Abstract

Crop-raiding by wildlife is a common concern in areas where agriculture plays an important role for sustaining rural livelihoods. Different techniques have been used to prevent crop loss by wildlife. This study examined wildlife crop damage as reported and experienced by people in villages surrounding Serengeti National Park (SNP). The results showed that generally crop production was not the only important economic activity people relied on. We conclude that hunting could be an alternative to crop production. Furthermore, education, employment status, wealth, immigration status and location influenced crop production significantly. Perceptions towards problematic wildlife varied between districts, but small- to medium-sized wildlife were perceived most problematic to crop production. Furthermore, respondents identified climate change factors and inadequate agriculture extension services to affect crop production. The study proposes further development of income-generating activities such as beekeeping and ecotourism as alternatives to crop production. These natural resources-based activities address food insecurity and increase livelihood options. Compensation for extreme cases of crop destruction and improved capacity and delivery of extension services could make agriculture around Serengeti more sustainable.

Introduction

Although about 80% of people in Africa live in rural areas and 70% of them engage in agriculture, the number of people that are malnourished and live in poverty has risen in recent decades (Gabre-Madhin and Haggblade Citation2004). Factors including human population growth rate, increasing land scarcity, increasing populations of wild animals as a result of improved conservation efforts and climatic factors challenge wildlife conservation in Africa and elsewhere in the world where agriculture is an important part of rural livelihoods (Messmer Citation2000; Fall and Jackson Citation2002; Patterson et al. Citation2004; Distefano Citation2005). Countries like Tanzania, Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi have a significant proportion of their territories designated as protected areas (Scheri et al. Citation2004). Many people living near these protected areas depend on crop production for food security and livelihoods. As a result, crop-raiding by wildlife has emerged as a major conservation and livelihood concern to these people (Gillingham and Lee Citation2003; Hill Citation2004; Holmern Citation2007). Crop-raiding by wildlife causes food insecurity and increases income poverty. According to Bryceson et al. (Citation2005), rural poverty contexts imply a stronger pressure on the use of natural resources. When people's crops are raided, they must reallocate labour to other pursuits, for example, bushmeat hunting (Barrett et al. Citation2001). Local people rarely tolerate the loss without retaliations. Studies report incidences where people have been hostile to wildlife and getting into conflicts with conservation authorities (Hill Citation1998; Naughton-Treves Citation1998).

Small-scale farmers in some places of Africa use different techniques to protect crops from wildlife such as crop guarding, bushmeat hunting, burning area, pitfalls and snares, hedges and reinforcing farm fences and use of dogs (Prins Citation1987; Naughton-Treves Citation1998; Hill Citation2000; Sitati et al. Citation2005). The use of these wildlife control techniques is often unsustainable, has limited effect and is considered illegal (URT Citation1974; Holmern et al. Citation2004). Rusch et al. (Citation2005) identified that the use of fire was common in Serengeti and was not in agreement with the practices applied in the national parks. Studies in Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya and India propose deployment of deterrents, trophy hunting, planting agro-forestry buffers and non-palatable crops to wildlife around the parks, as well as insurance programmes, and the relocation of people (Naughton-Treves et al. Citation1998; Madhusudan Citation2003; Baldus and Cauldwell Citation2004; Sitati et al. Citation2005). Many farmers in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe convert their lands into wildlife ranches to gain greater financial returns from wildlife and tourism industries (Barnes and de Jager Citation1995; Bulte and Horan Citation2003). Very seldom do wildlife laws sanction the killing of problematic wildlife for reasons such as crop loss or human killings (URT Citation1974; Baldus and Cauldwell Citation2004). So far there are no documented successes in preventing damage by wildlife or compensating people's loss of crops and livestock caused by wildlife in Africa (Osborn Citation2002; Gadd Citation2005). Ineffectiveness of some methods, technological complexities and cost implications are some of the factors limiting the success of the crop preventive techniques and compensation schemes (Distefano Citation2005). In Western Serengeti crop damage may be as high as USD 0.5 million a year (Emerton and Mfunda Citation1999).

In recent years there has been hope for the community-based conservation (CBC) to increase tolerance to crop damage and solve poverty problems (Naughton-Treves Citation1998; Gillingham and Lee Citation2003). The CBC concept promotes participation and sharing of the benefit of conservation with local people (Campbell and Vainio-Mattila Citation2003; Thakadu Citation2005). In countries such as Zimbabwe, Zambia and Tanzania the CBC outreach schemes including the Communal Area Management Programme for Indigenous Resources, Administrative Management Design for Game Management, Luangwa Integrated Resource Development Project, Selous Conservation Programme and Serengeti Regional Conservation Project (SRCP) were established to compensate local people for loss of natural resources, livestock, crop damage, lives and to create alternative income-generating activities (Mfunda Citation2010; Nyahongo Citation2010). From these few cases, it is clear that inadequate participation and minimal benefits formed stumbling blocks to conservation and livelihoods (Agrawal and Gibson Citation1999; Gibson Citation1999; Gadd Citation2005; Kaltenborn et al. Citation2008). In Serengeti, the conservation benefits offered by the Serengeti National Park (SNP), SRCP, Ikona Wildlife Management Area (WMA) and the private investors are confined to basic social services in terms of buildings, provision of drugs and educational materials and payment of staff. The services include health centres, education and schools and water – and stops at community level (Holmern et al. Citation2004). Understanding potential avenues for natural resources to contribute on a sustainable basis towards reduced poverty is necessary in order to address livelihood concerns. As urged by Prins (Citation1987), land use and nature conservation are tightly interlinked and people and wildlife can both benefit from improvements aimed at integrated land use, agricultural development and higher economic returns. According to Bryceson et al. (Citation2005), natural resources can reduce income poverty by promoting increased benefits to local people based on sustainable management. Christophersen et al. (Citation2000) identified tourism (trophy) and resident hunting, photographic tourism and beekeeping as feasible natural resources-based activities by local people in WMAs like Ikona in Serengeti. The presence of tourism investments in Western and Eastern Serengeti is a healthy situation for the economy of the study villages as they provide opportunities for community-based tourism entreprises, create market for local products, employment and a lifting to conservation and livelihoods (unpublished data from the authors). However, capacity building is a challenging aspect of community-based entreprises (Kikula et al. Citation2003).

