ABSTRACT

The juxtaposition of the 2016 and 2020 elections reveals that despite articulating prejudiced positions as a candidate and then as president, Donald Trump broadened his support among minorities. Particularly perplexing is the fact that support for Trump grew among African Americans. We propose a counterintuitive explanation: racial resentment among Blacks accounted for Trump’s increased support. Our highly robust results motivate a reevaluation of standard understandings of the role of race in American politics writ large and in American elections more specifically. Blacks show considerably more variance in voting behavior than what would be expected given accounts focused on their linked fate; Blacks behave not just in the mold of Stacey Abrams, but more than commonly thought also in the mold of Clarence Thomas. As racially resentful Blacks reside disproportionately in certain swing states, our account portrays Blacks as citizens with political agency, who may be pivotal in determining election outcomes, sometimes in unexpected ways.

Justice Clarence Thomas

I agree with Ralph Ellison when he asked, perhaps rhetorically, why is it that so many of those who would tell us the meaning of Negro, of Negro life, never bothered to learn how varied it really is. That is particularly true of many Whites who have elevated condescension to an art form by advancing a monolithic view of Blacks in much the same way that the mythic, disgusting image of the lazy, dumb Black was advanced by open, rather than disguised, bigots. “Speech to the National Bar Association” (1998)

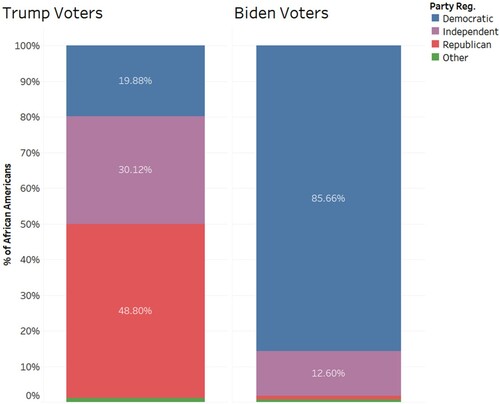

Black support for Trump was not marginal. According to Edison Research, Trump’s support among African Americans in 2020 amounted to at least 12%. This was 4% higher than in 2016. Though some estimations indicated a smaller change in Black support for Trump (Ostfield and Garcia Citation2020), the unpacking of these trends reveals surprising patterns. No less than a third of all Black men living in the Midwest voted for Trump (Tidmore Citation2020). It was in the home state of George Floyd—Minnesota, the origin of the 2020 nationwide protest movement against police brutality—where Trump won 30% of the Black male vote (Dent Citation2020). Trump was able to concurrently attract young Black voters and those already registered as Democrats. According to UCLA Nationscape’s polling, support for Trump among young Black voters (18–44) more than doubled, from about 10% in 2016 to 21% in 2020 (Skelley and Wiederkehr Citation2020). Furthermore, shows that about 20% of Trump Black voters were registered Democrats, compared to nearly zero Republican registrants among Black voters for Biden.

Figure 1. Party Registration Among African American Voters in 2020.Footnote5

Actual voting data confirm those trends.Footnote1 In Minneapolis MN, Trump increased his support in three of the city’s neighborhoods with the largest share of African Americans. In Hawthorne, the Black vote for Trump increased by 4.2%, in Jordan by 5.8%, and in Near North by 1.2%. In Milwaukee WI, five of its most populated neighborhoods by African Americans—at least 90% of the population—showed an increase (however modest) in support for Trump: in Arlington Heights a 1.5% increase, in Franklin Heights 0.5%, in Garden Homes 1%, in Rufus King 1.6%, and 3% in Triangle North. Other areas of the city with substantial Black communities showed bigger gains. In Walnut Hill, for instance, with more than 50% African Americans, support for Trump increased by 21%. In Florida’s most populous city with a majority African American population—Miami Gardens—which is also home to the largest percentage of African Americans (66.97%) of any city in the state,Footnote2 Trump increased his support by at least 10%.

Thus, running as incumbent in 2020, Trump enjoyed meaningfully broader support among Black voters in comparison to his performance in 2016 (Collins Citation2020). Against all odds, and while running as a Republican, Trump was able to increase his support among African American voters, who normally tend to vote overwhelmingly Democrat (Rigueur Citation2014). Political behavior among African Americans is typically explained by linked fate, (dis)trust in government, political efficacy, group membership, and church attendance (Chong and Rogers Citation2005; Simien Citation2013; Wolak Citation2018). Yet, understanding African Americans as a homogenous group—which is antithetical to how White Americans are theorized—misrepresents Blacks. Indeed, Blacks are more heterogenous than typically thought (Lewis and Nelson Citation2022), even on issues where such variance is not expected, like racial resentment. Like Kam and Burge (Citation2018), we identify racial resentment as key to analyzing the behavior not just of Whites but also of Black voters. Utilizing the canonical battery of racial resentment indicators while controlling for relevant variables, such as perceptions of the economy and ideology, we find that as a constituency, African Americans are not as cohesive as typically portrayed. This key argument goes beyond works highlighting ideological variation among African Americans (e.g., Dawson Citation1994; McClain et al. Citation2009). As important as ideology is, we find racial resentment to be a key driver with an even stronger effect on Black voters, and particularly in swing states during the Trump era. Thus, the variance we find on a variable, where prima facie we would expect unanimity, is also politically consequential.

Because of their strategic location in key battleground states, the group of racially resentful Black voters likely influenced the outcome of the 2020 elections. Florida and Georgia are a case in point. In Florida, which Trump carried impressively, there was a substantial presence of highly racially resentful Black voters. Conversely, Trump lost Georgia to Biden after easily carrying the state four years earlier. The share of a highly racially resentful segment among the Black electorate in Georgia was considerably smaller than in its neighboring state to the south. African Americans with racially resentful attitudes, especially in those swing states where Black votes are crucial—like Florida, Georgia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, North Carolina, Wisconsin, and Michigan—could determine election outcomes. Despite their significant political sway and the new light they shed on extant theoretical accounts, racially resentful Blacks are a constituency largely overlooked in political science.

We build on a growing body of interdisciplinary literature highlighting the political agency of African American voters (e.g., Edwards Citation2022; Gaines Citation2021; Vaughan Citation2021). This is particularly important considering recent developments, the most salient of which have been Stacey Abrams’ successful mobilization campaigns in Georgia in 2018 and 2020. In lieu of more passive portrayals of African Americans associated with discrimination, the criminal justice system, or economic inequality, the new narrative inspired by Abrams’ successes underlines the significance, importance, and influence of African Americans as citizens, potentially pivotal for determining election outcomes. Yet, the perspective of African Americans as proactive does not mean that they necessarily espouse a liberal ideology when showing political agency. There is a significant number of Blacks who, instead of fitting into the mold of Stacy Abrams, are closer to that of Clarence Thomas, as reflected in their levels of racial resentment.

Using data from the 2020 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), we examine the effect of racial resentment. Controlling for the effects of perceptions of the economy and ideology, we find that racial resentment had a significant and meaningfully large effect on the votes of people of color. In addition to nationwide analyses, we also examine the implications for election outcomes in swing states, focusing on Florida, Georgia, and Wisconsin. In conclusion, we discuss the political and theoretical implications of this diversity within the Black community and examine whether it warrants a reevaluation of our understanding of the role in American politics of race, racial resentment, and racial minorities.

Black group identity and linked fate

The unified partisan affiliation of African Americans with the Democratic Party has long been an accepted premise, stemming from the identity formation process of this racial group (Dawson Citation1994). The way Blacks perceive their racial group’s interests shapes their political positions and their actions as individuals. When an individual pertaining to a group evaluates social perceptions and attitudes toward their group, on the part of other groups and the general public, a sense of linked fate evolves (Merseth Citation2018; Laird Citation2019). Negative images, stigmas, and stereotypes about Blacks summon collective action which engenders a sense of linked fate (Shaw, Foster, and Combs Citation2019). In a socially stratified competition between social groups for scarce resources—such as power, prestige, or wealth—one develops a sense of in-group favoritism and out-group antagonism. Intergroup competition boosts intragroup morale, unity, and collaboration (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979).

