ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to investigate professional agency in the context of higher education as manifested in Swedish teacher educators’ perceptions regarding their working life in a digital society and to seek to obtain insights on salient factors influencing professional agency and identity. Eighteen semi-structured interviews with teacher educators working at four different universities were analysed using directed content analysis. The theoretical perspective taken is a subject-centred socio-cultural approach to professional agency. This is an approach where the social context (the socio-cultural conditions) and individuals’ agency (professional subjects) are mutually constitutive but analytically separate. Agency is something that is exercised, and in this study, professional agency was explored in the work context, in teaching practice and in relation to the professional identity. The results of this study not only confirm the complexity of being a professional TE in the times of digitalisation but more importantly demonstrate a paradox in the TE’s perceived high agency that both enables and hinders self-development (the individual) as well as development of the working community, the organisation, and the university. The study implies that considerations and understanding of the TE’s autonomy and perceived agency are significant for professional and work development.

Introduction

Digitalisation is described, as early as 2000, by Castells (Citation2000) as an information-technological revolution, a paradigm shift that affects our entire lives, working life as well as social life. For the educational structures of the society digitalisation changes the conditions for communication, meaning-making, and learning (Selwyn, Citation2016). Teacher education, being one of these structures, faces and has faced challenges in relation to this transformation of the educational system, such as educating for the future when the future is rapidly changing. Teachers on all levels of the school system are expected to acquire new knowledge and develop digital competences, strategies and methods to meaningfully integrate digital technology into educational practice and organise teaching so that the student can use digital resources (e.g. hardware (e.g. classroom technologies), software (including apps/games) or digital content/data (i.e. any files, including images, audio and video)) in a way that promotes knowledge development (e.g. European Commission, Citation2018; Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, Citation2019; Swedish National Agency of Education, Citation2017; Voogt, Fisser, Pareja Roblin, Tondeur, & van Braak, Citation2013). This in particular creates a dilemma for teacher educators (TEs): how to educate the pre-service teacher to act as an educator in the present and in the future, helping them developing relevant digital competences (Lipponen & Kumpulainen, Citation2011), when teaching and learning simultaneously (Roumbanis Viberg, Forslund Frykedal, & Hashemi Sofkova, Citation2019). This study aims to investigate how professional agency is manifested in the TEs perceptions under these circumstances.

Globally, teacher education programmes have a responsibility to give pre-service teachers, as future teachers, the best prerequisites to be able to work as teachers. Like many other pre-service programs around the world, the Swedish teacher education programme is currently challenged to prepare the pre-service teachers for a digitalised teaching and working life, visible both in research studies (e.g Amhag, Hellström, & Stigmar, Citation2019; Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik, Citation2017) as in policy documents and reports (Demoskop, Citation2016; Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions [Sveriges kommuner och regioner], Citation2019). A contributing factor is said to be that there are too few TEs having a digital competence for applying digital technology and teaching about digitalisation in education. Digital competence now including knowledge, attitudes, and skills in five areas of competency – data processing, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, and problem solving – each with eight proficiency levels (European Commission, Citation2017). Going from being not only a solely operational and technical “know-how” focus on technology use but instead an inclusion of more knowledge-oriented, cognitive, critical, and responsible perspectives on digitalisation in society. Previous research proves a strong, positive correlation between TEs’ digital competence and pre-service teachers’ ability to learn a subject and the subject-specific didactics (Krumsvik, Egelandsdal, Sarastuen, Jones, & Eikeland, Citation2013). Research in general advocates the fostering of digital competence in teacher education, demonstrating that new examined teachers have their future pupils’ knowledge and interest as a priority and are willing to try new forms of information and communications technology (ICT) when teaching (Martinovic & Zhang, Citation2012) and also that pre-service teachers’ levels of technology and pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) significantly affect a pre-service teacher’s self-efficacy in learning environments with new learning technologies and media (Joo, Park, & Lim, Citation2018).

University teachers have a work environment that traditionally is characterised by boundless work, flexible working conditions and professional autonomy however the last decades the influence of New public management (NPM) reforms have changed the work setting and the TE has lost e.g. the possibility of claiming what constitutes good work (quality control) (e.g. Ahlbäck Öberg, Bull, Hasselberg, & Stenlås, Citation2016; Kohtamäki & Balbachevsky, Citation2018). Digitalisation, being part of the transformation of higher education, has then created a demarcation problem in terms of previous working conditions, such as separating work and leisure, which in turn can affect the health. Previously, the academic world was perceived as a less stressful environment, but this has now changed in a negative direction (Watts & Robertson, Citation2011). In digital working life, the individual must take increasingly more responsibility for constructing their way forward. It is up to the individual, in general, to seek knowledge and to learn, to learn for work and life (Eteläpelto, Vähäsantanen, Hökkä, & Paloniemi, Citation2013; Roumbanis Viberg et al., Citation2019). Thus, TEs need support and professional development to improve their digital competence and in adopting technology for their teaching (Amhag et al., Citation2019). But it is necessary to investigate TEs’ perceptions, attitudes, and metacognitive skills in relation to innovation in teaching and professional learning to create adequate professional development (Uerz, Volman, & Kral, Citation2018). Uerz et al. (Citation2018) have suggestions on how the TE’s pedagogical-technical development can be promoted. The individual professional development of TEs is highlighted as an important factor in developing the ability to use technology for a learning purpose. First, the competence development efforts should be relevant and related to the own pedagogical context (e.g. Lim, Chai, & Churchill, Citation2011). Secondly, there should be collaborative elements and collaboration with colleagues and experts, both outside and within the own department (e.g. Reading & Doyle, Citation2013). The third factor is to create tailored competence development initiatives based on the interests and needs of the individual TE, creating a sense of high agency and autonomy. Finally, the fourth and final factor is reflection, that TEs are given the opportunity to reflect with others on their practice (e.g. Georgina & Olson, Citation2008). Jonker, et al. (Citation2018) point out that development efforts need to be based on the individual’s needs when, among other things, the teaching context changes, and this support cannot be of “one size fits all”. Amhag et al. (Citation2019) emphasise that in order to succeed with a competence development with a focus on digital tools in teaching, TEs need time to understand the benefits of teaching with digital technology.