This study examined wildlife crop damage as reported and experienced by people in villages surrounding the SNP, Tanzania. This paper discusses the factors influencing crop production as well as solutions to food insecurity and poverty in the context of wildlife conservation and human development. The Tanzania's National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP) appreciates the contribution of natural resources to growth and poverty reduction (URT Citation2006). The NSGRP goals that are relevant to Millennium Development Goals and natural resources management strategies include ensuring sound economic management, reduced income poverty and improved quality of life and social well-being (URT Citation2006). In this perspective this paper aims to link natural resources and wildlife in particular with the reduced food insecurity and reduction of poverty. We addressed wildlife and crop production issues by using data from household questionnaire survey, focusing on the following key research topics: (1) crop production to households as an important economic activity to households; (2) farm size versus food security to households; (3) crop-raiding by wildlife as a concern to households; and (4) other factors influencing crop loss to households in Western and Eastern Serengeti.

Methods

Study area

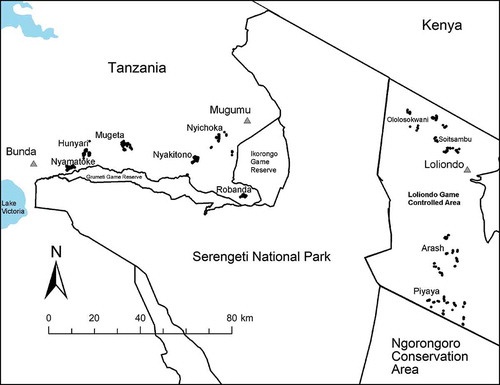

The study was carried out in Bunda and Serengeti districts on the western and Ngorongoro district in the eastern side of the SNP () between 2008 and 2009. The SNP (14,763 km2) is a World Heritage Site, Biosphere Reserve, and forms the heart of the Serengeti Maasai-Mara Migratory Ecosystem of north-western Tanzania and south-western Kenya. SNP borders the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, which is a multiple land use area which is also a Biosphere Reserve and a World Heritage Site. It also borders the Ikorongo, Grumeti and Maswa Game Reserves, the Ikona WMA and the Loliondo Game Controlled Area (GCA). Seven districts, including the Serengeti, Bunda and Ngorongoro, share administrative boundaries with the national park. The Serengeti ecosystem supports populations of resident ungulates including wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus), Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer) and zebra (Equus burchelli); large carnivores such as lion (Panthera leo), leopards (Panthera pardus), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and spotted hyenas (Crocuta Crocuta); and species of birds like ostrich (Struthio camelus massaicus) and Egyptian vultures (Neophron percnopterus). The ungulates are characterised by the annual wildebeest migration. The ecosystem accounts for major part of wildlife-based tourism in Tanzania. The wildlife tourism encompasses activities including wildlife viewing, photographic and walking safaris, trophy hunting and bird watching.

Figure 1. Locations of Bunda, Serengeti (Mugumu) and Ngorongoro districts (Loliondo) are indicated by the gray triangles. The studied villages in the west and east of the Serengeti National Park (SNP) are also indicated.

The study area has an average annual temperature of 21.7°C and annual rainfall ranging between 500 and 1200 mm, declining towards the eastern side to the short grass plains of the national park boundary and increasing towards Lake Victoria (Campbell and Hofer Citation1995). The Western Serengeti is considered as an area with low suitability for arable agriculture, although its subsistence economy depends mainly on crop production and livestock keeping (Emerton and Mfunda Citation1999). Crop production is constrained by inadequacies and poor delivery of agriculture extension services and facilities that entail provision of agricultural inputs, labour-saving equipment and expert advice on crop production. The lack of good agriculture extension services forces people in villages to practice extensive farming systems, which cause encroachments to protected areas, crop-raiding by wildlife, deforestation and low harvests. The crop production is complemented with off-farm activities such as illegal hunting and selling of natural resources products such as building materials and charcoal. Tourism contributes immensely to the economy of Serengeti and national at-large, but its support to enhancing rural livelihood has been minimal (Honey Citation2008).

Data collection

The data on household perceptions of wildlife crop damage were collected through a questionnaire survey between January and December 2008. The survey involved 477 head of households (≥18 years old). The respondents were from Western Serengeti (65%) and Eastern Serengeti (35%). They were selected by stratified random sampling based on respective villages and sub-villages lists of households. Except for Ololosokwani, the survey was conducted with 50 household heads in each of the 10 selected villages. Fewer households were interviewed in Ololosokwani because of boundary disputes between the village and the SNP. The villages close to and further from national park and game reserve boundaries were selected for the interview. These included: Nyamatoke (2.5 km away from boundaries), Robanda (4 km), Piyaya (6.5 km), Hunyari (6 km), Nyakitono/Makundusi (8 km), Nyichoka (8 km), Ololosokwani (11 km), Mugeta (12 km), Soitsambu (21 km) and Arash (27 km) (). All study villages in the Ngorongoro district fall within the Loliondo GCA. In the GCAs only wildlife consumption is regulated but other forms of land use, including grazing of livestock, cultivation or human settlements, are not restricted. Thus, the villages within the Loliondo GCA can be described as extensively settled and managed villages (URT Citation1974).

