ABSTRACT

In response to the persistent indeterminacy – and the salient discontents – surrounding the innovation-centred reporting in the global university-industry collaborations, this study seeks to investigate the reporting of innovation results in Norwegian centres for research-based innovation (SFIs). Based on a large amount of recent public-access documentary evidence (SFI annual reports 2020) which have never been synthesized or systematically analysed before, this study seeks to document and evince the range of innovation initiatives which are reported from SFIs and to raise awareness of the public value innovation propositions that exist within the innovation reporting of these SFIs such as intangible value creation – social and public values of more normative texture, such as internationalization values, transparency, and open access to information, as well as gender balance.

Introduction

In recent decades, the university’s ‘third mission’ – namely, its ability to assume a more innovation-driven, entrepreneurial role and create public value – has gathered vast scholarly attention (Bloch & Bugge, Citation2013; Etzkowitz et al., Citation2019, Citation2021; Goethner & Wyrwich, Citation2020; Hytti, Citation2021; Kaloudis et al., Citation2019; Malecki et al., Citation2017; Scupola & Mergel, Citation2021). However, the exact practices of attaining this third mission, and particularly any innovation-related results, have often been met with scepticism and escape scholarly consensus (Cañibano & Paloma, Citation2009; Mauro et al., Citation2020; Moore, Citation1995; Tyfield, Citation2012). In fact, as much scholarship concedes, the predominantly incremental and often intangible activities that promote innovation create occasional dubiety in the reportability, transferability, and delivery of results, occasionally problematizing the accountability and public value benefits of science and technology innovations (Gittelman, Citation2016; Hessels & van Lente, Citation2008; Hopkins et al., Citation2007; Ribeiro & Shapira, Citation2020). In the wake of this occasional indeterminacy surrounding the reporting of innovation, as well as the growing Norwegian interest in the role of innovation in the university and public policy sector (for a comprehensive review on the topic with active links, see Research Council Norway Citation2018 ; UHR, Citation2022), this study seeks to investigate the reporting of innovation results in Norwegian centres for research-based innovation (henceforth SFIs). Based on a large amount of recent public-access documentary evidence (SFI Harvest, Citation2020) which have never been synthesized or systematically analysed before, this study seeks to document and evince the range of innovation initiatives which are reported from SFIs and to raise awareness of the public value innovation propositions that exist within the innovation reporting of these SFIs.

The importance of this study is twofold. First, it provides the first systematic inquiry of SFIs in the Norwegian national context. Second, by documenting these innovation reporting initiatives, it seeks to offer insight into how the reporting of innovation results is practiced, and serve as an instrument of reflection towards how other international centres can document their innovation initiatives, their innovation results, and cater to a key function of their third mission. This analysis does not seek to directly compare or benchmark the SFIs, neither amongst themselves nor in the national context. Rather, it seeks to provide some qualitative insight on the creativity and diversity in the innovation reporting that these centres showcase, and present the innovation qualities that this kind of innovation reporting involves. Specifically, this analysis focuses on the dimensions that have been bemoaned to go underreported in such centres, namely, any social innovation and public innovation aspects, as well as anything that points not just to the well-documented aspects of innovation outcomes (which are also easier to document and report), but to innovation processes, interdisciplinary initiatives, and collaboration dynamics which are harder to grasp and document (Analytics, Citation2018; Etzkowitz et al., Citation2021; Powell et al., Citation1996). In other words, it seeks to shift the brunt of research attention towards the softer and less tangible – yet equally pressing – parts of innovation and the university-industry collaborations (henceforth UICs). Ultimately, this study aims to surface the innovation impact of SFIs towards creating innovation of public value, openness, and social utility (Moore, Citation1995).

Background

UICs have been studied from a multitude of perspectives, with divergent units of analysis and research methods (Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, Citation2015; Link et al., Citation2015; Meng et al., Citation2019; Roncancio-Marin et al., Citation2022). Their history has been long, conceived and practiced first in the US around the 1920s and spanning across several decades (CitationGertner et al., Citation2011; CitationKaloudis et al., Citation2019; National Research Council (US), Citation1999). Recently, however, the collaborations between university and industry have been intensified worldwide, particularly in the US, Singapore, and Europe (Gertner et al., Citation2011). Within this broader UIC collaboration background, one of the problems which has recently garnered a lot of attention is how to actually measure and report innovation results in the university sector and in university-industry collaborations (Citation2015, Citation2021; Alexander et al., Citation2020; Arvanitis et al., Citation2008; Atta-Owusu et al., Citation2021; Cheng et al., Citation2020; Garcia et al., Citation2020; Perkmann et al., Citation2013; Tseng et al., Citation2020). Reporting these innovations run the entire gamut from intuitive visions of what innovation results looked like to carefully scrutinized analyses. In fact, higher education reporting has so far been practiced through multiple approaches, such as social reporting (Del Sordo et al., Citation2016; Moggi, Citation2019), intellectual capital reporting (Leitner, Citation2004; Nicolo’ et al., Citation2020; Paloma Sánchez et al., Citation2009), sustainability reporting (Gamage & Sciulli, Citation2017; Talebzadehhosseini et al., Citation2021) and more recently integrated reporting (Adams, Citation2018; Brusca et al., Citation2018).

However, the theoretical background or exact practices specific for innovation reporting in universities have been fragmentary and undertheorized. Recently, in a report from the US (Cullum Clark et al., Citation2020, p. 8), innovation impact was conceptualized and quantified in terms of four categories and nine variables: commercialization impact (New patents issued, new licences, licence income), entrepreneurship impact (spinout companies and licences to spinout companies), research impact (paper citations and patent citations) and teaching impact (new STEM doctoral students and new STEM bachelor’s and master’s students). Despite often scholarly discontents with such a narrow innovation outlook (Berkun, Citation2010; Forsberg et al., Citation2019; Sorescu & Schreier, Citation2021), this econometric approach to reporting innovation is similar to the European templates for reporting innovation results, stemming from the OECD and the Oslo Manual. Certainly, the OECD approach (Citation2010) has gained in sophistication and granularity in recent years, including not only innovation indicators and reporting techniques such as economic growth, intangible assets, and patents, but also softer and less readily measurable aspects of innovation, such as (inter)national cooperation, the convergence of scientific fields, interdisciplinary research, and education and training. Nonetheless, aspects of social innovation and public value creation escape the span of such metrics, disallowing fields with lower technology readiness level and not directly commercializing direction (humanities and social sciences) to document the positive innovation externalities that they offer to their regional ecosystems, from both university and industrial directions. A number of qualitative and quantitative studies from a social science perspective (Benneworth & Jongbloed, Citation2010; Benneworth et al., Citation2016; Gulbrandsen & Aanstad, Citation2015) have repeatedly pointed to this gap of research with regard to the impact of innovation from ‘softer’ disciplines and less established – yet consequential – innovation channels. What is more, this line of inquiry has also pointed to the fact that innovation impact spans beyond economic growth or academic credentials, but encapsulates also social innovation and public value creation, the impact of which is less directly measurable and reported in innovation outcomes and results (Ansell et al., Citation2014; Arundel et al., Citation2019; Bloch, Citation2011; Brix, Citation2017; Kelly et al., Citation2002).

In line with these fragmentary theoretical rudiments of innovation reporting, and the ongoing tension between econometric and sociocultural interpretation of innovation, empirical studies point to a latent yet potent division in the innovation activities between formal and informal innovation approaches. On the one hand, systematic, deliberative, radical, and formal change is repeatedly evinced to produce innovation which has lasting and considerable impact (Carlson, Citation2020). On the other hand, recent studies point to the significant innovation impact of ‘bricolage innovation’, which encompasses event-based, loosely coupled, and informal daily practices of problem-solving and ad-hoc adjustments (Bouvier‐patron et al., Citation2021; Fuglsang & Sørensen, Citation2011; Fuglsang, Citation2010; Halme et al., Citation2012; Witell et al., Citation2017).

