?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The lack of green building and the public’s awareness of the environment is an issue in marketing green apartments in Surabaya, Indonesia. Limited knowledge on green buildings contributes to individuals avoiding risks of purchasing or investing in green apartments. Hence, this study aims to test the effects of green attributes, indoor air quality, accessibility, land attributes, and environmental awareness toward willingness to pay (WTP) for green apartments in Surabaya. This study gathers primary data through the distribution of questionnaires to 390 respondents on green apartments in Surabaya. The data analysis technique used is PLS-SEM. The results showed that green attributes, indoor air quality, land attributes, and environmental awareness significantly influences WTP. Seventy-nine percent of the respondents are willing to pay to own a green apartment for 15% more of the total purchase price, or $670–$6,700. In line with the finding, governments, educational institutions, and property-sector stakeholders need to work together to develop net zero buildings as well as raising green building literacy in the general public to get them to care more for the environment. In a tropical and developing country, the development of green apartments should be adjusted to provide positive benefits to the environment and other sustainable developments.

Introduction

The growth of property has increased the global energy consumption, where buildings consume 40% of the global energy consumption, with residential properties, mainly apartments, accounting for 22%, and commercial property by 18%. It is predicted that by 2040, buildings will contribute to 80% of the global energy consumption (Ramadhiani, Citation2017). The phenomenon mentioned above created the term green building as a solution to the environmental issues as the result of excessive energy consumption and air pollution (Retzlaff, Citation2009). Green buildings are buildings which are designed, constructed, or operated to reduce or remove the negative impact and create a positive impact towards the climate and nature. They preserve precious natural resources and improve quality of life (WGBC, Citation2021).

Apartments are high-rise buildings that consume twice as much energy compared to low-rise buildings (University College London, Citation2017). Energy issues and environmental damage caused by buildings urge governments to issue policies or regulations, such as the Regulation of the Minister of Public Works and Housing No. 02/PRT/M/2015 on Green Buildings (Peraturan Menteri Pekerjaan Umum dan Perumahan Rakyat No. 02/PRT/M/2015 tentang Bangunan Gedung Hijau). This regulation encourages several developers in Surabaya to apply the concept of green building, namely Ciputra Group that built the Green Hill housing complex, and Grand Sungkono Lagoon Surabaya by PT. PP Properti Tbk. that carries green building concepts through a smart home technology system. Developers of green buildings have to consider the demand of the market as the concept is still foreign to the public. One of the deciding factors of successful green building development is the consideration of the user’s expectations and preferences (White & Gatersleben, Citation2011). This preference can be measured by the consumers’ willingness to pay (WTP) for green buildings. WTP is a measurement of the consumer’s willingness to pay in order to consume a product or service (Horowitz & McConnell, Citation2003).

Hu et al. (Citation2014) show that respondents are more willing to pay for green apartments for the accessibility and land attributes factors rather than the green attributes. In contrast, regarding the perception and willingness to pay, hotel users in India are not willing to pay for green attributes products due to the lack of knowledge about the products (Agarwal & Kasliwal, Citation2017). The study on urban sustainability by Heyman and Ståhle (Citation2013) states that the accessibility factor does not have any significant influence. Iman et al. (Citation2012) find that willingness to pay is not affected by land attributes and accessibility in residential property buyers in Malaysia. Moreover, Mandell and Wilhelmsson (Citation2011) state that families in Sweden that have a high environmental awareness are more willing to pay for a housing complex with a green concept. Factors of indoor air quality and green attributes affect WTP for green home in the people in Malaysia, but not on the factor of environmental awareness (Shafiei et al., Citation2013). Indoor air quality is an important factor and significant to predict the WTP for a healthy house attribute in Canada (Spetic et al., Citation2005; Simons et al., Citation2014).

Based on previous studies mentioned above, this study is focused on the factors of green attributes, indoor air quality, accessibility, land attributes, and environmental awareness to measure consumers’ or investors’ willingness to pay for green apartments in Surabaya. Green attributes are green features that a building owns to achieve efficiency and energy conservation, water conservation, as well as sustainable materials sourcing and cycle. Moreover, accessibility take into account the access from the building to facilities, as well as public transports to reduce carbon emissions from transportation. Landscape and green areas in the building that reduce carbon emission is part of the land attributes, while the user’s consideration of the environmental impact from the building is part of environmental awareness.

Surabaya is the second largest city in Indonesia, after its capital Jakarta, with a significant growth in property. The concept of green apartments is considered to be a new thing in Surabaya, so purchases on green apartments are viewed as risky by consumers with a risk-averse behavior. Risk is the uncertainty and consequence of a certain activity and purpose (Sotic & Rajic, Citation2015) and it can affect the willingness to pay. Risk aversion identification can be done by testing the consumer’s rejection of green apartments that poses the risk of consumers having to pay more compared to conventional apartments (Holt & Laury, Citation2002). Farsi (Citation2010) on the study of willingness to pay for an efficient energy system in 264 apartments for rent in Switzerland found that risk aversion behavior plays a role. Consumers have risk-averse behavior because of the uncertain benefits from investing in an energy-efficient system, which then affects the willingness to pay for it.

