons, ideas are also anchored in institutions, expressed through what could be described as ‘collective memories’ (Rothstein Citation2005) and the available ‘repertoires of legitimate stories’ (Czarniawska Citation2004, 5).

Importantly, though, these ‘legitimate stories’ refer as much to the set of values and policy preferences that are the target of reform as they do to the reasons for why the reforms are necessary. As such, instead of looking at the concrete ‘realities’ of the challenges faced by an ideal-typical Nordic model, or the policy responses to it, I want to discuss and problematize the key ideas associated with the Nordic model, and how elites understand and appropriate them in particular ideational circumstances. From the ideational perspective, it is crucially important to remember that the pressures against which the future of the Nordic model is evaluated are also ideational and they are shaped and communicated through discourse. It is not even important for us to know if the external pressures, such as globalization, are real or not. The way elites understand globalization is at least as important (Hay and Smith Citation2010, 903). ‘For the sad irony is that if governments believe the [neo-liberal convergence] thesis to be true (or, indeed, find it in their interests to present it as true) they will act in a manner consistent with its predictions’ (Hay Citation2006, 5). Following Schmidt, I argue that while some research is now emerging on it, discourse is, also in the Nordic cases, ‘the missing element in the explanation of policy change in the welfare state’ (Schmidt Citation2002a, 169). At least we can understand how discourse shapes the politics of welfare. As such, this article is a contribution toward the emerging ideational and discursive institutionalist literature.

Ideational representations of welfare

The qualitative data gathered through the semi-structured elite interviews were coded for statements pertaining to ideas and values associated to the welfare state and these were initially divided into two main categories following Mehta’s (Citation2010) categorization. These are, first, ideas as public philosophy and, second, ideas as problem definitions. Public philosophies are ideas that cut across specific areas. They are fundamental ideas that help to understand the purpose of government policy in light of core assumptions about the society and the market (Heclo Citation1986, cited in Mehta Citation2010, 27). Various approaches on equality and social justice could be seen as such ideas. Ideas as problem definitions, on the other hand, are particular ways of making sense of complex reality and causal relationships between phenomena. It is about explaining what is going wrong in society and why (Mehta Citation2010, 27). For instance, structural unemployment could be seen to arise from globalization and failure of the industries to be cost competitive, lack of incentives for the unemployed to get from welfare to work, an education sector not fit for purpose and so on. Some of the interviewees also discussed areas relevant to Mehta’s third category of ideas as policy solutions but, as the main focus of the article is on making sense of the ideational representations of the Nordic model(s) in elite discourses, the detailed policy discussions were deliberately left out. It is also the first two levels of ideas that form the ‘legitimate narratives’ relevant to my aims here. In total, the interview transcripts contained 642 statements on welfare that fell into the two categories of ideas.

When comparing the balance of claims relating to ideas either as public philosophy or problem definitions among the Finnish participants, there is a slight emphasis on the latter (). In other words, the Finnish participants understood and discussed the welfare state often through its (perceived) failures or challenges. While the literature points at external pressures and challenges, the Finnish participants tended to talk more about domestic structural challenges, such as the ability of municipalities to provide welfare services, the administrative and bureaucratic failures at both central and local level, challenges associated with demographic shifts and structural unemployment. Even where it would have been possible to explicitly link these developments to ongoing external phenomena, participants rarely took the opportunity to do so. External pressures such as conditions of economic competitiveness under globalization and the increasing pressures from the EU were mentioned but they were often either secondary or taken as given and, as such, not the prime targets for a detailed critique. With regard to the politically and ideologically driven pressures and problems associated with the welfare state, one of the key issues was increasing privatization and withdrawal of government responsibility in providing welfare for all, which was seen as a predominantly negative development by most participants.

At the level of ideas as public philosophy, the participants made statements about equality of outcome and equality of opportunity and many participants spoke of both interchangeably. However, this was not internally contradictory, as often the ideals of equality of outcome were linked to provision and availability of welfare services and equality of opportunity more to the way in which welfare benefits are distributed and administered. Perhaps characteristically to the Nordic countries, geographic equality was also mentioned as an important theme throughout the interviews. There is a strong normative desire to ensure that the urban concentrations in the south of the country and the rural areas to the east and north are not treated differentially in terms of welfare services and benefits. Here, the spirit of the 1930s cross-class compromise as the cornerstone of the Nordic model (Alestalo and Kuhnle Citation1987) is still very much alive.

