ABSTRACT

Background: Sexual assault and alcohol use are significant public health concerns, including for the United States (US) military. Although alcohol is a risk factor for military sexual assault (MSA), research on the extent of alcohol-involvement in MSAs has not been synthesised.

Objective: Accordingly, this scoping review is a preliminary step in evaluating the existing literature on alcohol-involved MSAs among US service members and veterans, with the goals of quantifying the prevalence of alcohol-involved MSA, examining differences in victim versus perpetrator alcohol consumption, and identifying additional knowledge gaps.

Method: In accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines for Scoping Reviews, articles in this review were written in English, published in 1996 or later, reported statistics regarding alcohol-involved MSA, and included samples of US service members or veterans who experienced MSA during military service.

Results: A total of 34 of 2436 articles identified met inclusion criteria. Studies often measured alcohol and drug use together. Rates of reported MSAs that involved the use of alcohol or alcohol/drugs ranged from 14% to 66.1% (M = 36.94%; Mdn = 37%) among servicemen and from 0% to 83% (M = 40.27%; Mdn = 41%) among servicewomen. Alcohol use was frequently reported in MSAs, and there is a dearth of information on critical event-level characteristics of alcohol-involved MSA. Additionally, studies used different definitions and measures of MSA and alcohol use, complicating comparisons across studies.

Conclusion: The lack of event-level data, and inconsistencies in definitions, measures, and sexual assault timeframes across articles demonstrates that future research and data collection efforts require more event-level detail and consistent methodology to better understand the intersection of alcohol and MSA, which will ultimately inform MSA prevention and intervention efforts.

HIGHLIGHTS

A total of 34 of 2436 articles identified met inclusion criteria. Studies often measured alcohol and drug use together. Rates of reported military sexual assaults that involved the use of alcohol or alcohol/drugs ranged from 14% to 66.1% (M = 36.94%; Mdn = 37%) among servicemen and from 0% to 83% (M = 40.27%; Mdn = 41%) among servicewomen.

More precise prevalence estimates of the intersection between alcohol and military sexual assault were limited due to inconsistencies in the definitions of sexual assault and alcohol use, measures of sexual assault and alcohol use, and timeframe for reporting across studies.

Future research should standardise the measures, definitions, and timeframes of sexual assault and alcohol-involvement to allow for a more precise estimation of alcohol-involved military sexual assault. Furthermore, event-level data is needed including amount and timeframe of alcohol consumption, relationship between victim and perpetrator, location of alcohol consumption and military sexual assault, and whether the assault was opportunistic or facilitated, to inform military sexual assault prevention and intervention efforts in the military.

Antecedentes: La agresión sexual y el consumo de alcohol son importantes preocupaciones de salud pública, incluso para el ejército de los Estados Unidos (EE. UU.). Aunque el alcohol es un factor de riesgo de agresión sexual militar (MSA, por sus siglas en inglés), no se han sintetizado investigaciones sobre el alcance de la participación del alcohol en las MSA.

Objetivo: En consecuencia, esta revisión de alcance es un paso preliminar en la evaluación de la literatura existente sobre MSA relacionadas con el alcohol entre miembros del servicio militar y veteranos de los EE. UU., con el objetivo de cuantificar la prevalencia de MSA relacionadas con el alcohol, examinando las diferencias en el consumo de alcohol entre víctimas y perpetradores e identificar lagunas de conocimiento adicionales.

Método: De acuerdo con los Elementos de Informes Preferidos para Revisiones Sistemáticas y las pautas de metaanálisis para revisiones de alcance, los artículos de esta revisión se escribieron en inglés, se publicaron en 1996 o después, informaron estadísticas sobre MSA relacionada con el alcohol e incluyeron muestras de miembros del servicio militar estadounidense o veteranos que experimentaron MSA durante el servicio militar.

Resultados: Un total de 34 de 2.436 artículos identificados cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión. Los estudios a menudo midieron el consumo de alcohol y drogas juntos. Las tasas de MSA reportadas que involucraron el uso de alcohol o alcohol/drogas oscilaron entre 14% y 66,1% (M = 36,94%; Mdn = 37%) entre los militares y entre 0% y 83% (M = 40,27%; Mdn = 41). %) entre las mujeres militares. El consumo de alcohol se informó con frecuencia en las MSA y hay escasez de información sobre las características críticas a nivel de eventos de las MSA involucradas con el alcohol. Además, los estudios utilizaron diferentes definiciones y medidas de MSA y consumo de alcohol, lo que complica las comparaciones entre los estudios.

Conclusión: La falta de datos a nivel de evento y las inconsistencias en las definiciones, medidas y plazos de agresión sexual en todos los estudios demuestran que los esfuerzos futuros de investigación y recopilación de datos requieren más detalles a nivel de evento y una metodología más consistente para comprender mejor la intersección del alcohol y la MSA, que en última instancia informará los esfuerzos de prevención e intervención de MSA.

背景:性侵犯和酗酒是重大的公共卫生问题,包括美国军方。尽管酒精是军事性侵犯 (MSA) 的一个风险因素,但有关 MSA 中酒精参与程度的研究尚未综合。

目的:因此,本次范围综述是评估有关美国现役军人和退伍军人中与酒精有关的 MSA 的现有文献的初步步骤,旨在量化与酒精有关的 MSA 的流行率,考查受害者与肇事者饮酒量的差异, 并确定其他知识差距。

方法:根据范围界定综述的系统综述首选报告项目和元分析指南,本综述中的文章以英文撰写,发表于 1996 年或以后,报告了有关酒精相关 MSA 的统计数据,并包括美国军人样本或在服兵役期间经历过 MSA 的退伍军人。

结果:2,436 篇文章中共有 34篇符合纳入标准。研究经常同时测量酒精和药物的使用情况。据报道,军人中涉及使用酒精或酒精/药物的 MSA 比例为 14%–66.1%(M = 36.94%;Mdn = 37%),0%–83%(M = 40.27%;Mdn = 41) %)在女军人中。MSA 中经常报告饮酒情况,但缺乏有关酒精相关 MSA 的关键事件级特征的信息。此外,研究使用了不同的 MSA 和酒精使用定义和测量方法,使研究之间的比较变得复杂。

结论:事件级数据的缺乏,以及各文章中定义、测量和性侵犯时间范围的不一致表明,未来的研究和数据收集工作需要更多的事件级细节和更一致的方法,以更好地了解酒精和 MSA 的交叉点 ,这最终将为 MSA 预防和干预工作提供信息。

Rates of military sexual assault (MSA) are concerning (Bell et al., Citation2018), with 2.5% of active duty service members (SMs) experiencing unwanted sexual contact within the past year (9.1% women; 1.2% men) (Meadows et al., Citation2021), For the context of this article, MSA is defined as a sexual assault experienced by a SM during their time of military service. MSA has been associated with mental health concerns including suicidal ideation, alcohol and drug use, and posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms (Newins et al., Citation2021), as well as physical health problems such as headaches, indigestion, and back pain (Pegram & Abbey, Citation2019). SMs who experience MSA are also twice as likely to separate from military service within 28 months of their assault compared to those who were not assaulted (Morral et al., Citation2021). Early attrition is costly to the military in personnel investments and may affect compensation for symptoms resulting from MSA (Morral et al., Citation2021). Considering the significant impact of MSA on the physical and mental health of SMs, veterans, and military readiness, research is warranted to better understand the scope of MSA among this population.