Studies on green apartments in Indonesia are still limited, and the uncertainty of information on green feature benefits, such as energy conservation, comfort, and others, encourage consumers and investors to exhibit a greater level of risk aversion in owning a green apartment compared to conventional apartment. The aim of this study is to explore the effects of green attributes, indoor air quality, accessibility, land attributes, and environmental awareness toward the willingness to pay for green apartments in Surabaya as well as the role of risk aversion as the moderating variable. The result of this study is expected to be beneficial for the government and property sector practitioners to better understand green buildings. This study may also significantly contribute to the Green Building Council Indonesia.

Literature Review

Utility Theory

Utility is a condition where a property gives benefits, advantages, satisfaction, and pleasure to avoid loss, dissatisfaction, damage, and sorrow to individuals or a community (Bentham, Citation1789). This theory is then developed by Peet and Hartwick (Citation2015) who stated that a property has a utility when the property is able to provide the maximum satisfaction to consumers. Utility theory focuses on the preferences or advantages of an individual. On the practical level, utility theory is used to gauge the consumers’ demands of a product or service (Fishburn, Citation1968). This theory is used by Lovreglio (Citation2016) who stated that an individual will purchase a product that can maximize their gain, where a positive utility counts as a satisfaction, and a negative utility counts as a loss from the result of consuming said product or service. Satisfaction is measured by the preferences or choices of an individual towards his willingness to pay. This concept is developed by Danneberg and Estola (Citation2018) who stated that consumers’ marginal utility is challenging to be measured as there is no tool to directly gauge the level of utility. Hence, willingness to pay is used as a measurement tool through a survey of consumers.

Willingness to Pay

Willingness to pay (WTP) is the consumers’ ability to purchase a product or service (Horowitz & McConnell, Citation2003). Pramastiwi et al. (Citation2011) described WTP as the highest price a consumer is able to pay for a product or service. The concept is used by Biswas and Roy (Citation2016), stating that WTP is an individual’s maximum ability to pay for a service or consume a product. Mandel and Wilhelmsson (Citation2011) measured the WTP of consumers with a utility function, which is the function of benefits and satisfaction of consumers when consuming a product or service. Utility gained by the consumer is reflected in the price he is willing to pay for the product or service. The method used to measure WTP is contingent valuation, which is the gathering of data done through individual preferences survey, frequently known as stated preference (Abelson, Citation1996). Baker and Ruting (Citation2014) state that this survey method is used to estimate the highest value that a consumer will pay for a product. Stated preference is measured by a conjoint analysis survey technique which is the conjoint rating, where respondents’ are asked to assess alternatives offered using a rating scale (e.g. 1 to 10). The questionnaire format used is an open-ended elicitation format, which are open-ended questions given directly to respondents about their maximum number or value they are willing to pay for a product or service. This method causes no early data bias as it offers no initial value.

Green Building

Green Building Council Indonesia (GBCI Citation2019) declared green buildings as new buildings planned and executed to be, or existing buildings, operated with an attention to ecosystems or environmental factors. Several features that deem a building “green” are the efficient use of energy, water, and other resources; the use of renewable energy (solar energy); stages of pollution and waste reduction, and possibilities of reuse and recycle; good indoor air quality; use of materials that are non-toxic, ethical, and sustainable; incorporating the environment in the design, construction, and operation; consideration of the residents’ quality of life in the design, construction, and operation; adapting the design to changing environments (WGBC, Citation2021).

In Indonesia, Green Building Council Indonesia (GBCI) issues a Greenship which is arranged together by the government, academics, industry professionals, and other organizations. Six criteria of green buildings in the Greenship rating system are proper land use, efficiency and conservation of energy, conservation of water, material source and cycle, indoor health and comfort, and building environment management. Based on the six criteria above, five main elements of green buildings can be drawn, which are:

Green Attributes, a green feature a building has to achieve efficiency and energy conservation, water conservation, and sustainable material source and cycle (GBCI, Citation2019; Hu et al., Citation2014)

Indoor Air Quality, an aspect in a building to achieve health and comfort indoors to create a better indoor air quality for the user (GBCI, Citation2019; Simons et al., Citation2014)

Accessibility, which relates to the availability of access and transportation around the building to support reducing carbon emissions, such as the availability of public transport, bike user facility, and community accessibility (GBCI, Citation2019; Hu et al., Citation2014)

Land Attributes, criteria of proper land use, where buildings meet the surrounding site conditions such as green base area, site selection, and landscape accessibility (GBCI, Citation2019; Hu et al., Citation2014).

Environmental Awareness, an awareness of the environment that encourages individuals to develop green buildings further, including having sustainable building management (GBCI, Citation2019; Mandell & Wilhelmsson, Citation2011).

