ABSTRACT

This article examines multilingual interactions in an upper secondary Language Introduction Programme (LIP) classroom in Sweden. The LIPs, highly affected by both glocal linguistic and cultural diversity and the monolingual-monocultural habitus of the surrounding society, offer recently arrived immigrant youth (ages 16–19) education where emphasis is on the majority language of the surrounding society, Swedish, but where teaching can also include other subjects. The study stems from a larger ethnographically framed project, which aims at both creating new knowledge on translanguaging as a pedagogical practice as well as contributing to school development. The paper has a threefold focus. First, it examines everyday multilingual languaging among the participants. Second, it discusses their doing of language policy from a practiced perspective. Third, it reflects upon the implementation process of translanguaging as a pedagogical practice. Data in the study includes video and audio recordings of classroom interactions, fieldnotes, literacy and interview data. Micro-analyses of interactional data are employed in order to discuss the ways in which students and teachers engage in (trans)languaging and language policing processes. Finally, the tension between seeking to teach and learn through linguistic diversity and participants’ understandings of what kind of languaging is appropriate is critically reflected upon.

Introduction

Across Europe and all over the world, the number of multilingual students in schools is currently rising and this increase has led to the investigation of educational models for this group. Yet, as Duarte (Citation2018) has pointed out, migration-induced multilingualism and language mixing practices have seldom been acknowledged as resources for learning and instruction within many classrooms due to the monolingual self-understanding of European nation-states. At the same time, an increasing body of literature points towards a growth in the implementation of pedagogical practices that encourage the active inclusion of students’ family and heritage languages (Cenoz Citation2017; Creese and Blackledge Citation2015; García Citation2009). Based on the idea that students and teachers bring diverse linguistic knowledge that can actively be used as a resource for learning, a recent trend regarding (language) teaching and learning has been termed the multilingual turn in (language) education (Conteh and Meier Citation2014). Ideas emphasizing a more heteroglossic perspective of multilingual use and behaviour have led to several scholars suggesting the term translanguaging as a way of i) describing multilingual practices that include ‘the full range of linguistic resources’ and ii) a proposal of a pedagogical approach in which multilingual practices are systematically used in instruction and learning (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2017; García, Johnson, and Seltzer Citation2017). Within translanguaging perspective, the difference between named languages and the language system or mental grammar of multilingual speakers is emphasised, and language use is recognised as dynamic and fluid beyond the socially and politically defined boundaries of languages (García and Li Citation2014; Otheguy, García, and Reid Citation2015).

Within the geopolitical space of Sweden, issues coupled with schooling and migration have received plenty of attention both in public discourse and academic research. In recent years, political debates and policy documents, school developmental work supported by Swedish national educational agencies as well as academic research concerning this field have focused largely on newly arrived (students).Footnote1 In fact, this concept has overshadowed many previously used ones (e.g. migrant students, multilingual students), but its implications have not really been contested by most actors who use it (Bagga-Gupta and Messina Dahlberg Citation2018). A particular group of ‘newly arrived students’ whose education has been of interest for different stakeholders, are young people who have migrated to Sweden in their late teens (16–19-year-olds), and who in the Swedish educational system belong to upper secondary school (gymnasium). For this group of students who are not eligible for national upper secondary school programmes, education is most often offered within the Language Introduction Programme (LIP). The LIP is, at best, an individually adapted temporary educational route, and functions as a foundation for further education or establishment on the labour market (Skolverket Citation2015, Citation2016).

For teachers engaged in the education of multilingual and migrant students in Northern contexts (both within LIPs and other forms of schooling), interest in translanguaging has expanded during the recent years. This is reflected in the increase of both academic publications and scientific conferences and networks, as well as practitioners’ reflections concerning the implementation of translanguaging in teaching and learning (Svensson Citation2017; Paulsrud et al. Citation2017). The present study, reporting from a research and school development project where such implementation was central, contributes to the expanding body of scholarly literature on translanguaging. As suggested by Otheguy, García, and Reid (Citation2015, 281), translanguaging can be ‘of special relevance to schools interested in the linguistic and intellectual growth of bilingual students’. In Northern contexts, the theoretical and pedagogical dimensions of translanguaging have been interpreted as involving all students and all teachers, moving from strictly bilingual to multilingual and mainstream education (Paulsrud et al. Citation2017, 16). The authors furthermore point out that translanguaging ‘evokes questions about the skills used and needed for working as a teacher in the 21st century’ (ibid.).

Challenging top-down infused (monolingual) ideologies and norms, as well as language policies, often needs to be a bottom-up process. Here, ideology, practice and pedagogy are inherently intertwined – one cannot simply evolve without the evolution of the others. In a pedagogical sense, translanguaging raises questions of whether or not and in what ways diverse students’ linguistic experiences and skills are recognized and supported in mainstream schools – and how do educators contribute to the empowerment of their students. Moreover, a pedagogy of translanguaging concerns language ideologies of both students and teachers as it challenges the existing hierarchies of language policy and practices and opens potentially up for new ways of languaging in educational settings (Creese and Blackledge Citation2015; García and Li Citation2014; Paulsrud et al. Citation2017).

Purpose and aims

In the intersection of the monolingual/monocultural habitus of the surrounding society and its educational system and the linguistic and cultural diversity among the participants in the LIP, the overall purpose of this study is to examine the implementation process of translanguaging as a pedagogical practice as well as the processes of everyday language policing that accompanies this implementation. Thus, the present study has a threefold focus:

First, it seeks to examine everyday (trans)languaging among teachers and students, in particular, their engagement with languaging practices in teaching and learning.

Secondly, the study discusses the participants’ doing of language policy, i.e. the everyday practices highlighting normative ideas of named languages and languaging within the LIP setting.

Thirdly, it critically reflects upon the implementation process of translanguaging as a pedagogical practice.

Theoretical background and previous research

(Trans)languaging as theory and pedagogy

A scholarly understanding of translanguaging, as many related concepts, has gone through a metamorphosis or perhaps a pendulum movement over the recent decades. The interpretation of translanguaging has ranged from its original meaning trawsiethu (Williams Citation1996), referring to educational practices in bilingual classrooms where the input and output of teaching and learning alternated between English and Welsh, to a broader view of translanguaging as individuals’ capability of drawing upon their full linguistic repertoire (García Citation2009) to discursive languaging practices in which human beings engage in order to gain knowledge (Li Citation2011). Subsequently, Svensson (Citation2017) concludes that contemporary scholarly work concerning translanguaging can be divided to at least five different perspectives, which include universal, individual, educational, social and neurolinguistic perspectives.

