Abstract

To facilitate forest management as part of climate change mitigation and adaptation, the Forest Environment Transfer Tax (FETT) was introduced in Japan in 2019, representing a form of payment for ecosystem services. In this study, we focused on the introduction of the tax and the status of its use based on an analysis covering Japan’s 47 prefectures. This involved reviewing policy processes related to FETT and conducting a survey among relevant prefectural officers to identify how FETT is being used, with a focus on plans, policies, and systems related to forest data development and exchanges. The proportions of both total and FETT budgets used for forest data development were significant. Several prefectures are improving forest-related data in a two-way manner by coordinating with municipalities. Correlation analysis revealed that prefectures with greater proportions of privately owned forests allocated more budget to forest data development, which is in line with the FETT’s intended purpose. This result suggests that the absolute size of such forestlands is less important, but that the proportion of privately owned forests carries political and social weight that could be a critical factor in budget allocation.

1. Introduction

1.1. National strategies and the need to develop forest data

In Japan, current national plans and strategies related to forestry are rich in newly coined terms. For example, two symbolic documents, the Strategy for Sustainable Food Systems, MeaDRI (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan Citation2021; Miyake et al. Citation2022), and the Forest and Forestry Basic Plan (Forestry Agency Citation2021), were published in 2021. The aim of the Strategy for Sustainable Food Systems, MeaDRI (Note), is to balance production and environmental goals, particularly those related to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, through innovation. Similarly, the Forest and Forestry Basic Plan, approved by the Cabinet in June 2021, aims to improve the efficiency of production, distribution, and management of timber using information and communication technology (ICT) and integrated forest data based on aerial laser surveys and a global navigation satellite system (GNSS), with the main theme of achieving green growth. In the plan, forest data development—an integral part of improving efficiency—is positioned as an initiative to be promoted in individual forest plans, leading to the growth of environmentally sustainable forestry. The plan also includes the New Forest Management System (NFMS or Shinrin Keiei Kanri), which, among other things, expanded the roles of municipalities in national forest management—traditional forest management was conducted through the hierarchy of the Forestry Agencies, prefectures, and involved cooperation from forest owners, with the municipality playing a minor role. The NFMS is based on gathering forest data, including data at the municipality level. Information collection and sharing is arguably more challenging for the forestry sector than in agriculture because it is rather a new and additional task for the majority of municipalities and the national government; previously, prefectures were the main official implementing bodies. Municipalities are faced with limited human resources and capacities (Suzuki et al. Citation2020). Thus, ensuring effective information sharing between prefectures and municipalities and relevant forest managers is an urgent task.

As is clear from the two national strategies and plans, forest data development is being promoted at different scales through various policies and initiatives (Teraoka Citation2020). Their scope ranges from developing conventional forest plans to facilitating disaster prevention and alleviation, protecting biodiversity, and developing new sectors of tourism and recreation in the forestry sector. In the NFMS, unmanaged, privately owned artificial forests were identified as main policy target areas to be addressed, including sharing information relating to their boundaries, ownership (while protecting privacy), and management and operational histories. This relates to ongoing institutional and legal changes related to land ownership and land use in Japan, which go beyond overall national targets for industrial growth and decarbonization.

These changes are necessary because: first, the ownership of forestland, unlike residential or agricultural lands, is not well documented in certain regions—rather than being local residents, owners are frequently urban residents who have inherited lands; and second, the boundaries of ownership are unclear in certain areas (Kajima et al. Citation2020). These issues are driven by the following factors, which are becoming more prominent: (1) aging and depopulation in rural areas, (2) low-priced imported timber and wood products, and (3) lack of human resources in forest management due to the decline of the forestry industry in Japan.

Given these circumstances, there is a need to promote the development of forest data. In this regard, the majority of resource-scarce municipalities require the support of prefectures. One concrete form of support prefectures can offer is to teach municipalities how to identify owners with ambiguous forest land boundaries using information on microtopography and tree height in forest areas, estimated from aerial laser scans.