Risk Aversion

Risk aversion, according to Hofstede and Bond (Citation1984), is an individual’s behavior that rejects a product or service as the result of feeling threatened by the uncertainty of the result of purchasing a product or service (Mao, Citation2010). Risk aversion is also an individual’s behavior of rejecting an uncertain investment result to avoid the incompatible result of investment with the expected result (Hagin, Citation2004; Priyadharshini & Muthusamy, Citation2015). The risk-averse group tends to avoid risks or makes decisions involving the smallest risks and is even willing to pay more to get the option with the smallest risk. An individual with a high-risk aversion tends to reject new things such as buying a new product from a lesser-known brand unless he has heard others good experience in buying said product (Bao et al., Citation2003), as quoted in the journal of Quintal et al. (Citation2010). Individuals in the risk-averse group also tend to gather more information on products and services they are interested in using to avoid risks. They tend to do transactions with well-known brands or sellers to avoid any risk in the future.

Willingness to Pay for Green Apartment and Risk Aversion as Moderating Variable

The construction of green apartments cost more than conventional apartments as a result of the materials and technology used. Green apartments are sold with a higher price tag compared to non-green apartments as a price positioning strategy by the developers (Lasalle, Citation2019). Therefore, the existence of green apartments needs extra consideration from the consumers to be willing to pay more for the property. The study of Hu et al. (Citation2014) in Nanjing on three social-economy classes based on domicile considers factors of accessibility, land attributes, and green attributes toward WTP for green apartments using the Stated Preference method. The results showed that accessibility, land attributes, and green attributes proved to be significant, where the increase of willingness to pay caused by accessibility and land attributes is larger than the increase caused by green attributes. Tan (Citation2011) conducted a study on WTP for houses in a sustainable environment in 299 households in Kuala Lumpur and Selangor using land attributes, accessibility, environment, and structural factors. Users are willing to pay 8–31.42% higher to live in a sustainable environment, proving that land attributes and accessibility factors significantly influence WTP. Conversely, Agarwal and Kasliwal (Citation2017) showed the perception of hotel users in India where they were not willing to pay for green attributes as the result of their doubt in the product, as well as Heyman and Ståhle (Citation2013) who showed accessibility was not a significant factor to WTP.

Iman et al. (Citation2012) used conjoint analysis method on land attributes, accessibility, property type, surrounding facilities, design, surrounding environment, price, promotions, and developer’s reputation on residential property buyers’ preferences in Malaysia, and proved that users’ willingness to pay (WTP) is affected by property type, while developer’s reputation, accessibility, and land attributes are not significant towards WTP. Site selection in land attributes results in a higher apartment cost. Households with a higher income chose a bigger property rather than accessibility, as most respondents are already married and have their own method of transport. Mandel and Wilhelmsson (Citation2011) studied 618 families in Sweden regarding WTP for sustainable housing by considering factors such as house attributes, environment, and environmental awareness, where households with high environmental awareness are willing to pay 2–4% more. On the contrary, 817 respondents in Malaysia with an average environmental awareness shows a WTP of less than 5% in buying a green home (Shafiei et al., Citation2013). Simons et al (Citation2014) studied office renters in 17 rented offices regarding the demand and WTP for green features in offices, where the highest WTP is caused by indoor air quality and access to natural lighting. On the other hand, Chau et al. (Citation2010) showed that the people in Hongkong were not willing to pay for indoor air quality factor, reduction of noise level, landscape expansion, and water conservations. Respondents desired energy conservation more because it gives a direct personal gain, while other variables are beneficial for the environment. Likewise, a study in Mumbai finds that green buildings that have a LEED rating are more likely to be motivated to achieve energy efficiency rather than environmental benefits (Verma et al., Citation2020). Previous studies focused more on proving the green building variables that affect WTP; therefore, this study is developed by including the risk profile which is risk aversion, as an individual’s psychological consideration in making decisions. Farsi (Citation2010) studied risk aversion and willingness to pay for an efficient energy system in 264 rented apartments in Switzerland using stated preference method. Risk aversion weakens the WTP for an energy-efficient system. Ignoring risk aversion, apartment users were willing to pay 8.50% more for an energy-efficient system, but risk aversion behavior suppressed WTP to 4.70% for insulation system, and 3.2% for an improved façade. Based on the descriptions above, this study focuses on the effects of green attributes, accessibility, land attributes (Agarwal & Kasliwal, Citation2017; Hu et al., Citation2014; ), indoor air quality (Chau et al., Citation2010; Simons et al., Citation2014), and environmental awareness (Mandell & Wilhelmsson, Citation2011; Shafiei et al., Citation2013) toward the willingness to pay for a green apartment in Surabaya with risk aversion (Farsi, Citation2010) as a moderating variable.

