ABSTRACT

Are populist attitudes too thin to matter for populist support? Considering their interplay with thick nativist attitudes, we argue that both populist attitudes and their subdimensions play a key role in the propensity to vote for each of the main populist parties within the 2021 Czech legislative election. The results from our survey (N = 2009) show that populist attitudes and their subdimensions are notable predictors whose role is not fully conditioned by thick nativist attitudes. Furthermore, the unique effects of subdimensions tend to reflect the emphasis that populist parties place on the corresponding components of populist ideology in their communication.

Introduction

For several decades the world has been experiencing a populist surge. The increasing electoral success of populist parties is often associated with voters’ strong populist attitudes. Despite their thin nature, populist attitudes have been shown to significantly contribute to electoral support for populist parties in various contexts (see Akkerman, Mudde, and Zaslove Citation2013; Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser, and Andreadis Citation2020). However, some studies indicate that the bond between populist attitudes and populist support is not always so solid. Specific policy preferences or political attitudes can outperform the impact of populist attitudes on populist support (see e.g. Castanho Silva, Fuks, and Tamaki Citation2022; Stanley Citation2011).

Considering the activation of populist attitudes thesis (Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser, and Andreadis Citation2020), our article tackles these opposing findings by addressing populism simultaneously at the general level (i.e. as a whole) and the level of its core components. We specifically argue that these opposing findings can be in part explained by voters’ interest in specific components of populist ideology. Based on the findings from recent experimental studies indicating such interest (see Castanho Silva, Neuner, and Wratil Citation2022; Neuner and Wratil Citation2020), we assume that individual subdimensions of populist attitudes can have their unique effects on populist support and propose that these unique effects arise from the strong emphasis on the corresponding components of populist ideology in political communication.

When exploring to what extent populist support is driven by subdimensions of populist attitudes rather than populist attitudes as a whole, we also consider their thin nature and thus examine their interplay with thick policy preferences reflecting the host ideology to which populism is attached in a particular context. We integrate diverging findings concerning this interplay (compare Andreadis et al. Citation2019; Loew and Faas Citation2019) and propose that in the conditions of salient populist cleavage, populist attitudes and their subdimensions encourage populist support not only among those who share but also among those who do not (fully) share a populist party’s thick policy preferences.

We apply our assumptions to the context of the 2021 Czech legislative election, particularly to explain electoral support for two main populist parties, ANO and SPD. We expect electoral support for ANO to be driven by populist attitudes, anti-elitism attitudes, and people-centrism, since ANO strongly emphasised anti-elitism and people-centrism in its communication. As SPD also placed a strong emphasis on demands for popular sovereignty, we expect its electoral support to be additionally driven by a belief in popular sovereignty. Given that populism bonded well with nativism in the electoral campaigns of both populist parties, we assume populist attitudes and their subdimensions to shape electoral support for each party among individuals holding strong nativist attitudes. As a result of the salience of populist cleavage within the context of the 2021 election, we, nevertheless, expect populist attitudes and their subdimensions to also contribute to electoral support for each populist party among individuals with weak to moderate nativist attitudes.

To test our hypotheses, we conducted multi-group SEM analyses across nativist attitudes groups on the original public opinion survey data (N = 2009). Our results indicate that populist attitudes, and to some extent their subdimensions, are important predictors of the propensity to vote for both populist parties. The unique effects of subdimensions tend to reflect the emphasis which populist parties place on the corresponding components of populist ideology in their political communication. Furthermore, populist attitudes, and to some extent their subdimensions, operate as both a contingent mechanism and a motivational substitute. However, they do not necessarily perform these roles simultaneously in the propensity to vote for each populist party. While populist attitudes are connected with the propensity to vote for ANO among individuals with weak nativist attitudes, they contribute to the propensity to vote for SPD among individuals holding strong nativist attitudes. Only a belief in popular sovereignty performs the contingent and the motivational role simultaneously, particularly in the propensity to vote for SPD.

The role of populist attitudes in populist support

The recent success of populist parties has resulted in an immense amount of work aiming to identify factors which drive their electoral support (Rooduijn Citation2019). Contributing to these existing endeavours, our article is grounded in the ideational approach which perceives populism as a thin-centred ideology whose ideological core consists of three interrelated parts: anti-elitism, people-centrism, and demands for the restoration of popular sovereignty (Hawkins et al. Citation2019; Mudde Citation2004). Within this approach, we particularly follow the strand of research which argues that populist parties find their support among individuals holding populist attitudes (see e.g. Akkerman, Mudde, and Zaslove Citation2013; Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser, and Andreadis Citation2020).

The proposed relationship between populist attitudes and populist support has, however, been disputed (see Marcos-Marne, Gil de Zúñiga, and Borah Citation2023). For example, in their study of the 2018 Brazilian presidential elections, Castanho Silva, Fuks, and Tamaki (Citation2022) point to the negligible role of populist attitudes in electoral support for the populist far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro. Instead, Bolsonaro’s support derives from extreme right-wing ideological self-placement and illiberal and anti-democratic attitudes. A similar pattern has been observed in Austria (Gründl and Aichholzer Citation2020), Slovakia (Stanley Citation2011), Germany (Neuner and Wratil Citation2020) or in the US (Castanho Silva, Neuner, and Wratil Citation2022). Overall, these studies indicate that populist attitudes may be too thin to provide a solid foundation for populist support.