Alcohol use is also problematic among the United States (US) military population (Jacobson et al., Citation2020; Schumm & Chard, Citation2012), and shown to be a risk factor for sexual assault perpetration (Davis et al., Citation2021). Alcohol consumption can increase the likelihood of aggression among both men (Davis et al., Citation2021) and women (Crane, Citation2017), and may lead individuals to misinterpret signs of sexual interest (Parkhill & Abbey, Citation2008). The disinhibiting effects of substance use increase proclivity for sexual aggression by raising the likelihood that an individual disregards a partner's refusal of sexual activity (Abbey et al., Citation2004). One study demonstrated that among men with a history of sexual perpetration, high levels of alcohol consumption were related to increases in sexual arousal, which in turn, elevated use of coercive tactics and intentions for nonconsensual sex (Davis et al., Citation2021). Because rates of MSA are concerning, we urgently need to develop and implement MSA prevention strategies that can have the largest impact to protect our armed forces. A broader understanding of the intersection of alcohol and MSA perpetration is needed to inform the best strategy for alcohol-related MSA prevention.

Alcohol consumption can also serve as a risk factor for sexual assault victimisation. It is imperative to note that the fault of sexual assault lies with the perpetrator, regardless of alcohol consumption. Alcohol use has shown to decrease perception of sexual assault risk cues among women (Davis et al., Citation2009) and increase cognitive and behavioural impairment among men (Monks et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, alcohol consumption among both men and women can increase the likelihood of sexual risk taking (George et al., Citation2009), and intoxication can make it difficult to resist an attacker (McCauley & Calhoun, Citation2008). Notably, individuals who experience sexual victimisation are likely to use alcohol to reduce resulting distress (Ullman & Najdowski, Citation2009), increasing the risk for subsequent revictimization (Messman-Moore et al., Citation2009). Understanding the scope of the intersection between alcohol use and sexual victimisation among SMs is also needed to inform how MSA prevention and interventions can be most effectively designed.

The 2018 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members (WGRA) revealed that the consumption of alcohol was involved in MSAs among 62% and 49% of female and male victims, respectively (Office of People Analytics, Citation2019). Although alcohol consumption is problematic among military populations and alcohol intersects with the occurrence of MSA, no research to date has synthesised the extent of this association. While there are published review articles on alcohol-involved MSA (Forkus et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Greathouse et al., Citation2015; Suris & Lind, Citation2008), most examined alcohol use as a consequence of MSA rather than an event-level characteristic. A review conducted by Greathouse and colleagues examined substance use as an event-level characteristic in sexual assault perpetration, but the sample was a broad population of adults, and was not exclusively military (Greathouse et al., Citation2015). To determine the most effective approach to preventing MSA and developing evidence-based solutions, a greater understanding of how alcohol use intersects with MSA is needed (Independent Review Commission on Sexual Assault in the Military, Citation2021; Jones et al., Citation2014), and is the aim of this scoping review.

Systematic reviews answer specific questions from a comparatively narrow scope of studies, whereas scoping reviews outline key concepts of a complex research area or one that has yet to be comprehensively reviewed. Scoping reviews often serve as a precursor to systematic reviews by summarising existing literature in a research area, identifying gaps, and examining whether sufficient data exist to conduct a systematic review (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Because the intersection of alcohol use and MSA has not yet been comprehensively synthesised, a scoping review was conducted to broadly examine the state of existing literature in this area, identify gaps, and establish next steps. The aims of the current study were to examine prevalence estimates of alcohol-involved MSAs that occurred during military service, evaluate differences in alcohol consumption by perpetrator versus victim, examine how the literature thus far has operationalised variables and measured outcomes, and pose implications for future military research, policies, and prevention efforts ().

Table 1. Articles reporting on alcohol or alcohol/drugs and military sexual assault.

1. Method

This scoping review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR), and Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage framework (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005), which involves: (1) identification of the research question; (2) identification of relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) data charting; and (5) collating, summarising, and reporting results.

1.1. Identification of the research question

This scoping review aimed to determine the range of prevalence estimates of alcohol-involved MSAs, and what details exist about victim and perpetrator alcohol consumption at the time of the MSA.

1.1.1. Inclusion criteria

Articles were included if: (1) participants were US active duty or reserve SMs from any branch or veterans; (2) sexual assault occurred during military service; (3) data on alcohol use by the victim, perpetrator, and/or both were provided; (4) prevalence estimates of alcohol-involved MSAs were provided; and (5) the publication date was 1996 or later, since assessment of MSA and sexual harassment was mandated by Public Law 104–201 in 1996 (Morral et al., Citation2015d).

1.2. Identification of relevant studies

Key Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) search terms were created by a team of experts in the areas of interpersonal violence and alcohol misuse. A librarian with expertise in military research and scoping reviews assisted in refining the search using MeSH and Boolean operators to ensure identification of all relevant literature. Keywords used for the search are displayed in Appendix A.

Databases relevant to psychological health and violence were searched, including Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PubMed, PsycINFO, Defense Technical Information Center, PTSDpubs, RAND, Violence & Abuse Abstracts, and Web of Science. The primary search was conducted on 1 July 2021, and an updated search was conducted 1 May 2023, prior to submission. Additionally, military-relevant journals not referenced within these electronic databases were hand searched, including Military Medicine, Military Behavioral Health, Military Psychology, BMJ Military Health, and Armed Forces & Society.

1.3. Study selection

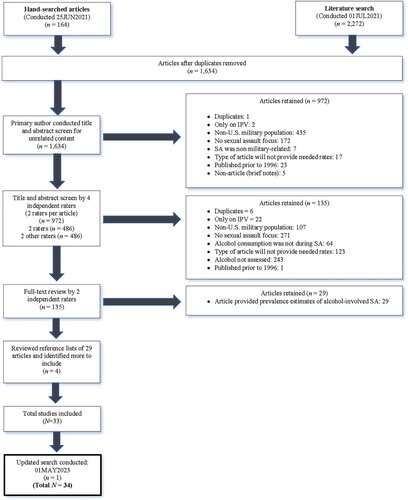

Using the selected search terms (see Supplementary Appendix A), 2272 articles were identified, and 164 articles were located via hand search for a total of 2436 articles. After de-duplication, 1634 articles remained. The lead rater reviewed titles and abstracts to eliminate unrelated articles. provides a full description of the included and excluded articles at each stage. Following the initial title and abstract screening, 972 articles remained. The next round reviewed title and abstract only and was conducted by four independent researchers (two reviewers per article). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to determine each article's eligibility for full-text review. Each pair of reviewers compared ratings. Discrepancies were analysed by the lead rater who re-reviewed titles and abstracts with discrepant ratings to determine eligibility for full-text review. After title and abstract review, 135 articles were selected for full-text review. Two independent raters reviewed the full text of all 135 articles to ensure that prevalence estimates of alcohol-involved MSA were provided. Articles without prevalence estimates were eliminated. The two reviewers compared ratings and addressed inconsistencies via discussion and re-assessment. Twenty-nine articles provided the prevalence estimates of alcohol-involved MSAs and were retained. Reference lists of the 29 articles were manually reviewed to ensure all relevant publications were considered. All years of Department of Defense (DoD) surveys were reviewed, (1996–2023), and an additional five articles were added for a total of 34 articles.

1.4. Data charting

A form containing the following categories was created (see Supplementary Appendix D): author/organization, military branch, rates of sexual victimisation, alcohol use by both parties, alcohol use by perpetrator, alcohol use by victim, constructs measured, questions used, and definitions applied. The lead rater and one other researcher charted each of the 34 articles using these categories. After charting was complete, the raters compared data, discussed discrepancies, and re-read articles to reconcile inconsistencies.

