Abstract

Climate change is becoming an increasing concern for many communities, particularly coastal communities subject to tidal and sea-level flooding. As a result, shoreline municipalities walk a fine line between protecting their communities and allowing more development. A prime example of this dilemma is the port city of Charleston, South Carolina, USA. Despite being ground zero for sea-level flooding, the city has seen rapid real estate development growth. This paper analyzes a survey conducted with Urban Land Institute (ULI) members in the Charleston region to understand how the real estate community is coping with and combating flooding impacts. Results show that while residential real estate developers are rethinking their development patterns, commercial developers are slow to recognize the threat of climate change impacts. The paper concludes with suggestions for policies and practices to address these threats, strengthen Charleston’s commercial real estate, and better prepare the city for a safe, prosperous future.

As has been noted by Upton Sinclair, it’s difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it. This applies to all aspects of the climate change discussion. Cost considerations are amplified by the emotional need to not understand the problem.

Anonymous Survey Respondent

Introduction

Charleston, SC, is rapidly becoming the “it” place in the Southeastern US. It is consistently listed as a top destination for tourists by magazines, such as Travel and Leisure and Traveler. In 2015, Forbes ranked it as the 7th best destination for jobs. Invariably, this has not been lost on the real estate industry resulting in extensive development in all four of the major asset classes.

While development is bursting at the seams, Charleston is also ground zero for climate change and its impacts (Cains, Citation2021). The city is already prone to flooding at high tide (Runkle et al., Citation2018) and will, even with moderate sea-level rise, experience chronic inundation by 2100 (Dahl et al., Citation2017; English et al., Citation2021). The city’s nuisance flooding threshold is 7.0 feet (ft.) Mean Lower Low Water (MLLW). Per the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), nuisance flooding results in minimal or no damage. Still, it can lead to public threats and inconveniences, such as water intake pipe backups, street flooding, and flooding in low-lying areas (NOAA, Citation2022). Currently, Charleston has 180 days of nuisance flooding each year on average, with a record 89 days of flooding that breached the 7-foot seawall in 2019 (Mills, Citation2021). In the 1970s, this number averaged two days annually (Riley, Citation2015).

Charleston’s major flooding threshold is 8.0 ft. MLLW means there is little room between nuisance flooding turning into major flooding events. This type of flooding costs the city ∼$12.4 million each year (Cains, Citation2021). With the double punch of climate change being sea-level rise and increased hurricanes, major flooding will become more pronounced and frequent (Magill, Citation2014). Theoretically, coastal real estate valuation should decrease as sea levels rise (Butsic et al., Citation2011). Yet, increasing housing and commercial property prices in coastal cities show that this is not the case (Murfin & Spiegel, Citation2020). This paradigm presents a dilemma for city governments and developers seeking to meet housing and economic needs and implement more comprehensive commercial development resiliency measures (McKenzie, Citation2017).

Resiliency measures can potentially impact commercial development costs and real estate prices (Filippova et al., Citation2020) and, ultimately, a city’s ability to build. Feigel (Citation2015), in a National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) paper developed for its Economics of Community Disaster Resilience Workshop, suggests that resiliency planning must incorporate a variety of quantitative (e.g., frequency, severity, exposure time frames, etc.) and qualitative (e.g., diverse stakeholder input) issues, and indirect costs (e.g., peripheral damage, business interruption, etc.) in cost-benefit analysis (CBA) and return on investment estimates to understand impacts. Thus, the first step for commercial real estate resiliency planning will be for municipalities to establish a baseline of various stakeholders' current efforts, attitudes, and perspectives.

Understanding the dynamic between growth and climate change this paper shows the results of a survey of the ULI Charleston real estate development community to garner how they view climate change impacts, what they are doing to address these impacts, and what they feel the city’s future holds. It first shows climate change/sea-level rise impacts Charleston and how these issues affect real estate developers and developments in the area. Secondly, it explores survey responses in-depth to understand the real estate community’s perspectives on climate change/sea-level rise impacts on current and future developments in the city. Due to the limitation of previous research on commercial real estate and sea-level rise in this area, results also lay the groundwork for future rigorous statistical analysis. Finally, the paper will help stakeholders and policymakers better understand how climate change issues are regarded by the real estate sector and provide insights into tackling these issues.

Background

Climate change is not happening only in faraway places (Amirzadeh & Barakpour, Citation2021; De Koning & Filatova, Citation2020). NOAA has predicted that hurricanes along the southeastern US seaboard and Gulf Coast will increase as the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico continue to warm (NOAA, Citation2018). In fact, severe storms and hurricanes have already increased in frequency (Sobhaninia & Buckman, Citation2022). In fact, during the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season NOAA (Citation2021) recorded 14 named storms and seven hurricanes. The agency noted that this extremely high occurrence made 2021 the third most active season and marked six consecutive years of above-normal activity (NOAA, Citation2021).

The economic impact of hurricanes is widely known with the most memorable and costly hurricanes including Katrina (US$182.5B/1,833 deaths), Harvey (US$141.3B/89 deaths), Maria (US$101.7B/2,981 deaths), Sandy (US$80B/131 deaths), and Ida (US$75B/96 deaths) all occurring within the last 20 years (NOAA & NCEI, 2022; Smith et al., Citation2022; Warren-Myers & Hurlimann, Citation2022). While not the costliest, Sandy was notable for its unique configuration and far-reaching impacts which included the epicenters of the US economy along the Northeastern seaboard (Rafferty, Citation2021).

The effects of Sandy were felt in cities and towns along the Atlantic Coast, including New York City, an area not historically prone to hurricanes (Gould & Lewis, Citation2018; Ortega & Taspinar, Citation2018). For instance, it washed away roads in North Carolina’s Outer Banks and produced record flooding in New York City (New York), New Haven (Connecticut), and Philadelphia (Pennsylvania) (Hoffman & Bryan, Citation2013). Other impacts included crippling mountain snowstorms in West Virginia, Tennessee, and western Maryland; and power disruption in New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, and inland as far as Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin (Gibbens, Citation2019; Hoffman & Bryan, Citation2013; Rafferty, Citation2021). Unfortunately, occurrences like Sandy are expected to become the norm (Buchanan et al., Citation2017).