Hökkä and Eteläpelto (Citation2014) argue further that the TE’s willingness to develop and adapt relates to how they exercise their agency, and this will influence the outcome. In this subject-centred socio-cultural (SCSC) approach, professional agency is seen as individual and exercised (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2013). Exercising agency enables individuals to affect their life: to make choices, take stances and try to influence the surrounding world. This is an approach conceptualised as a response to the current situation in many societies of today. It is an approach applied in studies that examine the TE’s agency, the individual’s involvement in processes of change, and their need to navigate new reforms and changing conditions, of great importance. Furthermore, when it comes to research into issues related to TEs’ self-knowledge, identity, and agency, there is less emphasis than on research into professional knowledge (Fairbanks et al., Citation2010; Hökkä & Eteläpelto, Citation2014). The work of a TE is described by Kosnik, Miyata, Cleovoulou, Fletcher, and Menna (Citation2015) as multifaceted and complex and there is a need for studies that examine “identities, practices, backgrounds, transitions, challenges, individual talents and contexts” .

Based on this background, this study aims to investigate professional agency in the context of higher education as manifested in TEs’ perceptions of their working life in a digital society. The study also seeks to obtain insights on salient factors influencing TEs’ professional agency and identity and also possible implications for professional development.

Theoretical framework

This section describes the theory of the subject-centred socio-cultural (SCSC) approach to professional agency that the study is based upon and the analytical concepts of professional agency, professional identity, and work practices.

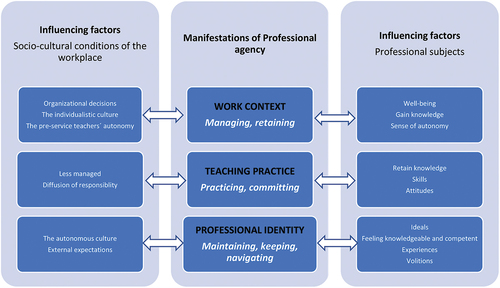

The concept of agency is multi-faceted, interdisciplinary, and defined in different ways depending on research discipline and ontological stance. With this varied view of the concept, however, there are two dichotomies that can be used to gain an overall theoretical perspective of the concept (Goller & Paloniemi, Citation2017). The first dichotomy is that agency can be understood as personal capacity (e.g. Harteis & Goller, Citation2014) or as a behaviour, something one has or does (e.g. Lipponen & Kumpulainen, Citation2011). The second dichotomy is that agency is either individual (e.g. Edwards et al., Citation2017) or collective (exercised by groups of individuals) (e.g. Hökkä, Vähäsantanen, & Mahlakaarto, Citation2017). In the SCSC-approach to professional agency, agency is seen as individual and exercised (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2013). Further, the subject-centred part of SCSC is needed in order for the individual not to be seen as a passive participant in a community, but instead as an individual, who in a socio-cultural context, is active in transforming their conditions (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2013). The individual’s (professional subject’s) professional identity, knowledge, competences, history, and experiences are as important as the sociocultural conditions of the workplace (the social reality we live in), that is situational, contextual and volatile (a temporal part) (See .). The two parts, the socio-cultural conditions and the professional subjects, are analytically separated but mutually constitutive. We argue that a SCSC approach to professional agency can help us understand the TE’s agency in their working life in a digital society, since digitalisation is a phenomenon of change with the potential to affect TEs’ conceptions of who they are professionally and the impact this has on pre-service teacher education.

Figure 1. Definition of professional agency within a subject- centred socio-cultural framework (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2013, p. 61)

Professional agency and identity

The TE’s profession is complex, consisting of many different roles, such as being a teacher, researcher, supervisor, administrator, and colleague. As a TE, professional agency is likely to be exercised within the classroom context and the teaching practice as well as in the work context and /or in relation to the professional identity (see ).

With a focus on understanding the duties and roles of a teacher within the higher education sector, it is necessary to understand who the TE is as a professional subject (Varghese, Morgan, Johnston, & Johnson, Citation2005). The TE is often alone in the classroom context and makes many instantaneous decisions in these teaching situations, based on work experience and professional identity (Gandana & Parr, Citation2013). In the teaching practice, the TE exercises professional agency that involves making decisions regarding content and the execution of instruction, but also when communicating and creating relationships with the students. In an increasingly digitalised society, this means teaching and interacting with the students both in the classroom and online (Jääskelä, Häkkinen, & Rasku-Puttonen, Citation2017). When it comes to processes of change in teacher education, such as digitalisation, it is the TE who is directly involved with what is to be changed, which means it is important to make visible the professional subject’s thoughts, opinions, and actions in understanding the changes made.