The questionnaire consisted of a combination of fixed and open-ended questions. The question on background information on households covered place of birth of the respondent, age, tribe, place of origin, education and household size. Questions on socio-economic activities addressed employment, crop production, livestock keeping and off-farm activities, and issues related to CBC in terms of wildlife management, perceptions of relationship and benefit-sharing scheme. We asked the head of households questions related to (1) crops grown by households, (2) farm size, (3) uncultivated land, (4) the causes of crop loss, (5) crops destroyed by wildlife in last 12 months and (6) problematic wildlife. The responses from the questions were analysed to generate information on various aspects of crop production. We defined agriculture as the production of food and goods through farming and concentrated on crop production. To capture wealth holdings as a measurement of poverty we constructed a wealth index using tangible wealth holdings for households interviewed. The possession scores were calculated for each of the household sampled as an index of wealth, a technique used in socio-economic studies (Smith and Sender Citation1990). The items used in the calculation of the possession score included houses, livestock holdings, household equipments (cell phone, radio, television, bicycle and motorised transport) and amount of land owned. The possession scores were calculated from points assigned to each item owned by the household in approximate proportion to the items cash value. For instance, houses were described in terms of ‘no house’, ‘poor’ (non-metal roof, mud or trees walls, no floor, no windows and good doors), ‘good’ (metal or non-metal roof, mud bricks, good mud floor, good windows and doors) and ‘very good’ (metal roof, cement or burnt bricks, cement floor and good windows and doors). Wealth categories, namely ‘poor’ (destitute) (≤0.49) and ‘rich’ (≥0.50) were developed based on distribution of possession scores, and we weighted the possession score according to maximum score possible (maximum = 21) (; Mfunda et al. unpublished data). We also considered the number of livestock (few, <50; many, ≥50) as an investment to households.

Table 1. Items included in the calculation of possession score

Statistical analyses

In the analyses, the household engagement in crop production, factors affecting crop production, sizes of farm plots and problematic wildlife based on the knowledge of the respondent were tested as dependent variables. Socio-economic factors such as districts and locations (districts: Bunda, Serengeti, Ngorongoro; locations: western, eastern), immigration status of people (yes, no), education level (educated, uneducated), employment status (employed, unemployed) and number of livestock (few (less than 50), many (above 50)) and wealth index (poor, rich) were examined as independent variables.

The reported sizes of farm plots were categorised into small and large land holdings. The crops grown were food crops including maize (Zea mays), cassava (Manihot esculenta), Sorghum spp. and finger millet (Eleusine coracana); cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) as a cash crop; and other food crops such as sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) and a variety of vegetables. The olive baboons (Papio anubis), bush pigs (Potamochoerus porcus) and insects and birds were presented as small–medium-sized wildlife in the analyses. Elephants (Loxodonta africana) are the only reported big wildlife in both locations. To identify relations, common responses were analysed with Pearson's χ2 tests using Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Version 16 (SPSS, 2005, SPSS for Windows, Release 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). None of the independent variables were highly correlated (ρ < 0.516). Only statistically significant results are presented and discussed.

Results

The average household size was 11 (±8.7 SD) members. The basic primary education level and the mean age of respondents were 69.8% and 47 (±14.2 SD) years respectively. Most households were engaged in crop production (83%), livestock keeping (74%), and 30% of people were reported to be employed. The average annual income per household was USD 799 (±787 SD). The average household income of USD 799 is higher than what Borge (Citation2003) recorded in 2003 which was only USD 140. Private tourism investors have employed people from neighbouring villages surrounding the SNP and created a market for local products. Of the respondents 37.3% (N = 477) who reported to have immigrated to villages were motivated by crop production (40.9%), marriage (29.6%), returning home (14.5%), searching for good pastureland for livestock (8.1%) and searching jobs (7%). Traditionally people in Western and Eastern Serengeti are agro-pastoralists and pastoralists. Crops grown included food crops (38.5%, N = 477), cotton as a cash crop (35.2%) and other crops (9.3%). Of the respondents 17.2% did not cultivate any crops. Except for maize, most grown food crops are drought-resistant crops and favour a semi-arid climate. The growing season for all crops except cassava is from March to July, and cassava is grown throughout the year and is harvested according to needs for food and demands for income.

Crop production

The level of people engagement in crop production was high in Bunda and Serengeti villages in the Western Serengeti compared with that in the Ngorongoro district in the Eastern Serengeti. Immigration status, education level and employment status influenced crop production. Those who were educated and employed were more often engaged in crop production (). Furthermore, wealth status had no effect on the respondents' engagement in agriculture. The rich and the poor were all engaged in crop production. Those who had immigrated to villages, educated persons, those who had secured jobs and those who owned few livestock were more engaged in crop production ().

