ABSTRACT

In 2018, UN-Habitat projected the total population of the planet was about 7.632 billion. Fifty-five percent were living in urban areas in which more than 20 percent were said to live in slum areas. Within the era of increasing urbanization, and in the context of Habitat III, this article highlights planning innovation of the sustainability transition in urban informality in the Middle East. Three themes are raised. The first is to trace the recent academic debate on urban informality transitions in the Middle East. The second is to ask whether it possible to borrow new planning innovations from the Global North and apply them in the Global South and Middle East. Finally, the present work considers whether it is possible to link between the theory and the practice of governance of sustainability transitions and urban informality. It concludes that the configuration of urban informality in light of sustainability transitions would enhance the continuous sociotechnical and political transitions in the Middle East.

1. Introduction

In recent years, several planning innovations, concepts, and theories have emerged in discussions of socio-economic, spatial, and political transformations of the Global North as well as the South which is especially notable in the area of the rapid development of technology. With the beginning of the Third Millennium, a new research arena questioned the ability of sustainable development to guide natural resources towards the needs of current and future generations and to adapt the planet to climatic changes, biodiversity degradation, and spatial and natural hazards. Many academic institutions in Europe have developed an approach that links the theory and the practice of sustainable urban transitions.

It is appropriate to look back to the roots of sustainability transitions which shows that our approach brings in new insights and/or new wine in old bottles. Notably, the orientation at sustainable integration of urban informality growth, resource security and spatial control reflect preferences for urban development pathways that do not substantially question or alter the status quo but strive for its socio-technical optimization. The integration of urban informality into the urban context would require tackling four subject areas. The first is the physical setting in which regulations and incentives to prioritize spatial equity over land should be applied. The second is the economic issues that incrementally increase the supply of serviced land to finance core services which have to satisfy the growing demand for housing plots. The third is a political commitment that embraces existing informal settlements in the political arena. Finally comes enhancing the social network by which inclusion of the social structure is accomplished, creates homogenous communities, and enhances the role of grassroots in the development process. These four subject areas reflect production, reproduction, consumption and distribution of goods and services. They are interrelated, connected, and are interlinked with the three modes of sustainability (complex systems, socio-technical perspective, and governance perspective).

This paper traces the evolution of planning innovation on the sustainability transition to examine the effect of theories on urban informality practice in the Middle East. The aim is to open an academic discussion on the theory and the practice of governance of sustainability transitions and its correlations in urban informality in the Middle East. It is not the intention to examine differences of planning theories between the Global North and South, nor to make a comparison between formality and informality. The question posed is, instead, why it is possible to apply approaches from the Global North in the Global South/Middle East. It is well to note that most scholars who have researched urban informality in the Global South have or are being educated in the western societies. For example, John Turner, Charles Abrahams, Geoffrey Payne, Forbes. Davidson, Mike Davis, etc. and it is very rare to find scholars speaking to the issues involved who are from the Global South.

To what extent does urban planning require a deep understanding of the context in which it proposes to intervene on urban informality and how should this understanding shape what planners do? Such questions challenge some long-held assumptions in sustainable transitions where both theory and practice have tended to smooth over this kind of sensitivity in favor of concepts and practices which are blind to place and held to be valid in the Middle East when such is not always so. The central assumption is that the societal system in the Global North went through long periods of relative stability and optimization that was followed by relatively short periods of radical change. But in the Middle East stability is very rare and new planning innovations are needed to overcome a fragmented situation.

This paper applies a deductive methodology to test concepts and patterns known from theory and practice. Theoretically, there is a huge literature questioning the governance of sustainability transitions, the formulation, and transitions of urban informality in the Middle East. Practically, the present work examines the linkages between urban informality and the way it has created, developed, and invested, and the possibility of investigating the role of urban informality and spaces in transitions which leaves it ill-prepared to understand and explain its geographically uneven development. In the conclusions, a comprehensive link of concepts, theories, and insights are touched upon. The article is structured as follows. Section two briefly explores urban informality transitions in the Global South/Middle East. Section three covers the recent debate on sustainability transitions. Section four examines the governance of sustainability transitions and section five outlines a possible paradigm on governance sustainability transitions on urban informality. A short conclusion then closes the paper.

2. Urban informality in the global South/Middle East

‘Slum’ is not a new phenomenon in modern societies. It is as old as the pre-industrial revolution period. Patrick Geddes (Citation1915) stated that an essential characteristic of the ‘Industrial Age’ is slum areas that were spreading everywhere in the British cities. Mumford (Citation1962) explored the development of urban civilizations in which slums formulated the structure of modern cities and were partially responsible for many social and spatial problems seen in western society. The underline of Geddes and Mumford’s thoughts is how to handle urban transitions of slum sustainably. These were the earliest, in the literature review, to look at slums/urban informality transitions from a wider perspective and to improve the level of the built environment’s sustainability.

In the literature, there are various thoughts towards the transformation of slum areas and the appearance of urban informalityFootnote1 in cities. Abrams (Citation1964) and Turner (Citation1976) were the pioneers to question the importance of the squatter settlements in tackling the housing problem in the Global South. To address this problem, and in line with the call for re-configuring the western inflected urban theories on urban informality, overcoming asymmetrical ignorance of non-Western cities and recalibrating geographies of authoritative knowledge (Gaonkar Citation2001; UN-Habitat Citation2003; Robinson Citation2006; Davis Citation2006; Roy Citation2009; Edensor and Jayne Citation2011). The dominant normative interpretation of urban informality should be critically re-examined within different cultural contexts from all over the world to broaden the understanding of its relevancy and limits (Dempsey and Jenks Citation2010).

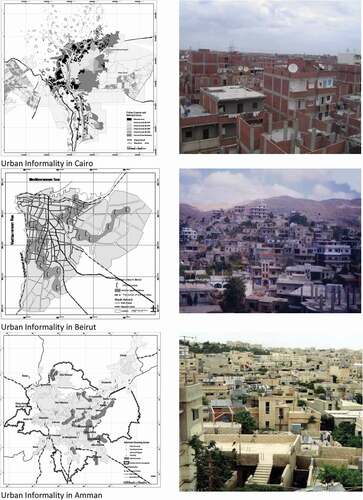

This gains a particular significance in the Middle Eastern context (Soliman Citation2012b), where the rapid population growth, political transformation, and intensive informal urbanization process has culminated in crucial socio-cultural and economic challenges, parallel to a shift in the urban pattern from planned to an unplanned/arbitrary pattern (Roy and Al-Sayyad Citation2004; Al Sayyad Citation2004; Sims Citation2010) or a community-driven pattern (Soliman Citation2017). In the Middle East, in Egypt, slums areas appeared in Ezbet (hamlet) El Lemoun, over 2000 years ago, during the Holy Journey of the Virgin Mary to Egypt which is located close to Mary’s Tree in El Matarya area adjacent to the city of Cairo (Soliman Citation2013). In Lebanon, slums have a long history dating back to the French Mandate period (1923–1943) (CDR Citation2016), and in Jordan during the WWI era (Ababsa Citation2012). As illustrated in , a synopsis of transformations of urban informality occurred during the last seven decades that was due to various socio-economic and political transitions in the Middle East. These transformations have occurred in three contexts: laissez-faire; status quo, and participatory which are interrelated and linked with the prevailing circumstances.

However, urban informality in a broad sense is attached to unusual and various kinds of arrangements, networks, activities, production, reproduction, distribution and consumption that produce ‘a new way of life’ (Al Sayyad Citation2004) or ‘ways of life’ living in a ‘culture of poverty’ (Lewis Citation1966). Many scholars view informal housing, or urban informality exclusively as a new type of built environment, or ‘a new urban pattern’ or ‘a new urbanity’ (Soliman Citation2013). Thus, what is the difference between housing informality and urban informality? In simple terms, housing informality reflects the informal process of housing production by the bottom strata of the society, while the latter reflects a context of various informal socioeconomic and spatial activities and a dual system of the sociopolitical arena.