Thus, the theories around innovation reporting seem to be divided along two broader approaches/views of the role of innovation and its practice of reporting, which span beyond purely innovation studies and are informed by general research trends in social science. The one camp is a more rationalist view, falling under the umbrella of interdependency theories, which emphasize the role of strategic planning, symbolic positioning, and resources (Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, Citation2015; Barringer & Harrison, Citation2000; Geisler, Citation1995). The other camp is interaction theories (Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, Citation2015; Brass et al., Citation2004) and, in recent reinterpretations, behavioural accounts of innovation behaviour (Sunstein, Citation2020), which emphasize that interorganizational cooperation unfolds in a dynamic manner and is relational, contextual, and of bounded rationality (Thaler, Citation2015). Combined views of these theories about innovation are currently lacking (Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, Citation2015) and escape a scholarly consensus as to how these should look. Consequently, in order to allow for a deeper and more empirically driven understanding of innovation, this study was pursued to gain insight into the following research questions:

Questions

What are the innovation themes and salient innovation rationales which underpin the innovation reporting practices of SFIs?

How do these innovation themes relate to the creation of public value innovation and ultimately an open innovation paradigm?

Rationale for this study

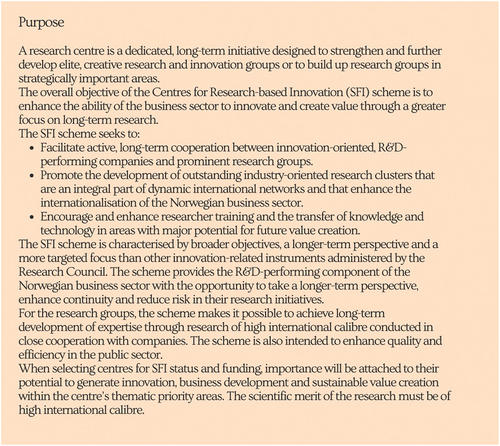

Over the span of several decades (Thomas, Citation1973), annual reports have been repeatedly studied as a source of information for the management and disclosure of human capital (Brennan, Citation2001), strategy disclosure (Santema & van de Rijt, Citation2001), corporate responsibility (Waller & Lanis, Citation2009), stakeholder analysis (Kent & Zunker, Citation2017), but also broader organizational identities (Ditlevsen & Goodman, Citation2012) and mythmaking (David, Citation2001). At the core of such analyses of annual reports commonly inheres the deep predicament of what researchers often term ‘voluntary disclosure’ (Abeywardana & Panditharathna, Citation2016): how much can an organization share openly regarding its strategy, its prospects, but also its challenges? Despite the hefty attention that annual reports have garnered in the industrial sector, their import, impact and citation in the tertiary education sector have been minimal and fragmentary (Coy et al., Citation1993; Guan & Noronha, Citation2013), whereas systematic synthesis or analysis of annual report data from such data sources has been completely absent. This study seeks to study more deeply this dilemma of ‘voluntary disclosure’ in a particular epiphenomenon of academic innovation which has never been previously documented, namely, the annual reports of SFIs. Based on the published objectives of the SFIs (Research Council Norway [RCN] Citation2021a, see of this study), our primary hypothesis and early empirical findings indicated that the annual reports offer a plethora of insights into the potential innovation practices that occur in SFIs and at the crossroads between academia and industry. On the one hand, they do require some hard facts, such as personnel, accounts, and publications, which veer to just pure accounting, without any need for further explanation (Research Council Norway [RCN] 2021, Reporting Template Fourth Generation, see of this study). On the other hand, the annual reports allow for a lot of room for observing how SFIs translate these research activities into innovations, since the amount of detail in disclosure is discretionary on length (no specific page requirements) and bound by the following eight RCN guidelines (Research Council Norway [RCN] Citation2021b): summary, vision/objectives, research plan/strategy, organization (organizational structure, partners, cooperation between the centre’s partners), scientific activities and results, international cooperation, recruitment, and communication and dissemination activities.Footnote1 Consequently, the key objective of this section was to document and evaluate – from an empirical standpoint – how SFIs disclose their innovation results and general innovation strategy within these empirical bounds. Ultimately, such an inquiry will shed more light into the aspects of innovation awareness and the different innovation priorities that undergird these centres.

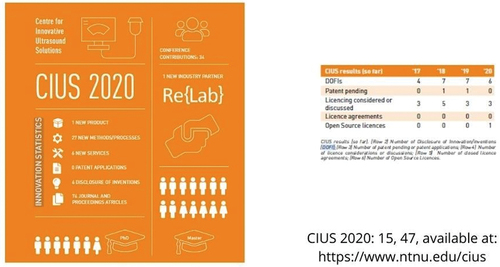

Figure 1. The objectives of the SFI, fourth generation.

Figure 2. Reporting template, fourth generation.

Methods

Design

This study followed the methodological approach of a qualitative design and the research stages of thematic analysis (Nowell et al., Citation2017), combined with the fundamental elements of content analysis (Bowen, Citation2009; Bryman, Citation2016). The initial qualitative method employed, that of content analysis, in the context of document analysis refers to the research process of identifying and collating meaningful sections of the document text, such as innovation results checklists and innovation outcome figures (Bryman Citation2016). However, to achieve further granularity, the study employed thematic analysis, namely, an inductive approach to interpreting, coding, and analysing large qualitative datasets in a concise, rigorous, and consistent manner (Nowell et al. Citation2017). Therefore, in the new analytical lens of thematic analysis, namely, the pattern recognition from the documentary data, the study sought to bring out the emerging themes which constitute the categories of analysis for this kind of unstructured data. Standardly, thematic analysis has six steps (cf. Braun and Clarke, Citation2013, ): (1) familiarize yourself with the data; (2) generate initial codes; (3) search for themes; (4) review themes; (5) define and name themes; and (6) produce the report. The new level of analysis moved in several stages. Initially, given the paucity of studies on annual reporting for innovation in the university sector, the first step of the thematic analysis annual reporting is the deep familiarization with the dataset, namely, the 14 annual reports, and in creative dialogue with the established literature on the topic of annual reporting (McCracken et al., Citation2018). The study then coded with a degree of finer granularity, organizing data often across categories. Next, the researchers searched for themes across categories and keywords. This, as DeSantis and Ugarriza, Citation2000: 362) put it, is in line with the abstract nature of thematic categorization: “A theme is an abstract entity that brings meaning and identity to a recurrent experience and its variant manifestations. As such, a theme captures and unifies the nature or basis of the experience into a meaningful whole.” This study would then proceed, after several iterations, towards identifying four themes (explained in detail on the section of data analysis). Ultimately, the purpose of this study was to establish the meaning of the documents and the contribution to the phenomenon explored, namely, that of innovation reporting strategies.

Table 1. Reportability overview of SFI innovation reporting strategies by thematic category. Source: Author's own configuration.

Sample choice

The selected centres for this study have all been from the SFIs associated with the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (henceforth NTNU). This choice was made based upon two factors. First, NTNU has been involved in the majority of these initiatives, making it a very representative university for the purposes of this analysis. Second, NTNU has some schemes of central governance regarding innovation (Vice-Rector for Innovation, Innovation Leader faculty positions, Innovation Managers), which display a broader strategy, tradition, and systematic coherence regarding the use of innovation. Finally, NTNU has been, to the best of our knowledge, the Norwegian institution, which has the largest inventory of innovation-specific resources centrally (NTNU Discovery, NTNU Student Innovation, NTNU TTO), making it the ideal case study for understanding the broader ecosystem of innovation within the university, which spans across centres.

