ABSTRACT

School safety and security has become a topical issue internationally that concerns both educational research and policy. However, whereas several studies have focused on technical safety, less attention has been given to comprehensive safety and security management (SSM) and policies enhancing schools’ safety culture. In order to provide new knowledge on the topic, this study addresses the following research question: What kinds of safety and security management development needs are related to a) technical, b) human and c) pedagogical leadership areas for enhancing comprehensive safety culture in Finnish basic education schools? This study uses a multiple case study approach and a multidimensional auditing tool for evaluating the SSM development needs in four Finnish basic education schools. The main findings highlight several developmental needs in the planning, implementation and evaluation for safety and security work. On these bases, this study suggests that policies and guidelines need to be improved both on the school and national levels. Particularly, special attention needs to be focused on the staff training, competence and comprehensiveness of safety and security management. The findings of this study are topical for both Finnish and international school settings that address enhancing a comprehensive and inclusive safety culture.

Introduction

School safety and security, especially the effectiveness of violence prevention programmes, have become an international topic of interest both in educational research and policy in the last few decades (e.g. Astor, Guerra, & van Acker, Citation2010; Barnes, Leite, & Smith, Citation2017). Studies originating from educational sciences, social psychology and sociology have shown that, in order for students to be able to focus on learning, school environments need to be safe, secure and nurturing (Zullig, Ghani, Collins, & Matthews-Ewald, Citation2017). Accidents, incidents, bullying, school threats and increased violence and victimization among pupils and teachers have brought issues of safety and security into public discussions in many countries during recent years (e.g. Juva, Holm, & Dovemark, Citation2018; Perumean-Chaney & Sutton, Citation2013; Zullig et al., Citation2017). The safety and security challenges encountered in educational institutions are growing in number and becoming more complex in nature, and therefore heightened attention needs to be paid to the school communities’ ability to create and maintain safety (Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2016, Citation2018; Teperi et al., Citation2018). As schools stand in a reflexive relationship vis–á–vis the society in which they operate (Astor et al., Citation2010), along with its policies it is essential to focus on how safety and security is created and discussed within schools.

Whereas issues of school safety and security have been discussed from several viewpoints, little attention has been directed towards the role of management in creating safe and secure schools. Most studies and policies have focused either on technical procedures or on procedures as a means for violence prevention, but have neglected the role of safety and security management (hence SSM), staff competence, and organizational practices in creating safe and secure schools (see e.g. Martikainen, Citation2016; Syrjäläinen, Jukarainen, Värri, & Kaupinmäki, Citation2015). In Finland, the research on school safety and security has also mainly been problem-oriented, reactive and threat-centred, but during the last decade the need to change its paradigm has been widely acknowledged (Syrjäläinen et al., Citation2015; Teperi et al., Citation2018). Yet, there exists an internationally recognized need for a more comprehensive, holistic and evidence-based approach to issues of school safety and security (Díaz-Vicario & Sallán, Citation2017; Syrjäläinen et al., Citation2015; Teperi et al., Citation2018).

The national context of this study is important as questions related to safety and security take notably different forms, depending on how the physical locations frame the security issues in question (e.g. López et al., Citation2017). The Finnish school system has been the subject of international attention over the last few decades in relation to Finnish students’ success on the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Programme for International Student Assessment Test (PISA) (Sahlberg, Citation2015). In addition to achievement scores, the findings from PISA test report that the majority of young Finnish people experience a sense of belonging at their school and also that they are satisfied with their lives. However, according to the PISA 2015 scores, one fifth of Finnish students’ report exposure to bullying at least once a year and around five percent experienced bullying at least once a week (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Citation2017). More recently a Finnish ethnographic study, brought forward deficiencies in teachers’ reactions to bullying in a lower secondary education school (Juva et al., Citation2018). Despite recognizing the presence of bullying and other threats of personal feelings of safety, systematic studies about violence or other safety and security deviations within Finnish schools are seldom carried out or reported.

In the early 2000s, Finnish schools had only little experience with large-scale security threats. At that time, the safety and security work (hence SSW) was mainly related to fire safety, first-aid skills, occupational safety and health and to the prevention of incidents and accidents (Syrjäläinen et al., Citation2015); this was especially true for safety-critical subjects, such as arts, physical exercise, physics or chemistry (see e.g. Inki, Lindfors, & Sohlo, Citation2011; Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2018). However, two school shootings in two different upper-secondary institutions in 2007 and in 2008 profoundly changed the approach to SSW in Finland (Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2016; Martikainen, Citation2016; Ministry of Justice, Citation2009, Citation2010; Teperi et al., Citation2018; Waitinen, Citation2011). On 7 November 2007, an 18-year-old student carried out a massacre in Jokela high school leading to the death of eight people and the attacker himself. Only ten months later, on 23 September 2008, a 22-year-old man carried out a similar massacre in his then-current vocational high school in Kauhajoki, killing 10 persons before killing himself. (Ministry of Justice, Citation2009, Citation2010)Footnote1

These incidents shocked Finnish society at large and highlighted the need to create more comprehensive and systematic approaches, practices and policies for creating safe and secure school environments. Whereas previously the planning, implementation and guidance for SSW in educational institutions had been a fragmented entity and mostly relied on internal sources, these incidents called for active co-operation between different actors (Martikainen, Citation2016; Waitinen, Citation2011) However, regardless of these changes, very few studies have focused on understanding the policies and practices related to comprehensive SSW, especially the comprehensive SSM in educational institutions. Although the aforementioned notorious school shootings exemplify an extreme security breach, the need to develop SSW in schools emerges from amidst the more conventional everyday risks, accidents and incidents which constitute the smaller problems in schools on a regular basis.

In order to provide new knowledge about how comprehensive safety culture can be developed in Finnish basic education schools, this study combines theories of different leadership areas and SSW practices related to them. The objective of these efforts is to identify the key elements of SSM necessary for the creation of a goal-oriented, high-quality comprehensive school-safety culture. Towards such an end, this study addresses the following research question: What kinds of safety and security management development needs are related to a) technical, b) human and c) pedagogical leadership areas for enhancing comprehensive safety culture in Finnish basic education schools? The study approaches the topic from the perspectives of four schools, their principals and SSW-groups.

