ABSTRACT

The modest impact of national policy efforts on school digitalisation relates to a gap between views among policy-makers and practitioners, giving rise to complexity in translating policy into action. Acknowledging changes in governing through alternative policy formation-processes, and Ward and Parr’s (2011) arguing for the importance of strategic- and operational policy coherence, the focus of this paper is the forming of a national plan of action for the digitalisation of schools in Sweden (#skolDigiplan). Within this interview study, the views on policy work and challenges of digitalisation of schools are explored among an exclusive management group of non-traditional Swedish policy-makers appointed to produce the #skolDigiplan. Based on the findings, I conclude that national policy making regarding the digitalisation of schools may be conducted through a collective process, with several educational stakeholders contributing. Furthermore, I suggest that non-traditional national policy-makers, arguing a lack of digital competence knowledge concerning schools at the governing or authority level, may consider taking a step back in the policy-formation process as a supportive action. Teacher training programmes, despite being portrayed as important for the policy outcome, were declared distant in this policy process.

Over the past decade, there has been a global movement in educational governing, calling for updated policy documents coherent to the impacts of digital technology in society (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], Citation2010; UN Human Rights Council [UNHRC], Citation2016). In Europe, this movement has been supported and promoted by the European Commission (Ferrari, Citation2012), whose engagement has involved the development of the concept of digital competence in policy, describing the competence needed among citizens in digitalised societies (Vuorikari, Punie, Carretero, & Brande, Citation2016). Recent reports from the European Commission show that the vast majority of the European countries now address digital competence in their national school policies (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, Citation2019). In Sweden, digital competence was emphasised in a recent national strategy regarding digitalisation of schools, which was launched in 2017 (Government decision I:1, Supplement to Government decision, Citation2017).

Within this strategy “the digitalisation of schools” is used to describe both the enabling of digital competence for all in the Swedish school system as well as access to digital technology for teachers and students alike. This interpretation is chosen further within this paper. The goal established in the Swedish strategy was to “become world leading in utilising the possibilities of digitalisation” (p. 3). Providing support for this goal set to be reached by 2022, the Swedish government decided to produce a supportive operational policy: the national plan of action for the digitalisation of schools. Notably, instead of handing this task to the National Agency for Education, the Swedish government assigned this to the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions [SALAR] (Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions [SALAR], Citation2019).

Previous researchers have reported that digitalisation of schools has attracted a number of new stakeholders influencing policy processes and school governing, thus raising questions of appropriate forms of government policy making (Selwyn, Citation2018; Williamson, Bergviken Rensfeldt, Player-Koro, & Selwyn, Citation2018). According to Selwyn (Citation2018), this partly resides in that governing policy efforts on the digitalisation of schools have had limited influence in school practice (Hammond, Citation2014; Olofsson, Lindberg, & Fransson, Citation2017; Supovitz & Weinbaum, Citation2008). School policy adherence in general has been found challenging, due to variations in school contexts and the complexity of policy translation, of which it is said there is a lack of understanding among policy-makers (Cuban, Citation2013; Supovitz & Weinbaum, Citation2008). Similarly, Hammond (Citation2014) suggested a gap between the views of policymakers and practitioners regarding policy on digital technology in schools. This particular gap, Ward and Parr (Citation2011) argued, partly arises from incoherent strategic- and operational policies not sufficiently directing and supporting policy adoption within school practice. Following Ward and Parr (Citation2011), research on what considerations shape the operational policy formation work would enable a deeper understanding of the digitalisation of schools. Against this backdrop, the aim of this paper was to explore the views among an exclusive group of non-traditional national school policy-makers in Sweden, appointed to produce a national plan of action for the digitalisation of schools, the so-called #skolDigiplan (SALAR, Citation2019). The paper investigates the following: (a) How do Swedish non-traditional national policy-makers view the policy formation work of #skolDigiplan and (b) what do they consider challenging for the projected policy outcome?

Throughout this paper, policy is broadly approached and conceptualised as both text and practice (Ball, Citation1993). Policy as practice is acknowledged in terms of actions (or inactions) in response to what is understood as requested. This means that policy will relate to both the #skolDigiplan document and the process forming the digitalisation of schools. It should be noted here that policy within this understanding is considered complex, context dependent, and nonlinear (Ball, Maguire, & Braun, Citation2012; Bell & Stevenson, Citation2006).

The Swedish context

Similar to many other countries in Western Europe (Voogt, Knezek, Christensen, & Lai, Citation2018), Sweden recently introduced new policies on digital technology in K–12 schools. In 2017, the national strategy for the digitalisation of schools was launched (Government decision I:1, Supplement to Government decision, Citation2017), and the following year, a revised school curriculum integrating digital competence into all school subjects (Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE], Citation2018). Within both policies, emphasising the enabling of digital competence for all (Fransson, Lindberg, & Olofsson, Citation2018), the term was defined in line with the European Commission’s framework (Vuorikari et al., Citation2016). Thus, digital competence was set within four areas: (a) understanding how digitalisation affects society, (b) ability to use and understand digital tools and digital media, (c) taking a critical and responsible approach, and (d) ability to solve problems and transform ideas into action (SNAE, Citation2017). However, a study involving interviews with 25 Swedish upper secondary teachers on the national policies on digital competence indicated that the policies, when acted upon, were context sensitive in ways possibly challenging educational equality (Olofsson, Lindberg, & Fransson, Citation2019).

