ABSTRACT

The Rohingya is a stateless minority group in Myanmar, suffering from ethnic and religious armed conflicts, state persecution, and displacement. Since the escalation of violent conflicts in the early 2010s, they have fled the country and sought refuge in neighbouring countries, and in the biggest numbers, in Bangladesh. Living in densely populated refugee camps, Rohingya children receive very limited access to education and are exceptionally vulnerable to illnesses, violence and trafficking. This discussion paper describes the conditions and contexts under which education is offered, and identifies the serious problems and gaps in provision for Rohingya children in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

“To invest in education is not only to respect a fundamental right but also to build peace and progress for the world’s peoples. Education for all, by all, throughout life: this is the great challenge. One which allows of no delay. Each child is the most important heritage to be preserved”. The Human Right to Peace Declaration by the Director General of UNESCO, January 1997 (UNESCO, Citation1997, p. 11).

Introduction

Education is recognised as one of the fundamental human rights under international and regional human rights law and in many international documents (McCowan, Citation2013) including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) [Article 26], the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) [Articles 28, 29 and 32] (UNICEF, Citation1989), and the Dakar World Education Forum Framework for Action (2000). Education is also vital for understanding other human rights (Lee, Citation2013). As “the concept of human rights is inseparable from their role in international political practice” (Dum, Citation2016, p. 130), education is essential for reflection and agency. The right to education also involves learning about rights and responsibilities to become a good citizen and it encompasses civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights. Education unlocks the potential of individuals who are marginalised socio-economically and culturally to pull themselves out of poverty and acquire the means to participate fully in their communities.

Education is a life-saving, life-sustaining and life-transforming life-long process and the foundation of children’s futures. It provides children with the understanding, knowledge and skills to build more prosperous futures for themselves and their communities. Children suffer a lot during conflict and forced displacement (Machel, Citation2001; Talbot, Citation2013). Getting quality education reduces the likelihood of children replicating violence they may have experienced during a conflict or disaster (Lerch & Buckner, Citation2018). Education provided in the conflict-affected and fragile contexts where humanitarian intervention inevitable is called “education in emergencies”. However, providing quality education to children in emergencies also creates the opportunity for learning and can equip them to face on-going crises as well as crises to come (Sinclair, Citation2001). Thus, education in emergencies offers “structure, stability and hope for [the] future during a time of crisis” (INEE, Citation2004, p. 5) as “quality education provides physical, psychosocial and cognitive protection that can sustain and save lives” and “helps to heal the pain of bad experiences, build skills, and support conflict resolution and peace building” (INEE, Citation2010, p. 2).

According to the UNHCR (Citation2015: Online), “[e]ducation in emergencies provides immediate physical and psychosocial protection, as well as life-saving knowledge and skills (for example, with respect to disease prevention, self-protection, and awareness of rights). If children and youth receive safe education of good quality during and after an emergency, they will be exposed less frequently to activities that put them at risk. They will also acquire knowledge and mental resources that increase their resilience and help them to protect themselves”. Although all children including Rohingya refugee children living in the refugee camps in Bangladesh have a fundamental right to basic education, in practice, these displaced children have a very limited access to education. The types and quality of education as well as duration of learning offered to them is not enough for providing basic education. According to the Article 13 of the International Covenant, the right to receive an education includes four essential features, viz. Availability, Accessibility, Acceptability, and Adaptability (UN General Assembly, Citation1966). However, it is important to examine the role that states (host country and country of origin) and the international community play in securing for the Rohingya refugee children both the right to education and the notion of human development through education implied for them; having the right to education is significant if that enables them to do something which they value (Sen, Citation1992, Citation1993). There are many challenges to providing education to the Rohingya refugee children, including inadequate learning space, lack of teaching staff and trained teachers, enough resources, language barriers, psycho-social, cultural and political issues.

The Rohingyas are a stateless ethnic minority of Myanmar who are both internally and externally displaced due to political and communal conflicts. According to the international legal definition, “a person who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law” (UNHCR, Citation2014, p. 8) is a stateless person. That means he or she does not have a nationality of any country. Rohingyas from Rakhine State have been denied citizenship in Myanmar since the introduction of the Citizenship Law in 1982 (United Nations Action for Cooperation Against Trafficking in Persons (UN-ACT), Citation2014) and they became stateless. As a result, “[t]he Rohingya’s lack of citizenship became the anchor for an entire framework of discriminatory laws and practices that laid the context for coming decades of abuse and exploitation” (Equal Rights Trust, Citation2014, p. 23). Rohingyas became the victims of these discriminatory laws and practices. As a result of displacement and living in refugee camps, Rohingya children are in dreadful need of humanitarian assistance and protection including food, shelter and medicine.

To avoid brutal oppression, discrimination, violence, torture, unjust prosecution, murder and extreme poverty for decades, this ethnic minority fled from their homes and sought refuge in neighbouring Bangladesh and other countries (UNHCR, Citation2012). Although Myanmar shares borders with five countries (Bangladesh, China, India, Laos and Thailand), Rohingyas are found across the world as refugees including in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Malaysia and Indonesia where they arrived mostly by sea. Many of them have crossed more than one international border in search of a secure life (Amnesty International, Citation2017). This Rohingya refugee crisis is one of the most significant ongoing humanitarian emergencies in recent history (Milton et al., Citation2017). It has also created substantial development challenges for Bangladesh to support these refugees while struggling with other domestic political and development issues (UNDP, Citation2018).

Statelessness poses one of the most complex problems both in terms of humanitarian intervention and for the creation and implementation of legal protection for the people who suffer most from the manmade threat and crime against humanity (Barash, Citation2000). By its very nature, statelessness challenges the citizen–state relationship of the contemporary state model in which provisions for formal membership either through nationality or citizenship laws are the state’s prerogative, and international norms and commitments are largely effected through the enactment and implementation of laws, policies, and practices at the state level (Goris, Harrington, & Kohn, Citation2009). Indeed, “the very notion of statelessness exposes the essential weakness of a political system that relies on the state to act as the principal guarantor of human rights” (Blitz, Citation2009, p. 7–8).

Statelessness has serious consequences for people, especially for children, regardless of their geographical locations. They have difficulties to get most of their basic human rights including food, clothes, housing, education, healthcare, and vaccinations to protect them from communicable diseases, and freedom of movement. Without being able to fulfil these basic needs, they can face lifelong obstacles and become frustrated at not having the opportunity to unlock their potential as human beings. Due to discriminatory law, Rohingya children born after the 1982 Citizenship Law automatically become stateless, which has detrimentally impacted their well-being and personal development. Since 2012, countless Rohingya children have died in the internally and externally displaced camps from malnutrition and diseases (Lewa, Citation2009; Thevathasan, Citation2014). This article focuses only on the issues of externally displaced Rohingya children living in refugee camps in Bangladesh and especially on their access to education, specified as a human right to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (UN General Assembly, Citation2015; UNESCO, Citation2016)).