The TE also exercises professional agency in relation to the community and the organisation. This agency has to do with influencing, taking stands and making choices regarding the content and conditions for one’s work (Vähäsantanen, Citation2015). For the TE, being able to exercise such professional agency is then important. They want to feel an organisational affiliation and satisfaction at work, at both an individual and a social level (community, organisation). This is also a prerequisite for developing educational and workplace practices, according to Vähäsantanen (Citation2015). Related to the digitalisation of higher education, the use of digital resources is made mandatory by top-down decisions which affect the individual’s development and productivity and, among other things, the ability to exercise professional agency (Castañeda & Selwyn, Citation2018; Madsen, Archard, & Thorvaldsen, Citation2018; Tomte, Enochsson, Buskqvist, & Karstein, Citation2015).

Finally, professional agency is closely related to professional identity, an identity which is the individual’s self-perception as a professional actor including the individual’s interests, ideals, commitments and goals (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2013). It is an identity that is shaped by the TE but also given to them by others, based on their professional role and work contexts. Exercising professional agency is considered a fundamental factor in transforming one’s professional identity, in being able to follow the changing workday settings (Ybema, Yanow, Wels, & Kamsteeg, Citation2009).

Method

To investigate TEs’ perception of professional agency, semi-structured interviews with TEs from four universities in Sweden were carried out. Previous analysis of the same data demonstrated that TEs perceive themselves as being located in the intersection of requirements and inner demands that give rise to needs and consequences and a desire to learn and be autonomous (Roumbanis Viberg et al., Citation2019). The aim of the present study is to focus on TEs’ perceived professional agency in the intersection mentioned above and thus broaden the knowledge of the TE profession in a digital working life.

Data was collected from the four universities in June 2017, based on the ethical principles of (a) respect (b) competence (c) responsibility, and (d) integrity (Swedish Research Council, Citation2017). These were university colleges and universities that differ in contextual aspects: geographical location, number of beginner students (from ca 300 to 1200), structure of the program, and the profile of the university. Due to the ethical considerations of anonymity, we have chosen not to provide any more information about the universities. In 2017 there were differences in the digital infrastructure that easily would expose a given university. All universities had, at the time, a policy for digitalisation of higher education and have had workshops for the TEs.

The study involves 18 TEs working at universities with primary teacher education programmes for grades 4–6. They represent different subjects, disciplines, and departments. See for further information on the participants.

Table 1. The participating TEs.

Criterion sampling was applied for gaining information-rich cases and maximum variation. Altogether there were 49 TEs contacted via email. Eighteen of them were finally interviewed. The drop in number was due to various circumstances such as illness and time constraints. The interviews took place at the participants’ universities, except for two participants, where one interview was done over the phone and one at another university. The participants signed an informed consent form before the interview. All interviews were carried out behind closed doors in offices or the equivalent to ensure a safe environment for the participant and to avoid disturbances. All interviews were conducted by the first author.

The TEs were invited to the interview with the heading “The TEs working life in a digital society”, this in an attempt to investigate how the TE perceived his/her working life and what place digitalisation had in a workday. The structure of the interviews, with open-ended questions, was designed to investigate the assignment, meeting students, teacher education being part of higher education. The interviews ended with an invitation freely to reflect upon four vignettes (four quotes), representing statements related in one way or another to a broader perspective on the digitalisation of teacher education, higher education, and contemporary society. The use of vignettes was to assure digitalisation was a topic raised during the interview, framing digitalisation. Vignettes can be a way of exploring the interpretative practices of participants (Jenkins, Bloor, Fischer, Berney, & Neale, Citation2010); therefore, they were of importance for this study. Three of the vignettes were identical for all participants: one was from the Swedish Higher Education Ordinance, concerning IT being an essential part of teacher education in phase with the digital developments in society and in the school system; one was from a research article concerning the lack of digital competence in teacher education; and one was from a survey-report done by a market research company investigating how pre-service teachers perceive their education from the perspective of digitalisation. The fourth vignette was a quote taken from the participants’ universities’ goals and vision for the future, a future of globalisation, new learning environments, and rethinking education. A majority of the participants did not mention digitalisation before the reflections on the vignettes and when mentioned, the TEs had more of a pragmatic perspective, linking digitalisation to their daily work in teacher education. During the last part of the interview, the participants were given the opportunity to add to or comment on the topics discussed. The duration of the interviews was between 50 and 75 minutes (in total 18 h, 20 min) and they were recorded with a Dictaphone and transcribed verbatim, comprising 281 pages of transcription.

In order to investigate the professional agency manifested in the TEs’ perceptions, qualitative content analysis with a directed approach was conducted (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). A directed approach is used when existing theory or theoretical concepts are the basis for structuring the initial analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) and when the goal of the analysis is to extend or conceptually validate a theory or theoretical framework (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008). In this study, the SCSC approach and definition of professional agency (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2013) (), is used for creating an initial, structured coding matrix with the following three coding categories (a) professional agency in the work context (b) professional agency in teaching practices and (c) professional agency in negotiation and renegotiation of professional identity. Similar to Hsieh and Shannon (Citation2005) process of analysis, the analysis started with a direct approach reviewing all transcripts carefully several times, identifying and highlighting meaning units related to digitalisation. Using the directed approach, highlighting units of representative text has been done before coding, thus increasing trustworthiness and the chance of capturing possible occurrences of the phenomenon under study, here professional agency. The identified units were then condensed and abstracted into codes, the manifested content (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004), and coded using the three initial coding categories. This process of condensing codes and categorising was thorough and iterative. The analysis procedure continued by asking the questions how, why, and when the TE perceives a sense of agency and whether it could be interpreted as a sense of high or low agency. This was done to examine and determine subcategories, relations between codes, and the latent content (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004). A subcategory consists of codes concerning the same area of interpreted meaning. This resulted in manifestations of agency, such as “managing the workday” and “retaining autonomy” and factors influencing their professional agency, such as the “work community” and the “pre-service teachers’ autonomy”. Representative excerpts are used to illustrate the content and meaning of each subcategory in the result section. The excerpts are labelled with the number of the interview corresponding to the interviewed participant.

