ABSTRACT

Documentation is an integral part of social work. It is a tool in client work, and it also has an accountability perspective. Documentation helps the practitioners to evaluate their own work and makes it possible to assess the impact of work and develop practices. The use of client documents for research purposes has been identified as an option, but it is still quite rare. Moreover, little attention has been paid to social work with adults in this context. The development of electronic information systems (EIS), including structured forms, presents new research opportunities. Through documentation, it is possible to make tacit information visible and obtain evidence, for example, about the effects of adult social work. The aim of this review is to examine the use of adult social work client documents in research: what kinds of documents are used as data, what are the aims and methods of the studies, and especially what opportunities and challenges are associated with the client documents as research data? The review finds that the methods and research topics are diverse. It indicates that documentation has a low status in adult social work, and recording practices are inadequate; this has implications for the client’s position and involvement, the development and monitoring of social work, and the usability of such documents for research purposes. These findings are a matter of serious concern, and they are linked to the demanding working conditions and the recording cultures that prevail in organizations, as well as problems with information systems.

Introduction

Documentation in social work has various functions. It often has a negative image, and it is perceived as a secondary and time-consuming task (Shaw et al. Citation2009; Gillingham Citation2011; McDonald et al. Citation2015; Lauri Citation2016; Lillis Citation2017). However, documentation and social work are closely intertwined. Documents are also recognized as valuable data and tools for knowledge formation (Kääriäinen Citation2003; Alexanderson et al. Citation2009), and their importance has only increased with the development of EIS. Still, there are challenges. From the practitioner’s point of view, the EIS does not always serve practical work in the best possible way (Ylönen Citation2022; Gillingham Citation2021).

This scoping review centres on the use of adult social work documentation for research purposes as there appears to be limited research combining these topics. It is easier to find research on childcare and families that uses client documents as data (e.g. Baginsky, Manthorpe, and Moriarty Citation2020; Laird et al. Citation2017; Hoyle et al. Citation2019); research concerning social work with the elderly is also available (e.g. Chester et al. Citation2021; Storey and Perka Citation2018). One reason for this may be the diversity of social work with adults (Thompson Citation2002, 288). Social work with adults is a large and indeterminate field. In this study, adult social work is approached from a Finnish context. This partly delimits the data, and serves as a background for my further document study of the effects of adult social work in Finland. However, this does not exclude an international connection and exploitation of the findings, as the themes of adult social work and documentation are similar, and the review includes international research.

The aim of this scoping review is to generate information about the opportunities and challenges of documentation related to the research use of adult social work client documents. In addition, it maps the data and methods used as well as the topics studied. The review also contributes suggestions for improvement from the perspective of documentation. In what follows, I describe the key concepts and the scoping review method, and its application in this article according to the five stages of Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) framework. The findings section presents an overview of the data and its features, organized around the research questions. This is followed by a discussion and conclusion.

Key concepts

Documentation in social work

According to Askeland and Payne (Citation1999), terms related to documentation internationally are ‘case records’, ‘notes’ or ‘files’, and ‘case recording’. For clarity, in this article these terms are subsumed under the terms ‘documents’ and ‘documentation’. Documentation can include written texts, video and audio recordings, photographs and drawings (Denscombe Citation2010). The functions and practices of documentation have altered over the years. It is still used for practice development, theory-building, research and teaching, as it was in the early 20th century (Reamer Citation2005). It also retains planning and monitoring functions (Prior Citation2003; Laaksonen et al. Citation2011; Lillis Citation2017). Reamer (Citation2005) notes that risk management and the protection of clients, practitioners and employers is part of documentation. Documentation is regulated by law. It should be accurate, sufficient and timely. It should include only relevant information, and clients’ privacy should be protected (2015/254).

Documentation is often considered time-consuming, boring, and ‘just’ an administrative task. It is believed to limit the time available for face-to-face work with clients, which is perceived as ‘real social work’ (Shaw et al. Citation2009; Gillingham Citation2011; McDonald et al. Citation2015; Lauri Citation2016; Lillis Citation2017). Standardized templates are considered inflexible, focusing on technical issues and decisions instead of on the content of conversations (Jacobsson and Martinell Barfoed Citation2019). The use of measurement in social work is criticized because it is associated with managerialism and the business world; it is considered to focus on outcomes rather than values (Vojak Citation2009; Bradt et al. Citation2011; Fook Citation2016; Phillips Citation2019). The complexity of information systems (IS) is also perceived as a challenge in the field (Shaw et al. Citation2009). According to Björngren Cuadra (Citation2019), problems with IS stem from a lack of knowledge about frontline social work among IS designers, as well as the diversity of needs depending on the point of view taken.

