ABSTRACT

This paper deliberates on the importance of two major themes, (a) emphasis shift from traditional urban planning approach currently practised in such cities as Tehran to a spatial metropolitan planning, and (b) giving due consideration to the role of knowledge on integrate metropolitan planning. In Tehran, the multiplicity of policy-makers involved in metropolitan planning portrays the unsolvable procedural problems of transfer of knowledge and its impact upon substantive aspects of planning. The purpose of this paper is to study the role of knowledge on integration in spatial metropolitan planning, presuming the necessity of integration in general and in Tehran as a case presented to exemplify the general ideas and challenges of knowledge-based policy integration. A qualitative content analysis was applied to achieve the purpose of this study. Application of the analytic aspect of the proposed framework disclosed the barriers of achieving a spatial integrated knowledge-based planning and policy-making in Tehran.

1. Introduction: problem under study and scheme of the paper

Enduring lack of coordination, collaboration and sharing of knowledge and information necessary for policy-making among policy-makers, and accordingly the production of problematic sectoral and uncoordinated decisions and policies, justifies the necessity for an integrated and spatial (i.e. multidimensional as against unidimensional) approaches of metropolitan planning and policy-making. Multiplicity of policy-areas and policy-makers involved in metropolitan planning and policy-making portrays the unsolvable problems of communication and transfer of information and knowledge, as policy-makers remain uninformed of the aims, agenda and policies of others. This strengthens the fact that there is no determination to share information and move towards policy integration. Such diverse aims and interests have perpetually produced challenging situations and barriers for policy integration. As a consequence of diverse and, in some instances, incompatible and conflicting aims, policies and deeds, and policy-making remain disintegrated, contradictory and unnecessarily conflicting, instead of progressing towards a coordinated and collaborative course.

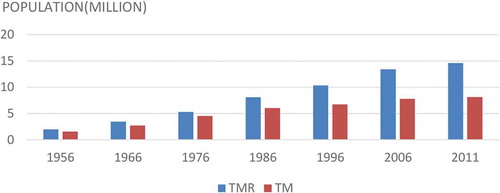

This paper argues that a major challenge in metropolitan policy-making process is the lack of accurate, transparent and integrated policies. This is due to the lack of an appropriate knowledge-based (KB) planning and knowledge-management framework. The purpose is studying the role of knowledge on integration in spatial metropolitan planning, presuming the necessity of integration in general and in Tehran as a case presented to exemplify the general ideas and challenges of KB policy integration. Furthermore, the different aspects and extent of integration in planning and policy-making processes are explained and analysed to denote a conceptual framework headed to conceive and devise an agenda to facilitate integration and knowledge sharing. This move requires putting an emphasis shift from traditional urban planning approaches, currently practised in Tehran, to the spatial metropolitan planning with due emphasis on the important role of knowledge management. Due to a varied combination of functional interdependencies of such metropolitan regions as Tehran, the urban and non-urban areas within its surrounding environment, the selected level of analysis of this paper is Tehran metropolitan region (TMR). This is an area that has no legal identity but for the purposes of this paper is considered as TMR, and if considered equal to Tehran province (TP), then it gains an official identity. Tehran metropolis (TM) is the capital of Iran with more than 10 million populations with its metropolitan region (comprising 12–14 million people, in 2015). This selection responds to the impossibility of disregarding the forces within its metropolitan region.

This paper presupposes that first a fitting integrated approach to spatial planning and policy-making through the application of KB policy-making can be formulated and applied accordingly, conditional to the political and administrative willpower of the metropolitan policy-making authorities, and second, integrated metropolitan planning and policy-making can be a process that can control vital resources to achieve more effective outcomes.

To achieve the aim of this paper, a dual descriptive-analytic and analytic-prescriptive methodology is devised (). The descriptive-analytic course starts with the review of worldwide experiences and definitions of key and applicable concepts related to the agenda of this paper. Through adopting appropriate measures grasped in the paper’s conceptual framework, the specifications of policy-making in Tehran in regards to integration–disintegration dichotomy and the presence–absence dichotomy of knowledge management assessed to achieve the goal of devising a model for facilitating integration through knowledge management, in the analytic-prescriptive schema.

2. Conceptual framework for KB integrated policy-making in metropolitan regions

The main areas of discussion are the conceptual and practical issues and problems concerning KB policy integration plus knowledge’s role on integration in spatial metropolitan planning.

2.1. Metropolitan region

Metropolitan regions are identified here as large concentrations of population and economic activity that constitute functional spaces based upon different demographic, service provisions and economic criteria, typically covering several local government authorities and representing the struggles for political power, cultural hegemony and economic dominance (OECD Citation2006; Ambruosi et al. Citation2010). Worldwide, metropolitan regions have two fundamental characteristics: possessing a high degree of economic integration while displaying a high degree of political fragmentation. The great majority of metropolitan regions combine the tension between integration and fragmentation with great social diversity (Diamond Citation1997).

2.2. Policy integration

According to social scientific concepts, integration – lack a universally fixed and widely agreed meaning – implies unity, balance, coherency, stability, order, consensus and absence of conflict and contradictions (Bornemann Citation2007). Bornemann (Citation2007) and Underdal (Citation1980) argue that integration is a form of aggregation to encounter and amalgamate the formerly dispersed parts, resulting in an increased perceptivity of the integral whole.

Shannon and Schmidt (Citation2002) define policy integration as an activity linking policy actors, organisations and networks across sector boundaries. Also, it is defined as a process concerning the management of cross-cutting issues in policy-making that transcends the boundaries of established policy fields to overcome both the fragmentation inherent in the sectoral management approach and the splits in jurisdiction among levels of government and between different municipalities (Hovik and Bjørn Stokke Citation2007; OECD Citation2009; Stead and Meijers Citation2009). The aim of policy integration has been defined as the removal of contradictions between and within policies, realising mutual benefits and making policies mutually supportive (Briassoulis Citation2004). According to Underdal (Citation1980), a policy is integrated where the constituent elements are brought together and made subject to a single, unifying conception. In addition, it ought to meet three basic requirements of ‘comprehensiveness’ (measured in relation to the fund of knowledge about policy consequences available at the decision time), ‘aggregation’ (recognising a broader scope of policy consequences and basing decisions on some aggregate assessment of such consequences) and ‘consistency’ (one in harmony with itself and with different accordant components). As shown in , this paper has made a distinction between different dimensions of policy integration.

Table 1. Policy-making and integration classification.

2.3. Policy integration for spatial metropolitan planning

Contemporary urban and metropolitan problems are spatial in that they are socio-economically and institutionally interrelated and complex, as they involve numerous, diverse and multifarious actors and resources interacting, through various formal and informal institutions, over and across different spatial and temporal levels (Briassoulis Citation2004, Citation2005). However, sectoral planning and policy-making activities concern each sector’s investment, actions and their future strategic plans, adopting a single, sectoral perspective that pays little consideration to the wider territorial impacts of other sectors’ goals, activities and policies.

Spatial planning primarily concerns the coordination of such sectoral policies and considers the integration among policy sectors according to different territorial units or administrative levels – local and regional – across a wide range of policy sectors addressing different economic, social and environmental issues and problems (Koresawa and Konvitz Citation2001). Koresawa and Konvitz (Citation2001) consider this coordination representative of a main strategic objective of spatial planning. The ‘comprehensive integrated approach’ as one main tradition of spatial planning, goes ‘beyond traditional land-use planning to bring together and integrate policies for the development and use of land with other policies and programmes’ (DCLG Citation2004, p.2).

