Abstract

The theme of this article is how the challenge of sustainable mobility has been dealt with in urban planning and urban development in the metropolitan areas of Copenhagen (Denmark) and Hangzhou (China). The two metropolises have followed different trajectories in their land use and transport infrastructure development since the 1990s. Land use policies in Copenhagen have to some extent been explicitly geared towards limiting traffic growth, to a less extent in Hangzhou. In both cities, public transport improvements have been combined with road capacity increases. The trajectories of the two city regions reflect the dominating ideas among planners and public decision-makers, as well as a number of different economic, political, social, topographical and cultural conditions.

1. Introduction

This article deals with how two cities located in very different geographical, social, economic and political contexts have acted on the challenge of sustainable mobility in their urban planning and development since the 1990s. The investigated cities are Copenhagen in Denmark and Hangzhou in China. By ‘cities’ we here refer to the functional urban regions, or metropolitan areas, independent of municipal or other administrative–territorial borders.

Needless to say, the challenge of a sustainable land use and transport planning is of a different nature in cities at different stages of economic and infrastructural development. In most West European, North American, Australian and Japanese cities, the mobility level has been high for several decades, including a high rate of private car ownership and an extensive urban road network and parking facilities. Especially in Europe and Japan, this infrastructure is combined with high standard public transport systems (buses, light rail, commuter trains and in the larger cities also metro lines). In comparison, the urban populations of non-OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries generally have much lower mobility levels both in terms of public transport opportunities and car travel (especially the latter). However, certain among these countries, especially China has experienced high economic growth involving rapidly increasing housing standards and car ownership rates for some decades. In these cities, many of the same traffic- and transport-related environmental problems as in the cities of Western developed countries are becoming increasingly manifest.

Copenhagen is the capital of a ‘mature’ high mobility country whereas Hangzhou is the capital of the Chinese Zhejiang Province, where individual motorized mobility has not yet reached the levels of European countries. This study has made a twofold comparison: the spatial urban development and the ways planners and decision-makers involved in the development of the two cities have understood, interpreted, formulated policies and finally acted in relation to transport and land use in a sustainability context during the period since the early 1990s, with an aim to explain reasons for common traits and differences. The investigated period has been chosen with an aim to cover the main time span during which sustainable development has been on the agenda of urban planners. The topic of sustainable development entered the international political agenda in the wake of the report ‘Our common future’ (WCED Citation1987) and has, in particular, been an important part of the vocabulary of politicians, administrators and planners since the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 1992.

By identifying favourable circumstances as well as obstacles to sustainability, this study has aimed to illuminate some of the basic conditions for sustainable land use and transport infrastructure policies. Due to the complexity of conditions influencing urban development, theories focusing on different aspects of reality need to be combined in order to explain differences and similarities between the trajectories followed by the two cities. The project has therefore taken a clearly interdisciplinary approach, attempting to integrate contributions from theories covering different fields, including theories of spatial development and transformation of cities, theories of path dependency, theories of political economy, discourse theories and theories about transportation impacts of urban land use and infrastructure development. Below, we will, in particular, focus on the two latter categories of theories.

Several studies in cities across the world have demonstrated that dense and concentrated urban development contributes to lower overall travelling distances, lower shares of car travel and lower energy use for transport than low-density spatial expansion of the urban area (Newman and Kenworthy Citation1999; Stead and Marshall Citation2001; Næss Citation2006, Citation2009, Citation2010; Zegras Citation2010). These relationships are important arguments in favour of the compact city as a sustainable urban form (Commission of the European Communities Citation1990; Jenks et al. Citation1996). Moreover, in cities with congestion on the road network, the relative speeds of car and public transport are important to the inhabitants' choices of travel modes. The same applies to the availability of parking facilities. Road capacity increase in order to reduce congestion will usually release a latent demand for space on the roads and thus induce an increase in car traffic, whereas faster and better public transport may have the opposite effect (Standing Advisory Committee on Trunk Road Assessment Citation1994; Mogridge Citation1997; Næss et al. Citation2001; Noland and Lem Citation2002). In line with above theories, the investigation of spatial urban development in the case cities has focused on land use (notably urban density and the location of new residences and workplaces relative to the metropolitan centre structure) and the provision of transport infrastructure (notably road capacity increases and improvements in the public transport system).

The dominating ideas among land use and transport infrastructure planners and public decision-makers are of particular interest in our study. Such ideas may sometimes converge into doctrines about urban development (Faludi and van der Valk Citation1994). A doctrine could be understood as a ‘hegemonic discourse’ within a field of society (Hajer Citation1995). Since land use and public investments are usually under public control via legal measures and public funding, we may assume that the public decision-making processes are important factors in explaining the actual outcome. The opinions among planners formulating proposals for urban land use and infrastructure development, and the discourses of the professional communities to which they belong, were therefore important potential explanatory factors to be examined. However, we must also seek explanations on market forces and social and cultural changes in civil society.

The case studies of the two metropolitan areas have been carried out using fairly similar research methods, yet adapting to local contexts and data availability. Empirically, the so-called backward mapping approach (Elmore Citation1985) has been employed, where the urban development that has actually taken place in the case cities has first been observed, with subsequent tracing of main actors and mechanisms behind the observed events. Besides document studies including plans, policy documents and articles in professional journals, we also conducted several in-depth and semi-constructed interviews with land use and transportation planners, policymakers and politicians for each city. shows the empirical data sources in each of the two case studies.

Table 1. Empirical data sources in the Copenhagen and the Hangzhou case studies

In Section 2, the two case city regions will be presented. Thereupon (Section 3), the spatial urban development of the metropolitan areas of Hangzhou and Copenhagen will be outlined, followed by a discussion of conditions and driving forces that may explain similarities and differences in the trajectories followed in the two metropolitan areas, as well as barriers to sustainable development (Section 4). In Section 5, some concluding remarks are offered.

2. The case cities

Copenhagen metropolitan area,Footnote1 the capital of Denmark, had in the beginning of 2010 about 1.89 million inhabitants, of which 1.81 million in urban settlements of at least 200 inhabitants and the remaining population in rural areas. The whole metropolitan area covers an area of 3132 km2. Among the inhabitants living in urban settlements, 1,228,000 are in the continuous urbanized area and the remaining 580,000 in 17 surrounding municipalities outside the continuous urbanized area. The metropolitan area has had a quite moderate population growth during the latest couple of decades, yet with a somewhat higher rate during the most recent years. Similar to many contemporary European cities, Copenhagen metropolitan area's trade and business are dominated by service and knowledge industries, with a rapid decline in the number of jobs in manufacturing industries since the 1970s, especially in the municipality of Copenhagen. From 1993 to 2006, the average annual economic growth in gross domestic product was about 2%.

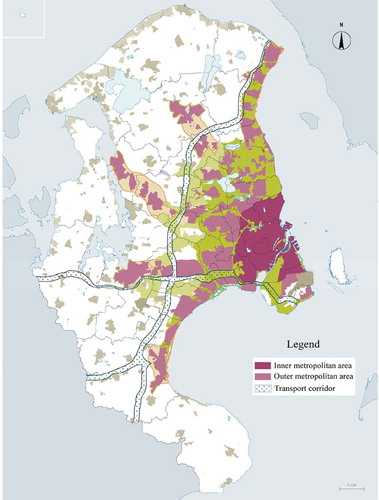

The inner city of Copenhagen has an unchallenged status as the dominating centre of the city region. The central municipalities of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg, making up only 3.4% of the area of Copenhagen metropolitan area, have one-third of the inhabitants and an even higher proportion of the workplaces. There are also a number of lower order centres. The centre structure of Copenhagen metropolitan area could be characterized as hierarchic, with downtown Copenhagen as the main centre, the central parts of five formerly independent towns now engulfed by the major conurbation as second-order centres along with certain other concentrations of regionally oriented retail stores, and more local centre formations in connection with urban rail stations and smaller size municipal centres at a third level ().