The Swedish municipalities, operating more than 80% of all K–12 schools, are organised by SALAR. On 31 January 2018, the Swedish Government gave SALAR the assignment to produce #skolDigiplan. Earlier agreements with SALAR on national education governing issues had been made (see Williamson et al., Citation2018); however, the fact that SALAR, a nongovernmental organisation (NGO) supporting local authority independence, was entrusted with the responsibility of producing a national school policy instead of the National Education Agency, can be considered unique in Sweden’s history.

For the production of #skolDigiplan, an exclusive group of 13 members, which I from here on will refer to as the DGM (digiplan group members), were appointed by SALAR on a national level. The governmental agreement emphasised that #skolDigiplan was to be produced in dialogue with the National Education Agency and in broad cooperation with other stakeholders within the Swedish educational sector (SALAR, Citation2019). Hence, the DGM represented the Research Institute of Sweden, academia, and one charter school apart from SALAR and the National Agency for Education. The DGM, having extensive experience in either the digitalisation of schools or organisational development, worked independently, though monitored by a group of six consisting of the Director General of the National Agency for Education, representatives from the Ministry of Education, and three directors from SALAR. #skolDigiplan – the operational policy set to support both the national strategy and the revised curriculum – was to be delivered to the Swedish government by March 2019, after which the group would be dissolved.

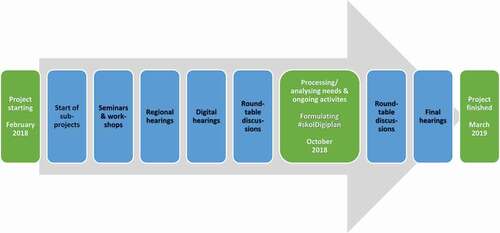

What can be noted in particular about the #skolDigiplan project is the open arrangement and the fact that besides the DGM, a number of educational stakeholders from various locations across Sweden were involved. The working model developed and used in this project was based on three subprojects with arranged activities such as roundtable discussions, digital and district hearings, seminars, and workshops. Such activities were conducted throughout the entire project, as illustrated in . The internal DGM activities are illustrated as green boxes, and external activities such as hearings and seminars are illustrated as blue boxes. Some of these external activities were conducted together with invited reference and working groups, some were open to certain stakeholders, and others were fully public. Either way, the activities were openly posted on social media platforms and on the webpage (http://skoldigiplan.se/) established by SALAR.

The #skolDigiplan was presented to the Swedish government on 18 March 2019 as a 60-page document covering a status analysis, with descriptions of needs to fulfil the goal of the national strategy for the digitalisation of schools, the responsibilities and undertakings of the educational providers, and suggestions of 18 national initiatives. These initiatives emphasised clarity of responsibilities, support for local school actors, improvement in teacher and school leadership training programmes, in-service training for school staff, nationally coordinated work on standardisation, strategic use of educational data, and more and better use of research.

Finally, in the Swedish context of school policies on digital technology, one should bear in mind that Swedish schools are highly driven by decentralised governance models (Jarl & Rönnberg, Citation2019). Even though governing in recent years has become more an object of governmental control via, for instance, evaluation systems (Hanberger, Carlbaum, Hult, Lindgren, & Lundström, Citation2016), local school providers are given considerable autonomy in policy interpretations and adaptation into local school contexts (Nordin, Citation2016; Sundberg & Wahlström, Citation2012). Combined with a high degree of transparency and individual teacher accountability, this local autonomy is suggested reducing teachers authority within national policy making (Helgøy & Homme, Citation2016).

Conceptualising the policy process

Conceptualising the process of school policy formation on digital technology may be done from wider and narrower perspectives. Each perspective contributes to better understanding how such a policy takes shape (Hill & Hupe, Citation2014). From a wide perspective, research on school policy on digital technology has shown a global policy mobility between countries and that policy development builds on an assemblage of relations, coalitions, and partnerships between actors within, but also outside, the educational sector, such as venture capital, IT industry, and non-profit organisations (Williamson et al., Citation2018). With these new incoming actors in the policy processes of school digitalisation, it is suggested that new beliefs or value systems may enter (Selwyn, Citation2018). Through a national or local perspective, the process of policy development may similarly be conceptualised as complex, actor dense, and context dependent, building on translations and enactment (Ball et al., Citation2012; Bell & Stevenson, Citation2006). This transfers to an understanding that even in a narrower perspective, actions (or inactions) may be conceptualised based on their relation to an abundance of actors.

In this paper, I chose to focus on one of these actors by closely examining views among national policy-makers, more precisely the policy text producers. I did so by conceptualising the policy process using a more narrow linear process (see Ward & Parr, Citation2011), which I will present below. National policymakers are sometimes described in policy research as important stakeholders who are hard to reach. For example, researchers have discussed how to access (Beyers & Braun, Citation2014) or how to collaborate with policymakers (Ranchod & Vas, Citation2019). Nevertheless, here, I explored the stated views of text producing policymakers engaged in the digitalisation of school policies. Similar to Taylor (Citation1997) I argue the importance of developing an understanding of the “many layered nature” of policy making, and inspired by Bacchi (Citation2009) I suggest that research on how the policy problem of school digitalisation is understood by the text producing policy makers can contribute to such an understanding. Moreover, that such scrutinising perspective may be of special importance when researching policy on digital technology in schools (Nivala, Citation2009).