Table 2. Percentage of farming activities, household crop sizes and crop-raiding by wildlife in villages outside the Serengeti National Park (SNP) in relation to location (districts, Western and Eastern Serengeti), immigration status, education level, employment and wealth in terms of number of livestock and wealth index

There was no significant difference between the three districts in the acreage of cultivated farm plots (). The majority (88.6%, N = 316) reported to cultivate small farm plots (≤2 acres), and a few (11.4%) cultivated large farm plots (≥2 acres) (). When asked if household owned uncultivated lands, the majority (83.4%) reported to own surplus land plots (2–5 acres). The range of food crops harvested was 0–500 kg for the majority (94.4%, N = 306), while a few households (5.6%) harvested 1000–1500 kg. Immigration status and wealth significantly influenced the determination of farm sizes to households. Those who reported not to immigrate to villages and the poor in terms of wealth index reported to own big acreage of farm plots. Further, the wealth had no effect on crop production. Only 15.8% of immigrants and 8.2% of the rich were considered to cultivate large farm plots ().

Factors influencing crop production

Out of 477 respondents in the three districts (pooled), 346 admitted to be affected by crop-raiding by wildlife, while 131 respondents reported not to be affected by wildlife. Wildlife-related crop damage had a significant effect on crop production performance in both districts. Education level, number of livestock owned and wealth (in terms of wealth index) considerably influenced people's perception over crop damage (). The respondents in both districts identified problem animals in the group of small–medium-sized wildlife (51.8%, N = 353) including olive baboons, dik-diks (Madoqua kirkii), red duikers (Cephalophus natalensis), coqui/crested francolins (Francolinus coqui, Francolinus leucoscepus), warthog (Phacochoerus aethiopicus) and bush pigs. Elephants ranked the second (41.1%) followed by the migratory species (7.1%) – wildebeest (C. taurinus) and zebra (E. burchelli) (). The most affected crops were food crops including sorghum, sweet potatoes, vegetables and finger millet, and cotton as a cash crop. Most losses were of maize, cassava, beans and cotton.

Table 3. Crop-raiding by different wildlife outside the SNP in relation to districts and number of owned livestock

Respondents identified unpredictable rainfall, crop-raiding by livestock and inadequate farming skills to also affect crop production (). Overall, 81% (N = 169) of the respondents pinpointed inadequate farming skills and unpredictable rainfall (combined) to affect crop production. Those who were more affected by unpredictable rainfall were generally not educated, had few livestock and were poor. Crop-raiding by livestock was common in the Ngorongoro district, although it was not an issue of concern. Those affected by inadequate farming skills were educated, had few livestock and were relatively rich (). The difference between crop-raiding by wildlife and other factors (i.e. unpredictable rainfall, crop-raiding by livestock and inadequate farming skills – pooled) affecting crop production was significant (χ2 = 40.84, df = 2, p < 0.001). The households that reported crop-raiding by wildlife were also reported to be affected by inadequate farming skills (56.1%), crop-raiding by livestock (25.2%) and unpredictable rainfall (18.7%). In contrast, those who did not experience crop-raiding by wildlife claimed to be more affected by unpredictable rainfall (67.7%), inadequate farming skills (24.2%) and crop-raiding by livestock (8.1%).

Table 4. Other causes of crop loss in villages outside the SNP in relation to districts, immigration status, education level, number of livestock owned and wealth index

Multivariate analyses of households’ engagement in crop production

Logistic regression analysis showed that crop production is influenced by geographical location (western vs. eastern), number of livestock owned and gender proportions (female, 44.7% and males, 55.3%). The results indicate that many people were engaged in crop production in the Western Serengeti than in the Eastern Serengeti. Likewise, crop production was more practiced by people who owned few livestock than people with many livestock. More males were engaged in crop production than females, although the difference was found to be not significant. The three variables provided the best prediction for household involvement in crop production and explained 31.2% of variation in household involvement in crop production (). Furthermore, the immigration status of people and wealth had a substantial effect on the acreage of farms reported to be cultivated by households. The results suggested that immigrants to villages and the rich people showed a tendency to cultivate large acreage of farms (≥2 acres). However, although statistically significant, the two variables explained only 7.4% of the observed variation in the household acreage of farms ().

Table 5. Regression analysis of the factors influencing crop production in villages surrounding the SNP

The geographical location, education level, employment status and wealth variables significantly influenced the respondent's perception of crop damage by wildlife. Educated, employed and rich people were more engaged in crop production and therefore more exposed to crop-raiding by wildlife. The involvement of the educated, those who were employed and the rich in crop production was associated with the possibility of using cheap labour available in the respective villages. These independent variables explained 9.4% of variation in crop-raiding by wildlife (). People in Western Serengeti were more concerned about problematic wildlife compared with those in Eastern Serengeti (). We further found that crop loss was primarily correlated to immigration status of people and wealth. The immigrants and rich people grew more crops, and therefore were more affected by unpredictable rainfall and inadequate farming skills. These two variables explained 3.8% of variation in crop loss. These variables form a significant relationship and explain a certain portion of the variance in crop production. The low explanation values of the variation are probably due to the fact that the majority do not rely on agriculture as the only important economic activity.

Discussion

There are several likely shortcomings of relying completely on the questionnaires that might have influenced our crop production and crop-raiding by wildlife data. The respondents were not able to give the measurement of farm sizes, crop harvested and the crop damaged by wildlife. Furthermore, data on quantity of crops sold for household income and the quantity consumed that is most appropriate to reach conclusion were based on estimates. In this regard, we assumed that the respondents may have overestimated the farm sizes, harvested crops, including the levels of damage by wildlife. As Holmern et al. (Citation2004) pointed out, most respondents report the approximate number of acres damaged as a percentage of the number of acres cultivated, and not the actual share of crops damaged due to difficulties in measurement. This study cannot rule out the possibility of respondents to deliberately overstate crop-raiding problems. We minimised the shortcomings by comparing our findings with other similar studies (Iwai Citation1997; Hill Citation2004; Holmern et al. Citation2004).