Figure 1. The finger structure of Copenhagen metropolitan area. FootnoteNotes.

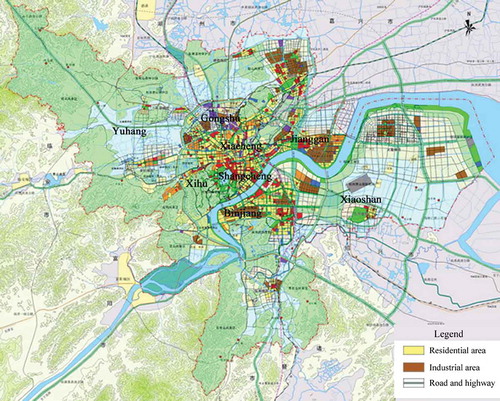

Hangzhou is the capital and the economic, cultural, science and education centre of the Zhejiang Province, a national historical and cultural city and an important tourism city. It is one of the central cities in the Yangtze River Delta and the transportation hub in southeastern China. The whole municipality covers an area of 3068 km2 consisting of eight districts: Shangcheng, Xiacheng, Jianggan, Xihu, Gongshu, Binjiang, Xiaoshan and Yuhang (). The metropolitan area is planned into a hierarchic polycentric structure, with one clear major centre (the inner parts of the city), three second-order centres and six third-order centres. So far, the major centre has the highest concentration of workplaces, stores and other service facilities compared with the lower order centres, some of which have not been completely developed. Among others, Shangcheng, Xiacheng, Xihu, Gongshu and the western part of Jianggan are often referred to as the inner city where the major centre is located. Binjiang, the old centre of Yuhang in the north, and the eastern part of Jianggan are characterized as the second-order centres. In 2001, in order to secure larger geographic space for urban development, the Xiaoshan and Yuhang districts were merged into the Hangzhou metropolitan area where the third-order centres are mainly located. There is a lake (West Lake) of about 10 km2 surrounded by green hills and parks close to the city centre, and the Qiantang River flowing across the city.

Figure 2. Eight districts comprising Hangzhou metropolitan area and its land use plan. FootnoteNotes.

Hangzhou metropolitan area is a forerunner in economic growth with an annual growth rate of more than 11% over the period 1978–2008. Industry is a significant trade, but also tourism, education and other service trades are becoming increasingly important. At the end of 2008, the number of permanent residents within ‘Hangzhou urban area’ (a concept corresponding roughly to the way that the metropolitan area of Copenhagen has been demarcated) was 5,447,000. The metropolitan area has experienced a rapid population growth during recent decades. Between 1991 and 2008, the permanent population increased from 3.4676 million to 5.447 million.

In the metropolitan area of Copenhagen, the mobility level has traditionally been relatively low compared with other European city regions. However, it has increased considerably during the recent 15 years, and in 2008 half of all households had one or more private cars. In Hangzhou, motor vehicle ownership has until recently been very low. Since 2004 there has, however, been an almost explosive growth in car ownership as well as ownership of other motor vehicles. Car ownership increased from 0.7 private cars per 100 households in 2000 to 17.8 cars per 100 households in 2008. Motorcycle ownership grew at similar rates, while ownership of electronic bikes increased from 5 to 36 per 100 households during the same period (Hangzhou Statistical Yearbook Citation2008).

3. Actual spatial development

3.1. Changes in urban population densities

In Copenhagen, the statistics on the size of the urbanized area within the metropolitan area as a whole cover only the period since 1999, but for the continuous urban area of Copenhagen available land cover data exist for selected years over the period since the mid-1950s.Footnote2 summarizes some important features of the land use development in the metropolitan areas of Copenhagen and Hangzhou. Copenhagen metropolitan area has a long history of spatial urban expansion in the second half of the twentieth century, in spite of low and for long periods even negative population growth in the decades prior to 2000. In 1955, the population density within the continuous urban area of Copenhagen (comprising approximately 70% of the metropolitan population) was 48 persons per hectare, dropping to 38 persons per hectare in 1970 and further down to 31 persons per hectare in 1986 (MOLAND Project Citation2010). This was the period of the ‘single-family home boom’, when half of all existing single-family houses in Denmark were constructed in the course of two decades (Danish Architecture Center Citation2011). In Copenhagen metropolitan area, there was a substantial outmigration from the two central municipalities of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg to the suburban municipalities, especially in the 1970s and 1980s, accompanied with low-density residential development in the latter and a sharp decline in population densities within Copenhagen and Frederiksberg. The population in the municipalities of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg was thus reduced from 728,000 in 1971 to 551,000 in 1991, while the size of the urbanized land in these municipalities remained virtually the same.

Figure 3. Population density development in Copenhagen metropolitan area and Hangzhou metropolitan area. Persons per hectare of urbanized land. (a) Population density development within the urbanized land of Copenhagen and Hangzhou metropolitan areas. (b) Population density development within the continuous urbanized area of Copenhagen and inner city of Hangzhou metropolitan area. (c) Population density development outside the continuous urbanized area of Copenhagen and outside the inner city of Hangzhou metropolitan area. FootnoteNotes.

Since the mid-1980s, the spatial urban expansion of Copenhagen metropolitan area has stagnated, with only small changes in population densities. For Copenhagen metropolitan area as a whole, the population density within the built-up areas increased from 27.4 persons per hectare of urbanized land to 27.7 persons per hectare between 1999 and 2008, that is, by 0.9% (Aalborg University’s Spatial Data Library Citation2009) (). Within the continuous urban area of Copenhagen, the population density has changed from the above-mentioned rapid reduction before the mid-1980s to stabilization (). Here, the population density increased by 1.4% over the period 1999–2008. In the suburbs and, in particular, in the parts of the metropolitan area located outside the continuous urban area of Copenhagen, development has still predominantly taken place as spatial urban expansion (). This outward urban growth has counteracted the densification and concentrated urban development taking place in the inner parts of the metropolitan area. Although this has led to a more transport-demanding and car-dependent urban structure than what would otherwise have been the case (Næss Citation2006), the contribution of sprawl to increasing car dependency has been moderate during the recent decades due to a generally low pace of construction until a few years ago. Anyway, the considerable density increases that have taken place in the municipality of Copenhagen and some of the surrounding municipalities especially during the latest decade represent an important departure from the dominant trend within the metropolitan area until the 1990s.

In Hangzhou, the statistics on the size of the urbanized area available are for the years 1991, 1999 and 2008 (Wang et al. Citation2009). Although the city was already at the outset densely built up, during the recent two decades (between 1991 and 2008), the population density of the whole metropolitan area has decreased from 106.1 persons per hectare of built-up area to 62.8 persons, that is, a decrease by 40.8% (). The decrease of population density was stronger over the period 1999–2008 than the period 1991–1999. This indicates that despite the fact that population growth has been rapid in Hangzhou, the expansion of built-up areas has been much faster. The pace of growth in the built-up areas has sped up, with the annual growth rate increasing from 18.11 km2 annually in the 1990s to 44.04 km2 annually in the 2000s. Comparing the population densities among the eight districts, generally, there is a clear tendency to decreasing density of population when the distance from the city centre increases. The population density in the inner city (Shangcheng and Xiacheng) is considerably higher than in the outer parts of the metropolitan area, and in these districts it has also increased.

