?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Over the past few years, equity-diversity-inclusion (EDI) requirements have proliferated in higher learning institutions. What impact have they had on students? This paper leverages a unique opportunity to evaluate the effect of an EDI requirement at a large public university: taught by the same instructor over the course of four quarters in three years, the course administered short anonymous surveys to students at the beginning and at the end of each term. These surveys measured student political attitudes such as preferences toward refugee admissions and affirmative action. Repeated surveys and repeated quarters allow us to evaluate changes in student attitudes during each quarter and averaged over three years. Results indicate an increase in inclusionary attitudes driven largely by students at the lowest baseline levels. Further analyses allow us to rule out social desirability bias, and suggest one possible mechanism: participation in small-group peer discussions.

Introduction

Over the past few years, EDI requirements have proliferated among institutions of higher learning in the United States. According to the US News and World Report, 38% of the country’s top 53 colleges and universities now include an EDI requirement (SI-E). Underlying these initiatives is the belief that greater racial awareness and tolerance can be fostered via courses that address some aspect of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the United States. Whether such an initiative succeeds is an empirical question. Recent findings show a positive effect of a ninth grade Ethnic studies course on educational attainment and attendance (Bonilla, Dee, and Penner Citation2021). However, high school civic education courses – including ethnic studies – do not appear to impact long-term political engagement (Weinschenk and Dawes Citation2022). At the university level, though, the evidence base is more ambiguous. Recent meta-analyses indicate an inclusionary effect, conditional on specific characteristics of the program (Denson et al. Citation2020; Engberg Citation2004). Yet some of the same researchers have also found an even mix of positive, non-significant, and even negative results (Denson and Bowman Citation2017).

One reason for this ambiguity is that the outcomes used to assess the effectiveness of diversity instruction are themselves diverse, focusing on behavioral, cognitive, or affective measures of inclusion. Another reason may be the variety of diversity education courses. Differences in instructors, time of year, and geographical location create noise that make it challenging to detect an effect.

A more serious challenge is that existing studies are limited by data structures. Many use longitudinal data from prominent student surveys such as UCLA’s Cooperative Institutional Research Program (Jayakumar Citation2008), which collects information from students at a variety of institutions at the beginning and end of their undergraduate careers. The longitudinal structure of the data allows researchers to speak to the cumulative effect of the university experience, but not to the isolated effect of any one class. In fact, this approach does not even allow researchers to adjudicate between the effects of university instruction and the university experience more generally. Other studies test the effect of one particular class, implemented at single slices in time (Denson et al. Citation2020). These analyze attitudinal changes for a single sample of students who self-selected into a diversity course, allowing for a more precise analysis of the effect at the expense of generalizability and causal identification.

As a result, the extant literature reflects a lack of consensus with regard to if and how university EDI courses shape student attitudes toward diversity. We need more studies that can separate out the effect of the university experience more generally from that of actual exposure to EDI courses. Indeed, as academia begins to grapple with discrimination and bias within its own walls (e.g. Brown and Montoya Citation2020), universities are reforming their curricula as if EDI instruction worked: does it?

We conduct a systematic test of the effects of a diversity course by constructing a unique data source that avoids many pitfalls of previous EDI program analyses. Ours is an analysis of more than 700 students enrolled in an EDI course over four terms from 2016 to 2018 at a large public university. It was taught by the same instructor across multiple quarters and years, with panel data that allows for the identification of within-student change. We take several steps to satisfy our identification assumptions and hold constant important sources of selection. First, we preregistered our hypotheses at OSF (https://osf.io/yxv9j/?view_only=e33ed6e1d3d14e4d8f32d9df5ddfc269) before analyzing the data. Second, we leveraged both over-time and within-student variation in attitudes. Third, we addressed social desirability bias via embedded experiments and analysis of open-ended questions and University-administered course evaluations. Fourth, the course is taught by the same instructor and is one of only several courses that satisfy a general EDI requirement, alleviating potential student sorting over course types, instructors and course timing.

