ABSTRACT

Numbers of autistic students and staff studying or working in post-secondary educational settings have grown since the international adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). This has been accompanied by an increase in research exploring their experiences in these settings. This scoping review sought to develop an overview of research trends in this area and identify important considerations for future research. Systematic database searches identified 93 peer-reviewed articles. Data were extracted to summarise research trends from January 2007 to June 2021. Results showed a substantial increase in studies since 2017. Studies were largely confined to the USA and focused on the experiences of autistic students. Only five studies addressed the experiences of autistic staff. The student-focused literature was primarily based in university settings and explored a range of topics, including academic experiences and experiences of support services. There was a limited focus on the social and physical environments in post-secondary settings for autistic students and staff, and there was limited research on the experiences of autistic staff specifically. The current review points to the need for greater collaboration with and involvement of the autism community in research that has implications for their lives.

Introduction

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition characterised by differences in social communication and interaction, and by singular and passionate interests or behaviours (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013). Autism affects approximately one in 100 people worldwide (Zeidan et al. Citation2022) and those affected may require individualised supports to take a full part in education (Hummerstone and Parsons Citation2021) and in the effective transition to work (CRPD, General Comment 4, Citation2016). The right to inclusive education is enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD Citation2006) as well as in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4, and recognised as an important way to realise other rights, including access to employment and to ‘lift themselves out of poverty’ (CRPD 2016, 4). In keeping with a rights-based approach, the identity-first term ‘autistic’ is used throughout this study based on reported preferences from autistic adults within the UK (Kenny et al. Citation2016) and in line with United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD Citation2006).

An aptitude for focused interests and academic pursuits means that many autistic people may not only be drawn to study in post-secondary education where these strengths are especially valued but also to work in these types of educational environments (Hamilton, Stevens, and Girdler Citation2016). Post-secondary education can be defined as the continuation of education beyond formal secondary education (Câmpeanu et al. Citation2017; Packer and Thomas Citation2021) and can include post-secondary non-tertiary and tertiary education (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO] Citation2012). Post-secondary non-tertiary education builds on secondary education by delivering learning opportunities that prepare participants for the labour market or tertiary education. Tertiary education, which includes higher education settings, provides specialised learning experiences in academic, vocational and professional education (UNESCO Citation2012). Interviews with autistic students in secondary school and their parents have shown that students have clear goals to attend post-secondary education but that they and their parents also have concerns around the readiness of institutions to meet their needs (Camarena and Sarigiani Citation2009). These concerns are reflected in the reported experiences of autistic students who have described challenges with academic requirements and mental health at university, including a possible mismatch of supports for and needs of autistic students (Anderson, Carter, and Stephenson Citation2020). Indeed, despite a significant increase in the proportion of autistic students enrolling in post-secondary education institutions (Bakker et al. Citation2019; Volkmar, Jackson, and Hart Citation2017), with one study estimating that between 0.7% and 1.9% of college students may be autistic (White, Ollendick, and Bray Citation2011), completion rates are typically lower for autistic students compared to their neurotypical peers in America and the UK (Chown et al. Citation2018; Newman et al. Citation2011). Bakker et al. (Citation2023) also found that progression issues related to credit accumulation in the second and third year were more likely for some autistic undergraduate students attending a major Dutch university when compared to their peers with no recorded conditions. For this group of autistic students, these issues negatively impacted degree completion within 3 years. These trends are concerning given that autistic adults are more likely to experience unemployment than neurotypical peers and peers in other disability categories (Shattuck et al. Citation2012) and that gaining a post-secondary education qualification is associated with better quality of life for autistic adults through enhanced employment and career opportunities (Baldwin, Costley, and Warren Citation2014). Research on the experiences of both autistic students and staff in further and higher education institutions is therefore especially important to identify potential barriers to successful work and study in these environments.

Research which sought the views of, and priorities for, autism research from the perspective of autistic persons has highlighted a clear consensus that research should focus on areas that impact people’s day-to-day lives, including key issues related to education and employment (Pellicano, Dinsmore, and Charman Citation2014b). Further, research surveying the views of both autism researchers and autistic persons highlighted discrepant views on the level of involvement in research by autistic persons, with researchers reporting much higher levels of involvement than autistic stakeholders in the research process (Pellicano, Dinsmore, and Charman Citation2014a). This could pose a major problem for translating research for practice and policy impact if researchers are focusing on areas that are less important to autistic individuals.

A period of 15 years has passed since the international adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) in 2006 (UN General Assembly Citation2006) which confirmed the right to quality education at all levels for autistic persons. However, despite the international drive for diversity in education, inclusion has proven ‘to be a complex construct, covering a wide range of phenomena’ (Dovigo Citation2017, p. vii). Within the post-secondary education context, there can be contrasting interpretations of inclusion that hamper progress, with regards to policy and practice (Strnadová, Hájková, and Květoňová Citation2015).

Therefore, an overview of the literature on the topics which researchers have focused on and the methods which have been used to capture the experiences of autistic persons in post-secondary education since the adoption of the Convention is therefore timely and necessary. In particular, a scoping review of the existing literature is needed which will show the extent to which research is representative of the experiences of autistic individuals internationally, as well as the extent to which autistic persons are consulted within this research. The current review sets out to achieve these objectives by summarising the research trends between January 2007 and June 2021 according to the following: (1) participant characteristics; (2) types of experiences explored; (3) temporal trends in publications; (4) geographical trends in publications; (5) research design and methodology, and (6) inclusion of the autistic community in the research process. In its objectives to identify recent international research trends in this area, this scoping review differs from other reviews which systematically evaluated findings on autistic students’ experiences in post-secondary education (e.g. A. H. Anderson et al. Citation2019; Flegenheimer and Scherf Citation2022; Gelbar, Smith, and Reichow Citation2014).

