ABSTRACT

This essay explores the generative potential of a particular concept – Derrida’s notion of “hauntology” – across a wide range of heritage domains. In doing so it addresses one of the central concerns of critical heritage, namely what it means to practice criticality and what the social and political implications of this process might be. The paper begins by examining the broad points of intersection between heritage and hauntology, before moving on to consider three more defined areas of thematic overlap. These encompass the ghosts of place, spectral aesthetics, and recent ideas emerging from the environmental humanities around more-than-human hauntings. While there is considerable crossover between these fields, each builds upon a different set of texts and micro case studies to show the distinctive ways in which Derrida’s concept has been taken up and reconfigured in diverse disciplinary contexts. The paper concludes with a summary of the possible implications for adopting (and adapting) hauntology as a mode of doing critical heritage.

Heritage and Hauntology: The No Longer and the Not Yet

In 2017 the BBC invited author Hilary Mantel to deliver the Reith Lectures – one of the highest profile events on the public intellectual calendar in Britain. Perhaps most famous for her historical fiction, including the Wolf Hall series, Mantel’s chosen theme for the lectures – “Resurrection” – engaged directly with many of the longstanding concerns of heritage studies. How can the powerful presence of the past in contemporary social life be accounted for? What is memory beyond subjective personal experience? To what extent might fiction and art help us to comprehend real historical events? Mantel’s starting point for investigating these questions revolved around meeting the dead. “In imagination,” she argued, we often

chase the dead, shouting, ‘Come back!’ We may suspect that the voices we hear are an echo of our own, and the movement we see is our own shadow. But we sense the dead have a vital force still – they have something to tell us, something we need to understand. Using fiction and drama, we try to gain that understanding. I don’t claim we can hear the past or see it. But I say we can listen and look. There are techniques we can use. (Citation2017)

Building on this challenge, this paper aims to re-purpose Jacques Derrida’s concept of “hauntology” to document and stimulate new modes of doing critical heritage. “Becoming hauntologists” from this perspective labels a certain critical comportment towards the work of heritage across various scales and contexts, from local museum displays to large-scale listing processes. To help develop this approach, the paper explores recent engagements with “the ghost” as a conceptual terrain in adjacent fields, including architectural history, art criticism, sociology and the environmental humanities. This mapping exercise is undertaken to define some of the key contours of a possible hauntological heritage practices. As a synthesis of current and ongoing work across a broad range of disciplines, the research presented here is exploratory and open to modification through future grounded experiments (in, for example, curating, archiving and interpretation).

While the argument developed in this essay is based on a prolonged engagement with Derrida’s texts, to be a “hauntologist” does not mean embracing a particular philosophical project. Nor does it signal a concern for the macabre or the gothic. Instead, the notion of the hauntological captures a broad range of attitudes and approaches towards the past in the present that demonstrates the political and ethical charge of critical heritage practice. Concepts, theories, practices and methods overlap and push up against each other in this reading, which may best be understood as an attempt to operationalize what many would consider an obscure and abstract philosophical position. Timothy Morton recognizes that “a truly theoretical approach” to any subject “is not allowed to sit smugly outside the area it is examining. It must mix thoroughly with it” (Citation2007, 12). Taking this further, concepts are only useful if they help us move beyond critique to alternative modes of production. Rather than dismiss a term such as hauntology as arcane and unusable, this paper therefore examines the benefits of taking this concept seriously and addressing its implications via grounded heritage thinking and praxis.

To do this a working definition is needed. The term hauntology is introduced – along with the closely connected spectrality – in Derrida’s 1993 work Spectres of Marx (translated into English in 1994). The word itself relies on the sonic similarity of ontology (ontologie) and hauntology (hauntologie) when spoken in the original French. For Derrida, this aural affinity is useful because it “introduces haunting into the very construction of a concept” (Citation1994, 202). Through this morphological transformation, being – ontology – is displaced by the shadow of the specter of being – hauntology. In so doing a level of uncertainty and intangibility supplants the apparent solidity of the ontological. This is about more than simply destabilizing a word, however. As Fredric Jameson has written in a commentary on Derrida’s text, hauntology describes the recognitions and resurgences that undermine the solid foundations of the present (Citation1999, 38). This does not rely on a conviction that ghosts exist, or even that the past is

alive and at work […] all it says, if it can be thought to speak, is that the living present is scarcely as self-sufficient as it claims to be; that we would do well not to count on its density and solidity, which might under exceptional circumstances betray us. (Citation1999, 39).

Ruin’s mention of the future gestures towards the final (re)orientation that Derrida’s concept brings to the fore. While the figure of the ghost typically points to the past and to those who are no longer, the notion of hauntology also casts a critical lens on the future, or rather to the failure of certain futures to come to fruition. The first and most lasting of these is the specter of communism – highlighted by Marx and Engels in the opening lines of their manifesto as “a virtuality whose threatened coming was already playing a part in undermining the present state of things” (Fisher Citation2014, 19). Hauntology and spectrality from this perspective refer to “a trace that marks the present with its absence in advance” (Derrida in Derrida and Stiegler Citation2013, 39). Such traces can only be discerned tangentially; they resist direct apprehension, operating in the faultlines of received knowledge and authorized histories. Both the no longer and the not yet are to be understood in this way, as specters that haunt the present in their very non-being.