The first author had the responsibility for the study. The co-authors have participated and contributed to developing the interview guide, the analysis, and writing the article, which is considered to contribute to the study’s trustworthiness and rigour.

Results

Professional agency in the work context

The TEs’ sense of professional agency in the work context is manifested in two categories: (a) managing the workday (b) retaining autonomy.

Managing the workday

This subcategory addresses the way TEs’ expressed their professional agency in relation to the shared digital resources of the workplace. It was an agency exercised for the purpose of mastering their work, i.e. in the community and organisation.

Top-down decisions, demands from the school practice/society and inner demands of responsibility regarding the use of shared digital resources primarily influence the TE’s ability to exercise professional agency in relation to their daily work. There is a lower sense of agency when it comes to having a mandate to choose what digital resources to use in their daily work. This is because the TEs have little or no influence over the implementation of digital systems and resources for administrative and teaching purposes that just increase in number. There are systems to administrate, syllabi to write/revise, rooms to book, travel to report and employment issues to resolve, and platforms such as the learning management system (LMS) that are said to frame the workday. For the TE, it is necessary to be able to deal with all these systems in order to manage their work; otherwise, they end up on the outside, which is not negotiable: “More and more of these programs we have to master” (14).

The TEs perceive an increase in responsibility and workload due to the implementation of digital systems with new administrative tasks, which create more work and are time-consuming, as this excerpt illustrates:

There is more of a focus on administration, sitting at the computer and punching in things like schedules, registering [data] in [a student administration system] and so on that I haven’t done previously but that I am responsible for doing now. (4)

Using these digital systems is further perceived as demanding in different ways. There can be schedules and room bookings that collide, assessment-tool hassles, and many, often long email conversations with students, management, and co-workers, that must be answered. This is perceived as causing stress, creating a sense of low agency for the TE in that the administrative tasks take precedence over the process of teaching. Nor has there been time for digital skills development. The TE says that learning the systems is being done while other tasks are dealt with. Exercising agency then becomes a matter of making choices and prioritising tasks based on what is most critical for managing the individual tasks of the day. In an attempt to exercise agency, choices are made such as, “I use as few as possible of the modules in the platform, those that I know how to use” (1) and “I don’t use the LMS in my teaching, I have just learned it and don’t know how to use it, have not mastered it at all” (10).

It is also mentioned that the students’ avoidance of using the LMS reduces the TEs’ possibility to exercise agency, creating a sense of lower agency. For instance, when the students choose to use other online forums for information/communication among themselves, such as Facebook, “They don’t always use the discussion forum here, which I think they should”, (10) it often contributes to extra work and misunderstandings.

On the other hand, there are TEs that perceive the shared digital resources, e.g. web resources as valuable for the working community and as a possibility for working together. As far as being involved in courses goes, it is, for example, easier to see the progression of students’ learning, get continuous updates, and increase the possibility of influencing the course they are involved in. This is perceived as a higher sense of agency.

Retaining autonomy

This subcategory represents the TEs’ perception of exercising agency in retaining the autonomy prevailing within higher education due to the existing individualistic workplace culture. It is an autonomy which is said to create a freedom of choice and could be interpreted as having a Janus-faced nature, which one TE expressed as “a sort of line between enormous freedom, the possibility of creating one’s day-to-day life, feeling that one owns it, to winding up as self-employed [wondering] why am I sitting here with all this” (13). The TEs perceived autonomy as creating a professional space in which agency is exercised. When it comes to the digitalisation of the organisation on a more general level, there is a sense of higher agency for the individual in using the professional space, as in when they do take an active role in further developing their personal digital competence and digital approach at work.

Further, the TEs perceive that the opportunities to develop new knowledge are few, since the organisation provides vague guidelines and what they perceive as insufficient support and opportunities for skill development. They exercise their agency in establishing priorities and choosing where to then invest their efforts. Developing further digital skills will not be a priority in a working day where there is little room and support for developing and learning anything new and thus, they stick to the knowledge and skills they have: “everyone has their areas of competence, and one holds on to them tightly” (14).

Professional agency in the teaching practice

TEs’ sense of professional agency in the teaching practice is manifested in two categories: (a) practicing freedom and (b) committing to the task.

Practicing freedom

The exercise of agency is here used for practicing the freedom that autonomy is said to create. Within the teaching practice there are recipients; feedback is given to another extent, which will influence the sense of agency. The data reveals a mixed sense of agency among the TEs when it comes to being able to have an influence and take a position on the use of digital resources and promoting a digitalisation perspective in educating future teachers, in their teaching practice and duties as TEs. Agency is then foremost exercised from the individual TE’s perspective, as managing their own teaching. Some also voice exercising agency from a student perspective, being responsible for second order teaching, a transition from the self to the others.

