Abstract

Early computer games of the ‘Eastern bloc’ have been studied as important artefacts of early digital media, but their significance is usually limited to the historical context. In this article, I present a case study of the first popular computer game made in Belarus, which political relevance has persisted through over two decades. In order to achieve multi-sided description and interpretation of the case, three methods are combined: semantic analysis of the game itself, a survey of its typical players, and comparison to similar cases in Czechoslovakia, Poland and Russia. The proposed explanation of the game’s origins highlights the importance of ‘shared commons’, relics of socialism reused for a variety of purposes during the brief period of ideological liberalism. This allows situating this particular form of subversive media in the process of transition from socialism to capitalism in Eastern Europe – the process that has never been concluded in contemporary Belarus, contributing to the totalitarian situation of 2020–2021.

Introducing the Case: The Political Game That Outlived Its Time

MENSKBand, or simply MENSK, is a computer game developed for the MS-DOS operational system in 1998 in Minsk. It is a typical ‘homebrew’ game that adheres to all but one criteria proposed by Melanie Swalwell in her study of early domestic computing and games (Swalwell Citation2021). According to Swalwell, homebrew games are the games with experimental ethics made in domestic space by amateur programmers, most often sole creators and distributed locally, usually without support from a commercial publisher (Swalwell Citation2021, 3). ‘Experimental ethics’ means that such games were often used as vessels for personal and artistic expression and sometimes for political statements (see also Švelch Citation2013). The latter is also the case of MENSKBand, the archenemy of which is easily identified as the bloodthirsty dictator Alexander Lukashenko, who came to power at the first democratic president elections in 1994 and had been gradually establishing the authoritarian and, after his sixths elections in August 2020, totalitarian style of ruling the country. The only difference from a typical ‘homebrew’ game is that MENSKBand had three individual creators, according to its start screen, and we will return to this particular feature later.

In the context of game histories, the described case fits into a smaller but distinct genus of games that represent, sometimes procedurally, instalment of democracy in an oppressed country, best described in the research of early political games in Czechoslovakia (Švelch Citation2013). Unfortunately, in the case of Belarus, this message remains increasingly important to this day. Moreover, Jaroslav Švelch once again highlights the importance of studying early political games by referring to the Belarusian situation: ‘As we are writing in 2020, protesters are being beaten up in Belarus in a way that bears eerie resemblance to the events in Czechoslovakia more than thirty years ago’ (Švelch and Kouba Citation2020). In short, computer hobbyists would use their newly discovered electronic medium to say very similar things with a digital game in 1989 in Prague and in 1998 in Minsk. Let us explore why, and how this lesson could be applied to the 2020s.

The research strategy that is applied here is a case study. In terms of social sciences, a case is ‘a sample of one’: a particular phenomenon, or, as it can be in the case of political studies, a particular person, who is studied by a particular method or a combination thereof to create a holistic, meaningful, and realistic characterisation with exploratory and explanatory potential. In the broadest sense, research material for a case study is ‘the basic descriptive material an observer has assembled by whatever means available’ (Mitchell Citation1983, 191), although academic rigour and research ethics, of course, should not be compromised. Still, a case is often constituted from a variety of observations and measurements, and the findings are not immediately generalizable to other cases, even if these cases are similar. As J. Clyde Mitchell argues, ‘the process of inference from case studies is only logical or causal and cannot be statistical’ (Mitchell Citation1983, 200).

The case of MENSKBand is typical and atypical at the same time. It is typical in that sense that this game shares most of its features with other Eastern European political games. However, the game remains an atypical case in Belarus: there have been no other video games primarily in the Belarusian language, relying on the living Belarusian culture, which would achieve any remarkable popularity since MENSKBand in 1999. We first address the unique content of the game in its semantic analysis, and then proceed to defend its typicality by historical comparison. Synthesis of the typical and the unique takes place in the small scale study of the game’s audience, which may explain why no more such games were made. In the broader context, this case sheds more light on the role of ‘shared commons’ and other forms of state support in fostering young creative industries such as the game industry.

Game Analysis: MENSKBand as a ‘Roquelike’

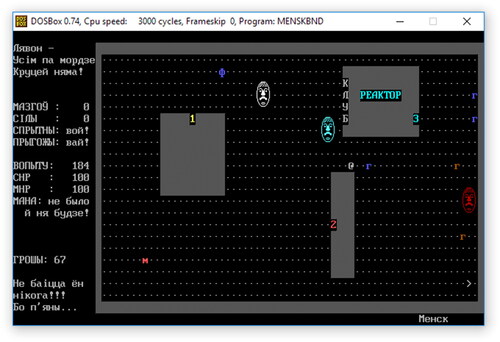

Every early computer game is a unique combination of influences and circumstances, and MENSKBand is also special in many ways. Technically, MENSKBand is a mod of an open source dungeon exploration game Angband (Cutler and Astrand Citation1990), a staple for creative modification in the rogue-like genre based on Tolkienesque lore. The graphic interface of the game is simply a matrix of ASCII characters that mostly refer to the well-established conventions of the genre (). Due to this, most of the game’s appeal is left to the player’s imagination. Game texts are virtually the only means of creative expression of the game’s authors, who ironically refer to its technical simplicity in the introduction: ‘You’ll need a VGA card to play this game (it is not fun without it)’ (Gildur, Forion, and Morfin Citation1998).