The development in the inner city of Hangzhou, that is, Shangcheng and Xiacheng, as well as Xihu has taken place as densification. However, the outer parts of the Hangzhou metropolitan area have experienced a sharp decline in population density, especially in Yuhang, Xiaoshan, Jianggan and Binjiang (). The densification in the inner city was outweighed by the density reduction in the outer areas, leading to an overall decline in the population density for the metropolitan area as a whole. However, most of the outward urban expansion that has taken place in Hangzhou and in the second-order towns has been at fairly high densities, very different from the one-storey single-family home development so typical for much of the urban expansion in Copenhagen metropolitan area in the decades up to the mid-1980s. The major development contributing to a relatively low density in the outer parts of the Hangzhou urban region is three development zones, namely Hangzhou Hi-tech Industry Development Zone in Binjiang, Hangzhou Economic Development Zone in Jianggan (Xiasha) and Xiaoshan Economic and Technological Development Zone, which have locations and densities that are not favourable, seen from the perspective of transport energy minimizing. Another contributing factor is that the outer parts, especially Yuhang and Xiaoshan hold a larger agricultural population (around 61% among the registered population in 2008) living in less dense settlements. It is important to see the low population density in Yuhang and Xiaoshan in the light of this. The fact that urban expansion has been faster than the population growth in the outer parts of Hangzhou is in line with the research demonstrating that Hangzhou began suburbanization in the 1980s and that this process sped up in the 1990s (Feng Citation2002a).

3.2. Spatial development of residences and workplaces

In the metropolitan area of Copenhagen, residential development during the latest decade has shown a trend of concentration. The shares of the metropolitan population living in the core municipalities have remained fairly constant since the mid-1990s, distinct from a decreasing trend in the preceding decades. New dwellings in the 1990s were built on average 20 km from the city centre of Copenhagen, compared with the 1970s, when residential development took place on average 23 km from the city centre. This also applies to workplace development in general. The location of new white-collar workplaces has to a high extent been in accordance with the Dutch ‘ABC principle’ for environmentally sound location of workplaces (Verroen et al. Citation1990), although some office development has also taken place at transport-wise unfavourable locations. To a larger extent in the municipalities of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg than in the outside areas, new office workplaces during the years 2000–2004 have been located less than 500 m from an urban rail station or less than 1000 m from a major public transport node. During the latest 4 or 5 years, a higher share of new dwellings and offices has been built in the central municipalities of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg than the previous years when residential and commercial development took place predominantly at suburban locations. Thus, a shift from suburbanization to reurbanization seems to be underway in Copenhagen metropolitan area.

In the case of Hangzhou, residential development has experienced two phases since the 1990s. In the 1990s, although new residential buildings were built outside the inner city, renovation of old housing areas in the inner city by clearance of old residential buildings and construction of new ones with higher densities were the major initiatives on residential development. This is illustrated by the fact that the total floor area of clearance from 1986 to 1999 was 8.75 million m2 (Feng Citation2002a), while the completed floor area over the same period was 17 million m2 (excluding Yuhang and Xiaoshan). The period since 2000 can be characterized as construction boom and decentralization of residential buildings. From 2000 to 2008, 47.2 million m2 of floor area were completed, accounting for approximately 80% of the total floor area completed over the years from 1991 to 2008. At the same time, substantial growth in the residential buildings took place in the peripheral parts of the inner city and spread to the outskirts and to the economic and technological development zones. The decentralization of residential development is a result of land scarcity and high density in the inner city making further density increase difficult. The decentralization of residential development was reinforced by construction of transport infrastructures and increased ownership of private cars. Combined with lack of overarching guidance from the local government to the residential development led by private sectors, this has resulted in an increasing number of residences in the far suburban areas, at odds with the development planning objectives for the metropolitan as a whole.

As regards the development of workplaces, Hangzhou experienced suburbanization of industry in the 1990s. Factories in the inner city were substantially moved out to the outskirts and three development zones, while service sectors have been concentrated in the inner city and low-order city centres as substitutions for the industry (Feng Citation2002b). This has influenced the locations of white-collar and blue-collar workplaces. However, hitherto, compared with the inner city, not many employees are working in the outer parts of the metropolitan area. Since the residential development has been decentralized in the latest decade, more and more residents living in the outskirts have to commute between residences and workplaces in the city centre. Moreover, the economic development zones do not only have factories but also have clusters of universities providing jobs for people with high educational levels. Because the majority of the universities and university departments in the outer parts of the metropolitan area were moved out from the inner city, the residential locations of staffs, which used to be close to the universities, are now far from the workplaces. Due to the less developed infrastructure and city facilities in these areas, those people do not prefer to move their homes and thus have to rely on motorized transport for commuting.

3.3. Provision of transport infrastructure

Copenhagen has made considerable investments in a new Metro, but substantial road capacity increases have also taken place. Together with the low-density suburban development this has contributed to a steady and rapid growth in car traffic. During the period 1995–2007, passenger transport carried out by car (passenger km) within Copenhagen metropolitan area increased on average by 23% when adjusted for population growth, whereas public transport decreased by 7% (Region Hovedstaden Citation2009). The combined, and quite costly, strategy of investing in increased road capacity combined with some improvement of public transport has generally contributed to higher mobility, but has also induced people to change travel mode from public transport to car travel (Næss et al. Citation2001; Strand et al. Citation2009). On the positive side, the amount of bike travel has increased, facilitated by a continual improvement of a bike network that was probably Europe's best already in the 1980s.

In Hangzhou, there has also been considerable road construction in the form of ring motorways and arteries, elevated highways through the inner city and extended main roads on the ground. The length of urban roads within the metropolitan area nearly doubled between 2001 and 2005, and the area occupied by roads increased by as much as 117% during this 4-year period. The latter figure reflects a substantial construction of new multilane roads. Some of the addition of new lanes in the main streets inside the city has taken place at the cost of previous bike paths along these streets. Over the period 2000–2009, passenger transport carried out on road (passenger km) increased by 94%. Adjusted for population growth, this corresponds to a real growth of 68% (Transport Bureau of Hangzhou Citation2011). Despite the generally high-density urban development of Hangzhou metropolitan area, car ownership has increased at an astonishing rate, cf. above. Congestion has therefore become worse and worse. As a countermeasure, the construction of a metro network began in 2006, and its first part is expected to be opened by the end of 2011.

4. Condition and driving forces

As can be seen from the previous sections, Copenhagen and Hangzhou have followed different trajectories in their land use and transport infrastructure development during the latest decades, but there are also noticeable similarities. The extent to which the actual spatial development is shaped by the land use plans and transport plans or have been produced by market forces is of course a matter that can be disputed. The land use development that has taken place in the two case areas is, however, to a high extent in accordance with municipal land use plans. As regards the national land policies, in Hangzhou, densification in the inner city is in line with the national policy and is also driven by market forces, while outward expansion in the outer areas is to some extent less consistent with the national land policies. In Copenhagen too, the local traces of national planning policies are evident in the inner parts of the metropolitan area but less clear in the outer municipalities. The contents of plans and policies, judged against criteria of urban sustainable development and mobility, are highly related to the interpretation of the term ‘sustainable development’ by planners and decision-makers and therefore their strategies to deal with this challenge. The same applies to the observed trajectories and visions for future development. In addition, natural, economic, political and cultural conditions in each case exert influence on the perceptions as well as the decisions made by planners and policymakers. Below, we shall look at these conditions and driving forces and thereupon discuss barriers to sustainability.

summarizes some key findings from the case studies in Copenhagen and Hangzhou as regards actual urban development, traffic development, conceptions of urban sustainability and causes of sustainability successes and failures. The table will be explained in detail in the following sections.