Among the Swedish participants (), the ideas on equality feature more prominently than in Finland. The Swedish discourse seems to be more politically and ideologically driven and less pragmatic in this sense. Again, claims on both equality of outcome and equality of opportunity feature. However, as opposed to Finland, in Sweden, the statements relate less to the importance of equality of access to services across the country and more to abstract understandings of equality of status and socioeconomic inequalities. Many participants thought that increasing income inequality was going against the Swedish model. While these statements could also be seen to relate to ideas as problem definitions, I understood them to be value statements on what the Swedish model stands for and what its core elements are at a level of ideas as public philosophy.

On ideas as problem definitions, there is a strong sense of political and ideological challenges. Similarly to the Finnish experience, many participants’ very definition of the Swedish model is determined through the problems and challenges it faces. However, the ideas of domestic and structural challenges are also a prominent feature of the Swedish discourse. Here, the ideas referred to the administration of welfare services and benefits, issues related to unemployment and making work pay, demographic shifts and also municipal finances. External pressures in the Swedish discourse seem to play a lesser role than in Finland. This is possibly just a consequence of heavier emphasis being placed on domestic political and ideological debates and the increasing left–right polarization, which has been accentuated by the emerging bloc politics during the last couple of elections.

The repertoire of legitimate stories on welfare

The following sections will discuss the data in more detail and will get deeper at exploring the ideational representations and the ‘repertoire of legitimate stories’ (Czarniawska Citation2004, 5) emerging through the ideas represented in the interviews. These are divided, for analytical purposes, as discussed above, primarily into two categories, ideas as public philosophy and ideas as problem definitions (Mehta Citation2010). and summarize the key themes from the qualitative data.

Table 2. Theme summary of Finnish welfare discourses.

Table 3. Theme summary of Swedish welfare discourses.

Ideas as public philosophy

When the content analysis is broken down, it is possible to see clearer differences between the participants. However, it is difficult to see very strong polarization along traditional left–right partisan lines, even on ideas related to equality. In Finland, the participants from CSO were the most prominent supporters of equality of outcome:

A Finnish citizen or Finnish resident, regardless of where they live and what their background is, has equal right to services … and our constitution guarantees it. (Interview 26)

There is a sense that despite a wide agreement upon the value of equal access to welfare, this has slowly been given up. Here, statements expressing concern for increasing income inequality are understood to represent support for equality of outcome. For the political left, this was slightly more salient than equality of opportunity. However, participants from center-right political parties and the employer organization represented the clearest emphasis on equality of opportunity.

…I definitely think that this system where the basic idea is equality of opportunity is good but then there should also be an incentive element involved because otherwise the system won’t work… (Interview 19)

Participants often linked equality of opportunity to incentives and the idea of ‘no rights without responsibilities’, a neoliberal theme that had been a popular Third Way mantra in the 1990s (Kuisma and Ryner Citation2012, 330). This was partly linked to employment as a responsibility and the increasing popularity of the idea that ‘work is best social security’ (Interview 25). The category of statements relating to equality of opportunity also includes statements in support of increased means-testing, activation, responsibilization and making work pay. The argument here often is that the welfare system needs people to get from welfare to work or otherwise it will become too expensive to maintain. The deserving/non-deserving poor dichotomy is, therefore, also becoming prominent in the Finnish context. Interestingly, this perspective sits rather comfortably with protestant work ethic and the sense of individual responsibility historically significant to the development of the Nordic model (Kettunen and Petersen Citation2010, 6).

…we can look after the interests of the poor but someone who is lazy and poor doesn’t deserve anything. So, if you are lazy, you won’t be supported, we don’t want to support you… (Interview 25)

…I think that one value that has been shared between employers and the union movement has been the view that social security needs to be earned through work… (Interview 15)

These are related mainly to welfare benefits. However, with regard to equality of outcome, even the center-right political elites supported equal access to welfare services and did not openly advocate a dualization of social and health services. Here, the statements on equality of opportunity actually overlap with the statements on geographic equality.

[E]veryone regardless of where they live, how much they earn and how wealthy they are … are offered similar services in the health sector, social services and schooling and [we have], or at least it has been often emphasized, a principle of geographic equality that arises from Finnish political history… (Interview 24)

Trade union representatives emphasized the ideas as public philosophy less and were more concerned about problems and challenges. One participant defined the challenges faced by the welfare state:

…the two main trends during the last 15–20 years … have been globalization, in other words the ease at which production relocates … and the second is Finland’s position within the EU. In a way, the question could be simplified so that two issues determine Finland’s position: EU’s place in the world and Finland’s place in the EU. (Interview 14)

Quite typically for the sector they represent, trade union representatives linked the future of the welfare state to challenges facing the Finnish labor market. Questions related to production are, of course, very important, especially as the labor market actors share a view that emphasizes the importance of earnings-related aspects of the welfare state.