The political behavior of Black voters has, thus, been assumed to comprise both how individual Black voters perceived the circumstances of the Black community as a whole, and the way Black voters believed society viewed their racial group. Indeed, and despite some empirical and theoretical shortcomings, linked fate proved to be a significant predictor of African American political behavior regarding racial and redistributive policies, partisanship, and electoral decision-making (McClain et al. Citation2009).

Structural reasoning provides the theoretical basis for linked fate. President Obama’s speech in the aftermath of the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin is an illustration: “When Trayvon Martin was first shot, I said that this could have been my son (…) Trayvon Martin could have been me thirty-five years ago.” In his speech, Obama described experiences that are unique to African Americans, such as “being followed when shopping in a department store” or “walking across the street and hearing the locks click on the doors of cars,” ending each example with the words “[this] happened to me too” (The White House). President Obama, as an African American individual, articulated the sentiment of linked fate. Blacks live with a sense of disdain and hostility on the part of the general public. Racial discrimination is the experience at the core of Black group identity, or “Blackness” (Lewis and Nelson Citation2022). However, there are reasons to question whether linked fate remains valid as a blanket account for all Blacks.

Racially resentful African Americans

A key question is whether it is acceptable to use racial resentment—originally designed to measure anti-Blackness among Whites—for Black political thinking. Arguing for the explanatory advantage of racial resentment over that of linked fate, Kam and Burge (Citation2018) list status theory, elite discourse, empirical trends, and similar substantive interpretations as four possible reasons to use that scale for Blacks as well.

Increasing heterogeneity among Blacks, in terms of demographics, education, and economic standing motivated this reevaluation of the linked fate concept (Capers and Smith Citation2016). If the vast majority of African Americans traditionally tended to espouse structural rationalizations such as racism and prejudice for their lack of success in achieving equality (Massey and Denton Citation1993; Pattillo-McCoy Citation1999)—as demonstrated in the speech by President Obama in the aftermath of the Trayvon Martin shooting—contemporary explanations African Americans use for inequality shift toward individual attributes (Kam and Burge Citation2018). This shift in reasoning may be related to less racially charged and more moderate sentiments expressed by prominent Black public figures in relevant matters (Tate Citation2010). In addition, there are age and cohort effects (Hunt Citation2007; Nunnally and Carter Citation2012).

The growing number of African Americans substituting structural for individualistic explanations of the experience of Blacks in America suggests corresponding adjustments in their sentiments regarding race relations. There is little reason to think that racial resentment would be an exception. Generally, and irrespective of racial identification, recent work has shown that racial effects on political behavior have grown stronger (Besco and Scott Matthews Citation2022; Lyle Citation2014; Thompson and Busby Citation2023). Racial attitudes are now the underpinning of partizanship and ideology in American politics (Tesler Citation2016). Racial resentment influences even ostensibly nonracial policy domains (Kinder and Dale-Riddle Citation2012).

Originally defined as a negative White sentiment toward African Americans that is predicated on the notion that African Americans fail to live up to classic individualistic norms of American society, Kinder and Sanders (Citation1996) define racial resentment as a blend of an anti-Black mindset intertwined with a sense of animosity and humiliation. Studies deployed the canonical battery of racial resentment indicators to explain the political behavior of White voters (Cepuran and Berry Citation2022; Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Citation2016). Trump’s upset victory in 2016 is one of the most recent manifestations of White racial resentment, signaling to many a White Roar that dumped hopes for a post-racial America after the election of the first African American president. Historically, salient White racial group identity, of which racial resentment is one component, has been associated with voting for Republicans. Some viewed the ascension of Ronald Reagan as the culmination of a White conservative backlash in the face of the Civil Rights Movement and other liberal landmarks of the 1970s (McAdam Citation2015). White racial politics were also weighty in George H.W. Bush’s 1988 presidential campaign when he repeatedly brought up the story of Willie Horton (Mendelberg Citation1997; White Citation2007).

Racial resentment was described as “symbolic racism” and “new racism,” due to its association with symbolic issues like bussing and affirmative action (Jacobson Citation1985). In that sense, racial resentment, like sexism, is a legitimizing ideology. It is comprised of stereotypical beliefs that deny systematic discrimination as the cause of inequality (Cassese, Barnes, and Branton Citation2015). In this context, being racially resentful Black sounds like an oxymoron. Racial resentment derives from White control over the power structures of society and institutions. Since African Americans have never been in such a position of control, it is theoretically impossible for them to use a legitimizing ideology for policies out of their command. Yet, because shared experiences shape consciousness toward a collective identity (Brown-Dean Citation2019), “when the necessary identity-shaping experiences are absent, affirmation with the political identity is also absent” (Lewis and Nelson Citation2022, 757).

People may self-identify as Black, based on their biology and visible traits, but their detachment from recurrent discriminatory experiences unique to Blacks, or from the acknowledgment of those experiences, concurrently implies their lack of Black sociopolitical identity. Indeed, as Kam and Burge’s (Citation2018) fourth point illustrates, Whites and Blacks show similar substantive interpretations of the racial resentment scale. Lewis and Nelson (Citation2022) deal with an akin trend they name “insulated Blackness”, which is the opposition of self-identified African Americans to pro-Black remedial policies and their disagreement with commonly held ideologies about the Black condition. Despite the theoretical thread between insulated Blackness and Black racial resentment, they differ in one central aspect. Whereas racial resentment infers disdain and negative feelings, insulated Blackness does not infer even disdain, as the opposition to Blackness is rooted in a lack of shared experiences.

In sum, the budding debates in the literature about African Americans’ intra-group opposition are demonstrative both of its existence and its consequentiality. Challenging concerns raised about its dwindling explanatory power for political judgment, deriving from a possible confluence of principled ideologies about the appropriate role of government and the battery’s indicators (Carmines, Sniderman, and Easter Citation2011; Huddy and Feldman Citation2009)—and in line with recent scholarship (Kam and Kinder Citation2012)—we show that racial resentment maintains a leading role in explaining political behavior in America. More importantly, we argue that this explanatory power is significant not only with regards to White political behavior but also among voters of color.

Members of subordinate groups tend to derogate the in-group and express positive attitudes toward the depriving out-group while internalizing a self-derogation of inferiority (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979). In addition, like their fellow Americans, the American Dream plays a key role in the socialization of African Americans. This, in turn, motivates their embrace of individualistic principles (Harris and McKenzie Citation2015). Age, socioeconomic status, and gender are only some of the attributes affecting Black attitudes toward their own group (Allen, Dawson, and Brown Citation1989; Wilson Citation1978). This suggests a potential for diversity in judgments related to race.

Trump’s 2020 failure in Georgia is a key example of the associated gender effect. Four years after Republicans winning the southern state with a decisive margin (>5%), Trump lost to Biden. Exit polls indicate better Trump performance among Black men compared to Black women (Nagesh Citation2020). Literature on intersectionality sheds light on this divergence. According to Cassese, Barnes, and Branton (Citation2015), women of color experience prejudice in a different manner than White women or men of color due to their double jeopardy. Black women and Latinas deal with “a cumulative discrimination that extends beyond racism or sexism alone because they simultaneously belong to a low-status gender group and a low-status racial/ethnic group” (Cassese, Barnes, and Branton Citation2015, 2). Still, where Blacks’ interests directly conflict with the interests of women, “Black women’s identification with women can mute their support for causes presented as favoring Blacks” (Gay and Tate Citation1998).