The results suggest that crop production is more common in Bunda and Serengeti than in Ngorongoro district. People with few livestock, the rich in terms of wealth index and immigrants to the villages were identified to be most involved in crop production. The rich and immigrants had a tendency to cultivate comparatively larger acreages. The majority of households cultivated small farm plots, a reflection of subsistence farming characterised by small farm plots, shifting cultivation, little application of inputs and small harvests. Most households owned small farm plots for crop production. As a result the majority were not much affected by factors such as crop-raiding by wildlife, unpredictable rainfall and inadequate farming skills. Holmern et al. (Citation2004) found that in Bunda and Serengeti most households own relatively small pieces of land for crop production. As documented in a study from Robanda village (Iwai Citation1997), the crop harvest was not enough to supply food to households throughout the whole year. Boone et al. (Citation2006) revealed that in Ngorongoro large-scale cultivators are immigrants to the conservation area.

Arable land was not a problem in the Bunda and Serengeti districts. Out of 1.5 million hectares of arable land suitable for agriculture in Mara region, where Bunda and Serengeti districts are located, only 15% is under cultivation. Much of the arable land was available for crop production in Bunda and Serengeti districts (URT Citation2008). The reasons for cultivating such small acreages could be explained by workload in terms of application of hand hoe and crop protection against problematic wildlife. The nature of diurnal and nocturnal wildlife crop raids requires more forces for guarding crops during day and night, and in this case, the results suggest that more acreage means more workload to households. Our results suggest that crop production cannot be perceived as the only important economic activity for people to rely on in Western and Eastern Serengeti. According to Kikula et al. (Citation2003), application of hand hoe, lack of farm inputs and inadequate innovative skills cannot portray agriculture as a backbone of the economy at national level, despite the fact that at many household levels it remains the main lifeline support entity due to limited alternative livelihood strategies.

Our study suggests that educated people, those who had secured jobs and the rich were more affected by wildlife because of their involvement in crop production. Nevertheless, out of 346 respondents who reported their crops being destroyed by wildlife, 131 did not grow any crop in 2008. We associated this pattern with fear of crop loss, injury and death from wildlife that may discourage agriculture, as also indicated by other studies (Parry and Campbell Citation1992; Kaltenborn et al. Citation2003; Holmern et al. Citation2004; Kaltenborn et al. Citation2006). Problematic wildlife may also camouflage other factors affecting crop production such as inadequate farming skills and unpredictable rainfall. We also considered the chances for crop production to mask activities like illegal bushmeat hunting especially for males (Holmern et al. Citation2004; Thirgood et al. Citation2004), and the possibilities for people to overstate crop-raiding problems in order to share concerns with other stakeholders (Hill Citation1997; Naughton-Treves Citation1998; Siex and Struhsaker Citation1999; Holmern et al. Citation2004). In a study on perceptions of wildlife conflict in Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania, it was found that 52% of respondents who perceived wildlife conflicts as being associated with game reserve lacked experience of crop damage by large mammals (Gillingham and Lee Citation2003). Under such circumstances, this study suggests that fear of crop-raiding by wildlife was overemphasised.

Our study suggests existence of a considerable variation between districts on people's perceptions to problematic wildlife. The respondents in Bunda villages were most concerned with elephants. The Serengeti villages were affected by both elephants and small–medium-sized wildlife. The Ngorongoro villages were mostly affected by the small–medium-sized wildlife. It was further noted from discussions with the respondents that the crop-raiding problem by small–medium-sized wildlife occurs throughout cropping season while problems by elephants to crops are seasonal. Crop-raiding by livestock was not a problem in Ngorongoro district because less people were engaged in crop production and had small farm plots reinforced with farm fences. Generally, in Western Serengeti Holmern et al. (Citation2004) found that wildlife-induced damage to crops was more widespread compared with damage caused by domestic animals including the livestock. Overall, the small–medium-sized wildlife was the most problematic wildlife to crops. Other studies in Laikipia in Kenya and Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania reported a similar pattern on problematic wildlife to crops (Gillingham and Lee Citation2003; Gadd Citation2005). The migratory species were not reported to cause major threat to crops. A possible explanation for this trend is that the wildebeest migration spent very little time in village areas and their presence often occurs after harvest, usually in June–July on its way from southern Serengeti to the Maasai-Mara in Kenya. This preposition is in agreement with Thirgood et al. (Citation2004) and Rusch et al. (Citation2005) who reported that wildebeest in Serengeti occurs within core protected areas (i.e. national park, conservation area and game reserves).

Our findings suggest an association between problematic wildlife to crops and the bushmeat hunting preferences in the study area. This relates with other research, which establish that the ethnic groups in Western Serengeti prefer medium–big-sized wildlife and the Maasai of Eastern Serengeti likes the small-sized wildlife (Mfunda and Røskaft Citation2010). Bushmeat hunting is an important alternative activity to crop production especially when there is crop failure. Our findings support Johannesen's (Citation2005) study that increased crop loss increases bushmeat hunting. The Tanzania wildlife conservation laws have no provision for compensation, although in recent years there has been some consolation to persons victimised by wildlife in terms of crop loss, injury or death (Muya, personal communication). This is an indication of a positive development to conservation and livelihoods. Often expansion of agriculture impacts wildlife and threatens conservation goals (Rusch et al. Citation2005; Sachedina Citation2006).