Managing safety and security in schools

School safety and security

School safety has been defined in various ways in the research: it can be narrowly defined as an absence of physical, mental or moral harms or threats to learners and educators, or as a relation between people, practices and procedures that build safety in everyday actions (Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2018; Morrison & Furlong, Citation1994; Syrjäläinen et al., Citation2015). Many international studies, originating from different disciplines, have approached questions of school safety and security from the partially overlapping perspectives, such as physical safety, safety of school buildings, the socio-emotional aspects often associated with experiences of the social climate, interaction in school, pedagogical safety or the operational culture of the school (e.g. Bradshaw, Waasdorp, Debnam, & Lindström Johnson, Citation2014; Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2016, Citation2018; López et al., Citation2017). The social and emotional aspects of safety refer to the relationships that students and staff members of the school experience within the school and, to some extent, outside the school (e.g. Díaz-Vicario & Sallán, Citation2017; López et al., Citation2017; Syrjäläinen et al., Citation2015). Multiple studies have shown that relationships with peers and teachers, prevention of bullying and a sense of community are central to students’ well-being and the fostering of school safety (e.g. Bradshaw et al., Citation2014; López et al., Citation2017; Syrjäläinen et al., Citation2015). The pedagogical dimension of safety typically refers to the ways in which teaching and learning have been arranged in schools: learning contents and objects, rules and equity, inclusion and communality, possibilities for influence, responsibilities and peer support (Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2018). By contrast, insecurity among Finnish students has been reported to be on the rise, for example, for fear of being bullied or from excessive freedom of action in schools (Syrjäläinen et al., Citation2015).

School safety can thus be seen to be a part of the general school climate or school culture (e.g. Bradshaw et al., Citation2014). To develop it systematically, however, it is important to distinguish between the overall experience of safety and the particular safety and security procedures that aim to mitigate harm in situations of hazard or violence. Physical safety forms the basis for SSW, since it is difficult to consider social and emotional safety when feeling physically unsafe (Díaz-Vicario & Sallán, Citation2017; Maslow, Citation1970). Whereas questions of physical safety and security have been emphasized in international studies, a more comprehensive approach to improving school safety has been mostly ignored (Langman, Citation2009; Perumean-Chaney & Sutton, Citation2013; Teperi et al., Citation2018).

Given the complex, multifaceted nature of school safety and security, this study views SSW in schools from a comprehensive perspective that includes physical, emotional, and social aspects (see also Morrison & Furlong, Citation1994). SSW in schools is thus defined in this study as an entity that aims to support and enhance safety culture and that includes not only emergency drills, injury and violence prevention but also crime prevention, occupational health and safety, rescue operations, contingency planning, environmental safety, premises security, personal security, information security and safety and security of production and operations (see also Confederation of Finnish industries, Citation2011; Morrison & Furlong, Citation1994). In this research, school safety and security work (SSW) is combined into one concept, primarily due to the holistic and comprehensive approach of this research, but also because in the Finnish language there exists no separate concepts for safety and security.

Safety culture in schools

Despite the considerable academic research on safety, there is no universal consensus or definition of the complex construct of safety culture (Biggs, Banks, Davey, & Freeman, Citation2013; Clarke, Citation2003; Teperi et al., Citation2018). Nonetheless, the term safety culture is often used to refer to the aspect of an organization’s culture that relates to safety issues. The key components of safety culture can be classified into themes such as safety knowledge, values and attitudes, the community’s commitment to safety, motivation and skills, management’s concern for staff well-being, level of safety training as well as transparency and sufficiency of communication (Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2016; Neal, Griffin, & Hart, Citation2000; Waitinen, Citation2011). According to Clarke (Citation2003), in communities, in which a positive safety culture exists, there prevails a shared consensus that safety is always prioritized.

Safety culture is reflected in the strength of the SSM system and management’s commitment is a key factor in positive safety culture, positive staff-safety behaviour and positive staff-safety attitudes (Biggs et al., Citation2013; Mearns, Whitaker, & Flin, Citation2003). Every organization has a safety culture that affects the level of safety in a strong, positive, weak or negative way (Nordlöf, Wiitawaara, Winblad, Wijk & Westerling, Citation2015; Waitinen, Citation2011). Safety culture can thus contribute to both safe and unsafe ways of operating within the organization. The creation of an advanced safety culture requires a broad, systematic approach, which should involve not only the management but should engage all the individuals operating within the organization (Biggs et al., Citation2013; Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2016, Citation2018; Nordlöf et al., Citation2015; Waitinen, Citation2011), such as teachers, parents, other relevant stakeholders and students (Syrjäläinen et al., Citation2015).

According to Waitinen’s (Citation2011) and Teperi et al.’s EduSafe (Citation2018) studies, one of the greatest threats – in the context of Finnish basic-education school’s safety culture – was the idea of outsourcing SSW to other authorities, instead of proactively developing and maintaining it from the inside of the organization. Educators’ agency and the recognition of one’s own roles and responsibilities in promoting school safety and security – and through it the overall safety culture – was seen to be fragmented in nature. In addition, severe deficiencies in safety-and-security-related competence and knowledge was found in both studies.

Regarding the question of SSM, distributed leadership (see Gronn, Citation2002; Timperley, Citation2005) can thus be identified as a central starting point for involving the entire staff in the creation of a safety culture. According to Nordlöf et al. (Citation2015), safe and relevant working practices should be developed within the organization itself, instead of being imposed from higher up in the organization. Safety culture is largely a result of how people think and act in relation to safety during day-to-day school activities and processes (Biggs et al., Citation2013; Díaz-Vicario & Sallán Citation2017; Waitinen, Citation2011). Since a high level of perceived safety is often used to justify a reduction in safety efforts (Hollnagel, Citation2014), the creation, maintenance and development of safety culture must be seen as a dynamic and continuous process, rather than a static outcome. The role of national policies and practices in creating guidelines for steering the formation of collaborative and agile safety culture and for informing procedures and practices is central.

The safety culture of schools somehow differs from other organizations’ safety culture, since – in addition to safety culture’s creation, maintenance and evaluation – schools also need to provide a curriculum-based safety education for pupils (Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2018). This is necessary, in order for them to be able to learn how to keep themselves safe and to act appropriately, for example, in emergencies or accidents. Pupils cannot, however, under any circumstances, be held responsible for safety and security operations or actions, since the full responsibility within the school day falls unequivocally on the teachers and principals (Basic Education Act, 628/Citation1998).There are also many factors differentiating schools from other organizations, such as heterogeneous age distribution, which means, that in school communities there are significantly different responsibilities, roles and knowledge between actors in relation to safety culture’s creation, implementation, maintenance and evaluation (Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2018).

