ABSTRACT

Comics journalism bears testimony to different kinds of stories in the context of humanitarian witnessing, including personal relationships to the people who flee conflicts and the connections we make through languages. Over the latest years, the number of refugees and other migrants who crossed the Mediterranean in search of protection or a better life in Europe increased considerably. By focusing on two Italian examples of comics journalism, this article aims to answer the question: how does Italian comics journalism contribute to shaping our understanding of the crossing of borders in the Mediterranean region? By ‘our,’ I mean people living in Europe and the Global North more broadly. Grounding the analysis in the context of theoretical comics approaches, the first section explores the storylines as it situates the work of the authors within a precise socio-political framework. The second section discusses the documentary significance of both comics within the European discourse that tend to silence people on the move. After highlighting the potential of the decolonising multilingualism approach (Phipps Citation2019) for Comics Studies, the conclusion calls for greater exchange between journalism, migration studies, and comics scholarship.

Introduction

Over the past decade, the number of refugees and other migrantsFootnote1 who crossed the Mediterranean in search of protection or a better life in Europe increased considerably (International Organization for Migration Citation2020a). Many people left their home countries as a consequence of ongoing conflicts in Africa and the Middle East, whereas many of those who decided to leave for economic reasons were subsequently forced to move due to conflicts in Libya and other places (Crawley et al. Citation2016a). Considering its geographical position, Italy was one of the countries at the frontline of the Mediterranean ‘crisis’ (UNHCR Citation2015). Italy experienced migration from the countries bordering the southern Mediterranean for a long time. Yet, the crossings are part of the (largely forgotten) legacy of European engagement in colonial projects in Africa (Merrill Citation2018). The contemporary political and media discourse has often portrayed refugees and other migrants as a threat to Global North’s economy, cultures, and security, widely disregarding the perspectives of those personally involved. By focusing on two recent examples of Italian comics journalism dealing with migrant reception at borders and in-country – respectively, Salvezza (‘Salvation’, Rizzo and Bonaccorso Citation2018) and …A Casa Nostra. Cronaca da Riace (‘ …In our own country. Chronicles from Riace’, Rizzo and Bonaccorso Citation2019) – this article aims to answer the question: how does Italian comics journalism contribute to shaping our understanding of the crossing of borders in the Mediterranean region? By ‘our,’ I mean people living in Europe and the Global North more broadly. Both books are published by Feltrinelli Comics, an editorial line completely dedicated to comics and graphic novels inaugurated in 2018 by Feltrinelli Editore, a major publisher in Italy with its powerhouse of publicity and distribution, including translation in other languages. By leveraging the importance of authorial intentions and semi-structured interviews informing the discussion, this article aims to (i) highlight the contribution of Italian comics journalism to the transnational media landscape in the context of the so-called European ‘migration crisis’; (ii) offer an interdisciplinary perspective on the potential of comics as a medium for strategies to decolonising knowledge, including discussions on languages and translations; (iii) feature to the Anglophone field of Comics Studies the expanding strand of contemporary Italian comics’ production that challenges dominant migration narratives – mostly framed in terms of security issues and restrictive border policies – by voicing individual lived experiences of refugees and other migrants.

This article is structured in two main parts. The first section introduces the methodological approach to inquiry adopted by the authors of the two comics, situates their work within a precise socio-political framework, and explores the main themes and features of the storylines. The second section discusses the significance of both comics as documentary works and considers the knowledge they convey against the backdrop of European media that tend to silence the voice of refugees and other migrants. After highlighting the potential of the decolonising multilingualism approach (Phipps 2019) for Comics Studies, the conclusion calls for greater exchange between journalism, migration studies, and comics scholarship.

Foregrounding lived experiences of migration

Media outlets operating in countries on both sides of the Mediterranean have not been covering migration accurately and have often failed to provide a fair and balanced view of migration (International Centre for the Migration Policy Development Citation2017). The comics discussed here address this gap by conveying personal narratives often neglected in the mainstream media and reminding the readers of the individual stories obscured in data-driven reports. Salvezza is an ethnographic account of the rescue operations in the central Mediterranean migrant route to Italy and … A Casa Nostra. Cronaca da Riace investigates how people with a migrant background in the south of Italy cope with the precarious conditions of their daily lives. The authors – journalist Marco Rizzo and illustrator Lelio Bonaccorso – teamed up several times to produce investigative graphic narratives appealing to a varied readership (Rizzo and Bonaccorso Citation2009; Citation2011a and Citation2011b; Citation2012; Citation2014a; Citation2014b; Citation2015; Citation2016; Citation2018; Citation2019), including stories of migration (Rizzo and Bonaccorso Citation2014b; 2015; Rizzo and Bonaccorso Citation2016). Being produced and published within a landscape of restrictive anti-immigrant policies promoted by the right-wing populist party Lega Nord – strengthened by the nationalist leader Matteo Salvini in the position of Italian Minister of Interior – both comics are works of critical inquiry with documentary value and historical significance. Their narrative provides insights into stories and lived experiences, offering the opportunity to understand differently the complex dynamics of migration across the Mediterranean region.

