Abstract

Daily commuting is a significant cause of energy use in a new town. Available literature shows that there is a strong link between land use, socio-economic characteristics of people and travel demand. In this article, the parallel and interrelated influence of these factors on travel demand in a new town will be discussed. Land use in this research will be studied through main travel-generating uses (such as workplace, educational facility, shopping area and recreational facility) on local and regional scales and accessibility to main activity centres (such as neighbouring and distant towns and cities). Important socio-economic characteristics studied here are the number of wage earners, travel mode choice and travel behaviour in a household. The case study was done in Hashtgerd New Town, approximately 65 km west of Tehran on the route of the Tehran–Qazvin Freeway. Research tools used here are questionnaires, field trips and interviews. Statistical software (SPSS) was used for data entry and descriptive analysis. Based on 185 questionnaires from the New Town (each representative of one household) supported by interviews and reference to similar recent research, the results suggest that both land-use pattern and socio-economic characteristics influence travel demand. Land-use pattern was studied on small, middle-sized and large geographic scales. The study shows that on a middle to large scale, the location of the New Town in proximity to existing activity centres, which provide job opportunities for the inhabitants, would reduce the distances travelled daily for work. On a small to middle scale, a mixture of land uses to provide educational and shopping facilities will decrease the need for long-distance commuting. Among the socio-economic factors, car ownership rate, income and household composition and characteristics indicating the number of workers and students in a family could influence the distance travelled and mode of travel of each family member.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development is an integral part of planning in the twenty-first century. Consequently, new approaches such as “New Urbanism” and “Smart Urban Growth” have been developed, in which, by using design tools such as compact urban form and mixed use, attempts are made to reduce daily commuting and dependence on private cars, as well as achieving social and economic vitality in neighbourhoods (Jenks and Kozak Citation2008). One of the main reasons for focusing on environmental issues in urban planning is that cities are responsible for most pollution resulting from fossil fuel consumption in transportation and residential sectors, which play a significant role in climate change. The “Energy Balance” report of Iran shows that about 23% of CO2 emissions in 2008 were produced by the transportation sector and 26% by the residential and commercial sectors (Office of Electricity and Energy Planning Citation2010). Also, according to information published in the “Hydrocarbon Balance of the Country”, residential and commercial sectors are responsible for about 40% of the total consumption of hydrocarbons, followed by the transportation sector (Energy Management Department of International Energy Institute Citation2008). Furthermore, data show a rapid growth of energy use in Iran: according to “Iran's initial national communication to UNFCCC”, for the years 1987–1998, the average annual growth rate of petrol consumption was 6.4%. It should be noted that more than 98% of petrol in Iran is consumed by the transportation sector. One of the main reasons for this growth is the increase in private car ownership, which is also a consequence of more private transportation for inner-city trips in Iran (Department of Environment Citation2003).

Considering the prominent role of the energy sector in total CO2 emissions in Iran, it is necessary to develop new approaches in urban planning and design to optimize energy use in urban areas. This study is part of a research project entitled “Young Cities, Developing Energy-Efficient Urban Fabric in the Tehran-Karaj Region”, which is an Iranian–German research initiative in the framework of the research programme “Future Megacities” of the “German Federal Ministry for Education and Research” (BMBF). The project is led by the Technische Universität Berlin and the Building and Housing Research Centre of Iran, with the broad aim of developing, implementing and evaluating technologies, strategies and methodologies that allow realization of sustainable and energy-efficient housing settlements, explored within the case study on Hashtgerd New Town. This research, as a sub-project of Young Cities, has focused on land-use patterns that may affect travel demand and, consequently, can be attributed to energy use in a new town.

2. Literature review

The world population is now 7 billion, and more than 50% live in cities where both human activities and the use of energy are concentrated. Cities come in all shapes and sizes; the idea that these different shapes – whether sprawling or dense – can play a role in determining the environmental impacts of urban areas is gaining currency in both popular and scientific circles. Generally, there are two important ways in which spatial structure of cities and energy use are related:

| 1. | Travel and transportation requirements | ||||

| 2. | Energy used in buildings, mainly for space heating (Owens Citation1986) | ||||

Another important issue is the effect of landscape planning and layout of built-up areas on the amount of energy used in buildings. The case study in this research is a new town located near Tehran. Energy-efficient urban fabric in this new town can be developed with a focus on the above-mentioned factors. However, specifically it is preferable to focus on special attributes of energy use in a new town, which are critical and need more attention compared to those in existing cities.

According to Ziari and Gharakhanlou (Citation2009), “the construction of new towns around Tehran follows the objectives of absorbing the overflow population of Tehran city, preventing increase of real property price in Tehran and offering housing to low-income groups”. On this basis, four new towns, Hashtgerd, Andisheh, Pardis and Parand, were constructed on the periphery of metropolitan Tehran. The findings of some studies show that although the new towns located around Tehran are relatively successful in absorbing the overflow of Tehran's population, they are dormitory in nature and mostly depend on the main city for work and services (Zebardast and Jahan Shah Lou Citation2007; Ebrahimzadeh et al. Citation2009; Ziari and Gharakhanlou Citation2009). In this regard, daily commuting from home to work is a major issue in these new towns. In addition, as they are newly established settlements, it takes time to provide the necessary urban services (e.g. education and recreation). Thus, it seems that to access daily needs, a high number of trips between the new town and the mother town might be inevitable. Therefore, the predominant energy use in a new town, which distinguishes it from other settlements, is long daily trips to and from the central cities. By studying travel demand in a new town, planning strategies to reduce the energy used in daily commuting could also be developed.

The question remains: which attributes of urban form can affect the energy used in daily trips or, in other words, how does urban form affect travel demand in a city? Urban form is a term that has been developed to describe the physical composition of a city; urban design theoreticians have explained it through various factors according to different viewpoints, scales and objectives. Research on the relationship between urban form and travel demand has defined urban form mostly through the following characteristics: density of an urban area (inhabitants/ha), its mixture of land uses (divisions into residential, commercial, industrial, etc.) and its provision of transportation options (public transport facilities, communication networks, etc.) (Owens Citation1986; Kitamura et al. Citation1997; Van Wee Citation2002; Ferguson and Woods Citation2009; Pan et al. Citation2009; Zhao et al. Citation2009). A literature review also indicates that among different aspects of urban form, land-use pattern was frequently referred to as the most important factor influencing travel demand (Handy Citation1996; Boarnet and Sarmiento Citation1998; Boarnet and Crane Citation2001; Van Wee Citation2002; Holden and Norland Citation2005; Milakis et al. Citation2008; Pan et al. Citation2009). It should be noted, however, that the most recent research on land use and travel demand measured land-use characteristics for small geographic units, mostly neighbourhoods (Boarnet and Crane Citation2001). In newly developed settlements, due to insufficient urban services and fewer job opportunities, daily trips to and from other distant activity centres might be necessary. Thus, different levels of geographic unit, ranging from regional to local scale, should be tested in case studies. Naess (Citation2011) also indicated that “metropolitan-scale urban–structural variables generally exert a stronger influence than neighbourhood-scale built-environment characteristics on travelling distances by car during weekdays”. At the local (neighbourhood) level, the extent to which land uses are mixed and the layout of development may affect travel demand. At the regional level, the location of new developments in relation to existing towns, cities and other infrastructure may affect travel demand (Stead and Marshal Citation2001). Proximity of a residence to other cities or city centres can be more influential when there is concentration of various jobs and services (Naess Citation2011). This means that the more facilities (e.g. various job, shopping or education opportunities) available in a centre, the more the centre could be a potential travel destination for nearby or even distant residences.

