ABSTRACT

The introduction of tuition fees in Sweden in 2011 is an interesting example of how the design of a tuition fee reform for international students surges beyond simple narratives of revenue generation. More than 10 years after implementing the Swedish reform, this article examines to what extent such market-oriented instruments induce HEIs and the government to seek revenue on the global market. Through a comprehensive analysis, the research employs two theoretical models – the ‘revenue-seeking’ and the ‘cost-sharing and control’ model – to explore the inherent hybridity governance features between market and state-centred objectives. The findings reveal that while the reform primarily adheres to its intended goals of cost-sharing and controlled internationalisation, there is an emerging trend towards revenue generation, particularly in HEIs with strong market positions and in lucrative disciplines like Engineering & Technology and Business Management. The study highlights the reform’s multifaceted impact, aligning with state-centric objectives but gradually shifting towards a revenue-seeking approach. This research contributes to understanding the nuanced effects of tuition fee policies on HEIs and calls for further comparative studies to deepen insights into the diverse outcomes of such reforms in the context of higher education internationalisation.

Introduction

A high number of globally mobile students poses both opportunities and challenges for governments and Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), sparking debate over the role of international students. Are they valuable contributors warranting public investment, threats to ‘national characteristics’, or simply revenue sources?

Tuition fee reforms for international students are commonly seen as expressions of the latter perspective, encapsulating academic capitalism, compensating for reduced state allowances and a trend towards marketisation in the HE sector (Cantwell Citation2015; Lunt Citation2008; Slaughter and Rhoades Citation2004). However, tuition fee reform objectives can also stem from a broader set of political considerations linked to public funding for international students.

The 2011 Swedish tuition fee reform for non-EU students was motivated to compete with quality, not free education. Moreover, it was designed to regain state control over the influx and public expenditure on international students. Offering free education for all international students was argued unsustainable in that a continuous increase of this student group would displace national students threatening publicly funded education for national students. It sought cost-neutral internationalisation for Swedish taxpayers by sharing costs with international students, blending tuition fees and scholarships, aligning expenditure with goals like attracting top talent and aiding students from low-income countries. Additional revenue generation was not an explicit objective, and the reform was not triggered by significant cuts in state funding (Lundin and Geschwind Citation2023). Hence, the Swedish reform constitutes an interesting example of how the design of a tuition fee reform for international studentsFootnote1 is characterised by hybridity of policy objectives staining from market-oriented as well as state-centric logic (Gornitzka and Maassen Citation2000).

Swedish HEIs were left plenty of freedom to implement the reform as autonomous actors, in which HEIs were free to set their prices according to the rather abstract ‘full cost coverage’ principle, meaning that the price would reflect direct and indirect costs of the student, but not generate a surplus (Lundin and Geschwind Citation2023).

More than a decade after its implementation, this article investigates the impact of the Swedish reform of the national approach to international student recruitment. Employing theories of academic capitalism and systematic change of policy implementation, the study examines how market-oriented behaviours within HEIs and evolving policy objectives have influenced the reform’s trajectory. The question addressed is: How has the Swedish tuition fee reform affected the national approach to international student recruitment, balancing between market-oriented behaviours and state-centric objectives?

A dual-level analysis on both the government (macro) and HEI (meso) level is performed to assess not only how HEIs respond to the policy but also how politicians have followed up to achieving its stated goals of sharing costs and control internationalisation. This allows for a greater understanding of tuition fee reforms from a broader governance perspective. By focusing on the policy instrument mix of scholarships and regulations within the reform (Howlett Citation2014), this study employs an analytical framework of the two models – ‘revenue-seeking’ and ‘cost-sharing and control’ – to dissect the embedded interplay between market forces and state-centric objectives in the Swedish reform.

Conceptual framework

Nordic perspectives on tuition fee reforms for international students

The HE systems in Nordic countries, renowned for their commitment to global equity and provision of free education for all students, have undergone significant shifts with the introduction of tuition fees for international students. This marks a transition towards a greater emphasis on the global student market while maintaining HE as a cornerstone of their welfare systems, but now limited to ensuring free education for national students. The transition started with Denmark in 2006, followed by Sweden in 2011, Finland in 2017, and Norway in 2023.

In Sweden, prior to the reform, there were concerns among HEIs, student unions and industry stakeholders about the potential adverse impacts on diversity, equality and competitiveness (Westin and Nilsson Citation2023). Post-reform qualitative analyses indicate that Swedish HEIs have prioritised academic quality over profit in their perception of international students (Nordensvärd and Ketola Citation2019; Rickmann Citation2021), although critics like Bryntesson (Citation2018) argue that the reform fell short of achieving its cost-neutral objectives. The number of international students are almost similar as prior reform, but a decrease from low-income countries indicates that scholarships have not been sufficient to facilitate access for students from low-income countries (Nilsson and Westin Citation2022).

Finland’s approach contrasts with Sweden’s in that the policy problem was more explicitly linked to budget cuts, with an objective to transform HE into an export product (Kauko and Medvedeva Citation2016). HEIs themselves determine the amount of the tuition fees they charge. However, the amount of the fee must be at least €1500 per academic year (Ministry of Education Citation2022).

Norway’s recent introduction of tuition fees differs from the Swedish cost-sharing and control model in that high fees was not complemented by accompanying scholarship schemes. Similarly as Sweden, the main rationale behind Norway’s reform was primarily to free up study places for domestic students, but with a more explicit argument that tuition fees was to complement budget cuts in the sector (Liu and Solheim Citation2023).

In Denmark, likewise Sweden, the approach was primarily addressed by welfare protectionism logic. A difference is that Denmark imposes caps on international student numbers, reflecting concerns about preserving national characteristics in HE (Tange and Jæger Citation2021). Hence, ambitions to transform HE as an export product in Denmark has not been a priority.

Tuition fees as policy instrument of cost-sharing or revenue

Tuition fees are not prices similar to those set in a normal market with the aim to perform profit. HEIs operate in a sector that in most contexts is non-profit. Tuition fees are commonly regulated by the government and public funds play a significant role to supplement tuition fees since HE is considered of great importance for society (Jongbloed Citation2004; Marginson Citation2011). This creates a ‘cost-sharing’ financial structure between private and public funds (Johnstone Citation2004); and state regulations on how tuition fees can be applied generate a ‘quasi-market’ in HE (Teixeira et al. Citation2006).