The unclear role of populist attitudes in populist support has been addressed by the activation of populist attitudes thesis which argues that the mere presence of voters’ populist attitudes does not ensure their salience in voters’ decision-making. In order to translate into votes, these populist worldviews must be activated. Their activation requires a context in which “a conspiring elite exists and the system is not fully responsive to the popular will” (Andreadis et al. Citation2019, 238) so that voters perceive traditional parties as failing to provide strong representation and blame widespread failures of democratic governance on them (Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser, and Andreadis Citation2020). Furthermore, political parties must strongly advocate individual components of populist ideology in their political communication (Andreadis et al. Citation2019; see also Druckman, Jacobs, and Ostermeier Citation2004; Hameleers et al. Citation2021).

The activation of populist attitudes thesis, however, does not suffice to fully explain the unclear role of populist attitudes in populist support. Recent research indicates that the presence of opportune conditions and the strong emphasis on populist ideology may be necessary, but are not sufficient for populist attitudes to play a key role in populist support (Castanho Silva, Neuner, and Wratil Citation2022; Neuner and Wratil Citation2020). Building on these findings, we propose a supplementary explanation for the unclear role of populist attitudes. We specifically argue that their unclear role in part arises from not considering populism simultaneously at the general level (i.e. as a whole) and the level of its core components in explaining populist support, especially at the demand side. Given that populist attitudes are a multi-dimensional concept, measured scores on populist attitudes items include not only variance associated with populist attitudes as a whole (the domain-specific variance) but also subdimension-specific variances. Unless we employ an operationalisation strategy which ensures separation of these variances, and thus allows us to simultaneously evaluate the effect of populist attitudes and the unique effects of their subdimensions, we cannot be sure to what extent any observed effect of populist attitudes reflects the effect of populist attitudes as a whole rather than the effect of some of their subdimensions (see Chen et al. Citation2012).

Addressing the unclear role of populist attitudes by considering populism simultaneously at the general level (i.e. as a whole) and the level of its core components is essential for two more reasons. First, existing research indicates that voters do not give equal weight to individual components of populist ideology in their decision-making (see Castanho Silva, Neuner, and Wratil Citation2022; Neuner and Wratil Citation2020). Voters seem to care not only about populist ideology as the whole package, but also about its components. Accordingly, we assume that individual subdimensions of populist attitudes have their unique effects on populist support.

Second, in their communication, populist parties place an unbalanced emphasis on individual components of populist ideology (e.g. Rooduijn and Pauwels Citation2011; Wiesehomeier Citation2019). We address these empirical variations in populism at the supply side by linking them to the unique effects of subdimensions of populist attitudes on populist support. We specifically argue that the unique effects of individual subdimensions arise from the strong emphasis on the corresponding components of populist ideology in political communication. In this regard, we build on the experimental study conducted by Hameleers et al. (Citation2021) in 15 European countries which reveals that short-term exposure to a single message emphasising a specific component of populist ideology results in the activation of both populist attitudes and the corresponding subdimension. While we acknowledge that short-term exposure may not be sufficient for the salience of populist attitudes and their subdimensions in voters’ decision-making (but see e.g. Richey Citation2012), we argue that repetitive exposure to populist rhetoric over a longer period can bring populist attitudes and their strongly emphasised subdimensions to the fore in voters’ minds. Once highly accessible, populist attitudes and their subdimensions can become salient in voters’ decision-making (Hart Citation2013). Consequently, we propose that:

H1: The stronger an emphasis on a particular component of populist ideology in political communication of a populist party, the stronger the effects of populist attitudes and their corresponding subdimension on electoral support for that party.

Although the proposed logic concerns populist parties, we assume that it applies to non-populist parties as well. Such applicability is essential since some non-populist parties put a long-term emphasis on part of the components of populist ideology (Engler, Pytlas, and Deegan-Krause Citation2019) or adopt full populist rhetoric, for example, when pressured by the success of competing populist parties (Mudde Citation2004; but see Rooduijn, de Lange, and van der Brug Citation2014; see Schwörer Citation2021 for a review). The proposed logic may be used to explain electoral support for a non-populist party in either case. While in the latter case, the logic may operate in the same way as when applied to populist parties, in the former case it may need to be modified. A stronger emphasis on a particular component of populist ideology may not enhance the effect of populist attitudes as a whole but only the effect of their corresponding subdimension.

Overall, for both populist and non-populist parties the proposed logic implies that the unique effects of individual subdimensions of populist attitudes arise from the emphasis on the corresponding components of populist ideology. According to this logic, subdimensions, however, do not necessarily play a stronger role in electoral support for populist parties rather than non-populist parties. In the context where, for example, anti-elite rhetoric is more strongly emphasised by a non-populist party, the proposed logic allows anti-elitism attitudes to have a stronger effect on electoral support for that non-populist party.