These three hauntological motifs – instability and uncertainty, affective absences, and failed futures – surface across the analysis developed in this paper. As Ruin makes clear, the spectral for Derrida designates an “indeterminate space between the dead and the living” (Citation2014, 61). This space can be filled with many things, projecting our own concerns onto those who have come before, or – in the spirit of Mantel – listening for their voices in the ruptures and discontinuities of the present. To borrow from Colin Davis, the “ghost’s secret” for Derrida is not “a puzzle to be solved; it is the structural openness or address directed towards the living by the voices of the past or the not yet formulated possibilities of the future” (Citation2005, 379). It is here that the political charge of hauntology begins to take shape. Partially formulated in response to the oppressions, injustices and occlusions of global capitalism and liberal democracy, Derrida’s interest in the haunting of being is less about dealing with “spirits from another world” than it is about uncovering a greater sensitivity to “modernity’s phantoms – that is, the disturbances and lingering presences […] through which current social formations manifest the symptomatic traces and uncanny signs of modernity’s history of violence and exclusions” (Demos Citation2013, 13). In this sense, hauntology offers one potential response to Avery Gordon’s important line of questioning in Ghostly Matters: “How do we reckon with what modern history has rendered ghostly? How do we develop a critical language to describe and analyse the affective, historical, and mnemonic structures of such hauntings?” (Citation2008, 18). This essay can be read as an extension of such questions to the realm of heritage practice, which confronts the spectral in a multitude of ways (see Fredengren Citation2016).

Rather than hone in on a specific case study, this paper demonstrates the broad relevance of hauntology to heritage via a series of micro-examples that cut across architectural history, memory studies, critical heritage and the environmental humanities. The first part explores familiar notions of heritage and haunting as they relate to the ghosts of place, exposing some of the tensions that characterize conventional responses to the spectral within heritage thinking. Building on this, the second part introduces two recent approaches to (re)narrating histories of place that may be seen to constitute a form of hauntological heritage practice. In the third and final part contributions to the edited volume Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet (Tsing et al. Citation2017) are critically examined to understand how heritage and hauntology may intersect in responses to the Anthropocene. These three empirical contexts bring to the surface issues of place, history, inheritance, materiality and memory in ways that challenge the work of heritage at various scales and across human and more-than-human worlds. Far from obscuring present inequities and injustices, the concept of the ghost provides a material and discursive anchor throughout this analysis, emerging as “a figure of clarification with a specifically ethical and political potential” (Blanco and Peeren Citation2013, 7). Here it is worth reiterating that the concept of hauntology is only useful if it helps us to do more than simply name a situation: it must direct us towards alternative modes of production and methods of critical engagement.

Given the dangers of over-theorisation that always shadow academic discourse, this “operationalisation” of a philosophical term is undertaken with some caution. The hope however is that becoming hauntologists might signal not an introspective hand-wringing, but a critical touchstone for thinking with the ghost as part of a broader emancipatory project of political and social change. Haunting, as Gordon reminds us, is a “constituent element of modern social life” (Citation2008, 7). Developing a subtle response to the ghost as a figure of ethical and political concern is therefore vital for the grounded work of heritage at a time of rising social tensions and ecological uncertainty. This both tracks and expands upon a wider “spectral turn” in the humanities and social sciences over the past decade (see contributions to Blanco and Peeren Citation2013), positioning heritage as an important interlocutor in the ongoing politicization of modernity’s phantoms.

Ghosts of Place

Howard Jacobson’s remarkable novel J (Citation2014) is set in a dystopian future in which all remnants of the past have been greatly suppressed. Family heirlooms are prohibited, monuments and memorials have been destroyed, and genealogical research is all but impossible, with every member of society having been given a new name and told to forget their origins as part of “Operation Ishmael.” As a result of this erasure it is a peculiarly depthless world: hollow forgiveness is encouraged over “recollection and penance,” while ancient churches have been “morally botoxed” through the smoothing over of gargoyles and other “evil” protrusions (119). Perhaps most tellingly, Proust is no longer read in this world (although the adjective Proustian somehow lingers on to describe an embalming of the past in “morbid memory”).

The reason for this active amnesia is never addressed directly. Instead, the reader is forced to piece together a vast collective trauma, violent and terrifying, through slips of the tongue and thinly veiled references. “WHAT HAPPENED, IF IT HAPPENED” (as this seismic event is described throughout the book) seems to have taken place “off-screen” – indeed, some characters begin to suspect that it may never have happened at all. Remembering the past becomes a thankless task in this context. History and memory are to be avoided at all costs, even while “fake vintage” artefacts proliferate in the faded markets of the capital, “a city seen through a sheet of scratched Perspex” (134).

This makes it all the more unsettling when the past does erupt into the present, forcefully, and without warning. As the main protagonist of the book Kevern Cohen stands before a derelict house in Cohentown, a district of the capital once occupied by wealthy families but now taken over by small industry, the past takes on a rawness and physical closeness it lacks elsewhere:

The disuse of this house suited him better than the subdued occupancy of the others. In the disuse he might reconnect to a line up of used-up Cohens past. He closed his eyes. If you could hear the sea in a washed-up shell why shouldn’t he hear the past in this dereliction? You didn’t begin and end with yourself. If his family had been here he would surely know it in whatever part of himself such things are known – at his fingertips, on his tongue, in his throat, in the throbbing of his temples. Ghosts? Of course there were ghosts. What was culture but ghosts? What was memory? What was self? (2014, 148).

Jacobson’s contribution to a general theory of haunting captures and highlights one of the key conceptual tensions that arise in thinking through the ghosts of place. When sociologist Michael Bell tackled this subject over two decades ago, he began by acknowledging that landscapes are “filled with ghosts. The scenes we pass through each day are inhabited, possessed, by spirits we cannot see but whose presence we nevertheless experience” (Citation1997, 813). At the same time however he maintained that such ghosts are “fabrications, products of imagination, social constructions […] Although we generally experience ghosts as given to us, it is we that give ghosts to places. They do not exist on their own” (831). Any haunting from this perspective is a projection on the part of the haunted individual or the social collective. Tellingly, Bell relates this search for ghosts to the rise of the heritage industry in the 1980s and 1990s, a phenomenon he explains as a response to the disenchantments of modernity (Weber [Citation(1919) 1946]). While this view of the spectral may depend on the specific aura or atmosphere of a location, it is a human centered idea that effectively undermines any claims the past may make on the present. If all ghosts are the product of our imagination, then the power of the dead over the living is greatly reduced. Hauntology does not seek to overcome this tension so much as unearth the generative and ethical potential in its contradictions. Derrida after all was interested in the foundational paradox of an effectivity that is “ineffective, virtual, insubstantial” (Citation1994, 10). In saying that this is always somehow more than a projection of the present onto the past, hauntology opens up a different mode of “being with the dead” (Ruin Citation2019). As Ruin argues,

