ABSTRACT

In this study, I analyse whether and why people’s social trust, the belief that most people can be trusted, changed during the COVID-19 pandemic in Switzerland. My analysis is guided by two different approaches to potential dynamics in social trust, (1) the settled disposition model which advocates for stability within individuals over time, and (2) the active updating model claiming that crisis-induced experiences may leave a lasting scar on people’s trust. Using nationally representative longitudinal data from the Swiss Household Panel and comparing patterns of change before, during and after the outbreak of the pandemic, I found that an exceptionally large share of respondents displayed a decline in social trust in spring 2020. However, in most cases, trust quickly recovered to pre-crisis levels shortly afterwards, thus strengthening the hypothesis that people’s social trust tends to fluctuate around a certain set point. Among a range of potential individual-level determinants for the short-lived drop in social trust, only attitudes towards the government’s handling of the crisis stick out as significant drivers of change.

1. Introduction and background

Social trust, the belief that most other people can be trusted (Stolle, Citation2002), has a wide range of documented benefits. On the individual level, people with high levels of social trust have longer life expectancy (Giordano et al., Citation2019) and report higher rates of subjective well-being (Helliwell et al., Citation2018; Helliwell & Wang, Citation2010). On a societal level, high levels of social trust are likely to improve economic development (Fukuyama, Citation1995) and democratic functioning (Warren, Citation2018). Moreover, in dire times, when the need for cooperation is strong, social trust facilitates efficient collective action (Ostrom & Ahn, Citation2009).

Recently, researchers have begun to explore how social trust responds to large-scale external shocks such as earthquakes (Yamamura et al., Citation2015), epidemics (Aassve et al., Citation2021) economic crises and war (Kijewski & Freitag, Citation2018). On the individual level, negative events like victimisation (Salmi et al., Citation2007), unemployment (Delhey & Newton, Citation2003) and divorce (Brinig, Citation2011) negatively affect social trust. Although different in scale and impact, the above-mentioned studies suggest that crises, no matter whether they are personal or collective, may influence people’s social trust.

Few studies have examined how social trust changed during the recent COVID-19 pandemic (Delhey et al., Citation2023; Esaiasson et al., Citation2021; Kye & Hwang, Citation2020; Thoresen et al., Citation2021; Umer, Citation2023; van der Cruijsen et al., Citation2022; Zangger, Citation2023). Moreover, the few existing longitudinal studies that explore change in social trust during the pandemic tend to rely on two-wave panel data (Esaiasson et al., Citation2021; Kye & Hwang, Citation2020). Previous evidence (Dawson, Citation2019) argues that even though individual-level social trust can change, it tends to revert to the initial long-term level. Two-wave panel data may thus be severely lacking as this variation can only capture the initial reaction but fails to see any eventual reversion. This study, by contrast, draws on three-wave panel data from Switzerland, focusing on the timeframe 2019–2021. In doing so, this study compares repeated measures from the same individuals before the pandemic, after the first wave of the pandemic and one year after the first outbreak.

Theoretically, I draw on two opposing strands of research regarding social trust’s potential to change over people’s life course, namely the settled dispositions model – advocating for stability in trust within individuals over time (Lizardo, Citation2017; Uslaner, Citation2002) and – the active updating model, which assumes that crisis-induced experiences may leave a lasting scar on people’s trust (Dinesen & Bekkers, Citation2017; Glanville & Paxton, Citation2007; Lersch, Citation2023).

Analytically, I have three main goals: (1) to investigate the malleability of social trust during the pandemic, (2) to evaluate the applicability of the mentioned theoretical frameworks and (3) to discern whether changes in trust happened amongst the general public or whether some groups were more likely to display change in social trust than others.

2. Theoretical discussion, previous research and hypotheses

Social trust is a thin form of generalised interpersonal trust shared between the general public (Uslaner, Citation2002). Social trust comes with a range of normatively desirable benefits such as financial efficiency and economic growth (Bjørnskov, Citation2012; Fukuyama, Citation1995), faith in democracy (Newton, Citation2001; Warren, Citation2018) and is an important part of social capital (Rothstein & Stolle, Citation2008). Social trust differs from the institutional and political trust, which refers to the type of trust that people have in the institutional pillars of society, such as law enforcement and health care (Dinesen, Citation2013; Rothstein & Stolle, Citation2008) or political actors, parties and policy-makers (Listhaug & Jakobsen, Citation2018). Importantly, research has shown that the institutional and political trust can influence social trust (Dinesen et al., Citation2022; Mattes & Moreno, Citation2018) and vice versa, albeit evidence for reverse causality is much more limited (Sønderskov & Dinesen, Citation2016).

There are two competing views regarding the malleability of social trust. The settled disposition model holds that social trust is predominantly shaped during childhood and adolescence (Uslaner, Citation2002, Citation2018). Trust is thus seen as the product of the social context of one’s upbringing with parental figures and/or main caregivers acting as prime influencers (Lizardo, Citation2017). Moreover, perceived inequality and institutional unfairness during one’s upbringing may leave lasting influences on people’s trust in other people even if the same issues are absent later in life (Fairbrother & Martin, Citation2013; Rothstein, Citation2011). In sum, the settled dispositions model asserts that people develop a certain level of social trust at a relatively young age only to crystalise upon reaching adulthood (Uslaner, Citation2002).

This notwithstanding, even proponents of the settled disposition model, e.g. Uslaner (Citation2010, Citation2014) argue that major collective experiences, such as the 2008 worldwide economic crisis (Uslaner, Citation2010), can affect people’s social trust even among adults. However, while significant collective events may bring about changes in people’s trust levels, the more important question is whether those changes are temporary or more permanent. Highlighting the possibility for attitudinal short-term changes while simultaneously advocating for long-term stability, this theoretical perspective is encapsulated by the ‘set-point’ theory (Anusic et al., Citation2014; Kuhn, Citation1962; Lucas, Citation2007). In short, the set-point approach proposes that people develop baseline values and attitude levels during the earlier stages of the lifecycle around which they fluctuate, primarily due to certain life events during adulthood (Lucas, Citation2007). While originally developed by researchers in the field of subjective well-being (Helliwell et al., Citation2018; Hudson, Citation2006), set point theory remains largely unexplored in a social trust setting. An important exception is a recent study by Dawson (Citation2019) that despite not explicitly theorising findings from a set-point perspective, identified patterns in line with the theoretical framework of the set-point theory while exploring the persistence of social trust with British panel data. Importantly, the author observes that social trust – despite fluctuating in a short-term perspective – tends to be largely stable in a long-term perspective.