Thus, coastal communities, even in the Northeast are highly vulnerable to climate change-driven catastrophes (Arkema et al., Citation2013; Runkle et al., Citation2018). In turn, all coastal communities must plan for the slow burn of climate change (e.g., increased temperature change, sea-level rise) that slowly impacts communities and the immediate and direct shocks to the system from intense natural occurrences, such as hurricanes and tidal flooding (Beigi, Citation2016; Tibbetts, Citation2002).

There are generally two approaches to the problem of flooding and coastal sea-level rise: retreat or structural adaptation. In less dense markets, withdrawal from the shore is feasible and more likely (Gould & Lewis, Citation2017). Structural adaptation makes more sense in denser areas considering economic demands and space constraints (Rodríguez & Brebbia, Citation2015). Structural adaptation includes improving structures, raising buildings, and incorporating mechanical equipment to withstand flooding. It can also involve constructing barriers to prevent and minimize the damages from floodwater (Gould & Lewis, Citation2017).

The Impacts of Climate Change on the Real Estate Sector

The real estate sector is increasingly engaged in climate change issues and financial impacts (Gould & Lewis, Citation2018; Shokry et al., Citation2020). For instance, the driving theme of the 2021 Urban Land Institute (ULI) annual conference in Chicago was social equity and sustainability, both of which are major climate change issues. Climate change was also an important theme in PWC and ULI’s 2022 Emerging Trends in Real Estate survey report, a yearly survey of the North American real estate community presented at the ULI annual conference.

According to the report, “a growing consensus sees the property sector as bearing much of the responsibility for climate change” (PWC & ULI, 2021, p. 18). In addition, 80% of survey respondents consider environmental, social, and governance factors (ESG) when making investment decisions (PWC & ULI, 2021, p. 18; Wheeler, Citation2021). Despite the high number of respondents considering these factors, there is little evidence to quantify if investors incorporate climate risks into their decisions.

Hallegatte et al. (Citation2013) posit that it is only a matter of time before more investors consider climate change, as a climate-related natural disaster (more than doubled between 1980 and 2016) and recovery costs increase (Treuer et al., Citation2018). Regardless, there is still a general perception that it is not a pressing concern. A PWC survey respondent summed it up as, “I don’t see a whole lot of people taking climate change and flood risk that seriously…” (Quoted in PwC & Urban Land Institute, Citation2021, p. 19).

If the private real estate sector will play a more significant role, they are not exactly clear what that role will be (Agrawala et al., Citation2011; Coiacetto, Citation2016). A 2019 report by ULI and Heitman entitled Climate Risk and Real Estate Investment Decision-Making made this apparent. The report determined that the real estate community needs to plan for climate change but does not know what that involves or even how to begin. “It is an urgent and complex challenge which must be addressed but for which the industry does not yet have a clear strategy” (ULI, Citation2019, p. 2).

The industry's risks are primarily on two scales: physical and transactional (Warren-Myers & Hurlimann, Citation2022). Per ULI, “physical risks are those capable of directly affecting buildings; they include extreme weather events, gradual sea-level rise, and changing weather patterns. Transaction risks are those that result from a shift to a lower-carbon economy and using new, non-fossil fuel sources of energy” (Urban Land Institute, Citation2019, p. 5). To better understand how these risks will impact the industry, The ULI followed the 2019 report with the 2020 report Climate Risk and Real Estate: Emerging Practices for Market Analysis in 2020. The report showed that future investment decisions will be based more on climate-induced market risk than ever before (ULI, Citation2020).

The 2020 report further suggests that cities proactively investing in resiliency measures may be more attractive to investors as climate change risks become the norm (Beigi, Citation2016; ULI, Citation2020; Wilbanks & Kates, Citation2010). Impacts from flooding, wildfires, and droughts are causing the insurance industry significant losses (Collier et al., Citation2021). From 2010 to 2020, extreme weather event losses were roughly US$3 trillion and over US$1 trillion than the previous decade (ULI, Citation2020). In 2019 alone, 40 global disaster-related events cost upwards of US$1 billion (ULI, Citation2020). In 15 years, it is estimated that residential and commercial real estate sectors will experience a combined loss of over US$63 billion globally and US$1.07 trillion by 2100 due to flooding (Dahl et al., Citation2017).

These losses are impacting the insurance industry and in turn influencing the real estate community, resulting in insurers insuring less real estate in coastal and flood-prone areas (Collier et al., Citation2021). When they do write policies in these areas it is at a premium (Jin et al., Citation2015; Moody’s, Citation2018; Urbina, Citation2016). As a result, insurance companies have the means to minimize the uncertainty associated with climate change (Botzen & van den Bergh, Citation2009). Ultimately, this trend could put the real estate industry underwater, figuratively and literally (Kahn, Citation2016; Lewis, Citation2019).

In areas where insurers are willing to take risks, mortgage companies are bundling and selling their notes to Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. This transfer pushes the risk onto the taxpayer (Flavelle, Citation2019; Ouazad & Kahn, Citation2019). However, federal, state, and local governments are beginning to actively regulate flood insurance. For instance, the state of New Jersey requires planners and developers looking to build in climate-impacted areas to consider climate impacts, including flooding and sea-level rise, before granting government approval (Tully, Citation2020; Urbina, Citation2016). St Petersburg, Florida, has instituted increased controls on where developers can build and in what capacity (Holmes, Citation2019). While local governments like Nashville, Tennessee buy the property outright, to prevent or control development (Schwartz, Citation2019).

Thus, it is becoming more evident that real estate-related climate change risks are becoming evident to the public as well (Botzen & van den Bergh, Citation2009; Westcott et al., Citation2020). Baldauf et al. (Citation2020) assert that people’s beliefs affect housing prices in areas prone to severe climatic events. For example, sea-level rise negatively affects housing prices when people believe that climate change is real (Li, Citation2009; McAlpine & Porter, Citation2018). This relationship receives less attention among climate-skeptical populations (Barrage & Furst, Citation2019). Moreover, prices continue to increase in many of these areas (Gould & Lewis, Citation2018; Miller et al., Citation2019) even though some studies demonstrated that the difficulty in obtaining insurance reduces property values in flood zone areas (De Koning et al., Citation2019).