1.2. Forest Environment Transfer Tax and forest data

The Forest Environment Transfer Tax (FETT) was first introduced in 2019 alongside, and as a key financial mechanism of, the NFMS. Given the abovementioned expanded role of municipalities in the NFMS, they have received the majority of the FETT (80% in the earlier phase from 2019, increasing to 90% in the later phase starting in 2024). The rest of the FETT (20% in the earlier phase and 10% in the later phase) is allocated to prefectures (), which primarily support municipalities in forest data development. Specific prefectural support activities can be categorized into three categories: (1) capacity building and securing human resources, (2) transmitting technical and administrative know-how and providing training for municipality staff; and (3) supporting the development of forest data. For the latter, various data are essential, including the state of forests, their past operational history, and estimation of available forest resources, owners, and boundaries (Kohsaka and Uchiyama Citation2019). Forest data development is one of the main activities promoted under the FETT and relatively large portions of the budget are allocated to it; this includes three-dimensional elevation map data and laser forest type maps developed through the application of Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) (). LiDAR data can also be used to determine the boundaries of forests, with a view to promoting forest land registration. The use of this data is also gaining attention because it enables the efficient and accurate determination of the amount of forest resources.

Figure 1. Municipal forest management site in a municipality (Chichibu City) supported by its prefecture (Saitama Prefecture).

Table 1. Forest data based on aerial photographs.

Furthermore, forest data can be utilized as general evidence in evidence-based policy making (EBPM), which is called for by current science and technology policies (Cabinet Office Citation2021; Kohsaka Citation2021; Kohsaka and Kohyama Citation2022). To inform EBPM, prefectures use LiDAR data to compute the amount of forest resources and develop detailed topographic maps to enable rational use of the resources and conceptualize zoning (for example, areas oriented toward production or conservation). Both the MeaDRI and the Forest and Forestry Basic Plan highlight the innovations and technological breakthroughs offered by such information systems. However, there are challenges relating to human resources and institutional settings that are yet to be addressed, such as the need for training relating to the use and exchange of information and the extent of compatibility of the systems among different institutions under different jurisdictions (i.e. arrangements between prefectures, municipalities, forest associations, and private entities). If addressed correctly, these challenges, both at the prefectural level and in their collaborations with municipalities, can act as a driving factor in the promotion and application of these national-level strategies and plans.

1.3. Objective and existing studies

This paper presents and analyzes responses to a questionnaire which was given to prefectures with a view to enquiring about their FETT use in detail and overall trends in strategies, plans, and challenges relating to forest data development. We particularly focused on the status and trends of forest data development in prefectures using FETT.

There have been studies on overall trends of FETT use (Kohsaka and Uchiyama Citation2019) and studies focusing on urban–rural collaboration based on taxation (Ishizaki Citation2019; Kohsaka et al. Citation2020). However, given that the concept of FETT is relatively new, the number of studies in the field is limited. Furthermore, existing studies tend to focus on overall trends in tax usage. Kohsaka and Uchiyama (Citation2021) suggested three research topics for future research on FETT at the prefectural level: (1) the introduction of the tax and status of its use; (2) the effect of the tax; and (3) taxpayer perceptions. The present study contributes mainly to the first research topic; we focused on forest data to identify the detailed status of FETT usage at the prefectural level. We focus on the prefectural level because, unlike municipalities, prefectures tend to develop forest information platforms as one of their supporting activities for municipalities.

Falling within the broad concept of payment for ecosystem services (PES) (Ghazoul et al. Citation2009; Wunder and Wertz-Kanounnikoff Citation2009; Redford and Adams Citation2009; Ingram et al. Citation2014), FETT can be interpreted as a PES scheme (Uchiyama and Kohsaka Citation2016), i.e. as an environmental tax scheme (He and Zhang Citation2018). PES schemes for forest management are gaining salience in the international arena (Alix-Garcia and Wolff Citation2014; Davies et al. Citation2017). One such example is REDD+ (Ehara et al. Citation2014). As with many other PES schemes, FETT is linked with inputs (forest areas, employees etc.) (input-based payments) rather than quality outputs (output-based payments). Given these characteristics of FETT, the present study can contribute to research on PES utilization in the context of forest management. As for taxpayer perceptions and the theoretical basis of the tax and related PES schemes, existing studies have focused on public perceptions (Obeng and Aguilar Citation2018; Lin et al. Citation2021), tax payment responsibility (Wakiyama et al. Citation2021), and theoretical basis of such taxation (Chen and Tanaka Citation2007; Nakayama et al. Citation2019). Although this study’s results are not directly related to perception-based studies, they can be shared with stakeholders, including taxpayers, and future research can then analyze their perceptions after they have understood the tax use.

2. Methodology

2.1. Questionnaire survey and analysis of budget allocation

The research framework consisted of two components: (1) a questionnaire survey comprising both qualitative and quantitative data, and (2) quantitative analysis of the correlation between forest data development budgets and prefectural characteristics.