What we perceive as ‘our’ society consists not only of the living, but also, and often more importantly, of those no longer alive. There is a fundamental social being with the dead that displaces the very idea that the world is made up of only ourselves and those currently alive. (Ruin Citation2017, 416)

This line of enquiry opens up a second point of tension in the thinking around heritage and haunting – namely that a concern with “ghosts” may in fact constitute a form of socio-political exorcism. Crucially, the practice of heritage has been the focus of sustained criticism in such thinking, with David McNeill for example claiming that “history as a séance, a conjuration, is as accurate a metaphor for the activities of National Heritage organisations as we are likely to find” (Citation2001, 55). This is because heritage for McNeill depends on a process whereby “selected ‘friendly’ ghosts are trapped and condemned to a perpetual purgatory inside upholstered chaise lounges, bell jars, commodes, dados and stucco frames” while others are “sent packing” (ibid). Tim Edensor makes a similar point in relation to industrial ruins, arguing that practices of heritage management in which places are “cleaned up and subject to interpretative encoding” limit our capacity to “empathetically grasp” the ghosts of derelict spaces (Citation2005, 151). While the affective experience of haunting may be vital to understanding why heritage matters, such critiques remind us that the very work of heritage is just as likely to smooth away the ghosts of place as reveal their full potency.

Issues of atmosphere, aura and affect can only take us so far in this respect. While themes of haunting capture something of the re-enchantment that Bell links to the ghosts of place, and Edensor locates in the ruins of industry, a further gesture is required to get at the ethical-political significance of the hauntological for heritage. To borrow from Gordon, “following the ghosts” is about “making a contact that changes you and refashions the social relations in which you are located. It is about putting life back in where only a vague memory or a bare trace was visible to those who bothered to look.” This action is undertaken not simply to pay lip-service to the past, but “to strive to understand the conditions under which a memory was produced in the first place, toward a countermemory, for the future” (Citation2008, 22).

The engagement with hauntology advanced in this paper emerges from earlier research focused on the abandoned town of Varosha in Northern Cyprus, where the desire to “put life back in” can be discerned with great clarity in the desire for return articulated by Greek-Cypriot diaspora communities (see Sterling Citation2014). Through a combination of memory-work and political activism, the former residents of Varosha seek to re-inhabit the streets and homes they left in 1974, when Turkey invaded Cyprus, creating a “Dead Zone” that divides the Turkish north of the island from the Greek south (see contributions to Papadakis, Peristianis, and Welz Citation2006; Bryant and Papadakis Citation2012). Varosha – which was developed in the 1960s and early 1970s as a major tourist resort – lies just inside this border space, and is now home to a small garrison of Turkish troops. As Alan Weisman writes in his striking work The World Without Us, which imagines what would happen to the Earth if humanity suddenly disappeared, Varosha has now entered an advanced state of decay:

Its encircling fence and barbed wire are now uniformly rusted, but there is nothing left to protect but ghosts. An occasional Coca Cola sign and broadsides posting nightclubs’ cover charges hang on doorways that haven’t seen customers in more than three decades, and now never will again. Casement windows have flapped and stayed open, their pocked frames empty of glass. Fallen limestone facing lies in pieces. Hunks of wall have dropped from buildings to reveal empty rooms, their furniture long ago somehow spirited away. Paint has dulled; the underlying plaster, where it remains, has yellowed to muted patinas. (Citation2007, 96)

Like Cohentown, Varosha also brings to the surface a fundamental tension between ghosts as a subjective “fabrication” and the sensuous, melancholic and affective power of certain spaces. This problem is taken up by Yael Navaro-Yashin in her own investigation of the “abject” ruins of Northern Cyprus, a category which encompasses objects, homes and the wider socio-political environments people occupy (Citation2009). Taking issue with the wholesale dismissal of social constructionism that has permeated the humanities and social sciences in the wake of the “affective turn,” Navaro-Yashin puts forward the metaphor of the ruin as a potential bridge between these two theoretical frames. The ruin “discharges an affect of melancholy” even while those who live with such objects and spaces “put them into discourse, symbolize them, interpret them, understand them, project their subjective conflicts onto them, remember them, try to forget them, historicize them, and so on” (15). This is important for our reading of hauntology not only because ghosts are so regularly associated with ruinous contexts, but also because critical heritage scholars have often prioritized one or the other of these theoretical positions rather than explore their reciprocity (although see Waterton and Watson Citation2014 for a valuable exploration of material-semiotics in heritage tourism). The discursive and the affective are not fundamentally opposed in hauntology, but rather reinforce each other in the work of speaking with the dead. It is impossible to comprehend the meaning or the power of the “ghosts” of Varosha (or indeed Cohentown) without this dual orientation.

How people respond to the ghosts of place is a vital question for heritage. Do they see such figures are merely products of the imagination, or can there be an acknowledgement that the dead have an active role to play in social life? Are these responses mutually exclusive or in fact complementary? Becoming a “hauntologist” – the noun developed here as an extension of Derrida’s concept – does not mean believing in ghosts as spirits from another world, but it does require a commitment to acting in the presence of those who are no longer in a way that admits their continued efficacy. This depends upon a mode of doing heritage that is more than “the passive enactment and reaffirmation of meanings we have inherited” (Diprose Citation2006, 437). As Derrida argued towards the end of his life, for any heritage to be “active” it demands “reinterpretation, critique, displacement, that is, an active intervention, so that a transformation worthy of the name might take place: so that something might happen, an event, some history, an unforeseeable future-to-come” (Derrida and Roudinesco Citation2004, 4, emphasis in original). The “critical” in critical heritage depends upon this constant self-critique that actively transforms what is given, including the concepts and practices inherited from critical theory. Hauntology as praxis – “the actions and decisions that characterise politics and ethics” (Diprose Citation2006, 440) – responds to this injunction, which entails a certain level of responsibility towards what has come before as well as what might come after. To understand the grounded implications of this stance in terms of alternative modes of production, the aesthetic qualities of hauntology require further elaboration.

