ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to generate knowledge about an MTT classroom in a Swedish elementary school and how MTT is positioned as a safe space for translanguaging. By studying a school context as a potential translanguaging space, our focus is mainly on two dimensions of space: the physical, including the material space of MTT, and the social, including safe spaces in MTT. The material is mainly from one selected Kurdish MTT classroom, in the form of field notes from lesson observations, photographs in the classroom interior, video recordings co-created with the MTT teacher. This classroom may be perceived as a space where Kurdish dominates, while being included in a Swedish-dominant school setting. This Kurdish space has borders that are physical and related to the scheduled lesson in the specific classroom. Both students and the teacher pass the door and through this shift language practices. Linguistic landscaping as a method, in combination with the collective reflection between the researcher and teacher, added another dimension to the study of MTT. Schoolscaping made language hierarchies and the language policy of the school concrete and visible.

1. Introduction

Since the 1970s, support for multilingual students in Swedish schools has been organised as part of the state-mandated education policy. The support has been organised mainly through the subject Mother Tongue Tuition (MTT), previously called Home Language Instruction. The subject was introduced in the curriculum in the late 1970s and it includes tuition in all languages other than Swedish used by students in the home setting. MTT is a voluntary school subject, usually offered once a week for smaller groups of students at schools where the dominant language is usually Swedish (see e.g. Hyltenstam & Milani, Citation2012). Even though the concept of mother tongue is problematic in several respects (see Davies, Citation2003; Mills, Citation2004), we will use it in this paper to refer to the specific school subject in the Swedish national curriculum.

The Swedish Education Act (SFS, Citation2010, p. 800) states that all children that use a language other than Swedish at home have the right to attend MTT under certain conditions. These conditions are related to competence and language use (children must use the language at home with at least one parent and have a basic competence in it) and organisation (at least five students in the municipality need to be eligible, and there must be a teacher available). Despite MTT’s long tradition and its inclusion in the national curriculum, previous research (Ganuza & Hedman, Citation2015; Lainio, Citation2012) has highlighted its marginalised position in Swedish schools.

Translanguaging as a theoretical, ideological and pedagogical concept has been developed and examined through several publications during the last few years (see e.g. García, Ibarra Johnson, & Seltzer, Citation2016; Paulsrud, Rosén, Straszer, & Wedin, Citation2017). In this paper, the point of departure is that pedagogical translanguaging implies a plurilingual norm for the ways in which teachers and students communicate, use languages, and live and learn with languages (García & Kleyn, Citation2016). Here, translanguaging encompasses the simultaneous and flexible use of different kinds of linguistic resources, forms, signs and modalities.

The notion of translanguaging space was introduced by Li Wei (Citation2011) to describe both an arena for translanguaging practices and a space created through the process of translanguaging. The concept highlights the transformative dimension of translanguaging, which “creates a social space for the multilingual language user by bringing together different dimensions of their personal history, experience and environment, their attitudes, beliefs and ideology, as well as their cognitive and physical capacity into one coordinated and meaningful performance, which then becomes a lived experience” (Wei, Citation2011, p. 1223).

The notion of safe space refers to places where all learning experiences are recognised and valued, and where students are empowered and supported in many ways to co-construct their learning (Conteh & Brock, Citation2011, p. 358; see also Canagarajah, Citation2013). Canagarajah argues that it is “important for teachers to provide safe spaces in classrooms and schools for students to practice translanguaging” (Citation2011, p. 415). In such a space, students and teachers can use their linguistic repertoires as resources for learning and for expanding their repertoires in creative and playful ways. Therefore, we are interested here in exploring spaces for translanguaging in MTT, in cases where both teachers and students have the potential to use their linguistic repertoires in the otherwise mainly monolingual, Swedish-speaking, school context. By studying a school context as a potential safe space for translanguaging, our focus is mainly on two dimensions of space for translanguaging: the physical, including the material space, and the social space of MTT.

In order to explore the construction of safe spaces for translanguaging, we analyse the linguistic landscape of one MTT classroom to make both physical and social dimensions of the classroom visible. Moreover, in the Swedish context, having another mother tongue than Swedish has been one criteria for the categorization of students as immigrants (Runfors, Citation2009). By using the concept of translanguaging space we problematise the understanding of the MTT classroom as a space for languages and cultures categorised as belonging to the Other (Blackledge et al., Citation2008).

In this paper, the focus is on whether and how MTT is marginalised in the local practice and in what ways MTT may be a safe space for translanguaging with these physical (including material) and social dimensions. In this article we analyse one MTT classroom in a Swedish elementary school as a translanguaging space by using linguistic schoolscaping and observations of MT lessons as an analytical tool. Thus, the aim of the article is to generate knowledge about the MTT classroom and how MTT is positioned as a safe space for translanguaging, focusing on the physical and social dimensions of the MTT classroom.

Although the ideological framework of MTT has been studied earlier (Ganuza & Hedman, Citation2015; Hyltenstam & Milani, Citation2012; Reath Warren, Citation2013) as has the marginalised position of the subject (Spetz, Citation2014), this study contributes new knowledge by exploring spatial aspects of MTT in a Swedish school and how language ideologies are manifested in and through space. Hence, by using schoolscaping as a methodological framework, the study juxtaposes processes of marginalisation and inclusion on a school level in regard to space. By focusing on different dimensions of space in MTT we want to make some aspects of language ideologies visible that may counteract the ambivalence that was revealed by Lainio (Citation2012) between policy and practices regarding MTT.

We start by presenting the socio-political context of MTT in Sweden and the concept of translanguaging space together with the framework of linguistic landscaping. After a section about methodology and material, we present the local context of the study and analyse the MTT classroom as a translanguaging space, first with a focus on the physical (mainly material) spaces, and second, with a focus on the social spaces for translanguaging in its particular school setting. Finally, we present some implications of the study.