The TEs perceive high agency in regard to their standpoint, which varies between not using digital resources at all to wanting to use more and additional digital resources in teaching. This variation and sense of professional space is said to be made possible by the fact that the teaching practice is not regulated; one can choose if, how, and with what resources teaching is to be executed. Those who perceive already having the necessary digital knowledge and skills are using digital resources in their teaching for different purposes, e.g. improving instruction, developing as a teacher, or adapting instruction based on external requirements of the workplace. Others are convinced that using digital resources in teaching contributes to a development of their own teaching practice in general, expressed by one TE this way:

The digital aspect is part of it and [I am] trying to comprehend how I can use it, both take advantage of it for my own sake, but also how I can bring it up and talk about it so that I’m making sense. (3)

Those TEs who express using digital technology frequently in their teaching find it inspiring, demonstrating a high sense of agency in that they express that they use, experiment and test digital resources as much as possible. For example, they are active in social media groups and experiment with embedding new elements in an instructional setting. They say that they make changes to their teaching to drive their own professional digital development forward.

Occurrences of TEs using digital resources in teaching from the perspective of a lower sense of agency are characterised by a feeling of compromise, must and adaptation. These TEs use the digital resources they are already familiar with, because there is a need, without perceiving that this adds anything significant to their teaching and they are critical and sceptical in comments such as “I think sometimes, was that an effective way to learn, maybe it was not” (12).

Those TEs who perceive themselves as not having the necessary knowledge, or the skills needed, exercise a higher sense of agency, and distance themselves by either avoiding the use of digital resources in their teaching or denying that they have this responsibility:

I think that there’s probably someone else who works with that, we have different parts of the program, some teach English and so on. We have slightly different areas and ICT, I don’t have much of that. (10)

Committing to the task

A TE’s work includes preparing their students for a professional life and giving them the opportunity to develop skills and abilities, including how to teach in digitalised classrooms. The assignment can frame the perceived professional space for the TE, making it smaller. The instruction then highlights different perspectives on using technology in the classroom.

The TEs in the study, perceive a lower sense of agency in relation to their duties as educators. Their commitment as TEs, in combination with lacking the adequate knowledge and skills, creates an inner demand and a sense of obligation. They then choose to do whatever requires the minimum amount of effort as one participant says: “I have pushed myself to be informed anyway” (17). However, in this perceived lack of knowledge for digitalised teaching, they consciously limit the use of digital resources. Nor have they acquired enough knowledge of how digitalisation influences individuals and learning, and the time to learn is limited. In this group of TEs there is a clear tendency towards change; they are prone to change, even though they experience a sense of lower agency. There is an understanding that digitalisation in education is important from the student perspective: “the students should have accomplished a great deal more digitally” (14), and the students are put first. The TEs choose, for example, to listen and adjust their instruction on behalf of the students “they think that they get too little instruction in the actual tools so now I have done something about that, but we only have time for one” (15). The feedback they get is used for change.

Professional agency in negotiation or renegotiation of professional identity

The professional identity as a teacher is dynamic and changes during a career. The TEs view themselves and their professional teacher identity linked to digitalisation as making choices, taking stances in relation to (a) maintaining ideals of learning and teaching (b) keeping current identity and knowledge and (c) navigating the responsibility.

Maintaining ideals of learning and teaching

Ideals of learning and teaching relate to the teacher identity and the TE as a professional. The TEs perceive that there is a professional space when it comes to the maintaining of subjective ideals and values of teaching within the teacher education program. A professional space is created by the sociocultural conditions such as subject positions, the work culture, and material circumstances. Within this space there is a sense of high agency and the TE seems to use scepticism as a tool for maintaining ideals. For instance, technology is said to have a negative impact on learning, or it is even considered to be a danger. There are also utterances questioning whether the use of digital resources can add anything or really contribute to learning and teaching. As one TE puts it:

How can I establish contact and communication, how does learning take place, and I mean otherwise we have reduced it to nothing, we might as well upload films of everything, it’s hard being a teacher, a good teacher, in these new media. (10)

This quote indicates that some experience difficulty in being a good teacher under these new circumstances. They become, among other things, “uneasy” (7), “skeptical” (15) and “hesitant” (3). The uneasiness is often used to enable an agency where one takes a stand against using digital resources or chooses to continue as usual until it is proven that they should do otherwise. There is also some doubt as to how the teacher education program should address digitalisation, which makes it feel safer for the TE to carry on with what they believe to be the best way.

Keeping current identity and knowledge

The TEs talk about negotiations, when it comes to feeling knowledgeable and competent as a teacher, being a professional. These negotiations are related to the individuals believing that they do not have the capacity to understand and learn how to use the digital resources, the mindset needed or the ability to acquire digital competence, as in this excerpt where the TE feels digitally illiterate:

I never manage that, everything gets mixed up, I don’t have the same logic as … this machine’s logical and I don’t have it, I am digitally illiterate. (18)

There are those that do not go as far as to describe themselves as digitally illiterate; however, they feel insecure and unsure whether they are capable of employing digital resources in their teaching in a qualitative, professional way. Therefore, they exercise agency by delaying an implementation.

Furthermore, the TEs say that they are not prepared to invest time and effort in learning something new. This is referred to in different ways: “laziness” (18) or a “waste of energy” (10). There is a change fatigue visible among these educators which make them rely on their professional knowledge being adequate and useful. Other reasons for relying on their existing knowledge concern a lack of time, opportunities for professional development or that they can manage by choosing to get help from others. Thus, their reasons for exercising their agency, having this sense of high agency, relate to maintaining their current identity as teachers.