The active-updating model is, in contrast, anchored in the idea that experiences continuously shape adult people’s social trust (Glanville & Paxton, Citation2007) throughout their entire life course (Dinesen & Bekkers, Citation2017; Lersch, Citation2023). Exploring the relationship between trust, migration and ethnic diversity, Dinesen et al. (Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2017, Citation2020) provide possibly the most conclusive evidence for the active-updating model in regard to social trust. Using the ‘natural’ experiment of migration, Dinesen et al. (Citation2020) show, for example, that immigrants’ trust levels more frequently converge with their host societies’ average trust levels than previously assumed and that this ‘trust assimilation’ is even more pronounced among second- and third-generation immigrants.

Similarly, a multitude of individual-level experiences determine social trust including involvement in civic life (Delhey & Newton, Citation2003; Dinesen & Bekkers, Citation2017), unemployment (Laurence, Citation2015; Mewes et al., Citation2021), self-rated health (Giordano & Lindström, Citation2016; Mewes & Giordano, Citation2017; Subramanian et al., Citation2002), subjective well-being (Glatz & Schwerdtfeger, Citation2022; Helliwell et al., Citation2018), relationship status (Herreros, Citation2015; Power, Citation2020) and education (Huang et al., Citation2011).

Much less is known about whether and how collective experiences, such as collective crisis experiences (see Aassve et al., Citation2021; Kijewski & Freitag, Citation2018; Yamamura et al., Citation2015) affect social trust. Studying the economic crisis in Greece between 2002 and 2011 with cross-sectional data, Ervasti et al. (Citation2019) find that social trust remained largely undeterred, even increasing at times, a trend that the authors attribute to increased solitary and collective resentment of the Greek government’s poor management. Theoretically, this result supports both the settled dispositions model (stable) and the active-updating model (increased), however, relying only on cross-sectional data, the study is unable to determine if the observed increase in trust was a temporary short-lived reaction or a more lasting phenomenon (fluctuation).

Previous research studying the effects of the COVID-19 crisis also emphasises the need for proper crisis management. For instance, studying trends in social trust in Sweden between February and April 2020, Esaiasson et al. (Citation2021) observed a slight increase in social trust in their two-wave panel data, a trend that the authors attribute to a ‘rally around the flag’ effect caused by governmental efforts to deal with the pandemic, resulting in an increased sense of unity and collective action, which, in turn, spurred growing social trust (Baker & Oneal, Citation2001). Drawing on cross-sectional data from South Korea between March and April 2020, Kye and Hwang (Citation2020) point to a similar ‘rally around the flag’ effect triggering an increase in social trust during the early stages of the pandemic.

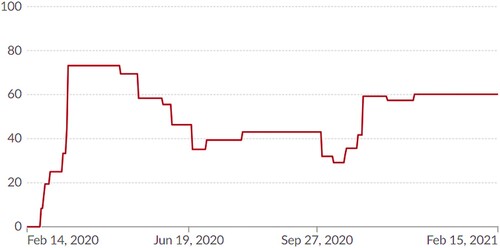

While the results from the studies in Sweden and South Korea attribute increases in social trust during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic to ‘rally around the flag’ effects, the data used by those studies were collected during periods in which the respective governments introduced restrictions that were designed to reduce the spread of the disease and to save a maximum of human lives. The first data coinciding with the pandemic from my study comes, by contrast, from a slightly later period (20th of May until 20th of June 2020) during which the Swiss government began to reduce restrictions and limitations put in place to safeguard the population (see ).

Figure 1. Government stringency index: the case of Switzerland. Note: The Stringency index is a composed measure based on nine response indicators including school closures, workplace closures and travel bans, rescaled to a value range 0–100 (100 = strictest) | Source: Hale et al., (Citation2021).

Another particularly relevant factor to consider when studying social trust during the COVID-19 crisis is pandemic-related subjective worries pertaining to personal health or the health of people’s close friends and family members. For example, previous research by Thoresen et al. (Citation2021) and Delhey et al. (Citation2023) shows that health-related worries in conjunction with perceived elevated health risks coincided with lower levels of social trust during the pandemic. While Thoresen et al. (Citation2021) draw on 2019–2020 cross-sectional data from Norway, Delhey et al. (Citation2023) use 2020–2022 panel data from Germany.

Both studies emphasise that individual-level pandemic-related worries significantly determine social trust in their respective contexts. Both attribute the relationship between trust and worries in part to the seriousness of the situation and the legitimacy of health-related worries during the earlier days of the pandemic. Given those worries, one could argue that even those who were confident in their ability to ‘handle’ the virus themselves might have worried about friends and family members.

All in all, previous research into social trust during the pandemic emphasises macro-level determinants (institutions and political actors) as well as individual- and/or family-level experiences effects. To reiterate, theoretically, the prime difference between the two main perspectives on social trust, i.e. the settled dispositions model – in this case, supplemented by the set-point theory – and the contrasting active-updating model is their take on the malleability of trust. Is social trust durable and resistant to long-term change, or do crisis-induced changes leave a lasting imprint on people’s trust? Here, I propose two hypotheses, each one corresponding to a perspective that favours either experience-driven change or culturally-driven durability.

H1: People’s social trust remained stable throughout the observed timeframe.

H2: People’s social trust changed from the first to the second wave and remained constant in the third wave.

H3: People’s social trust changed from the first to the second wave but returned to pre-crisis levels in the third wave.

3. The Swiss context

The influence and consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic varied greatly across the globe. In this study, I rely on repeated measures from Switzerland. In the following section, I briefly review the Swiss timeline regarding the first year of the pandemic and the government interventions following the first outbreak of COVID-19 in Switzerland.

The first case of COVID-19 in Switzerland was registered on the 25th of February in 2020 (New Coronavirus, Citation2019-nCoV: First Confirmed Case in Switzerland, n.d.). The Swiss government quickly implemented certain restrictions, e.g. restricting access to larger public events, providing financial support for vulnerable social groups and educating the public about necessary behaviour practices such as social distancing (Giachino et al., Citation2020). Throughout the following months, the restrictions were upscaled to include travel limitations, school closings and public transport restrictions while encouraging working from home and limiting gatherings to increasingly smaller numbers (Anania et al., Citation2022).

