ABSTRACT

Three different drying processes (smoking, oven-drying and sun-drying) were compared for preparing paprika as an ingredient in Iberian chorizo manufacture. The physical–chemical parameters, microbial counts, colour, oxidative stability and storage of the fermented meat product packaged under vacuum in various commercialisation formats (whole, pieces and slices) were evaluated. In addition, sensory analysis was assessed at both the beginning and end of the storage. The smoked paprika stabilised the colour and preserved the Iberian chorizo against lipid oxidation after processing and during storage, independent of its commercialisation format. On the contrary, the fermented sausages elaborated with oven-dried paprika were highly susceptible to rancidity and colour loss. The sun-dried paprika presented a better aptitude as an ingredient in Iberian chorizo than those that were oven-dried, but the packaged sliced samples were most susceptible to colour degradation and lipid oxidation.

RESUMEN

Para el presente estudio se compararon tres procesos de secado diferentes para preparar el pimentón como ingrediente en la elaboración de chorizo ibérico: ahumado, secado al horno y secado al sol. En varias presentaciones comerciales (enteros, trozos y rodajas), envasadas al vacío, se evaluaron los parámetros físico-químicos, los recuentos microbianos, el color, la estabilidad oxidativa y el almacenamiento del producto cárnico fermentado. Además, se realizó el análisis sensorial tanto al comienzo como al final del almacenamiento. Se constató que después de su procesamiento y durante el almacenamiento el pimentón ahumado estabilizó el color y preservó al chorizo ibérico de la oxidación de lípidos, independientemente de cuál fuera su presentación comercial. Por el contrario, las salchichas fermentadas elaboradas con pimentón secado al horno fueron muy susceptibles a la ranciedad y la pérdida de color. En este sentido, se constató que el pimentón secado al sol resulta más apto como ingrediente del chorizo ibérico que el que se secó al horno; sin embargo, las muestras empaquetadas en rodajas fueron más susceptibles a la degradación de color y a la oxidación de lípidos.

PALABRAS CLAVES:

1. Introduction

Spanish dry-cured sausages (chorizo) are prepared from minced pork meat and represent an important part of the cured meat products produced in Spain. Some sensorial characteristics of chorizo, such as its colour, mainly derive from using paprika as an ingredient, which typically contributes to around 2–3% of the total product (Casquete et al., Citation2012a). Literature studies indicate that colour modifications in chorizo are due principally to the changes that this spice undergoes (Fernández-López, Pérez-Álvarez, Sayas-Barberá, & López-Santoveña, Citation2002). In Extremadura, the south-western area of Spain, Iberian chorizo is a high-value product made from the meat of autochthonous Iberian pigs, produced in an extensive rearing system (Real Decreto 474/Citation2014) that leads to muscle with a high concentration of unsaturated lipids and therefore a high susceptibility to oxidation (Tejeda, Gandemer, Antequera, Viau, & Garcı́a, Citation2002). Considering this aspect and the long curing process (>3 months), the antioxidant capacity of ingredients, such as paprika, becomes critically relevant for improving the oxidative stability of chorizo sausages and for guaranteeing an adequate sensorial quality regarding the product’s colour and rancidity during its storage. Differences in the colour parameters and antioxidant activity of paprika have been related to the drying process. In general, smoked paprika shows high American Spice Trade Association (ASTA) units and pigment concentrations, as well as a better colour stability and antioxidant activity than sun-dried and oven-dried paprika (Velázquez et al., Citation2014). A high amount of volatile phenolic compounds in smoked paprika have been described as responsible for its high antioxidant capacity and desirable aroma, rendering it useful as an ingredient in the food industry (Martín et al., Citation2017).

Conversely, the susceptibility of cured meat products to lipid oxidation during their storage also depends on prooxidant factors, such as the presence of oxygen. Modern food packaging, such as vacuum packaging, is being increasingly used to extend the storage of cured meat products, for distribution and retail sale. Several studies has been conducted to determine the effect of vacuum packaging on the preservation of dry-cured meat products. The colour and lipid oxidation stability of salchichón (a Spanish dry-cured sausage elaborated without paprika) enriched with mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids presented minor alterations after chilled storage under vacuum for 210 days (Rubio, Martínez, García-Cachán, Rovira, & Jaime, Citation2008). Similar findings were reported by Ansorena and Astiasaran (Citation2004) when combined vacuum packaging, olive oil and antioxidants for extending shelf-life of different formats of dry fermented sausages. Therefore, this packaging method can allow increases in the storage of Iberian chorizo, by preserving its sensorial quality under attractive but otherwise typically unstable commercialisation formats, such as sliced product.