In a recent study, Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2017) bring together the original use of translanguaging as a specific pedagogical strategy and its broader use as discursive practices when they distinguish between pedagogical and spontaneous translanguaging. Of these, spontaneous translanguaging refers to an individual’s ability to use their full linguistic repertoire and fluid discursive practices that can take place inside and outside the classroom and relates to reconceptualizing language as multilingual, -modal, and -sensory system of meaning-making resources that transcends conventional boundaries between languages. Pedagogical translanguaging, on the other hand, is planned by the teacher inside the classroom and can refer to the use of different languages for input and output or to other planned strategies based on the use of students’ resources from their whole linguistic repertoires. The present study draws mainly on translanguaging as a pedagogical practice. This is in line with García and Li (Citation2014) who define translanguaging both as an act of performance and as a pedagogy for teaching and learning. What these definitions share is a main focus on the language user and on how languages are negotiated in interaction rather than language systems per se (Canagarajah Citation2011; García Citation2009). The tension between (trans)languaging and named languages and the difficulty of addressing languaging without labels have been discussed by many scholars (Gynne and Bagga-Gupta Citation2015; Turner and Lin Citation2017; Hult Citation2019). The present study is positioned in line with Turner and Lin who conclude that ‘by virtue of the “trans”, two or more […] positioned as central to translanguaging theory (Citation2017, 9)’. Consequently, I will use the labels traditionally appointed to named language categories such as ‘Dari’ or ‘Swedish’, and even ‘first languages/L1’ in the below analyses, while simultaneously acknowledging the fluid nature of (trans)languaging.

For educational systems catering for multilingual students, it has been claimed that translanguaging can provide a novel, ideological shift in SLA pedagogies. Here, it is also relevant to point out the two strategic principles of translanguaging which include social justice – a positive and encouraging attitude to all languages in the classroom as equally valuable sources of learning and knowledge development and social practice – not only when, but how to integrate L1s in learning in meaningful ways without lowering expectations on pupils (García Citation2009). As a result, it has been claimed, it is possible to implement a clear pedagogical strategy that is both sustainable and meaningful.

However, some scholarly voices participating in the discussion on fluidity and fixity in linguistic theory (Jaspers and Madsen Citation2018), have pointed out that the present focus on ‘multilingualism’/polylingualism/translanguaging is at many levels nothing new and that scholarly insights concerning the idea of autonomous languages being ‘useful but reductive’ have been a long-recognised problem within the sociolinguistic canon. (Jaspers and Madsen Citation2018). Their critical voices highlight the fact that linguistics have long attempted to tackle the challenges of ontologically understanding language as not the use of fixed codes but as meaning-making through describing human communication through action-oriented terms such as ‘languaging’ (Bagga-Gupta Citation2014; Jaspers and Madsen Citation2018). Furthermore, scholars (Bagga-Gupta Citation2017; Pavlenko Citation2018) have highlighted the fact that the promotion of translanguaging, polylingualism and similar phenomena as something ‘new’ can also be related to geopolitical aspects and dimensions of power and hegemony. What is ‘new’ about translanguaging in contemporary Global North are ‘normal conditions for languaging’ in both historical and contemporary Global South (Bagga-Gupta Citation2017). This brings about demands of being careful as to what and how we as scholars are to represent as extraordinary complexity in what we observe in our societies today – as our understanding of those complexities should be related to complexity elsewhere and before (Jaspers and Madsen Citation2018).

These criticisms are relevant and important, and concern indeed translanguaging and similar terms as theories of language/linguistic practice. In the present paper, however, the focus is on translanguaging as a pedagogical strategy as well as an educational practice based on ideologies promoting pedagogical transformation. Additionally, what is centre-staged here are the ways in which translanguaging refers to language actions that ‘enact a political process of a social and subjectivity formation which resists the asymmetries of power that language and other meaning-making codes, associated with one or another nationalist ideology, produce’ (García and Li Citation2014, 43). This is the backdrop from which languaging and language policy in practice in LIP classrooms are scrutinized in the present paper. This perspective highlights also the interdependence of speakers’, both teachers’ and students’ ideologies of language and the very interactions influenced by those ideologies, i.e. language policies in everyday practice (Creese and Blackledge Citation2010; Ganuza and Hedman Citation2017).

Practised language policy: ideologies and everyday practices

The second theoretical foundation of the study consists of the framework of Language Policy (LP) studies, more closely language policy as practice. There has been a shift in focus in LP studies in recent decades, from formal policies towards language users’ observable language behaviours and choices, meaning what people actually do when they language. In this perspective, LP is understood as enacted and locally adjusted. Therefore, any examination of policy in an institutional setting needs to take into consideration the interactional architecture of that institution, e.g. that of the classroom, in order to properly understand how it operates. In the context of the present study, it means examining how policy is enacted in interactions between students and teachers. Bonacina-Pugh (Citation2012; Bonacina-Pugh Citation2017) has argued that, beyond formal language policies, the interactional norms of language choice are what constitutes ‘a practised language policy’, in the sense that these norms inform speakers of what languages – or what kind of languaging is appropriate or not. Practised language policies are not a fixed set of norms, but interactional norms that are constantly ‘renegotiated, transformed or created every step of the way, at each language choice and alternation act’ (Bonacina-Pugh Citation2017, 10). Practised language policies, such as practicing translanguaging as a pedagogy, can thus play a key role in legitimising multililingual languaging.

Previous research has highlighted the relationship of translanguaging and language ideologies and language policy making in many ways. In the following, a few studies contributing to the present one are discussed. In their study on mother tongue instruction (MTI) in Sweden, Ganuza and Hedman (Citation2017) focused on ideologies of language and pedagogy as they were explicitly articulated by MTI teachers during interviews and informal conversations, as well as the embodiment of those ideologies in communicative practices during MTI lessons. Situating analyses of teachers’ articulated and embodied beliefs in a sociohistorical and political context entailed also discussing the historical foundation of the MTI in Sweden, as well as the subject’s possibilities and limitations in terms of policy and practice. In a study exploring the ideological implications of a translanguaging framework, Jonsson (Citation2017) points out how translanguaging has the potential to work against ideologies and policies of homonegeity in that it ‘represents ideologies in which different linguistic resources are acknowledged and valued’ (Jonsson Citation2017, 26) As such, it may work both overtly and covertly against both official and informal language policies. Striving for promoting translanguaging can thus be related to striving towards a polylingualism norm (Jørgensen Citation2008, 163) that allows for the use of any languages that the speaker commands, to a greater or lesser extent. This norm allows for more inclusive language practices, embracing both social practice and social justice dimensions of translanguaging, which in turn contributes to practised policies. As pointed out by many scholars, contestation of fixed norms is ideologically significant and can contribute to empowerment for the learners/speakers (Jonsson Citation2017, 28–29).