In Sweden, the picture is slightly different. The debate on ideas as public philosophy is more polarized between left and right, unions and employers. Representatives of the political left talked about equality more in terms of equality of outcome and defended universalism. However, no one talks exclusively about one or the other. Rather than a clear division, there is a difference of emphasis.

[E]veryone has the possibility to receive welfare services and they are offered to everyone regardless of the thickness of one’s wallet… (Interview 3)

[U]niversal social programs, rather than income-related [programs] or [ones] specific for groups, is the first element … But [there are] also income-related benefits, income-replacement policies in terms of social insurance, which go high enough in the income ladders so that large majority of the population are covered by income-replacement programs and [the] third element … [is] the policy, which gives support to dual earner families… (Interview 6)

However, the political right sits more on the liberal end of the value spectrum, arguing for equality of opportunity, means testing and taking care of the poorest instead of being concerned about income inequalities. In addition, while the left might still be concerned about the generosity of benefits or the scope of public services, the center-right emphasizes quality of services and the right to individual choice. After saying that the priorities lie in universal services, a participant added:

[T]he second part is that the services should be of high quality, in terms of medical quality if you are talking about healthcare, but also cost efficient… (Interview 11)

Quality is often linked to freedom of the individual to choose the social and health services and to ‘shop around’:

[W]e have this idea that you should have the possibility as an individual to make your choice, not being forced to pick the one provider that exists on the market. It’s like … buying a car. (Interview 7)

Despite these differences of emphasis, even when explicitly asked, all participants took the idea of a Nordic/Swedish/Finnish model of welfare as their starting point or frame of reference. No one questioned the idea of the Nordic model as such. Even the center-right was keen to defend (the idea of) the Nordic welfare model. In fact, they often claim that the big differences between them and the social democrats are not in the value foundations of politics, or even in the way in which they understand the key problems or challenges, but rather in the policy solutions (Interview 11). In fact, one participant blamed the social democrats for betraying the Swedish model.

The core is that we have had systems that have thrown people into passivity and long-term dependence on social insurance. It has not stimulated activity and therefore as a result we have had a huge problem with people getting on disability benefits and never being able to re-enter the labor market. We have, for example, 550,000 disability pensioners of whom less than one per cent will get back to the labor market. That’s the core issue: encouraging activity and discontinuing passive insurance systems. (Interview 7)

Here, the problem is not seen to be the welfare state itself. Rather, the argument goes that it has gone too far in providing rights-based universal benefits and not creating enough incentives for people to return to work.

As such, while the Swedish debate is more ideologically driven than the more pragmatic Finnish elite discourse, the data clearly support Cox’ (Citation2004) idea about the resilience of the idea of the Nordic model. The Nordic model means many things for many people and many different public philosophies coexist within it. This is perhaps not too surprising provided that the Nordic model was founded upon a tripolar class structure based on a broad and wide cross-class compromise (Alestalo and Kuhnle Citation1987). Even the Swedish social democrats based their politics on becoming a party for the people, on what Hjalmar Branting called a ‘big tent approach’ (Berman Citation2006, 157). As such, the partisan social democratic elements of the Swedish welfare state may have been exaggerated, as the model is, and always was, based on a broader set of values and ideas appropriated for the use of parties of different ideological convictions.

Ideas as problem definitions

However, beneath the solid yet diverse foundations of the Nordic model, the participants identify a range of problems and challenges. Here, there is much less disagreement across the board and despite the relatively strong emphasis on external challenges in the academic literature, the elites seem to be mostly concerned about domestic problems and challenges.

In Finland, ideas as problem definitions are predominantly seen to be of domestic (structural) origin. One key issue is the change of legislation in 1992 when central government control of municipal welfare spending was removed and municipalities were given more autonomy. This led to a widening gap between well-performing municipalities and those in genuine financial difficulties unable to provide services to their citizens.

This led municipalities controlled by bourgeois parties to use the funds differently to social democratic municipalities and then when we had the severe recession the municipalities … were in rather deep trouble because they had to decide themselves how to prioritize money that had run out everywhere… (Interview 17)

In other words, this development scrutinizes the very principle of geographic equality as citizens get different level of access and quality of services depending on where they live. This has also led to a purchaser–provider model for welfare services, which represents a departure from the old system by introducing more market-based principles. It also scrutinizes the old parameters of responsibility and passes the buck from the state to the individual (Julkunen Citation2006).