Navigating the responsibility

The TEs talk about their professional commitment in relation to the professional identity and what it means to have the responsibility for educating future teachers. This evokes urgent feelings to negotiate what a TE should be and do as well as what knowledge is valid within a teacher education program. But in contrast to the commitment to the assignment, when it comes to negotiating with one’s professional identity in relation to the responsibility as a TE, the professional space is perceived to be wider.

There are TEs that seem to try to find their way and are prone to change. They exercise a higher sense of agency, bringing up that they master the task and have the necessary knowledge that the pre-service student needs. This allows for a sense of higher agency in an agreement to change of one’s own free will, which is then linked to the fulfilment of commitment as a teacher. This is expressed as wanting to be trustworthy, to be a role model.

Furthermore, they sense a lower agency in regard to changes in primary education, where they have not been active in recent years; their experiences of what goes on in schools nowadays are few. The fact that the school context has become increasingly digital and that there is a national requirement for the development of digital competence in teachers and pupils has resulted in a requirement for adjusting that becomes more acute and even more relevant. A renegotiation of the professional identity is then more likely to happen, and their sense of agency is lower. They talk of students’ expectations that the TEs have experience, mentioned as:

They […] and would like me to relate relevant experiences from schools, which is not really possible when one works the way we do, that the experience I have comes from my early days, today I have none left, it’s not as relevant. (9)

Since there are digital goals to achieve in the courses the TEs mention that the students can and will demand a relevant education and instruction preparing them for today’s working life. At the same time, it is harder to rely on their own experience of being a teacher and, by extension, also make decisions about what knowledge and skills the student should develop.

Discussion and conclusion

This study investigated 18 TEs’ professional agency in the context of higher education manifested in their perceptions regarding their working life in a digital society. Applying the subject-centred socio-cultural (SCSC) approach, the analysis also reveals the salient factors influencing the TEs’ professional agency exercised in the (a) work context, (b) teaching practice and (c) in relation to their professional identity ().

Figure 2. Manifestations of professional agency and influencing factors: (a) work context, (b) teaching practice, (c) professional identity

The results show that the TE exercises agency in the work context (first row in ) for purposes such as managing his/her work and retaining the autonomy that is perceived to exist within the individualistic working culture of higher education. The professional space is here perceived to be small, creating less room for the TEs influencing the choice of digital resources for their work due to the mandatory top-down decisions at the workplace. This limits the individual TE’s feeling of participation, managing work, and the ability to exercise professional agency. This space is also associated with “a must” in gaining new knowledge and adapting to such given circumstances, i.e. running the risk for non-productive or even absent development of the workplace as the Madsen et al. (Citation2018) study demonstrates. On the other hand, when it comes to decisions regarding if and when to develop their digital competence, the TEs perceive that they position themselves, making priorities not necessarily in line with the organisation’s – quite the opposite. This mainly concerns retaining the knowledge they have and taking responsibility for their own wellbeing. Here, even if the space is perceived to be wider, as Vähäsantanen (Citation2015) states: manifestations of professional agency may hinder the professional development of the organisation. When you combine vague guidelines/ goals and a high sense of autonomy with an evolving work context it is not that surprising that the TE exercise agency in different ways to delay a development. A work context being filled with new professional work tasks i.e. managing digital systems and with little time to learn new, practice, reflect and teach.

In the teaching practice (second row in ), the professional space is perceived to be wider since the culture creates autonomy and hence more freedom for exercising agency. Compared with what Ahlbäck Öberg et al. (Citation2016) argue, that the university staff has lost aspects of professional autonomy due to the NPM reforms, the results show that the majority of TEs perceive that there is an autonomy when it comes to using digital resources. This is probably because the digitalisation of teaching is perceived to be less controlled. You are given a “digital” autonomy. The exercise of agency is here influenced by e.g. the management of the teaching practice and the individual’s sense of obligation. In this space there is a freedom of choice and agency is exercised foremost as a way of managing work and keeping the professional identity as teacher, not developing as a teacher educator. For example, there are TEs who use and integrate the digital resources in their teaching practices primarily to manage their own teaching and to feel knowledgeable, not necessarily committing to the task, which is preparing the pre-service teachers for digital teaching. Amhag et al. (Citation2019) concluded that TEs who scaffold pre-service teachers’ digital teaching are primarily absent. Solutions provided by the authors concern requiring extensive and continuous pedagogical support and seeking to make the TEs identify the added value of digital resources in their teaching and in the learning context. The results from our study show that even if you give TEs support, it does not necessarily have any major impact on the individual if they choose not to use digital resources and to exercise an agency that goes in the opposite direction. This implies a need for balance between the given autonomy and the individual’s sense of high agency. In order to address the complexity and create a balance the university organisations need to communicate clear and feasible digital guidelines, provide personalised professional development and give the TEs time to test/explore by themselves and with others, to find the added value when combining reflection with action. Give the TEs a possibility to exert influence, make choices and take stances, a higher sense of agency, within certain boundaries and with support.

Finally, in regard to professional identity (last row in ), the TEs perceive a higher sense of agency in maintaining the ideals of learning and keeping their current teacher identity but a lower sense of agency in navigating the responsibility as a TE. Influencing factors are e.g. external expectations, personal beliefs. As mentioned earlier addressing the TEs beliefs about teaching and learning is one important factor for the professional development for teaching and learning with technology (Uerz et al., Citation2018).

