ABSTRACT

This study applies multimodal conversation analysis to examine how pupils of L2 English in Sweden make use of online translation tools (OTTs), i.e. bilingual dictionaries and Google Translate, in a range of digital collaborative writing tasks. The collection of sequences where pupils use OTTs comes from 31 hours of video-recorded data from four Swedish upper-secondary schools. In contrast to previous research on OTTs, this multimodal micro-analytic study examines the process of using OTTs and links it to the written product, by analysing actions on the screen accompanied by embodied pupil interaction. Thus the analyses track: (1) how and when pupils deploy OTTs, (2) whether the tools help them to resolve lexical gaps and other lexical issues and (3) what problems arise in the process. The study also discusses what help can be offered to overcome the encountered difficulties of using OTTs.

1. Introduction

In line with a national strategy to promote a high level of digital competence in Sweden, digital tools are actively encouraged by the Swedish syllabus for English as a foreign language. Similar developments can be observed elsewhere.

This study focuses on one set of digital tools that are now commonly used by language learners worldwide, here loosely called online translation tools (OTTs), such as online bi-/multilingual dictionaries and Google Translate (GT). In order to find out how second language (L2) pupils use these tools as well as their learning potential, this study applies multimodal conversation analysis (CA) to examine digital collaborative writing. This approach is well suited to tracking how lexical gaps and other troubles emerge in the writing process and how pupils draw on OTTs to resolve them.

The analyses are based on a collection of 40 sequences where pupils use OTTs, extracted from 31 hours of video-recordings of collaborative writing tasks in L2 English from four Swedish upper-secondary schools.

The following research questions guide the study:

How and when do pupils use OTTs to resolve lexical gaps and other lexical issues in the writing process?

To what extent do the OTTs help in resolving these issues?

What troubles arise in the process of using OTTs?

Furthermore, the final discussion engages with how potential hurdles in using OTTs might be overcome, largely with recourse to the affordances of the digital tools themselves.

2. Research review

To date there are a number of studies on the use of OTTs, which may be more or less broadly defined in the literature. In keeping with the present study, the net has been cast wide to include both bi-/multilingual online dictionaries and online translators, such as Google Translate (GT), as well as studies of different languages in the L2 classroom, using a range of methodological approaches from questionnaires to observation studies.

Most questionnaire and interview studies focus on two issues: students’ uses of OTTs and perceptions of their effectiveness (Bahri et al. Citation2016; Branata et al. Citation2019; Levy and Steel Citation2015). One study also compares students’ perceptions with those of teachers (Clifford, Merschel, and Munné Citation2013) and one also includes an assessment of students’ ability to recognise translation errors (Briggs Citation2018). Findings regarding OTT use include the main purposes for using them: primarily looking up words in the L2. As regards perceptions, most studies report students’ reservedly positive attitudes, though Clifford, Merschel, and Munné (Citation2013) report that teachers tended to be more sceptical of the positive impact of OTTs on language learning. Nonetheless, most studies conclude that OTTs provide a useful complement to language studies and may also foster independence; yet due to the limitations of these tools, students need more guidance in their use.

A number of other studies with a mixed method design include questionnaires or interviews after students have performed some form of task (Farzi Citation2016; Garcia and Pena Citation2011; Kol, Schcolnik, and Spector-Cohen Citation2018; Lee Citation2020), but one involves only teachers (Stapleton and Leung Ka Kin Citation2019). These report very similar results to those mentioned above: students being reservedly positive.

Most OTT studies are experimental studies of some kind, comparing at least two sets of written products subject to different conditions, e.g. by students with or without access to OTTs (Fredholm Citation2015, Citation2019; Garcia and Pena Citation2011; Kol, Schcolnik, and Spector-Cohen Citation2018; O’Neill Citation2016, Citation2019) and with or without prior training (O’Neill Citation2016, Citation2019). Some studies reported no significant differences in vocabulary use (e.g. lexical accuracy and complexity) when students had access to OTTs (Fredholm Citation2015; O’Neill’s Citation2016), whereas others reported improved vocabulary use (Kol, Schcolnik, and Spector-Cohen Citation2018; Fredholm Citation2019). O’Neill’s (Citation2016, Citation2019) studies also indicated higher scores for students who received training in using online translators or online dictionaries. Furthermore, Fredholm's (Citation2019) study, investigating longitudinal lexical development, found that using GT resulted in greater lexical diversity over time, although the advantage no longer pertained when OTTs were made unavailable. The latter finding concurs with O’Neill’s (Citation2019) delayed post-test results where no students had access to OTTs, which showed no significant quality differences between groups.

Three mixed method studies include observations, all three analysing screen recordings of writing tasks (Chandra and Yuyun Citation2018; Farzi Citation2016; Garcia and Pena Citation2011). Farzi (Citation2016) combined his study with observations, while Garcia and Pena (Citation2011) also collected keystroke logging data. Chandra and Yuyun’s (Citation2018) quantitative analysis reveals that GT was mostly used for looking up single words. Farzi (Citation2016) also reports that students’ OTTs were mainly used to translate short segments from their L1, but also to double-check the meaning of a word in English, with GT being the most popular tool. Moreover, the OTTs were ‘moderately effective’, and they were used with ‘reasonable efficiency’ (ibid., 175), though only about a third of students used them to any significant extent. Garcia and Pena’s (Citation2011) study of university students beginning Spanish, which compares the written output of students with or without access to OTTs, concludes that OTTs helped beginners (especially those with lower proficiency) to communicate more, but also to produce better quality writing. Analysis of the screen recordings and keystroke logging reveals that writing in the L2 required more engagement (measured by the number of edits), which led the authors to conclude that because students using OTTs wrote with less effort, OTTs may not lead to more learning.

Hence there are few observational studies of using OTTs and no studies carry out qualitative micro-analyses that track how using OTTs can directly impact the final product. Furthermore, no other studies analyse the interaction between the student and the OTTs in any detail, i.e. identify the nature of the process and the troubles that may arise. Moreover, since previous studies investigate individual writing, they are limited to a dyadic participation framework (student-computer) rather than the triadic participation framework of collaborative writing (student-student-computer; cf. Musk Citation2016). The addition of another student makes for a significant change, not only by increasing the potentially available lexical knowledge, but also by introducing the need for students to maintain a high degree of intersubjectivity (mutual understanding). This is achieved, for example, by accounting for their actions verbally and thereby making manifest their thought processes. Furthermore, their displayed embodied actions are also open to each other’s interpretations. These publicly available thought processes and manifested interpretations then provide the analyst with important evidence for interpreting the data. Hence the analytical framework adopted here – multimodal CA – offers more in-depth insights than previous observational studies, and it shows what students actually do rather than what they say they do (cf. questionnaire and interview studies).