Spatial integrated metropolitan planning and policy-making encounters the existence of varied and multiple policy areas and policy-makers (Bunker and Searle Citation2009). These are involved in the processes of metropolitan planning and policy-making each with varying and – on occasion – incompatible and conflicting aims and policies responding to their institutional goals and objectives (Kidd Citation2007; Nadin Citation2007; Stead and Meijers Citation2009; Buser and Farthing Citation2011). Thus, the policy system becomes unduly complicated; producing not only disorganised, unproductive and inefficient solutions but also generating new problems. This portrays the challenging issues of communication and sharing of information and knowledge, as the policy-makers remain unaware of the aims and policies of others. Such aims and policies become disintegrated, contradictory and unnecessarily competing instead of progressing towards an integrated, coordinated and collaborative course.

2.4. Knowledge and spatial metropolitan planning

Transition to knowledge era in the twenty-first century has led to the formation of a new relational and non-linear view of time, space and location (Wilson and Corey Citation2008). Knowledge management for spatial metropolitan planning can be conceptualised within such a framework that Healey (Citation2007) has referred to as relational approach of planning with multifaceted interactions and networks of relations. Highly complex new mix of urban and regional influences manifests the value of perceiving and socially constructing these new development dynamics through KB lenses that reflect a world that increasingly behaves non-linearly and operates across and within blended and overlapping functional boundaries (Hall and Pain Citation2006), multidimensional, multifunctional and temporal relationships. Considering these varied relations can inform spatial planning in an age of discontinuity, assuming that existing trends will continue into the future, Drucker (Citation1992) identifies four usual drivers of discontinuity, recounting knowledge as one (the four being: new technologies, globalisation, cultural pluralism and knowledge capital) (Yigitcanlar and Velibeyoglu Citation2008). Drucker (Citation1992) also claims on the pivotal role of knowledge and as the only sustainable source of competitive advantage and it is under the influence of neo-liberal policies that strategic spatial planning has widely been accepted as a critical instrument to cope with those discontinuities. According to Whitehead (Citation2003), in the knowledge era, spatial strategic planning attempts have to be KB, and KB strategic planning, therefore, is a key to economic, social and spatial development of city regions that choose to integrate highly mobile and networked KB economy (Ibid). Knowledge management for spatial metropolitan planning at the conceptual level concentrates on the role of knowledge-related factors as sources of development. The multilevel and multiplied nature of the knowledge needed in planning requires the production and transformation of an integrated and multifaceted spatial knowledge plus planning support systems capable of improving the handling of knowledge and information in planning processes to encounter the ever-increasing complexity of planning tasks (Vonk and Geertman Citation2008). The urge for the inclusion of KB management within the public sector policy-making arenas is more compelling, especially due to the contradictory and uncoordinated culture and procedures of public organisational structures (Lailhonen and Lonnqvist Citation2013).

2.5. Linking ‘knowledge management’ and ‘integrated spatial planning and policy-making’

A definition of knowledge, directly related to this paper, describes knowledge as ‘applied information’ that actively guides problem-solving and decision-making (Liebowitz and Beckman Citation1998). Viewed from varying facets, knowledge can have different aspects of (a) explicit knowledge that can be represented, stored, shared and effectively applied (Nonaka Citation1994); (b) tacit knowledge, which is often ignored in urban policy-making and planning processes and (c) community knowledge (Pfeffer et al. Citation2010). Knowledge management as a set of procedures, infrastructures, technical and managerial tools is a designed process towards creating, sharing and leveraging information and knowledge within and around organisations (Bounfour Citation2002). Knowledge management, especially in the scope of this paper, promotes and contributes immensely to ‘integration’ through vertical and horizontal collaboration and communication, changes the fragmented diverse processes and improves the productivity and efficiency of applications of ‘problem-solving’, ‘learning procedures’, ‘strategic planning’, ‘spatial planning’ and ‘policy-making’ processes.

There are varying, though in some instances contradictory, viewpoints about the linkage of knowledge management and KB planning and policy-making. First is that planning uses knowledge to increase its perception of the object under planning, while the result of such understanding is a greater ability to achieve society’s objectives (Harris Citation1987); and second is that planning refers to those activities which lead to the production of information that is produced and then analysed to support decisions (Hopkins and Schaeffer Citation1985). Thus, planning indicates a range of activities that both requires and results in the production of knowledge. The problem is to convert ‘knowledge’ into a material to apply in ‘planning and policy-making’. It is important to note that the role of knowledge management is to differentiate between the above-mentioned types of knowledge and to prepare to affect policy-making (Rubenstein-Montano Citation2000). An inference about linking the two is that information and knowledge plays a central role in planning (Nijkamp and Rietveld Citation1989). While knowledge is defined as information that has been organised and transformed into something understandable and applicable to problem-solving and policy-making (Liebowitz and Beckman Citation1998), this paper asserts that the emphasis on formal information is insufficient for launching an effective urban knowledge-base within the framework of comprehensive and integrated approach to spatial planning.

Planning and policy-making problems due to the spatial and political nature of planning do not fit into the traditional information systems This fact shifts the emphasis and application of information systems and ‘knowledge management’ in urban planning from a mere technical to a broader context suitable for the rationale of an integrated spatial planning. Knowledge management facilitates redefinition of problems as warranted by learning (Rubenstein-Montano Citation2000) because planning problems require flexible and adaptive systems to ensure adequate support for planning problems (Nijkamp and Rietveld Citation1989). As knowledge management is linked with strategic objectives in the public sector, a linkage between different aspects and facets of urban planning and knowledge management can improve the planning outcomes (Rubenstein-Montano Citation2000). An alternative approach to the traditional approaches to planning is one that focuses on knowledge management as both the source and outcome of a strategic planning approach, besides due attention to the planning environment, learning processes, inclusion of tacit knowledge and linking planning problem with planning goals and objectives (Akhter Citation2003; Rubenstein-Montano Citation2000). Linking knowledge management and integrated policy-making is to fit in a process of knowledge management, which consists of four processes of knowledge capture and creation, knowledge organisation and retention, knowledge dissemination and knowledge utilisation (Otim Citation2006; Apurva and Singh Citation2011). This is while a major challenge in metropolitan planning and policy-making is the presence of uncertainties. One of the tripartite areas of uncertainty as defined by Friend and Hickling (Citation2005) is uncertainty about the environment or about the information needed to make policies when the policy-maker is in intense need of more complete, available and integrated information. This indicates the need of policy-makers to more coordinated organisational agendas, aims and policies. Challenges presented by these uncertainties plus inhibiters of integration, mainly due to tensions between ‘functional integration’ and ‘political fragmentation’ (fragmented authorities bringing forward fragmented policies), indicate the fact that policy-making requires an increased tendency on the part of public authorities to share urban knowledge. This is accompanied by the assortment of policy-makers to establish such KB systems that facilitates and assists the founding of an integrated metropolitan planning and policy-making system.

3. Comparative examination of metropolitan planning in Seoul and Tokyo

To examine varying aspects of metropolitan planning, two metropolitan regions of Seoul and Tokyo are selected for studying in terms of their approaches towards both concentration and fragmentation of decision-making. Additionally, their manner of encountering the principles of this paper (Section 2) makes them more comparable to Tehran than many Western European or North American cases. Their sizes (both metropolises with more than 10 and contained by regions of more than 20 million people in 2016 that reside a high proportion of the total population of the country) and their expanding trends since the 1970s owing to country’s economic boom that transformed them into world’s global cities make them significant studied cases.