Hypothesis Development

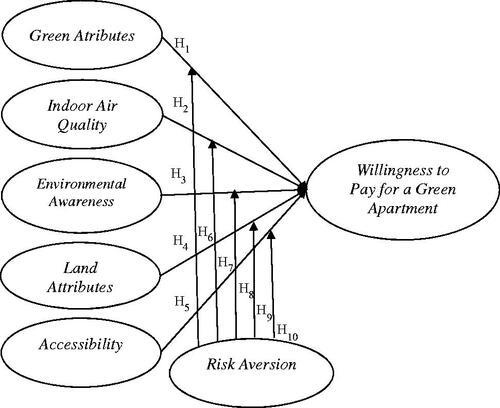

There are 10 hypotheses using the framework of thought in , which are:

H1: Green attributes significantly influences willingness to pay.

H2: Indoor air quality significantly influences willingness to pay.

H3: Accessibility significantly influences willingness to pay.

H4: Land attributes significantly influences willingness to pay.

H5: Environmental awareness significantly influences willingness to pay.

H6: Green attributes significantly influences willingness to pay moderated by risk aversion.

H7: Indoor air quality significantly influences willingness to pay moderated by risk aversion.

H8: Accessibility significantly influences willingness to pay moderated by risk aversion.

H9: Land attributes significantly influence willingness to pay moderated by risk aversion.

H10: Environmental awareness significantly influences willingness to pay moderated by risk aversion.

Research Method

Data were gathered through questionnaires using the stated preference method. The questionnaires consisted of three parts. The first part was designed to gather respondent’s background information, including whether or not having an experience of owning an apartment unit with green features, purpose of purchase, knowledge on green buildings, occupation, and other personal data. In the second part, respondents are asked to rate measurement items on Green Apartment and Risk Aversion. In the third part, respondents are asked to measure their willingness to pay. All items are measured using a 5-point Likert scale (Ekanayake & Ofori, Citation2004) to avoid ambiguous results. shows various 5-point Likert scales adopted from the questionnaire on certain questions. shows the details of the endogenous and exogenous variables as well as the moderating variables in the hypothesis test.

Table 1. Five-point Likert scales used in the questionnaire.

Table 2. Endogenous variable, exogenous variables, and moderating variable.

The population of this study is the general public who live in Surabaya, and samples were gathered using purposive sampling where the respondents are consumers or investors that intend to purchase or invest in apartments, or that have purchased an apartment or a green apartment. Consumers are rational individuals while investors are irrational on their decision-making (Njo et al., Citation2017). Distribution was done online and offline through apartment or house launching events in Surabaya, and meeting property brokers who have a list of prospective property buyers. After data were gathered through the questionnaires, analysis was carried out in two phases: (1) descriptive analysis using cross tabulation to see the frequency data distribution on respondents’ demography toward the purpose and property product, particularly green apartments; (2) testing the hypothesis using PLS-SEM to predict the model and develop the theory. The main function of the graphic modeling of the varians-based structural equation uses the path modeling method, represented by the following equation:

note:

η : Endogenous variable, WTP - Willingness to Pay

γ : Coefficient influence of exogenous variables to endogenous variables

GA : Green Attributes

IQ : Indoor Air Quality

AC : Accessibility

LA : Land Attributes

EA : Environmental Awareness

RA : Risk Aversion

ς : error model

PLS-SEM is able to handle small sample sizes and non-normal data. Measurement and structural model is first determined, followed by the evaluation of reliability and validity of measurement items in the measurement model. To validate the construct, it is vital to evaluate the measurement model as a basis to evaluate, represent, and measure the relationship hypothesized in the structural model, so that the eligibility of the measurement model is verified for path analysis. Reliability measures how well the measurement construct on a multi-item scale reflects accurate scores of the construct relative to error. To evaluate consistent reliability of the measurement item that represents and measures each construct internally, composite reliability score and alpha Cronbach coefficient is used. The composite reliability score and the alpha Cronbach coefficient should be 0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2019) or higher (Nunnally, Citation1978). The reliability assessment is then followed by validity test that includes convergent validity and discriminant validity of the constructs. The convergent validity is considered satisfactory if each of the measurement item has a loading factor of 0.50 or higher, as well as an AVE (average variance extracted) of each construct of 0.50 or higher. AVE is the grand mean value of the squared load of a set of measurement items that is equivalent to the communality of a construct. Discriminant validity is used to test how different each construct is from one another. Two techniques are used in the discriminant validity assessment. The first is according to the criteria of Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) that the variance shared with its measurement item is higher compared to with other construct. In this condition, the AVE of each construct should be more than the highest squared correlation with other construct. The second is the cross-loading assessment of measurement items by verifying the discriminant validity. The loading of each measurement item on each of its construct should be greater than the cross loading on other constructs. After verifying the reliability and validity of the measurement models, the path coefficient significance has to be estimated to test the hypothesis in the structural model using the bootstrapping technique. Bootstrapping is useful in predicting the statistic distribution of any kind of distribution. This study uses 5000 of bootstrap subsamples, and the same number of cases as the number of respondents (which is 390). The use of such a large number of bootstrap subsample is vital to ensure the stability of the result. The critical t-value for a two-sided test is 1.65 (significance level = 10%), 1.96 (significance level = 5%) and 2.58 (significance level = 1%) (Hair et al., Citation2017).