Salvezza

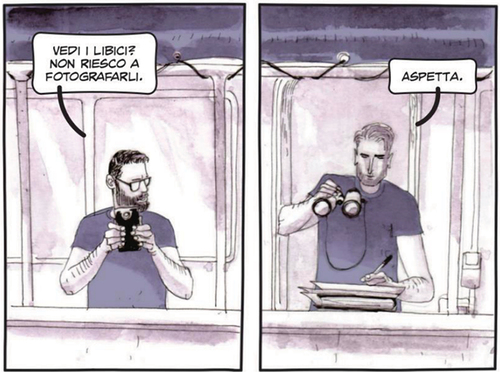

Salvezza (Citation2018) documents a three-week ethnography fieldwork conducted on the rescue vessel Aquarius in November 2017 in the central Mediterranean. According to the Law of the Sea, all vessels have the duty to rescue people in distress at sea. This is a ‘time-honoured rule of international law, is as applicable today as ever, during both peacetime and wartime’ (Papanicolopulu Citation2017: 513). Search and Rescue (SAR) operations can be performed by humanitarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) upon authorisation of the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre based in Rome. The maritime-humanitarian NGO SOS Mediterranée operated the Aquarius in partnership with the humanitarian NGO Médecins Sans Frontières, who provided medical aid onboard. Salvezza is the first report from a rescue vessel in comics form and drawing in-situ was a unique tool to gather data on several occasions. illustrates the complementary approaches of photography and drawing that the authors adopted to document the mission of SOS Mediterranée: Bonaccorso (panel on the right) used binoculars to draw a Libyan boat which Rizzo (panel on the left) could not photograph due to excessive distance. The boat was firstly identified as a patrol vessel, and yet, after examining the illustration, it turned out to be a Libyan warship and was later reproduced in the comic.Footnote2

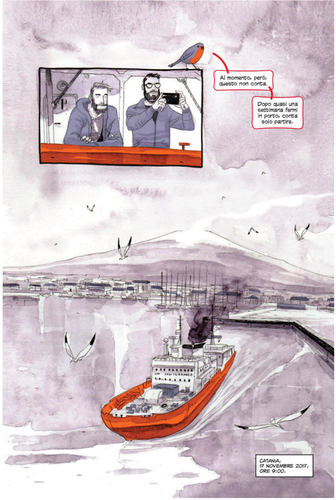

The comic documents the vessel as it sets out from the port of Catania, Sicily, through four SAR operations in international waters – which saved around a thousand people. The authors’ onboard role was not simply to observe and document the mission. They were trained to provide support to the members of the crew, including during rescue operations. Different narrative layers reflect the complexity of life onboard with short anecdotes, voices from different people – SAR staff, medical staff, cultural mediators, rescued people, authors’ self-reflections about their own positionality as reporters – and data about migration flows. To deliver this wealth of perspectives, the authors decided to offer a proper bird’s-eye view of the life onboard. By using the rhetorical device of prosopopoeia,Footnote3 they granted a robin the ability to tell the story and it does so from the viewpoint of an omniscient narrator (: Bonaccorso, Rizzo, and the robin sailing off from Catania). The robin, however, is not entirely a narrative invention. A robin was truly spotted onboard on the very first days of the mission.Footnote4 In the comic, the robin is symbolically the first to find sanctuary on the deck of the Aquarius. The bird flew to the vessel to seek refuge from the attack of a seagull, getting onboard shortly before Rizzo and Bonaccorso.

The Aquarius stands out for its vividly orange-coloured hull. This hue of orange is called ‘safety orange’ and sets objects apart from their surroundings by contrasting with the azure of the sky. The significance of the colour orange in the whole narrative takes on the meaning of hope and salvation. Safety orange is the colour of life vests, the robin itself is partly coloured in orange, and so is the pencil that Bonaccorso packs with other drawing materials. This is particularly significant as the pencil served to draw the story for the readership and facilitate communication with the rescued people (). Bonaccorso used drawings to both foster positive interaction and capture visual data effectively. Sitting on the deck, he made drawings as people gathered around him spontaneously, queueing to be portrayed (). This careful approach aimed at attracting the interest of the people onboard, and the use of pencil and paper, compared to more intimidating recording devices, made rescued people more comfortable to engage in conversation. This practice expands our understanding of comics-based research and shifts ‘focus on what comics do’ (Kuttner et al. Citation2017, 398) rather than what comics are, a matter of perennial debate in comics scholarship. The work of Rizzo and Bonaccorso developed on the pioneering work of anthropologists who used drawings to collect data (Newman Citation1998; Ramos Citation2000, Citation2004) and paved the way to comics-based research. Drawings were an ‘integral part of the data collection process’ (Kuttner et al. Citation2017, 397), and Salvezza is informed by a unique ‘camera roll’Footnote5 made of sketches, portraits, and personal stories of migration. As artistic representations that capture essential aspects of the people depicted, portraits were especially relevant for those who experienced tortures and trauma in Libyan prisons. The linkage between the use of torture and the erasure of the self is well documented across history and disciplines (Hárdi and Kroó Citation2011; Macias Citation2013; Silove Citation1999). Here, the portraits included pictorial representations with the names of those portrayed. The use of portraits restored dignity to the identities of the people depictedFootnote6 and contributed to ‘push deeper into the medium’s possibility’ (Kuttner et al. Citation2017, 397).

In Salvezza, watercolour is mainly applied with rapid brushstrokes, which convey a sense of urgency, whereas the use of different palettes indicates different temporal sequences. Scenes coloured in shades of grey illustrate the present, and shades of blue depict memories of a violent, traumatic past (). Interestingly, the choice to use complementary colours such as orange and blue reflects the contrast between feelings of hope for a better future and sadness and sorrow, often associated with shades of blue. The book opens with a short prologue where Abraham, a young man fleeing Eritrea, recounts the abuses that he and his wife Ruta suffered as they travelled through Sudan to reach Libya. Men and women were separated, and men could hear the screams of women who were being abused. The whole story of Abraham and Ruta will be revealed at the end, in a circular structure that ‘wraps around’ other migrant stories told aboard the Aquarius.Footnote7

A parallel strand of the narrative of Salvezza is the life onboard, of which the reader is given a glimpse as the authors get to know the crew, the rules, the languages, and the space around them. The rhythm becomes hectic as the first rescue operation approaches. The SAR team saves from the sea dozens (and later, hundreds) of people coming from several African countries. Many languages are spoken onboard, yet English is inevitably the privileged lingua francaFootnote8– in other words, a language used to facilitate communication between people who do not have the same first language. Interviews are mainly conducted in English, with the translation support of people who speak both Arabic and English. shows Youssuf, a man from Cote d’Ivoire, approaching spontaneously Bonaccorso (and Rizzo close by, represented from the back, wearing a cap) to be interviewed and tell his own story. The people saved by the Aquarius came from different places. There were people from countries of West Africa, East Africa, and North Africa, including Libyan nationals.