In light of Stacey Abrams’ two successful mobilization campaigns in the 2018 gubernatorial elections and in the 2020 presidential elections—which were intimately associated with gender issues (Rubin Citation2020)—we would expect gender to account for at least some of the apparent slide in support for Trump in Georgia, in particular among African Americans. Moreover, Abrams’ structural framework for the African American struggle—aimed to facilitate participation in elections and increase turnout through emphasizing obstacles unique to the Black community—corresponds strongly with traditional structural explanations for the African American struggle, which further demonstrates the intertwined effects of gender and race (Sommer Citation2013).

In sum, we contend that the dearth of scholarship on racial resentment and its political ramifications in the case of the African American community is misguided (Zigerell Citation2015). Accordingly, as in the case of White voters, we expect an effect of racial resentment on people of color. Accordingly, our first hypothesis is:

H1: Ceteris paribus, higher levels of racial resentment will have a positive relationship with the probability of voting for Trump among African American voters.

Other indicators

To accurately assess the effects of racial resentment, we also control for the effects of other relevant variables. Those are widely considered in the literature to be of key influence on voting: ideology, religiosity, sexism, and the perception of economic conditions. While they may be partly related to racial resentment, in addressing and evaluating each separately as well as side by side with racial resentment, we aim to capture Black political behavior more comprehensively and control for any possible alternative explanations. Put simply, we want to show that the effect of racial resentment on Black voting behavior remains significant and of meaningful size even when controlling for those alternative effects.

Ideology, religion, and sexism

Despite overwhelming support among African Americans for the Democratic Party, there are several unusual characteristics of the Black Democratic voter relative to the liberal landscape (Gay Citation2014). A vast majority of African Americans, 85% and 73% respectively, support restricting legal immigration (more than any other demographic group in the United States), and school choice. About one in two Blacks do not believe abortion is morally acceptable and oppose same-sex marriage, compared to less than a third among Whites (Friess Citation2022). More often than not, the political classification of African American voters is “conservative but not Republican” (Philpot Citation2017), or alternatively, Democrat but conservative.

In terms of their faith, Black Americans are more religious than the general public. According to the Pew Research Center, 97% of adult African Americans say they believe in God or a higher power, compared to 90% among all US adults, and 75% among them believe that opposing racism is essential to faith, compared to 68% in the American public. At the same time, findings show that many Black congregations foster a culture underlining the experiences and leadership of men rather than those of women. Indeed, Black Americans are much less likely to have heard sermons, lectures, or group discussions about discrimination against women or sexism than about racial discrimination. In addition, African Americans are much more likely to say their congregations strongly emphasize the role of men compared to women in supporting households financially, as well as serving as an example in Black communities (Mohamed et al. Citation2021; Sommer et al. Citation2023).

Black voters’ tendency to espouse more conservative positions on several key issues fits in with an important insight regarding the overlooked diversity among the Black constituency. Even if the underlying ideological mechanisms work differently among Blacks compared with Whites (Philpot Citation2017), both Blacks and Whites vary in terms of their voting behavior and in their evaluations of various policies (Tien, Nadeau, and Lewis-Beck Citation2012). Correspondingly, our second hypothesis is that just like for White voters:

H2: Conservatism will have a positive correlation with the probability of voting for Trump among African American voters.

Importantly, if ideology in itself were a sufficiently strong predictor for Black political behavior, the ambivalent “conservative but not Republican” classification would probably have little explanatory power. Accordingly, while we expect a positive relationship between conservatism and the probability of voting for Trump, we also take into account that a closer examination of ideology among African Americans and its relation to political choice and political identification may reveal more complex dynamics, as we further elaborate below. All the more so, considering the overriding prominence of religion within the African American community. regardless of partisanship, it is fair to assume that religion's explanatory power would be even weaker than that of ideology. To distinguish religiosity from ideology, we also test the specific effect of religion on the voting choice of African Americans, based on the conventional wisdom that it is associated with voting Republican:

H3: Religiosity will have a positive correlation with the probability of voting for Trump among Black voters.

Finally, because racial resentment and sexism are both “legitimizing ideologies” (Cassese, Barnes, and Branton Citation2015), it is also crucial to tease out racial resentment from sexism. Keeping in mind the gender divergence within the Black constituency identified in exit polls, and in light of biases favoring men in Black congregations, our fourth hypothesis is:

H4: A positive correlation between sexism and voting for Trump among Blacks.

Perceptions of the economy

Scholarship extensively examined the effect of economic conditions on vote choice, political preferences, and policy evaluations (Fiorina Citation1981; Fisher Citation2016; Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier Citation2000). Although economic matters are not the only consideration on voters’ minds, they are of chief importance. For instance, the Reagan and Clinton campaigns relied heavily on the issue. Reagan did so positively, through his It’s morning again in America campaign ad. Clinton did so negatively, using the slogan It’s the economy, stupid against the incumbent, Bush.

There are two axes according to which economic voting is measured. First, scholars draw a distinction between two different kinds of economic conditions: prospective and retrospective. Prospective economic conditions are evaluations of future economic performance, while retrospective economic conditions are evaluations of past economic performance (Fiorina Citation1981). In this article, we refer to retrospective economic voting.

A second distinction lies within the retrospective category: between egocentric and sociotropic voting. The former relates to those voters who focus on their own financial standing, favoring their personal or their family’s economic situation compared to that of the nation. The second prioritizes collective aspects of the economy (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier Citation2000). In this article, we examine retrospective voting through an index variable combining egocentric and sociotropic voting, measuring respondents’ opinions regarding their personal economic conditions, as well as collective economic circumstances.

Since Donald Trump assumed office in 2016, and through his 2020 presidential bid, many scholars identified relationships between economic conditions and voting for Trump. Unsurprisingly, as the Reagan and Clinton campaigns illustrate, negative perceptions of economic conditions were significantly associated with voting for Trump in 2016. This is in line with the notion that negative perceptions of economic conditions are associated with voting against the incumbent party (Brooks and Brady Citation1999), in this case, the Democrats. Along the same lines, positive perceptions of economic conditions were significantly associated with voting for Trump in 2020 (Buyuker et al. 2021).

Yet, this scholarship excluded Blacks as a group and instead focused on economic voting among the general population or among White voters only. But as Welch and Foster (Citation1992) indicate, the very political cohesiveness which may explain why scholars exclude Black voters from such studies—on the assumption that there is little to no effect on them, other than their commitment to the Democratic Party—is in fact consequential for Black economic voting. For example, data from the 1984 presidential elections recorded sociotropic economic voting among Blacks, both with respect to the nation’s economy and to the economic standing of their racial group (Welch and Foster Citation1992). Just like White voters, even if at different levels, Black voters share economic concerns which affect their electoral choices. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H5: More positive perceptions of the economy will correlate with the probability of voting for Trump among African Americans.

Methodology

Data from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) for the 2020 presidential elections were used to test our hypotheses. Administered by YouGov, this dataset consists of more than 50K responses from potential voters, gathered through a nationally stratified sample. Half of the questionnaire, administered to the entire pool of respondents, is focused on common content, disregarding ethnic, racial, or any other group affiliation. The other half is designated for team content. This half comprised questions relevant to certain respondents based on their group affiliation. A subset of 1K people answered this part of the questionnaire. In election years, the survey is carried out in two waves. Prior to the elections, respondents are given questions concerning their general political attitudes, various demographic factors, assessment of roll call voting choices, political information, and vote intentions. This first wave is two-thirds of the questionnaire and is performed from late September to late October. The post-election cycle makes the other third. Administered in November, it centers mostly on items related to the elections respondents had just voted in.Footnote3

For our dependent variables, we are interested in measuring support for Trump. Accordingly, we focus on two variables gauging voters’ presidential choices. The first asks respondents who indicated they voted early: “For which candidate for President of the United States did you vote?” The second poses a similar question to the vast majority of respondents who indicated they had voted on Election Day. Observations analyzed include only those respondents who supported either one of the two leading candidates, Trump and Biden.