The comparison between crop loss from wildlife and other factors affecting crop production variables showed that people were much more concerned with inadequate farming skills (44.4%) and unpredictable rainfall (36.7%). From the results, we concluded that the effects of climate change were being felt in villages and people noticed some changes. The respondents reported that unpredictable rainfall and variations in seasons were among the consequences of climate change. They further claimed that frequent droughts caused water shortages and ultimately lower crop yields. In Zambia, Wainwright and Wehrmeyer (Citation1998) reported agriculture development to be hindered by natural factors including draughts and floods. It was observed in the course of this study that the main sources of water to villages including seasonal rivers, shallow and deep wells do not meet demands and most of them have collapsed due to inadequate routine services and maintenance. Inadequate agricultural inputs such as fertilisers, improved seed varieties and insecticides contributed to low crop yields. Inappropriate and extensive farming systems reduced productivity and caused destruction of wildlife habitats and populations (Homewood et al. Citation2001). People are compelled to open more land for agriculture including critical wildlife areas such as habitats and corridors in order to increase crop yield. Sachedina (Citation2006) disclosed that converting the corridors and wildlife dispersal areas to agriculture contributes to the insularisation of protected areas such as Tarangire and Manyara National Parks, hence increased wildlife declines in the ecosystems. However, issues related to climate change factors were outside the scope of this study.

Conclusions and recommendations

The most important issue emerging from this study is that crop production was an important economic activity to people who were educated, those who had few livestock, the rich in terms of wealth index and immigrants to villages. To the majority, including those who were not educated, people with many livestock, the poor in terms of wealth index and non-immigrants to villages, crop production was not the only important economic activity to rely on. Despite the fact that more people were engaged in crop production, the harvests cannot adequately address the food insecurity in big households like the one found in the study area (an average of 11 household members). It is further concluded from the results that the households in both areas relied on other alternatives including unsustainable use of natural resources.

An association between problematic wildlife to crops and bushmeat hunting preferences led to the conclusion that bushmeat hunting could be an important alternative activity to crop production. From this viewpoint, the local people, especially in the Western Serengeti are faced with the dilemma between extensive farming and wildlife conservation. We further identified education level, employment status and wealth to have significantly influenced people's engagement in crop production. Local people were affected differently by the crop-raiding wildlife, although small–medium-sized wild animals remained the most problematic to crops. From the findings it was further concluded that people were also much more concerned with other factors including inadequate farming skills, unpredictable rainfall and inadequate extension services.

Based on the findings, our study recommends the use of natural resources to address poverty reduction. The natural resources such as wildlife and forest resources and products, if adequately managed and applied in a sustainable manner, can be sustained and make a direct contribution towards alleviating poverty and improved livelihoods. The viable options may include: (1) beekeeping as a traditional income-generating activity, requires less investments and is accessible for all groups of people with a potential to increase livelihood options; (2) community-based tourism – associated with nature and cultural resources with potentials to involve tour guiding (using village trails and checklists), campsites and camps through partnership, handcrafts production and sales cultural history and entertainments; and (3) activities like poultry, fish farming and gardening – to facilitate provision of goods and services to the growing tourism industry in Serengeti.

The government role is becoming much more of a regulatory, facilitation and advisory which covers aspects including guidelines, technical support, capacity building in entrepreneurial skills and marketing through the genuine involvement and partnerships with the private sector. The success in diversifying household and village economies depends, among other things, on government's ability to protect village lands, and creating opportunities and conditions for local people to be part and parcel of Tanzania's tourism sector.

This study does not preclude the importance of agriculture to food security and poverty reduction, rather it emphasises on improved capacity, quality and delivery of agriculture extension services that would solve the challenges we have identified and discussed. The adequate farming skills and good agriculture extension services would allow application of manure, use of oxen and harvesting of rainwater – all of which are within the reach of local people.

Introduction of compensation to extreme cases of crop destructions, and human injury or death is recommended. In Piyaya, the village has introduced compensation scheme to cover loss from livestock depredation using village natural resources funds generated from ecotourism activities. The initiative by the village tackles people retaliations to problematic wildlife and links benefits from conservation to wildlife conservation (own, unpublished data). This is a best practice, and it is worth replicating it to wider area coverage and in a holistic manner.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism of Tanzania and the Royal Norwegian Embassy (Dar es Salaam, Tanzania) through the Management of Natural Resources Programme (TAN 0092), and is a component of the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute and Norwegian University of Science and Technology – Biodiversity and Human–Wildlife Interface Project. We are thankful to the participation of villages and support from the District Councils, Tanzania National Parks and Tanzania. The first and second time anonymous reviewers provided useful comments to this paper. We especially thank Dr Robert Fyumagwa (TAWIRI) and Craig Jackson (NTNU) for insightful and constructive comments on this paper.

References

- Agrawal , A and Gibson , CC. 1999 . Enchantment and disenchantment: the role of community in natural resource conservation . World Dev. , 27 : 629 – 649 .

- Baldus , RD and Cauldwell , AE. Tourist hunting and its role in development of wildlife management areas in Tanzania . Paper presented at: 6th International Game Ranching Symposium . Paris , France.

- Barnes , JI and de Jager , JLV. 1995 . Economic and financial incentives for wildlife use on private land in Namibia and the implications for policy , Windhoek , Namibia : Ministry of Environment and Tourism .

- Barrett , CB , Reardon , T and Webb , P. 2001 . Nonfarm income diversification and household livelihood strategies in rural Africa: concepts, dynamics, and policy implications . Food Policy. , 26 : 315 – 331 .

- Boone , RB , Galvin , KA , Thornton , PK and Coughenour , MB. 2006 . Cultivation and conservation in Ngorongoro conservation area . Hum Ecol. , 34 : 809

- Borge , A. 2003 . Essays on the economics of African wildlife and utilization and management [Dr. Polit. Thesis] . [Trondheim (Norway)]: Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU ,

- Bryceson , I , Havnevik , K , Isinika , A , Jørgensen , I , Melamari , L and Sonvinsen , S. 2005 . Management of natural resources programme; Midterm Review of TAN 092 Phase III (2002–2006) , Dar es Salaam , Tanzania : Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation .

- Bulte , HE and Horan , RD. 2003 . Habitat conservation, wildlife extraction and agricultural expansion . J Environ Econ Manage. , 45 : 109 – 127 .

- Campbell , K and Hofer , H. 1995 . “ People and wildlife: spatial dynamics and zones of interaction ” . In Serengeti II: dynamics, management and conservation of an ecosystem , Edited by: Sinclair , ARE and Arcese , P . 534 – 570 . Chicago , IL : The University of Chicago Press .

- Campbell , LM and Vainio-Mattila , A. 2003 . Participatory development and community-based conservation: opportunities missed for lessons learned? . Hum Ecol. , 31 ( 3 ) : 417 – 437 .

- Christophersen , K , Hagen , R and Jambiya , A. 2000 . Economic opportunities in the Wami-Mbiki Wildlife Management Area , Dar es Salaam , Tanzania : Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism .

- Distefano , E. 2005 . Human-wildlife conflict worldwide: collection of case studies, analysis of management strategies and good practices , Rome , , Italy : FAO .

- Emerton , L and Mfunda , I. 1999 . Making wildlife economically viable for communities living around Western Serengeti, Tanzania , London , , UK : International Institute for Environment .

- Fall , MW and Jackson , WB. 2002 . The tools and techniques of wildlife damage management-changing needs: an introduction . Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. , 49 ( 2 & 3 ) : 87 – 91 .

- Gabre-Madhin EZ, Haggblade S. 2004. Successes in African agriculture: results of an expert survey. World Dev. [Internet]. 32(5):745–766; [cited 2003 Nov 4]. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6VC6-4BYNMF4-3/2/47934a594f2aaf04358782dda004bf29 (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6VC6-4BYNMF4-3/2/47934a594f2aaf04358782dda004bf29)

- Gadd , ME. 2005 . Conservation outside of parks: attitudes of local people in Laikipia, Kenya . Environ Conserv. , 32 ( 1 ) : 50 – 63 .

- Gibson , CC. 1999 . Politicians and poachers: the political economy of wildlife policy in Africa , Cambridge , , UK : Cambridge University Press .

- Gillingham , S and Lee , PC. 2003 . A preliminary assessment of perceived and actual patterns of wildlife crop damage in an area bordering the Selous Game Reserve . Tanzan Oryx. , 37 : 316 – 325 .

- Hill , CM. 1997 . Crop-raiding by wild vertebrates: the farmer's perspective in an agricultural community in Western Uganda . Int J Pest Manage. , 43 ( 11 ) : 77 – 84 .

- Hill , CM. 1998 . Conflicting attitudes towards elephants around the Budongo Forest Reserve, Uganda . Environ Conserv. , 26 : 218 – 228 .

- Hill , CM. 2000 . Conflict of interest between people and baboons: crop raiding in Uganda . Int J Primatol. , 21 ( 2 ) : 299 – 315 .

- Hill , CM. 2004 . Farmers’ perspectives of conflict at the wildlife-agriculture boundary: some lessons learned from African subsistence farmers . Hum Dimension Wildl. , 9 : 279 – 286 .

- Holmern , T. 2007 . Bushmeat hunting in the Western Serengeti: implications for community-based conservation [degree Doctor Philosophiae] , [Trondheim , Norway : Norwegian University of Science and Technology .

- Holmern , T , Johannesen , AB , Mbaruka , J , Mkama , SY , Muya , J and Røskaft , E. 2004 . Human-wildlife conflicts and hunting in the western Serengeti, Tanzania , Trondheim , Norway : Norwegian Institute of Nature Research .

- Homewood , K , Lambin , EF , Coast , E , Kariuki , A , Kikula , I , Kivelia , J , Said , M , Serneels , S and Thompson , M. 2001 . Long-term changes in Serengeti-Mara wildebeest and land cover: pastoralism, population, or policies? . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA , 98 ( 22 ) : 12544 – 12549 .

- Honey , M. 2008 . Ecotourism and sustainable development: who owns paradise? , 2nd , Washington , DC : Island Press .

- Iwai , Y. 1997 . Subsistence strategies of households in Robanda village adjacent to Serengeti National Park, Tanzania [MSc thesis] , Kyoto , , Japan : Kyoto University .

- Johannesen , AB. 2005 . Wildlife conservation policies and incentives to hunt: an empirical analysis of illegal hunting in western Serengeti, Tanzania . Environ Dev Econ. , 10 : 271 – 292 .

- Kaltenborn , BP , Bjerke , T , Nyahongo , JW and Williams , DR. 2006 . Animal preferences and acceptability of wildlife management actions around Serengeti National Park, Tanzania . Biodivers Conserv. , 15 ( 14 ) : 4633 – 4649 .

- Kaltenborn , BP , Nyahongo , JW , Kidegesho , JR and Haaland , H. 2008 . Serengeti National Park and its neighbours – do they interact? . J Nat Conserv. , 16 ( 2 ) : 96 – 108 .

- Kaltenborn , BP , Nyahongo , JW and Mayengo , M. 2003 . People and wildlife interactions around Serengeti National Park, Tanzania , Trondheim , Norway : NINA .

- Kikula , I , Mnzava , EZ and Mung'ong'o , C. 2003 . Shortcomings of linkages between environmental conservation and poverty alleviation in Tanzania , Dar es Salaam , Tanzania : Mkuki Na Nyota Publishers Ltd .

- Madhusudan , MD. 2003 . Living amidst large wildlife: livestock and crop depredation by large mammals in the interior villages of Bhadra Tiger Reserve, south India . Environ Manage. , 31 ( 4 ) : 466 – 475 .

- Messmer , TA. 2000 . The emergence of human-wildlife conflict management: turning challenges into opportunities . Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. , 45 ( 3 & 4 ) : 97 – 102 .

- Mfunda , I. 2010 . “ Benefit and cost sharing in collaborative wildlife management in eastern and southern Africa: country experiences, lessons and challenges ” . In Conservation of natural resources: some African and Asian examples , Edited by: Gereta , E and Røskaft , E . 166 – 185 . Trondheim , Norway : Tapir Academic Press .

- Mfunda , IM and Røskaft , E. 2010 . Bushmeat hunting in Serengeti, Tanzania: an important economic activity to local people . Int J Biodivers Conserv. , 2 ( 9 ) : 263 – 272 .

- Naughton-Treves , L. 1998 . Predicting patterns of crop damage by wildlife around Kibale National Park, Uganda . Conserv Biol. , 12 ( 1 ) : 156 – 168 .

- Naughton-Treves , L , Treves , A , Chapman , C and Wrangham , R. 1998 . Temporal patterns of crop-raiding by primates: linking food availability in croplands and adjacent forest . J Appl Ecol. , 35 ( 4 ) : 596 – 606 .

- Nyahongo , JW. 2010 . “ The source-sink concept in the conservation of African ungulates: importance and impact of bushmeat utilization from Serengeti, Tanzania and other protected areas in Africa ” . In Conservation of natural resources: some African and Asian examples , Edited by: Gereta , E and Røskaft , E . 237 – 254 . Trondheim , Norway : Tapir Academic Press .

- Osborn , FV. 2002 . Capsicum olesresin as an elephant repellent: field trials in the communal lands of Zimbabwe . J Wildl Manage. , 66 ( 3 ) : 674 – 677 .

- Parry , D and Campbell , BM. 1992 . Attitude of rural communities to animal wildlife and its utilization in Chobe Enclave and Mababe Depression, Botswana . Environ Conserv. , 19 ( 3 ) : 245 – 252 .

- Patterson , BD , Kasiki , SM , Selempo , E and Kays , RW. 2004 . Livestock predation by lions (Panthera leo) and other carnivores on ranches neighboring Tsavo National Parks, Kenya . Biol Conserv. , 119 ( 4 ) : 507 – 516 .

- Prins , HHT. 1987 . Nature conservation as an integral part of optimal land use in East Africa: the case of the Masai ecosystem of Northern Tanzania . Biol Conserv. , 40 : 141 – 161 .

- Rusch , GM , Stokke , S , Røskaft , E , Mwakalebe , G , Wiik , H , Arnemo , JM and Lyamuya , RD. 2005 . Human-wildlife interactions in western Serengeti, Tanzania – effects of land management of migratory routes and mammal populations densities , Trondheim , Norway : NINA .

- Sachedina , HT. 2006 . Conservation, land rights and livelihood in the Tarangire ecosystem of Tanzania: increasing incentives for non-conservation compatible land use change through conservation policy , Nairobi , Kenya : International Livestock Research Institute .

- Scheri , LM , Wilson , A , Wild , R , Blockhus , J , Franks , P , McNeely , JA and McShane , TO. 2004 . Can protected areas contribute to poverty reduction? Opportunities and limitations. Gland (Switzerland) , Cambridge , , UK : IUCN .

- Siex , KS and Struhsaker , TT. 1999 . Ecology of the Zanzibar red colobus monkey: demographic variability and habitat stability . Int J Primatol. , 20 ( 2 ) : 163 – 192 .

- Sitati , NW , Walpole , MJ and Leader-Williams , N. 2005 . Factors affecting susceptibility of farms to crop raiding by African elephants: using a predictive model to mitigate conflict . J Appl Ecol. , 42 ( 6 ) : 1175 – 1182 .

- Smith , S and Sender , JB. 1990 . Poverty, gender and wage labor in rural Tanzania . Econ Polit Week. , 25 ( 24 & 25 ) : 1334 – 1342 .

- Thakadu , OT. 2005 . Success factors in community based natural resources management in northern Botswana: lessons from practice . Nat Resour Forum. , 29 ( 3 ) : 199 – 212 .

- Thirgood , S , Mosser , A , Tham , S , Hopcraft , G , Mwangomo , E , Mlengeya , T , Kilewo , M , Fryxell , J , Sinclair , ARE and Borner , M. 2004 . Can parks protect migratory ungulates? The case of the Serengeti wildebeest . Anim Conserv. , 7 : 113 – 120 .

- [URT] United Republic of Tanzania . 1974 . The Wildlife Conservation Act, 1974 , Dar es Salaam , Tanzania : The Gazette of the United Republic of Tanzania .

- [URT] United Republic of Tanzania . 2006 . Millennium development goals progress report , Dar es Salaam , Tanzania : The Gazette of the United Republic of Tanzania .

- [URT] United Republic of Tanzania . 2008 . Mara region brief profile and development opportunities , Musoma , Tanzania : The Gazette of the United Republic of Tanzania .

- Wainwright , C and Wehrmeyer , W. 1998 . Success in integrating conservation and development? A study from Zambia . World Dev. , 26 ( 6 ) : 933 – 944 .