Abstract

Mobile technologies are promising tools to scaffold teaching practice. In this study, we developed and tested a mobile app for teacher education. This mobile portfolio enables multimedia-based note-taking, reflection, and discussion with peers and mentors. We conducted two studies to explore the effect of design variants and use scenarios on the app’s acceptance. In the first study with N = 83 pre-service primary school teachers, technology acceptance was higher for those using the app with multimedia note-taking functionality than for those using the same app with this functionality disabled. In the second study with N = 81 pre-service teachers, those using the app together with their mentor teachers reported levels of technology acceptance similar to those who used the app exclusively among themselves. In consequence, a mobile portfolio app would be met with higher acceptance if it builds reflection upon multimedia note-taking both with and without the inclusion of mentors.

Introduction: Digital portfolios in teacher education

This study provides empirical evidence with regard to the acceptance of pre-service teachers of using a mobile portfolio app in teaching practice. In theory, such an app provides many advantages for teacher education—in particular with regard to teacher reflection. In recent decades, reflection on teaching practice has been regarded as one of the core components of teacher education (Darling-Hammond & Richardson, Citation2009; Korthagen et al., Citation2006; Schön, Citation1987). Teachers at all career levels are expected to reflect on classroom experiences and consciously address practical problems. Reflection is considered to be important for linking teaching skills acquired by guided practice with theoretical knowledge from the teacher students’ academic studies. However, research has shown that it is very difficult to design reflective activities in teacher education that meet these high expectations (Beauchamp, Citation2015; Cohen et al., Citation2013; Zeichner & Liu, Citation2010). Instead, pre-service teachers follow questionable models of senior teachers and copy “tricks of the trade” without deeper reflection, without linking theory to practice, or even without substantial professional development. To address this issue, digital technologies are increasingly being explored for their potential to support reflective teacher education, particularly through digital videos, portfolios, weblogs, and mobile devices (Baran, Citation2014; Feder & Cramer, Citation2019; Fessl et al., Citation2015; Kori et al., Citation2014).

Digital portfolios for professional development

A digital portfolio (also referred to as an “e-portfolio” or “ePortfolio”) has been defined as a software to collect digital artifacts resulting from working or learning processes (Lorenzo & Ittelson, Citation2005; Stefani et al., Citation2007). In contrast to traditional hardcopy portfolios, digital portfolios can include multimedia artifacts such as audio or video records as well as all functionalities of digital environments. Using a digital portfolio, artifacts can be organized in a hyperlinked structure, shared, and discussed with specific audiences online. Digital portfolios can serve different purposes: to illustrate progress, showcase abilities, and serve as a means for assessment (Abrami & Barrett, Citation2005). As a formative tool, digital portfolios are used to document and reflect during professional development processes. In formal learning settings, portfolios can also be used as the focus of summative examinations at the end of a learning process. All of these types of digital portfolios can be free-form or structured along competency frameworks; they can be created for individuals, groups, and even organizations. Digital portfolios are often heralded as technologies that have the potential to transform the culture of learning, for example, by bridging informal and formal domains, by enabling more self-directed approaches to studying, and by providing means for lifelong learning across organizations and contexts in a personal learning environment (Attwell, Citation2007; Dabbagh & Kitsantas, Citation2012; Hricko, Citation2017). Although specialized e-portfolio platforms such as Mahara (www.mahara.org) or other learning management systems that include e-portfolio functionality specifically support the workflow of collection, organization, and presentation of digital artifacts, high-performance e-portfolios can also be built using other generic platforms (e.g., simple websites, weblogs, or social media sites).

After a decade of research, studies overwhelmingly show that digital portfolios are used effectively when they are deeply integrated in an institutional culture of learning and assessment and scaffolded by peers and mentors (Beckers et al., Citation2016; Bryant & Chittum, Citation2013). Previous research emphasizes the affordances of digital portfolios for supporting reflective practice and professional development. In particular, the integration of images and text is a way to better understand personal meanings and experiences (Birello & Pujola Font, 2020). Further, digital portfolios provide remote access, allow for asynchronous peer interactions, and thus overcome time-space limitations (Ahmed & Ward, Citation2016). These affordances could be summarized along the three dimensions of Zubizarreta’s (Citation2009) portfolio model, which proposes documentation and evidence, reflection, and collaboration/mentoring as the fundamental elements. Despite these promising affordances, digital portfolios have not been considered in overarching meta-analyses on effective higher education (Schneider & Preckel, Citation2017). Thus, more research is needed to explore their potential.

Mobile apps for professional development

Although some e-portfolio tools, such as Mahara (www.mahara.org), have mobile style sheets and sometimes even a complementary app with limited functionality (e.g., Mahara Mobile), they are mainly designed for use on desktop computers, which might feel outdated. With the diffusion of social media, many students have become accustomed to establishing their presence and communicating on these platforms using mobile devices. Entries on personal social media accounts typically consist of pictures, videos, and short snippets of text along with forwards, likes, and comments. Posts are either public or accessible to a specific group of friends. Next to leisure purposes, social media activities play a key role in becoming accustomed to student life in college (DeAndrea et al., Citation2012; Tess, Citation2013). Further, pre-service and in-service teachers are among those who have started to use social media voluntarily for professional development purposes (Carpenter & Krutka, Citation2015; Greenhow et al., Citation2018; Prestridge, Citation2019). In contrast to desktop applications, mobile devices are expected to have several advantages: artifacts and entries can be collected on the fly in practical situations, and the integration of audio and video documents is more seamless due to the improved handling of recording when compared to desktop or laptop computers. Mobile apps also have several affordances, such as seamless usability, multi-modality, the ability to access material anywhere and anytime, and compatibility (Tang & Hew, Citation2017), which allow a ubiquitous and smooth use of digital portfolios in professional learning practices. Thus, specific reflection apps have been developed in diverse domains of learning, such as K–12 education (Leinonen et al., Citation2016; McNicol et al., Citation2014; Petko, Citation2011), general education (Corlett et al., Citation2005), medical education (Garrett & Jackson, Citation2006; Könings et al., Citation2016; Renner et al., Citation2014, Citation2016), or vocational education (Aprea & Cattaneo, Citation2019; Mauroux et al., Citation2014).