This paper concerns views related to the development of a national operational policy. Supovitz (Citation2008) suggested that policy processes should be considered iterative refractions, meaning that policy is formed and adjusted by each organisational level involved. Similarly, Ward and Parr (Citation2011) suggested that school policy on digital technology may be conceptualised as a process formed via different levels at which the policy develops. Three important policy levels are the strategic level, the operational level, and the school practice level (Ward & Parr, Citation2011). Moreover, they argued that when it comes to digital technology in schools, coherence between these levels is particularly important for the policy outcome. Thus, if the initial work of forming the strategic policy into operational policy is inaccurate or incomplete, the impact will be limited. A flawed operational policy, according to Ward and Parr (Citation2011), presumes some level of “buy-in” from the stakeholders, which implies that digital technology policy in schools becomes a policy for the already engaged. Arguably, problems of adherence to school policy on digital technology could relate to the operational policy level, more precisely its lack of coherence with strategic policy. Moreover, this points to the importance of the stakeholders’ understandings of both policy and the digitalisation of schools.

Thus, my stance in this paper is that national policy on the digitalisation of schools might depend on a coherent understanding among stakeholders, and that policy makers may try to encounter coherent policy understanding by using different strategies. What Perryman, Ball, Braun, and Maguire (Citation2017) described as ownership of policy can be understood as one such strategy. They argued that participation in the translation process (to which I draw in parallel with the #skolDigiplan formation process) supports policy ownership and may contribute to the policy work and outcome.

By this conceptualisation of the policy process, the work on coherence between levels of school policy on the digitalisation of schools can be explored through a narrower perspective, more precisely, based on views among the unusual text producing policymakers of the DGM. From these general principles of policy conceptualisation, the next section points out challenges in the digitalisation of schools.

Conceptualising challenges in the digitalisation of schools

Challenges in the digitalisation of schools may be conceptualised using more than one perspective. In a review, Pettersson (Citation2018) described a lack of research on digital competence in schools from the perspective of wider school settings, such as organisational infrastructure and digitally competent strategic leadership. Supovitz and Weinbaum (Citation2008), on the other hand, emphasised the importance of local context and the difficulties of understanding reforms based on the complexity, breadth, and extent of variation in school policy processes.

Thus, in this paper, in addition to exploring the process of policy formation, I will analyse conceptualisations of the challenges in the digitalisation of schools through (a) the problem situation related to the overall discursive settings nationally and (b) conditions for endorsement, which will address local context-dependent conditions in schools (c.f. Hanberger, Citation2001). Such context-dependent challenges found within research are, for example, computer access, variations of time available for working with digitalisation, teacher and principal education, organisational development, local collaborations, and level of engagement in the process of digitalisation (Tondeur, Van Keer, Van Braak, & Valcke, Citation2008).

Methods

The study was based on interviews conducted with members of a small, exclusive, temporarily formed Swedish management group of non-traditional national policymakers, with the responsibility to form #skolDigiplan. Initial contact was made with the head of the DGM. The response was positive; thus, I explained and discussed this study, as well as the overall research project, in a video meeting lasting for about 75 minutes. As an outcome of the meeting, the head of the DGM became the gatekeeper (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, Citation2011). I sent invitations to participate to the members after the #skolDigiplan was presented to the Swedish Government on 18 March 2019. Given the exclusive set-up of the group and the total number of persons involved in the policymaking process at this level, the possible research subjects to include were highly limited. Of the 13 members, eight (62%) accepted the invitation to participate in the study. To my knowledge, this representation did not skew the study outcome. In this paper, the DGM are separated by numbers one to eight (M1–M8). Due to their joint work on #skolDigiplan, there is a risk that the members could possibly identify one another in the paper. This could also be the case among their co-workers at SALAR, the National Agency for Education, and others with close insight on the #skolDigiplan process or other professional connections within this particular policy work. Acknowledging this as the case, and in an attempt to uphold the delicate issue of confidentiality within this type of study, the findings are mainly presented in general terms.

The first seven semi-structured interviews (Galletta, Citation2012) were conducted during a 5-week period, May–June 2019. By early November 2019, when the first interviews were transcribed, confirmed, and initially analysed, I conducted an interview with the head of the DGM. All interviews were conducted via video conference meetings (Zoom or Skype for Business). The interview method drew upon the work of Brinkmann & Kvale, Citation2018), and the interviews concerned three broad themes: (a) the role as the originator in the policy formation of #skolDigiplan, (b) the work on #skolDigiplan in relation to the established goals, and (c) the importance of digital competence in the Swedish school system. In this paper, I focus primarily on themes (a) and (b). Each interview lasted approximately one hour, in total 451 minutes, with an average of 56 minutes per interview. With permission from the members, I digitally recorded the interviews, which gave me the possibility to watch the interviews several times afterwards (Cohen et al., Citation2011; Salmons, Citation2016).

The recordings were transcribed verbatim and thereafter sent individually to each participant for confirmation, and the opportunity to remove, add, or clarify content. The transcriptions were then cleared of identifying information and imported into NVivo12®. With inspiration from Boyatzis (Citation1998), I first coded the transcriptions inductively, focusing on what was said. I then categorised these codes into one or more of the three interview themes presented above. Thereafter, I examined the three themes one by one, and codes within the same theme were sub-coded into a structure based on similar smaller properties. To ensure that no relevant data were excluded, I watched each recorded interview once again and re-read the transcripts several times. I did so until saturation was reached. Finally, I clustered the sub-codings of each theme into different significant findings that resolved into a thematic structure presented as findings.

