ABSTRACT

Why do exercises in collaborative governance often witness more impasse than advantage? This paper suggests putting power at center stage and focusing the analysis on the micro level. It is by looking at the daily ‘minutiae’ of collaboration, and at the dynamics (here called flows of power) that they set off, that we can gain insights into failures of collaborative arrangements. To enable a power-sensitive and process-oriented analysis of collaborative governance, the paper develops an analytical framework for the empirical exploration of collaborative governance at the micro level. The framework examines how design choices at the outset of collaboration are re-interpreted, challenged, and transformed by micro-dynamics taking place over the course of the arrangement. The article argues that a process-oriented investigation of how collaboration evolves and unfolds over time elucidates the subtleties of power, which may be overlooked if we only consider outcomes rather than the processes that engender these outcomes. The work is based on an abductive research approach and illustrates the analytical possibilities of the framework by zooming in on an exemplar of a collaborative arrangement for planning the route of a high-voltage electricity line in Germany.

Introduction

Collaborative governance has become a focal point for tackling a wide array of issues in policymaking: by generating new spaces of interaction for actors from different sectors, it supports the co-development of policies and strategies to tackle complex issues in a deliberative and consensus-seeking mode (Ansell and Gash Citation2008; Ansell and Torfing Citation2018). The benefits of collaborative governance have been extensively discussed in the literature (Ansell Citation2012; Dryzek Citation2001). Huxham (Citation1996) speaks in this regard of collaborative advantage, namely the synergetic production of outcomes that no actor would have been able to achieve alone. However, both practice and research often reveal experiences of what I term collaborative impasse. This refers to moments in which collaboration becomes stuck, when energies invested in designing, convening, and running a collaborative process seem squandered and the results achieved appear negligible. Thus, a gap seems to emerge between the rhetoric on the benefits of collaboration versus its actual results (Hoppe Citation2011; van der Arend and Behagel Citation2011).

More research is therefore needed to understand the dynamics influencing the performance of collaborative governance. This article suggests that a power-sensitive and process-oriented investigation of collaboration can contribute to address this gap. By focusing the analysis on the micro level and putting power at center stage, understood in terms of ‘seemingly trivial incidents and transactions’(Morley Citation2006, 543 cited in Escobar Citation2019), I argue that it is by looking at the daily ‘minutiae’ (Flyvbjerg Citation2006b, 237) of collaboration that we can gain insights into failures of collaborative arrangements. The research question guiding the analysis is hence: ‘How can we empirically study and analyze power dynamics that lead to collaborative impasse?’

By building on previous works (e.g. Avelino Citation2011; Flyvbjerg Citation2002; Huxham and Beech Citation2008; Purdy Citation2012), the article develops an analytical framework for the empirical exploration of collaborative governance at the micro level. The framework examines how the design choices made by conveners and facilitators at the outset of collaboration (e.g. framing of the agenda, participants, participatory methods) are – subtly or overtly – re-interpreted, challenged, and transformed by micro-dynamics taking place over the course of the arrangement. I argue that a process-oriented investigation of how collaboration evolves and unfolds over time can track apparently insignificant, yet relevant chains of action (Schatzki Citation2002), here called flows of power, which might lead to collaborative impasse and impact the performance of collaborative arrangements.

After presenting the theoretical foundation and the abductive methodological approach that inform the building of the framework, the article illustrates its two components and subsequently discusses its analytical possibilities through an exemplar (Flyvbjerg Citation2006b) of a collaborative arrangement for planning the route of a high-voltage electricity line in Germany.

The micro level of collaborative governance

A micro-level perspective can reveal how everyday interactions fundamentally shape the course of collaboration (Bartels Citation2014; Collins Citation2005; Escobar Citation2019; Goffman Citation1959). It is at this level of analysis that we can observe how collaboration gets done and undone (de Souza Briggs Citation1998, 1), through a tangled bundle of design choices constantly intersecting with participants’ viewpoints on how the arrangement should be run. For example, a strategically placed microphone may intend to give certain actors greater opportunity to speak while denying others; the decision of a facilitator not to discuss an issue beyond a certain timeframe may strongly influence the quality of the process outcomes. Such choices define the conditions under which collaboration takes place. However, they do not stand alone: A participant seated at the back may seize the microphone and raise their voice; heated debate among the group may distract the facilitator from imposing a time limit. It is in such interactions that we see how a collaborative process can suddenly change direction. Understanding how collaboration works in its daily practice is hence the first step to identify potential traps and hindrances that may affect its performance. The present section repurposes existing debates on collaboration and power and makes them suitable for empirical analysis. It introduces key analytical concepts that contribute to a processual understanding of collaboration as an ongoing interplay between designed and emerging interaction orders, on which the framework relies.

Collaborative governance as interplay between designed and emerging interaction orders

Collaborative governance at the micro level can be described in Goffmanian terms as assembling new interaction orders (Escobar Citation2019, 189). Like a traffic code, an interaction order establishes ‘the ground rules for a game’ (Goffman Citation1983, 5). By assembling new interaction orders, collaborative governance thus creates ways for actors to interact with each other, where existing interaction rituals (Collins Citation2005) are altered, and new power regimes can emerge (Escobar Citation2019). In the context of collaboration, the assemblage of new interaction orders (henceforth, designed interaction orders) materializes in the process design, which determines the roles and plot of the play performed on the collaborative stage (Goffman Citation1959; Escobar Citation2015). Conveners and facilitators play a crucial role in this (Escobar Citation2019): Conveners have or receive a mandate to initiate the process, and can enlist facilitators, namely professionals with ‘process expertise’ (Escobar Citation2015; Molinengo, Stasiak, and Freeth Citation2021), to design and moderate its communicative interactions. Designing collaboration means, in Bobbio’s (Citation2019) words, ‘making decisions’ on how the stage will look. By way of their formal authority (Hardy and Phillips Citation1998), facilitators and conveners define, through multiple and fine-grained design choices (e.g. list of invitees, agenda, setting of the room), the rationale, framing, and rules operating in the collaborative setting.

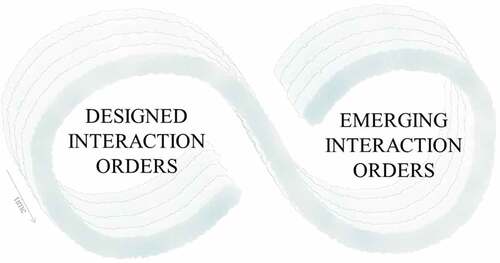

When the collaborative process opens to participants, these new actors engage with the script proposed by conveners and facilitators. However, unlike in a theater performance, actors on the collaborative stage usually depart from this original script: they ‘appropriate, resist and transform […] roles and identities’ (Felt and Fochler Citation2010, 219) and set the script in motion (Weick Citation2001, 225). Those responsible for the collaboration, on the other side, react to these interventions by reinstating their original plans or adapting some of its components. In doing so, participants, facilitators, and conveners together generate what I call an emerging interaction order. attempts to visually capture collaborative governance at a micro level as an ongoing interplay between designed and emerging interaction orders.