Method

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses and Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) statement protocol guided the methodology and reporting of this scoping review. The PRISMA-ScR was developed to enhance the consistency and quality of scoping reviews and includes a 22-item checklist of critical (n = 20) and optional (n = 2) items necessary for completion of a scoping review (Tricco et al. Citation2018). A review protocol was developed a priori but was not formally registered.

Search procedure

Comprehensive literature searches were carried out across three electronic databases, namely ERIC International, Education Research Complete (ERC) and Scopus, in June 2021. Guided by the search protocol outlined by A. H. Anderson, Stephenson, and Carter (Citation2017) and following consultation with a university-based subject librarian, the literature was searched using the following terms: (autism spectrum disorder OR autis* OR asperge* OR pervasive development disorder OR high functioning autism OR PDD OR HFASD OR ASD) AND (college OR university OR higher education OR tertiary OR post-secondary OR postsecondary OR post secondary OR further education OR TAFE OR Technical and Further Education) AND (experience* or perception* or attitude* or view* or feeling* or perspective*).

Included articles were restricted to those published between January 2007 and June 2021. This covers the period following the international adoption of the UNCRPD (UN General Assembly Citation2006). In addition, only peer-reviewed, original studies published in the English language were considered for inclusion. The remaining inclusion criteria were as follows:

One or more participants in the study were autistic staff or autistic students in a post-secondary education setting, now or in the past. These participants could be diagnosed with autism or self-identify as autistic. The decision to include participants who self-identify as autistic was made because research has shown that a substantial cohort of autistic adults are formally undiagnosed due to a range of diagnostic biases, including gender and socioeconomic status, and therefore find themselves in a position where they need to self-diagnose (McDonald Citation2020).

The study examined the experience of autistic staff or autistic students in a post-secondary education setting. This experience was described by the autistic participants themselves. Studies that explored the perspectives of autistic participants, as well as other stakeholders (e.g. family, professionals), were included.

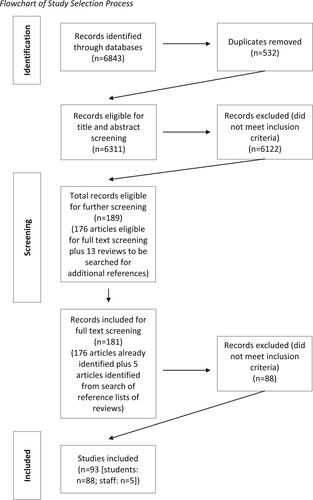

No restrictions were placed on research design or methodology.

Comprehensive searches of the three databases identified 6843 records (6311 after duplicates were removed). The titles and abstract of these 6311 articles were screened by two members of the research team, including the first author, leaving a total of 189 studies for further exploration. Of these studies, 176 were identified for full text screening. The remaining 13 studies were a combination of narrative, systematic and scoping reviews, which were loosely consistent with the inclusion criteria. The reference sections of these review articles were hand-searched for other relevant articles. Five additional studies were discovered from these review-based searches, leaving 181 articles for full text screening (i.e. 176 original articles plus 5 additional articles). Following full text screening, again carried out by two members of the research team, 93 articles met criteria for inclusion in this scoping review (Table 2 in Supplementary Material). This screening process is depicted in . Eighty-eight studies focused on the experiences of autistic students in post-secondary education settings, while five focused on autistic staff working in these settings.

Data extraction

Data were extracted onto a single coding sheet. Data extracted included: year of publication, country/countries where study was carried out, participant characteristics (number, age, gender, staff/student), educational status for studies that explored student experience (undergraduate, postgraduate, graduate, did not complete, other), employment role for studies that explored staff experience, type of institution, involvement of other stakeholders, research design (qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods), methods used to explore the experience (interviews, focus groups, case studies, observations, surveys), the types of experiences explored, and the role of autistic individuals in the design and implementation of the research (named members of the researcher team, contributors to elements of research design, involvement in data analysis, no mention of autistic involvement). Data are available under ‘Supplementary Material’.

Synthesis of results

In order to summarise research trends from January 2007 to June 2021, the extracted data were synthesised as follows: (1) Participant characteristics, (2) number of articles published each year since 2007, (3) number of studies carried out in each of the countries identified during data extraction, (4) content analysis of the experiences explored, (5) quantitative breakdown of research designs and methods used, and (6) the role (if any) of autistic individuals in the design and implementation of the study.

Reliability

A second rater independently carried out the title and abstract screening and the screening of full texts to establish interrater reliability. Reliability was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100. Reliability checks were carried out for all 6313 articles included in the title and abstract screening. Interrater agreement was 98% with disagreements resolved by consensus. Similarly, reliability checks were carried out for all 181 articles included in the full text screening. Agreement was 94.5% with disagreements resolved by consensus.

The second rater was also trained to extract and code data by providing six exemplars, completed by the first author. The second rater then independently extracted data from 34 studies that focused on autistic students (38.6%) and one study that focused on autistic staff (20%). Interrater reliability was 93.5% for the studies focused on autistic staff (disagreements were resolved by consensus) and 100% for the study that focused on autistic staff.

Community involvement statement

While members of the autistic community were not directly involved in this scoping review process, this review was part of a larger project focusing on a participatory autism research approach to exploring workplace experience and educational practice at third level in Ireland. Therefore, the authors were influenced by the early steering group discussions, which involved members of the autistic community, when choosing the focus of this review. In addition, these discussions influenced our decision to examine the extent to which the autistic community was included in prior research.

Results

Participant characteristics

Students

Eighty-eight of the 93 articles explored the experiences of autistic students (past and present) across a variety of award types (certificates, diplomas, undergraduates, postgraduates) and a range of post-secondary educational institutes, including university-specific (n = 44; 50%) and college-specific settings (n = 15; 17%) (). Eighty-four of these studies (95%) reported specific data on the number of autistic participants and there were 2054 participants, in total. The average sample size was 24 (SD = 39.9; range: 1–238) and the most common sample size was 1 participant. In the studies that classified gender, 843 (56.1%) participants identified as male, 587 (39.1%) as female, 46 (3.1%) as ‘other’, 15 (0.99%) as non-binary, and 7 (0.46%) as transgender. A total of 5 (0.33%) participants chose not to disclose their gender identity.