This duality has to spread in the Middle East as a reflection of the dualism of urbanization, the absence of a proper planning framework, rapid population growth, and the scarcity of funds to finance ameliorating activities. However, urban informality as a concept is increasingly recognized as bridging the duality between formal and informal ‘sectors’ (i.e. economic, spatial, social, etc.), and processes (i.e. ‘a way of life’ (Al Sayyad Citation2004)), a new urban pattern (Soliman Citation2013), and is defined as a continuum rather than as a condition (e.g. Roy and Al-Sayyad Citation2004; Roy Citation2005; Jenkins Citation2013) and as the power of capital and capital accumulation which guides informal urban development (De Soto Citation2000). Urban informality reflects various aspects of activities (e.g. economic, social, political, etc.) and/or various commodities (e.g. land, building materials, etc.) extracted from formal and informal sectors by which is stimulated the advantages from both for the benefit of the bottom strata of the society. Many urban challenges are facing the formalization of urban informality in a sustainable way; one is the illegal land subdivisions and the insecurity of land tenure. The second is the shadow economy that dominated the informal landscape by which was influenced the level of production, reproduction, consumption, and distribution of goods and services. The third is the marginality and social exclusion of informal areas from the rest of a given environment, and finally, is the political exclusion of the citizens of informal areas in participating in the political milieu of a given setting.

The idea is how to formalize the informal sector or at least to integrate the urban informality into a formal context in a sustainable way. However, urban informality involves a broad range of diverse illegal activities involving various aspects of life, rather than a strategy (d’Alençona et al. Citation2018), and is processed and interacts legally and illegally with the prevailing transitional conditions of a given environment. It is a community-driven process involving undercapitalization. The role of the state fluctuates with urban informality (Soliman Citation2012b), as the state takes action towards urban informality according to the situation of the sociopolitical arena, not due to the weakness or the power of the state as indicated by Kreibich (Citation2012). Urban informality formulation differs from one country to another, from one city to another, even within a city itself, with the involvement of various complex pillars (Soliman Citation2004). With subsequent changes in lifestyle and status quo, especially after the Arab Spring in 2011, several transformations with varied characteristics of urban informality have emerged. These are related to the adaptation of spatial, economic, social, and political transitions to suit the requirements of the urban poor in the Middle East which are attributed to the following dimensions.

Firstly, from a spatial dimension point of view, many scholars elaborated and subdivided slums in the context of spatial development. Stokes (Citation1962), Gans (Citation1962), and Seely (Citation1959) differentiated between the ‘squatter’ and the ‘slum dweller’ of a city. Stokes, Gans, and Seely distinguished between the ‘slum of hope’ and ‘slum of despair’, ‘urban village’ and ‘urban jungle’, and the difference between ‘necessity’ and ‘opportunity’. These differentiations are due to the degree of physical improvement and legality of land tenure. The first type (slum of hope, urban village, and opportunities) is where people are living in an illegal situation and slums of this type are always in a dynamic process of transitions. The second type (slum of despair, urban jungle, and necessities) is where people are living in squalid conditions, but in a legal situation and a static process of transformation. However, urban informality in the Middle East represents slum of hope or ‘space of flows’ in which, over time, substantial physical improvements take place and over time informal settlements become more consolidated through applying the law in practice rather than law in text. For example, the consolidation of Manshiet Naseer, El Dyahiah El Ganoubyhia and East Wahdat in Cairo, Beirut and Amman respectively (Sims Citation2010; Fawaz Citation2009; Ababsa Citation2012) (see ).

Secondly, from economic points of view, in the mid-1950s, Lewis (Lewis Citation1954) suggested two models for understanding the employment of the new migration of people which identified ‘a state’ as a modern capitalist firm sector and ‘trade-service’ as a peasant households firm sector. The former sector is where people are working formally, the latter is where people are working illegally, or the former is the ‘modern’ mode of employment, while the latter is the ‘traditional’ mode (Bromley Citation1979). The formal/informal dualism was reified in the International Labor Office (ILO) report on Kenya (International Labor Office Citation1972). Since then a link between the informal housing sector and informal economy sector is considered, whatever their scale (e.g. Hart Citation1973; Bromley Citation1979; Lipton Citation1984; Moser Citation1994; Guha-Khasnobis et al. Citation2006), became interrelated and linked with urban informality. This was debated by De Soto (Citation2000) for many Middle Eastern countries. For example, the various economic activities in Ezbet El Haganha, El Ouzai, and Al Hussein in Cairo, Beirut, and Amman respectively (Fawaz Citation2009; Denis Citation2012; Ababsa Citation2012).

Thirdly, from a social point of view. Scott (Citation1986) classified the social classes into two sectors; subordinate class (informal), and superordinate class (formal). Class resistance includes any act(s) by member(s) of a subordinate class that is or are intended either to mitigate or deny claims (for example, rents, taxes, prestige) made on that class by superordinate classes (for example, landlords, large farmers, the state) or to advance its claims (for example, work, land, charity, respect) vis-à- vis these superordinate classes. Social networks in the Middle East are composed of the stakeholders from whom they access the necessary resources or ingredients to acquire housing plots and result in housing networks (Turner and Fichter Citation1972; Fathy Citation1973; Alexander et al. Citation1975; Turner Citation1976; Bourdieu Citation1977; Hasan Citation2001). Understanding how social networks contribute to the economic and social fabric of life in the Middle East is important (Woolcock and Narayan Citation2000; Collier Citation2002), and social cohesion and more powerful actors are critical for societies to prosper economically and for development to be sustainable (Adler and Kwon Citation2002; Wilk et al. Citation2018). Shirazi and Keivani (Citation2019) state the importance of social sustainability to form the basis of constructive dialogue and be interlinked with other areas of sustainable development. The interdependent nature of actors, their structures and connectivity, and the distribution of power are key components of marketing systems and sustainable communities in the Middle East.

Fourthly, politically corrupt vested interests’ groups view urban informality as a mass response to mindless, pompous bureaucracy, and the manipulations of the economic system. Even though urban informality in the Middle East may officially be illegal, it is not immoral because it breaks no basic moral codes and it is a simple necessity for the poor to make a living and satisfy their basic needs. Urban informality is a structure of action for survival that contains both harmonious (adaptation) and contradictory (resistance) relationships. It is a site of power concerning external disciplinary and control power (Laguerre Citation1994). This was noticeable during the Arab Spring and the recent Lebanese movements where a high proportion of protesters were coming from informal settlements asking for decent shelter, dignity, social justice, and a better standard of living. Fawaz (Citation2008) in her investigation of Lebanese informality stated that without systematically resorting to the terminology of social networks, the abundant literature that documented the formation of informal settlements during the 1970s and 1980s challenged their condemnation as ‘spontaneous’ by revealing that these neighborhoods were organized and managed through thick webs of social relations (Collier Citation2002; Perlman Citation1976; Ward Citation1982; De Soto Citation1989).

On the other hand, social networking in the Middle East depends on three types of capital: a symbolic capital, a social capital, and an investment capital. Symbolic capital is a ‘capital of honor and prestige’ (Bourdieu Citation1977) and depends on publicity and appreciation; it has to do with prestige, reputation, honor, etc. Social capital relies on economic, cultural or social capital in its socially recognized and legitimized form. Investment capital echoes the accumulation of capital through informal housing production to be used as realty in securing the residents’ economic future against any future economic crisis or unexpected inflation. Social networks within informal areas in the Middle East are playing a crucial role in first, creating organizations of their own so they can negotiate with government, traders and NGOs; second, directing assistance through community-driven programs so that they can shape their destinies; and finally, they sustain their command of local funds, so that they can eradicate corruption (Woolcock and Narayan Citation2000).