There are four common arguments for applying a cost-sharing system between taxpayers and private funders in a national HE setting. Firstly, prioritising public support to students from weaker socioeconomic backgrounds while students from stronger socioeconomic backgrounds pay for themselves is argued to be a more justified and efficient tool to re-distribute societal wealth (Marcucci and Johnstone Citation2007). Secondly, HE is expensive; governments must find additional funding to support a massified system. Therefore, the student pays a share of the educational cost while the rest is substituted by public means (Johnstone and Marcucci Citation2010). The other two arguments origin from more neo-liberal ideological standpoints. The introduction of a quasi-market stimulates efficiency since HEIs are required to compete for resources. Furthermore, HE is perceived as a private rather than a public good, i.e. the individual student is the primary beneficiary of HE and should therefore pay a large share of it (Marginson Citation2011; Tilak Citation2008).

All these arguments were explicit in the Swedish policy formulation phase motivating the objective to control and share costs of the internationalisation of the Swedish HE sector. In the formulation phase, the cost-sharing perspective was framed from two perspectives. The national and international cost sharing of internationalising Swedish HE, but it interestingly also redistributes funds among international students studying in Sweden. With the new system, international students who can afford their education pay tuition, leading to that public funds instead could be channelled to increased scholarships for students from lower-income countries, thus enhancing access for this student group (Lundin and Geschwind Citation2023). Using policy instrument mix of tuition fees and scholarship can also arguably be more effective in assuring equity in terms of access to HE systems (de Gayardon Citation2017). This approach offers a notable perspective on the role of tuition fee reforms in the broader discussion of international aid in HE (Rensimer and McCowan Citation2023).

International students and dual-track tuition fee systems

Tuition fee reforms targeting international students have different characteristics than national tuition fee reforms. The former typically implicates a dual-track tuition fee system in which international students pay substantially higher tuition fees than national students. A prime example of this is found in the Nordic countries. This opens up a new set of factors to understand these types of reforms from an internationalisation context.

From an overarching perspective an international-national student-based dual-track system emphasise the tension between the ‘national’ and ‘global’ in HE policy, and how HE relates to welfare protectionism. Furthermore, tuition fees for international students open up a new source of funding stemming from a seemingly unlimited global scale.

Generating revenue has become an increasingly important aspect of recruiting international students in many European countries (Seeber et al. Citation2016). Some scholars even express how this group is treated as ‘cash cows’ (Cantwell Citation2015); ‘turning internationalisation to an industry’ (Altbach and de Wit Citation2023). This could be interpreted by resource dependency theory as well as by academic capitalism. Resource dependency theory suggests that organisational behaviour depends on the resource environment (Salancik and Pfeffer Citation1978). Thus, when external resources change, HEIs have to adapt to these new conditions. Hence, there is a close connection between funding policies at the national level and the response at the institutional level. Reducing state allowance to the HE sector has also been an explanatory factor for why revenue generation has become important for recruiting international students for Anglo-Saxon HEIs (Cantwell Citation2015). From this perspective, HEIs would become dependent on tuition fee revenues, given that state allowances are reduced.

Academic capitalism theory posits that HEIs increasingly view international students as revenue sources, emphasising financial gain over academic contributions. This approach leads HEIs to continually seek income from international students for organisational growth, regardless of other financial factors (Cantwell Citation2015; Slaughter and Rhoades Citation2004). Originating mainly from the Anglo-Saxon context, where international students are vital for financial stability, this tendency impacts tuition fee strategy. HEIs in these regions set fees based on market position, reputation and export orientation, not primarily cost-based calculations (Naidoo et al. Citation2022). This student-as-customer model results in steadily rising tuition fees, prioritising revenue over academic integrity or social equity, which might not be optimal for the quasi market to be effective (Bertolin Citation2011). To overcome these perceived market failures to deliver HE as a public good it is common that governments use policy instruments, such as fee caps to control HEIs tuition fees, and balance profit-seeking behaviour (HEPI Citation2023; Mintz Citation2021).

Revenue and cost-sharing models

Based on contrasting perspectives on international student recruitment (Lundin and Geschwind Citation2023) and the interplay of market and state control mechanisms in HE governance within quasi-markets (Agasisti and Catalano Citation2006), this article outlines a framework of the: ‘revenue-seeking’ and the ‘cost-sharing and control’ model. These models establish an analytical lens for understanding market-type solutions in reforms and shed light on the multifaceted nature of the Swedish tuition fee policy.

The cost-sharing and control model

The cost-sharing and control model integrates elements from the ‘centralistic’ model as described by Agasisti and Catalano (Citation2006), where the state is the primary financier and controller of education. It also aligns with Clark’s (Citation1983) notion of ‘state control’, where HE serves as a tool for achieving government objectives in political, economic, or social realms. This synthesis suggests a governance approach where state involvement is pivotal in steering educational directions and outcomes.

Under the ‘cost-sharing and control’ model governments recognise international students as a ‘public good’ (Marginson Citation2011). This student group is key for global competitiveness and skilled migration, often termed a ‘global race for talents’ (Docquier and Machado Citation2016). Global student exchanges and capacity building are also linked to global equity aspects in HE and soft power (Lomer Citation2017; OECD Citation2008); features that were particularly articulated in the policy formulation phase of the Swedish reform.

The role of tuition fees in this context is to accommodate an increasing number of international students without escalating costs or risking the displacement of national students. To this end, it is imperative that fees should cover costs, without being excessively high. High fees are contra-productive since it create financial barriers, restricting access to the HE system for this group. Public-funded scholarships are important to assure effectiveness in achieving policy objectives related to internationalisation such as redistribution of funds from ‘rich’ to ‘poor’ international students, as well as to share costs of internationalisation.

For HEIs international students enhance academic quality and add international prestige (Knight Citation2013; Seeber et al. Citation2016). Thus, HEIs are dependent on international students to be prestigious organisations with a high academic content. In the cost-sharing and control model HEIs has no interest in raising tuition fees more than necessary to sustain actual costs, to make their organisations attractive for this student group.

The revenue-seeking model

The revenue-seeking model, influenced by Agasisti and Catalano’s market approach, portrays HEIs, like private businesses, autonomously determining their service pricing without state interference. Aligned with Clark’s ‘free market’ concept, this governance style resembles a ‘supermarket steering model’, where the state’s role is significantly reduced, since private sector actions are generally more efficient, effective, or fair compared to public sector interventions (Gornitzka and Maassen Citation2000).

