ABSTRACT

Critical thinking, a complex set of cognitive skills, and the ability to communicate one’s thoughts are vital in successful studying for new higher education students. The aim of this study was to explore the effect of socioeconomic background and prior academic performance on new students’ critical thinking and writing. The participants were 1006 first-year students from a range of disciplines in 18 Finnish higher education institutions. An open-ended performance task was used to investigate students’ critical thinking and writing. Structural equation modelling was used to analyse the data. The grade in the native language and the scholarly culture of a student's childhood home were found to be the most important predictors of strong critical thinking and writing. In contrast, parents’ education and students’ grades in mathematics were not significant. As Finnish student admissions are reformed, there is a growing need to understand the predictive value of relevant background factors. Findings give insights into the development of admissions and remind developers that not all prior performances have equal predictive value. Findings invite careful consideration in determining which skills are necessary for new students. It is suggested that in future research, a wider range of skills should be investigated.

Introduction

In European Union, the development of admissions has been identified as an important tool for more inclusive higher education (Orr et al. Citation2017). Discussion about different admission systems is on-going in several European countries (Steenman Citation2018; Klemenčič Citation2018). In Finland, the focus on policies surrounding the admissions has been on adolescents’ swiftly transition to higher education (Haltia, Isopahkala-Bouret, and Jauhiainen Citation2019). It is believed that the extremely selective higher education admissions have led to lengthened transition (e.g. OECD Citation2019a). As a solution, admissions were reformed in 2020, and the emphasis was shifted from entrance examinations towards diploma-based admissions focusing on the National Matriculation Examination grades (Kleemola and Hyytinen Citation2019). While the reform has influenced the choices the adolescents make, little is known about grades’ value in measuring preparedness and skills that are central in higher education studies, such as critical thinking and writing (cf. Richardson, Abraham, and Bond Citation2012).

A critical thinker combines complex cognitive skills into a purposeful and self-regulatory act of thinking (Halpern Citation2014). Critical thinking includes analysis, reasoning, problem solving, argumentation, and evaluation of information (Facione Citation1990; Halpern Citation2014). For students in higher education, critical thinking and the ability to communicate it in a variety of ways are vital in learning and using discipline-specific knowledge (e.g. Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Halpern Citation2014). Therefore, students entering higher education benefit from strong critical thinking skills (Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Badcock, Pattison, and Harris Citation2010; O’Hare and McGuinness Citation2015). However, it has been found that not all students have the same skill level in critical thinking when they start to study in a higher education institution (Evens, Verburgh, and Elen Citation2013; Hyytinen, Toom, and Postareff Citation2018; Kleemola, Hyytinen, and Toom Citation2021; Utriainen et al. Citation2017; Arum and Roksa Citation2011). In an international context, there are some findings indicating that critical thinking can be predicted by students’ prior academic performance and by their socioeconomic background (Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Evens, Verburgh, and Elen Citation2013; Leest and Wolbers Citation2021). In Finland, there is not much evidence about these factors’ significance (cf. Utriainen et al. Citation2017; Lindblom-Ylänne, Lonka, and Leskinen Citation1996). While Finland has been striving for equal educational opportunities, recent findings indicate that the impact of socioeconomic background on adolescents’ learning outcomes in Finland is increasing (Leino et al. Citation2019; Salmela-Aro and Chmielewski Citation2019; Tikkanen Citation2019).

Following the admissions reform in Finland, there is a growing need to understand more about the interplay of the Matriculation Examination grades and socioeconomic background and their impact on the quality of critical thinking in new higher education students. The aim of the present study is to provide insights into the antecedents of critical thinking and the preparedness of students, particularly their prior academic performance and their socioeconomic background. The study with its large, nation-wide dataset and performance-based assessment of critical thinking, also allows a unique opportunity to contribute to the on-going development of Finnish higher education admissions.

Critical thinking and writing in higher education

Critical thinking is a combination of knowledge, cognitive skills, and affective dispositions (Halpern Citation2014; Hyytinen, Toom, and Shavelson Citation2019), and many complex cognitive skills are required (Hyytinen and Toom Citation2019; Shavelson Citation2010; Shavelson et al. Citation2019). Analytical reasoning, problem solving, and evaluation of information are activated in critical thinking in a holistic manner (Facione Citation1990; Halpern Citation2014; Hyytinen, Toom, and Shavelson Citation2019; Shavelson et al. Citation2019; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, to make use of one’s critical thinking, it needs to be communicated to others, particularly in the assessment of critical thinking. Therefore, when critical thinking is assessed through an open-ended performance task in which participants communicate their thoughts in writing, we should consider the written manifestation of critical thinking or critical thinking and writing to be the target of investigation. Additionally, the relationship between critical thinking and writing is not merely an intermediary; writing has an important role to play in developing critical thinking (e.g. Kuhn Citation2019).

Critical thinking and writing are essential in studying and learning in higher education; they are needed for a successful acquisition of knowledge and skills (Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Badcock, Pattison, and Harris Citation2010; Halpern Citation2014). For new higher education students, they are essential skills as they facilitate discipline-specific learning. It has been found that critical thinking is an important predictor of later success and adaptation to higher education (Arum and Roksa Citation2011; O’Hare and McGuinness Citation2015; van der Zanden et al. Citation2019). Even though critical thinking is often mentioned as the most important outcome and ideal of higher education, its development during higher education has been questioned (Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Shavelson Citation2010). It seems that students who have deficiencies in their critical thinking when they enter higher education might not develop their skills or might even regress (Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Badcock, Pattison, and Harris Citation2010; Evens, Verburgh, and Elen Citation2013). While experiments have shown that the development of critical thinking in higher education is possible (Heijltjes et al. Citation2014), an important foundation for it is built on prior education (Kuhn Citation2005). Therefore, it is worrying that there is a large variation in critical thinking and writing skills among new higher education students, even after the selective admission procedures (Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Hyytinen, Toom, and Postareff Citation2018; Utriainen et al. Citation2017).