Figure 1. Collaborative governance at the micro level: an ongoing interplay between designed and emerging interaction orders.

In this interplay, structure (designed interaction orders) and agency (emerging interaction orders) exist in a duality, with each continually contributing to transforming or reproducing the other (Giddens Citation1984). Collaboration thus becomes a mobile and fluid phenomenon, constantly shaped by a collective process of assembling, disassembling, and reassembling (Escobar Citation2019) the designed interaction order according to the interests and viewpoints of those in the room at a specific time of the process. This process-oriented approach, methodically supported by scholars rooted in process research (Langley Citation1999; Langley et al. Citation2013), allows considering changes and unpredicted circumstances (Bartels Citation2012, 437).

Collaborative impasse

Following Weick (Citation1995, 86), who focuses on ‘interruptions’ as an opportunity to retrospectively make sense of the experience, this work analyses moments of collaborative impasse as a starting point to investigate collaborative performances. Junctures leading to collaborative impasse may include a lack of clarity on what goals to achieve, new events questioning the entire purpose of the collaboration, or unmanaged disputes and mistrust. When collaborative impasse manifests at the micro level, an external observer may sense a changing atmosphere in the group: growing frustration among participants regarding the lack of achievements promised by the collaborative setting; participants’ interactions falling back into exclusionary dynamics; unmanageable divisions in the group; participants’ lack of trust towards the conveners and their agenda. Originally, Huxham (Citation1996) contrasts ‘collaborative advantage’ and ‘collaborative inertia’; for analytical purposes, I choose to speak instead of ‘collaborative impasse.’ What is observable as a result of inertia or impasse is similar: little or nothing happens. However, the two metaphors emphasize different dynamics. Inertia implies a tendency to remain unchanged and suggests a static image of ritualized inaction among participants in collaborative settings. In contrast, collaborative impasse has a temporal connotation: it assumes a previous interaction among actors that led to deadlock, which is one of the core interests of this paper.

Collaborative impasse emerges in the ongoing interplay between designed and emerging interaction orders. When moments of collaborative impasse arise, the outcomes of the collaborative process move away from the initial goals set by the designed interaction order. This is not to say that arrangements succeed only by sticking to the original process design. Indeed, instances of collaborative impasse can also emerge when the designed interaction order does not consider participants’ viewpoints, priorities, and interests (Bartels Citation2012). Instead, collaborative impasse signals that the interactions between the participants assume an unproductive character. It is on these scenarios that the present inquiry focuses.

Power as analytical lens

Power is here treated as a ‘sensitizing concept’ (Bacharach and Lawler Citation1980, 5) to investigate those dynamics that have led to a moment of collaborative impasse. Such analysis includes a wide range of activities, interventions, and tactics used by actors to influence the collaborative exercise, according to their own perspective on how the process should be run. An example of such interventions is framing, namely the action of defining, restricting, and narrowing the range of questions, options, or possibilities (Blue and Dale Citation2016). While conceiving the process design, conveners might draft an agenda that invites participants to discuss possible solutions to an infrastructural project, without discussing whether such a project is necessary. A participant might react to this by calling attention to marginalized issues. In response, a facilitator might frame this heated and critical intervention as merely an individual experience or ‘anecdotal’ (Innes and Booher Citation2015, 200) and consequently dismiss the person’s viewpoint.

Such interventions suggest a shift of analysis from distinguishable actions of single actors towards an analysis of the interactions among them (Arendt Citation1970). In this way, the study embraces the call by Flyvbjerg (Citation2006a, 367) to take a step back from focusing only on who has power, based on actors’ most visible sources of power, and instead extends its focus to the question of how power is exercised and unfolds. A practice-based view on power supports this analytical choice: Cook and Seely Brown (Citation1999) hold that the idea of power as something to be possessed and exercised over others – an aspect underlined by many of the classical definitions of power (Bachrach and Baratz Citation1962; Dahl Citation1957; Lukes Citation2005) – is to be complemented with an understanding of power as ‘situated, provisional, revisable, open-ended and always in the making’ (Marshall and Rollinson Citation2004, 75 on the work of Cook and Brown Citation1999). Following Foucault’s invitation to decipher power in ‘a network of relations, constantly in tension, in activity’ (Foucault Citation1977, 26 cited in Marshall and Rollinson Citation2004), the study traces micro-dynamics that substantially influence the collaboration, which a static view on power as possession would most likely overlook (Tello-Rozas, Pozzebon, and Mailhot Citation2015, 1066). To illustrate the difference among these two perspectives, I suggest an analytical distinction between acts and flows of power in the context of collaborative governance:

An act of power is the capacity of an actor to intervene at a specific moment during a collaborative process, by accessing temporarily available sources of power, according to their own interests and hence opinion on how the arrangement should be run.

This definition entails an understanding of power as possession. Returning to the previous example: During the design phase, conveners shape the framing of the collaboration according to their perspective, by means of their formal authority (Hardy and Phillips Citation1998) at this stage of the process. Analyzing such acts of power answers the crucial question of who has power and provides information on the timing, circumstances, and actor constellation in which this act takes place. However, such an analysis, while necessary, is insufficient. To investigate the effects of this act on the collaborative arrangement’s performance, I build on Schatzki’s definition of chains of actions (Citation2002, 148–149)Footnote1 and introduce the concept of flow of powerFootnote2:

A flow of power is a chain of actions, originating from one initial act of power and including the responses of other actors – be they participants, conveners, or facilitators – that contribute to the ongoing interplay between designed and emerging interaction orders.

The concept of flow of power – as its use in the framework will show – can elucidate the subtleties of power, which may be overlooked if we only consider outcomes rather than the processes that engender these outcomes.

Materials and methods

Finally, at the end of fifteen months of endless attempts to include everyone in the planning process, and after the final results of the collaboration had been sent to the local authority for evaluation, there it was: anew citizen initiative claiming that their opinion had not been included in the process; And that everything needed to be discussed again.

(Author’s field notes, July2015)

The above event offers a tangible instance of collaborative impasse. It is taken from the case study that informs the present article, namely an arrangement to collaboratively plan the route of a high-voltage electricity line in southern Germany. The intention of this article is not to fully analyze the case study, but to offer concrete examples of how the framework could be applied to understand collaborative impasse, by zooming-in (Nicolini Citation2009) on details, stories, processes – ‘exemplars’, in Flyvbjerg’s (Citation2006b) words – that shaped the collaborative arrangement. The field note excerpt describes a citizen initiative that questions the legitimacy of the arrangement after its conclusion. As an action researcher working in this setting, fulfilling both convening and academic tasks, I constantly observed and struggled with how collaboration’s original plans radically changed during the process, often in unexpected ways. No matter how much engagement, care, financial resources, and time the conveners invested in this process, moments of collaborative impasse were recurring features. This article grapples with this research puzzle through an abductive logic of inquiry (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow Citation2012, 28).