Critical Heritage Aesthetics

David McNeill’s characterization of heritage as a “séance” or “conjuration” (quoted above) is important to the argument developed in this paper not just because it foregrounds the structural failure of heritage to adequately account for the ghosts of place, but also for the specific context in which it is offered: namely as a response to the work of artist Michael Goldberg, who seeks to “invite back the ghosts that sanitized history has banished” (McNeill Citation2001, 54). As an example of this practice McNeill describes an installation in the cellar rooms of one of Sydney’s grandest colonial villas, where the artist set up “a series of complex displays that serve to summon up the history of dispassion, privilege, pomposity and avariciousness that marks the history of our settler culture” (55). This intervention included artefacts, props and documents related to the original land grant for the house as well as the distant Palladian origins of its design. In another installation Goldberg placed half a dozen Royal Doulton figurines in an elderly display case purposefully situated in an unrestored room of the extravagant Elizabeth Bay House. At the bottom of the display a small adhesive label stated simply “Museum Exhibits Can Conceal Complex Personal Histories” (55–56). Such mediations for McNeill highlight the uncritical allegiance to “authentic” renovations and simplistic interpretation typical of heritage practice, which emerges in this reading as an all-too efficient mode of historical closure.

Over the past two decades (and maybe even longer) many artists and cultural critics have taken up the spectral as an analytical framework. This has often gone hand-in-hand with a subversion of the museum, the archive and the historic site as spaces of historical knowledge production. The 1990s work of Fred Wilson is an obvious touchstone here for the way it sought to “mine” the museum (in this case the collections of the Maryland Historical Society) in the service of a more ethical engagement with the past. As the artist wrote at the time,

museums are afraid of what they will bring to the surface and how people will feel about certain issues that are long buried. They keep it buried, as if it doesn’t exist, as though people aren’t feeling these things anyway, instead of opening that sore and cleaning it out so it can heal. (Wilson Citation1994, 34)

Perhaps the most sustained engagement with an “aesthetics of the ghostly” comes from T. J. Demos, whose investigation of recent photographic and filmic practices addressing the lingering effects of empire in postcolonial Africa is documented in Return to the Postcolony: Specters of Colonialism in Contemporary Art (Citation2013). Demos pays close attention to the different ways in which artists engaging with this context (including Sven Augustijnen, Vincent Meessen, Zarina Bhimji and Pieter Hugo) have sought to open up repressed colonial histories in the hope of engendering a “politics of memory in partnership with the dead in struggle” (18). “How can ghosts be laid to rest,” Demos asks, “when the events that unleashed them are not entirely concluded, only repressed in the present?” (21, emphasis in original). Whilst it would be wrong to conclude that each of the projects Demos goes on to examine works in the same aesthetic register, he identifies an overarching “spectral” turn in postcolonial art that seeks to address “the haunting memories and ghostly presences that refuse to rest in peace and cannot be situated firmly with representation” (8). Building on the recent formulations of speculative realism (see Bryant, Srnicek, and Harman Citation2011), Demos characterizes such work by its commitment to “a different set of documentary possibilities that bring affect, imagination, and truth into a new experimental configuration” (Citation2013, 9). The slow, meditative films of Zarina Bhimji – many of which focus on ruinous buildings across postcolonial Uganda – are a case in point, drawing as they do on in-depth historical research, fictional narratives and the sensuous qualities of light in interior spaces. As Bhimji has stated, this approach is less about gathering “scraps of evidence to support the assertion of history” than it is a process of recognizing “traces as symptoms of strange structural links between history, memory and fantasy” (quoted in Demos Citation2012, 20).

At the risk of making too great a leap between the worlds of literature and art (and between two very different socio-political and aesthetic contexts), Demos’ formulation may help to identify the source of Kevern Cohen’s ambivalent reaction to the ghosts of Cohentown. Put simply, whilst Kevern is able to imagine the past in the ruins and sense the affective presence of those who are no longer, he lacks the historical knowledge necessary to allow the truth of Cohentown to emerge. It is this “experimental configuration” that imbues the work of Bhimji and others with a certain critical-creative power that may be usefully described as hauntological.

While Derrida’s theory of hauntology clearly has much to offer any engagement with hidden, neglected or repressed traces of the past in the present, it is also oriented towards the future, and especially towards those futures which the twentieth century taught us to expect but that never came to fruition. This sense of lost futures has been a core concern of artists working in a range of media over the last decade. Indeed, in a wide-ranging analysis of British film and musical culture of the 2000s, Mark Fisher defines this period as one that could not help but confront “a cultural impasse: the failure of the future” (Citation2012, 16). Hauntology emerges as a useful frame of reference here because it is concerned with that which “has not yet happened, but which is already effective in the virtual (as an attractor, an anticipation shaping current behaviour)” (19, emphasis in original). Crucially this extends beyond the realm of the arts to encompass social democracy as a whole. As Fisher explains,

the disappearance of the future meant the deterioration of a whole mode of social imagination: the capacity to conceive of a world radically different from the one in which we currently live. It meant the acceptance of a situation in which culture would continue without really changing, and where politics was reduced to the administration of an already established (capitalist) system. (16)