2. Mother tongue tuition in Sweden

The number of students in the Swedish school system with language(s) other than Swedish dominating in the home is increasing; in 2017, 27% of all students in compulsory school were eligible for MTT (SNAE, Citation2017a) and 24% had a migration background (SNAE, Citation2017b). However, only 57% of the students eligible for MTT had participated in MTT during the 2016/2017 school year (SNAE, Citation2017c). A number of researchers have stressed the importance of support for students’ home language, first language or mother tongue in school (Cummins, Citation1980, Citation2000; García, Citation2009). One of the most important factors for school success for students whose mother tongues are different from the dominant school language is the availability of MTT or other forms of education where multilingual resources are used for learning (e.g. García, Citation2009).

The right to develop and use one’s mother tongue is stipulated in the Swedish Language Act (see SFS, Citation2009: 600), which states that “persons whose mother tongue is not one of the languages specified in the first paragraph [concerning national minority languages and Swedish Sign Language] are to be given the opportunity to develop and use their mother tongue”.

The aim of MTT as a subject is described in the following way in the Swedish national curriculum (SNAE, Citation2018, p. 86):

Language is the primary tool human beings use for thinking, communicating and learning. Through language, people develop their identity, express their emotions and thoughts, and understand how others feel and think. Rich and varied language is important in being able to understand and function in a society where different cultures, outlooks on life, generations and language all interact. Having access to their mother tongue also facilitates language development and learning in different areas.

Despite the goals of MTT addressed in policy documents, the conditions for and status of MTT in schools are often poor (Ganuza & Hedman, Citation2017; Lainio, Citation2012; Reath Warren, Citation2013, Citation2017), reflecting the considerable challenges facing MTT teachers. These include the non-mandatory status of MTT, its disjuncture from other school subjects, and issues of legitimacy and limited time allocated to the subject. Using a historical and comparative perspective, Salö, Ganuza, Hedman and Karrebaeck (Citation2018) have analysed MTT in Sweden and Denmark. They showed that, in Sweden, a strong position of agents from the academy in relation to political stakeholders as experts in the fields has influenced policy making, while in Denmark, the question of MTT has mainly been political, with less influence from the academic field. Several researchers have analysed MTT policies historically in relation to the political field and identified different phases (see Cabau, Citation2014; Hyltenstam, Citation1986). In regard to policy and implementation, Lainio (Citation2012) talks of ambivalence, with an official discourse of support in policies, rhetoric and research that is not implemented in practice. Despite the marginalised position of the subject, in a study by Ganuza and Hedman (Citation2018, Citation2019)), participation in MTT showed a positive effect on student literacy development in Swedish and the mother tongue as well as the school result in general.

With regard to Creese and Blackledge (Citation2010, Citation2015)) have explored translanguaging practices in complementary schools in the UK, showing how both teachers and students use translanguaging in their meaning-making processes. In the Swedish context, Ganuza and Hedman (Citation2017) question the use of a translanguaging pedagogy in MTT, arguing in favour of MTT as a “protected space” for the language in question. However, as MTT takes place in a school and societal context dominated by Swedish, translanguaging practices are often a common way of language use for the students. Like Ganuza and Hedman, we recognise the need for MTT as a “protected space”, but this does not mean the exclusion of languages other than the actual mother tongue. Rather, we suggest that translanguaging pedagogy, rather than spontaneous translanguaging, can support students’ language learning and metalinguistic awareness. Such pedagogy may support the students to live in a pluralistic and linguistically diverse society.

3. Translanguaging space and linguistic landscaping

This article takes its point of departure in Li Wei’s use of the concepts translanguaging and translanguaging space, which builds on the notion of languaging, meaning “the process of using language to gain knowledge, to make sense, to articulate one’s thought and to communicate about using language” (Wei, Citation2011, p. 1223). Further, Li Wei introduces translanguaging space as a space created through the translanguaging process and as a space which creates possibilities for translanguaging, offering a “sense of connectedness” (Wei, Citation2011, pp. 1222–1223, see also Paulsrud et al., Citation2017; Straszer, Citation2017; Straszer & Wedin, Citation2018). The work of Lefebvre (Citation1991) has stressed how space does not exist in itself but is socially produced.

Also, Soja (Citation1996), drawing upon the work of Lefebvre, criticises an understanding of space in terms of binaries such as material vs. mental or imagined vs. real, and instead argues in terms of first space, second space and third space. First space refers to the material world while a second space perspective is the interpretation of the material through what Soja calls “‘imagined’ representations of spatiality” (Soja, Citation1996, p. 6). The notion of third space goes beyond such binary positions and is based on a both/and position, a concept also developed by Bhabha (Citation1994). Bhabha suggests that the “intervention of Third Space of enunciation, which makes the structure of meaning and reference an ambivalent process, destroys this mirror of representation in which culture is customarily revealed as an integrated, open expanding code” and argues that it “challenges our sense of the historical identity of culture as a homogenizing unifying force authenticated by the originary Past kept alive in the national tradition of the People” (Bhabha, Citation1994, p. 54). However, as pointed out by Hua et al. (Citation2017), the role of language and other semiotic resources has often been ignored in theories concerning space. Translanguaging space can be used to describe both the arena for translanguaging practices in terms of a physical and timely space and the social space created through the process of translanguaging. Hua et al. (Citation2017, p. 412–413) describe translanguaging space as follows:

Translanguaging Space emphasises the dynamic nature of multilingual communication whilst highlighting the complexity and interconnectivity of the multimodal and multisensory resources that are deployed in everyday interaction. Translanguaging Space is then a space where various semiotic resources and repertoires, from multilingual to multisensory and multimodal ones, interact and co-produce new meanings.