Seoul Metropolitan City the capital of South Korea is part of a metropolitan region in which the decision-making power is delegated to a two-tier system of subnational governments: regional governments and local governments. The functions of each unit of local government are twofold (Kim Citation2004): (a) intermediation between the national government and local governments, and (b) governance at local level. Local government is the provider of public services delegated to local governments (Local Autonomy Act of South Korea 1949 in Park Citation2006). Despite constitutional autonomy, Korean local government is not autonomous enough for its collective decision-making (Park Citation2006). The presence of special local administrative agencies that is not subject to local electoral control and works parallels to that of local government, greatly narrow the responsibilities and undermine local autonomy. Seoul Metropolitan Government, financially almost independent, is placed under the jurisdiction of the prime minister and the mayor that dominates local politics (Park Citation2000). Mayor and local council share budgeting, legislation of ordinances and other policy-making functions (Park Citation2000). Government of each metropolitan division has a multifunctional structure with a constitutional degree of local autonomy.

The metropolitan government of Tokyo Metropolis, combines elements of a city and a higher-level authority (Tokyo Metropolitan Government [TMG]) while the local government system of Japan has a three-tiered structure of national, regional and municipalities’ authorities. TMG, with Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly, are formal legislative and decision-making bodies that have the authority to enact, amend and repeal metropolitan ordinances, approve the budget and elect members of the Election Administration Commission and other such bodies. The Executive organisation implements the decisions made by the assembly through a locally elected governor that has overall control of metropolitan affairs. The metropolitan government has administrative responsibilities for services on a regional basis, while the wards have the autonomy to handle routine local affairs. Local governments play an extensive role, especially through high scale of expenditure by local governments and high amount of local total tax collected (CitationThe Structure of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG) 2006–2018).

To conclude, the main features of local/metropolitan governance in Seoul and Tokyo are as follows:

(a) Well-organised local governance though the structure of local governance remains fragmented and dispersed.

(b) Delegation of decision-making power to local levels, though local government’s decisions are subject to a degree of central control.

(c) Local financial independence.

(d) Allocation of local tax revenue to provide extensive welfare services at local/metropolitan level.

(e) Viable local politics especially through local elections.

(f) A territorially hierarchical manner of policy-making.

(g) Not enough empowered civil society actors.

4. Tracking the history of research on the relations of integrated policy-making and knowledge management in Tehran and TMR

There are few studies concerning the application of knowledge management to urban and metropolitan policy processes in Iran and Tehran. Although some have stressed upon the necessity of a mechanism for knowledge management, they have not paid sufficient attention to conferring upon such a framework. These studies can have a threefold classification. The first deals with identifying the challenges of fragmented policy-making in TMR in order to analyse the barriers and opportunities open to establish an appropriate mechanism, with no direct reference to the role of knowledge management in integrated policy-making (Asadie Citation2016a; Asadie Citation2016b; Akhundi et al. Citation2007, Citation2008; Asgari and Kazemian Citation2006; Barakpur and Asadie Citation2008; Sarrafi and Nejati Citation2015). The second group, in addition to the content of the first set of studies, refers to the role of knowledge management in integrated policy-making. The three studies under this category emphasise the

(a) Problem of disintegration of decision-making processes in Tehran and concerning TMR and propose an integrated management system (Institute of Economics of Tarbiat Modares University Citation2001).

(b) Role of knowledge management in integrated policy-making and the need for the production of continued flow of information to support decision-making (Institute of Economics of Tarbiat Modarres University Citation2001).

(c) Realisation of the problem of disintegrated decision and policy-making in Tehran as a severe problem of its management system, and proposing a dynamic regional planning system with an agenda to plan, implement, monitor and review the plan (IMSC Citation2006).

The third group of studies has

(a) Implicitly attended to the role of knowledge management, to information and communication infrastructures as the factors affecting integrated policies, attempted to improve the existing policy-making processes in Tehran (Kazemian and Mirabedini Citation2011), though no reference to the information and knowledge requirements of Tehran.

(b) Referred to the KB interaction of decision-makers and the need to establish an appropriate mechanism for knowledge management, though with no detailed proposals (Motawef Citation2010).

(c) Referred to the importance of applying knowledge management, tacit knowledge and its using and sharing amongst actors involved in decision-making processes. In addition, it has emphasised the importance of organisational aspects of knowledge management and the importance of applying knowledge management in the TM as an independent organisation but has neglected in considering the multiplicity of stakeholders involved in policy-making in Tehran and their respective roles nor has a tangible proposal (Hussaini Citation2011).

Performing the content analysis in this part of the paper of these researches and planning documents revealed the following conclusions:

(a) Institutions involved in policy-making in Tehran do not utilise and apply the concept of knowledge management in the production and consumption processes of policy-documents that need official ratifications (by bodies as the High Council of Architecture and Urban Development, government ministries and Commission of article 5 in Tehran Municipality [Tehran Municipality]).

(b) Sectoral policies and attempts in respect to knowledge management with due emphasis on information technology in TM (such as setting-up spatial databases and establishment of Tehran Observatory) to compensate the data deficiencies can be mainly defined as sparse attempts of gathering urban information in different time periods. These are attempts that are not only unrelated to the information requirements of the existing planning and policy-making system but also distant from the information requirements of a spatial planning and KB approach. In the absence of such an integrated framework and process, the prerequisites of reusing knowledge and learning from past experiences for the benefit of launching an integrated policy-making system and mechanism in the TMR have not been provided.

(c) Research into knowledge management and its relevance to integrated policy-making in Tehran is infrequent. This is in spite of the fact that these limited researches provide an initial basis for an integrated policy framework in Tehran; they have not explicitly elaborated on appropriate mechanisms.

(d) There are several unrelated plans prepared from 1989 onwards for TM (i.e. the Comprehensive Plan for TM [CPTM], detailed plans for the 22 urban districts of TM). In addition, a well-devised hierarchy of plan-making efforts makes both TM and TMR deprived of enjoying an opportunity to reuse knowledge and preceding experiences in its processes of policy-making.

All these indicate the fragmentation of research, plan-making activities and the ambiguity of the purpose of such studies and how and who is to conclude and integrate such temporally and administratively fragmented attempts.

5. General characteristic of TMR

TM, nucleus of TMR, is the centre of national government and all major countrywide political and socio-economic activities of the country. The processes of change in Iran as a whole have not been totally related to the economic competition associated with globalisation, transition to post-industrial society and the rise of the new information technology per se (Daneshpour Citation2007). This metropolitan region suffers from problems such as social, economic and spatial inequalities, unbalanced settlement system, unsuitable quality of life, degradation of the natural environment, weak and disintegrated planning mechanisms and dominance of property developers’ intentions and activities over the predetermined (whether correct or incorrect) public decisions (Daneshpour Citation2007). During the pre- and post-1979 era, the trend in its development has been towards the continuing mixture of primarily unplanned and randomly planned growth, mainly involving the development of new towns and road networks (Daneshpour Citation2007). Socioeconomic inequality, as a target for public policy-making and public sector intervention, has never been an agenda for urban decision-making and neither much of what done in the name of planning, in Iran and Tehran, has been of limited value in addressing sustainable development (Daneshpour Citation2007, Citation2011).

Below are the demographic, economic and physical characteristics and the political and organisational transformations in the course of the policy production processes in TMR.