Table 1. Breakdown of studies according to setting, type of lived experiences explored, research design and the extent to which the autistic community were involved in the research process for studies focused on autistic students and studies focused on staff in post-secondary educational settings.

Staff

All five included articles explored the experiences of autistic staff working in a university setting (). The number of autistic participants across these five studies totalled 26 (M = 5.4; SD = 4.7; range: 1–12) and in the four studies that classified gender, 8 participants identified as male and 6 as female. Martin (Citation2021) did not provide gender breakdown in order to protect participant anonymity. Three of the studies focused on lecturers (Jorgensen et al. Citation2011; Smagorinsky Citation2011; Wright and Kaupins Citation2018), one study focused on lecturers and academic researchers (Martin Citation2021) and one study included academic librarians (A. M. Anderson Citation2021).

Types of experiences explored

Students

shows that a sizeable number of studies (n = 24; 27%) focused on the broad experiences of autistic students in post-secondary educational settings (including a combination of academic experiences, social experiences, and experiences of mental health and other support services). Eighteen studies (20%) explored the experiences of students transitioning into or out of post-secondary education; fourteen of these studies focused exclusively on the transitioning in experience, three focused on the transitioning out process and one study explored both aspects. The next most frequently explored aspects were experiences of support services (n = 16; 18%), barriers or enablers to success in post-secondary education (n = 10; 11%) and experiences of the teaching and learning environment (n = 8; 9%). The remaining studies examined the impact of planned interventions designed to support autistic students (e.g. peer mentoring groups, specialised programmes) (n = 7; 8%), students’ social experiences (n = 4; 5%) and experiences of the physical environment (n = 1; 1%).

Staff

shows that two of the five studies (40%) broadly explored the workplace experiences of 5 autistic academic librarians (A. M. Anderson Citation2021) and one autistic lecturer in a university setting (Smagorinsky Citation2011), while two other articles (40%) focused specifically on the university teaching and learning environment from the perspective of autistic lecturing staff (Jorgensen et al. Citation2011; Wright and Kaupins Citation2018). The one remaining study (20%) explored barriers and enablers to success in a university setting, in the context of autistic lecturing and research staff (Martin Citation2021).

Research design and methodology

Students

Among the sample of included studies in this category were 56 qualitative (64%), 22 mixed methods (25%) and 10 quantitative research (11%) designs (). The majority of qualitative studies (n = 50; 89%) employed interviews as part of their methodology. Many of these interviews were conducted in a face-to-face format but some studies offered a flexible approach to participation, with text, email, phone, Skype and face-to-face options made available to participants (e.g. Bailey et al. Citation2020; Cage and Howes Citation2020; MacLeod et al. Citation2017). The remaining qualitative studies (n = 6; 11%) employed techniques such as observations, focus groups, narrative case study accounts and critical autobiographies, as part of their data collection process.

The mixed method studies (n = 22; 25%) typically employed a combination of survey and interview techniques (n = 7; 32%) or a survey with open and closed-ended questions (n = 7; 32%). There were four studies (18%) that used a combination of surveys and focus groups, while the remaining four studies (18%) used a variety of techniques, including document review, behavioural observation, essays, interviews and surveys. The primary research tool employed in the quantitative studies (n = 10; 11%) was surveys. Eight of these studies (80%) used surveys, with six of these employing online platforms. Of the two studies not relying on surveys, one took the form of a single-subject experimental design that looked to evaluate the impact of a social planning intervention on the experiences of autistic students (Ashbaugh, Koegel, and Koegel Citation2017). The remaining study requested participants to rank a series of statements relating to barriers to and facilitators of student success in university settings (Thompson et al. Citation2019).

Staff

All of the studies that explored the autistic staff experience used a qualitative research design (). Three of these five studies (60%) took the form of case studies (Jorgensen et al. Citation2011; Wright and Kaupins Citation2018), one study (20%) used open-ended survey questions (Martin Citation2021) and one study (20%) interviewed participants (A. M. Anderson Citation2021). A. M. Anderson (Citation2021) offered a particularly flexible approach to participation in their 1:1 interviews: (1) phone, (2) Zoom with audio and visual, (3) Zoom with just text chat, and (4) asynchronous written responses to questions uploaded to Dropbox.

Inclusion of the autistic community in the research process

Students

Analysis of the included articles, which focused on student experiences, found that in 9% of studies (n = 8), at least one autistic researcher was a named author. In a further 19% of studies (n = 17), members of the autistic community were involved in the development of the research tools employed (e.g. survey questions, interview schedules). However, for the majority of studies (72%, n = 63), there was no mention of the autistic community being involved in the research process ().

Staff

shows that of the five studies that explored the autistic staff experience, at least one member of the autistic community was a named author for three of the studies (60% [Jorgensen et al. Citation2011; Smagorinsky Citation2011; Wright and Kaupins Citation2018]) and the autistic community was involved in the development of the research tools for one of the studies (20% [Martin Citation2021]).

Temporal trends in publications

Students

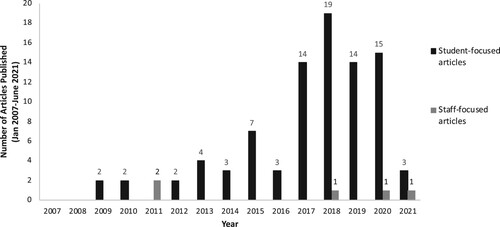

illustrates the temporal trends in publication from January 2007 to June 2021 for studies focused on the experiences of autistic students. In total, 88 studies explored the experiences of autistic students in post-secondary education during this period, with 74% (n = 65) of studies published since 2017. The first published papers to be included in this review appeared two years after the international adoption of the UNCRPD (UN General Assembly Citation2006) and both articles explored the student experience.

