ABSTRACT

Professionals’ understandings of substance use interventions and treatment goals impact treatment recommendations. We aimed to explore social work professionals’ (SWP) attitudes towards harm reduction philosophy and measures in three areas of Sweden with very differing development of their harm reduction: Malmö (most developed), Gothenburg (moderately developed), Gävleborg (least developed). We conducted a survey of SWP working with people who use drugs, utilizing the Harm Reduction Acceptability Scale (HRAS). An ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc correction was performed to assess for differences in mean HRAS score. There were 208 valid survey responses (Malmö: 79, Gothenburg: 82, Gävleborg: 47). The overall mean score indicated positive attitudes towards harm reduction. Means differed based on geographic location, with Malmö and Gothenburg scores indicating significantly more positive attitudes towards harm reduction than scores in Gävleborg. Opinions on implementation of new harm reduction measures such as heroin assisted treatment, supervised consumption sites, and decriminalization of drugs for personal use were more negative overall. These opinions followed the above trend, with regard to differences based on geography. Differences indicated that SWP who are more exposed to harm reduction have more positive attitudes. Increased knowledge of harm reduction among SWP could lead to improved access to interventions and reduced risks for people who use drugs.

Introduction

Service providers’ understanding of substance use, and attitudes towards people who use drugs (PWUD), have important impacts on what treatments and services are recommended (Brown Citation2022; Javadi et al. Citation2021). Harm reduction is one paradigm to address substance use which refers to a broad set of goals, strategies, and services which aim to reduce the social and physical harms of substance use, without necessarily requiring abstinence. However, its development has been slow in many settings, affecting the forms of service to which PWUD have access. Studies have demonstrated that some individuals who were educated or had professional experience within the abstinence-based sphere of substance use treatment had difficulty accepting the goals of harm reduction (and associated services) as legitimate (Housenbold Sieger Citation2005; Knudsen et al. Citation2005; Ogborne and Birchmore-Timney Citation1998). Javadi et al. (Citation2021) found that substance use professionals who reported that abstinence was the ultimate goal of treatment were less supportive of harm reduction measures such as needle and syringe exchange programmes (NSP), opioid substitution therapy (OST), and overdose prevention sites. Additionally, negative attitudes towards PWUD have been associated with lower levels of prescription of such critical medications as antiretroviral therapy for HIV, take-home naloxone for opioid overdose reversal, antiviral medications for hepatitis C infection, or opioid substitution therapies (Beletsky et al. Citation2007; Ding et al. Citation2005; Myles et al. Citation2011; Olsen and Sharfstein Citation2014). Often such attitudes are based on the perception that a harm reduction approach will increase risk-taking or encourage substance use (Green et al. Citation2013; Maccoun et al. Citation1993; Winograd et al. Citation2017).

On the basis that principles of harm reduction align directly with the foundations of social work – such as social justice, self-determination, and human rights – several authors have made calls for the social work profession to embrace the harm reduction movement for their substance-using clients (Brocato and Wagner Citation2003; McNeece Citation2003). Social work professionals (SWP), including those working in treatment, outreach, housing, screening, etc., are primary institutional contacts for PWUD and play an important role in their care. These professionals may have the most complete understanding of the needs of their clients, and what services they can or should access. They offer guidance, referrals, and information to clients, act as gatekeepers or facilitators to programmes and services, and symbolically validate the legitimacy of different interventions (Ekendahl Citation2011). SWP also have a role to play in the advocacy of policy solutions, and promoting the agency, empowerment, and self-determination of their clients. Their opinions on different service offerings or forms of care may be influenced by their education, institutional settings, policy context, personal factors, among others (Skogens Citation2005).

The importance of the role of SWP is particularly strong in Sweden. While social services shares the mandate with health care services over the care of PWUD, it is the social sector who play the dominant role in decision-making when it comes to choices of treatments for clients (Wallander and Blomqvist Citation2009). Social workers have a large margin of discretion because the Social Services Act is a ‘framework law’. Their attitude can therefore be decisive, as this means it is up to them to assess the suitability of different initiatives. Described by Ekendahl (Citation2011), ‘social services have influence over who receives which assistance and for what purpose, and social workers are expected to translate the treatment and help that PWUD get access to into practice, according to legislation, political guidelines and science’ (298) (author translation).

In Sweden, drug use is criminalized – with enforcement focus largely on the individual user – and drug policy is often described as moralizing, repressive, and strict (Eriksson and Edman Citation2017; Ledberg Citation2017; Tryggvesson Citation2012). The treatment system has historically largely been abstinence-oriented, based upon the goal of having a society free from drugs. As such, this is the policy paradigm which has dominated, and to some extent influences the thinking in social work education and the profession in this setting. Utilizing the Bordieuan concept of ‘doxa’, referring to the taken-for-granted, obvious, and often never-discussed assumptions that guide practice, Järvinen (Citation2006) argues that the way of organizing the care system also has an influence on what clients are offered, who the client is seen to be, and what the appropriate options for them are. Similarly, Heller et al. (Citation2004) describe the system-level influence of other philosophical approaches (such as abstinence-orientation) as an ‘invisible barrier’ to the uptake of harm reduction. As harm reduction has been relatively (to other neighbouring European countries) slowly developing in Sweden, such principles are not necessarily enshrined within the education and career development of SWP. This is demonstrated, for example, in that both OST and NSP were initially highly opposed by individuals in the social work profession in Sweden (Christensson and Ljungberg Citation1991; Gunne Citation1983; Johnson Citation2007; Tryggvesson Citation2012). These interventions were adopted early in Sweden, thanks largely to pioneers within the healthcare system, but the extent and forms of their development has been limited.