In line with Hua et al. (Citation2017), we are interested in spaces for translanguaging in relation to learning in an educational context. Therefore, the analysis will centre on the interplay between physical (including material) and social (including safe) spaces in the school context and the negotiation of a translanguaging space as a form of third space. Physical and material space is where educational settings are continuously formed and re-formed through the interplay between humans and the material conditions (see Frelin & Grannäs, Citation2017), while social space refers to social relations transforming across time and spaces, with a specific space exposing mixtures of social relations (Rönnlund & Tollefsen, Citation2016, p. 85). However, in line with the work on third space presented above, we do not understand physical and social dimensions of space as separated, but rather, the focus is on the intersections and interdependency between them. Through translanguaging, spaces are created for multilingual language users (Wei, Citation2011, p. 1223), who in turn widen their opportunities for meaning making and identity construction through translanguaging (Conteh & Brock, Citation2011, p. 349).

In this study, we use linguistic schoolscaping both as an analytical and theoretical tool. Linguistic schoolscaping is one type of linguistic landscaping, which implies the linguistic mapping of the physical environment of schools. Linguistic landscaping has been used to show how public space is symbolically constructed, describing and interpreting how languages are used visually in multilingual societies (e.g. Ben-Rafael, Shohamy, Amara & Trumper-Hecht Citation2006; Blommaert, Citation2013; Shohamy & Gorter, Citation2009; Spolsky & Cooper, Citation1991). Thus, linguistic landscaping is both a theory and a research method.

A linguistic schoolscape may be understood as a linguistic landscape on a smaller scale and is defined by Brown (Citation2012) as a “school-based environment where place and text, both written (graphic) and oral, constitute, reproduce, and transform language ideologies”, and she continues, stating that “schoolscapes project ideas and messages about what is officially sanctioned and socially supported within the school” (Citation2012, p. 282). For our study, linguistic schoolscaping refers to the study of the visual, spatial and social organisation of the school with a special focus on the MTT classroom as a space for translanguaging (see also Bíró, Citation2016; Brown, Citation2005; Szabó, Citation2015).

Linguistic schoolscaping has only recently been used to explore translanguaging spaces (Straszer, Citation2017), but it adds a new dimension that expands Li Wei’s idea of translanguaging space to include creativity and criticality (see Wei, Citation2011, p. 1223). In this study we do not analyse translanguaging practices in the classroom interaction but instead how language ideologies are manifested in the visual, spatial and social organisation of the MTT classroom, including how the classroom constitutes a safe space for translanguaging. The MTT classroom is analysed here through linguistic schoolscaping, that is, we analyse the school-based environment, and especially classrooms, where (as mentioned above) place and text constitute, reproduce and transform language ideologies (Brown, Citation2012, p. 282).

4. Methodology and material

This paper is based on an ethnographic study within the project Mother Tongue and Study Guidance in Compulsory School (financed by the Dalarna Centre for Educational Development, 2015–2017). In line with Street, Heath, and Mills (Citation2008), this study takes an ethnographic perspective in order to study everyday practices and the lived experiences of the participants in the sociocultural context using ethnographic tools such as observations and interviews. In the project, material was created through observations in classrooms and the school environment with field notes, recorded interviews and photographs of linguistic signs displayed on the walls as well as artefacts. The material analysed here was constructed mainly in one selected Kurdish MTT classroom, in the form of field notes from classroom observations during three days, photographs of the classroom interior, video recordings co-created with the MTT teacher (here called Evin), two audio-recorded interviews with Evin focusing on the creation and usage of all visual and linguistic material displayed in the classroom, and one interview with the school principal focusing on the organisation of MTT in the selected school.Footnote1 Also, a video recording of the displayed visual and linguistic materials in the school corridor and in some other classrooms has been analysed (in total, 82 minutes of video recordings). Moreover, our observations in the school at large are included in the analysis.

Our main data for this article, the co-created video recording of the MTT classroom, was produced as a “walk through” (also called a tourist guide method) where the researcher and MTT teacher talked about and described the classroom, mainly with a focus on the use of languages in different kinds of teaching materials and Evin’s reflections on her teaching. In this walk-through video recording, particular attention was paid to the different kinds of materials inside the classroom, and Evin was asked to describe them while walking around the classroom with the researcher. During the walk-through, the researcher encouraged Evin to show and talk about illustrations, texts, drawings, notes, maps and signs on the walls as well as materials on the tables and shelves. Evin, in dialogue with the researcher, described and discussed the history behind the different materials, where they were from (e.g. schoolbooks, the internet, students’ work from the past), how she had chosen them (e.g. their relevance to themes the different classes were working with) and why (e.g. for functional or aesthetic reasons, another teacher’s influence). This walk-through video recording was made after the three days of observations of the Kurdish MTT lessons. In the observations, the focus was on the interactions between students and the teacher, Evin, as well as between students. The interactions between the researcher and Evin, both in the walk-through video recording and in the interviews, were in Swedish but are here presented in English, translated by the authors. Other material analysed for the article includes photographs of signs comprising pictures and texts, artefacts and different kinds of teaching materials displayed on the walls, door, shelves, whiteboard and so on in the MTT classroom, and also in the school’s corridor and some other classrooms.

In the analysis, the focus was on the school-based environment, where place, together with visual and linguistic material, constitute, reproduce and transform language ideologies. Morevoer, the focus was on how spaces for translanguaging are opened by being officially sanctioned and socially supported in this school, and especially in the selected classroom and during the observed lessons. Using our definition of translanguaging space, we observed the use of different named languages, mainly Kurdish and Swedish. The analysis of the data was done in two steps to categorise the photographed signs and analyse the teacher’s description of spaces for translanguaging related to the linguistic materials in the classroom. First, the physical and material dimensions of space for translanguaging in the school and MTT classroom were analysed, focusing on the photographed signs and the teacher’s description of them. Then, as step two, observations in the classroom and the school environment, combined with the recording from the walk-through video recording, were used to explore the social space for translanguaging of MTT to enable an analysis of whether and how the MTT classroom constituted a social and safe space for translanguaging.

Ethical considerations were made throughout the research process. Participants were informed about the goals, and written consent was given by participants, for students through their caregivers. All data has been stored safely and pseudonyms are used.

