ABSTRACT

In two experiments, we examined whether explicit attention to another’s perspective fosters perspective-taking. In the first experiment, we attempted to replicate previous findings showing that a mind-set focusing on self-other differences incites speakers to adopt another’s viewpoint in a subsequent task. However, our results showed that speakers focusing on self-other differences were just as likely to describe an object’s location from their egocentric perspective as speakers focusing on self-other similarities. In the second experiment, we intensified speakers’ awareness of perspectives by explicitly instructing them to regard their own (self-focus) or another’s (other-focus) viewpoint during the perspective-taking task. Participants allocated to the baseline did not receive explicit focus instructions. Findings revealed that other-focused speakers were more likely to adopt another’s perspective than self-focused speakers. However, compared to the baseline, an explicit other-focus did not foster perspective-taking. We conclude that an explicit awareness of perspective differences does not attenuate speakers’ egocentricity bias.

Introduction

Many things in social life rely on our ability to imagine ourselves in another person’s shoes. Whether we buy a present for our beloved partner, communicate to friends or colleagues, or bargain at a local market, we often imagine how others view the world around them so that we are able to fulfil our common social needs. Although perspective-taking is entrenched in all our daily activities, this does not imply that all perspective-taking acts are actually successful.

A large body of research paints a conflicting picture with regard to communicators’ ability to spontaneously represent another person’s perspective. On the one hand, studies argue that interlocutors rapidly integrate another person’s perspective during communication (Brown-Schmidt & Hanna, Citation2011; Brown-Schmidt & Tanenhaus, Citation2008; Brown-Schmidt, Gunlogson, & Tanenhaus, Citation2008; Hanna & Tanenhaus, Citation2004; Hanna, Tanenhaus, & Trueswell, Citation2003; Heller, Gorman, & Tanenhaus, Citation2012; Heller, Grodner, & Tanenhaus, Citation2008; Nadig & Sedivy, Citation2002), especially when mutual understanding is in danger of being jeopardised (Mainwaring, Tversky, Ohgishi, & Schiano, Citation2003; Schober, Citation1993). In support of this view, studies have shown that speakers are able to automatically (unconsciously and unintentionally in Schneider, Slaughter, & Dux, Citation2017) process what (Qureshi, Apperly, & Samson, Citation2010; Samson, Apperly, Braithwaite, Andrews, & Bodley Scott, Citation2010; Schneider, Nott, & Dux, Citation2014; Schurz et al., Citation2015; Surtees & Apperly, Citation2012; Surtees, Samson, & Apperly, Citation2016), and how others represent the world around them (Elekes, Varga, & Király, Citation2016; Tversky & Hard, Citation2009). In contrast to these findings, other research suggests that perspective-taking does not always occur automatically or spontaneously. These studies have shown that communicators’ egocentric perspective often has primacy (Apperly, Back, Samson, & France, Citation2008; Epley, Morewedge, & Keysar, Citation2004; Ferguson, Apperly, & Cane, Citation2017; Keysar, Lin, & Barr, Citation2003), and that even in situations that require explicit perspective-taking communicators often fail to accurately regard their interlocutor’s perspective (Damen, van der Wijst, van Amelsvoort, & Krahmer, Citation2018; Horton & Keysar, Citation1996; Kaland, Krahmer, & Swerts, Citation2014; Wardlow Lane & Liersch, Citation2012; Wardlow Lane & Ferreira, Citation2008; Wardlow Lane, Groisman, & Ferreira, Citation2006). These failed attempts at perspective-taking are argued to be the result of egocentric-intrusion effects (Apperly et al., Citation2010; Ferguson et al., Citation2017; Samson et al., Citation2010) during which communicators find it difficult to inhibit their egocentric representation when trying to represent the perspective of others. Egocentric intrusions are explained by the communicators’ egocentricity bias (Barr & Keysar, Citation2005; Birch & Bloom, Citation2007; Epley, Keysar, Van Boven, & Gilovich, Citation2004; Keysar, Barr, & Horton, Citation1998; Krueger & Clement, Citation1994). According to this bias, the ease by which communicators have access to their own perspective—in contrast to the impermeable nature of the other’s mind—makes communicators likely to anchor their perspective-judgments on their egocentric representation. This leads to instances in which communicators might falsely project (Ames, Citation2005) their own perspective onto others, thereby failing to appreciate the other’s potentially different vantage point.

In two experiments, we investigate communicators’ tendency to engage in spontaneous perspective-taking and question how we can stimulate communicators to inhibit an egocentric interpretation by adopting another person’s perspective. In the first experiment, we build on the assumption that a clear distinction between the self and the other incites perceivers to spontaneously adopt another person’s point of view (Decety & Sommerville, Citation2003; Mitchell, Citation2009; Santiesteban et al., Citation2012; Todd, Hanko, Galinsky, & Mussweiler, Citation2011). Under this assumption, we follow Todd et al.’s (Citation2011) predictions that perceivers are more likely to take another person’s perspective if they are (made) aware that this person’s representation of the world differs from their own. In the second experiment, we explore the extent to which perceivers’ explicit focus on another person’s viewpoint might help them to inhibit an egocentric interpretation.

The self-other distinction and perspective-taking

Prior research has shown that a feeling of similarity rather than dissimilarity between the self and the other is positively related to interpersonal attraction and attitude and behavioural change. Not only are we more attracted to others who think alike (Byrne, Citation1961; Byrne & Nelson, Citation1965; Festinger, Citation1954; Stroebe, Insko, Thompson, & Layton, Citation1971), we are also more likely to positively evaluate experiences we share with similar rather than dissimilar others (Boothby, Smith, Clark, & Bargh, Citation2017). People who share our opinions and attitudes are also found to be more persuasive (Brown & Reingen, Citation1987; Simons, Berkowitz, & Moyer, Citation1970), and we are more likely to help others who are like us (Maner et al., Citation2002). Research has argued that feelings of similarity might even help us to better understand others (Elfenbein & Ambady, Citation2002; Stotland, Citation1969). However, these feelings of similarity between the self and the other cause a sense of self-other overlap (Aron, Aron, Tudor, & Nelson, Citation1991) that might not be beneficial for accurate perspective-taking (see also Cheek, Citation2015). That is, being able to imagine the feelings and beliefs of others requires that people recognise that the “the self” and “the other” are still two distinct and unique identities (Decety & Sommerville, Citation2003) who do not necessarily share perspectives. When people fail to realise self-other differences, they may falsely believe that a similarity between their thoughts and feelings and those of others exists. False beliefs of similarity can thus lead to instances in which people wrongly assume that others perceive the world as they do, causing them to inaccurately project the self onto (dissimilar) others (Mitchell, Citation2009; Mitchell, Macrae, & Banaji, Citation2006; Mussweiler, Citation2003; Santiesteban et al., Citation2012; Savitsky, Keysar, Epley, Carter, & Swanson, Citation2011; Simpson & Todd, Citation2017; Todd et al., Citation2011). Following the egocentric anchoring and adjustment approach to perspective-taking (Epley, Keysar, et al., Citation2004), if perceivers experience a (false) sense of similarity, they might see no reason to adjust for their initial egocentric interpretation and may thus fail to realise that others can have a representation that differs from their own. In this case, people’s interpretation of the other’s perspective will be anchored on an egocentric interpretation. Perspective-taking, in the true sense of the word, does not occur. To prevent egocentric anchoring, perceivers need to be aware that self-projection is inappropriate (Ames, Citation2004; Krueger & Clement, Citation1994), and it has been suggested that one way to do so is by raising perceivers’ awareness that differences in mental representations do exist (Santiesteban et al., Citation2012; Todd et al., Citation2011).