To sum up, housing informality in the Middle East is not an unregulated domain but rather is structured through various forms of social, economic, and discursive regulation. Second, it is a way to formulate ‘a new space in the city within the city’ or ‘spaces of flows’ to squeeze the growing population where various strata of the society find their way out to reproduce a space within spaces. Third, it is becoming a matter of capital investment in land and it has a fundamental importance in the urban poor’s rights, for it brings other developmental benefits (for instance, access to services and credit or political voice). In other words, housing informality became an issue of ‘Socioeconomic Struggle’ for meeting the basic human needs that the states, since the mid-sixties, could not tackle with respect to the housing needs for most of the populations in cities of the Middle East. In this sense, housing informality became an expression of class power, capital accumulation and in time, demanded different infrastructures, social services, and legitimacy in urban areas. Fourth, people involved in housing informality have created their distinguished urban pattern which formulates ‘a new urbanity’ different than the one produced by the states or by the European model. Fifth, some people have the capital and knowledge to benefit from transitions, while others are yet incapable of being integrated. Finally, a social sustainability dimension (Shirazi and Keivani Citation2019) reflects the needs and aspirations of the residents in informal housing which contributes to a comprehensive and cohesive ‘urban agenda’ that is built on three principles of recognition, integration, and monitoring. In short, housing informality is ‘a dynamic, transactive, transformative and transmissive space’ that better responds to evolving circumstances and contemporary national challenges in a wholly formal or informal private land market, and it is being integrated with the socioeconomic and political circumstances of the country. The question is how to integrate or interrelate urban informality within the formal context in a sustainable way.

3. Sustainability transitions

In recent years, planning innovations have taken place aiming at sustainability transitions for the future of urban agglomerations development on the planet.Footnote2 The transitions research is the recognition that many environmental problems, such as climate change, loss of biodiversity, resource depletion, spreading of urban informality, and many others are urban challenges problems. The concept of transition has been studied for decades in several disciplines, e.g. in biology and population dynamics, in economics, in sociology, in political science, in science and technology studies, and systems sciences (Grin et al. Citation2010), but very rarely are spatial transitions touched upon. Transition in sustainability are shifts or ‘system innovations’ between distinctive socio-technical configurations, encompassing not only new technologies but also corresponding to changes in markets, user practices, policy, cultural discourses, and governing institutions (Geels et al. Citation2008; Markard et al. Citation2012). Economic, cultural, technological, ecological, and institutional subsystems co-evolve in many ways and can reinforce each other to co-determine a transition (Turnheim et al. Citation2015).

Leftwich (Citation2010) defines transitions as all the activities of co-operation and conflict, within and between societies, whereby the human species goes about organizing the production, consumption, and distribution of human, natural, and other resources in the production and reproduction of its biological and social life. This disciplinary diversity reflects the wide-ranging and multi-dimensional nature of transitions, anchored in the concept of politics typified by Leftwich. On the other hand, sustainability transitions are system innovations that influence geographical settings through changes of socio-technical, economic technical, and political configurations of a specific location (international, national, local) or a specific context (e.g. housing production, street trading, land market, etc.), changing the behavior of humans, changing the urban pattern, and organizing natural resources in a sustainable way for meeting the needs of a population. These transitions occur according to several variables: co-evolution and multiple changes in socio-technical systems, multi-actor interactions between social groups, ‘radical’ change in terms of scope of change, and periods that witness transitions (Geels and Schot Citation2007). Various models developed in this field aim to explain how transitions unfold and how to govern them (Koehler et al. Citation2017).

Köhlera et al. (Citation2019) summarized nine themes which address different aspects of transitions or transitions research. These themes are: Understanding transitions; Power and politics in transitions; Governing transitions; Civil society, culture, and social movements in transitions; Organizations and industries in sustainability transitions; Transitions in practice and everyday life; Geography of transitions: spaces, scales, places; Ethical aspects of transitions: distribution, justice, poverty and, Reflections on methodologies for transitions research. The first theme addresses conceptual frameworks that aim to capture the complexity and multi-dimensionality of sustainability transitions. Themes 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 focus on particular social groups and dimensions, mobilizing observations from various social sciences to provide deeper insights. While transitions research has always been strong in the temporal dimension, theme 7 addresses the spatial dimension of transitions. Themes 8 and 9 are new compared to the New Urban Agenda. The former addresses ethical issues and the latter moves from modeling to discussing methodological questions in general (for further debate see Köhlera et al. Citation2019). It can be argued that all the above themes do not work separately, but are interrelated, linked, and connected to formulate an effective sustainable transition in a given environment such as the Middle East region.

Sustainability transitions have several characteristics that make them a distinct (and demanding) topic in sustainability debates (Köhlera et al. Citation2019). These characteristics are as follows. 1) Multi-dimensionality and co-evolution; socio-technical systems consist of multiple elements. 2) Multi-actor process; transitions are enacted by a range of actors and social groups. 3) Stability and change; a core issue in transition research is the relationship between stability and change. 4) Long-term processes; transitions are long-term processes that may take decades to unfold. 5) Open-mindedness and uncertainty; in all domains, there are multiple promising innovations and initiatives. 6) Values, contestation, and disagreement; the notion of sustainability is, of course, highly contested, so different actors and social groups also tend to disagree about the most desirable innovations and transition pathways for sustainability transitions. 7) Normative directionality; since sustainability is public goods, private actors (e.g. firms, consumers) have limited incentives to address it owing to free-rider problems and prisoner’s dilemmas (Köhlera et al. Citation2019).

Relying on various terminologies, discourses, methodologies, and scales, different disciplines describe transition processes as follows. Transitions are the result of alternating processes of slow and rapid change leading from one relatively stable/unstable state to another. Transitions are the result of coevolutionary processes occurring at different levels of scale and in different environments. Transitions are highly unpredictable and uncertain in terms of their speed and direction. Transitions are driven by changes in the external environment of a system as well as internal innovation (Loorbach Citation2007) and occur at all times led by various actors, forces, and changes.

As illustrated in the correlation between sustainable transitions processes and spatial transitions of urban informality interact and are correlated with four main variables: sustainable transitions dimensions, the concept of transitions, transitions levels, and level of intervention. Urban informality as complex adaptive systems (Rotmans Citation2006) is in a continuous process of rapid physical changes and has the opportunity to be sustainably integrated into the urban context. This inherent complexity requires thinking of urban informality in the Middle Eastern cities as never being finished and facing continuous change.

Figure 3. The correlation between sustainable transitions and urban informality Transitions

The first variable involves sustainable transitions dimensions which are linked and integrated with urban informality transitions where three themes are emphasized: complex systems analysis, a sociotechnical perspective, and a governance perspective. These themes are in a continuous complex of processes and are related and linked to the concept of transitions, transitions level, and level of intervention. The three themes are as follows.

One is the complex systems analyses which are reflecting the transition approach. It distinguishes three different levels of analysis: financial and banking crises, relations between market, government and society, and values and their expression in life-styles (Grin et al. Citation2010). It also reflects the production, reproduction, distribution, and consumption of spaces within spaces in which certain commodities or activities are produced. These transitions depend on various certainties and uncertainties, and interrelated levels of changes (Koehler et al. Citation2017). Deeper and more fundamental shifts may exist towards different cultures, structures, and practices that are inherently sustainable rather than less unsustainable (Loorbach et al. Citation2016). In this sense, urban informality changes can occur through complex interactions, making total control of a city in the Middle East a major challenge, especially through control of the development of land, as the main component for spatial production. As some cities in the Middle East have 50 percent of their population living in spontaneous areas (Soliman Citation2012b), it becomes a question of how to govern or/sustainably guide and control such rapid informal urbanization.