5. The local context of the study

The chosen MTT classroom is in an elementary school with classes from preschool to grade 6. The school is located in a Swedish town in which 20% of the population has a migration background; in the school, about 80% of students have a migration background. The school has about 300 students, and as the number of Kurdish-speaking students is relatively high, the Kurdish MTT teacher, Evin, is permanently employed at the school and has her own classroom. In this school, the MTT lessons in Kurdish are organised as part of the students’ ordinary timetable, between 40 and 60 minutes every week. This is enabled by having the schedule extended for all students. Those who do not study MTT have an extra reading lesson in Swedish during this time. The MTT students have few opportunities to use and develop Kurdish in school since the main language used is Swedish.

Evin’s situation differs from that of many other MTT teachers in the municipality and in Sweden as a whole (see e.g. Lainio, Citation2012; Spetz, Citation2014, see also Reath Warren, Citation2013, Citation2017), as many teachers often move between different schools, lack appropriate facilities, and teach their classes after the ordinary school day has ended. The interviewed school principal highlights the particular situation at the school, and predominantly what she describes as good collaboration between Evin and the class teachers.

Evin teaches and is responsible for all MTT classes in Kurdish at the school. She describes herself as having a Kurdish background. In terms of higher education, she has studied Education and MTT education in Sweden. She migrated to Sweden at the age of 12 and took part in MTT classes herself as a student in Sweden. She has extensive experience with MTT and participated with colleagues in Läslyftet (in-service training for teachers in literacy teaching) a few years ago. She says that she tries to incorporate content from other teachers into her own planning. She particularly mentions her collaboration with teachers in earlier age groups and Swedish as a second language (SSL).

6. Findings

We start by analysing the MTT as a physical and material space for translanguaging, through visual and linguistic material displayed both in and outside the classroom, in this case, in the school corridor. Then social dimensions of the classroom will be analysed in relation to the concept of safe space for translanguaging.

6.1. The physical and material space of the school and selected MTT classroom

6.1.1. The school corridor

The linguistic diversity of the students is represented only to a limited extent in the school corridor leading to the MTT classroom. At the school entrance is a short text of welcome in Swedish; it faces a glass cabinet displaying photographs of the school staff together with their names, positions and/or subject fields. It is apparent from the photographs and names that many teachers have a migration background or come from families that have migrated to Sweden. The walls of the corridor are adorned with a variety of materials, including the rules of conduct, texts about the Swedish scientist Alfred Nobel, and paintings and drawings created by students. The latter include posters picturing children with greetings in different languages printed in speech balloons. However, the only language used in displays, except for the greetings mentioned above, is the majority language, Swedish. In the corridor there are also glass cabinets displaying students’ athletic records, and there is a bulletin board on which the school paper, rules of behaviour, recycling information and an environmental certificate are displayed. All texts are in Swedish.

On the door to the staff room, facing the corridor, information about specific school projects is posted. There are shelves in the corridor with diverse teaching materials, such as books and demonstration material for biology lessons. There is also a small school library with books in different languages. Some of them are common Swedish books for children translated into different languages, and there are also easy-to-read books. Opposite the library, there are several big cupboards, and on one of them there is a small sign reading Arabiska (Arabic in Swedish). Beside the cupboards, there are posters with the Arabic alphabet.

In summary, in the school corridor, the space that is central for all visitors and from which all classrooms are accessible, the linguistic diversity of the students is only represented to a limited extent by the posters with speech balloons, the books on the shelf, and the posters with the Arabic letters, and thus there is not much space for translanguaging.

6.1.2. The Kurdish classroom

In contrast to the corridor, the linguistic landscape in the MTT classroom for Kurdish displays mainly Kurdish in combination with other languages. This Kurdish classroom is a small group room where 6–8 students sit closely packed, and as there are plenty of language materials, paintings, shelves and textiles in the room, it can be perceived as pleasant and comfortable. There is a varied selection of written materials on the door, the walls, the shelves and the board to be used for work in the room. Kurdish is represented on the classroom walls, which are decorated with posters, texts, pictures and other materials related to the geographical area where the language is dominant. On the whiteboard, messages and written texts are displayed mainly in Kurdish, but also in Swedish.

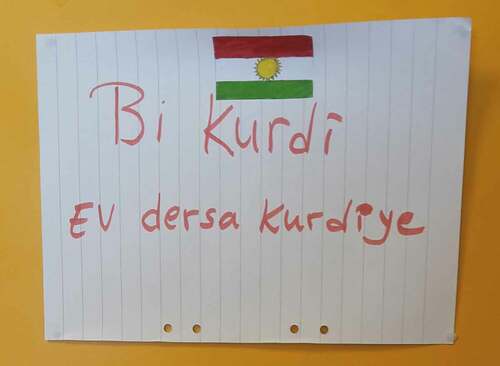

While there is no permanent sign outside the classroom indicating that this is where Kurdish classes are taught, there is a handwritten A4 sheet on the inside of the door (see ) with the Kurdish flag and the text Bi kurdī Ev dersa kurdiye [Speak Kurdish: This is a Kurdish lesson].

Through the co-created walk-through video recording, spatiality appears as lived, perceived and conceived (Soja, Citation1996, p. 74) by the actors, in this case through the dialogue between the researcher and the MTT teacher. During the walk-through video recording, Evin explains the note, saying: “As they [students] only speak Swedish with each other, I tell them in Kurdish that this is a Kurdish lesson.”Footnote2 Hence the message is directed to the students inside the classroom, urging them to use Kurdish and reminding them that the room is a space for Kurdish lessons. Evin’s statement highlights the issue of linguistic hierarchies in the school, as students tend to use mainly Swedish and thus there is a perceived need for a specific space for Kurdish. As a result, Evin’s message marks both participation and repertoire: it specifies that in this classroom, you participate in a Kurdish lesson, and it marks that here and now is a space for speaking Kurdish.

The school rules of conduct, printed on pink paper, are posted on one wall, and the evacuation plan is posted beside the entrance; both are Swedish. According to Evin, the list of rules, which is found in each classroom in the school, had been given to her by the SSL teacher at her request.