‘Newly arrived students’ and language introduction programmes in Sweden

The empirical setting of the study consists of a Language Introduction Programme (LIP) in a Swedish upper secondary school. During the academic year 2017–2018 when the study was initiated, the LIP was the fourth largest of Swedish upper secondary school programmes with approx. 20 000 pupils starting each year 1. The main aim of LIPs is to make it possible for newly arrived migrant students to progress to the national programmes/other forms of education/labour market. The LIP has a strong focus on the Swedish language and is planned based on an assessment of the pupil’s language knowledge in Swedish. The programme is, at its best, individually adapted and can include comprehensive or upper secondary school subjects (Skolverket Citation2015, Citation2016).

Various different actors within and beyond the field of formal schooling participate in the public discourse concerning the ‘newly arrived’ and the LIP in Sweden. Stakeholders participating in the debates range from researchers, politicians and officials to teachers and teacher unions. In the public discourse, the LIP has been referred to as a ‘waiting room’ (Lärarförbundet Citation2017), while scholars have referred to it as a ‘space in between’ or a ‘third space’ (Bomström Aho Citation2018). Student experiences of the LIP have been characterized as sometimes direct routes to further education, but more often ‘minor paths or stops’ (Hagström Citation2018), or similar to lower secondary school preparatory classes, even a parallel school system leading to a ‘postponed future’ for the students (Nilsson Folke Citation2017). All these aspects; waiting, in-betweenness and postponement have also been confirmed by the teachers participating in the present study. Furthermore, the Swedish Schools Inspectorate (Citation2017) has pointed out the difficulties students at LIPs in many schools have in reaching their expected goals (as formulated in individual study plans), which provides for yet another example of the increased need of critically examining the ways in which the education of multilingual students can be improved. Nevertheless, several scholars (Nilsson and Bunar Citation2016; Hagström Citation2018) have pointed out that both organisational solutions and pedagogical practices remain a challenge for educators in this field. It has been suggested that affirming values of multilingualism and multicultural relations and networks are essential for all students.

Drawing on post-migration ecology, sociocultural theory and critical phenomenology, Nilsson Folke (Citation2017) points out that introductory classes for migrant students, similar to the LIP in the present study, are often characterized by weak challenges and strong support. While findings from other scholars (Bomström Aho Citation2018; Hagström Citation2018) confirm the students’ experiences emphasizing the importance of the school as a social context, few recent studies highlight teachers’ perspectives when educating multilingual students. However, based on an interview study with teachers within a LIP, Torpsten (Citation2018) discusses some challenges in providing instruction and subject content and organising teaching and learning from a translanguaging perspective.

The study, materials and methods

The analyses presented below come from a research and school development project called (Trans)languaging as a resource in the classroom [(Trans)språkande som resurs i klassrummet], (2017–2019). The overarching aim of the project is to study students’ and teachers’ meaning making from a perspective that highlights their (potential) use of multilingual resources. A subsequent aim is to contribute to school development within the LIP through deliberately including and inviting students’ flexible language uses and translanguaging practices, i.e. through pedagogical translanguaging (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2017). The initial core issue examined was formulated as ‘How can a pedagogy of translanguaging be combined with general goals of the upper secondary school curriculum?’.

As mentioned above, in the Swedish educational field, both from educators’ and scholars’ perspective, there has been a growing interest towards the pedagogic potentials of translanguaging (cf. Paulsrud et al. Citation2017). Thus, in concordance with a team of 14 teachers and tutors within a LIP at a school located in an urban area in Central Sweden, the project was designed to expand teachers’ professional knowledge and improve their professional skills vis-á-vis translanguaging pedagogies, apart from constructing and exploring ethnographically based knowledge on translanguaging. As a sidetrack within the process, other interesting phenomena emerged and were explored, among them issues related to language ideologies and policy. The present study is thus based on ethnographic fieldwork and data from the academic year 2017–2018 from three different classrooms in two different levelsFootnote2 within the LIP.

After initial meetings where the purposes of both research and development parts of the project were presented and discussed with gatekeepers, information sheets were distributed to teachers and students, and permission was sought for further data creation. In phase 1, during the first seven months of the project, extensive ethnographic observations were made, when three key teachers, responsible for teaching English and Mathematics (Teacher 1), Natural Science (Teacher 2) and Swedish as a second language (Teacher 3), as well as their students, were followed. Both audio and video recordings were made in the four classrooms (27 lessons between 45 and 80 minutes, of which altogether 15 h were recorded) as well as during interviews with the teachers (three formal interviews and four documented group discussions in phase 2). I was also allowed access to the online learning platform that the LIP participants used. The number of pupils in the classrooms ranged from 8 to 18 for each classroom during the project and the first languages/languages of schooling of these altogether 28 emergent bilinguals included Dari, Farsi, Arabic, Somali, Tigrinya and Bosnian.

In phase 2, the ethnographic part of the project was followed by a school development part (8 months) in which the whole LIP teaching team of 14 persons, participated. The core of phase 2 was a series of group meetings, lectures and workshops that focused on translanguaging as a pedagogical practice. Between the meetings, the participating teachers explored and implemented ‘translanguaging strategies’ in their instructional practices, based on ideas promoted by García and Li (Citation2014, 166–167) in the Swedish translation of the book Translanguaging: language, bilingualism and education.

The teachers both documented those strategies and reported regularly to the group and the researcher who also acted as a facilitator during and between workshops. This part drew also on the CUNY-NYSIEB Translanguaging Guide for Educators (Celic and Seltzer Citation2013), and focused on collaborative descriptive inquiry regarding translanguaging pedagogies both as they were observed, documented and analysed by the researcher during the fieldwork as well as tried out by the teachers in their everyday practice during the second phase of the project.

The project data were thus created both through ethnographic fieldwork in which the researcher was a key actor (in this study represented by Extracts 1 and 2, –), as well as through the teachers (Extract 3ab). The present study draws on a Linguistic Ethnography approach (Shaw, Copland, and Snell Citation2015), wherein ethnographic insights have been ”tied down” (Rampton et al. Citation2004) through detailed, conversation analysis inspired examination of recorded multilingual interactions in the classrooms. Here, the linguistic features of conversational data are interpreted in relation to context of the interaction as well as the identities of the participants, with a particular focus on meaning-making processes (Gumperz Citation1982). Apart from examples taken from transcripts of video-recorded interactions, I make use of fieldnote and literacy data (both teaching materials and student texts) and photographs from the LIP classrooms in order to link the micro-level phenomena to complexities of modern life in diverse classrooms and beyond, through focusing on processes related to language ideologies and policing. These processes of ‘tying down’ and ‘opening up’ are what characterises linguistic ethnography (Rampton et al. Citation2004). Examples in the present study have been selected to illustrate partly the observed diversity of multilingualism in teaching and learning practices, partly the evolution of those practices over time. Moreover, they illustrate in different ways features of practised language policing, which was commonly occurring at the LIP. All examples referring to oral use of named languages are given in standard Latin ortography (Swedish in italics, Arabic or Dari in bold, English in regular typeface), with the original utterances in the interlocutors’ languages followed by a translation of that utterance to English on the following line (see Transcription key). Embodied actions are transcribed following some conventions from Mondada (Citation2016).

