ABSTRACT

Despite the expanding literature in the last three decades on modes of implementation and the various forms of formal and informal assessments, there is limited evidence of academics’ knowledge and understanding of continuous assessment practice. Using a mixed methods sequential explanatory research design, this paper aimed to investigate academics’ knowledge and understanding of the structure of continuous assessment and its application in supporting students’ learning experiences at a South African University of Technology. The results of this study provide the basis to initiate deeper discussions on developing shared understandings of assessment literacy, assessment bunching, and assessment validity and reliability. These elements are all required for the enhancement of quality assurance and monitoring of fit for purpose continuous assessment practices.

Introduction

It is well-documented in the literature that modes and methods of assessments vary according to the diversity of teaching methods employed (Al-Kadri, Al-moamary, Roberts, & Van der vleuten, Citation2012; De Lisle, Citation2015, Citation2016; González, Citation2011; Kreber, Citation2009; Newton, Citation2007; Popham, Citation2009; Richardson, Citation2015; Simper, Citation2020; Trigwell & Ashwin, Citation2006; and others). Assessment of learning is therefore inextricably linked with pedagogy and the intended learning outcomes. Teachers using a conceptual change/student-focus teaching approach tend to use alternative classroom based practices such as simulations and discipline-specific games to stimulate students’ thinking, while encouraging them to construct or change their conceptions of the subject matter (Ashwin, Citation2009; Lindblom-Ylanne, Trigwell, Nevgi, & Ashwin, Citation2006; Vahed, McKenna, & Singh, Citation2016). Such teaching approaches are built upon the premise that when students are able to see and explore the relationships between their understanding of a subject and the application of such knowledge to discipline-specific and other contexts, higher quality-learning outcomes can be attained. Using the discipline of law as an exemplar, Donald (Citation2009, p. 42) advised that optimised teaching methods through early apprenticeship or simulations of moot court cases can encourage students to examine not only legal content, but the social context in which such content is applied. Such learning experiences can also foreground for students the principles needed to guide them in their thinking within and around their profession, and to enable them to appreciate the purpose of values in their personal and professional lives. Donald’s advice is aligned with the advice given by the Council on Higher Education that assessment is “more authentic when it directly answers how well a student is able to perform tasks that are intentionally demanding and reflective of the real world in which such students will one day operate” (Council on Higher Education, Citation2009, p. 7).

In the midst of the diversity of teaching methods and pedagogical intentions in higher education, it is critical that methods of assessment are aligned to modes of learning and intended learning outcomes. In general, the type of institution and the subjects offered within curricula influence the relative contribution of coursework to a final course mark, ordinarily varying in proportion to its conceptual value as an indicator of total student learning (Downs, Citation2006). While examinations are perceived to be a more reliable form of testing students’ knowledge and understanding than coursework, there are discrepancies in the types of questions asked in comparison to what students have been exposed to during the teaching and learning of subject content in the classroom (Al-Kadri et al., Citation2012; Muskin, Citation2017; Newton, Citation2007; Simonite, Citation2003). Downs (Citation2006, p. 346) therefore queried whether examination questions (focused on content) influence students to use more of a rote learning approach, considering that their “performance is viewed against criteria that may vary greatly between institutions”. Building on this contention, and also acknowledging that “assessment of learning” has a critical role in higher education, Beets (Citation2009, p. 196) questioned the extent to which students are being supported (through teaching and assessment) “in developing the acquired applied competence they themselves and the world at large needs”. Yorke (Citation2009) and Beets (Citation2009) posited that one way of optimising students’ engagement is using appropriate pedagogies that reconcile ‘Mode 1ʹ disciplinary knowledge and ‘Mode 2ʹ knowledge from real life application where solutions are required for complex problems. In response to this, higher education institutions such as the Durban University of Technology (DUT), where this research was conducted, are revising their mission statement(s) to reflect the reconciliation between Mode 1 disciplinary knowledge and Mode 2 trans-disciplinary application of knowledge (Durban University of Technology, Citation2020). This revision is significant, given that South African Universities of Technology (UoTs) “focus on service to industry and transfer of technology, as well as the preparation of a new generation of critical thinking citizens and lifelong learners”(Garraway et al., Citation2019, p. 119).