Our results are three-fold. First, our analysis shows a positive average treatment effect of 0.54 standard deviations of taking the EDI course on an index (0–1) of inclusionary attitudes. Second, this increase is driven by students with low baseline levels of inclusion at the beginning of the quarter. Finally, this effect seems to operate at least in part via participation in small-group peer discussions.

Our study contributes to the literature on political attitude formation, particularly as it relates to issues of diversity and multiculturalism. Studies reveal a variety of factors that can alter sociopolitical attitudes (Broockman and Kalla Citation2016; Pérez, Deichert, and Engelhardt Citation2019), but the literature still lacks consensus regarding which strategies consistently and durably reduce prejudice (Paluck and Green Citation2009). Our study shows that a targeted curriculum can serve as a viable tool for promoting inclusive political attitudes.

Finally, our study adds to the public discourse on the value of diversity instruction. As universities have revamped their required curriculum to include EDI courses, many state governments have introduced legislation that prohibits diversity instruction in public institutions (Ray and Gibbons Citation2021). Politicians advocating for these legislative bans argue that these programs breed division and discontent. Our findings demonstrate that this is not true.

What might we expect from an EDI requirement?

The stated objectives of university EDI courses represent a best case scenario: assuming these courses do what they intend to do, students should become more tolerant and accepting of diversity (SI-E). Research often reveals more complicated results. We identified and pre-registeredFootnote1 three possible effects of an EDI requirement in a university setting: the intended effect, a backlash effect, or a polarizing effect.

H1: The intended effect

First, an EDI course could increase inclusionary attitudes via new information that dispels stereotypes: ignorance is assumed to be one of the most fundamental sources of prejudice (Stephan and Stephan Citation1984). Exposure to new information about diversity can change these attitudes (Link and Oldendick Citation1996); both observational (Wham, Barnhart, and Cook Citation1996) and experimental (Cameron and Rutland Citation2006) studies show that exposing students to information about marginalized populations increases their tolerance and understanding for those groups.

Second, the course could promote inclusionary attitudes via interactions with others (Allport Citation1954). A class environment in which small-group discussions bring diverse viewpoints together could foster perspective-taking or create pro-diversity social norms, both of which have been shown to reduce prejudice and increase tolerance (Simonovits, Kedzi, and Kardos Citation2018).

H2: The backlash effect

Empirical findings support these theoretical predictions: Individuals participating in mandatory workplace diversity programs often express increased resistance to diversity (Kalev, Dobbin, and Kelly Citation2006). Moreover, studies show that contact with and proximity to minoritized groups leads white Americans to express more negative feelings toward those groups (Tolbert and Hero Citation2001).

H3: The polarizing effect

Empirical strategy

To measure the effect of EDI instruction on student attitudes, we administered multiple surveys to undergraduate students enrolled in a university-approved EDI course titled “Politics of Multiculturalism” over the course of four quarters.Footnote2 The course lasted ten weeks and exposed students to the ways in which liberal democracies address existing and new forms of diversity (see SI-K for a sample syllabus). From 2016 to 2018, the course was taught four times by the same instructor to a total of approximately 700 students.Footnote3,Footnote4,Footnote5 Surveys were offered as take home assignments worth 10% of the students’ overall grade. Students could opt out by completing a short writing assignment, but an overwhelming majority of students elected to take the survey. Survey responses were anonymized and survey administration and data analysis were conducted by graduate teaching assistants, ensuring the instructor was never exposed to raw survey data.

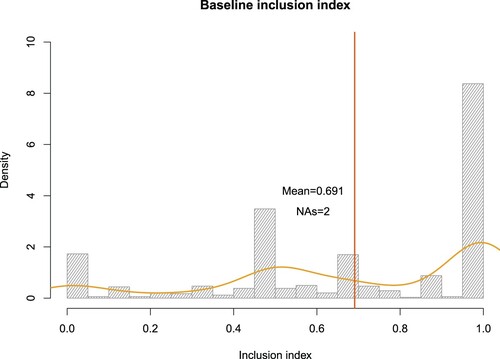

The primary outcome used to measure the effect of the course is an inclusion index, which was constructed using responses from four survey questions that measure student attitudes on a variety of course topics related to diversity, equity and inclusion. Responses to each of these four questions were equally weighted and scaled so that each student had inclusion index scores ranging from 0 - 1, with scores closer to one indicating higher levels of inclusionary attitudes. The mean baseline inclusion score across the entire sample was .691, with about a quarter of the sample in the lowest tercile ().