Technology acceptance of digital portfolios and mobile apps for professional development

Technology acceptance is particularly important for digital portfolios if these tools are to be used as tools for self-directed life-long learning. In teacher education, most studies using digital portfolios have employed traditional desktop-based digital portfolio platforms (Oner & Adadan, Citation2011; Roberts et al., Citation2016; Strudler & Wetzel, Citation2005). While some studies report that the acceptance of traditional e-portfolio platforms in higher education is positive (Ciesielkiewicz, Citation2019; Fong et al., Citation2014; Tur & Marin, Citation2013), others have reported low acceptance and few learning-related positive effects (Beckers et al., Citation2016). With regard to teacher education, technology acceptance seems to be low (Abrami & Barrett, Citation2005; Feder & Cramer, Citation2019). Some studies have been conducted with the e-portfolio system Mahara (Klampfer & Koehler, Citation2013; Shroff et al., Citation2013) or Eduportfolio (Karsenti et al., Citation2014); however, other studies have evaluated traditional weblogs as a form of portfolio (Bernhardt & Wolf, Citation2012; Cakir, Citation2013; Petko et al., Citation2017). Here, weblogs and microblogs have been perceived more positively when focusing on the exchange of pictures, video, and links (Barton & Ryan, Citation2014; Quek, Citation2009). When determining predictors of technology acceptance, the vast majority of these studies follow the well-known Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, Citation1989; Fong et al., Citation2014) or the more elaborate UTAUT Model (Venkatesh et al., Citation2012). A literature review of e-portfolio acceptance in higher education reports ease of use, usefulness, ownership, and technological competence as among the most cited factors (Mobarhan et al., Citation2014).

Relatively few studies have examined factors of technology acceptance of mobile portfolio apps so far. In the context of vocational education, technology acceptance of mobile tools has been positively related to perceived ease of use and number of recorded artifacts (Mauroux et al., Citation2014). Other studies were able to show positive effects that might have a relation with technology acceptance. One study involving healthcare professionals asked them to evaluate a reflection app and found that users who received coaching support made fewer entries per working day but recorded more relevant learning moments compared to users without coaching support (Könings et al., Citation2016). Another study investigating hospital staff using a reflection app reported a positive relation between reflection behavior and job satisfaction (Renner et al., Citation2014). Although there seems to be a degree of consistency among the findings of these studies, there is a lack of experimental studies using different versions of the same tool and training settings to empirically understand the acceptance of different features and the affordances these tools offer for teacher education (Baran, Citation2014).

Research question and hypotheses

Based on findings from prior research, our study investigated the potential benefits of mobile digital portfolios in more detail. These benefits include a) noticing in-action, which consists of writing notes, taking pictures, and recording audio snippets and videos as a starting point for further reflection (Goodwin, Citation1994; Star & Strickland, Citation2008), and b) the sharing and discussion of moments and reflections by creating a “hybrid space” between pre-service teachers and teacher mentors (Zeichner, Citation2010). Collecting artifacts—here, records of practice—and sharing and discussing these artifacts as well as their related reflections with others are the supposed core affordances of digital portfolios and similar software in the context of learning (Deng & Yuen, Citation2011; Harun et al., Citation2021; Robertson, Citation2011). Despite these affordances, technology acceptance is far from guaranteed. Research on digital portfolios has repeatedly shown low student participation and low levels of technology acceptance (Beckers et al., Citation2016; Feder & Cramer, Citation2019). However, the integration and acceptance of mobile portfolios in teaching internships has scarcely been explored in previous studies. Therefore, the study addressed the following research question:

RQ: How does technology acceptance of a mobile portfolio app develop over the course of a teacher education internship depending on app functionality and app usage?

In particular, we investigated the following two hypotheses:

H1a: Pre-service teachers who use a mobile portfolio app with multimedia note-taking functionalities will show higher levels of technology acceptance compared to those of pre-service teachers from the control group without the mobile app.

H1b: Pre-service teachers who use a mobile portfolio app without multimedia note-taking functionalities will not show higher levels of technology acceptance compared to those of pre-service teachers from the control group without the mobile app.

H2: Pre-service teachers who used the app in close collaboration with a teacher mentor will show higher levels of technology acceptance compared to those of pre-service teachers who used the app without mentors.

The hypotheses were tested for all sub-aspects of technology acceptance, as detailed below.

Material and methods

Study design

A specialized mobile portfolio app was tested in two randomized controlled field trials with pre-service primary education teachers. Each study was conducted over the course of a four-week teaching internship in primary schools. For this internship, pairs of pre-service teachers were assigned to a primary school class where they taught full-time under the supervision of the regular class teacher. Furthermore, all interns received visits from mentors from the University of Teacher Education. In addition to carefully planning all lessons using traditional forms, teachers documented their experiences and reflected on them using the app in relation to a Swiss adaptation of the American INTASC standards (Council of Chief State School Officers, Citation2013). In the first study, which was conducted in January 2019, we tested H1. Pre-service teachers were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups or a control group:

Experimental group 1: Use of a mobile portfolio app with multimedia-based note-taking functionality and written reflections.

Experimental group 2: Use of a mobile portfolio app without note-taking functionality that is used for written reflections only.

Control group: No use of a mobile portfolio app, traditional written reflective report.

