ABSTRACT

This paper assesses the risk implications of Brexit for UK-based, manufacturers, drawing on data generated from semi-structured interviews with senior managers and directors in the advanced manufacturing sector of the West Midlands region of the UK in 2021. The UK’s departure from the EU has led to increased socio-economic risk for manufacturing businesses, requiring careful management by the latter. This paper draws on elements of the Kasperson et al. [1988. The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis, 8(2), 177–187] Social Amplification of Risk Framework (SARF) to explore the communication of risk and uncertainty to businesses, during and post-Brexit discussions. This paper then examines the extent to which risk arises from changes to supply chains and production regimes and in turn examines consequences for the management of risk.

Introduction

At the end of 2020, the UK left the EU’s Single Market and Customs Union. Coming more than four years after a narrow (51.9%) majority voted to leave the EU, it is fair to say that the Brexit process has been more complex and convoluted than many had initially envisaged. Moreover, 2020 saw the emergence and spread of Covid-19, the worst pandemic the world has seen in a century, with some 6.12 million deaths to date (end of March 2022) globally and 164,000 deaths in the UK.Footnote1 Governments around the world had to impose dramatic measures to arrest or contain the spread of a novel coronavirus. Both of these events have entailed substantial risks to the operations of business, not least in terms of financial risk, operational risk and people risk. It could also be argued that the responses of governments to Covid-19, as well as the UK Government’s pursuit of a ‘hard’ form of Brexit via a thin Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), entailed a substantial degree of political and regulatory risk to business.

However, in this paper we focus on the impacts of Brexit on business and the communication and experience of risk thereof, utilising elements of the Social Amplification of Risk (SARF) framework developed by Kasperson et al. (Citation1988). In contrast to Covid-19, which represented a vast exogenous shock to all economies, albeit with local and regional impacts (Bailey et al., Citation2020), Brexit in the UK was the outcome of a deliberate policy choice after a Referendum. In so far that it took four years to ‘deliver’ – from the initial referendum outcome in June 2016, to exiting the EU Single Market and Customs Union on January 1st 2021 – Brexit should be seen as a process rather than an event (Bailey & Rajic, Citation2022). Indeed, in so far as the risk ramifications to business are still unfolding as the new trading relationship embeds itself, it could be strongly argued that Brexit (in contrast to the claims of the current UK Prime Minister and leading Leave advocate, Boris Johnson) is not ‘done’, but will rather play out over the long term in its economic and business impacts. This is likely to be particularly the case in manufacturing as firms rejig value chains over time in the wake of increased (non-tariff) trade friction.

As such, the implications for risk management in affected businesses were profound, given the emergence of new non-tariff barriers to trade between Great Britain (GB), Northern Ireland (NI) and the EU in the form of customs, new and extended Sanitary and Phyto-sanitary Standards (SPS) checks and other checks on the movement of goods, as well as the end of freedom of movement of people. As the region in the UK with one of the highest proportions of manufacturing employment in the UK, the Midlands region was and is particularly exposed to these shifts. At present, the question of how the region’s manufacturers are coping and how the situation is likely to evolve in the coming months and years remains open. Whilst there a growing body of academic literature investigating the risks of Brexit in raising supply chain uncertainties for UK-based manufacturers and its impact on their corporate strategy and operations (e.g. Bailey & De Propris, Citation2017; Bailey, Driffield, & Kispeter, Citation2019; Chen et al., Citation2017; Li et al., Citation2019; Liu, Day, Godsell, & Zhang, Citation2020; Moradlou, Fratocchi, Skipworth, & Ghadge, Citation2021; Pournader, Kach, & Talluri, Citation2020; Roscoe, Skipworth, Aktas, & Habib, Citation2020; UKICE, Citation2021), there has been limited understanding at the industry level of the longer-term implications of these shifts as their risk implications unfold over time.

The prolonged timeline of withdrawal from the EU has led to risk mitigation strategies and techniques based on implicit and explicit (risk) communication. Various stakeholders, networks and government departmentsFootnote2 (see) have communicated information about Brexit to businesses, institutions, individuals and society. Given the long period of uncertainty over the precise terms of the UK’s trading relationship with the EU after the end of the transition period, it is important to understand the key sources of communication to organisations as well as the impact that these have had on organisations dealing with post-Brexit changes. In this sense, it is important to understand the way in which ‘communication’ has shaped the interpretation, and indeed amplification or dampening, of risks to supply chains and subsequently how those risksFootnote3 were and are managed in the UK. This paper seeks to consider the implications of risk communication, pre- and post-Brexit, on mitigating and managing risk to manufacturing supply chains.