Methodology

This article is based on existing literature including both academic and grey literature. Grey literature provides materials of different written formats that are very important for understanding ongoing and historical development of a particular issue and cannot be retrieved through traditional or commercial publishing and distributing channels, indexing or database (Frater, Myohanen, Taylor, & Keith, Citation2007; McKimmie & Szurmak, Citation2002; Pappas & Williams, Citation2011). Even though grey literature is a useful source of material, this article acknowledges the potential problems with certain types of such literature as a source of knowledge. Such problems may include: (a) identifying the authors of ‘grey literature, (b) frequent lack of satisfactory bibliographical standards, and (c) credibility and quality of evidence. Still, in areas of knowledge where more academic publications are lacking, grey literature can provide access to local knowledge around problems that fly under the radar of more established publication channels. As the author of this article, I am aware of these problems, and have exercised judgement on the credibility and reliability of the grey literature used as part of this review.

In this review, grey literature such as reports, working and conference papers, newsletter articles, government documents, and agency documents were included. A systematic approach (Jesson, Matheson, & Lacey, Citation2011) was followed to carry out literature searches using ‘Google’, ‘Google Scholar’, ‘Mendeley’ ‘Social Science Research Network’and ‘Research Gate’ to collect available documents on the Rohingya crisis. To explore the Rohingya crisis and its impact on externally displaced Rohingya children who are living in refugee camps in Bangladesh, the relevant key words, i.e. ‘Rohingya’, ‘Refugee’, ‘Children’, ‘Education’ and ‘Bangladesh’ were used for searching the existing literature. Using the search engines mentioned, both freely available academic and non-academic published and unpublished documents written in English were collected. Finally, selected literature was explored to analyse secondary data and complete the review.

Recent influx of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh

For more than two decades Bangladesh has faced a recurrent influx of Rohingya refugees involving more than 300,000 people. However, a recent influx of 74,000 was added in 2016 (IOM, Citation2017a, Citation2017b) and the latest influx of 655,500 since 25 August 2017 (ISCG, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; UNICEF, Citation2018). As of 30 September 2018, the size of the Rohingya refugee population in Bangladesh is 895,631, and 55% of this population is children (UNHCR, Citation2018). At the end of March 2019, according to OCHA (Citation2019: Online), “over 909,000 stateless Rohingya refugees reside in Ukhiya and Teknaf Upazilas. The vast majority live in 34 extremely congested camps, including the largest single site, the Kutupalong-Balukhali Expansion Site, which is host to approximately 626,500 Rohingya refugees”.

The needs of Rohingya refugees, both previous and new arrivals, are enormous and crucial and include basic human needs for their health and well-being (i.e. food, shelter, day to day consumables, safe drinking water, hygiene items, gender-sensitive sanitation, medicine and mental health care including psychological support as they have gone through traumatic experiences) as well as education (ISCG, Citation2018b, Citation2018d). Among the latest influx of refugees are many children who made the journey with traumatic experiences and memories, living in overcrowded makeshift camps exhausted and battling with diseases and lack of nutrition (UNICEF & UNHCR, Citation2018). Especially for children, child protection interventions are essential as they are at risk of separation, trafficking and exploitation as child labour as well as being denied their right to schooling (Save the Children, Citation2018a). In refugee camps, Rohingya children have very limited access to education and are often in extremely poor health due to lack of food, health services, medicines and sanitation. Children, especially girls, are exceptionally vulnerable to violence and trafficking, both for sex and for manual work (CODEC et al., Citation2017; Save the Children, Citation2018a, Citation2018b).

According to ISCG (Citation2017b), the needs of the response against the Humanitarian Response Plan are as follows:

100% of the population require food assistance

564,000 people need nutrition assistance, including new and previous arrivals and the host community

120,000 pregnant and lactating women need nutrition support

Over 62,000 children under 5 require treatment for malnutrition

The total estimated gap in immediate WASH services is 433,924 people

Food, shelter, health, wellbeing, safeguarding and education are the key concerns for displaced Rohingya children (Save the Children, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). To address issues related to their childhood development and human rights (Save the Children International, World Vision, Plan International, Citation2018), the international community has an ethical obligation to support these stateless displaced vulnerable children as there are significant concerns about the conditions for returning home and the willingness of displaced Rohingyas to go back to Myanmar (Save the Children, Citation2018b). Therefore, concern was raised that “the international community must work together to protect the rights of Rohingya children on the move by implementing policies and programs that vigorously address harm prevention by improving the situation” (Harvard Center for Health and Human Rights, Citation2016). There are calls for the international community including UN and neighbouring countries to work together in order to put pressure on the Government of Myanmar for a permanent solution for ending the conflict, taking back the Rohingyas and building peace with the Rakhine State so that ethnic minorities can live in harmony (The Daily Star, Citation2017; United Nation, Citation2017).

In recent time, Bangladesh has been facing enormous challenges of dealing with an influx of Rohingya refugees mostly living in camps where education, mental health and wellbeing including nutrition are huge concerns. They are living in very miserable conditions which invariably affects their physical, mental and social well-being. Though minimal local and global supports exist to help them, the data suggest, as of 10 November 2017, no funding was allocated for providing education to displaced refugee children, and only 5.5% of refugees came under health care provisions. However, Bangladesh faces a significant challenge to accommodate the refugees in Bangladesh as well as to create international pressure on the Government of Myanmar to arrange their safe return to their homes in Rakhine state. The sudden influx of Rohingya people in Bangladesh appears to have caused adverse effects at the economic, social, political and environmental levels of Bangladesh which is evident in recent studies (Ahmed et al., Citation2018; László, Citation2018).

As the host communities in Bangladesh are struggling to accommodate the flow of Rohingya refugees, they need humanitarian support too. The situation is further compounded by the increasing displaced population, adversely affecting the security of food and nutrition, and impacting the local economy by introducing a labour surplus which has driven day labour wages down, and an increase in the price of basic food and non-food items. Further increases in population and density of the people have affected the basic road and market infrastructure that exists, resulting in the need to build up services, with congestion already a major problem that is limiting access and mobility around large sites (IOM, Citation2017b).

For instance, Cox’s Bazar, a district of Bangladesh where most of the Rohingya refugees are based, has a population of 2,290,000 predominantly Muslims BangladeshisFootnote1. It is one of the poorest and most vulnerable districts of the country, with malnutrition and food insecurity at chronic moderate levels, and poverty well above the national average. The residents of this district suffer from a gap in food consumption quality as 72% of the children do not have a sufficiently diverse diet, and 63% of the women eat less than five food groups. The food consumption by 12% of the residents of this district is considered as poor and borderline. On average 33% and 17%, respectively, live below the poverty and extreme poverty lines. In relation to education, the primary school completion rate for Cox’s Bazar is 54.8%, against the divisional and country level rate of about 80%. The drop-out rate for Cox’s Bazar is 45% for boys and 30% for girls (Save the Children, Citation2018b). That means the host district is a deprived one and the presence of large numbers of Rohingya refugees has a significant impact on socio-economic, cultural, educational and environmental aspects of the host communities.

In the Cox’s Bazar district, schools and school communities have been heavily impacted especially by the recent post-August 25 influx. Cox’s Bazar is among the lowest performing districts in the country with many issues related to access, retention and achievement. Development workers are well placed to partner with the local school system in co-curricular activities, like sports, provision of libraries, and promoting reading campaigns, as well WASH interventions where required, in collaboration with the District Primary Education Officer. These must, of necessity, be visible and useful and contribute to core education activities.