The first datasets were obtained through a questionnaire survey. The respondents were officers in the 47 individual prefectures (face-to-face interviews were conducted for all prefectures in FY 2019, as in the study by Kohsaka and Uchiyama (Citation2021), but were avoided due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021). The officers were in charge of FETT at the national level and the prefectural-level forest environmental tax (PreFET). All 47 prefectural offices sent back their answers. For the 37 prefectures which have implemented PreFET, responses were received from two officers (i.e. one each from those in charge of PreFET and FETT). For the other prefectures, officers in charge of FETT answered the questionnaire. The survey was designed to investigate the status of forest data development using transfer taxes and prefectural environmental taxes. It asked questions about: (1) the status of LiDAR forest data and their maintenance, (2) types of data managed by the prefectures, (3) where data were stored, (4) extent of forest data disclosure (in order to understand the progress of information sharing), (5) divisions between prefectures and municipalities in the development of forest data, and (6) amount of budget from transfer tax and prefectural environmental tax in forest data development. Questions (1) to (4) were multiple choice (with the possibility to provide additional comments in writing); exact numbers were requested for (5) and (6). The questionnaires were distributed in February 2021 and collected between April and June 2021.

The correlation between prefectural characteristics and forest data development budgets were examined, to identify factors that influence the size of these budgets (including transfer taxes). The following variables were examined: (1) the forest data development budget in 2020, (2) the number of words related to forest data in assembly minutes, (3) the number of municipalities under prefectural control, (4) total forest area, (5) area of private planted forest, (6) proportion of private to non-private forests, and (7) timber production output.

In order to calculate the number of words related to forest data in assembly minutes, we compiled all the statements mentioning FETT or NFMS in the minutes of the official assembly of each prefecture. We then simply counted data-related words appearing in the same sentences to capture overall trends and understand whether there were any prefecture-specific characteristics of discussions on forest data development. Data-related words were counted from the minutes of both regular plenary meetings and specific relevant committees (generally committees related to agriculture and forestry) from 2017 to 2020.

2.2. Forest information managed by prefectures and other official bodies

There have been efforts to legally integrate ownership information into forest information systems based on the Forest Land Registry System (FLRS or Rinchi-Daicho) (), established with the amendment of the Forest Act in 2016 and operationalized in April 2019. However, various types of information are not streamlined or are incompatible with different systems, resulting in discrepancies or incompatibility among cadastral maps, registries, and ownership data, which are managed by different ministries. Information related to local residents’ forest ownership has been collected in the fixed asset register (FAR or Kotei-Shisan-Daicho) for decades. The FAR is not easily accessible, even to official bodies, because information disclosure was restricted to taxation purposes. Information from the FAR became available for forest management in 2020 following an amendment to the Forest Act. Due to these legal requirements, the use of forest owners’ personal information in FAR for non-tax purposes was strictly limited to cases where it was necessary for the enforcement of the Forest Act. In March 2020, The Basic Act for Land was amended, and the responsibilities of landowners regarding the proper use and management of land were clarified, including efforts and procedures to clarify rights and boundaries. In addition to these legal changes, land registry surveys are conducted through the implementation of related government ordinances (e.g. revision of the Enforcement Order of the National Land Survey Act). The aim of these amendments to laws and government ordinances is to contribute to improving the integration of ownership information and forest data. However, the municipal-level shortage of forest management human and financial resources, responsible for the maintenance of forest land registers, represents a practical structural challenge.

Table 2. Information on the forest land register and its information sources and information management and maintenance entities.

3. Results

The results of the survey analysis are described below. Specifically, the answers to questions (1) to (6) and analysis of correlations between budget size and influential factors are provided in the following subsections.

3.1. Status of LiDAR data development

The extent of LiDAR data in all individual prefectures was captured. LiDAR data enables us to gain detailed forest-related data, including tree heights, on an individual basis. However, questionnaire responses revealed that the needs for these data varied depending on the contexts of individual prefectures. Consequently, the priority of LiDAR data development and usage in budget plans varied across prefectures, especially because the maintenance of higher resolution data requires additional costs.

In addition to the FETT scheme, certain prefectures were endowed with data from national organizations such as the Forestry Agency. These included, for example, four prefectures (Hiroshima, Okayama, Ehime, and Kochi) that were affected by natural disasters, including landslides and heavy rains (namely the Nishi-Nippon Gou or 2018 Heavy Rain Disaster in western Japan). In such cases, the development of such data was not included as expenditure on the FETT.