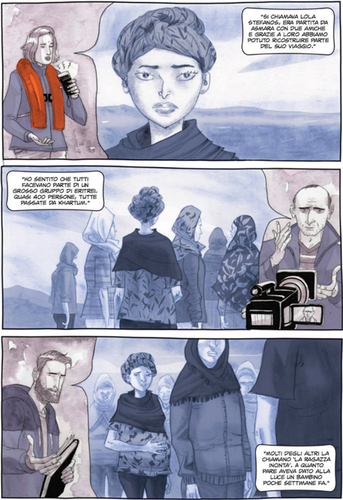

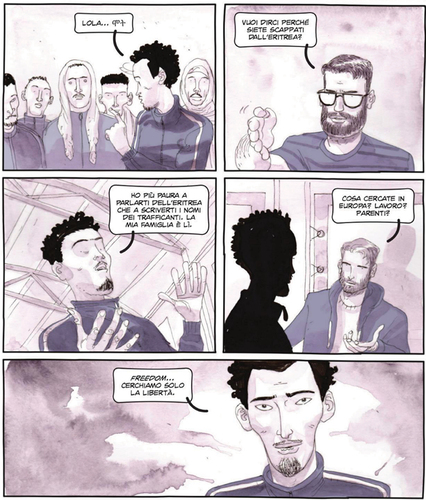

Women who undertake the journey are an important part of the narrative, especially those travelling while pregnant. Migrant pregnancy and childbirth on the Mediterranean route are a growing phenomenon, yet the ethical and medical challenges posed by poor maternal health indicators receive very limited coverage (EU Border Care Citation2017). The story of Lola Stefanov in Salvezza stands for this issue (). Lola was pregnant when she fled Eritrea, a country under dictatorship. Her debilitation was so severe that she gave birth to a dead child and passed away before starting the sea crossing. The story of Lola was put together by a group of Eritreans later rescued by the Aquarius. Data on missing migrants ‘are challenging to collect for a number of reasons’ (International Organization for Migration Citation2020b). Indeed, the information provided by rescued people helps to trace and reconstruct fatalities, but the exact number of missing people remains unknown. The mode of representation used by the authors conveys the collective and fragmented nature of information on migrant trajectories and the challenges of their documentation (). Each panel of features one of the reporters hosted onboard telling a bit of Lola’s story. The reporters are represented with their recording tools which serve as authentication strategies in comics journalism (Weber and Rall Citation2017). Megan Williams of Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (panel 1) uses a voice recorder, Janko Petrovec of RTV Slovenija (panel 2) films himself with a television camera, and Bonaccorso (panel 3) draws on his sketchbook to manually record what happens onboard. The speech balloons contain illustrations in shades of blue, which reconstruct Lola’s vicissitudes.

Abraham, whose flashback opened the comic, is among the rescued Eritreans who knew Lola and has much to tell about Eritreans’ reasons for fleeing (). In the third panel, Abraham says: ‘I am more scared to talk about Eritrea than to write down the names of the smugglers. My family is there’. Bonaccorso asks him, ‘What do you seek in Europe? Work? Relatives?’. Abraham’s answer is: ‘Freedom. We only seek freedom.’. The choice to keep ‘Freedom’ in English – pronounced by Abraham as he spoke with the authors – is quite impactful and highlights the dominant use of English, which I address further in the second section of this article. In contrast, the first panel features the word ‘ሞት’ which in Tigrinya language – spoken in Eritrea – means ‘death’.

Abraham and his wife Ruta undertook the journey to Europe in the hope of curing Ruta’s cancer, not curable in Eritrea. Besides, Ruta was expecting a baby after the abuses suffered in Libya. Abraham’s words about freedom from dictatorship are optimistic about the future. Yet, the next comics reportage by Rizzo and Bonaccorso offers a less hopeful glimpse at where the quest for freedom can lead.

A Casa Nostra. Cronaca da Riace

This comic answers the question ‘what happens after the rescue?’. The title can be translated as ‘…In our own country. Chronicles from Riace’. The first half – ‘In our own country’ – is a response to the anti-immigrant rhetoric pursued by the Italian Lega Nord with its slogan ‘Aiutiamoli a casa loro’ (‘Let’s help them in their own country’, Verbeek and Zaslove Citation2017, 394). The second half – ‘Chronicles from Riace’ – refers to Riace, a small town on the east coast of the Calabria region in the south of Italy. Lately, Riace made the news for the migrant-friendly approach taken by the former mayor Mimmo Lucano, who put together a programme to rejuvenate the city abandoned by the locals. Southern Italy is a site of emigration, and Lucano’s efforts over the years helped to avoid ‘demographic and economic desertification’ (European Commission Citation2016). Riace embodied a collectively participated system of hospitality, with opportunities for both the local community and the arriving people, offering solutions that sustained the place culturally and financially. The Riace experience was internationally regarded as an innovative and sustainable model for migrant integration worldwide (Driel Citation2020; Driel and Verkuyten Citation2019) and was also remembered in the broader American comics world. The anthology Marvel Comics #1000 (Ewing, Bartel, and Caramagna Citation2019) celebrates Marvel’s 80th anniversary and includes a one-page story dedicated to Riace, titled ‘Over Troubled Waters.’ The story depicts a young African girl hosted in Riace. She arrived alone, does not speak, and communicates only through her drawings. One of these drawings portrays Storm of X-Men, the superheroine who rescued her from the fury of the sea. The presence of Storm is particularly significant given that she has an African lineage and grew up alone after losing her parents in the Arab-Israeli conflict.