Otherwise, research acknowledging writing as a social embodied practice highlighted by multimodal conversation analysis has been steadily growing over the last decade. In a special issue of Language and Dialogue, Mondada and Svinhufvud (Citation2016) review the field and lay principled groundwork for analysing writing-in-interaction, outlining methodological challenges in recording and transcribing as well as modelling the multimodal micro-analysis of writing, but with the emphasis on writing by hand.

Some CA writing studies to date are from classroom settings focusing on students’ collaborative writing. For example, Herder et al.’s studies (Citation2018a, Citation2018b) examine primary school pupils’ reflective practices on e.g. style and correctness and pupils’ writing proposals, observing e.g. that translation generates extensive discourse. Kunitz (Citation2015) investigates university students’ group script writing for a classroom presentation, incorporating translation and back-translation practices and the occasional use of OTTs. A few collaborative writing studies analyse computer-mediated writing tasks, but usually focusing on a specific aspect, such as the use of spellcheckers (Čekaitė Citation2009; Musk Citation2016) and how writers revise their paragraphing (Abe Citation2020). Closer to the current study, Musk and Čekaitė (Citation2017) examine how students bridge epistemic gaps, such as lexical gaps, by means of ‘distributed memory resources’ such as OTTs.

What these CA studies jointly establish is how to carry out sequential multimodal analyses of writing processes, incorporating verbal and non-verbal embodied interactions with other participants as well as with physical artefacts and tools, e.g. computers. Furthermore, some of these studies link the writing process to learning (e.g. Abe Citation2020; Musk Citation2021), though very few explicitly evaluate the final product in relation to the writing process (but see Musk Citation2016).

3. Data and method

The participants of this study are nine pairs of pupils from year 10 (approximately 17 years old) from five different classes of four Swedish upper secondary schools (gymnasium). All the participants gave their informed written consent, according to the principal ethical guidelines recommended by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet Citation2017). To ensure their anonymity, pseudonyms have been used in this study and some of the video stills have been blurred (in accordance with their consent forms).

The nine pairs generated approximately 31 hours of video-recorded collaborative writing data, collected in 2012, 2018 and 2019 over a series of two to five classes. Recordings were made of each pair using at least two video cameras. In most cases one camera filmed each laptop screen from behind and one camera from the side to capture the embodied actions of the pair. The data from 2019 also includes screen recordings (with audio) captured with the software OBS Studio. The software also video-recorded the pair via the computer’s inbuilt video camera in the upper left-hand corner of the screen recording.

There were three different written tasks: argumentation essays, a project on famous Americans and a shorter text about International Women’s Day. For the first two, students were free to select their own topic/famous person. The writing was done on laptops with Internet access either in Word or in Google Docs. The data from 2012 and 2019 involved working on a single shared laptop, whereas pupils worked on two separate laptops in a shared web-based document (Google Docs) in the data from 2018. In all cases, students were co-present though when students worked on separate laptops, they could potentially work individually rather than collaboratively. The analyses incorporate how the precise participation frameworks affect the interactions.

The method of data analysis can be characterised as multimodal conversation analysis, adhering to the central principles of Conversation Analysis (cf. Seedhouse Citation2004; Hutchby and Wooffitt Citation2008), which studies the methods people routinely use to make sense of their actions (Kasper and Wagner Citation2011, 117). This entails, for example, tracking actions sequentially (and simultaneously in multiple modalities) on an action-by-action basis, adopting an emic (participant-oriented) approach. Accessing the participants’ own perspective is aided by the next-action proof procedure (Broth and Mondada Citation2013, 52), whereby next actions reveal how participants have interpreted the immediately preceding action. In the current study this entails uncovering the methods that pupils of L2 English use to interpret each other’s actions in dealing with emergent lexical gaps and other troubles in their written text-in-the-making. CA is thus an inductive (data-driven) approach, whereby interactional patterns of practice are sought out in the (video) data without recourse to external theoretical frameworks (cf. Heritage Citation2008). Furthermore, this study follows many other CA studies in that it is collection based, here based on a collection of 40 uses of OTTs. Building collections is the established CA method of going beyond single case analyses and making robust claims and achieving a higher degree of generalisability (Hutchby and Wooffitt Citation2008, 88). It is then through cumulative empiricism across studies and data sets that such claims are corroborated and consolidated.

To aid with the analyses, the current study makes use of augmented transcriptions. Analysing and illustrating collaborative writing in a digital environment requires careful attention to different modalities (e.g. typing and the handling of artefacts, talk, gaze and body movements), which are frequently laminated (layered) and deployed simultaneously. Not least since using OTTs is carried out on the computer, the transcriptions follow those designed by Musk (Citation2016) to capture interactional features that are salient for this particular triadic ecology (pupil-pupil-computer). For example, each line number may include simultaneous modes of action signalled by two icons (![]() for talk and

for talk and ![]() for handling the computer). Actions may also be illustrated by video screenshots where they are deemed important. The line numbering follows talk or pauses in talk, but unnumbered lines show modes of action that occur at the same time as the closest numbered line above (for further details of transcriptions see the online supplementary file).

for handling the computer). Actions may also be illustrated by video screenshots where they are deemed important. The line numbering follows talk or pauses in talk, but unnumbered lines show modes of action that occur at the same time as the closest numbered line above (for further details of transcriptions see the online supplementary file).

4. Results

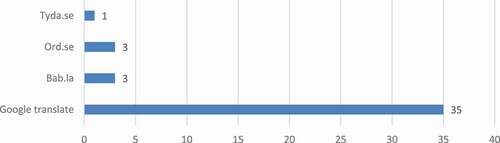

The vast majority of the 40 cases in my collection of looking up a word or phrase in OTTs involve GT, but the full list of OTTs and their frequencies of use are shown in . Of these, the majority – 23 cases – occur in the process of composing text, which is in focus here.