Based on Maria Garda’s criteria, we can define MENSKBand as an original roguelike game (before ‘neo-roguelike’), and not even a particularly late example: Garda mentions a conference for developers of such games happening as late as in 2008 (Garda Citation2013). Being a clone of Angband, MENSKBand remains a canonical example of the genre and duplicates all its structural and formal features but one. While classical roguelike games were almost always set in ‘fantastic dungeons crowded with supernatural monsters’ (Garda Citation2013; Johnson Citation2017), the setting of the game is realistic to an almost documentary degree, even though the events taking place in this recognizable world are still somewhat fantastic. The place is obviously Minsk, the capital city of Belarus. It is spelled ‘Mensk’ to re-claim its independence: historically, adoption of the name Minsk is a combined result of Polish cultural hegemony in the XVIII century, Tsarist Russian colonization in the XIX century and the Soviet Russian dominance throughout the XX century. The protagonist is a rock musician named Lavon, who walks around the main square of Mensk, fighting militia, gopniks and radical Russian nationalists. His ambition is to get into the disco club, fight the DJ, then the ultimate boss - Bac’ka (‘the Daddy’) - a balding man with a moustache instantly recognized by any Belarusian - and play his own record at the party.

The protagonist of the game was clearly inspired by the real, and still creatively active, legend of Belarusian rock music Lavon Volski. He co-founded his first rock band Mroja in 1981, which eventually managed to publish a LP at the major Soviet label Melodiya in 1990. This record, ‘28-ja Zorka’ (‘28th Star’), sung in Belarusian language, addressed heavy political topics such as emigration, consequences of the Chernobyl catastrophe, and the Russian hegemony in the semi-colonised Belarus; some of these songs have since entered the canon of national rock music (such as ‘Ziamlia’ (‘The Land’) (Survilla Citation1994).

The record that Lavon would play in the fictional club Reactor would most likely be one of his later records with the reformed band N.R.M. Two most their popular albums at the time were ‘Odzirydzidzina (1996), which title song is quite literally re-enacted in MENSKBand, and ‘Pašpart hramadzianina N.R.M.’ (‘Passport of citizen of N.R.M.’) (1998). These, as well as all following works of Volski explore the increasingly complicated questions of Belarusian national identity, strengths and flows in the national character of Belarusians, and resistance against authoritarianism. Volski has even used Tolkien’s Mordor as a metaphor for the Belarusian regime on his solo record ‘Hramadaznaustva’ (‘Civic Education’) in 2014 (Karaliova Citation2016, 15), unrelated but in the same manner as the authors of MENSKBand. (‘Mordor with a million carat eye stands on a swampland and keeps an eye on everything’, cited from the translation by Karaliova in (Karaliova Citation2016). As of 2021, Lavon Volski has not left Belarus, and, just like in the game, is still occasionally halted by the militia (unlike the latter, the number of gopniks and Russian nationalists in the streets of Minsk has decreased since the 1990ies).

It would be an oversimplification to read the game as a ‘serious’ political statement or a procedural representation of protests against Lukashenko. Its anti-didactic intention was made obvious by detailed alcohol references (which its supposed authors might not be in the legal age to drink) and strengthened in the introduction from the authors: ‘Now you can fulfill your dream and beat the crap out of skinheads, gopnicks (and someone else!.)’ (Gildur, Forion, and Morfin Citation1998).

Roguelike games have historically developed their own semiotic codes based on the ASCII set of characters (Johnson Citation2017). These codes are usually explained in the manual, available under the F1 key. Typically, enemies and in-game objects are denoted by single characters of different colors: for example, D is a big dragon and d is a small dragon. This is also an example of denotation that Johnson calls ‘an abstract class’: ‘built upon clear commonality between creatures within the class and generally using the first letter of that commonality as the chosen glyph’ (Johnson Citation2017).

Semiotics of MENSKBand’s enemies reveals a curious picture of youth subcultures in the 1990s’ Belarus. ‘Monsters’ in MENSKBand are created in the same way as in classical roguelikes, but with Cyrillic characters. The letter ‘г’, which stands for a specifically Belarusian sound between plain English ‘g’ and ‘h’, is the first letter of the word ‘гопнік’ (‘gopnick’), which means a specific type of a street hooligan. ‘Gopnicks’ differ in power from red to blue to green to cyan. Their boss, marked with red ‘д’ (‘d’), is the DJ at the club. The next class is ‘ф’ - ‘f’ – it is a ‘fascist’ class, which unites aggressive radical right/left nationalists such as skinheads and communists. A blue ‘f’ signifies a small skinhead (probably a football fan, an Ultras with a blue scarf), a red ‘fascist’ is a radical communist, and a purple ‘fascist’ is a drunk radical communist. The most dangerous is the ‘Barkashov’ fascist: Barkashov was the political leader of the Russian militarist radical right Orthodox Christian party the Russian National Unity, which was active and present in Belarus in the end of the 1990s. The openly neo-nazi extremist formation has dissolved in the 2000s, allegedly after the repressive state apparatus has purged its few remaining political opponents (Belorusskij Partisan Citation2015). Finally, the last class of much less impressive ‘monsters’ is ‘м’ - the militia. Belarusian militia has acted as the suppressive tool of the authoritarian power since first public demonstrations of disagreement with the political course in the late 1990s. In the game, this class encompasses two kinds of monsters: regular militia and SWAP. Without any particular motivation, gopnicks also always fight with fascists, and militia beats everyone they encounter. In hindsight, neither Russian nationalists nor communists have never had any political power or even noticeable influence in modern Belarus. There was at least one significant violent conflict between pro-Russian neo-nazis (RNE) and pro-Belarusian democratic nationalists in 1999 (Belorusskij Partisan Citation2015), but Lukashenko’s regime quickly eliminated all possible political opponents. Still, some of the same former neo-nazi extremists have been active in the political crisis in 2020-2021, as well (REFORM.by Citation2021).

This rather realistic and, in the light of the current events in Belarus, even tragic narrative of street fighting is counterbalanced by the comical dictionary of beers, which the protagonist consumes to boost energy and power levels and, generally, stay alive. This motif, most likely, originates from Lavon Volski’s song Odzirydzidzina (1996), which described this exact scenario of having a beer, coming to one’s senses and taking over the native city. Referring back to classical roguelikes, beer would stand for ‘mana’, the counter for remaining energy, but ‘mana’ means ‘a lie’ or ‘lying’ in Belarusian, so the authors of the game have added the untranslatable warning that ‘LYING’ (‘MANA’) is not tolerated in the game.