Furthermore, the study shows examples of TEs who choose not to use digital resources at all in their teaching practice, exercising high agency, relying on the competence present in the work community. In this diffusion of responsibility from the individual to the community (Bandura, Citation1991) the presence of others makes the individual feel less responsible for the consequences of their actions. The digitalisation of the teaching practice is a collective goal which makes the perceived professional space wider, which then makes it easier for the individual to exercise agency and decide where to direct their efforts. Using the work community can also be an expression of maintaining the professional identity of the expert and using the community as a group of experts, where the one(s) who is/are best suited carries/carry out the task. As a TE you can then choose to use the community of TEs, to be part of/or not be part of the digitalisation of education. It becomes clear from the results that when the incentives to use digital resources are strong, when the autonomy is somewhat limited, when you as an individual teacher cannot manage your work without using digital resources, and when the professional space decreases, the use of these resources increases. The TEs then exercise agency, but it is about using resources, not about developing within the professional space. Many times, the preparation for digital teaching and development of digital competence only reaches a certain population of students as it depends on the individual TE’s digital approach, skills /competences and volitions.

To conclude, changes in education are nothing new; they are part of a teacher’s working life when societal processes of change such as digitalisation represents, affect our lives. The results of this study not only confirm the complexity of being a professional TE in these times of digitalisation but more importantly demonstrate a paradox in the TEs perceived high agency that both enables and hinders self-development (the individual) as well as the working community’s, the organisation’s, and the university’s development. The TEs feel they have a professional autonomy and space that in this study gave rise to exercising agency mainly to keep their current teacher identity and the practice being manageable. The study implies that considerations and understanding of the TE’s autonomy and perceived agency are significant for the professional and work development.

At the time of writing, during the Corona pandemic, the conditions for the Swedish TEs exercising agency in their work context and in their teaching practice has resulted in a rapid transformation of online teaching. From having experienced foremost a sense of high agency in their own teaching practice regarding the use of digital resources, all higher education professionals are now expected to turn entirely to digital forms of teaching, thus conducting teaching and working online. The professional space has decreased, which raises the necessity to further explore and analyse the consequences and outcomes for professional agency and identity in the transformation of the workday e.g. the exercise of professional agency and renegotiations of professional identity of working in an online environment, the increased forced digital competence effect on sense of agency. This study also indicates that it would be interesting to further investigate how to design a digital organisational development that contributes to a sense of high professional agency.

Limitations

The limitations of this study concern the number of participants and the fact that the educational context is only one country, Sweden. The findings of this qualitative study thus cannot be generalised across a population or in other national contexts, but rather to explore manifestations of agency in the TE’s perceptions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating teacher educators for their interest, and for bringing valuable insight into the researched matter.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna Roumbanis Viberg

Anna Roumbanis Viberg, PhD student in Education with a specialization in work-integrated learning at University West, Sweden. Her main research interests are how digitalization of society affects the teacher educator´s professional development, agency, and identity.

Karin Forslund Frykedal

Karin Forslund Frykedal, PhD, Professor of Education at University West, Sweden. Her scientific activity lies within both the educational and the social psychological research field with a strong focus on group research mainly connected to groups, group processes, learning and education.

Sylvana Sofkova Hashemi

Sylvana Sofkova Hashemi, PhD, Professor in Digital Learning at Halmstad University and Associate Professor at University of Gothenburg. Her research is devoted to design-oriented research developing technology-mediated teaching and learning, teachers’ professional development, multimodal literacy and text competencies in today's media landscape.

References

- ,Swedish Research Council [Vetenskapsrådet]. (2017). God forskningssed (Good research practice). Retrieved from https://www.vr.se/analys/rapporter/vara-rapporter/2017-08-29-god-forskningssed.html

- Ahlbäck Öberg, S., Bull, T., Hasselberg, Y., & Stenlås, N. (2016). Professions under siege. Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 118(1), 93–126.

- Amhag, L., Hellström, L., & Stigmar, M. (2019). Teacher educators’ use of digital tools and needs for digital competence in higher education. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 35(4), 203–220.

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287.

- Castañeda, L., & Selwyn, N. (2018). More than tools? Making sense of the ongoing digitizations of higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, (15), 26.

- Castells, M. (2000). Informationsåldern. Ekonomi, samhälle och kultur. Band I: Nätverkssamhällets framväxt.[The information age: Economy, society and culture. Volume I: The rise of the network society] . Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Demoskop. (2016). Teacher education and digitalization - a survey among Sweden’s teacher students. Retrieved from Online: http://www.berattarministeriet.se/undersokning/

- Edwards, A., Montecinos, C., Cádiz, J., Jorratt, P., Manriquez, L., & Rojas, C. (2017). Working relationally on complex problems: Building capacity for joint agency in new forms of work. In Agency at work (pp. 229–247). Cham: Springer.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115.

- Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review, 10, 45–65.

- European Commission. (2017). Digital Competence Framework for citizens, DigComp 2.1. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/digcomp

- European Commission. (2018). Communication from the european commission to the european parliament, the council, the european economic and social committee and the committee of the regions. on the digital education action plan. SWD (2018) final. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2018:0022:FIN:EN:PDF

- Fairbanks, C. M., Duffy, G. G., Faircloth, B. S., He, Y., Levin, B., Rohr, J., & Stein, C. (2010). Beyond knowledge: Exploring why some teachers are more thoughtfully adaptive than others. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(12), 161–171.

- Gandana, I., & Parr, G. (2013). Professional identity, curriculum and teachingIntercultural Communication: An Indonesian case study. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 26(3), 229–246.