Findings

A reinforcing policy-producing process

According to Bacchi (Citation2009), members of an exclusive group of national school policy-makers have a unique potential for policy impact by managing what is being advocated, as well as how and for whom policy is written. In addition, controlling the policy-formation model may influence stakeholder translations, hence affecting the policy outcome. The findings presented in the following section offer insights concerning considerations of both policy formation and the policy text among the DGM. The members addressed their considerations on the outcome based on the formation model used in the process, anticipated challenges connected to the ongoing digitalisation of schools in Sweden, and the tensions and settlements when finalising the #skolDigiplan policy.

The importance of the #skolDigiplan working model

All members emphasised the importance of the model used (see ) in the formation of #skolDigiplan, although they stated that it was initially questioned from both within and outside the group. The activities conducted, from roundtable discussions to seminars and digital hearings, were pointed out as crucial for the quality outcome. The model was said to be built on thick descriptions, initiating large-scale engagements and cooperation, raising stakeholder awareness nationally, hoping to upgrade the priority of this issue. Moreover, the model was declared a formula for committing stakeholders to the policy and the endorsement of #skolDigiplan. Thus, stakeholder participation would contribute positively to the policy outcome, enabling fulfilment of the national strategy goals by 2022. According to one of the members,

We needed to reconsider the traditional top-down perspective within a central bureaucracy. We concluded that such a model would encounter a limited commitment and that the model [we chose] was important, wanting people to actually endorse the plan of action [i.e., the #skolDigiplan]. Commitment was needed in each part of the municipality organisation, carrying out this work. Moreover, if you have been a part of a process, and engaged in developing this plan of action [i.e., the #skolDigiplan], our belief as a group was that the likeliness of engagement afterwards in the outcome would be higher. (M3)

Another aspect emphasised in the formation model of #skolDigiplan was the cooperative efforts in the process. Put differently, the chosen model enabled networking initiatives, as well as developed new cooperation between involved stakeholders (i.e. various local public authorities and school leaders), activities that could both strengthen the support for the policy work of school digitalisation and be seen as additional support for stakeholders “lagging behind.” One of the members expressed this as follows:

We [the DGM] went out in the country and had regional hearings. All local authority heads of education attended, indifferently of how far they had come in the digitalisation of schools. These hearings included discussions about the #skolDigiplan, initiated a dialogue that was constructive for us in terms of input, as well as for stakeholders who then started to discuss questions concerning this [issue]. This was also a purpose by the [chosen] model. (M2)

Raising national awareness on the policy work and the #skolDigiplan process seemed to be high on the DGM agenda. The model was also discussed as a tool for gaining higher priority among people other than already engaged and committed stakeholders. Mobilising national support and endorsement of the #skolDigiplan, it was argued, would have an important impact on the policy outcome, simply by attracting attention to the policy work. Not least, the national outreach of the model was discussed as important, exemplified by expressions such as the following:

That you as a local educational stakeholder can participate and have influence. This has also contributed to a democratic process where everyone has had the right to share his or her opinion. This [policy work] has been known. That has been beneficial. (M6)

Despite the efforts described earlier to attract significant participation in the policy work, the members expressed some dissatisfaction with the turnout. Notably, this regarded particularly those educational providers and school practitioners who were considered to be furthest from reaching the established national policy goals. How broader participation could have been accomplished seemed to be a nagging question discussed within the group, as one member commented:

We [the DGM] have had a continuous discussion about how to reach the ones in most need of support. Not the enthusiasts or the ones already on the front line. We need to reach the doubtful. How do we get the ones in the back of the train to approach … this [digital] development? This was a struggle to the very end [of the #skolDigiplan project]. (M1)

These limits to enabling participation were partly acknowledged as due to the time schedule set for #skolDigiplan, expressed by one member as follows:

We have had extremely tight timelines considering what we wanted to do … . You cannot just travel from [a far distance] just like that. You need to know in advance, for long-term planning. Personally, this [shortcoming in enabling participation] bothers me, although these were the premises we had [within the project]. (M6)

Challenges of policy outcome

The DGM unusual choice of a model for the policy-formation process transferred in some way to their addressing of challenges of the national policy outcome. I analysed these challanges using two perspectives (cf. Hanberger, Citation2001). The first is the problem situation, focusing on the perception of national context, and second, conditions for endorsement, in which three sub-themes frame the acknowledged thresholds: (a) aspects of resources, (b) organisation and cooperation, and (c) digital competence.

The problem situation: decision-making engagements and polarisation

Based on the outset of the #skolDigiplan model, one may note that within the DGM challenges of policy outcome was the wide national context. Hence, the problem situation pertained to their stated national discourse, the contextual character of a decentralised Swedish governance model (Jarl & Rönnberg, Citation2019) and the local autonomy in policy interpretations (Nordin, Citation2016; Sundberg & Wahlström, Citation2012). Challenges emphasised herein were the need for decision-making engagement and aggravating aspects of polarisation. In addition, the importance of willingness to engage among school officials and politicians was highlighted, as well as for them to take steering and governing decisions. Some members seemed to fear the withholding of important decisions by these stakeholders, or the resisting of engagements, purposely avoiding possible conflicts that school digitalisation might cause. Articulating this fear regarding both politics and the national discourse on digital technology in school, one member said,

The entire question of digitalisation of school [in Sweden] is kidnapped by a bunch of people making it a question of mobile phones in the classroom or some other totally irrelevant nonsense. This situation causes the politicians to freeze. These people have reached out nationally with their agenda to the extent that you [the politician] lose votes if you take an opposite stance. This is tragic. Next election is still sometime ahead of us, which is bloody lucky, because this [the policy work with the #skolDigiplan] would never have happened [in] an election year. (M4)