Data collection and data analysis

This study included 14 Annual Reports from 14 SFIs. In further detail, our data come from the annual reports (Citation2020) of 14 SFIs (SFI ‘Centre for Geophysical Forecasting’, SFI CIRFA – Centre for Integrated Remote Sensing and Forecasting for Arctic Operations, CIUS Centre for Innovation Ultrasound Solutions, SFI NorwAI, SFI iCSI [industrial Catalysis Science and Innovation], SFI Klima 2050, SFI Metal Production, SFI NORCICS, SFI Blues, SFI Harvest, SFI Move, SFI Sirius, SFI Smart Maritime, SFI Subsea Production and Processing) where NTNU is the main partner or a key collaborator. These documents were collected in order to capture the ‘best practices’ of innovation reporting.

Data analysis

The document analysis approach was undertaken in accordance with established methodological phases of thematic analysis (Nowell et al., Citation2017, p. 4), and it combines elements of content analysis with the more established methodology of thematic analysis (Bowen, Citation2009; Bryman, Citation2016; Nowell et al., Citation2017). Content analysis in the context of document analysis refers to the research process of identifying and collating meaningful sections of the document text, such as innovation results checklists and innovation outcome figures. Conversely, thematic analysis was used to examine how patterns within and between the documents as key themes emerge. Such qualitative analysis combines both these analytical approaches, both to reap the benefits of the rich breadth of content contained within these documents, as well as to employ a structured approach to organizing the data around key topics (Nowell et al., Citation2017).

The documents were scrutinized concurrently as data collection progressed in constant juxtaposition with the published objectives of the SFIs by the Norwegian Research Council (see ), as well as in iterative reflection with research questions one and two, in order to gain familiarity with the data. The keyword results signifying innovation were entered into a Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet to enable a systematic examination of the data according to emergent categories. The annual reports were examined in their original format (separate online PDF) and were subsequently merged into a comprehensive large-file PDF (spanning 656 pages, excluding annexes) to allow for the systematic examination of data across SFIs. Throughout the analysis, a log containing raw notes and emergent data was frequently updated. Colour-specific codes were highlighted throughout the documents in order to illustrate pertinent points. The codes were iteratively examined, and emergent patterns were labelled as potential themes for further rumination.

Initially, after two careful readings of the all the reports, a set of terms was used when mining these documents chosen according to frequency and volume of appearance, in order to capture the value creation and innovation parameters which are reported on these documents: *innovat* (301 counts); *value (107 counts); *student (133 counts); *system (617 counts); partners* (581 counts); *process* (491 counts); *impact (126 counts); and *dynamic (223 counts).

After this first set of terms, and a meticulous scrutiny of the associated terms for the issue of how innovation is accounted for and reported in these annual reports, we saw that four themes and patterns of frequency with associated terms largely emerged, analytic dimensions which also correspond with the literature of what constitutes innovation in universities and with the new golden standard of innovation systems, that of the innovation ecosystem (Morris et al., Citation2017; Talmar et al., Citation2020). Theme 1 was economics and funding surrounding innovation (Theme 1). According to that theme, the study sought to capture how often the centres use this theme to showcase their innovation outcomes. This theme, after several iterations, was analysed stemming from keyword searches, such as *funding (56 counts), *Horizon Europe (4 counts), and *pilot (42 counts), in their akin textual context. The second dimension was people and work life (Theme 2), which sought to see how centres account for the development, cultivation, and employability of their human capital within academic and industrial settings. After several iterations, the study used the keywords *PhD (706 counts), *collaboration (159 counts), *employ (33 counts), *synerg* (13 counts), *student (133 counts), * knowledge transfer (4 counts), in their akin textual context, to establish the way in which each SFI establishes its relationship with the employment and industrial place of academic graduates, particularly in non-academic contexts (which is a key SFI objective). The third dimension was networking activity (formal networks and dissemination dynamics, Theme 3). This dimension sought to capture how each SFI showcases its own networking activities and the attraction of human capital. After several iterations, this theme was analysed stemming from keyword searches, such as knowledge transfer (4 counts), * organisation or organization (57 counts), *collaboration (159 counts), *synerg* (13 counts), *network* (69 counts), *conference* (226 counts), *event* (26 counts), event* (26 counts), LinkedIn (16 counts), Twitter (6 counts), in conjunction with their akin textual context. The fourth dimension was commercialization activities (Theme 4), which set out to capture how SFIs relate to the creation of intellectual property rights, licences, and any data on declaration of ideas or declaration of intentions. This dimension stemmed from *intellectual property (5 counts); IPR (9 counts) and *license (12 counts), *open access (1 count), *open source (26 counts) and analysed these notions in their textual context, especially how the commercialization aspect of innovation occurs, as well as the ability to confer open innovation through open licences and open access. Finally, a more emergent and far less established category was an epiphenomenon of public value creation, namely, that of gender considerations, using the keyword gender (4 counts) and seeking for other clues of gender balance in the akin textual context. This list of keywords was informed by the latest published research on UIC and with the scientific literature on innovation ecosystem (Morris et al., Citation2017; Talmar et al., Citation2020), the terms within the SFI funding call itself, SFI’s own midterm evaluation of the scheme, and the independent audit conducted by Analytics (Citation2018). Data saturation was achieved when the scrutiny of all the SFI annual reports and the examination of in-text references ceased to yield new themes or content (Morse, Citation1995). The themes and patterns that supported their emergence were inspected by a wider study team at NTNU, and any divergent perspectives were resolved through group discussion.

Results

In order to systematize our findings, we assorted them first according to the four thematic categories suggested by the literature on the innovation ecosystem landscape (Kaloudis et al., Citation2019), the Analytics (Citation2018), and a grounded analysis of all the textual evidence itself and their correspondence first to the narrower research question one and, subsequently, to our broader research question. To anticipate potential criticism, we have to state that, as it is most often the case in such qualitative analysis of documentary evidence (Nowell et al., Citation2017), the thematic categorization was a heuristic protocol, and the exact categorization upon these themes was impossible, since each annual report presented its own logic and hierarchy of reporting. With the exception of SFI Blues and SFI Move (which seem to be cut from a very similar template), no two reports looked the same. Innovation was a term used repeatedly in passing, used only as an analytical proxy with other more established notions of what constitutes good reporting. Specifically, from the 14 centres, only 6 have a separate section devoted specifically to innovation within their reporting (separate section at the table of contents, see the granularity report table in ). What is more, only two reports (CIUS: Centre for Innovative Ultrasound Solutions, Citation2020: 47) offered its own definitions or future forecasts/projection of what specific innovation activities are expected (e.g. licencing or spin-off creation), making the direct evaluation of innovation practices or innovation strategies virtually impossible. Largely, then, the reporting strategies that these centres use to elucidate their innovation outcomes moves along a wide spectrum between generic, blank statements about innovation in specific work packages, and specific innovation data and statistics, practices which are in direct alignment with international benchmarks of innovation. The offers a general overview of all our findings regarding the reportability of innovation by theme, and the specific emphasis which each SFI places on each theme.

Table 2. SFI innovation disclosure and reporting granularity. Source: Author’s own configuration.

To lend further clarity to the innovation reporting strategies by each SFI and the way in which they construe, state and report their engagement with innovation activities, we hereby offer also on the following table () an overview of the levels of disclosure and granularity of their self-reported innovation strategies.