As for our independent variable—racial resentment—we build on the classical scale Kinder and Sanders (Citation1996) introduced to measure symbolic racism, with revisions implemented by Stephen Ansolabehere, Brian Schaffner, and Sam Luks in the 2020 CCES. Accordingly, we estimate racial resentment as a sum of five questions, each measuring agreement with statements concerning race on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). These five statements are constituted of a “racially agreement” statement, and four “racially resentful” statements, per the 2020 CCES version of the scale, respectively: “White people in the U.S. have certain advantages because of the color of their skin,” “Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class,” “I resent when Whites deny the existence of racial discrimination,” “Whites get away with offenses that African Americans would never get away with,” and “Whites do not go to great lengths to understand the problems African Americans face.” The racial resentment scale ranges from 5 to 25. We define high levels of racial resentment as between 15 and 25. In the Online Appendix, we present sensitivity tests with high levels of racial resentment defined with other cutoff points (figures A.1. and A.2.), all yielding substantively indistinguishable results.

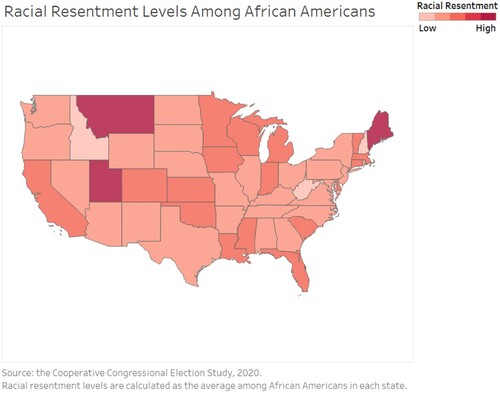

shows racial resentment levels among African Americans throughout the United States. Although the concentration of racially resentful African Americans in swing states is not monolithic, more racial resentment among African Americans is evidently correlated with greater electoral success for Trump, such as in Florida and Wisconsin, for example. Similarly low levels of racial resentment in Georgia and New York may account for some of the hurdles Trump faced in the Peach State.

Figure 2. Racial Resentment Levels Among African Americans.Footnote6

The second independent variable, Perception of Economic Situation (PES), measures how respondents perceive the state of the economy. It is composed of responses to two questions, on a scale from 1 (gotten much better) to 5 (worse): “Would you say that OVER THE PAST YEAR the nation’s economy has … ,” and “OVER THE PAST YEAR, has your household’s annual income … ?” The higher the score, the greater the discontent with the nation’s and its own economic conditions. The third predictor in the regression models is ideology. It estimates respondents’ ideology on a scale from 1 (very liberal) to 5 (very conservative).Footnote4 Religiosity is the fourth independent variable and is composed of the responses to three questions, asking respondents about their perceived importance of religion (“very important” to “not at all important”), church attendance (“more than once a week” to “never”), and frequency of prayer (“several times a day” to “never”). The higher the score on this battery of questions, the lower the importance of religion to the respondent. Finally, sexism is measured as the sum of two questions gauging agreement with statements concerning gender on a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree): “Women seek to gain power by getting control over men” and “Women are too easily offended.” The higher the score, the less sexist the respondent.

For robustness, models were estimated with each one of the main predictors coded once as continuous and then as discrete. Racial resentment was coded as a dummy that assigns a score of 1 (racially resentful) to respondents with scores higher than 10 on the continuous version of the variable, and 0 otherwise. PES was coded as a dummy that assigns a score of 1 (positive perceptions of economic conditions) to respondents with scores lower than 5 on the continuous version of the variable, and 0 otherwise. Ideology was also coded as a dummy that assigns a score of 1 (conservative) to respondents with scores higher than 3 on the continuous version of that variable, and 0 otherwise. In the body of this article, we report the results for models estimated with the continuous versions of the variables. Models estimated with the dichotomous versions of the variables are reported in the Online Appendix. There are no substantively meaningful differences between the dichotomous and the continuous versions.

Racially resentful black voters in swing states

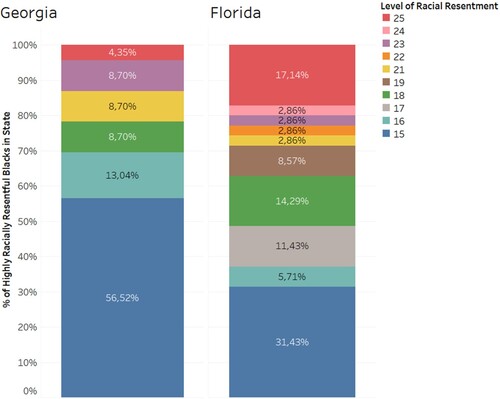

We first examine the effects of racially resentful African American voters in swing states. In 2020, both Florida and Georgia were battleground states. suggests that compared to their counterparts in Georgia, highly racially resentful Blacks in Florida are substantially more numerous. In addition, racially resentful Blacks in Florida present considerably higher levels of racial resentment compared to Blacks in Georgia. Among highly racially resentful Blacks in Georgia, the share of those who hold the lowest levels of racial resentment within this high racial resentment range is substantially bigger than in Florida, with some of the higher levels (17, 19, 22, and 24) completely missing in the Peach State.

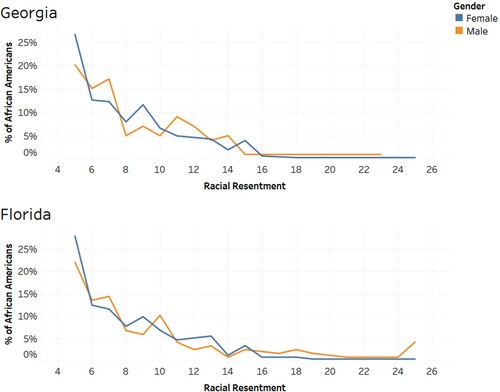

Consideration of the effect of gender sheds further light. According to exit polls, Trump did particularly well among Black male voters (Nagesh Citation2020). presents the distributions of female and male Black voters in Florida and Georgia along levels of racial resentment. Although in Florida Black female voters are slightly more racially resentful, the overall pattern is similar in both states, where female Black voters in the two southern states are concentrated around low levels of racial resentment (<10). Conversely, among Black males, the prevalence of highly racially resentful voters (>15) in Florida is significantly greater than in Georgia.

Drawing no distinction between the genders, the cumulative area under both curves in Georgia for values greater than 16 is virtually zero. Conversely, the integral under the two curves in Florida for racial resentment levels over 16 is approximately 7%. Blacks in Georgia and Florida are 31.5% and 16%, respectively. Election margins were 0.23% in Georgia and 3.4% in Florida. Thus, the 7% highly racially resentful African Americans in Florida, completely missing in Georgia, could easily account for why Trump did well in the former and lost the latter.

This analysis becomes of particular interest considering Stacey Abrams’ mobilization campaigns, in the 2018 gubernatorial elections and in the 2020 presidential elections. Her get out to vote campaigns continued the legacy of Blacks throughout history who:

dared to use their body, mind, and talents—as well as even the possibility of death—to oppose violence, discriminatory laws, social norms, and culture to make their voices heard and to elevate the standing of Black women and the Black community. (Dowe Citation2020)

This structural framework for the African American struggle throughout American history demonstrates the significance of the Abrams campaigns for our argument. Abrams’ campaigns were effective because of low levels of racial resentment in Georgia, which corresponded with more structural, and less individual, reasoning for Black voters’ grievances. Abrams identified the potential of this kind of political perspective among African American voters in the state. To increase turnout, Abrams emphasized overcoming obstacles unique to the Black community. This corresponds strongly with traditional structural explanations for the African American struggle, especially in southern states (Rubin Citation2020).

The juxtaposition of those two southern states also supports our racial resentment thesis in the face of an alternative account concerning ideology. In the case of African Americans, the alternative argument goes, those who tend to vote for Trump are just more conservative. Data from the Pew Research Center refute such an alternative account centering on the effect of ideology. Of the population identifying as conservative in Georgia, 25% are Blacks, while the number in Florida is merely 14% (Pew Citation2022). Hence, based solely on ideology and given the relatively large share of conservative Blacks there, if anything we would expect Trump in 2020 to carry the state of Georgia rather than Florida. What happened was the opposite.