Accessibility is another topic closely related to scale. According to Handy (Citation1993), to obtain clear insight into travel demand, accessibility should be measured on micro- (local) and macro- (regional) scales. She also found that “Local accessibility depends on close proximity to locally oriented centres of activity, whereas regional accessibility depends on good transportation links to large, regionally oriented concentrations of activity” (Handy Citation1993). In a new town, for example, accessibility on a local scale refers to convenient foot/bike access to daily needs such as grocery stores and schools, whereas on a regional scale, establishment of efficient public transportation systems to access activity centres such as workplaces, department stores and universities is essential. summarizes the important elements of geographic scale and accessibility that should be considered in land use–travel demand research for a new development.

Table 1. Land use/accessibility elements on local and regional scales

It is important to consider that the physical attributes of a city (such as land-use pattern) are not the only elements determining travel demand in a city. Research has shown that travel demand also depends on socio-economic characteristics of the inhabitants. While easy access to activity areas is very important to reduce daily trips, the social and economic situation of people (e.g. income and car ownership rate) is also crucial (Stead and Marshal Citation2001; Dieleman et al. Citation2002; Giuiliano and Narayan Citation2003; Zhang Citation2006). It is difficult to say which factors (land-use pattern or socio-economic characteristics) have more impact on travel demand, as there is a very complex relationship between these factors, which changes according to regional characteristics and even the research method used (Crane Citation2000; Stead and Marshal Citation2001). This article does not aim to provide a priority or ranking of the factors affecting travel demand; rather it will analyse their complex relationships and the possible use of sets of factors in developing design guides. Thus the main focus of this article will be the study of the relationship between land use, socio-economic characteristics and travel demand.

3. Research methods

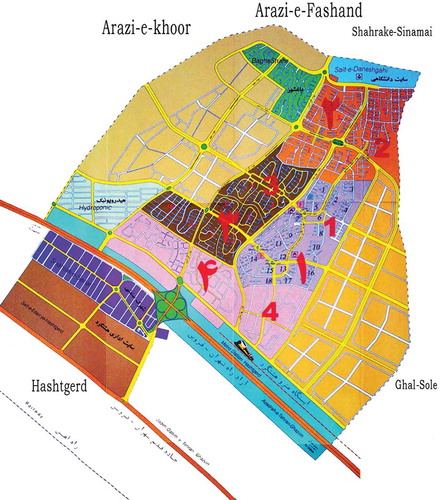

Hashtgerd New Town was chosen as a case study to show the relationship between land use, socio-economic characteristics of inhabitants and travel demand. The new town is composed of districts (or phases) that are in different stages of development and have different levels of access to urban services. According to an analysis by Paykadeh Consulting Engineers (PCE Citation2007), in 2006 when the new town had 15,736 inhabitants, the population in phase 1 was 10,068, in phase 2 was 4345 and in phase 3 was 1206, with the remaining people living in phase 4. The first three phases were the focus of this study to show how land use and socio-economic characteristics of inhabitants affect travel demand.

Land use in this research was studied in terms of main travel-generating uses (e.g. workplaces, educational facilities, shopping areas and recreational facilities) on local and regional scales and accessibility to main activity centres (e.g. neighbouring and distant towns and cities). Important socio-economic characteristics studied here were the number of wage earners, travel mode and choice and travel behaviour within a household.

Research tools used in the project, apart from a general review of related literature, were questionnaires, field trips and interviews to gather information from the new town. The interviewees were the current mayor of Hashtgerd New Town, heads of “Transportation” and “Urban Planning” departments in the Municipality of Hashtgerd New Town, the executive manager of the “Metro Organization of Hashtgerd New Town” and the former manager of “Hashtgerd New Town Development Corporation”. Statistical software (SPSSFootnote1) has been used for data entry and descriptive analysis of the questionnaire results, which were completed by 185 families in the New Town. In order to increase accuracy and ability to generalize, when possible, the results of descriptive analysis are compared with similar research done in Iran in recentyears.

4. Case study

4.1. General information

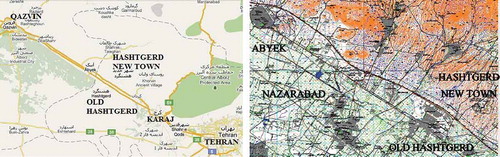

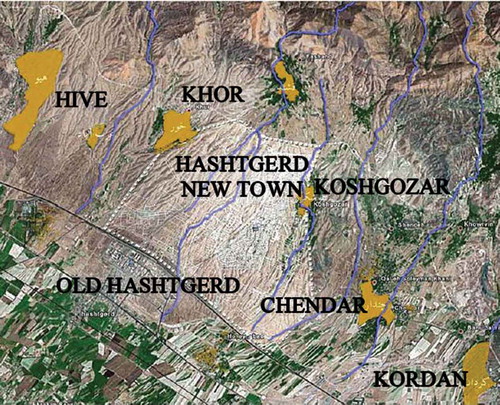

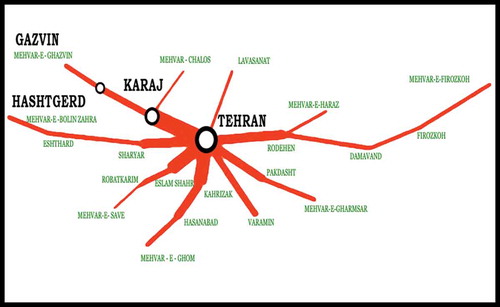

Hashtgerd New Town is approximately 30 km west of the emerging megacity of Karaj and 65 km west of Tehran on the route of the Tehran–Qazvin Freeway and on the foothills of Alborz Mountains (). Tehran–Karaj–Qazvin region is well known for its industrial and agricultural character. In addition to the geographic potential of this area, such as being in a vast plain of the south Alborz Mountains and access to water resources of the Karaj, Abhar and Taleghan Rivers, the three major and parallel routes of the Old Tehran–Karaj road, Tehran–Karaj–Qazvin Freeway and Tehran–Tabriz railroad increase the possibility to attract industrial and agricultural activities. The most important industrial zones in the region are Nazarabad Industrial Zone, Hashtgerd New Town Industrial Zone and Abyek and Alboroz Industrial Town (Pourahmad and Falahian Citation2005). Several villages with pleasant weather and beautiful scenery are located near the town and could be potential destinations for spending leisure time and even as tourist attractions ().