In addition to addressing populism simultaneously at both levels, one needs to consider populism’s thin nature when examining electoral support for populist parties. As a thin-centred ideology, populism rarely stands alone (Mudde Citation2004; Stanley Citation2008; but see Učeň Citation2004). It rather interacts with a particular thick (host) ideology which gives meaning to the categories of the people and the elite, otherwise empty signifiers (Laclau Citation2005; see also Moffitt Citation2020). In political communication, populist ideology is woven into, for example, anti-immigration or Eurosceptic positions (e.g. Kriesi Citation2008; Mudde Citation2007a). The resulting weave is reflected at the demand side. Many voters hold both strong thin populist attitudes and strong thick attitudes corresponding to the host ideology to which populism is attached (e.g. Tsatsanis, Andreadis, and Teperoglou Citation2018; Wettstein et al. Citation2020; see also “thin-thick populists” in Neuner and Wratil Citation2020). When examining the role of populist attitudes in populist support, we thus need to consider the interplay between these thin and thick attitudes (see also Hunger and Paxton Citation2021).

In this regard, populist attitudes have been proposed to play two distinct roles in populist support. Given their thin nature, populist attitudes have been assigned the role of a contingent mechanism whose functioning is conditioned by thick policy preferences. Accordingly, populist attitudes drive populist support only when individuals’ thick policy preferences are congruent with those of a populist party. If voters reject the party’s thick policy visions, their populist attitudes do not translate into populist votes (e.g. Castanho Silva, Fuks, and Tamaki Citation2022; Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser, and Andreadis Citation2020; Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Citation2018; see also Marcos-Marne, Gil de Zúñiga, and Borah Citation2023).

Although theoretically compelling, this contingent role of populist attitudes does not always find empirical support (but see Andreadis et al. Citation2019). Results of multiple studies suggest that populist attitudes do not (significantly) contribute to populist support when the congruence requirement is fulfilled. Populist attitudes rather act as a motivational substitute and kick in as an important driver of populist support when the match between voters’ and a party’s thick issue positions is poorer (see e.g. Marcos-Marne, Plaza-Colodro, and Freyburg Citation2020; Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Citation2018). Voters do not even need to partly share a party’s thick policy visions to cast a vote in its favour. Populist attitudes drive populist support even among those who moderately disagree with the party’s thick policy visions (see the results in Loew and Faas Citation2019; see also Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Citation2018).

We integrate these findings and argue that once activated, populist attitudes (their subdimensions included) can act both as a contingent mechanism and a motivational substitute. However, the motivational role is conditioned by the salience of populist cleavage in party competition. The salience of populist cleavage ensures that populist attitudes are at the fore in voters’ minds and thus can be used in their decision-making. If populist cleavage is not salient, voters can perceive other issues as more pressing. Consequently, populist attitudes only perform the contingent role (see e.g. Edwards, Mitchell, and Welch Citation1995).

Performing only the contingent role, however, does not imply that populist attitudes are a secondary predictor of populist support. We argue that populist attitudes are an important predictor of populist support even when they contribute to this support only among those who share a populist party’s thick policy preferences. Given their thin-centred nature, it would be overly ambitious to expect populist attitudes to intrinsically have a stronger effect than thick policy preferences or to shape populist support independently of these preferences. On the other hand, it would be misleading to use the thin-centred nature to treat the effect of populist attitudes among those who share a populist party’s thick policy preferences as less important or negligible compared to the effect of thick policy preferences (but see Art Citation2022). In this regard, our approach represents the middle ground.

Even the contingent role of populist attitudes, however, assumes that populism is attached to a particular host ideology. Recent experimental studies which do not find support for the contingent role of populist attitudes do not seem to fully consider this assumption. Both Neuner and Wratil (Citation2020) as well as Castanho Silva, Neuner, and Wratil (Citation2022) fully address the interplay between populism and the host ideology only at the demand side. While their findings indicate to what extent subgroups of voters with varying levels of thin populist attitudes and thick policy preferences are attracted to a candidate advocating either a thin or a thick populist priority, they do not reveal to what extent these subgroups of voters are attracted to candidates advocating a thin populist priority but holding varying positions on the thick host ideology (or vice versa). While Dai and Kustov (Citation2023) address this issue, they do not consider the interplay between populist attitudes and thick policy preferences, and thus do not even consider that populist attitudes may operate as a contingent mechanism.

The 2021 Czech legislative election as a test case

Our article unpacks the role of populist attitudes and their subdimensions in the 2021 Czech legislative election. We argue that the election embodies an ideal case for such examination due to both opportune conditions for the activation of populist attitudes and the salience of populist cleavage.

Within the context of the election, the country was facing a democratic downswing, partly resulting from the ongoing covid pandemic (Buštíková and Baboš Citation2020; Petrov Citation2020). Around the time of the election, Czech society was marked by a decrease in political trust, growing dissatisfaction with the political situation, and by deepening of the belief that the implemented covid precautions were inefficient (Červenka Citation2021, Citation2022). The context of the 2021 Czech legislative election thus embodied an ideal breeding ground for the activation of populist attitudes (for a comparison, see e.g. Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser, and Andreadis Citation2020; Rico, Guinjoan, and Anduiza Citation2017; Silva and Wratil Citation2021).Footnote1

The election was also characterised by the prominent position of populist cleavage in party competition. In an attempt to defeat populist forces and secure the majority in the Chamber of Deputies, mainstream political parties formed two pre-election coalitions: the Together coalition (the coalition of ODS, TOP 09 and KDU-ČSL) and the Pirates and Mayors coalition (see also Havlík and Lysek Citation2022). Strong criticism of populism was vividly manifested throughout their election campaigns. The Together coalition, for example, created a website with “a generator of unfulfilled promises of Andrej Babiš”, the leader of populist ANO and prime minister at that time, portraying him as a threat to the country, and accusing him of making irresponsible economic policy, deceiving the people and stealing from them (see also Havlík and Kluknavská Citation2022).