Research by Todd et al. (Citation2011) has shown that perceivers are likely to adjust away from an egocentric interpretation if they see themselves and others as being unique and distinct. Their research showed that visually priming perceivers with a mind-set that focuses on visual differences between pictures resulted in—spontaneously—acknowledging differences in perspectives in a subsequent spatial perspective-taking task. That is, those primed with a cognitive orientation to acknowledge self-other differences rather than self-other similarities were more inclined to adopt another person’s perspective. Todd et al. (Citation2011) achieved these cognitive orientations by asking participants to complete a picture-comparison task (following Mussweiler, Citation2001) prior to the spatial perspective-taking task. During this picture-comparison task, participants noted down either the differences (priming a difference-mind-set) or the similarities (priming a similarity-mind-set) between pairs of pictures. According to Todd et al. (Citation2011), acknowledging the differences or similarities between the picture-pairs translated to participants also acknowledging the differences in perspectives. That is, in Todd et al. (Citation2011) first experiment, participants primed with a mind-set focusing on differences were more likely to locate an object from another person’s visual perspective than the participants who were primed to focus on similarities. In subsequent experiments, participants’ focusing on self-other differences were less likely to project their privileged knowledge about a communicative intention (experiment 2) and about an object’s location (experiment 3) to an uninformed other than those who were primed to focus on self-other similarities. The activation of self-other differences in perceivers’ mental representation thus seemed to reduce egocentrism and to stimulate perspective-taking. In this study, we investigate whether we can replicate Todd et al.’s findings (Citation2011). In particular, we examine the question whether a picture-comparison task prior to the spatial perspective-taking task activates a mind-set that stimulates spatial perspective-taking.

Experiment 1

In the first experiment, we investigated whether a primed difference-mind-set incites participants to spontaneously adopt the visual perspective of another person. For this, we directly replicated the experimental design of Todd et al.’s (Citation2011) first experiment, and asked participants to take part in a spatial perspective-taking task (Tversky & Hard, Citation2009). During this task, participants described the location of an object that could be located on the basis of participants’ own spatial perspective or from the perspective of another person. This task taps into spontaneous perspective-taking because it measures individuals’ propensity to adopt another person’s frame of reference without being explicitly instructed to do so. Object locations that orient the object from the other person’s perspective show that people appreciate the unique vantage point of this person,Footnote1 and thereby prioritise this vantage point over their predominant egocentric frame of reference (see also Tversky & Hard, Citation2009). As in Todd et al. (Citation2011), we predicted that the participants primed with a difference mind-set would be less influenced by their egocentric perspective and thus more likely to adopt an other-oriented perspective than participants primed with a similarity mind-set or participants in a control condition.

In addition to the replication of Todd et al. (Citation2011), this study also takes into account possible individual differences that might exist with regard to individuals’ ability and propensity to engage in perspective-taking. A large body of research has shown that people differ in the extent to which they have the social and cognitive capacity to engage in perspective-taking (e.g. Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, Raste, & Plumb, Citation2001; Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, Martin, & Clubley, Citation2001; Brunyé et al., Citation2012; Bukowski & Samson, Citation2017; Ryskin, Benjamin, Tullis, & Brown-Schmidt, Citation2015; Wardlow, Citation2013). For instance, whereas first was believed that especially people with developmental disabilities, such as autism spectrum disorders, were “poor” perspective-takers, it is increasingly acknowledged that the characteristics associated with the autism spectrum can even be found in the non-clinical population at large (e.g. Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, et al., Citation2001; Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, et al., Citation2001; Brunyé et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, research showed that individuals differ in the extent to which they have the cognitive capacity to perform the cognitive tasks that are associated with (accurate) perspective-taking performance (e.g. Bukowski & Samson, Citation2017; Ryskin et al., Citation2015; Wardlow, Citation2013). That is, individuals who have a higher cognitive capacity to direct their attention to relevant perspective-information (i.e. working memory), or those who are more able to inhibit their egocentric perspective (i.e. inhibitory control) outperform individuals with a lower working memory and/or inhibitory control capacity (e.g. Brown-Schmidt, Citation2009; Bukowski & Samson, Citation2017; Carlson & Moses, Citation2001; Carlson, Moses, & Claxton, Citation2004; Lin, Keysar, & Epley, Citation2010; Nilsen & Graham, Citation2009; Wardlow, Citation2013). In this study, we therefore anticipate the existing individual differences in perspective taking by increasing the sample size of the original study and by measuring individuals’ perspective-taking propensity (self-report), and their ability to engage in spatial (Huttenlocher & Presson, Citation1973) perspective-taking (Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, et al., Citation2001).

Method

Participants and design

128 participants (50 more than in the original study) were recruited from the university and randomly assigned to one of the three conditions (difference-mind-set, similarity-mind-set, or control condition). Participants gave their informed consent to partake in the study. The data of four participants were excluded from the analysis, due to an error in the experimental procedure (n = 2), or due to them guessing the actual purpose of the experiment during the debriefing (n = 2). This resulted in 43 participants in the difference-mind-set condition, 39 in the similarity-mind-set condition and 42 in the control condition. The age of the participants ranged from 17 to 36 years (M = 21.55; SD = 3.28), and the majority of participants (72%) was female.

Procedure and materials

Priming a difference or similarity mind-set

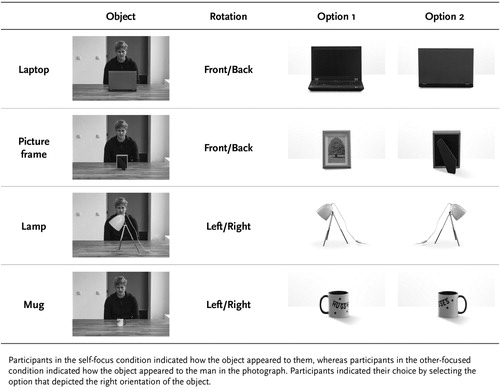

The priming materials used by Todd et al. (Citation2011) were obtained from Todd (p.c.) and translated into Dutch. On entering the lab, participants took place in private cubicles and were told that they were participating in a study investigating the effectiveness of several experimental stimuli. Participants were blind to the experimental conditions. To prime participants with either a difference- or similarity-mind-set, we replicated the picture-comparison task from Todd et al. (Citation2011). In this task, participants compared four pairs of pictures of drawn houses and listed either three differences (difference-mind-set) or three similarities (similarity-mind-set) between each presented pair. Participants in the control condition were only confronted with four singular pictures of drawn houses for which they were asked to describe them by listing three attributes for each picture. An example of a trial used during the picture comparison task is presented in . As in Todd et al. (Citation2011), participants received the priming materials in booklets. The singular pictures (control) and picture-pairs (difference- and similarity-mind-set) were presented on separate pages.

Figure 1. An example of a picture-pair shown to participants during the picture-comparison task (Todd et al., Citation2011). Due to copyright, the example portrays dummy pictures instead of the original ones. Participants listed either the three similarities (evoking a similarity-mind-set) or three differences (evoking a difference-mind-set) between the two pictures. In the control condition, only one picture of the pair was shown and participants listed three attributes that described that picture.

Spatial perspective-taking

After the priming task, participants completed a spatial perspective-taking task on the computer screen in front of them. In this task, participants were shown a photographed scene of a man seated behind a table facing the participants (). We re-enacted Todd et al. (Citation2011) visual scene, because we wanted to use different versions of this scene in experiment 2. On the table, a book and bottle were placed using a clear left and right distinction. Participants answered five filler questions about the picture. These questions were asked by the computer and participants typed in their answer in response boxes. The filler questions were translated from Todd et al. (Citation2011) and asked participants to comment on other properties of the picture unrelated to perspectives, such as “How would you judge the brightness of this picture?” and “How old would you say the man is?”. Among these filler questions, participants answered the target question “On what side of the table is the book?”. As in Todd et al. (Citation2011), this target question measured participants’ perspective-taking in a single trial. Participants’ answers to the target question were coded according to the guidelines set by Todd et al. (Citation2011), and Tversky and Hard (Citation2009). We coded participants’ answers in terms of the perspective they mentioned first and scored answers that located the book from participants’ own viewpoint (“right side”) as self-oriented responses (0), and answers that located the book from the man’s viewpoint (“left side”) as other-oriented responses (1). Descriptions that fit in neither category (e.g. “at the top” or “in the middle”) were excluded (Ndifference-mind-set = 6; Ncontrol = 4). As in the original study, participants completed this task without time pressure.