Figure 1. Geographic location of Hashtgerd New Town in relation to other towns and cities. (a) Regional scale (Source: http://maps.google.com). (b) Middle scale: location of other towns around Hashtgerd New Town. FootnoteNotes.

Figure 2. Middle scale: location of several villages around Hashtgerd New Town (PCE Citation2007).

Among the new towns located in Tehran metropolitan region, Hashtgerd is the most populated (Pakzad et al. Citation2007; Zebardast and Jahan Shah Lou Citation2007). The new town is about 4000 ha in area and is planned to accommodate a population of 500,000 over a 25-year period (Ziari and Gharakhanlou Citation2009). According to the latest official national census (in 2006), Hashtgerd New Town had a population of about 15,736 (PCE Citation2007). However, local data show that at the beginning of 2011 the population had risen to 35,520 inhabitants.Footnote2 The main objectives for the establishment of Hashtgerd New Town according to the Iranian New Towns Development Corporation (NTDC) are “to absorb surplus population of Tehran, to provide housing and occupation for the inhabitants, environmental preservation through prevention of horizontal growth of Tehran, and to prevent formation of slums and informal settlements around Tehran” (New Towns Development Corporation Citation2000).

4.2. Data collection and sampling

The fieldwork in this research commenced with the filling of questionnaires in Hashtgerd New Town. The first drafts of the questionnaire were designed according to the results of a literature review. Then, after discussion with Iranian researchers, it was adapted to local situations. During this process, the questions were reduced, simplified and clarified. The final questionnaire has two parts: part 1, questions about socio-economic characteristics, and part 2, questions about travel behaviour and its relationship to land-use pattern.

In the field study, which was done over several days in spring 2010, 315 questionnaires were distributed in Hashtgerd New Town, out of which 185 completed forms were received, which gives a total response rate of 58.7%. Sample size was calculated using the sampling formula for infinite population (Cochran Citation1963):

(1)

which is valid where n0 is the sample size, Z2 is the abscissa of the normal curve that cuts off an area at the tails, e is the desired level of precision, p is the estimated proportion of an attribute that is present in the population and q is (1 – p). The value for Z is found in statistical tables that contain the area under a normal curve.Footnote3 Therefore, if p = 0.5 (maximum variability) and confidence level is 95 ±7.2%, the resulting sample size is 185 families:

As the three residential phases of Hashtgerd are currently in different development stages, the questionnaires were distributed unevenly and in proportion to the existing population. Thus, out of the total of 185 questionnaires, 88 were filled in phase 1, 65 in phase 2 and 32 in phase 3 (). As the average family size in Hashtgerd new town was estimated as 4 persons (PCE Citation2007), these data could represent information on 740 persons, which, if the current population is 35,000 people, covers about 2.11% of the total population.

Figure 3. Small scale: different phases of Hashtgerd New Town. FootnoteNotes.

Figure 4. Hashtgerd New Town, phase 1. FootnoteNotes.

Figure 5. Hashtgerd New Town, phase 2. FootnoteNotes.

Figure 6. Hashtgerd New Town, phase 3. FootnoteNotes.

4.3. Descriptive analyses

4.3.1. Socio-economic characteristics

4.3.1.1. Demographic features

Descriptive analysis of the demographic features gathered through the questionnaires shows that Hashtgerd New Town has a relatively young population, which is of working age. The average ages of fathers and mothers are, respectively, 43 and 38 years. The average ages of the first, second, third and fourth children, respectively, are 17, 15, 17 and 16 years, which indicates that children are mostly of school age. Out of the sample population, 46.5% are women and 53.5% are men. This means that for every 100 women, there are 115 men (the sex ratio index is 115). This figure indicates that there is an imbalance in the distribution of men and women, which might be caused by the industrial nature of the area and ongoing construction work. The average family size is 3.91, which is comparable to current characteristics of urban areas in Iran: in 2006, the average family size was 3.98 in urban areas and 4.36 in rural areas (Statistical Center of Iran Citation2006). The demographic features are supported by other available data: according to the Iranian national census in 2006, the average family size in Hashtgerd New Town was 3.6 persons and the sex ratio index was 106.9. This index was 103.3 for Tehran, the same for Karaj and 104.0 for the whole country. Also sampling by PCE (Citation2007) shows that the average family size in Hashtgerd was 4.095 persons.

4.3.1.2. Education level

The data gathered from the questionnaires indicate that 83.2% of fathers and 91.2% of mothers have high school or lower education levels, and the number of parents with a university education is relatively low (). The average data for children also show that 92% have finished their high school education or are still students; about 8% have graduated from university or are university students.

4.3.1.3. Working–education characteristics

Data gathered from the questionnaires show considerable differences among married men and women. While about 90% of mothers are housewives, 84% of fathers are workers. Among these men, 45.3% are self-employed and 38.8% are employees; the remaining 16% are unemployed or retired. According to information on their education, they are not likely to have high-level jobs. The data also indicate that about 70% of children are currently students. By comparing these data with their average age and the education-level chart, most children are school students. This means that in each family, fathers and children are potential commuters, as they must go to work or school for at least 5 days a week.

The data extracted from the Comprehensive Plan of Hashtgerd show that 31.2% of the working population are employees of government organizations, 21.5% are private sector employees and 29% are self-employed (PCE Citation2007). Other research on the socio-economic function of Hashtgerd shows that out of the total working population, 5.1% are occupied in the agriculture sector, 13.4% in mining and industry, 10.2% in transportation, communication and financing, 20.7% in construction and 50.6% in service industries (Abrishamkar Citation2009). This further supports the idea that most inhabitants are ordinary workers or employees, while people with high-level jobs (e.g. managers and university lecturers) and university education rarely live in the new town. The data also indicate that although the city is in an industrial area, the role of industry in providing job opportunities is less than the service and construction sectors. A significant share of occupation in the construction sector is also the result of a considerable volume of housing construction activity in the new town.