Another domestic structural problem is associated with demographics:

[W]e did not foresee the economic crisis but we did know about the ageing of the population. We have known it for 30 years already, we have talked about it for five to ten years … We do not have to do anything else but look at the annual birth data and we can see how large the bill will be. (Interview 14)

There seems to be consensus among the elites about demographic change as a key challenge. The solutions, however, are not entirely agreed upon, apart from maybe the desire to increase level of employment and the average career lengths.

Ideas relating to problems arising from the external environment are also prominent in the discourses. These include the possible constraints arising from the EU on taxation and public spending and the impact of global competition on jobs and investment. Here, the elites have bought into the neoliberal convergence thesis (Hay Citation2006) and, for instance, seem to accept that production costs in Finland are too high and that companies will relocate abroad to pay less taxes and find cheaper labor. Apparently, even those companies who once were loyal cannot remain so anymore.

[They] will be forced to do [relocate]. The ownership is in foreign hands, as they are listed companies … [T]he CEO favoring Finland for some patriotic reasons without sound economic justifications won’t be tolerated for long. (Interview 24)

This narrative is remarkable, as it openly gives the bargaining tools away from the state or even a veto to the big companies. The so-called Lex Nokia controversy in Finland is a case in point (Sajari Citation2009). To contrast this, some mention an argument related to the Varieties of Capitalism approach (Hall and Soskice Citation2001) on comparative advantage arising from a highly skilled workforce and innovative society.

[H]igh levels of taxation did not prevent Finland from being competitive because public sector investment was used for innovation, education… R&D was one of the means by which Finland was lifted up from the recession of the 1990s … and then we had the IT boom and things like that. (Interview 17)

The only aspect of ideas as problem definitions where the old left–right divide becomes apparent relates to political pressures. While they are not significant concerns in Finland, there are some, especially on the political left, who suggest that the center-right’s thinking represents a break from the past and that the drive for reforms is ideologically driven.

[T]he values represented by the political right emphasize that entrepreneurialism needs to be rewarded more and this has been demonstrated in the gradual changes made in taxation during the last 20 years that benefit those with higher incomes. (Interview 14)

I think that in the past there was more of a consensus on equity. I find it alarming that when I talk about increasing income inequalities there are some who say ‘so what?’. (Interview 26)

In Sweden, the ideas at the level of problem definitions are often also expressed in terms of structural problems of domestic origin traced back to the 1990s crisis. Welfare cuts and privatization are seen as a break with the past and the political left and the trade unions are especially critical of it.

[I]n … the crisis during the 1990s we saw a greater part of privatization of previously public driven services, more and more of the state services were privatized into some kind of joint venture of companies … but also within the educational system there was a huge privatization process. (Interview 5)

One participant claimed that the withdrawal of state responsibility is a sign of Sweden completely abandoning its welfare model:

In the 1990s crisis we made the same mistake. The state did not help out the municipalities and regional government. Local and regional government fired teachers and school health personnel … and now they do the same, as many municipalities already have so serious budget deficits that they have given warnings of teachers being sacked and schools closed. (Interview 3)

Here, it is clear that the withdrawal of state responsibility and the introduction of privatization are generating inequalities between municipalities and that goes against the principle of geographic equality. Indeed, while some do appreciate that some of the 1990s’ retrenchment was done in good faith – they genuinely believed that there were no alternatives (Interviews 2 and 6) – many of the ideas as problem definitions are firmly grounded in ideological debates and normative disagreements between left and right. For example, the left does not raise dependency culture as an issue but concentrate more on socioeconomic equality rather than equality of opportunity. The center-right claims that the welfare state in its current form promotes passivity and that the only way to maintain the system is if people got back to work. Being off sick should not be seen as a ‘right’ of the individual anymore and the gatekeeper functions of the system should be strengthened (Interview 12).

[W]e … have a shortage of working age population, we have an aging society and we must make people return to work, otherwise we cannot afford to keep up the welfare state, healthcare, daycare … schools … So, everyone that has a capacity to work should get the support to get back to the labor market. (Interview 7)

The center-left does not disagree entirely but there is a difference of emphasis. The center-right government sees dependency culture as the core issue whereas the voices from the left-green bloc suggest that more could be done to give people opportunities instead of forcing them to return to work. The difference might be as simple as the one between the proverbial stick and carrot.

As such, the problems identified by the center-right are seen as an ideological attack on the welfare state by some voices from the political left.

Today, there is much more of an ideological threat against the welfare state from the right of center parties and not the same division with the social democratic party at that time but not a strong ideological counter-position, I would say. (Interview 6)

Ideological differences do certainly exist but they are downplayed in the discourse. One participant said that there are ‘small ideological differences’ between the blocs.