5.1. Quantitative aspects of TMR

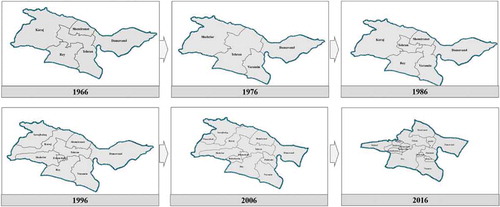

The functional region of Tehran was affected by an array of centralised forces in varying territorial scales during the period mid-1950s onwards: supra-national, national regional and local. Added to the gradual expansion of the city of Tehran and its increased spatial connections to the neighbouring settlements, through the increased population and the sphere of functional influence, TMR was formed. The population growth during the said period are shown in , and the spatial changes in TM and TMR in . The selection of this period is mostly due to the availability of data in official databases.

The spatial growth pattern of TMR, evolved during the said period, is concisely presented as follows (Daneshpour and Tarantash Citation2017):

(a) During the 1970s, with the accumulation of population in the main cities, a spiralling growth around nucleus of TM can be traced.

(b) During the 1980s, a leapfrogging expansion in the southeast and southwestern parts of the metropolitan region occurred. A small and incremental but extensive growth of a single-function land use (prevailing residential function) in which the developers (public or private sector) skip over land to obtain land at a lower price further out despite the existence of utilities and other infrastructure that could serve the bypassed parcels (Heim Citation2001; Yue Citation2013) can be traced.

(c) During the 1990s, the growth pattern was strip (or ribbon), in the Western parts of TM along extensive industrial complexes. A growth pattern taking place along extensive industrial or commercial developments that occur in a linear pattern along both sides of major arterial roadways (Holcombe Citation1999) can be traced.

(d) During the 2000s, strip or ribbon pattern of growth in the southwestern parts of TM accentuating and affecting the pre-existing growth trends of the smaller towns within TMR can be traced.

(e) Since 2010, the spiralling growth around nucleus of the towns and cities formed during the 1990s and 2000s and the strip development to the eastern parts of TMR is a dominant growth pattern.

The political and administrative boundaries within TMR during the said period were constantly changing, as shown in . During this period, TMR lacked an appropriate governance structure. The decisions and policies in this metropolitan region follow the multilevel and multi-sectoral decision-making trends of national government. These multiplied organisational structures comprise ():

(a) At national level, the ministries; the Parliament and other high power authorities.

(b) At regional level, the provincial offices of TP and its neighbouring Alborz province, plus all sectoral administrative offices that represent the national ministries.

(c) At subregional level, the 22 sectoral offices within the 2 related provinces.

(d) At the local level, the municipalities and urban councils of 59 cities (including TM and Karadj city).

(e) At sub-local level, the 100 offices and councils.

Table 2. Changing political and administrative structure, TMR (1956–2011).

This is while the existing authorities vary in their level, political power and institutional structure and thus TMR has a fragmented network of relations that has been without required powerful machinery and not strengthened by decision-support systems to manage beyond day-to-day administration of the entire metropolitan region as an integrated totality. This metropolitan region historically not only has a territorially dispersed political and institutional structure but also has lacked the ability to establish a definite, univocal and integrated planning mechanism to encounter the complex situation shaped under an amorphous metropolitan region.

The economic system of TMR, as part of countrywide macro-economic system, is a disintegrated and dichotomised system within which the large cities are the foci of the formation of formal activities, opportunities to attract skilled and semi-skilled and specialist labour force. In contrast TM’s peri-urban environment is based upon exogenous and mainly informal economic activities in a way that the formal and semi-formal are related to larger cities (TM and Karadj city) and informal activities to the smaller ones. Such a dual system has differentiated the nucleus and the peri-urban settlements. The manner of the growth of TM and its surrounding environment has a twofold shortcoming: first, the intensity of an overall growth to the economic growth that is able to offer fitting employment opportunities for the growing population of the region has not been proportional. Second, under-provision of social welfare services and facilities to respond to the growing needs of the population. This shortcoming not only has intensified the spatial inequalities within TMR but also has depleted the inner-urban areas of TM of the higher income groups and has replaced non-residential with residential land uses, widened the gap between the centre and periphery and has led the peri-urban environment of TM into deeper deprivation.

5.2. Process of policy production in TMR

The planning approach adopted in TM (and also in TMR) can be classified under the traditional approach of ‘synoptic planning’, associated with the technical expertise valued in the reconstruction period following World War II and adopted mainly in the more developed countries, especially Britain. The policy-making aura in Tehran is isolated from the sectoral policy-making processes of varying actors as shown in . This is a diffused urban policy-making system, which intensely and vividly inhibits not only integration and collaboration; but also the adoption of a radically improved approach of metropolitan planning and policy-making.

Production of information and policy-making process in Tehran can be considered as a relatively loosely connected continuum of information production, information consumption and policy production unrelated to the planning and policy-making processes ().

Concentration of mixed national and local decision-making and political organisations and activities in TM has exacerbated the state of collaboration among actors and has created disintegrated and in some cases conflicting aims, policies and decisions in various levels and contexts. The major problem areas and the disintegrated state of policy-making are defined, analysed and concisely listed below:

5.2.1. First problem area

Lack of vertical coordination among national and local policies and policy-makers: TM as the capital and prime city of the country is open to a multiplicity of public and private sector policies and policy-makers. This city is prone to national and even international policies. These policies affect those issues, problems and values that are in accord with the assumed role for TM. This is while the structural demands of TM inherently require policy-making specifically responding to the inner needs, requirements and constraints of its residents. In the absence of an official and holistic mechanism for planning and policy-making in TM and TMR to deal with such problems, contradictions and gaps, the outcome has been the creation of a problematic situation. The decisions of the council of TM (the sole elected body) are employed with the approval of the two upper tier bodies (i.e. Tehran Provincial Government and its sublevels) that follow the national level decisions and policies. Thus, the actors at metropolitan level have no legal role in metropolitan policy-making. The reason for inconsistency among the national, regional and local authorities relates to the lack of explicit and transparent power relations and tentative governance accountabilities related to policies affecting this metropolitan region. This is contrary and dissimilar from the division of duties and devolution of power to local level of government, the hierarchical policy-making processes and local autonomy (financial and political) as indicated above about the two cases of Seoul and Tokyo. According to the Parliament-ratified 5-year national socio-economic development plans of Iran (2004–2008, 2009–2013, 2014–2018), duties were assigned to the government to convey some responsibilities to the local levels of administration (including municipalities and urban councils). This ratification has not led to radical changes in the effective dispensation of local power in the country and in this metropolitan region and the policy formation for the local level at the local level. All this has provided a situation in which there are not only inconsistencies of agendas, duties and actions between the varying territorial levels but also competitive and conflicting policy-areas. There is a lack of appropriate legislative framework besides an effectual decision support system to ascertain the share and role of the different stakeholders in the decision-making and policy-making scene of TMR. This has caused the unaligned, dispersed and unrestrained groups who either have power or have access to sources of power to extract as much political power and economic benefits as can be of Tehran and have posed themselves in a determinant position. Considering two examples of Seoul and Tokyo in planning and managing metropolitan regions, the lesson learned is that an essential pillar of authority in policy-making and effective implementation of policies is local financial autonomy based on sustainable sources such as local taxation, virtually independent of the central government. The main sourcing of local income, as the central government stopped financing the municipalities, was TM’s resort to selling density according to directives approved by Tehran City Commission of article 5 that endorsed selling the density and altering the use of urban spaces to speculators by the TM. Thus since 1985, and then 1997, this has been TM’s routine to finance its highway development projects. The manner in which the revenues and local tax is centralised and in return the central government allocates ‘Government Aids’ to TM (a manner repeated throughout the country) is an indication of a lacking independent governance system. Altogether, there is no responsive authority to citizens towards the policies and plans prepared for TM.