The Swiss government’s attempt to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and protect the population is illustrated (see ) with a stringency index generated from the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) developed by Hale et al. (Citation2021).

4. Data and measurements

Empirically, I used nationally representative longitudinal data from the Swiss Household Panel (SHP). As a unique longitudinal database that follows the same individuals over long periods. The SHP consists of four sample groups, each sample representing an influx of new households into the SHP survey, a feature that allows researchers to distinguish period from cohort effects. The SHP covers all household members from the year they turn 14 years (Tillmann et al., Citation2022). Data collection began in 1999 with the first sample reaching 5074 households containing 12,931 individuals. However, social trust was not surveyed until 2002, but then on an annual basis ever since. The second sample, added in 2004, reached 2538 households containing 6569 individuals. The third sample from 2013 reached 4093 households containing 9945 individuals. Lastly, the fourth and most recent sample from 2020 consists of data from 4380 households containing 7557 individuals (Tillmann et al., Citation2022). Individual-level response rates have remained high in all four samples with 85, 76, 81 and 74 per cent, respectively for each sample group (Tillmann et al., Citation2022).

Between the 20th of May and the 20th of June 2020, the SHP conducted an extra survey that contained 47 questions focused on the on-going COVID-19 pandemic among a selection of their original sample groups. Contrary to previous and subsequent waves, the extra COVID-19 wave contains a range of unique items concerning the respondents’ perception of how the government handled the crisis and how the respondents and their significant others were affected by the pandemic and the restrictions. Yet other standard socio-demographic characteristics were not measured in the special pandemic issue, something that bears important limitations for my research design as I will develop below.

4.1. Dependent variable

Social trust is operationalised by the standard single-item measure (Uslaner, Citation2015): In general, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful these days? The question is measured using a 0–10 scale, with higher values indicating higher levels of trust. The mean value was 6.3 (SD = 2.2) in both of the regular 2019 and 2020 waves, putting Switzerland, among the group of high-trust countries (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, Citation2016; Sønderskov & Dinesen, Citation2014). However, in the extra COVID-19 survey, the trust mean dropped to 5.8 (SD = 2.5).

4.2. Independent variables

To examine whether social trust changes were more pronounced among specific groups of people or whether the change could be observed in the general population, I opted to include a range of determinants that, based on previous findings, hold the potential to determine changes in social trust.

During the first year of the pandemic, the adverse health consequences of a COVID-19 infection were more impactful than a year later when vaccination became readily accessible in most countries (Kontis et al., Citation2020). It was during this very period that a COVID-19 infection was most lethal, especially for individuals with underlying health and physical complications (Díaz Ramírez et al., Citation2022; Kiang et al., Citation2020). Old age was quickly pinpointed as a particularly strong risk factor due to the, on average, increased number of underlying complications and vulnerabilities. Aside from being an important risk factor to consider during this particular crisis, young age is generally viewed as a more malleable phase of our lives (Dinesen, Citation2012; Uslaner, Citation2002) where trust is particularly susceptible to change. Thus, an important determinant to consider is the participant’s age. Age was re-coded into five different age groups: 14–25, 26–35, 36–55, 56–75 and 76 plus.

Because of the salience of subjective physical and mental health during the pandemic, the analysis will include information about the respondent’s self-rated health. Self-rated health is, crudely but in line with previous studies (Ahmad et al., Citation2014; Cullati, Citation2014; Węziak-Białowolska, Citation2016), operationalised by the question: How do you feel right now? The response options range from a 1 ‘very well’ to 5 ‘not well at all’. I re-coded the variable so that higher values indicate better self-assessed health.

Subjective well-being (SWB) determines social trust (Helliwell et al., Citation2018; Hudson, Citation2006), whereas evidence for reverse causality is far more limited (Glatz & Schwerdtfeger, Citation2022). Thus, three items measuring elements of subjective well-being (SWB) are included in the analysis. These items include general life satisfaction, sense of belonging and satisfaction with leisure activities. Life satisfaction is measured with the following question: In general, how satisfied are you with your life? The response options range from 0 to 10, with higher values indicating greater satisfaction. Sense of belonging was measured using a reversed scale of loneliness, in turn, measured with the following question: How alone do you feel in your life? With response options ranging from 0 to 10, with higher values indicating higher degrees of loneliness. The scale was reversed to make lower values indicate higher degrees of loneliness. Satisfaction with leisure activities is measured with the following question: How satisfied are you with your leisure time activities? Response options range from 0 to 10, with higher values indicating greater satisfaction.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, and especially during the earlier stages, national governments often implemented restrictions such as travel restrictions and lockdowns to keep the population safe. Although those restrictions were attempts to halt the spread of the disease, the necessity of the restrictions was increasingly questioned as the pandemic progressed (Selby et al., Citation2020; Zimmermann et al., Citation2022). Restrictions perception is operationalised by the question: How do you perceive the restrictions of civil rights imposed by the Federal government (freedom of movement and of assembly)? The response options range includes 1 representing ‘unproblematic, necessary and justified’, 2 ‘problematic but necessary and justified’ and 3 ‘neither necessary nor justified’.

In a similar vein, the participant’s perception of the government’s ability to handle the crisis is a crucial factor to consider. Government crisis perception is measured by the question: To what extent do you agree with the following statement – the Federal Council has handled the crisis well. The response options range from 0 to 4, with higher values indicating greater agreement.

Another consequence of enforced restrictions and recurring lockdowns was an increase in unemployment (Kawohl & Nordt, Citation2020), a trend that was primarily due to severe strain on the financial sector, especially for smaller companies and start-ups (Padhan & Prabheesh, Citation2021). Thus, I include information regarding the participant’s employment status in the analysis. Specifically, I distinguish between employed, unemployed and economically inactive at the time of the interview.

Based on the previously discussed findings from Norway (Thoresen et al., Citation2021) and Germany (Delhey et al., Citation2023), feeling worried about both one’s health and that of significant others is included as a potentially important determinant of social trust. Hence, worries related to respondent’s current lifestyles and their social relations are included in the analysis. Worry for one’s lifestyle was measured with the following question: How concerned are you about the following – worry about your lifestyle? Worry for one’s social relations was measured with the following question: How concerned are you about the following – worry about your social relations? Worry for one’s health and the health of one’s close ones was measured with the following questions: How concerned are you about the following – worry about your health? and How concerned are you about the following – the health of close ones? The four questions were measured on a 0–10 scale, with higher values indicating higher levels of worry.