The aim of this work was to assess the influence of the drying method on the aptitude of paprika as an ingredient in Iberian chorizo manufacture. The colour and oxidative stability of chorizo batches elaborated with paprika (smoked, oven-dried and sun-dried) and VP in various commercialisation formats were evaluated.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Plant material

Non-pungent paprika (Capsicum annuum L.) was used in the present work and grouped into three batches according to the drying method: smoked, oven-dried and sun-dried. Five different brands of each type of paprika were purchased in cans at local markets, within <2 months from the date of packaging. Smoked paprikas were elaborated according to Protected Designation of Origen ‘Pimentón de La Vera’ (Council Regulation (EC) No 510/Citation2006). Peppers were smoke-dried with oak logs for 15 days in a traditional dryer. Oven-dried paprikas belonged to Spanish producers, and were air-dried in an industrial dryer. While sun-dried paprikas were imported products, which were dried by sun during 12–15 days. Samples were kept under dry conditions before laboratory analysis within 1–2 days after opening. All samples of each type of paprika were properly mixed in same proportion before analysing and using as ingredient. lists the mean values of quality parameters (determined as Velázquez et al. (Citation2014)) of the three types of paprika used.

Table 1. Quality parameters of the three types of paprika used in elaborating Iberian chorizo.

Tabla 1. Parámetros de calidad de los tres tipos de pimentón utilizados en la elaboración del chorizo ibérico.

2.2. Preparation of dry-fermented sausages

Iberian chorizos were prepared and fermented in the pilot plant of the School of Agricultural Engineering (University of Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain). Three batches of this fermented meat product were elaborated with a different type of paprika, correspondingly coded smoked (Sm), oven-dried (Ov) and sun-dried (Su). The mixture (without starter culture) was prepared using the following composition: 67.5% Iberian pork, 32.5% Iberian pork fat, 30 g/kg paprika, 20 g/kg garlic and 23 g/kg NaCl. The mixture was kept at 5–10ºC for 24 h and stuffed. Afterwards, the sausages were fermented at 5 ºC and 90% relative humidity (RH) for 1 day. Then, the temperature and RH were modified to 4–7 ºC and 80%, respectively, for 4 days. For the next 8 days, the temperature was raised to 8ºC, and RH decreased to 75%. Finally, the sausages were kept at 8–12ºC and 75% RH to reach 120 days of ripening. Sixty units per paprika batch (a total of 180 units) were manufactured. Five sausages of each batch were taken at the beginning (day 18), middle (day 60) and end of ripening (day 120) for physicochemical, microbiological, colour and oxidative stability determinations.

2.3. Packaging of fermented sausages for shelf-life analysis

The remaining 45 units per batch, fully ripened (120 days), were used for shelf-life analysis. Fifteen sausages of each batch were vacuum packaged (VP) in three different commercialisation formats: whole (W), 10 cm length pieces (P) and 1 mm thick slices (S), and were stored under refrigeration with uninterrupted artificial light for 60 days. During this time, five samples were analysed at the beginning (day 7), middle (day 30) and end of storage (day 60), to perform physicochemical, microbiological, instrumental colour and lipid oxidation analyses. In addition, sensory analysis was performed for initial (day 7) and final (day 60) samples.

2.4. Physicochemical parameters

Weight losses were calculated as percentages of raw sausage weight after 48 days of fermentation and ripening. Moisture was determined by oven drying the sample at 100 to 105ºC until constant weight8. Water activity (aw) was measured at 25ºC using a Novasina TH-500 electrolytic hygrometer (Axair Ltd., Pfäffikon, Switzerland). The pH was measured using a Crison model 2002 pH meter (Crison Instruments, Barcelona, Spain).

2.5. Microbiological analysis

For the microbial counts, 10 g of sample was homogenised aseptically for 1 min with 90 mL of 0.1% peptone saline water in a Stomacher 400 (Seward Lab, UAC House, London, UK). It was serially diluted 10-fold in the same diluent and plated onto appropriate plates. The total aerobic mesophilic bacteria count (TAC) was determined on plate count agar (Scharlab, Spain) at 30ºC for 72 h. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were counted on specific Lactobacillus medium (LAMVAB, Scharlab, Spain), prepared according to Hartemink, Domenech, and Rombouts (Citation1997), incubated at 37ºC for 48 h under 5% CO2. Enterobacteriaceae were determined on violet red bile glucose agar (Scharlab, Spain) after incubation at 37ºC for 24 h. Gram-positive catalase-positive cocci (GPCPC) were enumerated on mannitol salt agar (Scharlab, Spain) after incubation at 30ºC for 48 h. Yeasts and moulds were enumerated on acidified (10% v/v tartaric acid) potato dextrose agar (Scharlab, Spain) after incubation at 25ºC for 5 days.

2.6. Colour determination

The surface colour of the sausage samples was measured as reflected colour in the CIELAB (L*, a*, b*) colour space. A Minolta chromameter (Minolta Camera Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) equipped with a CR-300 measuring head, was standardised against a white tile (L* = 97.26, a* = 0.08 and b* = 1.81). The colour coordinates, L* (darkness/whiteness), a* (greenness/redness) and b* (blueness/yellowness) were directly recorded in triplicate on each sample. Each value was the mean of five measures.