Safety and security management (SSM) in schools

Since principals are fully responsible for the operations in Finnish schools, they also act as a safety and security manager in their schools. SSM relates to the practices, structures and implementations associated with remaining safe and secure and creating overall safety. SSM is thus fundamentally an issue of regulation and control, since the aim is to have interventions that steer the level of safety in the desired direction (Hollnagel, Citation2014). Mearns et al. (Citation2003) listed ideal SSM practices that included, for example, management’s commitment to safety and security, relevant safety communication and staff’s involvement in SSW. In a comprehensive safety culture, issues of safety and security should be taken into consideration in all aspects of school management and organizational and operational policies and guidelines (Díaz-Vicario & Sallán, Citation2017). However, studies show that a comprehensive SSM approach is rarely fully adopted by school leaders (Díaz-Vicario & Sallán, Citation2017; Martikainen, Citation2016; Teperi et al., Citation2018). In order to identify different ways in which schools can manage and develop a comprehensive safety culture, this study approaches the question of SSM through three core leadership areas: technical, human and pedagogical, aiming also to state that SSM issues are not detached from other management work. These different leadership areas have been identified internationally as central, partially overlapping areas of leadership and forming a holistic and integrative body of principalship (see e. g. Hämäläinen, Taipale, Salonen, Nieminen, & Ahonen, Citation2002; Lahtero & Kuusilehto-Awale, Citation2015; Sergiovanni, Citation2006)

The tasks of technical leadership related to routine administration include paperwork and decision-making. This mode of leadership focuses on structures, planning, organizing, timetabling, budgeting, and taking advantage of strategies and situations to ensure efficiency in operations (Lahtero & Kuusilehto-Awale, Citation2015); in other words, the focus is on coordinating the structures and daily functioning of a school community (Sergiovanni, Citation2006). According to the study by Lahtero & Kuuselehto-Awale (Citation2015) on newly appointed Finnish principals, there should be more possibilities for delegating technical leadership-related tasks among the school community, for example to secretaries and through distributed leadership.

Human leadership sees people to be the core of the organization and aims to make sure that employees pursue common objectives and are committed to them. Typical human leadership tasks include providing support and being present, managing problematic situations, interacting with members of the community, taking care of staff well-being, pursuing a well-functioning school community through cooperation, and leading the capacity and competence of the staff. Tasks related to human leadership are most often comprised of changing and challenging situations (Lahtero & Kuusilehto-Awale, Citation2015), to which ready formulas rarely exists.

The third leadership area is pedagogical leadership, also referred to as instructional leadership in the international literature. Pedagogic leadership focuses on: leading and facilitating the development of teaching and learning; setting goals and enabling the conditions for good teaching and learning; giving support and feedback; creating an open discussion culture; monitoring the implementation of the curriculum; interacting with pupils and staff; having pedagogical discussions and developing the school culture in line with generally agreed upon objectives (Hämäläinen et al., Citation2002; Lahtero & Kuusilehto-Awale, Citation2015; Plessis, Citation2014; Sergiovanni, Citation2006). In this study the concept of pedagogical leadership is used as is it fits better in the Finnish context than instructional leadership, as Finnish teachers and principals mostly have the same qualification of a master’s degree. Moreover, instead of having a top-down relationship, teachers and principals in Finland are rather co-operative and interactive (Lahtero & Kuusilehto-Awale, Citation2013, Citation2015; Sahlberg, Citation2015).

According to Finnish studies and policy-documents, pedagogical leadership should be regarded as the most important area of leadership (NBE, Citation2013). In practice, however, and due to the enhanced role of technical and human leadership tasks, the least number of working hours are devoted to it (Juusenaho, Citation2004; Lahtero & Kuusilehto-Awale, Citation2015; Mäkelä, Citation2007). As research on distributed leadership and its importance has increased and becomes more widely acknowledged (see e.g. Harris & Jones, Citation2017), it has been realized that the role of middle leaders is crucial in developing and maintaining the quality of pupils’ learning experiences (Harris & Jones, Citation2010, Citation2017). In addition, middle leaders help to establish joint responsibility throughout the whole school community (Bendikson, Robinson, & Hattie, Citation2012), which in turn can be seen as a prerequisite for the sustainable creation of schools’ safety culture. Therefore, the significance of distributed leadership, also in the context of SSM should be more profoundly utilized.

In addition, for all three core areas of competent leadership, according to Hämäläinen et al. (Citation2002) and Segiovanni (Citation2006), an excellent principal is also a symbolic figure and a leader in developing the school culture.

Materials and methods

Research design

This study uses a multiple-case-study approach to generate a deep understanding of various dimensions of comprehensive SSM and its development needs in four Finnish basic education schools. As Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (Citation2000) have pointed out, case studies can provide rich and vivid descriptions and, in our case, the aim of the study was to provide instances of the real status of SSW and SSM in Finnish schools.

Tutor – safety and security risk assessment auditing model as a tool for data collection

Data for this research were collected from four Finnish basic education schools. Basic education in Finland lasts nine years and applies to all 7- to 16-year-old pupils. Data from the participating schools were collected during four separate auditing sessions that were carried out in 2013. In the data collection a tool called ‘Tutor – Safety and Security Risk Assessment auditing model’ was applied to investigate various aspects of the school’s SSM, safety culture and SSW practices. All of the schools participated in these audits voluntarily on the basis of their own interest in SSM’s development. Tutor auditing tool had originally been developed by the Finnish rescue authority, Keski-Uusimaa Department for Rescue Services (Citation2011), for inspecting or auditing SSW on a large scale in different organizations. It has also been widely used for general assessments, practical development and research in SSW and SSM in Finland (Martikainen, Citation2016). The Tutor tool applies a comprehensive approach, and it encompasses all the safety and security components mentioned earlier in this article (see e.g. Confederation of Finnish industries, Citation2011). During the audits, the aim was to determine participating schools’ SSW statuses and practices, and also the development needs related to SSM. The first author of this article collected the data from the audit sessions but did not act as an official auditor for the schools.