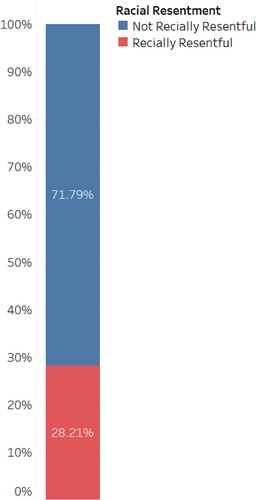

To further highlight the importance of racially resentful Blacks in the strategically crucial swing states, let us also examine Wisconsin. Black voters in this rust-belt state, which Trump carried in 2016 and almost won in 2020, are highly racially resentful compared to other states. shows that almost 30% of African Americans in the state are racially resentful, per the dummy version. Yet, only 6% of the conservative population consists of Blacks (Pew Citation2022). Since in Wisconsin conservative Blacks are scarce, Trump’s competitiveness in the state, despite gloomy projections prior to the elections, may be attributed to racial resentment more than to conservative ideology among African Americans. For those voters, high levels of racial resentment were associated with a greater likelihood of voting for Trump.

In sum, in Florida, where the presence of racially resentful Black voters was more significant compared to other swing states, in 2020 Trump did well electorally and carried the state with an impressive 3.36% gap, even more decisively than four years earlier. Likewise, in Wisconsin Trump lost by an extremely small margin of 20,682 votes. In this midwestern state, racially resentful Blacks constitute just under 30% of the African American electorate. Indeed, the Trump campaign was aware of this potential when its on-the-ground operation aimed to rally Black voters in urban centers in the state, especially in Milwaukee (Bush Citation2020; Orr and Isenstadt Citation2020). Compared to other swing states, including Florida and Wisconsin, in Georgia Blacks with low levels of racial resentment far outnumbered those highly resentful. This distinction contributes to our understanding of why Trump lost in 2020 after carrying the state by more than 5% in 2016.

Nationwide multivariate analyses

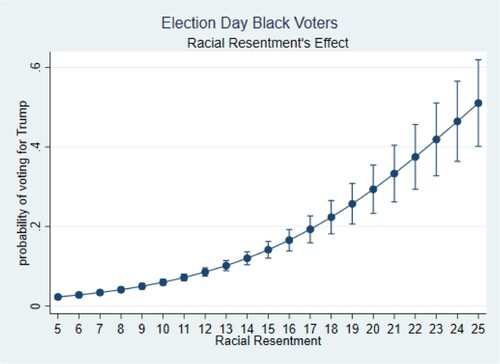

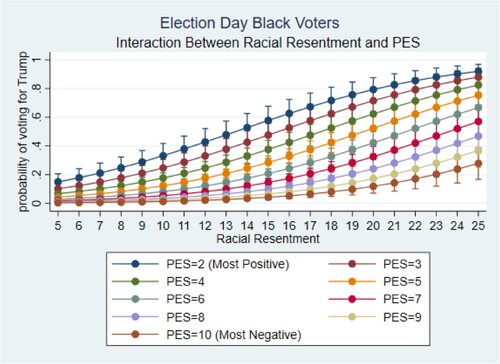

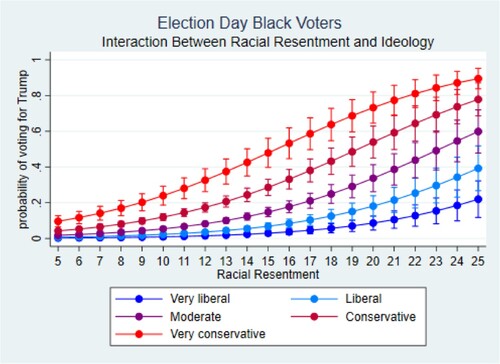

Racially resentful African Americans seem to have influenced election outcomes in several swing states in the 2020 presidential elections. Let us now turn to multivariate analyses of the country as a whole. In , levels of racial resentment are on the x-axis and the probability of voting for Trump is on the y-axis. Lending preliminary support for H1, this figure showcases a strong positive relationship among African American voters nationally between racial resentment and the probability of voting for Trump.

and respectively show the combined effects of racial resentment and perceptions of economic conditions, and of racial resentment and ideology, among Black voters. Those figures highlight the overriding power among Black voters of racial resentment even over variables widely recognized as consequential for voting behavior. Black voters with a positive perception of the economy are unlikely to vote for Trump if they are not racially resentful (). Similarly, Black voters who are very conservative but not racially resentful are unlikely to cast a ballot for the incumbent president in 2020 ().

presents models estimated for Black and nonblack voters (early voters and Election Day voters). As expected, in all models, racial resentment, perceptions of the economy, and ideology are highly significant and positive. The results in , presenting models estimated for Black voters only (early voters and Election Day voters), lend strong support to our key hypothesis. Racial resentment is statistically significant when controlling for ideology and perceptions of the economy. Racial resentment explains 28.98% of the variance in early Black voting for Trump. Furthermore, racial resentment accounts for 24.02% of the variance in Election Day Black voting. A highly significant positive correlation exists between racial resentment and voting for Trump among Black voters in models 5 and 6 (). Ceteris paribus, for each additional level of racial resentment, the likelihood of voting for Trump increases by 1.409 units for Black voters casting a vote early and 1.272 units for Black voters voting on Election Day. This effect is statistically significant, controlling for alternative hypotheses. In addition, these models respectively explain 49.60% and 40.83% of the variance in Black voting for Trump. The results for the effect of racial resentment are highly robust. Apart from the range of model specifications presented here, all yielding the same conclusions about the effect of racial resentment among Black voters, we also estimated a corresponding model using an independent dataset. Using data from the 2020 American National Election Studies (ANES), results in table A.18 in the Online Appendix remain unchanged, most importantly with a statistically significant effect for racial resentment among Black voters.

Table 1. Regression results for Black and nonblack voters (early voters and Election Day voters).

Table 2. Regression results for Black voters (early voters and Election Day voters).

Model 7 in tests the effects of our independent variables on the probability of voting for Trump among White voters (Election Day voters). Since the number of White respondents to the set of five racial resentment questions was not sufficiently high, we also specified the model with an alternative measure (model 8). In model 8, we look at a single racial resentment question, measuring agreement with the statement: “Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class.”

Table 3. Regression results for White voters (Election Day voters).

Addressing concerns about a possible confluence of principled ideologies regarding the appropriate role of government and the battery’s indicators (Carmines, Sniderman, and Easter Citation2011), which might cause a tautological bias, models 7 and 8 demonstrate highly significant relationships between both the complete racial resentment variable and the single question of racial resentment, and the probability of voting for Trump. Hence, like DeSante (Citation2013) and in defiance of the ideology argument, we show that racial considerations indeed remain a key explanatory tool for political behavior in America.

includes regression results for the effects of the two additional independent variables—religiosity and sexism—on the probability of voting for Trump among Black voters (early voters and Election Day voters). When specified in separate models, sexism and religiosity are significant, which prima facie affirms H3 and H4. Yet, religiosity loses significance completely when racial resentment is specified in the same model. Sexism is significant only in the model for Election Day voters when the other variables are specified. Overall, racial resentment has the strongest explanatory power for Black voting compared to any of the other independent variables we tested in our models.

Table 4. Effects of religiosity and sexism among Black voters (early voters and Election Day voters).