The case study

The design and implementation of the collaborative arrangement took place in 2014–2015 (15 months) within a three-year action research project. Run in two localities, the arrangement was co-initiated and implemented by the research team I was part of, in partnership with one of the German TSOs (Transmission System Operators) and supported by professional facilitators. Here, citizens and local actors (mayors of the potentially affected areas, local authority officers, and NGOs representatives) were invited to suggest and plan, together with experts, alternative routes for a new electricity line running through the two localities.Footnote3 The collaborative process included a series of open events for all citizens to suggest new potential corridors for the electricity line. The complex and detailed work in further developing these ideas was done in planning workshops with a group of approximately 20 members, composed of eight randomly selected citizens,Footnote4 TSO employees, and local actors. The choice of this case is not accidental: As Flyvbjerg states, ‘extreme cases often reveal more information because they activate more actors and more basic mechanisms in the situation studied’ (Citation2006b, 229). The case study offered fertile ground for a power-sensitive and process-oriented analysis of collaborative governance at the micro level, especially for its contested nature: The electricity company had clear interests in building the high-voltage power line as quickly and cost-efficiently as possible, while also being jointly responsible for co-designing and convening the collaborative planning process. Further, the framing of the question to be discussed was quite narrow: It only allowed discussion of where the electricity line should run, but not whether this infrastructural project was required. These initial conditions, in particular the presence of a non-impartial co-convener, provided the opportunity to investigate the multiple ways through which participants contested, resisted, or re-negotiated the rules of the game set by the designed interaction order. This last one, despite the structural power asymmetries among actors involved and the highly complex task of identifying new, alternative routes for a high-voltage electricity line, nonetheless attempted to alter existing power regimes: It redistributed roles and included new kinds of expertise (e.g. citizens’ local knowledge) in the planning process. The action research approach conducted in this case study, with researchers actively participating in the design of this arrangement, gave access to its backstage activities (Escobar Citation2015, Molinengo, Stasiak, and Freeth Citation2021) and allowed a close analysis of the design choices that shaped the designed interaction order.

Data collection and analysis

Close involvement in the process allowed a thick description (Geertz Citation1973) of the dynamics shaping the collaboration. Triangulation of data (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow Citation2012, 61) was ensured with:

Fieldnotes from the author’s participation in almost daily conference calls with the TSOs and the professional facilitators to discuss the design and implementation of the arrangement over 15 months; seven open events; and five two-day planning workshops;

24 in-depth interviews, conducted together with two other researchers, before, during, and after the collaborative arrangement with conveners, facilitators, and representatives of the involved participants, focusing on their own experience of the collaborative arrangement (i.e. perceived successes and failures, motivation, expected results, aspects to improve);

Facilitators’ scripts of the overall process design, open events, and planning workshops;

Minutes of the conference calls and of each collaborative event (usually taken by one of the professional facilitators).

A focus on power was not part of the original research design, but emerged retrospectively, in a sense-making phase (ibid) following immersion in the research field. Since various forms of power cannot be directly observed, a main task consisted of developing informed categories for observing power – in this case retrospectively (Haug, Rucht, and Teune Citation2013, 25). Their identification took place within what Schwartz-Shea and Yanow (Citation2012, 27) term a ‘simultaneous and iterative puzzling over empirical materials and theoretical literatures.’ Three main concepts from the literature – interaction order (Goffman Citation1983), collaborative inertia (Huxham Citation1996), and arenas for power (Purdy Citation2012) – offered a theoretical anchor to decipher the ‘overwhelming nature of boundaryless, dynamic, and multi-level process data’ (Langley Citation1999, 694). The empirical material was analyzed in two stages. The first stage aimed to reconstruct the designed interaction order of the collaborative arrangement. By relying on Purdy’s concept of ‘arenas for power,’ defined as the components of collaborative governance processes that provide actors ‘opportunities for the exercise of power’ (Citation2012, 411), the main (micro) design choices through which facilitators and conveners shaped the rationale of the collaboration were mapped, and later clustered into ten arenas, illustrated in the next section. Interviews with facilitators and conveners, combined with their scripts, gave access respectively to their ‘embodied’ and ‘inscribed knowledge’ (Freeman and Sturdy Citation2014, 8, 11).

This step set the foundation for retrospectively tracking, in the second stage, the dynamics leading to moments of collaborative impasse. Based on the earlier description of the phenomenon, instances of collaborative impasse were identified by looking for events in the history of the collaboration that hinted at the emergence of disputes or mistrust among actors. This was done by combining data sources from participatory observation (researcher and convener’s perspective), interviews (actors’ interpretations), and archival data. Subsequently, the interplay between designed and emerging interaction orders connected to these events was reconstructed. This was done by tracing back actors’ interventions, the flows of power they set in motion, and the arenas involved. Particular attention was dedicated to those flows engaging with a high number of arenas over their course. Similarly to building a plane while flying it, the main result of this analysis consisted of the framework illustrated in the next section.

For validation purposes, several versions of the framework – in particular, its ten arenas – were tested, further developed, and integrated in the empirical analysis of other collaborative settings (Molinengo and Stasiak Citation2020). Their investigation allowed the researchers to double-check the consistency, interrelatedness, and labelling of the framework’s arenas for power. Furthermore, following the practice of ‘member-checking’ (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow Citation2012, 106), an adapted version of the framework for practitioners was discussed during a two-day workshop with public administration representatives of the German government involved in the design and/or implementation of collaborative governance strategies. Finally, this framework was also substantiated by an ongoing exchange with relevant communities of practice, such as facilitators of collaborative processes.

The framework of analysis

This section presents, by means of examples from the case study, the two main components of the framework for assessing the performance of collaboration at the micro level, namely: 1. mapping the designed interaction order’s arenas of power; and 2. tracking how this designed interaction order interplays over time with emerging interaction orders, through the analysis of selected flows of power. The first analytical step supports researchers in detailing the architecture of the collaborative arrangement, as initially planned by conveners and facilitators at its outset. The second step focuses on the wide range of activities, interventions, and tactics used by actors to influence the collaborative exercise, and on the chains of actions (Schatzki Citation2002) that they set off (emerging interaction orders), to illustrate how the initial collaborative architecture is being appropriated, resisted, and transformed (Felt and Fochler Citation2010, 219) over time by its participating actors.