The audit session for each school lasted about three hours and included qualitative focus group discussion and quantitative numeric assessments, both related to the Tutor audit model’s main and subthemes. These main and subthemes, which are illustrated in detail in below, created the frame for semi-structured focus group discussions. The content of the audits was based on the structure of the Tutor tool and covered the following eight main themes: 1) safety and security management, 2) operational risks, 3) compliance with requirements, 4) safety and security documentations, 5) facility management technology and safety/security technology, 6) training, 7) safety and security communication and 8) results and effectiveness (Martikainen, Citation2016). Each main theme was further divided into individual subthemes for more detailed analysis, so that the audit consisted of altogether 23 subthemes.

Table 1. The main areas and sub-themes of the Tutor audit model, translated from Finnish (according to Martikainen, Citation2016).

Despite the fact that the audits produced both qualitative and quantitative data, in this study, only the qualitative data, which were collected through semi-structured focus group discussions, will be analysed. The focus groups comprised of the safety group members of each school. Safety groups in Finnish basic-education schools usually comprise of 2–4 employees with more know-how on SSW related issues and are most often led by a principal. School types, grade levels, number of teachers, enrolment and composition of the school’s safety group and code of informants are presented in .

Table 2. Research schools.

Discussion themes for focus groups arose systematically from the Tutor auditing tool. For example, discussions related to the need for staff training on issues related to SSW were based on the main theme section 6. ‘Training’ that included a subtheme 6.2. ‘adequacy of training’. Altogether, four mutually comparable focus group discussions, in Schools A, B, C, and D, were carried out with a total of 15 school’s safety group members and principals. Composition of the focus groups and the code of informants are presented in . The discussions resulted in a total of approximately 12 hours of recorded material and 259 pages of transcribed data.

Data analysis

In order to answer the research question, ‘What kinds of safety and security management development needs are related to a) technical, b) human, and c) pedagogical leadership areas for enhancing comprehensive safety culture in Finnish basic education schools?’, the semi-structured discussion data were analysed by the first author using thematic, theory-driven content analysis (e.g. Cohen et al., Citation2000). The transcribed discussions were read, and reduced expressions related to SSW development needs were highlighted. In the following phase, these reduced expressions were re-grouped into sub-themes and were used to identify the main themes of development needs (e.g. Cohen et al., Citation2000). For example, sub-themes related to the deficiencies and lack of SSW related training were grouped within a main theme entitled Safety- and security-related training and competence. In the second round of analysis, the main themes were classified according to the three leadership areas of technical, human, and pedagogical leadership. This was done in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of how the identified development needs fall under the different areas of school leadership. Original quotations (translated from Finnish) will supplement the analysis.

Findings

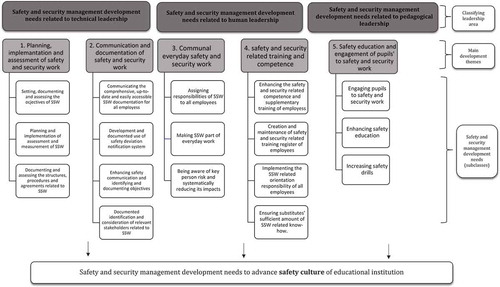

In this section, we will present five main themes and 17 subclasses of SSM development needs in relation to the technical, human, and pedagogical leadership areas identified from the focus group discussions during the audit sessions. The findings are summarized in below.

Safety and security management development needs related to technical leadership

In relation to technical leadership, seven subclasses of SSM development needs were identified. Subclasses were categorized under two main themes, titled 1) Planning, implementation, and assessment of safety and security work and 2) Communication and documentation of safety and security work.

Planning, implementation, and assessment of safety and security work

The starting point of each audit situation was to recognize the principles and objectives of schools’ SSW. Despite extensive debate, none of the audited schools had defined or documented the objectives of their SSW or explicitly stated safety as a value for guiding operations. Non-documented objectives may lead to subjective interpretations of common goals and this fragmented starting point is well highlighted in the following quote [1]:

[1] Teacher C3: Yes, we have had a lot of discussion about things [related to SSW], but no objectives have been discussed or documented. [SSW] is so practical, that we have not gone to the next level to think about those [objectives].

As was found in all the participating schools, the development and assessment of SSW and its impacts is possible only if the organization carries out systematic evaluation and measurement. Evaluation and measurement is impossible, however, if no general objectives have been set. The comprehensive nature of SSW was not formed in the participating schools, and one of the key problems was the unstructured nature of safety culture, as highlighted in the following quotes [2 and 3]:

[2] Principal A4: We do not have an overall picture [of SSW]. The lack of a complete picture bothers me. […] From time to time, we should remind ourselves of what is designed [as objectives of SSW], because otherwise it will be forgotten in this busy everyday life.

[3] Principal D1: We lack a certain kind of operational culture [to act as planned in relation to SSW matters].

Teacher D2: I meant to say the same thing, that the operational culture has not been structured in a way where we can say that the entire staff would act according to the same plan or formula.

Another key theme mentioned by all participating schools was risk identification and management as one of the most important factors in creating an atmosphere of safety. The findings show that the schools commonly lacked agreed upon guidelines for risk management. In cases where schools had identified certain risks, there were many agreed upon responsibilities for managing a particular risk, without documentation of the person responsible for it. Another challenge was also seen to be the low level of risk management competence, as seen in the following quotes [4 and 5]:

[4] Teacher C3: Schools do not necessarily have any risk know-how. […] Who here would be able to make a risk analysis of what [of the identified risks] would be the most important things to do?

[5] Principal A4: It bothers me [in risk management] that we get stuck with minor details and concentrate on unimportant details.

Communication and documentation of safety and security work

In all the participating schools, the complex entity of SSW-related documents and plans was discussed during the audit situations. The main reason for this complexity was that the legislation and policies determining and guiding SSW in schools was seen to be abundant.

The biggest challenge for schools was to communicate safety plans and instructions to all staff members, including those who were absent when these plans were being introduced, as well as relevant stakeholders and cleaners, cooks, nurses, and pupil care staff. This challenge is expressed in the quote [6] below, but similar challenges were mentioned in all the participating schools.

[6] Principal C2: Communication [of SSW plans and documents] is a real challenge for leadership and management […]. Today we noticed that our school psychologist is new, and our pupil care team realized that they have not had any SSW induction in our school.

The discussions also highlighted the general lack and fragmented operational culture of documentation related to safety and security deviation notifications. The participating schools pointed out that safety and security deviation notifications are particularly important as part of legal responsibilities and that they protect the principal in particular. However, a key problem in this regard was setting limits in order to determine violations of safety and security procedures, as was highlighted in the discussion in schools A and D, quotes [7 and 8]:

[7] Principal D1: I would still say that systems exist for safety and security deviation notifications, or near or close to accident situations […]. It is then up to a more operational culture to determine how each [employee] will then decide to act.