Another involves the socio-technical systems which are the combination of human and non-human factors that create functional configurations that work (Grin et al. Citation2010). It is not just a matter of social systems, but also of socio-technical systems which consist of multiple elements (technologies, markets, user practices, cultural meanings, infrastructures, policies, industry structures, and supply, consumption, and distribution chains). In the socio-technical perspective on transitions (Geels and Schot Citation2010), power is primarily understood in terms of the regulative, cognitive and normative rules underlying socio-technical regimes, and the ‘power struggles’ between incumbent regimes and upcoming niches. Geels and Schot (Citation2007) argued that position power is a specific perspective on an agency that revolves around actors and social groups with ‘conflicting goals and interests’, about which views change as the outcome of ‘conflicts, power struggles, contestations, lobbying, coalition building, and bargaining’. On the other hand, Swilling et al. (Citation2016) have argued a need to reconsider ‘socio-technical’ regimes as ‘socio-political’ regimes in the context of development studies. However, the politics of geographic boundaries intertwine with the development of specific technologies that are crucial (e.g. (Castán Broto Citation2016)) and interrelated with the governance and the management.

The final theme is the governance perspective on transitions. Grin et al. (Citation2010) discuss transition agency in terms of agents’ capacity of ‘acting otherwise’ (in reference to Giddens) and triggering institutional transformation by ‘smartly playing into power dynamics at various layers’ (in reference to Healey) and various settings (such as Cairo, Beirut, and Amman). Moreover, Grin links the MLP to an existing multi-leveled power framework by Arts and Van Tatenhove (Citation2004). Grin argues that the three levels of power distinguished correspond to the three levels in transition dynamics: (1) relational power at the level of niches, (2) dispositional power at the level of regimes, and (3) structural power at the level of landscapes (Grin et al. Citation2010). On the other hand, the power of the law at the three levels plays a critical role in determining the level of transitions in which law in text differs from law in practice. The latter is applicable on the ground. The differentiation between the two laws has encouraged people in the Global South to act illegally in their built environment in which urban informality has flourished (Soliman Citation2017).

The second variable is the concept of transitions. Grin et al. (Citation2010) try to analyze the sociotechnical perspectives through linking between four issues: co-evolution, the multilevel perspective, the multi-phase process, and the co-design and learning course. The higher the scale level the more aggregated the components and the relations and the slower the dynamics are between these actors, structures and working practices (Koehler et al. Citation2017). The four issues represent functional relationships between actors, structures and working practices that are closely linked and are categorized as follows.

For the first issue, Grin says that in a biological or economic context, co-evolution refers to the mutual selection of two or more evolving populations. He suggested that co-evolution is the interaction between societal subsystems that influences the dynamics of the individual societal subsystems, leading to irreversible patterns of change.

In the second issue, as illustrated in , the Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) conceives of transition as interference of processes at three levels: niche, regime, and landscape (Schot Citation1998; Rip and Kemp Citation1998; Geels Citation2005; Schot and Geels Citation2008). The central level comprises socio-technical regimes and sets of rules and routines that define the dominant ‘way of doing things’. Regimes account for path-dependence, stability and are often locked-in, which hinders radical change. Regimes are stabilized by the socio-technical landscape, a ‘broad exogenous environment that, as such, is beyond the direct influence of actors’ (Grin et al. Citation2010), and what time consumes. The landscape encompasses such processes as urbanization, demographic changes, and wars or crises that can put pressure on regimes making them vulnerable to more radical changes. Regimes transform on condition of availability of alternatives that can fulfil the same societal function. Alternatives are developed in niches, protected spaces that facilitate experimentation with novelties.

Figure 4. The multi-level perspective of sustainability transitions and its levels

The third overarching issue is Multi-Phase (MP). The multi-phase concept describes a transition in time as a sequence of four alternating phases: (i) the pre-development phase from dynamic state of equilibrium in which the status quo of the system changes in the background, but these changes are not visible; (ii) the take-off phase, the actual point of ignition after which the process of structural change picks up momentum; (iii) the acceleration phase in which structural changes become visible; (iv) the stabilization phase where a new dynamic state of equilibrium is achieved.

The final shared issue is that of co-design and learning (Grin et al. Citation2010), sometimes called learning by doing, and doing by learning. This means that knowledge is developed in a complex, interactive design process with a range of stakeholders involved through a social process of learning (Grin and Loeber Citation2007; Grin et al. Citation2010) and participant observation (Alexander et al. Citation1975).

The third variable is the transitional levels. It represents an integrated and cross-sectoral approach (horizontal and vertical coordination). The transition levels process occurs with horizontal and vertical coordination. The former occurs at three levels: macro, meso and micro levels, while the latter occurs at various stages of transitions. These levels are responsible for facilitating the integration of urban informality to the urban context and enhancing the land delivery system for low and middle-income groups.

The final variable is the level of intervention which is dramatically varied according to various aspects of transitions, and according to various settings. While financing and investing with lasting effects, the concentration of resources and funding on selected target areas are considered the main tools for active intervention. Also, capitalizing on knowledge, exchanging experience and know-how (benchmarking, networking), or learning by doing or doing by learning are concrete methods to control or speed up the level of transitions. Social networks, social sustainability, actors and institutions are promoting ‘lock-in’ and path dependency (Dixon Citation2014; Soliman Citation2019; Shirazi and Keivani Citation2019). Monitoring the progress (ex-ante, mid-term and ex-post evaluations, and indicators) is the main indicator to accelerate the transitions process.

One of transition analysis’s weakness has been its capacity to deal with the duality in the Global South, duality on economic, social exclusion (De Soto Citation2000), the duality of the urban fabric, and duality in political-technical (such as Lebanon) via evolutionary long-term trajectories of socio-technical change. Diversity and reliance on different alternatives that work at a moment are used by society as risk-minimizing strategies. In these circumstances, scholars find it difficult to ‘establish’ fully coherent regimes or groups of individuals who share expectations, beliefs or behavior (Byrne Citation2009; Campbell and Sallis Citation2013; Wieczorek Citation2018). Also, norms, traditions, behavior, ways of life, and cultural diversity make cities of the Middle East work according to these norms regardless of specific planning in which many pathways might exist. Societies in the Global South rely on a variety of alternatives and develop new practices for affordable housing plots and services. On the other hand, the concept of affordability has to do with three orders: the housing expenditure-to-income ratio, the residual income approach, and the incremental affordability approach (Bredenoord et al. Citation2014), which become very changeable over time. Among these alternatives are sites and services and upgrading programs in which are offered housing plots at reasonable prices (Davidson and Payne Citation1985). This depends on the level of niches, the nature of the regime, and the final output of the landscape. Research on transitions has long been criticized for its spatial narrowness (Coenen et al. Citation2012; Truffer et al. Citation2012) leading to several theoretical and empirical advances (e.g. Lawhon and Murphy Citation2012; Wieczorek et al. Citation2018; Köhlera et al. Citation2019). Systems in the Middle Eastern cities are particularly interesting to investigate in that respect; especially those that are part of global value chains with strong transnational characteristics and those that are encouraging community-driven processes.

Also, the conceptualization of the local community level (grassroots level) (Seyfang and Smith Citation2007; Soliman Citation2012a, Citation2017) as a valid site for innovation towards urban informality sustainability pursuit, i.e. as constituting the niche level in the urban areas. The potentials and accomplishments of diverse types of community initiatives and grassroots movements are acknowledged transformative change for sustainability articulated around alternative values and social practices (Wolfram Citation2017). Despite increasing attention to thoughts of these transformations in the transition’s literature (Hoffman Citation2013; Geels Citation2014; Avelino et al. Citation2016), a closer look at the questions of which transformation for whom, how, why, when, and by whom? These questions are relative to the Middle Eastern cities as most of these cities exhibit tremendous illnesses of their geographical, social, economic and political aspects. Also, they are characterized by ill-functioning institutions, fluctuations of economic status, client lists, and socially exclusive communities, and many proletarians. In the Middle East, informal institutions such as norms, values, and cultures play a pivotal role in transitions processes. They either shape informal institutions or, more often, prevail in cases where formal institutions and markets fail. The later has accelerated the informal economy system which constitutes more than 50 percent of the national economy in certain countries in the Global South (Bromley Citation2004).