Prior academic performance as a predictor of critical thinking

Upper secondary school grades have been considered as an important predictor of later quality of critical thinking (Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Lindblom-Ylänne, Lonka, and Leskinen Citation1996; Richardson, Abraham, and Bond Citation2012; Utriainen et al. Citation2017). Some studies suggest that there is an interaction between the educational choices and critical thinking skills. Students with general upper secondary education show stronger critical thinking compared to students with vocational or technical secondary education (Evens, Verburgh, and Elen Citation2013; Nissinen et al. Citation2021). The instigators of these differences are unknown. It might be due to the different emphases in these educational tracks, but critical thinking skills could also influence choices: students with stronger skills may gravitate towards more academic and knowledge-intensive educational paths compared to students with poorer skills (cf. Heiskala, Erola, and Kilpi-Jakonen Citation2021).

Finnish higher education institutions have recently transformed their student admission procedures, granting significantly more weight to student performance in the upper secondary school, namely their grades in the National Matriculation Examination (Kleemola and Hyytinen Citation2019). The Matriculation Examination with its subject-specific tests is designed to test students’ mastery of the upper secondary school curriculum (Finlex Citation2019), and little is known about the grades’ predictive value. Some studies have shown that the overall success in the Matriculation Examination seems to predict critical thinking to some extent (Utriainen et al. Citation2017; Lindblom-Ylänne, Lonka, and Leskinen Citation1996). However, the reformed admissions emphasize Matriculation Examination grades in native language and mathematics, and there has been plenty of public debate on these subjects’ suitability for the purpose. There is contradictory evidence on these grades’ predictive value (Kallio et al. Citation2018; Kleemola and Hyytinen Citation2019; see also Koster and Verhoeven Citation2017; Steenman Citation2018).

In general, grades have predictive value on future skills that are similar to the skills that the grade is awarded for (McClelland Citation1973; Steenman Citation2018). The native language test requires students to show their writing, critical reading, synthesis, and writing mechanics skills (Matriculation Examination Board Citation2020). While no research exists on the association between the achievement in the native language test and critical thinking and writing skills, it is feasible to assume that such association exists due to the similarities in the skills they require. However, the role of mathematics is not as obvious. Its significance in admissions has been called into question in fields with no apparent mathematical aspects, such as the humanities and social sciences. While it has been found that students with an emphasis on mathematics in upper secondary school outperformed other students in admissions even before the reform (Kaleva et al. Citation2019), the reasons behind this are unclear. Recent reports suggest that after comprehensive school at the age of 15, students with a positive attitude to mathematics are more likely to continue at general upper secondary school rather than undertaking vocational programs (Metsämuuronen Citation2017). Therefore, it is feasible that the predictive value of mathematics has nothing to do with actual mathematical skills, but with associated qualities. While the association between prior academic performance and critical thinking has been investigated to some degree, it is important to remember that the success in prior education does not emerge in a vacuum, but the students’ socioeconomic background needs to be considered as well.

Socioeconomic background and critical thinking

Socioeconomic variables have been considered to be the most important factor in educational inequality (Jerrim et al. Citation2019; Marks Citation2011). Critical thinking is one of the educational outcomes that has been found to be associated with socioeconomic background (Arum and Roksa Citation2011), although performance-based research on the topic is scarce. Overall, a higher parental education and a more professional parental occupation are mostly associated with educational resources and higher performance (Chiu Citation2016; Marks Citation2014). It has long been considered that the Finnish educational system offers equal opportunities to learning for everyone regardless of their socioeconomic background. However, recently there have been indications that educational inequalities due to socioeconomic status are increasing in the Finnish context (Leino et al. Citation2019; Salmela-Aro and Chmielewski Citation2019; Tikkanen Citation2019).

In addition to the more traditional aspects of socioeconomic background such as parents’ education, it seems that the scholarly culture of the childhood home has a substantial impact on later educational outcomes (Cheung and Andersen Citation2003; Sikora, Evans, and Kelley Citation2019). Importantly, scholarly culture does not refer to formal cultural activities but rather to a home environment that encourages any reading and learning activities (De Graaf Citation1986; Evans and Kelley Citation2002). It seems that regardless of the parents’ education or economic resources, encouraging the scholarly culture is associated with educational attainment (Evans et al. Citation2010) and generic skills in adulthood (Sikora, Evans, and Kelley Citation2019). Findings in PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) indicate a similar impact of scholarly culture on generic skills (Evans, Kelley, and Sikora Citation2014; Evans et al. Citation2010) also in the Finnish context (Leino et al. Citation2019). Earlier research indicates that scholarly culture is best assessed through the number of books in the childhood home, which is closely associated with other aspects of scholarly culture, such as reading habits (Evans and Kelley Citation2002). Books are a cognitive resource themselves but also indicators of other resources that are vital in learning (Evans, Kelley, and Sikora Citation2014).

The challenge in investigating the impact of socioeconomic background is that there is no conventional way to conceptualize it (see Marks Citation2011), while educational, economic, social, and cultural aspects are often seen as a part of it (Chiu Citation2016). In the present study, the parents’ education and scholarly culture are used as indicators of students’ socioeconomic background. Parents’ education is one of the most often used indicators, particularly in recent Finnish studies (Heiskala, Erola, and Kilpi-Jakonen Citation2021; Salmela-Aro and Chmielewski Citation2019). Furthermore, scholarly culture, namely the number of books in the childhood home, has been selected because of its significance in PISA (Evans, Kelley, and Sikora Citation2014; OECD Citation2019b).

While various socioeconomic background variables have repeatedly been found to be a source of inequality in education, for instance, in the stratification of educational choices, it has been pointed out that their influence is intertwined with academic performance (Heiskala, Erola, and Kilpi-Jakonen Citation2021; Kilpi-Jakonen, Erola, and Karhula Citation2016). Therefore, it is important to consider the interplay between these elements.

Few studies have explored the associations between socioeconomic background, prior academic performance, and critical thinking. However, in the USA, it seems that higher socioeconomic status leads to higher grades in secondary education, which in turn leads to higher quality critical thinking at the point of transition to higher education (Arum and Roksa Citation2011). In the Finnish context, research on some of the concepts in focus gives some clues about the possible interplay between these variables. For instance, it has been found that the higher the level of the parents’ education, the better students perform in mathematics (Metsämuuronen Citation2017). A similar association has been found between socioeconomic background and skills in the native language (Kauppinen and Marjanen Citation2020). In light of these findings, it seems plausible that socioeconomic background and prior academic performance have a combined effect on critical thinking and writing. However, there has been no research about this interaction in the Finnish context.