In relation to the need for decision-making, members stressed an urgency for a sound debate involving both positive and critical opinions about digital technology in school. Here, the expectation was that the policy formation model of #skolDigiplan would set the standards, which in line with Williamson et al. (Citation2018) point at a development towards an expanding number of actors involved from within, but also from outside, the educational sector. However, society polarisation was considered a major challenge, mainly in terms of diminishing the national policies of school digitalisation into issues of detailed practicalities. As one member expressed it,

As soon as you are stuck [in a polarised discussion], it immediately becomes a question of the presence of digital tools in the classroom, and you have completely abandoned the society perspective in this issue. Therefore, even those with a positive stance end up in discussions on digital tools in the classroom, when this should be a non-question. (M7)

In dealing with this challenge of the problem situation, according to some members, answers might possibly be found through developing understandings of digital competence, digital technology, and school among these particular stakeholders. As one member, rather harshly, put it,

At present, the lack of digital competence expands the higher up in the educational system you look. This goes, none the least, for the Department of Education [in Sweden], today itself being in a total lack of digital competence. (M3)

On the same issue, one member expressed the importance of understanding as the way to overcome this challenge and that knowledge of school needs must be communicated at higher levels:

That such knowledge is transported up in the [educational] system, as well as established politically. If not sanctioned, there will be no support. A comprehensive view of the preconditions required is needed among political decision-makers, and a vision as well. (M2)

Conditions for endorsement

Additional to the problem situation, the members brought challenges that revolved around the conditions for the endorsement of the policies. This theme addresses issues of resources, competence, and organisation, here presented as thresholds, issues that might more easily transfer to policy work within a local context. To some extent, the thresholds posed by the members are addressed within the #skolDigiplan initiatives. This is noted within the following sections.

Resources

For educational providers in general, the new Swedish national policies on the digitalisation of schools have not come with any financial support. Among the members, additional financial resources were considered important to provide sufficient conditions enabling policy implementation (i.e. digital infrastructure and educational software facilitating teaching and learning). According to the members, the time frame set for meeting the national policy goals by 2022 placed urgency on the challenge of resources. Of special concern, members argued, were educational providers and schools furthest from meeting the policy goals. Within #skolDigiplan, national requirements for additional resources were implicitly suggested within several initiatives. However, the challenge of sufficient resources was considered a major threshold for the policy outcome. Some of the members expressed that the lack of financial support nationally might partly be why SALAR was entrusted with producing #skolDigiplan. The suggested explanation was that if the policy were provided by someone other than the National Education Agency, the obligations for financial resources at the national level would be weakened.

Organisation and cooperation

In #skolDigiplan, many suggested initiatives on structural organisational development are provided. At least half of the 18 initiatives include either new efforts or efforts coordinated in a better way between educational stakeholders. Among the members, some argued that organisational structure should be emphasised, as opposed to issues of resources. This challenge was primarily set within educational governing above the school level. However, as the national discourse was described as focusing on educational practice, members argued that this threshold was experienced as more challenging. As one member argued,

Working with any kind of change, failing usually comes when you grow a bit too distant from the “working floor level”. Here, it is almost the opposite. Too much focus is directed on the school practitioner level and too little on the higher organisational and structural perspective. (M7)

As presented earlier, the #skolDigiplan model was hoping to enthuse stakeholders, accomplishing cooperation tied to the digitalisation of school policies and thereby supporting organisational development. However, within the #skolDigiplan document, it is unclear which organisations are supposed to take the lead in the suggested organisational developments, despite the involvement of the National Agency for Education and SALAR. Moreover, members acknowledged that issues such as lacking ambition, competence, or confidence might prevent organisational restructuring or development of new cooperation. Hence, it was likely that national arrangements based on government decisions would eventually come into question. However, members argued that the Swedish government would more easily be able to assign these responsibilities according to the suggestions within the #skolDigiplan initiatives.

Digital competence

Among teachers in practice, digital competence was not emphasised as a major obstacle. On the contrary, the members seemed to hold the opinion that most practitioners were on track fulfiling the policy goals by 2022. Even so, the inequality of digital competence among teachers was still a concern among the members. In fact, within #skolDigiplan, there is one initiative particularly addressing additional training for teachers.

Given examples of the limited number of pages and the visuals included, the members emphasised their own efforts towards ensuring readability when finalising the #skolDigiplan document. The members portrayed easy access as a means to overcome the threshold of lacking knowledge on digital competence primarily among governing authorities. This was discussed throughout the process, whereas a working goal had been an “online-only” policy document offering hands-on guidance for educational providers. Although desired, this ambition was acknowledged by the members as far beyond the designated task of the #skolDigiplan project. Hence, among people governing schools (i.e. politicians and local officials), digital competence was not viewed favourably.

A final challenge within digital competence addressed the Swedish teacher training programmes (TTPs). More precisely, TTPs build on outdated traditions, neither corresponding with new demands of a digitised school practice nor enabling student teachers to develop the digital competence necessary for their future profession. This institution was depicted as part of a rigid and old-style academia, being too slow in adapting to the rapid changes in a digitalised society. As one member commented, “Academia is so incredibly hard to steer and change. Things are stuck in the walls, cemented in cultures, and quite some territorial pissing to be honest” (M4).

Adding to the challenge of overcoming this threshold was said to be the situation of smaller TTPs in Sweden, a situation over which, one member noted, Sweden has received some critical remarks by the OECD. Within #skolDigiplan, one suggested initiative addresses how universities offering teacher education should develop their TTPs to meet the requirements expected from the national policies on the digitalisation of schools. Several initiatives also emphasised gains from an increased closeness between academic research and teaching practice. According to the project description of #skolDigiplan (SALAR, Citation2019), the policy-formation model was applied by means significantly less inclusive, addressing stakeholders within the university structure. Although mentioned by members, it was not criticised in any way.