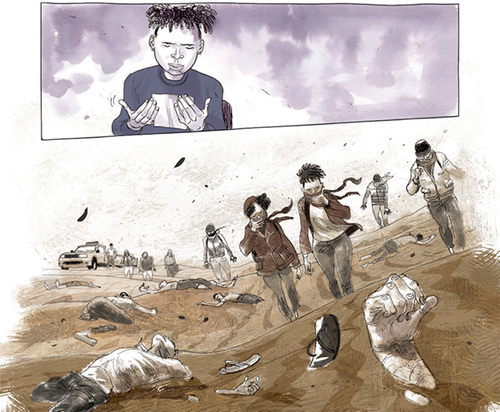

Riace is the first positive example of integration that Rizzo and Bonaccorso explore as they investigate the uncertain and insecure conditions of African people living in the Calabria region in 2018. The other positive example is the local reception project Protection System for Asylum and Refuge Seekers (SPRAR)Footnote9 in Gioiosa Ionica, whereas an example of failed integration is the shantytown of San Ferdinando, which was dismantled by the Italian Police shortly after the visit of the authors (Tondo Citation2019). Throughout their investigation, Rizzo and Bonaccorso realise that the external environment – demographic decline, unemployment, and oppression of ‘Ndrangheta, a criminal organisation originating and operating mainly in the region – really matters and has a significant impact on the lives of people with a migrant background. Similarly to Salvezza, this book focuses on migrant lived experiences and bears witness to the challenges of survival and integration posed by bureaucracy, politics, and policy issues. Blessing is the first woman to share her story. She is a cultural mediator in the SPRAR of Gioiosa Ionica, where she arrived ten years earlier from a village in the Niger Delta that she left with her sister after the murder of their father, the village chief. Blessing recalls the perennial turmoil in her village: ‘Where I come from there is always someone waging war against someone else’ and describes how they risked death by cut-throat in the desert, and the number of lifeless bodies lying on the sand as they continued their journey. Here, flashback sequences use sepia tones to recall the colours of the African desert ().

Further, she discusses with the authors the new regulations in force in Italy. Residence permits based on humanitarian grounds were revoked and required a permanent job to be renewed. Blessing’s story in the book hence conveys a critique of the pitfalls of decree no. 113/2018 on security and immigration – also called the ‘Salvini decree’ after Italy’s far-right Interior Minister at the time – which brought ‘drastic changes to the design of the Italian reception system’ (Asylum Information Database Citation2020).

The investigation continues in the shantytown of San Ferdinando, located on the outskirts of Rosarno, on the west coast of Calabria. The authors describe San Ferdinando as a place with a delicate social balance that can be altered easily. They get access thanks to their gatekeeper Giovanni Maiolo, legal representative of RE.CO.SOL, a network of Italian municipalities supporting people and countries from the Global South. Maiolo introduces Rizzo and Bonaccorso to Frank and Fodie, who walk them through the place. Before being shattered, San Ferdinando was a proper town hosting up to three thousand people, with a church, a mosque, and all sorts of shops and services organised in shacks. It was the shelter of many occasional orange pickers whose living and working conditions have been explored through the ethnographic project ‘The Bitter Oranges’ (Reckinger et al. Citation2017). Shantytowns belong to those ‘spaces of exception’ (Agamben Citation1998, 134) confined at the border of the nation-state, where people are deprived of their basic human rights. The poverty and neglect of hardline immigration measures are represented in , where fruitpickers pass by, and a stray dog is curled up next to some puddles. At first sight, the dog seems left on its own, just like the people living there. Nevertheless, there is some sense of community even in the abandonment of the shantytown. The stray dog was named ‘Salvini’ (after the far-right Interior Minister) to make sure everyone would remember its name. People living here are conscious of being ‘invisible’ but ‘convenient’ to the country that hosts them. The cheap cost of their labour, their exploitation, and their precariousness allow farmers to remain competitive in the market. Frank comments: ‘When they are eating, Italians do not care about the colour of the skin of fruit pickers’ and Fodie highlights how such conditions of uncertainty impact negatively on mental health: ‘Sometimes, simply, someone goes crazy. There are people who survived the desert and the sea. They have nowhere else to go and end up here, often by chance, in a place with its own rules, where time flows differently.’

Back in Gioiosa Ionica, Rizzo and Bonaccorso meet Ishak, a man who fled Egypt due to persecution for his religious beliefs. Ishak is a Coptic Christian, the largest religious minority in Egypt. He was beaten until he had hearing loss and speaks with the help of his sign language interpreter. The perspectives of Buba and Sherif, who endured slavery in Libya, conclude the book. They are perhaps the youngest who voice their concerns. Buba got a qualification as a cook through the SPRAR project and found a job in a restaurant. He arrived in Italy as his boss refused to pay him and promised a journey to Europe in exchange. Sherif shares his feelings about how migrants are regarded in the press: ‘Every day that I read the newspaper, it seems worse. […] Sometimes … I feel looks on me that are like stabs in the back’.