Our identification strategy relies both on within-student and across-student variation in inclusion index scores.

(1)

(1) where ΔInclusion Indexi is student i’s difference (endline-baseline) in inclusion index and Xi are controls for age, gender, party, race, and quarter fixed effects. τ relates to our estimand of interest, the treatment effect of the course.Footnote6 For this specification to plausibly capture the average treatment effect of the course on inclusionary attitudes, we assume that, conditional on observable confounders for which we account here, there are no omitted variables.

Selection into this class was not randomized – undergraduates across majors were permitted to enroll. As a result, the course may have attracted certain types of students, limiting the external validity of our findings. Still, the distribution of student majors and racial identities over the course of the study reveals that students from a wide variety of backgrounds and interests enrolled (SI-A).Footnote7 Additionally, because the class is one of only a handful of university courses that satisfied the university’s EDI requirement for graduation at the time, the selection bias into the course is likely less severe than it would be were the course offered as an elective.

Results

Evaluating the effect of the EDI course

displays our main result. The estimate for the intercept (treatment effect of the course) is positive and significant: on average students became more inclusive as a result of taking the class. This is consistent with H1 (intended effect) over H2 (backlash effect).

Table 1. The effect of an EDI requirement.

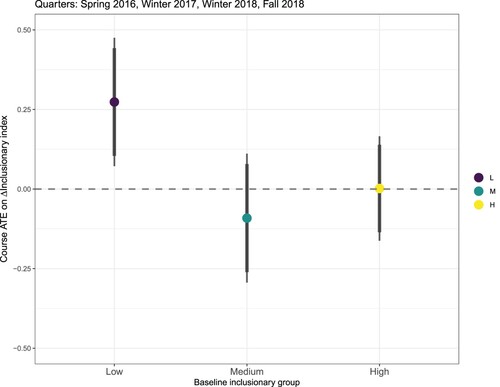

Is the course effect conditional on baseline attitudes (H3)? We split the sample into terciles based on baseline inclusionary index scores, and illustrate sub-group effects in . We find a positive effect of 0.25 (0.83 standard deviations) for Low baseline students only, lending partial support to H3. The differential effect is convergent rather than polarizing.

Probing the mechanisms

Our main finding suggests that the class had a positive effect on student inclusionary attitudes, driven by students in the lowest tercile of baseline inclusion. In our PAP, we hypothesized that inclusionary attitudes could be fostered through increased knowledge or increased contact with outgroups. We test these mechanisms here.

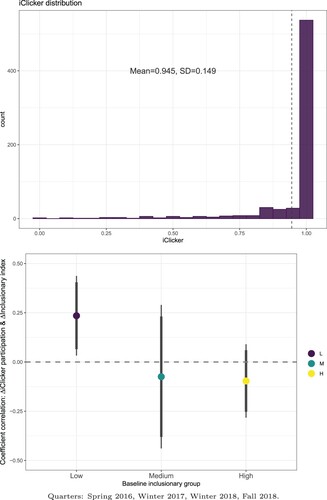

First, the class may increase inclusionary attitudes via outgroup contact during small-group discussions, which may have fostered perspective-taking and/or the adoption of pro-diversity norms. As part of normal class instruction, the course integrated iClicker technology to administer quick in-class anonymous polls to spur small-group peer discussion on class debates. In addition, iClicker responses were recorded and used as a class participation score that factored into the overall grade. We use student iClicker scores to capture engagement in small-group discussion throughout the course. displays the distribution of iClicker scores of students in our sample (left) and the correlation coefficient between iClicker score and changes in inclusionary attitudes, broken down by baseline inclusion group (right).

Figure 3. iClicker distribution and correlation with change in inclusionary index by baseline inclusion.