4.3.1.4. Monthly outgoings

It is usually difficult to ask people about monthly income, as this is private information. As family income is a very important factor in this study, a number was deduced from monthly outgoings, which was a question more likely to be acceptable to the families. The data show that 84.5% of families have monthly outgoings of less than 7 million Iranian Rials (42.5% less than 5 million Rials and 42% between 5 and 7 million Rials), 11.9% between 7 and 10 million Rials and 3.9% with more than 10 million Rials. According to a survey by the Statistical Center of Iran in 2009, the average annual net expenditure of Iranian urban households was 99,191,000 Rials, a 5.3% rise from 2008 figures (Statistical Center of Iran Citation2009). From a simple calculation, the average monthly expenditure will be 8,265,916 Rials. Comparing this figure with the results of the current study, it can be concluded that more than 80% of households in Hashtgerd New Town spend less than the average urban household in the country. Due to inflation, this difference could be even higher, as found in the survey of the Statistical Center of Iran in 2009, but the questionnaires for the current research were completed in 2010. Studies in previous years in Hashtgerd New Town cannot be referenced as inflation rates make comparisons difficult. Nevertheless, it is important to note that such figures also indicate that income groups in Hashtgerd New Town are relatively homogenous and mostly consist of low- and middle-income groups (Jahan Shah Lou Citation2007; PCE Citation2007).

4.3.1.5. Vehicle/bicycle ownership

Vehicle ownership is a very important factor that affects the mobility of a family. This factor was assessed from two groups of data: number of ordinary private cars belonging to a family and number of “other” types of vehicle (van, truck, taxi, etc.). The data show that 44.5% of families have no private car (but might have “other” types of car), 51.7% have one car and 3.8% have two cars (55.5% have one or two vehicles). A complementary data analysis indicates that out of 44.5% of families who have no private car, 17.3% have one “other” type of vehicle. It can be concluded that 36.9% of families have no vehicle and 63.1% have some type of vehicle. The data show that the total number of private cars in the sample population is 108 (94 families have 1 car and 7 families have 2 cars). As the study covers 724 inhabitants, private car ownership rate for each 1000 persons in the new town would be 149. This is less than in Tehran, which in 2007 was 200 per 1000 persons (TCTTS Citation2007) and might have increased during the case study. The total number of other types of vehicle belonging to families was 18, as deduced from the total number of vehicles (private or other) per 1000 persons being 174. Other research on vehicle ownership rate gave similar results: data gathered for traffic planning in the Comprehensive Plan of Hashtgerd New Town show that 42% of families living in Hashtgerd have no private motor vehicle (PCE Citation2007); other research indicated that about half of families living in Hashtgerd have private vehicles (Jahan Shah Lou Citation2007).

A question about “car model” was included in the questionnaire. About 96.5% of cars belonging to families were models from Iranian car factories. This indicates that (1) as cars produced inside the country are relatively cheaper compared to imported ones, they are accessible to the low–middle-income group; and (2) as the quality of these cars is relatively lower than some imported cars (Economy World Citation2010), petrol consumption and air pollution might be higher.

The data also show that 37.7% of families have at least one bicycle: 29.5% have one, 6% have two and 2.2% have three bicycles. Although bicycles mostly belong to children and are usually used for entertainment, it shows the potential for encouraging the use of more environmental friendly vehicles in Hashtgerd.

4.3.2. Land use and travel behaviour

4.3.2.1. Scale and accessibility

To study the relationship between land use and travel demand on different scales, the main destinations for work, education, shopping and recreation should be identified. Descriptive analysis of socio-economic characteristics shows that in each family, the father and his children are most important travel-generating members, as fathers usually go to work and children are mostly of school age. Mothers might do the shopping, which also requires weekly (or even daily) trips. Considering the geographic location of Hashtgerd New Town in relation to the main towns and cities, potential travel destinations of family members are as below ( and ):

| 1. | Small (local) scale (city): Hashtgerd New Town | ||||

| 2. | Middle (regional) scale (district): Old Hashtgerd, Hashtgerd New Town and Old Hashtgerd, neighbouring towns and villages (Nazarabad, Abyek, Taleghan, etc.) | ||||

| 3. | Large (regional) scale (region): Tehran, Karaj and Qazvin | ||||

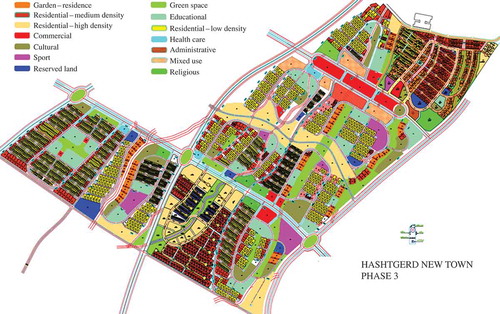

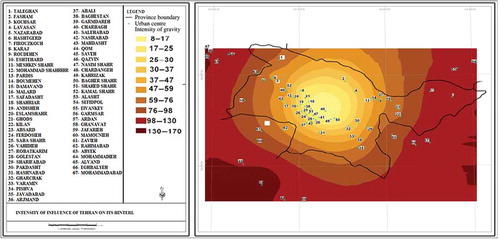

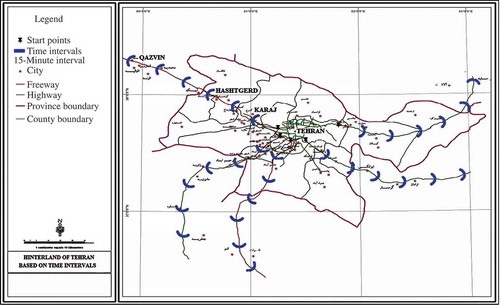

Large scale: Hashtgerd New Town is in the hinterland of Tehran. This means that Tehran as the political and economic centre of the country may affect this New Town. Tehran can provide various attractions for working, education, shopping and entertainment. However, the relatively large distance between Tehran and Hashtgerd New Town might reduce the intensity of this attraction and dependency. shows the intensity of influence of Tehran on its hinterland, where the intensity is directly affected by the distance between Tehran and its neighbouring cities, and is much higher for Karaj (No. 8 on the map) compared to Hashtgerd (No. 6) and even less for Qazvin (No. 46) (Rezaii and Vusat Citation2011).

Figure 8. Intensity of influence of Tehran on its hinterland (Rezaii and Vusat Citation2011). FootnoteNotes.

Middle scale: A further examination of the three categories of scale shows that the intermediate scale appears in the vicinity of Hashtgerd New Town. In this research, this is called middle scale, to distinguish it from the bigger scale, which shows connection to Karaj, Tehran and Qazvin. According to the latest national census in 2006, the main cities in this scale have the following populations: Old Hashtgerd 45,529; Nazarabad 97,722; and Abyek 47,487 inhabitants. These three cities are the capital of separate countiesFootnote4: Old Hashtgerd is the capital of Savojbolagh County, Nazarabad of Nazarabad County, both in the newly founded Alborz ProvinceFootnote5; and Abyek is the capital of Abyek County in Qazvin Province. Old Hashtgerd is the nearest city and supposed to have stronger socio-economic connection to the New Town ().