This criticism presented populist ANO with countless opportunities to separate itself from the mainstream parties and defame them. It also allowed Babiš to portray himself as an authentic representative and guardian of the ordinary people. Such attempts were apparent especially in a series of campaign spots in which Babiš proclaimed that he would protect the ordinary people and sovereignty of the Czech nation “to the last breath”. Populist appeal was thus a strong element in the political communication of ANO during the election race.Footnote2

The same applies to the populist Freedom and Direct Democracy party (SPD). In its campaigns, the party presented itself as the defender of the Czech nation. While positioning itself as the true voice of the common people, fighting for their interests, SPD accused mainstream parties of sympathising with the EU and acting in the pursuit of their interests (Havlík and Wondreys Citation2021).

Based on the opportune conditions for the activation of populist attitudes and the prominent position of populist cleavage in party competition, we expect that populist attitudes played a key role in populist support in the 2021 election. However, rather than evaluating to what extent populist attitudes contributed to casting a populist over a non-populist vote, we explore their effects on electoral support separately for each of the main populist parties, ANO and SPD. Our main motivation is to consider differences in the emphasis which these parties placed on individual core components of populist ideology in their political communication.

Different shades of populism in Czech politics: the case of ANO and SPD

Populist ideology has been a prominent feature in the political communication of both ANO and SPD. In the 2018 Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey (Meijers and Zaslove Citation2018), SPD scored over 8 on a 0–10 scale in all components of populist ideology but general will (7.9). SPD is the 11th most populist party in the dataset. Its overall populism score (9.12) is comparable to the overall scores of other well-known populist parties such as the Alternative for Germany (9.44) or the Freedom Party of Austria (8.90).

Based on the overall populist score, ANO is less populist than SPD, particularly as a result of its lower emphasis on the demands for popular sovereignty.Footnote3 Despite the lower emphasis on this component of populist ideology, populism constitutes an important attribute in the ANO’s political communication. Its overall populist score (6.75) is similar to that of, for example, the Slovak Ordinary People and Independent Personalities party (7.00) or the United Kingdom Independence Party (6.99), both of which are considered populist parties (see Rooduijn et al. Citation2023).

The differences in the embrace of populist ideology between ANO and SPD indicate that electoral support of each party may be shaped by populist attitudes and their individual subdimensions to a different extent. To specify these effects in the 2021 Czech legislative election, we rely on the 2020–2021 Political Representation, Executives, and Political Parties Survey (Wiesehomeier et al. Citation2022), since this survey includes expert evaluations of the prominence of the core components of populist ideology in political communication of the main political parties gathered a few months before the election.