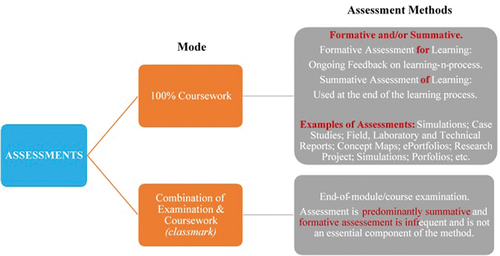

Notwithstanding the burgeoning literature in the last three decades on modes of implementation of the various forms of assessments (), there is relatively limited evidence of “a coherent and universally recognised theory that can explain and predict the impact of formative or for-learning assessment practices on learners and learning” (Cookson, Citation2018, p. 930). The earlier work of Hernández (Citation2012, p. 499) attributes this to the “double function” of formative and summative assessments in students’ learning. This refers to assessment tasks having both formative feedback “for learning” and summative grading “of learning” to pass a module/course. Hernández (Citation2012) therefore recommended that as part of feedback, a “feed-forward” component be implemented for students to be clear on what they have to do with all feedback received during the various components of assessment in order to improve their work and effectively support their own learning. The concept implies an ongoing purpose of formative assessment input in facilitating and guiding learning towards the formal demonstration of achieved learning in summative assessment. This is commonly typified as continuous assessment (CA).

Although definitions of CA vary, the interplay of formative input and summative assessment finds resonance (at least in concept) within DUT and other South African universities. A particularly clear articulation of a prevailing South African expression of CA is to be found in their Guidelines for Continuous Assessment, which states:

“A continuous assessment approach/model makes use of both formative assessment and summative assessment tasks.

Formative assessment uses student learning data to provide feedback to the students and lecturer in the teaching and learning process (Dunn & Mulvenon, Citation2009). Formative assessment provides regular progress updates for students through lecturer feedback. These tasks serve to scaffold student learning. Scaffolding means that each task builds on preceding tasks/learning to enhance understanding and to integrate learning. Formative assessment enables staff and students to identify and close learning gaps. This is known as assessment for learning.

Summative assessment uses student learning data to determine academic progress at the end of a specified period. Its purpose is to assess the learning that has occurred in order to grade, certify or record progress (Dunn & Mulvenon, Citation2009; Harlen & Deakin, Citation2002). Summative assessments determine whether students have met performance requirements on aspects of a module in a specific study period.

As a footnote to the identification of both formative and summative assessment being intrinsic componentws of the model, it is stated that “all assessment, whether formative or summative, is designed to improve learning. However, formative assessment is primarily diagnostic, while summative is an evaluation of the sum of students’ learning” (University of Johannesburg, , Citationn.d.).

The lessons shared from the various teaching and learning case studies by the South African Council on Higher Education (Citation2010) cautions academics against the extensive use of CA with a summative function within an undergraduate course/module, as they will experience heavy marking loads. Students, in turn, equally experience an assessment overload. More recently, similar results were cited in a study conducted in Ethiopia where instructors experienced heavy workloads that were exacerbated by large class size, lack of teaching materials and institutional resources (Tarekegne, Citation2019). Consequently, the desired assessment objectives are not achieved, for example providing students with effective feedback.

Additionally, and in view of the emphasis on knowledge, skills and application, academics need to encourage students to reflect on their own learning and take greater responsibility in the overall feedback process. For example, Hernández (Citation2012, p. 500) posited that technology such as online management systems (Blackboard or Moodle) can provide prompt feedback to students and can lead to “feedforward” for them to take prompt action to improve their work. This learning-orientated approach to assessment highlights that feedback dialogue between academics and students is critical for students to “become aware of how the feedback can influence positively on their learning” (Hernández, Citation2012, p. 501). Similarly, Reimann and Sadler (Citation2017) asserted that feedback dialogue between academics and students is a necessary condition for students to have meaningful and constructive learning experiences. Turner and Briggs (Citation2018) found that when students are provided with detailed feedback, future performance in other assessments improve. In particular, in-depth learning is achieved when acquired knowledge is actively used as a tool, with students being able to demonstrate not only what they know, but also what they can do with that knowledge. Ultimately, and as alluded to by the ongoing higher education debates, if assessment is to serve its purpose(s), it is incumbent on academics to have a thorough understanding of their institution’s assessment practices prior to its application (De Lisle, Citation2016; Muskin, Citation2017; Pauli & Ferrell, Citation2020; Simper, Citation2020; Walker et al., Citation2019).