2.7. Oxidative stability

The oxidative stability of the sausages during the processing and storage was evaluated by the thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) index, which involved incubation of the sample in boiling water at 100°C for 40 min and final spectrophotometric absorbance measurements at 532 and 600 nm, as described by Sørensen and Jørgensen (Citation1996). Before spectrophotometric measured of the samples, a blank sample processed without addition of TBA were used for zeroing the absorbance. Results were expressed as mg malondialdehyde (MDA) per kilogram of meat product.

In addition, the hexanal concentration was determined in the sausages during the storage, by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Agilent 6890 GC/5973 MS system; Agilent Technologies, CA, USA), using a 5% phenyl/95% polydimethylsiloxane column (30 m × 0.32 mm inner diameter, 1.05 μm film thickness; Agilent), after volatile compound extraction by solid phase micro-extraction (Serradilla et al., Citation2012). The identity of hexanal was confirmed by a comparison of the retention time and mass spectra obtained from chromatographic runs of the pure compound performed with the same equipment and under the same conditions. Quantitative data (expressed as arbitrary area units (AAU)) were obtained from the total ion current chromatograms, by integration of the gas chromatography peak area.

2.8. Sensory analysis

Fifteen judges (eight male and 7 female; 25–45 years old) were selected and trained under ISO standards (ISO 8586-1, Citation1993; ISO 8586-2, Citation2008) for assessing samples of Iberian dry-fermented sausages. For appraising the end of storage samples, a quantitative descriptive analysis was used by the trained panel judges (Casquete et al., Citation2011; Martín et al., Citation2017; Ruiz-Moyano et al., Citation2011) to evaluate differences in visual (redness intensity) and aroma attributes (aroma intensity, cured aroma, rancidity, paprika aroma). For this, the sausages were cut to approximately 0.2-cm thick. Samples were 3-digit coded, and the serving order was established by random permutation. Two panel-replicates were carried out for each sample. The response to each indicator was determined as the mean value of the panellist’s responses. An additional hedonistic test was performed, with an untrained panel of 60 judges that evaluated the overall acceptability of samples at the end of their storage, using a 0–10-point scale.

2.9. Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analysed using SPSS for Windows version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). For each condition (combination of processing time and type of paprika during Iberian sausage manufacture; and combination of storage time, type of paprika, and VP commercialisation formats during the storage), the mean values of all studied parameters were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and separated by Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (P≤ 0.05).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Changes during the manufacture of Iberian chorizo

3.1.1. General physicochemical parameters

reveals the physicochemical changes that occurred during the chorizo manufacturing process. Ripening time had a significant effect (P < .010) on weight loss and aw. During the 120 days of ripening, the weight and aw decreased due to moisture loss, with no significant effect of the type of paprika used in preparing the Iberian chorizos on these parameters. Both, weight losses of around 25% and aw values close to 0.75, have been previously described in fully-ripened Iberian chorizo (Casquete et al., Citation2012a). Likewise, the production of lactic acid as a result of carbohydrate degradation during fermentation by LAB led to a slight decrease in pH (). In the fully-ripened sausages, the pH values ranged from 5.75 (Su) to 6.45 (Sm), which lie within the range expected for sausages with a long ripening period at relatively low temperature, such as Iberian chorizo (Casquete et al., Citation2012a, Citation2012b).

Table 2. Physicochemical parameters and microbial counts of the Iberian chorizo batches during ripening.

Tabla 2. Parámetros fisicoquímicos y recuentos microbianos de los lotes de chorizo ibérico durante la maduración.

3.1.2. Microbial counts

shows microbial counts throughout ripening process. Although some statistical differences were found, the levels of the different microbial groups were those described in the literature for Chorizo (Casquete et al., Citation2012b; Fontán, Lorenzo, Martínez, Franco, & Carballo, Citation2007a; Fontán, Lorenzo, Parada, Franco, & Carballo, Citation2007b). Among the samples, the higher TAC in batch Su could be associated with the higher LAB counts in this batch at the end of the ripening process and may explain, at last partially, its significantly lower pH value (). On the contrary, batch Sm presented the highest GPCPC and yeast counts, the lowest LAB counts and highest pH values.

The Enterobacteriaceae levels evidence an improbable hygienic quality of the raw and manufactured material. Although initial values significantly higher than 5 CFU g−1 were observed for the three batches, the counts of this microbial group in all fully-ripened batches were lower than the limit of detection (2 CFU g−1). The evolution of these microorganisms during ripening corroborates the results found by other authors for chorizo manufactured without starter cultures and the counts are within the wide range of Enterobacteriaceae counts reported in the literature for various dry-cured sausages (Fontán et al., Citation2007a, Citation2007b; González & Díez, Citation2002).