Findings – translanguaging and language policing in LIP classrooms

The first example is from an exchange between Teacher 1 and two students during a Mathematics class during phase 1 of the project the present study adheres to. This was documented through hand-written fieldnotes right in the beginning of the project when the teacher had, according to herself, somewhat superficial knowledge of what translanguaging as a pedagogy entailed. Teacher 1 was proficient in four (named) languages ranging from Swedish to Arabic, Assyrian and Kurdish. In an informal interview around the time of the observation, she stated that those linguistic experiences had helped her in incorporating a multilingual approach to interacting with students – which in many ways was as she had come to understand translanguaging. This morning the class is working with arithmetic in a task which compared different numbers of animals. Prior to the exchange, Teacher 1 has continuously reminded the students about the importance of i) speaking Swedish in the classroom and ii) thinking about the language of Maths.

Extract 1. Ants in maths 1 T1: Vet ni vad betyder ‘myror’? Kan ni på dari? På 2 arabiska? 3 Do you know what ‘ants’ means? Do you know in 4 Dari? In Arabic? 5 S1: ((says something inaudible in Dari)) 6 T1: *shows a photo of an ant via Google Photos* 7 Okej, kan ni saga nu vad det är på arabiska? 8 Ok, can you say now what it is in Arabic? 9 S2: namla 10 ant 11 T1: *nickar* Det där var rätt ord, inte det som du sade 12 innan 13 *nods* That was the right word, not what you said 14 earlier

The extract begins with the teacher initially checking the students’ understanding of a key concept in the task, asking whether they know what ‘myror/ants’ means – first (implicitly) in Swedish, then in Dari or Arabic. S1 suggests something that is inaudible for an observer, but that is registered by the teacher, who turns to her iPad, the screen of which is reflected on the whiteboard, and does a Google Photo search on ’myra’ (‘ant’). She then asks the Arabic speakers in the class again whether they can now say in Arabic what the image represents. S2 replies ‘namla/ant’, and the teacher confirms this by nodding and saying ‘That was the right word, not what you said earlier’, referring to what S1 had said in Dari a few moments earlier. The teacher then moves on to explaining what the other elements in the equation are and asking the students how it should be solved. From the students’ perspective, this short exchange is followed by a nearly inaudible discussions in their first languages, which are then quickly interrupted by the teacher who says ‘Vi ska inte prata arabiska!/We shall not speak Arabic!’ and then continues with her instruction in Swedish.

The above exchange can be examined from several different perspectives. First, it illustrates a moment of spontaneous translanguaging where different aural linguistic resources, Swedish, Dari and Arabic, become relevant in the meaning-making in that particular situation. Second, it could be relevant to say that, by simply inquiring what key concepts are in students’ L1s, Teacher 1 encourages them to engage in transferring knowledge between their linguistic resources. This can be identified as a scaffolding approach to help the students complete the task (Lewis, Jones, and Baker Citation2012). Third, what argues for a linguistically and multimodally inclusive view in the present situation, is the teacher’s use of multimodal resources such as digital images projected from the Internet in order to confirm and consolidate understanding of key concepts in students’ all languages. Thus, if studied through the lens of intentionally planned translanguaging practices, the teacher’s actions can be interpreted as trying to help pupils build on their background knowledge through translation, through bringing in some cross-linguistic transfer with the help of different visual and digital resources. On the other hand, while this and other teachers often used translation in instruction or asked the students to translate concepts from their L1s to L2 (see –) or vice versa, multilingual dialoguing was not truly encouraged in instruction during the first phase of the project. Moreover, as indicated by both the above dialogue and the teacher’s restrictive comment soon after the interaction, in large parts of the early observations of the LIP Maths classroom, the teacher was the main agent and conductor of interaction. It is through her instruction and by her permission that multilingual languaging becomes a reality – or not. There is evidence both at this instance and elsewhere towards the teachers’ signalling a relatively monolingual approach to potentially multilingual learning situations through practised language policing.

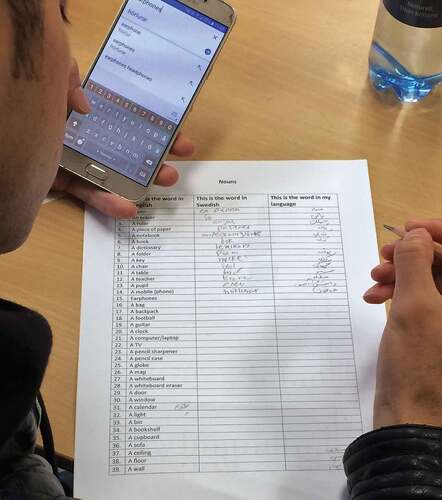

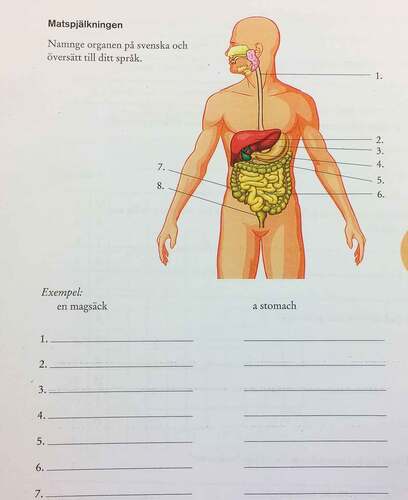

Canagarajah (Citation2011) has claimed that there is a lack of research on translanguaging in multiple modalities, such as writing, which argues for making analytical efforts on translanguaging in multilingual literacies or multimodally. In LIP classrooms focused in the present study, apart from translation and attempting to bring in cross-linguistic transfer in oral talk, a common literacy practice with features of translanguaging was to elicit students’ vocabulary learning through encouraging them to use their full linguistic resources when learning subject-relevant terms and concepts as a first step towards bilingual proficiency. – illustrate examples from study materials from English and Natural Sciences classes in phase 1, where students are to name objects in classroom settings or parts of the digestion system in both Swedish and their first languages (often named as ‘your language’ in the study materials). When working with tasks like these, and in accordance to many previous studies on emergent bilinguals, (García Citation2009; García and Kleifgen Citation2010) the students were encouraged to use multilingual digital dictionariesFootnote3 as well as each other as scaffolds for learning.