The cases of composing text can be further divided into four categories, according to how the OTTs are used: (1) to find words the pupils don’t have immediate epistemic access to (cf. Stivers, Mondada, and Steensig Citation2011, 9; see also Musk and Čekaitė Citation2017), i.e. because they don’t know or cannot remember them; (2) to find more advanced synonyms of common words or phrases; (3) to resolve disputed words or clear up uncertainties about a word already in play; and (4) to look up longer text strings in GT. Both cases in the last category were carried out on a mobile phone but they are only partially filmed, so they will not be exemplified here.

4.1. Looking up unknown or forgotten words

The first category is the largest with 14 cases, listed with their translations in . In almost all cases, turning to an OTT enables pupils to resolve their emergent lexical gap, as can be seen in the final column of the table.

Table 1. List of unknown or forgotten words

is not the simplest example to illustrate this first category, but it involves collaboration and shows how turning to an OTT is frequently not a first resort. It also illustrates a range of verbal and embodied actions that regularly accompany the collaborative word searches that precede OTT use.

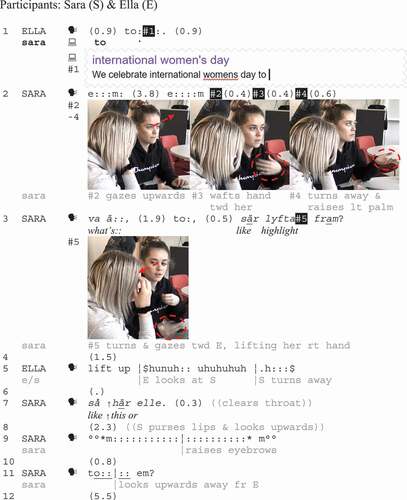

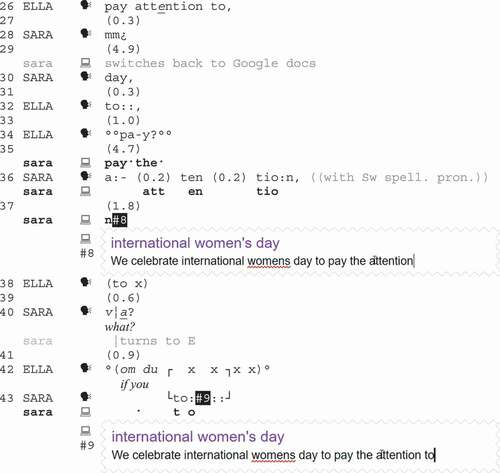

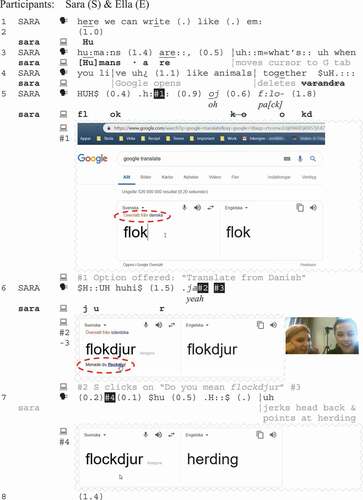

In , Sara and Ella are writing the first sentence of a text about International Women’s Day. Sara is typing and up until line 1, she has been writing and simultaneously vocalising the text, though there is a delay in vocalising her typed ‘to’ in line 1. Instead, Ella vocalises this with a prolonged ‘to::’, which demonstrates her active participation in the writing process as well as signalling the need for a continuation.

Excerpt 1a. Participants: Sara (S) & Ella (E).

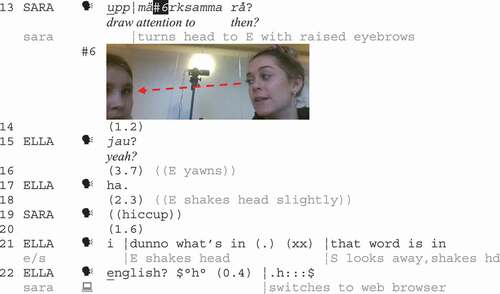

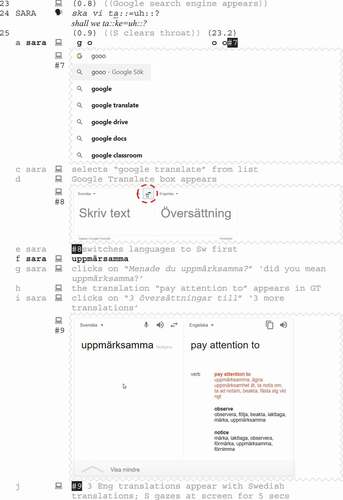

The syntactically incomplete sentence with the final infinitive marker ‘to’ now requires a verb; so a word search ensues. This is marked verbally with Sara’s prolonged perturbations and long pauses in line 2, accompanied by gazing upwards with a ‘thinking face’ (Goodwin and Goodwin Citation1986) and then by averting her gaze, as well as by hand gestures (#2-#4). After a failed attempt to produce a word in English, Sara then codeswitches to Swedish to make a translation request directed towards Ella through her gaze (3, #5) (cf. Stoewer and Musk Citation2019). After a long pause, Ella offers a very literal, but non-serious translation, as evidenced by her laughter (5). Yet another prolonged word search sequence ensues (7–12) with characteristic features similar to before, but now enhanced with Sara’s pursed lips and then raised eyebrows. In line 13, Sara turns back to Ella while delivering yet another translation request with a Swedish synonym for her failed first request (lyfta fram ‘highlight’ > uppmärksamma ‘draw attention to’). This time Ella displays her active involvement in the word search both verbally (15, 17, 21–22) and by shaking her head (18 & 21), even though she makes it explicit that she too lacks epistemic access to an English translation (i.e. doesn’t know or cannot recall it; cf. Stivers, Mondada, and Steensig Citation2011, 9; see also Musk and Čekaitė Citation2017). This is where Sara switches tab to access the web browser (22). In line 24 of Sara suggests using GT, completing her syntactically incomplete verbal turn by typing ‘Gooo’ in the Google search engine and selecting ‘google translate’ from the offered suggestions (#7).

Excerpt 1b.