- Georgina, D. A., & Olson, M. R. (2008). Integration of technology in higher education: A review of faculty self-perceptions. The Internet and Higher Education, 11(1), 1–8.

- Goller, M., & Paloniemi, S. (2017). Agency at work, an agentic perspective on professional learning and development. Cham: Springer.

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112.

- Gudmundsdottir, G. B., & Hatlevik, O. E. (2017). Newly qualified teachers’ professional digital competence: Implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2), 214–231.

- Harteis, C., & Goller, M. (2014). New skills for new jobs: Work agency as a necessary condition for successful lifelong learning. In Promoting, assessing, recognizing and certifying lifelong learning (pp. 37–56). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hökkä, P., & Eteläpelto, A. (2014). Seeking new perspectives on the development of teacher education: A study of the Finnish context. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(1), 39–52.

- Hökkä, P., Vähäsantanen, K., & Mahlakaarto, S. (2017). Teacher educators’ collective professional agency and identity – Transforming marginality to strength. Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 36–46.

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

- Jääskelä, P., Häkkinen, P., & Rasku-Puttonen, H. (2017). Teacher beliefs regarding learning, pedagogy, and the use of technology in higher education. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 49(34), 198–211.

- Jenkins, N., Bloor, M., Fischer, J., Berney, L., & Neale, J. (2010). Putting it in context: The use of vignettes in qualitative interviewing. Qualitative Research, 10(2), 175–198.

- Jonker H., März V., and Voogt J. (2018). Teacher educators' professional identity under construction: The transition from teaching face-to-face to a blended curriculum. Teaching and Teacher Education, 71 120–133.

- Joo, Y. J., Park, S., & Lim, E. (2018). Factors influencing preservice teachers’ intention to use technology: TPACK, teacher self-efficacy, and technology acceptance model. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 21(3), 48–59.

- Kohtamäki, V., & Balbachevsky, E. (2018). University autonomy: From past to present. Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives on Higher Education Management and Transformation: An advanced reader for PhD students.

- Kosnik, C., Miyata, C., Cleovoulou, Y., Fletcher, T., & Menna, L. (2015). The education of teacher educators, In Handbook of Canadian research in initial teacher education (pp. 207-224).Ottawa: Canadian Association of Teacher Education.

- Krumsvik, R. J., Egelandsdal, K., Sarastuen, N. K., Jones, L. Ø., & Eikeland, O. J. (2013). Sammenhengen mellom IKT-bruk og læringsutbytte (SMIL) i videregående opplæring. Retrieved from Bergen http://www.ks.no/PageFiles/41685/Sluttrapport_SMIL.pdf

- Lim, C. P., Chai, C. S., & Churchill, D. (2011). A framework for developing pre‐service teachers’ competencies in using technologies to enhance teaching and learning. Educational Media International, 48(2), 69–83.

- Lipponen, L., & Kumpulainen, K. (2011). Acting as accountable authors: Creating interactional spaces for agency work in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 812–819.

- Madsen, S. S., Archard, S., & Thorvaldsen, S. (2018). How different national strategies of implementing digital technology can affect teacher educators. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 13(4), 7–23.

- Martinovic, D., & Zhang, Z. (2012). Situating ICT in the teacher education program: Overcoming challenges, fulfilling expectations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(3), 461–469.

- Reading, C., & Doyle, H. (2013). Teacher educators as learners: Enabling learning while developing innovative practice in ICT-rich education. Australian Educational Computing, Special Edition: Teaching Teachers for the Future Project, 27(3), 109–116.

- Roumbanis Viberg, A., Forslund Frykedal, K., & Hashemi Sofkova, S. (2019). Teacher educators’ perceptions of their profession in relation to the digitalization of society. Journal of Praxis in Higher Education, 1(1).

- Selwyn, N. (2016). Is technology good for education? Cambridge: Polity.

- Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions [Sveriges kommuner och regioner]. (2019). Nationell handlingsplan för digitalisering av skolväsendet (National action plan for digitalization of the school system). Retrieved from #skolDigiplanwebsite:

- Swedish National Agency of Education [Skolverket]. (2017). Få syn på digitaliseringen på grundskolenivå – Ett kommentarmaterial till läroplanerna för förskoleklass, fritidshem och grundskoleutbildning. Retrieved from https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=3783

- Tomte, C., Enochsson, A. B., Buskqvist, U., & Karstein, A. (2015). Educating online student teachers to master professional digital competence: The TPACK-framework goes online. Computers & Education, 84, 26–35.

- Uerz, D., Volman, M., & Kral, M. (2018). Teacher educators’ competences in fostering student teachers’ proficiency in teaching and learning with technology: An overview of relevant research literature. Teaching and Teacher Education, 70, 12–23.

- Vähäsantanen, K. (2015). Professional agency in the stream of change: Understanding educational change and teachers’ professional identities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 1–12.

- Varghese, M., Morgan, B., Johnston, B., & Johnson, K. A. (2005). Theorizing language teacher identity: Three perspectives and beyond. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 4(1), 21–44.

- Voogt, J., Fisser, P., Pareja Roblin, N., Tondeur, J., & van Braak, J. (2013). Technological pedagogical content knowledge–a review of the literature. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29(2), 109–121.

- Watts, J., & Robertson, N. (2011). Burnout in university teaching staff: A systematic literature review. Educational Research, 53(1), 33–50.

- Ybema, S., Yanow, D., Wels, H., & Kamsteeg, F. H. (2009). Organizational ethnography: Studying the complexity of everyday life. London: Sage Publication.