5.2.2. Second problem area

Lack of horizontal coordination among major decisions and policies: TMR has turned into a sprawling and widespread metropolis and has expanded immensely: physically, environmentally, socially and economically, an outcome of which has been the multiplicity of policy-makers at all sectors that at such widespread landscape requires appropriate and well-developed mechanisms to reach and adopt an inter-connected policy arrangement. The arising inconsistency is due to a lacking of a policy framework that is a ‘common and committed covenant’ for all the producers of decisions, policies and plans for TMR reflective of the explicit and implicit agreements of all stakeholders. Considering the fact that the decisions inherent in the processes of making plans are exposed to be manipulated by political and economic power structures, the planning rules and regulations can be easily turn into commodities that can be bought and sold, and as a result of uncoordinated and confliction manners, varied common resources are wasted (Ebrahimnia and Daneshpour, Citation2017).

5.2.3. Third problem area

Weakness of the adopted planning approach: The theoretical aspects of planning, both in TM and TMR, are inactive and lend little to the role and functioning of planning and policy-making at national and local levels. This fact emphasises a well-reasoned selection and adoption of a transparent and integrated planning approach with a continuous, adaptive and spatial process. This requires due consideration to the fact that planning is a KB and adaptable and continued process and not one solely concerned with the preparation of end-state physically orientated plans. In addition, even the planning documents of TM and TMR are not referred to because the absence of obligatory reporting and responsive mechanisms of the public sector to the people has brought about a situation in which each policy-maker behaves according not to the ratified planning and policy-making documents but to their individuality and self-esteem. This has led to a situation that disarrayed policies, instead of achieving common goals and solving people’s problems, are orientated towards individual and group benefits.

5.2.4. Forth problem area

Inconsistent political behaviour and urban planning and policy-making: this discrepancy in both TM and TMR is specifically due to the eclectic planning approach adopted in practice. This approach is devoid of any logical and sensible thinking of the specific political features and power structures at national and local levels of governance; it lacks sound linkages to both political and statutory spheres of planning and policy-making.

6. Devised framework for analysing KB policy integration

To analyse KB policy integration in TM and TMR, this paper advises an analytical framework based on wide-reaching theoretical and conceptual studies reviewed, described and analysed above. This framework combines both the ‘policy integration’ measures and measures related to KB spatial planning system. To devise measures for assessing whether the planning and policy-making process in TMR is a KB process, a search based on the rationale presented in is done to follow the existence of the four main processes of (a) generation of knowledge, (b) retention of knowledge, (c) sharing of knowledge and (d) use or reuse of knowledge.

Table 3. Linking two domains of ‘integrated policy-making’ and ‘KB management approach’, devised and applied in TMR.

7. Applying the devised framework to analyse the KB policy integration in TMR

The method of applying policy integration–disintegration dichotomy based on urban knowledge-management framework in TMR in this paper uses the combined measures of integrated KB policy-making (as shown in ). For this purpose, the content of the existing policy documents and plans of TM and TMR, affecting spatial structure, functional processes and relations among policy actors was analysed qualitatively. In addition, the content of the expert interviews with the producers of such plans was analysed. The reviewed plans are at the

(a) functional relations field amongst TM and its suburban settlements: TMR plan (2002).

(b) TM: CPTM (2007).

(c) Urban district level, the 22 district plans of TM (2012), documents supporting these plans [including the documents related to workshops (Workshop of analysis of the Comprehensive Plan for Tehran (CPTM) Citation2006)] to assess the CPTM.

The analysis of documents was done regarding three important aspects of qualitative content analysis, i.e. (a) investigating the explicit contents of the documents, (b) investigating the implicit contents of the documents and (c) investigating what were not discussed directly in the documents but were assumed by the underlying research of this paper to be as indispensable. The results of this analysis against each of the criteria related to the requirements of KB management (shown in ) are as follows:

Table 4. Results of content analysis of plans for TMR against threefold fields and sets of assessment measures.

(a) Tracing the criteria ‘existence of knowledge-base to trace the impact of past decisions on future decisions’: The plan for TMR was the first plan at metropolitan level for Tehran, meaning that up to 2002, there was no document to base decisions concerning the whole region. During the process of CPTM preparation, and the sessions held with academic experts, the necessity of considering the impact of past decisions upon future decisions to produce strategies to be included in this plan was conveyed. In practice due to disaccord amongst the planners about the gravity of such necessity, its financial implications and problems related to its demanding technical knowledge, this appeal was undermined (Mansouri Citation2014). However, the monitoring and reviewing of the plan indicated changes according to the results of not the previous decisions but the immediate and individual policy-makers’ aspirations and decisions. The detailed plans for 22 urban districts of TMR were prepared ahead of the CPTM. Thus, there was no strategic plan to give strategic guidance to the detailed plans to act as operational plans. During this period, the ‘Permanent institution for studying and preparing urban development plans for TM’, as a reviewing body, dissolved (as established in 2008), and as a result, the statutory duty to review the plan for 11 years was disregarded.

(b) Tracing the criteria ‘feeding knowledge-base through daily operations of generated data to improve the knowledge-base’: a tripartite knowledge-base in Tehran was identified as follows: first, the raw data required for plan production are prepared and disseminated by ‘Statistical Centre of Iran’ (SCI), sectoral sources in the public sector, government departments and through field surveys of private sector planning consultants. There are no framework and mechanism for knowledge management and integration of mainly sectoral data. The SCI has no link to other data-producing and -processing institutions in the country or in Tehran. Second, the data collection during the processes of plan-making is only traceable in such documents and there is no integrated knowledge management system to accumulate these data and avoid the according wastage of resources. The data produced during the processes of plan-making by the private sector planning consultants work independently from other data producing and processing bodies. An important point disregarded in both TM and TMR planning processes is that they both require specific knowledge-base and an institutional structure designed and established for such purpose, but in the absence of such an innovative knowledge-management system, the SCI, according to its mission and agenda, is unable to respond to such grave venture. Another deficiency is negligence in updating data in spite of the 5-year census data collection by this centre. Third, the ignorance, concerning data production during the post-plan preparation period in each of the plans, examined by the research underlying this paper. Accordingly, the relevant decision-makers ignored the services and databases available for processing and analysing data. As a result, the data are considered as static, which is against any consideration regarding the dynamism of the systems under planning. For the purposes regarding the preparation of the CPTM, in addition to setting up a GIS system (i.e. TGIS: Tehran GIS), an international planning consultancy (i.e. APUR: Atelier Parisien d’Urbanisme) was invited to fulfil such purposes as exchanging experiences of modelling, updating and processing data, and managing GIS. This was limited to land-use changing structure, and ultimately, not only the existing data were not updated and was not based on sharing but also no attempt was made to establish a purposeful knowledge-base.

(c) Tracing the criteria ‘existence of data structures applicable for all policy-making and implementing actors’: SCI as the official data producing body of the country, produces data for all levels of aggregation while urban, metropolitan and regional plans require data at the functional levels that do not match the politico-administrative boundaries. This deficiency is intensified, considering the fact that data-producing bodies act uncoordinatedly and each produces data according to their agenda and level of aggregation. Thus, the inference is that at the level of analysis to respond to the requirements of a plan at regional level for Tehran, a main challenge is the lack of data and not recognising this level and the impossibility of integrating data due to the existence of disaccord amongst all the involved actors at such level of planning. In the process of planning for Tehran, the consultant declared the need to establish an organisation to deal with the task of data production for the specific level of TMR, a plea overlooked by the relevant authorities up to 2018.