The present study gives new information about the antecedents of critical thinking and writing, enabling higher education institutions to identify and support entering students that are likely to have challenges in their critical thinking. Additionally, findings provide insights into the development of student admissions, pinpointing strengths, and challenges in the newly reformed Finnish procedures, e.g. in subject emphases.

Aim of the study

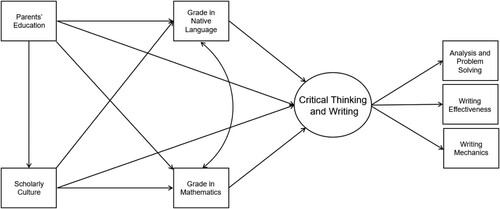

In the present study, the aim was to investigate the students’ prior academic performance and socioeconomic background in association with the quality of their critical thinking and writing when they entered a higher education institution. We focused on the socioeconomic characteristics of their childhood home, namely the parents’ education and scholarly culture. Further, we investigated the predictive value of students’ own prior achievements, namely their grades in their native language and mathematics in the National Matriculation Examination. We tested a hypothetical model () that is based on previous research findings.

Figure 1. Hypothetical model of the relations between critical thinking and writing skills, prior academic performance, and socioeconomic background.

Our hypotheses are:

H1. Students who achieved better grades in the Matriculation Examination, show higher quality of critical thinking and writing when they enter higher education (Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Utriainen et al. Citation2017).

H2. Students with higher socioeconomic background, namely students who have highly educated parents and encouraging scholarly culture in their childhood home, show higher quality of critical thinking and writing when they enter higher education (Leino et al. Citation2019; Salmela-Aro and Chmielewski Citation2019; Sikora, Evans, and Kelley Citation2019).

H3. The association between socioeconomic background and critical thinking and writing is not only direct, but also indirect in that higher socioeconomic background influences the quality of critical thinking and writing through the grades in the Matriculation Examination (Arum and Roksa Citation2011).

H4. The associations between socioeconomic background and critical thinking and writing (H2) and the association between academic achievement and critical thinking and writing (H1) are stronger in the students who have chosen advanced Mathematics course compared with students who have chosen basic mathematics course (Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Kaleva et al. Citation2019; Kleemola and Hyytinen Citation2019; Koster and Verhoeven Citation2017).

Materials and methods

Context of the study

Until recently, students have been admitted to Finnish higher education based on their performance in a domain-specific entrance examination or the applicant’s grades in the National Matriculation Examination. Admissions are competitive and only 35% of the applicants are admitted (OECD Citation2019a; Vipunen Citation2020). However, there is variation in competitiveness between disciplines. In addition to selective admissions, only about 40% of Finns have a tertiary degree (Statistics Finland Citation2020), and on average, higher education students have higher educated parents compared to their peers who are not studying in higher education (Kilpi-Jakonen, Erola, and Karhula Citation2016; Nori Citation2011). Therefore, the group of new students in higher education is pre-selected and does not represent the national population. In 2020, procedures in student admissions were reformed and more emphasis was placed on the National Matriculation Examination grades (see Kleemola and Hyytinen Citation2019); however, the participants in the present study were admitted before the reform.

The National Matriculation Examination is the final examination in the general track of the Finnish upper secondary school. Less than half of the age cohorts take the Matriculation Examination (Kivinen and Hedman Citation2017), while many adolescents choose the vocational track that also gives eligibility for higher education. In Matriculation Examination, students take a minimum of four tests (five as of 2022) choosing from among a variety of subjects including the native language, foreign languages, mathematics, and humanities and natural sciences. The test in the native language (Finnish, Swedish, or Sami) is compulsory, and 80% of the students take the test in mathematics (advanced or basic course) (e.g. Kaleva et al. Citation2019). The difference in the mathematics courses is in both content and workload. Students in advanced mathematics take 13 modules with emphasis on mathematical concepts and methods, while students in basic mathematics take eight modules with emphasis on the everyday application of mathematics (Finnish National Agency for Education Citation2015).

Participants and data collection

The data were collected from 18 (of 35) Finnish higher education institutions in 2019, including both research-intensive universities and universities of applied sciences. The data collection was part of a national project, funded by the Ministry of Education and Culture. Each institution was responsible for inviting students and administering the computer-based assessment according to directions provided by the project. Students were invited either via e-mail or by their teachers. In some institutions, participators received small incentives of their participation, such as cinema tickets. Students represented a variety of study fields, including humanities, social sciences, economics, law, natural sciences, engineering, forestry, medicine, nursing, and services. Differences between study fields are not reported as participants were new students in the early stages of their first term, and thus, they were not yet exposed to disciplinary practices. The ethical principles of research with human participants specified by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (Citation2019) were adhered to in the data collection.

As a whole, 1538 first-year students participated in the assessment. This was 25% of the invited students. Sixty-nine students who cut the assessment short were excluded. Further, as we were interested in the impact of the Matriculation Examination grades, we excluded groups that lacked relevant credits. Excluded were the students without a diploma in the Matriculation Examination (n = 269), and students without a grade in mathematics (n = 153). According to reports, the critical thinking performance of these groups is weaker compared to the rest of the sample (Nissinen et al. Citation2021). Finally, 41 students were excluded due to their failing to provide any demographic information. After excluding these groups, 1006 students were included in the analysis; of them, 452 students had a grade in basic mathematics and 554 a grade in advanced mathematics. In this subsample, students’ mean age was 22.39 (SD 4.75, Min 18, Max 64). This is representative of first-year students in Finland (Vipunen Citation2020), who are older than most of their European peers when they enter higher education. Students self-reported their gender: 52% reported they were female, 46% male, and 2% other. Female students were slightly underrepresented compared to average higher education students (Vipunen Citation2020).