They say that they like competition and saw competition as something positive, but they couldn’t [introduce] proper competition between providers … [W]e say that we have no problems at all with private providers. Actually, we see private providers as something necessary in order to reach our goals for healthcare. (Interview 11)

On balance, portraying opposing views on privatization of health care as ‘small ideological differences’ is rather flawed. However, as was pointed out, the privatization push began already during the Persson government and this is an example of where the center-right has abused the opportunities arising from the failures of ‘The Third Way’ (Kuisma and Ryner Citation2012). The possibilities for the left in launching a counter-argument were slim, as the principles introduced by the center-right government were not the antithesis of those of the previous social democratic administration and any critique of them could be considered as a self-contradiction.

While especially the political parties seem to have a more vibrant debate at the level of ideas, some suggest that outcomes also do matter. So, even if a vast majority of the elites advocate the ideas of equality and solidarity, they do not mean much if welfare outcomes are shifting.

We try to be so much better than others … We try to be something else but we are a part of Europe and we are part of … globalization … [I]t’s ok to have homeless people because they have it [them] in England and the US… (Interview 13)

This could be called ‘welfare state nostalgia’ (Andersson Citation2009). There is a very strong set of public narratives and collective memories of Swedish exceptionalism and even when there is change that makes Sweden less exceptional, it is difficult to change the legitimate stories of what Sweden is about and what it stands for. The welfare state is taken for granted:

I think [the Swedish welfare state] will survive … because … I think we are used to it. (Interview 4)

Indeed, the power of historical path dependencies is acknowledged, whether in good or bad. As one participant said about the possibilities of policy transfer and learning:

But countries don’t change [just] like that, probably for good reasons. And hence we will be stuck with the system that we have in Sweden for, probably, forever. (Interview 11)

Therefore, even if current actors do not share the values of the traditional golden age social democratic Nordic model or believe that they can be honored in the current circumstances, it is a strategically wise decision to package their policies with a public philosophy that relates to the Nordic/Swedish model and that, at most, represents a reformed or even improved variant of the traditional welfare state.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while some have argued that the policy content of the Nordic model has changed during the last decades, the idea of the Nordic model possesses remarkably resilient characteristics. Or, what is resilient is an idea of Nordic approaches to welfare. Even when framed with changing terminology and altered policy solutions, something fundamentally Nordic can be found from Nordic social policy. It is not a monolithic model and that precisely is its very strength. The scholarly debate on the future of the Nordic model appears to have reached an irreconcilable stage. However, looking at the elite discourses, it is possible to see that the different welfare futures are not necessarily as diametrically opposed as one might think.

A number of different elites from the whole range of political convictions and organizations seem to support the core ideas of a Nordic model but, remarkably, it represents many things to many people and is much less of an ideal-typical and, hence, clear-cut model than one would assume based on the literature. What is shared with almost all references to the Nordic/Finnish/Swedish model is that it is primarily a set of ideals, principles and aspirations. Almost all participants interviewed make a clear distinction between what their variant of the Nordic model ought to represent and what their interpretation of the current pressures and challenges is. The very content and meaning of the word equality, from a more liberal equality of opportunity to a traditional social democratic equality of outcome, is but one example. The policy content of the welfare state and the challenges it faces are discussed but hardly anyone questions its core principles.

In Finland, the discourse is more pragmatic and more about how the welfare state adapts under (discursively framed) structural and domestic pressures. It is less about foundational and distinctively normative debates. In Sweden, the dominant discourses and narratives on welfare are clearly more polarized at the level of ideas and the question is largely not about whether the welfare state is the root cause or the solution to the problems defined. This difference in national welfare discourses is perhaps not so surprising. After all, the post-war history of Finland has been characterized by the need to forge an internal consensus in front of external challenges whereas the Swedish political debate has been much more ideologically polarized between left and right. What is now characteristic in the Swedish discourse is a debate on what kind of an interpretation of the Swedish welfare state would be needed in order to deal with and even solve some of the current problems. In the end though, a distinctively Swedish, Finnish or Nordic model of welfare will continue to exist at least at the level of ideas, as the concept itself seems to carry meaning and relevance to elites and citizens alike.

Does all this mean that the twenty-first century Nordic model is nothing but an empty vessel to which a whole host of ideas and policy solutions can be loaded? It certainly does not. While legitimate stories on welfare vary in Finland and Sweden, discourse in both countries seems to be characterized by the oscillating meanings of the Nordic model. Certainly, based on my argument above, it can be argued that the future shape of the Nordic model will be determined by ideational factors, both in terms of what ideas continue to be at the heart of a/the Nordic model(s) and which ideas and narratives of internal and external pressures for policy reform are able to enter the repertoire of legitimate stories about the Nordic Model.