[8] Teacher A2: Where is the boundary between what is being reported and what is not? In this workplace, there’s a million things related to safety every day.

Of all the participating schools, only School C locked its doors during school days. Despite these locked doors, however, School C reported that there was no access control, and unknown persons, for example, real estate contractors, could enter the school without any of the permanent staff knowing who they were. School A discussed the same issue, and an alarming deficiency [quote 9], was recognized and explained by the openness of Finnish society. In Finland, in principle, anyone has the right to attend lessons in schools.

[9] Principal A4: But if you think of those safety and security deviation notifications, it’s still pretty uncertain who [of the staff] announces and who does not when an unknown person walks along the [school’s] corridors.

Another topic that was much debated in the category of documentation and communication was stakeholder groups and their impact on school safety and security. None of the participating schools had identified relevant stakeholder groups, nor was the impact of stakeholders on safety and security considered. As can be seen in the comment below [quote 10], stakeholders have not been considered as relevant actors for school safety. All participating schools also felt that stakeholders were difficult to manage due to their diversity.

[10] Principal C2: I am sure that I will have some nightmare about these stakeholders tonight and all the things they can do. […] We really have not considered stakeholders at all in the SSW context.

Safety and security management development needs related to human leadership

In relation to human leadership, seven subclasses of SSM development needs were identified. Subclasses were categorized under two main themes, entitled 3) Communal everyday safety and security work and 4) Safety- and security-related training and competence.

Communal everyday safety and security work

All of the participating schools had a special SSW group headed by the principal. A key issue in communal SSW was the division of staff to create a specific SSW group, of which compositions can be seen in . In Schools B and C, this division had led to individual employees, not members of the SSW group, being viewed as unaware of their responsibility in SSW [quote 11].

[11] Principal B3: In the school world, the teacher is responsible for his/her own class and, of course, its safety. You easily miss the general safety. Who is responsible for it?

[…]

Teacher B2: The goal would be to have all the staff understand and be slightly open to the view that, oh yeah, [comprehensive SSW] belongs to me too. It would mean a lot’ for bringing about a better SSW.

Related to the ambiguity of responsibilities, Principal B3 pointed out that the biggest challenge was to put an end to the attitude of indifference and the idea that the development and maintenance of a school’s safety and security does not concern all staff members. The management of staff’s motivation is central to this issue. As the following quote [12] shows, it takes an effort to integrate SSW into core work:

[12] Teacher C3: I have worked as a safety officer [teacher responsible for safety] in our school for 6–7 years, and SSW thinking has changed a lot during this time. In the past, it was mainly about bombs and air-raid shelters. [In t]hose days, I thought, ‘Damn these security trainings. Do I really have to go there? These are not related to my job description anyway.’ But, little by little I have understood what this general [comprehensive] SSW means. […] In schools, all changes are slow, but thinking should be changed to make sure that staff […] [knows] that [SSW] should be part of normal, everyday life and thinking.

Teacher C4: Yes, SSW should be part of everyday life. [Just] as one teaches maths and reading, you [should internalize] what safety and security in schools means.

[…]

Teacher C3: [The challenge is] how to incorporate SSW into the core job, because, if it is not included, it looks like a fragmented extra task.

The participants also pointed out that, because of staff changes, responsibilities related to SSW should be shared by all of the staff, so that they are not as person-centred anymore. For example, in School A, it was noticed that there was ‘a terrible number of verbal agreements [about SSW related things’] that were not accessible by all of the staff. This was found to disturb the creation of a permanent and comprehensive safety culture within the school [quote 13]:

[13] Principal C2: I’d say that changes in personnel are a problem not just in schools but in just about every workplace. […] If Laura or Hanna is in charge of something, next year it might be someone else, Maria or Harri. There should be some other way [than person-centred] to describe who is responsible for certain things [related to SSW], so that it would be a more permanent definition.

Another core issue related to person-centeredness was that it had led to a key-person risk in all of the participating schools. The key-person risk refers to situations where an individual employee, usually the principal, has knowledge or skills that others do not have. In School B, the SSW group members felt that the key-person risk was a core problem and that it was therefore of utmost importance to involve the entire staff in SSW. The key-person risk and the growing responsibilities of principals were subjects of discussion in all the schools, as seen in the quotes [14 and 15]:

[14] Principal B3: There are many things that only I know about – things I’ve quickly taken care of without informing or bothering others about. That may not always be such a wise way to do things.

[15] Teacher D2: But in the end, I think that no one is responsible [for things] as much as principals are. The amount of responsibility is just insane and unbearable.

Safety- and security-related training and competence

Safety and security related training and competence issues were seen to be fragmented in nature in all participating schools. In participating schools A and B, concerns about SSW expertise and competence in specific situations emerged strongly as human resource management issues. According to the SSW group members, the schools did not have enough practical expertise in SSW-related themes, and changes in staff and low levels of safety and security education in Teacher Education were seen to be big challenges [quote 16]:

[16] Teacher A2: We have a working community where a lot of staff changes take place. And then if someone is trained for the job [of safety officer], what happens when he or she is not here next year?

Principal A4: Yeah. But as long as the Department of Teacher Education does not educate people with SSW [related] skills, there is nothing we can do […].

Uncertainty related to SSW competence was also mentioned as impeding the staff’s feeling of safety in School C, where undocumented procedures with a large number of non-trained substitutes contributed to low levels of overall safety and security. Particularly short-time substitutes were seen to be critical personnel groups in SSW. None of the participating schools thought that substitutes were oriented well enough for SSW, as can be seen in the following quote [17]:

[17] Principal C2: Of course, our Achilles heel is new employees and substitutes. If a substitute comes to our school in the morning, it’s unlikely that he or she knows about our safety or security practices.

In relation to personnel training, the safety and security training gained during teacher education was seen to be inadequate, as mentioned in the previous comment [quote 18]. Other weaknesses were seen to be the low level of supplementary training related to safety and security issues as well as the low level of participation in the trainings when they occurred. Training had not been offered as a proactive or preventative act for the entire staff, since SSW training was only offered to the school management in Schools C and D. These kinds of procedures do not reduce the previously mentioned key-person risk. The lack of SSW training was justified by the lack of financial resources, which in School C were seen to be compensated by successful leading of motivation in SSW-related issues [quote 18]:

[18] Principal C2: The motivation [towards SSW] is free, and [of] that motivation we have a lot.