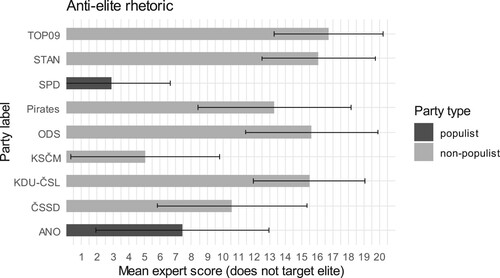

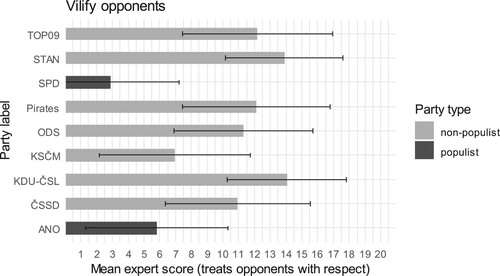

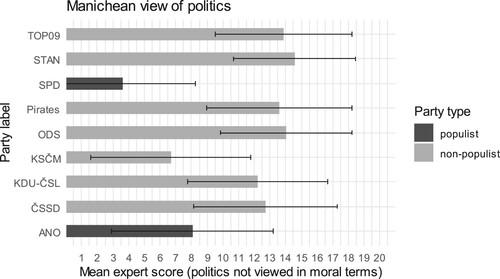

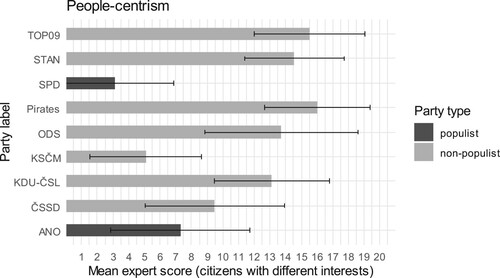

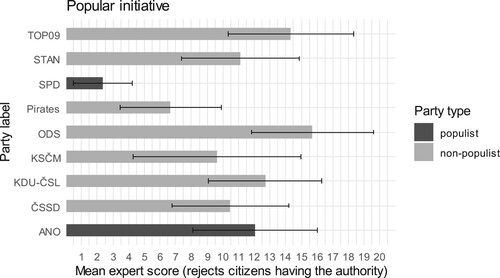

Mean expert scores reveal that the emphasis on populist ideology is significant in the political communication of both ANO and SPD. Each party strongly emphasised all core components of populist ideology directly evaluated in the survey, with anti-elitism and people-centrism receiving slightly more attention than the Manichean view of politics (see ). The demands for popular sovereignty are not directly evaluated in the survey. We argue that these demands are strongly emphasised only by SPD, based on the different positions which the two parties hold on the popular initiative. While SPD strongly supports citizens having the authority to activate a popular vote on laws via the collection of necessary signatures, ANO holds an ambiguous position towards this measure (see ). Accordingly, we expect a belief in popular sovereignty to drive only the electoral support for SPD. Anti-elitism attitudes and perception of the people as a pure and homogenous group (people-centrism), i.e. subdimensions of populist attitudes corresponding to the remaining core components of populist ideology, are expected to drive electoral support for both parties.

Figure 1. The prominence of anti-elite rhetoric in political communication of the main Czech political parties. Experts evaluated the prominence of anti-elite rhetoric on a 1–20 scale (1 = specifically targets elite groups with derogatory rhetoric, discrediting their standing and legitimacy in society, 20 = does not target elite groups with derogatory rhetoric).

Figure 2. The prominence of vilification of opponents in political communication of the main Czech political parties. Experts evaluated the prominence of vilification of opponents on a 1–20 scale (1 = demonizes and vilifies opponents, 20 = treats opponents with respect).

Figure 3. The prominence of the Manichean view of politics in political communication of the main Czech political parties. Experts evaluated the prominence of the Manichean view of politics on a 1–20 scale (1 = treats politics as a moral struggle between good and evil, denying the possibility of natural and justifiable differences of opinion, 20 = does not treat politics in moral terms, but acknowledges the possibility of natural, justifiable differences of opinion).

Figure 4. The prominence of people-centrism in political communication of the main Czech political parties. Experts evaluated the prominence of people-centrism on a 1–20 scale (1 = refers to the common people as an authentic and homogeneous unit, 20 = refers more generally to citizens with their different interests and values). Parties scoring low on this dimension acknowledge that the people have a unified political will, one common interest that should guide all political action.

Figure 5. The position of the main Czech political parties on popular initiative. Experts evaluated the position on popular initiative on a 1–20 scale (1 = strongly supports citizens having the authority to activate a popular vote on laws, enacted or not, via the collection of necessary signatures, 20 = strongly rejects citizens having the authority to activate a popular vote on laws via the collection of necessary signatures).

When specifying the role of populist attitudes and their subdimensions in electoral support for ANO and SPD, we also consider the interplay of populist attitudes and their subdimensions with thick attitudes reflecting the host ideology which these parties combine with populism in their political communication. Within the context of the 2021 Czech legislative election, populism was compatible particularly with nativism (see also Dvořák Citation2022). This bond was well apparent in the political communication of both parties throughout their campaigns. ANO as well as SPD claimed to stand up for the Czech people and to protect them against alien influences, especially (illegal) migrants from non-European countries, particularly countries with large Muslim populations (SPD Citation2021; see also Havlík and Kluknavská Citation2022).

Even though both parties combined populist ideology with nativism, nativism constitutes the core element only in the ideological profile of SPD which has been mobilising on radical right issues for many years. While SPD clearly belongs to the populist radical right party family (see also Rooduijn et al. Citation2023), ANO excels at ideological fluidity (see also Buštíková and Baboš Citation2020). So far, ANO has been described as the technocratic populist party (Buštíková and Guasti Citation2019; Havlík Citation2019) or the centrist populist party (Havlík and Voda Citation2018). In the 2021 election, ANO seemingly shared the populist radical right identity with SPD. Throughout its campaign, ANO claimed to protect the ordinary people against the vision of “the multicultural, ecologically fanatic Pirates-state” (ČTK Citation2021). The combination of populism and nativism, however, merely reflects a strategic decision which smoothly follows the party’s earlier self-seeking pronouncements on minority rights and the Czech nation (see Hanley and Vachudova Citation2018). In the election, ANO opportunistically connected populism with nativism only to defame and weaken its political opponents, particularly the Pirates.Footnote4

Although the populism-nativism union has constituted the identity of each party to a different extent over time (see also Haughton and Deegan-Krause Citation2020), it was prominent in the election campaigns of both ANO and SPD. Consequently, we consider the interplay between populist attitudes and nativist attitudes in electoral support for both parties (see also Dvořák Citation2022). Given the thin-centred nature of populist ideology, we expect nativist attitudes to condition the effect of populist attitudes and their subdimensions on electoral support for both parties. More specifically, we expect populist attitudes and their subdimensions to translate into populist votes among individuals with strong nativist attitudes. Nevertheless, due to the salience of populist cleavage in the election, we expect populist attitudes and their subdimensions to kick in as an important driver of populist support also among individuals with weak to moderate nativist attitudes. Overall, we thus propose that:

H1a: Populist attitudes, anti-elitism attitudes, and people-centrism drive the electoral support for ANO among individuals with all levels of nativist attitudes.