While real estate values in flood zones are lower than in non-flood zones (Bin & Kruse, Citation2006; Urbina, Citation2016), coastal real estate still commands a higher price. As a result, developers are conflicted on how much building should take place, and real estate agents wonder if they should direct clients away from coastal flood-impacted areas (Urbina, Citation2016). Some of the literature suggests a risk of a climate-driven real estate bubble as more housing is built in climate-prone areas. Like the 2008 real estate bubble, they anticipate that people will walk away from their homes. But unlike that bubble, people will not return (Kates et al., Citation2012; Nolan, Citation2015; Piguet, Citation2018).

Charleston and Climate Change: Impacts and Coping Mechanisms

Climate change issues are the proverbial elephant in the room regarding Charleston’s development. As mentioned, the city is in the crosshairs of climate change (Runkle et al., Citation2018) at the same time, it is seeing rapid growth (Dow & Watson, Citation2018). One only has to open The Post and Courier, the Charleston newspaper, any day of the week to see this dichotomy at play with one page having a story on flooding.

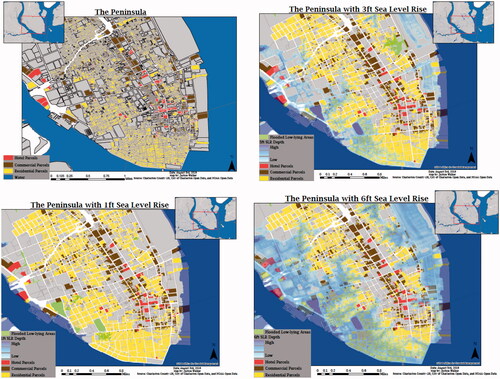

The importance of sea-level rise and related flooding cannot be overlooked as it will significantly impact populations, ecosystems, infrastructures, and real estate in low-lying Charleston (Dahl et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). More than 800 mile-squares of the city’s coastal area lie <4 ft above the high-tide line (Runkle et al., Citation2018). A conservative estimate by scientists is that sea levels will rise 3–4.3 feet by 2100 (Tibbetts & Mooney, Citation2018). However, more recent and sobering projections predict that it will be closer to 6 feet in the Charleston area by 2100 (Runkle et al., Citation2018). depicts how increases of 1, 3, and 6 feet will impact Charleston’s lower peninsula.

Coupled with the city’s growth, the financial impact of flooding will be astronomical if the city does nothing. The city is already seeing these effects. The value of single-family homes in flood-prone areas is decreasing (Tibbetts & Mooney, Citation2018), and affordable housing is in peril (Johnson, Citation2020). Although there is a lack of information regarding commercial real estate, studies show that flood-vulnerable residential housing is losing its value due to increased flood days (Cains, Citation2021). Some project that there will be 180 days of major flooding annually by 2045. These flood events could make almost 86% of properties inaccessible by road (Mills, Citation2021). Thus, the importance of protecting the city from flooding has been at the forefront of the city government (Cains, Citation2021; Wilbanks & Kates, Citation2010).

In 2019, the city commissioned two reports to address flooding: Flooding and Sea Level Rise Strategy (City of Charleston, Citation2019) and The Dutch Dialogues Charleston (Waggoner & Ball, Citation2019a). The Strategy document outlined plans for five critical components—infrastructure, governance, land use, resources, and outreach. Activities include reevaluating the science and revising the strategy annually, implementing building codes and zoning ordinances that support resilience, incentivizing flood mitigation, improving drainage systems, constructing manmade and natural shoreline protections, and promoting community outreach and partnership building, among others (City of Charleston, Citation2019), with many initiatives are complete or underway (City of Charleston, Citation2022).

The nearly two-year-long (2018–2019) Dutch Dialogues report explored four distinct parts of the city—Johns Island, Church Creek, the Lockwood Corridor/Charleston Medical District, and the New Market/Verdell’s Creek area. The Lockwood Corridor and New Market areas are located on the west and east sides of the Peninsula, respectively. The goal was to develop a comprehensive water management plant for these areas that are “experiencing the limits of ‘pump and drain’ due to recurrent, more severe storms with extreme precipitation, increased river discharge, and sea-level rise” (Waggoner & Ball, Citation2019b).

The report offered various ways to manage water and combat flooding. Mechanisms include stormwater storage, drainage tunnels, stormwater control, citizen involvement, and groundwater management (Waggoner & Ball, Citation2019a).

Beyond more localized green and resilient types of protection, the city is also looking to radical infrastructure measures (Allen et al., Citation2019). In conjunction with the US Army Corps of Engineers, the city is investigating the construction of a seawall to protect the lower peninsula. The original proposal for the wall was to cost $1.7 billion. However, more recent projections (as of November 2021) have it at $1.1 billion, with the Army Corps taking on $775 million and the city taking on the remaining $325 million of the costs (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Citation2021). Whether through hardening and infrastructure, or greener resilient measures, the city will need to protect the peninsula and real estate valuation.

Methods

Researchers surveyed ULI South Carolina regional chapter members to understand stakeholders' opinions within Charleston’s development community. Preliminary interviews were conducted with three key stakeholders within the Charleston community. These in-person interviews allowed the researchers to determine survey questions that addressed the concerns of the community. Once the survey was written and designed, it was sent to three different stakeholder groups for vetting.

The ULI community was chosen as it has been one of America’s most widely quoted sources of real estate, development, and urban planning for years. Moreover, the ULI Charleston area chapter’s objective has always been to encourage the link between real estate development, urban planning, and leadership, which is well-aligned with the goals of this study. Finally, ULI Charleston has a particular interest and understanding of climate-related impacts on the real estate industry.

The survey was sent first via direct email, then two weeks later in conjunction with ULI through their October 2021 e-newsletter, reaching 350 ULI members. Fifty-five (55) members responded, resulting in a response rate of 16%. This represents a higher-than-average response rate for most South Carolina ULI chapter surveys.