3.1.3. Colour stability

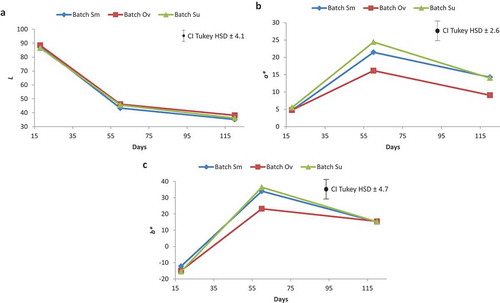

shows the variation in the CIELAB space coordinates of the chorizo batches during the manufacturing process. The results indicated that ripening time significantly affected the three colour parameters studied. The moisture loss during ripening time is related to the lightness (L*) decrease in all batches (Martín-Sánchez et al., Citation2014), whereas redness (a*) and yellowness (b*) values increased until midway through ripening and then slightly decreased at the end of ripening. A similar evolution for this coordinate (i.e. a*) has been described during the storage of fresh chorizo elaborated with paprika that differed in their initial ASTA units (Gómez, Alvarez-Orti, & Pardo, Citation2008).

Figure 1. Evolution of the CIELAB space coordinates during manufacture of the smoked (Sm), oven-dried (Ov) and sun-dried (Su) batches of Iberian chorizo.

Figura 1. Evolución de las coordenadas espaciales de CIELAB durante la producción de los lotes de chorizo ibérico ahumado (Sm), secado al horno (Ov) y secado al sol (Su).

The type of paprika was responsible for the differences in the redness (a*) between batches, evidenced midway and at the end of the ripening process with values of 21.4 (Sm), 24.4 (Su) and 16.1 (Ov) at 60 days of ripening. Mínguez-Mosquera, Jarén-Galán, and Garrido-Fernandez (Citation1994) demonstrated differences on carotenoids content of paprikas based on method of drying. This work proved the higher preservation of the colour components of smoking than oven drying method. Sausages produced from oven-dried paprika showed a lower redness intensity (maximum of 5 units less) than those recorded in the other two batches. According to the ASTA data of the paprika batches (), an initial lower carotenoids content in oven-dried paprika could partially explain the differences in the redness intensity between oven-dried and smoked batches (Gómez et al., Citation2008). However, this argument is not valid for justifying the results obtained for the sun-dried batch. Instead, the relatively lower a* values in the oven-dried batch might be mainly due to a greater susceptibility of these samples to carotenoid degradation, leading to some colour loss (Mínguez-Mosquera et al., Citation1994). Velázquez et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated lower colour stability and higher percentage loss of the carotenoids for oven-dried paprika relative to sun-dried and smoked paprika when exposed to ultraviolet light. These authors also observed a higher 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical-scavenging capacity in the smoked samples than both oven-dried and sun-dried paprika, which influenced the evolution of the lipid oxidation in the Iberian chorizo batches.

3.1.4. Lipid oxidation markers

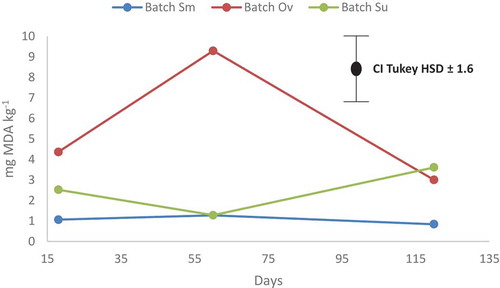

illustrates the lipid oxidation (TBARS) during the manufacture of the Iberian chorizo batches. During the ripening process, no differences occurred in the TBARS values between the Iberian chorizo elaborated with sun-dried and smoked paprika. However, samples developed with oven-dried paprika were initially less protected against lipid oxidation (4.4 mg MDA kg−1), showing an increased MDA content during the first 60 days of processing (9.2 mg MDA kg−1), which then decreased in the final product to values near those detected in the other two batches. The decrease of TBARS values in batch Ov may be a result of the reaction of MDA with amino acids, sugars and other compounds in the formulation (Kolakowska & Deutry, Citation1983).

Figure 2. Evolution of the thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) index during manufacture of the smoked (Sm), oven-dried (Ov) and sun-dried (Sn) batches of Iberian chorizo.

Figura 2. Evolución del índice de sustancias reactivas al ácido tiobarbitúrico (TBARS) durante la producción de los lotes de chorizo ibérico ahumado (Sm), secado al horno (Ov) y secado al sol (Sn).

3.2. Quality changes in VP commercialisation formats of Iberian chorizo during its storage

3.2.1. General physicochemical parameters

No differences (P> .05) in the moisture contents were found between sausage batches during the storage, with values ranging from 15.2 to 19.1% (). These percentages can be considered normal for Iberian chorizo (Casquete et al., Citation2012b). Likewise, although differences in the aw values were recorded among the three batches of Iberian chorizo and for the different commercial formats during the storage, all samples were within the expected values for this meat product (Martín, Colín, Aranda, Benito, & Córdoba, Citation2007). The pH values of VP sausages at the first week of storage concurred with those observed in the final processing stage (), with lower pH values measured in the batches elaborated with sun-dried paprika (). After storage for 60 days, the pH value of the P-Sm batch had increased, whereas the batches W-Ov and P-Ov showed noticeable pH decreases. The main metabolite responsible for the acidification of fermented sausages is lactic acid, although others are also present, such as acetic acid and fatty acids (Bello & Sánchez-Fuertes, Citation1997). An increase in the fatty acid contents, associated with the high lipolytic activity in the oven-dried paprika batches, could explain its low pH values.