There is a significant correlation between iClicker scores and changes in inclusionary attitudes for Low baseline students only: among this group, those with higher iClicker scores show a significantly greater increase in their inclusion index. Our test remains correlational but is consistent with other empirical findings that speak to the importance of interpersonal interaction in fostering greater perspective-taking and norm transmission.

Alternatively, we hypothesized that increases in inclusionary attitudes may be driven by exposure to new information via class material. Our analyses, presented in detail in SI-I, reveal that across all three baseline groups, there is no significant correlation between changes in knowledge and changes in inclusion.

Implications and limitations

We leverage a panel data of students at a large public university over four terms and three years to evaluate the effect of an EDI requirement. We find that EDI increases student inclusionary attitudes, and that this change is driven by those with the lowest baseline levels of inclusion. We further find evidence that this occurs via students’ participation in small peer-group discussions. Here, we address two possible limitations of our study and discuss the implications of our findings.

Experimental studies with randomized treatment assignment remain the gold standard for causal inference in our discipline. In our study, for practical reasons, all students were “assigned to treatment”: this is not a laboratory setting but a real-world college environment. Our identification strategy, therefore, rests on the multiple-panel nature of our data: by evaluating effects within students and over quarters, ours is a conservative approach that still generalizes over three years.

Our results are vulnerable to social desirability bias if students were taught to answer surveys in “politically correct” ways. We address this threat to our interpretation in two ways. First, we use the results of a list experiment (Imai Citation2011) embedded in the Fall and Winter 2018 surveys to show that social desirability did not increase over the quarter. We randomly assigned students to respond to a question about their views on refugee screening policies either directly or via a list experiment. Comparing the estimated proportion of students who express support for the policy in the direct question vs. the list experiment, we find that the difference is not statistically distinguishable from zero at conventional confidence levels and does not increase during the quarter (see SI-D). Second, we investigate signs of self-censorship via automated and manual text analysis of open-ended questions in our survey and an independent class evaluation administered by the university, and by investigating whether students were less likely to reveal their party ID at the end of the quarter than at the beginning of the quarter. Our analysis, presented in SI-G, shows no evidence of self-censorship.

Our findings speak not only to the research on the effectiveness of diversity courses in school and workplace settings but also to the role of education in shaping sociopolitical attitudes. We address challenges to causal inference and generalizability with panel data that spans four quarters and three years. Whereas other EDI course evaluations often cannot account for variation in the type of EDI courses students take, we collected data in a setting where all students received the same course content from the same instructor. We show that an EDI course can generate robust positive effects with different student populations and across different time periods.

Like other diversity interventions, our study is limited in its ability to confidently draw broad claims about the effectiveness of these programs in other contexts. Nevertheless, given that this study was conducted at a large, public institution with a diverse student body, our results are still instructive for academic institutions or large organizations looking to introduce or refine EDI courses to increase inclusion.

EDI_PGI_SI.pdf

Download PDF (1.4 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We pre-registered a pre-analysis plan at OSF on May 29, 2020 (SI-J) before data analysis began.

2 These surveys were certified as exempt by the UC San Diego Institutional Review Board.

3 In SI-H.

4 In Fall 2018, the baseline was administered prior to quarter’s start, allowing us to alleviate concerns that students are selecting into the course by the time we capture their baseline attitudes (SI-F).

5 In SI-M, we analyze the risk of sign and magnitude errors given that we are under-powered. We find low levels of over-estimation and a very low risk of obtaining the wrong sign.

6 We do not cluster the standard errors at the student level because our outcome is a difference in student attitudes measured at two points in time.

7 SI-B offers weighted analyses by race/major; results are substantively unchanged.

References

- Allport, Gordon. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Bonilla, Sade, Thomas S. Dee, and Emily K. Penner. 2021. “Ethnic Studies Increases Longer-run Academic Engagement and Attainment.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (37). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2026386118.

- Broockman, D., and J. Kalla. 2016. “Durably Reducing Transphobia: A Field Experiment on Door-to-Door Canvassing.” Science 352 (6282): 220–224. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad9713.

- Brown, Nadia E, and Celeste Montoya. 2020. “Intersectional mentorship: A model for em- powerment and transformation.” PS: Political Science & Politics 53 (4): 784–787. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520000463.