Surveys consisted of 18 substantive questions and one asking if the respondent wished to be interviewed. Questions included seven open-ended, four Likert-scale (rating from 1 to 5), four yes or no questions, and three demographic, such as “Are you in the private or public sector?” Demographic questions defined what segment of the development community respondents were in (e.g., real estate), what sector, and their role within their company.

The following five questions focused on climate change impacts on Charleston and the real estate community, measures to combat climate change, and where climate change had the most significant effects. The next three questions revolved around whether climate change impacted their developments and planning. The last questions centered on who should spearhead climate change protection and what developers could be doing to help combat the problem. Lastly, the survey asked about the cost constraints of climate change adaption.

Survey Results

Qualitative coding content analysis was used to analyze the data and draw meaning, especially from the open-ended questions. This method helped the researchers compare the data and respondents’ perspectives across different sectors and three categories—demographics, Charleston climate change, and companies' roles and cost burdens. Results show multiple views on climate change's impact on the Charleston real estate community. Climate change is seen as a significant issue for the area from a general perspective. Yet, there is not as much concern within the actual day-to-day activities of the real estate profession. Furthermore, development changes that are made are primarily self-imposed as municipal governments were seen as not doing enough for those concerned about making changes in the real estate community. Notably, a significant hindrance to making climate change-related adjustments was cost. Respondents felt that costs should be split between the private and public sectors.

Demographics

The first questions gathered sector, company, and respondents’ job information. It is important to note that questions did not ask about the respondents' age, race, or gender. The questionnaire, as stated, was sent out to 350 people who were part of the ULI in the Charleston area.

Respondents varied from real estate developers (42%), architects (23.5%), city government officials (5.9%), and brokers (5.9%) (). While it was no surprise that there were few city government respondents as ULI is a private sector organization, the low number of brokers is a bit curious.

Table 1. What is your primary business related to real estate? (The table contains the percentage of the survey respondents and the overall ULI demographic in each category).

The second question asked if the respondent was involved in real estate development, brokerage, architecture, or urban planning and design. Answers were evenly split between multi-family and office developers and the retail sector. Respondents’ roles within their companies represented a wide swath. The majority were owners and CEOs (57.5%), followed by architects, urban planners and designers, and business developers (32.5%). A few respondents (9.5%) were construction managers, attorneys, and lenders ().

Table 2. If you answered A, B, or C: what area of real estate do you specialize in? (Check all that apply).

Charleston Climate Change in General

The next set of questions dealt with climate change in Charleston, general ideas around the issue, and real estate’s role. Regarding the concern about climate change in the Charleston region, 50% of respondents indicated it was a “major” concern and 21% a “significant” concern. Of those 44% of the respondents were in real estate, and 56% were from other fields. Thus, 62% of the real estate-associated respondents consider climate change concern, demonstrating that it is becoming more alarming. On the other end of the spectrum, 14% said it was “not a major” concern to the region. Sixty-two percent of these respondents were in real estate, indicating that there are still those who do not consider addressing the issue as an urgent concern ().

Table 3. Do you see climate change as a major concern for the Charleston Region? Rate 1–5, with 5 being a major concern and 1 not being a major concern.

The next question asked if respondents saw climate change as a “major” concern for the real estate community itself. 50% of respondents see it as a “minimal” concern. Of these, 58% were in the real estate business. While 24% of architecture, urban design, and engineering respondents declared climate change as a “major” concern to the real estate sector, only 11% of real estate-associated respondents felt that it was. Finally, 24% of real estate respondents do not think that climate change is a concern to the real estate community at all ().

Table 4. Do you see concern for climate change in the real estate development community in Charleston? Rate 1–5 with 5 being a major concern and 1 not being a major concern.

The answer to this final question presents an interesting point of discussion. While half of the respondents saw climate change as a fundamental issue for the Charleston region, only 11% saw it as a critical concern for the real estate community. Moreover, most real estate sector responses fell in the mid-range of the Likert scale. These findings suggest that climate change is not an issue within the real estate community or that many in the field refuse to make it an issue. Given the survey findings and anecdotal insights, it is most likely a combination of them.

Company and Cost Issues

The last set of Likert-designed questions asked what the real estate community is or is not doing about climate change and who should shoulder the costs. Eighty percent of respondents stated that company climate-related changes were self-directed. Of these, 75% were real estate respondents. Eight percent reported that changes were imposed by underwriters (). This was an interesting finding as a hypothesis of this study is that underwriters, both insurance and funders, would be forcing developers to make changes. While these findings might disprove the theory, it could also be that the study was premature or that developers are getting ahead of underwriters’ requirements.

Table 5. If you or your company are making changes or planning to make any changes are they.

The next two questions were about the impact of climate change on development patterns. Overwhelmingly, 82% of the respondents felt that development was not shying away from areas subject to flooding. Of these, 48% were real estate developers, and 52% were architects and urban planners (). In addition, 63% saw no development shift to different locations due to climate change (). Specifically, 54% in the real estate sector and 72% among architects and urban planners saw no shift in development patterns. So, even though respondents believe that retreating from the flood-prone areas is necessary and should be required, they are not seeing nor shifting development. This result presents an interesting paradox that will be discussed more in the discussion of the open-ended questions.

Table 6. Are developers shying away from those areas subject to flooding?

Table 7. In relation to the previous two questions, do you see development patterns shifting to different locations because of climate change?

Questions about who should carry the cost burdens and who should be responsible for combatting climate change followed. A large majority (68%) of those surveyed thought that the municipal government was not doing enough to combat climate change (65% of real estate sector respondents and 72% of other groups). Fifty-six percent felt that the private sector should bear most of the climate change adaptation costs, and 44% felt it should be the public sector. Specifically, 64% of real estate-associated respondents thought the public sector should deal with the climate change costs, while 72% of architects and urban planners thought the private sector should be responsible. Lastly, costs were seen as a significant issue (70%) when instituting climate change adaptation. The majority (86%) were architects, urban planners, and city officials.

These results show that each group put the responsibility on the other side. For instance, most architecture, urban planning, and city groups believe that the private sector is more responsible for the costs. They are not considering climate change mitigation factors because of that cost. In contrast, the real estate sector considered the public sector responsible, and most did not identify cost as their reason for disregarding mitigations.