There are further pre-existing or potential risks affecting both refugee and host populations. The magnitude of the relief operations reaching the camps and makeshift settlements creates a sense of deprivation amongst the local population and may fuel tensions between both communities. The poor living conditions and a lack of access to education and sustainable futures may increase the risk of falling back on negative coping mechanisms, or of radicalisation. High levels of criminality in the district are closely linked to the settlement economies, particularly drug and human trafficking. The district is highly vulnerable to shocks, in an extremely fragile environment which has annual cyclone and monsoon seasons (IOM, Citation2017b).

Education in emergencies

Education in emergencies is based on the concept of “education as humanitarian response” (Retamal & Aedo-Richmond, Citation1998; Kagawa, Citation2005; Sinclair, Citation2006). According to the Save the Children Alliance Education Group (2001), education in emergencies means, “education that protects the well-being, fosters learning opportunities, and nurtures the overall development (social, emotional, cognitive, and physical) of children affected by conflicts and disasters” (Sinclair, Citation2002, p. 23; Kamel, Citation2006, p. 4). Therefore, education in emergencies could be defined as education which is provided during the times of crisis created by conflicts or disasters. Any conflict or disast destabilises, disorganises or destroys the existing education system, and require an integrated process of crisis and post-crisis assistance (UNESCO, Citation1999). It “increasingly serves as shorthand for schooling and other organised studies, together with ‘normalising’ structured activities, arranged for and with children, young people and adults whose lives have been disrupted by conflict and major natural disasters” (Sinclair, Citation2001, p. 4). However, the growing interest and importance of providing education in emergencies to those who are in need has implications on financial support and programme design (Burde, Kapit, Wahl, Guven, & Skarpeteig, Citation2017). But Sinclair (Citation2001, p. 1) clearly emphasises that “[e]ducation should support durable solutions and should normally be based on the curriculum and languages of study of the area of origin. Survival and peace-building messages and skills should be incorporated in formal and non-formal education. Programmes must progressively promote the participation of under-represented groups, including girls, adolescents and persons with disability”. These have obvious implications for the displaced Rohingya children living in the refugee camps in Bangladesh.

According to UNESCO (Citation2002, p. 11), the rationales of the educational responses in emergencies by providing humanitarian assistance as follows:

Education helps meet the psychological needs of children affected by conflicts or disasters which disrupts their lives and social networks.

Education is a tool for protecting and safeguarding children in emergencies as they are extremely vulnerable in situations.

Education provides a channel for conveying health and survival messages as well as tools and techniques for teaching new skills and values, such as peace, tolerance, conflict resolutions etc.

Education for All (EFA) is a tool for social cohesion, whereas educational discrepancies lead to poverty for the uneducated and fuel civil conflict.

Education is vital to the reconstruction of the socio-economic and cultural basis of family, local and national life and for sustainable development and peacebuilding.

From the above rationales, it is paramount that displaced Rohingya children should get necessary assistance for education in emergencies and humanitarian assistance to ensure their human rights (Prodip & Garnett, Citation2019).

Within the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to achieve by 2030, education in emergencies supports and incorporates the wider goals of the inclusion of refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs) and stateless persons in regular developing planning (Overseas Development Institute, Citation2017). The 2030 Agenda for SDGs directly or indirectly addresses the issues of migration and migrants, including migrants’ contributions to sustainable development and their need for migration in conditions of safety and respect for their fundamental rights. Several of the targets under the SDGs are devoted specifically to migrant issues, while others cannot be achieved without the inclusion of migrants:

No poverty (SDG 1): End poverty in all its forms everywhere. Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floods, and by 2030, this goal aims to achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable.

Zero hunger (SDG 2): End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture. By 2030, this goal aims to end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round.

Good health and wellbeing (SDG 3): Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages. By 2030, this goal aims to end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases.

Quality education (SDG 4): Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. By 2030, this goal aims to ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and equality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes. By 2030, this goal aims to ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education. By 2030, this goal aims to eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situation. By 2030, this goal aims to ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development. Build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive and provide safe, non-violent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all.

Decent work and economic growth (SDG 8): Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all. Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments of all workers, including migrant workers, particularly women migrants, and those in precarious employment.

Reduced inequalities (SDG 10): Covers several different types of social and economic inequalities which looks at overall levels of economic inequality including disparities of income and wealth between individuals and households in society but also at social inequalities and exclusion of particular groups such as women, migrants or ethnic minorities.

Peace, justice and strong institutions (SDG 16): Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.

Partnerships for the goals (SDG 17): Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the global partnership for sustainable development. By 2020, this goal aims to enhance capacity-building support to developing countries, including LDCs and SIDs, to increase significantly the availability of high-quality, timely and reliable data disaggregated by income, gender, age, race, ethnicity, migratory status, disability, geographic location and other characteristics relevant in national contexts.

International migration is included in specific targets i.e. targets 8.8, 10.7 and 17.18 and is implied in many other targets i.e. targets with universal aims including 1.3, 2.1, 3.3, 3.7 and 3.8. However, migrants can also contribute to the achievement of other goals. The reference to migration in the SDGs focus on the importance of the contributions of migrants and their need to migrate in conditions of safety and respect for their fundamental rights (UN Economic and Social Council, Citation2017). Education is a fundamental human right and highlighted in SDG 4 where targets 4.1, 4.2, 4.5, 4.7 and 4A are directly linked to universal aims of providing access to education for children.

Rohingya children and education: context and problems

Displaced Rohingya children’s education in Rakhine State, Myanmar

According to 2009–2010 statistics, Rakhine state had the lowest pre-school attendance among children aged 3 to 5 years old in Myanmar which is 5% compared to the national average of 23% (UNICEF, Citation2013). A similar trend can be observed for primary school enrolment rates where 29% of primary school-aged children were not enrolled compare to the national average of 12%.

In this state, all communities including Rohingya community have barriers for accessing to education due to a shortage of schools and learning materials, distance from home to school, and lack of finance to support education system (UNICEF, Citation2013). However, Rohingya girls tend to drop out of school once they reach puberty to avoid mixing with men and to contribute to home-making instead (Save the Children, Citation2017).

Existing data and initial rapid assessmentFootnote2 (Save the Children, Citation2018a) suggest that either a large proportion of Rohingya refugee children were not schooled in Rakhine State or they did not have access to accredited formal quality education before seeking refuge in Bangladesh. It is known that many children attended schools in Northern Rakhine State, mainly in community-owned schools (which follow the Myanmar National Curriculum) and MadrasasFootnote3 (which provide basic religious education for Muslims). However, there is a lack of data on the children’s educational attainment or competency level (ISCG, Citation2017b). Against a background of communal conflict and sectarian violence, worries about safety and security have also been a reason not to engage in the formal education system where schools are distant from homes.

Most of the post-August 2017 Rohingya refugees came from the northern part of Rakhine State where Teacher–Student ratio is well above the national target 30:1 set out by the Ministry of Education, Myanmar because of low enrolment in schools. This is due to security and safety issues in this region. One of the reasons for teachers’ absenteeism in Maungdaw is also related to security issue in the area. As a result, a parallel community-based schooling system was developed using volunteers from the communities with the basic education infrastructure. These volunteer teachers who are paid by the community are not qualified and among them 83% have at least 10 years of school or higher (REACH, Citation2015).