Table 2. Comparison of actual urban development, traffic development, conceptions of urban sustainability and causes of sustainability successes and failures between Copenhagen and Hangzhou

4.1. Interpretation of sustainable development

4.1.1. General understanding of sustainable development

The concept of sustainable development has entered the agenda of urban planners and policymakers earlier in Scandinavia than in China. In both Denmark and China, ‘sustainable development’ is interpreted as a combined environmental, social and economic concept as put forward by the WCED (Citation1987). In Denmark, the concept has to a higher extent than in the other Scandinavian countries been redefined in accordance with a neo-liberal agenda focusing on the competitiveness of cities in the globalized economy. In Denmark too, however, there are spokespersons interpreting sustainability mainly as a challenge of reducing the environmental impacts of economic development. In the Copenhagen case, the concept of sustainable development is interpreted mainly as an environmental challenge and objective in Copenhagen's Municipal Plans (2005 as well as 2009) and the National Planning Strategy issued in 2000 by a social democratic government. In the other investigated documents (cf. ), including the 2006 National Planning Strategy put forth by a conservative–liberal government, the term is used as a combined environmental, social and economic concept with emphasis on the latter understood as competitiveness.

In China, the general interpretation of sustainable development refers to the definition used by the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987, attempting to reconcile economic growth with environmental protection and social equity with a highlight on the environmental dimension. However, the economic dimension is considered the basic one. It is thus a matter of ‘protecting the environment during development’ – absolute environmental protection is rejected. Efficient use of scarce resources in order to meet needs while avoiding to erode the resource base seems to be a common interpretation. In this sense, economic growth has the hegemonic status in sustainable development, subordinating environmental protection. In Hangzhou, the actual application of the concept of sustainable development in all the investigated plans is confined to environmental aspects, even though it is presented as a combined three pillar development.

4.1.2. Sustainable urban development and land use

Against sprawl and in favour of compact city have been main interpretations for sustainable land use and urban development in both cities, although in Hangzhou the compact city is not explicitly referred to as a model for development. However, the motivation and strategies towards this are different. In Copenhagen, inner-city densification as well as suburban development close to urban rail stations understood as decentralized concentration are main strategies. Relationships between land use and travel form part of the rationale for the finger-based developmental strategy. This strategy is, in particular, based on knowledge about the influence of neighbourhood-level urban characteristics (proximity to stations) on travel, whereas knowledge about the transportation impacts of proximity to or distance from the main city centre is not emphasized to the same extent. On the other hand, in Copenhagen metropolitan area as well as in the general community of Danish urban planners there has also been a counter-discourse advocating low-density decentralization. According to its proponents, such development is considered to be best in line with residential preferences among the population. Moreover, some debaters consider offering ample areas for commercial development in rural and natural surroundings as a way of promoting ‘economic sustainability’ by attracting international companies to the region.

The main motivation for urban containment in China is farmland conservation. The fact that urban development demands huge space while farmland resources are relatively scarce to support the population requires an intensive utilization of land. Compact urban developmental patterns are therefore preferable in such context. In China, compact city development is also considered to contribute to more diverse urban environments and hence to improve the vitality of the cities, create job opportunities and strengthen the competitiveness of the cities (Qiu Citation2006). Even though compact city is also considered to be conducive in minimizing transportation, which is a major argument for such development pattern in Western countries, for example, Copenhagen, this aspect is less emphasized in China.

In the case of Hangzhou, efficient land use is a key sustainability element in the Main Land Use plan. The Master Plan advocates hierarchical polycentric development with ‘one main city, three sub-cities, double centres and biaxial, six groups and six eco-zone belts’. It does, however, also emphasize intensive and economical use of land and improvement of land use efficiency in the central area of the city as key principles. District level jobs–housing balance is part of the rationale for polycentric development. In addition, it is presented in the plans that the location of residences should consider the availability of transport infrastructure and proximity to the city centre. Despite the relatively low density in the lower order urban settlements where more area-consuming development has been taken place in the latest decade, Hangzhou is far from being characterized by sprawling development as in American cities and also the historical suburban development in Copenhagen metropolitan area. The low-density development in the lower order urban settlements can be partially regarded as the response to the Master Plan aiming to decentralize population from the inner city to outer parts of the metropolitan area. Such planned decentralization also took place in Copenhagen metropolitan area (especially in the period from the 1960s to the 1980s), but at much lower densities than in Hangzhou.

4.1.3. Sustainable urban mobility

In both city regions, improving public transport has been a main strategy for sustainable mobility. In Hangzhou, the metro now under development is regarded as an important sustainability measure. A main motivation for supporting the metro is that it will not be possible to meet the rising mobility needs of Hangzhou's inhabitants through road development only – the building stock implies that there is not enough available space for that. Certain restrictions on the use of cars (road pricing, parking policies, environmental zones) have been proposed in the two cities, but so far not much of this has been implemented. Moreover, in both cities, increasing road capacity has been part of the transport policy, partly justified by sustainability arguments. In Copenhagen and Hangzhou, the motivation for road building has mainly been to eliminate existing or projected future congestion. However, in Copenhagen, opinions are more divided as regards this issue than in Hangzhou where there seems to be consensus among planners and politicians that providing sufficient road capacity is one of the sustainable transport methods to meet the inevitable traffic growth. In addition, in Hangzhou, transport infrastructure is considered being underdeveloped and lagging behind the other urban development. In Hangzhou too, environmental protection is as yet given a clearly subordinate position compared with infrastructure expansion: ‘paying attention to reasonable use of resources and environmental protection during the process of transport scale expansion’ as presented in the transportation plan. The environmental problems of car travel must, according to this perspective, be solved by more environmentally friendly vehicle technology.

4.2. Influence of planners and policymakers

In Copenhagen metropolitan area, development close to urban rail stations in the fingers of the Finger Plan has been advocated strongly by the national planning authorities. They have, however, for a long period been rather lukewarm towards densification in the municipality of Copenhagen, especially as regards workplaces. The municipality of Copenhagen has therefore had to negotiate with the regional and national authorities for more jobs to be located within its limits. Only during the most recent years has growth in jobs and population within the municipality of Copenhagen been accepted by national authorities. This is one of the reasons why urban densification was until a few years ago quite modest in the municipality of Copenhagen. When the national government restrictions on population and employment growth in the municipality of Copenhagen were eventually relaxed, densification stood out as a natural strategy since land reserves within the municipal borders are small. Dense and compact development was therefore seen as the only way to accommodate substantial growth in the number of inhabitants and jobs.

Transport infrastructure policies in Copenhagen metropolitan area have generally been less oriented than land use policies towards the objective of limiting growth in car traffic. The Ministry of the Environment has been a strong proponent of compact urban development and location of development close to urban rail stations. A main purpose of these policies has been to reduce traffic growth. On the other hand, the national transport authorities have generally facilitated higher mobility, investing in public transport as well as highways. Partly, these differences reflect different organizational cultures in the two ministries (Strand and Moen Citation2000; Sørensen Citation2001). According to some interviewees, there is a clearly car-oriented professional culture within the Ministry of Transport and the Road Directorates. Whereas planners, geographers, political scientists, law scientists and so on make up a large proportion of the staff of the planning department in the Ministry of the Environment, economists have a much more prominent position in the Ministry of Transport. The latter group tends to favour cost–benefit analysis as a method for project evaluation. This sometimes leads to recommendations deviating from those based on adopted political goals.