In the second study, which was conducted in January 2020, we focused on H2. Pre-service teachers were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups:

Experimental group 1: Collaborative use of the app together with teacher mentors.

Experimental group 2: Individual use of the app without collaboration with teacher mentors.

Material

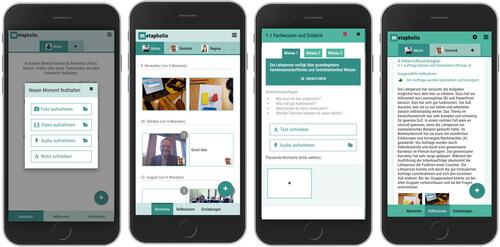

For the purposes of this study, a new teacher education app called Metapholio was developed and tested (Petko et al., Citation2019; Michos et al., Citation2022). The app is freely available for all major mobile operating systems (www.metapholio.ch). The workflow using the app can be described in six steps: (1) Installing the app and creating an account. The app can be set to German (default language), English and French. (2) Inviting fellow pre-service teachers and teacher educators. (3) Collecting noteworthy moments, that is, taking text-based notes, pictures, or recording audio and video files during lessons. This can be done either by the pre-service teachers themselves or by invited peers and mentors. (4) Reflecting on moments, that is, selecting several moments and writing or expressing a reflection out loud regarding these notes and records. All reflections are scaffolded by short prompts (“Describe what you did,” “How did this work out?”, “What can be improved?”, and “What theories could be helpful in this regard?”), as prompts have been shown to improve the reflection on records of practice (Blomberg et al., Citation2014; Seidel et al., Citation2011). (5) Using moments and reflections as a starting point for comments and discussions between pre-service teachers and invited peers and mentors. (6) Exporting moments, reflections, and interactions as a portfolio for documentation. Steps 3 and 4 are illustrated in .

Figure 1. Core functionality of the Metapholio App (from left to right): Collecting moments, a collections of moments, writing a reflection, a written reflection.

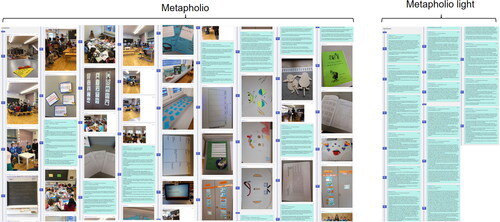

For the purposes of Study 1, experimental group 1 (the Metapholio group) received an app that supported all six steps of the reflection process, while experimental group 2 (the Metapholio light group) received a reduced version of the app where Step 3 was not supported. Two examples of resulting student portfolios over the course of the internship are depicted in . The left panel of shows an example from the Metapholio group with numerous pictures, audio and video records next to text-based reflections, while the right panel is an example from the Metapholio light group missing these multimedia records and consisting only of text-based reflections.

Figure 2. Examples of two student portfolios. Left: Example from the Metapholio group. Right: Example from the Metapholio light group.

For the purposes of Study 2, both experimental groups worked with the full version of the app. In experimental group 1 (Metapholio mentored), pre-service teachers as well as their mentors work collaboratively with the app; in experimental group 2 (Metapholio unmentored), the app was distributed to pre-service teachers but not to their mentors.

Sample

In both studies, the samples consisted of the full cohort of pre-service primary education teachers enrolled in a teacher education institution in central Switzerland for two consecutive years. In both studies, a large majority of the pre-service teachers were between 18 and 25 years of age. The four-week internship represented the first time that these pre-service teachers had to teach independently over a longer period.

In Study 1, the sample consisted of 83 pre-service teachers (64 female and 19 male). Experimental group 1 (Metapholio) consisted of n = 28 pre-service teachers, n = 29 pre-service teachers were randomly assigned to experimental group 2 (Metapholio light), and n = 26 pre-service teachers were assigned to the control group.

In Study 2, the sample included 81 pre-service teachers (63 female, 17 male, and one omitting to report their gender). Of these pre-service teachers, n = 39 were randomly assigned to experimental group 1 (Metapholio mentored) and n = 42 to experimental group 2 (Metapholio unmentored).

A prior power analysis indicated that these sample sizes could predict an effect size of f2 = .15 with an assumed significance level of p = .05 and a statistical power of close to 1-β = .90 in a linear regression analysis model with two predictors (calculated with G*Power 3.1.9.2).

Measures

In both studies, a technology acceptance survey with regard to mobile digital portfolios for teacher education was administered in the week prior to the internship (pretest, t1) and at the end of the last week of the four-week teaching placement (post-test, t2). In the pretest, the pre-service teachers judged their hypothetical technology acceptance without knowing the Metapholio app. In the post-test, the experimental groups judged their technology acceptance of the Metapholio app, while the control group in Study 1 continued rating their acceptance of such a technology without knowing the app. We employed the standardized UTAUT2 questionnaire on technology acceptance by Venkatesh et al. (Citation2012) and adapted the wording slightly to address a digital portfolio app. The UTAUT2 questionnaire is one of the most widely adopted questionnaires for technology acceptance, especially with regard to educational applications (Scherer et al., Citation2020; Williams et al., Citation2015). UTAUT2 measures eight interrelated aspects of technology acceptance. The items of the subscales were slightly reworded to reflect the setting of using a mobile app for reflecting on teaching practice: performance expectancy (4 items, sample item: “I would find such a mobile app useful in my daily duties in teaching practice”), effort expectancy (4 items, sample item: “Learning how to use such an app is easy for me”), social influence (3 items, sample item: “People who are important for my teaching practice think that I should use such an app”), facilitating conditions (4 items, sample item: “I have the resources necessary to use such an app”), hedonic motivation (3 items, sample item: “Using such an app is fun”), habit (4 items, sample item: “The use of such an app has become a habit for me”), and behavioral intention (3 items, sample item: “I would like to use such an app in my future teaching practice.”). As the app was free for all pre-service teachers and teacher mentors, the subscale measuring price value was not considered in these studies. Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). The theoretical model behind UTAUT2 assumes that behavioral intention is influenced by all other aspects in the model. Further, behavioral intention is expected to influence actual use.