Access to education for displaced Rohingya refugee children in Bangladesh

In the refugee camps in Bangladesh, Temporary Learning Centres (TLCs) run by Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) provide some basic education for children up to the age of 14. There are also NGO-run Child Friendly Spaces (CFSs) which try to provide early schooling along with games. Mosques run by the Rohingya community provide religious education to children up to a certain age. NGOs recruit both Bangladeshi and Rohingya people (as volunteers) to run the temporary learning centres. There is no scope for continuing education for those who attended school in Myanmar. In these learning centres, the allowed languages are English, Burmese and Arabic (for religious education).

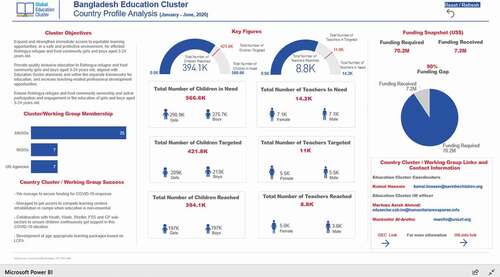

Until 2015, there was no approved provision of education for Rohingya refugee children based in Bangladesh. Then in 2015, the government of Bangladesh agreed that nonformal basic education could be provided to Rohingya children in their makeshift settlements. UN agencies and a limited number of international and national NGOs were allowed to establish and run their temporary learning centres. As a result, a small number of registered Rohingya refugee children got access to nonformal basic education provided by UNHCR and its partner NGOs. This learning experience was not accredited and therefore, there was no further opportunity for them to continue their education either in the mainstream local Bangladeshi schools or within the camps. However, since August 2017, access to quality education in emergencies for Rohingya children became particularly challenging and a concern for the international community (). On the one hand, because of the influx of Rohingya refugees, existing temporary learning centres in makeshift settlements failed to cope with the increasing number of children. On the other hand, not all spontaneously built settlements have learning space or child-friendly facilities to provide access to basic education for displaced children (Save the Children, Citation2018b).

Figure 1. Key figures and funding snapshot to provide access to education for Rohingya children in Bangladesh. Sources: Global Education Cluster, Bangladesh Education Cluster Country Profile Analysis (January - June, 2020). Retrieved from https://www.educationcluster.net/node/121 and accessed on 18 September 2020.

Lack of physical space and challenge in obtaining government approval to operate for Education SectorFootnote4 partner NGOs outside UN agencies has hampered the scaling-up of the Education response. Five months into the response to the Rohingya refugee influx in August 2017, the Education Sector Group partner NGOs reached 24,000 children. Around 625,000 children and young people (ages 3–24) comprising over 50% of the different refugee and host community demographic groups still need access to learning opportunities. More than 3000 temporary learning centres were needed to reach the 370,000 children targeted by the initial six-month Humanitarian Response Plan. In January 2018, camp managers and site planners announced that due to the lack of space no additional Temporary Learning Centre could be built. As a result, the Education Sector partner NGOs are exploring alternatives for education in emergencies delivery options including using existing religious education spaces called Madrasas and community centres, mobile libraries, radio education, self-learning kits, parent literacy techniques etc. (ISCG, Citation2017b).

As outlined by ISCG (Citation2018a), there are targets to be met to support displaced Rohingya children living in Bangladesh. Within the new Humanitarian Response Strategy (March–December 2018), they have prioritised that the Education Sector should meet the needs of 230,000 children and young people (50% girls) aged 3–24 years, including 43,000 teachers and community members, through a two-phase approach.

Challenges and threats of using different materials and languages

Children learn in many ways and to enrich their learning experiences, they need to have access to a variety of different materials that help them to make sense of their world including learning materials in different languages. The government of Bangladesh has put restrictions on using the Bangladeshi school curriculum and Bangla language as a medium of instruction. As a result, it is particularly difficult to source low-cost, relevant and well-conceived learning materials to provide quality basic education for Rohingya refugee children in their mother tongue.

The largely non-written nature of the Rohingya (also known as Arakani) language considerably limits Mother-Tongue-based Multi-Lingual Education (MTB-MLE). However, as Chittagonian, the prevalent local dialect in Cox’s Bazar district, has some similarities with Rohingya language, local and refugee teachers in the temporary learning centres can use a combination of Chittagonian and Rohingya as the medium of instruction. Few Bangladeshi and Rohingya teachers have Burmese language competency and therefore, teaching Rohingya children through the Burmese language presents the highest challenge for providing access to education.

Conflict of interests between the Government wings

While the Ministry of Education (MoE) in Bangladesh is more open to education provision for Rohingya children, the NGO Affairs Bureau, a government department which monitors and authorises the activities of NGOs and other development agencies, does not recognise play-based informal learning activities in the camps. The process of approving Foreign Donations (FDsFootnote5) for the Rohingya crisis remains bureaucratic and slow for all actors but is consistently more challenging for the Education Sector Group partner NGOs. There have been several instances where the NGO Affairs Bureau rejected foreign donation forms (FDs) due to the inclusion of education activities. The temporary learning centres had to be relabelled as “Child Play Areas” and teachers had to be called “facilitators”.

Challenges to approve the curriculum and recognition of education

Providing quality education in emergencies and ensuring educational continuity for the Rohingya refugee children is also challenging due to the lack of an agreed and approved curriculum, the limitations on teacher supply and qualifications or any form of accreditation of prior learning, lack of certification or information on children’s previous educational attainment, and restrictions on using Bangla language. To teach 37,000 Rohingya children aged 4–18 targeted by the Humanitarian Response Plan (September 2017-February 2018), around 6,000 teachers were urgently needed. Four months into the response, only 385 teachers were recruited and trained using an adapted version of the INEE Training Pack for Primary School Teachers in Crisis Contexts. As most of the refugees and local teachers have limited qualifications and teaching experience, there is a critical need for more professional development opportunities, including further training in pedagogy, subject matter instruction, language and life skills along with on-going supportive supervision (ISCG, Citation2017b).

Heterogeneity of temporary learning centres’ learners and high teacher-child ratio

As teacher-student ratio is high, teachers also have to teach a large number of children, with varying education backgrounds and competency levels. Children were enrolled in the temporary learning centres based on their age. As a result, cohorts in the temporary learning centres present a diversity of educational background and learning levels and academic abilities. A large number of children and their varying learning needs make it almost impossible for teachers to teach them within the same learning settings. Assessment of students’ core competencies level is required to identify the children’s educational needs, set up more homogeneous cohorts and facilitate learner-centred teaching and learning approaches.

Vulnerability, safeguarding and gender-sensitive learning environment

Rohingya refugees, especially displaced children, are extremely vulnerable (Child Protection Working Group, Citation2012). Child labourers, children with disabilities, and child-headed households have been identified as key vulnerable groups. Providing targeted support including mainstreaming disability in education programming and ensuring flexible learning models is key to prevent some from turning to child labour or early marriage as negative coping mechanisms (ISCG, Citation2018b). In addition, mechanisms for exiting protection and support systems for the reintegration of children in crisis are very weak (Nayagam, Citation2012).