Yet another memetic phrase ‘Died from debeeration’ (‘Pamior ad abiaspiuliennia arhanizmu’ in Belarusian), appears on the tombstone that symbolises permadeath. To postpone such a sad endspiel, Lavon can choose between four different sorts of beer to refill his energy. The first one, ‘the native village beer’, hints at the fact that most of the Minsk’s population were children of the countryside migrants who repopulated it after the tragic near-annihilation of the original urban population in the WWII and the Holocaust. Unfortunately, the revitalizing effect of ‘the native village beer’ only lasts for a few moves in the game. The second choice, ‘the Zhiguli beer’, is named after the old, and still popular, Soviet brand and recipe: a specific sort of lager still produced across all post-Soviet territories. Due to its Sovietness, this sort of beer causes the protagonist to lose control and hallucinate: the face of the first and currently illegitimate Belarusian president starts randomly appearing on the screen, masterfully created with ASCII graphics. On the semiotic level, this choice symbolises Lukashenko’s sympathy for the Soviet past.

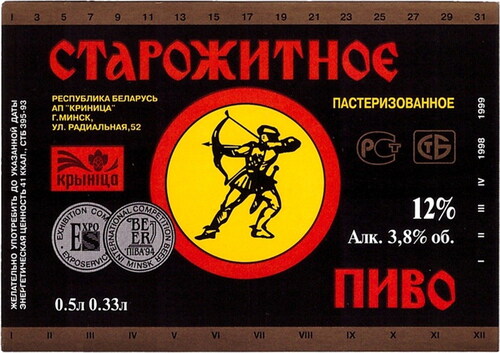

The ‘Krynica’ beer is a much better choice: the Krinitsa brand belonged to one of two major breweries in Minsk at the time, the one that was also the first to adapt Belarusian language for another sort of its beer in the early 1990s (‘Starazhytnaje’ or ‘From the old times’ in Belarusian). For some reason, the brand used creolised Belarusian in their branding in the end of 1990s, which looked as an attempt to appeal to the Russian-speaking consumers or, probably, the new state authorities (see ). Finally, the best but also the most expensive sort is ‘the Ukrainian beer’, supposedly Obolon - one of the most popular imported beers in Belarus in the 1990s. To the researcher in marketing studies, MENSKBand can also serve as an example of the first Belarusian ‘advertgame’, as well as a time capsule that preserved perception of different beer brands among educated youth.

Such attention to detail places MENSKBand on par with serious games that tend towards documentalism (Raessens Citation2006): many political games aim at trustful reproduction of reality, current or historical. ‘Docu-games’ combine ‘the facts of documentaries and the fiction of computer games’ (Raessens Citation2006, 213) in order to engage their players into real-life events, their possible causes and outcomes. In its own subversive, somewhat ‘mockumentary’ manner, MENSKBand achieves this goal without even trying: its story naturally incorporates the snapshot of the political reality at the time of its creation. Probably the most important historical event that preceded the game and most likely influenced its fiction is the Chernobyl Way march in 1996 - one of the largest mass expressions of public discord in the history of Belarus.Footnote1 This peaceful protest march gathered all significant political forces, which amounted to around 50,000 politically conscious citizens – the number that has only been surpassed in 2020. Apart from the supporters of national democracy, they also attracted both radical right and left wings of then manifold post-USSR political formations. These disagreements resulted in street fights recuperated by the militia. The supposed authors of MENSKBand were too young (and too nerdy) to participate in street brawls, but they managed to capture the spirit of late 1990s in their creation. Core fans of MENSKBand, young educated people who were already invested into the cultural and political life in Belarus, appreciated the game for showing a more fun and playable version of the world they were living in. Moreover, in the game world, the change for the better was possible, and achievable through winning the game.

To those readers who are not aware of the political situation in Belarus, its context needs to be introduced here, to explain the state of mind of young Belarusians at the end of the 1990s. The early 1990s brought the economic collapse, but also, for the first time since the establishment of the Soviet rule, free trade of products made in the West – and, most importantly, free speech and unhindered exchange of information. The political climate became intoxicatingly liberal in the 1990s, but these liberties quickly ran thin after the elections of Lukashenko in 1994. In 1996, it became obvious that the new national state would follow the way of partial re-Sovietisation and strict ideological control. This seemed unacceptable to many of the first post-Soviet generation of Belarusians whose formative years coincided with the relatively liberal late 1980s and early1990s, and this mood of freedom and resistance unites most Volski’s protest songs and the ludic challenge of MENSKBand.

Sadly, the state system has been slowly but steadily transforming into the totalitarian regime in the following 25 years. On the other hand, this quarter of a century was also the time when the Belarusian game industry went from non-existent to one of the most active and successful in the region, until the mass exodus of IT specialists in 2021 due to state violence and political pressure.

Witnesses of Transition: The Audience of MENSKBand

The story of the game’s origin was somewhat familiar to the researcher by the virtue of belonging to the same social group as its creators. To confirm it, this part of the research took place in May 2017 and sought to find out more about reception of MENSKBand from its initial audience. An online survey was created to find out how other players discovered the game, and whether it was related to their educational institution. It included four principal questions: age as of 2017, place of studies (with multiple choices and the custom answer option), by which means the game was discovered, and attitude towards the game as of 2017. After completing the survey, the respondents could additionally share their thoughts and knowledge about the game in a free form message.