In front of a painting on the wall by a famous Swedish painter (Carl Larsson), Evin explains that it was put up by another teacher, who had used the classroom previously. Evin explains that she found the painting beautiful and had decided to keep it for aesthetic reasons. When walking through the classroom, she also describes how and when she uses certain materials.

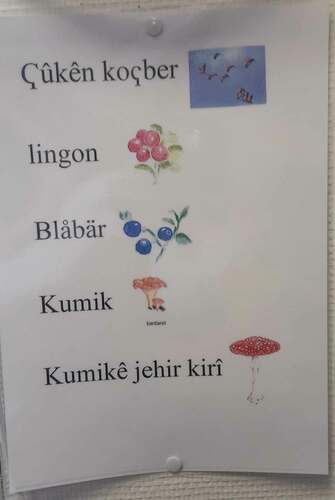

The classroom walls are covered with some educational material from different content areas that has been copied and laminated, mostly in Kurdish. The texts and pictures have been printed from different web pages, and in some cases also from different linguistic contexts, and they include abbreviations in English and vocabulary in two Kurdish varieties and Turkish. Evin explains that the materials were chosen based on the needs of the different groups of students, considering varied content and following the tasks given to the same students by the SSL teacher. As an example, one A4 illustration displays drawings and photos on the theme of autumn that students have worked with in SSL classes. Next to the drawings and photos, there are single words, some of them in Kurdish, such as migratory birds, while others are in Swedish, such as lingon (lingonberries) and blåbär (blueberries) (see ).

The teacher explains her choice of language in this specific task in the following way:

[Migration birds] is in Kurdish while we don’t have a word for lingonberries, so I thought they might as well learn the Swedish word and it is better. And then blueberries, they had that explained in the [Swedish-Kurdish] dictionary and I though that no, there is no point [in teaching any Kurdish word], they can learn the word [in Swedish].Footnote3

Thus, the examples illustrate how the MTT classroom is linked to other classrooms in the school, and also how the teacher includes and connects to activities in which students participate in their regular classes. This example, as well as the rules of conduct, shows how the Kurdish classroom is connected to and is part of the school.

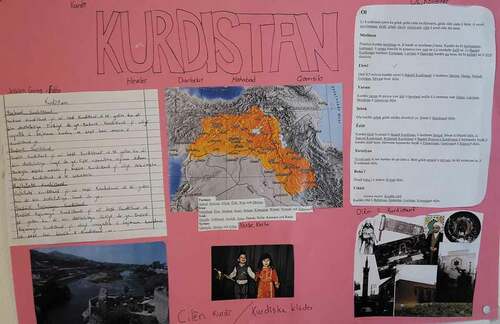

High on one wall, starting from the corner, there is the Kurdish alphabet, with each letter on a laminated A4 page together with a picture of something that begins with the appropriate sound and the word in Kurdish underneath. There is also an A3-size laminated map, edited by the European Union, of the languages of Europe with the flags on one side. It is interesting to note that not the whole area that counts as Kurdistan is visible on the map as the map is of Europe alone. Evin, however, pays attention (during the walk-through video recording) to the Kurdish flag that is displayed together with the other flags. Moreover, works by previous students displaying the map of Kurdistan as well as different aspects of Kurdish culture are visible (see ).

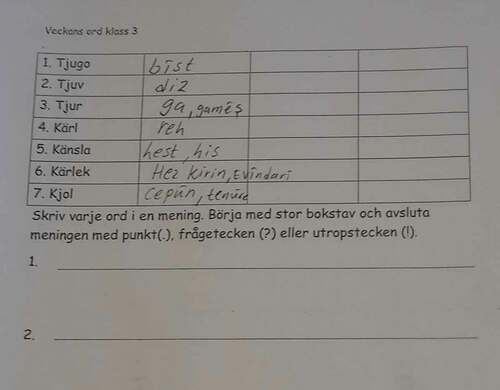

On the whiteboard, the current date is written in Kurdish. According to Evin and as was also noted during lesson observations, all lessons start with a review of the month, day and date in Kurdish. On Evin’s desk, there are several A4 sheets with tasks for different student groups. On one of the sheets, there are seven words in a table, with one column for Swedish in print and in another column Evin’s handwritten equivalent in Kurdish. Beneath the table, there are instructions about the use of the concepts in Swedish (see ).

Evin explains that the task was given to her by the SSL teacher. As the picture above shows, the exercise consisted of words which the SSL teacher wanted the students to use to practise the pronunciation of the sound [ç] in Swedish (here spelled <tj>). Hence, the vocabulary list did not take Kurdish as the point of departure, and the compilation of the words was made according to the students’ needs when learning SSL. Evin stresses on several occasions, such as during the walk-through video recording in front of a piece of paper posted on the wall, that she follows the goals for MTT set out in the national syllabus but that she also plans her classes in accordance with the plans of the class teachers and the SSL teachers. This shows that even though Evin has a lot of influence over the choice of content in her classes, the choice is influenced by close collaboration with other teachers.

Translanguaging is a common practice in school assignments, as, for example, when the Kurdish-speaking children get an instruction in both Swedish and Kurdish to write sentences in Kurdish, based on Swedish words aiming to practise a special sound in Swedish. Also, the images on the wall include different named languages and pictures from various geographical and cultural areas The richness of teaching materials, texts and illustrations on the walls shows a flexible use of different linguistic resources. Hence, the material space creates conditions for students to use the named languages Kurdish and Swedish as well as photos, maps and other visual resources for meaning making. The potential for translanguaging differs from that in most other classrooms in the school where the material is mainly in Swedish and where few opportunities are given for translanguaging.

6.2. The social space of the MTT classroom in relation to safe space for translanguaging

While the previous section mainly focused on the physical and material space of the classroom, we will now turn to the second dimension, the social space for translanguaging. Here, social dimensions of the classroom as a space will be analysed in relation to whether this may be perceived as a safe space for translanguaging, based on observations in the classroom and its surroundings as well as the walk-through video recording and interviews with Evin.