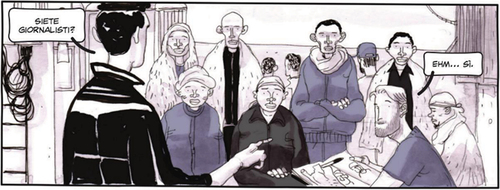

Migration and the great diversity of human life

Salvezza and … A Casa Nostra are ‘a form of witnessing’ (Chute Citation2016, 1) and contribute to the documentary form to ‘narrate and visually represent real people, events, and experiences’ (Mickwitz Citation2016, 9), offering a new way to appreciate migrant experiences beyond the news headlines. The media had ‘little or no interest in the “back stories” of those arriving’ (Crawley et al. Citation2018), whereas both comics are informed by first-hand engagement with the situations depicted and individual accounts of witnesses. Rizzo and Bonaccorso employ different strategies discussed at length by Weber and Rall (Citation2017) to ensure that their reporting is considered ‘authentic’ and transparent: they are present in the stories, provide photographic evidence of the locations depicted, reference photographic material, sketch directly on site, offer fact boxes, and disclose the production process. Salvezza documents the encounter between rescuers and rescued in the Mediterranean – a ‘critical junction between Global North and the Global South’ (Panebianco Citation2021) – providing an informed account of survival and salvation through the central migratory route. … A Casa Nostra explores experiences of migrant integration in the south of Italy and investigates the impact of migration policies. People well-placed in the local community acquire knowledge, skills, and make positive contributions. Those who lack opportunities for inclusion are subject to exploitation and abuse. Reconnecting with Abraham’s quest for ‘freedom,’ people who arrived in Italy have instead found uncertainty due to the hard anti-immigrant line pursued by the far-right party Lega Nord and the consensus it raised at the national level.

In the European media discourse, migration coverage is commonly framed negatively and is mainly focused on conflict, with migrants generally pictured as criminals or delinquents (Eberl et al. Citation2018). Journalism plays a crucial role in building a more inclusive society, and ‘a new appreciation of voice’ (Chouliaraki and Zaborowski Citation2017, 632) is fundamental for recognising the vulnerable and marginalised. When comics engage with journalism, unique representations afford visibility to different people’s stories and help the readership to develop thinking by capturing dynamics and drivers of migration often flattened under generalisations and assumptions. For Rizzo and Bonaccorso, spending time with the rescued people and engaging with them was vital to building trust and seeing the human experience behind the ‘refugee’ and ‘migrant’ labels. The space for sketching paved the way to more profound conversations where people asked to be heard, ‘a sort of confessional’Footnote10 wherein the authors conducted in-depth interviews and explored the reasons to leave and the challenges of a journey lasting several months or even years. Both comics are shaped to provide a platform for migrants’ voices, often marginalised or simply neglected in the mainstream media. Migrants’ voices make a substantial difference in enriching the discourse, whereas their absence deprives the audience of a balanced debate, with negative consequences for integration (Crawley et al. Citation2016b). The decision ‘to give groups a voice or to leave them voiceless’ (Thornbjornsrud and Figenschou Citation2016, 337) rests upon news media editors and writers, who decide what stories will be published. Ultimately, the agency for publishing individual stories rests with Rizzo and Bonaccorso rather than the migrants themselves. Yet, a prolonged time spent with the migrants helped the authors navigate the data gathered and assess the materials to publish against their ethical consideration.Footnote11 A more balanced media debate may constitute the bedrock for more significant social solidarity and integration and challenge those stories that tend to dehumanise migrants (Dempster and Hargrave Citation2017; Esses et al. Citation2013).

Focus on personal experiences fosters attention on humanness and its representation. In both comics, the skin of both European and African people is painted with the same shade of grey. Nonetheless, people are represented with their physical ethnic features, which makes it easier to identify those arriving from Africa or Europe (see, for example, ). The authorial choice to use the same shade of grey invites the readership to reflect on normative whiteness as the foundation of discrimination based on skin colour. Yet, this choice must not be understood as a denial of racial discrimination and inequality experienced by black people. The comics are mainly targeted at the broader Global North audience who does not have a South-North migrant experience background. Therefore, such a representation is a thought-provoking attempt to move beyond the Black/White binary paradigm of race and focus on humanness rather than skin colour.Footnote12 Further, the comics here discussed depict a great diversity of human life and a rich linguistic patrimony. This allows a more accurate representation of migrant groups often described homogeneously by the media when in fact, ‘they may speak different languages or have different cultural and religious practices’ (Kentmen-Cin and Erisen Citation2017, 5). Both comics offer several multilingual situations, and many languages are spoken aboard the Aquarius and in the shantytown of San Ferdinando. As aforementioned, some people with knowledge of English supported Rizzo and Bonaccorso during the interviews, translating Arabic and other African languages into English. The dominant role of English – which emerged as a global lingua franca in the second half of the past century – is marked by the word ‘Freedom’ included within a speech bubble containing text in Italian (Figure 10). Interestingly, the Mediterranean had its own lingua franca, Sabir, spoken until the 19th century. Sabir borrowed and merged elements of different languages of the territories bordering the Mediterranean (Sottile and Scaglione Citation2019). The evolving nature of lingua franca reflects power relations between populations and their shifting structure. Therefore, English – and French even earlier – prevailed on the sociolinguistic system based on Sabir and linguistic pluralism. English currently offers, in much of the region, ‘a basis for Mediterranean communication and even “dialogic space”’ (Spolsky Citation2014, 16). By engaging with Alison Phipps’ work on decolonising multilingualism (2019), it is possible to explore the connections between languages and the power relations associated with them. Phipps observes that ‘multilingualism is largely experienced as a colonial practice for many of the world’s populations’ (2019: 1). Her work is a practical attempt at decolonising knowledge and encourages transcultural perspectives along with reflections on historically dominant languages. In this regard, the Anglophone monopoly within academia has a lot to answer for. Pascal Lefèvre notes that scholars who do not publish in English have fewer chances of being read by the Anglophone audience (Lefèvre Citation2017). Yet, I remain conscious that English is the lingua franca I am using to communicate to a vast academic readership, in the hope that the knowledge conveyed by the comics here discussed circulates far and wide, getting attention outside the languages into which the books have been translated. Currently, both comic books are available in Italian (published in Italy by Feltrinelli ComicsFootnote13) and French (Salvezza titled ‘Abord de l’Aquarius’ and … A Casa Nostra titled ‘Chez nous, paroles de réfugiés’, both published by Futuropolis). Salvezza is also available in Spanish (published in Spain as ‘Aquarius: El buque de la esperanza’ by Panini Comics España). To balance the uneven geographical attentions of comics scholarship, Lefèvre encourages more research conducted transnationally with teams of researchers working together (Lefèvre Citation2010). And yet, we as scholars can do more to build contemporary comics studies as inclusive. Whilst we work towards understanding what ‘decolonising comics studies’Footnote14 means in theory and practice, we must make room for works by and about identities, experiences, and histories of those who have been silenced by colonialism. Phipps encourages to ‘work harder to cite those who live and work in languages other than English, or at least other than English first’ (Phipps 2019: 6). Comics conveying stories of migrants have the potential to contribute to strategies of decolonising knowledge as they offer a nuanced understanding of migration realities and the possibility of understanding things differently.