Figure 2. The photographed scene in the spatial perspective-taking task. Participants indicated on what side the book on the table was placed.

On top of replicating the experimental procedure of Todd et al. (Citation2011), we administered three subsequent tasks that measured participants’ (self-reported) perspective-taking, their mental rotation ability and their ability to engage in perspective-taking. This way, we were able to account for possible underlying mechanisms that could influence perceivers’ spatial perspective-taking, without harming the replication study.

Self-reported perspective-taking

We assessed participants’ (self-reported) tendency to regard the man’s perspective by six items. Participants indicated how much they agreed with the declarative sentences (e.g. “I generally tried to imagine how the man in the picture looked at the situation”) on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). The scale had a high reliability (α = .77), and the items represented a one-dimensional scale with all factors loading above .40 (see ).

Table 1. Items of the self-reported perspective-taking scale for experiment 1 and experiment 2.

Mental rotation ability

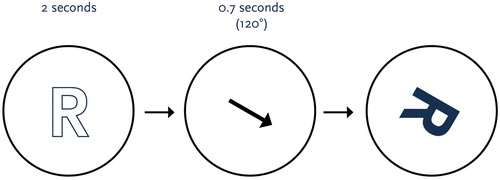

Being able to imagine how an object appears to an observer has been argued to depend largely on one’s ability to mentally rotate the object in question (Huttenlocher & Presson, Citation1973), especially when observers look at the object from an angular disparity from 90 degrees and onwards (Roberts & Aman, Citation1993). To account for the possible influence of participants’ mental rotation ability on their propensity to regard the spatial perspective of another person, participants took part in a shortened version (24 experimental and 8 practice trials) of Cooper and Shepard’s (Citation1973) mental rotation task. This task was administered on the computer, using E-prime version 2. Participants indicated whether visual displays of a letter (R) and a number (2) were presented normally or reflected. Participants were first shown the identity of the visual display (i.e. R/2) during a 2 s time span, followed by a visual display of the orientation the letter or number would later appear in during a 700 ms timespan. We based this 700 ms time span on the findings by Cooper and Shepard (Citation1973) who showed that between 700 and 1000 ms the difficulty to represent the normally or reflected objects disappears. The visual displays were presented in orientation degrees ranging from 0 to 360 degrees (). Since a 180-degree rotation increases error rate and determination time (Cooper & Shepard, Citation1973), we included four practice trials in which the designated object was rotated 180 degrees away from its initial upright position, two practice trials depicting a 60-degree orientation, and two practice trials in which the target did not depart from the initial orientation (0 degrees). In the experimental trials, items were presented in a randomised order and the orientation degrees were equally represented. Whether the target was presented as a number or letter, and whether the designated object would appear normally or reflected was balanced across all trials. Participants were instructed to respond as quickly and as accurately as possible. Participants’ mental rotation proficiency was estimated by calculating their overall error rate (in proportions). Overall, participants were accurate on 80% of the trials (Mcontrol = 0.79, SD = 0.02; Msimilarity-mind-set = 0.80, SD = 0.02; Mdifference-mind-set = 0.82, SD = 0.02).

Figure 3. Example of a trial from the mental rotation task (Cooper & Shepard, Citation1973). Participants were first shown the identity of the visual display, followed by the orientation this display would later appear in, followed by the target stimulus. Participants indicated whether the target was presented normally or reflected.

Autism-spectrum quotient scale

Previous research indicated that people vary in their social and cognitive ability to engage in perspective-taking (e.g. Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, et al., Citation2001, Citation2001; Brunyé et al., Citation2012; Wardlow, Citation2013). The Autism-Spectrum Quotient Scale (AQ; Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, et al., Citation2001) is a validated and reliable scale that measures these individual differences in perspective-taking ability. As a final step in the experimental procedure, we asked participants to respond to an abridged and Dutch translated version of the AQ construed and validated by Hoekstra et al. (Citation2011). In this way, we were able to account for the possible influence of individual differences in perspective-taking ability on subsequent perspective-taking behaviour. The abridged version consisted out of 28 declarative sentences (e.g. “Reading a story, I find it difficult to work out the character’s intention”) that were measured on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Higher values indicated that participants had a low social and cognitive ability to engage in perspective-taking. The AQ had a very good internal consistency (α = .89). After filling out the AQ-Short, participants’ demographics were collected. Afterwards, participants were debriefed and thanked for their participation. Participants were rewarded by course credits. The ethics review committee of the Tilburg School of Humanities and Digital Sciences has approved this experiment to be in full compliance with the relevant codes of experimentation and legislation.

Results

The dataset of this experiment can be accessed via osf.io/by47d. In , the mean proportions of other-oriented location descriptions in the original Todd et al. (Citation2011) study and in our replication study are presented.

Table 2. Mean proportions of other-oriented location descriptions as a function of condition.

The proportions of other-oriented responses did not differ much between the control (M = .39, SD = .50), similarity-mind-set (M = .31, SD = .47) and difference-mind-set (M = .27, SD = .45) conditions. The participants in the difference-mind-set condition in our replication study, however, were two times less likely to produce an other-oriented response, than those participants in the original study (M = .62, SD = .50).

Todd et al. (Citation2011) performed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with planned comparisons to investigate the influence of the primed mind-sets on the probability of an other-oriented location description to occur. We replicated this method of analysis and did not find a significant main effect of condition, F(2, 111) = 0.69, p = .503. Participants with a difference-mind-set (M = .27, SD = .45) were just as likely to provide a location description that was oriented from the perspective of the man in the photograph as the participants with a similarity-mind-set (M = .31, SD = .47), t(111) = 0.35, p = .365, and the participants in the control condition (M = .39, SD = .50), t(111) = 1.14, p = .128. Participants’ propensity to provide an other-oriented location description also did not differ between the control and similarity-mind-set condition, t(111) = 0.81, p = .210.

Moderation analysis

To investigate whether participants’ mental rotation (MR) and perspective-taking abilities reflected by their score on the autism-quotient (AQ) moderated the relationship between the primed mind-sets and participants’ perspective-taking behaviour, a moderation analysis was performed using the procedures developed by Hayes and Preacher (Hayes, Citation2013; Hayes & Preacher, Citation2014). For this analysis, we employed Hayes’ PROCESS Procedure for SPSS. We construed a conceptual model (model 2) in which the primed mind-set was entered as a predictor to generated other-oriented location descriptions, and participants’ AQ and MR scores were entered as moderators. We dummy coded our predictors so that the difference-mind-set condition was used as the reference category to which the other two conditions were contrasted. We therefore construed two models, the first exploring the association between the difference- and similarity-mind-set conditions on the probability of other-oriented responses to be given (Di), and the second exploring the relationship between difference-mind-set and control condition on the probability of participants providing an other-oriented location description (Dj). We corrected for multiple tests by employing the Bonferroni correction. This entails that we used a p-value criterion of .025 to reject our null hypothesis (Hayes & Preacher, Citation2014). The bootstrapped confidence intervals were obtained over 10.000 iterations, and predictors were centred before the analysis.

