ABSTRACT

The supervision of degree theses is one of several institutional practices in higher education that are regulated by various systems of rules. However, the social roles involved in the practices may still be largely based on interpretation, negotiation and personal choice. Research on supervision has primarily targeted the doctoral level, but the present study targets the Bachelor level. Existing inventories of roles are based on supervisor roles, but the present study also includes student roles. Existing inventories are not always based on empirical data, but the present study uses focus group discussions with supervisors and responses to open-ended questions from a questionnaire to students as a basis for extracting supervisor and student roles. The supervisor and student participants came from two language departments at a Swedish university. The local guidelines relevant to supervision underspecify roles. The findings show a considerable complexity and a broad repertoire when it comes to roles attributed to supervisors as well as students. Some roles may be plotted along a scale, where stakeholders may have different preferences and needs, such as along transactional and interactional types, or between support and management; or between seeing the thesis primarily as a process or a product.

1. Introduction

The university as a social institution involves different roles and relations, not least teacher-student, where different stakeholders have potentially different views on what the different roles entail and how they should be performed. An institutional or professional ‘role’ may refer to behavioural patterns that are expected of a particular social status or position (cf. Mellado Citation2019, 4).Footnote1 Knowledge and practices surrounding roles may be largely implicit and tacit—and hence subject to interpretation and negotiation. This article is focused on how the parties involved view the roles of supervisor and student in the context of thesis supervision. We distinguish between a plurality of roles, linked to practices and beliefs, which participants in thesis supervision can choose to adopt or reject, with varying degrees of awareness. Many studies have shown that the supervisor-student relationship is seen as very important (e.g. Derounian Citation2011; Todd et al. Citation2004). We hope that the analysis of roles will provide a basis for discussing practices, identifying different understandings, and ultimately improving supervision processes.

Focusing on the Bachelor level, the study adds to the relatively limited body of research on undergraduate thesis supervision (see e.g. Roberts and Seaman Citation2018), which is in contrast to the extensive scope of previous research at the doctoral level (Stappenbelt and Basu Citation2019). There are indications that the Bachelor thesis is spreading in European higher education, which adds to the relevance of the present study.

When considering the roles of supervisors and students, the functions of the thesis also need to be considered. It is typically based on inquiry-based learning (e.g. Ashwin, Abbas, and McLean Citation2017). It involves generic research skills, but it also needs to be understood as engaging with disciplinary knowledge specifically (Ashwin, Abbas, and McLean Citation2017), helping to socialise the student in a disciplinary community. A Bachelor thesis may vary in its orientation towards theory and practice. While universal characteristics of the Bachelor thesis seem to exist (see Meeus, Van Looy, and Libotton Citation2004, 304), there is likely to be variation in local regulations and practices. We also see a need for raising awareness about contextual factors that may influence the perceptions and implementations of roles.

The material consists of focus group discussions with supervisors and responses to open-ended questions from a questionnaire to BA degree thesis students. The supervisors and students who participated in the study come from two language departments at a university in Sweden, specialising in Linguistics and Literary Studies. In order to investigate how teachers and students view thesis supervision at the Bachelor level, we pose the research question ‘What supervisor and student roles can be extracted from the focus group and questionnaire data?’. To help contextualise these institutional roles, we refer to official documents/guidelines that apply to the Swedish context (section 3). This information is important as it shows that student and supervisor roles are far from well-defined, which is likely to lead to varying practices based on individual preferences rather than on principles informed by research.

2. Previous research on roles in thesis supervision

There is a substantial body of research on supervision in higher education targeting the doctoral and Master levels. There are some previous studies on undergraduate essay supervision but none of them focus on roles the way we do. Previous work that has approached supervision based on roles has focused on the role of the supervisor. We have found no analyses of student roles, nor of the roles of the supervisor’s colleagues, in the context of thesis supervision.

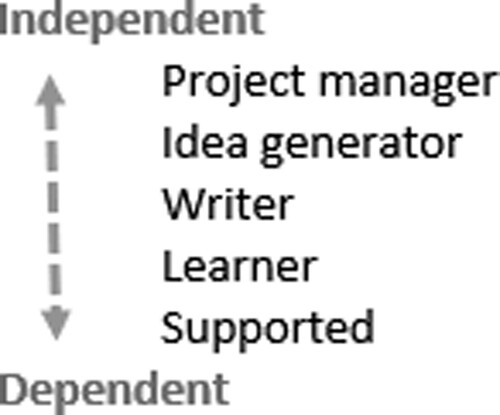

Regarding student roles, many existing studies do not analyse roles as such, but investigate abstract qualities, such as the notion of student independence, which is highly relevant for supervision (e.g. Lee Citation2008). In a study of the undergraduate level, Magnusson and Zackariasson (Citation2019) found that supervisors saw themselves as guiding students, but they expected students to take responsibility for aspects such as initiating discussions, making justified choices, taking feedback into account without necessarily doing exactly as suggested; they also expected students to attend to practical considerations, such as meeting deadlines and formatting texts correctly. However, the findings also uncovered great variation in how student independence was understood by the supervisors, who participated across two disciplines and in two different countries.

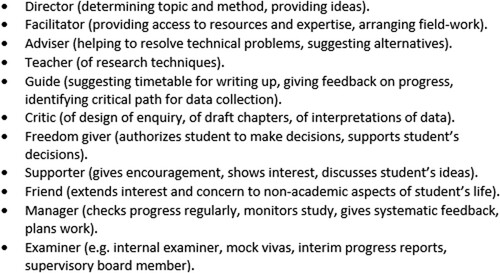

When roles in supervision are discussed in the literature, it is the supervisor’s roles towards the student that are in focus. The different roles of the supervisor are occasionally brought up also in textbooks, such as Brown and Atkins (Citation1988, 120), who provide a list of supervisor roles at the doctoral level. Their list, shown in , is described as ‘roles which you can take as supervisor’. With eleven roles, a splitting rather than a lumping approach to categorisation is taken; there may be overlap between some of the roles included, at the same time as we are offered finer details regarding what may be involved in the overall institutional roles.

Figure 1. Supervisor roles at the doctoral level (Brown and Atkins Citation1988).

