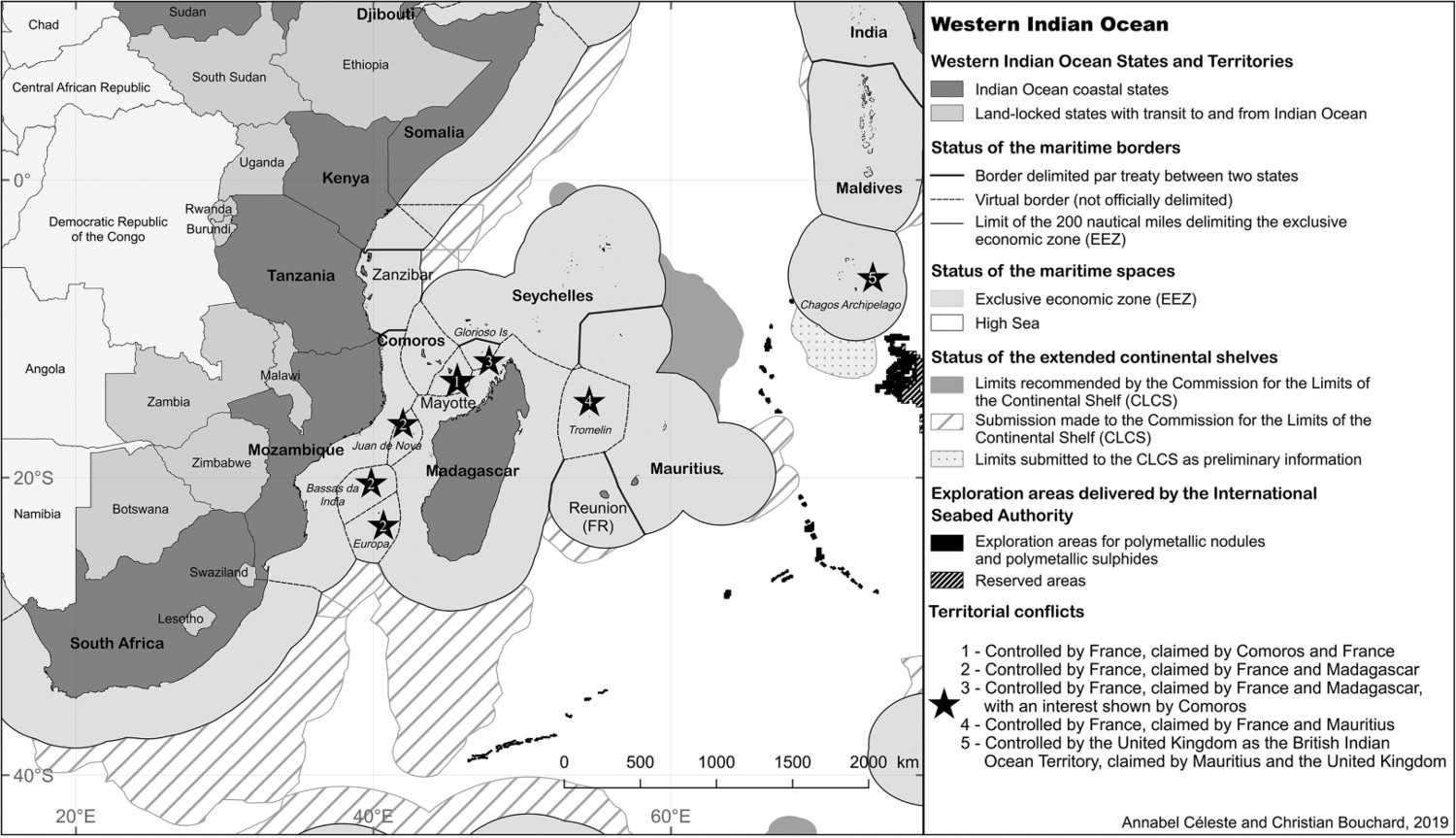

The Southwest Indian Ocean is characterized by the presence of several islands of different size, culture, socio-economic context and political status. Together, they form an original island region that comprised four island states as well as a certain number of non-sovereign territories (see and ). If the island states are easy to identify (Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius and Seychelles), the list of the island territories is subject to debate and varies according to different geographical and political postures and interpretations. In what can be considered as the most common approach, this list includes non-sovereign island territories that are actually subject to territorial disputes between France or the United Kingdom and three of the regional island states, namely MayotteFootnote1, the Scattered IslandsFootnote2, and the Chagos ArchipelagoFootnote3, as well as Reunion over which French sovereignty is not contested by its island states neighbors. A broader geographical approach adds the coastal islands of the African continental states of Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania, especially the Zanzibar Archipelago which is a semi-autonomous region of the United Republic of Tanzania.