The results of the one-way ANOVA were reflected in the PROCESS analyses (see ) as the mind-set condition did not have a direct effect on other-oriented location descriptions (bi = 0.15, SE = 0.52, z = 0.29, p = .770, 95% BCa CI [−0.86, 1.16]; bj = −0.42, SE = 0.52, z = −0.81, p = .420, 95% BCa CI [−1.44, 0.60]). Further, participants’ score did not moderate the relationship between the primed mind-set and the occurrence of other-oriented responses (bi = −0.28, SE = 1.47, z = −0.19, p = .848, 95% BCa CI [−3.17, 2.61]; bj = 0.18, SE = 1.25, z = 0.14, p = .887, 95% BCa CI [−2.27, 2.63]), nor did their mental rotation ability (bi = 1.55, SE = 4.21, z = 0.37, p = .713, 95% BCa CI [−6.70, 9.79]; bj = 3.03, SE = 4.59, z = 0.66, p = .510, 95% BCa CI [−5.97, 12.02]).

Table 3. Parameter estimates of mind-set on other-oriented responses moderated by AQ and MR.

Participants’ perspective-taking tendency

After the spatial perspective-taking task, participants reported the extent to which they regarded the man’s perspective during the task. Participants in the control (M = 3.92, SD = 1.23), similarity- (M = 3.85, SD = 0.99) and difference-mind-set (M = 3.85, SD = 1.16) condition reported the same perspective-taking tendency, F(2, 121) = .04, p = .958. A follow-up logistic regression revealed that participants’ self-reported perspective-taking tendency did, however, significantly predict their behaviour during the spatial perspective-taking task (b = .84, SE = .21, p < .001, 95% CI [0.46, 1.39]), representing a positive association (see ). As participants’ perspective-taking increased, so did the likelihood of them providing an other-oriented response that located the book from the man’s perspective.

Table 4. Parameter estimates of the model predicting other-oriented responses from participants’ self-reported perspective-taking tendency (PT).

Discussion

The first experiment investigated whether a mind-set that affords a focus on self-other differences rather than self-other similarities stimulates perceptual perspective-taking. We replicated the perceptual perspective-taking experiment of Todd et al. (Citation2011, experiment 1) and tried to evoke participants’ difference-mind-set by employing the visual priming method. Whereas Todd and his colleagues found that priming participants with a mind-set that focuses on differences rather than similarities increased the likelihood of participants adopting another person’s visual perspective, we did not replicate this finding. In our experiment, participants with a primed difference-mind-set were just as likely to provide a location description that oriented the target object from another’s visual perspective as participants without or with a primed similarity-mind-set. The results from participants’ self-reported perspective-taking tendency and its positive correlation to actual perspective-taking behaviour strengthen these findings. Participants who reported that they had regarded the man’s perspective during the spatial perspective-taking task had also been more likely to locate the book from the man’s perspective. Interestingly, regardless of the activation of a self-other difference-, self-other similarity- or no mind-set, these self-reported tendencies did not differ between the three conditions. This strengthens the conclusion that the picture-comparison task did not influence participants’ propensity to adopt another person’s viewpoint. This replication study also showed that perspective-taking was not dependent on perceivers’ social and cognitive ability to regard others’ perspectives (AQ-score) nor by their ability to mentally represent and rotate objects.

Our first experiment did not replicate the finding that priming perceivers with a cognitive orientation that focuses on self-other differences rather than on self-other similarities or no particular mind-set stimulates them to spontaneously adopt another person’s perspective. What factors could have contributed to the failed replication? This study directly replicated the experimental procedure and materials from Todd et al. (Citation2011), leaving no differences in how the visual priming method and spatial perspective-taking task were administered. In addition, similar to the original study, we conducted our replication among a student sample (with also a majority of female students). Although Todd et al. (Citation2011) did not report the age-range of their sample, we do not expect there to be (large) age differences between our undergraduate sample and the undergraduate sample of the original study. To our knowledge, the only difference between the original study and its replication is the cultural background of the participating students. Todd et al. (Citation2011) conducted their study among German undergraduates, whereas we invited Dutch undergraduates to participate in the study. Research has shown that cross-cultural differences might explain differences in perspective-taking (e.g. Chopik, O’Brien, & Konrath, Citation2017; Kessler, Cao, O’Shea, & Wang, Citation2014; Wu & Keysar, Citation2007). However, as the samples used in the original and replication study have a similar cultural context (e.g. House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, Citation2004), we do not expect that this difference explains the failed replication.

As in Todd et al. (Citation2011), remember that we elicited the mind-sets by the picture-comparison task in which participants noted down either the differences or similarities between picture-pairs. We could question whether this visual priming method elicited different cognitive representations or, if the priming method did elicit participants’ awareness of self-other differences, this awareness did not influence subsequent perspective-taking. The findings of participants’ self-report seem to propose that the visual priming method did not elicit differences in participants’ awareness that another perspective existed. That is, not only was participants’ awareness of the man’s perspective low (around the midpoint of the scale), this awareness did also not differ between the three conditions (control, difference-mind-set, similarity-mind-set). The ineffectiveness of the visual priming method on fostering perspective-taking has recently been supported by Eyal, Steffel, and Epley (Citation2018). In Eyal et al.’s experiment 8, 113 participants filled out Todd et al.’s (Citation2011) picture-comparison task before they completed an emotion recognition task (DANVA for faces, Nowicki & Duke, Citation1994). Not only were participants’ accuracy scores overall low (< 20%), mean accuracy scores between the control (M = 18.38, SD = 2.67), similarity-mind-set (M = 18.57, SD = 2.63) and difference-mind-set (M = 18.50, SD = 2.25) conditions did not differ. These findings combined support the argument that the visual priming method did not stimulate an awareness of differences in perspectives, thereby reducing the likelihood that another perspective was adopted.

It is likely that the visual priming method does not stimulate spontaneous perspective-taking, because this priming method is unrelated to the perspective-taking task that follows it. If participants had been put into a difference-mind-set, participants were not made aware that they could apply this notion of dissimilarity to subsequent perspective-taking. We question whether perspective-taking is stimulated when this priming method is explicitly related to the perspective-taking task. In particular, we question whether raising communicators’ awareness of a different spatial perspective does foster spatial perspective-taking, especially when this awareness is raised during the perspective-taking task itself.

Experiment 2

The second experiment examined whether explicit instructions to acknowledge another person’s viewpoint might serve as a better stimulant to incite perceivers to adopt this person’s perspective. We argue that communicators are more likely to adopt another person’s perspective once they become explicitly aware of this person’s divergent vantage point. For this, we build on the assumption that perspective-taking might benefit from communicators’ ability to inhibit an egocentric representation. Following this argument, making other-related information more accessible than self-related information should attenuate the adoption of an egocentric anchor. Indeed, recent studies have shown that highlighting certain aspects of an agent’s perspective facilitates the processing of this perspective (Elekes et al., Citation2016), and that instructing communicators to process an altercentric perspective makes them more likely to inhibit their egocentric representation (Ferguson et al., Citation2017; Samuel, Roehr-Brackin, Jelbert, & Clayton, Citation2018). In the same vein, an experimental study investigating how consumers process ambiguous reviews, Naylor, Lamberton, and Norton (Citation2011) found that highlighting consumers’ attention to think about others increased the accessibility of other-related information, thereby reducing consumers tendency to overestimate the similarity between themselves and these others (Naylor et al., Citation2011). Building on these findings, we argue that drawing communicators’ explicit attention to an altercentric perspective will make them more likely to adopt this perspective. In particular, we expect that explicit instructions to acknowledge another person’s different vantage point helps perceivers to inhibit their egocentric perspective when locating an object that is presented before them and this person. In contrast, we expect that explicitly instructing perceivers to acknowledge their egocentric perspective will make them less likely to inhibit an egocentric interpretation when judging an object’s location. To test these hypotheses, we replicated the previous experiment and intensified the perspective-awareness manipulation. Instead of visually priming self-other differences prior to the spatial perspective-taking, we raised perceivers’ awareness of self-other differences by explicitly instructing them to regard another person’s viewpoint during the spatial perspective-taking task. We explored the extent to which these explicit instructions stimulated perceivers to step in another person’s shoes.