Lastly, the analysis includes socio-demographic controls that were highlighted in previous studies about determinants of social trust, e.g. biological sex (Mewes, Citation2014), partner status (Glanville et al., Citation2013; Herreros, Citation2015) and the presence of children in the household (i.e. either their own or otherwise) (Brinig, Citation2011). That said, even though evidence for an association between partner status and trust is very limited (Kumove, Citation2023), few studies explore the relationship between trust and partnerships during crises. Given that the circumstances of the pandemic may alter the importance of one’s relationships, I opt to include it in the analysis. Recent research suggests that mothers in a relationship are especially vulnerable as they often carry the bulk of the domestic work and take greater responsibility for the homeschooling of their children (O’Reilly, Citation2020; Power, Citation2020). Since education and income were not surveyed in the added COVID-19 survey, these two potentially important determinants of trust could unfortunately not be included in the analysis .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (Ntotal = 5843).

5. Method

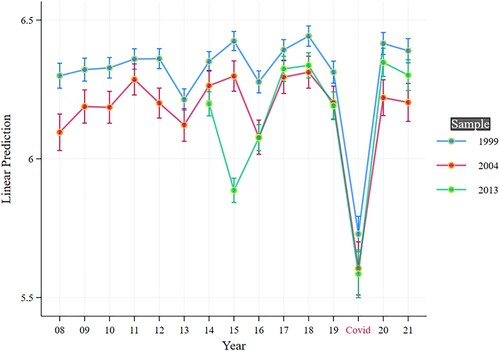

The empirical analysis is divided into three different steps. First, I used fixed-effects (FE) regression analysis to study the extent to which social trust within-individual variation in trust was subject to period effects during the 2008–2021 period, showing an exceptional albeit short-lived, drop during the pandemic.

Second, continuing to focus on the three waves constituting the focal point of my analysis, I use a first-difference estimator (Brüderl & Ludwig, Citation2015) to uncover whether social trust decreased among the general population or specific subgroups. The exact interval of these three crucial waves is September until March of 2019/2020 (‘t1’), 20th of May until 20th of June 2020 (‘t2’) and late August until early March of 2020/2021 (‘t3’). While being very similar to fixed-effects regression, the first differences estimator is superior when it comes to measuring changes between two distinct time points (Brüderl & Ludwig, Citation2015, pp. 327–357). Specifically, I applied first differencing models to examine within-individual change among the participants during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, a period that both saw decreasing (t1 → t2) and increasing (t2 → t3) levels of trust within a relatively short time frame.

Third and finally, I present findings from a multinominal logistic regression analysis (Draper & Smith, Citation1998; Gelman & Hill, Citation2006) designed to identify whether the observed changes in social trust occurred among the general population or whether certain social groups were over- or underrepresented among those that experienced change equal to or greater than 1 standard deviation of trust during the extra COVID-19 survey. Importantly, this analytical step makes use of the pandemic-related items that were only included in the COVID-19 extra panel wave. However, this decision comes at the cost of making it impossible to rely on within-individual variation regarding the left-hand side of the equation. Instead, this analysis exploits within-variation regarding the dependent variable, asking whether pandemic-specific worries and attitudes toward the handling of the pandemic are associated with changes (of at least one SD) in social trust. All data preparation and analyses were conducted using STATA-16.1 SE (StataCorp, Citation2019).

6. Results

The results will follow the outline discussed in the methods segment starting with an overview of trends in social trust in Switzerland between 2008 and 2021, followed by the first difference analysis and finally the multivariate analysis .

Figure 2. Fixed-effects regression: trust development from 2008 until 2021 with 95% confidence intervals. Note: The results from the extra COVID-19 survey is highlighted. A numerical table of the results can be found in the appendix of the article. The fourth sample, added in 2020, is not included here.

6.1. Social trust trends in Switzerland

Departing from a long-term perspective (2008–2021) and analysing trends in trust from a longitudinal perspective with fixed-effects regression, I find that trust remained, by and large, stable. There is, however, one notable exception during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, where the average rate of trust fell from the 6.2 to 6.4 mark to roughly 5.6 (see ). This cautiously supports the view that crises can undermine people’s trust, with an important question being whether trust levels fell among the general public or whether decreases in trust were more pronounced in specific social groups. While trust levels decreased rapidly early in the pandemic they increased just as quickly in the wave following the extra COVID-19 wave that was fielded during spring/summer 2020.

6.2. First difference regression analysis

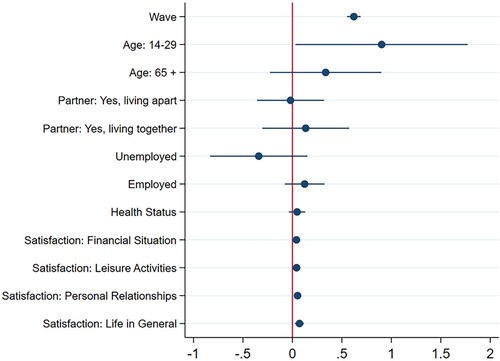

Beginning with the first difference regression analysis that examined the drop in social trust that occurred between t1 → t2 (see ), the results indicate that neither age, financial situation, relationship – employment and/or health status determined trust during the period between autumn 2019 and late spring 2020. However, respondent satisfaction with their personal relationships, leisure activities and general life are all statistically significant and positive, indicating that people displaying high levels of satisfaction were less likely to be part of the collective drop in trust that characterised the Swiss sample between t1 → t2.

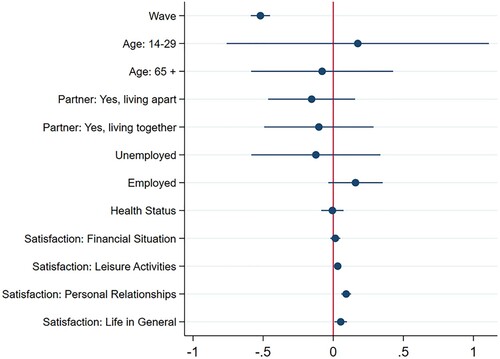

Figure 4. First difference regression: within-individual factors of change in trust between t2 and t3. Note: Change beetween the extra COVID-19 wave and the annual 2020 wave, i.e. the ‘increase’ in social trust. A numerical table of the results can be found in the appendix.