Analysis

After checking the scale reliability for all questionnaire constructs, we computed mean composite scores for each subscale of the UTAUT2 questionnaire. To provide a basic overview of trends in the data, descriptive mean scores and standard deviations as well as simple line graphs are computed for each sub-aspect and for each sub-group regarding pretest and post-test scores in each study. To check H1 and H2, we conducted multilevel linear regression models (random intercept only) with time points (level 1) nested in pre-service teachers (level 2). For group comparisons, we included a dummy coded group variable and an interaction term with the time variable. Analyses were conducted using R 3.6 along with the lmerTest 3.1-3 and ggplot2 3.2.1 packages.

Results

Results of study 1: Technology acceptance of metapholio versus metapholio light versus control

In Study 1, the UTAUT2 questionnaire achieved high reliability in the pretest as well as in the post-test on all sub-aspects, measured with Cronbach’s alpha: performance expectancy (Cαpre = .86; Cαpost = .91), effort expectancy (Cαpre = .87; Cαpost = .88), and social influence (Cαpre = .91; Cαpost = .96), facilitating conditions (Cαpre = .87; Cαpost = .62), hedonic motivation (Cαpre = .95; Cαpost = .92), habit (Cαpre = .73; Cαpost = .82), and behavioral intention (Cαpre = .84; Cαpost = .87). The only exception was the rating of the facilitating conditions subscale, which did not appear to be reliable in the post-test. Thus, the results concerning this subscale need to be treated with caution.

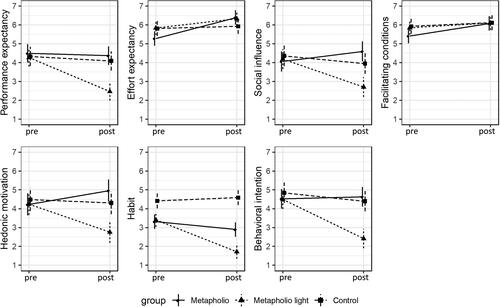

As described above, we compared the development of technology acceptance in two experimental groups of pre-service teachers—one working with either a full-fledged version of an app for teacher reflection during internships (Metapholio) and another working with a reduced version that lacked mobile note-taking functionalities (Metapholio light)—and one control group not working with a specialized app of any kind. Descriptive statistics on mean scores of pre-service teacher ratings with regard to the seven aspects of technology acceptance for both experimental groups and the control group are summarized in .

Table 1. Treatment group comparisons of means and standard deviations (in parentheses) of UTAUT2 ratings (pretest and post-test)

depicts the trends in group means over time along with the confidence intervals for the group means.

Figure 3. Performance expectancy pre-post *group; effort expectancy pre-post *group; social influence pre-post *group; facilitating conditions pre-post *group; hedonic motivation pre-post *group; habit pre-post *group; behavioral intention pre-post *group.

To test whether the changes were significant, multilevel random-intercept linear regression models were conducted with time points (level 1) nested in participants (level 2) for each sub-aspect of technology acceptance. lists all regression coefficients with their respective standard errors in parentheses. The term intercept can be interpreted as the mean value for the control group at the pretest, and “t” represents the slope for the control group. With regard to the treatment group Metapholio, groupMetaholio is the relative mean at the pretest, and t:groupMetapholio is the relative slope with respect to the control group. Similarly, groupMetapholio light is the relative mean at the pretest, and t:groupMetapholio light is the relative slope for the Metapholio light group with respect to the control group. None of the slope coefficients for the control group were significant, indicating that for the control group, the scores of all the subscales did not change over time. The experimental group Metapholio had marginally significant lower mean values at the pretest than the control group for the subscales effort expectancy (-0.53, p < .10) and facilitating conditions (-0.51, p < .10). Compared to the control group, the Metapholio group recorded significantly lower mean values for habit (-1.1, p < .001), whereas we observed a significant over time for the effort expectancy (1.0, p < .01), social influence (0.95, p < .10), hedonic motivation (0.92, p < .10), and habit (-0.59, p < .10) subscales. For the Metapholio light group, only the habit subscale (-1.01, p < .001) had a significantly different mean at the pretest compared to the control group. Between the pre- and the post-test, pre-service teachers in the Metapholio light group showed significant and negative developments in almost all aspects of technology acceptance (compared to the control group), except effort expectancy and facilitating conditions. In the pretest, all group means were positive and similar across all groups, except Habit, which was below 3.5 in both experimental groups.

Table 2. Multilevel linear regression models comparing the development of UTAUT2 variables t0-t4 across treatment groups

Summing up these results, pre-service teachers working with a reduced version of the app (the Metapholio light group) showed clear changes in technology acceptance toward more negative ratings. In this group, performance expectancy, social influence, hedonic motivation, habit, and behavioral intention declined significantly. By comparison, the technology acceptance ratings of pre-service teachers in the Metapholio group showed small and rather positive developments of technology acceptance ratings, while the control group seemed to maintain their ratings.

Based on these findings, H1a was only partially confirmed. Only the group working with the full version of the app developed higher technology acceptance of mobile portfolios compared to the control group with regard to effort expectancy. In all other aspects, there was a tendency toward a more positive development of technology acceptance, but the results are not significant.

By contrast, H1b needed to be entirely rejected. Pre-service teachers working with a reduced version of the app showed a clearly negative development of technology acceptance toward mobile portfolios compared to pre-service teachers in the control group, and this tendency was found for almost all aspects. Exceptions were ratings on effort expectancy and facilitating conditions, for which this experimental group did not differ from the control group.