Open-Ended Questions

Researchers also asked a set of open-ended questions to obtain more nuanced answers. These questions sought to understand what measures their firms were taking, where the most significant impact of climate change was in real estate patterns, is the government doing enough, what the development community should be doing, is cost an issue to adaptation, and how developers are dealing with the costs of adaptation and a final prompt for additional comments. Answers reflected the previous questions while providing researchers with a deeper understanding of the issue.

The first question posed asked: What measures if any, you/your company were taking in your developments to deal with climate change? Flooding, heat or resilience/preparedness for hurricanes, etc.? Answers showed that most respondents are taking minimal steps, just enough to cover what was needed without hurting the bottom line. In general, this includes building on higher ground and using sustainable building materials, including drainage systems. A few respondents reported that their companies were doing more than the minimum. As one respondent said: “We are designing more bioswales and other stormwater management systems that mimic nature to help manage water on the property in addition to typical engineered solutions” (see ).

Table 8. What measures, if any, are you/your company taking in your developments to deal with climate change? Flooding, heat or resilience/preparedness for hurricanes, etc.?

Among real estate-associated respondents, the most repeated measure mentioned was improving resilience and preparing for flooding and hurricanes. Other measures included efficient utilities and infrastructure systems, increasing topography, buying land in non-flood areas, resilient material, drainage upgrades, more green spaces, sustainable building, permeable surfaces, and land planning. Among architecture and urban planning respondents, resilience and preparing buildings for drastic climate change was the most repeatedly mentioned measure. Other strategies included stormwater management systems, climate adaptation engineering plans, drainage, and recycling materials.

The second open-ended question asked: In regard to real estate development patterns, where do you see climate change having the greatest impact? Most respondents believe climate change effects on real estate development are most evident in floodplains, low-lying areas, and coastal areas. In the case of real estate-associated respondents’ opinions, impacts are felt primarily in flood-prone area values, insurance prices, and infrastructure investment. However, architects and urban designers are centered on site selection and the location of new developments. Some believe that developers are retreating from flood-prone areas. Others thought that, although there is limited available land for coastal development that is more susceptible to future disasters, they are still many desirable sites (see ).

Table 9. In regard to real estate development patterns where do you see climate change having the greatest impact?

As mentioned earlier, Charleston’s lower peninsula is in grave danger of flooding and suffering the impacts of climate-induced sea-level rise. Yet, there was minimal discussion about moving away from the lower peninsula. One respondent who talked about it did so from a valuation perspective, “Sea level rise is obvious, although I imagine we will figure out how to seal off the peninsula’s most valuable land.”

There could be various reasons for the lack of discussion. One reason could be that when discussing low-lying areas and areas of flooding, respondents assume we know that means the lower peninsula. Alternatively, reasons could be financially driven as the lower peninsula is prime real estate, a characteristic that often wins out over climate change and safety issues.

Next came a couple of questions regarding the government’s role, including: What should government be doing, and What are the best and worst things it is doing or not doing? Answers were much more varied than the previous open-ended questions. Responses ranged from issues of zoning, “Zoning restrictions should be re-evaluated. Too many larger scale projects being built in flood-prone areas,” to disallowing development in certain areas.

For instance, one respondent stated that they should be “precluding development at all in certain areas.” Another mentioned that “They should be restricting development in flood-prone areas, placing restrictions on the percentage of the property that can be impervious, and being stricter on what developers are required to do to combat come of these climate change issues.” These statements around zoning and restrictions highlight the notion that developers will not stop building in flood zones unless regulated.

Beyond zoning, some respondents focused on funding and infrastructure as maintaining the status quo. Overall, those who believe the government is not doing enough revolved around two general ideas. First, land planning was needed to restrict the development in flood-prone areas and incentivize development in other areas. Second, governments should incorporate more resiliency strategies in developments and infrastructure. Real estate-associated respondents are more inclined toward the former, and architects and urban planners toward the latter.

Among the respondents who believe that the government is not doing enough, one respondent mentioned the need for a “Good pump system. The city will flood–a fact of geography. If it gets worse, the developers and investors will slowly move the city to wherever the higher ground is–further upriver.” This last quote is particularly telling. While Charleston is a great place to build, growth can only continue if sustainable. Further suggestions included taming sea-level rise via technological mechanisms, such as pumps or a one plus billion-dollar sea wall (see ).

Table 10. If you answered NO to the previous question, what should the government be doing? If you answered yes, what are the best and worst things it is doing or not doing?

Surveyors were asked what the government should do and their responsibilities. Specifically, they were asked: What role, if any, does or should the development community have in combatting climate change? This question, by its nature, is somewhat self-reflective and demands a degree of self-critique. Overall, respondents felt that the community needed to literally and figuratively “build to higher standards” and “should lead.” There was also discussion around looking beyond profits and the need for developers to become more responsible “…to investors and the future by making sound decisions that are not always looking first to the bottom line.” Echoing this, another respondent stated that “most development decisions are understandably business-based and the short-term economics of resilient design, unfortunately, are not the best for the bottom line.”

These answers show that the real estate community knows they must do better but feel constrained by costs and a project's return on investment. Moreover, results show that real estate-associated respondents are interested in sustainable developments that adopt higher standards of construction to combat climate change impacts. Respondents from other areas of expertise emphasized that the development community should manage the water that falls on their property and their developments’ effects on surrounding areas (see ).

Table 11. What role, if any, does or should the development community have in combatting climate change?

Cost is a prevailing factor in all climate change discussions, and adaptation issues represent the elephant in the room. Questions on cost included: What role is cost playing in the added effort of climate change adaptation, and How are developers dealing with the cost of climate change adaptation, and how would those costs be better dealt with in the future? Responses to the first question revealed that cost plays a significant role, as it equaled “higher construction costs, more resilient materials.” Additionally, others expressed that it was becoming too expensive to build in coastal and flood-prone areas.

But this creates a dilemma in the minds of developers. As one respondent noted, “Coastal development is becoming more expensive to build, but prices are still increasing. Demand is there, so supply follows. Profits and taxes that are generated have to be more wisely invested.” This was echoed by a respondent who highlighted the continued demand and the polarization between those who can and cannot develop. “Only developers who think Charleston is still a ‘good deal’ will continue to operate there. Increased costs definitely shut out the smaller developers.” These insights quickly sum up the issue of cost. It supports the mindset that while it is becoming more expensive to build, both from a land perspective and a construction cost perspective, people will pay the price to live in a desirable place ().