To test the external validity of our findings, we also want to examine whether the voting patterns we identified are unique to the 2020 elections, and specifically to Donald Trump as the candidate in those elections. In other words, we wish to examine whether even in previous elections, some African Americans had voted Republican, and that those who did were also high on racial resentment. Tables A.19 and A.20 in the Online Appendix include regression results for the effects of racial resentment on Black voters in 2016 and 2012. We find that in both election years, a highly significant positive correlation exists between racial resentment and voting for Trump and Romney among Blacks. Our findings are not limited to the 2020 presidential elections. At least in the last three presidential elections, some Black voters cast a Republican vote, and those who did also likely scored high on the racial resentment scale.

Versions of all models with predictors specified as dummies, rather than continuous variables, yielded substantively indistinguishable results and are reported in the Online Appendix. Additionally, for the purpose of robustness, we also included in the Online Appendix four other combinations of racial resentment measures, each based on a different composition of two or three questions taken from the same five survey items. A strong testament to the robustness of our findings, the results are substantively indistinguishable.

Discussion

Our results offer a plausible mechanism for why a racially controversial president gained electoral success among minorities, in particular among African Americans. Frameworks highlighting their common fate notwithstanding, Black voters are not as homogenous as commonly thought. There is variance among African Americans even in the extent to which Black voters score high on the racial resentment scale.

Not unlike White voters, there is considerable variance among African Americans. Racial resentment is present among this constituency and is highly correlated with support for Trump. A significant correlation between negative attitudes toward minorities and voting for Trump, which has been detected by a large body of work tracing the effect of racial resentment on White voters in 2016 and 2020, is present also among African Americans. Although the prevalence of racial resentment among Blacks is smaller relative to Whites, its effect on the probability of voting for Trump is substantial. What is more, the absolute numbers of Black voters switching to or sticking with the Trump camp in 2020 in some parts of the country—like Florida, Wisconsin, and even the ostensibly not-contested Minnesota—were substantial. Not coincidentally, we argue, these are also the states where levels of racial resentment among Black voters were higher. Given the strategic location of concentrations of such voters in swing states, racial resentment among Blacks is electorally consequential both in terms of its geographical variance and in absolute terms.

Conclusions

Throughout his four years in office, and even before he was elected, Donald Trump was perceived by many as a candidate and then president hostile to minority groups. Moreover, many (Cole Citation2019; Rosenfeld Citation2020) attributed to Trump White supremacist positions, when he championed White identity seeking to reestablish social hierarchal structures where Whites are at the top (Jardina Citation2019). Indeed, Trump’s signature campaign slogan—Make America Great Again—was called out as a racial cue, or a “racist dog whistle” (HuffPost Video), alluding to the reinstitution of a socio-political reality with racial hierarchies as an organizing principle. Following his 2016 upset victory, a large body of scholarship argued for a significant relationship between anti-minorities sentiments among White voters and voting for Trump (Buyuker et al. 2021; Jardina Citation2019). Likewise, classical texts identified the effects of anti-minority sentiments on the political behavior of different groups in American society and among Whites in particular (Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Citation2018).

Yet, the 2020 presidential elections offered a conundrum for political scientists: compared with his performance in 2016, the incumbent president gained increasing support among Blacks. How was it possible that such a controversial candidate in terms of race relations managed to broaden his support among racial minorities? Our argument may be surprising, but the underlying mechanism is straightforward. Racial resentment occupies a leading role in explaining both White and Black support for Trump.

An almost century-long commitment to the Democratic Party may seem like proof of Black unequivocal collective mobilization. Yet, our study questions African Americans’ cohesiveness as an electoral force. We demonstrate that there are certain factors, with racial resentment key among them, that weaken what is considered almost automatic Black loyalty to the Democrats. Those results are robust as presented in various model specifications from different data sources. The Black constituency is more diverse than commonly thought and on a range of issues, even on such issues where we would expect near unanimity such as positions toward their own community. This diversity is consequential because it changes the way we think about and theorize the Black racial group. Secondly, the strategic geographical location of African Americans renders this diversity a fulcrum of decisive influence on election outcomes.

Our project helps to cast doubt on a key premise. Although the bulk of African American support belongs to the Democratic Party (Rigueur Citation2014), Blacks’ presumed unique political cohesion is misguided (Gurin, Hatchett, and Jackson Citation1989). Not only do we show that the outliers among this constituency are growing, with distinctly African American population centers—in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Florida, for example—becoming more pro-Trump and pro-GOP between 2016 and 2020, but we also account for this trend by the least expected indicator: racial resentment. All five of our hypotheses find strong support in the data. African American voters higher on racial resentment, with a more conservative ideology, and a more positive perception of economic conditions, were more likely to support Trump. Religiosity and sexism are also significantly correlated with voting for Trump among African Americans when specified in separate models. Racial resentment, however, has an overriding effect. Conservative Blacks who are not racially resentful will overwhelmingly stay away from Trump. Likewise, people of color who believe the economy is doing well would still be unlikely to vote for the incumbent if they are not racially resentful.

The racially resentful segment in the Black constituency has important electoral consequences not least because of its relative concentration in swing states. Compared to other swing states, including Florida and Wisconsin, in Georgia Blacks with low levels of racial resentment far outnumbered those highly resentful. This also shows that campaigning is not sufficient to harvest African American support for the GOP and that racial resentment has consequential effects on campaigning among this constituency. The 2020 “Black Voices for Trump” campaign, whose objective was to rally Black voters, started in November 2019 in Atlanta, Georgia (Shah Citation2019). It later spread to other swing states like Wisconsin, Ohio, and Florida (Bush Citation2020). Whereas in Georgia Trump was down more than 5% in 2020 compared to his 2016 performance, in Wisconsin he almost repeated his electoral achievement, losing in 2020 by a 0.63% margin, compared to winning by 0.77% in 2016. In Florida, Trump won impressively by more than 3%. Real voting data indicate that Black population centers in Milwaukee and the Miami area were more pro-Trump in 2020 than in 2016. But GOP campaign resources were allocated in all three states: Georgia, Wisconsin, and Florida, with Atlanta serving as the focal point for Trump’s national strategy to win Black support. Given the higher levels of racial resentment among Black voters in Wisconsin and Florida relative to Georgia, all of these suggest that mere mobilization efforts do not deterministically dictate election outcomes and that racial resentment indeed played a pivotal role in how the elections turned out, even among Black voters.

In states where Trump won or almost won, a few thousand votes of racially resentful Blacks could have tilted the outcome one way or the other, either in Trump’s favor or against him. This group of voters—racially resentful Blacks—is a largely overlooked constituency, which political science has yet to consider along with its significant political sway (Kinder and Sanders Citation1996).

Given the political consequentiality of this group and its nonnegligible prevalence among African Americans, our findings lend support to the battery’s use for gauging racial resentment and its effect on political behavior in American politics. In defiance of counter arguments (Huddy and Feldman Citation2009), we show a highly significant relationship between racial resentment and the probability of voting for Trump, suggesting that racial considerations remain a key explanatory tool for political behavior in America (DeSante Citation2013). Keeping in mind that the battery’s original definition related to sentiments held by White Americans toward the Black community (Kinder and Sanders Citation1996), and thus presupposed a unilateral White disposition, our results suggest also that a reconsideration of the very term—racial resentment—may be in place. Whereas for Whites, racial resentment means symbolic racism, for Blacks the indicator entails a different meaning. Although theoretically related, Black racial resentment is not the same as insulated Blackness (Lewis and Nelson Citation2022). Racially resentful Blacks could be characterized by disdain and negative feelings toward their own racial group. Given Trump’s long history of downgrading Black people, the distinction between these two trends may explain why racial resentment manifests itself into a vote for Trump in some Black people and not others. The negative component found in racially resentful Blacks is arguably stronger among Black Trump voters than among those who did not cast a vote for him, even if both score high on the scale.

There are more African Americans in the mold of Justice Clarence Thomas than previously thought and the Black constituency in general is also more diverse than has been commonly held. The electoral impact of those racially resentful African Americans is far from marginal, even in comparison to their more numerous fellow Black voters who are closer to Stacy Abrams in their worldview, ideology, and political positions.