Table 1. Basic data for the Southwest Indian Ocean Islands (2017).

Overall, the Southwest Indian Ocean islands form a region of diversity and contrasts, whether it be in terms of political status, territory, population, culture, economy, human development, natural resources or maritime domain (). The diversity is rooted in the specific environmental and human history of each of the island entities, with islands of volcanic, granitic or coralline nature and specific local mixes of settlers from various origins (African, Arabic, Austronesian, European, Indian, and Chinese). The contrast is particularly striking in living standards with Comoros and Madagascar recognized as less developed countries while Seychelles and Mauritius rank first in Africa in terms of human development. As well, diversity and contrasts are also very much founded internally, i.e. inside each island entity, both in terms of environments and population.

Despite the singularity of each of its island states and territories, the region finds some commonalities through the insular nature shared by all of its constituents, a characteristic that is core to the region identity and that differentiate it from continental Africa. The coastal islands apart, the region also singularized itself as a vibrant area of the international Francophonie, which is a legacy of its French colonial history and a testimony of the still significant French footprint in all of these islands (French territories, diplomacy, culture and language, economic relations, military cooperation). Another common trait of the sub-region is the heavy slavery history and heritage which has led to the well-acclaimed Creoleness in the Mascarene Islands, for example. Even if these common traits of insularity and Francophonie are stimulating a common sense of belonging to a unique and coherent island community, the region building process remains relatively weak in terms of political and economic regional integration.

Even though island states are member of several regional organizations (South African Development Community, Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa, African Union, Indian Ocean Rim Association), the backbone of the Southwest Indian Ocean islands’ regionalism is the Indian Ocean CommissionFootnote4 (IOC; in French: Commission de l’océan Indien, COI). The IOC is a concrete manifestation of the islands desire to work together towards a region of peace and co-prosperity, but also a clear manifestation of their incapacity to achieve a deeper and fully inclusive regional integration within its present structure. Created in 1982 and institutionalized in 1984 (Accord général de coopération de Victoria), the Indian Ocean Commission is now recognized by the international community as the regional intergovernmental organization for the Southwest Indian Ocean islands. Its five member-states are Comoros, France/Reunion (France for Reunion), Madagascar, Mauritius and Seychelles. The fact that Reunion is both a French and a European Union territory brings both advantages and challenges to the deepening of the regional integration through the IOC.

The regional integration process is also negatively impacted by the territorial disputes that are another original characteristic of this island region. In the context of the SWIO regionalism, the most significant issue certainly concerns the island of Mayotte who stayed under French sovereignty when the rest of the Comoros Archipelago was granted independence (1976). Since then, Comoros claims Mayotte as an integral part of its national territory, and this has prevented Mayotte to participate to the IOC and its regional cooperation programs. France also kept the tiny islands of Bassas da India, Europa, Juan de Nova, the Glorioso Islands and Tromelin through the decolonization process. Madagascar was granted independence in 1960 and, on the ground that these islands were parts of the Malagasy Republic established in 1958 as an autonomous republic within the newly created French Community, has claimed the islands which are now of great significance in terms of maritime territorialization and of blue economy prospects. Madagascar explicitly claims Bassas da India, Europa, Glorioso Islands and Juan de Nova.Footnote5 Comoros has also shown interest for the Glorioso Islands.Footnote6 Tromelin is claimed by Mauritius on the ground that the island was long listed and recognized as a dependency of the Colony of Mauritius, and that the island was not ceded to France by the Treaty of Paris of 1814 (as was the case for Bourbon Island, now known as Reunion). Finally, prior to the independence of Mauritius (1968), the Chagos Archipelago was separated from the Colony of Mauritius through the British Indian Ocean Territory Order 1965 (an Order in Council). Since its independence, Mauritius claims the Archipelago on the basis that the BIOT creation is a violation by the United Kingdom of United Nations resolutions banning the dismemberment of colonial territories before independence.Footnote7 As fallouts of these territorial disputes, the political map of the region remains somehow uncertain, the maritime boundary delimitation process is stalled, and Mayotte is excluded from the IOC and thus very much isolated from the region-wide cooperation programs. However, Mayotte is also both a French and Union European territory and, as such, is receiving specific European funds for regional cooperation programs, as does Reunion.