H1b: Populist attitudes, anti-elitism attitudes, a belief in popular sovereignty, and people centrism drive the electoral support for SPD among individuals with all levels of nativist attitudes.

H1c: Populist attitudes and their subdimensions are stronger positive predictors of the electoral support for SPD than the electoral support for ANO.

While the moderate emphasis on individual components of populist ideology in political communication of KSČM may be in part explained by the party’s anti-establishment nature (see Abedi Citation2002, 556–557 for common features of populist and anti-establishment parties), it seems more strongly connected to its far-left nature. KSČM first and foremost challenges economic inequality advocated by the elite as the basis of existing political and social arrangements, and advocates a major redistribution of resources from the elite (Havlík Citation2012; see also Rooduijn et al. Citation2023). KSČM is thus rightly located closer to the populist rather than the pluralist endpoint on individual rating scales designed to measure the prominence of individual components of populist ideology in political communication. Given its far-left nature, its scores on the populist endpoint, however, have a substantially different – non-populist – meaning. Consequently, we cannot clearly link the party’s emphasis on individual components of populist ideology to the unique effects of corresponding subdimensions.Footnote5

As for the remaining non-populist parties, the proposed logic linking the emphasis on individual components of populist ideology to the effect of populist attitudes and the corresponding subdimensions is not clearly applicable to explaining their electoral support either. Their emphasis on pluralism is beyond the scope of the proposed logic. We thus primarily focus on the role of populist attitudes and their subdimensions in the electoral support for the populist parties.

Method

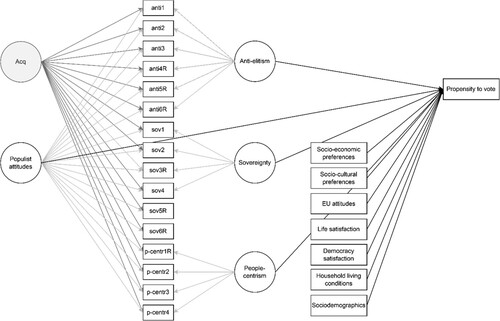

To evaluate the role of populist attitudes and their subdimensions in the electoral support for ANO and SPD within the context of the 2021 Czech legislative election, we use the structural equation modelling (SEM) technique. For each party, we specify a separate full SEM model of electoral support (see ). The two models differ only in the electoral support variable since this variable is party-specific. To address the interplay between populist attitudes and nativist attitudes, we run each of these models across groups with different levels of nativist attitudes. In other words, we conduct two multi-group SEM (MGSEM) analyses with nativist attitudes as the grouping variable. Nativist attitudes are therefore not directly included in the full SEM models of electoral support.

Figure 6. Simplified model specification of the general full SEM model of electoral support. The propensity to vote variable is party-specific. Paths in the measurement model are marked in grey. Paths in the structural model (direct effects on the propensity to vote for a party) are marked in black.

We also specify a model of electoral support for each of the main non-populist parties. These models additionally include nativist attitudes as a predictor of electoral support since non-populist parties did not combine populist ideology or any of its components with nativism in their political communication. When examining the role of populist attitudes and their subdimensions in electoral support for individual non-populist parties, we therefore do not address the interplay between populist attitudes and nativist attitudes.

Even though some of the non-populist parties were part of the pre-election coalitions, we focus on individual parties rather than these coalitions, since these parties sought to maintain their own identities in political communication. To some extent, this translates even to their emphasis on pluralism. Although all these parties strived to defeat populism, they differ in their emphasis on pluralism in individual rating scales, particularly the anti-elite rhetoric scale (see the differences between STAN and Pirates in ) and the popular sovereignty scale (see the differences in the parties’ positions on popular initiative in ).

Data and measurement

We run all SEM analyses on the original data from the second wave of our public opinion survey entitled “Contemporary Political Attitudes of Czech Voters” (N = 2009). The second wave of data collection was conducted in October 2021, shortly after the 2021 Czech legislative election. Data was collected online through a professional survey company. Individuals registered in the Czech National Panel, a commercial online access panel, were invited to complete our online questionnaire using quotas for age, sex, education, region, and settlement size. Respondents with homogeneous answer patterns were dropped from the initial sample. Exclusion of respondents did not significantly distort sample representativeness. Overall, the resulting sample (N = 1886) is representative of the national voting-age population on gender, age, education, settlement size, and region, suffering from only a slight overrepresentation of more educated and older voters (see Appendix for further details).

Measurement of populist attitudes

In the debate concerning the nature of populist attitudes (see e.g. Huber, Jankowski, and Wegscheider Citation2023 for further discussion), our article follows scholars who perceive populist attitudes as comparable to an inherent personality trait (e.g. Busby, Gubler, and Hawkins Citation2019; Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser, and Andreadis Citation2020). More specifically, building on the personality research in psychology (see e.g. Costa and McCrae Citation1995), we consider populist attitudes as a broader trait which contains three facets: anti-elitism attitudes, a belief in popular sovereignty, and perception of the people as a pure and homogenous group (people-centrism).