Tensions and settlements when finalising #skolDigiplan

Within the work of the DGM, it was clear that opposing views at times were the point of departure. Tensions between the two high-profile organisations involved, SALAR and the National Agency for Education, were the most apparent. SALAR, often described as the project owner, was acknowledged as the undisputed authority in the work with #skolDigiplan. However, all members emphasised their efforts in finding ways to write a satisfying policy for all, coherent with the positions taken by both SALAR and the National Education Agency. According to the members, these tensions were no surprise and partly considered constructive, pushing the policy-formation process forward. As one member explained,

There are different missions. A national agency must abide [by] legislations that are highly regulatory, while SALAR as an organisation run by its members engages in what their members consider important issues … . It was self-evident. There would be clinches. (M5)

In the interviews, SALAR was often described as favouring “sharper wordings” within the policy text. Examples given of such wordings either indicated that SALAR was in charge of some initiatives transferring governing responsibilities to them or implied a strengthened national governance including additional resources. The National Agency for Education was described as grinding the wordings, adapting the text to what might be politically acceptable. Accomplishing settlements between the two organisations through the choice of wordings was regarded as significant for the quality of the policy outcome. However, even though the ambition set was to place both SALAR and the National Agency for Education as equal signatories to the #skolDigiplan, this became unmanageable in the end based on one additional aspect in the choice of wordings. As one member described, “The National Agency for Education may not declare actions needed to be done by another national agency. This was, to some extent, required within the #skolDigiplan” (M4).

Members also mentioned other opposing views, expressing loss of some specific content not included in the final policy text of #skolDigiplan. These comments were often related to acknowledgement of personal representation forwarding specific stakeholders or advocating for particular groups in need of special considerations, that is, different practitioners (e.g. school leaders, librarians, teachers), students (e.g. with special needs), or educational providers (e.g. local governing authorities). However, despite the tensions and opposing views within the DGM, they all argued with confidence that their settlement verified the best possible outcome of #skolDigiplan.

Discussion

Because digital competence and the digitalisation of schools have become national interests in many Western European countries, the gap between national policy efforts and school policy outcomes within this area has gained interest in research (Voogt et al., Citation2018). In this discussion, I will elaborate on the findings and address what non-traditional policymakers as the DGM consider challenging for the digitalisation of schools. Moreover, I will offer further understanding of their views on policy-formation work on this issue.

The findings suggest that the DGM might consider school digitalisation primarily a governing issue due to a lack of knowledge about digital competence among these high-level stakeholders. Hence, in relation to the context-dependent challenges for school digitalisation locally, as reported by, for example, Tondeur et al. (Citation2008), the additional challenges brought forward by the DGM related to governmental or high-level stakeholder initiatives, as well as the importance of national depolarisation. The challenges acknowledged by the DGM can be categorised as follows: (a) setting a new focus in the policy work, zooming out from a classroom- and teacher-centred view; (b) mobilising national support for the policy work; (c) initiating collaboration; (d) balancing the public debate; and (e) committing stakeholder engagement to the policy.

The findings suggest that the DGM consider a more open operational policy-formation process a possible way to overcome school digitalisation thresholds. Building on the work of Ward and Parr (Citation2011) and Supovitz (Citation2008), this might be seen as building coherence between strategic and operational policy, setting new terms for policy refractions and thus stepping away from the risk of digital technology efforts in school becoming, as Ward and Parr (Citation2011) suggested, a policy for the already engaged. According to the findings, handling challenges of school digitalisation was sought through a developed dialogue, measures, Ward and Parr (Citation2011) argued, undervalued in school policy efforts on digital technology. This aligns with the work of Supovitz (Citation2008), suggesting that dialogue may enable adherence to a collective view, thus supporting school policy consistency and increasing acceptance towards changes made.

The #skolDigiplan working model developed and used included open national arrangements, for example, roundtable discussions, digital and district hearings, seminars, and workshops. Physical meetings spread across the country, as well as online alternatives, contributed to accessibility in partaking. Stakeholders at all levels (e.g. educational providers, organisations, teachers’ unions, students, researchers, and technology industry professionals) were called upon to engage in the process. These efforts were considered actions contributing to the policy outcome. In other words, the model () would potentially bridge the policy gap by offering influence of the national policy document itself through the policy-formation work. Thereby, the #skolDigiplan model may also be understood as an effort by the DGM to build “policy ownership” among stakeholders (Perryman et al., Citation2017). An ownership that at best, according to Perryman et al. (Citation2017), could result in making space for collective self-improvement, thus improving the policy outcome by a form of softer governing.

The findings suggest that the model of policy-formation work chosen by the DGM have implications on the role of governing. Opening up the work of producing an operational policy, by broadly inviting stakeholders to take part in the policy-formation process, resides in a deliberate transference of power from those traditionally responsible for national governing to others, in this example from the DGM, or even more the National Agency for Education, to a wide range of other contributors. Furthermore, that rather than being overlooked by the DGM, this situation was acknowledged, accounted for, and scaled up, thus being considered necessary to set policy on school digitalisation in motion. Hence, based on the findings, one could argue that non-traditional policymakers, such as the DGM, may consider policy work on the digitalisation of schools to benefit from national governance taking a step back, thereby enabling other educational stakeholders to take a leap forward. According to Selwyn (Citation2018), inviting “untraditional” educational stakeholders into the formation of school policy comes with the risk of compromising values imbedded in the school context. This may also be discerned in the DGM special concern for national equality in this work, where the educational providers who were “hard to reach” were considered an unsolved problem.