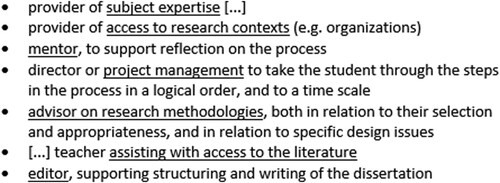

Another relatively extensive list of roles is found in Rowley and Slack (Citation2004, 179). As in Brown and Atkins (Citation1988), the roles are not the result of an empirical study. Unlike Brown and Atkins (Citation1988), the roles refer to the undergraduate and not the doctoral context. shows the ‘roles that a supervisor might potentially adopt’, from Rowley and Slack (Citation2004; emphasis added).

Figure 2. Supervisor roles at the undergraduate level (Rowley and Slack Citation2004).

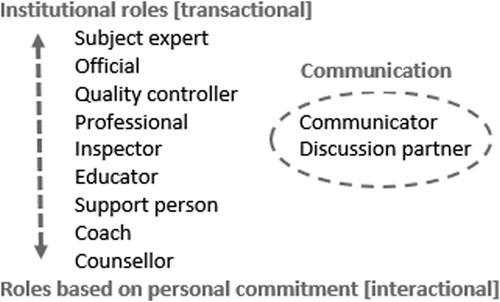

There is some overlap between the roles in the two lists, even if the labels differ. attempts to illustrate the overlap, with the roles laid out on a scale from transactional to interactional. This reflects the supervisor’s choice of doing supervision in a largely transactional way (adopting roles at the top) or in a relatively more interactional way (adopting roles at the bottom). Choices may be linked to various factors: for example, the interactional roles Supporter and Friend are included for the doctoral level [B&A], but not for the undergraduate level [R&S], perhaps due to lack of time to develop personal relationships. Research on the doctoral level has stressed the importance of a good interpersonal relationship between supervisor and student (e.g. Seeber and Horta Citation2021), suggesting that interactional roles may be especially relevant here.

Work that is based on empirical material tends to present relatively few supervisor roles, which are often approached from the perspective of different styles or models which are adopted implicitly. A distinction between two key roles is presented in Bégin and Gérard (Citation2013, 272–273), based on previous research. A supervisor acting as a coach explains procedures and helps students develop the skills needed to manage the task on time, while a mentor has a broader mandate to help the student in their future careers. We interpret the coach here as functioning at the transactional end and the mentor at the interactional end.

An example of a study that has identified different supervisor styles is Lönn Svensson (Citation2007, 135), based on interviews with doctoral supervisors in Sweden. The supervisor is described as a researcher, a leader and an official.Footnote2 For the researcher, the primary goal is to give input on a research project; for the leader, it is about leading a project; while for the official, it is about checking the institutional requirements of the doctoral work. The adoption of these roles is said to depend on the supervisor’s relation to the student; the reasons why a teacher chooses to become a supervisor; the power perspective the supervisor takes; and whether it is considered primarily the student’s or the supervisor’s responsibility that the thesis be completed. This dimension can be linked to the Freedom-giver versus Manager roles in , or supervisors taking a predominantly hands-on versus hands-off approach.

The roles of the doctoral supervisor have been described from the perspective of the predominant power relationship between the supervisor and student. Dysthe (Citation2002) makes a distinction between three different roles where status is approached differently: the teaching, the partnership and the apprenticeship models. In the teaching model, the student is dependent on the supervisor to a high degree, as someone who has all the answers. The student submits drafts and receives comments mostly on aspects that need to be corrected or changed. It may be difficult for a student to choose not to adapt the text in accordance with the supervisor’s comments. In the partnership model, the relationship is relatively symmetrical, with dialogue being the key strategy. Comments from the supervisor on written drafts may lead to discussion, as the supervisor attempts to achieve constructive criticism without appropriating the text. The research task is seen as a mutual concern, requiring ‘a joint responsibility’ (Handal and Lauvås Citation2008, 111). The apprenticeship model is based on a master-apprentice type of relationship, with the supervisor sharing practical knowledge of what it means to be a researcher. The supervisor demonstrates how research is done and the student is expected to follow the supervisor’s example. Student texts tend to be discussed in groups, with feedback given by not only the supervisor but additional senior researchers. A wider pool of readers makes the student less dependent on the supervisor’s views.

There may be contextual and cultural differences in the available repertoire of roles for supervisors and in what roles tend to be adopted (e.g. Deuchar Citation2008). In a study set in Russian elite universities, Guzdev, Terentev, and Dzhafarova (Citation2020) found six different supervision styles, labelled superhero, hands-off supervisor, research practice mediator, dialogue partner, mentor and research advisor. The superhero gives a plethora of different kinds of support and advice, which is in contrast to the hands-off supervisor. The other supervisor styles give specific types of support. The research advisor is concerned with the research but less with the doctoral dissertation itself, while the research practice mentor is mostly concerned with the dissertation. Dialogue partners are like consultants who can recommend, advise and comment. Mentors do so, too, but the difference is that mentors help ease the doctoral student into the world of academia.

Issues that may arise given increased internationalisation are brought up e.g. in Guzdev, Terentev, and Dzhafarova (Citation2020); see also Pinto and Araújo e Sá (Citation2020) on the complexities of international supervision, which may be becoming a more common practice. Two of the roles mentioned above stand out as potentially highly context-specific: the official (Lönn Svensson Citation2007), which may be specific to the contexts where universities are a government authority (e.g. Sweden), and the superhero (Guzdev, Terentev, and Dzhafarova Citation2020), which may be specific to (Russian) elite university settings. A relatively general aspect that may be understood and valued differently across cultural contexts is student independence (Magnusson and Zackariasson Citation2019, 1405).

A teaching role is included in some models (Brown and Atkins Citation1988; Dysthe Citation2002), but not in others (Bégin and Gérard Citation2013; Lönn Svensson Citation2007; Guzdev, Terentev, and Dzhafarova Citation2020). This may partly have to do with the level of the thesis. It could be that for doctoral students there is a relatively widespread assumption that they will have already learnt the basics for research. At the Bachelor level, however, there is likely to be a greater need for teacher support. Conversely, a role that is less likely to occur at the Bachelor level is that of mentor (Guzdev, Terentev, and Dzhafarova Citation2020; Bégin and Gérard Citation2013; cf. also Dysthe’s apprenticeship model). It is probably not only the power differential between supervisor and student at that level that makes a mentoring role less likely, but also time constraints in developing this type of relationship.