4. Governance of sustainability transitions

Governance transitions imply a less state-centric view of politics and give attention to issues of negotiation, deliberation, and self-governance (Kemp et al. Citation2007). It is about the structured ways and means in which the divergent preferences of inter-dependent actors are translated into policy choices to allocate values so that the plurality of interests is transformed into coordinated action and the compliance of actors is achieved. Various approaches were developed to direct transitions that aim to produce analyses of transitions, but also prescriptive advice on how to steer transitions, including work on Transition Management (Rotmans et al. Citation2001; Loorbach Citation2010), Strategic Niche Management (Kemp et al. Citation1998; Hoogma et al. Citation2002), and Reflexive Governance (Voss et al. Citation2006; Voss and Bornemann Citation2011).

The challenges of how to steer transitions in desirable directions, but also of how to do so within timescales that help avoid dangerous environmental change (e.g. Sovacool Citation2016) and/or devastation of the urban fabric of a given environment. Classic work on governance (Kooiman Citation2003) defines governing as ‘the totality of interactions, in which public, as well as private actors, participate, aimed at solving societal problems or creating societal opportunities; attending to the institutions as contexts for the governing interactions, and establishing a normative foundation for all those activities’.

Kemp et al. (Citation2007) distinguish governance transition and transitions management. The former, a governance approach based on insights from governance and complex systems theory as much as upon practical experiment and experience (Loorbach Citation2007). The governance perspective to sustainability transitions suggests, in line with sustainability theories and approaches, that governance and policy require a radically different set of guiding principles in the context of sustainability transitions. The question is how we develop policy-relevant scenarios and toolboxes based on interdisciplinary knowledge generated by transition scholars. A participatory and deliberative fashion is engendering a commitment to sustainability values as steering mechanisms and tools that coordinate societal and political processes.

Transitions management is a promising model for sustainable development, allowing societies to explore alternative social trajectories in an adaptive, forward-looking manner involving long-term goals and adaptive programs for system innovation (Kemp et al. Citation2007). Meadowcroft (Citation2007) describes transitions management as follows:

“the theory has a modular structure, with several elements being combined to produce the whole. Particular components include the image of the transitions dynamic with the distinct stages of the transitions process; a three-level analytical hierarchy of ‘niche’, ‘regime’, and ‘landscape’ that provides a framework for understanding transitions processes; a basket of future-oriented visioning devices (goals, visions, pathways, and intermediate objectives); a practical focus for activities (arenas and experiments); and a broad ‘philosophy of governance’ that emphasizes decision-making in conditions of uncertainty, and the gradual adjustment of existing development pathways in light of long-term goals.”

In transitions management, the governance process is a cyclical process of development phases at various levels of scale (Loorbach Citation2007). The transitions management cycle involves four different types of governance activities which can be distinguished when observing actor behavior in the context of societal transitions: strategic, tactical, operational and reflexive (Frantzeskaki and Loorbach Citation2012). These activities exhibit specific characteristics in terms of the type of actors involved, the type of processes they are associated with, the type of product they deliver, and the level of consumption which make it possible to (experimentally and exploratively) develop specific instruments that have the potential to govern transitions processes (Frantzeskaki and Loorbach Citation2012).

To sum up, the issue of the governance of urban sustainability transitions on urban informality in the Middle Eastern countries is very rarely emphasized in the literature and the research arena. Using combinations of the two criteria of the timing of interactions and nature of the interactions, four different transition typologies are developed (Geels and Schot Citation2007). These are transformation, reconfiguration, technological substitution, and de-alignment and re-alignment. An additional fifth proposition addresses a possible sequence of transition paths, i.e. how transitions may start with one path, but shift to others. The linkage between these typologies with Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) is the outcomes of alignments between the transformations of urban informality at multiple levels. These transitions typologies have been developed conceptualizing the different pathways that urban informality transitions may take depending on the configuration and timing of the interactions between landscape factors, niche-level innovations and socio-technical regimes (See Geels et al. Citation2016; Geels and Schot Citation2007; Wieczorek Citation2018; Mguni Citation2015). This is quite clear within urban informality in which a range of collaboration or special social networks among citizens has facilitated the development of affordable housing plots. Lefebvre argued that urban governance unfolds across geographical scales, as urbanization processes include cities, regions, cross-border agglomerations, as well as supranational hierarchies (Lefebvre Citation1991). The following section demonstrates a comprehensive link of concepts, theories, and insights towards ‘how to’ the governance of sustainability transitions on urban informality.

5. Governance of sustainability transitions on urban informality

Transitions as processes of ‘degradation’ and ‘breakdown’ versus processes of ‘build-up’ and ‘innovation’ (Gunderson and Holling Citation2002) have been witnessed in history (Geels Citation2004), and the question emerges of how to handle it at present as well as in the near future. Thus, governance of sustainable transitions on urban informality relates to unsustainable production, consumption and distribution patterns in socio-technical systems such as land plots, electricity, water, sanitary system, mobility, and legalizations. These problems cannot be addressed by incremental improvements or upgrading, but require shifts to new kinds of systems, shifts which are called ‘sustainability transitions’. But how do sustainability transitions stimulate urban informality transitions?

Soliman (Citation2012b) stated that housing informality, as a commodity or a product or a consumable, does not operate in isolation. Rather it depends on the domination of capital, labor, a willingness of the state, collective resources, and cooperation among all stakeholders. There one recognizes the local people and their capability for handling financial investment, managing and maintaining the physical environment, controlling the local resources, and their competence in participating in the national economy (Soliman Citation2019). The development processes of urban informality created through social networks and cultural norms depending on the organizational bases that dictate those rules and the means among the residents. Also, the state’s institutions play an important role to support, directly/indirectly or not support, what people do, the way people manage their environment, and how to regulate the prevailing law to be for the benefit of the collective resources generated by the urban informality. However, urban informality is the result of continuous urban transitions that resulted from a cooperation or an arrangement or relationship among a group of actors (whatever the level, the size and the type of actors involved), the result and the functions of capital (whatever the amount and sort), state involvement (whatever the level of intervention), and the nature of the built environment being produced. Urban informality is promoting sustainability where value-for-cost is maximized, thereby allowing residents the opportunity to control the built environment, and where people are encouraged to invest in shared amenities. illustrates an example for the formalization of urban informality as a Participatory and Inclusive Land Readjustment program (PILaR) in El Rezqa area in Benha city which is located approximately 45 km north of Cairo, Egypt’s capital. Its objective is to apply a PILaR as a tool to promote sustainability and integrate the new arbitrary urban expansion, sustainably, into the urban fabric in Egypt (Soliman Citation2017). In short, urban informality is the manifestation of such informal processes in urban areas (Roy and Al-Sayyad Citation2004).

Figure 5. Illustrates an example for formalization of urban informality as a PILaR. Top left shows El Rezqa area before the implementation of PILaR. Top right shows the urban pattern of El Rezqa site after the implementation of PILaR. Bottom demonstrates the current construction process of El Rezqa area according to the official approval of PILaR

The question is how to alter urban informality transitions, and how to make these areas sustainable, and how they will be governed and integrated with the urban context. The sustainability and transformations of urban informality, in particular in cities of the Middle East, is the practice of everyday life (Lefebvre Citation1971), social security (Gough et al. Citation2008), and economic investment that constitute a new pattern of urbanity (Soliman Citation2012b). These transformations are predicated upon and conditioned by governance, production, reproduction, consumption, and distribution of housing, economic activities, and social amenities for the bottom strata of the societies in the Middle East.