2. Results

2.1. Population

The population of interest varied across articles. Some articles (n = 6; 18%) sampled only one military branch (Davis et al., Citation2019; Inspector General of the Department of Defense, Citation2004; Miller et al., Citation2018; Morral et al., Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Thomas & Le, Citation1996), while others sampled only reservists (n = 5; 15%) (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2013, Citation2016; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009) or active duty (n = 9; 26%) (Davis et al., Citation2017; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Morral et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015d; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019; Rock, Citation2013; Rock et al., Citation2011; Thomas & Le, Citation1996). Among Workplace and Gender Relations surveys, only one study reported data for the Coast Guard (Office of People Analytics, Citation2019), while the others did not include Coast Guard SMs. Other articles (n = 11; 32%) focused only on military service academy students (Cook et al., Citation2005, Citation2015; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008, Citation2010; Davis et al., Citation2019, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2012; Klahr & Davis, Citation2019; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017; Wright, Citation2013). Cunningham examined only male-on-male penetrative MSAs (Cunningham, Citation2021), while articles by Sadler and colleagues (n = 3; 9%) sampled female veterans (Sadler, Citation1996; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003). Most articles included both military and civilian perpetrators and victims, with estimates of 81% of reserve SMs and 85% of active duty SMs reporting that their MSA offender was a SM (Morral et al., Citation2015a).

2.2. Prevalence of MSA

Of the 34 articles included, 28 (82%) provided rates of MSA (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Cook et al., Citation2005, Citation2015; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008, Citation2010; Davis et al., Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2016; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Morral et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019; Rock, Citation2013; Rock et al., Citation2011; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009; Sadler, Citation1996; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003; Thomas & Le, Citation1996; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017) 23 of which specified past-year MSA rates by sex (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Cook et al., Citation2015; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008, Citation2010; Davis et al., Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2016; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Morral et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019; Rock, Citation2013; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009; Rock et al., Citation2011; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017). These 23 articles were selected to estimate past-year MSA prevalence. The timeframe of MSA occurrence varied across articles. Past year was the most consistent timeframe reported and was selected as the timeframe for this scoping review. Rates of past-year MSA ranged from 0.22%–4.6% (M = 1.56%; Mdn = 1.3%) for men and 1.71%–23.1% (M = 8.34%; Mdn = 6.5%) for women. Considering the population differences across articles, rates of past-year MSA were also calculated by population (see ). The variety of MSA measures used across articles complicated summarising prevalence estimates. Therefore, rates of past-year MSA were also calculated by each of the two main MSA measures used across studies; the unwanted sexual contact (USC) measures (1-, 2-, and 5-items) and the RAND measure (see ).

Table 2. Past-year military sexual assaults (MSAs) and MSAs involving alcohol or alcohol/drug use, by population, sexual assault (SA) measure, and definition of substance.

2.3. Prevalence of alcohol- or alcohol/drug-involved MSA

Although this review focused on alcohol involvement in MSA, nine articles (26%) did not measure alcohol separately from drug use (Cook et al., Citation2005, Citation2015; Cunningham, Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2018; Morral et al., Citation2015d; Sadler, Citation1996; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003; Thomas & Le, Citation1996). Therefore, the term ‘alcohol or alcohol/drugs’ is used throughout the remainder of this work to ensure the accurate description of the construct measured. A more detailed explanation of the measures and definitions of alcohol or alcohol/drug use across articles can be found in the Measurement and definitions of variables section. Twenty-nine articles (85%) provided rates of alcohol- or alcohol/drug-involved MSAs by sex (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Cook et al., Citation2005, Citation2015; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008, Citation2010; Cunningham, Citation2021; Davis et al., Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008; Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2016; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Klahr & Davis, Citation2019; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Morral et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019; Rock, Citation2013; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009; Rock et al., Citation2011; Sadler, Citation1996; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017). Rates of MSAs that involved alcohol or alcohol/drugs ranged from 14% to 66.1% (M = 36.94%; Mdn = 37%) for men and 0%–80% (M = 40.27%; Mdn = 41%) for women. When rates of MSA cases involving alcohol or alcohol/drugs were examined over time, upward trends were found for both men and women (see Supplementary Appendix B). Because articles varied by population, rates of alcohol- or alcohol/drug-involved MSAs were calculated for men and women based on population (see ). Although variability in methodology precluded statistical comparisons, there were general patterns that emerged in the data. Rates of alcohol- or alcohol/drug-involved MSA were notably high for male service academy students (14%–65%; M = 41.55%; Mdn = 42.5%), compared to that of male active duty (19%–49%; M = 28.22%; Mdn = 25.48%) or male reserve SMs (17%–27%; M = 22.25%; Mdn = 22.5%). For women, there was not an apparent trend for female service academy students (0%–83%; M = 40.37%; Mdn = 41.5%), female active duty (12%–63.35%; M = 42.96%; Mdn = 48%), and for female reserve SMs (7%–60%; M = 37.07%; Mdn = 38.5%). Considering differences across articles in the measurement and definitions of alcohol or alcohol/drug involvement, rates were also calculated based on substance type (see ).

2.4. Alcohol or alcohol/drug consumption by MSA case, perpetrator, and victim

The next aim was to examine differences in alcohol consumption between victims and perpetrators. Among the included studies, alcohol or alcohol/drug involvement of MSAs was categorised in three ways: (1) the overall case involved, (2) the perpetrator was reported to have used, and (3) the victim was reported to have used alcohol or alcohol/drugs (see ).

Table 3. Ranges of prevalence estimates of cases that involved, or perpetrators or victims who used, alcohol or alcohol/drugs, as reported by men, women, and unknown respondents (N = 34 articles).

Across all articles, 25 (74%) reported whether the overall case involved the use of alcohol or alcohol/drugs (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008, Citation2010; Cook et al., Citation2005, Citation2015; Davis et al., Citation2017, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2016; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Inspector General of the Department of Defense, Citation2004, Citation2013; Klahr & Davis, Citation2019; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Morral et al., Citation2015b, Citation2015c; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019; Rock, Citation2013; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009; Rock et al., Citation2011; Thomas & Le, Citation1996; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017; Wright, Citation2013), 28 articles (82%) indicated whether the perpetrator reportedly used (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008, Citation2010; Cook et al., Citation2005; Cunningham, Citation2021; Davis et al., Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2016; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Inspector General of the Department of Defense Citation2013; Klahr & Davis, Citation2019; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Miller et al., Citation2018; Morral et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009; Sadler, Citation1996; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003; Thomas & Le, Citation1996; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017), and 26 articles (76%) indicated whether the victim reportedly used alcohol or alcohol/drugs (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008, Citation2010; Cook et al., Citation2005; Cunningham, Citation2021; Davis et al., Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2016; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Inspector General of the Department of Defense Citation2013; Klahr & Davis, Citation2019; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Miller et al., Citation2018; Morral et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017). Seven articles (21%) provided rates for one of these categories (case, perpetrator, victim) (Cook et al., Citation2015; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2013; Inspector General of the Department of Defense, Citation2004; Rock, Citation2013; Rock et al., Citation2011; Sadler, Citation1996; Wright, Citation2013), 10 articles (29%) reported rates for two categories (Cunningham, Citation2021; Davis et al., Citation2019; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008; Miller et al., Citation2018; Morral et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003; Thomas & Le, Citation1996), and 17 articles (50%) indicated rates for all categories (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008, Citation2010; Cook et al., Citation2005; Davis et al., Citation2017, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2012, Citation2016; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Inspector General of the Department of Defense Citation2013; Klahr & Davis, Citation2019; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Morral et al., Citation2015b; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009, Van Winkle et al., Citation2017).

shows rates of alcohol or alcohol/drug consumption by the overall case, by the perpetrator, and by the victim. Overall, women and men reported similar average rates of whether the victim was under the influence of alcohol or alcohol/drugs at the time of the MSA (0%–83%; M = 32.28%; Mdn = 31% and 18%–66.1%; M = 33.61%; Mdn = 32%, respectively). Although statistical comparisons could not be made, the reported rates of alcohol or alcohol/drug use in MSA cases tended to be higher among women than men (21%–80%; M = 48.22%; Mdn = 46% for women; 14%–65%; M = 39.26%; Mdn = 39% for men).