Documentation is also recognized as a window onto the previous sociopolitical situations (Prior Citation2007; Vierula Citation2017). Systematicity, planning, goals and holistic assessments reduce ‘drift’, which is often seen as a problem (Thompson Citation2002). Documentation makes it possible to implement evidence- and knowledge-based ways of working (Alexanderson Citation2006). It provides a tool with which to assess goals and agree next steps with the client. Proper documentation is also important for accountability to clients (Lillis Citation2017). Documents make the process visible to all parties, including policymakers (Laaksonen et al. Citation2011). It is known that turnover in social work is high (Yliruka et al. Citation2020). Updated and accurate documentation helps with continuity in changing situations (Reamer Citation2005; Lillis Citation2017). Documentation may also develop one’s professional identity and enables reflection (McDonald et al. Citation2015). Integrating and securing access to services requires proper documentation. Multiprofessional use of the plans and assessments contained in EIS is central, especially when clients have multiple illnesses and problems (Hujala and Lammintakanen Citation2018). Cooperation and the pooling of resources also has economic implications (e.g. Murray, Rodriguez, and Lewis Citation2020; Cheng and Catallo Citation2020).

The importance of client documents as a source from which to measure outcomes in evaluation research has grown over the years (e.g. Carrilio Citation2005, Citation2008). This is connected to development requirements in data management and recording practices, and increases the demands for structured recording. These needs have also been taken into account in Finland. There is, for example, an effectiveness evaluation tool called ‘KEY’ which is integrated into the client database system. It is used in services for people of working age. This tool is based on realistic evaluation, and it takes advantage of single case design and ICT (Kivipelto et al. Citation2015). Blom and Morén (Citation2007, Citation2015) are also interested in the effects of social work and the mechanisms behind it, as well as the use of client documents in research. They have developed CAIMeR theory; a theory based on critical realism (Blom and Morén Citation2015). This theory takes mechanisms and contexts into account, and asks how and why certain outcomes occur in a particular context. This type of research, and the structured recording that enables it, is one way to highlight the effectiveness of social work that is perceived as difficult to achieve.

Until recently, the secondary use of client documents as a primary source in qualitative research was not particularly widespread. In the late 1990s, documentary research was alien to social work research (McCulloch Citation2004). Nevertheless, documentary research has a long history in sociology. Documentary investigation was the main research tool of classical sociologists such as Marx and Weber; it was later also used by social scientists such as Foucault and Bourdieu (Coffey Citation2014; Scott Citation1990). Documents are often perceived as supplementary data, giving background information and verifying other data sources (Prior Citation2007; Bowen Citation2009). The reliability of the data is considered a challenge: client documents have been described as selective, partial, and based on practitioners’ interpretations of events (Floersch Citation2000). It must also be borne in mind that client documents are written for purposes other than research (Denscombe Citation2010).

Social work with adults

Any definition of adult social work faces dilemmas in relation to both the content and the terminology. Internet searches reveal that various combinations of terms are used. ‘Adult social care’ is mainly used on British webpages. The term ‘safeguarding’ also emerges in the context of social work with adults in the UK. In Finland, Finnish terms are used meaning ‘social work with adults’, ‘social services for adults’ and ‘services for people of working age’, although a direct Finnish translation of the English term ‘adult social work’ is commonly used. In the literature, the term ‘social work with adults’ is often used (e.g. Adams, Dominelli, and Payne Citation2002).

Thompson (Citation2002, 288) notes the diversity of social work with adults but finds some common themes, such as the ‘importance of seeking to empower people, to support them constructively in their efforts to retain as much control as possible over their lives, to remain as independent and autonomous as possible, and to remove or avoid barriers to enjoying a quality of life free from distress, disadvantage and oppression’. It is often stated that the nature of adult social work is unclear, and that it is less valued than child protection, which is often prioritized and seen as more complex. (ibid., Thompson Citation2002). Nonetheless, there is a strong interconnection between adult social work and child protection (e.g. Lymbery and Postle Citation2010).

Activation has become a key policy focus in the 21st century, with impacts on adult social work practice and clients (van Berkel et al. Citation2012; Hansen and Natland Citation2017). There is concern about clients who no longer have access to the labour market, raising the question of whether work with this group will become a secondary task in adult social work (Liukko Citation2006). Personalization – person-centred planning for individual needs and support, and individual payments in the form of personal budgets – has also become a central issue for those who are eligible for services (e.g. Lymbery Citation2012; Malbon, Carey, and Meltzer Citation2019).

In Finland, services are grouped according to a life cycle model: services for families with children, services for adults 18–64 years, and services for older people over 65 years (Karjalainen, Metteri, and Strömberg-Jakka Citation2019). This distinguishes Finland from many other countries, because older people are not primarily clients of adult social work (services for adults). Adult social work in Finland is located in municipal offices (Juhila Citation2008). It has strong link to social assistance (Karjalainen Citation2017), also called ‘income support’. Common issues that call for adult social work intervention are unemployment and livelihood problems, health issues, substance use, housing problems, criminal behaviour and family crises; often, these issues overlap (Juhila Citation2008; Karjalainen Citation2017). It is worth mentioning that older people or care leavers may also be clients of adult social work if the financial support is placed in connection with the adult social work services.

Methods

This article uses the scoping review method proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005). Scoping reviews can be undertaken to examine the extent, range and nature of a particular research activity (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005). A scoping review does not necessarily describe previous research findings in detail. It rarely answers specific questions or assesses the quality of the studies reviewed. However, scoping is applicable when the field of interest is complex and difficult to grasp, and when reviews on the topic are not yet available. Scoping reviews are appropriate to inform practice, programmes and policy, and to provide directions for future research (Colquhoun et al. Citation2014). A scoping review is suitable for the topic of research on adult social work due to the topic’s complexity. According to previous research, there is a need for documentation-related improvements at many levels, and a scoping review may provide insight into this too.