The comics here discussed evoke journeys, local geographies, and other people’s experiences of colonisation. Illustrations are fundamental to returning fragments of these stories and realities experienced by migrants. Focus on the significance of the pictorial component allows to go beyond matters of language and translation. Much ink has been spilled on the universality of images, which are increasingly used as a means of communication in our time. Yet, to what extent are images universal? In his work on the quest for a perfect language, Umberto Eco (Citation1997) invites to reflect on the multiple meanings that visuals can express, because ‘there is no universal code: the rules of representation (and of recognisability) for an Egyptian mural, an Arab miniature, a painting by Turner or a comic strip are simply not the same in each case’ (1997: 169). Thus, ‘universal’ would be too simplistic to say, but focusing on the comics genres and their associated affordances, the pictorial component is universal to a significant extent. Comics depicting stories of migrants exhibit much of what they represent. Going back to the story of Lola Stefanov, the technique chosen to illustrate her story allows following without much explication, comment, or the written text in the speech balloons. The reader does not necessarily understand the brutality behind the story of Lola but can appreciate the illustrations and the meaning conveyed. In this sense, images communicate in a way that helps to overcome language barriers and avoid the so-called ‘confusion of Babel.’

Conclusion

The general media discourse seldom captures the complexity underpinning the dynamics of contemporary migration through the Mediterranean and fails to convey in-depth knowledge of the situations depicted. Salvezza and … A Casa Nostra are timely examples of well-informed migration narratives based on accurate investigation and reporting. Therefore, they contribute to balance the media discourse and ‘reframe’ the Mediterranean crossings. Both comics deal with complexity and encourage critical thinking about migration journeys and migration policies. Most importantly, they make room for the voices often silenced in the wider migration media discourse and contribute to shaping ‘our’ understanding beyond the headlines of ‘crisis.’ These works suggest new ways of understanding by documenting personal migrant experiences – attentively and richly – against the growing uptake of indicators, data and statistics on migration focused on security and border control. The stories represented in Salvezza and … A Casa Nostra document the existing inequalities that support the decisions to leave and seek new opportunities beyond the Mediterranean. Abraham and Ruta set out to Europe in the hope of treating Ruta’s cancer, Blessing fled from ongoing conflicts, Ishak suffered religious persecution, Buba did not plan to come to Europe. Rizzo and Bonaccorso put humanness at the centre of their narratives, allowing readers to engage more critically with diverse knowledge and the multiple factors shaping migration, not least the intricate threads of bureaucracy that refugees and other migrants face at different stages of their journeys. Furthermore, Salvezza and … A Casa Nostra encourage reflections upon languages and the dominant role of English as a lingua franca in the Mediterranean, a region where another lingua franca was customarily spoken until the end of the 19th century. These comics highlight the linguistic richness and foreground pictorial components that empower and effectively enlighten migration stories. Their value is particularly significant in promoting transnational strategies to decolonising knowledge and allowing narrative space for those overshadowed by colonialism. Concurrently, bringing into the discourse comics outside the reach of Anglophone academics enriches the conversation on the possibilities that comics offer to both articulate and represent migration narratives. English as a lingua franca supports multilingual comics scholarship in exchanging and expanding knowledge about how comics engage with migration narratives and journalism more broadly. Ultimately, the comics explored here call for greater exchange between journalism, migration studies, and comics scholarship to challenge prevailing narratives and deliver in-depth knowledge to the hands of the readers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Throughout this article, I will use the phrase ‘refugees and other migrants’ to refer to international migration in an inclusivist position. The term ‘refugee’ holds a precise legal definition under international law, whereas the term ‘migrant’ is used in different ways, often in contrast to ‘refugee.’ The phrase ‘refugees and migrants’ seems to imply that refugees are not migrants. According to the inclusivist view, ‘everyone who changes their place of residence is a migrant, regardless of the causes and circumstances; refugees are included’ (Carling Citation2017, 1). The use of ‘refugees and other migrants’ reflects the possibility that some migrants are refugees.

2. Interview with Lelio Bonaccorso, December 2020.

3. Prosopopoeia identifies the rhetorical act of giving a voice to an imaginary or absent person, an animal, or an inanimate object.