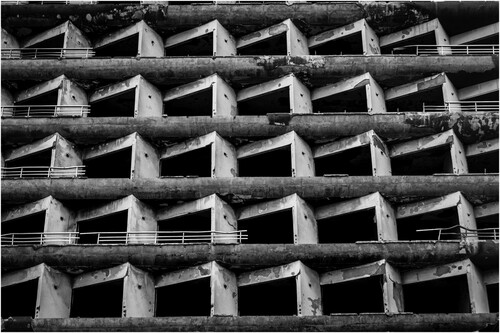

One area in which such tensions are currently manifest relates to the listing and widespread celebration of post-war architecture in Britain. Over the past decade a cottage industry of photographic books, detailed histories, small exhibitions, building tours and online resources has emerged with a clear purpose: to reinvigorate interest in a much-maligned period of British architecture characterized by concrete, tower blocks and large-scale urban redevelopment. Recent examples of this cultural reassessment include the exhibition Brutalist Playground held at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 2015, John Grindrod’s popular memoir of life in the suburbs, Concretopia (Citation2014), and the temporary opening by the National Trust of a flat in Balfron Tower – a 1960s brutalist tower block designed by Ernö Goldfinger. While these projects take different aspects of the post-war built environment as their core focus, most are interested both in the architectural qualities of key buildings and their utopian aspirations, which were “premised on the movement toward a scarcely imaginable future” (Fisher Citation2012, 18). This passage from Barnabas Calder’s Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism is typical in this regard:

Some of the most high-profile and widely admired architectural projects of the 1950s and ‘60s were social housing, including Park Hill in Sheffield, the Alton Estate in suburban London, and the Queen Elizabeth Flats in Glasgow. Whatever mistakes were made by those commissioning, designing, and building some of the blocks, and however difficult the following decades were for many such projects, real effort and thought went into producing good living environments and a sense of community for people who were not well off. Whatever else Brutalist architecture and clients may have been up to, this baseline of serious social endeavour should be taken as a constant background. (Citation2016, 83)

Against this cultural and historical backdrop, a series of prominent interventions around the listing of post-war buildings has taken place in recent years. Former head of English Heritage Simon Thurley for example has claimed that “the whole listed-building system, the legislation and everything based around keeping the fabric, is not relevant. These buildings are about ideas and other things. For the 20th century, you’ve got to have a different system” (in Alberge Citation2016). Although Thurley does not go so far, this raises the possibility of an alternative approach to built heritage, one based around acknowledging and perhaps even restaging the social aspirations of architectural forms, rather than simply conserving and protecting their physical fabric (Mould Citation2017). This approach – which may be labeled hauntological – would not be suited to every site, but in certain contexts the potential to move heritage beyond conjuration and exorcism might be explored through new interpretive strategies and listing processes.

The aforementioned Balfron Tower is a case in point. First listed by English Heritage (now Historic England) in 1996, this prominent East London landmark was recently upgraded to Grade II* (the second highest designation) following a high-profile campaign by, amongst others, the Twentieth Century Society (Marrs Citation2015). This campaign was partly motivated by a proposed refurbishment of the building that would have seen original features removed and internal layouts significantly altered. Putting aside for a moment the controversy over the final outcome of this renovation (see Evans Citation2019), what is important is the missed opportunity for an entirely different strategy of heritage practice at the site: a strategy that might well be described as hauntological. Referencing the work of artist-architect David Roberts, this practice would not only “pay tribute” to the “egalitarian principles” of post-war housing, it would also “enact” their utopian aspirations (Citation2017, 123). As Roberts argues, the fundamental misconception at the heart of both the redevelopment proposals and the heritage listing has been the idea that the past is something to be honored, rather than radically re-performed (144).

It is worth noting that Roberts was able to put this approach into action via a series of creative projects that intersect with and subvert various fields of heritage practice. This included staging small-scale exhibitions with facsimile material from the RIBA Archives inside the domestic spaces of Balfron Tower, re-enacting the brief period Goldfinger and his wife spent in the building when it opened with actors and contemporary residents, and lobbying the government to recognize the dangers of social cleansing in the process of “decanting” the building for redevelopment. Like the work of Bhimji in Uganda, the spectral qualities of such counter-heritage practices are built around a commitment to in-depth historical research and creative re-workings of the material present. As Roberts has written on the exhibition of archival documents on-site,

Our restaging touched on the spirit of the original endeavour; a community was not just re-enacted but, if only temporarily, reconstituted. There was a considerable level of engagement with the material on display. Dressing a flat that is identical to residents’ homes as an archive makes it estranging and uncanny, and it forced people to see their own flats differently and acted as a trigger for memories. Alongside the informal theatricality, it created a setting where people stepped outside their daily routine into a mode of critical reflection, to re-examine their estate, their flats and themselves. (Citation2017, 140)

More-than-human Hauntings

So far this paper has taken a purposefully expansive view of heritage and hauntology to consider productive points of tension and critical-creative practices across literature, architectural history, museum displays and contemporary art. The aim of this synthesis has been to map out some of the key dimensions of the hauntological in the hope of demonstrating the grounded implications of this somewhat arcane concept for critical heritage studies. Rather than limit this scope in the final section, the reach of hauntology is expanded even further by investigating the significance of “the ghost” within emergent posthumanist thinking. While heritage scholars have begun to engage with this literature (see Harrison Citation2015; Fredengren Citation2015, Citation2016; DeSilvey Citation2017; Sterling Citation2020) the arguments and propositions of hauntology may provide a useful space for integrating heritage and the posthumanities further. This tentative work is based on a close reading of the edited collection Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene (Tsing et al. Citation2017), which – as its subtitle suggests – takes the haunted and monstrous qualities of the current environmental predicament as its core focus.