Scaffolding students’ learning through the translation of subject-specific vocabulary and bringing attention to equivalencies between languages was a common way of implementing translanguaging strategies in the LIP classrooms. The use of languages other than the majority language (Swedish) or language of that particular lesson (English) was, however often regulated by the teachers. The interaction depicted in Extract 2 took place later during phase 1 and is from an English subject classroom, with the same teacher and student group of 10 students as in Extract 1. During the initial phases of the English lesson, Teacher 1 delimited the students’ language use by strictly notifying them that ‘English or Swedish please, no Dari’ were to be used during the lesson. However, some 15 min into the lesson the study material presented in and the goal of the activity of translating from students’ L1s to Swedish and English both aurally and in writing were made relevant. This multilingual vocabulary inquiry took also place through alternating languages and media, such as mobile phones and text-to-speech applications (see ). The interaction is different from many of the others in the data set in that Teacher 1 uses mostly English and not Swedish, throughout the lesson.

Extract 2. ‘Now you can discuss in your mother tongue’ 1 T1: Now i want you that you can discuss together two and 2 two you can discuss even if you want in your mother 3 tongue (.) I see you have S5 e S7 can sit together(.) 4 *points at S5 and S7* 5 you have Dari 6 S5: Varsågod ((skrattar)) 7 You’re welcome ((laughs)) 8 *pats S6 on shoulder* 9 S6 *stands up and leaves his chair* 10 T1: Yes (.) you both can 11 *points at S3 and S4* 12 can work together (.) and S6 you can come with S1 and 13 S2 ok 14 S7: ((whispers in Dari to S5)) 15 T1: You can discuss together what is in your mother 16 tongue and what is in Swedish 17 *points to papers in her hand and shows them* 18 write here (.) and if you have some questions then 19 you can ask me 20 21 ((33 secs during which people move around in class, 22 teacher hands out papers to the researcher and 23 exchanges a few words with her, students discuss 24 quietly and point towards the newly formed group 25 consisting of S1, S2 and S6)) 26 27 T1: Schh (.) nu ska ni sitta och jobba två ni två jobbar 28 (.) å ni tre här 29 Schh (.) now you should sit and work two and you two 30 work together (.) and you three here 31 *points towards the pairs and groups with her hand* 32 S4: Varför ska de sitta ihop? 33 Why should they sit together? 34 *points towards S1, S2, S6* 35 T1: Jo för att vi har arabiska kurdiska dari (.) de 36 förstår 37 Yes because we have Arabic Kurdish Dari (.) They 38 understand 39 *points to S1, S6 and S2 in this order*

After initially having checked whether the students have questions about the theme of the lesson, ‘Objects and activities in a classroom’, the teacher requests the pupils to discuss the vocabulary translation task with each other in their first or school languages (lines 1–3 and 10–12). In order to provide the students with a possibility to engage in multilingual languaging, the teacher arranges them into pairs or groups of three (lines 3–5, 10–11, 27–28), which are based on students’ L1s or assumed proficiency in related languages. Mixing with the seating order in the classroom is contested by some students both non-verbally and verbally in lines 32–34, whereby the teacher explicates that S6, who is a Kurdish speaker, can work with S1 and S2 who are speakers of Arabic and Dari (lines 35–39). The teacher refers to mutual understanding between the students through transferability between resources of those named languages and goes then on, beyond the extract, to recommend all students to use digital dictionaries when working with the task (see the mobile phone in ). Here, claims can be made that encouraging pupils to collaboratively dialogue in groups where they share linguistic resources that are similar enough with each other, is a way of strategically helping the students to i) draw on all their linguistic resources, ii) build on their background knowledge and iii) engage in cross-linguistic transfer in order to improve their future learning. However, looking at this example from a practised language policing perspective, the teacher’s shift during the lesson from ‘English or Swedish please, no Dari’ to ‘You can discuss in your mother tongue’, indicates that she is very much in charge of the temporal and social spaces in which translanguaging is allowed and encouraged.

As highlighted by the analyses of the first two extracts, translanguaging as a pedagogy has to do with both classroom management and local level language policing. As is often the case in educational settings, the educators take the role of main agents, while the students’ agency is limited. A great challenge for educators is thus empowering learners to take more control of their learning. Canagarajah (Citation2011, 8) has criticised educational contexts in which ‘acts of translanguaging are not elicited by teachers through conscious pedagogical strategies’. Futhermore, he points out that in many circumstances, translanguaging is produced unbidden, or as a side product of regular instruction, which was also often the case in the observed LIP classrooms in phase 1. When dialoguing with the LIP teachers, many of them witnessed of experiencing challenges in creating temporal and spatial spaces for translanguaging in everyday practice. The following extract is from fieldnotes in Teacher 3’s Swedish as a second language class during the early phases of the fieldwork:

In the LIP studied, both beyond and during lessons where Swedish was both the medium and the goal of instruction, students’ multilingual interactions often took place in the margins of the teacher-led ‘main’ interactions. Thus, a ‘Swedish only’ policy was enacted by the teachers and students and the students’ multiple linguistic resources were seldom used in a strategic manner, as illustrated by the fieldnote data above (). However, as the project progressed, during the pedagogical development phase, the participating teachers not only acquired more knowledge of translanguaging as a pedagogy, but also started to implement translanguaging strategies more strategically in their classrooms. A practical challenge for many of the participating teachers had to do with a sense of losing control of the classroom through encouraging translanguaging. ‘If the students don’t use Swedish I don’t understand what they are saying and whether they are doing what they are supposed to do’ was a commonly heard reflection early on. However, as the time went by, teachers witnessed about the excitement and even paybacks of creating a learner-centred environment where the use of participants’ total linguistic repertoires were promoted to a higher degree and where peer interaction functioned as a scaffold for learning.

Figure 3. Fieldnote data from Swedish as a second language classroom (Swedish original with English translation).

Consequently, and finally, I will empirically highlight a pedagogical practice, which entailed creating what Li (Citation2011) has called a translanguaging space in the LIP educational setting. A translanguaging space has been defined as a space created by and for translanguaging practices, where language users ‘break down the ideologically laden dichotomies between the macro and the micro, the societal and the individual, and the social and the psychological through interaction’ (Li Citation2018, 23). In those spaces, it is argued, translanguaging creates a social space for the language users by bringing together different dimensions of their personal histories and experiences, attitudes, beliefs and ideologies, to name a few (Li Citation2011, 1223). Education, as argued by García and Li (Citation2014), can also provide for translanguaging spaces where teachers and students can go between and beyond socially constructed language and educational structures through engaging in diverse meaning-making and identiting (Bagga-Gupta Citation2017).