It was estimated that 19% of households were headed by women who lost their husbands in violence in Myanmar or in the journey in search of refuge. 11% of households were headed by elderly persons and 5% headed by children (IOM, Citation2017b). The lack of identity documentation or legal status hinders access to the justice system, legal work opportunities, formal education systems and other public services in the host communities (Farzana, Citation2016). A significant number of girls and women who are survivors of rape in Myanmar live with traumatic experiences. Violence against females is prevalent as they are targeted for a range of abuses linked to hardships and as the fact that they have to depend on others for their basic needs. Among the children, many of them were separated from their families and are living without guardians or carers as well as with little or no access to education (IOM, Citation2017a and IOM, Citation2017b).

A recent assessment indicated between 73 and 95% illiteracy among the Rohingya communities based in Cox’s Bazar (ISCG, Citation2017b). Far fewer adolescent girls than boys attend learning spaces in the new campsites and makeshift settlements. Socio-cultural barriers combined with safety concerns, economic factors, and supply-related issues (e.g. lack of education facilities and gender-segregated latrines) are hampering access to education for girls amongst the Rohingya and host communities alike. The vast majority of Rohingya girls do not attend school beyond Grade 5, and by the time they reach puberty, parents limit their participation in the public sphere due to norms around being unmarried girls and helping with domestic work.

Government’s political position

After 25 August 2017, the government of Bangladesh has increased its monitoring of foreign aid agencies, with a particular focus on sectors such as education (Dhaka Tribune, Citation2017; The Globe Post, Citation2019). The government sees any long-term education provision as weakening its negotiating position for repatriating Rohingya refugees to Myanmar. The government of Bangladesh does not want the newly arrived Rohingya to settle long-term and will, therefore, not allow integration with the wider host population – including permitting Rohingya children to enter the formal education system of Bangladesh (The Daily Star, Citation2018). No Rohingya children are entitled to enrol in Government accredited schools, nor can they sit for the Primary School Certificate (PSC) exam (the public exam which marks the completion of primary education in Bangladesh). Recently, however, the Bangladesh government agreed to allow 10,000 Rohingya children to enrol in a pilot project for starting formal education from Grade 6 to 9 through the Myanmar school curriculum assisted by UNICEF (The Daily Star, Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

Before the August 2017 influx, lessons of the temporary learning centres in the registered refugee camps were conducted in Bangla, and a nonformal education curriculum framework approved by the government of Bangladesh, covering Grade 1 to 7 and fused with Myanmar education, was used. However, refugee children’s educational achievements were not validated either by Bangladesh or by Myanmar, and the education provided in the camp was not accredited by anybody. Bangladesh Government policy now strictly bans the use of the Bangla language and Bangladeshi national curriculum in the learning centres and play spaces. It requires the education providers to use Rohingya (also known as Arakani), Burmese and English as the medium of instruction for Rohingya children (Save the Children, Citation2017).

New initiative called learning competency framework and approach (LCFA)

In October 2017, an informal technical working group was formed comprising representatives from UNICEF, UNHCR, Plan, Save the Children, BRAC and technical curriculum experts from Bangladesh and Myanmar, to develop a learning framework as an alternative curriculum for Rohingya refugee children (BRAC, Community Development Centre and DAM, Citation2018). In consultation with the government of Bangladesh, the working group organised two workshops in November and December 2017 to draft the framework. The draft learning framework was presented at a local level to the Education Sector Group at Cox’s Bazar, and consultations with teachers, frontline responders and the Rohingya children’s parents took place in January 2018 in the camps to validate and improve the framework further. To ensure children’s views were included, INGOs conducted consultations with children in the temporary learning centres. Based on the findings and recommendations from these consultations, the draft learning framework has been revised and shared with relevant government offices for their review and endorsement (Technical Working Group, Citation2019).

Agreed and approved package of education

The lack of an agreed and approved learning package for Rohingya children, as well as critical issues around language of instruction, need to be addressed through quality teaching and learning that is relevant and socio-culturally and economically appropriate for refugee children, and aligned with standards from the Ministry of Education (MoE), Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MoPE), NGO Affairs Bureau and the aid agencies (local, national and international). The Ministry of Education, with technical assistance from UNICEF, has launched an initiative to develop the learning framework mentioned above and relevant teaching and learning materials for early years education (pre-school to Grade 7).

Discussion

Expansion of learning opportunities and flexible learning models

An approved educational framework and support systems to improve the standardised education programmes for the displace Rohingya children are urgently needed. An initial response would focus on expanding and improving existing learning opportunities so that equitable access could be ensured for both refugees and host communities. The support initiatives could be further strengthened by standardising the education in emergencies responses and providing psycho-social support for the new as well as previous arrivals (UNESCO, Citation2015). Learning opportunities and facilities need to be scaled up to enable more Rohingya children and young people, particularly the new influx, to exercise their rights to education. Innovative education delivery methods could be incorporated, and inter-sectoral collaboration should be encouraged to increase the effectiveness of available resources, such as using temporary learning centres as multifunctional spaces and integrating learning in other facilities for children in response to congestion and land availability problems (Lerch & Buckner, Citation2018). Within the learning centres, flexible learning models would provide safe and inclusive environments, and quality interventions for effective learning and teaching could be a key strategy going forward. Innovative strategies such as e-learning will ensure vulnerable groups have access to meet their learning needs, especially for adolescent girls, child labourers, children with disabilities and child-headed households. As more than 52% of newly arrived refugee children and young people are girls and considering the high drop-out rate among girls, an improved gender-inclusivity and targeted interventions are needed for empowering adolescent girls. This includes creating a safe learning environment, ensuring access to education facilities including gender-sensitive premises, recruiting female teachers and linking to cash-based interventions and Menstrual Hygiene Management.

Improving quality of education and teachers as well as issues related to curricula and language provisions

The quality of education must be improved by developing teaching and learning strategies that are tailored to the varying needs of the displaced Rohingya children and children from the host communities, as well as promoting durable solutions through advocacy and cooperation with education authorities. Communities must be involved in overseeing student enrolment, retention and attendance, ensuring participation as well as encouraging parental engagement in children’s education (Sinclair, Citation2006). Considering the lack of teaching staff, retention and capacity development of both local teachers and learning facilitators need to be addressed through supportive close supervision and provision of professional development opportunities such as specific training in pedagogy, subject-based instruction, and life skills. Sports, recreational activities, and life skills training could be integrated into the curricula by focusing on community development as well as building individual capacities, with a special focus on pre-adolescent boys and girls, to promote social cohesion and build resilience. As Rohingyas have their own language, Rohingya children should be taught in their own mother tongue as well as in Burmese as their national language (Sinclair, Citation2002). With respect to the teaching of Rohingya language, the development organisations which provide education in the refugee camps in Bangladesh could facilitate intra-Rohingya discussions on the best script and language base to use in their education programmes for Rohingya children. The inputs and decisions of speakers of the Rohingya (also known as Arakani) language are critical to making any decision on the medium of instruction so that conflict of interests could be minimised, and the politics of language policy could help to rebuild trust and peace in the region.