Results of study 2: Technology acceptance of metapholio mentored versus metapholio unmentored

In Study 2, the UTAUT2 questionnaire showed good reliability across all subaspects: performance expectancy (Cαpre = .94; Cαpost = .92), effort expectancy (Cαpre = .95; Cαpost = .81), social influence (Cαpre = .92; Cαpost = .92), facilitating conditions (Cαpre = .82; Cαpost = .70), hedonic motivation (Cαpre = .94; Cαpost = .94) , habit (Cαpre = .75; Cαpost = .79), and behavioral intention (Cαpre = .85; Cαpost = .91).

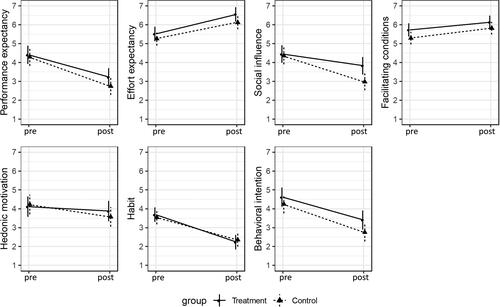

In this study, we compared the development of technology acceptance for two experimental groups of pre-service teachers, one using the full version of the app with teacher mentor support on this platform (treatment group) and one using the same full version but without teacher mentor support on this platform (control group). Descriptive results of mean scores of pre-service teacher ratings can be found in , and a graphical overview is presented in .

Figure 4. Performance expectancy pre-post *group; effort expectancy pre-post *group; social influence pre-post *group; facilitating conditions pre-post *group; hedonic motivation pre-post *group; habit pre-post *group and behavioral intention pre-post *group.

Table 3. Treatment group comparisons of means and standard errors of UTAUT2 (t1 – t2)

As in Study 1, we examined the longitudinal effects for each subscale with a multilevel linear regression model. Results from this analysis are summarized in . Again, an interaction term time*group was included for group comparisons. In , intercept is the mean value for the unmentored Metapholio group at the pretest, “t” is the slope/change for this group over time, groupMetapholio mentored is the relative mean for the treatment group at the pretest with respect to intercept, and t:groupMetapholio mentored can be interpreted as the relative slope/change for the mentored Metapholio group with respect to “t.” As displayed in , the slopes for the performance expectancy (-1.54), social influence (-1.37), behavioral intention (-1.49), hedonic motivation (-0.65), and habit (-1.19) subscales were all negative and significant at the 5% level. By contrast, the subscales effort expectancy (0.86) and facilitating conditions (0.52) were both positive and significant at the 1% level. For the mentored Metapholio group, only two coefficients approached marginal significance, namely, the relative slope for social influence (0.76) and the relative mean for facilitating conditions (0.43).

Table 4. Multilevel linear regression comparing the development of UTAUT2 ratings t1-t2 across treatment groups

Based on these findings, H2 clearly had to be rejected. There were hardly any differences with regard to the development of technology acceptance between pre-service teachers working with a mobile portfolio app in a mentored and those who were unmentored. Only the social influence factor tended to show a slightly more positive development in the mentored than in the unmentored treatment condition.

Discussion

Based on these results, we discuss our main research question, which sought to understand the development of technology acceptance of a mobile portfolio app over the course of a teacher education internship. Our results showed that prior to any intervention, pre-service teachers were overwhelmingly positive about the use of a mobile portfolio app in teaching internships. After using the app, pre-service teachers changed their views more dependently on the app’s functionalities but less dependently on the social context of its use. This longitudinal evaluation provides overarching observations for the acceptance of mobile portfolios in teacher education that point to the affordances and usage of mobile apps for reflection during teaching internships.

In the first study, a mobile portfolio app with multimedia note-taking functionality was perceived more positively compared to a control group documenting their reflective reports without an app. By contrast, when using a mobile portfolio app that did not include multimedia note-taking technology, acceptance sharply declined over time and resulted in lower acceptance of the app compared to a control group without an app. These results point to the observation that pre-service teachers’ acceptance of a mobile portfolio app depended on the functionalities offered in the app. This mirrors other findings with regard to the affordances of digital technologies for teacher education and their usefulness for reflection in teaching internships (Karsenti et al., Citation2014; Shroff et al., Citation2013). Multimodality seemed to be an important aspect of mobile portfolio apps for situations in which pre-service teachers had the opportunity to align multimedia records (e.g., recorded videos and pictures taken in classroom internships, with their written reflections; Barton & Ryan, Citation2014; Birello & Pujola Font, Citation2020). The use of multimedia has been considered in previous research as a very important element for demonstrating the process and evidence of the learning and achievements with digital portfolios (Le, Citation2012), and mobile portfolios may advance the use of multimedia for teacher reflections.

In the second study, pre-service teachers using a mobile portfolio app together with their mentor reported similar levels of technology acceptance when compared with pre-service teachers using the app on their own. The reason for this observation might be found in the aspect of ownership, which has been explored in previous studies (Mobarhan et al., Citation2014; Tur & Urbina, Citation2014) and which seems to be beneficial for pre-service teachers’ self-directed learning. This study suggests that co-ownership with mentors will not advance nor will it impede the overall technology acceptance of a mobile portfolio app. Chye et al. (Citation2019) recommended that pre-service teachers should have some control over deciding which aspects of e-portfolios are made visible to whom and when. This is clearly the case for the Metapholio app, where teacher mentors are able to contribute records and comments, but ultimately the control over the content remains with the pre-service teacher. Thus, the experience between the treatment groups might be less different from anticipated.