We thus treat populist attitudes as a compensatory construct. We do not consider individuals as populist only if they simultaneously hold strong anti-elitist views, strongly believe in unrestricted popular sovereignty, and strongly perceive the people as a pure and homogeneous group. We rather acknowledge that there are different ways of being populist. Some may particularly strongly perceive the elite as an evil, untrustworthy homogenous group, pursuing its own interests. Others may particularly strongly believe that the general will should be the absolute principle guiding political decision-making, even to such an extent that they advocate that the most important policy decisions should be made directly by the people.

This compensatory approach to populist attitudes offers a more accurate insight into the match between populist supply and populist demand. It allows us to explore how variations in populism at the individual level match empirical variations in populism among populist parties. More specifically, we can examine to what extent a strong emphasis on particular components of populist ideology in political communication of a populist party translates into the unique effects of the corresponding facets (subdimensions) of populist attitudes on its electoral support.Footnote6

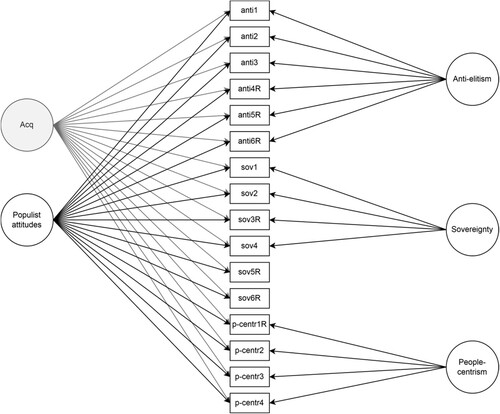

To operationalise populist attitudes as a trait, we employ the reflective measurement model in which observed measures (scores) are perceived as reflections of the unobservable concept (Coltman et al. Citation2008). We specifically employ the bifactor model in which a response to each item proceeds from two separate incentives (factors) – in our case populist attitudes and one of their subdimensions (see ). Even though all factors are uncorrelated, items across subdimensions of populist attitudes are mutually related, since measured scores on each item are, at least to some extent, comprised of the variance associated with populist attitudes (the domain-specific variance).Footnote7

Figure 7. The bifactor model of populist attitudes. Populist attitudes are the general factor. Anti-elitism, Sovereignty and People-centrism are all specific factors. The acquiescence (Acq) factor is the method factor. Manifest scores on each indicator (represented by rectangles) are comprised of variance associated with populist attitudes (domain-specific variance), subdimension-specific variance, residual variance (measurement error) and acquiescence-specific (response-style-specific) variance. The only exceptions are scores on items sov5R and sov6R which do not load on any specific factor. Scores on these items thus do not consist of subdimension-specific variance. These items are augmenting indicators which give meaning to Populist attitudes. Since these indicators capture all subdimensions of populist attitudes, the Populist attitudes factor captures populist attitudes as a whole. Specific factors represent pure subdimensions without contamination from populist attitudes. Anti-elitism captures anti-elitism attitudes. The sovereignty factor captures one’s belief in popular sovereignty. The people-centrism factor captures one’s perception of the people as a pure and homogeneous group. For further details concerning model specification see Figure A.1 in the Appendix.

Given the multi-dimensional nature of populist attitudes, measured scores on populist attitudes items intrinsically include not only the domain-specific variance but also the subdimension-specific variances. Unlike any other commonly adopted operationalisation strategy of multi-dimensional compensatory concepts, the bifactor model ensures the separation of these variances (Chen et al. Citation2012). If the domain-specific variance and subdimension-specific variances remain unseparated, we cannot be sure to what extent any observed effect of populist attitudes reflects the effect of populist attitudes as a whole rather than the effect of some of their subdimensions. The same applies to the effect of individual subdimensions. Unless we separate the two variances, we cannot decide to what extent any observed effect of a particular subdimension reflects the unique effect of that subdimension rather than the effect of populist attitudes as a whole. Separation of the two variances by adopting the bifactor model approach enables us to overcome these limitations, and thus to evaluate to what extent populist attitudes matter in populist support rather than their individual subdimensions (for further explanation see Aichholzer, Danner, and Rammstedt Citation2018; Chen et al. Citation2012; Zhang et al. Citation2020).

Consequently, the bifactor model approach enables us to preclude misinterpretation of the role of populist attitudes in existing research. As a result of employing operationalisation strategies which do not ensure the separation of the domain-specific and the subdimension-specific variances (compare Chen et al. Citation2012; Wuttke, Schimpf, and Schoen Citation2020), the effect of populist attitudes in existing research can be misinterpreted in two ways. The first way assumes that voters care about individual components of populist ideology rather than populism as a whole, and, as a result, populist support is linked to individual subdimensions of populist attitudes (rather than populist attitudes). Consequently, the effect size of populist attitudes on populist support is strongly determined by how many components of populist ideology voters are interested in. Within the context where voters care only about one component, we then likely observe the weak or even null effect of populist attitudes on populist support. On the contrary, when voters are interested in multiple components of populist ideology, populist attitudes may be a more prominent predictor of populist support.