Analysis and Discussion

The result of the questionnaire distribution was 417 respondents, 27 of which were not used as they did not meet the sample criteria, resulting in a final sample of 390 respondents. The respondents’ characteristics are presented in the cross tabulation table to see the respondents’ frequency distribution data according to the purpose of the purchase in .

Table 3. Respondents’ characteristics towards purchase intent.

shows that respondents are more interested in buying apartments for investment purposes (58.205%) instead of residence purposes (41.794%). Males (67.841%) are more interested in making investments compared to females (32.158%). The largest number of respondents who intended to make investments are those in the range of 21–30 years old, married, with the highest education level of a Bachelor’s Degree. Green apartment investors are mostly self-employed (46.696%) with the majority having a gross income of $400–$1,000. There are 83.846% of respondents who have an understanding of green buildings. Both male and female respondents having the understanding are between 21–30 years old (46.177%) and 60.856% has the highest education level of a Bachelor’s Degree.

shows the distribution of respondents’ demography data frequency according to the WTP for green apartments in percentage, in which 40.769% of the respondents are willing to pay ≤5% more of the total price for a green apartment in Surabaya. These respondents are within the range of 21–30 years old, have the highest education level of Diploma and a Bachelor’s Degree, work as private or government employees, with incomes of ≤ $399 and $400–$1,000 per month. Respondents with no apartment ownership, have no understanding of green building, but have consumption motives, are willing to pay less than 5% for a green apartment.

Table 4. Respondents’ characteristic toward willingness to pay in percentage (%).

shows the distribution of respondents’ demography data frequency according to the WTP for green apartments in US$, in which that the majority (58.718%) of respondents are willing to pay $670–$6,700, in the range of 21–30 and 31–40 years old, with the purpose of consumption (as a residential unit).

Table 5. Respondents’ characteristic toward willingness to pay in US$.

shows the respondents’ perception on each indicator of the variable of green apartment. The respondents’ perceptions are shown in the form of mean value on each of the indicators that are used to measure the endogenous and exogenous variables. A higher mean value expresses the respondents’ perception to lean to statements of strongly agree or very important, while a lower mean value expresses the respondents’ perception to lean to statements of strongly disagree or unimportant.

Table 6. Descriptive Analysis of Endogenous and Exogenous Variables.

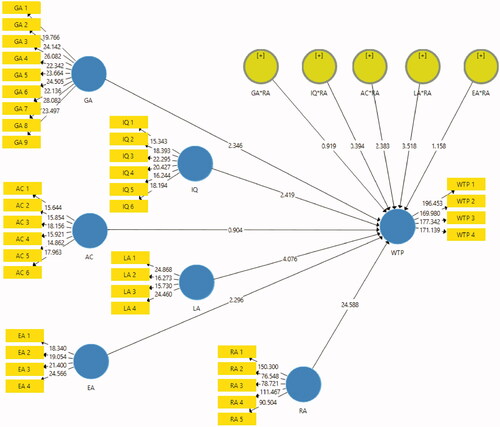

Prior to the hypothesis test, model measurement is done as shown in . Convergent validity shows a loading factor of above 0.70, which is higher than 0.50, so there is no need to delete the item. Should there be an item that does not qualify and needs to be deleted, the analysis is then re-run, and the procedure will be repeated until a reliable and valid measurement model is acquired. This study uses a reflective measurement item because the construct caused that item. Reflective measurement item is highly correlative, interchangeable, and can be eliminated without changing the meaning of the construct (Hair et al., Citation2017). Measurement items with a small loading factor can be deleted as their contribution to the explanatory power of the model is insignificant, making the measurement item bias (Nunnally, Citation1978). The coefficient of Cronbach alpha and the composite reliability score is above 0.70, showing that the internal reliability consistency of the measurement item is acceptable. All loading factors and AVE is above 0.50, proving the convergent validity of the construct. AVE of higher than 0.50 shows that the construct is capable of explaining more than 50% of variants in the measurement item. shows that there are no cross-loading issues, as every measurement item has the highest load on the appropriate construct. This result shows that the measurement model is reliable and valid for the structural path modeling.

Table 7. Measurement model evaluation.

Table 8. Cross loading of measurement items.