The scoping study process is not linear, and it requires a reflexive approach, repeating each step to ensure that the literature is covered comprehensively. During the preparation of this article, I followed the five stages of Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) framework: 1) identifying the research question; 2) identifying relevant studies; 3) making the study selection; 4) charting the data; 5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results.

By reading previous studies I first formulated and identified my research questions and definitions of my key concepts (‘document’, ‘documentation’ and ‘adult social work’). I thoroughly examined these questions concepts from the perspective of current practices and changes in social work, such as the evaluation of effectiveness, EIS, and functions and development of documents and documentation. As a result, I formulated the research questions as follows: what kinds of documents are used as data in research? What are the research aims and methods? What are the opportunities and challenges associated with documents, documentation and their use as research data?

I then started to identify and select relevant studies by conducting preliminary searches. The search strategy was piloted in autumn 2020, and the final searches were conducted systematically in electronic databases (Web of Science, Social Services Abstracts, Scopus and Sociological Abstracts) over a three-month period from January to March 2021. I tested different combinations of ‘adult’, ‘adult social work’, ‘social work/care/service’, ‘documentation’ and ‘case file(s)/note(s)/record(s)’. The use of ‘adult’ constrained the results excessively, and searches with ‘documentation’ yielded ineligible hits. The terms found to be most suitable were ‘case file(s)/note(s)/record(s)’.

Specific keywords used in the search were ‘social work OR social service OR social care AND recording OR records OR case file OR case note’, adapted to the search tools for each database and using the ‘anywhere except full text’ function. The criteria for inclusion were as follows: the topic included social work with adults (as understood in Finland and defined above); social services client documentation was used as data; the research was published in English in a peer-reviewed journal between January 2010 and March 2021. The period 2010–2021 was chosen because EIS have become more common during that time, and because of this the data has been easier to obtain for research purposes. It should be noted that in some of the selected studies, the age criteria (under 65 years or over 18 years) was only partially met. In these cases, there was flexibility in the age criteria if the topic suited the Finnish context, which was also one of the criteria. The criteria for exclusion were as follows: the definition of adult social work did not correspond to the context outlined for this article; the research discussed elderly people or families from child protection or parenting perspectives; the journal was in a field of health care; medical records were used as data; the language of publication was not English.

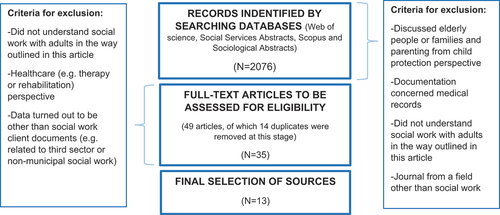

A total of 2076 records were identified through database searches. The decision to include or exclude was made by reading the titles and abstracts. If it was unclear whether my criteria (usually concerning the data or target group) were met, I read the paper’s methodology section. Despite the large number of hits, only 49 met my inclusion criteria at the first round. At this stage, 14 duplicates were removed, leaving 35 articles. I then conducted a full-text review and closer examination of the data to verify the eligibility of the 35 articles. I excluded several articles at this point because they turned out to be related to healthcare or to have been produced by third-sector actors; adult social work did appear in these articles, but it was not understood in the way outlined above, or else the documents used had not been produced in a social work context. Ultimately, after careful reading, 13 articles were included ().

The next step, data-charting, extracted the information (). Data-charting identifies general information about each study as well as specific information, such as the type of intervention, the outcome measures employed, and the study design (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005). The final stage was collating and summarizing. I organized the data and marked up all the references in the articles to documents or documentation and noted their content. I then allocated all of the references to opportunities and challenges. I also marked up the methods and data used, and the aim of the research. These themes and their contents are summarized in my findings section below.

Table 1. Data-charting.

Findings

Data used in the studies

Terms describing the documents used as data appear in the data section in . The commonest sources of data were individual-level client documents extracted from electronic IS maintained by social welfare, or comparable documents collected within the framework of municipally funded projects (Skogens Citation2011; Hamilton et al. Citation2015; Trainor Citation2015; Papadakaki et al. Citation2013; Fernqvist Citation2018; Chotvijit, Thiarai, and Jarvis Citation2019; Choi and Chan Citation2020; Fontaine et al. Citation2020; Matscheck and Piuva Citation2020; Petersen and Parsell Citation2020). In one study only (Papadakaki et al. Citation2013), the documentation was done by hand on paper. In some cases, the data was supplemented by interviews (Papadakaki et al. Citation2013; Fyson Citation2015; Trainor Citation2015; Ismail et al. Citation2017). The data also included documents containing statistical information that had been collected from client documents for monitoring purposes (Fyson Citation2015; Scannapieco, Smith, and Blakeney-Strong Citation2016; Ismail et al. Citation2017). The sample sizes varied from just over ten to more than 200,000 individuals. As might be expected, sample sizes were smaller in qualitative studies (e.g. Skogens Citation2011; Fernqvist Citation2018; Choi and Chan Citation2020; Matscheck and Piuva Citation2020) than in quantitative studies (e.g. Chotvijit, Thiarai, and Jarvis Citation2019). The time frame for which the data was collected ranged between three months and seven years.