Linking the MLP with the MP, a model of urban informality transitions in the Middle Eastern cities has emerged through interactions between processes at three structural levels of niches, regime, and landscape perspective, and the four phases of the MP (Grin et al. Citation2010). As illustrated in the model draws socio-technical transitions and the MLP through the interaction and correlation among the three levels of niche-innovations, regime, and landscape while the MP draws four phases of transition: predevelopment, takeoff, acceleration, and stabilization. It continues to process in two directions, vertically, and horizontally in which interactions occur between the MLP and the MP through various pathways. These pathways highlight socio-cognitive aspects of the regime’s rules and their changes which potentially shape socio-technical transitions.

Figure 6. The linkage between sociotechnical systems, the MLP and the MP in urban informality

This model provides X-curve transition phases and pathways (Loorbach and Oxenaar Citation2018) through the interactions between various levels of the MLP and the MP to create an enabling milieu, sustainable urban management: new residential areas, upgrading of existing informal areas, enhancement of social amenities, guiding new informal development on new bright sites (virgin areas, etc.) for the acceleration of desired transitions. The final landscape of this process is four outputs: formal development, formalization of informal areas, upgrading of existing urban informality and, finally, encouraging community-driven processes in newly established areas. In each phase of the transition, vertically and/or horizontally different strategies and instruments (pathways) can be used to create a sustainable urban fabric for the uptake of natural dynamic transitions; population growth, production, reproduction, distribution, consumption, capital dynamics, etc. The learning concept is the output of gaining pieces of knowledge generated from the several phases of the progress and the mechanisms of different pathways.

This model has the advantages that, first, it comes with the dynamic of the duality of economic and social exclusion in the Middle East. Second, it is a flexible process that meets changes beyond the formal/informal and regulatory framework, including also behavioral, cultural and practical changes caused by rapid transitive urbanization. Third, it is an adaptable model to cope with outer and inner forces (economic, social, and political) that might affect the emergence of societies. Fourth, it copes with natural disasters, local conflicts, poverty degradation, spreading of informal urbanization, fluctuation of the market, etc. Fifth, it is an elastic model that works with a diversity of actors, to be able to challenge incumbent ideas and interests and to creatively adapt methods and tools to different contexts requiring specific skills and capacities. Finally, it is flexible with various transitions and allows us to lock-in/out the privileging circumstances.

In general, urban informality in the Middle East is the output of the domination of capital and its reproduction (De Soto Citation2000; Bromley Citation2004), the size of production (Turner and Fichter Citation1972; Fathy Citation1973), the level of consumption (Ward Citation2004; Davis Citation2006; Sims Citation2010; Perlman Citation2010; Soliman Citation2017), societal technical (Harvey Citation1985, Citation2016; Mitlin and Satterthwaite Citation2004; Roy and Al-Sayyad Citation2004; Hatina Citation2007; Soliman Citation2019; Shirazi and Keivani Citation2019) and the means of distribution.

The above model relies on developing four pathways and sequence of transition pathways, many other pathways may exist in the proposed model. As illustrated in there are four pathways on the urban informality transitions in cities. These range from reproduction of capital perspectives, including interrelated and linkage between capital performance, new buildings, and housing mechanisms; production performance, including housing mechanisms, conventional planning, and building scale; consumption perspectives, including building scale, institutional framework and users and uses lifetime trends; and socioeconomic perspectives including users and uses, urban fabric, and capital performance as the ‘urban sustainable community’ discourses. These pathways reflect the governance of sustainability transitions on urban informality through four dimensions: the paradigm of urban informality; laws, norms, and practices and their expression in life-styles (Lefebvre Citation1971); land right and property transitions perspectives (Payne Citation2002), and social sustainability and right to the city. Linking these four pathways with the MLP and the MP, and the four main dimensions would develop eight sub pathways which result in the final sustainability transitions on urban informality for the four stages of development stated above. These innovations trigger further adjustments in the architecture of the niches, the regime, and the landscape. Also, the MP development and its interaction and correlations with the MLP might create many pathways according to various circumstances for governance sustainable transitions on urban informality. This would yield a range of dynamic patterns that combine in different ways to produce multiple pathways.

Figure 7. A linkage between four pathways on the urban informality transitions in cities

6. Conclusion

It is important to realize that sustainable development on urban informality can apply at various levels of buildings, neighborhood, city, regional, national, and international scales. Frequently the proposed model has treated the built environment not only as spatially connected and complex, but also a socioeconomic complex that generates goods and services for the urban fabric. This sociotechnical connectivity relates to the complexity of infrastructure, spaces and places and communities together with how urban form and function relate. In this sense, a focus purely on buildings leads to a lack of strategic focus. Moreover, as Bai et al. (Citation2010) suggest there is frequently an inherent temporal (‘not in my term’), spatial (‘not in my patch’) and institutional (‘not my business’) scale mismatch between urban decision-making and global environmental concerns, where urban decision-makers are often constrained within short timescales, the immediate spatial scale of their jurisdictions, and within ‘nested’ governmental hierarchies.

The governance of sustainability transitions and its linkages in urban informality in the Middle East is the cornerstone of this paper. The goal is to clarify three themes: ongoing research innovation on the governance of sustainability transitions, a brief synopsis of urban informality in the Middle East, and how to deal with urban informality sustainably. Our ‘hub and spokes’ provide a structured illustration of the different dimensions attributed to ‘sustainability transitions on urban informality’ in the literature. What is suggested here, then, is the logic of directing the flashback of the topic of urban informality as the main challenge facing the Middle East, as well as, an in-depth look at the governance of sustainability transitions. It is convincing that governance of sustainability transitions on urban informality to do so or not to do so will have a great deal to do with whether the polarization of societies in the Middle East will be increased or diminished within the next decade or two. Societal systems in the Middle East go through long periods of relative instability that are followed by arbitrary spatial change resulting in a fragmented situation. Three important points are emphasized in this context.

Firstly, the unifying element to the sustainability transitions concentrates on climate changes, energy consumption, deterioration of natural resources, etc., and very rarely are the ongoing rapid changes in the urban fabric of cities in the Middle East touched upon. This paper has demonstrated that many of the existing debates in the literature are inherently inclusive to the Global North as they mix different explicit and implicit dimensions that are different than those in the Middle East. Also, it is very rare to question urban informality and its negative impact on the urban context from a sustainability transitions viewpoint. The transitions approach does not offer a blueprint or a guidebook on how to govern such processes. The transitions approach offers conceptual frames for a better understanding of the dynamics of transitions and the co-evolution of the different societal subsystems throughout a transition.

Secondly, different strands of the transitions literature have focused on different facets of the relationship between state intervention (regime) on the one hand and societal autonomy on the other (niche), ignoring the influence of market forces and political transferee on the ongoing transitions. This literature illustrates that the credibility of a plan or a policy depends not only on the plan or policy itself, but also on the context and conditions in which it is developed and implemented and on the motivations and incentives of the authorities responsible. Accordingly, a conception of sustainability transitions and how urban informality could be sustainable has arisen. The paper highlights a sequence of correlations between concepts of transitions, transitions level (macro, meso, and micro), level of intervention (market forces, government’s policies, NGOs, and society), sustainable transitions dimensions and the integration of urban informality with urban context in more detail and presented a planning process of three modes of sustainability (complex systems, socio-technical perspective, and governance perspective) in the four dimensions: physical, economic, political, and social networks adaptation. These four dimensions are distinguished along with three variables: the type of instruments applied by the approach (legally binding legislation or soft law) to the implementation (flexible or rigid) and the motivations and incentives of the authorities responsible. Further pathways for the other dimensions could follow suit.