Early indications of the challenges with continuous assessment at DUT

In 2005 the Durban University of Technology (DUT) assessment policy officially recognised CA as a mode of assessment, notwithstanding the inclusion of scant guidelines on the assessment and moderation practices specific to CA. Concerningly, the relative lack of guidance (vis à vis those for formal written tests and examination) continues into the current Assessment Policy (Durban University of Technology, Citation2019). Consequently, and agreeing with Basson (Citation2007), DUT academics could find it challenging to implement new assessment practices, which may be in conflict with their own philosophies and/or are embedded in the traditional assessment paradigm. Another consequence is that academics could continue to use outdated assessment methods or apply a hybrid practice that has been derived from a range of different assessment practices. Such challenges became apparent in discussions within the Faculty of Health Sciences (Citation2014a , Citation2014b) on the curriculum renewal project. Academics shared similar challenges reported by other authors (Abera, Kedir, & Beyabeyin, Citation2017; Bjælde, Jørgensen, & Lindberg, Citation2017; Simper, Citation2020). For example, academics pointed out that the assessment overload in the CA system made students increasingly anxious as the time available to prepare for successive assessments decreased. Consequently, cheating and plagiarism increased. Large class sizes also made feedback to students difficult and time-consuming. Modularisation further exacerbated this as pressue to complete “smaller” modules in tighter time frames created little time for formative feedback to be provided and acted upon. Equally concerning, the assumption that academics engaging in CA practices are competent detracts from the need to appropriately train them. Inevitably limitations on training of academics in CA (as a component of continuous professional development) has led to missing the learning-oriented aspects of formative assessment, and irregular and educationally unsound application of make-up tests.

In addition, an analysis of departmental handbooks within the FoHS revealed inconsistencies in the structure and application of CA in both theory and practical assessments across programmes. There were also programmes which offered a combination of CA modules and examination modules within the same academic level. Hernández (Citation2012) cautioned that the inability to balance the variety and number of assessments could negatively influence the outcomes. Following on from this, Amador, Martinho, Bacelar-Nicolau, Caeiro, and Oliveira (Citation2015) argued that an essential prerequisite for curricular assessment is to develop academics’ abilities, which should be complemented with research on pedagogical approaches and its effectiveness in delivering subject content within programmes. Muskin (Citation2017) thereafter asserted that pertinent questions should be raised when using various guiding principles to develop CA practices. For instance, academics should probe the extent to which their assessment methods are “fit for purpose”. In other words, does assessment align with the curriculum and is it fair and/or authentic? This relates to assessment reliability and validity. Reliability is about the extent to which an assessment can be trusted to give consistent information on a student’s progress (does the assessment give a consistent outcome across multiple measures?). Validity, an over-arching concept, is about the assessment measuring content which is considered important to measure (does the assessment measure what it is intended to measure?). Whatever the clichés that exist around assessment, validity and reliability should preoccupy academics’ understanding of assessment at every level (Harris, Citation2017).

In concept, CA practices should provide the necessary feedback and guidance to students such that they can engage in meaningful learning and an objective determination of learning achieved. Even though the purpose of assessment is to ensure that students understand the underpinning theory, apply it in authentic context, and are able to reflect on what they are doing, and why (South African Qualifications Authority, Citation2005), it is equally critical that assessment practices are aligned to teaching and learning outcomes, are implemented for maximal effect, and are valid and reliable. This paper therefore aimed to investigate academics’ knowledge and understanding of the structure of CA in the FoHS and its application in supporting students’ learning experiences at DUT. It was anticipated that the results would serve to inform future assessment policy and improve assessment structures that are fit for purpose. The overarching question in this paper is: How, and to what extent, are CA processes and practices supporting student-learning outcomes?

Materials and methods

Design and sample

A mixed methods sequential explanatory research design (QUAN → qual) following a pragmatic paradigm was used. Creswell (Citation2014) clarified that pragmatists do not see the world as an absolute inquiry; they are driven to use multiple methods, to hold different worldviews, and different assumptions when collecting and analysing data. A hallmark of the above research design is that the results of the quantitative phase informs the interview questions for the subsequent qualitative phase. Ethical clearance and permission to conduct the study was obtained from DUTs Institutional Research Ethics Committee (IREC 038/15). Informed consent was further obtained from academics who participated in the study. Purposive sampling techniques were used for the first quantitative phase.

Data collection and analysis

Academics (n = 85) teaching in the undergraduate programmes in the FoHS completed an anonymised and descriptive questionnaire between August and December 2016. As presented in , the majority of the male and female participants in this study were between 40–49 years of age, reflecting the middle age structure of the population. In terms of the four major racial groups in South Africa (Statistics South Africa, Citation2011), the largest group in this study was the Indian population, followed by the African, White and Coloured population groups. The majority of respondents hold a postgraduate qualification (81.3%), which aligns with the conditions of employment at DUT.

Table 1. Participant gender distribution by age group and race categories.