Our research offers three key venues for future work. First, the findings here call for further exploration of the effects of racial resentment on political behavior among African Americans. In particular, it should be further examined whether changes in levels of racial resentment between election cycles correlate with changes in support for Republican candidates among Black voters. The premise that the Black constituency is characterized by a unanimous perspective in racial matters proves invalid. Second, a rephrasing of the term itself might be warranted. Originally defined as negative White sentiment toward Blacks, racial resentment and the battery measuring it may capture more than that. Finally, this research focuses on the African American community, but future work could utilize our theoretical framework with regard to other minority groups, such as Latino or Asian Americans, where pro-Trump sentiments also grew between 2016–2020. While the underlying mechanisms might be different, the counterintuitive trend is important and should be more thoroughly analyzed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Center for the Study of the United States with the Fulbright Program at Tel Aviv University. This work received support from the Institute for Humane Studies under grant IHS016892 and from the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund. The authors would also like to thank participants, chair, and discussants at the Midwest Political Science Association Annual Meeting in Chicago, IL, April 2023, in the panel: Trump's America.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Alice Park, Charlie Smart, Rumsey Taylor, and Miles Watkins, “An Extremely Detailed Map of the 2020 Election,” New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/upshot/2020-election-map.html

2 United States Census Bureau, “Miami Gardens city, Florida,” July 1, 2018, https://archive.ph/20200214005443/https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/cf/1.0/en/place/Miami%20Gardens%20city,%20Florida/POPULATION/PEP_EST#selection-253.0-266.0

3 For further information about the dataset, visit: https://cces.gov.harvard.edu/.

4 Data for respondents choosing the option of 6, which signifies “Not sure,” were omitted.

5 Data from the 2020 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES).

6 Complete results of all figures and tables appear in tables A.4–A.18 in the Online Appendix.

References

- Allen, Richard L., Michael C. Dawson, and Ronald E. Brown. 1989. “A Schema-Based Approach to Modeling an African-American Racial Belief System.” American Political Science Review 83 (2): 421–441. https://doi.org/10.2307/1962398.

- Besco, Randy, and J. Scott Matthews. 2022. “Racial Spillover in Political Attitudes: Generalizing to a New Leader and Context.” Political Behavior, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09777-3.

- Brooks, Clem, and David Brady. 1999. “Income, Economic Voting, and Long-Term Political Change in the U.S., 1952-1996.” Social Forces 77 (4): 1339–1375.

- Brown-Dean, Khalilah L. 2019. Identity Politics in the United States. Medford, MA: Polity Press.

- Bush, Daniel. 2020. “Inside the Trump campaign’s strategy for getting Black voters to the polls.” PBS. July 7. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/how-the-trump-campaign-hopes-to-boost-black-voter-turnout.

- Capers, Juree, and Candis Watts Smith. 2016. “Straddling Identities: Identity Cross-Pressures on Black Immigrants’ Policy Preferences*.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 4 (3): 393–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2015.1112823.

- Carmines, Edward G., Paul M. Sniderman, and Beth C. Easter. 2011. “On the Meaning, Measurement, and Implications of Racial Resentment.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 634 (1): 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716210387499.

- Cassese, Erin C., Tiffany D. Barnes, and Regina P. Branton. 2015. “Racializing Gender: Public Opinion at the Intersection.” Politics & Gender 11 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000567.

- Cepuran, Colin J. G., and Justin Berry. 2022. “Whites’ Racial Resentment and Perceived Relative Discrimination Interactively Predict Participation.” Political Behavior 44 (2): 1003–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09786-2.

- Chong, Dennis, and Reuel Rogers. 2005. “Racial Solidarity and Political Participation.” Political Behavior 27 (4): 347–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-005-5880-5.

- Cole, Devan. 2019. “Elizabeth Warren: Trump is a white supremacist.” CNN, August 8. https://edition.cnn.com/2019/08/08/politics/elizabeth-warren-donald-trump-white-supremacist/index.html.

- Collins, Sean. 2020. “Trump made gains with Black voters in some states. Here’s why.” Vox, November 4. https://www.vox.com/2020/11/4/21537966/trump-black-voters-exit-polls.

- Dawson, Michael C. 1994. Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Dent, David. 2020. “More Black Men Went With Trump This Time. I Asked a Few of Them Why.” Daily Beast. November 24. https://www.thedailybeast.com/more-black-men-went-with-trump-this-time-i-asked-a-few-of-them-why.

- DeSante, Christopher D. 2013. “Working Twice as Hard to Get Half as Far: Race, Work Ethic, and America’s Deserving Poor.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (2): 342–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12006.

- Dowe, Pearl K. Ford. 2020. “Resisting Marginalization: Black Women’s Political Ambition and Agency.” PS: Political Science & Politics 53 (4): 697–702. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520000554.

- Edwards, Adrienne L. 2022. “(Re)Conceptualizing Black Motherwork as Political Activism.” Journal of Family Theory & Review 14 (3): 404–411.

- Fiorina, Morris. 1981. Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Fisher, Patrick. 2016. “Economic Performance and Presidential Vote for Obama: The Underappreciated Influence of Race.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 4 (1): 30–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2015.1050413.

- Friess, Steve. 2022. “GOP Bets on Black Conservatives As Key to Victory: ‘We Change or We Die’.” Newsweek Magazine, February 9. https://www.newsweek.com/2022/02/18/gop-bets-black-conservatives-key-victory-we-change-we-die-1677030.html.

- Gaines, Kevin K. 2021. “Reflections on 2020.” Peace & Change 46 (4): 323–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/pech.12485.

- Gay, Claudine. 2014. “Knowledge Matters: Policy Cross-Pressures and Black Partisanship.” Political Behavior 36 (1): 99–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9227-3.

- Gay, Claudine, and Katherine Tate. 1998. “Doubly Bound: The Impact of Gender and Race on the Politics of Black Women.” Political Psychology 19 (1): 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00098.

- Gurin, Patricia, Shirley Hatchett, and James S. Jackson. 1989. Hope and Independence: Blacks’ Struggle in the Two Party System. New York: Russell Sage.

- Harris, Frederick, and Brian D. McKenzie. 2015. “Unreconciled Strivings and Warring Ideals: The Complexities of Competing African-American Political Identities.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 3 (2): 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2015.1024260.

- Huddy, Leonie, and Stanley Feldman. 2009. “On Assessing the Political Effects of Racial Prejudice.” Annual Review of Political Science 12 (1): 423–447. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.062906.070752.

- Hunt, Matthew O. 2007. “African American, Hispanic, and White Beliefs About Black/White Inequality 1977-2004.” American Sociological Review 72 (3): 390–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240707200304.

- Jacobson, Cardell K. 1985. “Resistance to Affirmative Action.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 29 (2): 306–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002785029002007.

- Jardina, Ashley. 2019. White Identity Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kam, Cindy D., and Camille D. Burge. 2018. “Uncovering Reactions to the Racial Resentment Scale Across the Racial Divide.” The Journal of Politics 80 (1): 314–320. https://doi.org/10.1086/693907.

- Kam, Cindy D., and Donald R. Kinder. 2012. “Ethnocentrism as a Short-Term Force in the 2008 American Presidential Election.” American Journal of Political Science 56 (2): 326–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00564.x.

- Kessler, Glenn. 2020. “Trump’s claim that he’s done more for black Americans than any president since Lincoln.” Washington Post, June 5. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/06/05/trumps-claim-that-hes-done-more-blacks-than-any-president-since-lincoln/.

- Kinder, Donald R., and Allison Dale-Riddle. 2012. The End of Race? 2008, Obama, and Racial Politics in America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Kinder, Donald R., and Lynn M. Sanders. 1996. Divided by Color. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Laird, Chryl. 2019. “Black Like Me: How Political Communication Changes Racial Group Identification and its Implications.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 7 (2): 324–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2017.1358187.