Table 12. If you answered yes to the issue of cost, what role is cost playing in the added effort of climate change adaptation?

Overall, results show that adaptation is viewed as expensive. Therefore, developers are unwilling to adopt it unless it is required or profitable. They also highlight that developers are more concerned with economic constraints and short-term profits than long-term climate effects. Per one respondent, “Added costs for mitigating effects of climate change cut into a developers’ bottom line, it’s understandable why they would not want to make these changes and spend extra money which is why it should be a requirement” (see ).

Table 13. Again, if yes.

The last question asked respondents to provide additional comments. While much of what was offered had already been covered, there was a prevailing sentiment that to combat the issue of climate change and sea-level rise in Charleston, it would have to be a partnership between the private and public sectors. Others pointed to the government as the underlying issue.

“Climate change is an excuse by the government to restrict development. We do not build in floodplains, wetlands, streams, or buffers. We are required to follow DHEC and OCRM stormwater regulations. The development community keeps getting squeezed hard and harder for buildable land. Thus, we build further out and are surprised when sprawl occurs. Zoning and utilities are the best way to combat climate change by allowing higher densities on good land.”

While some see government as an obstruction, others see it as a mechanism for changing course. In their mind, the successful developer gets in front of the issue. “No one gets to opt into climate. So those developers willing to boldly address it will ultimately have a much better position than those avoiding for as long as possible” (see ).

Table 14. Is there anything you would like to add?

Conclusion

This research shows that a significant portion of the survey respondents is taking a business-as-usual approach and do not fully see or acknowledge the long-term negative impacts of climate change. Per one respondent, their company addresses “Flooding and preparedness for hurricanes, but we have always done that unrelated to climate change.” The overall sentiment was that climate change was not a grave concern, despite 50% of the community believing it is an issue.

Responses indicated that much of the community takes a minimalist approach to adaptation. For instance, answers included “Buy high ground, such as it is,” “paying close attention to flood maps and instituting drainage upgrades while evaluating new acquisitions,” or “… minor upgrades to energy infrastructure with LED lights and new HVAC systems.” In general, it appears that developers believe that the minimalist approach is enough to make financial partners and governmental entities happy.

While the survey results disclose that developers should do more, respondents believe that most of the burden should fall on the backs of the government to secure areas for development. This would make it profitable for developers to continue to build. Suggestions included government should be “More aggressive about tying development entitlements to more resilient approaches to development and creating funding to invest in mitigation/infrastructure measures,” and “Making deliberate decisions to move the needle for development interests implementing incentive-based regulations that actually encourage developers to incorporate more resilient strategies in their developments.”

The issue of profit remains a driving force in the minds of the community. The study demonstrates that developers will continue to build in areas prone to climate change impacts if it is profitable. Even as the cost of doing business increases, both in terms of adaptation strategies and effects on the development paradigm, there are those willing to pay the premium. This disparity forces some smaller developers with less financial backing out of the game and creates inequity in development. “Sea-level rise is obvious, although I imagine we will figure out how to seal off the peninsula's most valuable land. Obviously, [this] raises an equity question in terms of less valuable land ….”

This research lays the groundwork for understanding Charleston’s real estate and development community’s perspectives on climate change. Yet, questions prevail. For instance, will it just become too expensive to do business in an area like Charleston as investors and insurance underwriters begin to shy away; will climate change ever really matter to developers with very short time horizons (e.g., 2–10 years from breaking ground to selling off the asset); or will developers just run the course in Charleston until the price gets too high and move on?

The development community and government will have to deal with these and similar questions regarding Charleston’s fate in the face of climate change. While being on the minds of the community, climate change is not resulting in severe changes in how development is moving forward. Round table discussions with government officials, experts, stakeholders, and local consultants can be very beneficial to change the perception of climate change for the development community. Thus, we suggest the continued engagement of these stakeholders to raise awareness and understanding of the urgency of addressing climate change.

Acknowledgments

We would also like to acknowledge the support received from graduate assistants Justice Walker and Hope Warren, who helped with the project.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agrawala, S., Carraro, M., Kingsmill, N., Lanzi, E., Mullan, M., Prudent-Richard, G. (2011). Private sector engagement in adaptation to climate change: Approaches to managing climate risks. OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 39. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5kg221jkf1g7-en

- Allen, T. R., Crawford, T., Montz, B., Whitehead, J., Lovelace, S., Hanks, A. D., … Kearney, G. D. (2019). Linking water infrastructure, public health, and sea level rise: Integrated assessment of flood resilience in coastal cities. Public Works Management & Policy, 24(1), 110–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X18798380

- Amirzadeh, M., & Barakpour, N. (2021). Strategies for building community resilience against slow-onset hazards. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 66, 102599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102599

- Arkema, K. K., Guannel, G., Verutes, G., Wood, S. A., Guerry, A., Ruckelshaus, M., Lacayo, M., & Silver, J. M. (2013). Coastal habitats shield people and property from sea-level rise and storms. Nature Climate Change, 3(10), 913–918. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1944

- Baldauf, M., Garlappi, L., & Yannelis, C. (2020). Does climate change affect real estate prices? Only if you believe in it. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(3), 1256–1295. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhz073

- Barrage, L., & Furst, J. (2019). Housing investment, sea level rise, and climate change beliefs. Economics Letters, 177, 105–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2019.01.023

- Beigi, S. (2016). How can resilience influence gentrification for creating sustainable urban systems? University of Oxford.