The questionnaire consisted of two sections: Section A focused on demographic details; Section B used open- and closed-end questions to elicit academics’ knowledge and understanding of the structure of CA and its application. Data was analysed using descriptive (univariate and bivariate analysis) and inferential (Correlations and Chi Square Test) statistics with p < 0.05 set as statistically significant (SPSS-Version 26®). Factor Analysis was performed for the data obtained from the Likert Scale to identify underlying variables, or factors, and to explain the pattern of correlations within a set of observed variables. The questionnaire was reviewed by a panel of five experienced academics for face and content validity. Reviewers provided feedback on their understanding of the statements related to CA as a method of assessment in Q12 and modifying the language used in Q13. For example, the word “learners” was replaced with “students”. The internal consistency of the survey was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha.

For the second qualitative phase, academics were randomly selected from the sample population used in the quantitative phase. The inclusion criteria for selecting interviewees were based on academics having five or more years of experience in teaching and who were using CA for 50% or more of the assessments in their subjects. The second author conducted face-to-face interviews with academics (n = 9) during October 2018 using semi-structured interview questions. A critical point worth noting is that the concept of data saturation was used, which according to Corbin and Holt (Citation2011, p. 116) is the “point in the research process when the researcher determines the categories are fully developed in terms of their properties and dimensions”. Interview questions allowed academics to comment further on 1. the alignment of the CA practices with institutional guidelines and in supporting DUTs graduates attributes; 2. institutional support for CA implementation; 3. CA influence on the teaching and learning and assessment practices; 4. practical implementation of CA; and 5. CA as a preferred mode of assessment.

Audio-recorded discussions of the interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using the principles of thematic analysis as explained by Nowell, Norris, White, and Moules (Citation2017). Following the advice of Punch (Citation2014), thematic analysis of the textual data was conducted at two levels, namely deductively (the researcher brings in codes to the data) and inductively (arising from the data). The first level of coding was deductive, that is, codes were created. Coding included phrasing or paraphrasing the words of the participants to generate themes or categories. Based on these codes, mind maps were constructed to help cluster the data into themes. This represents inductive coding, as it was driven by the data. The authors initially coded individually and after a mutual debriefing (inter-coder reliability) they subsequently integrated the codes. Methodological and data triangulation techniques further aided in strengthening the reliability of the study.

Results

Following an analysis of the undergraduate modules/courses, summarises the extent to which CA is used by the twelve departments in the FoHS.

Table 2. Percentage of undergraduate programme modules using continuous assessment and/or examination in the FoHS.

With reference to the quantitative phase of the study, summarises the descriptive statistics of the background characteristics of the academics.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics.

The questionnaire response rate was 76% (n = 65). As shown in , the reliability scores for the Likert scale Questions 10, 12 and 14 ranged between α = 0.60 and 0.90, indicating consistency of scoring. Questions 11, 13 and 18 had lower than normal reliability scores. This could be attributed to the nature of the statements and the diverse understanding of CA, which Muskin (Citation2017) noted is characteristic of CA operating along two extremes, namely, the formal and structured and the more spontaneous and less structured methods.

Table 4. Reliabilities.

Despite a high percentage of academics (94%) perceiving CA to be an effective method of assessment (p < 0.001) with most of them (77.3%) understanding it (p < 0.001), 60% of academics did not use it. The results further revealed that 52.4% also found CA unsuitable for their programmes ().

As illustrated in , there were higher levels of agreement than disagreement on the different ways of acquiring knowledge about CA and its practices. In particular, significant differences were revealed as a high percentage of academics acquired knowledge about CA and its practices from the literature (83%; p = 0.002); from being mentored by senior staff (88%; p < 0.001); through discussions with other CA practitioners (84%, p < 0.001); and by seeking more effective ways of assessment (81%; p = 0.005).

With the exception of the statement “Summative assessment in CA is used to grade my students and contributes to the student’s readiness to progress to a next level” in Q13 of the questionnaire, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO > 0.50) and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (p < 0.05) test results indicated that the conditions to conduct factor analysis were satisfied (). It must also be noted that the items presented in were found to have communalities above 0.5, which is deemed to be acceptable as this indicates that the extracted components represents the variables well (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Citation2010).

Table 5. Factor analysis results.

Continous assessment as the preferred mode of practice by the faculty/institution was not significantly different (p = 0.061). A factor potentially affecting this is the increased workload associated with CA practices, with interview feedback supporting this perspective.

Four dominant categories emerged from the interviews, namely: institutional guidelines and engagement of assessment-specific concepts, principles and terminology; lack of logistical support; diverse assessment and re-assessment practices; and increased academic workload. Academics conveyed that CA:

… impacts on the workload because of the need to give feedback continuously and marking continuously is a bit of a problem and that’s how the workload increases with assessment.