Interviews

Sweden

Senior official at the Swedish Confederation of Professional Associations (SACO), Stockholm, 28 April 2009.

Senior official at the Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO), 5 May 2009.

Member of Parliament for the Left Party (V), Stockholm, 13 May 2009.

Senior official at the Swedish Red Cross (SRK), Stockholm, 18 May 2009.

Senior official at the Swedish Confederation for Professional Employees (TCO), 15 May 2009.

Former researcher at the Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO), Stockholm, 18 May 2009.

Political state secretary (Christian Democrat), Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Stockholm, 19 May 2009.

Political adviser (Christian Democrat), Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Stockholm, 19 May 2009.

Senior official at the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SKL), Stockholm, 19 May 2009.

Member of Parliament for the Green Party (MP), Stockholm, 2 October 2009.

Political adviser (Moderate), Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Stockholm, 5 October 2009.

Senior official at the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise, Stockholm, 5 October 2009.

Senior official at Save the Children Sweden, Stockholm, 6 October 2009.

Finland

Senior adviser at the Finnish Confederation of Professionals (STTK), Helsinki, 26 March 2009.

Senior official at the Confederation of Finnish Industries (EK), Helsinki, 27 March 2009.

Senior official at the Central Union of Agricultural Producers and Forest Owners (MTK), Helsinki, 27 March 2009.

Former Minister of Social and Health Affairs (Social Democrat), Espoo, 30 March 2009.

Member of Parliament for Left Alliance (Vasemmistoliitto, Vas), Helsinki, 31 March 2009.

Member of Parliament for the National Coalition Party (Kokoomus, KOK), Helsinki, 2 April 2009.

Senior official at the Confederation of Unions for Professional and Managerial Staff (AKAVA), Helsinki, 2 April 2009.

Senior official at the Finnish Red Cross (SPR), Helsinki, 2 April 2009.

Senior official at the Central Organization of Finnish Trade Unions (SAK), 6 April 2009.

Former senior civil servant at the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Helsinki, 7 April 2009.

Senior civil servant in the Finnish Ministry of Finance, Helsinki, 24 June 2009.

Political State Secretary (Centre Party), Helsinki, 26 June 2009.

Senior official at the Mannerheim League for Child Welfare (MLL), Helsinki, 30 June 2009.

Acknowledgments

This article has had a relatively long incubation period. First versions were presented at my end of project workshop on Ideas and/on Welfare, organized at Oxford Brookes University in January 2010, at the ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops in Münster in March 2010 and at a joint seminar of the Institute for Society and Social Justice Research and Caledonian Business School at Glasgow Caledonian University in March 2011. I would like to thank all participants on these occasions for their invaluable comments and feedback. I would also like to thank Jonas Hinnfors, Stephen Hurt, Michael Lister, Luke Martell, Mikael Nygård, Magnus Ryner, Matthew Watson and three anonymous referees for their insightful comments on earlier versions of the current article. The article arises out of research on ‘Welfare state practices and the constitution of the citizen: Nordic models of capitalism in an age of globalisation’ funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (project grant RES-000-22-3298). The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mikko Kuisma

Mikko Kuisma is senior lecturer in International Relations at Oxford Brookes University, UK. He received his PhD in Political Science from the University of Birmingham where he also held an ESRC Postdoctoral Research Fellowship. Before joining Oxford Brookes, he held a Jean Monnet Fellowship at the European University Institute in Florence and taught European politics at Aberystwyth University. His main research interests lie in the comparative political economy of European welfare states, with a special interest in the role of citizenship in welfare capitalism. His work has been published in, for example, Cooperation and Conflict, New Political Economy, Citizenship Studies and Public Administration. He is guest editor of a symposium on the Role of Ideas in Welfare State Crises and Transformations for Public Administration (2014).

Notes

1. While the paper is not asking if a real and concrete Nordic model exists, the term is used throughout the paper, partly because it is now common practice to frame Nordic welfare debates with this terminology but partly because there is value in discussing the model as a heuristic device.

2. The sample contains more trade union than business organization representatives, simply due to the reason that the employer sector in both countries has two central business employer organizations that play a significant role as employer counterparts to the central trade union organizations. While the blue collar central trade union organizations (SAK in Finland and LO in Sweden) dominate, both countries have other powerful unions representing other sectors and a decision was made to include them in the sample.