When the GT interface appears, Sara switches languages so that Swedish comes first before typing ‘uppmärsamma’ with a typographic error (25a-e). Sara accepts GT’s repair initiation and the translation ‘pay attention to’ appears (25 g-h). Sara doesn’t accept this immediately, but instead opts for three more translations, which include the first suggestion in red (#9). These English translations are followed by a list of several Swedish back-translations, which add a more nuanced meaning for each. Sara focuses on the screen for 5 seconds (25 j), before Ella reads the first suggestion (26). Sara gives a minimal agreement token (28) before returning to their text. The delay in typing Ella’s selected translation prompts Sara to read out the last two words typed (30 & 32) and then say the first word of the translation, but now with less epistemic certainty, since it is almost whispered and ‘try-marked’ with slightly rising intonation (34) (Sacks and Schegloff Citation1979, 18). After another long pause (35), Sara types the GT translation while vocalising it with Swedish spelling pronunciation (36–43). However, in the process Sara adds a definite article, which wasn’t in GT: ‘pay the attention to’. We shall return to complications and problems that arise in using OTTs shortly. Otherwise, GT has been used partially successfully to overcome a lexical gap, which Sara and Ella could not bridge collaboratively.

4.2. Finding more advanced synonyms

The second category has four cases, listed with their translations in . One aspect of collaborative writing that pupils sometimes orient to is that the vocabulary they use should not be too simple. Sometimes this is made explicit, but often it is implicit – as in – by rejecting simple words in favour of more advanced or stylistically formal vocabulary. Not all word negotiation sequences involve OTTs, but as in the case of , if an initial word search fails to resolve the lexical gap satisfactorily, using an OTT provides one common solution.

Table 2. List of searches for more advanced synonyms

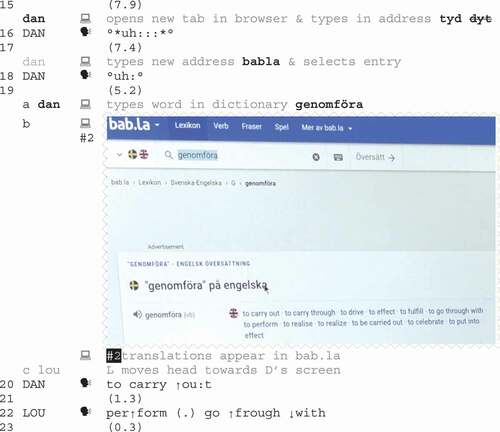

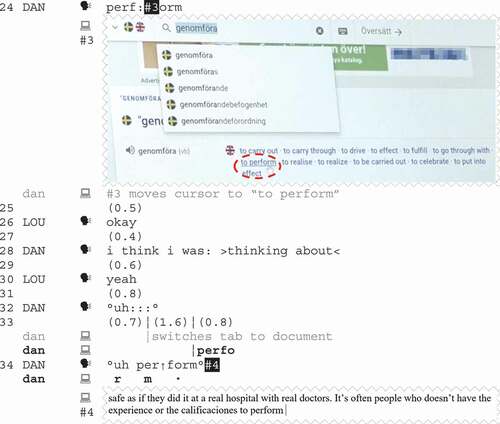

In Daniel and Louise are writing an essay arguing the case for legalised abortions. They are four sentences into their second paragraph, and similar to , they are about to add the infinitive marker ‘to’, with Daniel both typing and vocalising his text. A verb is needed next, which both Daniel and Louise signal with speech perturbations and using different prosodic means in how they say ‘to’, Daniel with rising intonation (1) and Louise with a prolonged vowel delivered in a creaky voice (2).

Excerpt 2a.

The word search for ‘perform’ is accompanied by Daniel’s rolling hand movement (3). Louise offers a first candidate in line 4 together with the definite article ‘do *de:::*’ (do the), but Daniel shows no uptake of the simple verb ‘do’ and, indeed, after a long pause, Louise renews her word search by repeating the prolonged infinitive marker (7). After an even lengthier pause, Daniel produces a translation request for genomföra ‘perform’ as an attempt to resolve their lexical impasse. Louise’s speech perturbation in line 12 is an active display of her trying to comply with Daniel’s request, but after a long pause Daniel’s prolonged men:: ‘but::’ signals a different course of action and in line 15 of he opens a new tab and searches for the OTT Bab.la (after first seemingly rejecting another: Tyda.se).

Excerpt 2b.

The search in Bab.la results in no fewer than twelve suggestions (#2), which occasions a negotiation of which translation matches the present context (‘perform an operation’). Both Daniel and Louise engage in reading out three of the twelve alternatives (20 & 22), before Daniel repeats the first of Louise’s potential suggestions (24) while also moving his cursor to the same item: ‘to perform’ (#3). After Louise’s affiliative response (26) Daniel gives a retrospective account for his choice (cf. Jakonen Citation2018), which frames his previous lack of epistemic access as a temporary one and his resorting to an OTT as a memory jog. At the same time, this account is also a claim for epistemic primacy or authority (cf. Heritage Citation2005; Stivers, Mondada, and Steensig Citation2011), backed up by the dictionary entry.

4.3. Resolving disputed or uncertain words

The third category has three cases, listed in . In each case the word that is finally typed has been offered by one of the pupils, but either the pupil suggesting the word lacks epistemic certainty and resorts to an OTT to confirm it, or – as in – the proposed word is contested by the other pupil and an OTT is deployed to confirm its ‘correctness’.

Table 3. List of disputed or uncertain words

Before begins, Bruce and Syd have been reading about Neil Armstrong in Wikipedia, where they find the following sentence, which Bruce then proceeds to read aloud:

In 1947, at age 17, Armstrong began studying aeronautical engineering at Purdue University.

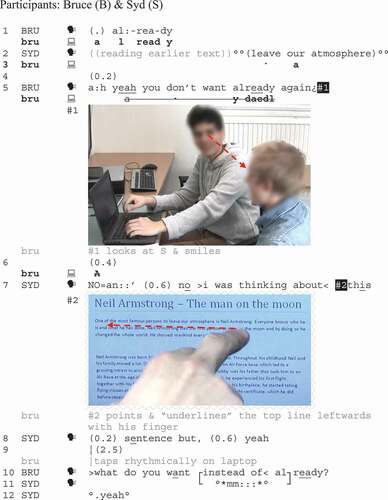

Excerpt 3a.

He then poses the question ‘are we supposed to say already at the age of seventeen?’, where he has added the adverb ‘already’. After a side sequence where Bruce makes a suggestion for the oral presentation, he switches back to their Word document to start composing and typing the continuation of their joint text.