Mapping the designed interaction order and its arenas

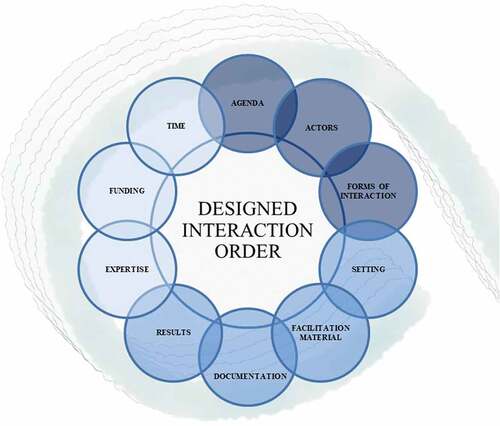

A designed interaction order is not neutral, but a power-loaded structure being generated and negotiated by a group of actors according to their specific agendas at the initial stages of the collaboration (Herberg Citation2020). The framework supports researchers in disentangling the bundle of micro-decisions (acts of power) – sometimes intuitive, sometimes deliberately strategic – undertaken by facilitators and conveners in the design phase, by identifying ten arenas for power (see ) (Purdy Citation2012) that shape the designed interaction order.

While some of the arenas (in particular: agenda, actors, and forms of interaction) find extensive correspondence with the literature on process design (Ansell and Gash Citation2008; Fung Citation2003, Citation2005; Kadlec and Friedman Citation2007; Bryson et al. Citation2013; Purdy Citation2012), other arenas – especially those related to the material dimension of collaborative arrangements (setting, facilitation material, documentation, and results) – are less systematically discussed, yet emerged in the abductive research process that informs this paper.

The first three arenas represent the core of the designed interaction order and answer the ‘what’ (agenda), ‘who’ (actors) and ‘how’ (forms of interaction) questions of collaboration (Fung Citation2003). The agenda arena defines the issue at stake and the framing within which participants are invited to contribute. In the present case study, the agenda did not tackle the question of whether the infrastructural project was actually required, but instead opened up a space of influence to a broader audience on where the electricity line should run. The actors arena refers to the question of who has (and who exercises) a voice in the process, and in which role. In our case, the conveners’ team charged a group of 20 experts, policymakers, and lay citizens with planning new alternative routes for the electricity line, instead of first asking experts to draft proposals that would pre-frame the results. The forms of interaction arena addresses the question of how communicative interaction occurs among actors, and relies on subtle yet powerful decisions from facilitators (Bartels Citation2014, 657). For instance, in our case, site visits were organized to identify the advantages of and hindrances to each potential route, rather than simply basing discussions on the presented plans. This design choice was intended to transform the classic dichotomy between experts and lay actors

The next four arenas relate to the material dimension of collaboration, in particular in terms of physical conditions and artifacts that should support the communicative interaction of its participants (Schatzki Citation2002, 41) (setting; facilitation material) and the material products that the arrangement is expected to deliver (documentation; results). The setting arena sheds light on how the physical setting ‘constructs’ the roles participants can take on a certain stage (Hajer Citation2005, 626). During site visits, local citizens had greater understanding of the landscape features than non-local environmental planners and could point to important factors for the planning process. The facilitation material arena encompasses the artifacts used by facilitators to enable communicative interactions, such as markers, ‘Post-it’ notes, and pin boards (Molinengo and Stasiak Citation2020). The presence of a detailed map, on which to draw alternative corridors, enabled citizens to contribute to the planning process with greater precision than having a loose discussion without any visual support. The sixth arena refers to the issue of documentation. Crucial questions here are: Who is documenting the interaction? How is the documentation shared with the broader public? In this case, documentation was a highly debated issue within the conveners’ team: The written minutes of a public event, if disseminated within a context of highly complex planning and escalated conflict, could potentially be reframed and manipulated via social media. This led the conveners’ team to publish online only partly the documentation of Q&A sessions between experts and citizens. The seventh arena concerns the design of what results are to be delivered at the end of the collaboration, and their foreseen impact (Fung Citation2005). The conveners’ team held intensive discussions on whether the collaborative arrangement should aim to reach consensus on one preferred route for the electricity line. Ultimately, several alternatives were submitted to the local planning authority in order to increase the prospect of influencing the planning process.

A last group of arenas refers to different kinds of resources identified by conveners and facilitators as necessary for running the collaborative arrangement. In particular, the issues of expertise, funding, and time are identified. The expertise arena defines who is considered an expert in the collaborative arrangement, and hence given access to finite resources (e.g. more time to speak). The choice to invite certain experts to participate in a process also outlines what information will be made available to ‘non-experts.’ In our case, environmental planners employed a color-coded legend to represent the geographical space within which alternative corridors would be developed, thereby allowing participants to quickly visualize locations from which electricity lines were excluded for technical, environmental, or cultural reasons. In this way, participants were enabled to formulate more precise and potentially viable proposals. The issue of funding had a substantive impact in our case: Initially, the hiring of professional facilitators was thought to be fully covered by the research project’s budget; however, after some months, it became clear that the complexity of the issue required more collaborative events than were originally planned. This raised the question within the conveners’ team of whether a co-financing model, supported by the TSO, might delegitimize the collaborative arrangement, cast doubt on the researchers’ neutrality as conveners, and limit their scope for making independent design choices. Ultimately, the team approved the co-financing model, in order to guarantee professional moderation for all necessary planning steps. Finally, the arena of time illustrates how collaboration is influenced at the micro level by overarching time constraints (Hoppe Citation2011, 175) and must therefore be designed around them. The identification of potential impediments to alternative routes for the electricity line, such as breeding or hatching sites, was only possible during specific months, and thus profoundly influenced the schedule of the collaborative arrangement.

The arenas are analytically separated but tightly interconnected: In the case of an on-site visit, for example, the choice of a specific setting (i.e. site visits) also influenced the forms of interaction that facilitators wanted to generate and the (local) expertise they intended to mobilize. Also, each of these design choices is subordinated to the underpinning purpose of the arrangement, set by the agenda arena, and contributes to support it: for instance, the collaborative planning of a new route for a high-voltage electricity line (agenda) was realized through workshops designed to enable productive communicative interactions among selected actors – holding different kinds of expertise – to deliver specific results.

Tracking flows of power

Mapping the choices of a designed interaction order, however, does not reveal the ways in which participants potentially challenge and transform arenas for power over the course of the collaboration, thus changing conveners’ and facilitators’ original plans. The framework proposes the analytical concept of flows of power to capture the subtle dynamics through which a designed interaction order is constantly being assembled, disassembled, and reassembled.

In particular, the framework distinguishes between reinforcing, modifying, and departing flows of power. In this, it builds on Castells’ (Citation2011) and Schatzki’s (Citation2002) illustrations of the underlying dynamics in a practice’s development.Footnote5 Reinforcement refers to a power flow that reasserts the original design choices of a certain arena. Modification alludes to a power flow that integrates new meanings without fundamentally changing the nature of the arena. Finally, departing flows of power imply fundamental change within the arena. To illustrate: In the present case, an oft-discussed scenario (which ultimately did not materialize but can quickly highlight the three types of flow) was the emergence of a separate forum set up by a local citizen initiative to more fundamentally discuss what kind of energy transition citizens might wish for (e.g. a decentralized and local approach to energy generation, which would eliminate the need for cross-country high-voltage lines). Through such an act of power, namely choosing to discuss the if and not the how of a new electricity line, a citizen initiative would emancipate itself from the dominant rationale of the agenda arena and generate its own forum of discussion. The interaction between this initial act of power and the responses of conveners and other actors might have resulted in three different power flows:

Reinforcement: the conveners’ team, responding to this act, may give an interview via a prominent media channel, presenting legal decisions and data to emphasize the futility of discussing the if question, and accusing the citizen initiative of disseminating misinformation in this regard. This would seek to discredit the actions of the citizen initiative and reinstate the current agenda.