2.5. Measurement and definitions of variables

2.5.1. Assessment of MSA

Different MSA assessments were used across articles, none of which were standardised measures (see Appendix C for survey items used to assess MSA). For example, 15 articles (44%) measured USC (Cook & Lipari, Citation2008, Citation2010; Cook et al., Citation2015; Davis et al., Citation2019, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2013; Klahr & Davis, Citation2019; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Rock, Citation2013; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009; Rock et al., Citation2011; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017), nine articles (26%) used the RAND measure (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Davis et al., Citation2017; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2016; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Morral et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019), four articles (12%) examined actual/attempted sexual assault or rape (Sadler, Citation1996; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003; Thomas & Le, Citation1996), and six articles (18%) assessed sexual assault (Cook et al., Citation2005; Cunningham, Citation2021; Inspector General of the Department of Defense, Citation2004, Citation2013; Miller et al., Citation2018, Wright, Citation2013). Among the four articles measuring actual/attempted sexual assault or rape, Thomas and Le used the Marine Corps Equal Opportunity Survey (Thomas & Le, Citation1996), and articles by Sadler and colleagues used the Military Environment Scale, which was developed for their study (Sadler, Citation1996; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003). Five articles examined cases of sexual assault reported to law enforcement and therefore did not have a consistent or standardised assessment of MSA (Cunningham, Citation2021; Inspector General of the Department of Defense, Citation2004, Citation2013; Miller et al., Citation2018; Wright, Citation2013). Furthermore, the MSA measures on the WGRA/WGRR/SAGR changed over time (see the Definitions of variables section).

2.5.2. Definitions of MSA

In addition to variability in assessments of alcohol or alcohol/drug use, definitions of MSA varied across articles. Among the studies that were not WGRA/WGRS/SAGR surveys, definitions of MSA ranged from actual/attempted rape/sexual assault (Thomas & Le, Citation1996), to attempted or completed rape (Sadler, Citation1996), uninvited sexual contact (Sadler et al., Citation1997), one or more completed or attempted rapes (Sadler et al., Citation2003), and sexual assault as reported to officers of the law (Cunningham, Citation2021; Inspector General of the Department of Defense, Citation2004, Citation2013; Miller et al., Citation2018; Wright, Citation2013). Furthermore, Miller and colleagues collapsed indecent exposure, kissing, romantic language, gestures, touching, attempted touching, penetration, and oral contact together into the term sexual assault (Miller et al., Citation2018). Sadler separated terms for MSA into the following: attempted or completed rape, sexual touching, genital fondling, and sexual harassment (Sadler, Citation1996).

Among the WGRA/WGRS/SAGR survey reports, either the DoD measure or the 2-item USC measure was used prior to 2006. The DoD measure asked:

[H]as anyone done any of the following to you without your consent and against your will? Touched, stroked, or fondled your private parts? Physically attempted to have sexual intercourse with you but was not successful? Physically attempted to have oral or anal sex with you but was not successful? Had sexual intercourse with you? Had oral sex with you? Had anal sex with you? (Cook et al., Citation2005, p. 17)

The 1-item USC measure was introduced for use in WGRA/WGRS/SAGR surveys in 2006, and asked respondents:

In the past 12 months, have you experienced any of the following sexual contacts that were against your will or occurred when you did not or could not consent where someone … Sexually touched you (e.g., intentional touching of the genitalia, breasts, or buttocks) or made you sexually touch them? Attempted to make you have sexual intercourse but was not successful? Made you have sexual intercourse? Attempted to make you perform or receive oral sex, anal sex, or penetration by a finger or object, but was not successful? Made you perform or receive oral sex, anal sex, or penetration by a finger or object? (Lipari et al., Citation2008, p. 5)

2.5.3. Measures of alcohol or alcohol/drug use

Twenty-five (74%) of the included articles assessed alcohol use specifically (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008, Citation2010; Davis et al., Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2016; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Inspector General of the Department of Defense, Citation2004, Citation2013; Klahr & Davis, Citation2019; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Morral et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2015c; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019; Rock, Citation2013; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009; Rock et al., Citation2011; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017, Wright, Citation2013), six articles (18%) assessed whether one or more parties were intoxicated (Cook et al., Citation2005; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009), and 18 articles (53%) assessed whether drugs/alcohol were involved (Cook et al., Citation2005, Citation2015; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008; Cunningham, Citation2021; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2012, Citation2016; Inspector General of the Department of Defense Citation2013; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Miller et al., Citation2018; Morral et al., Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009; Rock et al., Citation2011; Sadler, Citation1996; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003; Thomas & Le, Citation1996) Among the included articles, 23 articles (68%) reported on one category (i.e. alcohol; intoxicated; drugs/alcohol) (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Cook & Lipari, Citation2010; Cook et al., Citation2015; Cunningham, Citation2021; Davis et al., Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2013; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Inspector General of the Department of Defense, Citation2004; Klahr & Davis, Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2018; Morral et al., Citation2015a; Citation2015b, Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019; Rock, Citation2013; Sadler, Citation1996; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017; Wright, Citation2013), seven articles (21%) reported on two categories (Cook et al., Citation2005; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2016; Inspector General of the Department of Defense Citation2013; Rock et al., Citation2011, Thomas & Le, Citation1996), and four articles (12%) reported on all categories (Cook & Lipari, Citation2008; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009).

Across articles assessing alcohol use specifically, participants were asked to respond yes or no to the following statements: ‘I had been drinking alcohol’ or ‘the offender had been drinking alcohol’ (Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2012; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Morral et al., Citation2015b; Rock, Citation2013; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017), and ‘my judgment was impaired by alcohol’ (Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009). Among articles assessing alcohol and drug use concurrently, participants were asked to respond yes or no to the following statements: ‘I/offender was using drugs/alcohol’ (Cook et al., Citation2005; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Thomas & Le, Citation1996), ‘I/offender was using alcohol and/or drugs’ (Cook & Lipari, Citation2008; Cook et al., Citation2015; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2016; Inspector General of the Department of Defense Citation2013; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009; Rock et al., Citation2011), or ‘I was too intoxicated to consent’ (Cook et al., Citation2005; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009). (see Appendix C for survey items used to assess alcohol or alcohol/drug use).