As one component of phase 2, the development part of the project the present study stems from, Teacher 2 adopted an approach where small group discussions among the students were employed as a reoccurring method for promoting translanguaging and learning during Natural Science classes. In the instance presented in Extracts 3a and 3b, a group of four students who shared Arabic as their first language or language of schooling prior their arrival to Sweden, are learning about fractions through a fraction formula game. They had been initially introduced to the game in Swedish through a whole-class activity, but were late on instructed by the teacher to work in small groups and play the game – and use any languages they preferred to while playing – in order to consolidate what they had learned about counting with fractions. One way of maintaining teacher control in a task like this was to video record group work with an iPad and request students to sum up their calculations in Swedish towards the end of the recording, which the teacher then watched afterwards. The extract below is thus from a video recording made with a teacher’s iPad.Footnote4

Extract 3a. Listening to music and playing a fraction game in natural science 1 S3: btekhtari oghnia hadia? 2 You want a calm song? ((plays an Arabic song from his 3 mobile)) 4 S4: w tabaan hay 5 And of course this 6 S1: baatikid eno hay 7 I think it’s this one 8 S2: (…) ethnin w arbiin 9 ((laughs))forty-two 10 S4: hay adech? 11 How much is this? 12 S1: khamsin setin sabiin 13 Fifteen sixteen seventeen 14 S4: khamsa w sebiin 15 Seventy-five 16 S1: jag räknar mina poäng 17 I’ll count my points 18 S4: kol wahed ye7seb eli odemo 19 Everybody count what you got 20 S1: OK! Jag har (.) 21 Ok! I’ve got (.) 22 S3: Aaah jag har den, vänta lite 23 Aaah I’ve got it, wait a second 24 *turns off the music* 25 S2: Oghnia hedia! 26 A calm song please! 27 S1: fhemt aalik (.)Jag har sjuttiofem komma fem procent 28 I understand you (.)I have 75 point five 29 per cent 30 S3: *Starts to play another song from the mobile* 31 S4: Yes 32 S2: Sjuttiofem komma fem procent 33 Seventy-five point 5 per cent 34 S4: Tamam! Just ja. Då (.) dom här (…) chouf kadech 35 Exactly! Exactly. Then these 36 *takes S1’s fraction tube* 37 Check how much 38 S3: el wahed moaaredh (hums) kan byechtighelna hal lahn 39 I am a rebel (hums) this song means a lot 40 S4: eno hala’a sou’al (.) hala’a eno hay saret thmania . . 41 yaani … baadin hay tsir tio procent (.) aam 42 nejmaaoou mabaadh kelayethoum? 43 Now I’ve got a question (.) Now it’s eight… yaani. . 44 Then it’s ten percent (.) shall I sum it up now? 45 S1: ey ((unclear)) tamam! 46 Yes ((unclear)). Exactly! 47 S3: ((sings quietly along the music from his mobile 48 phone))

The extract begins with S3, who is the only male student in the group, asking the others whether they want to listen to a calm song (in Arabic) while playing the fraction game (lines 1–3). S4, S1 and S2, who seem to be mostly focused on the formal task of playing the game, continue discussing in Arabic and Swedish how to sum up the fractions and get to the final result (lines 4–19). As a response to S4’s urging everybody to count what they got in their fraction tubes (lines 18–19), S1 starts counting the contents of her tube in Swedish in line 20–21. S3 is still referring to a previous request for a more calm song (line 22–23), which is repeated by S2 in lines 25–26. In the next turn, S1 continues to sum up the contents of her fraction tube in Swedish (lines 27–29), which is then confirmed by S4 and repeated by S2, first in English, then in Swedish and again by S4 in Arabic/Swedish (lines 31–35). During these turns, S3 starts playing another Arabic song from his mobile phone. Commenting on the song, he says ‘I am a rebel (.) this song means a lot’ (line 38–39) and starts humming and later, singing the song, while the other students still negotiate how to solve the task (lines 40–46).

Previous literature discusses gradation in translanguaging patterns in classrooms. Rosiérs (Citation2017, 155–156) found that pupils’ active use of translanguaging skills depends on the presence of the teacher and the classroom activities. In short and as indicated by , whole-class activities often account for less translanguaging, while group activities with the teacher absent constitute a platform where translanguaging is present to a higher degree. Apart from creating a social space where the languaging practices construct a locally emerging language policy that reinforces translanguaging as a norm, group activities also potentially open up for performing a wider range of identity positions – allowing students to bring in aspects of their cultural and personal histories, in ways that are not always possible in whole group activities. Thus, beyond positioning themselves as ‘learners of Math’ and ‘multilinguals’, listening to Arabic music while participating in learning activities and engaging in translanguaging allows the students and S3, in particular, to position himself from a perspective that highlights his sense of belonging and identity. This is seen at the end of Extract 3a (lines 38–39) and in Extract 3b which is a continuation to Extract 3a, some 20 s later in the same recording.

Extract 3b. A feeling of nationalism 1 S3: Cena jaya aalaya elwatania 2 I’ve got a strong feeling of nationalism ((collects 3 fraction cards from the table and mixes them until 4 line 26)) 5 S1: yemken femton 6 Maybe fifteen 7 S4: ey ena akoul 8 Yes, I agree with you 9 S2: fasel khamsa komma aw delat? 10 Point five point or divided? 11 *hands move away from each other* 12 delad 13 divided 14 S3: hay lahdha jey aalaya elwatania 15 I’ve got a feeling of nationalism 16 S2: *looks at S3 and smiles* 17 S3: ma’aa ino sarilna barat souria chi khamsa snin w 18 hala’a jey aalaya elwatania 19 No matter that we moved from Syria like five years 20 ago, now I’ve got a nationalistic feeling. 21 S2: aichrin 22 Twenty 23 S4: tjugo procent? 24 Twenty per cent? 25 S2: ey 26 Yes

In line 1–2, possibly infused by the music they are listening to, S3 claims that he has a strong feeling of nationalism. The other students do not acknowledge his claim, as they are focused on the Maths task (lines 5–13). S2 checks her understanding of the Swedish words ‘komma/point’ and ‘delat/divided’ (lines 10–11) through showing with her hands which term she is looking for, and gets a confirmation from S4. In lines 17–20, S3 repeats that he feels a sense of nationalism, which is confirmed by S2 who smiles at him, and the continues on to say that while he (and his family) moved from Syria to Sweden a long time ago, he feels a sense of (Syrian/Arabic) nationalism at the very moment. S2 and S4 then continue discussing the task (lines 21–26).

Summary and conclusions

This study set out to investigate the implementation process of translanguaging as a pedagogical practice as well as the processes of practised language policing that accompany this implementation, at an upper secondary school’s Language Introduction Programme in Sweden. It illustrates, through analyses of students’ and teachers’ engagement in everyday languaging practices in three different subject classrooms over a course of time, different ways in which translanguaging pedagogies have been initially explored and finally strategically implemented in teaching and learning. The analyses reveal that translanguaging practices within the LIP evolved towards a stronger pedagogies that scaffold learning in many ways that are necessary for emergent multilinguals and multimodal transfer between linguistic resources while bringing attention to the translation of subject-specific vocabulary to organising social learning spaces in such ways that multilingual languaging is reinforced. These examples of pedagogical translanguaging highlight the ways in which teachers both in a less planned manner and as their own learning progresses, deliberately draw on their students’ multiple linguistic resources in order to promote and mediate their learning.