Table 3. Physicochemical parameters of the Iberian chorizo batches during storage.

Tabla 3. Parámetros fisicoquímicos de los lotes de chorizo ibérico durante el almacenamiento.

3.2.2. Microbial counts

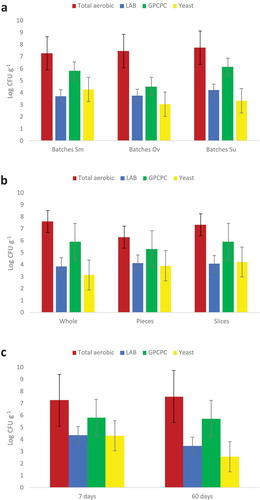

At 14 days of storage, the LAB counts of Iberian sausages decreased (P< .050), in general, more than 2 log CFU g−1 when compared with that during the final ripening of the sausages, and, like the yeast counts, continued to decrease throughout the storage (). Zdolec et al. (Citation2008) also described a decline in the LAB counts during storage (4ºC, 90 days) of sliced VP sausages, with a simultaneous increase in the total viable counts. In our study, the GPCPC counts rose during the first 7 days of storage until near 6 CFU g−1 and then remained stable until the end of storage.

Figure 3. Microbial counts of the Iberian chorizo during storage according to type of paprika (a), commercial format (b) and days of storage (c). Error bars indicate the IC Tukey HSD for each microbial group.

Figura 3. Recuentos microbianos del chorizo ibérico durante el almacenamiento según el tipo de pimentón (a), formato comercial (b) y días de almacenamiento (c). Las barras de error indican el resultado de la prueba IC Tukey HSD para cada grupo microbiano.

In contrast, there were no differences in the mean counts of the studied microbial groups during the storage of the VP products regarding the “commercial format” and only minor variations concerning the factor “paprika type” (). Consequently, any relevant influence of the microbial evolution on the changes in colour stability and lipid oxidation during the storage of the VP products was discarded.

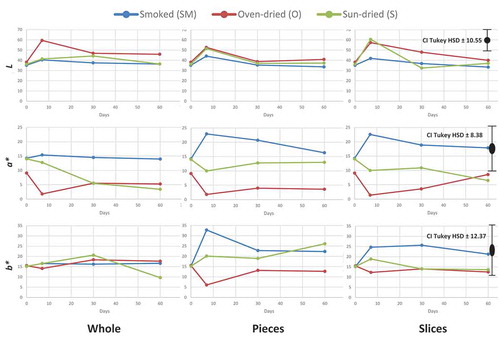

3.2.3. Colour stability

depicts the colour parameters during the storage. No marked effect on L* was observed during storage irrespective of the paprika type used (Sm, Ov and Su) and the packaging method (W, P and S). For coordinate a*, however, batches elaborated with smoked paprika (W-Sm, P-Sm, and S-Sm) presented high colour stability, showing the maximum (P< .05) a* values at the end of the storage (). For the Iberian chorizo manufactured with sun-dried paprika, a* decreased during the storage of batches W-Su and P-Su but rapidly declined in all those elaborated with oven-dried paprika (W-Ov, P-Ov and S-Ov), at 7 days of storage, confirming the low colour stability of this type of paprika (Velázquez et al., Citation2014). A final increase of a* value in batch S-Ov was observed, in concordance with the behaviour reported by Pateiro, Bermúdez, Lorenzo, and Franco (Citation2015) for this colour parameter in VP Spanish chorizo. For colour coordinate b*, no significant differences were determined during storage, due to its high intra-sample variability, showing a similar tendency to a* for P and S batches.

Figure 4. Evolution of the CIELAB space coordinates during storage of the smoked (Sm), oven-dried (Ov), and sun-dried (Su) batches of Iberian chorizo vacuum-packaged in different commercial formats: whole (W), pieces (P), and slices (S).

Figura 4. Evolución de las coordenadas del espacio CIELAB durante el almacenamiento de los lotes de chorizo ibérico ahumado (Sm), secado al horno (Ov) y secado al sol (Su) en diferentes presentaciones comerciales: enteros (W), trozos (P) y rodajas (S).