In the Kurdish MTT classroom, different groups of students come for one lesson every week. The younger students are picked up by Evin from their classrooms, while older students come to the classroom when they have a scheduled class. When they enter the classroom, each student is greeted in Kurdish by Evin with a handshake. This routine is something that may be interpreted as an initial social mark through its repetition before each lesson. Evin’s perception of this is related to other routines at the start of each lesson, as she describes in the interview:

I want them to do it because I think that is really, you get respect then, and they think that it is fun to come to class also. That when you greet them and then they enter and then they need to take their seats, and we start with today’s, the date and such. I think it is really important because then the children learn both the language in the same time, which day it is because it is needed here, it is needed there.

Evin stresses that entering the Kurdish classroom should be marked with respect for each other, and she notes that this routine also serves as an important language learning element, indicating that from here on, everybody in the classroom is to use Kurdish. The recurrent routines at the start of each class may serve to create a feeling of belonging and safety in using a language other than the dominant Swedish. Thus, our interpretation is that the classroom is a social space for using and developing mainly the Kurdish language.

Evin starts the class by going through what is written on the whiteboard: the date, month and the season of the year. According to Evin, she wants to create a relaxed environment for the students and a suitable introduction that bridges between the other classes, where mainly Swedish is used, and the use of Kurdish in MTT. That she explicitly mentions having a relaxed environment indicates her desire to ensure that students feel comfortable and safe in her class. An example of how the MTT classroom may constitute a safe space for translanguaging is that Evin connects new content in Kurdish to something that students are familiar with, like Swedish expressions and concepts:

We talk a lot about the text, we work with vocabulary and have the words of the week, and then there are words and concepts that I use a lot. They need to know them in both Kurdish and Swedish, and I try to help as much as I can.

Hence, as Evin expresses it, there is a connection between the topics, concepts and methods for teaching between the other classes in school and MTT. This could be interpreted as a way to create social bridges between the MTT classroom and the regular classrooms with which students are more familiar and where Swedish is the dominant language. Even the use of educational tools in other classes may have a social dimension of space for translanguaging, such as for comparisons between cultural and other aspects of life in Sweden and Kurdistan.

Our observations also show that the interactions during the Kurdish lessons include translanguaging practices. Evin, in some situations, asks students questions in Kurdish and then repeats the same questions in Swedish. She explains that it is because she wants to make sure that every student has understood. She also allows the students to answer in Swedish, and the students can use Swedish to ask Evin questions. We consider this to be another example of the social dimensions of a safe space for translanguaging.

7. Discussion and implications

The aim of the study was to create knowledge about the MTT classroom and how it is positioned as a safe space for translanguaging, with a focus on the physical and social dimensions of the MTT classroom. Our analysis of physical and social dimensions revealed varied aspects of the Kurdish classroom as a safe space for translanguaging.

The physical space included mainly Swedish and Kurdish, and although there was a sign explicitly urging students to use Kurdish, observations revealed that this was implemented in what may be called a soft way, with students and the teacher using Swedish to help students understand when they felt it was needed. The use of routines including both Kurdish and Swedish may be understood as creating a space where both Kurdish and Swedish languages are welcome. Also, this implies that the classroom may be understood as a space that is open for meaning making and identity construction through various linguistic resources (Conteh & Brock, Citation2011) and as a safe space for translanguaging (Wei, Citation2011). However, when it comes to both physical and social dimensions of space, they seem to have been mainly created by adapting the Kurdish classroom to ordinary classrooms, for example, by working with the same words as are used in the SSL classroom. We did not find many signs of adaptation going in the other direction, for example, with the other parts of the school incorporating Kurdish words or features. Admittedly the schedule was adapted to fit students who study MT, and who constituted the majority at the school, but whether linguistic adaptations and safe spaces for translanguaging existed outside the classroom was not studied here.

If we understand translanguaging space as a space where different semiotic resources and repertoires interact and also create new meaning (see Hua et al., Citation2017), the Kurdish MTT classroom is, on the one hand, constructed as a Kurdish-only classroom, where Kurdish is the preferred language, made visible, for example, through the door sign, while on the other hand Swedish is used inside the classroom together with different varieties of Kurdish and other languages in both written and oral form. Thus, the classroom may be perceived as a safe space for using a variety of languages, with Kurdish being the preferred one.

This Kurdish MTT classroom is also a space where Kurdish norms, values and identities are encouraged both through the material displayed on walls and by the teacher’s use of languages. However, it is essential to highlight that these are dynamic and part of this specific school context in this specific community in Sweden. Thus, the classroom may be perceived as a safe space for translanguaging (Canagarajah, Citation2011), where Kurdish dominates while being included in a Swedish-dominant school setting. This Kurdish space has physical borders in the form of a separate room, and it is also bounded by scheduled lesson times. When both students and the teacher pass through the entrance to the classroom at the start of the lesson, the dominant language shifts from Swedish to Kurdish. Thus, language choice differs between the inside of the MTT classroom and the outside, with varied linguistic resources visible and audible in both. In accordance with Bhabha (Citation1994), the classroom may thus be understood as a third space, a space located in time and one in which Swedish is dominant, and it thereby represents otherness. However, as those in the classroom, the MTT teacher and students, all belong to what may be perceived as the marginalised group here, this example shows the vulnerability highlighted by Ganuza and Hedman (Citation2017), as here there are no signs of mutual ideologies of translanguaging, where both the majority Swedish context and the minoritized MTT classroom interact.