This approach is firmly rooted in the realm of academic capitalism, bolstered by the worldwide embrace of neoliberal economic policies and the advent of globalisation. It aligns with the WTO’s perspective, interpreting HE as a tradable commodity, thus transforming its perception from a public to a private good (Tilak Citation2008). In many Anglo-Saxon countries, the recruitment of international students makes part of explicit export strategies to generate revenue for the country. As an example, in Australia HE related services account for 8,5% of the total export is a major export for the economy (OECD Citation2008). Since international students primarily are perceived as revenue, there is limited interest in sharing costs of internationalisation through scholarships.

At an organisational level, a large global student market drives HEIs to adopt entrepreneurial approaches. International students are primarily seen as a source of income for HEIs, essential to support overarching operations within the organisation. HEIs tend to adopt a proactive stance in leveraging tuition fees as a strategic tool to maximise revenue and strengthen their competitive position in the international student market. This model is characterised by dynamic pricing strategies that are responsive to market trends and student preferences, often reflecting a higher degree of market orientation and export orientation. For some HEIs revenue generated from international students is a complete lifeline, and for others just a nice add-on (Naidoo et al. Citation2022). As an example, in the UK, approximately 20% (2020) of HEI’s total income stains from international fees, compared to 10% in 2009 (OFS Citation2022), as HEIs increasingly see international students as a good source of income. In Australia the same share was approximately 27% in 2020, in comparison to 15% in 2004. Some estimates in the case of Australia suggest that as much as 27% of the country’s total research expenditure, or about $3.3 billion, relies on profit from international students (Norton Citation2020). There are though differences within the national setting, Business & Management and Engineering & Technology represent the major part of this revenue (Cannings, Halterbeck, and Conlon Citation2023).

Policy reforms subject to systematic change

The outcome of a reform is commonly subject to systemic change due to a dynamic, iterative process between HEIs and the government (Paradeise, Reale, and Goastellec Citation2009; Pressman and Wildavsky Citation1984). As Lascoumes and Le Galès (Citation2007) argue, policy instruments are bearers of values and underlying ideological standpoints. Thus, the launch of a reform that translates international students into ‘paying clients’ might have subtle effects of internationalisation. Assumptions of academic capitalism also suggest that HEIs will seek revenue whenever possible. Politically at governmental level, capitalising on the global student market to bolster the national HE budget might become increasingly appealing (Sanchez-Serra and Marconi Citation2018). Consequently, embracing a dynamic view of policy evolution, which acknowledges the fluidity and adaptability of policy implementation at both national and organisational levels, is crucial for a thorough understanding of a policy’s lifecycle (Jungblut and Vukasovic Citation2013; Reale and Seeber Citation2013).

Method

This study employs an embedded case study design, focusing on the Swedish tuition fee reform at both national and organisational level, using multiple data sources for comprehensive depth (Yin Citation2018). The empirical material includes official data on the funding composition of the Swedish HE landscape from 2011 to 2022, comprising annual reports from HEIs, governmental budget bills, regulatory letters and statistics from the Swedish Higher Education Authority (UKÄ).

Secondary sources, such as official reports, public inquiries and academic literature, triangulate the data and contextualise the Swedish tuition fee reform. This also allows to incorporate a broader analysis of the economic and socio-political context in the aftermath of the reform. This can include factors like economic pressures, political changes, or societal attitudes towards HE funding.

The collection of the data at the organisational level, as presented in , was limited to the 15 HEIs with the highest share of the revenue from tuition fees, out of 33 HEIs in Sweden. All major Swedish HEIs are included among these 15. Among the remaining HEIs the amount of fee-paying students are almost non-existing. A brief examination of the tuition fee levels indicates that these are neither much higher nor lower than HEIs included in this study. A longitudinal analysis to observe trends over time is also included. The comparison over time was limited to 2013, 2017 and 2022 in order to bound the material to a more manageable amount.

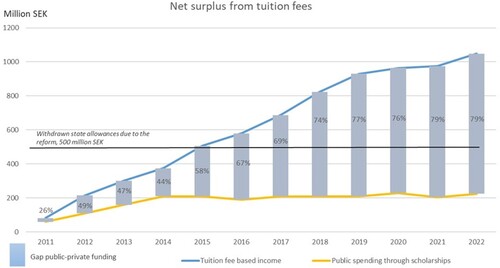

Some of the data were derived directly from the empirical material, such as ‘level of state allowances’, ‘revenue generated from tuition fees’, ‘public funds invested in scholarships’ and ‘accumulated surplus generated from tuition fees’. Other data were generated by the author. For example, the ‘national net surplus’, presented in Graph 1, was calculated by subtracting income generated from tuition fees by HEIs minus government-funded scholarships. The ‘supplement charge’ of the tuition fees was estimated based on tuition fees for the educational offer, in comparison to the amount HEIs would receive in terms of state allowances for the same educational offer for national students.

A limitation of the study design is the lack of in-depth data like interviews, which are not included to maintain a comprehensive approach. Additionally, reliance on HEIs’ self-calculated accumulated surplus from annual reports introduces potential subjectivity in cost assessments.

Operationalising the framework

At the macro level, the analysis centres on public-funded scholarships as an instrument for achieving objectives related to cost-sharing and controlling internationalisation. The extent of these scholarships is indicative of whether the policy aim is cost-sharing or revenue-seeking. This is assessed by evaluating the net surplus at the national level, which is calculated as the tuition fee revenue minus the public-funded scholarships.Footnote2 A high net-surplus indicates a revenue-seeking approach to student recruitment. Further examination involves how public scholarships are allocated, their sources, and changes in state allowances to understand the financial impact of the reform. A decrease in state allowances over time might suggest a shift towards utilising the reform for funding generation within the Swedish higher education system. Government documents and regulatory adjustments post-2011 reform are also analysed for insights into its underlying rationale.

At the organisational level, the focus is on how individual HEIs operationalise the reform, primarily in two areas:

Tuition fee pricing strategies: This includes determining whether HEIs set fees to cover costs or to generate surplus revenue. The ‘supplement charge’ – calculated as the tuition fee for an educational programme compared to the state allowance for a national student given to the same programme – is a critical indicator in this analysis. A higher supplement charge might imply a revenue-seeking behaviour. Although a high supplement charge could be justified as necessary for maintaining a high-quality educational environment it provides an indication to what extent fee reflect the direct educational costs.