Sweden has been undergoing changes to its approach to drug policy, particularly in recent years. Increasingly, harm reduction principles have been encompassed within programming – such as increased numbers of and reduced criteria for NSP and OST (Andersson and Johnson Citation2020). Nevertheless, the rate and forms of this change are unevenly distributed across the country. The setting of this study is particularly interesting because Sweden has historically allowed a veto option over the implementation of certain services, including harm reduction service offerings. Until 2010, the social services and the municipalities had a veto over OST (because collaboration with the social services was a requirement for OST to be initiated). Similarly, until 2017, health services and municipalities had a veto over the establishment of NSP – meaning that many municipalities could, and did, vote against the development of NSP in their locality. This regional/municipal decision-making on offering of different services has led to significant variation of the development of harm reduction, and disparities in access to related services are in some cases quite large. This has implications for the care of clients in these areas, as it can, in principle, control the availability of life-saving interventions such as OST, NSP, overdose prevention, and housing for these individuals. For example, leading those in areas of low service access to travel over 200 km roundtrip to external NSP, rely on unofficial secondary distribution networks, and/or share and reuse injection equipment (Holeksa Citation2022).

As SWP are a fundamental group with regard to providing care for PWUD, understanding their viewpoints is essential to ensure the offering of the full range of available, evidence-based services. Qualitative research has explored SWP perceptions of harm reduction and drug-related care in Sweden (Richert, Stallwitz, and Nordgren Citation2023; von Reis and Wendel Citation2022), but these attitudes have not been assessed in a quantitative manner. The Harm Reduction Acceptability Scale (HRAS) has been used in other settings to assess attitudes towards such interventions (Ciccarelli et al. Citation2021; Estreet et al. Citation2017; Fenster and Monti Citation2017; Goddard Citation2003; Havranek and Stewart Citation2006; S. K. Moore and Mattaini Citation2014). Placing SWP attitudes the context of their respective settings’ development of harm reduction may offer a valuable reflection of changing Swedish drug policy and its relationship to care provider attitudes, as well as speak to qualities of care for clients in different areas. In describing and exploring these views, we can gain valuable insights into what the attitudes are at this point, within the context of the history of Swedish harm reduction development. This will also allow us to consider what the possibilities are for the future.

Aim

The primary aim of this study is to assess the attitudes to a variety of different goals related to the care of PWUD, as well as specific harm reduction services, in three areas of Sweden (detailed below) with very different developments of their harm reduction landscape. A secondary aim was to explore SWP perceptions of the availability of different services for PWUD, to understand practical equality of access to care across these geographical areas.

Materials and methods

Setting

This study was undertaken in three settings which may be described as ‘high’, ‘medium’, and ‘low’ levels of harm reduction offering, in the Swedish context. The three areas of focus have had extremely different development of their harm reduction services, offering an opportunity for potential insights to map how these local differences may relate to attitudes of SWP.

High – Malmö – population 344,000

The southern county of Skåne in Sweden has been characterized by leading the development of harm reduction in Sweden. Focusing on the city of Malmö, which was home to the country’s second NSP in 1987, initially allowed on an experimental basis. The programme here is also piloting an NSP option which does not initially require identification, a first in Sweden. OST began to be offered in 1990; it is in its lowest threshold form in this region, offering more agency and choice over care provider, than other regions (Andersson and Johnson Citation2020). It also has a comparatively very high number of clinics to choose from, with six in the municipality itself and 25 in the whole region. There is also more easily available primary care for OST patients in Malmö. Malmö offers Housing First programmes, as well as low threshold overnight shelters which allow substance use, if not supervised consumption. A take-home naloxone programme was first and most openly offered here, through experimental projects (Troberg et al. Citation2020).

Medium – Gothenburg – population 579,000

The second-largest city in Sweden, Gothenburg, has until recently had more limited access to harm reduction services. The first NSP was opened after decades of political pushback, in late 2018. The OST programme in Gothenburg began in 2004. There are five OST clinics in the municipality, however in late 2021 there was a stop on intaking new OST patients, likely due to lack of system capacity. Housing First programmes are offered in Gothenburg.

Low – Gävleborg – population 285,000

The region of Gävleborg was included due to its overall limited harm reduction programmes. This area is a region (made up of 10 smaller municipalities), as opposed to the others which are single municipalities, in order to increase the possible respondent pool. A NSP began in 2022. Access to OST began in the late 00’s, and remains very limited, with only two clinics in the region. Overdose prevention and naloxone distribution are limited in the region. Housing First programmes are offered in some, but not all, municipalities. This means that PWUD are actively excluded from municipal housing services in many municipalities. Much in/outpatient treatment is based on a 12-step methodology. Gävleborg is the region in Sweden with the highest average rate of drug-related mortality over the period 2017–2021 (Socialstyrelsen, Citationn.d.).

Survey distribution

An anonymous online survey was distributed to potential participants using Sunet Survey. Inclusion criteria were that the individual was employed within the municipal social services within one of the three settings, working broadly with questions of substance use or clients who use drugs (self-selection, as this was therefore per their own definition). The online survey was launched in two waves. First, as described in Nordgren and Richert (Citation2022) the survey was distributed via emailed web link in Malmö from May to August 2020. The second wave of the survey was launched to Gothenburg and Gävleborg from April to November 2021. The survey was distributed to section heads, and other contacts within the social services, and utilized snowball sampling.

Data

There were 216 responses to the survey. Eight responses were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria, six from Gothenburg, one from Malmö, and one from Gävleborg, due to lack of confirmation that they worked for the municipal social services, or indication in an open response field that they worked for the healthcare services, which was not within the remit of the current study. A total of 208 valid responses were included in the analysis.

Measures and analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27. The survey included demographic and descriptive questions regarding age, gender, working history, education level, current position, client makeup, client contact, among others. Descriptive statistics were compared using pairwise comparisons, utilizing chi-square test to assess for significance, with Malmö as the reference category.