Modification: conveners may decide to integrate the hotly debated ‘if question’ into the next event and invite representatives of the citizen initiative to present their views on the topic. This negotiation within the agenda arena would lead conveners to at least explain in detail why a new high-voltage line is indeed considered necessary.

Departing: despite the conveners’ attempts to co-opt the initiative, the parallel forum may gain attention from the media and other participating actors, mobilize a critical mass that radically questions the nature of the agenda of the collaborative arrangement, and hence boycott it.

While the first two cases are likely to reproduce choices consistent with the designed interaction order, the departing flow of power challenges the very nature of the agenda arena and causes a moment of collaborative impasse in the official collaborative exercise, by discrediting its rationale. An analysis of this last flow with a process-oriented approach focuses on the chains of actions that an initial act of power – the citizen initiative starting its own forum of discussion – sets off. It establishes connections among concrete instances at the micro level which might have substantial effects on the course of collaboration – as the next section shows.

Applying the framework to understand collaborative impasse

The author’s field notes, which begin the Materials and methods section, illustrate a moment of collaborative impasse in which a citizen initiative questioned the very basis of the collaboration after its conclusions had been delivered. In this section, I illustrate how the analytical concepts proposed by the framework – arenas for power and flows of power – can support the analysis of this episode, by zooming in (Nicolini Citation2009) on this exemplar (Flyvbjerg Citation2006b). The investigation shows that this moment of collaborative impasse had its origin in the very beginning of the collaboration.

During the first public event of the collaborative planning process, conveners displayed a large map depicting the geographical space within which participants were invited to develop alternative corridors for the electricity line. This map also showed possible solutions previously identified by experts. Initially, the map, like the public event itself, had a purely informative aim. However, during the event, citizens standing in front of this map suddenly began drawing potential corridors outside of the originally delineated area. Researchers and employees of the electricity company were initially surprised by this emerging interaction order but permitted, and subsequently even encouraged, participants to draw their ideas on the map. During the follow-up conference call among the conveners’ team, the project leader of the electricity company decided after some discussion to take these proposals into account. An initial expert assessment found that some of the citizens’ suggestions were indeed valid.

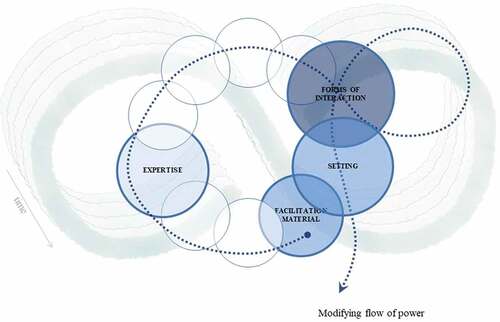

If we take a step back and employ the framework, we observe a modifying flow of power that starts in the facilitation material arena of the process design: Citizens turned the initially informative function of a map into an active tool to integrate their perspectives into the planning process and shifted the informative character of the public event to a deliberative one. This intervention established a precedent for how local knowledge (expertise) could meaningfully contribute to the highly complex planning process and modified the forms of interaction foreseen by the process design between experts and citizens on that occasion. Furthermore, it substantially enlarged the geographical space (setting arena) of the collaborative arrangement. By augmenting the dimensions of the involved arenas, as visualized in , the framework tracks the arenas in which the interplay between designed and emerging interaction orders takes place at a certain time during the process.

Figure 3. Visualization of the arenas (facilitation material, expertise, forms of interaction, and setting) involved in a modifying flow of power during and immediately after the first public event of the collaborative process.

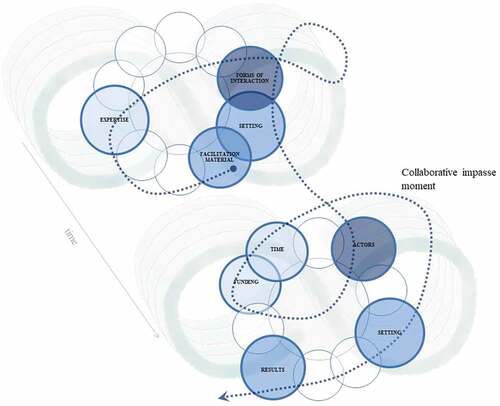

Figure 4. Tracking the long-term effects of a flow of power, originating in the facilitation material arena and culminating in a collaborative impasse moment in the results arena.

However, the story became even more complex. The decision by conveners to consider the new alternative courses as viable also implied the need to include more potentially affected citizens, local organizations, and political actors (actors). Time pressure, scarce knowledge of local networks, and lack of funding to properly inform new potentially affected actors led to a poor recruitment strategy. Feeling overwhelmed by the expanding geographical space to be considered in the collaborative planning process, both in terms of the substantial financial costs of evaluating additional candidate routes across a larger geographical area, and of the logistical efforts involved in recruiting newly affected actors, the conveners decided to set definitive limits to the geographical space (setting) in which alternative corridors could be developed, and hence ceased actively recruiting additional participants. This led to the moment described at the beginning of this section: Some months later, after the results of the collaborative exercise had been submitted to local authorities, a new citizen initiative was founded. It lamented the fact that, although one of the submitted alternative courses would run through its territory, locals had not been invited to join the planning process. Therefore, they questioned the legitimacy of the collaborative arrangement and the approach undertaken to achieve its results. This instance of collaborative impasse, visualized in , can be traced back to a design choice in the facilitation material arena at the very beginning of the collaborative process.

This example illustrates a retrospective analysis (Langley Citation1999) of a selected flow of power that led to an episode of collaborative impasse, by:

Identifying the act of power at the origin of the flow and the arena in which it was located;

Tracing how conveners, facilitators, and participants responded to this act of power over time (emerging interaction orders), while identifying which arenas were modified over time (designed interaction order), and assessing the type of flow of power (reinforcing, modifying, departing) that affected them;

Identifying the arena in which collaborative impasse took place.

The analysis of this episode shows three main contributions of the concept of flows of power to understand the performances of collaborative governance. First, the investigation of a flow of power explains why the collaborative arrangement looks as it does at a given stage of the process. A basic yet crucial observation in this episode is that flows of power originating in one arena (facilitation material) unfold and reverberate in other arenas (expertise, forms of interaction, setting), and can have substantial effects in yet others (results): The origin of the foundation of a citizen initiative fundamentally criticizing and discrediting the whole collaborative arrangement at its very end can be traced back to the conveners’ decision to let participants draw new lines on a map. Even though these two events have apparently little in common, the analysis of the flow of power illustrates the chain of actions connecting them: The enlargement of the geographical space; new affected actors; lack of resources for proper inclusion in the newly expanded planning process. Changes in one arena (in this case, the setting) drive reactions in others; similarly to an engine – once one component is set in motion, so are all others to varying degrees.