Thirdly, a land issue is considered the main component of informal residential development (Payne Citation2002; Wakely Citation2018) and its relationship with the informal economy and marginality. Relying on the MLP and the MP four possibilities of land typologies have emerged: formal, informal, hybrid, and new bright sites. Each has certain treatments and adaptations. Land typologies adaptions, as the main mechanisms of urban informality, have to be within the context of sustainability transitions dynamics including locked-in/out regimes that are challenged by changing contexts, ecological stress and societal pressure for change as well as experiments and innovations in niches driven by entrepreneurial networks, and creative communities and proactive administrators. The development of locations with basic urban services to provide affordable land plots for housing the new generations is the responsibility of the government. In other words, the governments should provide things that the majority of the population cannot provide for themselves, while the construction process of houses is the responsibility of the citizens. Now the Middle East, especially after the Arab Spring, has lost its way in following a certain theory of planning in tackling the perpetual challenges of affordable land plots.

However, it appears that the configuration, interrelation, and integration of urban informality within the urban sustainability transitions would enhance the continuous sociotechnical and political transitions in the Middle East. Also, it could be said that sustainability transitions are resisted by vested interests, uncertainties about the future amongst urban populations, political instabilities, and the erosion of social services and systems of provision. The development of a city vision that goes beyond each planning scheme is embedded in the city-regional context. These transitions occur and are interrelated according to four variables: co-evolution, multilevel, multi-phases and co-design, and learning changes in socio-technical systems interactions between complex systems (e.g. planning regulation, land delivery system, housing production, capital forces, etc.), socio-technical perspective (e.g. population growth, population mobility, social groups, ‘radical’ change in terms of scope of change traditions, norms, etc.) and governance perspective (e.g. institutions’ management, political transitions, community-driven process, period that witnesses transitions, etc.).

It is hoped that the idea of this research will open further research arenas in the Global South and the Middle East to further investigate creating a sustainable environment from its roots that would alleviate future disasters and avoid future deterioration of the built environment. But this article also expects patterns in processes and dynamics of transitions to be found across the diversity of urban informality in the Middle East. Last but not least, it is hoped that this article opens a new arena of scientific discussion between urban informality and transitions perspectives, between conceptual and empirical, between structural and practical, and between the theory and the practice of governance of sustainability transitions and urban informality.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Mrs. Margaret Deignan of Springer International Publishing AG, Springer Nature, Germany, for her time, energy and support for her constructive comments throughout the process of the acceptance of the manuscript for the publication of a book written by the author entitled “Experiencing Urban Informality: Politics, Economics and Culture in Middle East Cities” from which the idea of this present article emerged. The two anonymous reviewers’ comments helped improve the paper, for which I am grateful for their valuable help and support. The comments and valuable support of Prof. Ramin Keivani, the editor of this journal, are also very much appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ahmed M. Soliman

Ahmed M. Soliman is former a chairman of the Architecture department and Acting Dean of Faculty of Engineering, Alexandria University. Currently, he is Emeritus Professor of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Alexandria University, Egypt. He has written, edited, or contributed to many international publications as a specialist in housing informality and urban development, and he is the author of A Possible Way Out: Formalizing Housing Informality in Egyptian Cities (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2004). His most recent book project is Experiencing Urban Informality: Politics, Economics and Culture in Middle East Cities, Springer Nature (under contract expected 2020).

Notes

1. ‘Urban informality’ is used to describe a range of behaviors and practices unfolding within cities. Generally, ‘informality’ refers to a category of income-generating, servicing or settlement practices that are relatively unregulated or uncontrolled by the state or formal institutions. Urban informality is defined as any acts/activities in life that does not obey the prevailing law or does not follow the umbrella of formal institutions, and outside of the morals of a way of life. Urban informality includes housing informality, economic informality, and informal features of life (social, culture, political, and everyday life). For a further debate on urban informality see Roy and Al-Sayyad (Citation2004) d’Alençona et al. (Citation2018), and Soliman (CitationForthcoming).

2. This program was established by the Dutch Knowledge Network on Systems Innovation and Transition (KSI) at the Dutch Research Institute for Transitions (Drift), Netherland (Grin et al. Citation2010). Also, the Sustainability Transitions Research Network (STRN) was inaugurated in 2009 at the 1st European Conference on Sustainability Transitions in Amsterdam to create a new inter-disciplinary academic community (Koehler et al. Citation2017). The STRN became a core network to attract contributors to the development of sustainability transition studies.

References

- Ababsa M. 2012. Public policies toward informal settlements in Jordan. In: Ababsa, M., Dupret, B.,Denis, E., editors. Popular housing and urban land tenure in the Middle East: Case Studies from Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press; p. 259–282.

- Abrams C. 1964. Man’s struggle for shelter in an urbanizing world. Cambridge (Mass): MITT Press.

- Adler P, Kwon S. 2002. Social capital respective or a new concept. Acad Manage Rev. 27(1):17–40.

- Al Sayyad N. 2004. Urban Informality as a ‘New’ way of life. In: Roy A, Al Sayyad N, editors. Urban informality: transnational perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia. Lanham (USA): Lexington Books; p. 7–30.

- Alexander C, Silverstein, M, Angel, S, Ishikawa, S, Denny Abrams, D. 1975. The Oregon Experiment. California (USA): The Center for Environmental Structure.

- Arts B, Van Tatenhove J. 2004. Policy and power. A conceptual framework between the ”oldß and newß” policy idioms. Policy Sci. 37(3–4):339–356.

- Avelino F, Grin J, Jhagroe S, Pell B. 2016. Beyond deconstruction, a reconstructive perspective on sustainability transitions governance. Environ Innovation Societal Transitions. 22:15–25.

- Bai X, McAllister R, Beatty R, Taylor B. 2010. Urban policy and governance in a global environment: complex systems, scale mismatches and public participation. Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. 2:1–7.

- Bourdieu P. 1977. Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bredenoord J, Lindert PV, Smets P, eds. 2014. Affordable housing in the urban global south: seeking sustainable solutions. Oxon (UK): Routledge.

- Bromley R. 1979. The urban informal sector: critical perspectives on employment and housing policies. Headington Hill Hall, UK: Pergamon Press Ltd.

- Bromley R. 2004. Power, property and poverty: why De Soto’s mystery of capital cannot be solved. In: Al Sayyad N, Roy A, editors. Urban informality: transnational perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia. Lanham (USA): Lexington Books; p. 271–288.

- Byrne R. 2009. Learning drivers: rural electrification regime building in Kenya and Tanzania [PhD Thesis SPRU]. University of Sussex, UK: Science Policy Research Unit.

- Campbell B, Sallis P. 2013. Low-carbon yak cheese: transition to biogas in a Himalayan socio-technical niche. Interface Focus. 3(1):18–26.

- Castán Broto V. 2016. Innovation territories and energy transitions. Energy, water and modernity in Spain, 1939–1975. J Environ Policy Plan. 18(5):712–729.

- CDR. 2016. Habitat III Lebanese national report. Final Report. Grand Serail, Beirut: Council for Development and Reconstruction,

- Coenen L, Benneworth P, Truffer B. 2012. Toward a spatial perspective on sustainability transitions. Res Policy. 41:968–979.

- Collier P. 2002. Social capital and poverty: a microeconomic perspective. In: Van Bastelaer T, Grootaert C, editors. The role of social capital in development: an empirical assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; p. 19–41.

- d’Alençona PA, Smith H, Álvarez de Andrés E, Cabrera C, Fokdal J, Lombard M, Mazzolini A, Michelutti E, Moretto L, Spire A, et al. 2018. Interrogating informality: conceptualisations, practices and policies in the light of the new urban Agenda. Habitat Int. 75:59–66.

- Davidson F, Payne G. 1985. Urban project manual. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Davis M. 2006. Planet of slums. London: Verso.

- De Soto H. 1989. The other path: the invisible revolution in the third world. London: I.B. Taurus.