The survey utilized a selection of 14 (of 25) items from the Harm Reduction Acceptability Scale (HRAS) (Goddard Citation2003). The scale, developed by Goddard (Citation2003), poses questions regarding beliefs about the philosophy and important treatment goals of services, such as ‘People living in publicly funded housing must be drug and alcohol free’. The HRAS is assessed via Likert scale (1–5) with 1 indicating strong agreement, and 5 strong disagreement. A reliability analysis was conducted, indicating that Question 1 of the HRAS was less consistent than other questions (corrected item-total correlation 0.316) where the others ranged from 0.476 to 0.711. Based on this, as well as the wording of the question being deemed to not align as directly with the others in the philosophy or goals of harm reduction per se, this question was excluded from further analysis. Cronbach’s alpha with the remaining questions was 0.88, indicating high internal consistency.

Scores for the HRAS were created by calculating the mean per participant. To explore the impact of geographic location on HRAS score, we performed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc correction, which allowed us to also examine differences between groups. To control for the influence of demographic factors, particularly given the slightly different demographic makeup in each location, including age, education as a social worker, and official decision-making capacity,Footnote1 we performed an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Pearson’s chi-square tests were then performed to test the significance of the geographic association with all HRAS questions individually.

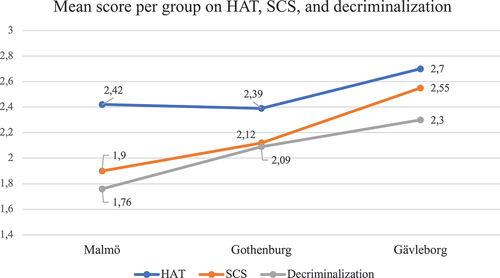

Following this, questions were asked about views on implementation of three methods currently not available in Sweden: heroin-assisted treatment (HAT), supervised consumption sites (SCS), and decriminalization of drugs for personal use. These were scored on a scale from 1 to 3, 1 indicating ‘should absolutely be implemented’, 2 being ‘should possibly be implemented’ and 3 being ‘should not be implemented’. Again, these were calculated into means and compared utilizing a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc correction to examine the association of scores to geography, and to assess for differences between groups.

Finally, there were a number of Likert-scale (1–3) style questions, assessing perceptions about their clients’ access to various services. For these questions, a mean score was created with 1 being ‘low’ access to a service, 2 being ‘medium’ access, and 3 being ‘high’ access. ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc correction was then used to analyse differences, again using Malmö as the reference category for this analysis.

Results

Sample characteristics

presents the demographic and work-related characteristics of the participants in the three regions. Respondents in Gävleborg were significantly older, and significantly fewer had bachelor’s level education in Social Work. Fewer individuals in Malmö reported having executive decision-making power than the other two cities. Other than these differences, the groups were overall similar with regard to their breakdown by gender, their direct engagement with clients, those who had managerial roles, and those who work with PWUD as a primary target group.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Social work professionals’ attitudes towards harm reduction on the HRAS

displays the results of the HRAS. The overall mean on this scale was 2.2. 89% of participants scored between 1 and <3 indicating that they have an overall positive view about harm reduction, as 3 is a ‘neutral’ response and any score below 3 is at least minimally positive. Respondents from Gävleborg had higher minimum and maximum scores, with no individuals having the lowest possible score of 1, which would indicate total acceptance of harm reduction philosophy and goals. There was a statistically significant difference between groups as determined by one-way ANOVA, F(2, 205) = 10.9, p = < .001.

Table 2. HRAS scores by location.

A Bonferroni post hoc test, displayed in , revealed that respondents in Gävleborg had significantly higher mean HRAS scores than respondents from Malmö and Gothenburg at the 0.05 level, indicating less positive views towards harm reduction. There was no statistically significant difference between Malmö and Gothenburg respondents. ANCOVA testing showed that there are significant differences between regions, after controlling for age, education level and decision-making power.

Table 3. Post-hoc comparisons of HRAS score stratifying by location.

Regarding the responses to individual questions on the HRAS, the attitudes tended to reflect the level of development of harm reduction in the three different areas, with Malmö having the most positive attitudes, Gothenburg tending to be in the middle of the other two, and Gävleborg respondents having the least positive attitudes. This was the case for the following questions: ‘opioid users should only be prescribed methadone/buprenorphine for a limited time’. (agree: 5% Malmö, 13% Gothenburg, 25% Gävleborg, p = .002), ‘people who live in publicly funded housing must be alcohol and drug-free’ (strongly disagree: 40% Malmö, 39% Gothenburg, 9% Gävleborg, p = 0.000), and finally, ‘abstinence is the only acceptable treatment goal for people who use illicit drugs’ (strongly disagree: 50% Malmö, 45% Gothenburg, 22% Gävleborg, p = 0.002).

Willingness to implement new harm reduction measures

presents the results of questions examining the willingness to implement three specific interventions which do not currently exist in Sweden: HAT, SCS, and decriminalization of drugs for personal use. Lower scores again indicated more positive attitudes. Means indicated that the majority of participants were opposed to the immediate implementation of these programmes, particularly HAT, where only 9% of respondents felt this should definitely be implemented.

There were significant differences between the three groups. Gävleborg participants were more negative to the implementation of HAT and SCS than those in the other two cities. For HAT F(2, 200) = 3.816, p = 0.024, post hoc testing revealing p = 0.05 Malmö, 0.028 Gothenburg. For SCS F(2, 199) = 12.12, p = < .001, p = < 0.001 Malmö, 0.004 Gothenburg. Significantly fewer individuals in both Gothenburg (p = 0.025) and Gävleborg (p = < 0.001) felt that decriminalization should be implemented as compared to Malmö, F(2, 204) = 7.493, p = 0.001. Overall, responses to these interventions can be interpreted as more ambivalent or negative than to the HRAS.

Interestingly, on a specific question posed only to respondents in Gävleborg, where no NSP existed at the time of the survey, just over half (55%) of respondents stated that a NSP should be implemented, with 9% saying it should not be (with the remaining 36% reporting that it should ‘possibly’ be implemented).