Hypothesis test based on the path coefficients value through bootstrapping is listed in as per . This hypothesis is accepted if the critical t-values for a two-tailed test were 1.65 (significance level = 10%), 1.96 (significance level = 5%) and 2.58 (significance level = 1%). The test results showed that H1 (green attributes) and H5 (environmental awareness) directly influence WTP in significance of 5% (t-value > 1.96), H2 (indoor air quality) and H5 (land attributes) directly influence WTP in significance of 1% (t-value > 2.58), while H3 (accessibility) does not significantly influence WTP. The test results, if risk aversion is moderating, show that H8 (accessibility) directly influences WTP in significance of 5% (t-value > 1.96) and H9 (land attributes) directly influences WTP in significance of 1% (t-value > 2.58). The final testing of structural inner model that shows the influences of each variable on the WTP for green apartment () is the value of R-square (0.758). That means the accuracy of the prediction that satisfies the variables can explain willingness to pay by 75.8%. R-square calculation results can be used to calculate Q-square by 0.819, where Q-square value greater than zero means the endogenous variables and moderating variables have a good prediction level towards willingness to pay for green apartments in Surabaya.

Table 9. Structural model evaluation.

Discussion

The purchase of a green apartment made by both consumers and investors shows WTP for green attributes, indoor air quality, land attributes, and environmental awareness as it benefits them. These benefits are viewed as a positive utility (Lovreglio, Citation2016) that leads to the increase of willingness to pay. The presence of green attributes is considered essential because it provides a tangible benefit for the residents, which is in line with the research of Iman et al. (Citation2012), such as motion sensor and sound insulation, to reduce electricity bill, maintain the performance of electronic appliances, and avoid the risk of short electrical current (Putra, Citation2020). The benefit of indoor air quality is the usage of paint with a low level of volatile organic compounds, which gives a direct positive impact on the health and comfort of the residence (the United States Environmental Protection Agency) (EPA, Citation2021). Additionally, land attributes are also considered to be beneficial, although they might not be directly felt by the residents. Indoor gardens and urban structures are also considered to be important in a green apartment for the benefits they give, such as more open space that improves the living quality of the community, cooler indoor air temperature, better air quality, and brings a certain level of comfort to the residents’ lives through a complete city infrastructure. In other words, respondents get both environmental and community benefits. Other researches about willingness to pay done in Nanjing, Malaysia, and the United States also showed that green attributes, indoor air quality, and land attributes significantly influence willingness to pay (Hu et al., Citation2014; Shafiei et al., Citation2013; Simons et al., Citation2014; Tan, Citation2011). Consumers and investors who have an environmental awareness want the development of green buildings with sustainable management of the building environment in their residence in the form of kitchen waste treatment system, use of energy-saving lamps, and waste sorting. The high number of environmental awareness encourages an increased willingness to pay (Fishburn, Citation1968; Stigler, Citation1950) which is in line with the research on sustainable housing in Sweden (Mandell & Wilhelmsson, Citation2011).

Heyman and Ståhle (Citation2013) and Iman et al. (Citation2012) also found that accessibility was not significant to willingness to pay for urban sustainability research and Malaysian residential properties. An increase of willingness to pay occurs when a consumer gains benefits (Stigler, Citation1950). Accessibility, on the other hand, is considered not beneficial and therefore has no significant influence on willingness to pay for a green apartment. This is because most prospective buyers have private transportation in the form of cars or motorcycles and do not want to pay more for access and transportation, bike parking, and public facilities situated within 1500 meters of the building. Furthermore, accessibility gives more benefits to the environment by reducing carbon emissions, so consumers and investors are not willing to pay more since they prefer attributes that provide direct benefits to residents (Iman et al., Citation2012). External factors such as socio-economic factors, clean public transport, air quality, and community culture are also a contributing factor. According to the socio-economic factor, consumers and investors with the gross income of $400–$1,000 belong to the upper-middle socio-economic class, and therefore, rarely use public transport. Additionally, the poor hygiene of public transport, the air quality of Surabaya which tends to be hot and dusty, as well as the lack of a culture of walking, cycling, or using public transport cause consumers to not want to pay more for accessibility. In the long term, accessibility needs to be improved by providing energy-saving public transportations, limiting certain routes so that high-pollution vehicles cannot cross them, providing pedestrian walks and bicycle lanes, as well as parks and greening programs in several spots in Surabaya that are gradually carried out right now. Hopefully, WTP can increase through these activities.

Risk aversion has a significant influence on the relationship between accessibility with willingness to pay and land attributes with willingness to pay. Consumers and investors with higher risk aversion will result in a lower willingness to pay for accessibility factors and land attributes, as accessibility and land attributes may not directly benefit the residents. Lack of information on consumer benefits and experiences related to accessibility and land attributes causes consumers and investors with high risk-aversion to be more likely to reject the product (Bao et al., Citation2003). Farsi (Citation2010) also stated that there is a significant influence of risk aversion moderation where risk aversion significantly reduces the willingness to pay for an efficient energy system. Consumers with high risk-aversion tend to reject a new product unless they know the pleasant experiences of others when purchasing the product (Bao et al., Citation2003). They are very careful about trying new products and they prefer to collect information on green apartments before purchasing the product. Ideally in the future, developers in Surabaya will be able to implement Net Zero Building by optimizing building designs to reduce energy consumption per year to be as low as possible through renewable energy system. Indonesia as a wet tropical country, has the benefit of having two seasons, so that buildings can be designed to prioritize sunlight and fresh air circulation indoors. Costa et al. (Citation2018) emphasize that sustainable building is a challenge because infrastructure costs have historically been higher than development in developed countries. Therefore, green apartment prices can be adjusted to be “friendly” in regards of the construction costs, which will in turn affect willingness to pay. Developers also need to pay attention to consumers’ and investors’ worry of the uncertainty of green products, as those with risk-averse profile tend to reduce their willingness to pay for green apartments that will not benefit them directly.