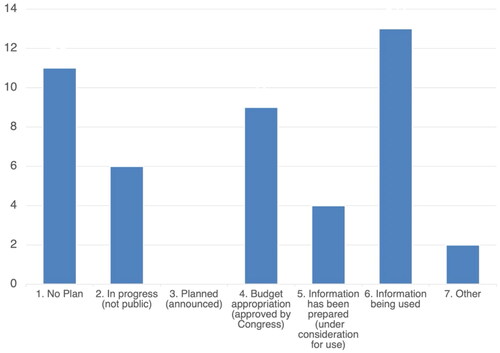

The number of prefectures at different development stages are shown in . The majority of prefectures were in the process of developing plans, some of which are yet to be released. This was followed by prefectures which had already developed plans and were using the data. More than 70% of all the prefectures were either utilizing data or developing plans; thus, the majority of prefectures already utilized LiDAR data or planned to do so in the near future. At the time of the survey, only 11 prefectures had no plans. In these cases, data acquired from national organizations such as the Forestry Agency and Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) could be utilized. In this respect, the absence of a plan did not always imply a lack of data or intent to use it.

The spatial resolution of the LiDAR data to be developed and utilized was related to the intended information use; for example, if users (municipalities in case of the FETT) needed to estimate available resources or topographical information. For example, it is difficult to detect the shape of individual trees with low-spatial-resolution data, making a detailed estimation of forest resources from such data impossible. Our data could not reveal whether such estimations of resources were in progress, given that data resolution was not surveyed. Thus, the survey results showed whether activities were implemented, planned, or absent, though they did not show the detailed purpose for developing and utilizing LiDAR data.

Nonetheless, we were able to understand the general trends and circumstances of forest data development in the prefectures. The 13 prefectures that were already using these data were expected to share their experiences and know-how with other prefectures that planned to use the data in the future, thereby promoting cooperation among prefectures and beyond prefectural boundaries. Forest data sharing between prefectures and municipalities was also needed. Prefectures lacking LiDAR data were unable to develop forest data, and therefore tended to postpone or avoid data development and usage until the effects of such activities were clearly identified (i.e. by observing other prefectures’ efforts). Officers in charge of prefectures without data development plans mentioned that such plans had not been prioritized as their effects remained unclear. Thus, in addition to know-how around data development and its use, the effect of data use needs to be verified in prefectures that have utilized these data.

3.2. Types of data managed by prefectures

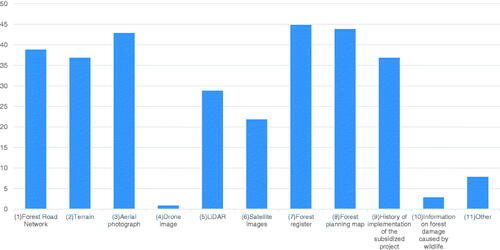

The results of the question about forest data types could be classified into 10 major types (). Among the 10 types, aerial photographs, forest road networks, topography, and histories of forest management operations were primarily managed by the prefectures.

In particular, aerial photographs are managed by 43 prefectures and are widely used as the basis of forest data. Alternatively, LiDAR and satellite imagery are limited to roughly half of the prefectures: 29 for LiDAR and 22 for satellite imagery. Since both LiDAR and satellite imagery data are technical and can be outsourced to external bodies (such as consulting research companies), it can be assumed that some prefectures use such data but do not directly manage the data themselves. Research institutes and forestry companies frequently use drones to capture images of forests in areas that are difficult to assess on foot. Prefectures may be able to manage drone images in the future by collaborating with these institutes and companies. In fiscal year 2020, the time of the survey, there was only one prefecture who managed drone images independently.

Information on forest damage caused by wildlife (such as deer, wild boars, bears, monkeys, and other animals) was managed in three prefectures. Importantly, this low number does not imply that prefectures were not prioritizing such information, which may have been controlled by other departments. This is because data management activities could be financed by FETT, PreFET or other department budgets; consequently, data management activities may have been implemented by other departments (i.e. agriculture/environment departments) rather than by forestry-related departments. In large-scale areas, certain PreFETs were utilized as a financial resource for habitat management (Kishioka et al. Citation2022). In such cases, information on forest damage caused by wildlife was expected to be an integral part of forest data. Alternatively, there were exceptional prefectures (in islands or urban areas) where the risk of forest damage caused by wildlife was low or unidentified. In these prefectures, managing related information was a low priority.

3.3. Data storage location and availability of forest information

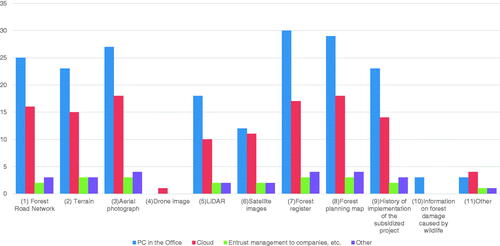

This section describes the storage location of the forest data types discussed in the previous section. The results suggest that the majority of data were stored on computers at prefectural government offices, and that storage location did not depend on information type ().