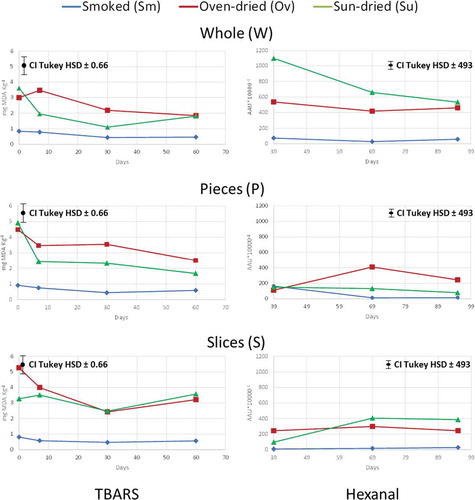

3.2.4. Lipid oxidation markers

In order to determine how the oxidative process of the Iberian chorizo was affected during storage by the three different paprika types and the three different commercial formats, TBARS and hexanal levels were evaluated (). The paprika type significantly affected (P < .05) both indicators, but demonstrated less lipid oxidation of the batches elaborated with smoked paprika (Sm) than the other batches, with <1 mg MDA kg−1. These findings agree with the increased antioxidant activity that smoked-drying confers to paprikas associated to volatile phenols such as guaiacol and 3-ethylpehnol among others (Velázquez et al., Citation2014). In addition, several works highlight the high antioxidant activity of the lignin related phenolic compounds guaiacol and its derivates (Dizhbite, Telysheva, Jurkjane, & Viesturs, Citation2004; El-Giar & Steele, Citation2016; Lee, Lee, Takeoka, Kim, & Park, Citation2005), which corroborate the role of the phenolic compounds associated to smoke in the increase of antioxidant activity of smoked paprika.

Figure 5. Evolution of the thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) index and hexanal during storage of the smoked (Sm), oven-dried (Ov) and sun-dried (Su) batches of Iberian chorizo vacuum-packaged in different commercial formats: whole (W), pieces (P) and slices (S).

Figura 5. Evolución del índice de sustancias reactivas al ácido tiobarbitúrico (TBARS) y al hexanal durante el almacenamiento de lotes ahumados (Sm), secados al horno (Ov) y secados al sol (Su) de chorizo ibérico envasados al vacío en diferentes presentaciones comerciales: entero (W), trozos (P) y rodajas (S).

Considering the commercial formats (S, W and P), differences in both lipid oxidation markers were found between the sausages elaborated with sun-dried (Su) and oven-dried (Ov) paprika on the final day of storage. Sausages in S format presented more than 3 mg MDA kg−1, whereas less than 2 mg MDA kg−1 was detected in W format. The TBARS values were higher those found by other authors in olive oil containing sausages with rancid notes (Bloukas, Paneras, & Fournitzis, Citation1997). On the contrary, higher hexanal concentration for W versus S commercial format was noted, confirming the low reliability of these parameters for precise quantification of secondary oxidative degradation in Iberian chorizo. For these reasons, both TBARS and hexanal determination may only be useful to assess the general extent of lipid oxidation in ripened meat-based products (Ross & Smith, Citation2006).

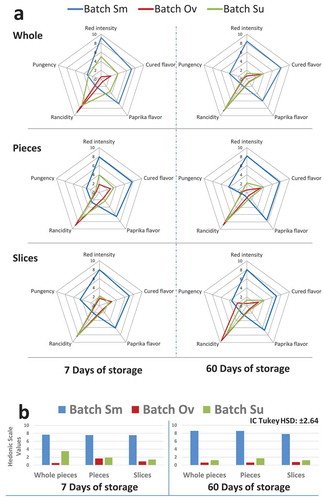

3.2.5. Sensory analysis

The sensory analysis data paralleled the behaviour of the colour parameters and lipid oxidation in the three batches during storage (). The sausages elaborated with smoke paprika (Sm) presented excellent storage stability, exhibiting the highest scores for the positive attributes of red intensity, cured and paprika flavours and overall acceptability, and without relevant differences among the commercial formats. In contrast, the Iberian sausages made with oven-dried paprika (Ov) scored the least for these attributes and the highest for rancidity, even at the beginning of storage (7 days). Differences during storage were only found for the sausages elaborated with sun-dried paprika (Su), suggesting a certain effect on colour stability and lipid oxidation delay. For these samples, the W-Su batches received low scores for positive attributes (colour, paprika flavour and overall acceptability) and scored highly for rancidity after storage for 60 days. At the end of storage, sun-dried paprika batches (Su) had a similar sensory profile to the oven-dried paprika batches (Ov), with a noticeable colour alteration and intense lipid oxidation, accompanied by strong rancidity.

Figure 6. Values of the sensory descriptors (a) and acceptability (b) of the vacuum-packaged Iberian chorizo of smoked (Sm), oven-dried (Ov), and sun-dried (Su) batches in different commercial formats: whole (W), pieces (P), and slices (S) at 7 and 60 days of storage. IC Tukey HSD: red intensity (±2.46); cured flavour (±3.83); paprika flavour (±4.01); rancidity (±2.76); pungency (±8.30); acceptability (±2.64).