4. Interview with Marco Rizzo, December 2020.

5. Interview with Lelio Bonaccorso, December 2020.

6. Interview with Marco Rizzo, December 2020.

7. Interview with Marco Rizzo, December 2020.

8. UNESCO defines lingua franca as ‘a language which is used habitually by people whose mother tongues are different in order to facilitate communication between them’ (UNESCO Citation1953, 46).

9. The Protection System for Asylum and Refuge Seekers (SPRAR) project supported asylum seekers and facilitated their integration through the coordination of local authorities.

10. Interview with Marco Rizzo, December 2020.

11. Interview with Marco Rizzo, December 2020.

12. Interview with Lelio Bonaccorso, December 2020.

13. The popularity of these comics is demonstrated by a joint publication in a single paperback volume (available for sale in September 2022), enriched with interviews and in-depth analysis of the themes discussed. In addition, these are the first comics to be published in the long-established paperback series ‘Universale Economica Feltrinelli’.

14. My analysis developed from the discussion on ‘decolonising comics studies’ held by the reading group ‘Researching Comics on a Global Scale’ convened by Nina Mickwitz at Comics Forum 2019.

References

- Agamben, G. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, edited by D. Heller-Roazan. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Asylum Information Database. 2020. ASGI. Short Overview of the Italian Reception System [online] available from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemichttps://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/italy/reception-conditions/short-overview-italian-reception-system [26 May 2021]

- Carling, J. 2017. “Refugee Advocacy and the Meaning of ‘Migrants’.” In PRIO Policy Brief, 2. Oslo: PRIO. https://www.prio.org/publications/10471

- Chouliaraki, L., and R. Zaborowski. 2017. “Voice and Community in the 2015 Refugee Crisis: A Content Analysis of News Coverage in Eight European Countries.” International Communication Gazette 79 (6–7): 613–635. doi:10.1177/1748048517727173.

- Chute, H. 2016. Disaster Drawn. Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Crawley, H., F. Düvell, K. Jones, S. McMahon, and N. Sigona. 2016a. Destination Europe? Understanding the Dynamics and Drivers of Mediterranean Migration in 2015. Coventry, UK: Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University.

- Crawley, H., K. Jones, and S. McMahon. 2016b. Victims and Villains: Migrant Voices in the British Media. Coventry, UK: Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University.

- Crawley, H., K. Jones, S. McMahon, F. Duvell, and N. Sigona. 2018. Unravelling Europe’s ‘Migration Crisis. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Dempster, H., and K. Hargrave. 2017. Understanding Public Attitudes Towards Refugees and Migrants. Working Paper 512, London, UK: Overseas Development Institute (ODI)

- Driel, E. 2020. “Refugee Settlement and the Revival of Local Communities: Lessons from the Riace Model.” Journal of Modern Italian Studies 25 (2): 149–173. doi:10.1080/1354571X.2020.1716538.

- Driel, E., and M. Verkuyten. 2019. “Local Identity and the Reception of Refugees: The Example of Riace.” Identities 27: 1–19. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2019.1611075.

- Eberl, J.-M., C. E. Meltzer, T. Heidenreich, B. Herrero, N. Theorin, F. Lind, R. Berganza, H. G. Boomgaarden, C. Schemer, and J. Strömbäck. 2018. “The European Media Discourse on Immigration and Its Effects: A Literature Review.” Annals of the International Communication Association 42 (3): 207–223. doi:10.1080/23808985.2018.1497452.

- Eco, U. 1997. The Search for the Perfect Language. Oxford UK & Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Esses, V. M., S. Medianu, and A. S. Lawson. 2013. “Uncertainty, Threat, and the Role of the Media in Promoting the Dehumanization of Immigrants and Refugees.” The Journal of Social Issues 69 (3): 518–536. doi:10.1111/josi.12027.

- EU Border Care. 2017. Giving birth on Europe’s remote borderlands. [online] available from http://eubordercare.eu [14 June 2021]

- European Commission. 2016. Italy: Integration model of small village Riace acknowledged by Fortune magazine [online] available from https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/news/italy-integration-model-of-small-village-riace-acknowledged-by-fortune-magazine [26 May 2021]

- Ewing, E. L., J. Bartel, and J. Caramagna. 2019. “Over Troubled Waters.” Marvel Comics #1000, (28 August 2019).

- Hárdi, L., and A. Kroó. 2011. “The Trauma of Torture and the Rehabilitation of Torture Survivors.” Zeitschrift für Psychologie 219 (3): 133–142. doi:10.1027/2151-2604/a000060.

- International Centre for the Migration Policy Development. 2017. How Does the Media on Both Sides of the Mediterranean Report on Migration? [online] available from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemichttps://www.icmpd.org/our-work/migration-dialogues/euromed-migration-iv/migration-narrative-study [26 May 2021]

- International Organization for Migration. 2020a. Mediterranean Arrivals Reach 110,699 in 2019; Deaths Reach 1,283. World Deaths Fall. [online] available from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemichttps://www.iom.int/news/iom-mediterranean-arrivals-reach-110699-2019-deaths-reach-1283-world-deaths-fall. 26 May 2021

- International Organization for Migration. 2020b. Missing Migrants. Methodology [online] available from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemichttps://missingmigrants.iom.int/methodology [26 May 2021]

- Kentmen-Cin, C., and C. Erisen. 2017. “Anti-Immigration Attitudes and the Opposition to European Integration: A Critical Assessment.” European Union Politics 18 (1): 3–25. doi:10.1177/1465116516680762.

- Kuttner, P. J., N. Sousanis, and M. B. Weaver-Hightower. 2017. “How to Draw Comics the Scholarly Way.” In Handbook of Arts-Based Research, edited by P. Leavy, 396–422. New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

- Lefèvre, P. 2010. “Researching Comics on a Global Scale.” In Comics Worlds and the World of Comics: Towards Scholarship on a Global Scale (Series Global Manga Studies, edited by J. Berndt, 85–95. Vol. 1. Kyoto: International Manga Research Center, Kyoto Seika University.