As Bruce had previously suggested, he starts typing and simultaneously vocalising his text in line 1, starting the sentence with ‘Already’. About 17 minutes earlier in the same lesson, Bruce had typed ‘Already in his first years’, after which Syd had contested a similar use of ‘already’, asking ‘doesn’t that sound wrong to you?’. The upshot was that Syd took over the keyboard and composed a completely different sentence. Thus, when Syd starts whispering a phrase from the very first sentence of their text (2), Bruce hears his whispering as a repair initiation (Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks Citation1977, 364; Seedhouse Citation2004, 34) and explicitly recalls their previous discussion (5) and starts deleting ‘Already·a’, and then turns to look at Syd smiling (#1). Even though Syd gives an alternative account for his whispering (7–8) and backs it up by pointing to where he was reading in the text (#2), he completes his turn with a weak disaffiliation marker: ‘but, (0.6) yeah’, which triggers Bruce to challenge Syd to suggest an alternative to ‘already’, which he evidently perceives as the trouble source (Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks Citation1977, 363; Seedhouse Citation2004, 34). The urgency of the request is pre-signalled by Bruce’s rhythmic drumming (9), but Syd doesn’t succeed in producing more than a quiet creaky ‘°*mm:::*°’ in overlap (11), albeit displaying his engagement with the challenge. This is followed by a ‘.yeah’ produced on an inbreath (12), which Bruce takes to mean that no alternative is forthcoming, since he then turns to Google Translate for a solution (3b: 13).

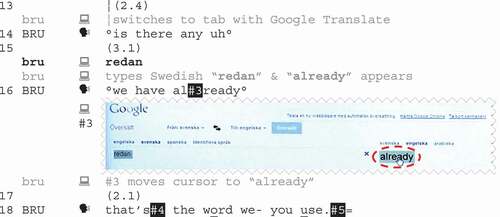

Excerpt 3b. Already at the age of seventeen.

In an attempt to solve the issue of whether ‘already’ can be used in this context (preceding a time phrase), Bruce types the Swedish ‘redan’ in GT, whereupon ‘already’ appears as a translation (15). It should be mentioned at this juncture that in Swedish redan is used as a regular intensifier before expressions of time, which explains Bruce’s action to translate redan here.

In fact, the only option offered by GT is ‘already’, which is highlighted by Bruce moving the cursor to the English translation (#3) while quietly stating the result (16). In line 18 Bruce ascribes GT’s single result epistemic primacy/authority (cf. Heritage Citation2005; Stivers, Mondada, and Steensig Citation2011) and thereby stands his ground. The repair from ‘we’ to ‘you use’ not only projects his upcoming action to re-use ‘already’, but also makes a more general claim that this is correct use. Bruce’s claim is also reinforced by his embodied actions: looking at the computer screen (with its unequivocal translation) and his raised palm (#4), suggesting the need for Syd to yield. Syd’s embodied response, raising his right hand swiftly and bringing it down sharply to slap his thigh (#5-7) followed by leaning away from Bruce in disaffiliation (#8), displays mild indignation as well as submission. This is matched verbally by Syd delivering his reluctant acquiescence as an abrupt command ‘use it then’ (19). Syd remains demonstrably leaning away from Bruce on his chair, while Bruce asserts his prerogative as typist (Čekaitė Citation2009) to write ‘already’ followed by the time phrase he originally suggested (20). Hence, GT has been use here to solve a recurring dispute about a rather unidiomatic use of ‘already’, being unable to display a more idiomatic alternative to the Swedish intensifier redan.

4.4. Troubles that arise while using OTTs

This section responds to the third research question with close reference to –, but also bringing in another illustrative example. However, before we examine these examples, we need to define what is meant by ‘troubles’, since there are two possible perspectives here: an etic and an emic one. CA would usually take an emic perspective, whereby participants themselves display in various ways what trouble is, such as through the repair mechanism (initiating and carrying out repair in response to a trouble source; cf. Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks Citation1977; Seedhouse Citation2004). Yet correctness, accuracy and appropriateness are aspects of language and language learning which are etically assessable whether or not language users orient to these aspects (which they also do). Yet another aspect of an etically/normatively determined assessment is whether the OTT actually offers correct and contextually appropriate translations in the first place, as well as the pupils’ epistemic access to lexical knowledge to select or identify a correct/appropriate translation. Here aspects of both perspectives will be addressed.

As we saw in , trouble can arise in the process of using OTTs to resolve lexical issues. There the only translation offered did not match the context and the ‘solution’ resulted in unidiomatic English: *‘Already at the age of seventeen’. Nevertheless, evoking the epistemic primacy/authority of the OTT, Bruce was able to claim the correctness of ‘already’ (: 18). Although this was acceptable from a participant (emic) perspective (at least for Bruce), from a normative (etic) perspective ‘Even at the age of seventeen’ would have been more idiomatic, but GT didn’t offer a contextually appropriate choice. In fact, GT now offers two further alternatives as a translation of redan: ‘as early as’ and ‘even’, which might have resulted in a different outcome.

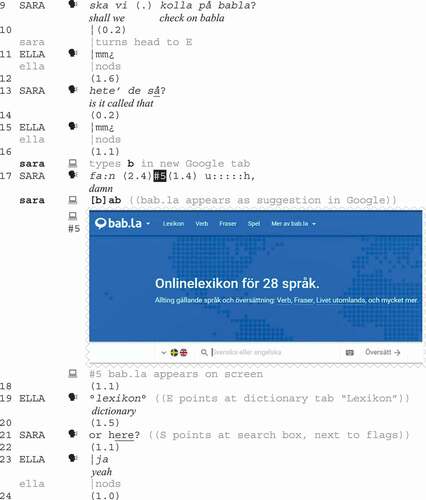

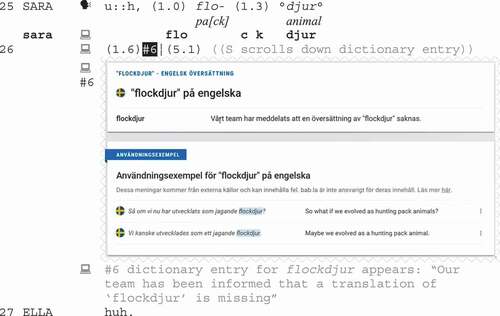

In the next example () not only does the first OTT not offer a correct translation, which the students also reject, the second OTT they turn to doesn’t offer an authenticated translation at all. Here Sara is looking for a translation of flockdjur ‘pack/herd animal(s)’ in the context ‘Humans are … ’. She first offers a definition of the word in question (2–3), presumably to elicit it. However, instead of turning to Ella to respond, she opens GT and prepares to type in flockdjur (by first deleting the word she last looked up) while she is still producing the definition. Immediately after completing her definition, she laughs at it while typing the Swedish word.