Despite the difficulties raised in the regional integration process, a sense of common identity does exist in the Southwest Indian Ocean islands, as well as a strong will to broaden and strengthen the regional cooperation. This special issue comes at a moment when many local and regional leaders speak of 'Indianocéanie' [Indianoceania] to designate this particular island community of the Southwest Indian Ocean. It is a term that is now gaining ground in some political, media and academic circles in the region. With this proposal, the aim is to develop a greater sense of belonging to the region, to encourage solidarity and cooperation between the different island societies, and to advance regional political and economic integration. In addition, this should also contribute to a better recognition and understanding of this original island community by the outside world, especially in the Indian Ocean. But it is still more of a proposition than a reality that needs to be analyzed and debated in order to clarify its contours, content, potentialities, constraints and challenges.

The future will tell us if the term ‘Indianoceania’ will prevail, but in the meantime, it should be noted that this initiative is evoking the existence of a community of destiny in a region aiming for peace, solidarity, security and prosperity. In this context, the term has become central to the Indian Ocean Commission vision and communication. ‘Indianocéanie’ [Indianoceania] derives from the concept of ‘Indianocéanisme’ [Indianoceanism] proposed in 1961 by the Mauritian man of letters Camille de Rauville. Subsequently forgotten, the term ‘Indianocéanie’ has been resumed and put back on the agenda by the Secretary General of the IOC, Mr. Jean Claude de l’Estrac (in office from 2012 to 2016): ‘the use and promotion of the word “Indianocéanie” is not an intellectual coquetry but rather, from our point of view, the expression of an idea and a project’ (de l’Estrac, Citation2013, p. 4). This ambition for an Indianoceania regional identity was further promoted by an IOC Colloquium on the ‘Les mille visages de l’IndianOcéanie’ [The thousands faces of IndianOceania] which was held in Mahébourg, Mauritius (6–7 June 2013). Since that time, the region is embracing the term which seems to percolate and resonate in each of the different island societies.

But the region and the IOC need to find a way to make this Indianoceania fully inclusive and more cohesive in terms of regional integration. For now, there is still a disconnection between the intent and the reality. The unity and coherence of the region will remain weakened until all the island states and territories of the Southwest Indian Ocean are able to participate fully into the regional cooperation agenda. The Mahorais and the ChagossiansFootnote8 peoples are also children of this Indianoceania, and both the Scattered Islands and the Zanzibar Archipelago are integral parts of the Indianocenia geography. Some would even add the Maldives and Sri Lanka as formal constituents of Indianoceania; this question remains however open.

Identity, development and cooperation

The present collection of papers comes as a second Islands Edition for the Journal of the Indian Ocean Region. The first edition, entitled ‘Indian Ocean Islands: Geopolitics, Ocean, Environment’, was published in 2017 (vol. 13, no. 2) and included seven papers that presented material related to Sri Lanka, Cocos and Christmas Islands, the Chagos Archipelago, Mauritius, Seychelles, the islands of the Sundarban Delta, as well as the European Union strategy towards the Indian Ocean islands. The success of this first Islands Edition led us to propose a second edition more focused on the Southwest Indian Ocean islands. The response to this new call for papers has been good, with no less than a dozen of formal proposals. Unfortunately, and for various reasons, only three of these proposals made it to publication, to which was subsequently added a paper submitted in parallel to the call of paper.