In considering the findings of both studies together, it is worth noting that the conditions of the treatment group Metapholio in Study 1 were virtually identical to those of the control group (i.e., using the app without mentor support) in Study 2. Thus, we expected both groups to show similar trends in the development of technology acceptance over time. Surprisingly, however, in Study 1, we observed a tendency for higher technology acceptance ratings over time, whereas in Study 2, among the analogous group, technology acceptance of the mobile portfolio was found to be lower at the end of the internship than at the beginning. Thus, other characteristics of the pre-service teacher cohorts who participated in each study might have influenced the results, and further factors, such as the overall perception of the teaching internship experience, should be taken into account. As both studies were field experiments, no additional control variables were included, as these were presumed to be controlled by the randomized design. However, it is unclear whether the results would be the same in a different teacher education program with different requirements and a different population.

Furthermore, some additional limitations need to be pointed out. First, all technology acceptance ratings were purely based on self-reports, presenting the usual limitations of such a data collection method (Chan, Citation2009). The actual interaction with the app during the internship experience was also not considered, and there might be differences between technology acceptance ratings of pre-service teachers using the app more or less intensively. Similarly, actual mentor activity and mentor attitudes were not considered in the second study. Although these effects were also controlled for by the randomized design of the study, they can be considered important mediating variables. We included a manipulation check in both studies (i.e., assuring that pre-service teachers and mentors both used the app on a regular basis); however, the frequency of use was not considered.

Despite these limitations, the above results add to those of previous studies showing varying acceptance of digital portfolios (Beckers et al., Citation2016; Bernhardt & Wolf, Citation2012; Cakir, Citation2013; Feder & Cramer, Citation2019; Petko et al., Citation2017) by demonstrating how different mobile apps’ functionalities and uses might affect technology acceptance. Future research might attempt to expand this discussion and examine how different types or uses of digital portfolios (e.g., progress, showcase and assessment; Abrami & Barrett, Citation2005) specifically relate to use on mobile platforms. Finally, these results provide further evidence and contribute to the body of knowledge on technology acceptance for digital and mobile portfolios in teacher education.

Conclusions

Mobile portfolios open up new opportunities for reflection in teacher education. However, technology acceptance evolves over time and should not be taken for granted. This study’s findings show that mobile portfolio apps should integrate the functionalities of multimedia note-taking together with written reflection to meet pre-service teachers’ requirements. Pre-service teachers might work alone or with teacher mentors without an impact on technology acceptance—at least in the teacher education setting of this particular study. These recommendations contribute to the integration of mobile portfolio apps in teaching internships. Further studies might more closely evaluate the teaching internship experience to better understand technology acceptance of mobile portfolios across different teacher education programs. Further, the evaluation of outcomes resulting from teaching internships, such as teacher self-efficacy, might provide a better picture and further emphasize the importance of technology acceptance. Finally, this study might inform the use of mobile portfolios in teacher education as well as in the professional development of in-service teachers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dominik Petko

Dominik Petko is full Professor for Teaching and Educational Technology at the University of Zurich. His research focuses on preparing and supporting teachers in times of digital change.

Andrea Cantieni

Andrea Cantieni has been a research associate at the University of Zurich. His main areas of expertise is educational research methods and statistics.

Regina Schmid

Regina Schmid is a lecturer and research associate at the Schwyz University of Teacher Education. Her research focuses on digital technologies in teacher education and the development of personalized learning environments.

Laura Müller

Laura Müller has been a research associate at the Schwyz University of Teacher Education. Her research was focused on digital technologies for teacher education.

Maike Krannich

Maike Krannich is a post-doc researcher at the University of Zurich. Her research is focused on teaching and learning processes in classrooms.

Konstantinos Michos

Konstantinos Michos is a post-doc researcher at the University of Zurich. He specialized in digital technologies in teacher education and data literacy.

References

- Abrami, P., & Barrett, H. (2005). Directions for research and development on electronic portfolios. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology/La Revue Canadienne de L’apprentissage et de la Technologie, 31(3). https://www.learntechlib.org/p/43165/.

- Ahmed, E., & Ward, R. (2016). Analysis of factors influencing acceptance of personal, academic and professional development e-portfolios. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.043

- Aprea, C., & Cattaneo, A. (2019). Designing technology enhanced learning environments in vocational education and training. In D. Guile & L. Unwin (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of vocational education and training (pp. 373–393). Wiley.

- Attwell, G. (2007). Personal learning environments – The future of eLearning. eLearning Papers (Www.elearningpapers.eu), 2(1), 1–8.

- Baran, E. (2014). A review of research on mobile learning in teacher education. Educational Technology & Society, 17(4), 17–32.

- Barton, G., & Ryan, M. (2014). Multimodal approaches to reflective teaching and assessment in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(3), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.841650

- Beauchamp, C. (2015). Reflection in teacher education: Issues emerging from a review of current literature. Reflective Practice, 16(1), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2014.982525

- Beckers, J., Dolmans, D., & Van Merriënboer, J. (2016). e-Portfolios enhancing students’ self-directed learning: A systematic review of influencing factors. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 32(2), 32–46.

- Bernhardt, T., & Wolf, K. D. (2012). Akzeptanz und Nutzungsintensität von Blogs als Lernmedium in Onlinekursen [Acceptance and Usage of Blogs in Online Courses]. In G. Csanyi, F. Reichl, & A. Steiner (Eds.), Digitale Medien: Werkzeuge für exzellente Forschung und Lehre (pp. 141–152). Waxmann.

- Birello, M., & Pujola Font, J. T. (2020). The affordances of images in digital reflective writing: An analysis of preservice teachers’ blog posts. Reflective Practice, 21(4), 534–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1781609

- Blomberg, G., Sherin, M. G., Renkl, A., Glogger, I., & Seidel, T. (2014). Understanding video as a tool for teacher education: Investigating instructional strategies to promote reflection. Instructional Science, 42(3), 443–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-013-9281-6

- Bryant, L. H., & Chittum, J. R. (2013). ePortfolio effectiveness: A (ill-Fated) search for empirical support. International Journal of ePortfolio, 3(2), 189–198.