The various ghosts recounted in the pages of Arts of Living encompass a multitude of materialities and subjectivities. Biologist Ingrid Parker for example describes the lost wildflowers of California as “like ghosts […] the vision of their exuberance haunts me as I gaze upon the rolling hills around my home” (Citation2017, M160). Writer Kate Brown meanwhile gives an account of the ghostly specks of radiation that permeate photographs taken inside the “sarcophagus” at Chernobyl – “tiny crystalline flakes that float through every scene of silent ruin, lending the photos a deep-sea feel” (Citation2017, G41). For others in the volume it is extinction – and specifically human-led extinction – that generates spectral legacies. As Jens-Christian Svenning elucidates in a chapter on the possible return of megafauna to certain landscapes, “wilderness and other natural areas around the world are haunted by ghosts of giant animals […] their disappearance – which continues today, as seen in the rhino-poaching crisis in Africa – is tightly linked to us, Homo sapiens” (Citation2017, G67). This in turn highlights the entangled nature of such hauntings: things do not evolve, thrive and disappear in isolation. As Thom Van Dooren reminds us in his own work on “spectral crows,” extinction “always takes the form of an unravelling of co-formed and forming ways of life, an unravelling that begins long before the death of the last individual and continues to ripple out long afterwards” (Citation2014, 12). This applies to plants as well as to animals – a process anthropologist Andrew Matthews records in his ethnographic exploration of former agricultural landscapes in central Italy:

Through my practices of walking, looking, and wondering, I have been tracing the ghostly forms that have emerged from past encounters between people, plants, animals, and soils. These ghostly forms are traces of past cultivation, but they also provide ways of imagining and perhaps bringing into being positive environmental futures. (Citation2017, G145)

the monsters and ghosts of this book are observable parts of the world. We learn them through multiple practices of knowing, from vernacular to official science, and draw inspiration from both the arts and sciences to work across genres of observing and storytelling. (Swanson et al. Citation2017, M3)

we need to bring all types of research to the table, from anthropology and archaeology to historical archival research, as well as experimental ecology and molecular ecology […] Perhaps with a combination of imagination, scientific inquiry, and conservation inspiration, we will see more ghosts come back to life. (Citation2017, M165)

The word hauntology appears only once in Arts of Living – without citation and in parentheses – in a characteristically wide-ranging contribution from Karen Barad that builds on the same authors earlier engagement with Derrida’s concept (Citation2010). The reference (or lack thereof) arises in a passage on the politics of matter and quantum physics in the “nuclear age” (Barad Citation2017, G110). The atom bomb and quantum physics are “deeply entangled,” Barad argues, and it is this mutual constitution that marks out an “ontology (hauntology)” of the latter. Quantum physics is not inherently more neutral or more radical than Newtonian physics, but it is historically and materially immersed in the devastation wrought by atomic weaponry. It is this entanglement that leads Barad to explore the haunted temporalities of the nuclear, beginning with Hiroshima, where the clocks were arrested on August 6, 1945 at 8:15am. As Barad explains, such “landtimescapes are surely haunted, but not merely in the sense that memories of the dead, of past events, particularly violent ones, linger there. Hauntings are not immaterial. They are an ineliminable feature of existing material conditions” (G107). While this sense of material haunting is vital to understanding Barad’s engagement with ghosts, it pushes against familiar notions of the spectral. This is because from the perspective of quantum physics, “hauntings” are not part of subjective human experience, but are instead “lively indeterminacies of time-being, materially constitutive of matter itself – indeed, of everything and nothing” (G113). To be haunted is not a mere remembrance of the past in this reading, but a recognition of the dynamism of “time-being/being-time” in each and every moment. As such, for Barad any “injustices need not await some future remedy, because ‘now’ is always already thick with possibilities disruptive of mere presence” (G113).

This notion of disrupting “mere presence” is a useful point to end on – a reminder of the instability of ontology that first prompted Derrida to explore the hauntological as a mode of non-being. In their introduction to Arts of Living, editors Elaine Gan, Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson and Nils Bubandt ask how we might get back to the pasts we need “to see the present more clearly?” (Citation2017, G2). The figure of the ghost emerges here as a way of returning to “multiple pasts,” a process that might equally be considered a thickening of the present. This potentiality invites a renewed consideration of the now from different disciplinary perspectives in a way that might “transcend amnesia,” to borrow from Parker. By centering the ghost in possible responses to the Anthropocene, the scholars, artists, writers and scientists brought together in this volume do not absolve themselves from the urgent problems of the present, but rather acknowledge the continued reverberations of the past in current environmental inequities and injustices. These echoes and traces are rarely self-evident, even if their effects may be widespread and obdurate. Haunting after all is “quite properly eerie: the presence of the past often can be felt only indirectly, and so we extend our senses beyond their comfort zones” (Gan et al. Citation2017, G2). The more-than-human qualities of heritage come to the fore in this setting, as the past resonates with forces beyond comprehension, while the present and the future seethe with otherworldly threat and promise.

Conclusions

An applied notion of hauntology demands an intersectional praxis of historical noticing and critical-creative heritage productions across human and non-human worlds. Storytelling – as Mantel would no doubt recognize – is a vital methodology, whether in the form of books, site biographies, curatorial displays, films, photographs, oral history recordings, performances, commemorative plaques or any other narrative device. Limiting hauntology to such discursive strategies would however be a mistake. While this paper has only touched on the wider implications of the hauntological for the heritage sector, there are important links to be made with ongoing work in architectural preservation, site management, conservation and museology. As Christina Fredengren notes, the search for a “more visceral, more affecting and, potentially, more moving heritage experience is key to driving altered curatorial practices” (Citation2016, 492). This means looking beyond individual subjectivities and easily packaged stories. As this paper has shown, the ghosts of the present encompass collective histories of violence and exclusion, personal narratives of trauma and redemption, extinct lifeforms and vanished ways of being, failed political projects and imperceptible material traces. Each phantom requires a different mode of apprehension, a different hauntology. The practical implications of this stance for heritage are wide-ranging. For practitioners involved in site management or interpretation, there is a clear need to evoke repressed and hidden narratives alongside and in conjunction with new approaches to material inheritance. In the spirit of Barad, this “spacetimemattering” might be considered a productive reconfiguration of the world, one which acknowledges that “our debt to those who are already dead and those not yet born cannot be disentangled from who we are” (Citation2010, 266). For curators, conservators and other museum professionals meanwhile a hauntological approach may add an extra dimension to ongoing debates around ecological justice and decolonization (Sully Citation2007; Onciul Citation2015; Aikens Citation2016; Kidd et al. Citation2017), both of which seek to address a similar set of concerns related to acknowledgment, repression and intergenerational care. Hauntology is only useful if it pushes forward the transversal connections between such emancipatory agendas, which critical heritage should no longer view in isolation.