Analysing within-individual factors that contributed to the subsequent rise in trust observed between t2 → t3 (e.g. late spring 2020 to autumn 2020) in Switzerland, I found that most predictors included in the regression were statistically insignificant (see ). One important observation, though, is that people between the ages of 14–29 had a higher recovery rate of trust when compared with other age groups. Importantly, people who reported higher levels of satisfaction with their personal relationships, leisure activities and life in general were more likely to display recovered trust levels.

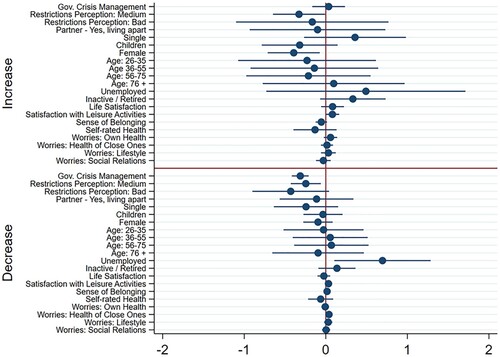

Figure 5. Multinominal logistic regression: confidence intervals of 95% (Nvalid = 4049). Note: Reference for the restriction variable=‘people who don’t think the restrictions are problematic at all and necessary’ | Reference for the partner variables= ‘people who share a household with their partner’ | Reference for the female variable= ‘male’ | reference for the age groups= ‘14–25’ | Reference for the employment status variable= ‘employed’ | Log likelihood −2330.7528 (iteration 4) | Prob chi2 0.00000 | Lr chi2(42) 11.98 | Pseudo R2 0.0235 | A numerical presentation of the multinominal logistic regression is included in the appendix.

6.3. Multivariate analysis

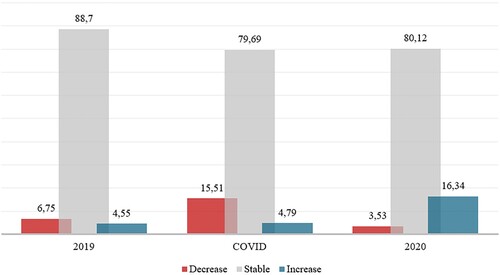

Was there a general decrease in trust between 2019 and the added COVID-19 survey, or was it more pronounced among certain groups? To test this assumption from a multivariate perspective, a new dependent variable with three different categories was created: (1) No change in trust of at least 1 SD between t1 and t2, (2) a decrease in trust of at least 1 SD between t1 and t2 and (3) increase in trust of at least 1 SD between t1 and t2.

Incidentally, about 80 per cent of the participants experienced no change of at least 1 SD between t1 and t2. In comparison, 15 per cent of the participants experienced a decrease and 5 per cent experienced an increase during the same period. While the ‘stable’ group includes most respondents, the total share of respondents reporting a change (increase or decrease) in social trust is substantially larger in the COVID-19 survey than in previous waves of the SHP (normally around the 4∼5 per cent mark). To understand whether the unique change in trust was group-specific or collective, I here identify participants whose trust level at t2 differs at least one standard deviation from that at t1. As already mentioned, I must refrain from within-design because of the bulk of theoretically important measures that were only included in the COVID-19 extra wave of the SHP.

Using the bulk of respondents who report stable trust levels at both t1 and t2 as a reference group against which two different groups (increase and, respectively, decrease in trust between t1 → t2) are analysed, my cross-sectional multinominal logistic regression represents a first step to understand whether certain social groups were overrepresented among those that displayed a negative trend in trust during the pandemic. This form of regression analysis is designed to calculate predicted probabilities and relative risk ratios of a categorical, dependent variable. In this case, the stable group represents most of the participants and serves as a baseline reference for the two other groups, essentially comparing what could have caused each group to either increase or decrease their social trust.

Given that the confidence intervals of most regression coefficients cross unity (Gelman & Hill, Citation2006), the majority of the included independent variables were not statistically significant (Smithson, Citation2003). As for increases in trust, only biological sex sticks out from the list of otherwise trivial determinants. However, explaining the significance of biological sex without more data is notoriously challenging, especially since previous findings suggest that women, mothers specifically, struggled during the pandemic due to heightened informal workload and care responsibilities (Power, Citation2020). One could speculate that the work-from-home policy alongside recurring lockdowns forced both parties to increase their presence at home, ideally resulting in increased shared responsibility. The confidence intervals of unemployment were wide indicating that the results are statistically unstable (Smithson, Citation2003). Specifically, having wide confidence intervals simply means that if I were to draw an infinite number of samples, the range in which these samples would ‘fall’ is wider, thus making results with wider confidence intervals more varied and less statistically accurate.

Similarly, most variables were insignificant amongst the participants who experienced a decrease in social trust, with three important exceptions. The items evaluating governmental crisis management as well as the participants’ attitude towards the restrictions of civil rights proved significant, highlighting the relationship between social trust and governmental action while hinting at the importance of believing and/or trusting that said governmental actions are important to adhere to deal with the on-going crisis. The last significant item was unemployment status, specifically for participants belonging to the decreased social trust group.

7. Discussion and concluding remarks

In this study, I have explored the evolution of social trust in Switzerland throughout the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. To reiterate, the aim of the study was to map patterns and individual-level dynamics of social trust during the COVID-19 pandemic and assess the applicability of two theoretical frameworks regarding stability vs. change in social trust: the settled dispositions model (H1) vs. the active-updating model (H2).

My analysis of repeated measures from the Swiss Household Panel shows that an unusually large share of the respondents experienced a decline in social trust between autumn 2019 and the summer of 2020. However, an at least equally large share of the respondents reported an increase in trust during autumn 2020, thus strengthening recent findings which suggest that social trust has, despite any short-term fluctuations (Dawson, Citation2019), a tendency to revert to a fixed individual ‘set point’ (H3). While my findings, by and large, favour the settled dispositions model (H1), it cannot explain why so many people experienced a short-lived decrease in trust in the initial phase of the pandemic. Given how quickly respondents’ trust levels recovered to pre-crisis levels, too much emphasis on the active updating model does not seem to be warranted either. Here, the set-point theory (H3), originally brought forward to describe how personal values and attitudes tend to fluctuate around a relatively stable ‘set point’ emerges as a theoretically fruitful extension to the settled-dispositions model of personal value change (Kumove, Citation2023).