… it’s just ongoing, the workload is just ridiculous … it’s usually big project type things, portfolios, assignments, which require a lot of time for marking.

… does take a lot of time away from our own research because we having to set second papers for every single assessment and having to mark and moderate them …

As shown in , the other reasons for using CA (Q12 of the questionnaire) were significantly different (p < 0.05).

illustrates that academics acknowledged that CA practices entailed both formative and summative assessments (Q13 of the questionnaire), and that feedback is integral to these methods in order to enable students to move progressively with their learning. It is of concern, however, that a fair percentage of academics did not use formative assessment to indicate students’ progress (38%; p < 0.05), nor did they provide written feedback to students on their assessment (36%; p < 0.05).

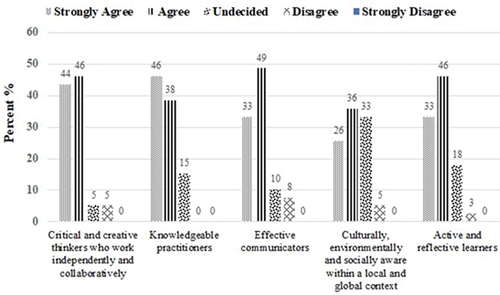

From , academics were of the opinion that assessments encouraged students to achieve four of the five graduate attributes (Q14 of the questionnaire), which were statistically significantly different (p < 0.05). Assessments, however, did not encourage students to become “knowledgeable practitioners” (p = 0.05).

With reference to Q18 of the questionnaire, 25% of the academics were of the opinion that there should be a re-assessment for every assessment (p = 0.003), while 66.7% believed that re-assessment should only be at the end of a module (p = 0.046). A high percentage of academics (81.6%) also confirmed that the re-assessment mark should be capped at a maximum of 50% (p < 0.001). Academic accounts from the interviews further revealed their ambivalent understandings on the number of assessments to be conducted and the reasons for re-assessment.

At Faculty level we were told that each assessment is allowed a second assessment, but then it was also questioned, are we not over-assessing? So we’re a bit in the dark.

… if there’s four assessments how many assessments should be given a re-assessment? Should they all be given a re-assessment? You know so there isn’t that clear-cut understanding of what this actually means, I think institutionally and departmentally

… we deliver two tests and allow for re-assessment of, of those tests, the re-testing of those tests. So if students don’t achieve they allowed to get re-assessed. In the middle of those you allowed to have, or should have, smaller assessments just to keep the students, umm on, sort of aware that there is testing happening and there mustn’t be just one exam test at the end of the year”.

The aforementioned highlights the lack of appropriate and clear institutional guidelines and engagement of assessment-specific concepts, principles and terminology. This became increasingly evident from the interviews as academics claimed that:

The only guidelines that we have for continuous assessment is together with the examinations, the policy, and that is very vague in terms of how people should actually undertake continuous assessment. So I know there is something out there, but I do know that everybody is practicing continuous assessment differently within departments, within faculties, and within other faculties and Health Sciences.

The University must also have a, a position paper or come to some consensus on what this thing is about, called continuous assessment because I think if I remember the most recent version of the assessment policy it attempts to unpack continuous assessment, but it doesn’t really. So we all kind of … have worked in the dark. Some of us that have been here for a long time we get better at it, probably, working in the dark still, but we get better at it, but I think that the University needs to come on board in terms of the two streams of the way assessments operate, and certainly align it, so that students are treated fairly in both systems.

The institution doesn’t support it in that they place very little emphasis on continuous assessment. It is kind of side-lined as opposed to the proper examination procedure … not giving us the same amount of time that they allow for the examination process.

The issue of logistics is further indicative of the lack of clear institutional guidelines, especially the allocation of venues for CA as “preference is always given to those that are in the examination system” and “the institution doesn’t recognize the importance of continuous assessment”. Regardless of academics’ acknowledging that the “most recent version of the assessment policy attempts to unpack continuous assessment” and examination modes of assessment, they appealed that “University needs to come on board in terms of the two streams of the way assessments operate, and certainly align it, so that students are treated fairly in both systems”.