Summarising research on the Bachelor or Master thesis, Svärd (Citation2013, 93) describes the supervisor as both gatekeeper and co-responsible in the thesis work. Interview studies such as Anderson, Day, and McLaughlin (Citation2006) report that supervisors felt divided. In the role of gatekeeper, they felt they needed to instil the high academic standards expected in their students. Whereas this role was very much shaping/controlling, the role of co-responsible was supporting. Being co-responsible meant they felt a personal commitment to their students’ work. Also testifying to this balancing act, de Kleijn et al. (Citation2012) found that (Master) supervisor control should be carefully balanced and that it is it is important for supervisors to be perceived as highly affiliated.

Existing research on supervision at doctoral/Master levels often stresses that it tends to be unclear how the responsibility between supervisor and student is to be divided (e.g. Belcher Citation1994; Krase Citation2007). In those cases when recommendations are made regarding supervision practice, the point is often made that the division of roles and responsibilities should be discussed and clarified at the outset (e.g. Roberts and Seaman Citation2018), or that supervisors should check with individual students what their preferences are for explicit structuring from the supervisor (de Kleijn et al. Citation2012). This could help avoid tension and conflict, which is a recurrent theme in supervision research.

3. Thesis supervision in a Swedish context

This section describes the local context, as there may be considerable institutional variation (across regions, traditions, disciplines, etc.) in how thesis supervision is done, which likely affects supervision roles. In Sweden, as part of an undergraduate degree in the humanities, students are required to undertake a research project with the support of a supervisor. The results are normally presented as a written thesis at a seminar where the student defends their thesis while an appointed reader (normally a student peer) and examiner (normally a colleague of the supervisor) are invited to ask questions about the quality and validity of the research project. The thesis grade is typically set by the examiner, who is not involved in the supervision, but assesses the final thesis product. The scope and goals of the thesis project are specified in the Swedish Higher Education Act and local policy documents for the universities.

We have analysed official documents from the national and local domains from the perspective of how student and supervisor roles are described in the supervision context. Overall, references to the student and the supervisor are rarely made and most documents do not mention supervision specifically, but rather describe the general requirements for the education. No guidelines exist for supervision at the national level, which means that roles and responsibilities are a matter of interpretation for universities and/or individuals.

A key goal in Swedish higher education is independence (cf. Magnusson and Zackariasson Citation2019). The Swedish Higher Education ActFootnote3 outlines what is expected from students in order for the degree thesis to be passed: they should ‘carry out a piece of independent work’ and ‘identif[y their] need of knowledge and develop [their] competence’. These wordings suggest that the student is seen as a Project Manager (see and ).

Figure 4. The supervisor’s roles organised from predominantly transactional to interactional, in addition to communication-oriented, roles.

In the university’s own policy document for quality in education, different roles attributed to teachers are implicitly described.Footnote4 These may be labelled Inspector, as someone who ‘determines grades’ and ‘ensures that courses are in alignment with programme syllabus’; Educator, as someone who ‘develops syllabi’; Communicator, as someone who functions as a ‘contact person for students, stakeholders and collegial committees’; and Support Person, as someone who ‘when needed establishes an individual study plan for a student’.

In the university’s guidelines for degree theses, there is some mention of the supervisor, student and examiner. The supervisor should be a Subject expert: ‘a qualified and academically competent supervisor who is especially familiar with the [discipline’s] theories, methods and research’. The supervisor’s role as a Discussion Partner is foregrounded, as it says that the student’s choice of topic for the thesis should ‘take place through dialogue with the student and the supervisor’. It is also stated that supervisors should ‘be provided with adequate resources so that they can give students the supervisory support that they are entitled to’, which could be seen as foregrounding what may be called an Employee role, entitled to specific support from the employer. The supervisor is typically given a set number of hours for supervision (about 10–20 hours for a Bachelor thesis). Hence, while the student is expected to show independence, he/she should also be given appropriate conditions for success, with support from the supervisor. It is a matter of interpretation how the balance between the student’s independence and the supervisor’s support should be achieved.

Finally, if we turn to the two language departments where the study is set and consider the syllabi for the degree thesis courses, we find no specifications of what the supervisor and student roles entail. One syllabus does not mention the supervisor at all, but merely the depersonified action of supervision in formulations such as ‘supervision mandatory’. The other syllabus mentions the two roles briefly, stating that ‘the student [should] be able to integrate and use differing viewpoints, from the supervisor as well as from other students’. This presents the supervisor as someone who presents views and who is at the same level as ‘other students’, who are also expected to express views on the thesis. This may be interpreted as the role Discussion partner.

The official documents clearly underspecify student and supervisor roles and hence invite interpretation and negotiation. The university guidelines present a much narrower repertoire of student and supervisor roles compared to what emerged from the present study (cf. and ).

4. Method and material

Two different sets of material were used to shed light on the research question regarding roles in Bachelor-level thesis supervision: focus-group discussions with supervisors and open responses from a questionnaire answered by students. The focus group discussions in the two language departments took place digitally (Zoom) and were recorded and transcribed. The discussions with subject 1 (four participants; 60 minutes; in Swedish) and subject 2 (three participants; 54 minutes; in English) were held separately. The discussions (e.g. Edley and Litosseliti Citation2018) were semi-controlled, with one of the authors present for each session, introducing the topics for discussion and asking follow-up questions when needed. The groups were asked what their general thoughts were on roles and responsibilities in undergraduate thesis supervision. We were interested in not only what the participants reported regarding practice in terms of roles, but also how participants talked about student and supervisor roles (e.g. word choices).

The questionnaire was distributed electronically in 2020 to students registered on the thesis course in the two departments 2016–2019. Two versions of the questionnaire were sent via email: one in Swedish and one in English, and students could choose which version to complete. Out of 150 requests, 49 responses were received. The questionnaire had 14 questions with answers based on Likert scales, six multiple-choice questions and five questions with open responses. Only the open-response part of the questionnaire was used for the present study.

No vulnerable groups nor sensitive data are involved in the study. The participants gave their informed consent to participate. It was made clear that participation was voluntary and that participants could leave the study at any time. Approval by an independent ethics board is not required for this study, according to Swedish law (2003:460). References made to specific people or departments in the material have been anonymized. The data are managed and stored responsibly and in compliance with GDPR.