All in all, my analysis shows how collective experiences, such as the recent COVID-19 pandemic, can lead to short-lived changes in social trust. However, within a very short period of just a few months, people’s trust quickly recovered back to pre-crisis levels. Future studies should thus be cautious when rejecting the settled dispositions approach, or the cultural perspective, all too quickly.

In line with previous findings regarding the relationship between social trust and subjective well-being (SWB) (Glatz & Schwerdtfeger, Citation2022; Helliwell et al., Citation2018), here measured with three satisfaction determinants, i.e. satisfaction with personal relationships, leisure activities and general life, I find that SWB positively determined social trust throughout the three waves present in my first difference analysis. Specifically, during the ‘fall’ (i.e. autumn 2019 to late spring 2020) respondents with higher rates of SWB were more resistant to the collective decrease of trust. Moreover, during the ‘rise’ of trust (i.e. spring 2020 to autumn 2020), SWB positively influenced social trust signalling that participants with higher rates could regain what they had previously lost much quicker. In addition to SWB, only young age stands out as an important determinant of social trust, though only during the latter ‘rise’ period, warranting cautious support for the notion that younger people, specifically adolescents and young adults, are more malleable than previously believed.

The multinomial logistic regression, in contrast, utilised determinants that could only be found in the extra COVID-19 survey. Here the pandemic-specific items government crisis management and restrictions perception stick out as important determinants for decreased rates of trust. Unemployment was also identified as an important determinant for decreased rates of trust. In contrast to previous findings by Thoresen et al. (Citation2021) and Delhey et al. (Citation2023), I do not find any evidence that health-related worries played a significant role in shaping people's trust during the pandemic. While previous findings highlight the positive spillover effect linked to increased governmental trust in the spring 2020 (see Esaiasson et al., Citation2021; Kye & Hwang, Citation2020), I find evidence that disagreement with the government actions negatively influenced social trust in the short term. Most importantly, I find that most people experienced a substantial loss followed by a quick rebound in social trust during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

7.1. Limitations

Analysing the applicability of the general trust question in the context of the pandemic, Wollebæk et al. (Citation2021) suggest that the intensified risk of infection during the pandemic caused the standard single-item measure of social trust to be interpreted somewhat differently (In general, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful these days?). The wording you can’t be too careful these days was particularly problematic due to its association with taking steps to avoid infection and complying with active guidelines, making the standard single-item measurement an unfortunate choice to assess social trust during the pandemic (Wollebæk et al., Citation2021). However, given this criticism, it is hard to understand how trust, such as in the cases of Sweden and South Korea, could increase during the pandemic.

Another limitation of my study is the unique focus of the added COVID-19 survey wave where many of the otherwise regularly included measures were missing or redesigned by the SHP team. This is particularly problematic when utilising methods that typically require consistent repeated measures across multiple survey waves. Thus, the special COVID-19 survey, while crucially important to observe the short-lived drop in social trust, unfortunately, excluded several potentially important variables that could help to make sense of the fall and rise of trust in Switzerland during the first year of the pandemic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alexander Saaranen

Alexander Saaranen is a doctoral candidate at the Department of Sociology at Lund University, Sweden. His research interests revolve around exploring development patterns of social trust. He is particularly interested in social trust dynamics among adolescents and impressionable years. This study is the first publication of his on-going research.

References

- Aassve, A., Alfani, G., Gandolfi, F., & Le Moglie, M. (2021). Epidemics and trust: The case of the Spanish Flu. Health Economics, 30(4), 840–857. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4218

- Ahmad, F., Jhajj, A. K., Stewart, D. E., Burghardt, M., & Bierman, A. S. (2014). Single item measures of self-rated mental health: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 398. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-398

- Anania, J., Mello, B. A. de, Angrist, N., Barnes, R., Boby, T., Cavalieri, A., Edwards, B., Webster, S., Ellen, L., Furst, R., Goldszmidt, R., Luciano, M., Majumdar, S., Nagesh, R., Pott, A., Wood, A., Wade, A., Zha, H., Furst, R., … Phillips, T. (2022). Variation in government responses to COVID-19. https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/publications/variation-government-responses-covid-19

- Anusic, I., Yap, S. C., & Lucas, R. E. (2014). Testing set-point theory in a Swiss national sample: Reaction and adaptation to major life events. Social Indicators Research, 119(3), 1265–1288. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0541-2

- Baker, W. D., & Oneal, J. R. (2001). Patriotism or opinion leadership? The nature and origins of the “rally ‘round the flag” effect. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 45(5), 661–687. doi:10.1177/0022002701045005006

- Bjørnskov, C. (2012). How does social trust affect economic growth? Southern Economic Journal, 78(4), 1346–1368. https://doi.org/10.4284/0038-4038-78.4.1346

- Brinig, M. F. (2011). Belonging and trust: Divorce and social capital. Brigham Young University Journal of Public Law, 25, 271.

- Brüderl, J., & Ludwig, V. (2015). Fixed-effects panel regression. The Sage Handbook of Regression Analysis and Causal Inference, 327, 357.

- Cullati, S. (2014). The influence of work-family conflict trajectories on self-rated health trajectories in Switzerland: A life course approach. Social Science & Medicine, 113, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.030

- Dawson, C. (2019). How persistent is generalised trust? Sociology, 53(3), 590–599. doi:10.1177/0038038517718991

- Delhey, J., & Newton, K. (2003). Who trusts?: The origins of social trust in seven societies. European Societies, 5(2), 93–137. doi:10.1080/1461669032000072256

- Delhey, J., Steckermeier, L. C., Boehnke, K., Deutsch, F., Eichhorn, J., Kühnen, U., & Welzel, C. (2023). Existential insecurity and trust during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Germany. Journal of Trust Research, 13(0), 140–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2023.2223184

- Dinesen, P. T. (2012). Parental transmission of trust or perceptions of institutional fairness: Generalized trust of non-western immigrants in a high-trust society. Comparative Politics, 44(3), 273–289. doi:10.5129/001041512800078986

- Dinesen, P. T. (2013). Where you come from or where you live? Examining the cultural and institutional explanation of generalized trust using migration as a natural experiment. European Sociological Review, 29(1), 114–128. doi:10.1093/esr/jcr044