Findings on innovation theme 1: economics and financing data

One of the most persistent and well-established elements of innovation is the economic performance of a research endeavour, and particularly that of an SFI, which is an established variant of a research centre of excellence. After scrutiny of the annual report data (Citation2020), we have come across two principal trends in the reporting of innovation. The first is about the economic attractiveness of these innovation centres, as established through their ability to track and report on research funding.

From our sample, only about one-third of the centres (35.7%) tracks and reports on external financing from international sources (such as the EU or other global opportunities). This is a finding which aligns also with the independent evaluation from the Damvad report on the lacking efforts of several SFIs to attract or align themselves for European funding. Within this minority of centres, moreover, an additional finding has been that only 60% of these sources seeks for funding opportunities from the Horizon mechanism. This finding is rather understandable given the formal agreement with the RCN and its parameters of formal contractual obligations, yet telling with regard to the general positioning of these centres within the European landscape, which should generally be conducive to more European-targeted resources.

Despite the seemingly low interest in engaging with external funding, the picture of the future and the ability of these centres to kickstart new projects and attract other types of funding are flourishing. Described with terms such as ‘pilot projects’, “associated projects from 2021”, ‘new projects/spin-off projects’, 5 of these centres (37.5%) have reported either completely new or recently started projects that emanate directly from the collaboration with industry or other research and industrial partners. This is an encouraging finding about the ability of networks to come together, collaborate, and generate innovation outputs with broad economic significance. And, ultimately, this attractiveness constitutes an encouraging positive trend in the workings of SFIs and their scheme, which can further stimulate innovation collaboration between university and industry.

Findings on innovation theme 2: people and work life

In the second aspect of our innovation analysis, we have concentrated on the abilities of these research centres to track their human capital, and their success in helping students finding their way to the academic or non-academic job market. In light of growing discontent about the role and function of PhDs in academia (Cyranoski et al., Citation2011; Germain-Alamartine & Moghadam-Saman, Citation2020; Germain-Alamartine et al., Citation2020; Iversen et al., Citation2021; Janger et al., Citation2019; Sauermann & Roach, Citation2016), this is an important indicator for establishing trust in the sector and the transferability of knowledge to society (know-how, know-what, and know-whom). However, the findings from these reports are alarming: only a minority (21.4%) of these centres actively tracks the PhD employability of their candidates, which in itself is a low figure in light of the developments for accountability in the sector. This finding on low reportability on work life transitions is striking in terms of reporting real-life innovation results, given the fact that two-thirds of these tracked people do actually land non-academic employment, which perhaps evinces a missed opportunity for keeping track of the spillovers of knowledge and innovation across work life. Further, in line with the tracking of human capital, one dimension that has received even less attention is the role and activation of MA students in the knowledge transfer in society, as well as the students’ potential job prospects. Only the minority of SFIs still make explicit mention of their MA students’ contributions (42.9%), and from this minority, only half make specific mentions of jobs or internships for MA students. In light of growing emphasis on student entrepreneurship and attractiveness to the job market, this is a striking finding which merits attention and leaves room for growth with regard to integrating the prospects of research-based innovation not only in the academic but also the industrial sector.

Findings on innovation theme 3: networks

Regarding the importance of formal networks and dissemination for the SFIs, the data reveal interesting patterns. On the one hand, all SFIs display lengthy descriptions of their internationalization and networking activities, particularly also with regard to their formal agreements with industry. However, only a fourth of the SFIs in our sample move beyond mere mention of partnerships and actually describe the dynamics of their networking activities (how partners enter or exit, how partnerships grow), as well as their deliberation and decision-making practices. This is an important finding, since such a pattern would reveal not only formal agreements but the very dynamics of these collaborations, and how these dynamics beget new knowledge (Costa et al., Citation2021; Drejer & Jørgensen, Citation2005; Guerrero & Urbano, Citation2021; Hohberger et al., Citation2015; Kaloudis et al., Citation2019; Köhler et al., Citation2022). Moreover, this lack of dynamic descriptions is further revealed in the lacking orientation of knowledge creation in the ecosystem way of thinking, which allows for more spontaneous or serendipitous connections between partners, rather than the a priori assignment of work packages and strict divisions of labour.

A second finding in the data, which calls for our attention, is the modes of dissemination and communication through social media channels (such as Twitter and LinkedIn), which go beyond an SFI´s individual website. The data reveal a lacking interest in engaging with external, well-established platforms (28.6%) beyond a centre’s own webpage only, which could raise, in turn, questions about the scope and international orientation of both recruitment and dissemination of research results. In addition, the detailed – and quantitatively minded – tracking of impression data is rare (20%) in the SFIs under scrutiny, which potentially impedes the broader understanding of networking dynamics and dissemination in these centres.

Finally, as a measure of their abilities to form networks, all SFIs present a very large amount of total bulk of conferences and scientific arrangements they have participated in (amounting to a total of ca. 150), depending on the ways of counting this participation (presentations from the centres, presentations tangentially related to the centres, posters and posters tangentially related), as well as more informal/semi-formal arrangements (such as ‘virtual tech lunches’, ‘common trips’, ‘networking conferences’, ‘working groups’, ‘expert groups’, ‘workshops’, and ‘thematic meetings’).

From this large amount of reported arrangements, and despite the ubiquity of the terms ‘partner’ in every SFI report (a total of 430 mentions), only 5 of these centres (33.3%) describe in detail their modus operandi for how they track in practice their collaboration with their partners (‘invitations to annual meetings’, ‘adjunct professors for the industry partners’, ‘reference groups’, ‘innovation projects’, ‘researchers working with industry partners organizations’) and only one reported perhaps more inconvenient results, such as the departure/withdrawal of some partners (SFI Move). This comparison between arrangements for the public and, conversely, for their more private audience (between partners) can be telling with regard to disclosure of new innovation approaches and outcomes. However, the general state of the SFIs’ ability to report their networking abilities is high and presents on average a lot of detail.

Ideally, we should capture whether these events are purely scientific or include industry and, even more open lay audiences and the general public, with the purpose of achieving dissemination and develop the innovation ecosystem of the SFI. Given the variability of quality of the annual reports, in-depth granular analysis of this specific aspect of the networking activities/events was not possible to fully identify.

Findings on innovation theme 4: commercialization

Finally, with regard to the topic of commercialization, despite the repeated emphasis of the scheme on the clear connection between commercialization and innovation for the generation of new applications, the data reveal a very low interest by SFIs (14.3%) in the tracking of IPR data (patents, licences, and Declarations of Ideas (henceforth DOFIs)'). Moreover, only half of this small minority group makes explicit mention of spin-off ambitions or actions, raising also concerns about the ability of these centres to scale up their efforts and yield revenues for their stakeholders. This is a key finding with regard to how these centres actually report their applied innovation outputs, and the dissonance between the rhetoric of innovation and the actual innovation activities which take place in these centres.

Further, on the front of open access, the general issue of open access and open licence IP has been a cornerstone in the pursuit of innovation, particularly for research institutes and projects which seek to create connections across societal actors. However, the actual explicit mention of the word open access is limited in the SFIs, with the majority (64.3%) making no explicit mention of open access in their annual reports. The centres which do use the open access declarations do so either in the form of open databases (e.g. ‘open source software toolbox’, ‘open drift trajectory model’, ‘open simulation platform initiative’, ‘vessel response tool’), or with strategy declarations (‘open innovation model’). In addition, the more specific pursuit of innovation deliverable, with open licence IP has been even strikingly low in the reports (7.1%), with only one explicit mention of this innovation outcome. This creates some dissonance between the general growing consensus on the importance of pursuing open access in the university sector on all possible fronts and the actual existing practices on the matter. To be sure, our analysis here does not focus on the practice of open access publication, which is only one of the ways that centres pursue openness (and the SFIs do publish via open access with growing rates). Rather, we are talking about other open access tools, platforms, and databases which have direct transferability and operational value for work-life problems and practical challenges. In that respect, the SFI practices still leave much room for growth and open access to all innovation fronts, particularly the free distribution of software or data.