In relation to the study by Ganuza and Hedman (Citation2017), who also raised the question of translanguaging with regard to minority languages in MTT, in our study the MTT teacher gives voice to a more inclusive discourse, opening up the MTT classroom for translanguaging practices, more in line with the Somali classroom in Straszer and Wedin (Citation2018) and Wedin, Straszer, and Rosén (Citationsubmitted). This may be due to the teacher’s quite solid position in the school in this case, through her collaboration with other teachers and the fact that she has a permanent space for her classes. However, we also see the risk that Ganuza and Hedman (Citation2017) warned about, the risk of dominant languages being given space, here, for example, in the form of tasks based on issues of spelling and pronouncing Swedish, while we did not see signs of Kurdish being given similar space outside the classroom. On the contrary, physical traces of students’ diverse languages were rarely represented outside the MTT classroom.

Using schoolscaping and observations as analytical tools sheds light on physical and social dimensions of the translanguaging space in the MTT classroom. Here the analysis has been widened beyond functions of signs (Landry & Bourhis, Citation1997) and also beyond language ideologies (Brown, Citation2012) to include social dimensions in the understanding of the linguistic landscape of the classroom. Contrary to most of the other studies of MTT in the Swedish context (Ganuza & Hedman, Citation2015; Lainio, Citation2012; Reath Warren, Citation2013), this classroom held a less marginalised position regarding the organisation, terms and other conditions. Through schoolscaping we showed that translanguaging, in terms of flexible use of different kinds of linguistic resources, forms, signs and modalities, is a part of the linguistic landscape of the studied MTT classroom. Involving the teacher in the production of the data added the teacher’s perspective to the study of MTT classrooms. By making the physical and social dimensions of space in the classroom visible, MTT in this case stands out as a safe space that is opened for translanguaging practices while also showing the risk of losing space to dominant languages, in this case Swedish. Schoolscaping in combination with researcher-teacher reflections gave a nuanced view of language ideologies in the classroom, and, in relation to earlier research that has highlighted the problem of marginalisation of MTT, showed what may be the result of the permanent placement of a Mother Tongue Teacher in one school, with her own, permanent, classroom and MTT lessons included in the ordinary schedule of the school.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Boglárka Straszer

Boglárka Straszer is Associate Professor of Swedish as a Second Language, Dalarna University, Sweden, with 20 years of experience teaching foreign languages, second languages, mother tongue and sociolinguistics. Her research interests include the sociology of language, linguistic schoolscaping, multilingualism and translanguaging, language identity and attitudes, and education in various immigrant and minority language settings. She has previously co-edited two volumes on translanguaging and education and is currently working on volumes on Mother Tongue Instruction, Home Language Instruction and Translanguaging in the Age of Mobility.

Jenny Rosén

Jenny Rosén, holds a PhD in Education and works as Associate Professor in Swedish as a Second Language at the Department of Language Education at Stockholm University, Sweden. Her research interest is multilingualism, literacy, language policy and diversity in educational settings.

Åsa Wedin

Åsa Wedinholds a PhD in linguistics and is a professor in educational work at Dalarna University, Sweden. She has carried out research in Tanzania, on literacy practices in primary school, and in Sweden on literacy and interactional patterns in classrooms and on conditions for multilingual students’ learning. Her research is ethnographically inspired, particularly using linguistic ethnography and theoretical perspectives where languaging is studied as social and cultural practices and where opportunities for learning are related to questions of power.

Notes

1. “Kurdish” is used here to refer to all varieties of Kurdish used among students and teachers in this specific school, including mainly Kurmanji, and to a lesser degree Sorani and occasionally other varieties.

2. Translated from Swedish by the authors.

3. Interviews were conducted in Swedish and have been translated by the authors.

References

- Ben-Rafael, E., Shohamy, E., Muhammad Hasan, A., & Trumper-Hecht, N. (2006). Linguistic landscape as symbolic construction of the public space: The case of Israel. International Journal of Multilingualism, 3(1), 7–30.

- Bhabha, H. (1994). The location of culture. London: Routledge.

- Bíró, E. (2016). Learning schoolscapes in a minority setting. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae. Philologica, 8(2), 109–121.

- Blackledge, A., Creese, A., Baraç, T., Bhatt, A., Hamid, S., Wei, L., … Yağcioğlu, D. (2008). Contesting ‘language’ as ‘heritage’: Negotiation of identities in late modernity. Applied Linguistics, 29(4), 533–554.

- Blommaert, J. (2013). Ethnography, superdiversity and linguistic landscapes: Chronicles of complexity. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Brown, K. D. (2005). Estonian schoolscapes and the marginalization of regional identity in education. European Education, 37(3), 78–89.

- Brown, K. D. (2012). The linguistic landscape of educational spaces: Language revitalization in Southeastern Estonia. In D. Gorter, H. F. Marten, & L. Mensel (Eds.), Minority languages in the linguistic landscape (pp. 281–298). Hampshire, England: Palgrave McMillan.

- Cabau, B. (2014). Minority language education policy and planning in Sweden. Current Issues in Language Planning, 15(4), 409–425.

- Canagarajah, S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95(iii), 401–417.

- Canagarajah, S. (2013). Agency and power in intercultural communication: Negotiating English in translocal spaces. Language and Intercultural Communication, 13(2), 202–224.

- Conteh, J., & Brock, A. (2011). ‘Safe spaces’? Sites of bilingualism for young learners in home, school and community. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 14(3), 347–360.

- Creese, A., & Blackledge, A. (2010). Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: A pedagogy for learning and teaching. The Modern Language Journal, 94(1), 103–115.

- Creese, A., & Blackledge, A. (2015). Translanguaging and identity in educational settings. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35, 20–35.

- Cummins, J. (1980). Negotiating identities. Education for empowerment in a diverse society. Ontario: California Association for Bilingual education.

- Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Davies, A. (2003). The native speaker: Myth and reality (2nd ed.). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Frelin, A., & Grannäs, J. (2017). Skolans mellanrum: Ett relationellt och rumsligt perspektiv på utbildningsmiljöer. [The third space of school: A relational and spatial perspective on educational environments]. Pedagogisk Forskning I Sverige, 22(3–4), 198–214.

- Ganuza, N., & Hedman, C. (2015). Struggles for legitimacy in mother tongue instruction in Sweden. Language and Education, 29(2), 125–139.