Small scale: illustrate land-use patterns and locations of neighbourhood centres. They show the mixed-use character of the master plan, which provides access to daily needs for each phase (neighbourhood) of Hashtgerd. However, due to the local topography and high slope of the land, it is not easy to walk around on foot; there are also no special bike paths available. Because of the phased development of the town, the current urban fabric is scattered and fragmented, and there are many empty areas of land in the neighbourhoods, which create a feeling of insecurity for pedestrians (Bahraini and Khosravi Citation2010).

Accessibility: Data on available public transport facilities were obtained from several interviews with responsible people in the municipality of Hashtgerd New Town. According to this information and complementary data from Hashtgerd Comprehensive Plan, the current public transport facilities are summarized in . The urban railroad (metro) connecting Tehran and Karaj is another access opportunity that will be extended towards Hashtgerd New Town in the near future. According to an interview (on 25 May 2011) with the executive manager of the metro of Hashtgerd New Town, up to now, 43% of the construction of the new extension is completed, and if problems such as funding and land acquisition conflicts are resolved, it will be finished by the end of 2012.

Table 2. Public transportation facilities in Hashtgerd New Town

In and , the traffic intensity and times of trips on the arteries connecting Tehran to its hinterland area are illustrated. The Tehran–Qazvin Freeway, especially the part that connects Tehran to Karaj, is one of the most crowded arteries in the region, leading to time-consuming and inefficient access between Hashtgerd, Karaj and Tehran (TCTTS Citation2007).

Figure 9. Traffic intensity on the arteries connecting Tehran to its hinterland (TCTTS Citation2007).

Figure 10. Hinterland of Tehran based on time intervals (Rezaii and Vusat Citation2011). FootnoteNotes.

4.3.2.2. Workplace

Hashtgerd New Town is located in an industrial area with good job opportunities. Apart from proximity to factories and workshops along the Tehran–Qazvin Freeway, there are also other job opportunities in the area in the offices and administrative bodies of the Old and New Towns of Hashtgerd (e.g. training and education organizations, energy and water supply offices, local universities, Hashtgerd New Town Development Corporation and municipality) and service sector (real estate agents, local shops, etc.). Ongoing construction activities provide other potential jobs for civil engineers, technicians and manual workers. The location of Hashtgerd New Town in Tehran metropolitan region also provides potential jobs. Karaj, with more than 1.7 million inhabitants, is another major centre that can also absorb potential workers.

The data on male workplace are summarized in , showing that the main destinations are large and distant cities, categorized as “large scale”, followed by cities at middle distances. Moreover, the percentage of people working in small- and middle-sized activity centres (48.6%) is higher than that for the large scale (35.6%). Similar results were found in other researches. Studies for preparation of the Comprehensive Plan of Hashtgerd New Town show that 28.4% of heads of households work in Hashtgerd New Town, 2.8% in Old Hashtgerd, 16% in Tehran, 7.9% in Karaj, 9.9% in neighbouring towns, 1.4% in activity centres along the Tehran–Karaj highway, with no information on the other 26.4% of workers (PCE Citation2007).

Table 3. Male workplace destinations

This study also indicates the importance of small- and middle-distance destinations for employment travel. It shows that there is good potential in the area to reduce dependency on regional work centres such as Karaj and Tehran, and through this there would be less need for long-distance daily trips for employment purposes. Location of the new town near existing activity centres and its connection to neighbouring towns and cities proved to be effective in this case. Poor adequate access to distant cities could be a further reason why people seek employment at small and middle distances, although due to the concentration of job opportunities, Tehran is still a major travel destination for work.

4.3.2.3. Education place

According to an interview and correspondence with the Urban Planning Department of the municipality of Hashtgerd New Town (on 2 May 2011), 15 education centres (i.e. schools) exist in the New Town. The comprehensive plan for Hashtgerd New Town also indicates that as the city is still in the development phase and has not yet absorbed its target population, the number and per capita area of educational facilities are more than current population needs (PCE Citation2007). Some universities have also established branches in Hashtgerd region. The Azad University has branches in Old Hashtgerd and Nazarabad cities, and Pyam-e-Nour University has a branch in Hashtgerd New Town. However, the best universities in the country are located in Tehran. The International University of Qazvin is also a well-known academic centre.

shows the education place of children living in Hashtgerd New Town. On average, 54.94% of children go to school (or university) in places located at small or middle distances from the new town. As previously mentioned, most children are of school age; however, the data do not discriminate between school and university students. Therefore, complementary data analysis has been done on samples limited to children of 18 and under, which indicates that 78.85% of school-age children were studying in the Old or New Town of Hashtgerd. Out of these (who are 18 years old or less), 66.57% go to school in Hashtgerd New Town. This means that Hashtgerd New Town is rather independent in providing school facilities for children and that there are few daily trips of middle and large distances for education purposes in this age group. Proper distribution and sufficient quantity of schools are also apparent in neighbourhood (phases) plans () and field observations. Mini-bus and taxi access is also provided for children who are studying far from their residences.

Table 4. Children's education places

4.3.2.4. Shopping areas

The report of the comprehensive plan of Hashtgerd New Town indicates that current shopping facilities are quantitatively sufficient for the inhabitants (PCE Citation2007). According to an interview and correspondence with the Urban Planning Department of the municipality of Hashtgerd New Town (2 May 2011), 678 commercial units are currently active in the New Town. Field survey shows that the majority of these shops are real estate agents offering property in the New Town. An interview-based qualitative research in 2009 shows that of those interviewed (60 residents from three phases of Hashtgerd New Town), 80% can reach shopping facilities on foot for their daily needs. This study also shows that for everything beyond daily requirements (e.g. clothing and shoes), the residents must drive to Old Hashtgerd, Karaj or Tehran (Schröder et al. Citation2011). gives the main shopping destinations of families living in Hashtgerd New Town, showing that Old and New Towns of Hashtgerd are the most important providers of daily shopping needs. As previously mentioned, in a typical family living in Hashtgerd, most mothers are housewives, implying that mothers do most of the daily shopping. According to , the major travel destination for mothers is at small and middle distances. show the mixed-use nature and distribution of daily local shopping centres. Old Hashtgerd, which has been the capital of Savojbolagh County since 1959, can provide a range of weekly and monthly needs for the inhabitants.