Excerpt 4a.

Sara encounters a new trouble while typing the Swedish word, since she spells the first part of the compound incorrectly, which GT then detects as being Danish (5, #1). Although she deletes and retypes part of it with the same incorrect spelling (5), this time she completes the compound noun and GT suggests the correct spelling (6, #2). However, the translation then offered, ‘herding’ (#4), is both incorrect (from an etic perspective) and it creates consternation and is rejected. The rejection is signalled verbally by Sara’s abrupt ‘uh’, by her immediate embodied reaction (jerking back her head) and then pointing at the translation (7), as well as by her suggestion to use another OTT (, 9). Thus ‘herding’ is also deemed unsuitable from an emic perspective. Although Sara suggests using the OTT Bab.la, she also displays her unfamiliarity with it, by checking that the name is correct (13) and then by hesitating at where to type the word (17–20).

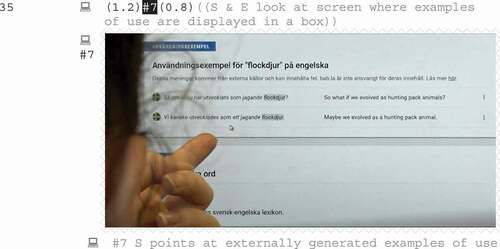

Excerpt 4b.

Sara now types in the search word (25), but when the dictionary entry appears (26, #6), no translation is available, which occasions Ella’s delayed brief expression of surprise ‘huh’. (27). What ensues (in the omitted lines) is scrolling up and down the page to find relevant information, until Sara establishes their joint attention to the box with two examples of use by pointing (35, #7) (cf. Due and Toft Citation2021).

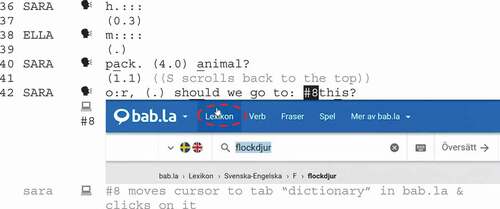

Excerpt 4c.

Sara then identifies and vocalises the translation of flockdjur, ‘pack. (4.0) animal?’ (40). The long delay in saying both words corresponding to the Swedish compound noun, as well as the try-marking of ‘animal?’ (Sacks and Schegloff Citation1979, 18) followed by Sara scrolling back up and making a counter suggestion (41–42), display her epistemic uncertainty regarding the suitability of this translation from an emic perspective. Ella’s silence suggests a similar lack of epistemic access to be able to evaluate the translation offered. Their uncertainty may also have been compounded by the disclaimer in the line above the two examples (#7): ‘These sentences come from external sources and may contain errors. Bab.la is not responsible for their content’. Even so, from an etic perspective the translation is contextually suitable for their text-in-the-making. The final outcome is that Sara clicks on the dictionary tab (42, #8), which leads to further confusion in the continuation beyond , since no further information is offered on translating flockdjur. Instead, Ella suggests asking the teacher, which is what they do to solve their lexical impasse.

A third trouble that can arise is closely related to the second insofar as pupils need some degree of epistemic access to make use of the OTT. However, here the potential trouble stems from the OTT offering several translations, which occasions the need to select a suitable candidate. This was the case in , where the pupils were faced with twelve possible translations of genomföra (: 19b, #2). In that particular case they were able to solve this both to their own satisfaction (emically) and the outcome was correct English for the context (etically): ‘perform an operation’. However, in , there seemed to be greater epistemic uncertainty when faced with three candidates for uppmärksamma: ‘pay attention to’, ‘observe’ and ‘notice’, firstly by Sara clicking on ‘3 more translations’ (: 25i) and thereby displaying uncertainty about the first option and secondly since there was a 5 second delay before Ella suggested the first option (: 25 j-26). In this particular context (‘We celebrate international womens [sic] day to pay the [sic] attention to equality … ’), their choice produced acceptable but perhaps not the most idiomatic English; from an etic/normative perspective ‘draw/bring attention to’ or even ‘observe’ would have worked better here, though from an emic perspective the students were able to bridge their emergent lexical gap.

will also serve to illustrate the fourth and final trouble, i.e. that after consulting an OTT, pupils might not remember this correctly when they come to write the word in their own text. In this case the issue is the addition of an incorrect definite article ‘pay the attention to’ (: 35). A second example involves the correct translation of i längden in GT: ‘in the long run’. However, what gets typed is the incorrect ‘in the long time’. Thus from an etic, rather than from an emic perspective, errors can creep in unnoticed. Spelling errors, on the other hand, tend to be picked up by the spelling checker in the word processing software (Word or Google Docs) if they are overlooked by the typist (and if switched on) (e.g. : 6, #2; cf. Musk Citation2016). In the discussion we shall return to potential solutions to these troubles.

5. Concluding discussion

In answer to research question 1, how and when pupils use OTTs to solve lexical gaps, the analyses identified four main uses of OTTs. Furthermore, the process of using OTTs in composing text regularly involved an emergent lexical gap, leading to a variably elaborate and collaborative word search. Analyses of the word search process revealed a range of features, including: vocalising syntactically incomplete utterances; disfluency markers such as perturbations, pauses and sound stretches; a thinking face, averted and directed gaze; hand gestures. Over half of the cases (12 out of the 23 cases) involved explicit translation requests or other collaborative attempts to solve the lexical impasse. Only when the word search or negotiation failed to yield an (acceptable) candidate did pupils turn to an OTT. Then if more than one translation was offered, a more or less elaborate word selection negotiation sequence often ensued. Previous observational studies on the use of OTTs failed to shed much light on the component features of this process, even for individual OTT use.