Second, the analysis of a flow of power uncovers the choices that conveners and facilitators had to take at every crossroads appearing along the collaborative path, and the resulting consequences. Collaborative impasse can be traced back to the moment in which the original designed interaction order, based on calibrated and interrelated design choices (e.g. a maximum number of 20 participants in the planning workshops, in order to enable productive communicative interactions to deliver detailed results) is modified through the conveners’ decision to enlarge the geographical space. At that time, conveners could not probably imagine all the changes that this would have implied: new participants joining the planning workshop, thus undermining the possibility of undertaking complex and detailed work in small groups; new financial resources and more time required to evaluate additional candidate routes, thus challenging the established budget and timeline for the collaboration; new citizens to engage, while lacking knowledge of local networks that could support the recruiting strategy. In contrast to the predictable mechanical movements of an engine, a change of course in a collaborative arrangement depends on a multitude of factors over which conveners and facilitators lack control.

This leads to a third consideration: Flows of power make visible the fine-grained work performed by the conveners and facilitators throughout the collaboration, and the thin line that separates collaborative advantage from impasse. On the one side, their ‘capacity to adapt the nature, tone, and conditions of the conversation to the needs of the situation at hand’ (Bartels Citation2012, 657) plays a crucial role in adjusting their initial choices and nurturing the generative side of collaboration, while encouraging emerging interaction orders (e.g. citizens drawing on the maps) to shape the path with new perspectives. On the other side, conveners and facilitators – confronted by modifying and departing flows which substantially alter the nature of the arrangement – are called to question whether the changes brought to the table are aligned with the original purpose of the collaboration and whether they, being responsible for the collaboration, can secure the necessary resources to continue supporting the process. The illustrated example showed that the decision to enlarge the geographical space went beyond the conveners’ capacities and risked delegitimizing the results achieved.

Discussion

What kind of analysis can be relevant to understanding collaborative governance’s performance? The present article argues that a dynamic investigation of the manifold ways in which power manifests, operates, and unfolds in collaboration at the micro level can hold important insights into ‘how [collaboration] works and whether it lives up to its promise’ (Gash Citation2016, 454). To substantiate this argument, the article developed a framework for this scope and showed that a process-oriented analysis can support an in-depth understanding of instances of collaborative impasse. Such work builds on studies on democratic innovations (Escobar Citation2015, Citation2019), organization studies (Weick Citation1995; Langley Citation1999), and studies proposing an interpretative approach in public policy (Bartels Citation2014; Cook and Wagenaar Citation2012), which suggest a ‘process sensitivity’ to investigations of the ‘ongoing, dynamic and evolving nature’ of collaborative arrangements (Vandenbussche, Edelenbos, and Eshuis Citation2020, 1). It is indeed in its process-sensitivity that the strength of this framework lays. While major efforts in the literature have succeeded in identifying at the theoretical level those factors and conditions that influence the design of collaborative arrangement (Ansell and Gash Citation2008; Bobbio Citation2019; Bryson et al. Citation2013; Purdy Citation2012), the present study advances their application at the empirical level. It does so by providing researchers with conceptual entry points to refer to while observing and making sense of the tight bundle of interventions used by actors throughout the collaboration. The concept of flows of power invites researchers to focus on collaboration’s porous character (Escobar Citation2019) and the manifold opportunities for its participants to shape it.

Focusing on the micro level of collaborative governance can be overwhelming, both for its practice and analysis. From a practice viewpoint, the illustrated example shows the myriad pitfalls and challenges that those responsible for the collaboration might encounter during the process. At the same time, it also strengthens the argument that collaboration is not ‘self-generating’ (Levine, Fung, and Gastil Citation2005, 3) and that the craft of engaging the public requires an ‘extremely sophisticated’ (Lee Citation2015, 224) expertise (see also Escobar Citation2019; Molinengo, Stasiak, and Freeth Citation2021). From an analytical perspective, questions may arise concerning the transferability of this framework to studying collaboration in other contexts. The robustness of the framework stems from combining an in-depth analysis of a case study with iterative rounds in other collaborative contexts (cf. Molinengo and Stasiak Citation2020), member-checking strategies (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow Citation2012), and the author’s experiences as practitioner in the field. The present article has illustrated a retrospective application (Langley Citation1999) of the framework to a case study, which relied on the researchers’ immersion in the context, combined with interviews and a rich variety of longitudinal data from multiple sources. There are, however, various other ways to apply the framework in other contexts. The most conservative application would expect researchers to use the framework as a conceptual map, structuring their fieldwork along the collaborative process. The idea would not be to identify every act of power (and its consequent flow) along the collaborative process, but to sensitize researchers to detect and analyze changes taking place in specific arenas at a specific time in the process. Another approach could be to focus the data-gathering strategy on moments of collaborative impasse as ‘occasions for sensemaking’ (Weick Citation1995, 86) and to pay attention to the design choices conveners and facilitators make in dealing with these instances. Researchers might also undertake a narrative approach (Langley Citation1999) and use the framework as an interview guide with conveners, facilitators, and participants to reconstruct the flows of power that led to collaborative impasse according to their viewpoint. Finally, an adapted version of the framework for the work of practitioners might serve as a guide for conveners and facilitators to reflect on their own design choices, identify moments of collaborative impasse, and the dynamics that may have led to them. These examples show that the analytical concepts provided by the framework can be used flexibly, depending on the focus of those employing it. Nevertheless, all share a common approach: tracking flows of power across arenas over time, to investigate moments of collaborative impasse.

Conclusion

In contrast to the critique of Dewulf and Elbers (Citation2018, 2) that analytical models for investigating power ‘remain at a high level of abstraction making them less useful for empirical research,’ the present work undertook the challenge of generating a theoretical framework grounded in and emerging from practice, connecting it with different strands of the literature, in order to produce empirical work tied to the daily practice of conveners, facilitators, and participants in collaborative settings.

While the focus is on the tangled bundle of acts and flows of power taking place throughout the collaboration, the approach proposed by the framework is of wider scope. Collaborative exercises are subject to coercive trends if hidden agendas are ignored (Mouffe Citation1999; Rubinstein, Sanchez, and Lane Citation2018; Sanders Citation1997; Young Citation2001), and can quickly turn into a new strategy for strengthening particularistic interests (Walker, McQuarrie, and Lee Citation2015, 8). The proposed framework challenges this tendency and encourages a fine-grained perspective on power that remains close to its micropolitics. Only by closely examining power may we be able to critically scrutinize forms of collaboration that, either more or less overtly, exclude relevant voices (Dalton Citation2017) and exacerbate power inequalities, which in turn foster or reinforce other inequalities in society (Lee, McQuarrie, and Walker Citation2015).