The material was approached through thematic analysis, based on semantic categories. For example, the supervisor role Support Person was created based on participants’ use of word families involving support, help and guidance (Examples 10–12 below). The role of Communicator foregrounds the semantic field of communication, as indicated in the underlined expressions in Examples 15–17: answer questions; have a trusting interplay; maintain a dialogue. As an example of a student role, the Idea generator was extracted based on participants referring to ideas and synonymous words coming from or attributed to the student (Example 22). The role of Writer is based on the semantic field of academic thesis writing, for which word choices such as final draft and polish and edit occurred (Example 25). We worked inductively instead of applying an existing classification model from previous research, even if previous work informed our thinking. We analysed the material through several iterations and extracted examples which were classified from the perspective of roles. All authors discussed the role categories and the examples, which over the course of the analysis led to certain categories being removed and some examples being reclassified.

We will not be providing quantitative data in the findings, for example by measuring how often a specific role is referred to, or how many within either group refer to specific roles, as the material is too limited. Nor will we make comparisons between the supervisor and student groups, as the data types are too dissimilar, with the supervisor material consisting of oral discussions and the student material of individual, written responses. Despite the dissimilarity of the material, it has provided valuable findings about roles in a thesis supervision context. A final remark that needs to be made is that it is a shortcoming of research based on interviews and questionnaires that it does not make it possible to access roles in practice, but it is restricted to reflecting what participants report about roles.

5. Research outcomes

This section presents the joint analysis of the focus group discussions with the supervisors and the open questions in the student questionnaire. We describe the supervisor roles in section 5.1 and the student roles in section 5.2.

5.1 Supervisor roles

illustrates those roles which are attributed to the supervisor in relation to the student. The roles are organised on a scale from transactional to interactional, as in , even if the roles are mostly different from those in . The transactional end may be mapped onto Anderson et al.’s (Citation2006) ‘shaping’ roles, and the interactional end onto their ‘supporting’ roles. Placed outside of the scale in the figure, there is also a communication function linked to roles; many examples stress the supervisor’s role of giving [clear] information or instructions, which may not necessarily function as either transactional or interactional.

We see the role Subject Expert as a prerequisite and a key function of the supervisor, even if it is not referred to in the material very often.

| 1) | As a student what is needed is […] subject knowledge from the teacher/supervisor. [Student-2-Tr] Footnote5 | ||||

It has been suggested that supervisors play a crucial role ‘in helping students take a disciplinary lens to their research’ (Ashwin, Abbas, and McLean Citation2017, 527); this they can only do if they possess the required subject expertise. The role of Subject Expert overlaps to some extent with Quality Controller, even if the latter is more of an explicit management function, where the abstract notion of quality is central.

Also at the transactional end, we find the Official, who is often (implicitly) referred to in the material. This shows how fundamental the institutional frameworks are for the supervision (cf. Lönn Svensson’s (Citation2007) role of Official). The role illustrates an administrator’s relationship to the student in different ways, for example through providing information, instructions, or criteria. In the Swedish context, all universities are a government authority.

| 2) | The responsibility we have as supervisors as a myndighet [Swedish for ‘government authority’] [Supervisor-2] | ||||

Another role that is central in the material is that of Quality Controller, where aspects of quality are referred to and the supervisor is presented as a role that warrants high quality. This is partly a reflection of the institutional circumstance that the thesis is assessed and graded.

| 3) | Feedback is important because both student and supervisor want the essay to be as good as it can be. [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

| 4) | [the supervisor should] guarantee the quality of the work, both in terms of language and content and whether the reasoning is research based. [Supervisor-1-Tr] | ||||

The role as Professional involves showing moral responsibility and even courage, which in this professional context may be about rejecting work that does not meet the minimum standards.

| 5) | [the supervisor] should not be afraid to point out that the student’s topic/theory seems too difficult to work with [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

Another dimension of the Professional has to do with reputation and honour, as when supervisors stress that they should be able to justify a passing grade on a thesis.

| 6) | We’ve also had a certain feeling that our names are on theses either as supervisors or examiners and if they [=students] don’t change things I’m going to be embarrassed [Supervisor-2] | ||||

The role as Inspector occasionally appears in the material. Going beyond the controlling function of the Official, this role is typically about settling what is correct and incorrect; it comes with a strong sense that there is a ‘key’, or that the supervisor should police the thesis work. The Inspector is similar to Dysthe’s teaching model, where the student is highly dependent on the supervisor, who has all the answers. This is at odds with the regulations’ description of the thesis as ‘independent work’. The student comment below is relatively general, while the supervisor’s comment brings up plagiarism as a specific case that is possible to check in a straightforward way.

| 7) | It’s important to point out what is right or wrong so the student does not think they are doing the right thing and discovers all too late that they were on the wrong track. [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

| 8) | in order to make sure that the student hasn’t cheated, or copied, intentionally or not. This is a really big problem. I get back to the student because we say in our instructions that plagiarism is absolutely forbidden. [Supervisor-1-Tr] | ||||

In the Educator role, the focus is on the student’s ongoing learning, rather than for example a final thesis product. Aspects that may be involved in this role are helping the student understand how, what and why, and taking the student’s individual needs as a point of departure. In example (9), the Educator role also involves withholding intervention when needed, which suggests a Freedom giver ().

| 9) | … ability to foster independent learning—It is very important for the supervisor to know when to help and when not to, allowing the students to develop their skills and realise their learning goals through the process of writing the thesis. [Student-2] | ||||

Moving down towards the interactional end of the scale, we find the role as Support Person, which is prominent in the material. Students as well as supervisors often use word families that involve support, help and guidance. This suggests a secondary role for the supervisor and emphasises that the primary responsibility is indeed with the student (cf. Stappenbelt and Basu Citation2019, 209).

| 10) | All help and all support are received with great gratitude [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

| 11) | As a student […] guidance in essay writing is needed. [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

| 12) | The teacher is there mainly to support the student, help the student find a good research question. [Supervisor-1-Tr] | ||||

The participants sometimes mention general support and sometimes refer to specific types of support, such as for the thesis writing or the research question. The specific role in (11) seems equivalent to the role of Editor in Rowley and Slack (Citation2004), ‘supporting structuring and writing of the dissertation’, while the specification about the research question in (12) suggests the Critic ‘of the design of enquiry’ in Brown and Atkins (Citation1988) and Advisor on research methodologies ‘in relation to specific design issues’ in Rowley and Slack (Citation2004). This illustrates an issue inherent in analysing roles, which has to do with what scope—what degree of generality and specificity—to choose. In categorisation, also, some researchers prefer lumping categories together and others splitting them.