Another deficiency related to training was poor documentation and the absence of a comprehensive safety and security training register, which in itself would help the principal in leading SSW-related competence in a more structured way.

Safety and security management development needs related to pedagogical leadership

In relation to pedagogical leadership, three subclasses of SSM development needs were identified. Subclasses were categorized under the main theme, entitled as 5) Safety education and engagement of pupils with SSW.

Safety education and pupils’ engagement with safety and security work

According to discussions during the audit sessions, the schools did not engage pupils in safety and security thinking to exploit their resources and views on SSW. Pedagogues in participating schools thought that involving pupils in SSW was important but that pupils could not be held responsible for it. In relation to this, one important need to develop further was improving pupils’ understanding of safety and security issues and the observation of the environment. The desirable nature of safety education was mentioned in quote [19]:

[19] Principal C3: There should not be a sense that they [pupils] should be responsible for something [related to SSW] that does not belong to them. But they should have the skills to act in different situations.

[…]

Teacher C4: [Pupils] should learn to manage certain everyday situations if adults are not present.

Pedagogues in all four schools highlighted that safety education should not focus on threats, risks and things that could go wrong but focus on positive togetherness, a sense of membership and observations of development areas. It was also seen [quote 20] that effective SSW is about learning together, sharing good practices and raising pupils’ awareness.

[20] Principal B3: [A] shaming approach/attitude must be removed. Not like ‘How can you not know how to deal with a fire, shame on you!’ It should be taught, learned and practiced together.

Another key issue was the fact that none of the schools had practiced gas-accident related or lockdown safety drills. As can be seen in the following quote [21], justifying the need for lockdown drills, without causing a feeling of insecurity, was an issue.

[21] Principal B3: Although the need for lockdown drills is probably more necessary [than fire drills], they are not yet practiced. The challenge is to justify [the reason for] training to pupils in times when the school shootings [in Finland] are still fresh in memory.

Discussion

Focusing on the internationally relevant theme of school safety and security (e.g. Astor et al., Citation2010; Barnes et al., Citation2017), this study used a multiple-case-study approach to identify and provide new knowledge about how the safety culture of schools could be enhanced through a comprehensive SSM approach. Identified SSM development needs were further divided into categories of technical, human and pedagogical leadership. The main findings from the study bring forward the notable need for the development of safety and security related competences as well as practices on SSW in basic education schools.

In relation to technical leadership, findings highlighted the need for school leaders to focus on objectives and evaluation, clear structures, and implementations in order to develop a comprehensive safety culture in schools. Such procedures act as guidelines that regulate how people act and build or disrupt the safety culture in their everyday actions (see also Biggs et al., Citation2013; Díaz-Vicario & Sallán, Citation2017). The findings also highlighted the importance of sharing technical instructions and guidelines openly amongst school staff and of developing functional communication and documentation methods. These results thus support the findings of previous studies about the importance of communication and of sharing knowledge about procedures with the entire staff in order to develop a comprehensive safety culture (see also Biggs et al., Citation2013; Mearns et al., Citation2003; Nordlöf et al., Citation2015).

In relation to human leadership, notable deficiencies in the well-being of staff in relation to sense of safety, management of competence and communal SSW in participating schools were found. Due to key-person risk (see also Teperi et al., Citation2018), the implementation and development of SSW by the principal alone is not a sustainable way to develop the safety culture of the school. To reduce the impact of key-person risk, which was present in all the participating schools, the findings of this study highlight the need for school leaders to share SSW related responsibilities (see Díaz-Vicario & Sallán, Citation2017) through distributed leadership (Timperley, Citation2005) and to create practices for school SSW in ways that involve the entire staff. These findings are consistent with previous studies arguing that, when developing school-safety culture, emphasis should be given to getting the entire staff involved in the safety and security agendas (Biggs et al., Citation2013; Mearns et al., Citation2003; Teperi et al., Citation2018). When leading staff competence in SSW-related themes, the need for and content of SSW training should be planned in accordance with personnel group, risk assessment, classification and prioritization, since the training that principals need differs greatly from the training that, for example, the school nurses or janitors need. The SSW related training was not implemented comprehensively in the participating schools’, and low levels of SSW-related competence emerged in all the participating schools.

This issue of educators’ SSW-related competence is largely an issue of national policy, that needs to be examined considerably more widely in the future since, in addition to this study, also other studies and policy documents have been criticized the Finnish Teacher Education system for the fragmented and deficient nature of the safety and security education that is provided for teacher students (see also Waitinen, Citation2011). Hence, the social value of safety and security should be more clearly emphasized, for example in the curricula for teacher education (see also Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2016; Ministry of Education and Culture, Citation2013; Waitinen, Citation2011). Besides the educators’ competence, another important question concerns financial resources. Based on discussions, it is clear that certain schools have a high intent to develop SSW. However, this is not always enough, because the jurisdiction of individual public schools, is limited. This thus proposes a need for high-level decision and policy-makers to emphasize the importance of SSW in schools and to provide resources for it.

Related to pedagogical leadership, the findings emphasized the need to strengthen pupils’ involvement in SSW, sense of membership, safety and security-related know-how, and general safety education. Since values cannot be instilled in pupils merely by talking to them, schools should create a growth and learning environment in which pupils address themselves towards certain values. Creating such an environment is important for a comprehensive safety education as well as for creating a truly comprehensive safety culture among the whole school community. Similar to previous studies (e.g. Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2018; Syrjäläinen et al., Citation2015), this study recognizes the need to include views and engage pupils in the formulation, development, and assessment of a comprehensive school-safety culture. Pupils’ engagement can be seen as a salient part of pedagogical SSM, as it needs to be clearly emphasized as a core value of SSW. However, as the findings of this study highlight, without clear objectives, guidelines and practices there is the risk that pupils are put in unequal positions regarding their opportunities to participate and develop their own safety and security related competencies. Therefore, the planning, implementation, and assessment of SSW should not be carried out only by authorities or by the adults of the schools (see also Lindfors & Somerkoski, Citation2018; Syrjäläinen et al., Citation2015).