Figure 2. Publication trends from January 2007 to June 2021 for studies focused on the experiences of autistic students and staff in post-secondary educational settings.

Note: The substantial reduction in publications recorded for 2021 should be interpreted with caution because the article search only addressed the period up to June 2021.

Staff

During the period from January 2007 to June 2021, a total of five studies were published, which focused on the experiences of autistic staff in post-secondary educational settings (). Three of these studies (60%) were published from 2018 onwards (A. M. Anderson Citation2021; Martin Citation2021; Wright and Kaupins Citation2018), while the other two studies (40%) were both published in 2011, four years following the international adoption of the UNCRPD (Jorgensen et al. Citation2011; Smagorinsky Citation2011; UN General Assembly Citation2006).

Geographical trends in publications

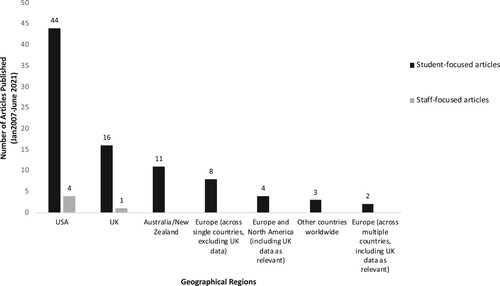

Students

shows that a total of 80 of the 88 studies (91%) that focused on student experiences in post-secondary education, were carried out in a single country, with the majority of these (n = 44; 55%) conducted in the USA. Sixteen studies (20%) were carried out exclusively in the UK and nine in Australia (11%). Eight studies (10%) were focused in European countries, other than the UK. These included Sweden (n = 3 [Fleischer Citation2012; Hugo and Hedegaard Citation2017; Simmeborn Fleischer, Adolfsson, and Granlund Citation2013]), Belgium (n = 3 [Van Hees, Moyson, and Roeyers Citation2015, Citation2018]), Ireland (n = 1 [Bell et al. Citation2017]) and the Netherlands (n = 1 [Pesonen et al. Citation2023]).

Figure 3. Breakdown of studies according to the geographical location where the research was conducted from January 2007 to June 2021 for studies focused on the experiences of autistic students and staff in post-secondary educational settings.

A small number of studies (n = 8; 9%) conducted research across multiple countries. Four of these eight studies (50%) focused on European and North American countries (Cage, De Andres, and Mahoney Citation2020; Fabri et al. Citation2022; Jackson et al. Citation2018; Vincent Citation2019). All four of the studies included participants from the UK, with two also including participants from other European countries (Finland, Spain, France). Two studies (25%) were carried out across Australia and New Zealand (A. H. Anderson, Carter, and Stephenson Citation2020; A. H. Anderson, Stephenson, and Carter Citation2020), while another two (25%) were carried out across multiple European countries (e.g. Spain, France, Finland, Netherlands [Casement, Carpio de los Pinos, and Forrester-Jones Citation2017; Pesonen et al. Citation2021]). Participants from the UK were involved in both of these studies. presents the geographical trends for student-focused studies.

Staff

illustrates that four of the five studies (80%) that explored the experiences of autistic staff were based in the USA (A. M. Anderson Citation2021; Jorgensen et al. Citation2011; Smagorinsky Citation2011; Wright and Kaupins Citation2018) and one was based in the UK (20% [Martin Citation2021]).

Discussion

A total of 93 articles, which were published between January 2007 and June 2021, were analysed as part of this scoping review. The purpose of the review was to provide a functional understanding of the literature that focuses on the experiences of autistic people who are studying and working in post-secondary educational settings. In particular, it sought to examine the extent to which the international literature explores this aspect of the autistic experience, as well as the extent to which autistic individuals are consulted with during the research process. To achieve this, the review examined where research has been conducted, as well the number of articles published each year since 2007. In addition, data were extracted on the types of experiences that the studies explored and the strategies used to gather information about these experiences. Importantly the analysis also looked at whether or not autistic people were involved in designing and carrying out the studies.

Research trends: studies focusing on student experiences

In total, 93 studies were included in the current review and the majority (n = 88, 95%) explored the experiences of 2054 autistic students (past and present) across a variety of award types (certificates, diplomas, undergraduates, postgraduates) and a range of post-secondary educational institutes. The university context was the most common research setting across the included studies and the range of experiences explored was somewhat varied. The majority of studies (n = 42; 47%) focused on the broad experiences of autistic students, which included some combination of academic experiences, social experiences, and experiences of mental health and other support services, as well as experiences transitioning in and out of post-secondary education. A sizeable portion of studies (n = 16; 18%) also looked exclusively at the experiences of student support services. Interestingly, only four studies specifically explored the autistic social experience and only one focused on the physical environment. Considering that autism is a developmental condition characterised by differences in social communication (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013) and sensory processing (The National Autistic Society Citation2023), these are significant gaps within the existing literature.

Analyses also showed that across the included studies, research methodologies were varied, with many studies taking the communication preferences of autistic participants into account and offering a number of platforms to facilitate participation. For example, Cage and Howes (Citation2020) offered interviewees a choice between phone-, face-to-face-, Skype-, instant messaging- or email-based interviews. This is consistent with recommended best practice, which establishes flexibility and supports diverse communication preferences (Vincent Citation2019).