Unexplored innovation dimensions

The final set of data comes from more explorative avenues of innovation, namely, value-based statements on innovation data. Our focus, demanded by the data available at the annual reports, is on gender tracking and the ways in which these centres engage in making explicit gender dynamics in their research efforts. Alarmingly, the majority (64.3%) of these centres makes no mention of gender in their reporting, raising concerns about the implicit, yet persistent, biases that may inhere in the dynamics of these centres. Moreover, some (20%) of this gender reporting is also making brief, rather than detailed, mentions of gender dynamics, showing that there is definitely room for improvement even at SFIs where there already exists awareness of gender imbalance, and its ensuing problems for the public value generation that these SFIs propone. In line with a lot of growing research on implicit bias and its role in gender balance and academic welfare in European academia and transnationally (Gvozdanović & Maes, Citation2018; Menter, Citation2022; Pritlove et al., Citation2019; Timmers et al., Citation2010), gender is an aspect that should be carefully scrutinized and accounted for in the fostering of an innovation culture among SFIs. In that respect, this aspect of innovation leaves much room for growth and future development.

Discussion

The data collected from this wide host of SFIs revealed a large degree of variety in the reporting priorities with regard to the presentation of their most salient innovation themes and underpinning rationales (research question one), and particularly with regard to less tangible aspects of innovation which can engender public value, impact and transferability of innovations (research question two).

Based on the current data analysis and the four innovation themes present in the reporting strategies, the SFIs do display variability in their reporting of the innovation, and their ability to signal their innovation efforts, in terms of both innovation outcomes but also innovation processes and the underpinning dynamics that innovation is constructed upon. If we were to present our findings by means of an innovation spectrum, at the lower end we may put a more traditional view of academic reporting with emphasis on scientific reporting and research outcomes. This kind of reporting, captured by publication metrics and the emphasis on publication impact, places prime value in the ability of a research group to report pathbreaking research and achieve visibility within a field or across research fields. To be sure, this is a key function of an SFI, which is clearly mandated from the NFR to ‘further develop elite research and innovation groups’.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, we find the prospect of innovation reporting, which places emphasis primarily on the innovation outcomes per se and considers research as the springboard and means of innovation, not the end in itself (see, e.g. the findings from innovation theme four on commercialization and the findings on of this study, as showcased e.g. by CIUS Citation2020 and SUBPRO Citation2020). In this kind of reporting, the prime emphasis is put on how innovation stems out of a centre’s research effort, and how these research efforts have direct applicability in the end user’s, industrial or business partners’, and the general public’s everyday practices and working routines. In this fashion, innovation reporting turns the traditional dynamic of academic work on its head and prioritizes real-life applications and hands-on transferability as the cornerstone of innovation, seeking to combine the drive of curiosity with that of practical utility and measurable value creation. More strikingly, this kind of value creation does not simply encapsulate monetary value. Rather, it captures also more intangible value creation – social and public values of more normative texture, such as internationalization values, transparency, and open access to information, as well as gender balance considerations and general reporting of qualitative stories around the very formation of innovation activities (see, e.g. CIUS Citation2020 and iCSI Citation2020) As an example of excellence, elucidates an exceptional practice of data-based reporting on benchmarking innovation.

As a baseline note, these research findings do evince both a wide spectrum of innovation results, which are conducive to public value and a lot of ongoing valuable work on the creation and documentation of innovation efforts at SFIs. Some of these aspects of innovation are clearly present in the reports (especially with regard to the dissemination and networking activities around innovation), and some centres concentrate a lot of efforts towards reporting their innovations in a way that is detail-oriented, process transparent, and potentially transferable to other activities (with most salient example being the SFI CIUS, an established centre in documenting and elevating the discourse of innovation). These salient innovation findings on less tangible aspects of innovation point to the growing concept of collaborative innovation (Bason, Citation2018; Hipp et al., Citation2010; Kaloudis et al., Citation2019), which contributes to this direction of social innovation and the creation of public value, since it understands innovation both as the product of broader synergies between public and private interests and founded on a long-term, iterative innovation perspective.

However, inherent tensions are not absent from these innovation reporting efforts. While there is some occasional significant reporting sophistication on several innovation processes related to innovation around declaration of new ideas, new inventions, and new network dynamics, the preponderance of innovation reporting is still devoted to product innovations, academic publications, and commercialization outcomes, which are directly observable, quantifiable, and directly related to new public management outlooks in higher education, with added emphasis on efficiency, effectiveness, tight output control, and the increased role of the private sector (Bleiklie, Citation1998; Ferlie et al., Citation2008; Gunter et al., Citation2016). This reporting outlook may arguably create some tension between the creation of public value in SFIs and the competitive nature of value priorities in SFI reporting efforts. After all, as a large host of research has repeatedly argued (for a useful summary, see Mazzucato, Citation2018) innovation is not a neutral or value-free concept. Rather innovation and its propositional value can go either way, either in an exclusive direction or towards an inclusive direction, construing its target audience as either clients/users or as reflective citizens. In light of their directionality, then, the results of innovation, namely, the growth that emanates from any given innovations, could be either from an individualist/self-regarding prism of profit and path-dependencies (establishing results through publications and IPR) or can be construed through a collective prism, placing weight on duty, social, and, ultimately, altruistic public value.

Undeniably, this tension in innovation reporting and the pursuit is not solely akin to individual SFI centres. Rather, it has been arguably endemic to the broader design of the SFI scheme, which has been criticized for not taking into account enough public, social, and end-user value creation in its foundational apparatus, SFI action agenda, and reporting requirements (Analytics, Citation2018). Seen from a broader educational reform policy, then, universities and SFIs are underpinned by a peculiar innovation tension: they are both the sites of innovation and the motors of innovation, contributing simultaneously to both the provision and extraction of public value, thusly creating a long-lasting contradiction in the function of the UICs (Castells et al., Citation1993, Citation2001). In that respect, there is much work remaining for integrating and streamlining these innovation priorities and value preferences within the framework of a broader innovation reporting system for public value (as per research question two). Such integration would raise further awareness of the public value of these innovations and their societal benefit and impact and allow for this innovation awareness and its public value to be accessible, transparent, and interpretable across audiences with regard to the innovation themes of not only economics and external financing data (Theme 1) but also in terms of less directly tangible factors, such as people and work life (see, e.g. the great examples of high reportability from iCSI Citation2020) networks (with the excellent example of NorwAI Citation2020) and commercialization (with, e.g. CIUS Citation2020). Such excellent examples of innovation themes do exist in Norway – and should be made more salient and visible across all centres.

In fact, upon transferable insight and process transparency, innovation results would be more comprehensive for all centres and for all future generations of SFIs which aspire to creating public value and an open innovation paradigm. The tradeoff of course could be, initially at least, more reporting and an initial information overload. However, with a bit more reporting at the front end, the ensuing reporting for innovation could be simpler and more useful – becoming a process of not pure accounting, but introspection and reflection, as well as surfacing new, unforeseen connections between innovation platforms. To be sure, the lurking danger here is that of what has been routinely entitled as ‘mission overload’ (Jongbloed et al., Citation2008), or, in the discourse of cognitive scientists, ‘infobesity’: the constant, if pointless, quest for instant gratification through information-based dopamine kicks (Van der Stigchel, Citation2019). However, after gaining deeper insight into existing good practices of innovation reporting, individual innovation results could avoid the pitfalls of isolationism and attain a connectionist approach in innovation reporting. Such a connectionist approach moves past abstract, formalistic reports of innovation and, rather, accentuates the potential connections across innovation ecosystems and public value/social innovation aspects, elevating the prospects of general innovation literacy across knowledge ecosystems.