Despite objectives of reducing car travel, the municipalities have often lobbied towards national transport authorities for the realization of local road projects. Arguably, a fragmented organizational structure and a funding system encouraging local mobilization for state infrastructure funding make up an incentive structure inducing municipalities to prioritize road construction over measures to improve the conditions for public and non-motorized modes (Osland and Longva Citation2009). While there has been some political disagreement on transport policy priorities (with the right being more positive and the left more negative to road development), disagreement on land use issues follows party divides to a much lesser extent. There has, for example, hardly been any politicized debate about the development of low-density single-family housing areas in Copenhagen metropolitan area which are inevitably linked with more car-dependent travel behaviour.

In Hangzhou, a pro-growth coalition with the leadership of local government in dealing with urban development, attempting to achieve the strongest possible local economic growth has been identified (Qian Citation2007). Since the local leaders’ political and economic performances are evaluated by the pace of economic growth in the locality, the local government is enthusiastic to promote the economic gains and government revenue from urban development especially by urban land leasing, which becomes a driver of urban expansion. One important counteracting force of this local growth tendency in land use is the national farmland conservation policy, which is strongly emphasized in the Land Administration Law of the People's Republic of China and at all levels of land use plans. The Land Administration Law includes strict restrictions against conversion of farmland into land for construction, particularly for cultivated lands. However, due to the lack of effective supervisory mechanisms, local governments often exceeded their authority illegally to approve land use in order to fill their own coffers (Xie et al. Citation2002). The poor implementation of central government policies at the local level is related to the political system in China, which will be elaborated below.

In China, land use plans and transport plans are legal prerequisites for any urban development and transport infrastructure construction. Most often, planning has been used as a tool for development rather than for development control. Planning is most of the time conducted on the premise of a growing demand for land, housing and traffic. Finding ways to accommodate growth in population, land use, traffic and building stock is considered the major task of urban planning. Urban planners are usually under great pressure from local government to play an active role in the competition with other local jurisdictions for capital and industries (Xie et al. Citation2002).

Enhancement of public transport in Hangzhou is to some extent a result of the perception of the growth coalition. The metro lines under construction in the first place are not located in the part of the city where most residences are located and the travel demand of residents is most urgent. However, an important motivation is to increase land prices of undeveloped areas along the metro lines. This could partly explain why the spatial arrangement of the metro lines has been disputed in public. Apart from contributing to meet the inhabitants’ need for travel, the construction of metros also carries the local government's intention of increasing land price of some less developed areas by providing transport infrastructure. The latter motivation appears to have been the most pronounced in influencing the policymakers. This has stimulated urban sprawl by expropriation of neighbouring rural land while land in the already urbanized areas remains underutilized.

A similar motivation can be seen for parts of the metro development in Copenhagen, where critics have claimed that the metro lines going to the southeast of the city centre (Ørestaden) were built for bringing people to the airport and to new offices close to the airport, not for the people actually living along the lines. Against this, the planners and decision-makers in charge have argued that these parts of the metro run where people are going to live, whereas the neighbourhoods (within this part of the urban region) where people already live are covered by other public transport services. Anyway, the new urban districts of Ørestaden have been developed or are planned to be built at fairly high densities and cannot be characterized as urban sprawl.

4.3. Influence of economic, political, natural and cultural conditions

4.3.1. Economic influence

The discourse on sustainable urban development in Denmark has – especially in the present century – had a strong focus on growth stimulation. In China, sustainable urban development has mainly been interpreted as a matter of growth management. Possibly, this reflects the different economic trajectories experienced by the two countries and city regions during the investigated period. Denmark had a high level of affluence at the beginning of the investigated period, but periods of economic stagnation and recession were pronounced in the 1980s and 1990s. In China, economic growth has been formidable for nearly three decades, although starting from a very low level of material consumption. Market-oriented economic reforms in the 1990s gave rise to urban entrepreneurialism, but in recent years there has been a trend of stronger national government intervention in order to prevent redundant infrastructure construction and negative environmental and social consequences of inter-municipal competition (Wu and Zhang Citation2009). For many years, negative environmental impacts of growth were not perceived as a serious problem. Gradually, however, environmental sustainability has become a concern, and the task of urban planners has increasingly been understood as one of reconciling the rapid economic development with the protection of natural resources, especially farmland.

In the case of Hangzhou, growth management is reflected in the Master Plan by a policy of channelling urban development to certain directions to avoid ecologically vulnerable areas. Moreover, tourism is an increasingly important trade in Hangzhou, and this makes a strong case for protecting the beautiful landscapes surrounding the city against urban development. In Copenhagen metropolitan area, low growth in jobs and population has put growth creation on top of the agenda. In this context, strict land use regulations have been commonly held to scare away investors, in particular, in the municipalities in the outer parts of the region.

4.3.2. Political influence

The political conditions for planning in Copenhagen metropolitan area have been characterized by a high degree of market responsiveness, especially during the latest decade. In addition, strong inter-municipal competition, combined with the availability of large vacant areas released for urban expansion in outer-area municipalities long ago, has until recently made it difficult for higher level authorities to maintain the national objectives of decentralized concentration of office and residential development close to urban rail stations. In the Finger Plan 2007, which has the status of a National Planning Directive, a sharpened regulation of the scheduling of development within the urban zone areas, with first priority given to areas close to stations, has been introduced as a remedy to prevent scattered development all over the oversized developmental areas.

In Hangzhou metropolitan area, compared with the Copenhagen region, state-owned land and strong public control of land use have secured strong vertical coordination, at least as regards the amount of land released for urban development. Local governments below the provincial level have no authority of approval for land expropriation. Land use plans are employed to arrange and allocate land resources for a period of time (10 years on average) and space (Tao et al. Citation2007), in which the upper limits of built-up area and farmland protection area are stipulated. Each level of plan from state, province and city to county should not go beyond the scope and scale designated in the higher plans. However, since the economic reforms in China in the late 1970s, the highly localized privatization process combined with less emphasis on political reform means that local governments now have to face an emerging market economy subject to the constraints of an old political system (Qian Citation2008). For one thing, this has led to differences of interests between the central and local governments and thus difficulties in implementing the central government policies by local government decisions. For another thing, the conflicts between market-oriented development and old political framework in the socialist system at the local level result in that the location of developmental areas has been coordinated to a lesser extent.

The above-mentioned differences in the political contexts of planning of course reflect the different political ideologies and systems characterizing the Danish and Chinese contexts. Neo-liberal ideas have generally had a strong influence in Denmark during the recent decade, especially since the elections in 2001, resulting in lower willingness to regulate the market demand for building sites, composition of housing types or transport infrastructure. In China, strong policy instruments remain in the hands of the national state alongside with a strong reliance on market mechanisms in order to deliver economic growth.

4.3.3. Natural and historical influence

Copenhagen has undergone a change from spatial urban expansion in the second half of the twentieth century to urban densification after 2000 and plans to continue the latter trend. This should not, however, lead us to believe that Copenhagen has pursued a more compact development than Hangzhou. In Hangzhou, population densities are considerably higher than in Copenhagen (cf. ). The possibilities for densification were therefore at the outset much higher in Copenhagen.