- Cameron, L., and A. Rutland. 2006. “Extended Contact Through Story Reading in School: Reducing Children’s Prejudice Toward the Disabled.” Journal of Social Issues 62 (3): 469–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2006.00469.x.

- Chang, E. H., K. L. Milkman, D. M. Gromet, R. W. Rebele, C. Massey, A. L. Duckworth, and A. M. Grant. 2019. “The Mixed Effects of Online Diversity Training.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (16): 7778–7783. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1816076116.

- Denson, N., and N. A. Bowman. 2017. “Do Diversity Courses Make a Difference? A Critical Examination of College Diversity Coursework and Student Outcomes.” In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, edited by Michael B. Paulsen, 35–84. Cham: Springer.

- Denson, Nida, Nicholas A. Bowman, Georgia Ovenden, K. C. Culver, and Joshua M. Holmes. 2020. “Do Diversity Courses Improve College Student Outcomes? A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 14 (4): 554–556. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000189.

- Engberg, Mark E. 2004. “Improving intergroup relations in higher education: A critical ex- amination of the influence of educational interventions on racial bias.” Review of Educational Research 74 (4): 473–524. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074004473.

- Galinsky, A. D., and G. B. Moskowitz. 2000. “Perspective-taking: decreasing stereotype ex- pression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78 (4): 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.708.

- Imai, Kosuke. 2011, June. “Multivariate Regression Analysis for the Item Count Technique.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 106 (494): 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2011.ap10415.

- Jayakumar, Uma. 2008. “Can Higher Education Meet the Needs of an Increasingly Diverse and Global Society? Campus Diversity and Cross-Cultural Workforce Competencies.” Harvard Educational Review 78 (4): 615–651. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.78.4.b60031p350276699.

- Kalev, A., F. Dobbin, and E. Kelly. 2006. “Best Practices or Best Guesses? Assessing the Efficacy of Corporate Affirmative Action and Diversity Policies.” American Sociological Review 71 (4): 589–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100404.

- Link, Michael W, and Robert W Oldendick. 1996. “Social Construction and White Attitudes Toward Equal Opportunity and Multiculturalism.” The Journal of Politics 58 (1): 149–168. https://doi.org/10.2307/2960353.

- Paluck, E. L., and D. P. Green. 2009. “Prejudice Reduction: What Works? a Review and Assessment of Research and Practice.” Annual Review of Psychology 60: 339–367. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163607.

- Pérez, Efr´en O, Maggie Deichert, and Andrew M Engelhardt. 2019. “E Pluribus Unum? how Ethnic and National Identity Motivate Individual Reactions to a Political Ideal.” The Journal of Politics 81 (4): 1420–1433. https://doi.org/10.1086/704596.

- Ray, Rashawn, and Alexandra Gibbons. 2021. Why are States Banning Critical Race Theory? Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2021/07/02/why-are-states-banning-critical-race-theory/.

- Simonovits, G., G. Kedzi, and P. Kardos. 2018. “Seeing the World Through the Other’s eye: An Online Intervention Reducing Ethnic Prejudice.” American Political Science Review 112 (1): 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000478.

- Stephan, Walter G, and Cookie White Stephan. 1984. “The role of ignorance in intergroup relations.” Groups in Contact: The Psychology of Desegregation, 229–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-497780-8.50017-6.

- Tajfel, H., and J. C. Turner. 1986. “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior.” In Psychology of Intergroup Relation, edited by S. Worchel, and W. G. Austin, 7–24. Chicago: Hall Publishers.

- Tolbert, C. J., and R. E. Hero. 2001. “Dealing with Diversity: Racial/Ethnic Context and Social Policy Change.” Political Research Quarterly 54 (3): 571–604. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290105400305.

- Weinschenk, Aaron C, and Christopher T Dawes. 2022. “Civic Education in High School and Voter Turnout in Adulthood.” British Journal of Political Science 52 (2): 934–948. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000435.

- Wham, M. A., J. Barnhart, and G. Cook. 1996. “Enhancing Multicultural Awareness Through the Storybook Reading Experience.” Journal of Research & Development in Education 301: 1–9.