It should be noted that one member of the research team, in the Cage and Howes (Citation2020) study, was autistic and drew on their own experiences to inform research design. This may account for the diverse procedural approaches employed with the study. Therefore, it is concerning that over two-thirds of the included studies did not mention whether or not the autistic community were involved in the helping design the research, analyse the data or any other aspect of the research process. According to Pellicano et al. (Citation2014a, 2014b), who conducted a large-scale investigation of the views of autistic people in the UK, with regards to autism related research, the autistic community needs to be substantially more involved in setting research priorities, foci, design and aspects of research, more broadly. Therefore, although the methodology and foci of the included research studies were varied, and there were some instances of participatory or co-produced research, overall it is impossible to ascertain if the included studies, as a whole, reflect the priorities of the autistic community and address the areas of most concern and impact for autistic people.

Finally, the current review wanted to ascertain the extent to which the autistic student experience is represented across the international literature. Analyses revealed that there has been a substantial increase in research publications focusing on the student experience since 2017. Over half of the 88 studies that explored the experiences of autistic students were conducted in the USA, with the UK coming in a distant second. Furthermore, the international literature outside these jurisdictions was relatively sparse, with a comparatively small number of studies emanating from European countries, other than the UK. Inclusion criteria did limit the identification of relevant articles to those published in the English language, which may have resulted in pertinent research from a number of countries being excluded. However, this does not account for the lower publication rates of studies conducted in primarily English-speaking countries, such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Ireland.

Research trends: studies focusing on staff experiences

As previously noted, findings showed that in recent years there has been a substantial increase in research focusing on autistic students’ experiences in post-secondary education and university settings, in particular. However, this trend was not observed for studies exploring the experiences of autistic staff in these settings. During the period from January 2007 to June 2021, only five studies focused on autistic staff and two of these were published in 2011. This may be indicative of a reluctance among faculty to disclose a diagnosis, such as autism, due to concerns about negative outcomes and stigma (Thompson-Hodgetts et al. Citation2020), which in turn hinders research in this area (Wright and Kaupins Citation2018) and may have informed the decision by Martin (Citation2021) not to provide gender breakdown in order to protect participant anonymity. Another factor to consider is that people born after 1980 are increasingly receiving an autism diagnosis later in life, due to problems with the diagnostic process in the past, as well as a growing awareness of autism within society (Stagg and Belcher Citation2019). Therefore, these individuals are only starting to identify as autistic after the age of 50, thereby contributing to a smaller participant pool in previous research.

Although the geographical spread across these five studies was restricted to the USA (n = 4) and the UK (n = 1) and the research foci were restricted by the low number of studies, there was evidence of inclusive autism research in the studies’ designs. For instance, the research team included at least one co-researcher from the autistic community for three of the studies (Jorgensen et al. Citation2011; Smagorinsky Citation2011; Wright and Kaupins Citation2018) and Martin (Citation2021) sought input and feedback from the autistic community when developing their qualitative survey. Finally, while co-production was not a feature of the A. M. Anderson (Citation2021) study, they did offer multiple option for participation in 1:1 interviews, in order to facilitate diverse communication preferences. It is particularly noteworthy that three of the five studies included an autistic researcher as part of the research team. This is contrary to the pattern observed within the student literature base; the majority of research was conducted exclusively by non-autistic research teams. This may indicate that the autistic staff experience is receiving less attention within the literature because it is invisible to or less of a priority for non-autistic researchers.

Limitations

One of the main shortcomings in this review relates to publication bias. Firstly, the inclusion criteria only allowed for peer-reviewed articles, resulting in the exclusion of dissertations and other unpublished literature. In addition, only studies published in English were included in the review. This may account for the overwhelming number of studies emanating from the USA and the limited number of studies conducted in countries, where English is not the first language and should be taken into consideration when interpreting the geographical trends in publication.

It could also be argued that the current review is limited because it only considered studies that included one or more autistic persons reporting on their post-secondary experiences. As a result, studies that consulted exclusively with proxies, rather than directly with the autistic person, were excluded. Although these types of studies have merit, the aim in this review was to investigate the extent to which the international literature reflects autistic experiences in post-secondary education, from the perspective of autistic people. The fact that the ‘voices’ of certain groups of autistic people, such as non-speakers, may have been absent from the review is a criticism of the research methodologies employed and indicative of the need for inclusive, participatory autism research. With this in mind, it should be noted that although this scoping review is part of a wider study involving consultation with members of the autistic community, the team working on this review did not include an autistic co-author or research partner and the analysis and interpretation of the data may be limited as a result.

Future directions

Notwithstanding these limitations, this review has revealed some important insights into research trends on this topic and allowed us to identify important directions for future research. Previous research, which sought the views of the autism community, highlighted a clear consensus that research should focus on areas that impact people’s day-to-day lives, including key issues related to education and employment (Pellicano, Dinsmore, and Charman Citation2014b) and according to Chown et al. (Citation2017), ‘it has been argued that it is both epistemologically as well as ethically problematic if the autistic voice is not heard in relation to social scientific research seeking to further develop knowledge of autism’ (p.721). However, to-date the vast majority of research on autism has been conducted about autistic people, rather than with them, and is driven by a medical model, which relies on a deficit-based understanding of autism and perpetuates an ableist ideology (Bottema-Beutel et al. Citation2021; Chown et al. Citation2017).

Findings from the current review are consistent with general trends in the autism literature. There was an overwhelming absence of inclusive, participatory research within autistic student literature, combined with an extremely limited number of studies focusing on the autistic staff experience. It should also be noted that the experience of ableism can intersect with other systems of discrimination, including racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia (Bottema-Beutel et al. Citation2021). This intersectionality represents an important focus of future research, given that the potentially compounding impact of multiple discriminations on the autistic experience of studying and working in post-secondary educational settings, does not feature strongly in the existing literature.