The specific policy-formation process examined in this study additionally includes an element of shared responsibility with an NGO for a national policy process, namely SALAR being entrusted with producing the #skolDigiplan. Hereby, the findings indicate two interesting aspects that may come in to play within such a situation, illustrating the complexity of policy development (Williamson et al., Citation2018). First, the NGO might place pressure on the government to clarify their own school governing responsibilities, hereby setting new terms on national governing. As an example, one discussion in the DGM was whether Inera, a company owned by SALAR, would be suggested contractor for building national digital infrastructures in schools. If such suggestion had been included in #skolDigiplan, a governmental response on who are to provide for the schools infrastructure had been expected. Second, national agencies criticising one another may implicitly be made possible. The example being the National Agency for Education’s withdrawal from being signatory of the #skolDigiplan, thereby enabling a critique on TPPs otherwise inappropriate within current national agency restrictions.

As noted, stakeholders within TTPs were not included to the same extent in the #skolDigiplan model. Even so, arguments regarding this choice were not present in the interviews. This might relate to what was said earlier, that universities (and their TTPs) have their own governing agency in Sweden. Another possibility could be the opposing views initially described by the members regarding the use of the #skolDigiplan model.

Considering the initiatives presented in #skolDigiplan, one might suggest that the work of Swedish TTPs will be a possible target of scrutiny moving forward. Moreover, it would be interesting to know how the TTPs might have responded if a broader invitation had been extended to them.

Finally, the strong unity in the support of the finalised #skolDigiplan policy, projected by the DGM, will be emphasised. This includes the process of compiling, summarising, and writing this document, the #skolDigiplan model. The basis for the negotiation process “balancing” the #skolDigiplan, clearly considered an asset to the quality outcome of the policy, were descriptions of internal arguing by members advocating certain issues or holding particular standpoints. Thus, resolving tensions, or perhaps rather an acceptance of the different views within the member group, suggests that the understanding of policy coherence (Supovitz, Citation2008; Ward & Parr, Citation2011) and ownership (Perryman et al., Citation2017) was also established as practice within the group itself.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to explore the views among members of an exclusive group of non-traditional national school policy-makers assigned to produce a national plan of action for the digitalisation of schools in Sweden, the #skolDigiplan. Insights offered regard how such stakeholders understand policy-formation work and view challenges of the digitalisation of schools.

The findings suggest that the challenges of the digitalisation of schools are considered primarily based on issues at the governing or authority level, issues experienced as discarded in a national discourse focusing on teacher practice when the digitisation of schools is discussed. Moreover, to be successful within national policies on the digitalisation of schools, the non-traditional policymakers argued the need for a national collaborative process in which stakeholders at all levels are involved. Thus, corresponding to this view, the policy-makers developed a policy-formation process, the #skolDigiplan model. This suggests a view that policy coherence between national strategy and operational policy may narrow the gap between policy and practice, as Ward and Parr (Citation2011) described.

Despite the inclusive efforts, the findings signal that TTPs are not included in the discussions about the digitalisation of schools to the same extent as many other stakeholders. The reason has not been uncovered, yet the TTPs are firmly criticised by members of the group.

Conclusively, the Swedish work on the digitalisation of school entered a new phase with the 2017 national strategy, where the goal was set and an emphasis on this policy process was initiated. However, further research on the policy work of the strategy, #skolDigiplan, and on how the digitalisation of schools in Sweden proceeds is needed to further explore how this special policy process is experienced and acted upon, in response to what is requested, by educational providers and school practitioners in Sweden.

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my thanks to the participating group members for contributing to the study with valuable information.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ulrika Gustafsson

Ulrika Gustafsson is a PhD student in education at the Department of Applied Educational Science, Umeå University. Her main research interest is in the field of the digitalisation of the K-12 school, with a special interest in digital competence and policy.

References

- Bacchi, C. L. (2009). Analysing policy: What’s the problem represented to be?.Frenchs Forest, N.S.W: Pearson.

- Ball, S. J. (1993). What is policy? Texts, trajectories and toolboxes. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 13(2), 10–17.

- Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2012). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools. London: Routledge.

- Bell, L., & Stevenson, H. (2006). Education policy: Process, themes and impact. London: Routledge. Leadership for learning.

- Beyers, J., & Braun, C. (2014). Ties that count: Explaining interest group access to policymakers. Journal of Public Policy, 34(1), 93–121.

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. London: SAGE.

- Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2018). Doing interviews (2nd ed.). London: SAGE.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th ed.). London: Routledge.

- Cuban, L. (2013). Why so many structural changes in schools and so little reform in teaching practice? Journal of Educational Administration, 51(2), 109–125.

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. (2019). Digital education at school in Europe. Eurydice Report. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Ferrari, A. Institute for Prospective Technological Studies. (2012). Digital competence in practice: An analysis of frameworks. Luxembourg: Publications Office.

- Fransson, G., Lindberg, J. O., & Olofsson, A. D. (2018). Adequate digital competence - A close reading of the new national strategy for digitalization of the schools in Sweden. Seminar.net: Media, Technology and Lifelong Learning, 14(2), 217–228.

- Galletta, A. (2012). Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: From research design to analysis and publication. New York: New York University Press.