2.5.4. Timeframe of the MSA

Although 25 (74%) of the 34 articles use a 1-year timeframe for when the MSA occurred (Breslin et al., Citation2020; Cook & Lipari, Citation2008, Citation2010; Cook et al., Citation2005, Citation2015; Davis et al., Citation2017, Citation2019, Citation2023; Defense Manpower Data Center, Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2016; Grifka et al., Citation2018; Lipari & Cook, Citation2006; Lipari et al., Citation2008; Morral et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2015c, Citation2015d; Office of People Analytics, Citation2019; Rock, Citation2013; Rock & Lipari, Citation2009; Rock et al., Citation2011; Thomas & Le, Citation1996; Van Winkle et al., Citation2017), nine articles (26%) use different timeframes (Cunningham, Citation2021; Inspector General of the Department of Defense, Citation2004, Citation2013; Klahr & Davis, Citation2019; Miller et al., Citation2018; Sadler, Citation1996; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003, Wright, Citation2013). The articles by Sadler and colleagues included MSAs that occurred throughout the SMs’ military career (Sadler, Citation1996; Sadler et al., Citation1997, Citation2003), while Inspector General of the Department of Defense (DoD IG) (Inspector General of the Department of Defense, Citation2013) used sexual assault cases investigated between February and September 2012, DoD IG (Inspector General of the Department of Defense, Citation2004) used investigations of sexual assault opened over the past 10 years, and Wright relied on reports made by service academy students during academic programme years 2012–2013 (Wright, Citation2013). While Morral and colleagues used a past-year timeframe to assess alcohol-involved MSAs, the same article used rates of MSA that occurred since joining the military when assessing general MSA prevalence (Morral et al., Citation2015b). Lastly, Miller and colleagues examined sexual assault cases closed in 2012–2013 (Miller et al., Citation2018), and Cunningham studied sexual assault cases that were court-martialed from 2009 to 2019 (Cunningham, Citation2021).

3. Discussion

This scoping review aimed to synthesise the available literature on the intersection of alcohol and MSA, report the range of prevalence estimates for alcohol-involved MSA, examine differences in victim versus perpetrator alcohol consumption, and identify knowledge gaps. The prevalence of past-year MSA ranged from 0.22% to 4.6% (M = 1.56%; Mdn = 1.3%) for men and 1.71% to 23.1% (M = 8.34%; Mdn = 6.5%) for women. Across the articles reporting rates separately for men and women, the estimated prevalence of MSAs that involved the use of alcohol or alcohol/drugs ranged from 14%–66.1% (M = 36.94%; Mdn = 37%) for men and 0%–83% (M = 40.27%; Mdn = 41%) for women. The 0% value reflects results from one study where female US Coast Guard Academy (USCGA) students reported that the victim was not drinking at the time of the MSA (Cook & Lipari, Citation2010). However, in the same study, 19% of female USCGA students reported that the perpetrator drank alcohol, and 31% reported that the case involved alcohol (Cook & Lipari, Citation2010). This is one example of the complexity in obtaining accurate prevalence estimates of alcohol- or alcohol/drug-involved MSA based on the existing literature. Although prevalence estimates of alcohol- or alcohol/drug-involved MSA by case (i.e. event), perpetrator, and victim were available, there were considerable inconsistencies in the populations sampled, and the definitions, measures, and timeframes used across studies. The range of these values highlights that the intersection of alcohol or alcohol/drugs and MSA is of concern for military populations and that standardising assessment measures, definitions, and timeframes of the event can help identify more precise estimates in future research.

Although statistical comparisons were not possible and beyond the scope of this review, trends appeared in the data. For example, the report of MSA cases involving the use of alcohol or alcohol/drugs was more frequently endorsed by servicewomen (21%–80%; M = 48.22%; Mdn = 46%) than servicemen (14%–65%; M = 39.26%; Mdn = 39%). These results seem to parallel research showing that reported MSA rates in general are higher for women than men(Wilson, Citation2018). Another pattern suggested that rates of alcohol or alcohol/drug-involved MSAs were elevated among male service academy students (14%–65%; M = 41.55%; Mdn = 42.5%), compared to that of male active duty (19%–49%; M = 28.22%; Mdn = 25.48%) or male reserve SMs (17%–27%; M = 22.25%; Mdn = 22.5%). For women, there was not an apparent trend. Military service academy students are typically younger than active duty or reserve SMs, with most service academy students being college-aged (Van Winkle et al., Citation2017). The rates of MSA and alcohol- or alcohol/drug-involved MSA among military academy students align with research showing that rates of heavy, hazardous, and binge drinking within the US military are highest among SMs aged 17–24 years (Meadows et al., Citation2018), and that rates of sexual assault among SMs are highest among men under the age of 25 and women under the age of 21 (Davis et al., Citation2017) and among the enlisted ranks of E1–E4 (Lipari et al., Citation2008; Morral et al., Citation2015a; Rock, Citation2013). Prevention efforts that specifically target younger military populations, including men, are needed.

Across articles, the most notable finding was the heterogeneity of measures and definitions of variables and outcomes. This finding is consistent with prior MSA research (Forkus et al., Citation2021; Kwan et al., Citation2020; Parr et al., Citation2021). However, despite the knowledge that consistent assessment of MSA is needed, the current study was the first to synthesise the existing literature to investigate the full scope of the problem. To display the data most accurately in this scoping review, prevalence estimate ranges were presented by population, MSA measure, substance, and reports of alcohol or alcohol/drug involvement in the overall case, by the perpetrator, and by the victim. However, the extent of inconsistencies demonstrates that comparison across articles is difficult, and the precision and generalizability of the prevalence estimate ranges obtained is limited. Recently, the 2021 Independent Review Commission on Sexual Assault in the Military provided recommendations to improve our understanding of MSA by requiring the WGRA and WGRR to assess past-year, lifetime, and prior-to-military sexual assault rates, as well as rates of sexual assault by race, ethnicity, sexual and gender identity (Independent Review Commission on Sexual Assault in the Military, Citation2021). Results of this scoping review add to these recommendations by providing a synthesis of the existing literature on the intersection of alcohol- or alcohol/drug-involved MSA, and revealing in detail, the extent of the methodological inconsistencies, and how they prevent us from moving forward. The current results emphasize the need for standardisation across surveys to provide a more precise estimate of the scope of the problem, which will ultimately inform how alcohol- or alcohol/drug-related MSA prevention and intervention efforts are tailored in the military.

Various gaps in the existing knowledge base regarding the intersection of alcohol or alcohol/drug use and MSA were identified through this scoping review. Critical information about event-level characteristics is missing such as the victim and perpetrator's degree of alcohol intoxication, number of drinks consumed, the timeframe of consumption, relationship between victim and perpetrator, location of alcohol consumption and MSA, and whether the MSA was opportunistic (i.e. taking advantage of the victim's voluntary intoxication) or facilitated (i.e. spiking drinks or overserving the victim). Such event-level data are important to investigate within the context of MSA to address more complex hypotheses about the role of alcohol in sexual assault (Abbey et al., Citation2001). Although the WGRA/WGRR/SAGR surveys obtain some event-level data about MSA, including when and where it occurred, and to some degree, who the individual(s) was/were, they do not collect nuanced information about event-level alcohol use. It is recommended that future assessments of MSA include detailed questions about alcohol involvement, which are needed to better understand the scope of the problem, and thereby inform optimal intervention and prevention efforts to protect SMs from alcohol-involved MSA.

Among the reviewed studies, none of the measures used to assess MSA, or alcohol or alcohol/drug involvement were standardised or had published psychometric data. Although some of the DoD sexual assault and USC items were derived from the SEQ, questions were modified, and the scoring differed from the validated SEQ scoring procedure (Morral et al., Citation2014). To resolve these limitations in future survey efforts, it is recommended that standardised and validated measures be used for data collection. For example, the revised Sexual Experiences Survey (SES) (Koss et al., Citation2007) is the most frequently used measure of sexual assault victimisation and perpetration (Anderson et al., Citation2021; McKie et al., Citation2021). The SES improves on the measures used in the reviewed studies because it is standardised, has demonstrated reliability and convergent validity (Johnson et al., Citation2017), and includes items that are behaviourally specific. For example, rather than using the term ‘sexual intercourse’, the SES describes the specific behaviours involved. Regarding alcohol use, it is recommended that future research measure alcohol separately from drugs, and from other non-specific terms such as ‘intoxication’. Collectively, it is recommended that future research and surveys include a standardised assessment tool, such as the SES, and measure alcohol use separately from drugs. Following these recommendations will allow for data to be compared across studies and accurate prevalence estimates of the intersection between alcohol use and MSA.

Limitations of this scoping review should be noted. While ranges of prevalence estimates are given for MSA and alcohol- or alcohol/drug-involved MSA in this scoping review, statistical analyses were not conducted and the differences in prevalence estimates may not be statistically significant. This was conducted as a scoping review and not a systematic review or meta-analysis. However, a scoping review is an initial and necessary step to synthesise the literature for systematic reviews and meta-analyses to follow. The wide prevalence estimate ranges should be interpreted and generalised with caution considering the methodological issues, including heterogeneity in population, assessment measures, definitions of constructs, and varying MSA timeframes. Additionally, the self-report nature of the tools used to assess alcohol or alcohol/drug use in the literature is a limitation, as memory biases may affect the reported amount of alcohol or alcohol/drugs involved in the MSA (Ekholm, Citation2004). Furthermore, the number of reported MSAs are commonly underestimates of their occurrence (Hargrave et al., Citation2022), and true MSA prevalence estimates are likely higher than those identified in this study.

This scoping review contributes to the literature in several ways. To our knowledge, this is the first review to examine the state of the literature on alcohol or alcohol/drug involvement as a risk factor in MSAs. PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews were followed in conducting this study, and inclusion criteria were broad, allowing for a full synthesis of the existing literature on this topic. Study results provide preliminary prevalence estimate ranges of alcohol- or alcohol/drug-involved MSAs and attempt to account for variability in measures and definitions, by reporting ranges by population, MSA measure, substance used, and reports of alcohol or alcohol/drug involvement by case, perpetrator, and victim. This study highlights the limitations of and gaps in the existing literature and the importance of standardising methodology and examining more event-level data in future research that will provide critical information.

The purpose of this scoping review was to synthesise the literature on the intersection of alcohol use and MSAs. Findings from this scoping review demonstrated a wide prevalence range for alcohol- or alcohol/drug-involved MSAs, and that a more precise estimate cannot be ascertained based on the existing literature due to inconsistencies in measurement, definitions, and timeframes. Additionally, there are critical gaps in the literature that limit our knowledge of event-level details. Future research is warranted to assess event-level characteristics of alcohol-involved MSA to improve our understanding of the scope of the problem. An emerging consensus is needed on how to standardise definitions, assessments, and timeframes of MSA so that future work can provide more precise estimates of the problem, which together with event-level data, can be used to inform the focus of alcohol-involved MSA prevention and intervention efforts in the military.

Disclaimer

KHW is an employee of the US Government. This work was prepared as part of my official duties. Title 17, U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the US Government. Title 17, U.S.C. §101 defines a US Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the US Government as part of that person's official duties. Report No. 22-47 was supported by the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program grant number W81XWH-20-0039 (work unit no. N2019). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the US Government. This work was completed in support of an approved Naval Health Research Center Institutional Review Board protocol number NHRC.2021.0014.

Appendices.docx

Download MS Word (138.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Aileen Chang for her valuable contribution in assisting with the literature search, and Michelle Stoia for her careful attention to detail in editing this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data used for this study were from published articles. A comprehensive list of included articles is provided as part of this manuscript. The first author can be contacted for further questions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the scoping review.

- Abbey, A., Zawacki, T., Buck, P. O., Clinton, A. M., & McAuslan, P. (2001). Alcohol and sexual assault. Alcohol Research & Health, 25(1), 43–51.

- Abbey, A., Zawacki, T., Buck, P. O., Clinton, A. M., & McAuslan, P. (2004). Sexual assault and alcohol consumption: What do we know about their relationship and what types of research are still needed? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9(3), 271–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00011-9

- Anderson, R. E., Holmes, S. C., Johnson, N. L., & Johnson, D. M. (2021). Analysis of a modification to the sexual experiences survey to assess intimate partner sexual violence. The Journal of Sex Research, 58(9), 1140–1150. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2020.1766404

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bell, M. E., Dardis, C. M., Vento, S. A., & Street, A. E. (2018). Victims of sexual harassment and sexual assault in the military: Understanding risks and promoting recovery. Military Psychology, 30(3), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/mil0000144

- *Breslin, R. A., Klahr, A., Hylton, K., Petusky, M., White, A., & Tercha, J. (2020). 2019 Workplace and gender relations survey of reserve component members: Overview report (OPA Report No. 2020-054). Office of People Analytics. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/16_Annex_2_2019_Workplace_and_Gender_Relations_Survey_of_Reserve_Component_Members_Overview_Report.pdf

- Breslin, R. A., Klahr, A., Hylton, K., White, A., Petusky, M., & Sampath, S. (2022). 2021 Workplace and gender relations survey of military members: Overview report (OPA Report No. 2022-182). Office of People Analytics. https://www.opa.mil/research-analysis/health-well-being/gender-relations/2021-workplace-and-gender-relations-survey-of-military-members-reports/2021-workplace-and-gender-relations-survey-of-military-members-overview-report/

- *Cook, P. J., Jones, A. M., Lipari, R. N., & Lancaster, A. R. (2005). Service academy 2005 sexual harassment and assault survey (DMDC Report No. 2005-01). Defense Manpower Data Center. https://www.airforcemag.com/PDF/DocumentFile/Documents/2005/Academy2005Survey122305.pdf

- *Cook, P. J., & Lipari, R. N. (2008). 2008 Service academy gender relations survey (DMDC Report No. 2008-021). Defense Manpower Data Center. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rachel-Lipari/publication/235172419_2008_Service_Academy_Gender_Relations_Survey/links/55db1e3e08aec156b9af23d9/2008-Service-Academy-Gender-Relations-Survey.pdf

- *Cook, P. J., & Lipari, R. N. (2010). 2010 Service academy gender relations survey (DMDC Report No. 2010-023). Defense Manpower Data Center. https://www.sapr.mil/public/docs/research/FINAL_SAGR_2010_Overview_Report.pdf

- *Cook, P. J., Van Winkle, E. P., Namrow, N., Hurley, M., Pflieger, J., Davis, L., Rock, L., Falk, E., & Schneider, J. (2015). 2014 Service academy gender relations survey: Overview report (DMDC Report No. 2014-016). Defense Manpower Data Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA612147.pdf

- Crane, C. A. (2017). The proximal effects of acute alcohol use on female aggression: A meta-analytic review of the experimental literature. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000244

- *Cunningham, N. (2021). Dynamics of male-on-male penetrative sexual assaults in the United States Army [Doctoral dissertation]. Walden University. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiXgbueztT-AhXsKEQIHQYZD9AQFnoECBUQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fscholarworks.waldenu.edu%2Fdissertations%2F10109%2F&usg=AOvVaw0YpCaHySUUcljemBS_dYPO