Method

Participants and design

We recruited 80 participants from the university and randomly assigned them to one of the two perspective conditions (self-focus, other-focus). For the control condition, we used the data of the 42 participants that were recruited during experiment 1. Participants gave their informed consent before partaking in the study. The data of two participants participating in either the other-focus and self-focus condition were excluded from the analysis, due to them having prior knowledge about the actual purpose of the experiment. The age of the remaining 120 participants (32 males, 88 females, Nself-focus = 38, Nother-focus = 40, Ncontrol = 42) ranged from 17 to 36 (M = 21.39; SD = 3.01).

Procedure and materials

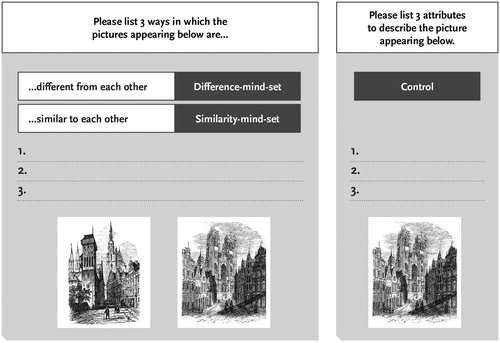

We replicated the procedure from the first experiment with one important difference: instead of priming participants with a difference- or similarity-mind-set before the spatial perspective-taking task, we explicitly stimulated participants’ self- versus other-focus during the task itself. At the start of the experiment, all participants filled out a control version of the picture-comparison task. For this control version, participants described four singular pictures of drawn houses by listing three attributes for each picture. Hereafter, the spatial perspective-taking task was administered (see ). However, before participants indicated the location of the book, they answered four explicit perception questions that were embedded among fillers. Participants were explicitly instructed to indicate how objects appeared to themselves (self-focus) or to the man in the photograph (other-focus) (see ).

For example, the first question presented participants with a scene in which a man looked at a laptop placed before him. Below this picture, participants saw two pictures of the laptop: one showing the laptop from the front (option 1) and one showing the laptop from the back (option 2). Participants in the self-focus condition answered the explicit self-perception question: “How does the laptop appear to you?”, whereas participants in the other-focus condition answered the explicit other-perception question: “How does the laptop appear to the man in the picture?”. Participants selected the option that depicted the laptop in the right rotation. To ensure the intrusiveness of the perspective-awareness training, we chose two different object rotations. Two objects could be distinguished by a clear front versus back rotation (i.e. laptop and picture frame), and two objects could be distinguished by a clear left versus right rotation (i.e. lamp and mug). If participants chose the wrong option, they had to answer the question again. Participants who answered the questions more than two times incorrectly were not asked to re-answer the question again, but they were forwarded to the rest of the questionnaire. To disallow routineness, we scrambled the options for the repeated questions. Afterwards, participants indicated the location of the book. We repeated the coding procedure from the first experiment and excluded four responses (Nself-focus = 1, Nother-focus = 3, Ncontrol = 4) that located the book “in the middle” or “on the upper side”.

Training performance

The low error-rate (N = 5) across both perspective-focus conditions showed that the explicit perception instructions helped participants to acknowledge the situation from their own or from the man’s point of view. Interestingly, perspective-focus errors mainly occurred in the other-focused condition in which participants indicated how the objects appeared to the man in the picture (Nother-focus = 4), in comparison to the self-focused condition in which they indicated how the objects appeared to themselves (Nself-focus = 1). One participant in the self-focused condition made the same error (for the same object) twice, whereas the other participants only made the error once.

The spatial perspective-taking task was followed by recording participants’ self-reported perspective-taking tendency (α = .78; see ), and their mental rotation (MR) and perspective-taking (AQ, α = .91) abilities. In the MR task, participants gave accurate responses on 80% of the trials (Mother-focus = 0.80, SD = 0.02; Mself-focus = 0.83, SD = 0.02).

After collecting their demographics, participants were thanked, debriefed and given a small remuneration for their participation. The ethics review committee of the Tilburg School of Humanities and Digital Sciences has approved this experiment to be in full compliance with the relevant codes of experimentation and legislation.

Results

The dataset of this experiment can be accessed via osf.io/by47d. The mean proportions of other-oriented location descriptions as a function of the perspective-focus condition are presented in .

Table 5. Mean percentage of other-oriented location descriptions as a function of condition.

Participants oriented the object’s location from the man’s perspective the most in the other-focus condition (M = .51, SD = .51), followed by the control (M = .39, SD = .50) and the self-focus (M = .16, SD = .37) conditions.

Moderation analysis

As in the first experiment, we construed a conceptual model (PROCESS model 2) that investigated the relationship between the perspective-focus condition and the other-oriented responses, while controlling for participants’ mental rotation (MR) and perspective-taking (AQ) abilities. We dummy coded our predictors and construed three models: control vs. self-focus (Di), control vs. other-focus (Dj), self-focus vs. other-focus (Dk). We employed the Bonferroni correction to correct for multiple tests (α ≤ .017). The parameter estimates of the conceptual models are presented in .

Table 6. Parameter estimates of condition on other-oriented responses moderated by AQ and MR.

Results showed that the direct effect of the explicit self- versus other-focus on oriented responses was significant (bk = 1.69, SE = .59, z = 2.84, p = .005, 95% BCa CI [0.52, 2.85]). However, the direct effect of the control versus self-focus condition (bi = −1.56, SE = 0.82, z = −1.89, p = .0585, 95% BCa CI [−3.17, 0.06]), and the control versus other-focus condition (bj = 0.11, SE = 0.71, z = 0.15, p = .880, 95% BCa CI [−1.28, 1.49]) on other-oriented responses were both non-significant.

A follow-up analysis in which we compared the self-focus and other-focus conditions revealed that other-focused participants (M = .51, SD = .51) were 5.4 times more likely to provide a location description that oriented the book from the man’s perspective, than self-focused participants (M = 0.16, SD = .37), χ2 (1) = 10.21, p = .001, representing a medium association (Cramer’s V = .37).

Participants’ AQ score did not moderate the relationship between the explicit perspective-focus condition and the occurrence of other-oriented responses (bi = 0.23, SE = 1.17, z = 0.19, p = .847, 95% BCa CI [−2.06, 2.51]; bj = 0.27, SE = 1.08, z = 0.25, p = .800, 95% BCa CI [−1.84, 2.39]; bk = 0.05, SE = 1.47, z = 0.03, p = .973, 95% BCa CI [−2.83, 2.93]), nor did participants’ mental rotation ability (bi = 9.62, SE = 5.63, z = 1.71, p = .087, 95% BCa CI [−1.41, 20.65]; bj = 4.87, SE = 4.11, z = 1.18, p = .237, 95% BCa CI [−3.20, 12.93]; bk = −4.75, SE = 5.29, z = −0.90, p = .369, 95% BCa CI [−15.13, 5.62]).

Participants’ perspective-taking tendency

Participants’ self-reported perspective-taking tendency significantly differed between the three conditions, Welch’s F(2, 75.92) = 49.79, p < .001. Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons revealed that self-focused participants (M = 3.37, SD = .68) reported a significant lower perspective-taking tendency than the other-focused participants (M = 5.15, SD = .88), p < .001, and the participants in the control condition (M = 3.92, SD = 1.23), p = .04. Participants in the control condition also reported a lower perspective-taking tendency than the other-focused participants, p < .001.

In a follow-up logistics regression analysis, we examined the extent to which the self-reported perspective-taking tendency of the other-focused and self-focused participants predicted their perspective-taking during the spatial perspective-taking task. The analysis revealed a significant positive relation between participants’ perspective-taking tendency and other-oriented location descriptions (b = 1.05, SE = 0.28, p < .001, 95% CI [0.62, 1.73]; see ).