The framework also underlines the importance of facilitators’ and conveners’ work in constantly rebalancing and reconsidering design choices when confronted with the realities of collaborative practices. Once the designed interaction order is out in the world, it is their task to observe emerging interaction orders and, when faced with a change to the original plan, to balance out the different design choices connected to this change. Without such adjustments, there is the risk that conflicting goals of different arenas within the process design may clash with each other and lead to impasse. The present paper aims to make a first theoretical step towards informing the design of more power-sensitive collaborative processes and is open to scrutiny and development.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the invaluable feedback of Oliver Escobar, Patrizia Nanz, Frank Fischer, Rebecca Freeth, Graham Smith, and Mike Palmer to earlier versions of this paper. My colleagues involved in the research projects ‘Co-creation in Democratic Practice’ and ‘Politicizing the Future’ have been a fundamental support in the writing process. The work in 2014–2016 with Mathis Danelzik, Ina Richter, and Anja Baukloh formed the basis of this article. I thank all the participants, facilitators, and conveners who participated in and committed to this research. I owe a special intellectual debt to Achim Goeres, to whose memory this article is dedicated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Disclaimer

The article represents the views of the author and is the product of research conducted prior to the author's employement at the German Federal Office for the Safety of Nuclear Waste Management. It neither represents the official positions of the Federal Office, nor those of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection, nor those of any staff members at these institutions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Giulia Molinengo

Giulia Molinengo writes her PhD at the University of Potsdam and is affiliate scholar at the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) Potsdam. Her research focuses on the micropolitics of collaborative governance, process expertise, collaborative policy advice, and transformative research. Since February 2022 she works as a policy officer at the Federal Office for the Safety of Nuclear Waste Management in Berlin, Germany.

Notes

1. Schatzki defines a chain of action as ‘a series of actions, each member of which is a response either to the immediately preceding member or to an event or change that the immediately preceding member brought about in the world’ (2002, 148–149).

2. In this paper the concepts of ‘flow of power’ and ‘power dynamic’ are used interchangeably. In certain instances, the term ‘flow of power’ is used to distinguish this from ‘acts of power.’

3. German law ‘encourages’ electricity companies active in the field of energy transition strategies to include citizens in the planning process, but does not foresee any formal delegation of decision-making competence to the local population.

4. In the first locality 700 citizens, randomly selected from the local registry, were invited by letter to apply to join the planning group. In the second locality the TSO issued an open invitation to the entire population. Applicants could contact a callcentre run by professional facilitators. Participants were selected from the applicants by lottery, aiming to ensure representation according to residence (localities were divided into sectors), gender, and age.

5. While Castells (2011, 15) identifies two opposite dynamics that follow an act of power, namely a ‘change’ or a ‘reinstatement’ of prior structures, Schatzki introduces – next to ‘maintenance’ (Castells’ reinstatement) – a nuance between ‘recomposition’ and ‘reorganization’. In recomposition, only some aspects of a practice are changed, while reorganization implies a more fundamental change in the nature of the practice itself (2002, 240–242).

References

- Ansell, C. 2012. “Collaborative Governance.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance, edited by D. Levi-Faur, 454–467. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2008. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4): 543–571. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Ansell, C., and J. Torfing. 2018. How Does Collaborative Governance Scale? New Perspectives in Policy and Politics. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Arendt, H. 1970. On Violence. London: Penguin Press.

- Avelino, F. 2011. Power in Transition. Empowering Discourses on Sustainability Transitions. Rotterdam: Wöhrmann Print Services.

- Bacharach, S. B., and E. J. Lawler. 1980. Power and Politics in Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bachrach, P., and M. S. Baratz. 1962. “The Two Faces of Power.” American Political Science Review 56 (4): 941–952. doi:10.2307/1952796.

- Bartels, K. P. R. 2012. “The Actionable Researcher.” Administrative Theory and Praxis 34 (3): 433–455. doi:10.2753/ATP1084-1806340306.

- Bartels, K. P. R. 2014. “Communicative Capacity.” The American Review of Public Administration 44 (6): 656–674. doi:10.1177/0275074013478152.

- Blue, G., and J. Dale. 2016. “Framing and Power in Public Deliberation with Climate Change: Critical Reflections on the Role of Deliberative Practitioners.” Journal of Public Deliberation 12 (1). Article 2.

- Bobbio, L. 2019. “Designing Effective Public Participation.” Policy and Society 38 (1): 41–57. doi:10.1080/14494035.2018.1511193.

- Bryson, J. M., K. S. Quick, C. S. Slotterback, and B. C. Crosby. 2013. “Designing Public Participation Processes.” Public Administration Review 73 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02678.x.

- Castells, M. 2011. Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Collins, R. 2005. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton Studies in Cultural Sociology. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cook, S. D. N., and J. S. Brown. 1999. “Bridging Epistemologies: The Generative Dance between Organizational Knowledge and Organizational Knowing.” Organization Science 10 (4): 381–400. doi:10.1287/orsc.10.4.381.

- Cook, S. N., and H. Wagenaar. 2012. “Navigating the Eternally Unfolding Present.” The American Review of Public Administration 42 (1): 3–38. doi:10.1177/0275074011407404.

- Dahl, R. A. 1957. “The Concept of Power.” Systems Research and Behavioural Science 2: 201–215.

- Dalton, R. J. 2017. The Participation Gap: Social Status and Political Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- de Souza Briggs, X. 1998. “Doing Democracy Up-Close: Culture, Power, and Communication in Community Building.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 18 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1177/0739456X9801800101.

- Dewulf, A., and W. Elbers. 2018. “Power in and over Cross-Sector Partnerships: Actor Strategies for Shaping Collective Decisions.” Administrative Sciences 8 (3): 43. doi:10.3390/admsci8030043.

- Dryzek, J. S. 2001. “Legitimacy and Economy in Deliberative Democracy.” Political Theory 29 (5): 651–669. doi:10.1177/0090591701029005003.

- Escobar, O. 2015. “Scripting Deliberative Policy-Making: Dramaturgic Policy Analysis and Engagement Know-How.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 17 (3): 269–285.

- Escobar, O. 2019. “Facilitators: The Micropolitics of Public Participation and Deliberation.” In Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, edited by S. Elstub and O. Escobar, 178–195. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Felt, U., and M. Fochler. 2010. “Machineries for Making Publics: Inscribing and De-Scribing Publics in Public Engagement.” Minerva 48 (3): 219–238. doi:10.1007/s11024-010-9155-x.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2002. “Bringing Power to Planning Research: One Researcher’s Praxis Story.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 21 (4): 353–366. doi:10.1177/0739456X0202100401.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006a. “Making Organization Research Matter: Power, Values and Phronesis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Organization Studies, edited by S. Glegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, and W. R. Nord, 370–387, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006b. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. 1st American ed. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Freeman, R., and S. Sturdy, eds. 2014. Knowledge in Policy: Embodied, Inscribed, Enacted. Bristol: Policy Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt9qgztx.