Furthermore, I have attempted to examine the participants’ doing of locally constructed classroom language policy through their engagement in everyday languaging within the LIP setting. What becomes apparent here are the aspects of inequal power relations between the participants. While the school development project the study stems from entailed formal attempts to make translanguaging as a part of the everyday language policy within the LIP, teachers also engage in contradicting interactional moves when at times encouraging students to use their multiple linguistic resources and at the same time signalling monolingual L2 ideologies. This was true in particular during the first phase of the project. Thus, the study implies that beyond awareness of practical constraints such as how to include multiple languages in instruction when a teacher might not speak these languages or how to provide time and space for students’ own languaging practices, educators must be aware of both the surrounding societies’, educational systems and their own-projected (negative) attitudes towards multilingual language use. These together make up constraints on translanguaging, and pose a challenge for its strategical use to support student learning and identity development.

Finally, by offering an analysis of communicative and teaching practices as a part of an ongoing pedagogic transformation, I have attempted to critically reflect upon the implementation process of translanguaging as a pedagogical practice. A first stop here calls for reflexivity while attending to the many roles attained and ascribed to the researcher during as well as beyond the fieldwork phases. Within the framework of the present study, my position evolved from a participant-observer producing accounts of people’s practices in phase 1, to a workshop leader during phase 2, the school development part in the LIP setting. In parallel and subsequently, a third identity position emerged, that of an analyst.Footnote5 Attaining this position necessitates leaving the field of engagement and taking on a more distant and analytical role, a process which was facilitated by a venture of data-sessions, engaging with scholarly literature and collegial support.

Previous translanguaging research has argued that introducing fluid language at school can be ‘transformative for the child, for the teacher and for the education itself’ (García and Li Citation2014, 68). While it is difficult, based on the present study, to say whether the transformative power of translanguaging has enabled pupils to construct and modify their sociocultural identities at a large scale, there are indicators that learning more about translanguaging pedagogies and employing translanguaging strategies has entailed a shift for the teachers, teacher practices and possibly even teacher identities. This change of conditions in the classrooms opens up for more than a ‘Swedish only’ policy. As pointed out by Jaspers and Madsen (Citation2018), liberation, release, or transformation are dependent on the relation between language, participants and setting, which in its turn needs to be understood against the background of wider-scale language ideologies and socio-economic processes. It is my hope that the present paper has contributed to those kinds of understandings.

Transcription key

Word word in Dari or Arabic

Word word in Swedish

(.) pause shorter than 0.5 s

(unclear) inaudible

*nods* embodied actions referring to the line above (English translation)

((…)) description referring to vocal conducts or embodied actions that have not been transcribed

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Annaliina Gynne

Annaliina Gynne holds a PhD in Education and works currently at the School of Education, Culture and Communication at Mälardalen University, Sweden. Her research interests include multilingual and multicultural education, languaging, literacies, learning and identities. In particular, her research has focused on issues related to language and literacy practices as well as meaning making and identity work among multilingual young people in minority educational settings.

Notes

1. According to the definition of Swedish National Agency of Education, students are considered ‘newly arrived’ or ‘new arrivals’ for up to four years after enrolling in a school in Sweden. (Skolverket Citation2015).

2. The LIP at the project school was organised in three levels according to the students’ proficiency in Swedish. Within the levels, they were further divided into three to five groups.

3. E.g. Folkets lexikon (’The People’s lexicon’, https://folkets-lexikon.csc.kth.se/folkets/, Lexin https://lexin.nada.kth.se/lexin/or Google Translate, https://translate.google.se/?hl=sv

4. As in any qualitative research, translating recordings of interaction in languages in which the researcher may lack proficiency is always an issue and a potential dilemma. In the present case, translation from Arabic to English has been done by a scholarly colleague proficient in Arabic. For more discussion on the matter, see Bagga-Gupta, Messina Dahlberg & Gynne (forthc.).

5. For more reflections on ethnographic fieldwork, data and researcher reflexivity during fieldwork, analysis and writing phases in and across several interlinked research projects, see Bagga-Gupta, Messina Dahlberg & Gynne (forthc.).

References

- Bagga-Gupta, S. 2014. “Languaging: Ways-of-being-with-words across Disciplinary Boundaries and Empirical Sites.” In Language Contacts at The Crossroads of Disciplines, edited by H. Paulasto, H. Riionheimo, L. Meriläinen, and M. Kok, 89–130, Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Bagga-Gupta, S. 2017. “Center-Staging Language and Identity Research from Earthrise Positions. Contextualizing Performances in Open Spaces.” In Identity Revisited and Reimagined: Empirical and Theoretical Contributions on Embodied Communication across Time and Space, edited by S. Bagga-Gupta, A. L. Hansen, and J. Feilberg, 65–100. Rotterdam: Springer.

- Bagga-Gupta, S., and G. Messina Dahlberg. 2018. “Meaning-Making or Heterogeneity in the Areas of Language and Identity? The Case of Translanguaging and Nyanlända (Newly-Arrived) across Time and Space.” International Journal of Multilingualism 15 (4): 383–411. doi:10.1080/14790718.2018.1468446.

- Bomström Aho, E. 2018. “Språkintroduktion Som Mellanrum: Nyanlända Gymnasieelevers Erfarenheter Av Ett Introduktionsprogram.” Licentiate Thesis., Karlstad University.

- Bonacina-Pugh, F. 2012. “Researching ‘Practiced Language Policies’: Insights from Conversation Analysis.” Language Policy (11): 213–234. doi:10.1007/s10993-012-9243-x.

- Bonacina-Pugh, F. 2017. “Legitimizing Multilingual Practices in the Classroom: The Role of the ‘Practiced Language Policy’.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 1–15. doi:10.1080/13670050.2017.1372359.

- Canagarajah, S. 2011. “Translanguaging in the Classroom: Emerging Issues for Research and Pedagogy.” Applied Linguistics Review 2: 1–28.

- Celic, C., and K. Seltzer. 2013. CUNY-NYSIEB Translanguaging Guide for Educators. New York: CUNY-NYSIEB, The City University of New York.

- Cenoz, J. 2017. “Translanguaging in School Contexts: International Perspectives.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 16 (4): 193–198. doi:10.1080/15348458.2017.1327816.

- Cenoz, J., and D. Gorter. 2017. “Minority Languages and Sustainable Translanguaging: Threat or Opportunity?” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development: 1–12. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/01434632.2017.1284855.