Table 5. Daily shopping destinations

4.3.2.5. Visits to/from relatives

While work, education and shopping are the most important travel-generating activities there are other, less frequent activities that involve travel. Weekly or monthly visits to/from relatives are a traditionally important activity for Iranian families. Since Hashtgerd is a newly established settlement, it is likely that its inhabitants are from other cities and their relatives would also live in those cities of origin. shows that for about 80% of the inhabitants, relatives are located in distant cities (Tehran, Karaj and Qazvin). Moreover, 20.6% of families have relatives living in cities other than Tehran, Karaj or Qazvin, while only about 3% have relatives in Qazvin. Similar research supports these results; PCE (Citation2007) showed that 38.1% of families living in Hashtgerd are originally from Tehran and 17.2% are from Karaj. Another research showed that 39.4% of families are from Tehran and 18.2% are from Karaj (Zebardast and Jahan Shah Lou Citation2007). Hence, a significant number of the current residents of Hashtgerd New Town have migrated from Tehran and Karaj, and while there is a strong social bond between the new town and those cities, the link to Qazvin is very weak.

Table 6. Visits to/from relatives

4.3.2.6. Leisure facilities

Another important travel-generating activity is how a family usually spends its leisure time. On a regional scale, both Tehran and Karaj can provide various entertainment facilities for the inhabitants of nearby cities. Hashtgerd New Town is close to some villages with pleasant weather and beautiful gardens that also provide opportunities for leisure (). Field visits and other research (Alighalebabakhani Citation2007; Schröder et al. Citation2011) show that there are some active parks, green spaces (Golestan Park in phase 1) and sports centres in Hashtgerd New Town, which are frequently used by the inhabitants. shows that near and distant cities are major destinations for leisure time, but that Hashtgerd New Town is the most important destination for this purpose. As previously mentioned, most inhabitants of the new town are from low–middle-income families, which can explain why they tend to spend holidays at home.

Table 7. Leisure facilities

4.3.2.7. Number of trips per week to the main cities

In another attempt to understand the dependency of Hashtgerd New Town on neighbouring cities, the families were questioned on the number of trips per week to the main cities. shows that, on average, men travel to Tehran 1.7 times per week, 1.1 times to Karaj, 3 times to Old Hashtgerd and 0.2 times to Qazvin. In a week, women travel 0.5 times to Tehran, 0.4 times to Karaj, 1.6 times to Old Hashtgerd and 0.03 times to Qazvin. Children travel once to Tehran, 0.4 times to Karaj, 1.5 times to Old Hashtgerd and 0.2 times to Qazvin. There is a strong relationship between Old and New Hashtgerd, and an important relationship between Hashtgerd New Town and the big cities of Tehran and Karaj. The table also shows that men travel more frequently to the distant cities of Tehran and Karaj, while all family members travel frequently to Old Hashtgerd but less to Qazvin. Here, the interaction of two factors of accessibility and concentration of activities can be seen: Tehran is the biggest centre for all activities (job, shopping, education, etc.) in the whole country, but is rather far with relatively poor access facilities. At the same time, Old Hashtgerd is a regional centre but is closer with better access. Although Old Hashtgerd cannot provide the variety of services available in Tehran, due to its proximity, it is considered the major destination for all family members. However, as shown previously, travel plays an important role here: when there is a need for more variety and concentration of activities (such as work trips), Tehran is still a major destination, while for daily shopping less variety is needed and both Old and New Hashtgerd are major destinations.

Table 8. Average number of weekly trips by family members to the main cities

4.3.3. Mode of travel

As previously mentioned, each family member in the sample undertook a range of activities. The type and location of these activities could affect their choice of travel mode. According to data from the questionnaires, means of travel used by family members can be divided into three groups: (1) “un-sustainable” – private car and motorcycle; (2) “semi-sustainable” – includes a combination of semi-public, public and private means where for daily activities, users sometimes travel by private car and sometimes by bus, and so on; and (3) “sustainable” – such as public transport, bicycles and walking. shows that men who work mostly use a car or motorcycle. For women, who are mostly housewives and go shopping, semi-private vehicles are used more frequently, although public transport is also important. For children who go to school, public transport is slightly more common than semi-private means. The table also shows that the most frequently used vehicle for men is private cars (45.2%), while women use taxis more than other options (34.2%) and children use taxis (28.26%), walk (25.52%) or use bicycles (3%). Complementary data show that 46.4% of children (first, second and third) of 18 or under go to school on foot or by bicycle, while among families who own at least one car, 71% of men go to work in private cars.

Table 9. Vehicles used by each family member for daily trips

It can be concluded that land uses for shopping and education are accessible with more sustainable methods of transport compared to those for workplaces, which are mostly accessible only using private means. Hence, shopping and educational facilities are not far from the living areas. The importance of taxis as a semi-public transportation means is also obvious, which shows the present inadequacy of public transport facilities.

5. Results and discussion

In this article, the influence of socio-economic characteristics of inhabitants and land-use pattern (as an urban element) were analysed simultaneously. The study shows that both factors influence travel demand and could consequently affect the amount of energy consumed in daily commuting. A review of the current literature shows that while considerable volume of research has been done on the relationship between land use and travel demand on a neighbourhood scale, little attention has been paid to the possibility that land-use characteristics might be better predictors of travel demand on larger scales. This study suggests a framework for further research on the link between land use and travel demand, with the focus on larger scales. In a new town like Hashtgerd, land use should be studied on various geographic scales, starting from the first decisions about town location: Hashtgerd New Town is located in an industrial–agricultural area that can potentially provide inhabitants with opportunities for work, education, shopping and leisure pursuits. Although, in general, it might be considered a satellite town that depends on Karaj and Tehran, the results show the possibilities for formation of a semi-independent urban area by developing stronger connections between Old and New Hashtgerd and other neighbouring towns, such as Nazarabad and Abyek.

The research again confirms that accessibility and distance from activity centre, together with concentration of activities, have important effects on travel demand. Although both Tehran and Karaj provide numerous job opportunities, problems associated with daily commuting, poor public transport facilities and traffic jams encourage inhabitants to work in nearby centres such as Hashtgerd Industrial Town and neighbouring cities. However, distance from activity centres is not the only factor determining job location: Hashtgerd New Town is located midway between Tehran and Qazvin, but the number of residents working in Tehran is considerably higher than those working in Qazvin. This shows the importance of the number of job opportunities in relation to work travel.

Concentration of activities had different effects depending on travel purpose. For example, Tehran is the major destination for work-related journeys, even though it is not easily accessible but provides more job opportunities. When variety and choice are of prime importance, accessibility and proximity will lose their importance. On the other hand, most trips for daily shopping are oriented towards the Old and New Towns of Hashtgerd. Here, variety does not play such an important role, and proximity is the dominant factor. Similarly, for daily trips to local schools, but for university students, variety and range of opportunities are more important than proximity.

The research also indicates that on small (local) scales, the mixture of land uses may affect travel behaviour. Most daily shopping and educational needs of families are fulfilled on small (and middle) scales. The land-use mix of the three phases shows an appropriate distribution, with acceptable distances to residential units. However, field observations indicate that due to the hilly topography and empty lots, inadequate pedestrian features (sidewalks, perceived safety) and lack of bike paths, the main land uses (shopping, education) are not always accessible on foot or by bicycle.