Regarding satellite imagery, the information was generally managed directly by each prefecture using computers in their offices and/or cloud systems. Three prefectures stored datasets both on their cloud servers and local computers. The number of prefectures that managed satellite imagery on local computers in their offices was approximately equal to the number storing data on cloud servers. There were a limited number of cases in which data storage was outsourced to private companies or other institutions.

These trends possibly relate to privacy laws and data protection concerns. Most forest data managed by prefectures was directly related to the assets of forest owners, and was thus regarded as personal information. Data relating to forest damage caused by wildlife was stored exclusively in computers under prefectural supervision.

As for data accessibility, basic data, such as topographical information and aerial photographs, are increasingly being made available to the public by research institutes or related organizations. Thus, it is possible that the need for prefectures to manage such data will diminish in the future. However, specific forest data, including basic information, still tends to be managed directly by prefectures.

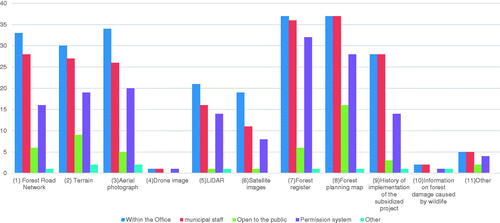

shows the levels of disclosure of forest information, depending on the prefecture and data type. In principle, information is shared within prefectural offices and with municipal employees; certain information is available to the public or can be accessed if permission is obtained. Accordingly, permission systems have been introduced in certain prefectures, allowing access to forest registration-related information. Forest planning maps tend to be the most open to the public; 16 such prefecture-level maps are available.

Alternatively, LiDAR data, satellite imagery, and information on the past operation records of subsidized projects (such as thinning areas) were available for a limited number of prefectures. A possible explanation for this is cost, as LiDAR and satellite imagery have large data volumes and therefore the cost of making them publicly available is relatively high, though sharing data with external parties is possible on a permission basis. A permission system was applied for accessing operation records of subsidized projects because it contained personal information related to owners (depending on the resolution of the information). This trend—i.e. establishing permission systems—was also observed for forest registration data. To avoid risks related to unrestricted disclosure, each application was examined before a decision was made on whether to make the information public. At 28 prefectures, the past operation records of subsidized projects were shared exclusively within prefectures and with municipal employees.

Damages caused by climate change-related disasters such as heavy rains, typhoons, and landslides are becoming increasingly severe, and so related information is also growing in size and importance. The relevant topographical information, including forest data, must be widely shared and used in an integrated manner (as mentioned in the case of the 2018 Heavy Rain Disaster in western Japan). Information shared beyond prefectural boundaries can be instrumental in improving the understanding of disaster risks. To address these risks, the scope and process of information sharing, including permission systems, may need to be changed in the future.

3.4. Collaboration between prefectures and municipalities

This subsection describes the status of collaboration between prefectures and municipalities in the maintenance of forest data. As pointed out in the introduction, the majority of municipalities need support from prefectures regarding forest management and policy making due to their limited capacities and human resources. Individual municipalities aiming to introduce NFMS are responsible for updating and maintaining forest data, including ownership data.

Nineteen of the 47 prefectures explicitly mentioned “organizing forest ownership data” and “maintenance of forest data” as the types of support they provided to municipalities. The majority of prefectures indicated that the municipalities were responsible for maintaining and updating FLRS and collecting information on forest owners. Given the large number of unknown forest owners, these responsibilities created a large burden for municipalities. FLRS was facilitated by the Forest Act and other related ordinances. However, the budget and human resource constraints of municipalities remained a serious issue. Moreover, finding forest owners and detecting forest boundaries were becoming more challenging due to rapid depopulation and aging in rural areas.

In addition to the information flow from prefectures to municipalities, several municipalities provided forest information to the prefectures, including updated information and results of forest resource analysis using LiDAR data. In principle, the prefectures focused on broader areas based on data with possibly coarse resolution, while the municipalities focused on more accurate and detailed resolution when required. The areas that required highly accurate data depended on the municipality’s characteristics. Areas with relatively clear land tenures frequently enabled easier operations. Certain municipalities needed to identify the districts that required accurate data, which they then verified LiDAR or related data. By obtaining accurate data for areas that needed such data, such as forest boundaries and the amount of forest resources, this division of duties further facilitated the development and maintenance of forest data.