Measures

Prior academic performance was measured using students’ self-reported grades in the Matriculation Examination in the native language and mathematics. The grades of the Matriculation Examination are granted in Latin phrases that were transformed onto a numeric, five-point scale for the purposes of the analysis. The two highest grades (laudatur and eximia cum laude approbatur) were recoded as 5, magna cum laude approbatur was recoded as 4, cum laude approbatur was recoded as 3, and two lowest passed grades (lubenter approbatur and approbatur) were recoded as 2. Finally, the failed grade (improbatur) was recoded as 1. The failed grades are included as they can be compensated with good grades in other subjects, and the student can still complete the examination. In addition, their course choice in mathematics was coded as basic or advanced. While there are questions about the reliability of self-reported grades, Cole and Gonyea (Citation2010) have found that self-reported grades mostly match up with the actual ones.

Socioeconomic background was measured using self-reported information about students’ parents’ education and scholarly culture. Education of primary parent was measured on a seven-point ordinal scale: 1 (primary school), 2 (lower secondary school), 3 (upper secondary school or vocational training), 4 (special vocational qualification), 5 (bachelor’s degree), 6 (master’s degree), 7 (licentiate’s or doctoral degree). Scholarly culture was measured by books at the student’s childhood home on a six-point ordinal scale: 1 (0–10 books), 2 (11–25), 3 (26–100), 4 (101–200), 5 (201–500), 6 (more than 500 books). Questions about the reliability of self-reported socioeconomic background have been raised in children, while it is assumed that adults report this information more reliably (e.g. Engzell and Jonsson Citation2015; Lehti and Laaninen Citation2021).

The ordinal scales for prior academic performance and socioeconomic background were treated as continuous variables as they included five or more categories (Rhemtulla, Brosseau-Liard, and Savalei Citation2012).

The quality of students’ critical thinking and writing was assessed using parts of the CLA+ International (Collegiate Learning Assessment) (e.g. Aloisi and Callaghan Citation2018). CLA+ International is a computer-based performance assessment that is designed to assess higher education students’ critical thinking and written communication skills (Klein et al. Citation2007; Shavelson Citation2010). It has been used in higher education to assess critical thinking in the USA, Italy, Chile, and Great Britain. CLA+ International consists of an open-ended performance task and multiple-choice tasks. Recent studies have raised questions about the validity and reliability of the multiple-choice section and its ability to capture critical thinking (Aloisi and Callaghan Citation2018; Hyytinen et al. Citation2021; Kleemola, Hyytinen, and Toom Citation2021). In the present study, we used the performance task which, according to studies, activates cognitive processes relevant to critical thinking and writing (Hyytinen et al. Citation2021). Therefore, it functions as a standalone instrument for the assessment of critical thinking and writing without a multiple-choice section. The performance task was an open-ended task in which students were asked to solve a problem concerning different life expectancies in two cities based on materials they were provided in a document library. Materials included five documents that varied in their reliability. These documents were a blog post, a podcast transcript, a memorandum, a newspaper article, and an infographic. The task did not require any prior knowledge on the topic. Students were asked to solve the problem and give recommendations for action as a written essay. Students had 60 min to complete the task.

Students’ written responses were subsequently scored for critical thinking and writing. Three components of critical thinking and writing were evaluated from the responses. Analysis and Problem Solving focused on students’ skills in using, analysing, and evaluating the provided information and reaching a conclusion. Writing Effectiveness focused on students’ ability to elaborate and to provide arguments that are well constructed and logical. Writing Mechanics was a measure for students’ ability to produce well-structured and grammatically correct text. Two independent scorers analysed each of the responses. All authors participated in scoring, and responses were randomly assigned to scorers. A scoring rubric (see Appendix 1) was used to evaluate students’ responses in each of the three above-mentioned components on a scale from one to six and a N/A option for empty or otherwise unscorable responses. The scorers were trained in the interpretation of the scoring rubric to ensure consistent scoring (Borowiec and Castle Citation2019; Shavelson, Baxter, and Gao Citation1993).

Agreement between the two scorers was overall good (Analysis and Problem Solving r = .73, Writing Effectiveness r = .72, Writing Mechanics r = .71). Consistency was further ensured by monitoring the scoring to pinpoint cases where the difference in the sum of scores in the three components was more than two points between the scorers. These responses were directed to a third scorer for evaluation. A third scorer was brought in in about 6% of cases. The third scorer was able to resolve all these cases, meaning that an agreement of two points or less was achieved. The discrepant scorer’s score was then dropped. This procedure further strengthened the inter-rater reliability.

Internal structure of the CLA+ International has been studied in detail elsewhere, indicating that the three components of the performance task load on a latent variable of critical thinking and writing (Kleemola, Hyytinen, and Toom Citation2021; see also ). Descriptive values for all measures in the two mathematics course choice groups (advanced and basic) are presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive values for used measures in two mathematics course choice groups.

Data analyses

The hypothesized model () was tested using structural equation modelling (SEM) with Mplus version 8.4 (Muthén and Muthén Citation2017). First, the moderation effect of each student’s course choice in mathematics (H4) was tested. The χ2 difference test and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) difference test were conducted with both groups of students, comparing an unconstrained model and a model with constrained coefficients. The CFI difference test complements the χ2 difference test as it is not sensitive to a large sample size (Meade, Johnson, and Braddy Citation2008). In the CFI difference test, a cut-off point was set at .002 (see Meade, Johnson, and Braddy Citation2008). Fit indices were examined to determine goodness-of-fit of the model in both groups using the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), CFI, Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) (Hu and Bentler Citation1998, Citation1999). Direct and indirect effects were examined to determine predictors of critical thinking and writing (H1–H3).

Results

The goodness-of-fit of the hypothesized model () was first tested in the groups of students with a different mathematics course choice (advanced or basic). A good fit was indicated in both groups (advanced: RMSEA = .07, CFI = .98, TLI = .94, SRMR = .03; basic: RMSEA = .08, CFI = .97, TLI = .93, SRMR = .03). A χ2 and a CFI difference test were conducted between an unconstrained model and a model with constrained coefficients. While the χ2 difference test was non-significant (p = .840), the CFI difference test was at the cut-off point (ΔCFI = .002), indicating that the groups differ slightly. Further tests of partial invariance, unconstraining coefficients path by path pinpointed the difference to socioeconomic variables. Releasing all paths related to parents’ education, the difference decreased (ΔCFI = .001), and further releasing the paths related to scholarly culture the difference disappeared (ΔCFI = .000). The χ2 difference test remained non-significant which is not surprising due to the large sample size. The difference between the groups is not substantial. However, it could be concluded that mathematics course choice slightly moderates the associations that socioeconomic background has with prior academic performance and critical thinking and writing. Thus, H4 can be confirmed in part. As far as associations between prior academic performance and critical thinking and writing are concerned, H4 is refuted, as the mathematics course choice does not have moderating effect in that part of the model.