Participatory research challenges the traditional power imbalance (Fletcher-Watson et al. Citation2019) by replacing it with a reciprocal decision-making partnership between the academic and the persons impacted by the research (Chown et al. Citation2017). According to findings from Pellicano et al. (Citation2014a, 2014b), the autism community in the UK believe that there needs to greater involvement of autistic persons, not only in identifying research priorities but in carrying out the research itself. Therefore, arguably the most important insight from the current review, is the need for greater collaboration with and involvement of the autism community, in order to produce meaningful research on the autistic experience in post-secondary educational settings. To assist with this collaborative process, the team at the Academic Autism Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education (AASPIRE), who have been conducting participatory autism research since 2006, have published guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults as co-researchers and study participants (e.g. Nicolaidis et al. Citation2019, Citation2011, Citation2020). On request, they can also provide support to researchers to help them develop accessible and inclusive research instruments (AASPIRE Citation2020).

Finally, the development of sample sizes should be given consideration in future research. The most common sample size among the included studies was one participant and although qualitative research designs were most commonly used by studies in the review, a sample size of one can hinder the generalisability and applicability of findings. However, future research should avoid prioritising large sample sizes to the detriment of depth of investigation and analysis. Therefore, a balance needs to be achieved. Furthermore, given the sensitive nature of this topic, researchers need to establish trust with potential participants. Exclusively non-autistic research teams can prompt a lack of confidence and faith in research on autism from the autistic community’s perspective (Chown et al. Citation2017), resulting in lower engagement. This is another reason for non-autistic researchers to partner meaningfully with the autism community.

Conclusions

Overall, findings reveal a wider need for research from countries outside the USA and UK and this applies to studies focusing on students, as well as staff. This is consistent with recommendations from a systematic review carried out by A. H. Anderson, Stephenson, and Carter (Citation2017). However, arguably, the most important insight from the current review, points to the need for greater collaboration with and involvement of the autistic community in research that has direct and indirect implications for their lives. This scoping review shows that the majority of research that focused on the experiences of autistic students in post-secondary education, continues to be conducted about them, rather than with them, which can result in a lack of confidence in the research process and outcomes (Chown et al. Citation2017). While this was not the case for studies addressing the autistic staff experience, the limited number of articles is concerning. Therefore, findings support continued calls for greater involvement of the autistic community, from the inception of any research project, which focuses on the experiences of autistic people. Non-autistic researchers should strongly consider partnering with autistic researchers and autistic self-advocates to produce more inclusive, authentic research on the experiences of autistic people.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (42.2 KB)Acknowledgements

This review was one strand of a bigger project and we would like to acknowledge the wider research team, who successfully secured DCU’s Institute of Education’s Collaborative Research Funding Award.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Laura Gormley

Laura Gormley is an Assistant Professor in the School of Inclusive and Special Education at the DCU Institute of Education. Since completing her PhD, which was funded by the Irish Research Council, Laura has been the principal investigator on a number of research projects that have explored ways to enhance the quality of learning experiences for autistic people. The results of these projects have been published in a range of peer reviewed international journals.

Abbie Feeney

Abbie Feeney is an early career researcher, who since completing her masters has worked with adults diagnosed with an intellectual disability.

Sinéad McNally

Sinéad McNally is an Associate Professor at the School of Language, Literacy and Early Childhood Education at the DCU Institute of Education. In her research, Sinéad investigates inclusive educational contexts with a special focus on the role of play and books in children’s learning and development.

References

- AASPIRE (Academic Autism Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education). 2020. What ASSPIRE Can and Cannot Do. May 19. https://aaspire.org/about/faqs/#can-aaspire-help-me-with-my-research.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Anderson, A. M. 2021. “Exploring the Workforce Experiences of Autistic Librarians through Accessible and Participatory Approaches.” Library & Information Science Research 43 (2): 101088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2021.101088.

- Anderson, A. H., M. Carter, and J. Stephenson. 2020. “An On-Line Survey of University Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Australia and New Zealand: Characteristics, Support Satisfaction, and Advocacy.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 50 (2): 440–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04259-8.

- Anderson, A. H., J. Stephenson, and M. Carter. 2017. “A Systematic Literature Review of the Experiences and Supports of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Post-Secondary Education.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 39:33–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2017.04.002.

- Anderson, A. H., J. Stephenson, and M. Carter. 2020. “Perspectives of Former Students with ASD from Australia and New Zealand on Their University Experience.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 50 (8): 2886–2901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04386-7.

- Anderson, A. H., J. Stephenson, M. Carter, and S. Carlon. 2019. “A Systematic Literature Review of Empirical Research on Postsecondary Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 49 (4): 1531–1558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3840-2.

- Ashbaugh, K., R. L. Koegel, and L. K. Koegel. 2017. “Increasing Social Integration for College Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Behavioral Development Bulletin 22 (1): 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/bdb0000057.

- Bailey, Kathryn M., Kyle M. Frost, Karís Casagrande, and Brooke Ingersoll. 2020. “The Relationship Between Social Experience and Subjective Well-being in Autistic College Students: A Mixed Methods Study.” Autism 24 (5): 1081–1092. http://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319892457.

- Bakker, T., L. Krabbendam, S. Bhulai, and S. Begeer. 2019. “Background and Enrollment Characteristics of Students with Autism in Higher Education.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 67:101424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101424.

- Bakker, T., L. Krabbendam, S. Bhulai, M. Meeter, and S. Begeer. 2023. “Study Progression and Degree Completion of Autistic Students in Higher Education: A Longitudinal Study.” Higher Education 85 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00809-1.

- Baldwin, S., D. Costley, and A. Warren. 2014. “Employment Activities and Experiences of Adults with High-Functioning Autism and Asperger’s Disorder.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44 (10): 2440–2449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2112-z.

- Bell, S., C. Devecchi, M. Shevlin, and C. Mc Guckin. 2017. “Making the Transition to Post-Secondary Education: Opportunities and Challenges Experienced by Students with ASD in the Republic of Ireland.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 32 (1): 54–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2016.1254972.

- Bottema-Beutel, K., S. K. Kapp, J. N. Lester, N. J. Sasson, and B. N. Hand. 2021. “Avoiding Ableist Language: Suggestions for Autism Researchers.” Autism in Adulthood 3 (1): 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0014.