Perceived access to services for PWUD

Participants were asked to report their clients’ perceived access to a variety of different services, on a scale of 1 (low) to 3 (high). Most interesting here were the differences in reported access to abstinence-based services, coercive care, harm reduction services (OST, NSP, overdose prevention), and outpatient addiction care, presented in . Here, we can see those participants in Gävleborg felt that their clients had significantly better access to structured outpatient care, abstinence-based care or detox, and coercive care. Conversely, Malmö respondents reported better perceived access to OST, NSP, and overdose prevention than the other two cities. Differences may also reflect different client needs, or differing traditions of care – where, as explained, OST, NSP, and overdose prevention is reported to be more accessible in Malmö, a city with a history of harm reduction, and where coercive and abstinence-based care is rated to be more accessible in Gävleborg, this form of care may be used more in this locality.

Table 4. Comparing perceived access to services by geographic location.

Discussion

The results demonstrate that most SWP held positive attitudes towards the philosophy of harm reduction and related treatment goals. However, the magnitude of acceptability varied by geography. The impact of geographical setting remained significant even when controlling for age, education levels, and working role. These geographic differences could be understood to reflect the differences in the harm reduction landscape in these localities, where respondents from an area with limited access to harm reduction services (Gävleborg) had significantly more negative attitudes. In practice, this could mean that SWPs are less likely to refer their clients to harm reduction-based services or forms of care. When it comes to the acceptability of implementing specific interventions which do not currently exist in Sweden – HAT, SCS, and the decriminalization of drugs for personal use – opinions were more negative overall, and these results also remained geographically stratified. Only a small minority were positive to implementation of HAT. Results were much more mixed for the possibility of supervised consumption rooms and decriminalization. This is interesting in the context of Sweden’s rate of drug-related deaths, reportedly several times higher than the EU average (EMCDDA - European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction Citation2020). Again, the extent of acceptability of these interventions follow the harm reduction development of the areas, where Gävleborg, the area with the least developed harm reduction, had the most negative attitudes, whereas attitudes were most positive in Malmö, and Gothenburg was in the middle. The results also point to unequal access to care and treatment in the different regions, indicating that national policies and guidelines are implemented differently. Interpreted together, this could indicate a double vulnerability for clients – where negative attitudes to harm reduction services could amplify existing practical disparities in care offerings on the ground. In areas where SWPs do not accept the goals of harm reduction, this may mean more stigmatizing care encounters for clients who do not have abstinence as a goal of treatment (Richert, Stallwitz, and Nordgren Citation2023).

It is increasingly agreed upon that a system which ‘target[s] users’ needs and preferences, instead of the traditional standard of assessing, adjusting, and fitting users into existing services’ (Lago, Peter, and Maria Bógus Citation2017) (6), may be ideal, such as that which represents the foundation of harm reduction. However, there are critiques surrounding harm reduction, which arise from concerns surrounding its execution, how it is offered in practice (Andersen and Järvinen Citation2007; McKeganey Citation2006; Roe Citation2005). There has been a general resistance to many harm reduction interventions among social workers in Sweden, observed also in the current study in the negative responses to implementation of HAT. This is, among other reasons, due to the view that harm reduction interventions are overly medicalized, as well as the idea that it sends the ‘wrong signal’, not aligning with the Swedish zero-tolerance policy (Johnson Citation2007). It is interesting to consider the meaning of overall positive scores on the HRAS, contrasted with negativity towards the specific interventions. This may relate to the fact that there is an uncertainty and lack of knowledge regarding these interventions which are not yet implemented.

There are other concerns, for example, that there is a risk that development of harm reduction takes place at the expense of other efforts (Roe Citation2005). It is worth noting that respondents from Gävleborg reported the highest perceived level of access to structured outpatient care. This may reflect the belief that sufficient investments in resources for prevention and ambitious treatment may offset the need for investment in harm reduction. While we cannot determine causality, the analysis on currently not-implemented interventions may indicate that it is the implementation of the service that influences the attitudes towards these, improving the knowledge, local discussion, or experience with these forms of care. The results may also demonstrate the impact of local norms, where attitudes to harm reduction among politicians and officials also affect social workers in the different regions. Municipalities in Sweden have had veto power over the development of services; therefore, the general attitude of decision-makers in an area may be reflected by the take-up of harm reduction initiatives. Proponents, researchers, and politicians in Malmö have driven the development of harm reduction over a long period of time. Malmö’s proximity to Denmark, where harm reduction is much more developed and lower in threshold, also may influence the perceived acceptability of these services and treatment goals. In other cities and regions, the development has looked very different, with more political and local resistance. This could indicate the more one is exposed to harm reduction in the workplace setting, the more open one is to such notions, inferred here as the degree of positivity on the HRAS score reflected the harm reduction offerings in the area. It may be interesting to do a follow-up study after the implementation of more harm reduction services (such as NSP) in Gävleborg to confirm this or see how attitudes change over time.

Attitudes are learned through socialization, influence thoughts and behaviours, express our values, and can play a functional role (Perloff Citation2020). People and their attitudes are dynamic, changeable and influenced by those around them, values, sociocultural messages, institutional norms, previous knowledge, political leanings, personality traits, and may not be immediately reactive to changes in the evidence-basis (Hoffmann, Chang, and Lewis Citation2000; Maccoun et al. Citation1993; Perloff Citation2020; Russell, Davies, and Hunter Citation2011). Changing these attitudes relates to changing the ‘doxa’ of the system – a changing of the institutional context – through education, professional development, exposure to new paradigms, and breaking of existing routines (Heller, McCoy, and Cunningham Citation2004; Wallander and Blomqvist Citation2009). The political and legal context also have a role to play in attitude formation. In Sweden, aligned with its zero-tolerance policy, norms towards drug use are socially stigmatizing (Christensson and Ljungberg Citation1991), which may contribute to difficulty accepting a harm reduction paradigm (Green et al. Citation2013; Heller, McCoy, and Cunningham Citation2004). Some authors therefore suggest that reforms such as implementation of harm reduction services do not go far enough in changing our approach towards and view of substance use (Keane Citation2003; D. Moore and Fraser Citation2006).