Two supervisor roles which relatively speaking reflect a close interpersonal contact between the supervisor and the student are that of Coach and Counsellor. Both are implied sporadically in the material, at times with a negative framing, where students voice the opinion that other roles are more important. The role as Coach, similar to a sports coach, is visible in an example where a student stated that ‘a little bit of pep talk’ [Student-2-Tr] is desirable from the supervisor. This dimension may be especially important at Bachelor level, as Derounian’s (Citation2011) small-scale study of undergraduate student perceptions found that showing enthusiasm for the thesis project was ranked high as a desirable characteristic of a supervisor.

The role as Counsellor foregrounds the supervisor’s ability to create empathy and a sense of security. This is not always seen as desired or prioritised by students, as in (13):

| 13) | Supervisors also (often) have valuable knowledge about similar projects so suggestions for useful articles feel much more important than moral support [literally ‘hold-my-hand-support’] [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

One supervisor describes some students as being more in need of the Counsellor, at least initially, than others.

| 14) | Certain students will need a little more in the beginning, to get going and feel confident, with their project, while others are able to fly on their own from the beginning and only get a little [support] every now and then. [Supervisor-1-Tr] | ||||

Regarding the communication function, many examples stress the supervisor’s role of giving (clear) information or instructions. Behind the role of Communicator, we sometimes find a simplified communication model that encodes information transfer from A to B, for example that the supervisor makes the information X available to the student, who will then absorb it without interference, disturbance, or negotiation.

| 15) | The supervisor should […] answer questions students have [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

| 16) | It’s important to have a trusting interplay between the student and the supervisor. [Student-1-Tr] | ||||

| 17) | It’s really important to maintain a dialogue the whole time. [Supervisor-1-Tr] | ||||

The Discussion Partner figures relatively rarely in the material, which may have to do with the power distance between a Bachelor student and a supervisor being too great for them to be considered ‘partners’.

Despite the focus of the study being on the roles of the supervisor and the student in a dyadic relation, the focus group material also indicates the important role played by the collegiate, showing an awareness not only of individual but also of collective responsibility (cf. Solin and Östman Citation2015). Supervisor roles include not only those attributed to the supervisor in relation to the student, but also those attributed to the supervisor in relation to colleagues. It is possible to identify, for example, the role as Support Person, where colleagues are portrayed as helpful and happy to collaborate. The collaboration is sometimes explicitly described as informal and needs-based, for example from an apprentice-mentor perspective, as when a new supervisor joins the group.

| 18) | We kind of do it as an informal helping each other out that especially if like somebody’s new […] then […] we as more experienced colleagues have helped her out and talked to her about the kinds of things that we do [Supervisor-2] | ||||

Collegial support is framed as needed; several supervisors emphasise that a doctoral degree does not prepare a university teacher for supervision.

| 19) | I came straight from … completing my PhD to into a job … I think there’s just a general expectation that was my sense that you’ve got a PhD that qualifies you to do all of this stuff [Supervisor-2] | ||||

5.2 Student roles

illustrates the roles that are attributed to the student in the material, organised from relatively independent to dependent. This scale reflects the fundamental principles that the Bachelor thesis is meant to be the student’s own independent work, as specified in the Higher Education Act, and that the work relies on the support from a supervisor.

The role which we call Project Manager is found in descriptions of the student as independent and as the one conducting the thesis work.

| 20) | It is an independent piece of work. Yes, it’s supposed to be independent [Supervisor-1-Tr] | ||||

| 21) | I believe the rest falls on the student, if you want your degree you’ll have to do the work! [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

The role of Idea generator specifies that it is the student’s task to generate ideas for the thesis.

| 22) | they will come with the ideas, they should have thought about things before we meet, and have something to present [Supervisor-1-Tr] | ||||

Even if it is seen as necessary for the student to generate ideas, the support from the supervisor may sometimes result in choosing among these ideas.

| 23) | They have many ideas, very often, and it’s extremely difficult as [NN] said, to formulate what they want to do research on, so that’s the most difficult thing. [Supervisor-1-Tr] | ||||

| 24) | The supervisor plays an important role when it comes to the ideas stage because otherwise precious time may be wasted on a fun but impractical idea. Sometimes we need help so to say to ‘kill your darlings’. [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

The role as Writer stresses the work done with the writing and the thesis itself as a key area of responsibility:

| 25) | Likewise, feedback on the final draft is also important as it is the last chance before the defence [seminar] to polish and edit. [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

The role as Learner foregrounds learning processes and takes up aspects such as progression over time; it may be framed as more or less independent. This role mirrors that of the Educator for the supervisor, which often has to do with encouraging and motivating learning, or helping the student understand.

| 26) | Well, the student has the responsibility for their own learning. That type of learning outcome is already in place from the first term, so it’s most definitely relevant for thesis writing. [Supervisor-1-Tr] | ||||

| 27) | You should have made good use of the teaching at the lower levels to such an extent that you manage … [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

Among the relatively passive student roles, we find the role as Supported, where words associated with directing, guidance and support often occur.

| 28) | I think it’s important that the supervisor (who should act as a sort of ‘pro’ in this) actually guides the students. [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

| 29) | The [Language 2] department’s support is everything. It is simply not possible to manage the essay if nobody takes responsibility for giving the student the support needed. [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

Students and/or supervisors sometimes report the experience that the role as Supported has not been fulfilled and that the student has not received the expected support. The material includes some negatively framed comments regarding the role as Supported, involving word choices such as alone and lost.

| 30) | … one can easily be left alone and is just expected to make something up and guess [what to do] way too much far too many times. [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

| 31) | I did not get feedback from my supervisor in the last two stages and felt lost because of that. [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

It is clear from the material that it is an important part of the student role to follow a timetable. Many comments refer to deadlines, or to different phases, from the perspective of when it is reasonable for the student or supervisor to act.

| 32) | in the set-up there are certain times when they are forced to get in touch as it’s in the timetable [Supervisor-1-Tr] | ||||

References to time are found also in connection to the supervisor roles, linked to an institutional frame. Occasionally, we see an awareness of the practical boundaries of how much supervision should or may be given, shown both by students and supervisors.

| 33) | The [Language 2] Department needs plenty of time set aside to be able to have time to support students [Student-2-Tr] | ||||

| 34) | it depends on how much time you have […] it’s about hours. [Supervisor-1-Tr] | ||||

We found no references to the student as a Critic, e.g. questioning key concepts (cf. Ashwin, Abbas, and McLean Citation2017), despite the emphasis placed on critical thinking in the Swedish Higher Education Act. Also, there were no references to students as emerging Subject experts, indicating that students in our context are not expected to reach an in-depth disciplinary understanding. Language subjects tend not to have programmes, but students apply for courses on a term-by-term basis, and the thesis is written over the course of a single term. Programme contexts where students work on the thesis for a full academic year should be more successful in promoting subject expertise, even to the extent ‘that students see their dissertation as a piece of disciplinary research rather than simply a piece of research’ (Ashwin, Abbas, and McLean Citation2017, 527).