In summary, understanding the specific kinds of information exchanged between prefectures and municipalities is essential. However, specific analysis of actual situations, such as the frequency of communication between municipalities and prefectures, is not covered in this paper and remains a future research task.

3.5. Budget allocation and prefectural characteristics

The average budget allocated for forest data maintenance and development was 77 million JPY; 33 million JPY of the average budget was financed by FETT. This means that the FETT often served as a main source of funding for forest data development at the prefectural level. Nonetheless, budgets for forest data development varied widely, from a minimum of 2 million JPY to a maximum of 264 million JPY. The largest and smallest budget proportions financed by FETT were 209 and 2 million JPY, respectively.

The budget required for forest data development can fluctuate during development. Thus, the detailed process should be clarified in future research to understand such fluctuations in detail. In addition, certain prefectures may use data provided by national organizations, such as the Forestry Agency. Therefore, the progress of forest data development needs to be examined using multiple types of evidence, including budget size. Considering these circumstances, this study showed that the FETT can contribute to the development of forest data in prefectures in terms of securing budgets.

The results of the correlation analysis showed that the number of statements about forest information in the prefectural assemblies was correlated with the budget size for know-how sharing and instruction (). Alternatively, the budget for forest data development (FETT budget) was significantly correlated with the percentage of private forest plantations in prefectures (i.e. the ratio of private to non-private forests, rather than their absolute size, was critical). This implied that the budget size for forest data development could be influenced by the political or social weight of private forest plantations in individual prefectures.

Table 3. Correlations between budget size and prefectural characteristics and frequency of appearance of related words in the discussions in prefectural assemblies.

We further analyzed the variables using the FETT budget size (a variable used to compute the allocated budget size of FETT), and the results indicated a significant correlation between the total allocated FETT budget and private forest plantation area. This result confirmed the criteria for computation of the budget size of FETT. The correlation between the total budget for forest data development and the FETT-financed budget suggested that the overall trend in budget use for data development could be influenced by FETT. Prefectures that had earmarked funds to develop forest data tended to use the FETT budget to do so.

The total FETT budget size correlated with the FETT budget for growing successors and providing forest management education, suggesting that prefectures with a larger FETT budget tended to use it for these purposes. Because the needs for forest data development differed among prefectures, several prefectures with high FETT budgets did not use it for data development. Moreover, the total budget size of FETT was not significantly correlated with the FETT budget for data development.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The overall focus of the FETT at the prefectural level is shifting from basic administrative support in terms of identifying owners or explaining new systems such as NFMS, toward forest data sharing. In this study, the use of FETT related to forest data development, inter alia, was identified. The proportion of the FETT budget in the total budget for forest data development is significant, thus the FETT contributes to the facilitation of data development, including obtaining and utilizing LiDAR data. This responds to the need for building consistent forest-related databases using remote sensing data, which is an urgent task beyond the national context of Japan (Park et al. Citation2022). The data managed by prefectures differ according to type. As for accessibility, information containing personal information of forest owners was not open to the public, but was partially available through permission systems. Prefectures and municipalities needed to collaborate when managing forest data. Several prefectures are not only developing and managing such data in a top-down manner, but are also organizing data provided by municipalities, such as LiDAR data, in a collaborative manner. Such collaborations are desirable if FETT budgets are to be effectively used. A sense of collaboration between urban and rural residents can also be generated through the implementation of FETT and PreFET (Ishizaki and Matsuda Citation2021); these systems can enhance urban taxpayers’ awareness of various values related to forests and forest management. Forest management can be sustainably implemented based on collaborations between upstream forest management rural areas and downstream urban areas where beneficiaries of forest management reside. Understanding the perceptions of different actors, including urban residents, regarding forest-related values can be useful for the future development and maintenance of forest data and forest management in general (Jang-Hwan et al. Citation2020); it can also be a first step for consensus building on tax usage.