- Dinesen, P. T., & Bekkers, R. (2017). The foundations of individuals’ generalized social trust: A review. In Trust in social dilemmas. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190630782.003.0005

- Dinesen, P. T., Schaeffer, M., & Sønderskov, K. M. (2020). Ethnic diversity and social trust: A narrative and meta-analytical review. Annual Review of Political Science, 23(1), 441–465. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-052918-020708

- Dinesen, P. T., Sønderskov, K. M., Sohlberg, J., & Esaiasson, P. (2022). Close (causally connected) cousins?: Evidence on the causal relationship between political trust and social trust. Public Opinion Quarterly, 86(3), 708–721. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfac027

- Díaz Ramírez, M., Veneri, P., & Lembcke, A. C. (2022). Where did it hit harder? Understanding the geography of excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Regional Science, 62(3), 889–908. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12595

- Draper, N. R., & Smith, H. (1998). Applied regression analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

- Ervasti, H., Kouvo, A., & Venetoklis, T. (2019). Social and institutional trust in times of crisis: Greece, 2002–2011. Social Indicators Research, 141(3), 1207–1231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1862-y

- Esaiasson, P., Sohlberg, J., Ghersetti, M., & Johansson, B. (2021). How the coronavirus crisis affects citizen trust in institutions and in unknown others: Evidence from ‘the Swedish experiment’. European Journal of Political Research, 60(3), 748–760. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12419

- Fairbrother, M., & Martin, I. W. (2013). Does inequality erode social trust? Results from multilevel models of US states and counties. Social Science Research, 42(2), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.09.008

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Free Press.

- Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2006). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge university press.

- Giachino, M., Valera, C., Velásquez, S., Dohrendorf-Wyss, M., Rozanova, L., & Flahault, A. (2020). Understanding the dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic: A real-time analysis of Switzerland’s first wave. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8825. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238825

- Giordano, G. N., & Lindström, M. (2016). Trust and health: Testing the reverse causality hypothesis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(1), 10–16. doi:10.1136/jech-2015-205822

- Giordano, G. N., Mewes, J., & Miething, A. (2019). Trust and all-cause mortality: A multilevel study of US general social survey data (1978–2010). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73(1), 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2018-211250

- Glanville, J. L., & Paxton, P. (2007). How do we learn to trust? A confirmatory tetrad analysis of the sources of generalized trust. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70(3), 230–242. doi:10.1177/019027250707000303

- Glanville, J. L., Andersson, M. A., & Paxton, P. (2013). Do social connections create trust? An examination using new longitudinal data. Social Forces, 92(2), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sot079

- Glatz, C., & Schwerdtfeger, A. (2022). Disentangling the causal structure between social trust, institutional trust, and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 163(3), 1323–1348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02914-9

- Hale, T., Angrist, N., Goldszmidt, R., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., Webster, S., Cameron-Blake, E., Hallas, L., Majumdar, S., & Tatlow, H. (2021). A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker). Nature Human Behaviour, 5(4), 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8

- Helliwell, J. F., & Wang, S. (2010). Trust and well-being. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2018). New evidence on trust and well-being. In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of social and political trust (pp. 409–446). Oxford University Press.

- Herreros, F. (2015). Ties that bind: Family relationships and social trust. Rationality and Society, 27(3), 334–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043463115593122

- Huang, J., van den Brink, H. M., & Groot, W. (2011). College education and social trust: An evidence-based study on the causal mechanisms. Social Indicators Research, 104(2), 287–310. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9744-y

- Hudson, J. (2006). Institutional trust and subjective well-being across the EU. Kyklos, 59(1), 43–62. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6435.2006.00319.x

- Kawohl, W., & Nordt, C. (2020). COVID-19, unemployment, and suicide. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(5), 389–390. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30141-3

- Kiang, M. V., Irizarry, R. A., Buckee, C. O., & Balsari, S. (2020). Every body counts: Measuring mortality from the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(12), 1004–1007. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-3100

- Kijewski, S., & Freitag, M. (2018). Civil war and the formation of social trust in Kosovo: Posttraumatic growth or war-related distress? Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62(4), 717–742. doi:10.1177/0022002716666324

- Kontis, V., Bennett, J. E., Rashid, T., Parks, R. M., Pearson-Stuttard, J., Guillot, M., Asaria, P., Zhou, B., Battaglini, M., Corsetti, G., McKee, M., Di Cesare, M., Mathers, C. D., & Ezzati, M. (2020). Magnitude, demographics and dynamics of the effect of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on all-cause mortality in 21 industrialized countries. Nature Medicine, 26(12), 1919–1928. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1112-0

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press. https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-Fromm/frontdoor/index/index/docId/28136

- Kumove, M. (2023). Take five? Testing the cultural and experiential theories of generalised trust against five criteria. Political Studies, 00323217231224971.

- Kye, B., & Hwang, S.-J. (2020). Social trust in the midst of pandemic crisis: Implications from COVID-19 of South Korea. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 68, 100523. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100523

- Laurence, J. (2015). (Dis)placing trust: The long-term effects of job displacement on generalised trust over the adult lifecourse. Social Science Research, 50, 46–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.11.006

- Lersch, P. M. (2023). Change in personal culture over the life course. American Sociological Review, 88(2), 220–251. doi:10.1177/00031224231156456

- Listhaug, O., & Jakobsen, T. G. (2018). Foundations of political trust. In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of social and political trust (pp. 559–578). Oxford University Press.

- Lizardo, O. (2017). Improving cultural analysis: Considering personal culture in its declarative and nondeclarative modes. American Sociological Review, 82(1), 88–115. doi:10.1177/0003122416675175

- Lucas, R. E. (2007). Adaptation and the set-point model of subjective well-being: Does happiness change after major life events? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 75–79. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00479.x

- Mattes, R., & Moreno, A. (2018). Social and political trust in developing countries: sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of social and political trust (pp. 357–384). Oxford University Press.