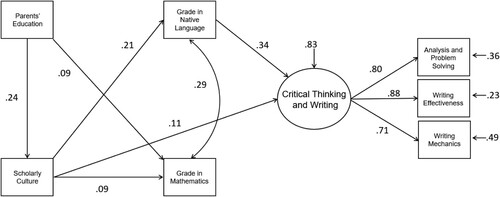

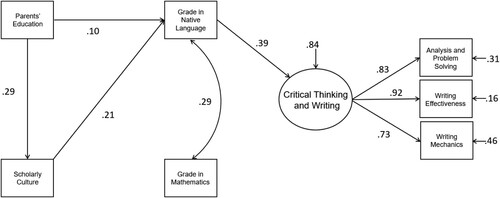

Due to the detected small differences between the groups, further analyses were conducted separately in both groups. To examine associations between students’ socioeconomic background, academic performance, and critical thinking and writing (H1–H3), direct and indirect effects between the variables were examined. All significant direct effects are presented in and for respective groups. Unstandardized estimates are reported in Appendix 2. In both groups, the grade in the native language significantly predicted critical thinking and writing. Conversely, the grade of mathematics did not predict critical thinking and writing in either group. Therefore, H1 is confirmed as far as native language is concerned but refuted for mathematics.

Figure 2. Significant (p < .05) standardized regression coefficients in the model for students with advanced mathematics course choice.

Figure 3. Significant (p < .05) standardized regression coefficients in the model for students with basic mathematics course choice.

Parents’ education did not directly predict critical thinking and writing in either group. However, in the advanced mathematics group, parents’ education had a just significant total effect (β = .09, p = .050) on critical thinking and writing via the scholarly culture (β = .03, p = .031) and the scholarly culture and the grade in the native language (β = .02, p = .001). In the basic mathematics group, parents’ education did not have a significant total effect on critical thinking and writing. Next, the scholarly culture was examined. It had a significant direct effect () on critical thinking and writing in the advanced mathematics group but not in the basic mathematics group. Further, the scholarly culture had a significant indirect effect on critical thinking and writing in both groups via the grade in native language (advanced β = .07 p < .001; basic β = .08, p < .001.). Thus, the total effect was strong (advanced β = .18 p < .001; basic β = .11, p = .030). Consequently, the findings partly confirm H2. While scholarly culture predicts critical thinking and writing in both groups, parents’ education has only a very limited effect and only in the advanced mathematics group. Additionally, findings give partial support for H3, confirming the mediating effect of the grade in native language between scholarly culture and critical thinking and writing in both groups and between parents’ education and critical thinking and writing in the advanced mathematics group. What stands out is that the grade in mathematics has no significant effect on critical thinking and writing and no mediating effect between socioeconomic variables and critical thinking and writing in either group.

The model predicts 16% of critical thinking and writing indicating that there are many more unknown predictors of critical thinking and writing.

Discussion

The findings give support to earlier research that had concluded that new higher education students’ critical thinking and writing could be predicted by their prior academic performance and socioeconomic background (e.g. Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Utriainen et al. Citation2017). However, not all prior performance and socioeconomic background have equal predictive value.

Our hypothesis (H1) about the National Matriculation Examination grades being a predictor of critical thinking and writing in new higher education students was partly confirmed (cf. Arum and Roksa Citation2011; Utriainen et al. Citation2017). Student’s grade in native language predicted their critical thinking and writing strongly. This is understandable, as the native language test requires similar skills as critical thinking and writing in the present assessment (Matriculation Examination Board Citation2020). Conversely, a student’s grade in mathematics did not predict critical thinking and writing.

Earlier research indicated that socioeconomic background could be an important predictor of new students’ critical thinking and writing, particularly indirectly through prior academic performance (e.g. Arum and Roksa Citation2011). The present study found only partial evidence of this in Finland (H2, H3). Parents’ education did not have a significant effect on most students’ critical thinking and writing performance, contrary to international studies (Arum and Roksa Citation2011), and recent developments in the Finnish students’ PISA performance (Leino et al. Citation2019; Salmela-Aro and Chmielewski Citation2019). However, differences in the target population of PISA and the present assessment are noteworthy and may be the reason for the lack of impact of parents’ education. While PISA samples the whole age cohort, the present study focused on students who have already been admitted to higher education and they are a selected group with more highly educated parents compared to the general population (e.g. Kilpi-Jakonen, Erola, and Karhula Citation2016). The fact that the differences in socioeconomic background are small within the group is most likely the reason behind the missing impact of parental education. Nevertheless, the scholarly culture of the childhood home was found to be very important for students’ critical thinking and writing with the grade of the native language as a mediator, giving partial support to H2 and H3. This finding is in line with many earlier studies that have found significant effects of scholarly culture in different stages of educational paths (Cheung and Andersen Citation2003; Evans, Kelley, and Sikora Citation2014; Evans et al. Citation2010; OECD Citation2019b; Sikora, Evans, and Kelley Citation2019). Encouraging children to read and learn has repeatedly been promoted, and the present findings confirm far-reaching benefits of such support. In the light of such robust findings, it should be considered whether educational institutions could develop practices to support children who do not have a scholarly home culture.

While the grade in mathematics had no significant influence on new students’ critical thinking and writing, it was found that there was a slight difference in the associations between the students who had a grade in advanced mathematics and the students who had a grade in basic mathematics (H4). Surprisingly, this difference could not be traced back to different contents of each course in contrast to suggestions from earlier studies (e.g. Kaleva et al. Citation2019). Instead, the difference was found in the students’ socioeconomic background. The present data and analyses cannot explain the reasons behind this finding. However, an explanation could be the fact that a higher parental education level has been found to be associated with stronger skills in mathematics (Metsämuuronen Citation2017). Students with stronger skills are more likely to choose a more demanding course such as advanced mathematics. Highly educated parents might also encourage their children to make more challenging course choices. More research is needed to understand the mechanics between the mathematics choices, skills, and perceived value. Furthermore, it is important to observe changes in such mechanics: changes in admissions criteria might influence earlier educational choices. For instance, perceived emphasis on more demanding courses in admission criteria could encourage students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds to make different choices. Nevertheless, the same may be said about students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds, who additionally have the advantage of their parents’ knowledge and support.