Related non-education issues – health and income

Only 46% of Rohingya refugee children are receiving psycho-social support which shows that significant progress is needed to improve these vulnerable children’s mental health and wellbeing through the process of education (ISCG, Citation2018a). It is essential to develop a framework to provide better understanding of health and wellbeing through education. Rohingya children living in the refugee camps in Bangladesh are in need of flexible health service delivery, emergency healthcare and mental health interventions integrated with their education programmes (Riley, Varner, Ventevogel, Hasan, & Welton-Mitchell, Citation2017). Low levels of household income force Rohingya children to engage in income-generating activities or domestic work to support the family rather going for education (Crabtree, Citation2010). Therefore, income generation training could be part of a formal education programme, or specific vocational education and training (VET) could be more attractive and effective in helping to ensure a sustainable livelihood for these youngsters. Dedicated programmes should be developed and implemented, focusing on life skills, vocational training, and basic literacy and numeracy based in real-world requirements (setting up micro-enterprises, family-based production of food and non-food items, access to e-knowledge networks) to optimise family outcomes in terms of income and social well-being. Such a strategy could significantly improve knowledge and skills and reduce the tendency to resort to negative coping mechanisms. This kind of interventions could benefit about 20% of young people between ages 15 to 24 among refugees and host communities (ISCG, Citation2018a).

Dealing with coordination of agencies and the need for policy clarity and consistency

In line with Government policies, Education Sector partners NGOs need to be more transparent so that their foreign donations (FDs) will not be rejected. For engaging Rohingya children in formal education, it is essential to start robust adult education projects with more vocational education and training for 16 to 24 years old. These education programmes could be undertaken using a variety of delivery methods, i.e. digital, face to face, peer to peer and group activities through games and sports for individual development (UNESCO, Citation2015). The design, development and delivery of these programmes would ensure that young refugees can use these to acquire the necessary skills that are pathways to productive engagement and future aspirations. In the design of these progammes, critical thinking, problem solving, and empathy need to become strong elements. Given the social norms currently prevalent among the Rohingya, it is critical to ensure that girls and young women are especially targeted in planning these programmes so that they can be motivated and empowered and become self-dependent.

Synergies in interventions and the role of development organisations

At this stage in the response of the Rohingya crisis as a long-term historical issue, the activities of the development organisations working as the partners of Education Sector need to be ramped up, and discussions with the government of Bangladesh taken forward to achieve greater policy clarity in line with the provisions of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, where state parties are responsible for the education of children in their jurisdiction, regardless of their immigration status. At the same time, both bilateral and other development partners must ensure that the Cox’s Bazar district features robustly in the development planning of education for Rohingya children in refugee camps. According to ISCG (Citation2018a) data, only 25% of the total estimated budget to cover the need of the education sector has been funded. To bring all the children aged 4 to 14 to basic education, there is a huge need for funding to achieve the humanitarian response target for the Rohingya children. For expanding current learning facilities i.e. Temporary Learning Centres (TLCs) and Child Friendly Spaces (CFSs) to provide access to nonformal learning, there is a need to find the funding and partners to expand the current service delivery network (Cox’s Bazar Education Sector, Citation2018). Synergies in multi-sectoral interventions should be explored to ensure they complement the efforts to build family capacities to achieve greater self-reliance through the acquisition of livelihood skills and soft skills. Under the reality of uncertainty, it is essential to assist development workers to support Rohingya refugee children in need.

Academic connection, cooperation and collaboration

There is a lack of academic skills and expertise to carry out interdisciplinary research to solve the global challenges of migration and refugee crisis. As suggested in the grey literature, there is a need for livelihoods-related social protection and safety-net schemes for vulnerable refugee children as well as support for their hosting communities. The outcomes of any research or any intervention collaboration in these areas will better inform development workers and academic practitioners to design, develop and implement their intervention programmes on the ground. Academic collaboration and research can assist practitioners to work effectively to support Rohingya refugee children to have a better childhood. Therefore, interdisciplinary research activities should be in place to assist to develop a holistic framework which could be adopted by the GOs and NGOs together to support the displaced Rohingya children for their education, mental health and wellbeing in refugee camps situated in Bangladesh. Based on a research-based framework, they can work effectively and efficiently in practice to bring changes in the lives of displaced Rohingya children.

Academics from Bangladesh and Myanmar, along with academics from other countries, need to be engaged in dialogue and research in order to contribute towards achieving SDGs for both countries. In this process, they should address the issues of migration and the refugee crisis, which have a significant negative impact on socio-economic and ecological development. Opportunities need to be created to carry out research by bringing together a novel combination of disciplines to effectively inform thinking on human rights and social justice as prompted by the situation of the Rohingya people. Therefore, academic researchers must be engaged in developing ideas and exchange their expertise so that research-informed policy and practice could be in place to tackle the current as well as future predicted and unpredicted development challenges for both Bangladesh and Myanmar. Thus, interdisciplinary research networks might help to enhance impacts on aid assistance and development practice on the ground.

Considering the fluid and chaotic life in camps and settlements, a set of cross-sectoral interventions is critical to reducing the risks of trafficking, drug abuse, early marriage, and hazardous and exploitative work. Furthermore, given the gender norms, there is also a need to ensure that girls and young women can participate in the learning process as learners and facilitators through targeted approaches (Talbot, Citation2013). Within a framework developed through research, these refugee children could be educated with fundamental health education as well as trained with skills to engage with income generation activities so that they can become independent earners. At the same time, the framework should engage them in a constructive educational process to overcome their difficulties including their experiences of traumatic events and losses of loved ones and the privations of life in camps or temporary shelters, by creating opportunities for them to develop their full potential as human beings. Thus, they will be prepared to be rehabilitated when the time comes for them to return to their home in Myanmar or migrate to a third country.

Conclusion

The world witnessed one of its gravest humanitarian challenges in recent times when images started flooding the media of people fleeing religious persecution in Myanmar and living in economic misery in Bangladesh, left to die in traffickers’ boats in the Andaman Sea and Indian Ocean – people who could not turn back to the country from which they had fled, and whom other Southeast Asian countries that lay on their horizon, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, were turning away. The fundamental moral question for the international community to answer is: Where could these Rohingyas go? Without a legal bond with any state, these stateless people are left vulnerable to a variety of forms of exploitation and abuse, poverty and marginalisation. Human rights and humanitarian protection of these victims of forced migration need to be in place and the international community must act together to be involved in creating pressure on Myanmar. Further, this is the chronicle of the emergence of a homeless community – the relegation of a national group to a stateless existence without basic rights.

In Bangladesh, Rohingyas are living in the camps as refugees or illegal immigrants in different parts of the country often in conditions of extreme poverty, malnutrition and without proper access to shelter (Lewa, Citation2010; Save the Children, Citation2018b). They also do not have work permits to work legally in Bangladesh. Some of them are now compelled to take to the seas in perilous journeys to other Southeast Asian countries in search of a better life. They are now asked to go back to Myanmar from the host countries, but without any promise of citizenship or an end to discrimination. The move to push this stateless vulnerable people to the place where they are not welcomed is, to many observers, completely unacceptable.

Rohingyas, one of the most persecuted minority communities still exist in the tweenty-first century's world without their rights of citizenship. They are stateless and without rights in an era of SDGs where equality, equity and social justice are paramount. The situation of the Rohingya minority has deteriorated dramatically since August 2017 and since then an estimated 640,000 Rohingyas, 378,000 of whom are children, fled to Bangladesh. Despite legal, political and diplomatic challenges and barriers, the Government of Bangladesh, its citizens, Bangladeshi development organisations and local community organisations are trying their best to support Rohingya refugees and their displaced children. Though Bangladesh has experience of providing education in emergencies caused by both man-made and natural disasters (Rahman & Missingham, Citation2018), still more needs to be learned in order to provide assistance and respond to the humanitarian needs of displaced Rohingya children.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

M. Mahruf C. Shohel

Dr M. Mahruf C. Shohel is an academic researcher with special interests in education, childhood studies and international development. He has written extensively on development issues in the Global South and conducted research on disadvantaged children including socioeconomically deprived children, street children, and sex workers’ children. Currently, he is engaged in the fields of education in emergencies, emerging technologies in education, and teaching and learning in higher education.