Revenue management: The management of surplus generated from tuition fees is examined to understand the institutions’ financial strategies and priorities. If an accumulated surplus is used to support overarching operations this indicates a ‘revenue-seeking’ behaviour, whether used to lower tuition fees or as a buffer against future deficits situates at the ‘cost-sharing model’.

An important note by the author is that no single of these factors can easily categorise an actor’s behaviour into one of the analytical models. However, by integrating all data in the analysis, in addition to contextual information, a comprehensive understanding of the operational models of HEIs post-reform can be developed ().

Table 1. Operationalisation of the ‘revenue-seeking’ and ‘cost-sharing and control’ model.

Results

The net surplus at national level

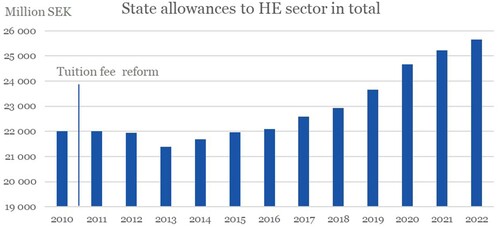

Prior to the reform, an estimated 500 million SEKFootnote3 of state allowances were tied to international students. The same amount was gradually withdrawn from the state allowances as part of the reform but re-invested in the Swedish HE sector elsewhere. Nonetheless, despite this, state allowances (after the reform excluding international students) have increased and are in fact higher than prior to the reform, as shown in . Thus, there has been no overarching public cuts to the HE sector in general due to the reform. This indicates that the reform has not led to a shift in the overarching funding strategy of the HE sector by the government.

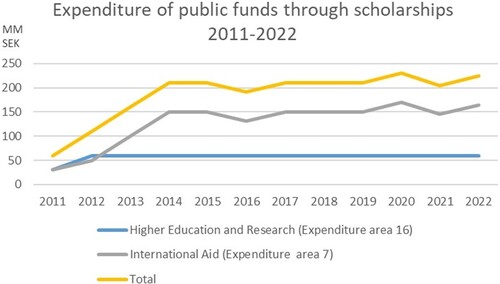

In 2022, public spending on international students, through scholarships, reached a total of 225 million SEK, not even half of the estimated amount of public spending towards international students prior to the reform. In relation to state allowances, public spending on international students only constituted 0.8%Footnote4 in 2022, as compared to approximately 2%, prior to the reform.Footnote5

In the first years after the launch of the reform, the number of international students dropped significantly. Consequently, the tuition fee revenue was also very modest, 84 million SEK in 2011, corresponding to only 0,3% of the total funding for HE. Over the years, the number of international students has constantly increased and in 2022 Swedish HEIs generated more than 1 billion SEK from tuition fees, corresponding to 3% of its total revenue (UKÄ Citation2023). Nevertheless, the actual amount of foreign funds generated from tuition fees is, in fact, less than what these numbers suggest, since a large proportion of the funds generated by HEIs through tuition fees stems from Swedish tax-funded scholarships. illustrates how the net surplus from tuition fees has evolved in Sweden since the launch of the reform.

As becomes evident by the illustration in , the net surplus from tuition fees has gradually increased. In 2011, 74% of the revenue generated from tuition fees stemmed from Swedish public funds. Only 26% of the revenue was generated by foreign funds. The total funds generated from international students reached the same amount, 500 million SEK as was withdrawn state allowances, in 2015 and has despite the Covid-19 pandemic continued to increase.

In 2022, the relation between public and foreign funds was almost reversed as compared to the first years of the reform. Almost 80% of the funding was derived from external means, and only 20% was supported by Swedish public funds. This changed funding composition is due to a gradual increase in fee-paying students, while public spending through scholarships has in relation to this increase been relatively constant. This development corresponds to some extent with the government’s objective to share the costs of internationalisation, and to further increase the number of international students without further costs for tax-payers. However, to fulfil the aim with the cost-sharing logic of further increasing the amount of international students, current public spending of international students would arguably have been at the level prior to reform, 2%, as compared to actual spending in 2022, 0.8%. Furthermore, if this trend continues, net-surplus from tuition fees will reach a point beyond a reasonable cost sharing, implicating that a revenue-seeking model would be a better fit according to the analytical framework.

Controlling funds and influx through scholarships

The Swedish government has for a long time had an explicit aim to increase the number of international students in Sweden, as skilled migration, provide quality to Swedish HE, a means of soft power, and for egalitarian reasons (prop. 2004/05:162; prop. 2008/09:175). These official objectives why to recruit international students have not changed with the reform. As an example, in the Swedish Export Strategy from 2015 (CitationSkr. 2015/16:48) the government further emphasises the important role of international students in the Swedish economy both as skilled migration for students remaining in Sweden and as tools to enable Swedish export deals for those returning to their home countries.

The government anticipated that the launch of tuition fees would significantly decrease the number of international students, and public funding through scholarships was outlined as an essential component of the reform, as stated in the bill.

The government’s goal is that a continued large number of foreign students should study at Swedish universities even after the introduction of tuition fees. This is important for attracting knowledge and competence to Sweden and a central aspect of the internationalisation of Swedish higher education. According to the government’s view, a crucial condition is that there is access to scholarships for foreign students. The intention is partly to generally maintain a high level of the number of incoming foreign students, and partly to enable students from developing countries to study at Swedish universities. (Prop Citation2009/10:65.7)

As can be observed in , the majority of the funding derives from the international aid budget, and exclusively target students from low-income countries. These scholarship schemes cover both tuition fees and living expenses. Scholarships derived from the HE budget target academic quality but only cover the tuition fee, not living expenses. Notably, there are no scholarship schemes available for academically talented students, covering living expenses. Swedish HEIs have also argued that attractive scholarship schemes covering living expenses are required if they are to compete for the most qualified students, regardless of origin.

Despite high ambitions by the government to combine the reform with significant scholarships, Swedish HEIs have pointed out that a lack of scholarships makes it difficult to attract large volumes of international students to Sweden (Oxford Economics Citation2020; UKÄ Citation2017). In 2017, the government launched a public inquiry to propose a new national strategy for internationalisation. The inquiry re-confirmed the importance of publicly funded scholarships to reach the objective of increasing the number of international students in Sweden, but concluded that the number of scholarships should increase to fulfil this objective. The inquiry emphasised the significance of international students for Swedish society and that ‘[A]n obvious measure for HEIs to under the prevailing conditions improve its competitiveness is to be able to offer favourable scholarships’ (SOU Citation2018, 78, p. 294).