Demographic features together with socio-economic structure of households have important roles in the choice of travel mode (modal split) and distance travelled. The population of the new town is relatively young and active: fathers are mostly of working age and children of school age, but most mothers are housewives and do not work. These characteristics together with job, education and shopping facilities affect travel behaviour in ordinary families. Men work and usually travel longer distances, and as job opportunities are mostly at middle to long distances, they prefer private cars, if possible. Children go to school and mostly travel shorter distances as education facilities are available locally or close-by, so most use some type of public transport. Women must do the shopping and usually do not travel long distances and most use taxis or other types of public transport. The influence of household income on travel mode is especially apparent in car ownership rate and how leisure time is spent. If people own a car, they use it: most men who own a car go to work in it. Thus, use of public transport by men is generally related to a lower rate of car ownership in such families. Figures on leisure time also show limited mobility is mostly related to limited income.

Socio-economic data indicate that Hashtgerd has a relatively homogenous society: education and income levels of households show little variation, and a large percentage of women are housewives. It is rational to expect that this homogeneity will also affect travel behaviour. For example, there was little variation in the ways in which families usually spend their leisure time. A high percentage of women are housewives and have a lower level of mobility. Families with two wage earners usually own more cars and commute more. It is important to remember that the city is still in its development stage and will eventually accommodate a large number of people with possibly higher variations in their socio-economic characteristics. This means that in the near future Hashtgerd New Town will require qualitative and quantitative improvements to urban services, infrastructure and access networks. The results suggest that there must be greater reliance on potential small and middle geographic scales in order to meet future demographic needs. Otherwise, by concentrating on housing activities without improving urban infrastructure, the dependency of the new town on Tehran and Karaj will increase even further in the near future.

6. Suggested framework for further research

illustrates how the results of the current survey might serve as a framework for further research. The diagram has three major sections: “socio-economic characteristics”, “access” and “land-use layout”. In each section, important sub-factors highlighted as a result of the current study are introduced. For example, among socio-economic characteristics, income, number of wage earners and number of students are important. At the bottom of the diagram, a sub-section entitled “scales” is derived from (literature review) and modified according to the current results by adding an intermediate scale, the “middle scale”. This sub-section illustrates the gradual change from small to large scale, for both “access” and “land-use layout” sections. “Travel demand” stands in a separate box in the middle of the diagram and is affected by interactions among all other factors.

Another important item in is the introduction of two groups of physical and non-physical characteristics affecting travel demand. These two groups can only be separated by a dashed line, which defines a spectrum of gradual change, rather than into two strictly separated parts. Factors such as household characteristics are non-physical, while “scales” are physical and other factors are borderline, for example, “Modal split” and “trip destination” are two factors that are simultaneously related to both physical and non-physical attributes. For the “modal split”, the choice of travel mode relates to available transport systems and cost, as well as private facilities such as cars and motorcycles. “Trip destination” is determined by need, for example, work, shopping, education, on the one hand, and land-use layout on the other. As shows, even access and land-use layout, which seem to be purely physical in nature, have non-physical attributes. Access is related to car ownership rate, which is a socio-economic factor, and land-use layout is also a physical embodiment of actual need of residents.

According to the diagram, travel demand is affected by the interaction of three main factors: family/household structure, access and land-use layout. Here, special attention should be paid to the role of planning tools/systems for intervention in travel demand. On a regional (large and middle) scale the first step for development of a new town is site selection. To reduce daily commuting, it should be located in proximity to regional access roads and activity centres. A semi-independent area, with a mixture of different functions, may reduce dependency on long-distance trips. Nevertheless, there will always be demand for access to distant centres that provide more options for work, education, shopping and so on. Provision of a sustainable transport system, for example, urban railroad, is of prime importance, as existing access roads may be unable to fulfil mobility needs of new residents. Definition of target groups is another important task in preliminary phases of development. Consultation with social and economic experts will provide more information about characteristics of target groups and their potential travel behaviour. More variety in socio-economic structures leads to more variety in travel demand/behaviour, and that means provision of a wider range of transport options.

There is much research on how to optimize travel demand on small scales, but one of the aims of the present research was to emphasize the importance of geographic scale and its interactions with other factors. Each scale should be handled separately as well as considering its hierarchical relation to other scales.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) for funding this research and Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Elke Pahl-weber (Technical University of Berlin) for her sincere supervision. He also thanks Prof. Hossein Bahrainy, University of Tehran, for his valuable comments on this research.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mahta Mirmoghtadaee

Mahta Mirmoghtadaee: Building and Housing Research Center, Tehran, Iran; Institute of Urban and Regional Planning, Technical University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

Notes

Source: Iranian National Cartographic Center 2000.

Source: NTDC of Hashtgerd.

Source: NTDC of Hashtgerd, legend translation by the author.

Source: NTDC of Hashtgerd, legend translation by the author.

Source: NTDC of Hashtgerd, legend translation by the author.

Note: Legend translation by the author.

Note: Legend translation by the author.

1. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL.

2. Unpublished data from Hashtgerd New Town Development Corporation.

3. See http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pd006.

4. SHAHRESTAN.

5. Karaj used to be a county (SHAHRESTAN) in Tehran Province (OSTAN) with a capital city of the same name. In 2010, together with some neighbouring counties, it became a new province called Alborz, with the capital city of Karaj.

References

- Abrishamkar, P., 2009. Functional evaluation of Hashtgerd New Town with emphasis on its socio-economic objectives, Mohanes Moshaver. 44 (2009), pp. 43–51.

- Alighalebabakhani, M., 2007. Evaluation of urban spaces in Hashtgerd New Town, Shahrnegar. 48 (8) (2007), pp. 48–54.

- Bahraini, SH, and Khosravi, H., 2010. Physical and spatial features of built environment that have impact on walking, health status and body fitness, Honar-Ha-Ye-Ziba: Memary Va Shahrsazi. 2 (43) (2010), pp. 5–16.

- Boarnet, MG, and Crane, R., 2001. Travel by design, the influence of urban form on travel. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- Boarnet, MG, and Sh, Sarmiento, 1998. Can land-use policy really affect travel behaviour? A study of the link between non-work travel and land-use characteristics, Urban Stud. 35 (7) (1998), pp. 1155–1169.

- Cochran, WG., 1963. Sampling techniques. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1963.

- Crane, R., 2000. The influence of urban form on travel: an interpretive review, J Plan Lit. 15 (1) (2000), pp. 3–23.

- Department of Environment, , 2003. Iran's initial national communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC. Tehran, Iran: National Climate Change Office; 2003.