Turning now to question 2, whether OTTs can solve lexical troubles, students were satisfied (from an emic perspective) with 21 of the translations offered by one or another OTT insofar as almost all of these found their way into their text (the two longer text strings being an exception; otherwise see ). These findings corroborate students’ generally positive perceptions of using OTTs, as revealed in the questionnaire and interview studies (e.g. Bahri et al. Citation2016; Branata et al. Citation2019; Levy and Steel Citation2015), in that students were almost always able to use OTTs to solve their lexical gaps from an emic perspective. From an etic/normative perspective, the pupils succeeded in bridging 19 lexical gaps correctly with the help of OTTs. Some previous experimental studies that compared vocabulary use between students with and without access to OTTs reported improved vocabulary use among those with OTT access (Kol, Schcolnik, and Spector-Cohen Citation2018; Fredholm Citation2019), whereas others found no significant difference (Fredholm Citation2015; O’Neill Citation2016). However, these studies simply compared the final written product, but not how this related to their actual use of OTTs, as in the current study.

Question 3, dealing with troubles encountered in the use of OTTs was specifically addressed in the previous section. However, the findings of this study do not only identify problems; OTTs can also provide additional affordances for learning, as we shall see in the next section.

6. Pedagogical implications

Since the data reveal how students resolve the problems they encounter when engaging with OTTs, their solutions can provide the basis for creating familiarisation tasks to help students develop improved strategies for using these tools.

Different OTTs have different features and therefore offer different kinds of help. Starting with GT, in Sara clicks on alternative translation suggestions to the one displayed first: ‘pay attention to’ (#9). In the current GT interface, a list of alternatives appears automatically. As noted earlier, GT now offers alternative translations to redan, one of which – ‘even’ – would have been contextually more idiomatic (: #9).

If the translations suggested by GT are problematic, for example if they don’t match the context or if a user is unsure about the English word(s) offered, a second option is to double-check with another OTT. There are two occurrences of this in these data sets: one has been commented on already under the section about difficulties with OTTs (). Suffice it to say here that although Bab.la provided no translation for flockdjur, it did provide another helpful resource, viz. example translation sentences, which Sara noticed and read out (: 40). Thus, despite Bab.la’s disclaimer, it did in fact offer ‘pack animal’, which fitted the context. The other case of double checking involved källförteckning, which in GT was translated by ‘bibliography’. However Hannes was not satisfied with this and turned to Bab.la instead, which offered four alternatives, one of which Hannes selected: ‘reference list’.

A third option is to make use of the other resources offered specifically by bilingual online dictionaries. For example, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, Sara and Ella consulted the example sentences generated from external sources in Bab.la (: #7), although they were unable to make use of this. In addition to the externally generated examples, there are often (approved) translations with examples and synonyms, though these resources are not made use of in the current data sets. The range of additional features (both those mentioned above and others offered by GT) is sparsely used in the data and therefore it is unlikely that pupils are familiar with using all of them. It would therefore be beneficial to set pupils tasks to familiarise them more with using different OTTs. This could then be followed up with a discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of using different OTTs and their varying features to achieve greater contextual accuracy and a sensitivity to register and style. The objective would be to encourage pupils to develop an increased range of strategies for using OTTs with a critical eye. Indeed, there is some evidence from O’Neill’s (Citation2016, Citation2019) experimental studies that training along the lines suggested above can improve performance.

7. Final reflections

This study has explored pupils’ use of OTTs by applying multimodal conversation analysis. In order to understand the collaborative writing process in a technology-rich environment and what hurdles pupils need to overcome in making use of digital tools, we need to be able to track and identify the components of these trajectories and their inherent features, such as word searches, how pupils interpret the information offered by OTTs as well as how they incorporate this in their writing. With its microanalytic tools, multimodal CA is immanently well suited to 1) uncovering the details and patterns of the triadic participation framework (student-student-computer) of these practices, 2) revealing the nature of emergent problems and their potential solutions, and 3) tracking how participants’ actions and talk display their current epistemic status (i.e. what knowledge they have access to at a particular point in time), how they interpret each other’s epistemic status and potentially achieve epistemic progression (knowledge gains; cf. Balaman and Sert Citation2017). Analysing collaborative writing in this manner identifies not only the role of social interaction but also reveals cognitive aspects of the language learning process and its mechanisms. Finally, multimodal CA allows the analyst to link the process to the final product in each case, which none of the previous studies on OTTs have achieved.

The current study drew on video data collected in the classroom. However, when pupils work on separate computers but in a shared document in Google Docs – as was the case for some of the current data – they would also be able to write collaboratively outside the classroom environment. A multimodal CA study of distance use of shared documents would further our knowledge of the collaborative and technical affordances of using OTTs.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (191.7 KB)Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Ufuk Balaman, who gave valuable comments on the first draft of this article and also to the three anonymous reviewers for their detailed quality comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nigel Musk

Nigel Musk is associate professor in English at Linköping University, Sweden. His main research interests concern language learning and bilingualism in educational contexts, focusing particularly on situated learning processes and languaging practices (including code-switching), primarily using multimodal conversation analysis. Further details may be found on his website: https://liu.se/en/employee/nigmu65

References

- Abe, M. 2020. “Interactional Practices for Online Collaborative Writing.” Journal of Second Language Writing 49: article 100752. 100752. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2020.100752.

- Bahri, H., and T. S. T. Mahadi. 2016. “Google Translate as A Supplementary Tool for Learning Malay: A Case Study at Universiti Sains Malaysia.” Advances in Language and Literary Studies 7 (3): 161‒167.

- Balaman, U., and O. Sert. 2017. “The Coordination of Online L2 Interaction and Orientations to Task Interface for Epistemic Progression.” Journal of Pragmatics 115: 115–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.01.015.

- Branata, J., R. D. Susanto, E. T. Murtisari, and R. Widiningrum. 2019. “Google Translate in Language Learning: Indonesian EFL Students’ Attitudes.” Journal of Asia TEFL 16 (3): 978‒986.

- Briggs, N. 2018. “Neural Machine Translation Tools in the Language Learning Classroom: Students’ Use, Perceptions, and Analyses.” The JALT CALL Journal 14 (1): 2‒24. doi:https://doi.org/10.29140/jaltcall.v14n1.221.

- Broth, M., and L. Mondada. 2013. “Walking Away: The Embodied Achievement of Activity Closings in Mobile Interaction.” Journal of Pragmatics 47 (1): 41‒58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.11.016.

- Čekaitė, A. 2009. “Collaborative Corrections with Spelling Control: Digital Resources and Peer Assistance.” International Journal of Computer Supported Collaborative Learning 4 (3): 319‒341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-009-9067-7.