Conclusion and Recommendation

The questionnaire survey showed that 83.846% of respondents understand green building, where 38.532% are willing to pay ≤ 5% and 39.755% are willing to pay 6%-15% to get a green apartment from the total purchase price. Factors that affect WTP are green attributes, indoor air quality, land attributes, and environmental awareness. However, the role of risk aversion as the moderating variable is proven in the connection between accessibility and land attributes towards willingness to pay for green apartments. Risk-aversion profile on consumers or investors decrease willingness to pay for green apartments.

This study benefits green apartment developers that they may pay more attention to green features that can be enjoyed directly by the consumers or investors. In the long term, the role of educational institution needs to be increased by giving education on the importance of preserving the environment and supporting green buildings and green environment programs since childhood, and practiced in daily life. The government’s part is to create policies to control and direct developers to develop green apartments to reach Net Zero Healthy (NZH). This study is restricted from the limited data of green building in Surabaya in particular, and Indonesia in general, thus needs improvement to support decarbonization efforts in the building sector. Therefore, future studies can improve on the availability of green apartment reinvestment with a sample of consumers or investors who have purchased green apartments and consideration of return of investment according to the investor’s risk profile.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abelson, P. (1996). Project appraisal and valuation of the environment: General principle and six case-studies in developing countries. Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230374744

- Agarwal, S., & Kasliwal, N. (2017). Going green: A study on consumer perception and willingness to pay towards green attributes of hotels. International Journal of Emerging Research in Management and Technology, 6(10), 16–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23956/ijermt.v6i10.63

- Baker, R., & Ruting, B. (2014). Environmental policy analysis: A guide to non-market valuation. Productivity Commission Staff Working Paper. Australia.

- Bao, Y., Zou, K. Z., & Su, C. (2003). Face consciousness and risk aversion: Do they affect consumer decision-making? Psychology and Marketing, 20(8), 733–755. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10094

- Bentham, J. (1789). An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Clarendon Press.

- Biswas, A., & Roy, M. (2016). A study of consumers' willingness to pay for green products. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 4(3), 211–215.

- Chau, C. K., Tse, M. S., & Chung, K. Y. (2010). A choice experiment to estimate the effect of green experience on preferences and willingness-to-pay for green building attributes. Building and Environment, 45(11), 2553–2561. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2010.05.017

- Costa, O., Fuerst, F., Robinson, S. J., & Mendes-Da-Silva, W. (2018). Green label signals in an emerging real estate market. A case study of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Journal of Cleaner Production, 184, 660–670. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.281

- Danneberg, A. A., & Estola, M. (2018). Willingness to pay in the theory of consumer. Hyperion International Journal of Econophysics and New Economy, 11(1), 49–70.

- Ekanayake, L. L., & Ofori, G. (2004). Building waste assessment score: Design-based tool. Building and Environment, 39(7), 851–861. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2004.01.007

- EPA. (2021). 4 13). Indoor Air Quality (IAQ): Addressing indoor environmental concerns during remodelling. United States Environmental Protection Agency: https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/addressing-indoor-environmental-concerns-during-remodeling

- Farsi, M. (2010). Risk aversion and willingness to pay for energy efficient systems in rental apartments. Energy Policy, 38(6), 3078–3088. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.01.048

- Fishburn, P. C. (1968). Utility theory. Management Science, 14(5), 335–378. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.14.5.335

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- GBCI (2019). GREENSHIP. Retrieved December 16, 2019, from Green Building Council Indonesia: https://gbcindonesia.org/greenship

- Hagin, R. L. (2004). Investment management: Portfolio diversification, risk, and timing-fact and fiction. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis. Cengage Learning, EMEA.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM. ) (2nd ed.) SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Heyman, A. V., & Ståhle, A. (2013). Willingness to pay for urban sustainability. In Y. O. Kim, H. T. Park, & K. W. Seo (Eds.), Proceedings of the Ninth International Space Syntax Symposium (pp. 30–43). Sejong University.