Discussion

Contributing to the findings of prior research (Hernández, Citation2012; Muskin, Citation2017; Popham, Citation2009; Simper, Citation2020; Walker et al., Citation2019), the results of this study highlight the need for ongoing robust debate aimed at strengthening the quality assurance of CA practices through engaged curriculum transformation and educational reform. Notably, a fair percentage of academics within the FoHS do not use CA, and if they did they found it unsuitable for their programmes. Consistent with a study conducted in Trinidad and Tobago (De Lisle, Citation2016), it can be gathered that academics’ perceptions of CA as being unsuitable can be attributed to them focusing more on the summative function of CA practice and less on their role and formative aspects of the assessment process. This suggests that academics need to become more assessment literate, which Popham (Citation2009) described as understanding the fundamental assessment concepts and procedures, and to engage in the ongoing process of adjusting instructional strategies to enrich students learning experiences. The lack of robust institutional guideline and engagement of assessment-specific concepts, principles and terminology further exacerbates this.

Another critical point to note is that the diverse CA assessment and re-assessment practices used by academics in the FoHS indicate that assessment tasks are not in constructive alignment with the assessment criteria. This resonates with Simper’s (Citation2020) research, particularly her advice that higher education institutions need to provide academics with professional development in order for them to understand assessment thresholds of constructive alignment and differentiation of standards as part of promoting quality assessment practices. Moreover, and as conveyed by the participating academics in this study, the diverse CA assessment and re-assessment practices lead to higher workloads emanating from administrative processes. Pauli and Ferrell (Citation2020, p. 17), amongst other authors, have characterised this as “assessment bunching” where several high stakes assessment deadlines are on the same date. Inevitably, this affects students’ progression, retention and success rates as there are limited opportunities for sharing and reflecting on feedback. Advocates of CA have therefore advised striking a meaningful balance in designing a coherent curriculum that consists of a balance between formative and summative assessments, and a balance between feedback and feed forward to minimise increased academic workloads (De Lisle, Citation2016; Muskin, Citation2017; Simper, Citation2020). This is exemplified by the “Transforming the Experience of Students through Assessment (TESTA)” project, particularly Map My Assessment (MMA) online platform (Walker et al., Citation2019).

Walker et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that the MMA online platform enables staff to visualise a complex picture of module assessment information across modules and programmes, mainly stimulating discussion of formative and summative assessment distribution per module and programme. Importantly, MMA can eliminate assessment bunching and choke points; introduce or reduce assessment variety; reduce assessment volume; and meet marking turnaround deadlines more effectively. Such a system could only prove useful if adopted as part of quality assurance review and accreditation processes for curricula and programmes across South African Universities. It will also help to ascertain the extent to which CA is practiced in a formal and structured way or in a more spontaneous and less structured way. Inevitably such research would provide deeper insight into the frequency with which grades are used to assess students’ work, and the frequency and mechanisms through which prompt feedback is given to students.

In addition, and in support of Pauli and Ferrell’s (Citation2020) argument, if done properly assessment can also drive improvement, shape student behaviour and provide accountability to employers and others. In fact, the unprecedented COVID-19 (coronavirus disease of 2019–2020) global outbreak, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has shown that the appropriate automation of some aspect of assessments such as marking can help facilitate students to experience meaningful learning, especially by supporting assessment for learning and not simply of learning. Given the logistical challenges at DUT, more data about CA and its design needs to be collected from both staff and students in order to provide more useful analytics. Arguably, there are significant risks in not having the underlying infrastructure to support technological innovation; herein lies a rich area for further research.

Although the academics who participated in this study may believe in the notion of graduate attributes they reported that CA did not encourage students to become “knowledgeable practitioners”. Continuous assessment practices are required that enable students to acquire disciplinary knowledge (Mode 1), while preparing them to apply (reflexive) the skills (practical) in specific areas of the job markets (Mode 2), as suggested by Yorke (Citation2009) and Beets (Citation2009). It can be further argued that academics’ personal beliefs on teaching and learning and the needs of their academic discipline could have influenced the results in . In addressing the limitation of this small scale study situated in one institutional setting and faculty, additional research is needed to examine academics’ personal and contextual factors which enable and/or constrain CA practices, particularly the alignment of their beliefs with practice.

Limitations and conclusions

There were certain limitations to the current study. First, reliability and factor analysis are done on large samples (>300) however, due to the limited number of academics in the FoHS the exercise was performed merely as a test of rigour. Notwithstanding this, the present study represents a static measure of the participants’ perceptions and beliefs at the time they completed the survey. Future research studies need to involve academics from other faculties within DUT in order to capture a larger proportion and more representative sample of the population. Second, the questionnaire is a new construct and requires several revisions towards developing a universally accepted version. This has affected the internal and external validity of the questionnaire. The results of this study therefore cannot be generalised to a broader audience until confirmatory factor analysis is conducted in future studies to support the measures of dimensionality or construct validity.