The inquiry also observed that the amount of funding derived from the HE budget was very limited and that there was a clear lack of attractive scholarships for students, solely based on merit. An additional 177 million SEK for scholarships was proposed by the inquiry. However, the government has not followed up on this request, and there have not been any new scholarship schemes. Nonetheless, as can be observed in the public spending derived from the HE budget has been rather constant, while the international aid budget has gradually increased. In 2022, totally 225 million SEK of public funds were spent on scholarships, which is almost four times higher than the first year after the reform was launched. Thus, although the net surplus has significantly increased over the years, the fact that public spending continues to increase indicates that the government operates within a cost-sharing model.

The major share of public funds invested in international students stems from the international aid budget. Consequently, because of the reform, parts of the international aid budget now go directly to Swedish HEIs covering tuition fees. Considering that the government emphasised the importance of maintaining a high number of international students from low-income countries after the reform, it is understandable that the amount targeting this group is relatively high. However, the fact that the international aid budget now directly supports the national HE sector highlights relevant questions as to how national aid budgets in relation to HE should be reported (Rensimer and McCowan Citation2023). Furthermore, as Nilsson and Westin (Citation2022) highlight, scholarships have not been sufficient to fulfil the aim of increasing the access of international students from economically weak countries. These results suggest that policymakers in the formulation phase might have presented these arguments to make the reform appear more from within the then current Swedish egalitarian perspective of HE, rather than an actual instrument to actually improve global equity.

What makes this further interesting is that scholarship funding derived from the international aid budget has been exposed to fluctuations. Except that the amount constantly shifts, the scholarship schemes funded by international aid have also been re-designed and influenced by political considerations. As an example, in 2016 scholarship funds were temporarily decreased by 19 million SEK, since international aid funds were reallocated to handle the impact of the 2015 European ‘migration crisis’. Another example is that eligibility criteria for these scholarships have changed over the years, e.g. country of origin. This indicates that through the reform the government has used scholarships as tool to control both public spending and the influx of internationalisation.

The implementation at the organisational level

As illustrated in , income from tuition fees among HEIs has constantly increased since the launch of the reform. Even so, tuition fees are only a marginal income source for Swedish HEIs. Nevertheless, the distribution among HEIs is relatively sparse. Four HEIs (KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Uppsala University, Chalmers Technical University and Lund University) generated more than half of the total national tuition-fee revenue. These more ‘successful’ HEIs raise as much as 7–10% of their total HE funding from tuition fees. Similarly, as in Anglo-Saxon countries, HEIs with high ranking or/and a disciplinary focus on Engineering & Technology or Business & Management have higher revenue shares.

summarises the data compiled from 15 Swedish HEIs illustrating the share of revenue, supplement charge and accumulated surplus derived from tuition fees.

Table 2. Summary sheet of data generated at organisational level.

When the Swedish Higher Education Authority in 2017 sent out a survey asking how HEIs calculate tuition fee prices, it showed that HEIs uses the amount of state allowances provided for the same educational offer for national students, adding a supplement charge (UKÄ Citation2017). HEI’s supplement charges commonly include:

Student counselling

Economic administration

Marketing and recruitment

Reception and service

Despite explicit instructions by the government to apply a cost-based price-setting model, the same survey also showed that some HEIs considered prices of other comparable HEIs, both in Sweden and abroad, when price-setting the tuition fee. The primary reason for applying market-oriented aspects in their price-setting calculations was that these HEIs wanted to signal high quality with a high price, fearing that a ‘low’ price would signal low quality (UKÄ Citation2017).

The data from this study also suggests that a market-oriented pricing model may influence tuition fees. Within Engineering & Technology related fields, the supplement charges range from as low as 1% to as high as 38% among HEIs. However, compared to HE systems without tuition fee caps for international students, like those in the UK and US, Swedish HEIs show relatively minor variations in tuition fees and no significant correlation between high fees and ranking.

Nonetheless, comparing Sweden’s smallest and biggest technical universities provides an interesting insight to analyse differences in supplement charges further. In 2022, the smaller and lower-ranked Blekinge Technical University (BTU) charged an annual fee of 120,000 SEK for their engineering master’s programmes towards international students, with the lowest supplement charge among examined HEIs, 11%. As a comparison, the bigger and highly ranked KTH charged 155 000 SEK for their engineering master’s programmes the same year, implicating a 31% supplement charge. Whether one HEI has set a supplement charge too low, indirectly financing international students through state allowances, or the other HEI too high, raising funds beyond the international students’ actual cost, is difficult to assess. However, it is not likely that the additional cost to receive and recruit international students is so much higher at KTH. Instead, it appears as if these two HEIs have interpreted ‘full cost coverage’ differently, probably based on their different conditions to compete in the global student market. This raises questions that the tuition fee reform for HEIs with good conditions to recruit tuition fee-paying students might be tempted to charge tuition fees beyond the actual cost of the students.

So, what does KTH include in this relatively higher supplement charge? KTH has the highest share of revenue from tuition fees among all Swedish HEIs, 12% in 2022. According to KTH’s own accounts, approximately 20% of the supplement charge was used for other things than recruitment and administration directly related to tuition-fee paying students (Universitetsläraren Citation2017). Furthermore, except for a relatively high supplement charge, KTH has also had a rather large accumulated surplus, as high as 48 million SEK in 2020. In order to reduce this surplus ‘quality improvement investments’ was launched in the following years. This is why the accumulated surplus decreased by almost 15 million SEK from 2020 to 2022. Considering that tuition-fee-paying students study alongside national students at KTH it is difficult, if not impossible, to isolate such investments to tuition-fee-paying students only.

According to HEI’s annual reports, other HEIs with significant accumulated surplus seem to reason and act similarly. Various HEIs report that re-investing the accumulated surplus into the organisational operations is a feasible measure to reduce the accumulated surplus and comply with the ‘full cost coverage’ requirement.