Aims and methods of the studies

A common theme of the studies was to produce knowledge and information for practice. The studies roughly fell into two groups. The first group shared an interpretive approach. Their aim was to identify explanations, causes or contexts for various factors and their influence on a particular phenomenon (Skogens Citation2011; Hamilton et al. Citation2015; Scannapieco, Smith, and Blakeney-Strong Citation2016; Ismail et al. Citation2017; Choi and Chan Citation2020; Petersen and Parsell Citation2020). The second group was oriented towards practice research and development, offering suggestions for the improvement of current practice (Fyson Citation2015; Papadakaki et al. Citation2013; Trainor Citation2015; Chotvijit, Thiarai, and Jarvis Citation2019; Matscheck and Piuva Citation2020). Two of the 13 studies selected did not fall in either of these two groups. One of these studies explored a new method and tested it on documentary data (Fontaine et al. Citation2020). The other was a discursive study examining the construction of clients’ income support case records; the underlying idea was that documents are tools for the exercise of control and power (Fernqvist Citation2018).

Thus, across all 13 studies, both qualitative (Fernqvist Citation2018; Choi and Chan Citation2020; Fontaine et al. Citation2020; CitationMatscheck and Piuva; Petersen and Parsell Citation2020) and quantitative (Skogens Citation2011; Hamilton et al. Citation2015; Scannapieco, Smith, and Blakeney-Strong Citation2016; Ismail et al. Citation2017; Chotvijit, Thiarai, and Jarvis Citation2019) methods were used. There were also mixed methods studies (Fyson Citation2015; Trainor Citation2015; Papadakaki et al. Citation2013). These studies used documents as supplementary quantitative data regarding background information and sociodemographic details. In these studies, the primary qualitative data was collected by interviewing. As methods of analysis, the qualitative studies used discourse analysis (Fernqvist Citation2018), thematic analysis (Trainor Citation2015; Choi and Chan Citation2020) and qualitative analysis (Petersen and Parsell Citation2020). The quantitative studies used a variety of statistical methods, examining correlations (Hamilton et al. Citation2015), causalities (Scannapieco, Smith, and Blakeney-Strong Citation2016), personal characteristics and frequency of phenomena (Trainor Citation2015; Papadakaki et al. 2016), the continuity of stages in the client process (Chotvijit, Thiarai, and Jarvis Citation2019), and categories (Skogens Citation2011). In-depth analysis (Ismail et al. Citation2017) and analysis using conceptual models was also conducted (Matscheck and Piuva Citation2020).

The studies implemented non-random data selection (Scannapieco, Smith, and Blakeney-Strong Citation2016) or – as in most of the studies – selected data based on the occurrence in the documents of certain phenomena, such as unemployment and substance abuse (Skogens Citation2011), suicide risk (Hamilton et al. Citation2015), homelessness (Petersen and Parsell Citation2020) or violence (Choi and Chan Citation2020). In some studies, either the social workers or the researchers themselves used data-mining and data collection tools to gather demographic details and other relevant information (Choi and Chan Citation2020; Fontaine et al. Citation2020; Petersen and Parsell Citation2020).

Opportunities and challenges of documentation and research use

My analysis of the studies mainly identified challenges regarding documentation in general, which also related to the challenges of research use. Opportunities were not identified to the same extent. The documentation and assessment processes appeared to be complex (Chotvijit, Thiarai, and Jarvis Citation2019), and several problems were linked to them. There were indications that documentation was experienced as an obligation. For example, a new documentation policy seemed to be implemented mainly because it had been ordered from higher up the hierarchy (Matscheck and Piuva Citation2020). The documented texts were often unclear; for example, it was difficult to find the context or participants in the documents (Fernqvist Citation2018; Matscheck and Piuva Citation2020). The reasons identified for inadequate documentation were the provision of unsuitable tools such as inappropriate templates (Fyson Citation2015; Scannapieco, Smith, and Blakeney-Strong Citation2016), a lack of time in the face of increasing client numbers, and frustration with repetition in the documentation (Fyson Citation2015). This manifested in the use of journals instead of ready-made forms, and in incomplete documentation processes that made it difficult to see how the process with a client had progressed (Chotvijit, Thiarai, and Jarvis Citation2019; Matscheck and Piuva Citation2020). Incomplete, unsystematic documentation, variability in the use of EIS, constant changes in terminology, and differences in practice were considered to have affected the quality and reliability of research data (Skogens Citation2011; Fyson Citation2015; Papadakaki et al. Citation2013; Scannapieco, Smith, and Blakeney-Strong Citation2016; Ismail et al. Citation2017; Chotvijit, Thiarai, and Jarvis Citation2019).