6. Discussion

Supervision is a complex process, which at times involves seemingly conflicting roles. Different or even conflicting roles have been stressed in the literature (e.g. Anderson, Day, and McLaughlin Citation2006; de Kleijn et al. Citation2012; Guzdev, Terentev, and Dzhafarova Citation2020; Svärd Citation2013), and our study supports this view of supervision. It has been a key finding also in research that is not focused on roles as such that there exists variation in perceptions and values. For example, supervisors understand student independence in different ways (Magnusson and Zackariasson Citation2019), and different understandings may cause tension (e.g. Lee Citation2008). and make visible the balancing act between interactional and transactional roles, and support and management, in the supervision context. The student roles in the material involve a range of relatively dependent and independent types. These are reflected also in the supervisor roles, which involve both supporting, where the student is framed as being in charge, and shaping/managing, where the student is framed as being relatively passive. Given these scales, it seems inevitable for practitioners to develop different interpretations of and views on the roles involved. The gatekeeper (Svärd Citation2013) is visible in the managing roles and the co-responsible in the supporting roles. The supporting role was visible among supervisor colleagues as well, showing that responsibilities may be shared not only between student and supervisor but also among a group of supervisors.

Another balancing act which appears in the material is that between seeing the thesis as part of a process versus a product (cf. Svärd Citation2013, 49). The process-product continuum is rarely talked about in the material, but an implicit orientation to one or the other is often found. It is in the process end that there may be a need for roles such as Support people and Counsellors, while the product end involves a clearer need for the Inspector or the Official. In supervision at the Bachelor level, specifically, it has been argued against seeing the thesis primarily as a product, or as ‘novel research’, and in favour of viewing the process itself as central (Stappenbelt and Basu Citation2019).

Another continuum where stakeholders may have different preferences relates to the transactional versus the interactional. At the transactional end, the focus is on the dissemination of knowledge (linked to e.g. the Subject expert and Quality controller). At the interactional end, we are reminded that, in addition to institutional roles, supervisors and students have personalities and face needs. This may be illustrated by a student comment on the desirability of the supervisor to communicate not just in a clear, but also in a pleasant, way (cf. the desired supervisor characteristic ‘friendly’ reported in Derounian Citation2011):

| 35) | the supervisor should be able to communicate professionally, clearly and pleasantly by email [Student-2] | ||||

The balancing act between the interactional and transactional is stressed also in de Kleijn et al. (Citation2012), who analysed the supervisor-student relationship based on Master student questionnaires: they labelled the dimension referring to how emotionally involved the supervisor is in the project/with the student ‘affiliation’ and the dimension referring to the supervisor giving direction to student activities ‘control’. These dimensions have been framed somewhat differently in other studies: e.g. counselling–intellectual (Todd et al. Citation2004); professional role–personal self and dependence–independence (Lee Citation2008).

Our analysis also very clearly points to balancing acts and conflicting roles in supervision. This raises the question whether the participants show an awareness of the existence of different preferences for the roles, whether for students or supervisors. We see some awareness that there may be considerable variation. The student group is sometimes described as heterogeneous in the sense that the possibility of individual students to adopt active roles may vary. It is then not about preference, but is linked to ability. We occasionally see the construction of a category of ‘weak students’ (‘some need much more’ [Supervisor-1-Tr]). Variation in supervisor practices (cf. e.g. Holmberg Citation2006) is also referred to occasionally in the material, but it is linked not to ability but to (disciplinary and/or local) culture. The material also indicates variation in how roles are executed: for example, the student role of Supported is framed not just positively, but also negatively, with several students reporting not having received the amount of support they had expected and feeling abandoned by their supervisor.

Existing work on supervision has foregrounded the supervisor-student relationship more generally (e.g. de Kleijn et al. Citation2012) or specific qualities such as student independence (e.g. Magnusson and Zackariasson Citation2019) and self-regulation (e.g. Meeus, Van Looy, and Libotton Citation2004), or the ‘characteristics’ of a good supervisor (Derounian Citation2011), or factors that affect student satisfaction with the supervisor (e.g. Seeber and Horta Citation2021), and has not approached supervision from the perspective of roles to a great extent. Compared to qualities and characteristics, however, roles may be seen as less essentialising, rather foregrounding personas that supervisors and students choose to adopt to different degrees. Furthermore, as roles are more concrete than abstract qualities, they may be intuitively easier to understand and discuss in supervision settings. Even if the notion of role has been critiqued as being static and as implying socio-structural determinism (e.g. Depperman Citation2015), we hope to have shown that roles may be approached dynamically. We have identified a broad repertoire of roles, linked to supervision practices and experiences, which participants may relate to in very different ways. What specific roles are adopted and to what degree may be influenced by varying factors: it may, for example, change over time, depend on local practices, or the roles adopted by the other in the dyadic student-supervisor relationship.

7. Conclusion

Focusing on thesis supervision at the Bachelor level, this study has aimed to map the supervisor and student roles that emerge from data collected in a Swedish university context. Given the strong focus on the doctoral level in research on supervision, the study helps to fill a gap in our knowledge about supervision at the Bachelor level. There is a lack of previous research that maps student roles in supervision, so our study makes a contribution here as well. In addition to the data on student roles and supervisor roles in relation to students, the participants also commented on supervisor roles in relation to fellow supervisors. This adds another relational dimension to thesis supervision practices, and we hope that future work will investigate collegial roles.