Nevertheless, evaluations of the impact of various forms of harm reduction education curricula, professional development, and training have been undertaken in numerous settings, and are associated with positive or improved attitudes towards substance use and/or harm reduction interventions (Aletraris et al. Citation2016; Estreet et al. Citation2017; Eversman Citation2012; Fenster and Monti Citation2017; Goddard Citation2003; S. K. Moore and Mattaini Citation2014; Muzyk et al. Citation2020; Sheridan et al. Citation2018; Sulzer et al. Citation2021). For example, the HRAS (or adaptations of it) has been used to demonstrate this previously in three American intervention studies, one conducted on treatment professionals, and two on social work students (Estreet et al. Citation2017; Goddard Citation2003; S. K. Moore and Mattaini Citation2014). The mean pre-intervention scores in these studies all aligned closely with scores in Gävleborg. All scores were reported to improve with an intervention, while the post-intervention testing in Goddard’s (Citation2003) study aligned with scores in Gothenburg. This could be interpreted that professional exposure to harm reduction may act as a sort of ‘intervention’ which can dispel negative beliefs or scepticism sometimes associated with these services. In addition to improving the offering of courses on substance use at the university level, ongoing short courses or training could be offered to established SWP, to allow for continuing professional development for individuals already in the field.

The results of this study are particularly relevant because previous research has demonstrated that the expectation or experience of stigma or judgement in healthcare settings may deter people from seeking care – addiction-related or otherwise (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, and Link Citation2013; McNeece Citation2003; Neale, Tompkins, and Sheard Citation2007; Rivera et al. Citation2014; van Boekel et al. Citation2013). Abstinence-based philosophies constitute a barrier to care and discourage individuals accessing them, due to high threshold criteria and/or inability (or lack of desire) to meet institutional goals, punitive policies, and may engender moralized judgements (Appel et al. Citation2004; Hyshka et al. Citation2019; Knudsen et al. Citation2005; Richard et al. Citation2020; Schulte et al. Citation2013). Exemplifying this, a study conducted in Sweden found that some individuals reported ‘self-treatment’ with illicitly obtained OST medications due to precisely the above-listed barriers (Richert and Johnson Citation2015). Conversely, a harm reduction context can ‘[provide] a basis for the development of relationships and [shifts] the moral orientation to reducing harm as a primary moral principle’ (Pauly Citation2008, 195). Programmes built on this philosophy have been demonstrated to promote reticent individuals to engage, build a therapeutic relationship and sense of trust with care providers, along with other positive secondary benefits such as facilitating referrals to other services and improvement of self-identity (Alanko Blomé et al. Citation2017; Lee and Petersen Citation2009; Macneil and Pauly Citation2011; Ostertag et al. Citation2006; Rance and Treloar Citation2014; Treloar et al. Citation2016). Harm reduction and social work share many core values and goals such as respect for client autonomy and self-determination, starting where the client is, and viewing the client as an expert to create a collaborative working alliance (Vakharia and Little Citation2017). These similarities, along with the overall positive attitude to harm reduction among the SWP in this study, should provide great opportunities to include a harm reduction perspective in social work with PWUD in Sweden.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. Firstly, attitudes are not the only factor which drives behaviour. The actions that SWP take may be constrained by regulations, guidelines, organizational approaches, resource availability, etc. and may contradict their individual attitudes. This is especially relevant as this study takes place in three different settings, with different local conditions such as different client make-up and needs, different offerings, and resources. Additionally, this study’s results may have been affected by both a response bias, in that those who responded may be more engaged and interested in such questions, leading to more positive results, as well as social desirability bias. The sample sizes and demographic make-ups in each region were different, and one area (Gävleborg) was less urban than the other two.

Conclusion

This study has provided an exploration of current attitudes towards harm reduction amongst SWPs in three different areas of Sweden. The results of the current study demonstrate overall positive attitudes towards the philosophy and treatment goals of harm reduction. However, the magnitude of positivity was geographically stratified, and may indicate that attitudes are contingent on local exposure to such ideas. Attitudes towards practical harm reduction interventions such as HAT and SCS were more moderate or negative. Ideological positions continue to influence SWP, which ultimately impacts the types of advice and services their clients have access to. Education and professional development interventions should be implemented to reflect changes in the evidence basis, approaches to substance use problems, and resulting institutional ideologies, in order to achieve the best care for PWUD. It is also important that national guidelines or legislation which set requirements cannot be negotiated away by, for example, a veto, as has been the case in Sweden. This will increase the possibility of equal care throughout the country.

Abbreviations

| HAT – | = | heroin assisted treatment |

| NSP – | = | needle and syringe exchange programme(s) |

| OST – | = | opioid substitution therapy |

| SCS – | = | supervised consumption site |

| SWP – | = | social work professional(s) |

Ethics

Survey respondents gave their informed consent to participate, and responded anonymously. All institutional ethical guidelines were adhered to. The current study was not deemed to require ethical approval to be sought, under Swedish law (2003:460) on ethical review of research which concerns people, as it investigated professional’s attitudes and did not discuss sensitive topics nor sensitive personal data.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to first thank all of those who took time to complete the survey, as well as those who assisted with distribution, including research colleagues at the Department of Social Work at Gothenburg University and Linneaus University, and those at the Region of Gävleborg and Göteborgs kommun. Thanks to Johan Nordgren who was involved with the design of the survey and data collection in Malmö. We would also like to thank Björn Johnson for his comments on the manuscript and assistance with statistical analyses, as well as Caroline Adolfsson and Robert Svensson for their further input on statistical analyses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This refers to individuals who have the authority to make decisions about interventions such as granting housing, rejecting an application for treatment, or financial assistance. This is in contrast to people who, for example, only work with support, and who do not make decisions.