- Cage, E., M. De Andres, and P. Mahoney. 2020. “Understanding the Factors That Affect University Completion for Autistic People.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 72:101519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101519.

- Cage, E., and J. Howes. 2020. “Dropping out and Moving on: A Qualitative Study of Autistic People’s Experiences of University.” Autism 24 (7): 1664–1675. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320918750.

- Camarena, P. M., and P. A. Sarigiani. 2009. “Postsecondary Educational Aspirations of High-Functioning Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Their Parents.” Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 24 (2): 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357609332675.

- Câmpeanu, E., D. Dumitrescu, I. Costică, and I. Boitan. 2017. “The Impact of Higher Education Funding on Socio-Economic Variables: Evidence from EU Countries.” Journal of Economic Issues 51 (3): 748–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2017.1359048.

- Casement, S., C. Carpio de los Pinos, and R. Forrester-Jones. 2017. “Experiences of University Life for Students with Asperger’s Syndrome: A Comparative Study between Spain and England.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (1): 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1184328.

- Chown, N., J. Baker-Rogers, L. Hughes, K. Cossburn, and P. Byrne. 2018. “The ‘High Achievers’ Project: An Assessment of the Support for Students with Autism Attending UK Universities.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 42 (6): 837–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1323191.

- Chown, N., J. Robinson, L. Beardon, J. Downing, L. Hughes, J. Leatherland, K. Fox, L. Hickman, and D. MacGregor. 2017. “Improving Research about Us, with Us: A Draft Framework for Inclusive Autism Research.” Disability & Society 32 (5): 720–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1320273.

- Dovigo, F. 2017. Special Educational Needs and Inclusive Practices: An International Perspective. Edited by F. Dovigo. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Fabri, M., G. Fenton, P. Andrews, and M. Beaton. 2022. “Experiences of Higher Education Students on the Autism Spectrum: Stories of Low Mood and High Resilience.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 69 (4): 1411–1429. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2020.1767764.

- Flegenheimer, C., and K. S. Scherf. 2022. “College as a Developmental Context for Emerging Adulthood in Autism: A Systematic Review of What We Know and Where We Go from Here.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 52 (5): 2075–2097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05088-4.

- Fleischer, A. S. 2012. “Alienation and Struggle: Everyday Student-Life of Three Male Students with Asperger Syndrome.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 14 (2): 177–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2011.558236.

- Fletcher-Watson, S., J. Adams, K. Brook, T. Charman, L. Crane, J. Cusack, S. Leekam, D. Milton, J. R. Parr, and E. Pellicano. 2019. “Making the Future Together: Shaping Autism Research Through Meaningful Participation.” Autism 23 (4): 943–953. http://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318786721.

- Gelbar, N., I. Smith, and B. Reichow. 2014. “Systematic Review of Articles Describing Experience and Supports of Individuals with Autism Enrolled in College and University Programs.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44 (10): 2593–2601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2135-5.

- Hamilton, J., G. Stevens, and S. Girdler. 2016. “Becoming a Mentor: The Impact of Training and the Experience of Mentoring University Students on the Autism Spectrum.” PLoS ONE 11 (4): e0153204. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153204.

- Hugo, M., and J. Hedegaard. 2017. “Education as Habilitation: Empirical Examples from Adjusted Education in Sweden for Students Associated with High-Functioning Autism. Andragoška Spoznanja.” Andragoška Spoznanja 23 (3): 71–87. https://doi.org/10.4312/as.23.3.71-87.

- Hummerstone, H., and S. Parsons. 2021. “What Makes a Good Teacher? Comparing the Perspectives of Students on the Autism Spectrum and Staff.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 36 (4): 610–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1783800.

- Jackson, S. L. J., L. Hart, J. T. Brown, and F. R. Volkmar. 2018. “Brief Report: Self-Reported Academic, Social, and Mental Health Experiences of Post-Secondary Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 48 (3): 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3315-x.

- Jorgensen, C. M., K. Bates, A. H. Frechette, R. M. Sonnenmeier, and J. Curtin. 2011. ““Nothing about Us without Us:” Including People with Disabilities as Teaching Partners in University Courses.” International Journal of Whole Schooling 7 (2): 109–126.

- Kenny, L., C. Hattersley, B. Molins, C. Buckley, C. Povey, and E. Pellicano. 2016. “Which Terms Should Be Used to Describe Autism? Perspectives from the UK Autism Community.” Autism 20 (4): 442–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315588200.

- MacLeod, A., J. Allan, A. Lewis, and C. Robertson. 2017. “‘Here I Come Again’: the Cost of Success for Higher Education Students Diagnosed with Autism.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 22 (6): 683–697. http://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1396502.

- Martin, N. 2021. “Perspectives on UK University Employment from Autistic Researchers and Lecturers.” Disability & Society 36 (9): 1510–1531. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1802579.

- McDonald, T. A. M. 2020. “Autism Identity and the “Lost Generation”: Structural Validation of the Autism Spectrum Identity Scale and Comparison of Diagnosed and Self-Diagnosed Adults on the Autism Spectrum.” Autism in Adulthood 2 (1): 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2019.0069.

- The National Autistic Society. 2023. Sensory Differences: A Guide for all Audiences. April 6. National Autistic Society. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/sensory-differences/sensory-differences/all-audiences.

- Newman, L., M. Wagner, A. M. Knokey, C. Marder, K. Nagle, D. Shaver, and X. Wei. 2011. The Post-High School Outcomes of Young Adults with Disabilities Up to 8 Years after High School: A Report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2). NCSER 2011-3005. National Center for Special Education Research. https://ies.ed.gov/ncser/pubs/20113005/pdf/20113005.pdf.