Conceptualising Brexit and the social amplification of risk

Manufacturing supply chains across the EU have become more interwoven and complex over time (especially since the creation of the Single Market – Bailey & De Propris, Citation2017; Bailey & Rajic, Citation2022). As a result, they were always likely to be subject to a degree of disruption from Brexit (as the Chancellor Rishi Sunak has recently acknowledgedFootnote4), resulting in the challenging tasks of managing risk in supply chains (Alicke & Strigel, Citation2020). Powerful economic forces have been changing the trade landscape (Pournader et al., Citation2020), intensifying supply chain risks. The uncertainty surrounding risks, where the rules of the game are changing (such as from regulatory changes, increased costs with new tariffs being imposed with little notice and delays to import/export), has and is resulting in companies needing to improve their supply-chain risk management capabilities and examining supply-chain resilience. That is what Fiksel (Citation2006) refers to as their capacity to survive, adapt and grow in response to turbulent change. Here, the resilience of companies is significantly affected by customers’ and suppliers’ ability to anticipate and respond to the disruptions associated with Brexit (Pettit, Croxton, & Fiksel, Citation2019). However, resilience can also be a source for strategic advantage, whereby strengthening the resilience of their supply chains can impact positively on their business performance and enable them to better compete with others.

On this, there is increasing recognition of the need for companies to reassess their supply-chain strategies to make them more resilient to any kind of disruption. International businesses need to manage these risks and to prepare their supply chains accordingly. By developing and evaluating scenarios with different probabilities for pre-identified risks, companies can make high-level impact calculations. This applies to a range of firms. Firms of different sizes need to formulate and implement strategies to respond and manage their supply chain uncertainty created by Brexit. For example, Roscoe et al. (Citation2020) found that when formulating strategy, multinational organisations (MNEs) used worst-case assumptions, whilst large firms, and small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) gathered knowledge as part of a ‘wait-and-see’ strategy.Footnote5 Such strategies then allowed them to reduce perceptions of heightened supply chain uncertainty. This research suggests that firms then implemented reactive and/or proactive strategies to mitigate their supply chain risks.

In this context, risk theory (Aven & Renn, Citation2020; Kasperson et al., Citation1988; Citation2003; Slovic, Citation2000) is a useful lens through which to explore the impact of Brexit as a disruptive event, as it integrates a somewhat technical analysis of risk with the wider cultural, social and institutional responses which shape the experience of risk in response to a risk event. Indeed, large-scale crises and global events (e.g. the Global Financial Crisis 2008; Covid-19) are rarely confined to the technical assessment of risk, and an increased recognition exists of the wider conceptualisation of risk factors with direct and indirect negative impact. In this vein, Slovic and Weber (Citation2002) argue that the more unknown a risk is, the more likely it is to be amplified leading to an unbalanced risks analysis. Regarding Brexit, as an unprecedented event, this observation was significant due to the lack of past information and knowledge surrounding the relatively new phenomenon of economic dis-integration (Lawless & Morgenroth, Citation2019). That created complexity in the management of risk, particularly so in the political context of Brexit. Given such complexity, the ‘Social Amplification of Risk Framework’ (SARF) can provide a useful frame to examine the risk event (Brexit) and its characteristics, including the range and type of risk impact upon organisations within the UK. In so doing, it reinforces the need for organisations to understand and conceptualise Brexit’s associated risks, their probability, impact, subsequent communication and mitigation.

Risk research traditionally focused on technical approaches to risk analysis. As the risk discipline has evolved, attention has broadened to consider the social dimension and the wider appreciation of risk perception as part of the assessment process (Aven & Renn, Citation2020; Renn & Levine, Citation1991; Slovic, Citation2000). As Klinke and Renn (Citation2014) point out, effective communication has to be at the core of any successful activity to assess and manage risk. Analysis of previous crises and events has indicated that the level and source of exposure to information can lead to better knowledge and protective behaviours (Allen, Citation2018; Winters et al., Citation2018). At the same time, it can also encourage misconception and risky behaviours. This signifies the importance of effective risk communication as a risk mitigation and resilience strategy in protecting institutions and communities from the severity of an event. Communicating such information to businesses and organisations is important, as it could lead to different perceptions and understanding of risks presented and so contribute to the analysis of risk – particularly so in the implicit, non-formalised communication of Brexit.

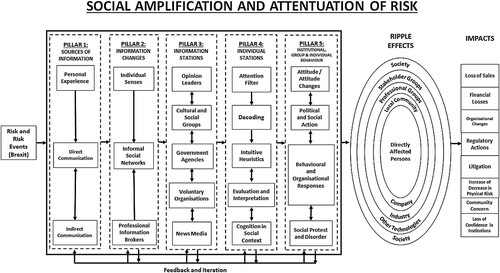

As such, consideration should be given to the ways in which risks have been communicated, perceived and subsequently amplified, or indeed lessened, during Brexit. Fundamental to the SARF approach, is that communications of risk events permeate through transitional stations (see ); this assists in the amplification or attenuation of perceptions of risk. Each pillar (1–5) in the communication chain, for example, individuals, groups, and media, contain filters through which information is sorted and understood (Kasperson et al., Citation1988, Citation2003). Various amplification systems (sources of information), include both formal and informal outlets such as the government, media, social organisations, think tanks, trade bodies and opinion leaders (Kasperson et al., Citation1988, Citation2003). The fourth pillar focuses on the individual stations (i.e. in heuristics, decoding, interpretation) with the ability to change the way in which risks are perceived. The fifth pillar moves towards institutional, group, and individual behaviour considering group perceptions of risk information. Critical to the SARF approach is the sourcing and distribution of information surrounding the risk event which ultimately determines both group and individual perceptions about the severity or magnitude of the risk based in the 5 pillars of social amplification (Jardine, Boerner, Boyd, Driedger, & Cowling, Citation2015; Kasperson et al., Citation1988, Citation2003; Siegrist & Zingg, Citation2014). The communication of Brexit information to business leaders, and so risk and uncertainty, can lead to varying responses in the balancing of risk analysis and estimation of risk impact across different types of industry. Risk experience is defined through the interaction between potential harms (extra costs, loss of business, sales, etc.) attached to a risk event (Brexit) and the social and cultural processes (dissemination and interpretation of information, individual experiences, institutional cultures) which shape the interpretation of that event (Brexit).

Figure 1. The social amplification of risk framework (adapted from Kasperson et al., Citation1988).

The ways in which organisations respond to potential amplifications of risk can lead to a ‘ripple effect’ (see ) with quite severe consequences of impact upon business operations and wider communities (Kasperson et al., Citation1988). This ripple effect can extend to other groups (professional bodies, trade unions, trade groups) and can lead to (business) impact in the form of litigation, financial loss, extra costs, loss of business, organisational changes and the loss of confidence (see ). In risk analysis, the tertiary and secondary impact on supply chains can include direct and indirect institutional impacts: for example, political and/or social pressures; changes in risk monitoring and regulation cost; and increased liability and insurance costs; as well as an impact on the local economy (see ).

Following the identification, analysis and subsequent impact of risk, it is important to consider the organisational response in managing and mitigating risks appropriately. Consideration must be given to the under- and over-estimation of risk impact, noting the long-term and short-term risk impact on supply chains for example. In managing risk, reference has been made to building organisational resilience as part of the risk management process (Mitchell & Harris, Citation2021; Rød, Lange, Theocharidou, & Pursiainen, Citation2020; Van Der Vegt, Essens, Wahlström, & George, Citation2015) rather than during the recovery process of a crisis (Kovoor-Misra, Citation2019) – in this case during Brexit negotiations and ensuing TCA. In the analysis of risks and subsequent impact of Brexit on business it was important to ensure an efficient and effective strategy in organisations by constructing organisational resilience as part of their policy and risk analysis (BSI, Citation2021; Van Der Vegt et al., Citation2015).

The ‘end-type’ of Brexit impacted upon risk distribution locally and globally, which presents mixed challenges for businesses as economic policy and governance change. The risk implications and impact upon businesses and their capacity to absorb the prevailing risks has been questionable – particularly so given the economic situation post Covid-19. The SARF approach is used here as a conceptual framework to critically explore Brexit, focusing on business – rather than individual, attenuation and amplification of associated risks as part of this paper. A key question then is how prepared were (and are) UK manufacturing firms in managing Brexit? And linked to this, how was risk information being communicated, processed and so managed?

Methodology

Given the focus of the study on how advanced manufacturing businesses perceived the risks arising from Brexit, a case study research strategy was adopted. The underpinning research philosophy was that of a pragmatist approach, enabling the revealing of insights around firms’ responses to Brexit, drawing on both qualitative and quantitative data in a mixed methods approach.

Accordingly, 12 detailed semi-structured interviews of approximately 30–60 min duration were undertaken with senior managers in the automotive, aerospace, medical technologies sectors and attendant suppliers and industrial service providers. These individuals consisted of a mix of functional areas (procurement, operations, finance, etc.) but the key criterion for interview selection was that these people in some sense ‘owned’ the issue of Brexit in their businesses. In conducting the interviews, we specifically sought a mix of respondents across different tiers of the supply chain, ranging from key Vehicle Manufacturers (VMs) through to smaller tier 2 and tier 3 firms. Key summary statistics pertaining to respondents (sector, supply tier, size of the business, etc.) are detailed in .

Table 1. Respondent profiles – key information.

Questions centred on the preparations for Brexit: where information on Brexit was sourced from; what they perceived the ‘worst-case scenario’ from Brexit would be in the lead-up to the signing of the final TCA; supply chain responses to the pandemic; and how they therefore sought to mitigate any risks arising. Interview participants were provided with prior information about the purpose of the research so as to ensure fully-informed consent, and the interviews were conducted in accordance with the strict ethical tenets of voluntary participation, anonymity, confidentiality and non-disclosure where requested. The interviews were recorded online via a secure digital recording platform (MS Teams) and transcribed using the services of a research assistant. Data was kept on secure servers and all personal identifiers were destroyed upon the conclusion of the research.

In the sections that follow, we detail the findings of the research in accordance with the themes denoted above. Given the relatively small size of the interview sample, the findings should be considered as indicative rather than being necessarily representative, so some caution is necessary in terms of generalising the findings.

Findings and key themes

Expectations in the lead-up to a trade agreement

In the lead-up to the signing of the UK-EU TCA, all of our respondents said that they had undertaken scenario planning and considered the risks associated with a No Deal outcome with the imposition of a tariff regime to be the worst-case outcome. This required up to date information to enable the effective identification and assessment of associated risks. Respondents referred to accessing sources of information (see SARF pillar 1) such as (indirect) media accounts and (direct) governmental information underpinning the TCA.

However, preparations for exiting the Single Market and Customs Union had been hampered by what they regard as a lack of transparency and clear information from the Government and civil service (direct information). Even those respondents from businesses that undertook substantial trade outside of the EU (personal experiences), and hence were already familiar with customs checks and the International Commercial Terms (Incoterms) that govern international trade, thought that Brexit would impose additional disruption to them:

The bit I was most worried about was around the uncertainty which drives lack of confidence in terms of buying, forecasting and it was that which was quite damaging for our business over multiple attempts of leaving the EU, and second that we were quite confident that if there was a deal it would be short term to medium term adjustments, not necessarily by us, but more our supply chain and customers that probably will give us the most pain. And all those things came true … (Participant 4).

The communication and experience of risk

‘Brexiters’ have always argued that UK businesses had four years to prepare for Brexit and in a sense the basic objective of a minimal free trade agreement that only eliminated tariffs on UK-EU trade was always evident. However, this reality was obscured in the cut and thrust of negotiations and the UK Government’s stance that ‘no deal is better than a bad deal’Footnote6 meant that for many businesses, it remained unclear (even in December 2020) what the impact of Brexit would be.

For example, amidst Brexit uncertainty, automotive assemblers shut down production on several occasions in the run up to various Brexit deadlines, given concerns over what a ‘No Deal’ scenario might mean for the supply of components and ‘Just in Time’ systems (Bailey, Citation2020). Indeed, auto assemblers including Jaguar Land Rover, Toyota and BMW shut down assembly operations in both April 2019 and October 2019 to avoid disruption around the time of the UK’s scheduled departure dates from the EU. JLR’s then Chief Executive Ralf Speth said the firm had no choice but to stop production lines at its four UK plants (Solihull, Castle Bromwich, Wolverhampton and Halewood), stating that the firm needed 20 million parts a day; every part had to be available when needed and just in time. Firms also stockpiled components (with anywhere between a few days’ and few weeks’ components stored), adding to costs, ‘just in case’.

The latter illustrated the vulnerability of manufacturing (and not just auto) that relies on ‘Just in Time’ (JIT) supply chains to any form of Brexit that could cause customs delays and supply chain disruption. Essentially, customs delays under either a No-Deal Brexit at the end of 2020 or even a ‘bare bones’ Canada style Free Trade Agreement (as in the final TCA) were viewed by auto assemblers as potentially disruptive to the working of JIT systems commonly used across UK and EU manufacturing. While a minimalistic trade deal could eliminate most tariffs, the UK would still be outside the EU Customs Union and there may be customs delays. It should be noted that the UK decided to postpone implementing customs checks on incoming goods until the beginning of 2022 given a lack of preparedness. More broadly, investment in the auto industry in particular stalled amidst Brexit uncertainty over the nature of the future trading relationship with the EU from 2016 to the end of 2021.Footnote7 This was particularly significant given wider shifts in the automotive industry towards electrification, with a feeling that the UK was missing out on potential investment in new technologies amidst Brexit uncertainty. For example, it was noteworthy that Tesla CEO Elon Musk stated that Brexit uncertainty was a factor in the firm’s decision to build its first major European ‘gigafactory’ ear Berlin in Germany rather than the UK (Bailey, Citation2019).

As such, our respondents felt that poor and ambiguous communication from the UK Prime Minister, his Cabinet and elements of the Civil Service, obstructed business preparations in this context:

The UK government said we had to get ready and prepare, but we did not know what we are preparing for – so we prepared for no deal. And had being doing so for 24 months. (Participant 2)

… because we are a second-tier supplier, we very rarely know what the job entails that we're producing. But if you can identify them – some parts to go into automotive sector for example, we can identify those that go to automotive, so we can ‘nail’ that, that particular part down. But many of the others, you just can't imagine what they thought and neither does the company that you're supplying want to tell you either … (Participant 5).

No, not anymore. We used to be members of the [xxxx] Chamber, but we stopped doing that. It was just a sort of same old, same old [generic Brexit preparedness advice] stuff all the time, really, and I just found that it wasn't really giving us any great benefit really (Participant 6).

Well obviously we weren't party to it, and we only see what the media allows us to see. (Participant 5)

A necessary source of risk communication was via news and media channels in seeking information about Brexit policies including legislation and regulation, and associated risks.

… … certainly, my concern is all the good sort of workers’ rights laws that have come in, I read a lot of stories to say that policy at the moment is suggesting that they're probably going to change those or relax them or, you know, more to the benefit of business was quite a step back I would say, even as a businessperson running a business. (Participant 4).

The lateness with which information was communicated to businesses on the final TCA created a significant impact on day-to day- operations:

So, the main problems [as a consequence of Brexit] to date have been, I suppose the first one was the late details of the deal that was done. And actually, in layman's terms, what that meant we had to do, i.e., what declarations needed to be made, where they needed to be made, what changes we needed to make to particular customers, invoices, all of that sort of stuff. We couldn't finalise that until the deal went through, really … … So that's been a bit of a headache that the lateness, you know, shuffling through all the detail and actually making it work in an efficient way. (Participant 4)

Initially, when the referendum went through, we certainly saw a lot of our expatriate EU people get really quite destabilised by it. I don't know. Again, they felt affected or not wanted, I don't know that they didn't take to it very well. So, we had a period of about six months of just trying to settle people down [but] … ..there was very little, you know, that we knew what they knew about their status and what they would be. (Participant 4)

Mitigating risk and increasing resilience

A number of principal risks were identified as being significant as a consequence of Brexit and can be categorised as: operational; financial risk; and regulatory and compliance. Post Brexit, suppliers were and are faced with the task of identifying, analysing and managing risks resulting from final outcomes (the TCA and subsequent introduction of checks on exports and imports).

Operational risks identified included changes to systems and processes, for example to a paper or electronic based system to record:

This is the big issue for us; overnight we have gone from frictionless trade to full export documentation. This is a fundamental change in the system (Participant 1)

People risk related to human error and the inevitability of getting ‘things wrong:

… ..and bear in mind there is going to be mistakes made because anything that is new, there is going to be human error on all sides, even if we are the most prepared and the most conversant in what we are in terms of transacting between us and the EU. There is going to be other people, suppliers, or customers up and down the supply chain making errors, adding compound things to the issue of capacity at the borders. So, those were the things that we thought would most likely happen and they did. (Participant 4)

So, we’ve had a few suppliers, probably five or six, one major supplier in Germany, that basically said they no longer will deliver to us anymore. (Participant 4).

Brexit has not been as much as of a disaster as it could have been but that is partly because of our own preparation and flexibility, and hard work by our logistics planning people. (Participant 1)

The challenge was that we didn’t know exactly what the impacts were, so we actually prepared to what we deemed as the worst-case scenario which was a no-deal Brexit or an exit on WTO terms. (Participant 4)

… we have prepared for all reasonable eventualities of Brexit and had software in place and ready so we could start the year on the right foot. (Participant 1)

Other strategies included changing supply or distribution routes from seaport to airport. This was viewed as a short-term strategy but provided versatility in the ways in which goods can be distributed:

… our customers took the decision not to use port borders and to actually fly stuff for a short period as well, so we had multiple options … .

… years ago, 25% of our cost of sales was metal. It's gone down now, because of what I've done, what we've done in the business is to diversify away just when making castings into casting and machining. So, what we do is add value sales such as dye penetrant testing and all these things to try and get an element servitisation or other revenue flows into the business. So, metal’s now gone down to between 10 and 15%, rather than just 25% … (Participant 9).

So we had very limited business in the middle east they’re now getting on to being in our top 5 customers in Israel … … we’ve got a new automotive customer in China. We’ve got a large existing customer who we’ve restarted buying from again in the US. (Participant 4).

The ongoing uncertainty surrounding Brexit (policies) meant that risk mitigation had an important role to play in building organisational resilience in relation to probable risks. That advanced manufacturing sectors are disproportionately reliant on a small number of very large firms who act as ‘anchors’, and the risks entailed by Brexit have been and will be largely shaped by the strategies of these key operators to ensure organisational and sectoral resilience. In automotive, JLR and Toyota account for around 44% of the factory-gate value of UK automotive output and so any risk mitigation actions for this sector by government going forward must be cognisant of the needs of these firms. Simultaneously, helping firms deal with the extra Non-Tariff Barriers introduced by Brexit – such as customs declarations and documenting rules of origin requirements could be especially useful for smaller firms lower down the supply chain. This could involve training of staff as well as ensuring easy access to support, especially for smaller firms which have struggled with such requirements.

Discussion

The question of how and when to engage in systematic communication and dialogue about risks has long been debated. Drawing on the SARF framework, this paper focused on the first 3 pillars, namely sources of information, information channels and social stations, and the risk event of Brexit. Our findings suggest that key amplification stations for UK manufacturing businesses included the mass media, politicians, government and professional organisations. The ways in which information was disseminated, and by whom, inhibited preparedness for Brexit and so in the longer term the interpretation (amplified or attenuated) of risk was affected. The delay in providing robust and timely Brexit information to UK manufacturing businesses led to issues in their business operations (risks in finance, processing and in meeting regulative and legislative requirements as they emerge).

Firstly, the perceived lack of information directly communicated by Government (pillar 1), led to increased uncertainty and a reliance on indirect sources of information, such as mass media and word of mouth. Secondly, further issues were identified around information being unclear, and official sources being less helpful and supportive than others, including a lack of accurate real-time data. For example, our findings suggest that manufacturing businesses noted feeling underprepared due to the uncertainty around new policy implementation in trade and border controls, new systems for recording, a lack of clarity around employment for EU nationals and compliance with settlement policies. This is in addition to staff and driver shortages owing to a combination of Covid and EU workers returning home (The Guardian, Citation2021).

At the time of writing, this remains an issue in that customs checks only began on imported goods to the UK at the start of 2022 given that the UK postponed their introduction, so the full impact of these has yet to be seen on inbound supply chains. Furthermore, full checks on EU imports may be further delayed from the 1st July 2022 deadline.Footnote8 ‘Beyond Brexit’ the issue of communication of key information to the manufacturing industry is linked to ongoing uncertainty around the risks facing their supply chains. This can be seen as a failure on the part of the UK Government to not properly communicate the risks around leaving the EU to the manufacturing industry. As such information about changes to rules around customs, rules of origin, regulation and workers’ rights, to name but a few, was in many cases obtained by businesses via media outlets rather than from official Government and/or professional industry bodies.

Such risks, stemming from leaving the EU, have impacted business operations which have led to delivery delays in some cases, financial losses and fundamental change to businesses – the ripple effect of a risk event leading to impact. Where impact has been less, this can be attributed in part to organisational foresight and forward thinking, utilising personal, internal experience. For example, those manufacturing organisations operating in both EU and international markets were already aware of the potential risks to supply chain in an international jurisdiction. This is an example of the ripple effect, the final stages of SARF, yet impact was less understood by respondents.

Early indicators suggest that the impact to supply chains for businesses in the UK led to increased transaction costs and further challenges in supplying components and finished goods. Thus for them the most successful risk mitigation strategy utilised, in managing supply chain risk, was scenario planning based on existing and historical information. Although unprecedented, leaving the EU can be described as a process rather than a crisis or ‘black swan’ event such as Covid-19. Brexit negotiations had been ongoing for a number of years which led directly to increased uncertainty surrounding the impact of Brexit and the final outcome.

Conclusions

This paper has sought to assess the risk mitigation and supply chain resilience strategies being pursued by firms in advanced manufacturing in the Midlands. Moving forward, beyond Brexit, in order to reduce negative impact on the manufacturing industry, the UK Government must ensure timely information is disseminated to businesses across the UK. This will enable risk analysis of supply chains to occur. This is still very relevant given that the UK has at the time of writing only just begun customs checks on imported products from the EU.

The application of the SARF framework to Brexit and the manufacturing industry provides a novel, risk perspective in the analysis of risk communication and its amplification. It provides insight into the ways in which information was and is disseminated and communicated arising from a risk event, namely Brexit. It helps us to understand the implications of major events and the need for timely and robust dissemination of information to reduce longer-term impact upon businesses and their operations. In applying SARF, as an integrative theoretical framework, it is evident the manufacturing industry could benefit from the establishment of more formalised, implicit networks to share experiences, skills, knowledge and information. In the absence of robust, formalised information from official sources, then reliance on media channels, at best, provides a starting point for risk assessment to occur but this can skew risk perception and analysis in the filtering and transformation of information, deoending on the information presented by the media and opinion leaders.

In a wider sense, to revisit the earlier point that Brexit is a process rather than an event, the current situation between the UK and the EU best represents something of an ‘unstable equilibrium’; whether the TCA itself provides a stable basis for the UK and EU’s trading relationship could itself be tested, especially give tension over the Northern Ireland Protocol (Bailey & Rajic, Citation2022). Thus the nature of the relationship will continue to evolve in ways that cannot be necessarily easily predicted, and hence the nature of risks arising from Brexit themselves may change in unforeseen ways, requiring companies to periodically re-evaluate their operating environment. At the macro level, the TCA opened the door to some major investment such as that by Nissan at Sunderland. Yet we can expect investment and production in the UK to remain subdued relative to what would have occurred with continued EU membership (or even just membership of the Single Market and a Customs Union) as firms re-evaluate their value chains and shift some operations (and jobs) to EU member states over time. Similarly, at the time of writing, it would appear that while manufacturing confidence in the UK is high as the economy recovers from the Covid-19-induced economic contraction, the manufacturing recovery remains constrained by Brexit, with the majority of manufacturers reporting export orders are lower than normal (although what the ‘new normal’ actually is remains a major issue).Footnote9

In the longer-term, in the auto sector the shift to electric vehicles (EVs) raises its own risks (and opportunities) in terms of the UK’s continued ability to capture investment in the production of EVs and associated components (notably, batteries). The 2030 target date for the banning of petrol and diesel cars will be a challenging target to meet and there needs to be much more joined-up thinking in industrial policy, and a clear direction of travel. At the moment government policy in this area fails to add up to a coherent plan to get to 2030, whether in terms of encouraging us to shift over to driving electric vehicles (EVs), or in terms of an industrial strategy that encourages manufacturers to build such cars in the UK after Brexit. A major challenge in the Midlands is the need to attract a major battery ‘giga-factory’ in order to underpin vehicle manufacturing. If this is lost, it is unlikely to ever return to the region (in contrast with, e.g. retail).

However, the ways these developments play out at the micro-level will vary for individual firms and could entail a variety of risk scenarios and mitigating responses. Further research could usefully explore such issues, both from a comparative perspective between countries (e.g. UK-Germany) and regions; and in the form of longitudinal studies tracking individual firms over time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

David Bailey

David Bailey is Professor of Business Economics at the Birmingham Business School, UK.

Alex de Ruyter

Alex de Ruyter is Director of the Centre for Brexit Studies at Birmingham City University, UK.

Claire MacRae

Claire MacRae is Senior Lecturer in Risk Management at Glasgow Caledonian University, UK.

Jon McNeill

Jon McNeill is Lecturer in Risk Management at Glasgow Caledonian University, UK.

Julie Roberts

Julie Roberts is Senior Lecturer in Management at Glasgow Caledonian University, UK.

Notes

2 See for example: https://www.gov.uk/transition.

3 Legal, regulatory, financial, social, economic risks disrupting supply chain and ability to trade.

4 See comments by Rishi Sunak to the House of Commons Treasury Select Committee: ‘It was always inevitable if you change the exact nature of your trading relationship with the EU, that was always going to have an impact on trade flows’ (https://www.ft.com/content/484db1cf-e65e-49b3-a71e-fdd915a874a6).

5 Although large multinationals in the auto sector examined a range of Brexit scenarios in their strategic planning, in the authors’ experience of working with such firms.

7 More broadly, work by Serwicka and Tamberi (Citation2018) suggests that the Brexit vote may have reduced the number of foreign investment projects to the UK by some 16–20 per cent, with Bailey et al. (Citation2019) noting that inward investment flows in advanced manufacturing, food technology and financial services (which can bring ‘good quality’ jobs), are especially vulnerable under Brexit to frictions in global value chains.

9 Springford (Citation2022) suggests that by the end of 2021, leaving the EU single market and customs union had reduced UK goods trade by nearly 15%, with UK exports taking a larger hit than imports. Overall, the OBR (Citation2022) argues that the UK saw a similar collapse in exports as other countries at the start of the pandemic but has since missed out on much of the recovery in global trade, and has maintained its central estimate of a 15% reduction in trade intensity as a result of Brexit.

References

- Alicke, K., & Strigel, A. (2020). Supply chain risk management is back (pp. 1–9). Stuttgart: McKinsey & Company.

- Allen, M. P. (2018). Chronicling the risk and risk communication by governmental officials during the Zika threat. Risk Analysis, 38(12), 2507–2513.

- Aven, T., & Renn, O. (2020). Some foundational issues related to risk governance and different types of risks. Journal of Risk Research, 23(9), 1121–1134.

- Bailey, D. (2019, November 19). Brexit uncertainty means Tesla choses Germany for European new factory. UK in a Changing Europe Commentary. Retrieved from https://ukandeu.ac.uk/brexit-uncertainty-means-tesla-choses-germany-for-european-for-new-factory/

- Bailey, D. (2020). The form of Brexit will still be critical for UK auto. In D. Bailey, A. De Ruyter, N. Fowler, & J. Mair (Eds.), Carmageddon? Brexit & beyond for UK auto (pp. 62–68). Goring: Bite-Sized Books.

- Bailey, D., Clark, J., Colombelli, A., Corradini, C., De Propris, L., Derudder, B., … Usai, S. (2020). Rethinking regions in turbulent times. Regional Studies, 54(1), 1–4. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1698837

- Bailey, D., & De Propris, L. (2017). Brexit and the UK automotive industry. National Institute Economic Review, 242(1), R51–R59.

- Bailey, D., Driffield, N., & Kispeter, E. (2019). Brexit, foreign investment and employment: Some implications for industrial policy? Contemporary Social Science, 14(2), 174–188.

- Bailey, D., & Rajic, I. (2022). Manufacturing after Brexit. London: UK in a Changing Europe.

- Brakman, S., Garretsen, H., & van Witteloostuijn, A. (2020). The turn from just-in-time to just-in-case globalization in and after times of COVID-19; An essay on the risk re-appraisal of borders and buffers. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2, 100034.

- BSI. (2021). Organisational Resilience Index Report 2021.

- Chen, W., Los, B., McCann, P., Ortega-Argiles, R., Thissen, M., & van Oort, F. (2017). The continental divide? Economic exposure to Brexit in regions and countries on both sides of The channel. Papers in Regional Science, doi:10.1111/pirs.12334

- Fiksel, J. (2006). Sustainability and resilience: Toward a systems approach. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 2(2), 14–21.

- The Guardian. (2021, August 24). UK plunges towards supply chain crisis due to staff and transport disruption. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/aug/24/uk-retailers-stock-supply-shortages-covid-pingdemic

- Jardine, C. G., Boerner, F. U., Boyd, A. D., Driedger, S. M., & Cowling, B. J. (2015). The more the better? A comparison of the information sources used by the public during two infectious disease outbreaks. PLoS One, 10(10), e0140028.

- Kasperson, J. X., et al. (2003). The social amplification of risk: Assessing fifteen years of research and theory. In N. Pidgeon, R. Kasperson, & P. Slovic (Eds.), The social amplification of risk (pp. 13–46). London: Cambridge University Press.

- Kasperson, R., Renn, O., Slovic, P., Brown, H., Emel, J., Goble, R., … Ratick, S. (1988). The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis, 8(2), 177–187.

- Klinke, A., & Renn, O. (2014). Expertise and experience: A deliberative system of a functional division of labor for post-normal risk governance. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 27(4), 442–465.

- Kovoor-Misra, S. (2019). Crisis management: Resilience and change. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Lawless, M., & Morgenroth, E. (2019). The product and sector level impact of a hard Brexit across the EU. Contemporary Social Science, 14(2), 189–207.

- Li, D., Shishank, S., De Ruyter, A., Ali, S., Bailey, D., Hearne, D., & Salh, S. (2019). Brexit and the auto industry: Understanding the issues for supply chain management. In A. De Ruyter, & B. Nielsen (Eds.), Brexit Negotiations after Article 50: Assessing Process, Progress and Impact (pp. 171–193). Emerald: Bingley.

- Liu, X., Day, S., Godsell, J., & Zhang, W. (2020, June 29–30). How different disruptions moderate practices contributing to supply chain resilience. In 27th EurOMA Conference (virtual conference), (In Press). Retrieved from http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/138733/

- Mitchell, T., & Harris, K. (2012). Resilience: A risk management approach. ODI background note (pp. 1–7).

- Moradlou, H., Fratocchi, L., Skipworth, H., & Ghadge, A. (2021). Post-Brexit back-shoring strategies: What UK manufacturing companies could learn from the past? Production Planning & Control, doi:10.1080/09537287.2020.1863500

- Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). (2022). The latest evidence on the impact of Brexit on UK trade. Retrieved from https://obr.uk/box/the-latest-evidence-on-the-impact-of-brexit-on-uk-trade/

- Pettit, T. J., Croxton, K. L., & Fiksel, J. (2019). The evolution of resilience in supply chain management: A retrospective on ensuring supply chain resilience. Journal of Business Logistics, 40(1), 56–65.

- Pournader, M., Kach, A., & Talluri, S. (2020). A review of the existing and emerging topics in the supply chain risk management literature. Decision Sciences, doi:10.1111/deci.12470

- Renn, O., & Levine, D. (1991). Credibility and trust in risk communication. In R. E. Kasperson, & P. J. M. Stallen (Eds.), Communicating risks to the public (pp. 175–217). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Rød, B., Lange, D., Theocharidou, M., & Pursiainen, C. (2020). From risk management to resilience management in critical infrastructure. Journal of Management in Engineering, 36(4), 04020039.

- Roscoe, S., Skipworth, H., Aktas, E., & Habib, F. (2020). Managing supply chain uncertainty arising from geopolitical disruptions: Evidence from the pharmaceutical industry and Brexit. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(9), 1499–1529.

- Serwicka, I., & Tamberi, N. (2018). Not backing Britain: FDI inflows since the Brexit referendum. University of Sussex, Brighton: Trade Policy Research Observatory.

- Siegrist, M., & Zingg, A. (2014). The role of public trust during pandemics: Implications for crisis communication. European Psychologist, 19(1), 23–32.

- Slovic, P., & Weber, E. U. (2002). Perception of risk posed by extreme events. Regulation of toxic substances and hazardous waste, 2.

- Slovic, P. E. (2000). The perception of risk. London: Earthscan publications.

- Springford, J. (2022). The cost of Brexit: December 2021. Retrieved from https://www.cer.eu/insights/cost-brexit-december-2021

- UK in a Changing Europe (UKICE). (2021). Manufacturing and Brexit. London: UKICE. Retrieved from https://ukandeu.ac.uk/research-papers/manufacturing-and-brexit/

- Van Der Vegt, G. S., Essens, P., Wahlström, M., & George, G. (2015). Managing risk and resilience. Academy of Management Journal, 58(4), 971–980.

- Winters, M., Jalloh, M. F., Sengeh, P., Jalloh, M. B., Conteh, L., Bunnell, R., … Nordenstedt, H. (2018). Risk communication and Ebola-specific knowledge and behavior during 2014–2015 outbreak, Sierra Leone. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 24(2), 336.