- Fung, A. 2003. “Survey Article: Recipes for Public Spheres: Eight Institutional Design Choices and Their Consequences.” Journal of Political Philosophy 11 (3): 338–367. doi:10.1111/1467-9760.00181.

- Fung, A. 2005. “Deliberation before the Revolution: Toward an Ethics of Deliberative Democracy in an Unjust World.” Political Theory 33 (3): 397–419. doi:10.1177/0090591704271990.

- Gash, A. 2016. “Collaborative Governance.” In Handbook on Theories of Governance, edited by C. Ansell, and J. Torfing, 454–467. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi:10.4337/9781782548508.00049.

- Geertz, C. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Goffman, E. 1959. “The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.” In The Goffman Reader, edited by C. Lemert, and A. Branaman, 21–26, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Goffman, E. 1983. “The Interaction Order: American Sociological Association, 1982 Presidential Address.” American Sociological Review 48 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/2095141.

- Hajer, M. A. 2005. “Setting the Stage.” Administration and Society 36 (6): 624–647. doi:10.1177/0095399704270586.

- Hardy, C., and N. Phillips. 1998. “Strategies of Engagement: Lessons from the Critical Examination of Collaboration and Conflict in an Interorganizational Domain.” Organization Science 9 (2): 217–230. doi:10.1287/orsc.9.2.217.

- Haug, C., D. Rucht, and S. Teune. 2013. “A Methodology for Studying Democracy and Power in Group Meetings.” In Meeting Democracy, edited by D. Della Porta and D. Rucht, 23–46. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Herberg, J. 2020. “Control before Collaborative Research – Why Phase Zero Is Not Co-Designed but Scripted.” Social Epistemology 3: 1–13.

- Hoppe, R. 2011. “Institutional Constraints and Practical Problems in Deliberative and Participatory Policy Making.” Policy and Politics 39 (2): 163–186. doi:10.1332/030557310X519650.

- Huxham, C. 1996. “Advantage or Inertia? Making Collaboration Work.” In The New Management Reader, edited by R. Paton, G. Clark, and G. Jones, 238–254. London: Routledge.

- Huxham, C., and N. Beech. 2008. “Inter-Organizational Power.” In The Oxford Handbook of Inter-Organizational Relations, edited by S. Cropper, C. Huxham, M. Ebers, and P. S. Ring, 555–579. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Innes, J. E., and D. E. Booher. 2015. “A Turning Point for Planning Theory?: Overcoming Dividing Discourses.” Planning Theory 14 (2): 195–213. doi:10.1177/1473095213519356.

- Kadlec, A., and W. Friedman. 2007. “Deliberative Democracy and the Problem of Power.” Journal of Public Deliberation 3 (1). Article 8.

- Langley, A. 1999. “Strategies for Theorizing from Process Data.” The Academy of Management Review 24 (4): 691. doi:10.5465/amr.1999.2553248.

- Langley, A., C. Smallman, H. Tsoukas, and A. H. van de Ven. 2013. “Process Studies of Change in Organization and Management: Unveiling Temporality, Activity, and Flow.” The Academy of Management Journal 56 (1): 1–13. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.4001.

- Lee C. W. 2015. Do-it-yourself democracy: The rise of the public engagement industry. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Lee, C. W., M. McQuarrie, and E. T. Walker, eds. 2015. Democratizing Inequalities: Dilemmas of the New Public Participation. New York: New York University Press.

- Levine, P., A. Fung, and J. Gastil. 2005. “Future Directions for Public Deliberation.” Journal of Public Deliberation 1 1 . Article 3

- Lukes, S. 2005. Power: A Radical View. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Marshall, N., and J. Rollinson. 2004. “Maybe Bacon Had a Point: The Politics of Interpretation in Collective Sensemaking.” British Journal of Management 15 (S1): 71–86. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2004.00407.x.

- Molinengo, G., and D. Stasiak. 2020. “Scripting, Situating, and Supervising. The Role of Artefacts in Collaborative Practices”. Sustainability, 12 (16): 6407

- Molinengo, G., Stasiak, D., and R. Freeth. 2021. “Process expertise in policy advice. Designing collaboration in collaboration”. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8 (310): 1–12.

- Morley, L. 2006. “Hidden Transcripts: The Micropolitics of Gender in Commonwealth Universities.” Women’s Studies International Forum 29 (6): 543–551. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2006.10.007.

- Mouffe, C. 1999. “Deliberative Democracy or Agonistic Pluralism?” Social Research 66 (3): 745–758.

- Nicolini, D. 2009. “Zooming in and Out: Studying Practices by Switching Theoretical Lenses and Trailing Connections.” Organization Studies 30 (12): 1391–1418. doi:10.1177/0170840609349875.

- Purdy, J. M. 2012. “A Framework for Assessing Power in Collaborative Governance Processes.” Public Administration Review 72 (3): 409–417. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02525.x.

- Rubinstein, R. A., S. Sanchez, and S. Lane. 2018. “Coercing Consensus? Notes on Power and the Hegemony of Collaboration.” In Conflict and Collaboration: For Better or Worse. Routledge Studies in Security and Conflict Management, edited by C. Gerard, and L. Kriesberg, 104–119, London: Routledge.

- Sanders, L. M. 1997. “Against Deliberation.” Political Theory 25 (3): 347–376. doi:10.1177/0090591797025003002.

- Schatzki, T. R. 2002. The Site of the Social: A Philosophical Account of the Constitution of Social Life and Change. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Schwartz-Shea, P., and D. Yanow. 2012. Interpretive Research Design: Concepts and Processes. Routledge Series on Interpretive Methods. New York: Routledge.

- Tello-Rozas, S., M. Pozzebon, and C. Mailhot. 2015. “Uncovering Micro-Practices and Pathways of Engagement that Scale up Social-Driven Collaborations: A Practice View of Power.” Journal of Management Studies 52 (8): 1064–1096. doi:10.1111/joms.12148.

- van der Arend, S., and J. Behagel. 2011. “What Participants Do. A Practice Based Approach to Public Participation in Two Policy Fields.” Critical Policy Studies 5 (2): 169–186. doi:10.1080/19460171.2011.576529.

- Vandenbussche, L., J. Edelenbos, and J. Eshuis. 2020. “Plunging into the Process: Methodological Reflections on a Process-Oriented Study of Stakeholders’ Relating Dynamics.” Critical Policy Studies 14 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/19460171.2018.1488596.

- Walker, E. T., M. McQuarrie, and C. W. Lee. 2015. “Rising Participation and Declining Democracy.” In Democratizing Inequalities: Dilemmas of the New Public Participation, edited by C. W. Lee, M. McQuarrie, and E. T. Walker, 3–26. New York: New York University Press.

- Weick, K. E. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations. London: Sage Publications.

- Weick, K. E. 2001. Making Sense of the Organization. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Young, I. M. 2001. “Activist Challenges to Deliberative Democracy.” Political Theory 29 (5): 670–690. doi:10.1177/0090591701029005004.