In Hangzhou, densification has usually implied the replacement of existing buildings with taller ones. The tension between agricultural land preservation to support a large population and land demands for urban growth has been long-standing. Besides strict national policies for farmland conservation, the potential non-agricultural areas for urban expansion are often important recreational areas like the West Lake and its surrounding forested hills. The urban demarcation against landscape protection areas for recreational and ecological purposes (e.g. Hangzhou Zhijiang National Tourist and Holiday Resort and West Lake Landscape Protection Area) in the Master Plan channels urban development to avoid these places. Due to the fact that three quarters of Hangzhou are surrounded by mountains, urban spatial expansion has been more costly in Hangzhou than in Copenhagen. In Copenhagen metropolitan area, the Finger Plan has since its adoption in 1947 had the status of a doctrine for urban development. However, although this plan presupposed the protection of ‘green wedges' between the ‘fingers’, it was basically a plan for urban spatial expansion, concentrated along five main transport arteries. Considerable parts of the area between the fingers were farmlands, and areas between the ‘fingers’, like the British Green Belts, were thus to some extent only a sort of voids, without much user value for the urban population. The designation of these areas as areas for non-development was not backed by strong recreational interests, at least not in the outer parts. Neither has there been much emphasis on saving farmland, which is an ample resource in Denmark.

4.3.4. Cultural influence

The cultural context has probably also been more conducive to compact urban development in Hangzhou than in Copenhagen. In Hangzhou, inhabitants have a tradition for dense living and biking. However, ‘reaching western standards’ is a widely held goal, and this is probably an important driving force of the growth in car ownership, other motor vehicles and spacious and luxury low-density single-family dwellings in the places with beautiful landscapes (e.g. in the Zhijiang National Tourist and Holiday Resort). In Copenhagen metropolitan area, single-family homes are still the preferred dwellings for many inhabitants, and there is a weaker tradition for outdoor recreation in natural areas than in the other Nordic countries. In addition, ‘cafe culture’ and urban living have gained increased popularity during the recent couple of decades in many European cities (Bjørnskau and Hjorthol Citation2003; Hjorthol and Bjørnskau Citation2005), including Copenhagen.

4.4. Barriers to sustainable urban mobility

Lack of coordination is perceived in both city regions as the main barrier to sustainable urban mobility. The lack of coordination exists horizontally and vertically. In Denmark as well as China, downscaling urban governance into lower layers of administrative hierarchy has been pursued as part of liberal reforms of the planning system (Næss Citation2008; Wu and Zhang Citation2009). Although certain regulations have been implemented in both countries to strengthen the possibilities for implementing national land use policies, our material indicates that considerably stronger coordination – horizontally as well as vertically – would be required in order to meet the requirements of sustainable mobility. An important reason for lack of vertical coordination is the different interests among the main actors at different hierarchy levels. In China, the explanation of interest conflicts must be sought in institutional frameworks in relation to land use.

The lack of horizontal coordination is perhaps more pronounced in the Hangzhou metropolitan area than in the Copenhagen metropolitan area. In the Hangzhou case, the lack of coordination pointed at is mainly between the old districts and the new administrative districts within the metropolitan area. Although Hangzhou's municipal land use plan and Hangzhou's Master Plan have considered Yuhang and Xiaoshan districts as part of the metropolitan area, in practice, the implementation of these plans is hampered by the lack of coordination. Such a lack of coordination is mainly attributed to the taxation and financial institutions and distribution of administrative jurisdiction. The gap between plan and practice has led to problems, for example, in land use, transport infrastructure construction, industry distribution and environmental protection making up obstacles to sustainable urban development and mobility. In Copenhagen metropolitan area, arguably, lack of coordination often exists because some actors do not want to take the interests of other entities into consideration. Power relations, for example, between ministries are part of the explanation. General neo-liberal ideas of competition as conducive to efficiency, productivity and economic growth are probably also part of the explanation why there is not a higher degree of coordination, for example, of land use across municipal borders.

In both investigated metropolitan areas, growth in the building has been taken as an unquestionable good. Sustainability efforts in urban development have been understood as a matter of obtaining a (partial) decoupling between growth in the building stock and negative environmental impacts. In the Hangzhou case, considerable attention is given to the challenges posed by population growth and to policies aiming to limit this growth. The growth in floor area per capita in a long term is, however, hardly questioned. The same applies to the Copenhagen regions, where floor area per capita is already among the highest in the world. Growth in transport and mobility has also to a high extent been taken as an unavoidable fact. The task of sustainability policies has then been to channel as much as possible of this growth to public transport and to promote a change to less polluting vehicles. Since it is hardly possible to obtain a 100% decoupling between negative environmental consequences and growth in either the building stock or the mobility, at least not in the long term (Høyer and Næss Citation2001; Næss and Høyer Citation2009), the lack of reflection about limits to decoupling growth from negative environmental impacts could be considered a barrier in itself to the achievement of sustainable urban development.

5. Concluding remarks

In Copenhagen metropolitan area, the development of land use and transport infrastructure has contributed to the development of traffic volumes less favourable in a sustainable mobility perspective for several decades, yet with a stronger tendency towards transport-reducing land use during the most recent years. Hangzhou has been facing the difficult task of accommodating high population growth as well as a rapid increase in floor area per capita without consuming too much of scarce land resources. The sharply increasing traffic volumes experienced in Hangzhou reflect rapidly rising vehicle ownership rates facilitated by economic growth. Hangzhou's policy of economizing on construction land has probably prevented traffic growth from being even faster (Næss Citation2010). In both metropolitan areas, substantial highway development has taken place, but this has not been able to prevent congestion from arising anew. The fact that traffic is increasing in both cities implies that they are both moving in the opposite direction of important goals of sustainable mobility. In Hangzhou, the level of urban motoring is perhaps still below what might be a sustainable per capita level at a global scale, but given the fast rise in vehicle ownership and usage this level is likely to be exceeded in the near future.

The trajectories of land use and transport development observed in the metropolitan areas of Copenhagen and Hangzhou are the results of the combined effects of a multitude of different causal mechanisms. Obviously, the standard density of the existing building stock has played a role. The spatial development in the Copenhagen metropolitan area over the last 20 years owes a great deal to the legacy of planning thinking and investment since the famous Finger Plan was adopted in 1947. What has happened in Hangzhou over the last 20 years has to a much lesser extent been influenced by such a historic background. In view of this, it could be tempting to interpret the different spatial development trajectories of the Hangzhou and Copenhagen metropolitan areas during the last two decades as merely a reflection of their different stages of economic development and levels of car ownership. This would, however, be a much too simplistic conclusion. Although the density decrease seen in Hangzhou metropolitan area since 1990 resembles the one experienced in Copenhagen metropolitan area between the mid-1950s and the mid-1980s, the overall densities in the existing city as well as in the new suburban development in Hangzhou metropolitan area are much higher than what was the case in Copenhagen metropolitan area in the 1950s–1980s. Whereas single-family houses accounted for a high proportion of the land occupied by suburban development in Copenhagen metropolitan area in the 1960s and 1970s, such development only accounts for a small share of suburban development in Hangzhou metropolitan area. The international professional discourse has of course also changed, with environmental sustainability and economizing on construction land becoming more prominent, also in the Chinese context. Moreover, whereas much of the spatial expansion in the Hangzhou region can be attributed to population growth, the number of inhabitants in Copenhagen metropolitan area was somewhat reduced during the spatially most expansive period.

The combination of a low floor area per capita at the outset, strong economic growth during the period and high in-migration to the city has resulted in a very high pace of construction in Hangzhou, compared with the much lower annual growth in the building stocks of Copenhagen. The same is also largely true for transport infrastructure construction. Cultural traditions (a much higher general acceptance of high-density living and high-rise living in Hangzhou than in Copenhagen) and different institutional frameworks for planning and decision-making also play important roles. Political conditions at national and city levels (e.g. a higher or lower willingness to regulate the market demand for building sites, composition of housing types and transport infrastructure) are also important. Nor should the influence of the natural topographic situation be underestimated.