References

- Alanko Blomé, M., P. Björkman, L. Flamholc, H. Jacobsson, and A. Widell. 2017. “Vaccination Against Hepatitis B Virus Among People Who Inject Drugs – a 20-year Experience from a Swedish Needle Exchange Program.” Vaccine 35 (1): 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.041.

- Aletraris, L., M. Bond Edmond, M. Paino, D. Fields, and P. M. Roman. 2016. “Counselor Training and Attitudes Toward Pharmacotherapies for Opioid Use Disorder.” Substance Abuse 37 (1): 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2015.1062457.

- Andersen, D., and M. Järvinen. 2007. “Harm Reduction – Ideals and Paradoxes.” Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 24 (3): 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/145507250702400301.

- Andersson, L., and B. Johnson. 2020. “Patient Choice As a Means of Empowerment in Opioid Substitution Treatment: A Case from Sweden.” Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy 27 (2): 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2019.1591342.

- Appel, P. W., A. A. Ellison, H. K. Jansky, and R. Oldak. 2004. “Barriers to Enrollment in Drug Abuse Treatment and Suggestions for Reducing Them: Opinions of Drug Injecting Street Outreach Clients and Other System Stakeholders.” The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 30 (1): 129–153. https://doi.org/10.1081/ADA-120029870.

- Beletsky, L., R. Ruthazer, G. E. Macalino, J. D. Rich, L. Tan, and S. Burris. 2007. “Physicians’ Knowledge of and Willingness to Prescribe Naloxone to Reverse Accidental Opiate Overdose: Challenges and Opportunities.” Journal of Urban Health 84 (1): 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-006-9120-z.

- Brocato, J., and E. F. Wagner. 2003. “Harm Reduction: A Social Work Practice Model and Social Justice Agenda.” Health & Social Work 28 (2): 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/28.2.117.

- Brown, A. R. 2022. “Health Professionals’ Attitudes Toward Medications for Opioid Use Disorder.” Substance Abuse 43 (1): 598–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2021.1975872.

- Christensson, B., and B. Ljungberg. 1991. “Syringe Exchange for Prevention of HIV Infection in Sweden: Practical Experiences and Community Reactions.” International Journal of the Addictions 26 (12): 1293–1302. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089109062161.

- Ciccarelli, T., M. Soberman, T. Leshuk, H. Cole, F. Afreen, and L. A. Manwell. 2021. “Is Cleanliness Next to Abstinence? The Effect of Cleanliness Priming on Attitudes Towards Harm Reduction Strategies for People with Substance Use Disorders.” International Journal of Psychology 56 (2): 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12703.

- Ding, L., B. E. Landon, I. B. Wilson, M. D. Wong, M. F. Shapiro, and P. D. Cleary. 2005. “Predictors and Consequences of Negative Physician Attitudes Toward HIV-Infected Injection Drug Users.” Archives of Internal Medicine 165 (6): 618. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.6.618.

- Ekendahl, M. 2011. “Socialtjänst Och Missbrukarvård: Bot Eller Lindring?” Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 28 (4): 297–319. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10199-011-0027-y.

- EMCDDA - European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. 2020. European Drug Report : Trends and Developments. Luxemboug: Publications office of the European Union.

- Eriksson, L., and J. Edman. 2017. “Knowledge, Values, and Needle Exchange Programs in Sweden.” Contemporary Drug Problems 44 (2): 105–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450917700143.

- Estreet, A., M. T. T. Paul Archibald, S. Goodman, and T. Cudjoe. 2017. “Exploring Social Work Student Education: The Effect of a Harm Reduction Curriculum on Student Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Opioid Use Disorders.” Substance Abuse 38 (4): 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2017.1341447.

- Eversman, M. H. 2012. “Harm Reduction in MSW Substance Abuse Courses.” Journal of Teaching in Social Work 32 (4): 392–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2012.703984.

- Fenster, J., and K. Monti. 2017. “Can a Course Change Social Work Students’ Attitudes Toward Harm Reduction as a Treatment Option for Substance Use Disorders?” Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 35 (1): 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2016.1257895.

- Goddard, P. 2003. “Changing Attitudes Towards Harm Reduction Among Treatment Professionals: A Report from the American Midwest.” International Journal of Drug Policy 14 (3): 257–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-3959(03)00075-6.

- Green, T. C., S. E. Bowman, N. D. Zaller, M. Ray, P. Case, and R. Heimer. 2013. “Barriers to Medical Provider Support for Prescription Naloxone as Overdose Antidote for Lay Responders.” Substance Use & Misuse 48 (7): 558–567. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2013.787099.

- Gunne, L. M. 1983. “The Case of the Swedish Methadone Maintenance Treatment Programme.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 11 (1): 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/0376-8716(83)90104-7.

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., J. C. Phelan, and B. G. Link. 2013. “Stigma as a Fundamental Cause of Population Health Inequalities.” American Journal of Public Health 103 (5): 813–821. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069.

- Havranek, J. E., and J. R. Stewart. 2006. “Rehabilitation Counselors’ Attitudes Toward Harm Reduction Measures.” Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling 37 (1): 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1891/0047-2220.37.1.38.

- Heller, D., K. McCoy, and C. Cunningham. 2004. “An Invisible Barrier to Integrating HIV Primary Care with Harm Reduction Services: Philosophical Clashes Between the Harm Reduction and Medical Models.” Public Health Reports 119 (1): 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490411900109.

- Hoffmann, N. G., A. J. Chang, and D. C. Lewis. 2000. “Medical Student Attitudes Toward Drug Addiction Policy.” Journal of Addictive Diseases 19 (3): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1300/J069v19n03_01.