Nevertheless, we are happy to have brought this publication project to completion. The final title of this edition differs from the original title of the call for papers which was ‘Southwest Indian Ocean Islands: challenges and opportunities for sustainable development, security and regional cooperation’. An analysis of the submitted manuscripts (published and non-published) has confirmed that these three themes are central to this island region. In all of the manuscripts, we found at least two of the themes discussed, as well as clear links between them. Obviously, the future of this island community reside in achieving sustainable development, security (in all its dimensions, traditional and non-traditional), and regional cooperation.

In this edition on the Southwest Indian Ocean islands, we present papers that address interesting issues pertaining to identity, development and cooperation. In the first paper, ‘Migration from Reunion as a factor in the early development of Seychelles (1770–1903)’, Jehanne-Emmanuelle Monnier presents a story that ‘constitutes a valuable and instructive chapter in trans-imperial and inter-colonial cooperation within the Indian Ocean’. She notes that ‘the promotion of this shared heritage is an asset for regional cooperation today in various ways: cultural, economic, political … ’. In the second paper, ‘Desensitized pasts and Sensational Futures in Mauritius and Zanzibar’, Rosabelle Boswell asserts ‘the relevance of “sensing” identity in cultural analyses of the Southwest Indian Ocean islands’. She concludes ‘that including a sensorial analysis of identity in the Indian Ocean region opens up new avenues for thinking about islanders’ sensorial relations and their identity’.

In the third paper, ‘Energy vulnerability in the Southwest Indian Ocean islands’, Anna Genave uses the concept of energy vulnerability as a framework to assess energy issues in the islands. She proposes an original energy vulnerability index that is specifically adapted for the SWIO islands and proposes that it could be used as a ‘benchmarking tool by “under-performing” islands to duplicate best practices and boost the decision-making process to accelerate energy transition in the region’. Finally, in the fourth and last paper of this special edition, ‘Connected by sea, disconnected by tuna? The challenges of tuna fisheries in the Southwest Indian Ocean regionalism’, Mialy Andriamahefazafy, Christian A. Kull and Liam Campling investigate ‘regionalism through regional identity and collaboration between the countries of the SWIO in tuna fisheries’, especially looking at Madagascar, Mauritius and Seychelles experiences. Their research shows that ‘the “Indianoceania” vision clearly has some way to go before it takes hold within tuna fisheries’, and conclude by proposing ‘pathways for the SWIO region to advance its regional identity and integration in tuna fisheries’.

Overall, all of these four papers are related in some ways to sustainable development, and three of them discuss security issues and regional cooperation. Furthermore, they all tackle some aspects of the regional identity, whether it be historic migrations between the islands and common heritage, regional identity stereotypes, the specific energy context of the islands (disconnected from mainland Africa), or the SWIO tuna fisheries. Obviously, this question of regional identity is blended with the issue of regional integration in the Southwest Indian Ocean islands.

Way forward for the research and publication on the Southwest Indian Ocean islands

There is an obvious need for more research and publications on the Southwest Indian Ocean islands, especially for locally-made research and publications in English. This is not to say that the research actually done and the publications coming out of it are not of good quality. But there is definitively an under-representation in the international academic literature for up to date knowledge on most of the islands and islands societies of the Southwest Indian Ocean. One of the difficulties identified to better reach out to the global audience certainly comes from the need to publish more in English, and the challenges associated with this for researchers that are not English fluent. The other difficulties that we identified was a general need to better develop the conceptual framework of the research, something that is absolutely necessary to deepen the analysis of the research data. It also seems to us that there are a lot of opportunities and needs for collaborative researches done by research teams made by individuals coming from several islands. For us, local and collaborative research is certainly a good tool to promote the Southwest Indian Ocean regionalism, and thus to question and contribute to Indianoceania’s future.

Disclaimer

The contents of this journal are based exclusively on the views of the authors and in no way do these views reflect the views of the IORG Inc., IORAG, IORA, or its member states.

Acknowledgements

The Guest Editors thank all of the authors and reviewers that contributed to this special edition on the Southwest Indian Ocean islands. A special thank also to Annabel Céleste, PhD student at the University of Reunion, for the map reproduced in this introduction. Finally, thanks to Adela Alfonsi, Commissioning Editor of the Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, for her tremendous support throughout this publication project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Christian Bouchard is a full professor at Laurentian University (Ph.D. in geography). His research focusses mainly on the Indian Ocean geopolitics and the Southwest Indian Ocean, with a particular interest for maritime geopolitics and small island states and territories. He is a founding member of the Indian Ocean Research Group (IORG Inc.) and an associate editor for the Journal of the Indian Ocean Region.