These results indicate that HEIs might be tempted to seek revenue to support overarching operations. Arguably, according to a cost-based price model, lowering tuition fees and decreasing the supplement charge accordingly, would have been a more accurate measure to reduce accumulated surplus. There are also other interesting examples how HEIs with a strong international brand use parts of the supplement charge to create their own scholarship schemes for tuition fee students. In this case, some international students indirectly pay for other international students. This is also an arguably generous interpretation of the full cost coverage requirement. Although this might not be interpreted as an apparent revenue-seeking behaviour, it is interesting to note that there has been a gradual policy change and an outcome not addressed in the design of the reform.

On the other hand, the supplement charge as summed by all 15 Swedish HEIs has decreased over the years, from 27% in 2013 to 23% in 2022, possibly correlated to the fact that the accumulated surplus has continuously increased. A revenue-seeking behaviour would on the contrary suggest that as HEIs are successful in recruiting international students and raise funds, the supplement charge would increase. Another interesting result is that all examined HEIs are consistent in that the supplement charge strongly relates to the study field of the educational offer. As presented in , social sciences have the highest supplement charge, followed by Engineering & Technology. Within social sciences, Business & Management educational offers have the far most extensive supplement charge. Most programmes apply a 50–60% supplement charge to this educational offer, and as much as 70% in some cases. The difference is striking compared to design-related study fields, which have lower tuition fees than what is provided for national students in state allowances.

Table 3. Supplement charge based on study fields.

These figures show how HEIs are forced, or willing to adapt to the global student market. Some years after the implementation of the reform, HEIs experienced that it was difficult to compete with high tuition fees within some disciplines, risking to affect the possibilities to receive international students from less compatible subject areas. The government, therefore, clarified to HEIs that the compliancy of the full cost coverage would regard the HEIs as a whole over time, providing a more dynamic price-setting related to each discipline. There has not been any other adjustments or clarifications from the government on how to set prices, use surplus or interpret the full cost principle.

Similarly to what literature suggests, study fields within Engineering & Technology, and Business & Management seem to stand strong on the competitive market, allowing for high supplement charges. Regardless, whether HEIs add high supplement charges in these fields to maximise revenue or simply compensate for other ‘weak’ disciplines, it is clear that implementing a market-oriented reform also affects HEIs price-setting strategies in relation to disciplines.

A notable contrast emerges when further comparing technical universities. Luleå Technical University, which ranks higher than BTH, generates less than 1% of its revenue from tuition fees, as compared to BTH’s 8%. Luleå’s supplement charge lies between those of KTH and BTH. The university’s annual report attributes this limited revenue and tuition fee-paying students to the absence of targeted international recruitment efforts. The disparity underscores the broader flexibility afforded by relatively high state allowances in the Swedish HE sector and differing levels of institutional ambitions. While BTH probably opts for a more ambitious approach to international recruitment, Luleå appears content with its current level of international student enrolment primarily based on EU and exchange students.

The issue of cost-neutrality

Half of the OECD countries have no available studies on the economic impact of international students (OECD Citation2008). Neither did Sweden before the reform. Initially overlooked, recent economic calculations underscore the pivotal role of international students in bolstering the Swedish economy and the HE sector’s prominence as a dynamic driver of economic growth and job creation.

Some estimates suggest that the total international student body direct economic contribution at around 4 billion SEK in 2021, out of which fee-paying students contribute half this amount (Swedish Institute Citation2022). Notably, tuition fee-paying students, only a subset of the international student body, which also contains EU and exchange students, have boosted their economic contributions from 300 million SEK in 2011 to 1.9 billion SEK in 2022. As a comparative example, the famous Swedish music export amounted to 2.7 billion SEK in 2019. Nonetheless, only 30 percent of tuition fee-paying student’s economic impact comes from tuition fees, with the remainder attributed to their subsistence expenditures. Additionally, international students’ major contribution is still to be made after their graduation as part of the labour force (Swedish Institute Citation2022).

Despite highlighted economic contributions of international students, there has been limited debate in Sweden about how post-reform outcomes align with the original goals of cost-neutrality, cost-sharing and egalitarianism. The absence of regulatory adjustments and government follow-up to ensure HEIs comply with the ‘full cost coverage principle’ suggests implicit prioritisation of marketisation and revenue generation in the reform’s trajectory, rather than to assure a ‘cost-neutral’ increase of internationalisation. The growing adaptation to increasing funding may explain HEIs limited interest in addressing tuition fee and scholarship structure limitations for competitiveness and equality in a post-reform context.

Recent cost–benefit analyses in Denmark and Finland also highlight the economic benefits of international students as valuable human capital. In Finland, actions to increase the stay-rate of international students are ongoing, yet political measures are simultaneously planned to raise tuition fees and tighten immigration rules for these students (Myklebust Citation2023). Similarly, in Denmark, the Netherlands, Australia, Canada and the UK, contemporary political approach to international students seems to be more focused on anti-immigration policies rather than their economic contributions to the HE sector or the broader economy, despite the Anglo-Saxon HE sector’s heavy dependence on tuition fees (De Wit Citation2024).

Thus, the political approach to international students can be framed as an opportunity, as well as a threat. Analysing tuition fee reforms from a policy instrument perspective provides less normative assumptions that such reforms inherently draw on academic capitalism or reduce global equity. Understanding these reforms requires examining the mix of policy instruments such as caps, regulations, and scholarships embedded within them. However, employing tuition fee reforms for goals beyond revenue generation – such as cost-sharing in internationalisation or enhancing global equity – necessitates active follow-up and a strong political will to use scholarships and regulatory measures effectively. Empirical evidence suggests that this political will is probably lacking.

Conclusions

This article has aimed to explore the tuition fee reform for international students in Sweden as a multifaceted policy, introduced against the backdrop of increasing global student mobility and varying perspectives on international students. By delineating the ‘cost-sharing and control’ and ‘revenue-seeking’ models, the article has illuminated how the reform has affected Sweden’s national approach to international student recruitment.

The reform’s persistence in not reducing state allowances to the HE sector, coupled with the consistent increase in publicly funded scholarships, underscores the continued relevance of its original design for cost-sharing and controlled internationalisation. This finding aligns with the introductory argument that tuition fee reforms can serve broader objectives beyond mere revenue generation, as suggested by Lundin and Geschwind (Citation2023).

Simultaneously, the increasing revenue from international students and the growing net-surplus at the national level hint at a gradual shift towards a revenue-seeking approach, particularly among prestigious HEIs and lucrative disciplines like Engineering & Technology and Business & Management. This trend, while still limited, indicates a gradual change towards revenue-seeking approach to international student recruitment, corroborating Bertolin’s (Citation2011) insights on that market-oriented reforms require active government interventions to achieve effective impact on internationalisation strategies.