Developers of admissions gain several practical insights of the study. The findings give some support for using Matriculation Examination grades, particularly the grade in the native language, in student admissions. Questions remain concerning the significance of the grade in mathematics. If the assessment would have required more statistical and mathematical reasoning, the findings could have been different. Consequently, policymakers, higher education institutions, and disciplines in Finland but also across Europe, need to consider which skills are necessary for their new students. In this way, they can focus their efforts on developing admissions criteria that ensure the preparedness of students. In this process, it is important to differentiate between skills and knowledge. A test that is designed to assess subject-specific knowledge, such as the contents of the upper secondary school curriculum, does not necessarily require relevant skills. Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that a diagnostic assessment cannot predict the potential of students; development of critical thinking and writing in the higher education is possible with proper instruction (e.g. Heijltjes et al. Citation2014). Students with weaker performance in prior education could benefit from additional support in their critical thinking and writing. They could benefit from, for instance, feedback and opportunities to practice their skills in authentic contexts.

The study is limited in that it focuses on critical thinking and writing, leaving other skills such as quantitative reasoning aside. However, critical thinking is a complex set of cognitive skills, including analysis, problem solving, and argumentation. It is an important competency in the preparedness of students who are undergoing the transition to higher education (e.g. Arum and Roksa Citation2011).

It must be noted that the effect size of the explored model was not very strong. This indicates that there are many unknown factors in that predict students’ critical thinking and writing that future research should explore. Some of these predictors may be situational: students’ motivation to participate the test, their emotions, and their effort to regulate their performance are likely to influence the outcome (Hyytinen et al. Citation2021). Prior learning environments may have characteristics that develop critical thinking and writing skills while not effecting the Matriculation Examination grades. Some teachers in secondary education may emphasize critical thinking while others may focus strictly on the knowledge and skills that the Matriculation Examination requires. Furthermore, the study design may be the reason behind the weak effect of socioeconomic background on critical thinking and writing, as the admitted students have little differences in their socioeconomic background. Children of highly educated parents may have more resources to tackle changes student admissions, and thus have an advantage over their peers. It may also be that parents’ education simply has more influence on educational choices than skills. To understand more profoundly the socioeconomic effects and their interaction with skill development on the educational path towards higher education, more research is needed. A longitudinal study on generic skills development and background variables, such as socioeconomic background and learning environments, should be designed and implemented. To gain a more extensive view on the predictive value of prior academic performance, future research should consider testing a wider range of skills that are relevant to preparedness for higher education. Performance tasks could be designed to emphasize more quantitative reasoning and other skills.

The socioeconomic background and prior academic performance matter in the quality of critical thinking and writing in new higher education students in Finland. Further research needs to aim for revealing more about the predictors of this complex skill. In addition, it is reasonable to use prior academic performance as an admission criterion in higher education. However, such criterion should not be considered free of inequities. While the study focuses on the Finnish context, the findings give insights into the development of student admissions elsewhere as well.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Council for Aid to Education (CAE) for providing the CLA+ International, the participating institutions for administering the assessments and recruiting participants, and the Kappas project team for their efforts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katri Kleemola

Katri Kleemola is a researcher at the Centre for University Teaching and Learning in University of Helsinki. Katri's research focuses on critical thinking, argumentative writing, and other generic skills in transition to higher education.

Heidi Hyytinen

Heidi Hyytinen is a Senior Lecturer in Higher Education at the Centre for University Teaching and Learning in University of Helsinki. Heidi's research focuses on generic skills, performance-based assessment, self-regulation, and pedagogy in higher education.

Auli Toom

Auli Toom is a Professor of Higher Education and the director of the Centre for University Teaching and Learning in University of Helsinki. Auli's research focuses on teacher education, teacher knowing, professional agency, generic skills, and pedagogy in higher education.

References

- Aloisi, C., and A. Callaghan. 2018. “Threats to the Validity of the Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA) as a Measure of Critical Thinking Skills and Implications for Learning Gain.” Higher Education Pedagogies 3 (1): 57–82.

- Arum, R., and J. Roksa. 2011. Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Badcock, P., P. Pattison, and K.-L. Harris. 2010. “Developing Generic Skills Through University Study: A Study of Arts, Science and Engineering in Australia.” Higher Education 60 (4): 441–458.

- Borowiec, K., and C. Castle. 2019. “Using Rater Cognition to Improve Generalizability of an Assessment of Scientific Argumentation.” Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation 24 (1): 8.

- Cheung, S., and R. Andersen. 2003. “Time to Read: Family Resources and Educational Outcomes in Britain.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 34: 413–433.

- Chiu, M. 2016. “Socio-Economic Status, Inequality and Academic Achievement.” In Socioeconomic Status: Influences, Disparities and Current Issues, edited by Geoffrey Perkins, 1–26. New York: Nova Publishers.

- Cole, J., and R. Gonyea. 2010. “Accuracy of Self-Reported SAT and ACT Test Scores: Implications for Research.” Research in Higher Education 51 (4): 305–319.

- De Graaf, P. 1986. “The Impact of Financial and Cultural Resources on Educational Attainment in the Netherlands.” Sociology of Education 59 (4): 237–246.

- Engzell, P., and J. Jonsson. 2015. “Estimating Social and Ethnic Inequality in School Surveys: Biases from Child Misreporting and Parent Nonresponse.” European Sociological Review 31 (3): 312–325. doi:10.1093/esr/jcv005.

- Evans, M. D. R., and J. Kelley. 2002. “Cultural Resources and Educational Success: The Beaux Arts vs Scholarly Culture.” In Australian Economy and Society 2001: Education, Work, and Welfare, edited by M. D. R. Evans and J. Kelly, 55–65. Leichhardt: Federation Press.

- Evans, M. D. R., J. Kelley, and J. Sikora. 2014. “Scholarly Culture and Academic Performance in 42 Nations.” Social Forces 92 (4): 1573–1605.