To summarize the issue, then, with a bird’s-eye view: like any magisterial grand narrative, innovation reporting is continuously caught in this tension between constant creation and, simultaneously, the finality of results. This is an understandable and well-documented search for closure and results amid environments of uncertainty (like that of innovation pursuit) that is deeply seated within our neural circuitry of our brains (Chang et al., Citation2020; Leone et al., Citation1999; Schumpe et al., Citation2017 ; Schulte Citation2019). However, innovation results could resist this monolithic pursuit of closure and the low tolerance of uncertainty and risk-taking that leads to an increased risk aversion mentality and the discounting of delayed – yet more valuable – rewards (Schumpe et al., Citation2017). Rather, a deeper understanding of innovation results for this host of excellent of SFIs should be seen through the prism of a more holistic approach of both salient innovation themes and their contribution to open innovation paradigms, which is principally informed by base-rate awareness, analytic decision-making, and empirical reasoning (Barbey & Sloman, Citation2007; De Neys et al., Citation2008; Kahneman et al., Citation2021). This empirical approach – which is informed by counterfactual reasoning, the inclusion of rival perspectives, transferability of insights, detail-orientation, process transparency, and social value awareness which several existing SFIs already display (with prime example that of CIUS Citation2020) – may in the final analysis shift the locus of innovation from isolated research and commercialization results towards public value, altruistic, and a more open innovation paradigm that can follow and ameliorate the future practices of SFI reporting.

Limitations and prospects for further research

This study presents certain limitations, both in terms of sampling (the timespan of the sample is only for Citation2020) and in terms of inferential power for other national contexts. Moreover, the fact that some centres are at different stages of their establishment and operations (the initial establishment phase reduces the ability to report innovation outcomes in an extensive fashion) does not allow any easy comparisons across centres and priorities, as well as inferences about their innovation capacity and absorptive capacity. Finally, the non-reactive nature of document analysis disallows for real-life and dynamic inferences and should be ideally triangulated with other qualitative data sources (e.g. interviews and surveys), in order to create a more dynamic and real-time overview of innovation ecosystems.

By means of overcoming these study limitations, one of the most promising venues for understanding better the notion of innovation outcomes would be to explore longitudinally the reports of SFIs in Norway from their inception in 2005. Such an outlook of innovation would allow for the detection of patterns from a longer-term viewpoint and allow for the formation of more empirically driven analysis. Moreover, such a longitudinal analysis could also benefit from drawing from comparative international sources, such as Nordic or other OECD-zone universities and research centres to determine the degree of variability and detail in the act of innovation reporting in the past decades. Additionally, future research could seek to also capture the degrees of freedom in the automation of such innovation results, as contrasted to fuzzy, underreported, or innovation data which are hard to access (either due to proprietary causes or due to sociocultural norms, lack of reporting manpower, etc.). In other words, data feasibility studies could greatly ameliorate the overall research status of the innovation field, lending greater clarity about the reporting challenges and barriers which currently confront the act of innovation reporting, as well as the opportunities for automation or comparability. Finally, by the agglomeration of such international reporting data, future research could illustrate the impact of innovation results not only for their akin stakeholders but also for their broader social and public innovation purposes, illustrating more vividly the interplay of the university’s third mission with its other primary functions, namely, that of research and teaching.

Recommendations for innovation reporting

One of the first recommendations we would like to make regarding the reportability of innovation in research centres is a question of method for measuring innovation performance, namely, the process of identifying key performance indicators (KPIs) and normalization factors which may benchmark the innovation work in specific areas. To be sure, this effort towards standardization is not to be confused with static oversimplification and reductionism of the innovation process as linear. Rather, it should be an attempt to enter and understand the iterative process of interplay between factors of quantification and, conversely, it should nuance and trigger a deeper quantitative and qualitative exploration of innovation performance.

Along this line of thought, a second recommendation would be to offer a renewed and commonly agreed description of the data definition for each innovation endeavour, its significance, potential for automatic generation of data, its reliability, data quality standards, and its normalization standards. In that way, each innovation activity could be more critically re-examined to gain further depth and replicability across centres and, eventually, institutions.

Third, one of the prospects for the amelioration of innovation reportability, would be to further develop and deploy existing data sources from centralized sources (administration/economy/HR and university TTOs). In that way, each data source of innovation performance would gradually gain lower costs, greater transparency, and ease of processing, for current and future data collection. In parallel, a recommendation for the development of data collection would be to assign innovation advisors/data scientists to curate the local collection of this kind of innovation data, both with regard to the range and the detail of resource-intensive datasets (such as e.g. human capital monitoring and networking activities). This kind of advisor/data scientist would report centrally to an institution and allow also potentially for the surfacing of further connections between datasets and their innovation spillovers.

As a further corollary of this data set curation, a potential role for ameliorating the innovation reportability would be to strengthen and consolidate existing data sources through information campaigning and explicit information requirements from all faculty and staff members. A focus on information collection such as the registering additional professional activities (e.g. additional appointments in the industrial sector), the establishment of collaboration agreements of master’s students with industry, the establishment of registered collaborations for MA thesis writing, as well as the data collection about the labour market placement of PhD students are all potential candidates for consolidating data collection and vital strategic information flow for any research centre. Moreover, the development of a newly minted central data collection solutions could significantly expedite the processing and communication of such innovation data. In that way, any university centre could establish a more advanced and reflective way of measuring and managing its innovation performance, in a proactive fashion.

Last, but not least, the eventual identification of emergent innovation indicators for notions that progressively gain prominence in the landscape of innovation in higher education, such as interdisciplinarity or sustainability, could present promising avenues for the establishment of further pioneering work with innovation.

Conclusions

The study of innovation reporting strategies leaves the reader with some broader and lasting lessons about how to improve innovation reportability across universities in the future. One of the key conclusions that we can draw from the analysis of such centres of innovation excellence is that, as a general trend, the volume and scope of reportability, the granularity of reportability and the readiness of disclosure of public value benefits vary significantly across centres, with the average (base rate) of innovation reportability leaving great room for growth. For example, some centres such as CIUS have reached a very high level of reportability, presenting their readers with precise and granular innovation statistics (see of this study). On the other hand, the majority of innovation centres present very little by means of innovation statistics, and in particular with regard to details of commercialization and economics of innovation that occur in each centre. Moreover, the dimensions of human capital management, particularly with regard to the labour market placement and market attractiveness of PhD and MA students, are not particularly salient in the reportability of these findings. The same finding goes with regard to networking, where the attention to public events, as well as direct participation of partners in meetings, is not met with meticulous reporting, making it hard to present clearly whether several of these networking activities are just scientific conferences or events, and whether these events have any bearing for a business partner audience or the general public. This is an elemental dimension for the communication potential of a research and innovation agenda, and the general transferability and translatability of a centre´s innovation findings to its end users and, by extension, to the general public as clear and identifiable innovation statistics. The general impression of innovation at the particular centres under scrutiny is positive and definitely merits our attention. The publication rates, the collaboration with industrial partners, as well as the overall ability to communicate across sectors and audiences, as well as to generate measurable value, are solid and should not be taken for granted. However, the reporting of innovation leaves often much room for growth. First and foremost, as engines of growth, such research centres for innovation could allow for more reporting and general public information on the additionalities they create, namely, on the new EU/RCN or pilot projects that emanate directly from their establishment. This kind of reporting of the positive innovation externalities of a centre would create a much better sense of accountability and trust in the innovation work that occurs, and the innovation spillovers that such work can generate.