Moreover, egalitarian arguments to improve access for students from weaker economic backgrounds seem to fall short, as the number of students from low-income countries has decreased. The redirection of international aid funds to cover tuition fees instead of supporting low-income country students with state allowances raises critical questions about donor commitments and the influence of HE aid on the educational systems in the Global South, as pointed out by Rensimer and McCowan (Citation2023).

In conclusion, this study confirms the Swedish tuition fee reform as a hybridity of market-driven and state-centric objectives, maintaining cost-sharing and internationalisation goals while leaning towards revenue generation. This complex scenario calls for more in-depth research to understand its broad effects on HEIs identity, disciplines, and funding compositions, both within Sweden and globally. Policymakers and educational stakeholders should note without active evaluation and intervention a gradual shift towards prioritising revenue in student recruitment strategies might occur.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (184.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (170 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s). This article has been published under the Journal's transparent peer review policy. Anonymised peer review reports of the submitted manuscript can be accessed under supplemental material online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2023.2353757

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hans Lundin

Hans Lundin is a PhD student at the Higher Education Organization Studies (HEOS) group, KTH Royal Institute of Technology. He also works as Regional Advisor at the International Relations Office at the same university. He holds a Master’s degree in political science from Umeå University.

Notes

1 International students in this article refers to degree-seeking students, i.e. not exchange students. Due to EU legislation, national and EU/EES students have to be treated equally, and tuition fees is only applied to non-EU/EES students.

2 A limitation with this method is that some scholarships also cover living expenses, not only tuition fees. Data does not provide possibility to separate. Nevertheless, gives a hint on relation public spending/revenue

3 10 SEK ≈ 1 €

4 225 MM SEK/Total state allowances 2022.

5 500 MM SEK/Total state allowances 2010.

6 According to QS or THE ranking 2022, if occurrence on both, best rank presented

7 In comparison to revenue generated from state allowances

8 Estimates based on comparison of educational offer within STEM fields, with state allowances in STEM the same year. In the case of Karolinska, educational offer within Medicine and state allowances of Medicine.

References

- Agasisti, T., and G. Catalano. 2006. “Governance Models of University Systems – Towards Quasi-Markets? Tendencies and Perspectives: A European Comparison.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 28 (3): 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800600980056

- Altbach, P., and H. de Wit. 2023. “When HE Internationalisation Operates as an Industry.” University World News. 11 April 2023.

- Bertolin, J. C. G. 2011. “The Quasi-Markets in Higher Education: From the Improbable Perfectly Competitive Markets to the Unavoidable State Regulation.” Educação e Pesquisa 37 (2): 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-97022011000200002

- Bryntesson, A. 2018. Det svenska studieavgiftssystemets ekonomiska logik. En kritisk diskussion. Uppsala: Uppsala universitet.

- Cannings, J., M. Halterbeck, and G. Conlon. 2023. The Benefits and Costs of International Higher Education Students to the UK Economy. HEPI. United Kingdom. Accessed 05 February 2024, https://policycommons.net/artifacts/3839138/full-report-benefits-and-costs-of-international-students/4645030/.

- Cantwell, B. 2015. “Are International Students Cash Cows? Examining the Relationship Between New International Undergraduate Enrollments and Institutional Revenue at Public Colleges and Universities in the US.” Journal of international students 5 (4): 512–525. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v5i4.412

- Clark, B. R. 1983. The Higher Education System: Academic Organization in Cross-National Perspective. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- de Gayardon, A. 2017. “Free Higher Education: Mistaking Equality and Equity.” International Higher Education (91): 12–13. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2017.91.10127

- De Wit, H. 2024. “Competing for Students: Global North Gives Up Its Privilege.” University World News 13 January 2024. Accessed 10 April 2024 https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20240110113612397.

- Docquier, F., and J. Machado. 2016. “Global Competition for Attracting Talents and the World Economy.” The World Economy 39 (4): 530–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12267

- Gornitzka, Å, and P. Maassen. 2000. “Hybrid Steering Approaches with Respect to European Higher Education.” Higher Education Policy 13 (3): 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0952-8733(00)00012-X

- HEPI. 2023. UK Higher Education – Policy, Practice and Debate During HEPI’s First 20 Years, Higher Education Policy Institute. United Kingdom. Accessed 05 February 2024 https://policycommons.net/artifacts/4499457/uk-higher-education/5302119/.

- Howlett, M. 2014. “From the ‘Old’ To the ‘New’ Policy Design: Design Thinking Beyond Markets and Collaborative Governance.” Policy Sciences 47 (3): 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-014-9199-0

- Johnstone, D. B. 2004. “The Economics and Politics of Cost Sharing in Higher Education: Comparative Perspectives.” Economics of Education Review 23 (4): 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2003.09.004

- Johnstone, D. B., and P. N. Marcucci. 2010. Financing Higher Education Worldwide: Who Pays? Who Should Pay? Baltimore: JHU Press.

- Jongbloed, B. 2004. “Funding Higher Education: Options, Trade-Offs and Dilemmas.” Paper presented at the Fulbright Brainstorms 2004 – New Trends in Higher Education.

- Jungblut, J., and M. Vukasovic. 2013. “And Now for Something Completely Different? Re-examining Hybrid Steering Approaches in Higher Education.” Higher Education Policy 26 (4): 447–461. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2013.28

- Kauko, J., and A. Medvedeva. 2016. “Internationalisation as Marketisation? Tuition Fees for International Students in Finland.” Research in Comparative and International Education 11 (1): 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499916631061

- Knight, J. 2013. “The Changing Landscape of Higher Education Internationalisation – for Better or Worse?” Perspectives: Policy and practice in higher education 17 (3): 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2012.753957

- Lascoumes, P., and P. Le Galès. 2007. “Introduction: Understanding Public Policy Through its Instruments – from the Nature of Instruments to the Sociology of Public Policy Instrumentation.” Governance 20 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00342.x

- Liu, D., and M. C. Solheim. 2023. “Tuition Fees for International Students in Norway: A Policy-Debate.” Beijing International Review of Education 5 (3): 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1163/25902539-05030005

- Lomer, S. 2017. “Soft Power as a Policy Rationale for International Education in the UK: A Critical Analysis.” Higher Education 74 (4): 581–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0060-6

- Lundin, H., and L. Geschwind. 2023. “Exploring Tuition Fees as a Policy Instrument of Internationalisation in a Welfare State – the Case of Sweden.” European Journal of Higher Education13 (1): 1–19.