- Evans, M. D. R., J. Kelley, J. Sikora, and D. Treiman. 2010. “Family Scholarly Culture and Educational Success: Books and Schooling in 27 Nations.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 28 (2): 171–197.

- Evens, M., A. Verburgh, and J. Elen. 2013. “Critical Thinking in College Freshmen: The Impact of Secondary and Higher Education.” International Journal of Higher Education 2 (3): 139–151.

- Facione, P. 1990. Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction. Newark: American Philosophical Association.

- Finlex. 2019. “Laki ylioppilastutkinnosta.” https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2019/20190502.

- Finnish National Agency for Education. 2015. Lukion opetussuunnitelman perusteet. Helsinki: Finnish National Agency for Education.

- Finnish National Board on Research Integrity. 2019. The Ethical Principles of Research with Human Participants and Ethical Review in the Human Sciences in Finland. Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK: Helsinki.

- Halpern, D. 2014. Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking. 5th ed. London: Psychology Press.

- Haltia, N., U. Isopahkala-Bouret, and A. Jauhiainen. 2019. “Korkeakoulujen opiskelijavalintauudistus ja aikuisopiskelijan opiskelumahdollisuudet.” Aikuiskasvatus 39 (4): 276–289. doi:10.33336/aik.88081.

- Heijltjes, A., T. van Gog, J. Leppink, and F. Paas. 2014. “Improving Critical Thinking: Effects of Dispositions and Instructions on Economics Students’ Reasoning Skills.” Learning and Instruction 29: 31–42. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.07.003.

- Heiskala, L., J. Erola, and E. Kilpi-Jakonen. 2021. “Compensatory and Multiplicative Advantages: Social Origin, School Performance, and Stratified Higher Education Enrolment in Finland.” European Sociological Review 37 (2): 171–185.

- Hu, L., and P. Bentler. 1998. “Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification.” Psychological Methods 3 (4): 424.

- Hu, L., and P. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling 6 (1): 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Hyytinen, H., A. Toom, and L. Postareff. 2018. “Unraveling the Complex Relationship in Critical Thinking, Approaches to Learning and Self-Efficacy Beliefs among First-Year Educational Science Students.” Learning and Individual Differences 67: 132–142.

- Hyytinen, H., A. Toom, and R. Shavelson. 2019. “Enhancing Scientific Thinking Through the Development of Critical Thinking in Higher Education.” In Redefining Scientific Thinking for Higher Education, edited by M. Murtonen and K. Balloo, 59–78. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-24215-2_3.

- Hyytinen, H., and A. Toom. 2019. “Developing a Performance Assessment Task in the Finnish Higher Education Context: Conceptual and Empirical Insights.” British Journal of Educational Psychology (89): 551–563. doi:10.1111/bjep.12283.

- Hyytinen, H., J. Ursin, K. Silvennoinen, K. Kleemola, and A. Toom. 2021. “The Dynamic Relationship Between Response Processes and Self-Regulation in Critical Thinking Assessments.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 71. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101090.

- Jerrim, J., L. Volante, D. Klinger, and S. Schnepf. 2019. “Socioeconomic Inequality and Student Outcomes Across Education Systems.” In Socioeconomic Inequality and Student Outcomes: Cross-National Trends, Policies, and Practices, edited by L. Volante, S. Schnepf, J. Jerrim, and D. Klinger, 3–16. Singapore: Springer Singapore. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-9863-6_1.

- Kaleva, S., J. Pursiainen, M. Hakola, J. Rusanen, and H. Muukkonen. 2019. “Students’ Reasons for STEM Choices and the Relationship of Mathematics Choice to University Admission.” International Journal of STEM Education 6 (1): 43. doi:10.1186/s40594-019-0196-x.

- Kallio, E., J. Utriainen, M. Niilo-Rämä, and E. Räikkönen. 2018. “Lukiomenestyksen ja yliopisto-opintojen aloitushetken iän yhteys yliopisto-opinnoissa menestymiseen ja opintojen etenemiseen: seurantatutkimus.” Kasvatus 49 (4): 287–296.

- Kauppinen, M., and J. Marjanen. 2020. Millaista on yhdeksäsluokkalaisten kielellinen osaaminen? Suomen kielen ja kirjallisuuden oppimistulokset perusopetuksen päättövaiheessa 2019. Helsinki: Kansallinen koulutuksen arviointikeskus KARVI.

- Kilpi-Jakonen, E., J. Erola, and A. Karhula. 2016. “Inequalities in the Haven of Equality? Upper Secondary Education and Entry Into Tertiary Education in Finland.” In Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality, edited by H.-P. Blossfeld, S. Buchholz, J. Skopek, and M. Triventi, 181–195. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kivinen, O., and J. Hedman. 2017. “Ylioppilastutkinnon suorittaneiden ikäluokkaosuudet laskussa”. https://blogit.utu.fi/utu/2017/02/07/ylioppilastutkinnon-suorittaneiden-ikaluokkaosuudet-laskussa/.

- Kleemola, K., and H. Hyytinen. 2019. “Exploring the Relationship Between Law Students’ Prior Performance and Academic Achievement at University.” Education Sciences 9 (3): 236.

- Kleemola, K., H. Hyytinen, and A. Toom. 2021. “Exploring Internal Structure of a Performance-Based Critical Thinking Assessment for New Students in Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–14. doi:10.1080/02602938.2021.1946482.

- Klein, S., R. Benjamin, R. Shavelson, and R. Bolus. 2007. “The Collegiate Learning Assessment: Facts and Fantasies.” Evaluation Review 31 (5): 415–439.

- Klemenčič, M. 2018. “European Higher Education in 2018.” European Journal of Higher Education 8 (4): 375–377. doi:10.1080/21568235.2018.1542238.

- Koster, A., and N. Verhoeven. 2017. “Study Success in Science Bachelor Programmes: Predictive Value of Secondary School Grades.” In Higher Education Transitions: Theory and Research, edited by E. Kyndt, V. Donche, K. Trigwell, and S. Lindblom-Ylänne, 84–102. London: Routledge.

- Kuhn, D. 2005. Education for Thinking. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Kuhn, D. 2019. “Critical Thinking as Discourse.” Human Development 62 (3): 146–164.