- Dieleman, FM, Dijst, M, and Burghouwt, G., 2002. Urban form and travel behaviour: micro-level household attributes and residential context, Urban Stud. 39 (3) (2002), pp. 507–527.

- Ebrahimzadeh, I, Gharakhanlou, M, and Shahriari, M., 2009. New Town of Pardis and its role in decentralization of Tehran metropolis, Geogr Dev. 7 (13) (2009), pp. 27–46.

- http://www.donya-e-eqtesad.com/Default_view.asp?@=234344 Last accessed 13Jun2011. , Economy World. 2010. The role of autos produced by Iranian factories in air pollution in the capital city [Internet]..

- Energy Management Department of International Energy Institute, , 2008. Hydrocarbon balance of the country, 2006. Tehran, Iran: International Institute for Energy Studies; 2008.

- Ferguson, N, and Woods, L., 2009. "Travel and mobility". In: Jenks, M, and Jones, C, eds. Dimensions of the sustainable city. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2009. pp. 53–74.

- Giuiliano, G, and Narayan, D., 2003. Another look at travel patterns and urban form: the US and Great Britain, Urban Stud. 40 (11) (2003), pp. 2295–2312.

- Handy, S., 1993. Regional versus local accessibility: implications for nonwork travel, Transp Res Rec. 1400 (1993), pp. 58–66.

- Handy, S., 1996. Understanding the link between urban form and nonwork travel behavior, J Plan Edu Res. 15 (3) (1996), pp. 183–198.

- Holden, E, and Norland, IT., 2005. Three challenges for the compact city as a sustainable urban form: household consumption of energy and transport in eight residential areas in the Greater Oslo region, Urban Stud. 42 (12) (2005), pp. 2145–2166.

- Jahan Shah Lou, L, 2007. A study on the socio-economic characteristics of families residing in Hashtgerd New Town, Jameeyat (Population). 15 (59–60) (2007), pp. 101–132.

- Jenks, M, and Kozak, D., 2008. "Polycentric and defragmentation: towards a more sustainable urban form?". In: Jenks, M, Kozak, D, and Takkanon, P, eds. World cities and urban form, fragmented, polycentric, sustainable?. London, UK: Routledge; 2008. pp. 71–92.

- Kitamura, R, Mokhtarian, PL, and Ladiet, L., 1997. A micro-analysis of land use and travel in five neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay area, Transportation. 24 (2) (1997), pp. 125–158.

- Milakis, D, Vlastos, T, and Barbopoulos, N., 2008. Relationships between urban form and travel behaviour in Athens, Greece. A comparison with Western European and North American results, Eur J Trans Infrastruct Res. 8 (3) (2008), pp. 201–215.

- Naess, P., 2011. New urbanism or metropolitan level centralization? A comparison of the influences of metropolitan level and neighborhood level urban form characteristics on travel behavior, J Trans Land Use. 4 (1) (2011), pp. 25–44.

- [NTDC] New Towns Development Corporation (Iranian New Towns Development Corporation), , 2000. A review on design and implementation of four new towns around Tehran (Hashtgerd, Pardis, Andisheh, Parand). Tehran, Iran: Ministry of Housing and Urban Development; 2000.

- Office of Electricity and Energy Planning, , 2010. Energy balance, 2008. Tehran, Iran: Ministry of Power, Vice Presidency of Electricity and Energy; 2010.

- Owens, S., 1986. Energy planning & urban form. London, UK: Pion; 1986.

- Pakzad, J, Hosseinzadeh Lotfi, F, and Jahan Shah Lou, L., 2007. Assessment of new town self-sufficiency based on working and non-working trips by mathematical models, Int J Contemp Math Sci. 2 (12) (2007), pp. 591–600.

- Pan, H, Shen, Q, and Zhang, M., 2009. Influence of urban form on travel behaviour in four neighbourhoods of Shanghai, Urban Stud. 46 (2) (2009), pp. 275–294.

- [PCE] Paykadeh Consulting Engineers, , 2007. Revision of Hashtgerd New Town comprehensive plan. Tehran, Iran: Iranian New Towns Development Corporation; 2007.

- Pourahmad, A, and Falahian, N., 2005. A survey on the formation of industrial corridors around Tehran, with the emphasis on Karaj-Qazvin corridor, Geogr Res. 37 (53) (2005), pp. 173–192.

- Rezaii, R, and Vusat, EO., 2011. Study of Tehran megalopolis hinterland using time and gravity models, Town County Plan. 2 (3) (2011), pp. 5–28.

- Schröder, S, Schmithals, J, and Poor-Rahim, N., 2011. Energy consumption behaviour and attitudes towards climate change in Hashtgerd New Town. Berlin, Germany: Nexus Institut für Kooperationsmanagement und interdisziplinäre forschung. Unpublished Report; 2011.

- Statistical Center of Iran, , 2006. The general results of Iranian national census of population and housing-1385. Vice Presidency of Planning and Strategic Supervision. Tehran, Iran: Statistical Center of Iran; 2006.

- http://www.amar.org.ir/Upload/Modules/Contents/asset0/english/summary_results-final_1388_2009_.docx.pdf, Statistical Center of Iran. 2009. Summary results of the urban and rural household income and expenditure survey-2009 [Internet]. [cited 2011 Nov 29]. Bureau of Population, Labour Force and Census..

- Stead, D, and Marshal, S., 2001. The relationships between urban form and travel patterns. An international review and evaluation, Eur J Trans Infrastruct Res. 1 (2) (2001), pp. 113–141.

- http://trafficstudy.tehran.ir/Default.aspx?tabid=18069&language=en-US Last accessed 13Jun2011. , [TCTTS] Tehran Comprehensive Transportation & Traffic Studies Co. 2007. Tehran comprehensive plan of transportation and traffic [Internet]..

- Transportation Office of the Municipality of Hashtgerd New Town, , 2011. Unpublished data gathered in an interview on 14/04/2011. (2011).

- Van Wee, B., 2002. Land use and transport: research and policy challenges, J Trans Geogr. 10 (4) (2002), pp. 259–271.

- Zebardast, A, and Jahan Shah Lou, L, 2007. A survey about Hashtgerd New City operation in surplus population attraction, Geogr Dev. 5 (10) (2007), pp. 5–22.

- Zhang, M., 2006. Travel choice with no alternative: can land use reduce automobile dependence?, J Plan Edu Res. 25 (3) (2006), pp. 311–326.

- Zhao, P, Roo, G, and Lu, B., 2009. Planning for low-carbon urban growth. Presented at Paper presented at: 45th ISOCARP Congress. Porto, Portugal, 18–22, Oct.

- Ziari, K, and Gharakhanlou, M., 2009. A study of Iranian new towns pre- and post revolution, Int J Environ Res. 3 (1) (2009), pp. 143–154.