The consequences of poor documentation were also discussed. Among other things, cooperation and information exchange among actors was found to be difficult, which in turn might threaten clients’ access to services. Challenges were also identified in the design of cost-effective services (Chotvijit, Thiarai, and Jarvis Citation2019), and long-term goals and monitoring became difficult due to poor documentation (Matscheck and Piuva Citation2020). Deficiencies in documentation had impacts on resourcing. The growing workload could not be verified – if there was no recorded data, there could be no additional resources (Fyson Citation2015). Other challenges were small sample sizes and the production of data by a single individual which reduced generalizability (Trainor Citation2015; Ismail et al. Citation2017; Chotvijit, Thiarai, and Jarvis Citation2019; Choi and Chan Citation2020; Matscheck and Piuva Citation2020). Discretion, interpretation, and the situationality of documents were also mentioned as limiting factors (Skogens Citation2011; Fernqvist Citation2018; Choi and Chan Citation2020; Fontaine et al. Citation2020; Petersen and Parsell Citation2020). The exploration of client documents was also time-consuming (Matscheck and Piuva Citation2020).

One opportunity-related factor was that secondary use of materials could save the researcher time and money (Fontaine et al. Citation2020). Client documents also enabled the exploration of sensitive topics while maintaining privacy and offering objective descriptions (Choi and Chan Citation2020), as well as granting access ‘below the surface’ (Fontaine et al. Citation2020). Negative features, such as the appearance of shortcomings in the documentation, were also identified as opportunities insofar as they allowed the problem in question to be addressed (Fyson Citation2015; Papadakaki et al. Citation2013). Here it was considered important to reflect on the relevance of documentation and the development of document templates. Researchers noted that improvements were needed to obtain accurate information. New templates should be piloted before final deployment, ‘forced choices’ such as key demographic data should be included, and the harmonization of terminology was necessary (Fyson Citation2015; Chotvijit, Thiarai, and Jarvis Citation2019). Changes in practices and habits were found to require front-level authorization (Matscheck and Piuva Citation2020).

Discussion and conclusion

The findings reveal that adult social work documents are used as research data in various ways: as background material, to explain particular phenomena and causalities, or for development purposes. Qualitative and quantitative methods are used equally; mixed methods are also deployed.

However, my findings suggest that the varying quality of the documentation and other related problems are obstacles to the exploitation of documents in practice, research and development. Although the measurement of outcomes (Carrilio Citation2005, Citation2008) and its connection to documentation has long been discussed, there are still major problems in the production of information for these purposes. It seems that EIS are unable to fulfil their own informational mission with regard to social work as it has been noted also in previous studies (Shaw et al. Citation2009; Björngren Cuadra Citation2019). Not only in order to measure outcomes, but also to highlight challenges and correct problems in documentation, the use of documents as research data should be both continued and expanded. Studies that use documents as data are often oriented towards interventions and results. The potential to deepen the use of documents as data could be further exploited to identify how and why certain outcomes occur in particular contexts, as Blom and Morén (Citation2015) suggest.

My findings show that working conditions affect the quality of documentation. Poor documentation and its practices were addressed in more than half the studies I analysed. If adult social work were viewed solely in the light of client documents, it would appear rather unsystematic and unplanned. This is obviously not the whole truth. As is known, workloads are huge, and there is limited time for documentation (Shaw et al. Citation2009; Gillingham Citation2011; McDonald et al. Citation2015; Lauri Citation2016; Lillis Citation2017). Lack of time and unsuitable tools may lead to incorrect recording, as may lack of knowledge and even deliberate resistance.

Conducting social work in the field under challenging circumstances has adverse consequences. It is often said that what is not recorded has not happened. In that regard, imbalances in resources or work allocations are linked to documentation, as my findings demonstrate (Fyson Citation2015). Missing or incomplete documents do not give the whole picture of the work done, and this in turn provides managers with insufficient evidence of the need for additional resources or amended working arrangements. The result is a vicious circle. The poor state of documentation may reflect a larger picture of the challenges in social work practice. Gradually, poor working conditions come to be perceived as necessary evils about which nothing can be done, and this is again reflected in the shortcomings of documentation. Indifferent attitudes emerge, and sometimes changing one’s job appears to be the only way out. As is known, the turnover of employees in the field of social work is high (e.g. Yliruka et al. Citation2020). Because of the constant churn, views and visions of the work may narrow; for example, the importance of documentation, and the employee’s own role in it, may not be recognized in terms of benefits.

The benefits of documentation have been presented in previous studies from the perspectives of clients, employees and the wider context (Thompson Citation2002; Reamer Citation2005; Alexanderson Citation2006; Carrilio Citation2005, Citation2008; McDonald et al. Citation2015; Lillis Citation2017). Building a common understanding of these benefits would help to get to grips with the many levels of documentation. This would require shared willingness and discussion to improve documentation practices. Commitment and involvement at the management level are a crucial part of this. In addition, grassroots involvement in planning to make changes to recording practices and EIS should be taken into account, and care should be taken to implement each change properly before making the next. Consistency of documentation would enable the automatic extraction of statistical and register information at the national level, which is important to defend and develop social work in a way that recognizes clients’ needs and makes social work visible. This could be achieved by (among other things) improving working conditions, and by assessing resources and working methods in a way that makes systematic documentation and client participation in documentation possible. This in turn would strengthen the legal framework from a client perspective, offer a structured process, and provide better opportunities for the secondary use of documents and the construction of more reliable data. Investment in documentation might open the door – or the black box, as Blom and Morén (Citation2015) put it – to more in-depth research that uses documents as data, answering questions about how and why changes have taken place, and discovering not only the results but also the context of specific interventions.