The main findings of this study showed that the factors constraining the understanding and practice of continuous assessment stemmed from inadequate institutional support and resources, limited understanding of the reciprocal process of formative assessment between academics and students, and the increased academic workload caused by assessment bunching from using varied CA assessment and re-assessment practices. The aforementioned has severe implications for policy reform, particularly in strengthening quality assurance of CA practices in order to increase the validity and reliability of assessments that are fit for purpose. Concomitantly, academics should continuously develop their assessment literacy knowledge, skills, principles and practices, which is a condition for students to have more meaningful learning experiences.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Mr. Deepak Singh (DUT) for his expert statistical guidance and Dr Gillian Cruickshank (Queens University Belfast) for adeptly proof reading the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anisa Vahed

Anisa Vahed is a NRF “Y-Rated” researcher and senior lecturer/dental technologist in the Department of Dental Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences at the Durban University of Technology. Her research interests include undergraduate research-teaching nexus and online pedagogical practices. She has delivered numerous papers, workshops and seminars at national and international settings. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0164-91144

Matthys Michielse Walters

Matthys Michielse Walters is a retired academic who was a former head of department and senior lecturer in the Department of Basic Medical Sciences at the Durban University of Technology. He has 32 years of teaching experience, specialising in human physiology. His current research interest is the implementation of Continuous Assessment practices.

Ashley Hilton Adrian Ross

Ashley Hilton Adrian Ross is an Associate Professor of homoeopathy and the former Executive Dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Durban University of Technology. He has 25 years’ experience in academic teaching, clinical- and research supervision, and nearly 20 years’ experience in academic management. His research interests include homoeopathic pathogenetic trials, indigenous knowledge systems, medical philosophy and pedagogy of research. He has delivered numerous papers, workshops and seminars in national and international settings.

References

- Abera, G., Kedir, M., & Beyabeyin, M. (2017). The implementations and challenges of continuous assessment in public universities of Eastern Ethiopia. International Journal of Instruction, 10(4), 109–128.

- Al-Kadri, H. M., Al-moamary, M. S., Roberts, C., & Van der vleuten, C. P. M. (2012). Exploring assessment factors contributing to students’ study strategies: Literature review. Medical Teacher, 34(sup1), S42–S50.

- Amador, F., Martinho, A. P., Bacelar-Nicolau, P., Caeiro, S., & Oliveira, C. P. (2015). Education for sustainable development in higher education: Evaluating coherence between theory and praxis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(6), 867–882.

- Ashwin, P. (2009). Analysing teaching-learning in higher education: Accounting for structure and agency. London: Continuum.

- Basson, R. (2007). A comparision of policies and practices in assessment in a further education institution, University of Stellenbosch]. http://hdl.handle.net/10019.1/1884

- Beets, P. (2009). Towards integrated assessment in South African higher education. In E. Bitzer (Ed.), Higher education in South Africa (pp. 183–202). Stellenbosch: Sun Press.

- Bjælde, O., Jørgensen, T., & Lindberg, A. (2017). Continuous assessment in higher education in Denmark. Dansk Universitetspædagogisk Tidsskrift, 12(23), 23.

- Cookson, C. J. (2018). Assessment terms half a century in the making and unmaking: From conceptual ingenuity to definitional anarchy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(6), 930–942.

- Corbin, J., & Holt, N. L. (2011). Grounded theory. In B. Somekh, and C. Lewin (Eds.), Theory and methods in social research (2nd ed., pp. 113–120). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Council on Higher Education. (2009). Higher education monitor: The state of higher education in South Africa. South Africa: C. o. H. Education.

- Council on Higher Education. (2010). Teaching and learning beyond formal access: Assessment through the looking glass. (Vol. HE Monitor No. 10) Pretoria: CHE Press.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). California: Sage.

- De Lisle, J. (2015). The promise and reality of formative assessment practice in a continuous assessment scheme: The case of Trinidad And Tobago. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(1), 79–103.

- De Lisle, J. (2016). Unravelling continuous assessment practice: Policy implications for teachers’ work and professional learning. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 50, 33–45.

- Donald, J. G. (2009). The commons: Disciplinary and interdisciplinary encounters. In C. Kreber (Ed.), The university and its disciplines: Teaching and learning within and beyond disciplinary boundaries (pp. 35–49). New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

- Downs, C. T. (2006). What should make up a final mark for a course? An investigation into the academic performance of first year bioscience students. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(3), 345–364.

- Dunn, K. E., & Mulvenon, S. W. (2009). A critical review of research on formative assessments: The limited scientific evidence of the impact of formative assessments in education. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 14(14), 1–11.