Figura 6. Valores de los descriptores sensoriales (A) y aceptabilidad (B) del chorizo ibérico envasado al vacío de lotes ahumados (Sm), secados al horno (Ov) y secados al sol (Su) en diferentes presentaciones comerciales: enteros (W), trozos (P) y rodajas (S) a los 7 y 60 días de almacenamiento. Resultados de la prueba IC Tukey HSD: intensidad roja (± 2.46); sabor a curado (± 3.83); sabor a pimentón (± 4.01); rancidez (± 2.76); acritud (± 8.30); aceptabilidad (± 2.64).

4. Conclusion

The drying process of the paprika used for Iberian chorizo manufacture plays a critical role in the quality of this meat product. The smoked paprika stabilised the colour and preserved the Iberian chorizo from lipid oxidation throughout the processing and storage, independent of the commercialisation format. In contrast, the fermented sausages elaborated with oven-dried paprika were highly susceptible to rancidity and colour loss. The sun-dried paprika presented a better aptitude than those that were oven-dried and revealed the samples packaged in S format were most susceptible to colour degradation and lipid oxidation.

Author contributions

Cristina Pereira, Emilio Aranda and Rocio Velázquez contributed on acquisition and analysis of data. Teresa Bartolomé was determinant in the conception of this study. María de Guía Córdoba contributed in the conception and design of this work, so in the final approval of the manuscript. Alejandro Hernández and Alberto Martín have collaborated in the conception and design of the work. They both have interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to M. Cabrero and J. Barneto for technical assistance and the PDO Pimentón de La Vera for technical support. This work has been funded by the projects AGA015 of the Junta de Extremadura and the European Regional Development Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ansorena, D., & Astiasaran, I. (2004). Effect of storage and packaging on fatty acid composition and oxidation in dry fermented sausages made with added olive oil and antioxidants. Meat Science, 67(2), 237–244. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2003.10.011

- Bello, J., & Sánchez-Fuertes, M. A. (1997). Development of mathematical model to describe the acidification occurring during the ripening of dry fermented sausage. Food Chemistry, 59, 101–105. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(96)00203-8

- Bloukas, J. G., Paneras, E. D., & Fournitzis, G. C. (1997). Effect of replacing pork backfat with olive oil on processing and quality characteristics of fermented sausages. Meat Science, 45, 133–144. doi:10.1016/s0309-1740(96)00113-1

- Casquete, R., Benito, M. J., Martín, A., Ruiz-Moyano, S., Aranda, E., & Córdoba, M. G. (2012a). Use of autochthonous Pediococcus acidilactici and Staphylococcus vitulus starter cultures in the production of “chorizo” in 2 different traditional industries. Journal of Food Science, 77, M70–M79. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02461.x

- Casquete, R., Benito, M. J., Martín, A., Ruiz-Moyano, S., Aranda, E., & Córdoba, M. G. (2012b). Microbiological quality of salchichón and chorizo, traditional Iberian dry-fermented sausages from two different industries, inoculated with autochthonous starter cultures. Food Control, 24, 191–198. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.09.026

- Casquete, R., Benito, M. J., Martín, A., Ruiz-Moyano, S., Hernández, A., & Córdoba, M. G. (2011). Effect of autochthonous starter cultures in the production of “salchichón”, a traditional Iberian dry-fermented sausage, with different ripening processes. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 44(7), 1562–1571. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2011.01.028

- Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006 of 20 March 2006 on the protection of geographical indications and designations of origin for agricultural products and foodstuffs.

- Dizhbite, T., Telysheva, G., Jurkjane, V., & Viesturs, U. (2004). Characterization of the radical scavenging activity of lignins––Natural antioxidants. Bioresource Technology, 95(3), 309–317. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2004.02.024

- El-Giar, E. M., & Steele, P. (2016). Evaluation of the antioxidant activities of different bio-oils and their phenolic distilled fractions for wood preservation. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 110, 121–128. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2016.03.015

- Fernández-López, J., Pérez-Álvarez, J. A., Sayas-Barberá, E., & López-Santoveña, F. (2002). Effect of paprika (Capsicum annuum) on color of Spanish-type sausages during the resting stage. Journal of Food Science, 67, 2410–2414. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2002.tb09562.x

- Fontán, M. C. G., Lorenzo, J. M., Martínez, S., Franco, I., & Carballo, J. (2007a). Microbiological characteristics of botillo, a Spanish traditional pork sausage. LWT - Food Science and Technology, 40, 1610–1622. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2006.10.007

- Fontán, M. C. G., Lorenzo, J. M., Parada, A., Franco, I., & Carballo, J. (2007b). Microbiological characteristics of “androlla”, a Spanish traditional pork sausage. Food Microbiology, 24, 52–58. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2006.03.007

- Gómez, R., Alvarez-Orti, M., & Pardo, J. E. (2008). Influence of the paprika type on redness loss in red line meat products. Meat Science, 80, 823–828. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.03.031

- González, B., & Díez, V. (2002). The effect of nitrite and starter culture on microbiological quality of “chorizo”—A Spanish dry cured sausage. Meat Science, 60, 295–298. doi:10.1016/S0309-1740(01)00137-1

- Hartemink, R., Domenech, V. R., & Rombouts, F. M. (1997). LAMVAB—A new selective medium for the isolation of lactobacilli from faeces. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 29(2), 77–84. doi:10.1016/S0167-7012(97)00025-0

- ISO. (1993). ISO 8586-1:1993. Sensory analysis–General guidance for the selection, training and monitoring of assessors. Part 1. Selected assessors. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization.