- Davis, K. C., Neilson, E. C., Kirwan, M., Eldridge, N., George, W. H., & Stappenbeck, C. A. (2021). Alcohol-involved sexual aggression: Emotion regulation as a mechanism of behavior change. Health Psychology, 40(12), 940–950. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0001048

- Davis, K. C., Stoner, S. A., Norris, J., George, W. H., & Masters, N. T. (2009). Women’s awareness of and discomfort with sexual assault cues: Effects of alcohol consumption and relationship type. Violence Against Women, 15(9), 1106–1125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801209340759

- *Davis, L., Grifka, A., Williams, K., & Coffey, M. (2017). 2016 Workplace and gender relations survey of active duty members: Overview report (OPA Report No. 2016-050). Office of People Analytics. https://www.sapr.mil/public/docs/reports/FY16_Annual/Annex_1_2016_WGRA_Report.pdf

- *Davis, L., Klahr, A., Hylton, K., Klauberg, W., & Petusky, M. (2019). 2018 U.S. Coast Guard Service Academy gender relations survey: Overview report (OPA Report No. 2016-050). Office of People Analytics. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1075894.pdf

- *Davis, L., Klahr, A., Klauberg, W. X., Alukal, D., Wakefield, E., Puckett, G., Clark, B., Salomone, D., Elvey, K., & Lane, B. (2023). 2022 Service academy gender relations survey: Overview report (OPA Report No. 2023-021). Office of People Analytics. https://www.opa.mil/research-analysis/health-well-being/gender-relations/2022-service-academy-gender-relations-survey/2022-service-academy-gender-relations-survey-overview-report/

- *Defense Manpower Data Center. (2008). 2006 Workplace and gender relations survey of active duty members: Tabulations of responses (DMDC Report No. 2007-020). Defense Manpower Data Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA483409.pdf

- *Defense Manpower Data Center. (2012). 2012 Service academy gender relations survey. Defense Manpower Data Center. DMDC Note No. 2012-023. https://www.sapr.mil/public/docs/research/DMDC_2012_Service_Academy_Gender_Relations_Survey.pdf

- *Defense Manpower Data Center. (2013). 2012 Workplace and gender relations survey of reserve component members. Defense Manpower Data Center. DMDC Note No. 2013-002. https://www.sapr.mil/public/docs/research/2012_Workplace_and_Gender_Relations_Survey_of_Reserve_Component_Members-Survey_Note_and_Briefing.pdf

- *Defense Manpower Data Center. (2016). 2015 Workplace and gender relations survey of reserve component members: Tabulations of responses (DMDC Report No. 2016-003). Defense Manpower Data Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA630234.pdf

- Ekholm, O. (2004). Influence of the recall period on self-reported alcohol intake. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 58(1), 60–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601746

- Fitzgerald, L. F., Gelfand, M. J., & Drasgow, F. (1995). Measuring sexual harassment: Theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17(4), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1704_2

- Fitzgerald, L. F., Shullman, S. L., Bailey, N., Richards, M., Swecker, J., Gold, Y., Ormerod, M., & Weitzman, L. (1988). The incidence and dimensions of sexual harassment in academia and the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 32(2), 152–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(88)90012-7

- Forkus, S. R., Rosellini, A. J., Monteith, L. L., & Contractor, A. A. (2020). Military sexual trauma and alcohol misuse among military veterans: The roles of negative and positive emotion dysregulation. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(7), 716–724. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000604

- Forkus, S. R., Weiss, N. H., Goncharenko, S., Mamas, J., Church, M., & Contractor, A. A. (2021). Military sexual trauma and risky behaviors: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(4), 976–993. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019897338

- George, W. H., Davis, K. C., Norris, J., Heiman, J. R., Stoner, S. A., Schacht, R. L., Hendershot, C. S., & Kajumulo, K. F. (2009). Indirect effects of acute alcohol intoxication on sexual risk-taking: The roles of subjective and physiological sexual arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(4), 498–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9346-9

- Greathouse, S. M., Saunders, J., Matthews, M., Keller, K. M., & Miller, L. L. (2015). A review of the literature on sexual assault perpetrator characteristics and behaviors. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1000/RR1082/RAND_RR1082.pdf

- *Grifka, A., Davis, L., Klauberg, W., Peeples, H., Moore, A., Hylton, K., & Klahr, A., (2018). 2017 Workplace and gender relations survey of reserve component members: DoD overview report (OPA Report No. 2018-026). Office of People Analytics. https://sapr.mil/public/docs/reports/FY17_Annual/Annex_2_Workplace_and_Gender_Relations_Survey_of_Reserve_Component_Members.pdf.

- Hargrave, A. S., Maguen, S., Inslicht, S. S., Byers, A. L., Seal, K. H., Huang, A. J., & Gibson, C. J. (2022). Veterans health administration screening for military sexual trauma may not capture over half of cases among midlife women veterans. Women’s Health Issues, 32(5), 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2022.06.002

- Independent Review Commission on Sexual Assault in the Military. (2021). Hard truths and the duty to change: Recommendations from the independent review commission on sexual assault in the military. Ocotillo Press.

- *Inspector General of the Department of Defense. (2004). Evaluation of sexual assault, reprisal, and related leadership challenges at the United States Air Force Academy (Report Number IP02004C003). Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Defense. https://media.defense.gov/2018/Oct/19/2002053445/-1/-1/1/IPO2004C003-REPORT%20(SECURED).PDF

- *Inspector General of the Department of Defense. (2013). Evaluation of the military criminal investigative organizations sexual assault investigations (Report No. DODIG-2013-091). Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Defense. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA581038.pdf

- Jacobson, I. G., Williams, E. C., Seelig, A. D., Littman, A. J., Maynard, C. C., Bricker, J. B., Rull, R. P., & Boyko, E. J. (2020). Longitudinal investigation of military-specific factors associated with continued unhealthy alcohol use among a large US military cohort. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 14(4), e53–e63. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000596

- Johnson, S. M., Murphy, M. J., & Gidycz, C. A. (2017). Reliability and validity of the sexual experiences survey-short forms victimization and perpetration. Violence and Victims, 32(1), 78–92. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-15-00110

- Jones, B. S., Holtzman, E., Hillman, E. L., Jones Barbara S., Holtzman, E., Hillman, E. L., Dunn, M. E., Fernandez, M., Houck, J. W., Bryant, H., McGuire, C. L., & O’Grady Cook, H. (2014). Report of the response systems to adult sexual assault crimes panel. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3064696

- *Klahr, A. M., & Davis, L. (2019). 2018 Service Academy gender relations survey (2018 SAGR): The role of alcohol use in unwanted sexual contact (OPA Report No. 2019-030). Office of People Analytics; 2019. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1072549.pdf

- Koss, M. P., Abbey, A., Campbell, R., Cook, S., Norris, J., Testa, M., Ullman, S., West, C., & White, J. (2007). Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(4), 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00385.x

- Kwan, J., Sparrow, K., Facer-Irwin, E., Thandi, G., Fear, N. T., & MacManus, D. (2020). Prevalence of intimate partner violence perpetration among military populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 53, 101419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101419

- *Lipari, R. N., & Cook, P. (2006). 2006 Service Academy gender relations survey: Tabulations of responses (DMDC Report No. 2006-015). Defense Manpower Data Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA531591.pdf

- *Lipari, R. N., Cook, P. J., Rock, L. M., & Matos, K. (2008). 2006 Gender relations survey of active duty members (DMDC Report No. 2007-022). Defense Manpower Data Center. https://www.sapr.mil/public/docs/research/WGRA_OverviewReport.pdf

- McCauley, J. L., & Calhoun, K. S. (2008). Faulty perceptions? The impact of binge drinking history on college women’s perceived rape resistance efficacy. Addictive Behaviors, 33(12), 1540–1545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.009

- McKie, R. M., Sternin, S., Kilimnik, C. D., Levere, D. D., Humphreys, T. P., Reesor, A., & Reissing, E. D. (2021). Nonconsensual sexual experience histories of incarcerated men: A mixed methods approach. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 0306624X2110655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X211065584

- Meadows, S. O., Engel, C. C., Collins, R. L., Beckman, R. L., Cefalu, M., Hawes-Dawson, J., Doyle, M., Kress, A. M., Sontag-Padilla, L., Ramchand, R., & Williams, K. M. (2018). 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS). RAND Health Q, 8(2), 5.