- Durban University of Technology. (2019). Assessment policy (policy document). Durban: Durban Univerisity of Technology.

- Durban University of Technology. (2020). DUT draft strategic plan 2020-2030 www.dut.ac.za

- Faculty of Health Sciences. (2014a). Minutes of the curriculum renewal meeting 16 April 2014. Durban: Durban University of Technology.

- Faculty of Health Sciences. (2014b). Minutes of the curriculum renewal meeting 19 March 2014. Durban: Durban University of Technology.

- Garraway, J., Vahed, A., Sunder, R., Reddy, P., Maharaj, M., Walters, M., & Seedat, N. (2019). Time travel through the polytechnic* to University Nexus: From heartfelt difficulties to new possibilities. Alternation, 28(4). http://alternation.ukzn.ac.za/Files/articles/special-editions/28/06-Garraway-F.pdf

- González, C. (2011). Extending research on ‘conceptions of teaching’: Commonalities and differences in recent investigations. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(1), 65–80.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis 7th . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Harlen, W., & Deakin, C . (2002 A systemic review of the impact of summative assessment and tests on students' motivation for learning.). Research Evidence in Education Library (London: Institute of Education).

- Harris, A. (2017). Editorial: Fit for purpose: Lessons in assessment and learning. English in Education, 51(1), 5–11.

- Hernández, R. (2012). Does continuous assessment in higher education support student learning? Higher Education, 64(4), 489–502.

- Kreber, C. (Ed.). (2009). The university and its disciplines: Teaching and learning within and beyond disciplinary boundaries. New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

- Lindblom-Ylanne, S., Trigwell, K., Nevgi, A., & Ashwin, P. (2006). How approaches to teaching are affected by discipline and teaching context. Studies in Higher Education, 31(3), 285–298.

- Muskin, J. (2017). Continuous assessment for improved teaching and learning: A critical review to inform policy and practice Programme and Meeting Document. http://repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/handle/MINEDU/5525

- Newton, P. E. (2007). Clarifying the purposes of educational assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 14(2), 149–170.

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Strivingto meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917733847.

- Pauli, M., & Ferrell, G. (2020). The future of assessment: Five principles, five targets for 2025 https://www.jisc.ac.uk/reports/the-future-of-assessment

- Popham, W. J. (2009). Assessment literacy for teachers: Faddish or fundamental? Theory Into Practice, 48(1), 4–11.

- Punch, K. F. (2014). Introduction to social research - Quantiative and qualitative approaches (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

- Reimann, N., & Sadler, I. (2017). Personal understanding of assessment and the link to assessment practice: The perspectives of higher education staff. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(5), 724–736.

- Richardson, J. T. E. (2015). Coursework versus examinations in end-of-module assessment: A literature review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(3), 439–455.

- Simonite, V. (2003). The impact of coursework on degree classifications and the performance of individual students. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(5), 459–470.

- Simper, N. (2020). Assessment thresholds for academic staff: Constructive alignment and differentiation of standards. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–15. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1718600

- South African Qualifications Authority. (2005). Guidelines for integrated assessment. SAQA. https://www.saqa.org.za/sites/default/files/2019-11/intassessment_0.pdf

- Statistics South Africa. (2011). Mid-year population release (Pretoria: Stats SA).

- Tarekegne, W. M. (2019). Higher education instructors perceptions and practice of active learning and continuous assessment techniques: The case of Jimma University. Bulgarian Journal of Science and Education, 13(1), 50–70.

- Trigwell, K., & Ashwin, P. (2006). An exploratory study of situated conceptions of learning and learning environments. Higher Education, 51(2), 243–258.

- Turner, J., & Briggs, G. (2018). To see or not to see? Comparing the effectiveness of examinations and end of module assessments in online distance learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(7), 1048–1060.

- University of Johannesburg. (n.d.). Guidelines for continuous assessment. Johannesburg: Author.

- Vahed, A., McKenna, S., & Singh, S. (2016). Linking the ‘know-that’ and ‘know-how’ knowledge through games: A quest to evolve the future for science and engineering education. Higher Education, 71(6), 781–790.

- Walker, S., Salines, E., Abdillahi, A., Mason, S., Jadav, A., & Molesworth, C. (2019). Identifying and resolving key institutional challenges in feedback and assessment: A case study for implementing change. Higher Education Pedagogies, 4(1), 422–434.

- Yorke, M. (2009). Assessment for career and citizenship. In C. Kreber (Ed.), The University and its Disciplines (pp. 221–230). New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis.