ABSTRACT

Coffee is generally grown in areas derived from forest, and both its expansion and management cause biodiversity loss. Sustainability standards in coffee are well established but have been criticized while social and environmental impact is elusive. This paper assesses the issue-attention cycle of coffee production in India and Nicaragua, including producer concerns and responses over time to concerns (sustainability standards, public regulations and development projects). Systematic comparison of the socioeconomic, environmental and policy context in both countries is then used to explore potential effects of sustainability standards. Results show limits, in local context, to relevance of global certification approaches: in both countries due to naturally high levels of biodiversity within coffee production systems global standards are easily met. They do not provide recognition for the swing potential (difference between best and worst) and do not raise the bar of environmental outcomes though nationally biodiversity declines. Nicaraguan regulations have focused on the socioeconomic development of the coffee sector via strengthening producer organizations, while India prioritized environmental and biodiversity conservation. In India, externally driven sustainability standards partially replace the existing producer–buyer relationship while in Nicaragua standards are desired by producer organizations. The temporal comparison shows that recently local stakeholders harness improvements through their unique local value propositions: the ‘small producer’ symbol in Nicaragua and certification of geographic origin in India. Nicaragua builds on the strength of its smallholder sector while India builds on its strength of being home to a global biodiversity hotspot.

EDITED BY Beria Leimona

1. Introduction

The ecological range of coffee, especially the higher-valued Arabica coffee, coincides with mountain forests, most of considerable biodiversity and locally relevant as providers of ecosystem services (Dewi et al. Citation2017). Coffee is produced in production systems of varied biodiversity (Perfecto et al. Citation2005). Complex shade coffee systems provide ecosystem services such as pollination, pest control, climate regulation, carbon sequestration, nutrient storage and cycling (Jha et al. Citation2014). However, biodiversity-rich shade production systems are in decline (Jha et al. Citation2014); coffee trade is associated with high negative biodiversity impact (Chaudhary and Kastner Citation2016).

Sustainability standards that arose in response to consumer concerns are widely used in coffee, and supposedly provide signals to consumers that a given product is not associated with negative social and environmental issues. Among tropical tree crops, cocoa, rubber, oil palm, and timber, sustainability concerns date back longest and private standards are most mature in coffee (Potts et al. Citation2014). They aim to provide a market-driven solution to dissatisfaction with public regulation for globally traded goods (Millard Citation2011; Potts et al. Citation2014). Multiple standards have emerged and coexist due to historical ties between producer and consumer countries and the respective country contexts including leading firms and the existence of intermediaries such as producer-organizations and NGOs that drive the uptake of standards in producing countries (Manning et al. Citation2012; Vermeulen and Kok Citation2012). Adoption of sustainability standards by the coffee industry is part of a larger evolving corporate social responsibility strategy (Levy et al. Citation2016). Coffee markets are mature, characterized by small effects of income increases on coffee consumption as well as low price elasticities of supply and demand (Ponte Citation2002). Following liberalization and the abandoning of international coffee agreements, the power in the coffee value chain moved to downstream actors, roasters and multinational corporations (Ponte Citation2002; Taylor Citation2005), resulting in the shift of value addition from producer to consumer countries (Ponte Citation2002; Talbot Citation2002). The highly concentrated coffee market (Ponte Citation2002; Kaplinsky Citation2004) is dominated by three large transnational companies and a few coffee roasters who rely on the services of trading companies, three of which jointly handle 50% of the green coffee bean trade (Panhuysen and van Reenen Citation2012). The prevalence of standards in coffee has further been attributed to the maturity of the market and the high concentration in manufacturing, as well as consumers facing a single ingredient (Alvarez and von Hagen Citation2012).

Global imports of coffee certified to a sustainability standard have steadily increased over the past decade. Several large companies have committed to sourcing sustainably produced coffee (Kolk Citation2012, Citation2013). The three largest coffee roasters purchased 5–7% of their coffee as sustainably certified or verified and aimed to increase the share to 20–30% by 2015 (Panhuysen and van Reenen Citation2012). For some companies, application of sustainability standards is now considered mainstream in business strategies for risk and reputation management while safeguarding core commercial interests (Raynolds Citation2009; Millard Citation2011). Other companies fully subscribe to the missions of the standards as such while quality-oriented companies take a middle ground (Raynolds Citation2009). Standard-compliant production was at an estimated 40% of global production and 12% of global exports in 2012 (Potts et al. Citation2014) but not all certified coffee is sold as such (de Janvry et al. Citation2015).

Sustainability standards in coffee and their impact have attracted considerable research, e.g. studies on the impact of certification to C.A.F.E. Practices and Nespresso AAA in Columbia (Vellema et al. Citation2015), certification to UTZ and Fairtrade in Kenya (van Rijsbergen et al. Citation2016), certification to organic standards in Uganda (Bolwig et al. Citation2009), and certification to Organic standards and Fairtrade in Nicaragua (Beuchelt and Zeller Citation2011). Impact assessment is complex due to a multitude of potentially confounding factors (Lambin et al. Citation2014) as well as indirect and secondary effects that may appear. For example, certified Colombian coffee farmers were found to specialize in coffee production at the opportunity cost of reduced alternative income generating activities resulting in higher coffee but not total household income (Vellema et al. Citation2015). Impact studies mostly focused on economic indicators such as coffee prices and income (Blackman and Rivera Citation2011) but more recently have focused on the impact on environmental indicators (e.g. Ibanez and Blackman Citation2016). Meta studies on the impact of sustainability standards have shown there is still no consensus on the multiple impacts of sustainability standards on smallholder producers and production systems (Blackman and Rivera Citation2011; Bray and Neilson Citation2017).

The researches focus on output – do standards achieve what they aim at? – has been questioned as sole determinant of legitimacy since participation and democratic processes by which sustainability standards are set and implemented also matter in achieving legitimacy (Henson Citation2011; Fuchs et al. Citation2011a, Citation2011b). Complementary to research on impact of sustainability standards on coffee producers, research on coffee value chains has focused on the imbalance of power between smallholder coffee producers and large coffee companies (Talbot Citation2002). Concerns have been raised that sustainability standards may further this imbalance (Kaplinsky and Fitter Citation2004; Daviron and Vagneron Citation2011).

Sustainability standards potentially interact with public instruments of land use governance in terms of potentially influencing agenda setting, implementation and enforcement (Lambin et al. Citation2014). However, systematic research on local socioeconomic and ecological conditions and policy frameworks prior to the introduction of sustainability standards and systematic research on the interactions between sustainability standards and policy frameworks in a particular country are missing (Steering Committee Citation2012). This paper aims to address this gap by a systematic comparison of socioeconomic and ecological conditions and the history of policies that directly and indirectly influence social, economic and environmental sustainability of coffee production in Nicaragua and India. Specifically, the paper addresses the questions:

What are current local issues (i.e. items people are concerned of) and what is the range of best case and worst case agroecological and socioeconomic scenarios (swing potential) in coffee production systems in India and Nicaragua?

Historically what responses (public policies, development and private sector initiatives) have been triggered by concerns?

How do these responses work? Do sustainability standards provide a solution to local sustainability concerns and provide distinctions within the existing management swing potential in coffee production systems?

Finally, in addressing these questions, the paper discusses to what extent contextual factors enable or limit the potential impact of sustainability standards.

2. Analytical framework, methods and description of country case study sites

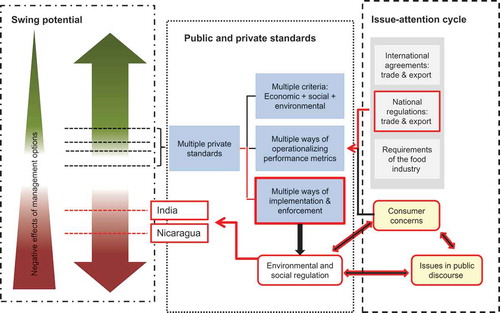

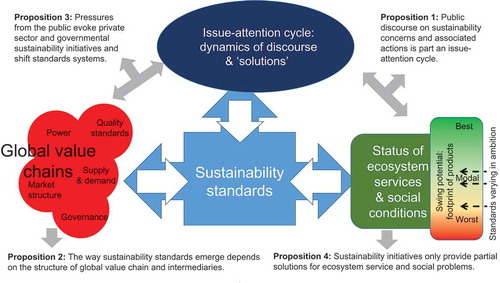

This paper is part of a comparison of five globally traded tropical commodities and is shaped by a common framework, which combines the conceptual perspectives of the global value chain and swing potential concepts as well as the policy issue-attention cycle (Mithöfer et al. Citation2017) ().

Figure 1. Local context and discourse shaping the potential impact of sustainability standards (based on Mithöfer et al. Citation2017).

The global value chain concept elaborates how actors work together across large distances. In particular, it focuses on governance along the chain, which is shaped by suppliers’ capabilities, the complexity of exchange between suppliers and buyers along the different nodes of the chain and the ability to norm the information attached to this exchange (Gereffi et al. Citation2005; Ponte and Sturgeon Citation2013). Sustainability standards increase complexity as they specify multiple attributes a product or the way it is produced has to meet. The management swing potential represents the difference between best and worst ways of producing a commodity, evaluated from a specific angle. It was initially developed to assess greenhouse gas emissions for alternative management regimes in energy crops (Davis et al. Citation2013). It can apply to any single or combined set of sustainability indicators of economic, social and environmental outcomes. Coffee produced on a gradient of diverse shade to monoculture sun grown systems is characterized by a wide swing potential in terms of associated biodiversity and carbon footprint (Vaast et al. Citation2016).

The issue-attention cycle traces stages through which issues gain political prominence, leading to one or multiple public or private policy responses. The cycle has five phases, from initial scoping phase (stage one) in which issues are first acknowledged, through negotiation response at stage three in which solutions are identified and implemented (stage four), to reevaluation response in phase five (Tomich et al. Citation2004). Complementary to Lambin et al. (Citation2014), the framework applied here explicitly acknowledges the temporal dimension of public and private regulatory instruments (Mithöfer et al. Citation2017). Sustainability standards, further private sector and development initiatives as well as public policies constitute responses negotiated to address a concern.

The framework resulted in four propositions (), which were used as a starting point for the present paper. In the framework the lower part of the swing potential is thought to trigger public concerns, which are taken up and move through the phases of the issue-attention cycle resulting in (public and private) interventions addressing concerns (Mithöfer et al. Citation2017). The width of the swing potential defines the solution space and potential impact of interventionsFootnote1; global value chains are a means of implementing private interventions such as sustainability standards in coffee production areas (ibid.). By combining the three concepts, the conceptual framework deliberately connects issues that are often analyzed separately.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework (Mithöfer et al. Citation2017).

The analysis of this paper is based on a geographically focused literature review complemented by observations and information from research projects conducted previously and for different purposes. Literature was identified by search of the Web of Science using the search terms value/supply chain, certification/standard, governance, price/poverty/social, labor, biodiversity/environment and production () and screened so that its content matches the objectives of the present paper as applied to coffee in Nicaragua and India. Scientific publications were not subjected to further quality criteria and were not evaluated for example on frequency of an individual issue.

Table 1. Literature search process on coffee value chains, swing potential and issue-attention cycles in India and Nicaragua.

Complementary to the structured literature review, observations and findings from long-term research in Western Ghats, India (CAFNET Citation2011; Bose Citation2014; Bose et al. Citation2016) and Northern Nicaragua (e.g. Méndez et al. Citation2010a; Baca et al. Citation2013; Jha et al. Citation2014) were integrated in the present paper. This process followed a protocol which standardized information of the grey literature to be collected through author networks and from previous projects for all commodity case studies of this Special Issue. The data collection protocol included data to be collected on commodity statistics in each country, the contribution of the commodity to local livelihoods, an enumeration of local issues as well as and inventory of development projects and policies that addressed these issues over time. The protocol also collected information on actors involved in the uptake of sustainability standards in the local site as well as the identification of other actors involved. The sequence of the results sections follows the stages of the issues attention cycle: we first identify current concerns, then look back on how concerns have been addressed over time and finally reevaluate how well responses have worked from the present perspective. The discussion section compares the results between the two countries and the current scientific debate at global level.

The two countries and sites were selected from a portfolio of ‘sentinel landscapes’ that are representative of agro-ecological systems, forest transition and population density and were selected to carry out long-term monitoring of rural development and environmental sustainability in the Tropics (see Dewi et al. Citation2017). In both sites, issues with regard to the provision of ecosystem services include the expansion of highland crops (coffee and tea), overharvesting of timber and vulnerable biodiversity amongst others (Dewi et al. Citation2017).

Historically, Nicaragua’s dependence and political focus on coffee has been higher than in India (Gilbert Citation2005) although in India coffee also sustains livelihoods and provides employment in coffee producing areas (Neilson and Pritchard Citation2010b). Both countries have been subject to intense research on coffee. Indian coffee production has switched from Arabica to increased production of Robusta coffee for the bulk market and has faced increased competition of Brazil and Vietnam (Chengappa et al. Citation2014). Nicaragua constitutes a major producer of Fairtrade coffee (Valkila et al. Citation2010) and coffee is a major contributor to the national economy and job market (Bacon et al. Citation2008b). The study sites Kodagu district in the Western Ghats, India () and in Northern Nicaragua (), are the major coffee producing areas in these two countries. In Nicaragua, a major recurring theme in the literature is agrarian change and the development of the cooperative sector while in India attention in the case study site is mostly on its biodiversity value.Footnote2 This is reflected in the number and focus of publications on socioeconomic versus environmental topics ().

In 2012, India contributed 4% and Nicaragua 1% to global coffee production, while yields roughly matched the global average (FAOSTAT Citation2016) (). In 2011, India represented 3% and Nicaragua 1% of global coffee export volume. Since 2002, the value of coffee exports has increased in both countries at much steeper rates than coffee volumes.

Figure 3. Areas allocated to coffee production and exports in Nicaragua and India (based on FAOSTAT Citation2016).

Box 1. Description of the case study site: The Western Ghats, India.

Box 2. Description of the case study site: Northern Nicaragua.

Coffee exports contributed 5% to GDP for Nicaragua in 2012 and less than 1% to India’s GDP (FAOSTAT Citation2016). Domestic consumption is low in both countries (ICO Citation2016). Exports of processed coffee constitute 41% of green coffee exports in India and about 3% in Nicaragua. In 2014, Indian coffee farmers received an average of USD 1.76/lb for wet-processed Arabica and $US1.05/lb for Robusta; Nicaraguan coffee farmers received an average of USD 0.7/lb for wet-processed Arabica (CitationICO undated-b).Footnote3 Nicaragua contributes 10% to global organic coffee exports while that of India is negligible (ICO Citation2013). India chiefly exports to Italy (31%) and Germany (16%) while Nicaragua mostly exports to the USA (48%) and Germany (5%) (ITC Citation2015).

3. Issues addressed by global sustainability standards and reevaluation at global level

Sustainability standards, built on early initiatives concerned with soil health and fair producer prices in the 1970s and 1990s, respectively (Soto and Le Coq Citation2011), now cover a range of initiatives with differences in focus and initiators (). They comprise the standard (defining the norms), the assurance system (conformity assessment: making sure and providing proof the standard is adhered to), often a label and capacity building (Milder et al. Citation2015). Producers seeking recognition for adherence to voluntary standard are regularly audited – usually by a third party – against these preset criteria. Standard development and conformity assessment can be held by separate actors. Voluntary sustainability standards encompass those labeled on the product contributing to brand development and those that serve in business-to-business communication for risk management and defining entry barriers (Potts et al. Citation2014). Standards provide for individual as well as group certification, the latter to address the needs of smallholders.

All standards reviewed in the context of this paper require adherence to national law, in particular to labor laws. Varied focus is placed on establishing management systems. The Sustainable Agriculture Standard (SAN), which is assured by the Rainforest Alliance seal, requires establishment of a social and environmental management system while UTZ requires an internal management system by which member compliance is assured (). Incorporation of a premium in the pricing strategy differs by standards; it is a major component of Fairtrade. Despite the oversupply, and hence international price volatility, and not being part of standard specifications, price premiums may be part of the actual contract in order to retain highly qualified suppliers within the supplier pool (Swinnen and Vandeplas Citation2011).

Although voluntary sustainability standards were initiated by separate concerns, they have converged on some common issues over time.Footnote4 Currently all standards considered here stipulate adherence to principles of integrated pests and diseases management, including handling, storage and spraying of chemicals with protected gears, and ban substances black-listed by international agreements such as the Stockholm Convention. Organic agriculture bans the use of synthetic agro-chemicals. All standards ban the use of child labor (under age 15) unless children help parents and education is not compromised. Maintenance of shade is explicitly detailed only by the SAN as a non-compulsory development criterion and by UTZ to be established in year three following certification initiation (). Further environmental criteria include those enhancing sustainable management of soil, biodiversity, waste and water. Criteria on business development skills and farmer training are more recent and the extent of their inclusion differs among standards. The number of criteria in any dimension does not necessarily reflect comprehensiveness, nor does it reflect the strictness of the requirement stipulated, and nor does this reflect local understanding and strictness in implementation. First published in 2004, ISEAL’sFootnote5 standard-setting code assures representation of different stakeholders’ views during standard setting and aims to balance global and local interests (ISEAL Citation2014). Over time and in collaboration with other stakeholders, standards have move beyond plot and farm levels to address larger issues at landscape level. For example, the most recent update of the 2017 SAN Standard requires farms to maintain high conservation value areas and natural ecosystems (SAN Citation2017).Footnote6

Table 2. Initiators, motivation and implementation of national laws and management systems of selected sustainability standards in coffee.

Certification schemes have mostly been developed for Arabica coffee, the high quality coffee preferred by northern consumers. Both social and environmental standards do not directly address quality, but none of the buyers and roasters that specialize in certified coffee or their own company standards buys coffee of poor quality.

Over time different actors have partnered to work jointly towards a sustainable coffee sector (Bitzer et al. Citation2008). The International Coffee Agreement of 2001 focused on a sustainable coffee industry (CitationICO undated-a). The International Coffee Agreement of 2007 focusses on benefits for local communities and small coffee producers (CitationICO undated-a). In 2015, a large public-private partnership was formed when the International Coffee Organization (ICO), the 4C Association and The Sustainable Trade Initiative (IDH) signed a Memorandum of Understanding for a ‘Long-Term Sustainability of the World Coffee Market’ (ICO Citation2015), one component of which is to develop national sustainability curricula (NewForesight Consultancy Citation2015).

Beyond larger coalitions which included additional actors, recently actors have merged to harness synergies between programs of work and/or to increase efficiency in supply chain operations by cutting costs. The 4C Association merged with the Sustainable Coffee Program in 2016 forming the Global Coffee Platform which now harnesses synergies of either program and is a business-to-business scheme (GCP Citation2017). Recently, the SAN standard and UTZ merged (late 2017) in order to reduce cost of standard implementation and the assurance systems while combining the strength of either standard (Rainforest Alliance Citation2017).

Although sustainability standards are predominantly part of industry self-regulation, voluntary and private, they interact with government actions via multiple channels, including funding and support of particular NGOs, political support to sustainability initiatives and regulation of public procurement (Kolk Citation2012; Vermeulen and Kok Citation2012).

Sustainability standards in coffee have been interpreted as (1) steps toward standardization of sustainability attributes to increase efficiency in supply chains at the expense of smallholder producers (Daviron and Vagneron Citation2011), (2) a way to establish traceability and manage risks (Raynolds Citation2009; Levy et al. Citation2016), (3) a driver of structural change (Neilson Citation2008), (4) a strategy to capture market gains (March Citation2007), and (5) a business strategy of retailers and roasters aiming at product differentiation and market segmentation (Ponte Citation2002). Voluntary sustainability standards have been shown to be adopted by large companies to achieve business goals rather than as a response to consumers’ pressure (Elder et al. Citation2014). Voluntary sustainability standards can be de facto mandatory constituting an entry barrier to the market in case they are required in buyer supplier contracts (Neilson and Pritchard Citation2010b). Companies have been shown to abandon voluntary sustainability standards once their own systems are set up (Kolk Citation2012). Recently, de Janvry et al. (Citation2015) showed that under current rules and in a competitive market Fairtrade results in erosion of producer benefits in terms of price premiums due to lack of entry barriers to the scheme. The authors conclude that consumers should better support producers directly than through such market mechanisms (de Janvry et al. Citation2015). However, beyond prices and premiums coffee producer livelihoods also benefit from other factors such as training on best practices, access to inputs, access to financing and access to markets (see e.g. Bray and Neilson Citation2017).

4. Current local issues and swing potential in the country case study sites

4.1 Western Ghats, India

Like many biodiversity-rich areas across the globe, the Western Ghats is undergoing rapid transformation (Gaucherel et al. Citation2016). Menon and Bawa (Citation1997) estimate that 40% of the natural vegetation was lost from 1920 to 1990 with open/cultivated lands, coffee and tea plantations and hydroelectric reservoirs, of which coffee plantations accounted for 16% of forest cover lost. Coffee farms have spread from low-elevation moist deciduous forests to montane evergreen forests. Garcia et al. (Citation2010) suggest that in some coffee production districts, 30% of forest cover was lost between 1977 and 1997 while the area under coffee doubled (Lal et al. Citation1990). Coffee has also been shown to invade forests and forest fragments (Joshi et al. Citation2009).

Since the early 1990s, there have been significant changes in the canopy cover of coffee plantations. There are numerous drivers for these changes, including the shift from growing Arabica to Robusta coffee. Currently, Robusta dominates 70% of total coffee production. While this shift to Robusta was motivated primarily due to easier management and better pest resistance, it has had unintended consequences on the reduction of tree canopy cover on coffee plantations as Robusta requires less buffering effects of shade than Arabica. Additionally, the increased development of irrigation areas has reduced the need for shade cover in the dry, summer months (Central Ground Water Board Citation2007; Garcia et al. Citation2010; Boreux et al. Citation2013a). Easy availability and application of agrochemical fertilizers have greatly replaced the use of organic manure originating from leaf litter and tree pruning. Finally, newly developed varieties of coffee more resistant to heat and drought are replacing older varieties.

As coffee farmers have become less dependent on ecosystem services provided by forest trees, such as microclimate regulation in the form of temperature and humidity control and provision of organic matter, native shade trees are being replaced by exotic species such as Grevillea robusta (Garcia et al. Citation2010; Nath et al. Citation2011, Citation2016). Such exotics are fast-growing, and often, as in the case of G. robusta, serve as living stand to pepper vines (Piper nigrum) and are marketable for timber without restriction imposed on native species (Garcia et al. Citation2010; Nath et al. Citation2016). The planting of G. robusta is seen by coffee farmers as a source of contingency funds in the event of a drastic fall in coffee prices, or urgent or exceptional needs such as medical expenses, familial events such as wedding or burial.

Apart from these environmental concerns, economic and social concerns prevail () such as volatile coffee prices (Ambinakudige Citation2009) and structural changes in rural areas triggered by changes in international market demand (e.g. increased importance of quality parameters leading to industry models of working through purchasing agents for risk sharing versus direct contracting (Neilson and Pritchard Citation2010b)). Similar to findings of Soto-Pinto et al. (Citation2000) and Perfecto et al. (Citation2005), productivity of coffee is less under high-shade cover conditions () (Chethana et al. Citation2010). Arabica coffee brings back higher net returns than Robusta (Chengappa et al. Citation2014) but is more susceptible to pests than Robusta.

Table 3. Current social, economic and environmental issues in the Western Ghats, India and Northern Nicaragua.

Table 4. Swing potential: Minima and maxima reported for sustainability indicators of coffee farming systems in Nicaragua and India.

4.2. Northern Nicaragua

One of the most significant environmental threats facing Nicaragua and other coffee producing countries is the conversion of shade coffee to more intensive production with simplified or no shade at all (Jha et al. Citation2014) (). Simplified systems, made of one shade stratum composed of one or few tree species, not only lose many environmental benefits provided by a diversified shade canopy, but they also generate negative environmental impacts as they increase the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. In addition, concerns exist regarding the impacts of climate change, especially increasing temperature and variability in rainfall patterns, which could affect production, quality and value of coffee at elevations that are optimal at present, but could become suboptimal in the future (Baca et al. Citation2014; Bunn et al. Citation2015). Recent research shows the negative effects of climate change and corn-price fluctuations on food security for Nicaraguan smallholder farmers (Bacon et al. Citation2014).

From a social and economic perspective, smallholders and cooperatives face persistent livelihood issues. Poverty levels remain high and seasonal food insecurity over several months of the year is common. In part, this is due to the instability of coffee as a cash crop, with prices fluctuating within and between years (Wilson Citation2010). In addition, some farmers, heavily dependent on coffee, have abandoned a more diversified livelihood strategy, resulting in high levels of vulnerability. Indebtedness is a persisting major structural problem for Nicaraguan smallholder coffee producers triggered by the coffee crisis and the drop of coffee prices in 2000 (Wilson Citation2010). Development of the private agro-export sector led to the appropriation of formerly worker-owned coffee plantations leading to job losses and food insecurity of coffee workers before land was actually redistributed to a share of the workforce (Wilson Citation2015). Organic as well as noncertified coffee farmers experience periods of food insecurity during the months prior to the coffee harvesting which is due to variability in annual rainfall cycles, rising maize prices, and low coffee harvests and volatile coffee prices (Bacon et al. Citation2014).

Numerous studies compared production systems via social and economic indicators () contributing to an assessment of their swing potential. Mean coffee yields vary greatly between surveys from 354 kg/ha in a 2007 survey (Beuchelt and Zeller Citation2011) to 1561 kg/ha in a 2010 survey (Jena et al. Citation2017). Organic coffee fetches the highest prices although varying strongly according to buyers’ origin (private traders versus cooperatives). It is followed by Fairtrade and conventional systems (Jena et al. Citation2017).

5. Responses to concerns over time in the case study countries

5.1. Western Ghats, India

In Kodagu, legal and policy frameworks constitute a bottom line for many of the critical criterion of sustainability standards (). These policies are indicators of responses to past issues. Workers’ rights on farms have been protected from 1951 onwards while environmental issues such as the conversion of protected areas to coffee has addressed by the Wildlife Protection Act of India of 1972. With respect to biodiversity, the focus has centered on protected areas and exotic wildlife species, such as the tiger or Asian elephant (Sodhi et al. Citation2010).

Table 5. Government and private sector instruments influencing sustainable coffee chains in Nicaragua and India.

In the Western Ghats, Rainforest Alliance, Organic and UTZ Certified are active since 2008 and 2009, respectively. Certification to Rainforest Alliance and UTZ Certified was driven by the research project, CAFNET,Footnote7 in collaboration with certified buyers and auditing companies with financial support to UTZ Certified from the Dutch government. Following awareness-raising meetings from 2009 to 2010, individual coffee farmers as well as farmers’ groups formed groups of coffee producers that followed the standard specifications. CAFNET carried out pre-certification monitoring along with representatives of a key buyer of certified coffee during which the team evaluated the coffee farms against certification standards. Three rounds of pre-certification monitoring were carried out in which the CAFNET team and the certified buyer made suggestions for improvement and ensured that farm management, including book-keeping, labor facilities, and drying yard, complied with the requirements of Rainforest Alliance or UTZ Certified. The final certification audit was carried out by an independent auditing company and the audit report was forwarded to Rainforest Alliance and UTZ Certified, based on which farmers were conferred an official certificate. The certificate, jointly owned by the certified buyer and the individual coffee farmer, specifies that coffee from certified farms could be sold as certified coffee only if sold directly to the certified buyer. If certified farmers wish to sell their coffee to alternative traders or exporters, the exporter cannot use the certification label. In Kodagu, the certified buyer covers the certification fees and audit expenses on behalf of farmers, but in return farmers enter into a contract wherein they are only able to sell certified coffee to that particular certified buyer. The certified buyer provides a premium for certified coffee that ranges from Rs50 ($US1) to Rs100 ($US2) per 50-kg bag of Robusta cherry and Arabica parchment, respectively (CAFNET Citation2011; Bose Citation2014). Following this initial process, a total of 187 producers has been certified in the study site (from a total of 43,775 producers) (Marie-Vivien et al. Citation2014). Two large buyers constitute the largest buyers of certified coffee and now drive certification by actively recruiting producers to participate. The current process of obtaining certification no longer entails the collaboration of the CAFNET project. Nowadays, coffee farmers and buyers liaise directly, and buyers carry out pre-certification audits. The buyer still covers costs of auditing and certification and the certificate is still jointly owned. The premium for certified coffee ranges from 2% to 5% of the market price, depending on price volatility, and whether it is Robusta, Arabica or green bean coffee (Bose Citation2014). Multinational exporters and large traders offer two major incentives: (a) reliability of payments in comparison to small traders who are often short of cash or even go bankrupt, and hence are unable to pay producers on time; and (b) information on coffee quality in the form of a formal report on quality parameters such as moisture and bean quality, particularly bean size and % of bean damaged (CAFNET Citation2011; Marie-Vivien et al. Citation2014).

5.2. Northern Nicaragua

Poverty and landlessness coupled with political unrest and changes triggered agrarian reforms in Nicaragua (from 1979 onwards) and the development of a strong cooperative system, which was the entry point of the strong Fairtrade movement in the country (Fraser et al. Citation2014; Bruce Citation2016) (). Following the agrarian land reforms, market deregulation and privatization of technical and extension services in the 1990s resulted in stronger direct ties between smallholders, NGOs (offering technical assistance) and buyers (Méndez et al. Citation2010b), stronger producers’ organizations and development of the sustainably certified coffee sector (Bacon et al. Citation2008b). The Nicaraguan government has focused strongly on strengthening farmers’ cooperatives. Maintenance of shaded coffee systems, deforestation and biodiversity loss are directly and indirectly addressed by the ratification of the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the laws on food sovereignty, organic and agroecological production. However, the laws have no teeth and certifiers have pressured farmers to also undertake environmental measures.

Government policy instruments, such as food security and coffee laws, have the potential to leverage efforts for the improvement of the livelihoods of Nicaraguan coffee farmers. However, most of the advances to date have been accomplished by cooperatives with the support of coffee companies and NGOs.

Nicaragua has been a regional innovator in the development of the high value or ‘specialty’ coffee sector negotiated through second- and third-level smallholder farmers’ cooperatives. The solidarity networks that stemmed from the Sandinista revolution were important in connecting Nicaraguan producers to early Fairtrade efforts in the 1980s and to the USA and European solidarity networks. Cooperatives first leveraged Fairtrade certification through social and land solidarity networks, including the National Union of Farmers and Livestock Producers founded in 1981, and with a strong link to the Sandinista revolution and its international networks. Others supporting this process included faith-based organizations from the USA and Europe, including Catholic Relief Services (CRS) and the European Interchurch Organization for Development Cooperation. By the mid-1990s, and with support from these networks, many of the larger cooperative unions had achieved Fairtrade certification. In the 2000s, these unions promoted a combined Fairtrade/Organic certification, in part due to a demand from buyers, and the presence of NGOs supporting Organic certification (Valkila Citation2009). There has been an increasing tendency from cooperatives to seek certification through regional certifiers, as thus reduce costs compared to the international agencies based in the USA and Europe.

Fairtrade has been seen as a first useful step in market integration on which Rainforest Alliance and Café Practices from Starbucks Company have built on for subsequent productivity improvement (Ruben and Zuniga Citation2011). Rainforest Alliance initially worked with large-scale coffee producers and placed little focus on coffee system components important to small-scale producers such as medicinal plants and food crops (Méndez et al. Citation2010b).

Other actors from the coffee sector include the National Coffee Council (CONACAFE), the Nicaraguan Association of Specialty Coffees, the Union of Nicaraguan Coffee Producers and several organizations specifically representing exporters and processors. Although these organizations have become increasingly involved with specialty and certified markets, they tend to be heavily influenced by larger producers and exporters, with limited involvement from the cooperative sector. Regional actors of relevance include the Interamerican Institute for Cooperation in Agriculture (IICA), the Tropical Agriculture Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE) and the Cooperative Regional Program for the Modernization and Development of Coffee (PROMECAFE) in Central America. These national and regional institutions play active roles in a program aiming at enhancing competitiveness, diversification and food security of the Nicaraguan coffee sector (MAGFOR et al. Citation2008).

6. Reevaluation: how do responses perform, and what secondary effects emerge?

6.1. Western Ghats, India

Coffee, produced in multi-strata agroforestry systems, is grown under a mosaic of different tree species. The average coffee farms in Kodagu district ranged from commercial polyculture to rustic,Footnote8 with an average shade cover of 40% and tree species richness of 53 species/ha (CAFNET Citation2011) (). As a district average, tree densities on plantations and smallholder farms range from 285 to 1,471 trees/ha, comparable to surrounding deciduous and evergreen forests (Desjeux Citation1999). Fast-growing and timber-valuable exotics such as Grevillea robusta comprise approximately 23% of the canopy (Bose Citation2014). Producers use a combination of organic and chemical inputs to enhance production and control pests and diseases outbreaks.

The production system currently adopted by certified producers is almost identical to that of noncertified producers (Bose et al. Citation2016). Certified farmers fall within a spectrum of shade-management types from commercial polyculture to rustic plantations. The average density of native trees was significantly lower on certified farms (169 trees/ha) than conventional ones (271 trees/ha). The percentage of G. robusta on certified plantations (29% of total trees) was marginally higher than noncertified farms (23% of total trees) (CAFNET Citation2011). The existing density of native trees on certified farms – though lower than on noncertified farms – is more than ten times higher than the requirement of Rainforest Alliance (cf ).

Table 6. Number of compliance criteria and description of selected criteria by sustainability standard.

The regional member organization of the Sustainable Agriculture Network (SAN), Nature Conservation Foundation, India, held initially a series of workshops to develop Local Interpretation Guidelines (LIG). The objective of these LIG was to tailor the Rainforest Alliance standards to the local context with particular relevance to local laws, institutions and policies. Key stakeholders such as coffee producers and environmental organizations were requested to contribute to this consultative process. This process gave voice to concerns such as the feasibility of ‘establishing a social and environmental management system’. Maintenance of tree density was seen as straightforward; however, maintaining a diversity of native tree species was more challenging, especially in the absence of clear guidelines regarding which species to plant or conserve and specific benefit for coffee.

Despite the initial momentum, these LIG have not as yet been approved and circulated among key stakeholders. Correspondence with Rainforest Alliance indicated limited scope of the LIG in triggering modifications to the global Rainforest Alliance standards in addressing producers’ concerns for a separate set of standards for small-farmers, or revised shade criterion integrating both tree density and tree diversity that were locally more relevant.

Individual coffee plantations undergo marginal modifications to management practices in order to qualify for certification, mostly changes are related to documentation of management practices (Marie-Vivien et al. Citation2014; Bose et al. Citation2016). This is partially due to the low-management swing potential in the landscape given its naturally high biodiversity, predominance of coffee shade management, and local regulatory systems, as well as the lack of local adaptation of global certification standards.

On the economic and social sides, as producers are legally bound to sell coffee as ‘certified’ only to specific certified buyers, independent marketing of certified coffee is impaired. The emergence of certified buyers has changed local dynamics between producers and traders: Local traders keen to buy regular coffee appear to offer prices that match prices including the certification premiums of large multinational coffee exporters. Most producers have established long-term relationships with traders, having sold their coffee to specific local merchants for generations; switching to a multinational exporter is not necessarily seen as a more profitable or promising move (Bose Citation2014).

Certified coffee producers enjoy no tangible advantage in access to markets. Due to the high demand for the good-quality coffee produced in the Western Ghats coffee farmers are able to negotiate competitive prices with noncertified buyers even by selling their coffee as noncertified. Most certified farmers sell the majority of their coffee uncertified, with an average of 30%–40% of coffee sold as certified. Furthermore, despite the price premium for certified coffee, certified producers are found to receive similar overall prices compared to noncertified farmers. Some certified farmers have actually faced price deductions because the certified buyer claimed that the coffee was of inferior quality. For example, for consignments where the coffee berries retained a moisture level greater than 10%–10.5%, a total of 1% of the base price was deducted. Additionally, if the weight of the final green coffee of a Robusta consignment following the full process was lower than 52% of the dry Robusta cherries sold at farm gate, a total of 1.9% of the base price was deducted for every 1% decrease in out-turn (Bose Citation2014).Footnote9 Similarly, if the concentration of ‘bits, browns and blacks’ measured was higher than 7%, additional deductions were carried out. Conversely, price increments are rewarded for coffee of high quality, measured through optimum moisture, out-turn levels and reduced impurities. As a large number of certified farmers has faced quality deductions, this has unsurprisingly caused considerable disenchantment with the process of UTZ or Rainforest Alliance certifications (Bose Citation2014).

As a result of the certification process, certified producers have access to the agronomic support provided by certified buyers. This includes training support as well as detailed information on coffee quality. Information on coffee quality appears to be a major differentiator between certified and conventional systems and, as a result, a major incentive/disincentiveFootnote10 to participate in certification.

Government policies have also evolved over time. Awareness of the Karnataka Preservation of Trees Act of 1976 is widespread among coffee producers and timber merchants. However, the law has been contested, demanding that full rights to harvest native tree species be assigned to individuals (Garcia et al. Citation2010). More recent policies such as the National Environmental Policy and National Biodiversity Action Plan focus on the dual aims of natural resource conservation and livelihood benefits by promoting economic incentives for biodiversity conservation (GoI Citation2008, Citation2011) ().

Disenchantment with the low spread and poorly perceived contribution of sustainability standards to biodiversity conservation gave rise to exploring the potentials of branding the landscape, trademarks and labeling of geographic indicators aiming at recognizing and valuing the biodiversity at landscape level via economic incentives (Chengappa et al. Citation2014; Marie-Vivien et al. Citation2014). To what extent such initiatives will be able to eliminate the drivers of biodiversity loss and land use changes remains to be seen.

6.2. Northern Nicaragua

Nicaragua provides an example where strong services suppliers to rural communities, i.e. in the form of highly organized cooperatives, were able to utilize a variety of networks to implement a diversity of sustainable voluntary standards. In Northern Nicaragua, the larger second- and third-level cooperatives started with Fairtrade in the late 1980s, and – mostly under the umbrella of CAFENICA – within a decade had successfully added Organic certification (Valkila Citation2009). By 2007, up to 5% of Nicaraguan coffee was certified organic, and most of this was done via Fairtrade representing an estimated 9,000 farmers producing 10.7 million kg of coffee (Valkila Citation2009).

However, informal visits (between 2011 and 2015, 1–2 visits per year) by one of the authors of this study to Northern Nicaragua yielded comments by cooperative staff and members on how many farmers had decided to abandon organic certification. Reasons included the high amount of labor required; persistently lower yields, and small premiums that did not provide sufficient return on investment. As part of a long-term research project to assess changes in livelihood over a seven-year period, Caswell et al. (Citation2014) surveyed over 100 households in three countries and included questions related to the performance of sustainable coffee certified markets. In Nicaragua, the 11 households surveyed were members of at least a first-level cooperative and a second-level cooperative union, and all within the study site. Farmers reported selling to five different types of specialty markets, in addition to the conventional market, including Fairtrade, Organic, Fairtrade & Organic and other certified markets. They reported selling coffee as ‘uncertified organic’. Farm gate price performances showed an upward trend from 2006 to a peak in 2011 and then decline in 2012. For the 2012/13 harvest, Fairtrade had the highest average price with US$0.75/lb, followed by conventional coffee at a mean average price of US$0.65/lb while Fairtrade/organic and noncertified had the lowest prices (US$0.45/lb and US$0.44/lb, respectively) (Caswell et al. Citation2014). The price decline is a cause of farmers dis-adopting organic production. This situation was probably worsened by the recent leaf rust epidemic which severely affected organic farmers.

Though Nicaragua has signed the core convention of the International Labor Organization, compliance is not assured (Valkila and Nygren Citation2010). Although Nicaraguan coffee cooperatives are well positioned to enhance the livelihood of their members, a large number of studies in the country continue to report precarious situations for farming families. Preexisting conditions related to the lack of livelihood assets and social infrastructure remains one of the largest challenges (Donovan and Poole Citation2014). Livelihood changes for the better will come from more comprehensive interventions, including those targeting enhancements of value chains and certified markets, but also those considering issues of food security, livelihood diversification and political advocacy (Méndez et al. Citation2010a; Bacon et al. Citation2014; Donovan and Poole Citation2014). Of key importance is the consolidation and strengthening of cooperative organizations in the areas of governance, accountability, administrative capacity and business skills to access and deal directly with international market and clients. All of these represent long-term issues that require integrated and consistent investment. Although Nicaraguan second- and third-level cooperatives take full advantage of the contributions that certifications make in terms of price and other support (capacity building and linking to networks), as well as acquiring visibility for their certified products, they critique low premiums and a lack of participation in the definition of certification standards and governance. The Small Producer Symbol (SPP) is a response to disenchantment with the mainstream direction taken by Fairtrade. SPP values the identity and the economic, social, cultural and ecological contributions of products from Small Producers’ Organizations (SPP-FUNDEPPO Citation2016).

Overall, Nicaraguan cooperatives have earned a high reputation with their buyers in terms of trust and maintenance of standards for certified coffees (Méndez, personal observation and communications with a variety of roasters, including Keurig Green Mountain, Cooperative Coffees, Equal Exchange and Dean’s Beans). In addition, some cooperative organizations in the Northern region are going beyond certifications to improve the conditions of their communities and landscapes from both social and environmental perspectives with the help of international organizations, such as CRS, Save the Children, Heifer International and considerable funding from Keurig Green Mountain. For example, the UCA San Ramón cooperative in Matagalpa has an established agro-ecotourism project and is now seeking to develop a cooperative-level environmental management plan. Well-established cooperatives maintain good links to buyers and development projects offering coffee prices to their members higher than those of Fairtrade (Donovan and Poole Citation2014).

With regard to environmental swing potential, there is no conclusive evidence to the contributions that sustainability standards might have made over time to reducing the pace of shade trees loss (as documented globally by Jha et al. Citation2014) or the maintenance of tree diversity (as documented locally in San Ramon, Nicaragua by Goodall et al. Citation2015).

7. Country comparison and discussion of enabling and limiting contextual factors

Sustainability standards are private instruments of land use governance that interact with public instruments of land use governance at three levels: where the bar is set, how it is being met and systems to verify actors’ behavior on a continuum of complementarity, substitution and antagonism (Lambin et al. Citation2014). Corporate social responsibility in sustainable coffee has been a continuous temporal process in which corporations have responded to interventions by NGOs by adoption of sustainability standards, further collaboration in umbrella organizations as well as further company own strategies (Levy et al. Citation2016). In this temporal process, sustainability standards are caught between the conflicting needs for alignment and differentiation (Reinecke et al. Citation2012), aspirations of global relevance in locally differing contexts.

Clearly, the context differs amongst countries and furthermore is dynamic over time (Tomich et al. Citation2004; Mithöfer et al. Citation2017). Hence, interaction between public and private instruments is dynamic over time. At first glance, all standards considered in this paper address multiple concerns. Recently, standards placed greater focus on training, productivity and business development. Local regulatory contexts provide the foundations, on which sustainability standards can build. The regulatory framework in Nicaragua has been characterized by strong support for economic development of the coffee sector, particularly the sound development of cooperatives. Here, government instruments, such as coffee and food security and sovereignty laws provide a baseline on which standards can build to leverage sustainable coffee production. Following Lambin et al. (Citation2014) in Nicaragua, public and private instruments for social and economic development goals have been complementary in agenda setting and implementation over time. In India, the regulatory framework constitutes a reasonable baseline to social and environmental concerns with greater focus on environmental issues ().

In both countries, the management swing potential between best and worst management practices with respect to key environmental factors is low with some differences between production systems (). In India, most farm management practices are moderately to highly sustainable and quite similar in terms of shade management, chemical inputs and soil and water contamination (CAFNET Citation2011). In the past (up to the 1990s), the international coffee trade put greater emphasis on farmers meeting sanitary and phyto-sanitary requirements than on complying with environmental policies at the expense of coffee landscape health (Damodaran Citation2002). In India, the high biodiversity value of the landscape facilitated easy certification to sustainability standards (Bose et al. Citation2016). Local conditions (e.g. in terms of biodiversity value) are far above the threshold stipulated by the criteria of sustainability standards. Adaptation of the standards to local conditions in terms of ‘raising the bar’ (Raynolds et al. Citation2007) following local consultations has not yet been implemented. Therefore, standards present in India are not in the position to increase the provision of ecosystem services via an enhanced biodiversity protection and maintenance of diversified shade tree cover on coffee farms. The current certification models maintain the status quo with respect to coffee management practices (Bose et al. Citation2016). Standards set below the status quo run the risk of discouraging local coffee stakeholders (Bose et al. Citation2016) and also the risk of being perceived as promoting corporate greenwashing (Gorrie Citation2009). They further may undermine the set of stronger public instruments (cf. Lambin et al. Citation2014).

Table 7. Market access, value chains and swing potential of coffee systems in Nicaragua and India.

In Nicaragua, strong cooperatives and direct ties to their buyers provide a platform on which standards built on. Development programs and direct links to buyers strengthened coffee cooperatives and contributed to coffee quality knowledge and infrastructure for improvement of coffee quality (Bacon Citation2013) as well as processing infrastructure (). In India, smallholder coffee farmers are not organized in cooperatives (Neilson and Pritchard Citation2007; Upendranadh Citation2013), hence sustainability standards started working with larger farms before moving on to work with independently operating smallholder coffee farmers with support from a research project (CAFNET Citation2011; Chengappa et al. Citation2014; Marie-Vivien et al. Citation2014). Nicaraguan smallholders are well positioned to balance global buyers’ power because they are represented by strong advocacy organizations in the form of third-level cooperatives, and CAFENICA at national level. These organizations are well positioned to advocate for smallholders in government and private initiatives. Indian smallholders do not have this advocacy power, but still successfully compete at the global coffee market due to the efficiency of the well-working historical producer–trader spot-market relations and the international reputation of coffee quality produced in the Western Ghats. The international reputation results in high coffee prices on international markets, and this despite the low economic and environmental benefits from coffee differentiation via sustainability standards relative to the existing production and marketing systems. In Nicaragua, these coffee organizations have recently leveraged support to address underlying structural issues and diversification of income sources, hence, improved their position in the value chain (also referred to as ‘upgrading’ Humphrey and Schmitz Citation2001).

While swing potential with regard to environmental aspects is low in the Western Ghats, structural, social and economic inequalities prevail between production systems, particularly between coffee plantations and smallholders’ farms. The Plantation Labour Act of India dated from 1951 only concerns plantations over five hectares (John and Mansingh Citation2013), plantations were found to qualify for certification to UTZ Certified on labor requirements without having to implement further changes (Neilson and Pritchard Citation2010a) and small farmers were found to provide similar benefits to their workers prior to rising labor costs (Upendranadh Citation2013). In this situation, certification could contribute to a positive swing potential for issues such as the use of child labor, improved living conditions of temporary and permanent workers, encroachment of nearby Protected Areas and reduction of native shade trees – provided that audits are carried out with care and that criteria of standards are more stringent than the prevailing situation on-farm. However, in such adaptation sustainability standards have to ensure their complementarity to existing labor regulations and practices and not disincentive public actors (Neilson and Pritchard Citation2010a). The swing potential in terms of enhancing coffee quality is low due to past investments in coffee quality on both countries as well as the naturally high quality of Arabica coffee in India.

Mithöfer et al. (Citation2017) expected responses of the sustainability issue attention cycle to be triggered by problems thus curbing the downward swing potential. However, our analysis shows that responses are rather triggered by upgrading possibilities harnessing the upward swing potential. This can be seen by the progression to labeling to geographic origin in India, creating a biodiversity value proposition at landscape level and in Nicaragua creating the Small Producer Symbol with its value proposition for working with smallholders. Notably, Nicaraguan cooperatives with support of NGOs have also moved beyond certification at the farm level to interventions at community and landscape level.

8. Conclusion

Coffee producers in Nicaragua and India both face environmental, social and economic concerns at household as well as community and landscape level. The swing potential is bounded by past and current regulatory systems and development programs. In both countries, interventions have targeted the development of the coffee sector over time but with difference in focus. In Nicaragua interventions mostly focused on strengthening of the social and economic development of the sector via support to coffee cooperatives while in India smallholder coffee cooperatives are dysfunctional (Neilson and Pritchard Citation2007) and interventions focused on environmental goals such as forest and biodiversity conservation.

Both countries have moved on distinct certification trajectories. India now focuses on the environmental characteristics of its site, namely the high biodiversity value at landscape level which is translated into labeling of geographic origin. Hence, ‘certification of second generation’ moving beyond first experiences with UTZ and Rainforest Alliance. Nicaragua builds on its strength of the smallholder sector and social justice movements which is reflected in the development and uptake of the Small Producers Symbol. Both countries have moved beyond certification at the farm (group) level to the landscape shown by interventions of Nicaraguan coffee cooperatives at community and landscape level that complement certification schemes.

Sustainability standards and their adoption as well as their potential impacts have to be analyzed within the context of the producer country. The question not only is ‘What is the impact of sustainability standards?’ but also ‘What can be their potential impact given local conditions?’ Limited impact of sustainability standards may not only be due to limited time lag between implementation of the standard and impact assessment (Jena and Grote Citation2017) but simply due to the fact that local conditions were at or above the norms stipulated by the standard sometimes long before a sustainability standard arrived in a particular site.

Sustainability standards can provide a partial solution to local sustainability concerns but sometimes quite unintended so – as in the case in India – appearance of buyers for certified coffee triggered existing traders to match prices offered due to increased competition over prices. Public regulatory and development interventions provide the baseline and impulse on which well-aligned private-sector actors can build on to address social and environmental concerns. However, the diversity of production systems, ecosystems and sociological historical contexts strengthens the case for local, rather than global, sustainability standards. Local certification standards should take into account the existing management swing potential and design standards in order to make tangible improvements or concerted efforts to maintain the status quo (especially for rapidly downward sustainability trends). Sustainability standards have to be complementary to existing public regulatory and development interventions for credibility and avoidance of negative impact such as lowering the bar and being seen as enabling greenwashing. In dealing with global sustainability standards, local policies should ask for and monitor additionality of sustainability standards – what value do they add given local conditions?

With respect to the environmental dimension, research on the effect of forests, forest fragments and agroforestry systems and their connectivity (e.g. Raman Citation2006) clearly highlights the limitations of a plot level approach for certification. In order to attain higher levels in the provision of ecosystem services, sustainability standards should work with environmental projects for environmental conservation at landscape level. Therefore, coffee cultivated in strategic environmental hotspots, such as buffer zones around forest fragments, corridors linking forest fragments, riverbanks and steep slopes, should be given extra attention via preferential payment for ecosystem services, hence an approach in relative opposition to the blanket approach of paying a similar premium to any coffee area responding to the certification scheme criteria.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In this paper, the swing potential is assessed based on the spread between minimum and maximum values of economic, social and environmental indicators as found in the literature for each site.

2. In India, biodiversity studies focus on forest loss, forest fragmentation and sacred groves (e.g. Garcia et al. Citation2010), the contribution of forest (Anand et al. Citation2008) and the conservation of biological resources (e.g. Raman and Mudappa Citation2003; Bhagwat et al. Citation2005b; Brown et al. Citation2006; Raman Citation2006; Dolia et al. Citation2008; Kapoor Citation2008; Anand et al. Citation2010; Prakash et al. Citation2012), provision of ecosystem services such as pollination (Boreux et al. Citation2013b) and fertile soil and leaf litter as inputs to coffee production (Ormsby Citation2013) as well as the contribution of coffee systems to biodiversity conservation (e.g. Bhagwat et al. Citation2005a; Dolia et al. Citation2008; Caudill et al. Citation2014; Wordley et al. Citation2015).

3. The price of Arabica coffee of India has been much higher than those coming from various origins due to the following reasons: (1) it is a relatively high altitude coffee (1100–1300 masl), (2) under shade, (3) of high quality and (4) of relatively low volume available for export (hence relatively rare) due to the decreasing production (linked to increasing damages and loss due to a trunk borer and hence replacement by Robusta resistant to this pest) and increasing domestic demand (it is foreseen that Indian domestic demand will be up to 50% of the national production over the next decade). Arabica coffee from Nicaragua has a lesser reputation and hence fetches a lower price than neighboring countries (particularly to Costa Rica and Guatemala) and international market due to lower altitude where a large part of Nicaragua coffee is produced and poor management of wet processing.

4. Sustainability standards are seen to compete at a ‘standards market’ between convergence and differentiation. The former is characterized by the increasing alignment of norms and practices while the latter captures the need of particular standards to maintain distinct attributes and value proposition (Reinecke et al. Citation2012).

5. ISEAL is an NGO umbrella organization for sustainability standards, whereby standards show commitment to a unified movement of sustainability standards for the benefits of people and the environment (ISEAL Citation2016).

6. The revision of the SAN standard to its current form also resulted in a revision of the shade criterion, which now is considered weaker than it used to be (Craves Citation2017).

7. CAFNET – Connecting, Enhancing and Sustaining Environmental Services and Market Values of Coffee Agroforestry in Central America, East Africa and India (2007–2011). The project aimed at documenting biodiversity, traditional agroforestry knowledge and dynamics of landscape change.

8. Commercial polyculture is characterized by 31%–40% shade cover and 6–20 species; rustic farms are characterized by 71–100% shade and more than 50 species of trees (Perfecto et al. Citation2005).

9. Out-turn is mostly used locally in India and is a term describing the ratio (or %) of green beans to cherries (fresh or dry) after final processing before export and/or roasting.

10. Many farmers do not want to engage into improving their coffee quality, particularly the harvesting and drying process as they feel that it is not economically rewarding.

References

- 4C Association. 2009. What we do; [accessed 2014 Oct 06]. http://www.4c-coffeeassociation.org.

- Alvarez G, von Hagen O. 2012. When do private standards work? Literature review series on the impact of private standards - Part IV. Geneva: International Trade Centre.

- Ambinakudige S. 2009. The global coffee crisis and indian farmers: the livelihood vulnerability of smallholders. Canadian J Dev Stu/Rev Canadienne D’études Du Développement. 28:553–566.

- Ambinakudige S, Choi J. 2009. Global coffee market influence on land-use and land-cover change in the Western Ghats of Insia. Land Degrad Dev. 20:327–335.

- Ambinakudige S, Sathish B. 2009. Comparing tree diversity and composition in coffee farms and sacred forests in the Western Ghats of India. Biodivers Conserv. 18:987–1000.

- Anand MO, Krishnaswamy J, Das A. 2008. Proximity of forests drives bird conservation value of coffee plantations: implications for certification. Ecol Appl. 18:1754–1763.

- Anand MO, Krishnaswamy J, Kumar A, Bali A. 2010. Sustaining biodiversity conservation in human-modified landscapes in the Western Ghats: remnant forests matter. Biol Conserv. 143:2363–2374.

- Baca M, Läderach P, Haggar J, Schroth G, Ovalle O, Bond-Lamberty B. 2014. An integrated framework for assessing vulnerability to climate change and developing adaptation strategies for coffee growing families in Mesoamerica. PLoS ONE. 9:e88463.

- Baca M, Liebig T, Caswell M, Castro-Tanzi S, Méndez VE, Läderach P, Aguirre Y 2013. Revisiting the thin months in coffee communities of Guatemala, Mexico and Nicaragua. Final Research Report. Calí & Vermont: CIAT & Agroecology and Rural Livelihoods Group, University of Vermont.

- Bacon C. 2005. Confronting the coffee crisis: can fair trade, organic, and specialty coffees reduce small-scale farmer vulnerability in Northern Nicaragua? World Dev. 33:497–511.

- Bacon C, Méndez VE, Fox JA. 2008a. Cultivating sustainable coffee: persistent paradoxes. In: Bacon C, Méndez VE, Gliessman SR, Goodman D, Fox JA, editors. Confronting the coffee crisis: fairt Trade, sustainable livelihoods and ecosystems in Mexico and Central America. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press.

- Bacon CM. 2010. A spot of coffee in crisis. Lat Am Perspect. 37:50–71.

- Bacon CM. 2013. Quality revolutions, solidarity networks, and sustainability innovations: following Fair Trade coffee from Nicaragua to California. J Political Ecol. 20(5–10):98–115.

- Bacon CM, Méndez VE, Flores Gomez MA, Stuart D, Díaz Flores SR. 2008b. Are sustainable coffee certifications enough to secure farmer livelihoods? The millenium development goals and Nicaragua’s Fair Trade cooperatives. Globalizations. 5:259–274.

- Bacon CM, Sundstrom WA, Flores Gómez ME, Méndez VE, Santos R, Goldoftas B, Dougherty I. 2014. Explaining the ‘hungry farmer paradox’: smallholders and fair trade cooperatives navigate seasonality and change in Nicaragua’s corn and coffee markets. Global Env Change. 25:133–149.

- Bali A, Kumar A, Krishnaswamy J. 2007. The mammalian communities in coffee plantations around a protected area in the Western Ghats, India. Biol Conserv. 139:93–102.

- Beuchelt TD, Zeller M. 2011. Profits and poverty: certification’s troubled link for Nicaragua’s organic and fairtrade coffee producers. Ecol Econ. 70:1316–1324.

- Beuchelt TD, Zeller M. 2013. The role of cooperative business models for the success of smallholder coffee certification in Nicaragua: a comparison of conventional, organic and Organic-Fairtrade certified cooperatives. Renew Agric Food Syst. 28.

- Bhagwat S, Kushalappa CG, Williams PH, Brown N. 2005a. The role of informal protected areas in maintaining biodiversity in the Western Ghats of India. Conserv Biol. 10:8.

- Bhagwat SA, Kushalappa CG, Williams PH, Brown ND. 2005b. A landscape approach to biodiversity conservation of sacred groves in the Western Ghats of India. Conserv Biol. 19:1853–1862.

- Bhagwat SA, Willis KJ, Birks HJB, Whittaker RJ. 2008. Agroforestry: a refuge for tropical biodiversity? Trends Ecol Evol. 23:261–267.

- Bitzer V, Francken M, Glasbergen P. 2008. Intersectoral partnerships for a sustainable coffee chain: really addressing sustainability or just picking (coffee) cherries? Global Env Change. 18:271–284.

- Blackman A, Rivera J. 2011. Producer-level benefits of sustainability certification. Conserv Biol. 25:1176–1185.

- Bolwig S, Gibbon P, Jones S. 2009. The economics of smallholder organic contract farming in tropical Africa. World Dev. 37:1094–1104.

- Boreux V, Krishnan S, Cheppudira KG, Ghazoul J. 2013a. Impact of forest fragments on bee visits and fruit set in rain-fed and irrigated coffee agro-forests. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 172:42–48.

- Boreux V, Kushalappa CG, Vaast P, Ghazoul J. 2013b. Interactive effects among ecosystem services and management practices on crop production: pollination in coffee agroforestry systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 110(21):8387–8392.

- Bose A 2014. Ficus to filter: the political ecology of market-based incentives for conserving biodiversity. [PhD Thesis]. Cambridge (UK): University of Cambridge.

- Bose A, Vira B, Garcia C. 2016. Does environmental certification in coffee promote “business as usual”? A case study from the Western Ghats, India. Ambio. 45:946–955.

- Bray JG, Neilson J. 2017. Reviewing the impacts of coffee certification programmes on smallholder livelihoods. Int J Biodivers Sci Ecosyst Serv Manag. 13(1):216–232.

- Brown N, Bhagwat S, Watkinson S. 2006. Macrofungal diversity in fragmented and disturbed forests of the Western Ghats of India. J Appl Ecol. 43:11–17.

- Bruce A. 2016. The legacy of agrarian reform in Latin America: foundations of the fair trade cooperative system. Geogr Compass. 10:485–498.

- Bunn C, Läderach P, Ovalle Rivera O, Kirschke D. 2015. A bitter cup: climate change profile of global production of Arabica and Robusta coffee. Clim Change. 129:89–101.

- CAFENICA. 2016. CAFENICA: about; [accessed 2016 May 08]. http://cafenica.net/en/about.

- CAFNET. 2011. Final report - India. Bangalore (India): Regional Centre, Coffee Agroforestry Network - Connecting, Enhancing and Sustaining Environmental Services and Market Values of Coffee Agroforestry in Central America, East Africa and India.

- Caswell M, Méndez VE, Baca M, Läderach P, Liebig T, Castro-Tanzi S, Fernández M. 2014. Revisiting the “thin months”- a follow-up study on livelihoods of Mesoamerican coffee farmers. Cali (Colombia): Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT).

- Caudill A, Vaast P, Husband T. 2014. Assessment of small mammal diversity in coffee agroforestry in the Western Ghats, India. Agrofor Syst. 88:173–186.

- CBD. 2017. List of parties; [accessed 2017 July 25]. https://www.cbd.int/information/parties.shtml

- CBI. 2016. Database on coffee. Coffee Board of India; [accessed 2016 May 24]. http://www.indiacoffee.org/database-coffee.html.

- CBI. 2017. Indian coffee exporters; [accessed 2017 Oct 22]. http://www.indiacoffee.org/Indian%20Coffee/Indian%20Coffee%20Exporters[1]_2.pdf.

- CEI. undated. Export directory; [accessed 2016 Mar 01]. http://www.cei.org.ni/exporters.php?empresa=Company&dpto=+&producto=coffee&sac=HS+Code&lvl=102&lvl2=103&form_exportadores_buscar=Search.

- Central Ground Water Board. 2007. Ground water information booklet, Kodagu District, Karnataka. Bangalore: Central Ground Water Board, Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India.

- CEPALSTAT. 2014. Nicaragua: pérfil nacional económico; [accessed 2014 Mar 01]. http://interwp.cepal.org/cepalstat/WEB_cepalstat/Perfil_nacional_economico.asp?Pais=NIC&idioma=e.

- Chandran MS. 1997. On the ecological history of the Western Ghats. Curr Sci. 73:146–155.

- Chaudhary A, Kastner T. 2016. Land use biodiversity impacts embodied in international food trade. Global Env Change. 38:195–204.

- Chemonics International. (2006). Central American and Dominican Republic Quality Coffee Program (CADR QCP). Final Report. USAID. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pdacj043.pdf.

- Chengappa PG, Rich K, Muniyappa A, Yadava CG, Pradeepa B, Rich M. 2014. Promoting conservation in India by greening coffee. Oslo (Norway): Norwegian Institute of International Affairs.

- Chethana A, Nagaraj N, Chengappa P, Gracy C. 2010. Geographical indications for Kodagu Coffee - a socio-economic feasibility analysis. Agric Econ Res Rev. 23:97–103.

- Craves J 2017. The new rainforest Alliance shade requirements. Coffee & Certification; [accessed 2017 Oct 22]. http://www.coffeehabitat.com/2017/02/new-rainforest-alliance-shade-requirements/.

- Damodaran A. 2002. Conflict of trade-facilitating environmental regulations with biodiversity concerns: the case of coffee-farming units in India. World Dev. 30:1123–1135.

- Daviron B, Vagneron I. 2011. From commoditisation to de-commoditisation … and back again: discussing the role of sustainability standards for agricultural products. Dev Policy Rev. 29:91–113.

- Davis SC, Boddey RM, Alves BJR, Cowie AL, George BH, Ogle SM, Van Wijk MT. 2013. Management swing potential for bioenergy crops. GCB Bioenergy. 5:623–638.

- de Janvry A, McIntosh C, Sadoulet E. 2015. Fair trade and free entry: can a disequilibrium market serve as a development tool? Rev Econ Stat. 97:567–573.

- Depommier D. 2003. The tree behind the forest: ecological and economic importance of traditional agroforestry systems and multiple uses of trees in India. Int Soc Trop Ecol. 44:63–71.