- Holeksa, J. 2022. “Dealing with Low Access to Harm Reduction: A Qualitative Study of the Strategies and Risk Environments of People Who Use Drugs in a Small Swedish City.” Harm Reduction Journal 19 (1): 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-022-00602-y.

- Housenbold Sieger, B. 2005. “An Exploratory Study of Social Workers’ Attitudes Toward Harm Reduction with Substance Abusing Individuals Utilizing the Substance Abuse Treatment Survey (SATS) (New York University Dissertations Publishing).”

- Hyshka, E., H. Morris, J. Anderson-Baron, L. Nixon, K. Dong, and G. Salvalaggio. 2019. “Patient Perspectives on a Harm Reduction-Oriented Addiction Medicine Consultation Team Implemented in a Large Acute Care Hospital.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 204:107523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.025.

- Järvinen, M. 2006. “Mötet Mellan Klient Och System - Om Forskning i Socialt Arbete.” Dansk Sociologi 13 (2): 73–84. https://doi.org/10.22439/dansoc.v13i2.493.

- Javadi, R., K. Lagana, T. Krowicki, D. Bennett, and B. Schindler. 2021. “Attitudes Toward Harm Reduction Among Substance Use Treatment Professionals in Philadelphia.” Journal of Substance Use 27 (5): 459–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2021.1961320.

- Johnson, B. 2007. “After the Storm: Developments in Maintenance Treatment Policy and Practice in Sweden 1987–2006.” In On the Margins: Nordic Alcohol and Drug Treatment 1885– 2007, edited by J. Edman and K. Stenius. Helsinki: NAD Publications 259–287.

- Keane, H. 2003. “Critiques of Harm Reduction, Morality and the Promise of Human Rights.” International Journal of Drug Policy 14 (3): 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00151-2.

- Knudsen, H. K., L. J. Ducharme, P. M. Roman, and T. Link. 2005. “Buprenorphine Diffusion: The Attitudes of Substance Abuse Treatment Counselors.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 29 (2): 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2005.05.002.

- Lago, R. R., E. Peter, and C. Maria Bógus. 2017. “Harm Reduction and Tensions in Trust and Distrust in a Mental Health Service: A Qualitative Approach.” Substance Abuse: Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-017-0098-1.

- Ledberg, A. 2017. “Mortality Related to Methadone Maintenance Treatment in Stockholm, Sweden, During 2006–2013.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 74:35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2016.12.005.

- Lee, H. S., and S. R. Petersen. 2009. “Demarginalizing the Marginalized in Substance Abuse Treatment: Stories of Homeless, Active Substance Users in an Urban Harm Reduction Based Drop-In Center.” Addiction Research and Theory 17 (6): 622–636. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066350802168613.

- Maccoun, R. J., P. Reuter, J. Kahan, T. Schelling, L. Dair, P. Green-Wood, J. Caulkins, N. Kerr, S. Garber, and H. Gras-Mick. 1993. “Drugs and the Law: A Psychological Analysis of Drug Prohibition.” Psychological Bulletin 113 (3): 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.113.3.497.

- Macneil, J., and B. Pauly. 2011. “Needle Exchange as a Safe Haven in an Unsafe World.” Drug and Alcohol Review 30 (1): 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00188.x.

- McKeganey, N. 2006. “The Lure and the Loss of Harm Reduction in UK Drug Policy and Practice.” Addiction Research & Theory 14 (6): 557–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350601002369.

- McNeece, A. C. 2003. “After the War on Drugs Is Over.” Journal of Social Work Education 39 (2): 193–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2003.10779131.

- Moore, D., and S. Fraser. 2006. “Putting at Risk What We Know: Reflecting on the Drug-Using Subject in Harm Reduction and Its Political Implications.” Social Science and Medicine 62 (12): 3035–3047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.067.

- Moore, S. K., and M. A. Mattaini. 2014. “US Social Work Students’ Attitudes Shift Favorably Towards a Harm Reduction Approach to Alcohol and Other Drugs Practice: The Effectiveness of Consequence Analysis.” Social Work Education 33 (6): 788–804. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2014.919106.

- Muzyk, A., Z. P. W. Smothers, K. M. Andolsek, M. Bradner, J. P. Bratberg, S. A. Clark, K. Collins, et al. 2020. “Interprofessional Substance Use Disorder Education in Health Professions Education Programs.” Academic Medicine 95 (3): 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003053.

- Myles, A., G. J. Mugford, J. Zhao, M. Krahn, and P. Peter Wang. 2011. “Physicians’ Attitudes and Practice Toward Treating Injection Drug Users Infected with Hepatitis C Virus: Results from a National Specialist Survey in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology 25 (3): 135–139. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/810108.

- Neale, J., C. Tompkins, and L. Sheard. 2007. “Barriers to Accessing Generic Health and Social Care Services: A Qualitative Study of Injecting Drug Users.” Health & Social Care in the Community 16 (2): 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00739.x.

- Nordgren, J., and T. Richert. 2022. “Risk Environments of People Who Use Drugs During the COVID-19 Pandemic – the View of Social Workers and Health Care Professionals in Sweden.” Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy 29 (3): 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2022.2051435.

- Ogborne, A. C., and C. Birchmore-Timney. 1998. “Support for Harm-Reduction Among Staff of Specialized Addiction Treatment Services in Ontario, Canada.” Drug and Alcohol Review 17 (1): 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595239800187591.

- Olsen, Y., and J. M. Sharfstein. 2014. “Confronting the Stigma of Opioid Use Disorder—And Its Treatment.” JAMA 311 (14): 1393. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.2147.

- Ostertag, S., B. R. E. Wright, R. S. Broadhead, and F. L. Altice. 2006. “Trust and Other Characteristics Associated with Health Care Utilization by Injection Drug Users.” Journal of Drug Issues 36 (4): 953–974. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260603600409.