However, the ideas of land use and transport planners matter too. The change in Copenhagen metropolitan area towards a more concentrated urban development after several decades of more or less strong urban sprawl reflects changing planning ideals, changed demands within the housing market as well as new political signals. In addition to limiting the possibilities for spatial urban expansion through land use zoning, planners have made efforts to increase the attractiveness of inner-city living by incorporating cultural and recreational facilities, aesthetic upgrading and traffic calming. Such ‘leverage planning’ (Brindley et al. Citation1996) has influenced housing preferences and drawn the attention of developers towards densification. By contrast, in Hangzhou, the highly concentrated urban development in the inner city has induced planners to decentralize population by means of adopting a polycentric urban structure to avoid oversized continuous urban areas. Instead of revitalizing the inner city, the major initiative undertaken has been to develop lower order centres into new growth centres in order to attract migration of population. However, as the centres at the higher levels are highly likely to provide services which are not available in the lower level centres, this could result in an increase in the motorized travel of residents living close to the lower order centres to the main centre.

Even though densification and public transport improvements have taken place in the Copenhagen metropolitan area as a way of decoupling environmental impacts from growth within the field of urban development, the decoupling is relative. Absolute environmental impacts still increase, albeit at a slower pace. This gives rise to questions of whether decoupling is sufficient in the long run as a sustainable development strategy, and whether continual growth should be regarded as an inevitable fact. The Hangzhou metropolitan area also confronts the challenge that non-environmentally harmful growth seems impossible to realize by decoupling strategies. Although densification policies have been historically stronger in China than in Europe, the explosive growth in mobility has considerably counteracted the environmental gains from compact urban development as a decoupling strategy. Moreover, Hangzhou's land use development in the latest decade shows a tendency to loosening the urban containment policies. For Hangzhou, where continual growth is still considered essential to improve the inhabitants' well-being, the most urgent task to confront the challenge is to strengthen decoupling policies and management. For China in a transitional era, the ongoing social, economic and political reforms provide a chance to reshape the institutional organizations to put the ecological rationality on a parallel position with economic rationality. China has since the open door policy in the late 1970s pursued modernization and this modernization should be pulled to the direction of ecological modernization as a decoupling paradigm which is relevant for the situation of China on the way of development when environmental problems become a big concern (Mol and Spaargaren Citation1993; Hajer Citation1995; Mol and Sonnenfeld Citation2000). However, in a long run, it is doubtful whether the ecological system could support the growth of China to the level of ‘western standards’, because per capita increase in consumption level can put huge aggregate strains on the environment due to the large population size. The fact of a finite globe may put a limit to the growth in China. Reconsidering growth as an assumed good will then be necessary for both rich countries and China, with the profound changes such a new frame would entail for the agenda of sustainable urban development.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jin Xue

Jin Xue: Jin Xue received her master’s degree in urban planning and design from Zhejiang University, China, in 2009. She is currently a PhD student at the Department of Development and Planning, Aalborg University, Denmark. Her research interest includes environmental sustainability of housing development and limits to urban growth. She received a Best Paper Award at the 5th conference of international forum on urbanism.

Petter Næss

Petter Næss: Dr.-Ing. Petter Næss is a professor of urban planning at the Department of Development and Planning, Aalborg University, Denmark. He has been engaged in research on sustainable urban development, urban structure and travel, planning theory and driving forces of urban development for many years and has published widely within these areas.

Yinmei Yao

Yinmei Yao: Dr. Yinmei Yao, PhD of Economics, is an associate professor at the Population and Development Institute, Centre for Sustainable Development Research, Zhejiang University, China. Her research interest includes sustainable development, population economics, urbanization and population ageing.

Fen Li

Fen Li: Fen Li, PhD of Economics, is an assistant professor at the Population and Development Institute, Centre for Sustainable Development Research, Zhejiang University, China. Her research interest includes sustainable development, population economics and labour economics.

Notes

Source: Fingerplan (Citation2007).

Source: Hangzhou Urban Planning Bureau (Citation2007).

Sources: Yin et al. (Citation2007), Aalborg University's Spatial Data Library (2009), Hangzhou Statistical Yearbook (Citation2009), Statistics Denmark (Citation2009), Wang et al. (Citation2009) and MOLAND Project (Citation2010).Footnote3

1. The Copenhagen metropolitan area as understood in this article is equal to Greater Copenhagen as defined in the Danish Planning Act.

2. By urban population density we refer to the number of inhabitants per unit area of urbanized land. Urbanized land is defined as areas within the demarcations of urban settlements. Based on the common Nordic definition, the term urban settlement means clusters of houses as long as they have 200 inhabitants or more, and the distance between each house does not normally exceed 50 m (Statistics Sweden Citation2002; Statistics Norway Citation2009). According to this definition, most of the rural settlements in Hangzhou could be counted as urbanized land. In this research, the data for urbanized land in Hangzhou therefore include the area of rural settlements.

3. The data of permanent resident population for 1991 and 1999 were from Hangzhou Population Census. Data of permanent resident population for 2008 were estimated in the report ‘Tendency of demographical change and spatial distribution of population in Hangzhou’ (Yin et al. Citation2007).

References

- Aalborg University’s Spatial Data Library, , 2009. Calculations of the growth in urbanized land within Copenhagen Metropolitan Area, 1999–2008. Aalborg, Denmark: Aalborg University; 2009.

- Bjørnskau, T, and Hjorthol, RJ., 2003. Gentrifisering på norsk – urban livsstil eller praktisk organisering av hverdagslivet? (Gentrification in Norway – urban lifestyle or practical organisation of everyday life), Tidsskr Samfunnsforsk. 44 (2) (2003), pp. 169–201.

- Brindley, T, Rydin, Y, and Stoker, G., 1996. Remaking planning. The politics of urban change. London, UK: Routledge; 1996.

- Commission of the European Communities, , 1990. Green paper on the urban environment. Luxembourg, Germany: Office for the Official Publications of the European Communities; 1990.

- http://www.dac.dk/visKanonVaerk.asp?artikelID=2700 Last accessed 18Jun2011. , Danish Architecture Center. 2011. Arksitekanon [Internet]..

- Elmore, R., 1985. "Forward and backward mapping: reversible logic in the analysis of public policy". In: Hanf, K, and Thoonen, TAJ, eds. Policy implementation in federal and unitary systems: questions of analysis and design. Vol. 23. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Erasmus University (NATO Science Series D; 1985.

- Faludi, A, and van der Valk, A., 1994. Rule and order: Dutch planning doctrine in the 20th century. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Klüwer; 1994.

- Feng, J., 2002a. Analyses on mechanisms of the development of suburbanization in Hangzhou, Geogr Territorial Res. 18 (2) (2002a), pp. 88–92, (in Chinese).

- Feng, J., 2002b. Research on the industrial decentralization of Hangzhou city, Urban Planning Rev. 138 (2) (2002b), pp. 42–47, (in Chinese).

- Fingerplan, , 2007. Copenhagen, Denmark: Ministry of Environment; 2007.

- Hajer, MA., 1995. The politics of environmental discourse – ecological modernisation and the policy process. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1995.

- http://www.hzstats.gov.cn/web/ShowNews.aspx?id=sUqykY/7Lek=, Hangzhou Statistical Yearbook. 2008. [Internet]. [cited Spring 2009]..

- http://www.hzstats.gov.cn/web/ShowNews.aspx?id=K7TYu2b6ZN4=, Hangzhou Statistical Yearbook. 2009. [Internet]. [cited Spring 2010]..