References

- Alestalo, M., and S. Kuhnle. 1987. “The Scandinavian Route: Economic, Social, and Political Developments.” In The Scandinavian Model: Welfare States and Welfare Research, edited by R. Erikson, E. J. Hansen, S. Ringen, and H. Uusitalo. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

- Andersson, J. 2009. “Nordic Nostalgia and Nordic Light: The Swedish model as Utopia 1930–2007.” Scandinavian Journal of History 34 (3): 229–245. doi:10.1080/03468750903134699.

- Béland, D. 2010. “The Idea of Power and the Role of Ideas.” Political Studies Review 8 (2): 145–154. doi:10.1111/psr.2010.8.issue-2.

- Béland, D., and R. H. Cox, eds. 2010. Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Béland, D., and A. Lecours. 2008. Nationalism and Social Policy: The Politics of Territorial Solidarity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Béland, D., and K. Petersen. 2014. “Introduction: Social Policy Concepts and Language.” In Analysing Social Policy Concepts and Language: Comparative and Transnational Perspectives, edited by D. Béland and K. Petersen. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Berman, S. 1998. The Social Democratic Moment: Ideas and Politics in the Making of Interwar Europe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Berman, S. 2006. Primacy of Politics: Social Democracy and the Making of Europe’s Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blyth, M. 2002. Great Transformations: The Rise and Decline of Embedded Liberalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Childs, M. W. 1936. Sweden: The Middle Way. London: Faber.

- Christiansen, N. F., and P. Markkola. 2006. “Introduction.” In The Nordic Model of Welfare: A Historical Reappraisal, edited by N. F. Christiansen, K. Petersen, N. Edling, and P. Haave. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Cox, R. H. 2004. “The Path-Dependency of an Idea: Why Scandinavian Welfare States Remain Distinct.” Social Policy & Administration 38 (2): 204–219. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2004.00386.x.

- Czarniawska, B. 2004. Narratives in Social Science Research. London: SAGE.

- Edling, N., J. H. Petersen, and K. Petersen. 2014. “Social Policy Language in Denmark and Sweden.” In Analysing Social Policy Concepts and Language: Comparative and Transnational Perspectives, edited by D. Béland and K. Petersen. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Einhorn, E. S., and J. Logue. 2003. Modern Welfare States: Scandinavian Politics and Policy in the Global Age. 2nd ed. Westport: Praeger.

- Einhorn, E. S., and J. Logue. 2010. “Can Welfare States Be Sustained in a Global Economy? Lessons from Scandinavia.” Political Science Quarterly 125 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2010.tb00666.x.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity.

- Geyer, R. R. 2003. “Globalization, Europeanization, Complexity, and the Future of Scandinavian Exceptionalism.” Governance 16 (4): 559–576. doi:10.1111/1468-0491.00228.

- Giddens, A. 1976. New Rules of Sociological Method: A Positive Critique of Interpretative Sociologies. London: Hutchinson.

- Goodman, R., and I. Peng. 1996. “The East Asian Welfare States: Peripatetic Learning, Adaptive Change, and Nation-Building.” In Welfare States in Transition, edited by G. Esping-Andersen. London: Sage.

- Hall, P. A., and D. W. Soskice, eds. 2001. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hay, C. 2002. Political Analysis. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Hay, C. 2004. “Ideas, Interests and Institutions in the Comparative Political Economy of Great Transformations.” Review of International Political Economy 11 (1): 204–226. doi:10.1080/0969229042000179811.

- Hay, C. 2006. “What’s Globalization Got to Do with It? Economic Interdependence and the Future of European Welfare States.” Government and Opposition 41 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1111/goop.2006.41.issue-1.

- Hay, C., and N. Smith. 2010. “How Policy-Makers (Really) Understand Globalization: The Internal Architecture of Anglophone Globalization Discourse in Europe.” Public Administration 88 (4): 903–927. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01863.x.

- Heclo, H. 1986. “Reaganism and the Search for a Public Philosophy.” In Perspectives on the Reagan Years, edited by J. L. Palmer. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

- Hinnfors, J. 2006. Reinterpreting Social Democracy: A History of Stability in the British Labour Party and Swedish Social Democratic Party. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Iversen, T. 1999. Contested Economic Institutions: The Politics of Macroeconomics and Wage Bargaining in Advanced Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Iversen, T., and J. D. Stephens. 2008. “Partisan Politics, the Welfare State, and Three Worlds of Human Capital Formation.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (4–5): 600–637. doi:10.1177/0010414007313117.

- Julkunen, R. 2006. Kuka vastaa? Hyvinvointivaltion rajat ja julkinen vastuu. Helsinki: Sosiaali- ja terveysalan tutkimus- ja kehittämiskeskus Stakes.