Some common themes and trajectories for this work can be discerned in the various responses to the spectral emerging across literature, anthropology, sociology, the environmental humanities and the arts. The extent to which these responses engage directly with the notion of hauntology varies considerably. This however may be less important than the underlying motivations for such work, which routinely (if implicitly) share a concern with Derrida’s call for a politics “of memory, of inheritance, and of generations” (quoted in Demos Citation2013, 43). This can be seen in Howard Jacobson’s fiction, Zarina Bhimji’s film works, and Karen Barad’s fusion of critical theory and quantum physics. Mapping such diverse projects allows us to see how a critical-creative heritage practice might contribute to some of the most urgent debates of our time. As Derrida observed in Spectres of Marx,

no justice […] seems possible or thinkable without the principle of some responsibility, beyond all living present, within that which disjoins the living present, before the ghosts of those who are not yet born or who are already dead, be they victims of violence, nationalist, racist, colonialist, sexist, or other kinds of exterminations, victims of capitalist imperialism or any of the forms of totalitarianism. (Citation1994, xviii)

we cannot find comfort in nostalgia for Derrida, for works in his name, or for any other aspects of one’s heritage, personal, biological, cultural, or philosophical. In the extraordinary responsibility of inheriting the future-to-come, it is all of this that we must continue to interrupt, transform, and put at risk. (Citation2006, 446)

Acknowledgements

An ancestor of this paper was presented in 2017 as part of a “World Café” held at the Centre for Anthropological Research on Museums and Heritage in Berlin. I am grateful to participants at this meeting for their comments, which helped to redirect my thoughts on hauntology in valuable ways. I am also indebted to this journal’s two anonymous referees, who made important suggestions on how I might improve the essay. All errors and omissions are my own.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Colin Sterling

Colin Sterling is Assistant Professor of Memory and Museums at the University of Amsterdam. Prior to this he was an AHRC Early Career Leadership Fellow at UCL Institute of Archaeology. Colin's research focuses on critical-creative approaches to heritage, memory and museums. He is interested in how artists, designers, architects, writers and other creative practitioners engage with museums and heritage as spaces of critical enquiry. Colin is the author of Heritage, Photography, and the Affective Past (Routledge, 2020) and co-editor of Deterritorializing the Future: Heritage in, of and after the Anthropocene (Open Humanities Press, 2020).

References

- Aikens, Nick, ed. 2016. Ecologising Museums. Ghent: L’Internationale Online.

- Alberge, Dalya. 2016. “Save Our Brutalist Masterpieces, Says Top Heritage Expert.” The Guardian, November 13. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/nov/13/save-brutalist-buildings-warns-simon-thurley.

- Barad, Karen. 2010. “Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/Continuities, SpaceTime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-Come.” Derrida Today 3 (2): 240–268.

- Barad, Karen. 2017. “No Small Matter: Mushroom Clouds, Ecologies of Nothingness, and Strange Topologies of Spacetimemattering.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, G103–G120. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bell, Michael Mayerfield. 1997. “The Ghosts of Place.” Theory and Society 26 (6): 813–836.

- Blanco, Maria del Pilar, and Esther Peeren, eds. 2013. The Spectralities Reader: Ghosts and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Brown, Kate. 2017. “Mare Curie’s Fingerprints: Nuclear Spelunking in the Chernobyl Zone.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, G33–G50. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bryant, Rebecca, and Yiannis Papadakis, eds. 2012. Cyprus and the Politics of Memory: History, Community and Conflict. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Bryant, Levi, Nick Srnicek, and Graham Harman, eds. 2011. The Speculative Turn: Continental Materialism and Realism. Melbourne: re.press.

- Calder, Barnabas. 2016. Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism. London: William Heinemann.

- Davis, Colin. 2005. “Hauntology, Spectres and Phantoms.” French Studies 59 (3): 373–379.

- Demos, T. J. 2012. Zarina Bhimji: Cinema of Affect. In: Zarina Bhimji et al., Zarina Bhimji [Catalogue of exhibition held at Whitechapel Gallery 20 January–14 April 2012]. London: Whitechapel Gallery; Kunstmuseum Bern; The New Art Gallery Walsall; Ridinghouse.

- Demos, T. J. 2013. Return to the Postcolony: Specters of Colonialism in Contemporary Art. Berlin: Sternberg.

- Derrida, Jacques. 1994. Spectres of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. Translated by Peggy Kamuf. London: Routledge.

- Derrida, Jacques, and Bernard Stiegler. 2013. “Spectographies.” In The Spectralities Reader, edited by Maria Del Pilar Blanco and Esther Peeren, 37–51. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Derrida, Jacques, and Elisabeth Roudinesco. 2004. For What Tomorrow: A Dialogue. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- DeSilvey, Caitlin. 2017. Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Diprose, Rosalyn. 2006. “Derrida and the Extraordinary Responsibility of Inheriting the Future-to-come.” Social Semiotics 16 (3): 435–447.

- Edensor, Tim. 2005. Industrial Ruins: Space, Aesthetics and Materiality. Oxford: Berg.

- Evans, Judith. 2019. “Inside the Tower Block Refurbished for Luxury Living.” Financial Times, May 3. Accessed May 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/f4e7a2c6-5aa1-11e9-939a-341f5ada9d40.

- Fisher, Mark. 2012. “What is Hauntology?” Film Quarterly 66 (1): 16–24.

- Fisher, Mark. 2014. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Winchester: Zero Books.

- Fredengren, Christina. 2015. “Nature:Cultures – Heritage, Sustainability and Feminist Posthumanism.” Current Swedish Archaeology 23: 109–130.

- Fredengren, Christina. 2016. “Unexpected Encounters with Deep Time Enchantment. Bog Bodies, Crannogs and ‘Otherwordly’ Sites. The Materializing Powers of Disjunctures in Time.” World Archaeology 48 (4): 482–499.

- Gan, Elaine, Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, and Nils Bubandt. 2017. “Introduction: Haunted Landscapes of the Anthropocene.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Anne Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, G1–G14. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gordon, Avery. 2008. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Grindrod, John. 2014. Concretopia: A Journey Around the Rebuilding of Postwar Britain. Brecon: Old Street.

- Harrison, Rodney. 2015. “Beyond “Natural” and “Cultural” Heritage: Toward an Ontological Politics of Heritage in the Age of the Anthropocene.” Heritage & Society 8 (1): 24–42.

- Hewison, Robert. 1987. The Heritage Industry: Britain in a Climate of Decline. London: Methuen.

- Hopkins, Owen. 2017. Lost Futures: The Disappearing Architecture of Post-war Britain. London: Royal Academy of Arts.

- Jacobson, Howard. 2014. J. London: Vintage.

- Jameson, Fredric. 1991. Postmodernism: Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Jameson, Fredric. 1999. “Marx’s Purloined Letter.” In Ghostly Demarcations: A Symposium on Jacques Derrida’s Spectres of Marx, edited by Michael Sprinker, 26–67. London: Verso.

- Kidd, Jenny, Sam Cairns, Alex Drago, Amy Ryall, and Miranda Stearn, eds. 2017. Challenging History in the Museum: International Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Mantel, Hilary. 2017. “Why I Became a Historical Novelist.” The Guardian, June 3. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/jun/03/hilary-mantel-why-i-became-a-historical-novelist.

- Marrs, Colin. 2015. “C20 Society Demands Balfron Tower Rethink.” Architecture Journal, October 27. https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/home/c20-society-demands-balfron-tower-rethink/8691067.article.

- Matthews, Andrew S. 2017. “Ghostly Forms and Forest Histories.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, G145–G156. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McNeill, David. 2001. “Heritage and Hauntology: The Installation Art of Michael Goldberg.” In What is Installation?: An Anthology of Writings on Australian Installation Art, edited by Adam Geczy, and Benjamin Genocchio, 54–59. Sydney: Power Publications.

- Meskell, Lynn. 2002. “Negative Heritage and Past Mastering in Archaeology.” Anthropological Quarterly 75 (3): 557–574.

- Morton, Timothy. 2007. Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mould, Oli. 2017. “Brutalism Redux: Relational Monumentality and the Urban Politics of Brutalist Architecture.” Antipode 49 (3): 701–720.

- Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2009. “Affective Spaces, Melancholic Objects: Ruination and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15: 1–18.

- Onciul, Bryony. 2015. Museums, Heritage and Indigenous Voice: Decolonising Engagement. New York: Routledge.

- Papadakis, Yiannis, Nicos Peristianis, and Gisela Emmi Welz, eds. 2006. Divided Cyprus: Modernity, History, and an Island in Conflict. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Parker, Ingrid M. 2017. “Remembering in Our Amnesia, Seeing in Our Blindness.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, M155–M167. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Roberts, David. 2017. “Make Public: Performing Public Housing in Ernö Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower.” The Journal of Architecture 22 (1): 123–150.

- Roberts, Catherine, and Philip Stone. 2014. “Dark Tourism and Dark Heritage: Emergent Themes, Issues and Consequences.” In Displaced Heritage: Responses to Disaster, Trauma, and Loss, edited by Ian Convery, Gerard Corsane, and Peter Davis, 9–18. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press.

- Ruin, Hans. 2014. “Spectral Phenomenology: Derrida, Heidegger and the Problem of the Ancestral.” In The Ashgate Companion to Memory Studies, edited by Siobhan Kattago, 61–74. London: Routledge.

- Ruin, Hans. 2017. “Review Essay: History and its Dead.” History and Theory 56 (3): 407–417.

- Ruin, Hans. 2019. Being with the Dead: Burial, Sacrifice, and the Origins of Historical Consciousness. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Sterling, Colin. 2014. “Spectral Anatomies: Heritage, Hauntology and the ‘Ghosts’ of Varosha.” Present Pasts 6 (1): 1–15.

- Sterling, Colin. 2019. “Designing ‘Critical’ Heritage Experiences: Immersion, Enchantment and Autonomy.” Archaeology International 22 (1): 100–113.

- Sterling, Colin. 2020. “Critical Heritage and the Posthumanities: Problems and Prospects.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26 (11): 1029–1046.

- Sully, Dean, ed. 2007. Decolonising Conservation: Caring for Maori Meeting Houses Outside New Zealand. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Svenning, Jens-Christian. 2017. “Future Megafaunas: A Historical Perspective on the Potential for a Wilder Anthropocene.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, G67–G87. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Swanson, Heather, Anna Tsing, Nils Bubant, and Elaine Gan. “2017. “Introduction: Bodies Tumbled into Bodies.” In Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, Nils Bubandt, M1–M12. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Tsing, Anna, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, eds. 2017. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Van Dooren, Thom. 2014. “Life at the Edge of Extinction: Spectral Crows, Haunted Landscapes and the Environmental Humanities.” Humanities Australia 5: 8–22.

- Waterton, Emma, and Steve Watson. 2014. The Semiotics of Heritage Tourism. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Weber, Max. (1919) 1946. “Science as a Vocation.” In From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, edited by H. H. Gerth, and C. Wright Mills, 129–156. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Weisman, Alan. 2007. The World Without Us. London: Virgin Books.

- Wilson, Fred. 1994. Mining the Museum: An Installation by Fred Wilson. Baltimore: The Contemporary.

- Wright, Patrick. 1985. On Living in an Old Country: The National Past in Contemporary Britain. London: Verso.