- Government decision I:1, Supplement to Government decision. (2017). Nationell Digitaliseringsstrategi För Skolväsendet [National Digitalisation Strategy for the School System]. Dnr U2017/04119/S. The Swedish Ministry of Education.

- Hammond, M. (2014). Introducing ICT in schools in England: Rationale and consequences. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(2), 191–201.

- Hanberger, A. (2001). What is the policy problem? Methodological challenges in policy evaluation. Evaluation, 7(1), 45–62.

- Hanberger, A., Carlbaum, S., Hult, A., Lindgren, L., & Lundström, U. (2016). School evaluation in Sweden in a local perspective: A synthesis. Education Inquiry, 7(3), 349–371.

- Helgøy, I., & Homme, A. (2016). Towards a new professionalism in school? A comparative study of teacher autonomy in Norway and Sweden. European Educational Research Journal, 6(3), 232–249.

- Hill, M. J., & Hupe, P. L. (2014). Implementing public policy: An introduction to the study of operational governance. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Jarl, M., & Rönnberg, L. (2019). Skolpolitik: Från riksdagshus till klassrum [School politics: From Parliament building to classroom]. Stockholm: Liber.

- Nivala, M. (2009). Simple answers for complex problems: Education and ICT in Finnish information society strategies. Media, Culture & Society, 31(3), 433–448.

- Nordin, A. (2016). Teacher professionalism beyond numbers: A communicative orientation. Policy Futures in Education, 14(6), 830–845.

- Olofsson, A. D., Lindberg, J. O., & Fransson, G. (2017). What do upper secondary school teachers want to know from research on the use of ICT and how does this inform a research design? Education and Information Technologies, 22(6), 2897–2914.

- Olofsson, A. D., Lindberg, J. O., & Fransson, G. (2019). A study of the use of digital technology and its conditions with a view to understanding what “adequate digital competence” may mean in a national policy initiative. Educational Studies, 46(6), 1–17.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. (2010). The OECD innovation strategy: Getting a head start on tomorrow. Paris/ OECD Publishing.

- Perryman, J., Ball, S. J., Braun, A., & Maguire, M. (2017). Translating policy: Governmentality and the reflective teacher. Journal of Education Policy, 32(6), 745–756.

- Pettersson, F. (2018). On the issues of digital competence in educational contexts – A review of literature. Education and Information Technologies, 23(3), 1005–1021.

- Ranchod, R., & Vas, C. (2019). Policy networks revisited: Creating a researcher–policymaker community. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 15(1), 31–47.

- Salmons, J. (2016). Designing and conducting research with online interviews. In J. Salmons (Ed.), Cases in online interview research (pp. 1–30). Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Selwyn, N. (2018). Technology as a focus of education policy. In R. Papa & S. W. Armfield (Eds.), The Wiley Handbook of Educational Policy (pp. 457–477). Newark: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Sundberg, D., & Wahlström, N. (2012). Standards-based curricula in a denationalised conception of education: The case of Sweden. European Educational Research Journal, 11(3), 342–356.

- Supovitz, J. A. (2008). Implementation as iterative refraction. In J. A. Supovitz & E. H. Weinbaum (Eds.), The implementation gap: Understanding reform in high schools (pp. 151–172). New York: Teachers College Press.

- Supovitz, J. A., & Weinbaum, E. H. (2008). Reform implementation revisited. In J. A. Supovitz & E. H. Weinbaum (Eds.), The implementation gap: Understanding reform in high schools (pp. 1–20). New York: Teachers College Press.

- Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions [SALAR]. (2019). #skolDigiplan Nationell handlingsplan för digitalisering av skolväsendet [#skolDigiplan National plan of action for the digitalisation of schools]. Sverigens Kommuner och Regioner. https://issuu.com/sverigeskommunerochlandsting/docs/7585-773-2

- Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE]. (2017). Få syn på digitaliseringen på grundskolenivå : Ett kommentarmaterial till läroplanerna för förskoleklass, fritidshem och grundskoleutbildning [Discover digitalisation at the compulsory school level: A commentary to the curriculum for the preschool class, school-age educare and compulsory school]. Stockholm: Author.

- Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE]. (2018). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare 2011. Stockholm: Author. (Revised 2018).

- Taylor, S. (1997). Critical policy analysis: Exploring context, texts and consequences. Discourse (Abingdon, England), 18(1), 23–35.

- Tondeur, J., Van Keer, H., Van Braak, J., & Valcke, M. (2008). ICT integration in the classroom: Challenging the potential of a school policy. Computers & Education, 51(1), 212–223.

- UN Human Rights Council [UNHRC]. (2016). Right to education in the digital age—Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to education. 11/ 28/2018. United Nations, General Assembly, Human Rights Council, April 6, A/HRC/32/37. https://www.ohchr.org/en/issues/education/sreducation/pages/annualreports.aspx.

- Voogt, J., Knezek, G., Christensen, R., & Lai, K.-W. (Eds.). (2018). Second handbook of information technology in primary and secondary education. Springer International Publishing.

- Vuorikari, R., Punie, Y., Carretero, S., & Brande, L. V. European Commission. (2016). DigComp 2.0: The digital competence framework for citizens. Luxembourg: Publications Office.

- Ward, L., & Parr, J. M. (2011). Digitalising our schools: Clarity and coherence in policy. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(2), 326–342.

- Williamson, B., Bergviken Rensfeldt, A., Player-Koro, C., & Selwyn, N. (2018). Education recoded: Policy mobilities in the international ‘learning to code’ agenda. Journal of Education Policy, 34(5), 705–725.