- Kettunen, P. 2001. “The Nordic Welfare State in Finland.” Scandinavian Journal of History 26 (3): 225–247. doi:10.1080/034687501750303864.

- Kettunen, P., and K. Petersen. 2010. “Introduction: Rethinking Welfare State Models.” In Beyond Welfare State Models: Transnational Historical Perspectives on Social Policy, edited by P. Kettunen and K. Petersen. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Kitschelt, H. 1994. The Transformation of European Social Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kitzinger, C. 2004. “Feminist Approaches.” In Qualitative Research Practice, edited by C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. Gubrium and D. Silverman. London: Sage.

- Kuisma, M. 2007a. “Nordic Models of Citizenship: Lessons from Social History for Theorising Policy Change in the ‘Age of Globalisation’.” New Political Economy 12 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1080/13563460601068818.

- Kuisma, M. 2007b. “Social Democratic Internationalism and the Welfare State after the ‘Golden Age’.” Cooperation and Conflict 42 (1): 9–26. doi:10.1177/0010836707073474.

- Kuisma, M. 2013. “Understanding Welfare Crises: The Role of Ideas.” Public Administration 91 (4): 797–805. doi:10.1111/padm.2013.91.issue-4.

- Kuisma, M., and M. Nygård. 2015. “The European Union and the Nordic Models of Welfare – Path Dependency or Policy Harmonisation?” In The Nordic Countries and the European Union: Still the Other European Community? edited by C. H. Grøn, P. Nedergaard, and A. Wivel. London: Routledge.

- Kuisma, M., and M. Ryner. 2012. “Third Way Decomposition and the Rightward Shift in Finnish and Swedish Politics.” Contemporary Politics 18 (3): 325–342. doi:10.1080/13569775.2012.702975.

- Kvale, S. 2007. Doing Interviews. London: SAGE.

- May, T. 2001. Social Research: Issues, Methods and Process. 3rd ed. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Mehta, J. 2010. “The Varied Roles of Ideas in Politics: From “Whether” to “How”.” In Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, edited by D. Béland and R. H. Cox. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pontusson, J. 2011. “Once again a Model: Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World.” In What’s Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times, edited by J. E. Cronin, G. Ross, and J. Shoch. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Ritchie, J., J. Lewis, and G. Elam. 2003. “Designing and Selecting Samples.” In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, edited by J. Ritchie and J. Lewis. London: SAGE.

- Rothstein, B. 2005. Social Traps and the Problem of Trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ryner, J. M. 2002. Capitalist Restructuring, Globalisation, and the Third Way: Lessons from the Swedish Model. London: Routledge.

- Ryner, J. M. 2007. “The Nordic Model: Does it Exist? Can it Survive?” New Political Economy 12 (1): 61–70. doi:10.1080/13563460601068644.

- Sajari, P. 2009. “Kännykkäyhtiön painostus sai aikaan Lex Nokian.” Helsingin Sanomat, February 1.

- Scharpf, F. W. 1991. Crisis and Choice in European Social Democracy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Schatzman, L., and A. L. Strauss. 1973. Field Research: Strategies for a Natural Sociology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Schmidt, V. A. 2002a. “Does Discourse Matter in the Politics of Welfare State Adjustment?” Comparative Political Studies 35 (2): 168–193. doi:10.1177/0010414002035002002.

- Schmidt, V. A. 2002b. The Futures of European Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schreier, M. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. London: SAGE.

- Silverman, D. 2006. Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction. 3rd ed. London: SAGE.

- Steinmo, S. 2003. “Bucking the Trend? The Welfare State and the Global Economy: The Swedish Case up Close.” New Political Economy 8 (1): 31–48. doi:10.1080/1356346032000078714.

- Tarrow, S. 2010. “The Strategy of Paired Comparison: Toward a Theory of Practice.” Comparative Political Studies 43 (2): 230–259. doi:10.1177/0010414009350044.

- Trägårdh, L. 2007. “The “Civil Society” Debate in Sweden: The Welfare State Challenged.” In State and Civil Society in Northern Europe: The Swedish Model reconsidered, edited by L. Trägårdh. Oxford: Berghahn.

- Wincott, D. 2003. “Slippery Concepts, Shifting Context: (National) States and Welfare in the Veit-Wilson/Atherton Debate.” Social Policy & Administration 37 (3): 305–315. doi:10.1111/1467-9515.00340.

- Wincott, D. 2013. “The (Golden) Age of the Welfare State: Interrogating a Conventional Wisdom.” Public Administration 91 (4): 806–822. doi:10.1111/padm.2013.91.issue-4.