- ISO. (2008). ISO 8586-2:2008. Sensory analysis–General guidance for the selection, training and monitoring of assessors—Part 2: Expert sensory assessors. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization.

- Kolakowska, A., & Deutry, J. (1983). Some comments on the usefulness of 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA) test for the evaluation of rancidity in frozen fish. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research, 27, 513–518.

- Lee, K. G., Lee, S. E., Takeoka, G. R., Kim, J. H., & Park, B. S. (2005). Antioxidant activity and characterization of volatile constituents of beechwood creosote. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 85(9), 1580–1586. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2156

- Martín, A., Colín, B., Aranda, E., Benito, M. J., & Córdoba, M. G. (2007). Characterization of micrococcaceae isolated from Iberian dry-cured sausages. Meat Science, 75, 696–708. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.10.001

- Martín, A., Hernández, A., Aranda, E., Casquete, R., Velázquez, R., Bartolomé, T., & Córdoba, M. G. (2017). Impact of volatile composition on the sensorial attributes of dried paprikas. Food Research International, 100, 691–697. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2017.07.068

- Martín-Sánchez, A. M., Ciro-Gómez, G., Vilella-Esplá, J., Ben-Abda, J., Pérez-Álvarez, J. A., & Sayas-Barberá, E. (2014). Influence of fresh date palm co-products on the ripening of a paprika added dry-cured sausage model system. Meat Science, 97, 130–136. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.12.005

- Mínguez-Mosquera, M. I., Jarén-Galán, M., & Garrido-Fernandez, J. (1994). Influence of the industrial drying processes of pepper fruits (Capsicum annuum Cv. Bola) for paprika on the carotenoid content. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 42(5), 1190–1193. doi:10.1021/jf00041a026

- Pateiro, M., Bermúdez, R., Lorenzo, J. M., & Franco, D. (2015). Effect of addition of natural antioxidants on the storage of “chorizo”, a Spanish dry-cured sausage. Antioxidants, 4, 42–67. doi:10.3390/antiox4010042

- Real Decreto 474/2014, de 13 de junio, por el que se aprueba la norma de calidad de derivados cárnicos. Retrieved from https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2014/06/13/474

- Ross, C. F., & Smith, D. M. (2006). Use of volatiles as indicators of lipid oxidation in muscle foods. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 5, 18–25. doi:10.1111/crfs.2006.5.issue-1

- Rubio, B., Martínez, B., García-Cachán, M. D., Rovira, J., & Jaime, I. (2008). Effect of the packaging method and the storage time on lipid oxidation and colour stability on dry fermented sausage salchichón manufactured with raw material with a high level of mono and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Meat Science, 80, 1182–1187. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.05.012

- Ruiz-Moyano, S., Martín, A., Benito, M. J., Hernández, A., Casquete, R., & Córdoba, M. G. (2011). Application of Lactobacillus fermentum HL57 and Pediococcus acidilactici SP979 as potential probiotics in the manufacture of traditional Iberian dry-fermented sausages. Food Microbiology, 28(5), 839–847. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2011.01.006

- Serradilla, M. J., Martín, A., Ruiz-Moyano, S., Hernández, A., López-Corrales, M., & Córdoba, M. G. (2012). Physicochemical and sensorial characterisation of four sweet cherry cultivars grown in Jerte Valley (Spain). Food Chemistry, 133(4), 1551–1559. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.02.048

- Sørensen, G., & Jørgensen, S. S. (1996). A critical examination of some experimental variables in the 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA) test for lipid oxidation in meat products. Zeitschrift Für Lebensmittel-Untersuchung Und Forschung, 202(3), 205–210. doi:10.1007/BF01263541

- Tejeda, J. F., Gandemer, G., Antequera, T., Viau, M., & Garcı́a, C. (2002). Lipid traits of muscles as related to genotype and fattening diet in Iberian pigs: Total intramuscular lipids and triacylglycerols. Meat Science, 60, 357–363. doi:10.1016/S0309-1740(01)00143-7

- Velázquez, R., Hernández, A., Martín, A., Aranda, E., Gallardo, G., Bartolomé, T., & Córdoba, M. G. (2014). Quality assessment of commercial paprikas. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 49, 830–839. doi:10.1111/ijfs.12372

- Zdolec, N., Hadžiosmanović, M., Kozačinski, L., Cvrtila, Ž., Filipović, I., Škrivanko, M., & Leskovar, K. (2008). Microbial and physicochemical succession in fermented sausages produced with bacteriocinogenic culture of Lactobacillus sakei and semi-purified bacteriocin mesenterocin Y. Meat Science, 80, 480–487. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.01.012