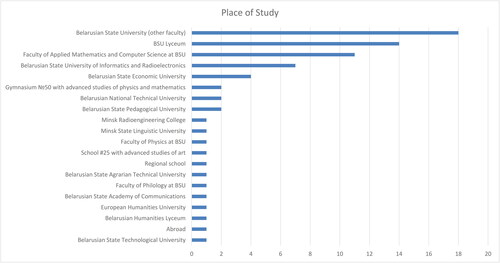

The survey was distributed between the members of the informal community of the Belarusian Unity game developers, and addressed those of them who remembered playing MENSKBand in the past. This audience was most likely to remember the game after 19 years; besides, its members served as a proper representation of the game industry in Belarus, which was born around the same time and in the same environment as MENSKBand. Most answers came from the game development community and the researcher’s friends who also remembered the game, which explains prevalence (but not complete dominance) of high education in STEM among the respondents. Also, it clearly confirms that the game was much better known in Belarusian State University (where the students of BSU Lyceum would go to study) than in Belarusian State University of Informatics and Radioelectronics, which is a much more common background for game developers in Belarus ().

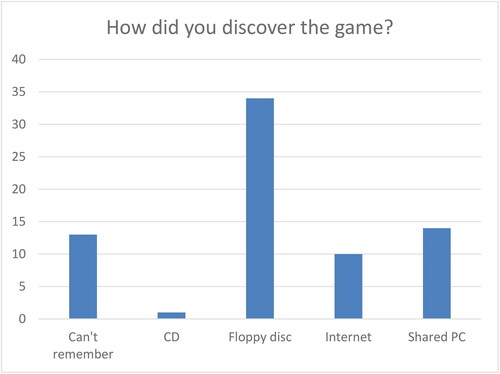

Based on the further comments of the respondents (and the author’s own experience of growing up in the same environment), MENSKBand was created by the students of the BSU Lyceum (14 respondents also confirmed they studied at the BSU Lyceum), and distributed among the students of Belarusian State University, as well as other universities, gymnasiums and lyceums.Footnote2 From 72 respondents who claimed that they had played the game, 34 respondents got it on a floppy disk, one person mentioned that it probably was a CD, 10 respondents downloaded it online, 14 respondents found it on a public computer, and 13 respondents could not remember the exact source ().

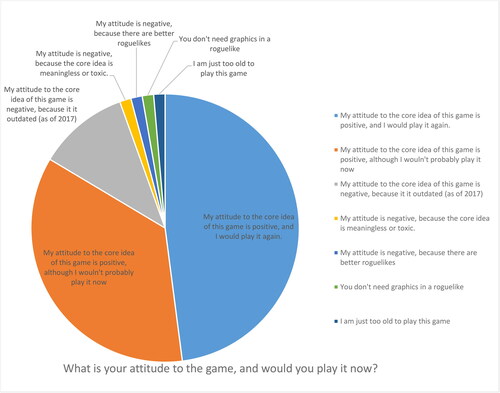

Speaking of attitude, most players remember the game with positive feelings, although not all of them would be interested in playing it now, mostly because they found it technically or conceptually outdated ().

Generally, the idea of such survey was met with many nostalgic feelings from many respondents. As far as the first generation of Belarusian gamers remembers, MENSKBand could be found on almost every public computer in the aforementioned educational institutions at the peak of its popularity, in the early 2000s. This opportunity to use a computer at school is especially important, as a PC only became a household item at a typical Belarusian family in the late 2000s. To own a personal computer in Belarus in the late 1990s-early 2000s was the sign of belonging to the lucky few, be it the class of early entrepreneurs, high profile state officials or technical intelligentsia.Footnote3 Kirkpatrick and Švelch present similar accounts for Poland and Czechoslovakia in the 1980s (Kirkpatrick Citation2007, 238; Švelch Citation2013, 164). According to Graeme Kirkpatrick’s research of early Polish computer enthusiasts who owned personal computers between 1983 and 1989, they all belonged to the middle class, and their parents often had access to computers at work. It was possible in Poland, even if difficult, to acquire a computer at that time at the black market or from the ‘privileged minority’ who could travel abroad (Kirkpatrick Citation2007, 233). Sharing computers with such ‘privileged minorities’, personal communication and social activities, such as playing games together and exchanging floppy disks, was also an important factor of democratization of personal computers across all regions (Kirkpatrick Citation2007, 237; Švelch Citation2010).

In the ordinary life, for common Belarusians, the first encounter with a personal computer happened at the extremely popular, US-sponsored exhibition Information USA in December 1988 (Manning and Romerstein Citation2004, 139), which was an inspiring exhibition of the technologies none of its visitors could possibly own at the time. Adoption of computer technologies typically started from the technical elites (intelligentsia) who relied on state support. The alternative to those from less privileged families would be to get into a very good school where selection was often based on merit. In the 1990s and sometimes even the late 1980s, the schools for gifted children were the first to be equipped with computers, and children were taught the basics of programming in BASIC or PASCAL, starting from the 7th grade or even earlier. For the needs of newly established computer education, the Soviet-developed, locally assembled Korvet series of desktop computers was produced in mass quantities in the late 1980s. However, those infamous machines, who tended to have a disproportionally long life as compared to their technical capacities, could only handle ASCII graphics. The author themselves has seen, and used, such computers, being a student at two prestigious middle schools in the capital city in the late 1990s-early 2000s. To their memory, these machines all had MENSKBand on them.

In the context of game histories, we can firmly connect the channels of distribution that were typical for the game to the ‘shareware’ culture when games were shared by members of real life communities. This culture gradually ran dry after the Internet became ubiquitous, and more personal computers were shared by fewer users. As it was happening, MENSKBand was preserved by its fans at the website http://MENSKBand.narod.ru/, where it has been available for download since the late 2000s. The game lost its popularity to that point, as it demanded a MS-DOS emulator to run on newer machines.