- Chandra, S. O., and I. Yuyun. 2018. “The Use of Google Translate in EFL Essay Writing.” LLT Journal 21 (2): 1410‒7201.

- Clifford, J., L. Merschel, and J. Munné. 2013. “Surveying the Landscape: What Is the Role of Machine Translation in Language Learning?” @tic. Revista D’Innovació Educativa 121 (10): 108–121.

- Due, B., and T. Toft. 2021. “Phygital Highlighting: Achieving Joint Visual Attention When Physically Co-editing a Digital Text.” Journal of Pragmatics 177: 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.01.034.

- Farzi, R. 2016. “Taming Translation Technology for L2 Writing: Documenting the Use of Free Online Translation Tools by ESL Students in a Writing Course.” PhD diss., University of Ottawa.

- Fredholm, K. 2015. “Online Translation Use in Spanish as a Foreign Language Essay Writing: Effects on Fluency, Complexity and Accuracy.” Revista Nebrija de Lingüística Aplicada 18.

- Fredholm, K. 2019. “Effects of Google Translate on Lexical Diversity: Vocabulary Development among Learners of Spanish as a Foreign Language.” Revista Nebrija de Lingüística Aplicada a La Enseñanza de Lenguas 13 (26): 98‒117.

- Garcia, I., and M. I. Pena. 2011. “Machine Translation-assisted Language Learning: Writing for Beginners.” Computer Assisted Language Learning 24 (5): 471‒487. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2011.582687.

- Goodwin, M. H., and C. Goodwin. 1986. “Gesture and Coparticipation in the Activity of Searching for a Word.” Semiotica 62 (1): 51‒75.

- Herder, A., J. Berenst, and T. Koole. 2018a. “Reflective Practices in Collaborative Writing of Primary School Students.” International Journal of Educational Research 90: 160–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2018.06.004.

- Herder, A., J. Berenst, and T. Koole. 2018b. “Nature and Function of Proposals in Collaborative Writing of Primary School Students.” Linguistics and Education 46: 1‒11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2018.04.005.

- Heritage, J. 2005. “Cognition in Discourse.” In Conversation and Cognition, edited by H. Te Molder and J. Potter, 184‒202. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Heritage, J. 2008. “Conversation Analysis as Social Theory.” In The New Blackwell Companion to Social Theory, edited by B. Turner, 300‒320. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Hutchby, I., and R. Wooffitt. 2008. Conversation Analysis. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Jakonen, T. 2018. “Retrospective Orientation to Learning Activities and Achievements as a Resource in Classroom Interaction.” The Modern Language Journal 102 (4): 758–774. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12513.

- Kasper, G., and J. Wagner. 2011. “A Conversation Analytic Approach to Second Language Acquisition.” In Alternative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition, edited by D. Atkinson, 117‒142. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Kol, S., M. Schcolnik, and E. Spector-Cohen. 2018. “Reflective Practice: Google Translate in Academic Writing Courses?” The EUROCALL Review 26 (2): 50‒57. doi:https://doi.org/10.4995/eurocall.2018.10140.

- Kunitz, S. 2015. “Scriptlines as Emergent Artifacts in Collaborative Group Planning.” Journal of Pragmatics 76: 135‒149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.10.012.

- Labov, W. 1972. Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Lee, S.-M. 2020. “The Impact of Using Machine Translation on EFL Students’ Writing.” Computer Assisted Language Learning 33 (3): 157‒175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1553186.

- Levy, M., and C. Steel. 2015. “Language Learner Perspectives on the Functionality and Use of Electronic Language Dictionaries.” ReCALL 27 (2): 177‒196.

- Mondada, L., and K. Svinhufvud. 2016. “Writing-in-interaction: Studying Writing as a Multimodal Phenomenon in Social Interaction.” Language and Dialogue 6 (1): 1‒53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/ld.6.1.01mon.

- Musk, N. 2016. “Correcting Spellings in Second Language Learners’ Computer-assisted Collaborative Writing.” Classroom Discourse 7 (1): 36‒57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2015.1095106.

- Musk, N. 2021. “How Do You Spell That?” Doing Spelling in Computer-assisted Collaborative Writing.” In Classroom-Based Conversation Analytic Research: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives on Pedagogy, edited by S. Kunitz, N. Markee, and O. Sert, 97‒125. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Musk, N., and A. Čekaitė. 2017. “Mobilising Distributed Memory Resources in English Project Work.” In Memory Practices and Learning: Interactional, Institutional and Sociocultural Perspectives, edited by Å. Mäkitalo, P. Linell, and R. Säljö, 153‒186. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- O’Neill, E. M. 2016. “Measuring the Impact of Online Translation on FL Writing Scores.” IALLT Journal of Language Learning Technologies 46 (2): 1‒39.

- O’Neill, E. M. 2019. “Training Students to Use Online Translators and Dictionaries: The Impact on Second Language Writing Scores.” International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning 8 (2): 47‒65. doi:https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsll.2019.4002.

- Sacks, H., and E. A. Schegloff. 1979. “Two Preferences in the Organization of Reference to Persons in Conversation and Their Interaction.” In Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology, edited by G. Psathas, 15‒21. New York: Irvington.

- Schegloff, E. A., G. Jefferson, and H. Sacks. 1977. “The Preference for Self-correction in the Organization of Repair in Conversation.” Language 53 (2): 361‒382. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1977.0041.

- Seedhouse, P. 2004. The Interactional Architecture of the Language Classroom: A Conversation Analysis Perspective. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Stapleton, P., and B. Leung Ka Kin. 2019. “Assessing the Accuracy and Teachers’ Impressions of Google Translate: A Study of Primary L2 Writers in Hong Kong.” English for Specific Purposes 56: 18‒34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2019.07.001.

- Stivers, T., L. Mondada, and J. Steensig. 2011. “Knowledge, Morality and Affiliation in Social Interaction.” In The Morality of Knowledge in Conversation, edited by T. Stivers, L. Mondada, and J. Steensig, 3‒24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stoewer, K., and N. Musk. 2019. “Impromptu Vocabulary Work in English Mother Tongue Instruction.” Classroom Discourse 10 (2): 123‒150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2018.1516152.

- Vetenskapsrådet [Swedish Research Council]. 2017. God Forskningssed [Good Research Practice]. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet. Accessed 9 May 2021. https://www.vr.se/analys/rapporter/vara-rapporter/2017-08-29-god-forskningssed.html