- Cakir, H. (2013). Use of blogs in pre-service teacher education to improve student engagement. Computers & Education, 68, 244–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.05.013

- Carpenter, J. P., & Krutka, D. G. (2015). Social media in teacher education. In M. L. Niess & H. Gillow-Wiles (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education in the digital age (pp. 28–54). IGI Global.

- Chan, D. (2009). So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad? In C. E. Lance, R. J. Vandenberg (Eds.), Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity, and fable in the organizational and social sciences (pp. 309–336). Routledge.

- Chye, S., Zhou, M., Koh, C., & Liu, W. C. (2019). Using e-portfolios to facilitate reflection: Insights from an activity theoretical analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 85, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.06.002

- Cohen, E., Hoz, R., & Kaplan, H. (2013). The practicum in preservice teacher education: A review of empirical studies. Teaching Education, 24(4), 345–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2012.711815

- Corlett, D., Chan, T., Ting, J., Sharples, M., & Westmancott, O. (2005). Interactive logbook: A mobile portfolio and personal development planning tool. mLearn 2005 4th World Conference on mLearning, Cape Town. Retrieved October 25-28, 2005, from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mike-Sharples/publication/232804714_Interactive_Logbook_a_mobile_portfolio_and_personal_development_planning_tool/

- Council of Chief State School Officers. (2013). InTASC model core teaching standards and learning progressions for teachers 1.0: A resource for ongoing teacher development. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED558115.pdf

- Ciesielkiewicz, M. (2019). The use of e-portfolios in higher education: From the students’ perspective. Issues in Educational Research, 29(3), 649–667.

- Dabbagh, N., & Kitsantas, A. (2012). Personal learning environments, social media, and self-regulated learning: A natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.06.002

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Richardson, N. (2009). Research review/teacher learning: What matters. Educational Leadership, 66(5), 46–53.

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- DeAndrea, D. C., Ellison, N. B., LaRose, R., Steinfield, C., & Fiore, A. (2012). Serious social media: On the use of social media for improving students’ adjustment to college. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.05.009

- Deng, L., & Yuen, A. H. (2011). Towards a framework for educational affordances of blogs. Computers & Education, 56(2), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.09.005

- Feder, L., & Cramer, C. (2019). Portfolioarbeit in der Lehrerbildung. Ein systematischer Forschungsüberblick [Portfolio in teacher education. A research synthesis]. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 22(5), 1225–1245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-019-00903-2

- Fessl, A., Wesiak, G., Rivera-Pelayo, V., Feyertag, S., & Pammer, V. (2015, September 15–18). In-app reflection guidance for workplace learning. In G. Conole, T. Klobucar, C. Rensing, J. Konert, & É. Lavoué (Eds.), Design for Teaching and Learning in a Networked World: 10th European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning, EC-TEL 2015. (pp. 85–99). Springer International Publishing.

- Fong, R. W., Lee, J. C., Chang, C., Zhang, Z., Ngai, A. C., & Lim, C. P. (2014). Digital teaching portfolio in higher education: Examining colleagues’ perceptions to inform implementation strategies. The Internet and Higher Education, 20, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.06.003

- Garrett, B. M., & Jackson, C. (2006). A mobile clinical e-portfolio for nursing and medical students, using wireless personal digital assistants (PDAs). Nurse Education in Practice, 6(6), 339–346.

- Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606–633. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100

- Greenhow, C., Campbell, D., Galvin, S., & Askari, E. (2018). Social media in teacher professional development: A literature review. In E. Langran & J. Borup (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education International Conference 2018 (pp. 2256–2264). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

- Harun, R. N. S. R., Hanif, M. H., & Choo, G. S. (2021). The pedagogical affordances of e-portfolio in learning how to teach: A systematic review. Studies in English Language and Education, 8(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.24815/siele.v8i1.17876

- Hricko, M. (2017). Personal Learning Environments. In T. Kidd & M. L. R. (Eds.), Handbook of research on instructional systems and educational technology (pp. 236–248). IGI Global.

- Karsenti, T., Dumouchel, G., & Collin, S. (2014). The eportfolio as support for the professional development of preservice teachers: A theoretical and practical overview. International Journal OF Computers & Technology, 12(5), 3486–3495. https://doi.org/10.24297/ijct.v12i5.2919

- Klampfer, A., & Koehler, T. (2013). E-portfolios @ teacher training: An evaluation of technological and motivational factors. In Proceedings of the Iadis International Conference E-Learning 2013. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED562338

- Könings, K. D., van Berlo, J., Koopmans, R., Hoogland, H., Spanjers, I. A. E., ten Haaf, J. A., van der Vleuten, C. P. M., & van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (2016). Using a smartphone app and coaching group sessions to promote residents’ reflection in the workplace. Academic Medicine, 91(3), 365–370.

- Kori, K., Pedaste, M., Leijen, Ä., & Mäeots, M. (2014). Supporting reflection in technology-enhanced learning. Educational Research Review, 11, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.11.003

- Korthagen, F. A. J., Loughran, J., & Russell, T. (2006). Developing fundamental principles for teacher education programs and practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(8), 1020–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.022

- Le, Q. (2012). E-Portfolio for enhancing graduate research supervision. Quality Assurance in Education, 20(1), 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684881211198248

- Leinonen, T., Keune, A., Veermans, M., & Toikkanen, T. (2016). Mobile apps for reflection in learning: A design research in K-12 education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(1), 184–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12224

- Lorenzo, G., & Ittelson, J. (2005). An overview of e-portfolios. Educause Learning Initiative, 1(1), 1–27.