The results of the correlation analysis between budget size for forest data development and prefectural characteristics suggest that the proportion of private artificial forests, rather than absolute areas, is the key variable. In particular, the total budget and FETT budget for forest data development are relatively high for prefectures with large proportions of private forests. This implies that the absolute size of such forestlands might not be a matter of concern, but the proportion of private forest plantations carries political and social weight and could be a critical factor in allocating forest data development budgets. Future analysis is needed to verify the hypothesis (i.e. that the political or social weight of ecosystems, such as forests, have a key role in budget allocation) which was derived from this study; this would enable researchers to identify the key influencing factors in trends and patterns of budget allocations for specific purposes in environmental management under PES schemes. Takahashi and Tanaka (Citation2021) analyzed the conditions of introducing and developing forest environmental tax schemes and found that ecosystem services such as services for drought and landslide risks reduction can be considered to develop tax schemes in the form of PES. Considering such studies on tax and ecosystem services, the correlation between the status of ecosystem services and tax usage should be analyzed in future research to provide insights into the influencing factors for tax revenue budget allocations in forest management. This research provided a basis for the future analysis of FETT as a PES scheme, its budget allocation, and effects of forest data utilization. After the phase of forest data development, prefectures will need to use it, and verifying the effects of forest data use will be a future task. The environmental contexts of prefectures might influence on such phases too. The analytical framework of the influence of the contexts, which was provided by this research, can contribute to analysis of future phases of FETT and its effects produced by related policies and forest data use supported by FETT.

Note

In the overall framework of the strategy, the focus on forestry is minor compared to the attention paid to agricultural components, such as the extent of organic agriculture, its application, and the development of environmental technology. There is one segment relating to smart forestry, including applications of forest cloud and ICT production management systems in order to promote forestry with fewer human resources; this includes a concrete schedule for the introduction of these systems. The forest cloud literally refers to a system that manages or stores forest information on a cloud system. This information is currently stored in the local computers of governments, including prefectures and municipalities, as well as forest cooperatives or other private entities. The stored data are designed to have GIS functions and the ability to manage attributes combined with layers on the maps. In the MeaDRI, FY2021 was set as a target for the introduction of forest cloud systems across all prefectures. Interface and exchangeability are being promoted among prefectures and businesses with standard specifications to further facilitate the use of forest cloud data in the subsequent period. The standard specifications for the ICT production management system are due to be prepared by FY2021, and in the following period the aim is to encourage the introduction of this system in compliance with the standard specifications. The introduction of “elite trees” with excellent and relatively short-term growth potential and high-performance forestry machines are the main forestry-related elements.

These changes in forestry management are part of the broader promotion of ICT in Japan, for which the concept of “Society 5.0.” has been coined. The real physical world and digitalized world are seamlessly transformed and merged in the conceptualized Society 5.0, which was introduced and adopted in Japan’s five-year Science, Technology and Innovation Basic Plan. This revision of science and technology-related laws in 2020 was the first in 25 years. As a symbolic change, the name of the law changed from the Basic Act on Science and Technology to the Basic Act on Science, Technology, and Innovation. Consequently, the 6th Science, Technology, and Innovation Basic Plan has been implemented (Cabinet Office Citation2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alix-Garcia J, Wolff H. 2014. Payment for ecosystem services from forests. Annu Rev Resour Econ. 6(1):361–380.

- Cabinet Office. 2021. The 6th Science, Technology, and Innovation Basic Plan (in Japanese). [accessed 2021 October 10]. https://www8.cao.go.jp/cstp/kihonkeikaku/6honbun.pdf.

- Chen Y, Tanaka K. 2007. Maintenance of local forest environment by a prefectural tax toward theoretical basis of local forest environment tax. Jpn J Real Estate Sci. 21(1):116–126.

- Davies HJ, Doick KJ, Hudson MD, Schreckenberg K. 2017. Challenges for tree officers to enhance the provision of regulating ecosystem services from urban forests. Environ Res. 156:97–107.

- Ehara M, Hyakumura K, Yokota Y. 2014. REDD+ initiatives for safeguarding biodiversity and ecosystem services: harmonizing sets of standards for national application. J For Res. 19(5):427–436.

- Forestry Agency. 2021. Forest and forestry basic plan (in Japanese). [accessed 2021 October 12]. https://www.rinya.maff.go.jp/j/kikaku/plan/attach/pdf/index-4.pdf.

- Ghazoul J, Garcia C, Kushalappa CG. 2009. Landscape labelling: a concept for next-generation payment for ecosystem service schemes. For Ecol Manage. 258(9):1889–1895.

- He P, Zhang B. 2018. Environmental tax, polluting plants’ strategies and effectiveness: evidence from China. J Pol Anal Manage. 37(3):493–520.

- Ingram JC, Wilkie D, Clements T, McNab RB, Nelson F, Baur EH, Sachedina HT, Peterson DD, Foley CAH. 2014. Evidence of payments for ecosystem services as a mechanism for supporting biodiversity conservation and rural livelihoods. Ecosyst Serv. 7:10–21.

- Ishizaki R. 2019. Benefits and burdens of forest environment tax. Environ Inf Sci. 48(1):43–48 (in Japanese).