- Leest, B., and M. Wolbers. 2021. “Critical Thinking, Creativity and Study Results as Predictors of Selection for and Successful Completion of Excellence Programmes in Dutch Higher Education Institutions.” European Journal of Higher Education 11 (1): 29–43. doi:10.1080/21568235.2020.1850310.

- Lehti, H., and M. Laaninen. 2021. “Perhetaustan yhteys oppimistuloksiin Suomessa PISA-ja rekisteriaineistojen valossa.” Yhteiskuntapolitiikka 86 (5–6): 520–532.

- Leino, K., A. Ahonen, N. Hienonen, J. Hiltunen, M. Lintuvuori, S. Lähteinen, J. Lämsä, et al. 2019. PISA 18 Ensituloksia. Helsinki: Ministry of Education and Culture.

- Lindblom-Ylänne, S., K. Lonka, and E. Leskinen. 1996. “Selecting Students for Medical School: What Predicts Success During Basic Science Studies? A Cognitive Approach.” Higher Education 31 (4): 507–527.

- Marks, G. 2011. “Issues in the Conceptualisation and Measurement of Socioeconomic Background: Do Different Measures Generate Different Conclusions?” Social Indicators Research 104 (2): 225–251.

- Marks, G. 2014. Education, Social Background and Cognitive Ability: The Decline of the Social. New York: Routledge.

- Matriculation Examination Board. 2020. Äidinkielen ja kirjallisuuden kokeen määräykset. Vol. 2020.

- McClelland, D. 1973. “Testing for Competence Rather Than for ‘Intelligence.” American Psychologist 28 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1037/h0034092.

- Meade, A., E. Johnson, and P. Braddy. 2008. “Power and Sensitivity of Alternative Fit Indices in Tests of Measurement Invariance.” Journal of Applied Psychology 93 (3): 568.

- Metsämuuronen, J. 2017. Oppia ikä kaikki – matemaattinen osaaminen toisen asteen koulutuksen lopussa 2015. Helsinki: Kansallinen koulutuksen arviointikeskus KARVI.

- Muthén, L., and B. Muthén. 2017. Mplus User’s Guide. 8th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nissinen, K., J. Ursin, H. Hyytinen, and K. Kleemola. 2021. “Higher Education Students’ Generic Skills.” In Assessment of Undergraduate Students’ Generic Skills in Finland: Findings of the Kappas! Project, edited by J. Ursin, H. Hyytinen, and K. Silvennoinen, 39–82. Helsinki: Ministry of Education and Culture.

- Nori, H. 2011. Keille yliopiston portit avautuvat? Tutkimus suomalaisiin yliopistoihin ja eri tieteenaloille valikoitumisesta 2000-luvun alussa. Turku: University of Turku.

- O’Hare, L., and C. McGuinness. 2015. “The Validity of Critical Thinking Tests for Predicting Degree Performance: A Longitudinal Study.” International Journal of Educational Research 72: 162–172.

- OECD. 2019a. Education at a Glance 2019. OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2019b. PISA 2018 Results (Volume II). Where All Students Can Succeed. Paris: OECD.

- Orr, D., A. Usher, C. Haj, G. Atherton, and I. Geanta. 2017. Study on the Impact of Admission Systems on Higher Education Outcomes. Volume I: Comparative Report. European Union.

- Rhemtulla, M., P. Brosseau-Liard, and V. Savalei. 2012. “When Can Categorical Variables Be Treated as Continuous? A Comparison of Robust Continuous and Categorical SEM Estimation Methods Under Suboptimal Conditions.” Psychological Methods 17 (3): 354–373. doi:10.1037/a0029315.

- Richardson, M., C. Abraham, and R. Bond. 2012. “Psychological Correlates of University Students’ Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 138 (2): 353–387. doi:10.1037/a0026838.

- Salmela-Aro, K., and A. Chmielewski. 2019. “Socioeconomic Inequality and Student Outcomes in Finnish Schools.” In Socioeconomic Inequality and Student Outcomes. Cross-National Trends, and Practices, edited by L. Volante, S. Schnepf, J. Jerrim, and D. Klinger, 153–168. Singapore: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-9863-6_9.

- Shavelson, R. 2010. Measuring College Learning Responsibly: Accountability in a New Era. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Shavelson, R., G. Baxter, and X. Gao. 1993. “Sampling Variability of Performance Assessments.” Journal of Educational Measurement 30 (3): 215–232.

- Shavelson, R., O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, K. Beck, S. Schmidt, and J. Marino. 2019. “Assessment of University Students’ Critical Thinking: Next Generation Performance Assessment.” International Journal of Testing, 1–20. doi:10.1080/15305058.2018.1543309.

- Sikora, J., M. D. R. Evans, and J. Kelley. 2019. “Scholarly Culture: How Books in Adolescence Enhance Adult Literacy, Numeracy and Technology Skills in 31 Societies.” Social Science Research 77: 1–15.

- Statistics Finland. 2020. “Educational Structure of Population.” Official Statistics of Finland (OSF).

- Steenman, S. 2018. “Alignment of Admission. An Exploration and Analysis of the Links Between Learning Objectives and Selective Admission to Programmes in Higher Education.” Utrecht University.

- Tikkanen, J. 2019. “Parental School Satisfaction in the Context of Segregation of Basic Education in Urban Finland.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 5 (3): 165–179. doi:10.1080/20020317.2019.1688451.

- Utriainen, J., M. Marttunen, E. Kallio, and P. Tynjälä. 2017. “University Applicants’ Critical Thinking Skills: The Case of the Finnish Educational Sciences.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 61 (6): 629–649.

- van der Zanden, P., E. Denessen, A. Cillessen, and P. Meijer. 2019. “Patterns of Success: First-Year Student Success in Multiple Domains.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (11): 2081–2095. doi:10.1080/03075079.2018.1493097.

- Vipunen. 2020. “Education Statistics Finland.” https://vipunen.fi/en-gb/home.

- Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., R. Shavelson, S. Schmidt, and K. Beck. 2019. “On the Complementarity of Holistic and Analytic Approaches to Performance Assessment Scoring.” British Journal of Educational Psychology (89): 468–484. doi:10.1111/bjep.12286.