Regarding the limitation of this study, it needs to be noted that, as a multiple-case study, in which only four basic education schools were studied, findings cannot be taken as representative of the general experience of all school communities in Finland or elsewhere. Instead, local and regional differences may lead to different usability of the results in other contexts (e.g. Astor et al., Citation2010). It also needs to be noted that the data were collected by applying a tool (Tutor), developed by the Finnish authorities, which had a specific focus on the areas that it covered. Although the Tutor tool covered all the aspects of safety and security – as mentioned in the definition of the Confederation of Finnish industries (Citation2011) – it was specifically developed for a wide variety of organizations. As a result, some areas, specifically characteristic for schools, were not represented. For instance, the pedagogically relevant pupils’ engagement with SSW according to their age and abilities, had to be specifically brought up in every discussion.

Nevertheless, by spotlighting the most topical developmental needs in the context of Finnish basic education, this study contributes to the internationally important, but limited knowledge about, policies and practices that are needed for creating a holistic school-safety culture (Díaz-Vicario & Sallán, Citation2017; Syrjäläinen et al., Citation2015) through comprehensive SSM. The data for this study were collected in 2013, but the findings are still up-to-date as no major changes or guidelines regarding the SSW in schools have taken place in Finland since. Based on the findings related to the developmental needs in leadership related to school safety and security, this study has suggestions for future work in this area. Such future studies should pay more attention to the ways in which policies created to enhance safety culture at the level of leadership are transmitted into practices and thereby influence the experiences of all school members, such as teachers and pupils. In sum, studies focusing on the experiences of teachers and pupils, in addition to leadership, would be important for developing inclusive and holistic safety policies and practices.

Conclusion

Issues of school safety and security have become increasingly topical in many countries during recent years (e.g. Perumean-Chaney & Sutton, Citation2013; Zullig et al., Citation2017) highlighting the importance of policies and regulations supporting comprehensive safety culture that covers the physical as well as emotional safety of all actors in the school (Díaz-Vicario & Sallán, Citation2017; Maslow, Citation1970). However, policy guidelines and suggestions aiming to develop schools’ safety and security are not beneficial if they remain unfulfilled in the macro-level or in the everyday practices of the schools (see e.g Valonen, Citation2012). This was for example the case in the aftermath of 2007 and 2008 school shootings, after which altogether 22 suggestions for the prevention of future school shootings were made, but of which only few were fully implemented (Ministry of Justice, Citation2009, Citation2010; Valonen, Citation2012). Therefore in order for the suggested policy guidelines and regulations to be effectively and in a sustainable way implemented in school level actions, it is necessary that principals are capable to integrate and see those to be a part of their general everyday technical, human and pedagogical leadership (see Lahtero & Kuusilehto-Awale, Citation2015). Through this safety and security management will not be seen as a separate task and safety culture can be developed in line with more general school culture.

As the findings of this study bring forward, there are many definiencies related to SSM in Finland, and therefore the findings of this study suggest that there is a need to put more emphasis on the safety and security training. In addition, for guaranteeing the creation of an comprehensive safety culture, safety and security issues should also be discussed more thoroughly in pre-service teacher and principal training as well as supported through in-service trainings. Whereas the findings of this study are focused on the Finnish context, the study provides insights regarding the key components of holistic safety and security managemt also in other contexts. Especially the findings suggest that it is important to pay attention not only to the physical safety and technical leadership of SSW but to consciously develop the emotional and social safety in schools through human and pedagogic leadership and comprehensive safety culture.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. While writing this article, on 1 October 2019 one student died and ten wounded in a violent attack carried out by a 25-year-old student in his vocational institution in the city of Kuopio.

References

- Astor, R. A., Guerra, N., & van Acker, R. (2010). How can we improve school safety research? Educational Researcher, 39(1), 69–78.

- Barnes, T. N., Leite, W., & Smith, S. W. (2017). A quasi-experimental analysis of schoolwide violence prevention programs. Journal of School Violence, 16(1), 49–67.

- Basic Education Act. (628/1998).

- Bendikson, L., Robinson, V., & Hattie, J. (2012). Principals’ instructional leadership and secondary school performance. Research Information for Teachers, (1), 2–8.

- Biggs, S., Banks, T., Davey, J., & Freeman, J. (2013). Safety leaders’ perceptions of safety culture in a large australasian construction organisation. Safety Science, 52, 3–12.

- Bradshaw, C., Waasdorp, T., Debnam, K., & Lindström Johnson, S. (2014). Measuring school climate in high schools: A focus on safety, engagement, and the environment. Journal of School Health, 84(9), 593–604.

- Clarke, S. (2003). The contemporary workforce – Implications for organizational safety culture. Personnel Review, 32(1), 40–57.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research methods in education (5th ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

- Confederation of Finnish industries. (2011). Corporate Security. Helsinki: Author.

- Díaz-Vicario, A., & Sallán, J. G. (2017). A comprehensive approach to managing school safety: case studies in Catalonia, Spain. Educational Research, 59(1), 89–106.

- Gronn, P. (2002). Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(4), 423–451.

- Hämäläinen, K., Taipale, A., Salonen, M., Nieminen, T., & Ahonen, J. (2002). Oppilaitoksen johtaminen [Leading an educational institution]. Helsinki: WSOY.

- Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2010). Professional learning communities in action. London, UK: Leannta Press.

- Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2017). Middle leaders matter: Reflections, recognition, and renaissance. School Leadership & Management, 37(3), 213–216.

- Hollnagel, E. (2014). Safety-I and safety-II. The past and future of safety management. London, UK: CRC Press.

- Inki, J., Lindfors, E., & Sohlo, J. (2011). Käsityön työturvallisuusopas perusopetuksen teknisen työn ja tekstiilityön opetukseen [Safety guide for the teaching of basic education’s craft subjects] (pp. 15). Opetushallitus, Oppaat ja käsikirjat. Helsinki.

- Juusenaho, R. (2004). Peruskoulun rehtoreiden johtamisen eroja - sukupuolinen näkökulma [Differences in comprehensive school leadershipand management. A gender-based approach] (pp. 249). Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä Studies in Education, Psychology and Social Research.

- Juva, I., Holm, G., & Dovemark, M. (2018). He failed to find his place in this school. Re-examining the role of teachers in bullying in a Finnish comprehensive school. Ethnography And Education, 15(1), 1–15.

- Keski-Uudenmaan pelastuslaitos. (2011). Pelastusviranomaisen valvontasuunnitelman mukainen turvallisuustoiminnan riskienarviointimalli – Tutor Max (suurasiakasversio) [Safety and security model risk assessment model, in accordance with the rescue authority’s supervisory plan - tutor max (Large client version)]. Vantaa: Keski-Uudenmaan pelastuslaitos.