- Mewes, J. (2014). Gen (d) eralized trust: Women, work, and trust in strangers. European Sociological Review, 30(3), 373–386. doi:10.1093/esr/jcu049

- Mewes, J., & Giordano, G. N. (2017). Self-rated health, generalized trust, and the affordable care act: A US panel study, 2006–2014. Social Science & Medicine, 190, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.012

- Mewes, J., Fairbrother, M., Giordano, G. N., Wu, C., & Wilkes, R. (2021). Experiences matter: A longitudinal study of individual-level sources of declining social trust in the United States. Social Science Research, 95, 102537. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102537

- New Coronavirus 2019-nCoV: first confirmed case in Switzerland. (n.d.). Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/das-bag/aktuell/medienmitteilungen.msg-id-78233.html

- Newton, K. (2001). Trust, social capital, civil society, and democracy. International Political Science Review, 22(2), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512101222004

- O’Reilly, A. (2020). “Trying to function in the unfunctionable”: Mothers and COVID-19. Journal of the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement.

- Ortiz-Ospina, E., & Roser, M. (2016). Trust. Our world in data. https://ourworldindata.org/trust [Online Resource].

- Ostrom, E., & Ahn, T.-K. (2009). The meaning of social capital and its link to collective action. Handbook of Social Capital: The Troika of Sociology, Political Science and Economics, 17.

- Padhan, R., & Prabheesh, K. P. (2021). The economics of COVID-19 pandemic: A survey. Economic Analysis and Policy, 70, 220–237. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2021.02.012

- Power, K. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 16(1), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2020.1776561

- Rothstein, B. (2011). The quality of government: Corruption, social trust, and inequality in international perspective. University of Chicago Press.

- Rothstein, B., & Stolle, D. (2008). The state and social capital: An institutional theory of generalized trust. Comparative Politics, 40(4), 441–459. doi:10.5129/001041508X12911362383354

- Salmi, V., Smolej, M., & Kivivuori, J. (2007). Crime victimization, exposure to crime news and social trust among adolescents. YOUNG, 15(3), 255–272. doi:10.1177/110330880701500303

- Selby, K., Durand, M.-A., Gouveia, A., Bosisio, F., Barazzetti, G., Hostettler, M., D’Acremont, V., Kaufmann, A., & von Plessen, C. (2020). Citizen responses to government restrictions in Switzerland during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey. JMIR Formative Research, 4(12), e20871. doi:10.2196/20871

- Smithson, M. (2003). Confidence intervals. SAGE.

- Sønderskov, K. M., & Dinesen, P. T. (2014). Danish exceptionalism: Explaining the unique increase in social trust over the past 30 years. European Sociological Review, 30(6), 782–795. doi:10.1093/esr/jcu073

- Sønderskov, K. M., & Dinesen, P. T. (2016). Trusting the state, trusting each other? The effect of institutional trust on social trust. Political Behavior, 38(1), 179–202. doi:10.1007/s11109-015-9322-8

- StataCorp. (2019). Stata statistical software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC.

- Stolle, D. (2002). Trusting strangers–the concept of generalized trust in perspective. Österreichische Zeitschrift Für Politikwissenschaft, 31(4), 397–412.

- Subramanian, S. V., Kim, D. J., & Kawachi, I. (2002). Social trust and self-rated health in US communities: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Urban Health, 79(1), S21–S34. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/79.suppl_1.S21

- Thoresen, S., Blix, I., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Birkeland, M. S. (2021). Trusting others during a pandemic: Investigating potential changes in generalized trust and its relationship with pandemic-related experiences and worry. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.698519

- Tillmann, R., Voorpostel, M., Antal, E., Dasoki, N., Klaas, H., Kuhn, U., Lebert, F., Monsch, G.-A., & Ryser, V.-A. (2022). The Swiss household panel (SHP). Jahrbücher Für Nationalökonomie Und Statistik, 242(3), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2021-0039

- Umer, H. (2023). Stability of pro-sociality and trust amid the COVID-19: Panel data from The Netherlands. Empirica, 50(1), 255–287. doi:10.1007/s10663-022-09557-6

- Uslaner, E. M. (2002). The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge University Press.

- Uslaner, E. M. (2010). Trust and the economic crisis of 2008. Corporate Reputation Review, 13(2), 110–123. doi:10.1057/crr.2010.8

- Uslaner, E. M. (2014). The economic crisis of 2008, trust in government, and generalized trust. In Public trust in business. Cambridge University Press.

- Uslaner, E. M. (2015). Measuring generalized trust: In defense of the ‘standard’question. In Handbook of research methods on trust. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Uslaner, E. M. (2018). The study of trust. In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of social and political trust (pp. 3–13). Oxford University Press.

- van der Cruijsen, C., de Haan, J., & Jonker, N. (2022). Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected public trust? Evidence for the US and The Netherlands. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 200, 1010–1024. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2022.07.006

- Warren, M. E. (2018). Trust and democracy. In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of social and political trust (pp. 75–94). Oxford University Press.

- Węziak-Białowolska, D. (2016). Attendance of cultural events and involvement with the arts—impact evaluation on health and well-being from a Swiss household panel survey. Public Health, 139, 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.06.028

- Wollebæk, D., Fladmoe, A., & Steen-Johnsen, K. (2021). ‘You can’t be careful enough’: Measuring interpersonal trust during a pandemic. Journal of Trust Research, 11(2), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2022.2066539

- Yamamura, E., Tsutsui, Y., Yamane, C., Yamane, S., & Powdthavee, N. (2015). Trust and happiness: Comparative study before and after the great East Japan earthquake. Social Indicators Research, 123(3), 919–935. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0767-7

- Zangger, C. (2023). Localized social capital in action: How neighborhood relations buffered the negative impact of COVID-19 on subjective well-being and trust. SSM-Population Health, 21, 101307. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101307

- Zimmermann, B. M., Fiske, A., McLennan, S., Sierawska, A., Hangel, N., & Buyx, A. (2022). Motivations and limits for COVID-19 policy compliance in Germany and Switzerland. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 11(8), 1342–1353.

Appendix

Table A1. First differences regression – within-individual factors for the ‘drop’ in trust between t1 and t2.

Table A2. First differences regression – within-individual factors for the ‘rise’ in trust between t2 and t3.

Table A3. Patterns of meaningful change in social trust (Ntotal = 5843).

Table A4. Multinominal logistic regression analysis: summer of 2020 data (Nvalid = 4049).

Figure A1. Wave-to-wave challenge-generating the ‘measningful change’ variable. Note: 2018 = Reference datapoint |1 = 2019; 2 = the extra COVID-19 wave; 3 = 2020.

Table A5. Fixed-effects regression analysis – trust development from 2008 to 2021.

Table A6. Descriptive statistics: correlations matrix.