To further corroborate this point, the fourth innovation theme of our study, the aspect of commercialization and its measurement or effects on the innovation performance of such centres is still not well reported, and this is something that is repeatedly bemoaned across international scrutiny of innovation reportability (for an overview, see Talmar et al., Citation2020). Consequently, the establishment of a baseline of key performance indicators (KPIs) for commercialization, particularly with regard to declaration of new ideas (DOFIs), pending or approved patents, as well as spin-off companies is a key prospect for future reporting of innovation efforts, which would create healthy benchmarks to strive towards and reflect upon innovation efforts. A third dimension to allow for future improvement of innovation efforts is the more detailed reporting of activities that yield open access (data, codes, digital platforms, software programs, methods and open-source licences). Open access is a critical dimension, both in terms of adding value to the end users of an innovation, but also – by means of response to our two research questions – for the broader public and the empirical establishment of clearly identifiable innovation themes and ensuing public value. This kind of open access knowledge creates major benefits for translating scientific knowledge into practice, making research and international environments more globally competitive and elevating the reach of knowledge beyond the academic walls.

An additional dimension for the general added reflexivity of innovation reporting is the tracking and management of human capital, and the way centres engage with the labour market placement of their masters and PhD graduates, to secure the strategic placement of fresh talent and new skills in both industry and academia. Given the growing dissatisfaction with the market placement of PhDs and the frequent misalignment of skills and work tasks (Cyranoski et al., Citation2011; Germain-Alamartine & Moghadam-Saman, Citation2020; Germain-Alamartine et al., Citation2020; Iversen et al., Citation2021; Janger et al., Citation2019; Sauermann & Roach, Citation2016), the careful monitoring of the labour market placement of qualified human capital could mean a great deal both for the credibility of the university as a site of growth, but also for the ability of industry to absorb human capital and put cutting-edge knowledge into practical, occasionally life-altering applications. This is particularly true of a more neglected aspect of the graduate population, namely, the master’s student graduates, which is a body of the university’s human capital which has not been carefully monitored in terms of career development. What is more, an aspect of innovation reportability which leaves room for development is that of the reportability of emergent values, such as gender balance, equal opportunity, and process transparency in the recruitment and practical execution of innovation efforts. The reportability of such considerations and less directly tangible aspects of value creation carry a great deal of weight not only on the results of innovation per se but also on the general reputational cascades of a university’s ecosystem of values. Underscoring the prominence of this dimension can allow for greater trust and authority in the university’s role in society, and its ability to put forth examples worth emulating and aspiring towards.

Finally, a common discontent also from the published research is the lack of actionable and domain-specific key performance indicators (KPIs) which can clearly orient researchers or centres about their innovation presence. To be sure, we do not advocate for a linear model of technology readiness level or catch-all terms. However, some preliminary consensus on what constitutes reliable performance indicators are still a desideratum across innovation centres, especially at larger scales of collaboration, which entail more interaction volume – and therefore more complexity. Secondly, the annual and general reporting of each centre does not seem to entail any insight into their specific innovation models. The reporting so far allows a great sense of outcome transparency, but little on process transparency, therefore hindering the understanding of the dynamics that underpin deliberation and decisions. Consequently, allowing for some reporting of inner constructive disagreements or fruitful arguments could greatly enhance the process of innovation itself, which is well established as the result of the contention with different perspectives. In that area, some input from alumni or from graduate networks could be useful. In that line of thought, the establishment of active dialogue with best practices with other centres could greatly advance the reporting practices for the mutual benefits of such research initiatives and for any funding scheme which seeks to boost innovation and the university’s third mission as a whole. This kind of reporting across the spectrum of both monetary/commercial and normative values lends innovation reporting a greater sense of depth which spans beyond commercial trends, fads, or financial gains, to incorporate public values with a long-term and direct social purpose. Ultimately, this reporting can allow for innovation to play a key role in the transformation of a university into an engine of growth, a growth that is both value-centred, long term, open, and – in the final analysis – sustainable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

References

- Abeywardana, N. L. E., & Panditharathna, K. M. (2016). The extent and determinants of voluntary disclosures in annual reports: Evidence from banking and finance companies in Sri Lanka. Accounting and Finance Research, 5(4), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.5430/afr.v5n4p147

- Adams, C. A. (2018). Debate: Integrated reporting and accounting for sustainable development across generations by universities. Public Money & Management, 38(5), 332–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2018.1477580

- Alexander, A., Martin, D. P., Manolchev, C., & Miller, K. (2020). University–industry collaboration: Using meta-rules to overcome barriers to knowledge transfer. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 45(2), 371–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9685-1

- Analytics, D. (2018). Evaluation of the scheme for research-based innovation (SFI). https://www.forskningsradet.no/siteassets/publikasjoner/2018/evaluation_of_the_scheme_for_research-based_innovation_sfi.pdf

- Ankrah, S., & Al-Tabbaa, O. (2015). Universities–industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(3), 387–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2015.02.003

- Ansell, C., & Torfing, J. (2014). Collaboration and design: New tools for public innovation. In C. Ansell & J. Torfing (Eds.), Public innovation through collaboration and design (pp. 19–36). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203795958-9

- Arundel, A., Bloch, C., & Ferguson, B. (2019). Advancing innovation in the public sector: Aligning innovation measurement with policy goals. Research Policy, 48(3), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.12.001

- Arvanitis, S., Kubli, U., & Woerter, M. (2008). University-industry knowledge and technology transfer in Switzerland: What university scientists think about co-operation with private enterprises. Research Policy, 37(10), 1865–1883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.07.005

- Atta-Owusu, K., Fitjar, R. D., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2021). What drives university-industry collaboration? Research excellence or firm collaboration strategy? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121084. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040162521005175 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121084

- Barbey, A. K., & Sloman, S. A. (2007). Base-rate respect: From ecological rationality to dual processes. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30(3), 241–254. discussion 255–297. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X07001653

- Barringer, B. R., & Harrison, J. S. (2000). Walking a tightrope: Creating value through interorganizational relationships. Journal of Management, 26(3), 367–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600302

- Bason, C. (2018). Leading public sector innovation: Co-creating for a better society (2nd ed.). Policy Press.

- Benneworth, P., Gulbrandsen, M., & Hazelkorn, E. (2016). Promoting innovation, and assessing impact and value. The impact and future of arts and humanities research (pp. 149–184). https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-40899-0_6

- Benneworth, P., & Jongbloed, B. W. (2010). Who matters to universities? A stakeholder perspective on humanities, arts and social sciences valorisation. Higher Education, 59(5), 567–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9265-2

- Berkun, S. (2010). The myths of innovation. O’Reilly Media, Inc.

- Bleiklie, I. (1998). Justifying the evaluative state: New public management ideals in higher education. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 4(2), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.1998.12022016

- Bloch, C. (2011). Measuring public innovation in the Nordic countries (MEPIN). from https://www.divaportal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:707193

- Bloch, C., & Bugge, M. M. (2013). Public sector innovation –from theory to measurement. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 27, 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2013.06.008

- Bouvier‐patron, P. (2021). Bricolage – from improvisation to innovation: The key role of “bricolage. In D. Uzunidis, F. Kasmi, & L. Adatto (Eds.), Innovation economics, engineering and management handbook: Vol. 2. Special themes (pp. 67–73). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119832522.ch6

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Brass, D. J., Galaskiewicz, J., Greve, H. R., & Tsai, W. (2004). Taking stock of networks and organizations: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 47(6), 795–817. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159624

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

- Brennan, N. (2001). Reporting intellectual capital in annual reports: Evidence from Ireland. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 14(4), 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570110403443

- Brix, J. (2017). Exploring knowledge creation processes as a source of organizational learning: A longitudinal case study of a public innovation project. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 33(2), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2017.05.001

- Brusca, I., Labrador, M., & Larran, M. (2018). The challenge of sustainability and integrated reporting at universities: A case study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 188, 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.292

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Cañibano, L., & Paloma, S. M. (2009). Intangibles in universities: Current challenges for measuring and reporting. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 13(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/14013380910968610

- Carlson, C. R. (2020, November 1). Innovation for impact. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/11/innovation-for-impact

- Castells, M. (1993). The university system: Engine of development in the new world economy. In A. Ransom, S. M. Khoon, & V. Selvratnam (Eds.), Improving higher education in developing countries (pp. 65–80). World Bank.