- Lahtero, T., & Kuusilehto-Awale, L. (2013). Realisation of strategic leadership in leadership teams’ work as experienced by the leadership team members of basic education schools. School Leadership & Management, 33(5), 457–472.

- Lahtero, T., & Kuusilehto-Awale, L. (2015). Possibility to engage in pedagogical leadership as experienced by finnish newly appointed principals. American Journal of Educational Research, 3(3), 318–329.

- Langman, P. (2009). Why kids kill: Inside the minds of school shooters. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lindfors, E., & Somerkoski, B. (2016). Turvallisuusosaaminen luokanopettajakoulutuksen opetussuunnitelmassa [Safety competence in the curriculum of primany teacher education]. In H.-M. Pakula, E. Kouki, H. Silfverberg, & E. Yli-Paunula (Eds.), Uudistuva ja uusiutuva ainedidaktiikka [Renewing and renewable subject didactics] (pp. 11). Turku: Suomen ainedidaktisen tutkimusseuran julkaisuja. Ainedidaktisia tutkimuksia. Painosalama.

- Lindfors, E., & Somerkoski, B. (2018). Turvallisuuden edistäminen oppimisympäristössä. [Enhancing safety and security in learning environments.]. In P. Granö, M. Hiltunen, & T. Jokela (Eds.), Suhteessa maailmaan. Ympäristöt oppimisen avaajina [In relateion to world. Environments as openers to learning]. (pp. 291–305). Tampere: PunaMusta.

- López, V., Torres-Vallejos, J., Villalobos-Parada, B., Gilreath, T. D., Ascorra, P., Bilbao, M., … Carrasco, C. (2017). School and community factors involved in chilean students’ perception of school safety. Psychology in the Schools, 54(9), 991–1003.

- Mäkelä, A. (2007). Mitä rehtorit todella tekevät, etnografinen tapaustutkimus johtamisesta ja rehtorin tehtävistä peruskoulussa [What the principals really do, an ethnographic case study of leadership and the principal’s tasks in basic education school] (pp. 316). Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä Studies in Education, Psychology and Social Research.

- Martikainen, S. (2016). Development and effect analysis of the asteri consultative auditing process—Safety and security management in educational institutions. Lappeenranta University of Technology. Lappeenrannan teknillinen yliopisto: Yliopistopaino.

- Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (Third ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row Publishers.

- Mearns, K., Whitaker, S. M., & Flin, R. (2003). Safety climate, safety management practices and safety performance in offshore environments. Safety Science, 41(8), 641–680.

- Ministry of Education and Culture. (2013). Turvallisuuden edistäminen oppilaitoksissa. Seurantaryhmän loppuraportti [Enhancing safety and security in educational institutions. Final report of the follow-up group] (pp. 8).

- Ministry of Justice. (2009). Jokelan koulusurmat 7.11.2007. Tutkintalautakunnan raportti [Jokela school shooting on 7 November 2007 – Report of the investigation commission] (pp. 2). Helsinki.

- Ministry of Justice. (2010). Kauhajoen koulusurmat 23.9.2008. Tutkintalautakunnan raportti [Kauhajoki School Shooting on 23 September 2008 – Report of the Investigation Commission] (pp. 11). Helsinki.

- Morrison, G., & Furlong, M. (1994). School violence to school safety: Reframing the issue for school psychologists. School Psychology Review, 23(2), 236–256.

- NBE (National Board of Education). (2013). Rehtorien työnkuvan ja koulutuksen määrittämistä sekä kelpoisuusvaatimusten uudistamista valmistelevan työryhmän raportti [Report of work group preparing determining principals’ job description and reforming qualification requirements]. In Raportit ja selvitykset (pp. 16). Helsinki: Opetushallitus.

- Neal, A., Griffin, M., & Hart, P. (2000). the impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behavior. Safety Science, 34(1), 99–109.

- Nordlöf, H., Wiitavaara, B., Winblad, U., Wijk, K., & Westerling, R. (2015). Safety culture and reasons for risk-taking at a large steel-manufacturing company: Investigating the worker perspective. Safety Science, 73, 126–135.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2017). PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264273856-en.

- Perumean-Chaney, S., & Sutton, L. (2013). Students and perceived school safety: The impact of school security measures. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(4), 570–588.

- Plessis, P. (2014). The principal as instructional leader: Guiding schools to improve instruction. Education as Change, 17(1), 79–92.

- Sahlberg, P. (2015). Finnish lessons 2.0: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press.

- Sergiovanni, T. (2006). The principalship: A reflective practice perspective. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn Bacon.

- Syrjäläinen, E., Jukarainen, P., Värri, V.-M., & Kaupinmäki, S. (2015). Safe school day according to the young. Young, 23(1), 59–75.

- Teperi, A.-M., Lindfors, E., Kurki, A.-L., Somerkoski, B., Ratilainen, H., Tiikkaja, M., … Pajala, R. (2018). Turvallisuuden edistäminen opetusalalla. EduSafe-projektin loppuraportti [Enhancing safety and security in educational context. EduSafe-project’s final report]. Tampere: Suomen Yliopistopaino.

- Timperley, H. (2005). Distributed Leadership: Developing Theory from Practice. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 37(4), 395–420.

- Valonen, K. (2012). Mitä koulusurmat ovat meille opettaneet? [What school shootings have taught us?. In E. Lindfors (Ed.), Kohti turvallisempaa oppilaitosta. Oppilaitosten turvallisuuden ja turvallisuuskasvatuksen tutkimus- ja kehittämishaasteita [Towards a safer educational institution. Research and development challenges of educational institutions security and safety education]. (pp. 180–189). Suomen Painoagentti: Tampereen yliopisto.

- Waitinen, M. (2011). Turvallinen koulu? Helsinkiläisten peruskoulujen turvallisuuskulttuurista ja siihen vaikuttavista tekijöistä [Safe school? Safety culture in primary and secondary schools in Helsinki and the factors affecting to it] (pp. 334). Tutkimuksia. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopisto.

- Zullig, K. J., Ghani, N., Collins, R., & Matthews-Ewald, M. R. (2017). Preliminary development of the student perceptions of school safety officers’ scale. Journal of School Violence, 16(1), 104–118.