Limitations

The complexity of the terminology meant that searches based on it left room for interpretation. In particular, the term ‘social work with adults’ was difficult to define and grasp in an international context. The inclusion criterion in the study was to limit the concept of social work with adults to the Finnish context. As a result, only a small percentage of the search results met the criteria. If the study had been conducted in the context of another country, the results would probably have been different. It should also be noted that the review was conducted by a single individual. This limited the scope and selection of the articles. While this limitation was accepted for practical reasons, it is worth pointing out that potentially relevant papers may have been missed, and a different researcher might have made different choices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, R., L. Dominelli, M. Payne 2002. Social Work: Themes, Issues and Critical Debates. 2nd. R. Adams, L. Dominelli & M. Payne Basingstoke: Palgrave in association with The Open University.

- Alexanderson, K. 2006. Vilja, Kunna, Förstå: Om Implementering Av Systematisk Dokumentation För Verksamhetsutveckling I Socialtjänsten [Willingness, Comprehension, Capability: About Implementation of Systematic Documentation for Developing Social Work in the Public Social Work Services]. Örebro: University Library.

- Alexanderson, K., E. Beijer, S. Bengtsson, U. Hyvönen, P.-Å. Karlsson, and M. Nyman. 2009. “Producing and Consuming Knowledge in Social Work Practice: Research and Development Activities in a Swedish Context.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 5 (2): 127–139. doi:10.1332/174426409X437883.

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Askeland, G. A., and M. Payne. 1999. “Authors and Audiences: Towards a Sociology of Case Recording.” European Journal of Social Work 2 (1): 55–65. doi:10.1080/13691459908413805.

- Baginsky, M., J. Manthorpe, and J. Moriarty. 2020. “The Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and Their Families and Signs of Safety: Competing or Complementary Frameworks?” British Journal of Social Work. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcaa058.

- Björngren Cuadra, C. (2019 14 March 2019). “Technology-dependent Documentation and Social Redundancy: A scenario-based Analysis of an IT Failure in the Social Services.” Paper presented at Nordic Welfare Research Conference: Towards Resilient Nordic Welfare States, Helsinki, Finland

- Blom, B., and S. Morén. 2007. Insatser Och Resultat I Socialt Arbete [Interventions and Results in Social Work]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Blom, B., and S. Morén. 2015. Teori för socialt arbete. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Bowen, G. A. 2009. “Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method.” Qualitative Research Journal 9 (2): 27–40. doi:10.3316/QRJ0902027.

- Bradt, L., R. Roose, M. Bie, and M. De Schryver. 2011. “Data Recording and Social Work: From the Relational to the Social.” British Journal of Social Work 41 (7): 1372–1382. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcr131.

- Carrilio, T. 2005. “Management Information Systems: Why are They Underutilized in the Social Services?” Administration in Social Work 29 (2): 43–61. doi:10.1300/J147v29n02_04.

- Carrilio, T. E. 2008. “Accountability, Evidence, and the Use of Information Systems in Social Service Programs.” Journal of Social Work 8 (2): 135–148. doi:10.1177/1468017307088495.

- Cheng, S. M., and C. Catallo. 2020. “Conceptual Framework: Factors Enabling Collaborative Healthcare and Social Services Integration.” Journal of Integrated Care 28 (3): 215–229. doi:10.1108/JICA-11-2019-0048.

- Chester, H., J. Hughes, I. Bowns, M. Abendstern, S. Davies, and D. Challis. 2021. “Electronic Information Sharing between Nursing and Adult Social Care Practitioners in Separate Locations: A mixed-methods Case Study.” Journal of Long-Term Care 2021: 1–11. doi:10.31389/jltc.16.

- Choi, A. W. M., and P. Y. Chan. 2020. “Women’s Use of Force: Hostility Intertwines in Chinese Family Context.” Qualitative Social Work: QSW: Research and Practice 19 (2): 192–212. doi:10.1177/1473325018805529.

- Chotvijit, S., M. Thiarai, and S. A. Jarvis. 2019. “A Study of Data Continuity in Adult Social Care Services.” The British Journal of Social Work 49 (3): 762–786. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcy083.

- Coffey, A. 2014. “Analysing Documents.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, edited by U. Flick, 367–379. Los Angeles: SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781446282243.n25.

- Colquhoun, H., D. Levac, K. O’Brien, S. Straus, A. Tricco, L. Perrier, M. Kastner, and D. Moher. 2014. “Scoping Reviews: Time for Clarity in Definition, Methods, and Reporting.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013.

- Denscombe, M. 2010. The Good Research Guide: For small-scale Social Research Projects. 4th ed. Buckingham: McGraw-Hill/Open University Press.

- Fernqvist, S. 2018. “‘One Does One’s Best’: Performing Deservingness in Income Support Case Records.” Critical and Radical Social Work 6 (3): 329–343. doi:10.1332/204986018X15321001889969.

- Floersch, J. 2000. “Reading the Case Record: The Oral and Written Narratives of Social Workers.” Social Service Review 74 (2): 169–192. doi:10.1086/514475.

- Fontaine, C. M., A. C. Baker, T. H. Zaghloul, and M. Carlson. 2020. “Clinical Data Mining with the Listening Guide: An Approach to Narrative Big Qual.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 160940692095174. doi:10.1177/1609406920951746.