- Bin, O., & Kruse, B. (2006). Real estate market response to coastal flood hazards. Natural Hazards Review, 7(4), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2006)7:4(137)

- Botzen, W. W., & van den Bergh, J. C. (2009). Bounded rationality, climate risks, and insurance: Is there a market for natural disasters? Land Economics, 85(2), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.85.2.265

- Buchanan, M. K., Oppenheimer, M., & Kopp, R. E. (2017). Amplification of flood frequencies with local sea level rise and emerging flood regimes. Environmental Research Letters, 12(6), 064009. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa6cb3

- Butsic, V., Hanak, E., & Valletta, R. G. (2011). Climate change and housing prices: Hedonic estimates for ski resorts in western North America. Land Economics, 87(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.87.1.75

- Cains, M. G. (2021). Integrating climate change vulnerability, risk, and resilience for place-based assessment of socio-ecological systems: Charleston harbor watershed [Doctoral dissertation]. Indiana University.

- City of Charleston (2019). Flooding and sea level rise strategy. Retrieved from https://www.charleston-sc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/20299/Flooding-and-Sea-Level-Rise-Strategy-2019-web-viewing?bidId=

- City of Charleston (2022). SLR rise initiatives champion chart: Champion chart. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vQzHAUlbeRUHu6gWbJlJyQzTxQW_lB9t5IW3RICSGrDwIKCSSOB0pqM4n1UMC7525_uaGBYXFV9I_pW/pubhtml?gid=1635394151&single=true

- Coiacetto, E. (2016). Climate change adaptation in private real estate development: Essential concepts about development for feasible research, regulation and governance. In Climate adaptation governance in cities and regions: Theoretical fundamentals and practical evidence (pp. 251–266). Wiley.

- Collier, S. J., Elliott, R., & Lehtonen, T. K. (2021). Climate change and insurance. Economy and Society, 50(2), 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2021.1903771

- Collins, D., & Kearns, R. (2008). Uninterrupted views: Real-estate advertising and changing perspectives on coastal property in New Zealand. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(12), 2914–2932. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4085

- Dahl, K. A., Fitzpatrick, M. F., & Spanger-Siegfried, E. (2017). Sea level rise drives increased tidal flooding frequency at tide gauges along the US East and Gulf Coasts: Projections for 2030 and 2045. PLOS One, 12(2), e0170949. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170949

- Dahl, K., Cleetus, R., Spanger-Siegfield, , Caldas, A., & Worth, P. (2018). Underwater: Rising seas.

- Dahl, K. A., Spanger-Siegfried, E., Caldas, A., & Udvardy, S. (2017). Effective inundation of continental United States communities with 21st century sea level rise. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 5. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.234

- De Koning, K., & Filatova, T. (2020). Repetitive floods intensify outmigration and climate gentrification in coastal cities. Environmental Research Letters, 15(3), 034008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab6668

- De Koning, K., Filatova, T., & Bin, O. (2019). Capitalization of flood insurance and risk perceptions in housing prices: An empirical agent‐based model approach. Southern Economic Journal, 85(4), 1159–1179. https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12328

- Dow, K., & Watson, S. (2018, December). Addressing flooding and sea level rise risks in collaboration with communities in the Greater Charleston metro area. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, American Geophysical Union (Vol. 2018, p. PA11I-0847).

- English, E. C., Chen, M., Zarins, R., Patange, P., & Wiser, J. C. (2021). Building resilience through flood risk reduction: The benefits of amphibious foundation retrofits to heritage structures. International Journal of Architectural Heritage, 15(7), 976–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/15583058.2019.1695154

- Feigel, R. (2015). Economics of community disaster resilience: Impact of variability and uncertainty. In B. M. Ayyub, R. E. Chapman, G. E. Galloway, & R. N. Wright (Eds.), Economics of community disaster resilience workshop proceedings. NIST Special Publication. Retrieved from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-C13-a9ffb25eeced0d295ba30a638db68998/pdf/GOVPUB-C13-a9ffb25eeced0d295ba30a638db68998.pdf

- Filippova, O., Nguyen, C., Noy, I., & Rehm, M. (2020). Who cares? Future sea level rise and house prices. Land Economics, 96(2), 207–224. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.96.2.207

- Flavelle, C. (2019). Lenders’ response to climate risk has echoes of subprime crisis. The New York Times, September 28.

- Gibbens, S. (2019). Hurricane Sandy explained: Superstorm Sandy was actually several storms wrapped together, which made it one of the most damaging hurricanes ever to make landfall in the US. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/hurricane-sandy

- Gould, K. A., & Lewis, T. L. (2018). From green gentrification to resilience gentrification: An example from Brooklyn. American Sociological Association.

- Gould, K. A., & Lewis, T. L. (2017). Green gentrification: Urban sustainability and the struggle for environmental justice. Routledge.

- Hallegatte, S., Green, C., Nicholls, R. J., & Corfee-Morlot, J. (2013). Future flood losses in major coastal cities. Nature Climate Change, 3(9), 802–806. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1979

- Hoffman, P., & Bryan, W. (2013). Comparing the impacts of northeast hurricanes on energy infrastructure. US Department of Energy. Retrieved from https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2013/04/f0/Northeast%20Storm%20Comparison_FINAL_041513b.pdf

- Holmes, A. (2019). As flood risk rises in St Petersburg, city weighs whether to allow increased development in flood zones. Tampa Bay Times, July 26.

- Jin, D., Hoagland, P., Au, D. K., & Qiu, J. (2015). Shoreline change, seawalls, and coastal property values. Ocean & Coastal Management, 114, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.06.025

- Johnson, C. (2020). Sea rise imperils affordable housing in Charleston and other coastal areas, study finds. The Post and Courier. Retrieved from https://www.postandcourier.com/business/real_estate/sea-rise-imperils-affordable-housing-in-charleston-and-other-coastal-areas-study-finds/article_81be71a4-34ab-11eb-aac2-4352b244fa90.html

- Kahn, M. E. (2016). The climate change adaptation literature. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 10(1), 166–178. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rev023

- Kates, R. W., Travis, W. R., & Wilbanks, T. J. (2012). Transformational adaptation when incremental adaptations to climate change are insufficient. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(19), 7156–7161. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1115521109

- Lewis, R. (2019). Factoring the effects of climate change into real estate investments. The Washington Post, March 8.

- Li, R. Y. M. (2009). The impact of climate change on residential transactions in Hong Kong. Retrieved from SSRN 1429727.

- Magill, B. (2014). The front lines of climate change: Charleston’s struggle. Climate Central, 2018.