Discussion

The second experiment investigated the influence of explicit perception instructions on perceivers’ tendency to adopt another person’s viewpoint. Results showed that perceivers who were explicitly instructed to acknowledge another person’s perspective were more likely to spontaneously adopt this person’s perspective than those stimulated to be self-focused. Other-focused participants also reported a higher perspective-taking tendency than self-focused and control participants, and this tendency was positively correlated to actual perspective-taking behaviour. Those with a higher self-reported perspective-taking tendency had also been more likely to adopt another person’s viewpoint.

Interestingly, in the control condition in which perceivers did not receive explicit self- or other-perception instructions, the majority (61%) located the object on the basis of their own spatial perspective. Explicit other-focus instructions did not decrease this egocentric anchoring tendency. That is, participants in the control condition were just as likely to provide an other-oriented spatial description as other-focused and self-focused participants. This finding supports the argument that an egocentric approach is the most natural response while judging social situations (e.g. Ames, Citation2005; Epley et al., Citation2004; Levelt, Citation1989 as cited in Schober, Citation1993; Tversky & Hard, Citation2009). This experiment showed that enhancing the accessibility and, thus, saliency of another person’s different perspective compared to a baseline in which this increase was absent did not reduce egocentric anchoring during spatial perspective-taking.

General discussion

Although perspective-taking is considered to be a central component for successful social functioning, research showed that perceivers’ often fail to accurately acknowledge another person’s different vantage point. One important reason as to why perceivers often do not engage in perspective-taking is because their egocentric perception biases (Birch & Bloom, Citation2007; Keysar et al., Citation1998) their perspective-judgments. That is, the accessibility of perceivers’ private cognitions causes perceivers to first interpret the other’s perspective on the basis of their own and, subsequently, adjust away from this egocentric interpretation in cognitive effortful steps (Epley et al., Citation2004). However, because perceivers’ private perspective is most salient, perceivers find it hard to adjust their egocentrism in order to form an interpretation that more accurately reflects another person’s perspective. Perspective-adjustments are, therefore, often insufficient, resulting in perceivers being likely to judge social situations from their own perspective instead of from someone else’s.

The current study investigated what perceivers need in order to overcome this egocentric anchoring during spatial perspective-taking. In the first experiment, we built on the assumption that perceivers’ awareness of differences in perspectives (Decety & Sommerville, Citation2003; Santiesteban et al., Citation2012; Todd et al., Citation2011) might stimulate them to describe an object location from another person’s vantage point. We addressed this assumption by directly replicating the experimental design of Todd et al. (Citation2011). In particular, we tested Todd et al.’s (Citation2011) hypothesis that perceivers primed with a cognitive orientation to draw a distinction between the self and the other would be more likely to engage in perspective-taking than the perceivers primed with a cognitive orientation to focus on similarities between the self and the other. Our findings did not support this hypothesis and thereby failed to replicate Todd et al. (Citation2011). In contrast to Todd et al. (Citation2011), the individuals in our study were all very likely to locate the object from their own spatial perspective, regardless of their primed cognitive orientation. This failed replication falls in line with recent findings by Eyal et al. (Citation2018) who also administered Todd et al.’s (Citation2011) priming method in order to stimulate perspective-taking. In line with our findings, Eyal et al. (Citation2018) showed that a primed difference-mind-set—in contrast to a primed similarity-mind-set and a baseline—did not stimulate individuals’ recognition of emotional expressions (DANVA; Nowicki & Duke, Citation1994). Hence, these findings underline the importance of (direct) replications in order to further our understanding of the phenomenon being examined (e.g. Moonesinghe, Khoury, & Janssens, Citation2007; Open Science Collaboration, Citation2012; Simons, Citation2014; Zwaan, Etz, Lucas, & Donnellan, Citation2018).

The second experiment investigated whether perceivers’ explicit awareness of another person’s perspective fosters perspective-taking. We addressed this question by explicitly instructing perceivers to regard visual scenes from the perspective of a photographed man before they located an object that was placed before the man in the picture. Before perceivers located the target object, they were explicitly instructed to acknowledge the man’s different perspective (other-focus condition) or to acknowledge their egocentric viewpoint (self-focus condition). Findings showed that other-focused perceivers were more likely to inhibit an egocentric interpretation and to locate the object from the man’s perspective than self-focused perceivers. However, the findings of the second experiment also show that the majority of perceivers were very likely to locate the object from their egocentric spatial perspective. That is, when the spatial responses were contrasted to the control condition in which perceivers did not receive explicit perception instructions, explicit other-focus instructions did not increase perceivers’ perspective-taking, nor did the explicit self-focus instructions reduce perceivers’ perspective-taking.

Important to note is that the spatial perspective-taking task administered in this study tapped into spontaneous perspective-taking. That is, we examined the extent to which perceivers spontaneously let go of their predominant egocentric frame of reference (Tversky & Hard, Citation2009) by adopting another’s frame of reference because they had been primed with a specific cognitive orientation (experiment 1) or because they had been primed to focus on a different perspective (experiment 2). In this sense, the spatial perspective-taking task differed from tasks that measure perspective-taking accuracy (such as the Director Task; Epley et al., Citation2004) in which egocentric responses are termed to be inaccurate. In the spatial perspective-taking task administered in this study, egocentric responses were not termed to be inaccurate nor were altercentric responses termed to be accurate. Egocentric responses in the spatial perspective-taking task showed that people stuck with their predominant frame of reference, whereas altercentric responses showed that people inhibited an egocentric response and prioritised another frame of reference by adopting this frame (spontaneously).

In addition, even though the majority of speakers used their egocentric perspective as a spatial anchor point to describe the object’s location, this does not imply that these perceivers did not recognise that the object, from another person’s perspective, was located on the other side of the table. For instance, most of participants’ location descriptions not only included a specific reference point (e.g. “on my right side”, “on the left side of the man in the picture”), participants’ responses sometimes also included both perspectives (e.g. “on my right side, but on the left side of the man in the picture”). Recall that we coded the perspective that was mentioned first by participants (following Todd et al. (Citation2011), and Tversky and Hard (Citation2009)). However, answers that included both participants’ self- as the other’s perspective clearly indicated that participants were aware that different perspectives were at stake while describing the object’s location. In addition, the low error rate of the perspective-awareness training in the second experiment clearly indicates that speakers were able to regard the situation from the other person’s vantage point. The explicit other-focus instructions during the perspective-awareness training thus helped perceivers to acknowledge the other person’s different spatial perspective. However, when we contrast the two perspective-focus condition to the baseline, it appears that an explicit focus on another person’s different perspective did not influence how speakers would actually describe the situation that is presented before them. In addition, findings of both experiments show that perceivers across the various conditions (difference-mind-set, similarity-mind-set, self-focus, other-focus and control) were very likely to locate the object from their egocentric spatial perspective. These results support previous findings that speakers prefer to describe spatial relations from their egocentric point of view (Levelt, Citation1989 as cited in Schober, Citation1993; Tversky & Hard, Citation2009). Our findings further suggest that enhancing speakers’ attention to another person’s different vantage point does not stimulate spontaneous perspective-taking.

It could be questioned whether and explicit awareness of self-other perception differences encourages perspective-taking when the demand to engage in perspective-taking is emphasised by the task. In the experiments presented in this paper, inferring the other person’s point of view was not a crucial component for successfully completing the task. It could be the case that an explicit awareness of self-other differences encourages perspective-taking behaviour when it is necessary to adopt another person’s perspective. In addition, some social situations cause perceivers to be fixed onto their own egocentric interpretations and beliefs (Thompson, Nadler, & Lount, Citation2006). Especially in the case of interpersonal conflict, interlocutors find it hard to let go of pre-established beliefs and to allow for an interpretation that is in line with another person’s perspective. Results of the second experiment seem to suggest that instructing to take over the perspective of their counterpart might stimulate disputants to see past their initial egocentric interpretation. In this sense, explicit instructions, could not only lead to a more correct understanding of self-other differences, but they might also stimulate disputants to see similarities—of which they first thought they did not exist—between themselves and their counterpart. Especially in the case of conflict, failing to see similarities in viewpoints, thoughts and wishes reduces disputants’ chance to resolve their conflict (Thompson et al., Citation2006). Future research might investigate how explicit perspective-taking instructions might help interlocutors to update existing false-beliefs. Answers to this interesting question will shed more light on the precise workings of the self-other mechanism that underlies perspective-taking.