- Lefèvre, P. 2017. “A Pioneer’s Perspective: Pascal Lefèvre”. In The Secret Origins of Comics Studies edited by R. Duncan and M. J. M. P. Smith, 281–283. Abingdon: Oxon Routledge.

- Macias, T. 2013. “Tortured bodies’: The Biopolitics of Torture and Truth in Chile.” The International Journal of Human Rights 17 (1): 113–132. doi:10.1080/13642987.2012.701912.

- Merrill, H. 2018. Black Spaces: African Diaspora in Italy. New York: Routledge.

- Mickwitz, N. 2016. Documentary Comics. Graphic Truth-Telling in a Skeptical Age. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Newman, D. 1998. “Prophecies, Police Reports, Cartoons and Other Ethnographic Rumors in Addis Ababa.” Etnofoor 11 (2): 83–110.

- Panebianco, S. 2021. “Conceptualising the Mediterranean Global South: A Research Agenda on Security, Borders and Human Flows.” European and Global Studies Journal 4 (1): 17–34.

- Papanicolopulu, I. 2017. “The Duty to Rescue at Sea, in Peacetime and in War: A General Overview.” International Review of the Red Cross 98 (2): 491–514. doi:10.1017/S1816383117000406.

- Phipps, A., 2019. Decolonising multilingualism: Struggles to decreate. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters.

- Ramos, M. J. 2000. Histórias Etíopes. Lisbon, Portugal: Assirio e Alvim.

- Ramos, M. J. 2004. “Drawing the Lines: The Limitations of Intercultural Ekphrasis.” In Working Images: Visual Research and Representation in Ethnography, edited by S. Pink, L. Kürti, and A. I. Afonso, 147–156. London: Routledge.

- Reckinger, C., G. Reckinger, and D. Reiners. 2017. “Bitter Oranges. African Migrant Workers in Calabria.” Movements. Journal for Critical Migration and Border Regime Studies 3 (1): 21–23.

- Rizzo, M., and L. Bonaccorso. 2009. Peppino Impastato. Un giullare contro la mafia. Padova: BeccoGiallo Editore.

- Rizzo, M., and L. Bonaccorso. 2011a. Primo. Milano: Edizioni BD.

- Rizzo, M., and L. Bonaccorso. 2011b. Que viva el Che Guevara. Padova: BeccoGiallo Editore.

- Rizzo, M., and L. Bonaccorso. 2012. L’invasione degli scarafaggi. La mafia spiegata ai bambini. Padova: BeccoGiallo Editore.

- Rizzo, M., and L. Bonaccorso. 2014a. Jan Karski. L’uomo che scoprì l’Olocausto. Roma: Rizzoli Lizard.

- Rizzo, M., and L. Bonaccorso. 2014b. “Uno, nessuno, centomila migranti.” In Wired Italia 63. Milano: Condé Nas Editore.

- Rizzo, M., and L. Bonaccorso. 2015. “Scarpe”. In La traiettoria delle Lucciole 16–20. Padova: BeccoGiallo Editore.

- Rizzo, M., and L. Bonaccorso. 2016. L’immigrazione spiegata ai bambini. Il viaggio di Amal. Padova: BeccoGiallo Editore.

- Rizzo, M., and L. Bonaccorso. 2018. Salvezza. Milano: Feltrinelli Editore.

- Rizzo, M., and L. Bonaccorso. 2019. … A Casa Nostra. Cronaca da Riace. Milano: Feltrinelli Editore.

- Silove, D. 1999. “The Psychosocial Effects of Torture, Mass Human Rights Violations, and Refugee Trauma: Toward an Integrated Conceptual Framework.” The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease’ 187 (4): 200–207. doi:10.1097/00005053-199904000-00002.

- Sottile, R., and F. Scaglione. 2019. “La lingua franca del Mediterraneo ieri e oggi. Assetto storico-linguistico, influenze italoromanze, ‘nuovi usi.” In Lo spazio comunicativo dell’Italia e delle varietà italiane, edited by T. h. Krefeld and R. Bauer, 1–128. Muenchen: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München.

- Spolsky, B. 2014. “The Mediterranean as Sociolinguistic Ecosystem”. In Language Policy and Planning in the Mediterranean World edited by M. Karyolemou and P. Pavlou, 12–22. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Thornbjornsrud, K., and T. U. Figenschou. 2016. “Do Marginalised Sources Matter? A Comparative Analysis of Irregular Migrant Voice in Western Media.” Journalism Studies 17 (3): 337–355. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2014.987549.

- Tondo, L. 2019.“Salvini Crackdown: Bulldozers Demolish Italian Camp Housing 1,500 Refugees.” [online] available from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/mar/06/salvini-crackdown-bulldozers-clear-italian-camp-housing-1500-refugees 14 June 2021

- UNESCO. 1953 The Use of Vernacular Languages in Education [online] available from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0000/000028/002897eb.pdf [14 October2021]

- UNHCR. 2015 The Sea Route to Europe: The Mediterranean Passage in the Age of Refugees [online] available from http://www.unhcr-northerneurope.org/uploads/tx_news/2015-JUL-The-Sea-Route-to-Europe.pdf 14 October 2021

- Verbeek, B., and A. Zaslove. 2017. “Populism and Foreign Policy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by C. R. Kaltwasser, P. A. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy, 384–405. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Weber, W., and H. M. Rall. 2017. “Authenticity in Comics Journalism. Visual Strategies for Reporting Facts.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 8 (4): 376–397. doi:10.1080/21504857.2017.1299020.