The analysis points to a considerable complexity and an extensive repertoire when it comes to roles attributed to students and supervisors. In references to supervisors, we identified the Coach and the Counsellor in roles that are primarily at the interactional end. The Support Person and the Educator are also about offering support, but they also serve institutional and transactional purposes. At the transactional end, we found the Subject Expert, Official, the Quality Controller, the Professional and the Inspector. The roles as Communicator and Discussion Partner were linked to a communication function that is sometimes stressed in the supervision context. In references to students, we found roles that ranged from relatively independent to dependent: the Project Manager, the Idea Generator, the Writer, the Learner and the Supported. We also found time constraints to be seen as important for the roles; many comments referred to students following a timetable and supervisors having limited time.

We expect studies based on more extensive data to capture more roles. Additional roles have been brought up in previous research, but (a) they have been limited to supervisor roles only, (b) they have not always been based on empirical data, (c) they have applied primarily to the doctoral level. What our study adds to previous research is an empirically-based inventory of roles—not only for supervisors, but also for students. The focus on the Bachelor level is justified by the large number of students and teachers whose first supervision experience is at this level, which means that differing and potentially conflicting perspectives are especially likely.

If we consider the roles for supervisors identified in previous work (e.g. ), some of these are visible in , even if the labels may vary. Existing models vary also in terms of splitting or lumping: the number of roles included. Some roles recur more than others. Two basic role complexes are the researcher (Lönn Svensson Citation2007) and research advisor (Guzdev, Terentev, and Dzhafarova Citation2020), on the one hand, and coach (Bégin and Gérard Citation2013) and leader (Lönn Svensson Citation2007), on the other. The former is equivalent to subject expert and the latter to project manager. Notably, we did not find a project manager role for the supervisor, but only for the student, in our data. This likely has do with the local regulations stressing that the Bachelor thesis needs to represent the student’s independent work.

The role as coach has been seen as transactional (Bégin and Gérard Citation2013), as we saw in Section 2. Coach is included as a role in our classification as well, but we define it as primarily interactional rather than transactional. This illustrates a difficulty in this type of analysis: word choices for roles may lead to ambiguity and may vary in the literature. Role labels may be difficult to define, as they are essentially metaphors. As metaphors, they foreground specific aspects of a role while backgrounding others. The same role label, such as coach, may come with different associations and connotations for different people.

How should supervisors and students manage the complexity of roles indicated in the material? A certain degree of variation in how students and supervisors view their roles and responsibilities should be expected in this context, given that it revolves around practices which are not specified through regulations (cf. e.g. Holmberg Citation2006, 214). The individuals who participate in and shape the practices do not all have the same backgrounds or preferences for styles (e.g. Holmberg Citation2006). As often stressed in previous research (e.g. Roberts and Seaman Citation2018; Stappenbelt and Basu Citation2019; de Kleijn et al. Citation2012), we see a need to discuss roles and expectations to a greater extent, thereby creating a greater awareness of the attitudes and expectations that we carry with us into the supervision context. Examples of tools that may be used to discuss roles include ‘Thesis responsibility survey items’, where participants assess statements such as ‘It is the supervisor’s/the student’s responsibility to choose a viable topic’ (e.g. Stappenbelt and Basu Citation2019), and ‘student-supervisor contracts’ (e.g. Derounian Citation2011).

We expect the roles that have emerged from our study, especially in combination with quotes from participants, to be a useful starting point for discussions—even if our study is based on small-scale material, culled from a specific context. It is a question for future research to what extent the findings are contextually conditioned and apply to mostly undergraduate rather than graduate supervision, or to specific disciplines. Our study is based on what supervisors and students report regarding roles, and thus needs to be complemented by studies on what roles are in fact enacted. We have found the use of focus group data a useful method for gathering data that helps to capture how practitioners view the roles of those involved in the practice (cf. Magnusson and Zackariasson Citation2019). It would be interesting to see future analyses of focus group discussions also with students. Supervisor and student narratives about supervision could be approached through positioning analysis, as it could help us capture underlying attitudes and understand why individual students and supervisors orient to some roles and reject others. Also, future work could study longitudinally how individual supervisors and students develop and change their repertoire of roles over time, so that we may learn more about what factors affect roles. We hope that future research will continue building an empirically well-founded model, which could be used as a basis for comparisons of different styles or supervision cultures—not only from the perspective of the supervisor (and the supervisor colleague), but also the student.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful feedback, which has helped up improve the quality of the article. Any remaining shortcomings remain our own responsibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Annelie Ädel

Annelie Ädel is professor of English Linguistics at Dalarna University, Sweden. Her linguistic research is largely applied and focused on how communication works in the academic sector, in teaching as well as in research. She has studies communication forms such as student theses, student spoken presentations, teachers’ written feedback, academic lectures and the research article. She has many years of experience supervising student theses.

Julie Skogs

Julie Skogs is senior lecturer in English Linguistics at Dalarna University, Sweden. Her research is mostly applied and focuses on how communication works in e-learning contexts. She is a certified ‘Excellent teacher’ with teaching experience above all in grammar, academic writing, methodology and thesis supervision.

Charlotte Lindgren

Charlotte Lindgren is senior lecturer in Education, focusing on French, at the Department of Pedagogy, Didactics and Education Studies at Uppsala University, Sweden. She is a certified ‘Excellent teacher’ since 2015. Her teaching is currently focused on subject didactics and further education/lifelong learning in French. She has also conducted research on children’s literature from a range of different perspectives.

Monika Stridfeldt

Monika Stridfeldt is senior lecturer in French at Dalarna University, Sweden. Her research focuses among other things on learners’ pronunciation and perception of spoken French, as well as on oral interaction in net-based language studies in higher education.

Notes

1 Cf. the Oxford English Dictionary’s fourth sense of ‘role’: “The characteristic or socially expected behaviour pattern of any person with a certain identity or status in a particular social setting or environment”.

2 Swedish ‘forskare’, ‘ledare’ and ‘tjänsteman’.

4 References to local sources are not supplied to avoid revealing the name of the university.

5 In the examples, ‘Supervisor’ means it is a supervisor speaking, while ‘Student’ means it is a student writing. ‘1’ is for Subject 1, ‘2’ for Subject 2. ‘Tr’ indicates a translation from Swedish. Key words for the semantic analysis have been underlined.