- Meadows, S. O., Engel, C. C., Collins, R. L., Beckman, R. L., Breslau, J., Bloom, E. L., Dunbar, M. S., Gilbert, M., Grant, D., Dawson, J. H., Holliday, S. B., MacCarthy, S., Pedersen, E. R., Robbins, M. W., Rose, A. J., Ryan, J., Schell, T. L., & Simmons, M. M. (2021). 2018 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS): Results for the active component (RR-4222-OSD, 2021). RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4222.html

- Messman-Moore, T. L., Ward, R. M., & Brown, A. L. (2009). Substance use and PTSD symptoms impact the likelihood of rape and revictimization in college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(3), 499–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508317199

- *Miller, L. L., Keller, K. M., Wagner, L., Marcellino, W., Donohue, A. G., Greathouse, S. M., Matthews, M., & Ayer, L. (2018). Air Force sexual assault situations, settings, and offender behaviors. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1500/RR1589/RAND_RR1589.pdf

- Monks, S. M., Tomaka, J., Palacios, R., & Thompson, S. E. (2010). Sexual victimization in female and male college students: Examining the roles of alcohol use, alcohol expectancies, and sexual sensation seeking. Substance Use & Misuse, 45(13), 2258–2280. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826081003694854

- Morral, A. R., Gore, K. L., & Schell, T. L. (Eds.). (2014). Sexual assault and sexual harassment in the U.S. Military. Volume 1. Design of the 2014 RAND Military Workplace Study. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR870z1/RAND_RR870z1.pdf

- *Morral, A. R., Gore, K. L., & Schell, T. L. (2015a). Sexual assault and sexual harassment in the U.S. Military. Volume 2. Estimates for Department of Defense Service Members from the 2014 RAND Military Workplace Study. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR870z2-1/RAND_RR870z2-1.pdf

- *Morral, A. R., Gore, K. L., & Schell, T. L. (2015b). Sexual assault and sexual harassment in the U.S. Military: Annex to volume 2. Tabular results from the 2014 RAND Military Workplace Study for Department of Defense Service Members. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR870z3/RAND_RR870z3.pdf

- *Morral, A. R., Gore, K. L., & Schell, T. L. (2015c). Sexual assault and sexual harassment in the U.S. Military: Volume 3. Estimates for Coast Guard service members from the 2014 RAND Military Workplace Study. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR870z4/RAND_RR870z4.pdf

- *Morral, A. R., Gore, K. L., & Schell, T. L. (2015d). Sexual assault and sexual harassment in the U.S. Military: Annex to Volume 3. Tabular results from the 2014 RAND Military Workplace Study for Coast Guard Service Members. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR870z5/RAND_RR870z5.pdf

- Morral, A. R., Matthews, M., Cefalu, M., Schell, T. L., & Cottrell, L. (2021). Effects of sexual assault and sexual harassment on separation from the U.S. Military: Findings from the 2014 RAND military workplace study. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR870z10.html

- Newins, A. R., Wilson, L. C., & Kanefsky, R. (2021). Does sexual orientation moderate the relationship between posttraumatic cognitions and mental health outcomes following sexual assault? Psychology and Sexuality, 12(1-2), 115–128.

- *Office of People Analytics. (2019). 2018 Workplace and gender relations survey of the active duty military: Results and trends (OPA Report No. 2019-024). Office of People Analytics. https://dwp.dmdc.osd.mil/dwp/api/download?fileName=WGRA1801_ResultsandTrends_2019-024.pdf&groupName=pubGenderActive

- Parkhill, M. R., & Abbey, A. (2008). Does alcohol contribute to the confluence model of sexual assault perpetration? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(6), 529–554. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2008.27.6.529

- Parr, N. J., Young, S., Ward, R., & Mackey, K. (2021). Evidence brief: Prevalence of interpersonal partner violence/sexual assault among veterans. Evidence Synthesis Program, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. VA ESP Project #09-199.

- Pegram, S. E., & Abbey, A. (2019). Associations between sexual assault severity and psychological and physical health outcomes: Similarities and differences among African American and Caucasian Survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(19), 4020–4040. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516673626

- *Rock, L. M. (2013). 2012 Workplace and gender relations survey of active duty members: Survey note and briefing (DMDC Note 2013-007). Defense Manpower Data Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA575623.pdf

- *Rock, L. M., Lipari, L. N., Cook, P. J., & Hale, A. D. (2011). 2010 Workplace and gender relations survey of active duty members. Overview report on sexual harassment (DMDC Report No. 2011-023). Defense Manpower Data Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA541045.pdf

- *Rock, L. M., & Lipari, R. N. (2009). 2008 Gender relations survey of reserve component members (DMDC Report No. 2008-043). Defense Manpower Data Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA504471.pdf

- *Sadler, A. (1996). Sexual victimization and the military environment: Contributing factors, vocational, psychological, and medical sequelae. Veterans Administration Medical Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA328170.pdf

- *Sadler, A., Booth, B., & Cook, B. (1997). Sexual victimization and the military environment: Contributing factors, vocational, psychological, and medical sequelae. Veterans Administration Medical Center. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA345471.pdf.

- *Sadler, A. G., Booth, B. M., Cook, B. L., & Doebbeling, B. N. (2003). Factors associated with women’s risk of rape in the military environment. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 43(3), 262–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.10202

- Schumm, J. A., & Chard, K. M. (2012). Alcohol and stress in the military. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 34(4), 401–407.

- Suris, A., & Lind, L. (2008). Military sexual trauma, a review of prevalence and associated health consequences in veterans. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 9(4), 250–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838008324419

- *Thomas, P. J., & Le, S. K. (1996). Sexual harassment in the Marine Corps: Results of a 1994 survey. Navy Personnel Research and Development Center. NPRDC-TN-96-44. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA311382.pdf

- Ullman, S. E., & Najdowski, C. J. (2009). Revictimization as a moderator of psychosocial risk factors for problem drinking in female sexual assault survivors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2009.70.41

- *Van Winkle, E. P., Hurley, M., Creel, A., Severance, L., Klauberg, X., Luchman, J. N., Khun, J. L., Vega, R. P., Mann, M., Grifka, A., & Namrow, N. (2017). 2016 Service academy gender relations survey, overview report (OPA Report No. 2016-043). Office of People Analytics. https://www.sapr.mil/public/docs/reports/MSA/APY_15-16/Annex_1_2016_SAGR_Survey_Report_v2.pdf

- Wilson, L. C. (2018). The prevalence of military sexual trauma: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(5), 584–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016683459

- *Wright, J. L. (2013). Annual report on sexual harassment at the military service academies: Academic program year 2012–2013. Department of Defense Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office; 2013. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA591336.pdf