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S., and Mary Stegmaier. 2000. “Economic Determinants of Electoral Outcomes.” Annual Review of Political Science 3 (1): 183–219. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.183

- Lewis, Timothy E., and S. J. Nelson. 2022. “Insulated Blackness: The Cause for Fracture in Black Political Identity.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 10 (5): 754–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2021.1892783.

- Liptak, Kevin, and Kristen Holmes. 2020. “Trump calls Black Lives Matter a ‘symbol of hate’ as he digs in on race.” CNN. July 1. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/07/01/politics/donald-trump-black-lives-matter-confederate-race/index.html.

- Lopez, German. 2020. “Donald Trump’s long history of racism, from the 1970s to 2020.” Vox. August 13. https://www.vox.com/2016/7/25/12270880/donald-trump-racist-racism-history.

- Lyle, Monique L. 2014. “How Racial Cues Affect Support for American Racial Hierarchy among African Americans and Whites.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 2 (3): 350–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2014.928643.

- Massey, Douglas S., and Nancy A. Denton. 1993. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- McAdam, Doug. 2015. “Be Careful What You Wish For: The Ironic Connection Between the Civil Rights Struggle and Today’s Divided America.” Sociological Forum 30 (S1): 485–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12173.

- McClain, Paula D., Jessica D. Johnson Carew, Eugene Walton, Jr., and Candis S. Watts. 2009. “Group Membership, Group Identity, and Group Consciousness: Measures of Racial Identity in American Politics?” Annual Review of Political Science 12 (1): 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.102452.

- Mendelberg, Tali. 1997. “Executing Hortons: Racial Crime in the 1988 Presidential Campaign.” Public Opinion Quarterly 61 (1, Special Issue on Race): 134–157. https://doi.org/10.1086/297790.

- Merseth, Julie Lee. 2018. “Race-Ing solidarity: Asian Americans and support for Black Lives Matter.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 6 (3): 337–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2018.1494015

- Mohamed, Besheer, Kiana Cox, Jeff Diamant, and Claire Gecewicz. 2021. “Faith Among Black Americans.” Pew Research Center. February 16. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/02/16/faith-among-black-americans/.

- Moody, Chris, and Kristen Holmes. 2015. “Donald Trump’s history of suggesting Obama is a Muslim.” CNN. September 18. https://edition.cnn.com/2015/09/18/politics/trump-obama-muslim-birther/index.html.

- Nagesh, Ashitha. 2020. “US election 2020: Why Trump gained support among minorities.” BBC, November 22. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-54972389.

- Nunnally, Shayla, and Niambi Carter. 2012. “Moving from Victims to Victors: African American Attitudes on the “Culture of Poverty” and Black Blame.” Journal of African American Studies 16 (3): 423–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-011-9197-7.

- Orr, Gabby, and Alex Isenstadt. 2020. “Trump campaign’s plan to woo black voters: Retail stores.” Politico, February 26. https://www.politico.com/amp/news/2020/02/26/donald-trump-black-voters-retail-stores-117756.

- Ostfield, Mara, and Michelle Garcia. 2020. “Black men shift slightly toward Trump in record numbers, polls show.” NBC NEWS. November 4. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/black-men-drifted-democrats-toward-trump-record-numbers-polls-show-n1246447.

- Pattillo-McCoy, Mary. 1999. Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril among the Black Middle Class. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pew. 2022. “Racial and ethnic composition among conservatives by state.” Retrieved July 10, 2022, from: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/religious-landscape-study/compare/racial-and-ethnic-composition/by/state/among/political-ideology/conservative/.

- Philpot, Tasha S. 2017. Conservative but Not Republican: The Paradox of Party Identification and Ideology among African Americans. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Rigueur, Leah Wright. 2014. The Loneliness of the Black Republican. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rosenfeld, Ross. 2020. “There’s no Longer any Doubt: Trump is a White Supremacist.” New York Daily News, July 1. https://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/ny-oped-trump-white-supremacist-20200701-5zumhjygabhgfckydm7xyhbm6a-story.html.

- Rubin, Jennifer. 2020. “Distinguished pol of the Week: Stacey Abrams Showed Democrats how to win.” Washington Post, December 13. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/12/13/distinguished-pol-week-she-showed-democrats-how-win/.

- Shah, Khushbu. 2019. “President Launches ‘Black Voices for Trump’ Campaign in Atlanta.” The Guardian, November 8. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/nov/08/donald-trump-black-voices-african-american-voters.

- Shaw, Todd C., Kirk A. Foster, and Barbara Harris Combs. 2019. “Race and Poverty Matters: Black and Latino Linked Fate, Neighborhood Effects, and Political Participation.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 7 (3): 663–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2019.1638800.

- Sides, John, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck. 2016. “The Electoral Landscape of 2016.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 667 (1): 50–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216658922.

- Sides, John, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck. 2018. “Hunting Where the Ducks are: Activating Support for Donald Trump in the 2016 Republican Primary.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 28 (2): 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2018.1441849.

- Simien, Evelyn M. 2013. “African American Public Opinion: Past, Present, and Future Research.” Politics, Groups and Identities 1 (2): 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2013.785961.

- Skelley, Geoffrey, and Anna Wiederkehr. 2020. “Trump Is Losing Ground With White Voters But Gaining Among Black And Hispanic Americans.” FiveThirtyEight. October 19. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/trump-is-losing-ground-with-white-voters-but-gaining-among-black-and-hispanic-americans/

- Sommer, Udi. 2013. “Representative Appointments: The Effect of Women’s Groups in Contentious Supreme Court Confirmations.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 34 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2013.747876.

- Sommer, Udi, Or Rappel-Kroyzer, Amy Adamczyk, Lindsay Lerner, and Anna Weiner. 2023. “The Political Ramifications of Judicial Institutions: Establishing a Link Between Dobbs and Gender Disparities in the 2022 Midterms.” Socius 9. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231231177157.

- Tajfel, Henri, and John. C. Turner. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by William G. Austin, and Stephen Worchel, 33–37. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Tate, Katherine. 2010. What’s Going On? Political Incorporation and the Transformation of Black Public Opinion. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

- Tesler, Michael. 2016. Post-Racial or Most-Racial? Race and Politics in the Obama Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Thompson, Andrew Ifedapo, and Ethan C. Busby. 2023. “Defending the Dog Whistle: The Role of Justifications in Racial Messaging.” Political Behavior 45 (3): 1241–1262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09759-x.

- Tidmore, Christopher. 2020. “One in Three Black men Backed Trump in ‘Blue Wall’ States.” The Cincinnati Herald, November 26. https://thecincinnatiherald.com/2020/11/one-in-three-black-men-backed-trump-in-blue-wall-states/.

- Tien, Charles, Richard Nadeau, and Michael S. Lewis-Beck. 2012. “Obama and 2012: Still a Racial Cost to Pay?” PS: Political Science & Politics 45 (4): 591–595. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096512000704.

- Vaughan, Alan G. 2021. “Phenomenology of the Trickster Archetype, U.S. Electoral Politics and the Black Lives Matter Movement.” Journal of Analytical Psychology 66 (3): 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5922.12698.

- Welch, Susan, and Lorn S. Foster. 1992. “The Impact of Economic Conditions on the Voting Behavior of Blacks.” The Western Political Quarterly 45 (1): 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591299204500115.

- White, Ismail K. 2007. “When Race Matters and When It Doesn’t: Racial Group Differences in Response to Racial Cues.” American Political Science Review 101 (2): 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055407070177.

- Wilson, William J. 1978. The Declining Significance of Race: Blacks and Changing American Institutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wolak, Jennifer. 2018. “Feelings of Political Efficacy in the Fifty States.” Political Behavior 40 (3): 763–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9421-9.

- Zigerell, Lawrence J. 2015. “Distinguishing Racism from Ideology: A Methodological Inquiry.” Political Research Quarterly 68 (3): 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912915586631.