- Fook, J. 2016. Social Work: A Critical Approach to Practice. 3rd ed. London: SAGE.

- Fyson, R. 2015. “Building an Evidence Base for Adult Safeguarding? Problems with the Reliability and Validity of Adult Safeguarding Databases.” The British Journal of Social Work 45 (3): 932–948. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct163.

- Gillingham, P. 2011. “Computer-based Information Systems and Human Service Organisations: Emerging Problems and Future Possibilities.” Australian Social Work 64 (3): 299–312. doi:10.1080/0312407X.2010.524705.

- Gillingham, P. 2021. “Practitioner Perspectives on the Implementation of an Electronic Information System to Enforce Practice Standards in England.” European Journal of Social Work 24 (5): 761–771. doi:10.1080/13691457.2020.1870213.

- Hamilton, D. J., B. J. Taylor, C. Killick, and D. Bickerstaff. 2015. “Suicidal Ideation and Behaviour among Young People Leaving Care: Case-file Survey.” Child Care in Practice: Northern Ireland Journal of multi-disciplinary Child Care Practice 21 (2): 160–176. doi:10.1080/13575279.2014.994475.

- Hansen, H. C., and S. Natland. 2017. “The Working Relationship between Social Worker and Service User in an Activation Policy Context.” Nordic Social Work Research 7 (2): 101–114. doi:10.1080/2156857X.2016.1221850.

- Hoyle, V., E. Shepherd, A. Flinn, and E. Lomas. 2019. “Child social-care Recording and the Information Rights of care-experienced People: A Recordkeeping Perspective.” British Journal of Social Work 49 (7): 1856–1874. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcy115.

- Hujala, A., and J. Lammintakanen. 2018. Paljon sote-palveluja tarvitsevat ihmiset keskiöön [People in need of multiple social and health services at the centre]. Helsinki: KAKS-Kunnallisalan kehittämissäätiö 2018.

- Ismail, M., S. Hussein, M. Stevens, J. Woolham, J. Manthorpe, F. Aspinal, K. Samsi, and K. SAMSI. 2017. “Do Personal Budgets Increase the Risk of Abuse? Evidence from English National Data.” Journal of Social Policy 46 (2): 291–311. doi:10.1017/S0047279416000623.

- Jacobsson, K., and E. Martinell Barfoed (2019). “Socialt Arbete Och Pappersgöra: Mellan Klient Och Digitala Document [Social Work and Paperwork: Between Client and Digital Documents]”. Gleerups Utbildning. http://lup.lub.lu.se/record/c3907961-c03b-4d58-8210-8923a1c71e16

- Juhila, K. 2008. “Aikuisten parissa tehtävän sosiaalityön areenat [Arenas for social work with adults.” In Sosiaalityö aikuisten parissa [Social work with adults], edited by A. Jokinen and K. Juhila, 14–47, Tampere: Vastapaino.

- Kääriäinen, A. 2003. Lastensuojelun Sosiaalityö Asiakirjoina: Dokumentoinnin Ja Tiedonmuodostuksen Dynamiikka [Social Work in Child Welfare as Documents: Dynamics of Documentation and Generation of Information]. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

- Karjalainen, P. 2017. “Aikuissosiaalityö [Social Work with Adults.” In Sosiaalityön käsikirja [Handbook of social work]. 4thed., edited by A. Kananoja, M. Lähteinen, P. Marjamäki, and K. Aho, 247–259. Helsinki: Tietosanoma.

- Karjalainen, P., A. Metteri, and M. Strömberg-Jakka. 2019. “Tiekartta 2030: Aikuisten parissa tehtävän sosiaalityön tulevaisuusselvitys [Road map 2030: Prospective study of social work with adults].” Helsinki: Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriö.

- Kivipelto, M., S. Blomgren, P. Saikkonen, and P. Karjalainen. 2015. “Web-based Tool for Social Work Effectiveness Evaluation.” Revista de Asistenta Sociala 3: 19.

- Laaksonen, M., A. Kääriäinen, M. Penttilä, M. Tapola-Haapala, H. Sahala, J. Kärki, and A. Jäppinen. 2011. Asiakastyön Dokumentointi Sosiaalihuollossa: Opastusta Asiakastiedon Käyttöön Ja Kirjaamiseen [Documentation of Client Work in Social Welfare: Guidance for Writing and Use of Information]. Helsinki: Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare.

- Laird, S. E., K. Morris, P. Archard, and R. Clawson. 2017. “Working with the Whole Family: What Case Files Tell Us about Social Work Practices.” Child & Family Social Work 22 (3): 1322–1329. doi:10.1111/cfs.12349.

- Lauri, M. (2016). Narratives of governing: Rationalization, responsibility and resistance in social work. PhD thesis, Umeå University.

- Lillis, T. 2017. “Imagined, Prescribed and Actual Text Trajectories: The ‘Problem’ with Case Notes in Contemporary Social Work.” Text & Talk 37. doi:10.1515/text-2017-0013.

- Liukko, E. 2006. Kuntouttavaa sosiaalityötä paikantamassa. Helsinki: SOCCA: Heikki Waris -instituutti.

- Lymbery, M. 2012. “Social Work and Personalisation.” British Journal of Social Work 42 (4): 783–792. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcs027.