(d) Tracing the criteria ‘existence of data exchanging mechanism to cover all levels of governance’: Plan for the Tehran urban region (TUR) proposed setting up an institution for the management of the area under this document’s study (referred to as urban agglomeration) to work as a mediating mechanism to exchange knowledge. In addition, it was to solve the disintegration problem of the involved authorities in decision-making for the defined area. Nevertheless, up to the date, the basic research of this paper was being prepared; no effort has been done in terms of establishing such a mechanism. In the process of preparing the CPTM, workshops were established to assess the plan for TM, to exchange ideas and to transfer information amongst the main public sector stakeholders and the academia. In the ‘Law of the Fourth Plan of Economic, Social and Cultural Development of the Islamic Republic of Iran’ (PBO Citation2004), preparation of appropriate context for integration amongst all involved in decision-making processes for Tehran (inter alia) was included as a major principle (CPTM Citation2006). However, collaboration among the Municipality of Tehran (MT) and all other stakeholders was considered an essential element in the implementation of plans, though with no operational guidelines. MT ‘Locational Database’ and ‘Spatial Data Infrastructure’ are under construction to respond to the mentioned statutory appeals and the aim of enhancing inter-organisational communication. Whatever access to and updating data, no preliminaries for data analysis and converting data to information have been deliberated. This deficiency can be related to the fact that the TM’s viewpoints are based upon information technology as against knowledge management and considering knowledge as input to decision-making processes, problem finding and problem-solving processes as there exists no mechanism for the transfer of such knowledge.

(e) Tracing the criteria ‘use of policy-makers of a common knowledge-base’: In the urban and regional planning system of Tehran and the three plans studied for the purposes of this paper, it became more obvious that there exists no authority responsible for establishing a common knowledge-base. Setting-up a permanent body for planning was foreseen as part of the proposals of the CPTM. This was to embody a joint knowledge-base as part of the agenda of this plan. This permanent body was formed and had a short life-cycle and was soon dissolved.

This is while a TURP’s (Tehran urban region plan Citation2002) proposal was setting-up a centre for statistics, information and planning with the purpose of continual data collection, data processing and report preparation. This proposal never materialised.

(f) Tracing the criteria ‘introduction of measures to evaluate the plans and implementation processes against goals, objectives and strategies in the formed knowledge-base’: In none of the three plans studied for this paper, neither alternative scenarios were prepared nor the measures to evaluate the alternatives and the implementation processes. Thus, it is deduced by Shokuhi et al. (Citation2012) that it is only in the CPTM that proposals concerning methods and measures to assess the achievement of goals and implementation of strategies are included without being used in evaluation processes.

(g) Tracing the criteria ‘existence of inclusive knowledge-base of public and private sectors’: In the PUAT, the methodology of plan-making was based on explicit knowledge (Workshop of analysis of the Comprehensive Plan for Tehran (CPTM) Citation2006), but in the CPTM by using an interview of 2200 residents of Tehran, and setting-up workshops with academia, it used local knowledge, too. This is an indication of applying implicit knowledge in the planning process. However, this innovation is a step ahead but there remain ambiguities of the ways and means of its usage in the PUAT, CPTM and the detailed plans for 22 urban districts of TM plans.

(h) Tracing the criteria ‘attending to the learning capacities for developing cooperation networks’: in the PUAT, no case regarding the confirmation of applying processes of public participation or collaboration is traceable. In CPTM in spite of proposing the ‘application of information transferring websites and pre-surveys about the view of academic experts about the content of the plan’, implementation of this proposal was never materialised. It was during the post-preparation and post-ratification period that the TM shared plan documents to the public. The output of the workshops had no impact on the substantive or procedural aspects (Workshop of analysis of the Comprehensive Plan for Tehran (CPTM) Citation2006). In spite of using questionnaire method of survey to collect subjective data, the detailed plans were not orientated towards either problem finding or applying public participation and collaborative mechanisms.

(i) Tracing the criteria ‘include the inputs and outputs of policy-making in the knowledge-base’: This criterion depends on the existence of a monitoring and review system that turns their results into a tool to guide the decisions. A not implemented PUAT makes it impossible to trace its outputs. The CPTM proposed a monitoring mechanism to be set-up to trace the impact of the decisions included in the plan (such as land-use zoning, increasing the urban densities, increasing population capacities and decreasing public services production) on the spatial structure of TM. This task as was bestowed to the ‘permanent institution’ disappeared with the dissolution of this body. But, in spite of a monitoring and review, no mechanism was devised to turn the output of the monitoring into a knowledge-base required for decision-making.

Through defining the pillars of knowledge management based upon its conceptual aspects as previously mentioned in this paper, the state of consideration and application of knowledge-management principles in Tehran as traced and analysed through distinguishing four fields of knowledge-management process as against the two substantive and procedural aspects of planning and policy-making, are elaborated as represented in .

Table 5. Analysing the pillars of knowledge management and its process in TMR.

8. Concluding remarks

In this paper, the importance of emphasis shift from traditional urban planning approach currently practised in Tehran to the spatial planning, and then the importance of considering the role of knowledge management in setting-up an integrated planning and policy-making system was discussed. The imperfect nature of planning and policy-making structure and multiplicity of policy-makers indicate the complexity of the policy-making and policy-implementation processes that has immensely hindered publicising and applying the concept of integration in Tehran. Based on the definition of the concept of integration in spatial metropolitan planning besides the specification of two types of dichotomies, i.e. the assessment measures for analysing integration–disintegration and the presence–absence of knowledge management, in this paper, a methodological framework to trace the indications of knowledge-base in the policy-making system of cases as Tehran is proposed. These are cases in which policy-making system historically have not enjoyed the research, planning and policy-making traditions in relation to knowledge management, spatial thinking and integration. Application of the analytic aspect of this framework disclosed the shortcomings and barriers of achieving an integrated KB policy-making system in Tehran.

Based on analysing the nature and function of policy-making system of Tehran against KB features, and the comparative study of planning and policy-making in Seoul and Tokyo, it is possible to improve the model of applying knowledge management for metropolitan regions such as Tehran in three major levels.

This requires a critically and deep-rooted cultural and administrative will and venture for improving the overall planning system. The three levels are as follows:

(a) Level one: This level is concerned with the collective agreement of all policy-makers (formal and informal) and at different levels (national, regional and local) on the necessity of establishing a policy-making structure at metropolitan region level to undergo tracks to fill the statutory gaps that inhibit action. At this level, ignorance or less attention to the interaction between public and private sectors of policy-making or ignoring the variety of stakeholders (including the society at large) and their interests, and their different ideological and behavioural frameworks that accordingly have different manners of identifying planning problems and solutions has led to a problematic situation. In this situation, the piecemeal attitudes and effects of the decisions and actions of such actors have undermined and inhibited any effort headed for integration and advancement towards a more suited and updated approaches and methods of planning and managing metropolitan regions. This indicates a fundamental doubt concerning the political propensity within the public policy-making environment to the devolution of decision-making power to the local level. This doubt is justified by referring to the historical authoritarian tendencies and disbelief in depending on people (especially financially, as the main source of national revenues has been the oil exporting revenues, as against taxation). To be financially independent from the central government is a major precondition for establishing a steady system of policy-making at metropolitan and metropolitan region level.

(b) Level two: In this level, model for the application of knowledge management in integrated policy-making depends on the acceptance of a continual process of planning to provide for the financial, organisational and other requirements to implement the plans and policies and be monitored and reviewed in specific periods of time. In such a structure, the official and unofficial actors have accountability towards the public and their representatives in the councils in terms of resources spent, and goals achieved through the implementation processes.