Historical Comparison: Playing Both Sides of the Cold War

Early computer games of the Eastern bloc are being thoroughly studied (Švelch Citation2018; Jajko, Garda, and Sitarski Citation2021) and carefully archived. For example, as of 2019, the Slovak Design Museum preserved 289 local game titles created since the 1980s (Slovak Game Developers Association Citation2019). At the same time, the video games developed in the USSR or on its former territories soon after its collapse are much less known and rarely systematically preserved. In this section, I will demonstrate that there is observable spatiotemporal continuity in topics and features of homebrew video games across Eastern Europe in 1980s-2000s. There is a distinct cluster of subversive political games that represent the fight against Communist regimes and their direct successors: some of the examples are the Polish Solidarność (Rokita Citation1991) and the Czechoslovak 17.11.1989, as well as many others. One iconic example, the early Czechoslovak game The Adventures of Indiana Jones in Wenceslas Square in Prague on January 16, 1989 (Znovuzrozený Citation1989), has been recently restored as a playable multimedia installation (Švelch and Kouba Citation2020), - as we have mentioned in the introduction, it still remains a warning against such situations as the one in contemporary Belarus.

Czechoslovakia is not unique in the history of such political games. The less studied Polish game Solidarnośc, dedicated to the anti-Communist workers’ party of the same name, was created in 1991 by Przemysław Rokita (Tobojka Citation2015). Rokita left the leading Warsaw University of Technology to work as a programmer at an early outsourcing Polish-American company. Solidarność was his own project: the original strategic game about the most prominent political movement of Poland’s trade unions, acting against the Communist Party. Different Polish regions were represented with their landmarks, such as the Palace of Culture in Warsaw.

The first Soviet Russian specimen from the sub-genre of Eastern European political games appeared relatively late, but still during the lifetime of the authoritarian Soviet empire. It is the popular Perestroika (Skripkin Citation1989), sometimes also referred to as ‘the last Soviet computer game’ (Timofeychev Citation2018). Perestroika is a variation of Frogger: its narrative follows the difficult path of an early entrepreneur in the collapsing Soviet economy. The entrepreneur is called Democrat; he jumps from one opportunity to another, trying to avoid progressive taxation, followed by the evil bureaucrats who sing and perform the memetic ‘cha cha cha’ dance after the game is over. The game clearly speaks in favour of free market and economic liberalism, both on the narrative and the procedural level, and it was commonly read as a metaphor of early capitalism on post-Soviet territories (Clarke and Koptev Citation1992). Curiously enough, it still positioned itself as a part of official culture, as opposed to counterculture: in 1990, the game was officially registered in the State Committee for Computer and Information Sciences of the USSR and the State Register of Computer Programs under the number 133 (Skripkin Citation2018).

Much less has been written about the much more political sequel to Perestroika that followed in 1991 and was, in fact, commercially distributed by the game publishing company founded by the creator of Perestroika. Ideologically, this sequel worked along the same trope of ‘fighting the Communists’ as The Adventures of Indiana Jones in Wenceslas Square and the future MENSKBand, with the same cheeky attitude and bricolage aesthetics typical for homebrew games. This sequel, named Super Toppler in English and The Defense of the White House in Russian, recreates the dramatic events in August 1991 in Moscow. In this game, the player saves the president of new democratic Russia during the 1991 Soviet coup d’état attempt. The game was updated for the 1993 re-release under the title The Siege of the White House, as the White House in Moscow was besieged by the communists once again in 1993 during the Russian constitutional crisis (Chentsov Citation2011).

The most surprising fact about MENSKBand is how closely it resembles its predecessors from the decade before. The most popular Soviet political game Perestroika should be familiar to the creators of MENSKBand, as it was literally on every personal computer within a certain time period, but Czechoslovakian and Polish games were too region-specific to be of interest to the Belarusian audience. Still, the game shares many characteristic qualities of typical Eastern European political games, including the less popular sequel to Perestroika.

The main topic of the game is the establishment of a democratic regime, and its main conflict is based on it;

The game is a remake, or, to be precise, a modification of another game;

The game is not ‘serious’ - it is ironic and ‘cool’;

The game was created by the students of a prestigious school for future technical intelligentsia;

The game is set in local context and shows local landmarks;

The game was distributed as shareware, and ‘the commons’ played a major role in its production or distribution;

The game is in the national language - and, unlike many examples named above, there were no translations in other languages in circulation.

There were, however, certain differences, as we can see on the example of Solidarność described above. Same as the political movement of Solidarność, the game about it did not come from nowhere: it was the product of local cultural and political processes. Patryk Wasiak describes communist sanctioned computer clubs in Poland (Wasiak Citation2014, 138–39): those were the places where young people could share knowledge and play games together, usually without much official supervision. Meanwhile, informal gatherings of youth were generally not tolerated in the USSR, although similar clubs also existed at so-called Houses of Pioneers, Houses of Technical Creativity and other state institutions. Knowledge sharing mostly happened on the pages of youth-oriented magazines curated by the authorities (Stachniak Citation2015), and, although such magazines sometimes published instructions on game programming (see Tatarchenko Citation2018), freedom of expression was very limited on all levels of society until the last years of the Soviet empire.

On a more positive side, the post-Soviet game industry stood on the solid fundament of the Soviet STEM education. Stories of Tetris and Perestroika demonstrate that the first Soviet computer games came from highly educated professionals who worked in the areas adjacent to the military complex and rarely if ever could afford expressing their political views – until the very last days of the USSR. For instance, the creator of Perestroika and Super Toppler, Nikita Skripkin, was a graduate of the famous Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, and most of his first game development team worked at classified research institutes before the USSR collapsed (Chentsov Citation2011, Skripkin, Citation2018). Poetically, we can say that the birth of the game industry ended the Cold War in a playful way from both sides.

Synthesis: Why There Was No Belarusian Witcher?

It can be argued that the birth of MENSKBand, as well as of the Belarusian game industry in general, became possible thanks to the post-Soviet education system, which was still undergoing liberal reforms that started as early as in the 1980s. Arguably, the game owed its longevity and omnipresence to its genre of roguelike: a technically obsolete MS-DOS game would still launch on rather primitive public computers at schools. This was also true for American universities where roguelike games initially took off in the early 1980s: the majority of computer terminals were non-graphical (Garda Citation2013). On a more positive note, technical and economic limitations of ‘sharing the commons’ stimulated creative subversions in both cases.