- Conteh, J., and G. Meier. 2014. The Multilingual Turn in Languages Education: Opportunities and Challenges. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Creese, A., and A. Blackledge. 2010. “Translanguaging in the Bilingual Classroom: A Pedagogy for Learning and Teaching?” Modern Language Journal 94 (1): 103–115. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00986.x.

- Creese, A., and A. Blackledge. 2015. “Translanguaging and Identity in Educational Settings.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 35: 20–35. doi:10.1017/S0267190514000233.

- Duarte, J. 2018. “Translanguaging in the Context of Mainstream Multilingual Education.” International Journal of Multilingualism 1–16. doi:10.1080/14790718.2018.1512607.

- Ganuza, N., and C. Hedman. 2017. “Ideology Vs. Practice: Is There a Space for Translanguaging in Mother Tongue Instruction?” In New Perspectives on Translanguaging and Education, edited by B.-A. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, and Å. Wedin, 208–226. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- García, O. 2009. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century. Oxford: Blackwell.

- García, O., and J. Kleifgen. 2010. Educating Emergent Bilinguals: Policies, Programs, and Practices for English Language Learners. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- García, O., S. Johnson, and K. Seltzer. 2017. The Translanguaging Classroom: Leveraging Student Bilingualism for Learning. Philadelphia: Caslon.

- García, O., and W. Li. 2014. Translanguaging: Flerspråkighet Som Resurs I Lärandet. Stockholm: Natur och kultur.

- Gumperz, J. 1982. Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gynne, A., and S. Bagga-Gupta. 2015. “Languaging in The Twenty-first Century: Exploring Varieties and Modalities in Literacies Inside and Outside Learning Spaces.” Language and Education (29) 6: 509–526. doi:10.1080/09500782.2015.1053812.

- Hagström, M. 2018. “Raka Spår, Sidospår, Stopp. Vägen Genom Gymnasieskolans Språkintroduktion Som Ung Och Nu I Sverige.” Doctoral dissertation., Linköping University.

- Hult, F. (2019). “Are Translanguaging and Plurilingualism Interchangeable?” Plenary talk at 3rd Swedish Translanguaging Conference, Växjö. Linnaeus University. April 11–12, 2019.

- Jaspers, J., and L. M. Madsen. 2018. “Fixity and Fluidity in Sociolinguistic Theory and Practice.” In Critical Perspectives on Linguistic Fixity and Fluidity: Languagised Lives’, edited by J. Jaspers and L. M. Madsen, 1–26. New York: Routledge.

- Jonsson, C. 2017. “Translanguaging and Ideology: Moving Away from a Monolingual Norm.” In New Perspectives on Translanguaging and Education, edited by B. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, and Å. Wedin, 20–37. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Jørgensen, J. N. 2008. “Polylingual Languaging in and among Children and Adolescents.” International Journal of Multilingualism 5 (3): 161–176. doi:10.1080/14790710802387562.

- Lärarförbundet. 2017. “Språkintroduktion – Ett Väntrum? Blog Post Written by Rebecca Zimmermann in the Blog Gymnasieskolan I Fokus.” Accessed 10 December 2018.https://www.lararforbundet.se/bloggar/gymnasieskolan-i-fokus/spraakintroduktion-ett-vantrum

- Lewis, G., B. Jones, and C. Baker. 2012. “Translanguaging: Developing Its Conceptualisation and Contextualisation.” Educational Research and Evaluation 18:7: 655–670. doi:10.1080/13803611.2012.718490.

- Li, W. 2011. “Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive Construction of Identities by Multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain.” Journal of Pragmatics 43: 1222–1235. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035.

- Li, W. 2018. “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language.” Applied Linguistics 39 (1): 9–30. doi:10.1093/applin/amx039.

- Mondada, L. (2016). “Conventions for Multimodal Transcription.” Accessed 12 February 2019. https://franz.unibas.ch/fileadmin/franz/user_upload/redaktion/Mondada_conv_multimodality.pdf

- Nilsson Folke, J. 2017. “Lived Transitions: Experiences of Learning and Inclusion among Newly Arrived Students.” Doctoral dissertation., Stockholm University.

- Nilsson, J., and N. Bunar. 2016. “Educational Responses to Newly Arrived Students in Sweden: Understanding the Structure and Influence of Post-Migration Ecology.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 60 (4): 399–416. doi:10.1080/00313831.2015.1024160.

- Otheguy, R., O. García, and W. Reid. 2015. “Clarifying Translanguaging and Deconstructing Named Languages: A Perspective from Linguistics.” Applied Linguistics Review 6 (3): 281–307. doi:10.1515/applirev-2015-0014.

- Paulsrud, B., J. Rosén, B. Straszer, and Å. Wedin, Eds. 2017. New Perspectives on Translanguaging and Education. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Pavlenko, A. 2018. “Superdiversity and Why It Isn’t. Reflections on Terminological Innovations and Academic Branding.” In Sloganizations in Language Education Discourse, edited by S. Breidbach, L. Küster, and B. Schmenk, 142–168. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Rampton, B., K. Tusting, J. Maybin, R. Barwell, A. Creese, and V. Lytra (2004). “UK Linguistic Ethnography: A Discussion Paper.” www.ling-ethnog.org.uk

- Rosiérs, K. 2017. “Unravelling Translanguaging: The Potential of Translanguaging as a Scaffold among Teachers and Pupils in Superdiverse Classrooms in Flemish Education.” In New Perspectives on Translanguaging and Education, edited by B. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, and Å. Wedin, 148–169. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Shaw, S. E., F. Copland, and J. Snell. 2015. “An Introduction to Linguistic Ethnography: Interdisciplinary Explorations.” In Linguistic Ethnography: Interdisciplinary Explorations, edited by F. Copland, S. E. Shaw, and J. Snell, 1–13. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Skolverket. 2015. Språkintroduktion. 17 År Och Nyanländ, Vad Finns Det För Möjligheter? Stockholm: Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education].

- Skolverket. 2016. Utbildning För Nyanlända Elever. Stockholm: Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education].

- Svensson, G. 2017. Transspråkande I Praktik Och Teori. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Swedish Schools Inspectorate [Skolinspektionen]. 2017. Språkintroduktion i gymnasieskolan. Stockholm: Swedish Schools Inspectorate. Granskningsrapport.

- Torpsten, A.-K. 2018. “Transspråkande, Tidigare Kunskaper Och Lärande.” In Transspråkande I Svenska Utbildningssammanhang, edited by B. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, and Å. Wedin, 107–130. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Turner, M., and A. Y. Lin. 2017. “Translanguaging and Named Languages: Productive Tension and Desire.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 1–11. doi:10.1080/13670050.2017.1360243.

- Williams, C. 1996. “Secondary Education: Teaching in the Bilingual Situation.” In The Language Policy: Taking Stock, edited by C. Williams, G. Lewis, and C. Baker, 39–78. Llangefni: CAI.