Conclusion

The findings of the two studies presented in this paper support the existence of perceivers’ egocentricity bias and its robustness. Neither a primed mind-set focusing on self-other differences (experiment 1) nor explicit and repeated instructions to acknowledge the visual perspective of another person (experiment 2) reduced participants’ egocentric anchoring tendency. Speakers were very likely to interpret the situation from their own visual perspective, even though they were made aware of the other person’s different point of view.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Debby Damen http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6116-0142

Notes

1 This has also been referred to as “level-2” visual perspective-taking (see Flavell, Everett, Croft, & Flavell, Citation1981).

References

- Ames, D. R. (2004). Inside the mind-readers’ toolkit: Projection and stereotyping in mental state inference. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 340–353.

- Ames, D. R. (2005). Everyday solutions to the problem of other minds: Which tools are used when? In B. F. Malle, & S. D. Hodges (Eds.), Other minds: How humans bridge the divide between self and others (pp. 158–173). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Apperly, I. A., Back, E., Samson, D., & France, L. (2008). The cost of thinking about false beliefs: Evidence from adults’ performance on a non-inferential theory of mind task. Cognition, 106(3), 1093–1108.

- Apperly, I. A., Caroll, D. J., Samson, D., Humphreys, G. W., Qureshi, A., & Moffitt, G. (2010). Why are there limits on theory of mind use? Evidence from adults’ ability to follow instructions from an ignorant speaker. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 63, 1201–1217.

- Aron, A., Aron, E. N., Tudor, M., & Nelson, G. (1991). Close relationships as including the other in the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 241–253.

- Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001). The ‘reading the mind in the eyes’ test-revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 241–251.

- Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 5–17.

- Barr, D. J., & Keysar, B. (2005). Mindreading in an exotic case: The normal adult human. In B. F. Malle, & S. D. Hodges (Eds.), Other minds: How humans bridge the divide between self and others (pp. 271–283). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Birch, S. A., & Bloom, P. (2007). The curse of knowledge in reasoning about false beliefs. Psychological Science, 18(5), 382–386.

- Boothby, E. J., Smith, L. K., Clark, M. S., & Bargh, J. A. (2017). The world looks better together: How close others enhance our visual experiences. Personal Relationships, 24(3), 694–714.

- Brown, J. J., & Reingen, P. H. (1987). Social ties and word-of-mouth referral behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 14, 350–362.

- Brown-Schmidt, S. (2009). The role of executive function in perspective taking during online language comprehension. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16(5), 893–900.

- Brown-Schmidt, S., Gunlogson, C., & Tanenhaus, M. K. (2008). Addressees distinguish shared from private information when interpreting questions during interactive conversation. Cognition, 107(3), 1122–1134.

- Brown-Schmidt, S., & Hanna, J. E. (2011). Talking in another person’s shoes: Incremental perspective-taking in language processing. Dialogue and Discourse, 2, 11–33.

- Brown-Schmidt, S., & Tanenhaus, M. K. (2008). Real-time investigation of referential domains in unscripted conversation: A targeted language game approach. Cognitive Science, 32, 643–684.

- Brunyé, T. T., Ditman, T., Giles, G. E., Mahoney, C. R., Kessler, K., & Taylor, H. A. (2012). Gender and autistic personality traits predict perspective-taking ability in typical adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(1), 84–88.

- Bukowski, H., & Samson, D. (2017). New insights into the inter-individual variability in perspective taking. Vision, 1(1), 1–19.

- Byrne, D. (1961). Interpersonal attraction and attitude similarity. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62(3), 713–715.

- Byrne, D., & Nelson, D. (1965). The effect of topic importance and attitude similarity-dissimilarity on attraction in a multistranger design. Psychonomic Science, 3(1–12), 449–450.

- Carlson, S. M., & Moses, L. J. (2001). Individual differences in inhibitory control and children’s theory of mind. Child Development, 72(4), 1032–1053.

- Carlson, S. M., Moses, L. J., & Claxton, L. J. (2004). Individual differences in executive functioning and theory of mind: An investigation of inhibitory control and planning ability. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 87(4), 299–319.

- Cheek, N. N. (2015). Taking perspective the next time around. Commentary on: “Perceived perspective taking: When others walk in our shoes”. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–3.

- Chopik, W. J., O’Brien, E., & Konrath, S. H. (2017). Differences in empathic concern and perspective taking across 63 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(1), 23–38.

- Cooper, L. A., & Shepard, R. N. (1973). The time required to prepare for a rotated stimulus. Memory & Cognition, 1, 246–250.

- Damen, D., van der Wijst, P., van Amelsvoort, M., & Krahmer, E. (2018). Perspective-taking in referential communication: Does stimulated attention to addressees’ perspective influence speakers’ reference production? Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 48(2), 257–288.

- Decety, J., & Sommerville, J. A. (2003). Shared representations between self and others: A social cognitive neuroscience view. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7, 527–533.

- Elekes, F., Varga, M., & Király, I. (2016). Evidence for spontaneous level-2 perspective taking in adults. Consciousness and Cognition, 41, 93–103.

- Elfenbein, H. A., & Ambady, N. (2002). On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 203–235.

- Epley, N., Keysar, B., Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2004). Perspective taking as egocentric anchoring and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 327–339.

- Epley, N., Morewedge, C. K., & Keysar, B. (2004). Perspective taking in children and adults: Equivalent egocentrism but differential correction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(6), 760–768.

- Eyal, T., Steffel, M., & Epley, N. (2018). Perspective mistaking: Accurately understanding the mind of another requires getting perspective, not taking perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(4), 547–571.

- Ferguson, H. J., Apperly, I., & Cane, J. E. (2017). Eye tracking reveals the cost of switching between self and other perspectives in a visual perspective-taking task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70(8), 1646–1660.

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140.

- Flavell, J. H., Everett, B. A., Croft, K., & Flavell, E. R. (1981). Young children’s knowledge about visual perception: Further evidence for the level 1–level 2 distinction. Developmental Psychology, 17, 99–103.

- Hanna, J. E., & Tanenhaus, M. K. (2004). Pragmatic effects on reference resolution in a collaborative task: Evidence from eye movements. Cognitive Science, 28, 105–115.

- Hanna, J. E., Tanenhaus, M. K., & Trueswell, J. C. (2003). The effects of common ground and perspective on domains of referential interpretation. Journal of Memory and Language, 49, 43–61.

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Publications, Inc.

- Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(3), 451–470.

- Heller, D., Gorman, K. S., & Tanenhaus, M. K. (2012). To name or to describe: Shared knowledge affects referential form. Topics in Cognitive Science, 4, 290–305.

- Heller, D., Grodner, D., & Tanenhaus, M. K. (2008). The role of perspective in identifying domains of reference. Cognition, 108, 831–836.

- Hoekstra, R. A., Vinkhuyzen, A. A., Wheelwright, S., Bartels, M., Boomsma, D. I., Baron-Cohen, S., & van der Sluis, S. (2011). The construction and validation of an abridged version of the autism-spectrum quotient (AQ-Short). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(5), 589–596.

- Horton, W. S., & Keysar, B. (1996). When do speakers take into account common ground? Cognition, 59(1), 91–117.

- House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

- Huttenlocher, J., & Presson, C. C. (1973). Mental rotation and the perspective problem. Cognitive Psychology, 4, 277–299.