- Pauly, B. 2008. “Shifting Moral Values to Enhance Access to Health Care: Harm Reduction As a Context for Ethical Nursing Practice.” International Journal of Drug Policy 19 (3): 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.02.009.

- Perloff, R. M. 2020. The Dynamics of Persuasion: Communication and Attitudes in the Twenty-First Century. 7th ed. New York: Routledge.

- Rance, J., and C. Treloar. 2014. “‘Not Just Methadone Tracy’: Transformations in Service-User Identity Following the Introduction of Hepatitis C Treatment into Australian Opiate Substitution Settings.” Addiction 109 (3): 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12392.

- Richard, E. L., C. A. Schalkoff, H. M. Piscalko, D. L. Brook, A. L. Sibley, K. E. Lancaster, W. C. Miller, and V. F. Go. 2020. “‘You Are Not Clean Until You’re Not on Anything’: Perceptions of Medication-Assisted Treatment in Rural Appalachia.” International Journal of Drug Policy 85:102704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102704.

- Richert, T., and B. Johnson. 2015. “Long-Term Self-Treatment with Methadone or Buprenorphine as a Response to Barriers to Opioid Substitution Treatment: The Case of Sweden.” Harm Reduction Journal 12 (1): 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-015-0037-2.

- Richert, T., A. Stallwitz, and J. Nordgren. 2023. “Harm Reduction Social Work with People Who Use Drugs: A Qualitative Interview Study with Social Workers in Harm Reduction Services in Sweden.” Harm Reduction Journal 20 (1): 146. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00884-w.

- Rivera, A. V., J. DeCuir, N. D. Crawford, S. Amesty, and C. Fuller Lewis. 2014. “Internalized Stigma and Sterile Syringe Use Among People Who Inject Drugs in New York City, 2010-2012.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 144:259–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.09.778.

- Roe, G. 2005. “Harm Reduction as Paradigm: Is Better Than Bad Good Enough? The Origins of Harm Reduction.” Critical Public Health 15 (3): 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581590500372188.

- Russell, C., J. B. Davies, and S. C. Hunter. 2011. “Predictors of Addiction Treatment Providers’ Beliefs in the Disease and Choice Models of Addiction.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 40 (2): 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2010.09.006.

- Schulte, B., C. Sybille Schmidt, O. Kuhnigk, I. Schäfer, B. Fischer, H. Wedemeyer, and J. Reimer. 2013. “Structural Barriers in the Context of Opiate Substitution Treatment in Germany - a Survey Among Physicians in Primary Care.” Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 8 (1): 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-8-26.

- Sheridan, J., P. Adams, C. Bullen, and D. Newcombe. 2018. “An Evaluation of a Harm Reduction Summer School for Undergraduate Health Professional Students.” Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy 25 (2): 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2016.1262824.

- Skogens, L. 2005. “Om Personliga Faktorers Betydelse För Socialarbetares Agerande Vid Tecken På Alkoholproblem Hos Klienter.” Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 22 (5): 317–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/145507250502200508.

- Socialstyrelsen. n.d. “Statistikdatabas för dödsorsaker.” https://sdb.socialstyrelsen.se/if_dor/val.aspx.

- Sulzer, S. H., S. Prevedel, T. Barrett, M. Wright Voss, C. Manning, and E. Fanning Madden. 2021. “Professional Education to Reduce Provider Stigma Toward Harm Reduction and Pharmacotherapy.” Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy 29 (5): 576–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2021.1936457.

- Treloar, C., J. Rance, K. Yates, and L. Mao. 2016. “Trust and People Who Inject Drugs: The Perspectives of Clients and Staff of Needle Syringe Programs.” International Journal of Drug Policy 27:138–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.08.018.

- Troberg, K., P. Isendahl, M. Alanko Blomé, D. Dahlman, and A. Håkansson. 2020. “Protocol for a Multi-Site Study of the Effects of Overdose Prevention Education with Naloxone Distribution Program in Skåne County, Sweden.” BMC Psychiatry 20 (1): 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-2470-3.

- Tryggvesson, K. 2012. “”Sprutbyte – Visst Bara de Slutar Med Droger”. Svenska Myndigheters Och Politikers Hantering Av Rena Sprutor till Narkomaner.” Nordic Studies on Alcohol & Drugs 29 (5): 519–540. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10199-012-0044-5.

- Vakharia, S. P., and J. Little. 2017. “Starting Where the Client Is: Harm Reduction Guidelines for Clinical Social Work Practice.” Clinical Social Work Journal 45 (1): 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-016-0584-3.

- van Boekel, L. C., P. M. B. Evelien, J. van Weeghel, and F. L. G. Henk. 2013. “Stigma Among Health Professionals Towards Patients with Substance Use Disorders and Its Consequences for Healthcare Delivery: Systematic Review.” Drug & Alcohol Dependence 131 (1–2): 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018.

- von Reis, T., and V. Wendel. 2022. “Socialsekreterare i svensk beroendevård—En komplex praktik med svårförenliga logiker: En kvalitativ intervjustudie av myndighetsutövande socialsekreterares balansering av olika intressen i socialtjänstarbete med vuxna substansbrukare.” Dissertation, Stockholm University. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-205404.

- Wallander, L., and J. Blomqvist. 2009. “Modeling Ideal Treatment Recommendations: A Factorial Survey of Swedish Social Workers’ Ideal Recommendations of Inpatient or Outpatient Treatment for Problem Substance Users.” Journal of Social Service Research 35 (1): 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488370802477436.

- Winograd, R. P., C. S. Davis, M. Niculete, E. Oliva, and R. P. Martielli. 2017. “Medical Providers’ Knowledge and Concerns About Opioid Overdose Education and Take-Home Naloxone Rescue Kits within Veterans Affairs Health Care Medical Treatment Settings.” Substance Abuse 38 (2): 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2017.1303424.