- Lymbery, M., and K. Postle. 2010. “Social Work in the Context of Adult Social Care in England and the Resultant Implications for Social Work Education.” British Journal of Social Work 40 (8): 2502–2522. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcq045.

- Malbon, E., G. Carey, and A. Meltzer. 2019. “Personalisation Schemes in Social Care: Are They Growing Social and Health Inequalities?” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 805. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7168-4.

- Matscheck, D., and K. Piuva. 2020. “Integrated care for individuals with mental illness and substance abuse - the example of the coordinated individual plan in Sweden: Integrerad vård för personer med psykisk ohälsa eller missbruk - exemplet Samordnade Individuella Planer i Sverige.”European Journal of Social Work ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). 1–14. 10.1080/13691457.2020.1843409.

- McCulloch, G. 2004. Documentary Research in Education, History, and the Social Sciences. New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

- McDonald, D., J. Boddy, K. O’Callaghan, and P. Chester. 2015. “Ethical Professional Writing in Social Work and Human Services.” Ethics and Social Welfare 9 (4): 1–16. doi:10.1080/17496535.2015.1009481.

- Murray, G. F., H. P. Rodriguez, and V. A. Lewis. 2020. “Upstream with a Small Paddle: How ACOs are Working against the Current to Meet Patients’ Social Needs.” Health Affairs 39 (2): 199–206. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01266.

- Papadakaki, M., E. Kastrinaki, R. Drakaki, and J. Chliaoutakis. 2013. “Managing Intimate Partner Violence at the Social Services Department of a Greek University Hospital.” Journal of Social Work: JSW 13 (5): 533–549. doi:10.1177/1468017311435445.

- Petersen, M., and C. Parsell. 2020. “The Family Relationships of Older Australians at Risk of Homelessness.” The British Journal of Social Work 50 (5): 1440–1456. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcaa007.

- Phillips, C. R. 2019. “The Computer Social Worker: Regulatory Practices, Regulated Bodies and Science.” Qualitative Social Work 18 (3): 443–457. doi:10.1177/1473325017723700.

- Prior, L. 2003. Using Documents in Social Research. London: SAGE.

- Prior, L. 2007. Documents. Qualitative Research Practice (Concise pbk. ed.), edited by Seale C. London: SAGE.

- Reamer, F. 2005. “Documentation in Social Work: Evolving Ethical and risk-management Standards.” Social Work 50 (4): 325–334. doi:10.1093/sw/50.4.325.

- Scannapieco, M., M. Smith, and A. Blakeney-Strong. 2016. “Transition from Foster Care to Independent Living: Ecological Predictors Associated with Outcomes.” Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal 33 (4): 293–302. doi:10.1007/s10560-015-0426-0.

- Scott, J. 1990. A Matter of Record: Documentary Sources in Social Research. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Shaw, I., M. Bell, I. Sinclair, P. Sloper, W. Mitchell, P. Dyson, J. Clayden, and J. Rafferty. 2009. “An Exemplary Scheme? an Evaluation of the Integrated Children’s System.” British Journal of Social Work 39 (4): 613–626. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcp040.

- Skogens, L. 2011. “Labour Market Status, Requirements and Social support-single Male Clients with Problematic Alcohol Consumption.” European Journal of Social Work 14 (4): 513–523. doi:10.1080/13691457.2010.516497.

- Storey, J. E., and M. R. Perka. 2018. “Reaching Out for Help: Recommendations for Practice Based on an in-depth Analysis of an Elder Abuse Intervention Programme.” British Journal of Social Work 48 (4): 1052–1070. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcy039.

- Thompson, N. 2002. Social Work with Adults. 2nd ed. London: Palgrave.

- Trainor, P. 2015. “A Review of Factors Which Potentially Influence Decisions in Adult Safeguarding Investigations.” The Journal of Adult Protection 17 (1): 51–61. doi:10.1108/JAP-03-2014-0008.

- van Berkel, R., W. de Graaf, T. Sirovátka, and R. van Berkel. 2012. “Governance of the Activation Policies in Europe: Introduction.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 32 (5–6): 260–272. doi:10.1108/01443331211236943.

- Vierula, T. 2017. Lastensuojelun Asiakirjat Vanhempien Näkökulmasta [Child Protection Documents from a Parental Perspective]. Tampere: Tampere University Press.

- Vojak, C. 2009. “Choosing Language: Social Service Framing and Social Justice.” British Journal of Social Work 39 (5): 936–949. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcm144.

- Yliruka, L., P. Petrelius, S. Alho, A. Jaakola, H. Lunabba, S. Remes, S. Keränen, S. Teiro, and A. Terämä (2020). Osaaminen Lastensuojelun Sosiaalityössä. Esitys Asiantuntijuutta Tukevasta Urapolkumallista. [Competence in Child Welfare Social Work: A Presentation of Career Path Model Supporting Expertise].Työpaperi 36.Terveyden Ja Hyvinvoinnin Laitos. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-343-571-1

- Ylönen, K. 2022. “The Use of Electronic Information Systems in Social work.A Scoping Review of the Empirical Articles Published between 2000 and 2019.” European Journal ofSocial Work, Act on Social Welfare Client Documents. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2015/20150254.