- De Soto H. 2000. The mastery of capital: why capitalism triumphs in the west and fails everywhere else. London: Black Swan.

- Dempsey N, Jenks M. 2010. The future of the compact city. Built Environ. 36(1):5–8.

- Denis E. 2012. The commodification of the Ashwa’iyyat: urban land, housing market unification, and de Soto’s interventions in Egypt. In: Ababsa, et al., editor. 2012 popular housing and urban land tenure in the Middle East. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press; p. 227–258.

- Dixon T. 2014. Introduction. In: Dixon T, Eames, M, Hunt M, Lannon S C. Editors. Urban retrofitting for sustainability: mapping the transition to 2050. Abingdon: (Oxon, UK): Routledge; p. 1–s16.

- Edensor E, Jayne M. eds. 2011. Urban theory beyond the West: A world of cities. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Fathy H. 1973. Architecture for the poor: an experiment in rural Egypt. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Fawaz M. 2008. An unusual clique of city-makers: social networks in the production of a neighborhood in Beirut (1950–75). Int J Urban Reg Res. 32.3:565–585.

- Fawaz M. 2009. Neoliberal Urbanity and the right to the city: a view from Beirut’s periphery. Dev Change. 40(5):827–852.

- Frantzeskaki N, Loorbach D. 2012. Governing societal transitions to sustainability. Int J Sustainable Dev. 15(Nos):1/2.

- Gans H. 1962. The urban villager: group and class in the life of Italian-Americans. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe, Inc.

- Gaonkar DP. 2001. Alternative modernities. Durham (NC): Duke University Press.

- Geddes P. 1915. An introduction of the town planning movement and to the study for civics. London: Williams & Norgate.

- Geels F, Schot J. 2010. The dynamics of socio-technical transitions: a sociotechnical perspective. In: Rotmans J, Schot J, Grin J, editors. Transitions to Sustainable Development: new directions in the study of long-term transformative change. New York: Routledge; p. 11–93.

- Geels F. 2014. Regime resistance against low-carbon transitions: introducing politics and power into the multi-level perspective theory. Cult Soc. 31(5):21–40.

- Geels F, Schot J. 2007. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res Policy. 36:399–417.

- Geels FW. 2004. From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Res Policy. 33:897–920.

- Geels FW. 2005. The dynamics of transitions in socio-technical systems: A multi-level analysis of the transition pathway from horse-drawn carriages to automobiles. Technol Anal Strategic Manage. 17(4):445–476.

- Geels FW, Hekkert MP, Jacobsson S. 2008. The dynamics of sustainable innovation journeys. Technol Anal Strategic Manage. 20(5):521–536.

- Geels FW, Kern F, Fuchs G, Hinderer, Nele N, Kungl G, Mylan J, Neukirch M, Wassermann S. 2016. The enactment of socio-technical transition pathways: A reformulated typology and a comparative multi-level analysis of the German and UK low-carbon electricity transitions (1990–2014). Res Policy. 45:896–913.

- Gough I, Wood G, Barrientos A, Bevan P. 2008. Insecurity and welfare regimes in Asia, Africa and Latin America: social policy in development contexts. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Grin J, Loeber A. 2007. Theories of learning. Agency, structure and change. In: Miller GJ, Sidney MS, Fischer F, editors. Handbook of public policy analysis. Theory, politics, and methods. New York: CRC Press; p. 201–222.

- Grin J, Rotmans J, Schot J. 2010. Transitions to sustainable development: new directions in the study of long term transformative change. New York: Routledge.

- Guha-Khasnobis B, Kanbur R, Ostrom E. 2006. Beyond formality and informality. In: Kanbur R, Ostrom E, Guha-Khasnobis B, editors. Linking the formal and informal economy: concepts and policies. Oxford: Oxford University Press; p. 1–18.

- Gunderson LH, Holling CS. 2002. Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Washington (DC): Island Press.

- Hart K. 1973. Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. Mod Afr Stud. 11(1):61–89.

- Harvey D. 1985. The urbanization of capital: studies in the history and theory of capitalist urbanization 2. Oxford (UK): Basil Blackwell Ltd.

- Harvey D. 2016. The ways of the world. London: Profile Books Ltd.

- Hasan A. 2001. Working with communities. Karachi. Pakistan: City Press.

- Hatina M. 2007. Identity politics in the Middle East liberal thought and Islamic challenge in Egypt. London: Tauris Academic Studies.

- Hoffman J. 2013. Theorising power in transition studies: the role creativity in novel practices in structural change. Policy Sci. 46(3):257–275.

- Hoogma R, Kemp R, Schot J, Truffer B. 2002. Experimenting for sustainable transport: the approach of strategic niche management. London: Spon Press.

- International Labor Office. 1972. Employment, Income and Inequality: A strategy for increasing productivity. Geneva:ILO.

- Jenkins P. 2013. Urbanization, Urbanism and Urbanity in an African City: home spaces and house cultures. New York (NY): Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kemp R, Loorbach D, Rotmans J. 2007. Transition management as a model for managing processes of co-evolution towards sustainable development. Int J Sustainable Dev World Ecol. 14:1–15.

- Kemp R, Schot J, Hoogma R. 1998. Regime shifts to sustainability through processes of niche formation: the approach of strategic niche management. Technol Anal Strategic Manage. 10:175–196.

- Koehler J., Geels F. W., Kern F., Onsongo E., Wieczorek A. J. (2017). A research agenda for the sustainability transitions research network. amsterdam, Netherland: STRN. Available online at. STRN. https://transitionsnetwork.org/about-strn/research_

- Köhlera J, Geels FW, Kern F, Markard J, Onsongo E, Wieczorek A, Alkemade F, Avelino F, Bergek A, Boons F, et al. 2019. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: state of the art and future directions. Environ Innovation Societal Transitions. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004.

- Kooiman J. 2003. Governing as Governance. London: SAGE Publications.

- Kreibich V. 2012. The mode of informal urbanization: reconciling social and statutory regulation in urban land management. In: Waibel M, McFarlane C, editors. Urban informalities: reflections on the formal and informal. Surrey (UK): Ashgate; p. 183–194.

- Laguerre MS. 1994. The Informal City. New York: St. Martin’s Press, Inc.

- Lawhon M, Murphy JT. 2012. Socio-technical regimes and sustainability transitions insights from political ecology. Prog Hum Geogr. 36:354–378.

- Lefebvre H. 1971. Everyday life in the modern world. New York: Harper & Row Publishers.

- Lefebvre H. 1991. The production of space. Maiden (USA): Blackwell Publishing.

- Leftwich A. 2010. Redefining politics. People, resources and power. New York (NY): Routledge.

- Lewis O. 1966. Culture of poverty. Sci Am. 215(4):19–25.

- Lewis WA. 1954. Economic development with unlimited supplies of labor. Manchester Sch Econ Soc Stud. 22:139–191.

- Lipton M. 1984. Family, fungibility and formality: rural advantages of informal non-farm enterprise versus the urban-formal state. In: Amin S, editor. Human resources, employment and development, vol. 5: developing countries. London: MacMillan, for International Economic Association; p. 189–242.

- Loorbach D. 2007. Transition Management: new mode of governance for sustainable development. Grifthoek (Utrecht, the Netherlands): International Books.

- Loorbach D. 2010. Transition management for sustainable development: A prescriptive complexity-based governance framework. Governance. 23(1):161–183.

- Loorbach D, Oxenaar S. 2018. Counting on Nature: transitions to a natural capital positive economy by creating an enabling environment for Natural Capital Approaches. Rotterdam: Dutch Research Institute for Transitions (DRIFT) Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

- Loorbach D, Wittmayer JM, Shiroyama H, Fujino J, Mizuguchi S. eds. 2016. Governance of urban sustainability transitions: European and Asian experiences. Japan: Springer Japan.