Using state resources to develop subversive and innovative content is not unique to the late Socialist countries: in the case of the USA, Sarah Coleman and Nick Dyer-Witheford characterize usage of freely available computer resources and code in the video game culture as ‘playing on the commons’ (Coleman and Dyer-Witheford Citation2007). These ‘commons’ may mean, for example, state-owned computers at public institutions, but also, freely accessible education in computer science provided by the state. In some cases, the political agenda of the first game designers contradicted the same authorities who acted as resource providers (Coleman and Dyer-Witheford Citation2007, 934). In the same way, state resources were used to create and share first video games in former post-Soviet countries even before mass adoption of personal computers. In short, adoption of informational technologies in Belarus can be compared to the same process in Eastern European countries, only a decade later, - and, just like in the rest of the world (Cortada Citation2013, 238), governments have played vital roles in this process.

So, what happened to game development in the Eastern Bloc after its countries re-entered the global market? Speaking of Czech and especially Polish game industries today, we do not need to dig too deep to discover internationally successful projects based on national identity and culture, such as Kingdom Come: Deliverance (Warhorse Studios, Citation2018) and, of course, the transmedia universe of The Witcher. Unfortunately, there is no such game for Belarus, with one, rather problematic, exception, which we will discuss below. Mosh characteristic and playful aspects of the Belarusian culture were discarded in the rapid transition from slowly failing socialism to accelerated authoritarian capitalism. To be fair, during the politically reactionary 2010s, the game industry in Belarus has become completely globalized and immensely successful. It produced many big titles in hardcore, as well as social and hypercasual gaming, such as the globally successful farming and colonization simulator Klondike (Vizor Interactive Citation2014), and a wildly profitable ragdoll abuse simulator Kick the Buddy ((Crustalli Citation2011), now owned by Playgendary). However, only a few occasional tabletop games have been based on Belarusian cultural heritage – but also, several ‘advertgames’, such as the one that involved the collectible figurine series Bonsticks based on Belarusian folk demonology, commissioned by one of the biggest retailers Euroopt in 2018. The characters in the ‘Bonstiks 5′ set are partly original folklore, partly literary sources and collective imagination of never completely Christianized Belarusians. As the official announcement claims, ‘All 24 heroes are absolutely real characters (highlighted by me – A.S.) originally from Belarusian myths and legends’ (Euroopt Citation2018). If only Belarusian creators were given enough freedom within their own country, they would be able to apply an abundance of resources, both technical and inspirational, to a project of the Witcher’s scale.

In contrast, the best known success story in Belarusian game development has thrived due to satisfying Soviet nostalgia of a significant, initially mostly Russian-speaking, audience. This is the story of Wargaming, the Cyprus-registered, initially Belarus-based company that created World of Tanks (Wargaming Citation2010). The company was founded in Minsk in 1998 - the same year the game MENSKBand was born. It took Wargaming twelve years to achieve success with their first minor hit, Operation Bagration (Wargaming Citation2007), also set in Belarusian locations, but in the Soviet times of the World War II. The company’s biggest global hit took a step further in the same ideological direction: it celebrated the Soviet trope of the Great Patriotic War in a nostalgic way that resonated with its large post-Soviet audience and evoked the sentiments closely related to, if not completely overlapping with, restorative Soviet nostalgia of Lukashenko’s regime. World of Tanks has been approved by the currently illegitimate president himself - he confirmed that his youngest son was playing it (Pankavec Citation2016). This is probably the reason for the ambiguous political position of Wargaming during the latest political crisis, although the company has also relocated many of its employers to the offices abroad.

Speaking of the core audience of MENSKBand, Soviet nostalgia has never been a part of their world view: the game expresses disdain for Soviet imperialism in many ways, such as distaste for (otherwise rather decent) Zhiguli beer. From today’s perspective, MENSKBand was a cheerful and self-aware exploration of national identity and a challenge to authoritarian power - the challenge that failed but is still a dear memory to many Belarusians. After more than two decades since its creation, it remains the only significant, memorable and replayable video game created primarily in Belarusian language, in a vivid and recognizable Belarusian setting. The next influential work of subversive playful media in the Belarusian language, the virtual world Viejšnoryja, appeared only in 2017 (Astapova and Navumau Citation2018). This online world looked extremely archaic, mostly existing as a text-based roleplaying game, but it incorporated playful exploration of the new blockchain technology, to very little results, which would be the topic for another research.

Conclusion

So far, the most interesting parts of early game history tends to happen somewhere between the earliest ‘commons’ becoming available to intellectual elites and eventual seamless integration into the global market. Early political games in Eastern Europe served as important vehicles for young people’s identities beyond the direct reach of the Communist authorities. For this purpose, they often employed local contexts, such as local landmarks and titles of political parties, - and, of course, national languages. Both pirated and homebrew games were distributed in specific ways that did not require a network connection, but often relied heavily on local communities. Electronic networks were never a necessary precondition to realize the subversive potential of early Eastern European games: it could as well be facilitated by shareware and ‘gift economy’ in human networks, lending resources from the same oppressive administrative system they resisted. This article demonstrates that the first notable Belarusian computer game has followed a very similar path, and is typical for this subgenre even despite geopolitical isolation.

Uniqueness of the game comes from its very recognizably ‘Belarusian’ fictional world. With its almost documentary attention to detail, MENSKBand does not seek historical accuracy: its main story is still as believable as Indiana Jones fighting Soviet tanks in Prague. However, its text consists of very specific cultural references, and each of these references can be unfolded into a meaningful story about Belarus in the 1990s.