- Kaland, C., Krahmer, E., & Swerts, M. (2014). White bear effects in language production: Evidence from the prosodic realization of adjectives. Language and Speech, 57(4), 470–486.

- Kessler, K., Cao, L., O’Shea, K. J., & Wang, H. (2014). A cross-culture, cross-gender comparison of perspective taking mechanisms. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281, 1–9.

- Keysar, B., Barr, D. J., & Horton, W. S. (1998). The egocentric basis of language use: Insights from a processing approach. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 7(2), 46–49.

- Keysar, B., Lin, S., & Barr, D. J. (2003). Limits on theory of mind use in adults. Cognition, 89(1), 25–41.

- Krueger, J., & Clement, R. W. (1994). The truly false consensus effect: An ineradicable and egocentric bias in social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 596–610.

- Levelt, W. J. M. (1989). Speaking: From intention to articulation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Lin, S., Keysar, B., & Epley, N. (2010). Reflexively mindblind: Using theory of mind to interpret behavior requires effortful attention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(3), 551–556.

- Mainwaring, S. D., Tversky, B., Ohgishi, M., & Schiano, D. J. (2003). Descriptions of simple spatial scenes in English and Japanese. Spatial Cognition and Computation, 3(1), 3–42.

- Maner, J. K., Luce, C. L., Neuberg, S. L., Cialdini, R. B., Brown, S., & Sagarin, B. J. (2002). The effects of perspective taking on motivations for helping: Still no evidence for altruism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(11), 1601–1610.

- Mitchell, J. P. (2009). Inferences about mental states. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 364(1521), 1309–1316.

- Mitchell, J. P., Macrae, C. N., & Banaji, M. R. (2006). Dissociable medial prefrontal contributions to judgments of similar and dissimilar others. Neuron, 50(4), 655–663.

- Moonesinghe, R., Khoury, M. J., & Janssens, A. C. (2007). Most published research findings are false—but a little replication goes a long way. PLoS Medicine, 4(2), 218–221.

- Mussweiler, T. (2001). ‘Seek and yes hall find’: Antecedents of assimilation and contrast in social comparison. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 499–509.

- Mussweiler, T. (2003). Comparison processes in social judgment: Mechanisms and consequences. Psychological Review, 110, 472–489.

- Nadig, A. S., & Sedivy, J. C. (2002). Evidence of perspective-taking constraints in children’s on-line reference resolution. Psychological Science, 13(4), 329–336.

- Naylor, R. W., Lamberton, C. P., & Norton, D. A. (2011). Seeing ourselves in others: Reviewer ambiguity, egocentric anchoring, and persuasion. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(3), 617–631.

- Nilsen, E. S., & Graham, S. A. (2009). The relations between children’s communicative perspective-taking and executive functioning. Cognitive Psychology, 58(2), 220–249.

- Nowicki, S., Jr., & Duke, M. P. (1994). Individual differences in the nonverbal communication of affect: The diagnostic analysis of nonverbal accuracy scale. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 18, 9–35.

- Open Science Collaboration. (2012). An open, large-scale, collaborative effort to estimate the reproducibility of psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 657–660.

- Qureshi, A. W., Apperly, I. A., & Samson, D. (2010). Executive function is necessary for perspective selection, not Level-1 visual perspective calculation: Evidence from a dual- task study of adults. Cognition, 117(2), 230–236.

- Roberts, R. J., & Aman, C. J. (1993). Developmental differences in giving directions: Spatial frames of reference and mental rotation. Child Development, 64(4), 1258–1270.

- Ryskin, R. A., Benjamin, A. S., Tullis, J., & Brown-Schmidt, S. (2015). Perspective-taking in comprehension, production, and memory: An individual differences approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(5), 898–915.

- Samson, D., Apperly, I. A., Braithwaite, J. J., Andrews, B. J., & Bodley Scott, S. E. (2010). Seeing it their way: Evidence for rapid and involuntary computation of what other people see. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 36(5), 1255–1266.

- Samuel, S., Roehr-Brackin, K., Jelbert, S., & Clayton, N. S. (2018). Flexible egocentricity: Asymmetric switch costs on a perspective-taking task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. doi: 10.1037/xlm0000582

- Santiesteban, I., White, S., Cook, J., Gilbert, S. J., Heyes, C., & Bird, G. (2012). Training social cognition: From imitation to theory of mind. Cognition, 122(2), 228–235.

- Savitsky, K., Keysar, B., Epley, N., Carter, T., & Swanson, A. (2011). The closeness-communication bias: Increased egocentrism among friends versus strangers. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 269–273.

- Schneider, D., Nott, Z. E., & Dux, P. E. (2014). Task instructions and implicit theory of mind. Cognition, 133(1), 43–47.

- Schneider, D., Slaughter, V. P., & Dux, P. E. (2017). Current evidence for automatic theory of mind processing in adults. Cognition, 162, 27–31.

- Schober, M. F. (1993). Spatial perspective-taking in conversation. Cognition, 47(1), 1–24.

- Schurz, M., Kronbichler, M., Weissengruber, S., Surtees, A., Samson, D., & Perner, J. (2015). Clarifying the role of theory of mind areas during visual perspective taking: Issues of spontaneity and domain-specificity. NeuroImage, 117, 386–396.

- Simons, D. J. (2014). The value of direct replication. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9, 76–80.

- Simons, H. W., Berkowitz, N. N., & Moyer, R. J. (1970). Similarity, credibility, and attitude change: A review and a theory. Psychological Bulletin, 73(1), 1–16.

- Simpson, A. J., & Todd, A. R. (2017). Intergroup visual perspective-taking: Shared group membership impairs self-perspective inhibition but may facilitate perspective calculation. Cognition, 166, 371–381.

- Stotland, E. (1969). Exploratory investigations of empathy. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 271–314). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Stroebe, W., Insko, C. A., Thompson, V. D., & Layton, B. D. (1971). Effects of physical attractiveness, attitude similarity, and sex on various aspects of interpersonal attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18(1), 79–91.

- Surtees, A. D., & Apperly, I. A. (2012). Egocentrism and automatic perspective taking in children and adults. Child Development, 83(2), 452–460.

- Surtees, A., Samson, D., & Apperly, I. (2016). Unintentional perspective-taking calculates whether something is seen, but not how it is seen. Cognition, 148, 97–105.

- Thompson, L., Nadler, J., & Lount, R. B., Jr. (2006). Judgmental biases in conflict resolution and how to overcome them. In M. Deutsch, P. T. Coleman, & E. C. Marcus (Eds.), The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 243–267). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Todd, A. R., Hanko, K., Galinsky, A. D., & Mussweiler, T. (2011). When focusing on differences leads to similar perspectives. Psychological Science, 22(1), 134–141.

- Tversky, B., & Hard, B. M. (2009). Embodied and disembodied cognition: Spatial perspective taking. Cognition, 110, 124–129.

- Wardlow, L. (2013). Individual differences in speakers’ perspective taking: The roles of executive control and working memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20(4), 766–772.

- Wardlow Lane, L. W., & Ferreira, V. S. (2008). Speaker-external versus speaker-internal forces on utterance form: Do cognitive demands override threats to referential success? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 34(6), 1466–1481.

- Wardlow Lane, L. W., Groisman, M., & Ferreira, V. S. (2006). Don’t talk about pink elephants! Speakers’ control over leaking private information during language production. Psychological Science, 17(4), 273–277.

- Wardlow Lane, L. W., & Liersch, M. J. (2012). Can you keep a secret? Increasing speakers’ motivation to keep information confidential yields poorer outcomes. Language and Cognitive Processes, 27(3), 462–473.

- Wu, S., & Keysar, B. (2007). The effect of culture on perspective taking. Psychological Science, 18(7), 600–606.

- Zwaan, R. A., Etz, A., Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2018). Making replication mainstream. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 41, 1–50.