- McAlpine, S. A., & Porter, J. R. (2018). Estimating recent local impacts of sea-level rise on current real-estate losses: A housing market case study in Miami-Dade. Population Research and Policy Review, 37(6), 871–895.

- McKenzie, J. B. (2017). Resilience planning in a coastal urban environment: An analysis of climate change planning policy and procedure in Charleston, South Carolina [Doctoral dissertation]. Columbia University.

- Miller, N. G., Gabe, J., & Sklarz, M. (2019). The impact of water front location on residential home values considering flood risks. Journal of Sustainable Real Estate, 11(1), 84–107. https://doi.org/10.22300/1949-8276.11.1.84

- Mills, G. (2021, May 1). Sea level rise and coastal flooding in Charleston: A resilience and adaptation plan. Retrieved from http://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories

- Moody’s. (2018). Climate change risks outweigh opportunities for P&C (re)insurers. Retrieved from https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Moodys-Climate-change-risks-outweigh-opportunities-for-PC-reinsurers.pdf

- Murfin, J., & Spiegel, M. (2020). Is the risk of sea level rise capitalized in residential real estate? The Review of Financial Studies, 33(3), 1217–1255. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhz134

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration & National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). (2022). Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones. Retrieved from https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/dcmi.pdf

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2018). Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables update. National Hurricane Center.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2021). Active 2021 Atlantic hurricane season officially ends. Retrieved from https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/active-2021-atlantic-hurricane-season-officially-ends

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2022). Severe weather 101 – Floods. National Severe Storms Laboratory.

- Nolan, J. R. (2015). Land use and climate change bubbles: Resilience, retreat, and due diligence. William and Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review, 39, 321–365.

- Ortega, F., & Taspinar, S. (2018). Rising sea levels and sinking property values: Hurricane Sandy and New York’s housing market. Journal of Urban Economics, 106, 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2018.06.005

- Ouazad, A., & Kahn, M. E. (2019). Mortgage finance in the face of rising climate risk. NBER Working paper 26322 on September 30, 2019.

- Piguet, E. (2018). Back home or not. Nature Sustainability, 1(1), 13–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-017-0011-y

- PwC & Urban Land Institute. (2021). Emerging trends in real estate 2022. Urban Land Institute.

- Rafferty, J. P. (2021). Superstorm Sandy. Encyclopedia Britannica, October 12. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/event/Superstorm-Sandy

- Riley, J. P. Jr. (2015). Sea level rise strategy. City of Charleston, South Carolina, December. Retrieved from https://www.charleston-sc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/10089

- Rodríguez, G. R., & Brebbia, C. A. (Eds.). (2015). Coastal cities and their sustainable future (Vol. 148). WIT Press.

- Runkle, J., Svendsen, E. R., Hamann, M., Kwok, R. K., & Pearce, J. (2018). Population health adaptation approaches to the increasing severity and frequency of weather-related disasters resulting from our changing climate: A literature review and application to Charleston, South Carolina. Current Environmental Health Reports, 5(4), 439–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-018-0223-y

- Schwartz, J. (2019). A city offers money to flee flood zone. The New York Times, July 6.

- Shokry, G., Connolly, J. J., & Anguelovski, I. (2020). Understanding climate gentrification and shifting landscapes of protection and vulnerability in green resilient Philadelphia. Urban Climate, 31, 100539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2019.100539

- Smith, A., Enloe, J., Lott, N., & Ross, T. (2022). U.S. billion-dollar weather & climate disasters 1980–2021. Retrieved from https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/events.pdf

- Sobhaninia, S., & Buckman, S. T. (2022). Revisiting and adapting the Kates-Pijawka disaster model: A reconfigured emphasis on anticipation, equity, and resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 69, 102738.

- Tibbetts, J. (2002). Coastal cities: Living on the edge. Environmental Health Perspectives, 110(11), A674–A681. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.110-a674

- Tibbetts, J., & Mooney, C. (2018). Sea level rise is eroding home values, and owners might not even know it. The Washington Post, August 20. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/sea-level-rise-is-eroding-home-value-and-owners-might-not-even-know-it/2018/08/20/ff63fa8c-a0d5-11e8-93e3-24d1703d2a7a_story.html

- Treuer, G., Broad, K., & Meyer, R. (2018). Using simulations to forecast homeowner response to sea level rise in South Florida: Will they stay or will they go? Global Environmental Change, 48, 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.10.008

- Tully, T. (2020). New Jersey to become first state to make builders consider climate change. The New York Times, January 27.

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (2021). Charleston peninsula coastal flood risk management study. Retrieved from https://www.sac.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Supplemental-Funding/Charleston-Peninsula-Study/

- Urban Land Institute. (2019). Climate risk and real estate: Investment decision-making. Urban Land Institute.

- Urban Land Institute. (2020). Climate risk and real estate: Emerging practices and market assessment. Urban Land Institute.

- Urbina, I. (2016). Perils of climate change could swamp coastal communities. The New York Times, November 24.

- Waggoner & Ball. (2019a). The Dutch Dialogues™ Charleston. Retrieved from https://www.charleston-sc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/25055/Dutch-Dialogues-Charleston_Final-Report-September-2019

- Waggoner & Ball. (2019b). The Dutch Dialogues™ Charleston: Grounded in science, driven by design. Retrieved from https://www.charleston-sc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/24059/2019_0426-Dutch-Dialogues-Charleston-Handout-overview-of-4-Project-Areas

- Warren-Myers, G., & Hurlimann, A. (2022). Climate change and risk to real estate. In P. Tiwari & T. Miao (Eds.), A research agenda for real estate (p. 1). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

- Westcott, M., Ward, J., Surminski, S., Sayers, P., Bresch, D. N., & Claire, B. (2020). Be prepared: Exploring future climate-related risk for residential and commercial real estate portfolios. The Journal of Alternative Investments, 23(1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.3905/jai.2020.1.100

- Wheeler, B. (2021). Sustainable real estate investments are no longer optional. Planetizen, September 12.

- Wilbanks, T. J., & Kates, R. W. (2010). Beyond adapting to climate change: Embedding adaptation in responses to multiple threats and stresses. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 100(4), 719–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2010.500200