Notes

1. There are other religious and ethnic minorities including Rakhinese, a group of Rakhine descendants, living in Cox’s Bazar district.

2. Initial Rapid Assessment (IRA) is carried out by the international multi-agency development workers using an assessment tool developed by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Global Health, Nutrition and WASH Clusters in 2006–2009. It is being used in rapid on-set emergencies in the first 72 hours. It aims to enable faster and better multi-sector rapid assessment in the first few days of a sudden-onset crisis in order to guide the initial planning of urgent humanitarian interventions, identify needs for follow up assessments, and inform initial funding decisions. The IRA is designed to be used in the field by team members with relevant general knowledge and experience but without specialised technical expertise in particular sectors (e.g. in health, water, or education programmes). In emergency situations, produced IRA Report is used widely by the development workers in the field.

3. The word “Madrasa” derived from Arabic, which means “School”. In the context of Rohingya communities, madrasas are community-based schools for providing basic literacy and religious education for Muslim children. Although some Arabic texts are used, medium of instruction is mainly Arakani, the mother tongue of Rohingyas.

4. Education Sector is the umbrella term for the joint efforts of NGOs working together in the field of education. It is widely used by the development organisations working in Cox’s Bazar.

5. Acronym FDs is used widely in the NGO sector as any NGO wants to work in Bangladesh needs to register with the Government’s NGO Affairs Bureau under rule 3(1) of the Foreign Donations (Voluntary Activities) Regulation Roles, 1978.

References

- Ahmed, B., Sammonds, O. M., Burns, P., Issa, R., Abubakar, R., & Devakumar, D. (2018). Humanitarian disaster for Rohingya refugees: Impending natural hazards and worsening public health crises. Comment, 6(5), 487–488.

- Amnesty International. (2017). ‘Caged without a roof’: Apartheid in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. London: Author.

- Barash, D. P. (Ed). (2000). Approaches to peace: A reader in peace studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Blitz, B. K. (2009). Statelessness, protection and equality. Oxford: Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford.

- BRAC, Community Development Centre and DAM. (2018). Education capacity self-assessment: Transforming the education humanitarian response of the Rohingya education crisis. Cox’s Bazar: Education Sector.

- Burde, D., Kapit, A., Wahl, R. L., Guven, O., & Skarpeteig, M. I. (2017). Education in emergencies: A review of theory and research. Review of Educational Research, 87(3), 619–658.

- Child Protection Working Group. (2012). Minimum standards for child protection in humanitarian action. New York: UNICEF.

- CODEC, Save the Children International, Tai and UNHCR. (2017). Rapid protection assessment: Bangladesh refugee crisis. Cox’s Bazar: Author.

- Cox’s Bazar Education Sector. (2018). Joint education needs assessment: Rohingya refugee in Cox’s Bazar. Cox’s Bazar: Author.

- Crabtree, K. (2010). Economic challenges and coping mechanism in protracted displacement: A case study of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 5(1), 41–58.

- Dhaka Tribune. (2017, July 19). Militant funding: 17 foreign NGOs under intel surveillance. Dhaka Tribune.

- Dum, J. (2016). Social value, children, and the human right to education. Dilemata, 8(21), 127–149.

- Equal Rights Trust. (2014). Equal only in name: The human rights of stateless Rohingya in Malaysia. London: Author.

- Farzana, K. F. (2016). Voices of the Burmese Rohingya refugees: Everyday politics of survival in refugee camps in Bangladesh. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 24(1), 131–150.

- Frater, J., Myohanen, L., Taylor, E., & Keith, L. (2007). What would you tell me if i said grey literature? Journal of Electronic Resources in Medical Libraries, 4(1–2), 145–153.

- Goris, I., Harrington, J., & Kohn, S. (2009). Statelessness: What it is and why it matters. Forced Migration Review, 32, 4–6.

- Harvard Center for Health and Human Rights. (2016). Children on the move: An urgent human rights and child protection priority. Boston: Francois Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights.

- INEE. (2004). Minimum standards for education in emergencies, chronic crises and early reconstruction. Paris: Author.

- INEE. (2010). Minimum standards for education: Preparedness, response, recovery. New York: Author.

- International Organization for Migration (2017a, April). Bangladesh: Needs and population monitoring report: Undocumented Myanmar Nationals in Teknaf and Ukhia, Cox’s Bazar. Round 2. Dhaka: Author.

- International Organization for Migration. (2017b, October). Bangladesh: Humanitarian response plan- September 2017 to February 2018- Rohingya refugee crisis. Dhaka: Author. Retrieved from https://displacement.iom.int/reports/bangladesh-%E2%80%94-needs-and-population-monitoring-report-2-april-2017.

- Inter-Sector Coordination Group. (2017a, September 7). Influx into Cox’s Bazar: Preliminary response plan. Cox’s Bazar: Author.

- Inter-Sector Coordination Group. (2017b, December 31). Situation report: Rohingya refugee crisis. Cox’s Bazar: ISCG.

- Inter-Sector Coordination Group. (2018a, January 3). ISCG Sector Response Plan – Education. Draft.

- Inter-Sector Coordination Group. (2018b, January 14). ISCG Situation Report: Rohingya Refugee Crisis, Cox’s Bazar.

- Inter-Sector Coordination Group. (2018d, April 26). Situation report: Rohingya refugee crisis. Cox’s Bazar: Inter-Sector Coordination Group.

- Jesson, J., Matheson, L. & Lacey, F. M. (2011). Doing your literature review: traditional and systematic techniques. London: Sage

- Kagawa, F. (2005). Emergency education: A critical review of the field. Comparative Education, 41(4), 487–503.

- Kamel, H. (2006). Early childhood care and education in emergency situations. Paris: UNESCO.

- László, E. L. (2018). The impact of refugees on host contrives: A case study of Bangladesh under the Rohingya Influx (Master’s Thesis). Denmark: Aalborg University.

- Lee, S. E. (2013). Education as a human right in the 21st century. Democracy and Education, 21(1), 1–9.

- Lerch, J. C., & Buckner, E. (2018). From education for peace to education in conflict: Changes in UNESCO discourse, 1945–2015. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 16(1), 27–48.

- Lewa, C. (2009). North Arakan: An Open Prison for the Rohingya. Forced Migration Review, 32, 11.

- Lewa, C. (2010). Unregistered Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh: Crackdown, forced displacement and hunger. Bangkok: The Arakan Project.

- Machel, G. (2001). The impact of war on children. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- McCowan, T. (2013). Education as a human right. London: Bloomsbury.

- McKimmie, T., & Szurmak, J. (2002). Beyond grey literature: How grey questions can drive research. Journal of Agricultural and Food Information, 4(2), 71–79.