References

- Anderson, C., K. Day, and P. McLaughlin. 2006. “Mastering the Dissertation: Lecturers’ Representations of the Purposes and Processes of Master’s Level Dissertation Supervision.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (2): 149–168. doi:10.1080/03075070600572017.

- Ashwin, P., A. Abbas, and M. McLean. 2017. “How Does Completing a Dissertation Transform Undergraduate Students’ Understandings of Disciplinary Knowledge?” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (4): 517–530. doi:10.1080/02602938.2016.1154501.

- Belcher, D. 1994. “The Apprenticeship Approach to Advanced Academic Literacy: Graduate Students and Their Mentors.” English for Specific Purposes 13 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1016/0889-4906(94)90022-1.

- Bégin , C., and L. Gérard . 2013. “The Role of Supervision in Light of the Experience of Doctoral Students.” Policy Futures in Education 11 (3): 267–276. doi:10.2304/pfie.2013.11.3.267.

- Brown, G., and M. Atkins. 1988. Effective Teaching in Higher Education. London: Routledge.

- de Kleijn, R. A. M., M. T. Mainhard, P. Meijer, A. Pilot, and M. Brekelmans. 2012. “Master Thesis Supervision: Relations Between Perceptions of the Supervisor-Student Relationship, Final Grade, Perceived Supervisor Contribution to Learning and Student Satisfaction.” Studies in Higher Education 37: 925–939. doi:10.1080/03075079.2011.556717.

- Depperman, A. 2015. “Positioning.” In The Handbook of Narrative Analysis, edited by A. De Fina, and A. Georgakopoulou, 369–387. London: John Wiley.

- Derounian, J. 2011. “Shall We Dance? The Importance of Staff–Student Relationships to Undergraduate Dissertation Preparation.” Active Learning in Higher Education 12: 91–100. doi:10.1177/1469787411402437.

- Deuchar , R. 2008. “Facilitator, Director or Critical Friend? Contradiction and Congruence in Doctoral Supervision Styles.” Teaching in Higher Education 13 (4): 489–500. doi:10.1080/13562510802193905.

- Dysthe , O. 2002. “Professors as Mediators of Academic Text Cultures.” Written Communication 19 (4): 493–544. doi:10.1177/074108802238010.

- Edley, N., and L. Litosseliti. 2018. “Critical Perspectives on Using Interviews and Focus Groups.” In Research Methods in Linguistics, edited by L. Litosseliti, 195–225. London: Bloomsbury.

- Guzdev, I., E. Terentev, and Z. Dzhafarova. 2020. “Superhero or Hands-Off Supervisor? An Empirical Categorization of PhD Supervision Styles and Student Satisfaction in Russian Universities.” Higher Education 79: 773–789. doi:10.1007/s10734-019-00437-w.

- Handal, G., and P. Lauvås. 2008. Forskarhandledaren [The Doctoral Supervisor]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Holmberg, L. 2006. “Coach, Consultant or Mother: Supervisors’ Views on Quality in the Supervision of Bachelor Theses.” Quality in Higher Education 12 (2): 207–216. doi:10.1080/13538320600916833.

- Krase, E. 2007. ““Maybe the Communication Between Us Was Not Enough”: Inside a Dysfunctional Advisor/L2 Advisee Relationship.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 6: 55–70. doi:10.1016/j.jeap.2006.12.001.

- Lee, A. 2008. “How Are Doctoral Students Supervised? Concepts of Doctoral Research Supervision.” Studies in Higher Education 33 (3): 267–281. doi:10.1080/03075070802049202.

- Lönn Svensson, A. 2007. Det beror på: Erfarna forskarhandledares syn på god handledning [It Depends: Experienced Doctoral Supervisors’ Views on High-Quality Supervision]. Doctoral Dissertation. Göteborg University, Sweden.

- Magnusson, J., and M. Zackariasson. 2019. “Student Independence in Undergraduate Projects: Different Understandings in Different Academic Contexts.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 43 (10): 1404–1419. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2018.1490949.

- Meeus, W., L. Van Looy, and A. Libotton. 2004. “The Bachelor’s Thesis in Teacher Education.” European Journal of Teacher Education 27: 299–321. doi:10.1080/0261976042000290813.

- Mellado, C. 2019. “Journalists’ Professional Roles and Role Performance.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, edited by J. F. Nussbaum, 1–22. Oxford University Press.

- Pinto, S., and M. H. Araújo e Sá. 2020. “Researching Across Languages and Cultures: A Study with Doctoral Students and Supervisors at a Portuguese University.” European Journal of Higher Education 10 (3): 276–293. doi:10.1080/21568235.2020.1777449.

- Roberts, L. D., and K. Seaman. 2018. “Good Undergraduate Dissertation Supervision: Perspectives of Supervisors and Dissertation Coordinators.” International Journal for Academic Development 23 (1): 28–40. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2017.1412971.

- Rowley, J., and F. Slack. 2004. “What Is the Future for Undergraduate Dissertations?” Education + Training 46 (4): 176–181. doi:10.1108/00400910410543964.

- Seeber, M., and H. Horta. 2021. “No Road Is Long with Good Company. What Factors Affect Ph.D. Student’s Satisfaction with Their Supervisor?” Higher Education Evaluation and Development 15 (1): 2–18. doi:10.1108/HEED-10-2020-0044.

- Solin, A., and J.-O. Östman. 2015. “Introduction: Discourse and Responsibility.” Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice 9 (3): 287–294. doi:10.1558/japl.v9i3.20841.

- Stappenbelt, B., and A. Basu. 2019. “Student-Supervisor-University Expectation Alignment in the Undergraduate Engineering Thesis.” Journal of Technology and Science Education 9 (2): 199–216. doi:10.3926/jotse.482.

- Svärd, O. 2013. Examensarbetet i högre utbildning: En litteraturöversikt [The Degree Thesis in Higher Education: A Literature Overview]. Sweden: Uppsala University.

- Todd, M., P. Bannister, and S. Clegg. 2004. “Independent Inquiry and the Undergraduate Dissertation: Perceptions and Experiences of Final-Year Social Science Students.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 29: 335–355. doi:10.1080/0260293042000188285

![Figure 3. Supervisor roles from Brown & Atkins [B&A] and Rowley & Slack [R&S] compared.](/cms/asset/a5a43221-641f-4e72-94d4-a0e61e60b0c1/rehe_a_2162560_f0003_ob.jpg)