The fictional story of the game is rather comical, and many of its older players found it outdated as of 2017 (their opinion might have changed in 2020-2021, but these were not the best years to do any empirical research in Belarus). However, this perceived flaw is also very typical: when used for political statements, early Eastern European games often maintain a tongue-in-cheek attitude, or youthful ‘coolness’: Švelch demonstrates the irony in the analysis of the Slovak game Šatochin, where the Soviet Mayor Shatokhin fights Rambo in ‘a parody of both American action movies and Soviet war hero narratives’ (Švelch Citation2013, 173). Still, unlike many of those early games, which expressed rather blunt and quickly outdated political statements (Švelch Citation2013, 171–72; also see Chentsov Citation2011 on Super Toppler), MENSKBand is a rather nuanced and replayable game, even though it was left unfinished - the subway in the game is possible to enter, but it has never materialized as a playable location. While the setting and narrative of MENSKBand is surprisingly similar to The Adventures of Indiana Jones in Wenceslas Square in Prague on January 16, 1989, its gameplay, however, demonstrates that its creators had potential to create the game as complex as Solidarność. Unfortunately, according to the information gathered, they did not proceed with game development careers. In a wider perspective, the case of MENSKBand illustrates the importance of public educational institutions as free ‘testing grounds’ for different forms of creativity, sufficiently equipped with innovative resources that can be used as ‘shared commons’ by children and young people regardless of their social and economic status.

Needless to say, the game’s call for liberation from the oppressive authoritarian/totalitarian regime has only become more relevant after the falsified Belarusian elections in August 2020 and the large scale political repressions that followed. Throughout most of the XX century, Belarus has been the western frontier of the USSR and a transitional territory between socialism and capitalism. Same as nation building (and also historically connected to it), economic transformation has been an ongoing process, with varying levels of intensity and completeness across Eastern Europe, and its inconclusiveness is still named as the major risk factor in the otherwise successful Belarus game industry (see e.g. United States Securities and Exchange Commission Citation2021, 35). We have already seen how high potential of Soviet STEM education was hindered by harsh political climate, and, as of 2022, the restorative regime in Belarus seems to be following the same path, once again.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alesha Serada

Alesha Serada is a PhD student and a researcher at the University of Vaasa, Finland. Their research interests are inspired by their Belarusian origin, revolving around exploitation, violence, horror, deception and other banal and non-banal evils in visual media. In their spare time, Alesha writes on late Soviet and post-Soviet visual culture to make it more accessible to the English-speaking audience.

Notes

1 As most of the radioactive fallout landed, and still remains, in Belarus, the Chernobyl disaster has become the symbol of the imperial Soviet politics and its deadly consequences for the locals. The protest started as yearly peaceful march in 1989; in 1996, it became the public expression of disagreement with restitution of the Soviet ideology by Lukashenko. The peaceful march was dispersed by the special units of militia in 1996, and openly reclaimed as a political manifestation by the Belarusian opposition, somewhat unified back then (Arsenov Citation2015). All later street manifestations were brutally suppressed by the militia regardless of expressed political preferences and sometimes even presence thereof (so-called ‘silent protests’ in 2011 or wearing white and red clothes in 2020).

2 Gymnasiums and lyceums are a form of free public middle and high schools created in Belarus in the late 1980s, aimed at specialised education to prepare gifted children for the best universities. They still exist, even though the public opinion and the state attitude to ‘elite schools’ have fluctuated towards the critique of their ‘elitism’. The reason most of these schools were not downgraded later is that their students and graduates show outstanding results at local and global contests, especially competitive programming.

3 As it was in the case of the CEO of Wargaming, one of the most successful businessmen in the Belarusian game industry Victor Kislyi (Pankavec Citation2016).

References

- Arsenov, Aleksandr. 2015. April 26. ‘Kak prohodil Chernobyl’skij shljah v 1989, 1996 i v nashi dni’. (‘How the Chernobyl Way Was Carried out in 1989, 1996 and Today.’) Nasha Niva. https://nn.by/?c=ar&i=148405&lang=ru

- Astapova, Anastasiya, and Vasil. Navumau. 2018. “Veyshnoria: A Fake Country in the Midst of Real Information Warfare.” Journal of American Folklore 131 (522): 435–443. doi:10.5406/jamerfolk.131.522.0435.

- Belorusskij Partisan. 2015. ‘Belorus iz batal’ona «Azov» - geroj, avantjurist ili nacist? Istorija Sergeja Korotkih’ (‘The Belarusian from the ‘Azov’ Batallion: A Hero, an Opportunist or a Nazi? The Story of Sergey Korotkikh.’) Belarusian Partisan, 20 16/01 2015. https://belaruspartisan.by/life/292580/.

- Chentsov, Ilya. 2011. “Dvadcat’ Let Bez Soyuza - Dvadcat’ Let s ‘Nikitoj.’’ (‘Twenty Years without USSR – Twenty Years with Nikita’).” Strana Igr 10: 44–51.

- Clarke, Nigel., and Sergey. Koptev. 1992. “The Russian Consumer: A Demographic Profile of a New Consumer Market.” The Journal of European Business (New York) 4 (1): 23.

- Coleman, Sarah., and Nick. Dyer-Witheford. 2007. “Playing on the Digital Commons: Collectivities, Capital and Contestation in Videogame Culture.” Media, Culture & Society 29 (6): 934–953. doi:10.1177/0163443707081700.

- Cortada, James W. 2013. “How New Technologies Spread: Lessons from Computing Technologies.” Technology and Culture 54 (2): 229–261. doi:10.1353/tech.2013.0081.

- Crustalli. 2011. Kick the Buddy. Playgendary.

- Cutler, Alex, and Andy. Astrand. 1990. Angband. Angband Development Team.

- Euroopt. August 2018. ‘Unbelievable, but True: Bosticks Are Coming Back to Euroopt.’ Euroopt (blog). https://evroopt.by/.

- Garda, Maria B. 2013. “Neo-Rogue and the Essence of Roguelikeness.” Homo Ludens 1 (5): 59–72.