- Milton, A. H., Rahman, M., Hussain, S., Jindal, C., Choudhury, S., Akhter, S., … Efird, J. T. (2017). Trapped in statelessness: Rohingya refugees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(8), 942.

- Nayagam, J. (2012). Strengths and weaknesses of the protection mechanism and support system for reintegration of children in conflict with the law. Malaysian Journal on Human Rights, 6, 60–73.

- Overseas Development Institute. (2017). Migration and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. London: Author.

- Pappas, C., & Williams, I. (2011). Grey literature: Its emerging importance. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 11(3), 228–234.

- Prodip, M. A., & Garnett, J. (2019). Emergency education for rohingya refugee children in Bangladesh: An analysis of policies, practices, and limitations. In A. W. Wisemen, L. Damaschke-Deitrick, E. L. Galegher, & M. F. Park (Eds.), Comparative perspectives on refugee youth education: Dreams and realities in educational systems worldwide (pp. 191–219). London: Routledge.

- Rahman, M. I., & Missingham, B. (2018). Education in emergencies: Examining an alternative endeavour in Bangladesh. In R. Chowdhury, M. Sarkar, F. Mojumder, & M. Roshid (Eds.), Engaging in educational research: Revisiting policy and practice in Bangladesh (pp. 65–87). Singapore City: Springer.

- REACH. (2015). Joint education needs assessment, Northern Rakhine State, Myanmar. Châtelaine: Author.

- Retamal, G., & Aedo-Richmond, R. (Eds.). (1998). Education as a humanitarian response. London: UNESCO International Bureau of Education.

- Riley, A., Varner, A., Ventevogel, P., Hasan, M. M. T., & Welton-Mitchell, C. (2017). Daily stressors, trauma exposure, and mental health among stateless Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Transcultural Psychiatry, 554(3), 304–331.

- Save the Children. (2017). Rohingya crisis response strategy 2017-2020. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Author.

- Save the Children. (2018a). BGD rohingya crisis Humanitarian Response situation report: Rohingya 27. Dhaka: Author.

- Save the Children. (2018b). Bangladesh Rohingya response case study. Dhaka: Author.

- Save the Children International, World Vision, Plan International. (2018). Childhood interrupted: Children’s voices from the Rohingya refugee crisis. London: Author.

- Sen, A. (1992). Minimal liberty. Economica, 59(234), 139–159.

- Sen, A. (1993). Capability and well-being. In M. Nussbaum & A. Sen (Eds.), The quality of life (pp. TK–TK). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Sinclair, M. (2001). Education in Emergencies. In J. Crisp, C. Talbot, & D. B. Cipollone (Eds.), Learning for a future: Refugee education in developing countries (pp. 1–83). Geneva: Switzerland. UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 20).

- Sinclair, M. (2002). Planning education in and after emergencies. Paris: UNESCO.

- Sinclair, M. (2006). Education in Emergencies. In Commonwealth Secretariat (Eds.), Commonwealth education partnership 2007 (pp. 52–56). Cambridge, UK: Nexus Strategic Partnerships.

- Talbot, C. (2013). Education in conflict emergencies in light of the post-2015 MDGs and EFA Agendas. NORRAG (Network for international policies and cooperation in education and training). Geneva: Switzerland.

- Technical Working Group (2019). Learning competencies framework and approaches (LCFA) for children of displaced people from Rakhine State, Myanmar in Bangladesh. Revised Draft with Level I to IV, 1 February 2019. Cox's Bazar: Cox's Bazar Education Sector.

- The Daily Star. (2017). Parliament resolve to push Myanmar to take back Rohingya refugees. Retrieved from https://www.thedailystar.net/politics/bangladesh-rohingya-refugee-crisis-parliament-adopt-resolution-united-nations-international-community-push-myanmar-1460767.

- The Daily Star. (2018, December 15). Entire generation denied education. The Daily Star.

- The Daily Star. (2020a, January 28). Bangladesh allows education for Rohingya children. The Daily Star.

- The Daily Star. (2020b, January 29). UN, global community laud Bangladesh’s decision to provide education for Rohingya children. The Daily Star.

- The Globe Post. (2019, September 5). Bangladesh bans two aid agencies from Rohingya refugee camps. The Globe Post.

- Thevathasan, V. (2014). Interview: The Stateless Rohingya. The Diplomat, October 25.

- UN Economic and Social Council. (2017). International Migration, the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development and the global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration. E/ESCAP/GCM/PREP/L.1. Bangkok, Thailand: Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific.

- UN General Assembly (1966, December 16). International covenant on economic, Social and cultural rights (Vol. 993, p. 3). United Nations, Treaty Series. Retrieved fromhttps://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b36c0.html

- UN General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations General Assembly. A/RES/70/1.

- UNCEF & UNHCR. (2018). Rohingya refugee response: Education and child protection in emergencies: Joint Rapid Needs Assessment, 2017. Cox’s Bazar: Education Sector and Child Protection Sub-Sector. Retrieved from http://socialserviceworkforce.org/resources/education-child-protection-emergencies-joint-rapid-needs-assessment-rohingya-refugee.

- UNDP. (2018). Impact of the Rohingya refugee influx on host communities. Dhaka: United Nations Development Programme.

- UNESCO. (1997). The Human right to peace: declaration by the Director-General. Paris, France: UNESCO. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000105530.locale=en

- UNESCO. (1999). The rights to education: An emergency strategy. Paris: Author.

- UNESCO. (2002). Guidelines for education in situations of emergency and crisis: EFA strategic planning. Paris: Author.

- UNESCO. (2015). Education 2030: incheon declaration and framework for action- towards inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning for all. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/ED/ED_new/pdf/FFA-ENG-27Oct15.pdf.

- UNESCO. (2016). Education 2030: Incheon declaration and framework for action for the implementation of sustainable development goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. Paris: Author. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656

- UNHCR. (2012). Rohingya crisis: Children’s experiences in the Rohingya crisis. Preliminary Results. Geneva: Author.

- UNHCR. (2014). Convention relating to the status of stateless persons. Geneva: Author.

- UNHCR. (2015). Emergency handbook: Education in emergencies. Geneva: UNHCR. Retrieved from https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/101908/education-in-emergencies

- UNHCR. (2018). Joint response plan for Rohingya humanitarian crisis. Geneva: Author.

- UNICEF (1989). The United Nations convention on the rights of the child. London: UNICEF.

- UNICEF. (2013). A snapshot of child wellbeing in Rakhine State, Myanmar. Yangon: UNICEF.

- UNICEF (2018). Rohingya children and families desperately need our help. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org.uk/donate/rohingya-refugees/?sissr=1

- United Nation. (2017). Security council presidential statement calls on myanmar to end excessive military force, intercommunal violence in Rakhine State. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/press/en/2017/sc13055.doc.htm

- United Nations Action for Cooperation Against Trafficking in Persons (UN-ACT). (2014). Myanmar’s Citizenship Law 1982. [The Pyithu Hluttaw Law No. 4 of 1982]. Retrieved from http://un-act.org/publication/myanmars-citizenship-law-1982/

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2015). Handbook for emergencies (4th ed.). Geneva: Author. Retrieved from https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/101908/education-in-emergencies

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance (OCHA). (2019). Rohingya Refugee Crisis. Retrieved from https://www.unocha.org/rohingya-refugee-crisis.