Associate Professor Dr Shafick Osman is a research associate at the Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs, Florida International University, Miami (USA). Doctor in Geopolitics (Paris-Sorbonne), Shafick Osman is also a publisher and the Deputy Editor-in-chief of Outre-Terre, European journal of geopolitics. His research interests reside in the Southwest Indian Ocean Islands but also in the Muslim World and the Indian Diaspora.

Dr/HDR Christiane Rafidinarivo is a political scientist specialized on cooperation and comparative analysis. She is Director of research and teaching in geopolitics at the Université de La Réunion and a guest researcher at SCIENCES PO - CEVIPOF UMR 7048 CNRS, Paris. She is President of the Indian Ocean Political Science Association. Her latest publication is on financial cooperation: “Diplomatic crisis and humanitarian diplomacy: who benefits from the bypassing of the state?” (in Fouquet, Thomas and Troit, Virginie, eds, Karthala, 2018).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Actually controlled by France as a French overseas department and region, claimed by the French Republic and the Union of the Comoros.

2. Actually controlled by France as one of the five districts constituting the French Southern and Antarctic Lands. Bassas da India, Europa, Glorioso Islands and Juan de Nova are claimed by the French Republic and the Republic of Madagascar. Comoros has also shown interest for the Glorioso Islands. Tromelin is claimed by the French Republic and the Republic of Mauritius.

3. Actually controlled by the United Kingdom (UK) as the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), the Chagos Archipelago is claimed by Mauritius and the United Kingdom.

4. But this is a highly geopolitical matter as the IOC wanted to be the main vehicle for an Indian Ocean island regionalism, but due to pressure within the IOC itself, the organization has not integrated the other Indian Ocean islands of the area (i.e. Zanzibar, Maldives, Sri Lanka). At the same time, because of the territorial conflict over Mayotte (claimed by Comoros and France), this island of the Comoros Archipelago is excluded from the IOC. Thus the regionalism promoted by the IOC is not fully inclusive and remains partial.

5. On Madagascar’s claim over Bassas da India, Europa, Glorioso Islands and Juan de Nova: UN General Assembly Resolutions 34/91 and 35/123, 1979 and 1980; Oraison, 2011, RJOI no. 14; Oraison, 2016, La revue MCI, no. 72–73; President Hery Rajaonarimampianina’s declaration to the UN General Assembly, 22 September 2016. However, according to some experts, Madagascar never renounced to its 1972 claim on Tromelin (Rafidinarivo, Christiane and Ravaloson, Johary, eds., 2016, La revue MCI, no. 72–73: Dossier spécial Îles Éparses: ‘Regards croisés sur les Îles Éparses, ressources et territoires contestés’).

6. The President of the Islamic Federal Republic of the Comoros, Ahmed Abdallah, expressed his claims during a visit to Paris on January 18, 1980, declaring: ‘The Glorious Islands belong to the Comoros because of their proximity to the Geyser Bank. As soon as we have recovered Mayotte, we will officially claim the Glorious’ (Oraison, 2010, RJOI no. 11, p. 202).

7. Mauritius has brought the sovereignty issue of the Chagos Archipelago to the International Court of Justice in 2017 through a Resolution of the United Nations General Council. The case was heard in 2018.

8. The Chagossians in the Island of Mauritius, Agalega and in the Seychelles do benefit from the IOC activities as they are residents and citizens of Mauritius and of the Seychelles respectively; however, those in Europe are excluded de facto.

References

- CIA. (2018). The world factbook 2018. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

- de l’Estrac, Jean Claude. (2013). “Préface” in Commission de l’océan Indien, Les mille visages de l’IndianOcéanie – Actes du colloque de la Commission de l’océan Indien – Mahébourg, Mauritius, 6 and 7 June 2013, pp. 4–6..

- Sea Around Us [online]. Section: Tools & data. Retrieved from http://www.seaaroundus.org/data/#/eez

- UNDP. (2018). Human development indices and indicators: 2018 statistical update ( p. 112). New York: United Nations Development Programme.