- Gildur, Forion, Morfin. 1998. MENSKBand. MS-DOS. Minsk.

- Jajko, Krzysztof. Maria B. Garda, and Piotr. Sitarski. 2021. New Media behind the Iron Curtain: Cultural History of Video, Microcomputers and Satellite Television in Communist Poland. Kraków: Jagiellonian University.

- Johnson, Mark R. 2017. “The Use of ASCII Graphics in Roguelikes: Aesthetic Nostalgia and Semiotic Difference.” Games and Culture 12 (2): 115–135. doi:10.1177/1555412015585884.

- Karaliova, Tatsiana. 2016. “Not on Your Air: Resistance and Search for National Identity in Songs of Banned Belarusian Artists.” ‘International Communication Research Journal 51 (1). http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A579538831/AONE?sid=googlescholar.

- Kirkpatrick, Graeme. 2007. “Meritums, Spectrums and Narrative Memories of ‘Pre-Virtual’ Computing in Cold War Europe.” The Sociological Review 55 (2): 227–250. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00703.x.

- Manning, Martin J., and Herbert. Romerstein. 2004. Historical Dictionary of American Propaganda. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Mitchell, J. Clyde. 1983. “Case and Situation Analysis.” The Sociological Review 31 (2): 187–211. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.1983.tb00387.x.

- Pankavec, Zmicier. 2016. ‘Pjat’ faktov o samom uspeshnom biznesmene Belarusi Viktore Kislom’ (‘Five Facts about the Most Successful Belarusian Businessman Victor Kislyi.)’ Nasha Niva, February 21, 2016. https://nn.by/?c=ar&i=165349&lang=ru.

- Raessens, Joost. 2006. “Reality Play: Documentary Computer Games beyond Fact and Fiction.” Popular Communication 4 (3): 213–224. doi:10.1207/s15405710pc0403_5.

- REFORM.by. 2021. ‘Sirota, fanat, boec, sudim, smenil familiju. Kak Vitalij Shishov okazalsja v komande Bocmana’ (‘An Orphan, a Fan, a Fighter, a Convict, a Name Changer. How Vitaly Shishiv Ended Up on the Bootsman’s Team.’) REFORM.by, August 7, 2021. https://reform.by/247739-sirota-fanat-boec-sudim-smenil-familiju-kak-vitalij-shishov-okazalsja-v-komande-bocmana.

- Rokita, Przemysław. 1991. Solidarność. DOS. Warsaw.

- Skripkin, Nikita. 1989. Perestroika. DOS. Borland C++. Moscow: Locis.

- Skripkin, Nikita. 2018. ‘Geroi «Perestrojki»’ (‘Heroes of Perestroika.’) Hypestorm, February 16, 2018. http://hypestorm.ru/perestroika/.

- Slovak Game Developers Association. 2019. ‘Report: Slovak Game Industry 2019.’ Slovak Game Developers Association. http://sgda.sk/report-slovak-game-industry-2019/.

- Stachniak, Zbigniew. 2015. “Red Clones: The Soviet Computer Hobby Movement of the 1980s.” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 37 (1): 12–23. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2015.11.

- Survilla, Maria P. 1994. “Rock Music in Belarus.” Rocking the State, 219–241. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Švelch, Jaroslav. 2010. “Selling Games by the Kilo: Using Oral History to Reconstruct Informal Economies of Computer Game Distribution in the Post-Communist Environment.” 265–277.

- Švelch, Jaroslav. 2013. “Say It with a Computer Game: Hobby Computer Culture and the Non-Entertainment Uses of Homebrew Games in the 1980s Czechoslovakia.” ‘Game Studies 13 (2) http://gamestudies.org/1302/articles/svelch.

- Švelch, Jaroslav. 2018. Gaming the Iron Curtain: How Teenagers and Amateurs in Communist Czechoslovakia Claimed the Medium of Computer Games. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Švelch, Jaroslav. and Martin. Kouba. 2020. “Indiana Jones Revisits Wenceslas Square.” ROMchip 2 (2) https://romchip.org/index.php/romchip-journal/article/view/115.

- Swalwell, Melanie. 2021. Homebrew Gaming and the Beginnings of Vernacular Digitality. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Tatarchenko, Kseniya. 2018. “The Great Soviet Calculator Hack: Programmable Calculators and a Sci-fi Story Brought Soviet Teens into the Digital Age.” IEEE Spectrum 55 (10): 42–47. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.2018.8482423.

- Timofeychev, Alexey. 2018. ‘Perestroika: The Last Soviet Computer Game Peddled Democracy.’ Russia Beyond, January 16, 2018. https://www.rbth.com/arts/327268-perestroika-last-soviet-computer-game.

- Tobojka, Adam. 2015. ‘Zapomniana gra o „Solidarności’ (‘A forgotten game about “Solidarity”).’ Eurogamer.pl, August 15, 2015. http://www.eurogamer.pl/articles/2015-08-15-zapomniana-gra-o-solidarnosci.

- United States Securities and Exchange Commission. 2021. Playtika Holding Corp. Form 10-K. Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.’ Washington, DC: United States Securities and Exchange Commission.

- Vizor Interactive. 2014. Klondike. Minsk: Vizor Interactive.

- Wargaming. 2007. Operation Bagration. Minsk: Wargaming.

- Wargaming. 2010. World of Tanks. Minsk: Wargaming.

- Warhorse Studios. 2018. Kingdom Come: Deliverance. Prague: Deep Silver

- Wasiak, Patryk. 2014. “Playing and Copying: Social Practices of Home Computer Users in Poland during the 1980s.” In Hacking Europe, edited by Gerard Alberts and Ruth Oldenziel, 129–150. History of Computing. London: Springer London. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-5493-8_6.

- Znovuzrozený, Zuzan. 1989. “The Adventures of Indiana Jones in Wenceslas Square in Prague on January 16, 1989.” ZX Spectrum. Prague.