- Ganuza, N., & Hedman, C. (2017). Ideology vs. Practice: Is there a space for pedagogical translanguaging in mother tongue instruction? In B. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, & Å. Wedin (Eds.), New perspectives on translanguaging and education (pp. 208–225). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Ganuza, N., & Hedman, C. (2018). Modersmålsundervisning, läsförståelse och betyg: Modersmålsundervisningens roll för elevers skolresultat. [Mother tongue instruction, reading comprehension and grades – The role of mother tongue instruction for school achievements]. Nordand. Nordisk Tidsskrift for Andrespråksforskning, 13(1), 4–22.

- Ganuza, N., & Hedman, C. (2019). The impact of mother tongue instruction on the development of biliteracy: Evidence from Somali-Swedish bilinguals. Applied Linguistics, 40(1), 108–131.

- García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- García, O., Ibarra Johnson, S., & Seltzer, K. (2016). The translanguaging classroom. Leveraging student bilingualism for learning. Philadelphia: Caslon.

- García, O., & Kleyn, T. (2016). Translanguaging theory in education. In O. García & T. Kleyn (Eds.), Translanguaging with multilingual students: Learning from classroom moments (pp. 9–34). New York: Routledge.

- Hua, Z., Wei, W., & Lyons, A. (2017). Polish shop(ping) as translanguaging space. Social Semiotics, 27(4), 411–433.

- Hyltenstam, K. (1986). Politik, forskning och praktik. In Invandrarspråken - ratad resurs? (pp. 6–24). Stockholm: Forskningsrådsnämnden.

- Hyltenstam, K., & Milani, T. (2012). Modersmålsundervisning och tvåspråkig undervisning. In K. Hyltenstam, M. Axelsson, & I. Lindberg (Eds.), Flerspråkighet: En forskningsöversikt (pp. 17‒152). Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet. Vetenskapsrådets rapportserie 5: 2012.

- Lainio, J. (2012). Modersmåls erkända och negligerade roller [The acknowledged and neglected roles of mother tongues]. In O. Mikael (Ed.), ymposium 2012: Lärarrollen i svenska som andraspråk. [Symposium 2012: The teacher role in Swedish as a second language] (pp. 66‒96). Stockholm: Stockholms universitets förlag.

- Landry, R., & Bourhis, R. Y. (1997). Linguistic landscape and ethnolinguistic vitality: An empirical study. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 16(1), 23–49.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Mills, J. (2004). Mothers and mother tongue: Perspectives on self-construction by mothers of Pakistani heritage. In P. Aneta & B. Adrian (Eds.), Negotiation of identities in multilingual contexts (pp. 161–191). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Paulsrud, B., Rosén, J., Straszer, B., & Wedin, Å. (eds.). (2017). New perspectives on translanguaging and education. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Reath Warren, A. (2013). Mother tongue tuition in Sweden: Curriculum analysis and classroom experience. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 6(1), 95–116.

- Reath Warren, A. (2017). Developing multilingual literacies in Sweden and Australia: Opportunities and challenges in mother tongue instruction and multilingual study guidance in Sweden and community language education in Australia (PhD diss). Stockholm: Stockholms universitet.

- Rönnlund, M., & Tollefsen, A. (2016). Rum: Samhällsvetenskapliga perspektiv. [Space: Social science perspectives]. Stockholm: Liber.

- Runfors, A. (2009). Modersmålssvenskar och vi andra: Ungas språk och identifikationer i ljuset av nynationalism. Utbildning & Demokrati, 18(2), 105–126.

- Salö, L., Ganuza, N., Hedman, C., & Karrebæk, M. S. (2018). Mother tongue instruction in Sweden and Denmark. Language policy, cross-field effects, and linguistic exchange rates. Language Policy, 17(4), 591–610.

- SFS. (2009). Språklagen 2009:600. [Language Act]. Swedish code of statutes. Stockholm: Ministry of Culture.

- SFS. (2010). Skollag 2010:800. [Education Act]. Swedish code of statutes. Stockholm: Ministry of Education and Research.

- Shohamy, E., & Gorter, D. (eds.). (2009). Linguistic landscape: Expanding the scenery. New York and London: Routledge.

- SNAE. (2017a). Skolverkets statistikdatabas. [Statistics of Swedish national agency for education]. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

- SNAE. (2017b). Grundskolan: Elevstatistik. [Elementary school – statistic of pupils]. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

- SNAE. (2017c). Elever och skolenheter i grundskolan läsåret 2016/17. [Students and school units school year 2016/17]. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

- SNAE. (2018). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and the recreation centre 2011. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

- Soja, E. W. (1996). Third space: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

- Spetz, J. (2014). Debatterad och marginaliserad: Perspektiv på modersmålsundervisningen. [Debated and marginalised: Perspectives on mother tongue tuition]. Stockholm: Språkrådet. Rapporter från Språkrådet 6.

- Spolsky, B., & Cooper, R. (1991). The languages of Jerusalem. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Straszer, B. (2017). Translanguaging space and spaces for translanguaging: A case study of a finnish-language pre-school in Sweden. In B. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, & Å. Wedin (Eds.), New perspectives on translanguaging and education (pp. 129–147). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Straszer, B., & Wedin, Å. (2018). “Rum för transspråkande i modersmålsundervisning.” [Space for translanguaging in mother tongue tuition]. In B. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, & Å. Wedin (Eds.), Transspråkande i svenska utbildningssammanhang [Translanguaging in Swedish educational context] (pp. 217–242). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Street, B., Heath, S. B., & Mills, M. (2008). Ethnography: Approaches to language and literacy research. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Szabó, T. P. (2015). The management of diversity in schoolscapes: An analysis of hungarian practices. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies, 9(1), 23–51.

- Wedin, Å., Straszer, B., & Rosén, J. (submitted). Multi-layered language policy and translanguaging space: A mother tongue classroom in primary school in Sweden.

- Wei, L. (2011). Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222–1235.