(c) Level three: In this level, the model for the application of knowledge management in policy-making is regarded as a foundation for integrated policy-making in TMR, and similar cases. This works as an integrated planning support system to coordinate planning and policy-making efforts within a knowledge-management framework.

To overcome the problematic situation traced by this paper, there is a need to bring changes in two major areas of metropolitan planning and policy-making. First is changing the context and substantive aspects of planning and policy-making by the adoption of an integrated and spatial approach to metropolitan planning supported by the relevant procedural aspects such as institutional and legislative mechanisms. The second change concerns establishing a KB planning and policy-making process to provide the appropriate decision support systems.

The significance of the findings of this paper lies in linking the two concepts of knowledge management and integrated policy-making into the concept of KB planning and policy-making in a metropolitan region such as Tehran, with no precedence of such studies and endeavours. Through developing an integrated KB system for policy-making in such metropolitan regions as Tehran, this paper aimed at attempting to minimise the impacts of replicated and parallel efforts and depletion of resources. The tangible application of integrated and KB spatial planning and policy-making model presented here can be emerged when an adequate KB system is considered as necessary by the relevant authorities, then devised, implemented and managed in such cases as TMR.

Geolocation information

Latitude: 35.785965435°47ʹ9.48″N

Longitude: 51.485924751°29ʹ9.33″E

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zohreh A. Daneshpour

Zohreh A. Daneshpour is a Professor Emeritus, Urban & Regional Planning, Shahid Beheshti University (SBU), Tehran, Iran. She got her PhD from “Urban and Regional Planning Department”, Liverpool University, G. B., in 1983 and is a member of EURA. She has supervised a number of PhD thesis of SBU. Her research is concentrated upon the theoretical and methodological plus practical aspects of urban and metropolitan planning.

Asrin Mahmoudpour

Asrin Mahmoudpour is an assistant professor of Urban Planning at University of Art, Tehran, Iran. She got her PhD (2015) and Master (2009) from Shahid-Beheshti University (SBU), working on “public spaces planning” and “knowledge-based urban development planning” during her Master and PhD of Urban and Regional Planning. Her current research focuses are knowledge-based urban planning, smart sustainable cites and urban management.

Vahide Ebrahimnia

Vahide Ebrahimnia is an assistant professor of Urban and Regional Planning at Shahid Beheshti University (SBU). She has worked on ‘application of collaborative approach in urban planning’ and ‘integrated policy making’ during her Master and PhD in Urban and Regional Planning. Her current research focuses on urban policy-making and policy evaluation, metropolitan governance, and sustainable cities.

References

- Akhter SH. 2003. Strategic planning, hyper-competition, and knowledge management. Bus Horiz. 46(1):19–24.

- Akhundi A, Barakpur N, Asadie I, Taherkhani H, Basirat M. 2008. The perspective of the Tehran urban-region governance system. Honar Ha Ye Ziba. 33(1):15–26. Persian.

- Akhundi A, Barakpur N, Taherkhani H, Asadie I, Basirat M. 2007. Tehran city-region governance: challenges and trends. Honar Ha Ye Ziba. 29:5–16. Persian.

- Ambruosi CS, Baldinelli GM, Cappuccini E, Migliardi F. 2010. Metropolitan governance: which policies for globalizing cities. Transit Study Rev. 17(2):320–331.

- Apurva A, Singh MD. 2011. Understanding knowledge management: a literature review. Int J Eng Sci Technol. 3(2):927–939.

- Asadie I. 2016a. Explaining the rationality of metropolitan regionalism in Tehran [ dissertation]. Tehran: Tehran University. Persian.

- Asadie I. 2016b. Why does Tehran metropolitan region (TMR) need a specific regional governance? Honar-Ha-Ye-Ziba. 21(1):5–16. Persian.

- Asgari A, Kazemian G. 2006. Descibtion and analysis of the system of currant urban conurbations in Iran. Urban Manag Q. 18:6–21. Persian.

- Brakpur N, Asadie I. 2008. Theories of urban management and governance. Tehran: Art University. Report No.: 12/32122. Persian.

- Berger G, Steurer R. 2009. Horizontal policy integration and sustainable development: conceptual remarks and governance examples. Vienna: ESDN Quarterly Report. June.

- Bornemann B. 2007. Sustainable development and policy integration – some conceptual clarifications. Paper presented at: Marie Curie summer school on earth system governance; May 28–Jun 6; Amsterdam (Netherland).

- Bounfour A. 2002. The management of intangibles: the organisation’s most valuable assets. London and New York: Routledge.

- Briassoulis H. 2004. Policy integration for complex policy problems: what, why and how. In: Greening of policies: inter-linkages and policy integration. Proceedings of 2004 Berlin Conference on the Human Dimensions of Global Environment Change; Dec 3–4; Berlin (Germany).

- Briassoulis H. 2005. Complex environmental problems and the quest for policy integration. In: Briassoulis H, editor. Policy integration for complex environmental problems. Aldershot: Asggate; p. 1–48.

- Bunker R, Searle G. 2009. Theory and practice in metropolitan strategy: situating recent Australian planning. Urban Policy Res. 27(2):101–116.

- Buser M, Farthing S. 2011. Spatial planning as an integrative mechanism: a study of sub-regional planning in south Hampshire, England. Plann Pract Res. 26(3):307–324.

- Comprehensive Plan for Tehran (CPTM). 2006. [ICSPA] [Iran’s Supreme Council for Planning and Architecture]. Tehran: Tehran Urban Research and Planning Center.

- Cowell R, Martin S. 2003. The joy of joining up: modes of integrating the local government modernization agenda. Environ Plann C. 21(2):159–179.

- Daneshpour ZA. 2007. Spatial inequality and dislocation in Tehran’s urban region. In: Klausen JE, Swianiewicz P, editors. Cities in city regions- governing the diversity. European Urban Research Association Conference, Warsaw, Poland. Warsaw: University of Warsaw.

- Daneshpour ZA. 2011. Considering the quality of life and sustainability in the metropolitan landscapes. Paper presented at: EURA 2011. Proceeding of Cities without limits, International Conference of the European Urban Research Association (EURA); Jun 23–25; Copenhagen (Denmark).

- Daneshpour ZA, Tarantash M. 2017. Analysing the impact of unplanned metropolitan growth on the peripheral natural environment: special reference to the metropolitan region of Tehran. Baghe Nazar j. 13(43):41–62.

- [DCLG] Department for Communities and Local Government. 2004. Planning policy statement 11: regional spatial strategies. London: Communities Local Government Publications.

- Diamond DR. 1997. Metropolitan governance: its contemporary transformation. Jerusalem: Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies.

- Drucker PF. 1992. The age of discontinuity: guidelines to our changing society. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers.

- Ebrahimnia V, Daneshpour ZA. 2017. Policy-making in Tehran: exploring the dichotomy of integration-disintegration. Honar Ha Ye Ziba. 21(1):15–28. Persian.

- Friend J, Hickling A. 2005. Planning under pressure: the strategic choice approach. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Hall P, Pain K. 2006. The polycentric metropolis- learning from mega-city regions in Europe. London: Earthscan.

- Harris B. 1987. Information is not enough. URISA News 90. p. 4–6.

- Heim CE. 2001. Leapfrogging, urban sprawl, and growth management: Phoenix, 1950–2000. Am J Econ Sociol. 60(1):245–283.

- Healey P. 2007. Urban complexity and spatial strategies: towards a relational planning for our times. London and NY: Routledge.