- Lunt, I. 2008. “Beyond Tuition Fees? The Legacy of Blair’s Government to Higher Education.” Oxford Review of Education 34 (6): 741–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980802519001

- Marcucci, P. N., and D. B. Johnstone. 2007. “Tuition Fee Policies in a Comparative Perspective: Theoretical and Political Rationales.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 29 (1): 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800600980015

- Marginson, S. 2011. “Higher Education and Public Good.” Higher Education Quarterly 65 (4): 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2011.00496.x

- Ministry of Education. 2022. Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriön julkaisuja 2022:3. Helsinki.

- Mintz, B. 2021. “Neoliberalism and the Crisis in Higher Education: The Cost of Ideology.” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 80 (1): 79–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12370

- Myklebust, J. P. 2023. “Unions Object to ‘Contradictory’ non-EU Student fee Hike.” University World News 7 September 2023. Accessed 10 April 2024: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20230907093703656.

- Naidoo, V., R. Roy, F. K. Rabbanee, and T. Wu. 2022. “Drivers of Tuition Fee Setting Practices for Higher Education Institutions Involved in International Student Recruitment.” Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2022.2076274

- Nilsson, P. A., and L. Westin. 2022. “Ten Years After. Reflections on the Introduction of Tuition Fees for Some International Students in Swedish Post-Secondary Education.” Education Inquiry, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2022.2137912

- Nordensvärd, J., and M. Ketola. 2019. “Rethinking the Consumer Metaphor Versus the Citizen Metaphor: Frame Merging and Higher Education Reform in Sweden.” Social Policy and Society 18 (4): 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746418000465

- Norton, A. 2020. “How Reliant is Australian University Research on International Student Profits?” https://andrewnorton.net.au/2020/05/21/how-reliant-is-australian-university-research-on-international-student-profits/.

- OECD. 2008. “Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society.” OECD Publishing 1 (2): 23–30.

- OFS (Office for Students). 2022. Accessed June 5, 2023. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/student-outcomes-data-dashboard/data-dashboard/.

- Oxford Economics. 2020. Multiplying Economic Value: The Impact of Swedish Universities, Report for SULF. London: Oxford Economics.

- Paradeise, C., E. Reale, and G. Goastellec. 2009. “A Comparative Approach to Higher Education Reforms in Western European Countries.” In University Governance. Higher Education Dynamics, edited by C. Paradeise, E. Reale, I. Bleiklie, and E. Ferlie, Vol. 25, 197–225. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Pressman, J. L., and A. Wildavsky. 1984. Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed in Oakland; Or, Why It’s Amazing That Federal Programs Work at All, This Being a Saga of the Economic Development Administration as Told by two Sympathetic Observers Who Seek to Build Morals on a Foundation. Berkeley: Univ of California Press.

- Prop 2009/10:65 (Governmental bill). 2009. Konkurrera med kvalitet – studieavgifter för utländska studenter. Stockholm: Utbildnings- och kulturdeparementet.

- Reale, E., and M. Seeber. 2013. “Instruments as Empirical Evidence for the Analysis of Higher Education Policies.” Higher Education 65 (1): 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9585-5

- Rensimer, L., and T. McCowan. 2023. Reconceptualising International Flows of Aid to and through Higher Education. Working paper no. 97. Centre for Global Higher Education Working Paper series.

- Rickmann, J. 2021. Market Smart, not Market Driven, Organizational Processing at Swedish Universities After the Introduction of Tuition Fees for International non-EU-Students. Milano: Università Cattolica Del Sacro Cuore.

- Salancik, G. R., and J. Pfeffer. 1978. “A Social Information Processing Approach to job Attitudes and Task Design.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 23 (2): 224–253. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392563

- Sanchez-Serra, D., and G. Marconi. 2018. “Increasing International Students’ Tuition Fees: The two Sides of the Coin.” International Higher Education 92: 13–14. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2018.92.10278

- Seeber, M., M. Cattaneo, J. Huisman, and S. Paleari. 2016. “Why Do Higher Education Institutions Internationalize? An Investigation of the Multilevel Determinants of Internationalization Rationales.” Higher Education 72 (5): 685–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9971-x

- Skr 2015/16:48. 2015. Regeringens exportstrategi (Skrivelse Skr 2015/16:48). Stockholm.

- Slaughter, S., and G. Rhoades. 2004. Academic Capitalism and the New Economy. Markets, State and Higher Education. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- SOU 2018:78 (Official Reports of the Swedish Government). 2018. Ökad attraktionskraft för kunskapsnationen Sverige. Stockholm.

- Swedish Institute. 2022. Den ekonomiska effekten av internationella studenter Diarienummer: 10561/2021. Stockholm.

- Tange, H., and K. Jæger. 2021. “From Bologna to Welfare Nationalism: International Higher Education in Denmark, 2000–2020.” Language and Intercultural Communication 21 (2): 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2020.1865392

- Teixeira, P., B. B. Jongbloed, D. D. Dill, and A. Amaral. 2006. Markets in Higher Education: Rhetoric or Reality? (Vol. 6). Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Tilak, J. B. 2008. “Higher Education: A Public Good or a Commodity for Trade?” Prospects 38 (4): 449–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-009-9093-2

- UKÄ (Universitetskanslerämbetet). 2017. Kartläggning av studieavgifter: Redovisning av ett regeringsuppdrag (Rapport 2017:2). Stockholm.

- UKÄ (Universitetskanslerämbetet). 2023. Data base. Accessed June 05, 2023. https://www.uka.se/integrationer/hogskolan-i-siffror/statistik?statq=https://statistik-api.uka.se/api/totals/14.

- Universitetsläraren. 2017. “Utländska studenter betalar mer än vad en svensk student kostar.” Accessed June 5, 2023. https://universitetslararen.se/2017/06/21/utlandska-studenter-betalar-mer-an-vad-en-svensk-student-kostar/?hilite=Utl%C3%A4ndska+studenter.

- Westin, L., and P. A. Nilsson. 2023. “The Swedish Debate on Tuition Fees for International Students in Higher Education.” Journal of interdisciplinary studies in education 12 (2): 281–303.

- Yin, R. K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. Sixth edition. Los Angeles: SAGE.