- Mauroux, L., Könings, K. D., Zufferey, J. D., & Gurtner, J.-L. (2014). Mobile and online learning journal: Effects on apprentices’ reflection in vocational education and training. Vocations and Learning, 7(2), 215–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-014-9113-0

- McNicol, S., Lewin, C., Keune, A., & Toikkanen, T. (2014). Facilitating student reflection through digital technologies in the iTEC project: Pedagogically-led change in the classroom. In P. Zaphiris & A. Ioannou (Eds.), Learning and collaboration technologies. technology-rich environments for learning and collaboration. LCT 2014. Lecture notes in computer science (Vol. 8524, pp. 297–308). Springer.

- Michos, K., Cantieni, A., Schmid, R., Müller, L., & Petko, D. (2022). Examining the relationship between internship experiences, teaching enthusiasm, and teacher self-efficacy when using a mobile portfolio app. Teaching and Teacher Education, 109, 103570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103570

- Mobarhan, R., Rahman, A. A., & Majidi, M. (2014). Electronic portfolios acceptance and use in higher educations: S systematic review. Information Systems Frontiers, 4, 11–21.

- Oner, D., & Adadan, E. (2011). Use of web-based portfolios as tools for reflection in preservice teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(5), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487111416123

- Petko, D., Schmid, R., Müller, L., & Hielscher, M. (2019). Metapholio: A Mobile App for Supporting Collaborative Note Taking and Reflection in Teacher Education. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 24(4), 699–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-019-09398-6

- Petko, D D. (2011). Writing Learning Journals with Weblogs: Didactic Principles and Technical Developments in the www.learninglog.org Open Source Project. In T. Bastiaens & Ebner (Eds.), Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2011 (pp. 2267–2271). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

- Petko, D., Egger, N., & Cantieni, A. (2017). Weblogs in Teacher Education Internships: Promoting Reflection and Self-Efficacy While Reducing Stress?. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 33(2), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2017.1280434

- Prestridge, S. (2019). Categorising teachers’ use of social media for their professional learning: A self-generating professional learning paradigm. Computers & Education, 129, 143–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.11.003

- Quek, C. L. (2009). In-service teachers’ experiential learning in a weblog-based environment. International Journal of Continuing Engineering Education and Life-Long Learning, 19(2/3), 126–140. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJCEELL.2009.025023

- Renner, B., Kimmerle, J., Cavael, D., Ziegler, V., Reinmann, L., & Cress, U. (2014). Web-based apps for reflection: A longitudinal study with hospital staff. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(3), e85. http://www.jmir.org/2014/3/e85/ https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3040

- Renner, B., Prilla, M., Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (2016). Effects of prompting in reflective learning tools: Findings from experimental field, lab, and online studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 820. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00820

- Roberts, P., Maor, D., & Herrington, J. (2016). ePortfolio-based learning environments: Recommendations for effective scaffolding of reflective thinking in higher education. Journal of Educational Technology and Society, 19(4), 22–33.

- Robertson, J. (2011). The educational affordances of blogs for self-directed learning. Computers & Education, 57(2), 1628–1644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.03.003

- Scherer, R., Siddiq, F., & Tondeur, J. (2020). All the same or different? Revisiting measures of teachers’ technology acceptance. Computers & Education, 143, 103656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103656

- Schneider, M., & Preckel, F. (2017). Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 143(6), 565–600.

- Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. Jossey-Bass.

- Seidel, T., Stürmer, K., Blomberg, G., Kobarg, M., & Schwindt, K. (2011). Teacher learning from analysis of videotaped classroom situations: Does it make a difference whether teachers observe their own teaching or that of others? Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(2), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.009

- Shroff, R. H., Trent, J., & Ng, E. M. W. (2013). Using e-portfolios in a field experience placement: Examining student-teachers’ attitudes towards learning in relationship to personal value, control and responsibility. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 29(2), 143–160. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.51

- Star, J. R., & Strickland, S. K. (2008). Learning to observe: Using video to improve preservice mathematics teachers’ ability to notice. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 11(2), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-007-9063-7

- Stefani, L., Mason, R., & Pegler, C. (2007). The educational potential of e-portfolios: Supporting personal development and reflective learning. Routledge.

- Strudler, N., & Wetzel, K. (2005). The diffusion of electronic portfolios in teacher education: Issues of initiation and implementation. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 37(4), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2005.10782446

- Tang, Y., & Hew, K. F. (2017). Is mobile instant messaging (MIM) useful in education? Examining its technological, pedagogical, and social affordances. Educational Research Review, 21, 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.05.001

- Tess, P. A. (2013). The role of social media in higher education classes (real and virtual)–A literature review. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(5), A60–A68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.032

- Tur, G., & Marin, V. I. (2013). Student teachers’ attitude towards eportfolios and technology in education. In F. J. García-Peñalvo (Ed.), Conference Proceedings of the First International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality (TEEM’13), Salamanca, Spain (pp. 435–439). ACM.

- Tur, G., & Urbina, S. (2014). Blogs as eportfolio platforms in teacher education: affordances and limitations derived from student teachers’ perceptions and performance on their eportfolios. Digital Education Review, 26, 1–23.

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/41410412

- Williams, M. D., Rana, N. P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2015). The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): A literature review. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 28(3), 443–488. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-09-2014-0088

- Zeichner, K. M. (2010). Rethinking the connections between campus courses and field experiences in college-and university-based teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109347671

- Zeichner, K. M., & Liu, K. Y. (2010). A critical analysis of reflection as a goal for teacher education. In N. Lyons (Ed.), Handbook of reflection and reflective inquiry. Mapping a way of knowing for professional reflective inquiry (pp. 67–84). Springer.

- Zubizarreta, J. (2009). The learning portfolio: Reflective practice for improving student learning. Jossey Bass/Wiley.