- Hofstede, G., & Bond, M. H. (1984). Hofstede's culture dimensions: An independent validation using rokeach's value survey. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 15(4), 417–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002184015004003

- Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/000282802762024700

- Horowitz, J. K., & McConnell, K. E. (2003). Willingness to accept, willingness to pay and the income effect. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 51(4), 537–545. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(02)00216-0

- Hu, H., Geertman, S., & Hooimeijer, P. (2014). The willingness to pay for green apartments: The case of Nanjing, China. Urban Studies, 51(16), 3459–3478. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013516686

- Iman, A. H., Pieng, F. Y., & Gan, C. (2012). A conjoint analysis of buyers’ preferences for residential property. International Real Estate Review, 15(1), 73–105.

- Lasalle, J. (2019). Asia Pacific property digest 2nd quarter-market research and report. Retrieved January 20, 2020, from Asia Pacific Property Digest 2nd Quarter-Market Research and Report: http://www.joneslanglasallesites.com

- Latumahina, G., & Njo, A. (2014). Kesediaan untuk membayar pada green residential. FINESTA, 2(1), 82–86.

- Lovreglio, R. (2016). Modelling decision-making in fire evacuation based on random utility theory [Dissertation]. [Doctoral Program in Environmental and Territorial Safety and Control]. Politecnico di Bari.

- Mandell, S., & Wilhelmsson, M. (2011). Willingness to pay for sustainable housing. Journal of Housing Research, 20(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.2011.12092034

- Mao, D. (2010). A study of consumer trust in internet shopping and the moderationg effect of risk aversion in mainland China. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 2(3), 1–60.

- Njo, A., Made-Narsa, I., Irwanto, A. (2017). Dual process of consumption and investment motives in residential market Indonesia. Proceeding of 22nd International Conference on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate [CRIOCM], 20-23 Nov 2017 550–556.

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Peet, R., & Hartwick, E. (2015). Theories of development: Contentions, arguments, alternatives. Guilford Publications.

- Pramastiwi, F. E., Irham, A. S. & Jamhari , (2011). Willingness to pay coffee farmers to environmental rehabilitation. Journal Economic Development, 12(2), 187–199.

- Priyadharshini, J., & Muthusamy, S. (2015). A survey on investors’ favourite investment avenues in Salem. International Journal of Commerce (IJC), 2(2), 87–92. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3067523

- Putra, R. P. (2020). March 1). "Gak cuma menghemat pengeluaran, ini 5 manfaat kalau kamu hemat listrik". IDN TIMES: https://www.idntimes.com/business/finance/rivandi-pranandita-putra/manfaat-kalau-kamu-hemat-listrik-c1c2/full

- Quintal, V. A., Lee, J. A., & Soutar, G. N. (2010). Tourists' information search: The differential impact of risk and uncertainty avoidance. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(4), 321–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.753

- Ramadhiani, A. (2017). Sektor gedung habiskan 40 persen energi global. December 29, 2019, from Kompas: https://properti.kompas.com/read/2017/04/05/230000221/sektor.gedung.habiskan.40.persen.energi.global

- Retzlaff, R. C. (2009). Green buildings and building assessment system: A new area of interest for planners. Journal of Planning Literature, 24(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412209349589

- Rohrmann, B. (2005). Risk attitude scales: Concepts, questionnaires, utilizations. Project Report, University of Melbourne, Australia, Department of Psychology, Melbourne. http://www.rohrmannresearch.net

- Shafiei, M. W., Samari, M., & Ghodrati, N. (2013). Strategic approach to green home development in Malaysia-the perspective of potential green home buyers. Life Science Journal, 10(1), 3213–3224.

- Simons, R. A., Lee, E., Robinson, S., & Kern, A. (2014). Demand for green buildings: Office tenants’ willingness to pay for green features. Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs, 38, 423–452. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/urban_facpub/1247

- Sotic, A., & Rajic, R. (2015). The review of the definition of risk. Online Journal of Applied Knowledge Management: A Publication of the International Institute for Applied Knowledge Management, 3(3), 17–26.

- Spetic, W., Kozak, R., & Cohen, D. (2005). Willingness to pay and preferences for healthy home attributes in Canada. Forest Products Journal, 55(10), 19–24.

- Stigler, G. J. (1950). The development of utility theory. Journal of Political Economy, 58(4), 307–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/256962

- Tan, T. H. (2011). Measuring the willingness to pay for houses in a sustainable neighborhood. The International Journal of Environmental, Cultural, Economic, and Social Sustainability: Annual Review, 7, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18848/1832-2077/CGP/v07i01/54854

- University College London (2017). High-rise buildings much more energy intensive than low-rise. https://phys.org/news/2017-06-high-rise-energy-intensive-low-rise.html

- Verma, S., Mandal, S. N., Robinson, S., & Bajaj, D. (2020). Diffusion patterns and drivers of higher-rated green buildings in the Mumbai region, India: A developing economy perspective. Intelligent Buildings International, 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17508975.2020.1803787

- WGBC (2021). What is green building? World Green Building Council: https://www.worldgbc.org/what-green-building

- White, E., & Gatersleben, B. (2011). Greenery on residential buildings: Does it affect preferences and perceptions of beauty? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(1), 89–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.11.002