- Nicolaidis, C., D. Raymaker, S. K. Kapp, A. Baggs, E. Ashkenazy, K. McDonald, M. Weiner, J. Maslak, M. Hunter, and A. Joyce. 2019. “The AASPIRE Practice-Based Guidelines for the Inclusion of Autistic Adults in Research as Co-Researchers and Study Participants.” Autism 23 (8): 2007–2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319830523.

- Nicolaidis, C., D. Raymaker, K. McDonald, S. Dern, E. Ashkenazy, C. Boisclair, S. Robertson, and A. Baggs. 2011. “Collaboration Strategies in Nontraditional Community-Based Participatory Research Partnerships: Lessons from an Academic–Community Partnership with Autistic Self-Advocates.” Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action 5 (2): 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2011.0022.

- Nicolaidis, C., D. M. Raymaker, K. E. McDonald, E. M. Lund, S. Leotti, S. K. Kapp, M. Katz, et al. 2020. “Creating Accessible Survey Instruments for Use with Autistic Adults and People with Intellectual Disability: Lessons Learned and Recommendations.” Autism in Adulthood 2 (1): 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2019.0074.

- Packer, R., and A. Thomas. 2021. “Transitions to Further Education: Listening to Voices of Experience.” Research in Post-Compulsory Education 26 (2): 212–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2021.1909925.

- Pellicano, E., A. Dinsmore, and T. Charman. 2014a. “Views on Researcher-Community Engagement in Autism Research in the United Kingdom: A Mixed-Methods Study.” PLoS ONE 9 (10): e109946. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109946.

- Pellicano, E., A. Dinsmore, and T. Charman. 2014b. “What Should Autism Research Focus upon? Community Views and Priorities from the United Kingdom.” Autism 18 (7): 756–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314529627.

- Pesonen, H. V., J. H. Nieminen, J. Vincent, M. Waltz, M. Lahdelma, E. V. Syurina, and M. Fabri. 2023. “A Socio-Political Approach on Autistic Students’ Sense of Belonging in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 28 (4): 739–757. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1852205.

- Pesonen, H. V., M. Waltz, M. Fabri, M. Lahdelma, and E. V. Syurina. 2021. “Students and Graduates with Autism: Perceptions of Support When Preparing for Transition from University to Work.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 36 (4): 531–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1769982.

- Shattuck, P. T., S. C. Narendorf, B. Cooper, P. R. Sterzing, M. Wagner, and J. L. Taylor. 2012. “Postsecondary Education and Employment Among Youth With an Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Pediatrics 129 (6): 1042–1049. http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2864.

- Simmeborn Fleischer, A., M. Adolfsson, and M. Granlund. 2013. “Students with Disabilities in Higher Education – Perceptions of Support Needs and Received Support.” International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 36 (4): 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e328362491c.

- Smagorinsky, P. 2011. “Confessions of a Mad Professor: An Autoethnographic Consideration of Neuroatypicality, Extranormativity, and Education.” Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education 113 (8): 1701–1732. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811111300802.

- Stagg, S. D., and H. Belcher. 2019. “Living with Autism without Knowing: Receiving a Diagnosis in Later Life.” Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine 7 (1): 348–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2019.1684920.

- Strnadová, I., V. Hájková, and L. Květoňová. 2015. “Voices of University Students with Disabilities: Inclusive Education on the Tertiary Level – A Reality or a Distant Dream?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 19 (10): 1080–1095. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1037868.

- Thompson-Hodgetts, S., C. Labonte, R. Mazumder, and S. Phelan. 2020. “Helpful or Harmful? A Scoping Review of Perceptions and Outcomes of Autism Diagnostic Disclosure to Others.” Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 77:101598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101598.

- Thompson, C., S. Bölte, T. Falkmer, and S. Girdler. 2019. “Viewpoints on How Students with Autism Can Best Navigate University.” Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 26 (4): 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2018.1495761.

- Tricco, A. C., E. Lillie, W. Zarin, K. K. O’Brien, H. Colquhoun, D. Levac, D. Moher, et al. 2018. “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation.” Annals of Internal Medicine 169 (7): 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

- UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). 2016. General comment no. 4 (2016), article 24: Right to inclusive education, CRPD/C/GC/4. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1313836?ln=en.

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). 2012. International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED 2011). https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/international-standard-classification-of-education-isced-2011-en.pdf.

- UN General Assembly. 2006. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.refworld.org/docid/4680cd212.html.

- United Nations. 2006. United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations.

- Van Hees, V., T. Moyson, and H. Roeyers. 2015. “Higher Education Experiences of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Challenges, Benefits and Support Needs.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 45 (6): 1673–1688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2324-2.

- Van Hees, V., H. Roeyers, and J. De Mol. 2018. “Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Their Parents in the Transition into Higher Education: Impact on Dynamics in the Parent-Child Relationship.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 48 (10): 3296–3310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3593-y.

- Vincent, J. 2019. “It’s the Fear of the Unknown: Transition from Higher Education for Young Autistic Adults.” Autism 23 (6): 1575–1585. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318822498.

- Volkmar, F. R., S. L. Jackson, and L. Hart. 2017. “Transition Issues and Challenges for Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Pediatric Annals 46 (6): e219–e223. https://doi.org/10.3928/19382359-20170519-03.

- White, S. W., T. H. Ollendick, and B. C. Bray. 2011. “College Students on the Autism Spectrum: Prevalence and Associated Problems.” Autism 15 (6): 683–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361310393363.

- Wright, S., and G. Kaupins. 2018. “What about Us?” Exploring What It Means to Be a Management Educator with Asperger’s Syndrome. Journal of Management Education 42 (2): 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562917747013.

- Zeidan, J., E. Fombonne, J. Scorah, A. Ibrahim, M. S. Durkin, S. Saxena, A. Yusuf, A. Shih, and M. Elsabbagh. 2022. “Global Prevalence of Autism: A Systematic Review Update.” Autism Research 15 (5): 778–790. http://doi.org/10.1002/aur.v15.5.