- Hangzhou Urban Planning Bureau, , 2007. Hangzhou Master Plan. Authorized by the State Council of China in 2007. Hangzhou, China: Municipality of Hangzhou; 2007.

- Hjorthol, RJ, and Bjørnskau, T., 2005. Gentrification in Norway. Capital, culture and convenience, Eur Urban Reg Stud. 12 (4) (2005), pp. 353–371.

- Høyer, KG, and Næss, P., 2001. The ecological traces of growth, J Environ Policy Planning. 3 (3) (2001), pp. 177–192.

- 1996. Jenks, M, Burton, E, and Williams, K, eds. The compact city: a sustainable urban form?. London, UK: E & FN Spon; 1996.

- Mogridge, MJH., 1997. The self-defeating nature of urban road capacity policy. A review of theories, disputes and available evidence, Transp Policy. 4 (1) (1997), pp. 5–23.

- Mol, APJ, and Spaargaren, G., 1993. Environment, modernity and the risk society: the apocalyptic horizon of environmental reform, Int Sociol. 8 (4) (1993), pp. 431–459.

- Mol, PJ, and Sonnenfeld, DA., 2000. Ecological modernisation around the world: an introduction, Environ Politic. 9 (1) (2000), pp. 1–14.

- MOLAND Project, , 2010. Growth of area categories Copenhagen. Spreadsheet including figures for the extension of different land cover categories within Greater Copenhagen during the period 1954–1998, received through personal e-mail communication with Carlo Lavalle from the EC MOLAND project on 1 October 2010. Ispra, Italy: European Commission – Joint Research Centre, Institute for Environment & Sustainability; 2010.

- Næss, P., 2006. Urban structure matters: residential location, car dependence and travel behaviour. London, UK: Routledge; 2006.

- Næss, P., 2008. "Nyliberalisme i byplanlægningen". In: Lundkvist, A, ed. Dansk nyliberalisme. Copenhagen, Denmark: Frydenlund; 2008. pp. 231–264.

- Næss, P., 2009. Residential self-selection and appropriate control variables in land use–travel studies, Transp Rev. 29 (3) (2009), pp. 293–324.

- Næss, P., 2010. Residential location, travel and energy use: the case of Hangzhou Metropolitan Area, J Transp Land Use. 3 (3) (2010), pp. 27–59.

- Næss, P, and Høyer, KG, 2009. The emperor's green clothes: growth, decoupling and capitalism, Capitalism Nature Socialism. 20 (3) (2009), pp. 74–95.

- Næss, P, Mogridge, MHJ, and Sandberg, SL., 2001. Wider roads, more cars, Nat Resour Forum. 25 (2) (2001), pp. 147–155.

- Newman, PWG, and Kenworthy, JR., 1999. Sustainability and cities. Overcoming automobile dependence. Washington, DC: Island Press; 1999.

- Noland, RB, and Lem, LL., 2002. A review of the evidence for induced travel and changes in transportation and environmental policy in the US and the UK, Transportation Res D. 7 (1) (2002), pp. 1–26.

- Osland, O, and Longva, F., 2009. Presentation of a strategic institute program on coordination in transportation planning. Oslo, Norway. 2009.

- Qian, Z., 2007. Institutions and local growth coalitions in China's urban land reform: the case of Hangzhou High-Technology Zone, Asia Pac Viewp. 48 (2) (2007), pp. 219–233.

- Qian, Z., 2008. Empirical evidence from Hangzhou's urban land reform: evolution, structure, constraints and prospects, Habitat Int. 32 (4) (2008), pp. 494–511.

- Qiu, B., 2006. Compactness and diversity: the core idea of sustainable urban development in China, City Planning Rev. 30 (11) (2006), pp. 18–24, (in Chinese).

- http://www.regionh.dk/NR/rdonlyres/AA49BFCE-A544-4727-9C29-CE12D1C4B6FF/0/UdviklingidenkollektivetrafikiRegionHovedstaden.pdf Last accessed 05Jul2009. , Region Hovedstaden. 2009. Udvikling i den kollektive trafik i region Hovedstaden [Internet]. Hillerød (Denmark): Region Hovedstaden;.

- Sørensen, CH., 2001. Kan Trafikministeriet klare miljøet? Om integration af miljøhensyn i trafikpolitik og institutionelle potentialer og barrierer. Copenhagen, Denmark: Jurist-ogØkonomforbundetsForlag; 2001.

- Standing Advisory Committee on Trunk Road Assessment, , 1994. "Trunk roads and the generation of traffic". In: Standing Advisory Committee on Trunk Road Assessment. London, UK: UKDoT, HMSO; 1994.

- Statistics Denmark, , 2009. Population statistics BEF1A07, BEF44 and population statistics 1901–2008 displayed especially for this research project. Copenhagen, Denmark: Statistics Denmark; 2009.

- http://statbank.ssb.no/statistikkbanken/ Last accessed 08Dec2010. , Statistics Norway. 2009. Areal og befolkning i tettsteder [Spatial extension and population of urban settlements] [Internet]..

- Statistics Sweden, , 2002. Tätorter 2000 [Localities 2000]. Örebro, Sweden: Statistics Sweden. Statistiska meddelanden MI 38 SM 0101; 2002.

- Stead, D, and Marshall, S., 2001. The relationships between urban form and travel patterns: an international review and evaluation, Eur J Transp Infrastruct Res. 1 (2) (2001), pp. 113–141.

- Strand, A, and Moen, B., 2000. Lokal samordning – finnes den? Prosjektrapport 2000:18. Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research; 2000.

- Strand, A, Tennøy, A, Næss, P, and Steinsland, C., 2009. Gir bedre veger mindre klimagassutslipp?. Oslo, Norway: Institute of Transport Economics; 2009, TØI Rapport 1027/2009.

- Tao, T, Tan, Z, and He, X., 2007. Integrating environment into land-use planning through strategic environmental assessment in China: towards legal framework and operational procedures, Environ Impact Assess Rev. 27 (3) (2007), pp. 243–265.

- Transport Bureau of Hangzhou, , 2011. Passenger transport carried out on road in Hangzhou over the period 2000–2009. Hangzhou, China: Transport Bureau of Hangzhou; 2011.

- Verroen, EJ, Jong, MA, Korver, W, and Jansen, B., 1990. Mobility profiles of businesses and other bodies. Delft, The Netherlands: Institute of Spatial Organisation TNO; 1990, Rapport INRO-VVG 1990–03.

- Wang, W, Jin, J, Xiao, Z, and Shi, T., 2009. The characteristics of urban expansion and its driving forces analysis based on remote sensed data and GIS – a case of Hangzhou city from 1991 to 2008, Geographical Res. 28 (3) (2009), pp. 685–695, (in Chinese).

- [WCED] World Commission on Environment and Development, , 1987. Our common future. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1987.

- Wu, F, and Zhang, F, 2009. The development of spatial planning and city-region governance in China. Presented at Paper presented at: The 23rd congress of the Association of European Schools of Planning. Liverpool, UK, 15–18, Jul, 2009.

- Xie, Q, GhanbariParsa, AR, and Redding, B., 2002. The emergence of the urban land market in China: evolution, structure, constraints and perspectives, Urban Studies. 39 (8) (2002), pp. 1375–1398.

- Yin, W, Qian, M, Ye, N, Bai, Y, and Shen, X., 2007. Tendency of demographical change and spatial distribution of population in Hangzhou. Hangzhou, China: Zhejiang University; 2007, Report of Sustainable Development Research Center.

- Zegras, C., 2010. The built environment and motor vehicle ownership & use: evidence from Santiago de Chile, Urban Studies. 47 (8) (2010), pp. 1793–1817.