- Ishizaki R, Matsuda S. 2021. Message for solidarity: a Japanese perspective on the payment for forest ecosystem services developed over centuries of history. Sustainability. 13(22):12846.

- Jang-Hwan J, So-Hee P, JaChoon K, Taewoo R, Lim EM, Yeo-Chang Y. 2020. Preferences for ecosystem services provided by urban forests in South Korea. For Sci Technol. 16(2):86–103.

- Kajima S, Uchiyama Y, Kohsaka R. 2020. Private forest landowners’ awareness of forest boundaries: case study in Japan. J For Res. 25(5):299–307.

- Kishioka T, Uchiyama Y, Kohsaka R. 2022. Status and trends of forest environmental tax for wildlife management in japanese prefectures. J. Jpn. For. Soc. 104(4). (in Japanese).

- Kohsaka R. 2021. Integrated knowledge for policies on science, technology, innovation, and consensus building: is upgrade of society possible?. In: Mizuno K, editor. Future direction of economy, Soseisha Co., Ltd (in Japanese).

- Kohsaka R, Kohyama S. 2022. State of the art review on land-use policy: changes in forests, agricultural lands and renewable energy of Japan. Land. 11(5):624.

- Kohsaka R, Osawa T, Uchiyama Y. 2020. Forest environment transfer tax and urban-rural collaboration: case of Chichibu City and Toshima District in Japan. J Jpn for Soc. 102(2):127–132 (in Japanese).

- Kohsaka R, Uchiyama Y. 2019. Forest environmental taxes at multi-layer national and prefectural levels: comparisons of 37 prefectures survey results in Japan. J Jpn for Soc. 101(5):246–252 (in Japanese).

- Kohsaka R, Uchiyama Y. 2021. Forest environment transfer tax, prefectural forest policy, and support for municipalities. J Jpn for Soc. 103(2):134–144 (in Japanese).

- Lin JC, Chiou CR, Chan WH, Wu MS. 2021. Public perception of forest ecosystem services in Taiwan. J For Res. 26(5): 344-350.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan. 2021. The strategy for sustainable food systems, MeaDRI (in Japanese). [accessed 2021 October 12]. https://www.maff.go.jp/j/kanbo/kankyo/seisaku/midori/attach/pdf/index-7.pdf.

- Miyake Y, Kimoto S, Uchiyama Y, Kohsaka R. 2022. Income change and inter-farmer relations through conservation agriculture in Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan: empirical analysis of economic and behavioral factors. Land. 11(2):245.

- Nakayama K, Shirai M, Yamada M. 2019. Effects of environmental taxes on forest conservation: case of the water resources conservation fund in Toyota City. In: Keiko Nakayama and Yuzuru Miyata (eds.), Theoretical and empirical analysis in environmental economics. Singapore: Springer; p. 49–67.

- Obeng EA, Aguilar FX. 2018. Value orientation and payment for ecosystem services: perceived detrimental consequences lead to willingness-to-pay for ecosystem services. J Environ Manage. 206:458–471.

- Park JM, Lee YK, Lee JS. 2022. A comparative analysis of forest area differences between statistics information and spatial thematic maps. For Sci Technol. 18(2):76–85.

- Redford KH, Adams WM. 2009. Payment for ecosystem services and the challenge of saving nature. Conserv Biol. 23(4):785–787.

- Suzuki H, Kakizawa H, Hirata K, Tamura N. 2020. The current state of and future trends in the forest administration of municipalities: analysis of the postal questionnaire survey. J For Econ. 66:51–60 (in Japanese).

- Takahashi T, Tanaka K. 2021. Models explaining the levels of forest environmental taxes and other PES schemes in Japan. Forests. 12(6):685.

- Teraoka Y. 2020. ICT for regional forestry strategy, series of forestry improvement 195, association of forestry improvement (in Japanese). p. 134. Tokyo, Japan: Association of Forestry Improvement.

- Uchiyama Y, Kohsaka R. 2016. Analysis of the distribution of forest management areas by the forest environmental tax in Ishikawa prefecture, Japan. Int J For Res. 2016:1–8.

- Wakiyama T, Lenzen M, Kadoya T, Takeuchi Y, Nansai K. 2021. Forest tax payment responsibility from the forest service footprint perspective. Environ Sci Technol. 55(5):3165–3174.

- Wunder S, Wertz-Kanounnikoff S. 2009. Payments for ecosystem services: a new way of conserving biodiversity in forests. J Sustain For. 28(3-5):576–596.