- Holcombe R 1999. Urban sprawl: pro and con. Bozeman (MT): [PERC] Property and Environment Research Center; [accessed 2018 Aug 14]. https://www.perc.org/1999/02/10/urban-sprawl-pro-and-con/.

- Hopkins LD, Schaeffer PV. 1985. The logic of planning behaviour. Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Illinois. Planning paper. Jul.

- Hovik S, Bjørn Stokke K. 2007. Network governance and policy integration: the case of regional coastal zone planning in Norway. Eur Plann Stud. 15(7):927–944.

- Hussaini SS. 2011. A feasibility study of the establishment of knowledge- management from the perspective of the infrastructure situation in district 8 of Tehran [ master’s thesis]. Tehran: Shahed University. Persian.

- [IMSC] Iranian Management Services Corporation. 2006. Strategic revision of Tehran metropolitan management system. Tehran: Tehran Urban Research and Planning Center. Persian.

- Institute of Economics of Tarbiat Modarres University. 2001. Designing the urban conurbation management systems of Iran. Tehran: Urban and Rural Research Centre, Ministry of Interior. Persian.

- Kazemian G, Mirabedini Z. 2011. Pathology of integrated urban management in Tehran from the perspective of urban policy-making and decision-making. Honarhaye Ziba J. 46(3):27–38. Persian.

- Kidd S. 2007. Towards a framework of integration in spatial planning: an exploration from a health perspective. Plann Theory Pract. 2(8):161–181.

- Kim J. 2004. Fiscal decentralization in Korea. Seoul: Korea Institute of Public Finance.

- Koresawa A, Konvitz J. 2001. Towards a new role for spatial planning. In: OEC Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, editor. Towards a new role for spatial planning. Paris: OECD Publication Service; p. 11–32.

- Lailhonen H, Lonnqvist A. 2013. Managing regional development, a knowledge perspective. Int J Knowledge-Based Dev. 4(1):50–63.

- Liebowitz J, Beckman TJ. 1998. Knowledge organisations: what every manager should know. London: CRC Press LLC.

- Mansouri SM. 2014. Analysis of the comprehensive plan for Tehran (CPTM). Tehran: Nazar Research Center.

- Motawef S. 2010. Integrated urban management and urban development planning organization of Tehran. Manzar J. 6:34–37.

- Nadin V. 2007. The emergence of the spatial planning approach in England. Plann Pract Res. 22(1):43–62.

- Nijkamp P, Rietveld P. 1989. Information systems for regional policy evaluation. Ekistics. 56:231–238.

- Nonaka I. 1994. A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science. 5:14–37.

- [OECD] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2006. Competitive cities in the global economy. Paris: OECD Territorial Reviews.

- [OECD] Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2009. Building blocks for policy coherence for development. Paris: OECD Publishing Services.

- Otim S. 2006. A case-based knowledge management system for disaster management: fundamental concepts. Paper presented at: ISCRAM Conference 2006. Proceedings of the 3rd International ISCRAM Conference; May; Newark (NJ).

- Park CM. 2000. Local politics and urban power structure in South Korea. Korean Soc Sci J. 27(2):41–68.

- Park CM. 2006. Developing local democracy in South Korea: challenges and prospects. Paper presented at: IPSA 2006. Proceedings of the 20th International Political Science Association World Congress; Jul 9–13; Fukuoka (Japan).

- Pfeffer K, Baud I, Denis E, Scott D, Sydenstricker-Neto J. 2010. Spatial knowledge management tools in urban development. Paper presented at: N-AERUS 2010. Proceedings of the 11th N-AERUS Conference; Oct 28–30; Brussels, Belgium.

- [PBO] Plan and Budget organisation of Iran. 2004. Law of the fourth plan of economic, social and cultural development of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Tehran: PBO. Persian.

- Rubenstein-Montano B. 2000. A survey of knowledge-based information systems for urban planning: moving towards knowledge management. Comput Environ Urban Syst. 24:155–172.

- Sarrafi M, Nejati NA. 2015. New regionalism approach for improving the system of spatial development management in Iran. Hum Geogr Res. 46(4):857–874. Persian.

- Shannon MA, Schmidt CH. 2002. Theoretical approaches to understanding inter-sectoral policy integration. In: Tikkanen I, Gluck P, Pajuoja H, editors. Proceedings of the Cross-sectoral policy Impacts on Forests Event; Apr 4–6; Savonlinna, Finland, Joensuu: European Forest Institute.

- Shokuhi MSB, Mahmeli HRA, Qaffari N, Mostofi AN. 2012. Indicators and measures of Tehran master plan assessment. Tehran: Tehran Urban Research and Planning Centre. Persian.

- [SCI] Statistical Centre of Iran. 2018. Atlas of Selected Results of the 2016, 2011, 2006, 1996, 1986, 1976, 1966, 1956 National Population and Housing Census. Tehran: plan and budget organization. Persian.

- Stead D, Meijers E. 2004. Policy integration in practice: some experiences of integrating transport, land use planning and environmental policies in local government. In: Greening of policies: inter-linkages and policy integration. Proceedings of 2004 Berlin Conference on the Human Dimensions of Global Environment Change; Dec 3–4; Berlin (Germany).

- Stead D, Meijers E. 2009. Spatial planning and policy integration: concepts, facilitators and inhibitors. Plann Theory Pract. 10(3):317–332.

- Iran’s Supreme Council of Planning and Architecture. 2002. Tehran urban region plan. Tehran: Iran’s Supreme Council of Planning and Architecture Tehran. Persian.

- Tsekos T. 2003. Towards integrated policy making: remedying the public action dichotomy through information and communication technologies and learning. In: Rosenbaum A, Gajdosova LL, editors. State modernization and decentralization, implications for education and training. Public administration: Selected central European and global perspectives; Dec 6–8. Bratislava (Slovakia. Bratislava): NISPAcee. p. 12–18.

- The Structure of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government [TMG]. 2006–2018. Tokyo: Tokyo Metropolitan Government; [accessed 2018 Jul 21]. http://www.metro.tokyo.jp/english/about/structure/index.html.

- Underdal A. 1980. Integrated marine policy - what? why? how. Mar Policy. 4(3):159–169.

- Vonk G, Geertman S. 2008. Knowledge-based planning using planning support systems: practice-oriented lessons. In: Yigitcanlar T, Velibeyoglu K, Baum S, editors. Creative urban regions: harnessing urban technologies to support knowledge city initiatives. United Kingdom: Information science reference; p. 203–217.

- Wilson MI, Corey KE. 2008. The ALERT model: a planning-practice process for knowledge-based urban and regional development. In: Yigitcanlar T, Velibeyoglu K, Baum S, editors. Knowledge-based urban development: planning and applications in the information era. Hershey PA: IGI Global. p. 82–100.

- Yigitcanlar T, Velibeyoglu K. 2008. Knowledge-based strategic planning: harnessing (in)tangible assets of city-regions. Paper presented at: IFKAD 2008. Proceedings of the International Forum on Knowledge Asset Dynmics; Jun 26–27. Matera, Italy.

- Yue W. 2013. Measuring urban sprawl and its drivers in large Chinese cities: the case of Hangzhou. Land Use Policy. 31:358–370.

- Whitehead M. 2003. (Re) Analysing the sustainable city: nature, urbanisation and the regulation of socio-environmental relations in the UK. Urban Stud. 40(7):1183–1206.

- [ISNA] Iranian Students’ News Agency. 2006.Workshop of analysis of the Comprehensive Plan for Tehran (CPTM). Tehran: [ISNA] Iranian Students’ News Agency. Persian.