- Castells, M. (2001). Universities as dynamic systems of contradictory functions. In J. Muller, N. Cloete, & S. Badat (Eds.), Challenges of globalisation: South African debates with Manuel Castells (pp. 206–223). Maskew Miller Longman.

- Chang, A. Y. C., Biehl, M., Yu, Y., & Kanai, R. (2020). Information closure theory of consciousness. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1504. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01504

- Cheng, H., Zhang, Z., Huang, Q., & Liao, Z. (2020). The effect of university–industry collaboration policy on universities’ knowledge innovation and achievements transformation: Based on innovation chain. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 45(2), 522–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9653-9

- CIRFA – Centre for Integrated Remote Sensing and Forecasting for Arctic Operations. (2020). Annual report. https://cirfa.uit.no/wpcontent/uploads/2021/06/CIRFA_arsrapport_2020.pdf

- CIUS: Centre for Innovative Ultrasound Solutions. (2020). Annual report. https://www.ntnu.edu/documents/1262947227/1268580566/CIUS_Annual_Report_2020_web_small.p df/0ef21000-36ba-45a5-dc21-afd0b9f2c1be?t=1616786836933

- Costa, J., Neves, A. R., & Reis, J. (2021). Two sides of the same coin: University-industry collaboration and open innovation as enhancers of firm performance. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 13(7), 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073866

- Coy, D., Tower, G., & Dixon, K. (1993). Quantifying the quality of tertiary education annual reports. Accounting & Finance, 33(2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-629X.1993.tb00323.x

- Cullum Clark, J. H., Murri, K., Nijhawan, V., Blackwell, C. T., & Ingram, S. (2020). The Innovation impact of U.S. universities: Rankings and policy conclusions, from https://hdl.handle.net/2144/41842

- Cyranoski, D., Gilbert, N., Ledford, H., Nayar, A., & Yahia, M. (2011). Education: The PhD factory. Nature News, 472(7343), 276–279. https://doi.org/10.1038/472276a

- David, C. (2001). Mythmaking in annual reports. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 15(2), 195–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/105065190101500203

- Del Sordo, C., Farneti, F., Guthrie, J., Pazzi, S., & Siboni, B. (2016). Social reports in Italian universities: Disclosures and preparers’ perspective. Meditari Accountancy Research, 24(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-09-2014-0054

- De Neys, W., Vartanian, O., & Goel, V. (2008). Smarter than we think: When our brains detect that we are biased. Psychological Science, 19(5), 483–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14679280.2008.02113.x

- DeSantis, L., & Ugarriza, D. (2000). The concept of theme as used in qualitative nursing research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 22(3), 351–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/019394590002200308

- Ditlevsen, M., & Goodman, M. B. (2012). Revealing corporate identities in annual reports. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 17(3), 379–403. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563281211253593

- Drejer, I., & Jørgensen, B. H. (2005). The dynamic creation of knowledge: Analysing public–private collaborations. Technovation, 25(2), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(03)00075-0

- Etzkowitz, H., Dzisah, J., & Clouser, M. (2021). Shaping the entrepreneurial university: Two experiments and a proposal for innovation in higher education. Industry and Higher Education, 36(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422221993421

- Etzkowitz, H., Germain-Alamartine, E., Keel, J., Kumar, C., Smith, K. N., & Albats, E. (2019). Entrepreneurial university dynamics: Structured ambivalence, relative deprivation and institution-formation in the Stanford innovation system. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.10.019

- Ferlie, E., Musselin, C., & Andresani, G. (2008). The steering of higher education systems: A public management perspective. Higher Education, 56(3), 325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9125-5

- Forsberg, E. -M. (2019). Responsible research and innovation in the broader innovation system: Reflections on responsibility in standardisation, assessment and patenting practices. In R. von Schomberg & J. Hankins (Eds.), International handbook on responsible innovation (pp. 150–166). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784718862.00017

- Fuglsang, L. (2010). Bricolage and invisible innovation in public service innovation. Journal of Innovation Economics Management, n° 5(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.3917/jie.005.0067

- Fuglsang, L., & Sørensen, F. (2011). The balance between bricolage and innovation: Management dilemmas in sustainable public innovation. The Service Industries Journal, 31(4), 581–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2010.504302

- Gamage, P., & Sciulli, N. (2017). Sustainability reporting by Australian universities. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 76(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12215

- Garcia, R., Araújo, V., Mascarini, S., Santos, E. G., & Costa, A. R. (2020). How long-term university-industry collaboration shapes the academic productivity of research groups. Innovations: Organization and Management, 22(1), 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2019.1632711

- Geisler, E. (1995). Industry–university technology cooperation: A theory of inter-organizational relationships. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 7(2), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537329508524205

- Germain-Alamartine, E., Ahoba-Sam, R., Moghadam-Saman, S., & Evers, G. (2020). Doctoral graduates’ transition to industry: Networks as a mechanism? Cases from Norway, Sweden and the UK. Studies in Higher Education, 46(12), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1754783

- Germain-Alamartine, E., & Moghadam-Saman, S. (2020). Aligning doctoral education with local industrial employers’ needs: A comparative case study. European Planning Studies, 28(2), 234–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1637401

- Gertner, D., Roberts, J., & Charles, D. (2011). University‐industry collaboration: A CoPs approach to KTPs. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(4), 625–647. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271111151992

- Gittelman, M. (2016). The revolution re-visited: Clinical and genetics research paradigms and the productivity paradox in drug discovery. Research Policy, 45(8), 1570–1585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.01.007

- Goethner, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2020). Cross-faculty proximity and academic entrepreneurship: The role of business schools. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 45(4), 1016–1062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09725-0

- Guan, J., & Noronha, C. (2013). Corporate social responsibility reporting research in the Chinese academia: A critical review. Social Responsibility, Journalism, Law, Medicine, 9(1), 33–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/17471111311307804

- Guerrero, M., & Urbano, D. (2021). Looking inside the determinants and the effects of entrepreneurial innovation projects in an emerging economy. Industry and Innovation, 28(3), 365–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2020.1753021

- Gulbrandsen, M., & Aanstad, S. (2015). Is innovation a useful concept for arts and humanities research? Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 14(1), 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022214533890

- Gunter, H. M., Grimaldi, E., Hall, D., & Serpieri, R. (Eds.). (2016). New public management and the reform of education: European lessons for policy and practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315735245

- Gvozdanović, J., & Maes, K. (2018). Implicit bias in academia: A challenge to the meritocratic principle and to women’s careers—and what to do about it (Advice Paper No. 23). League of European Research Universities (LERU). https://www.leru.org/files/LERU-PPT_Bias-paper_Jadranka_Gvozdanovic_January_19_18.pdf

- Halme, M., Lindeman, S., & Linna, P. (2012). Innovation for inclusive business: Intrapreneurial bricolage in multinational corporations. Journal of Management Studies, 49(4), 743–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01045.x