The second way in which the role of populist attitudes can be misinterpreted presumes that voters care about populism as a whole. The effect size of populist attitudes then derives from the proportion of the domain-specific variance to the subdimension-specific variances in measured populist attitudes scores. For populist attitudes to strongly shape populist support, the measured scores need to consist mostly of the domain-specific variance. If voters also care about some component(s) of populist ideology, the variances associated with the corresponding subdimensions can then strengthen the role of populist attitudes (see Chen et al. Citation2012, 227 for further discussion concerning possible misinterpretation of the effect of a core construct).Footnote8 The simultaneous evaluation of the role of populist attitudes and their subdimensions through the bifactor model approach allows to us to address either way of misinterpretation.Footnote9

The battery of populist attitudes employed in our dataset (see ) is based on the ideational approach to populism (Hawkins et al. Citation2019; Mudde Citation2004). It combines items from several existing scales designed to measure populist attitudes, namely from the inventory of populist attitudes (Schulz et al. Citation2018), the scale proposed by Castanho Silva et al. (Citation2019), the scale employed by Oliver and Rahn (Citation2016), and the CSES populist attitudes scale (Hobolt et al. Citation2016). The battery consists of 17 items, with 5 to 6 items per each subdimension. Items capturing anti-elitism attitudes refer to the perception of the political elite as the untrustworthy homogeneous group which pursues its own interest, thus disregarding the needs and demands of the ordinary people. Items designed to measure a belief in popular sovereignty reflect the belief that the general will should be the absolute principle guiding political decisions. In these items, the ordinary people are thus portrayed as fully capable of making political decisions, even directly. Items capturing people-centrism then refer to the perception of the ordinary people as a pure and homogeneous group whose members share the same interests and values (see Appendix for further information).

Table 1. The battery of populist attitudes.

Measurement of nativist attitudes

Nativist attitudes refer to the belief that there is only one official national culture which those who do not belong to the nation need to embrace (Mudde Citation2007a). Whether one is a rightful member of the nation or an immigrant depends on their embrace of the nativist identity. This identity is constructed not only around a shared sense of territory, time and space, but also around native values (George-Betz Citation2017).

Since the 2015 European refugee crisis, non-European origins, particularly Muslim roots, have been used by politicians as the criterion for excluding an individual from the Czech nation (Wondreys Citation2021).Footnote10 Islamic values and cultural practices were deemed as incompatible with the traditional (Christian) values, and thus posed a threat to the Czech identity.Footnote11

To operationalise nativist attitudes, we use items designed to measure immigration attitudes (see e.g. Kokkonen and Linde Citation2023 for the same approach). Even though these items capture both economic and cultural impacts of immigration, they do not contain explicit references to Muslim immigrants. Instead, they refer to immigrants generally or to non-European immigrants. Nonetheless, within the Czech context, these items capture respondents’ nativist attitudes. In response to politicising Muslim immigration and diverting attention away from other immigrant groups inhabiting the Czech territory, the Czech public has associated negative perceptions of immigrants mainly with Muslims (Wondreys Citation2021). We thus take the mean of scores on these items to create the index of nativist attitudes for each respondent, and then use this nativist attitudes index to create the grouping variable for our MGSEM analyses (0 = weak nativist attitudes, 1 = strong nativist attitudes).

Besides populist and nativist attitudes, our full SEM models include socio-economic and socio-cultural preferences as predictors of electoral support, since these are commonly considered important drivers of voting behaviour within the Czech context (Chytilek and Eibl Citation2011; Hloušek and Kopeček Citation2008; Linek and Lyons Citation2013). We also add age, sex, education, and household income, as these are typical control variables in voting behaviour models. Finally, we control for attitudes to the EU, the perceived personal economic hardship, subjective well-being, and satisfaction with democracy, since each of these variables has been linked to the electoral support for the populist (radical right) parties in the existing research (see e.g. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2018; Nowakowski Citation2021; Santana, Zagórski, and Rama Citation2020).

Electoral support is represented in our full SEM models by the propensity to ever vote for a party (0 = hardly likely, 10 = highly likely). This operationalisation strategy allows us to evaluate the role of populist attitudes and their subdimensions in electoral support for ANO and SPD individually, and therefore is convenient for our research goals. Using the vote choice variable to operationalise electoral support would not allow us to empirically test the proposed logic linking the strong emphasis on individual components of populist ideology to the unique effects of corresponding subdimensions of populist attitudes on electoral support. Further details concerning the operationalisation of variables as well as their descriptive statistics are available in Appendix.

Results

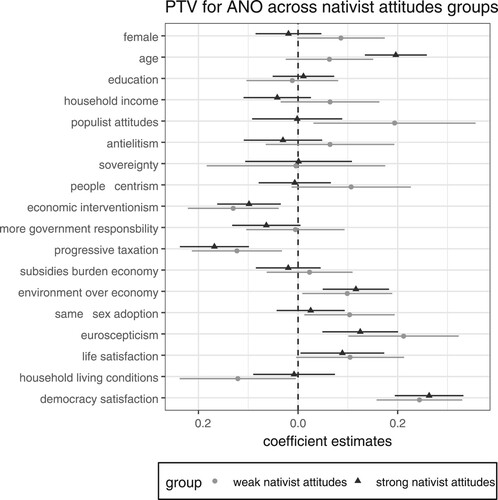

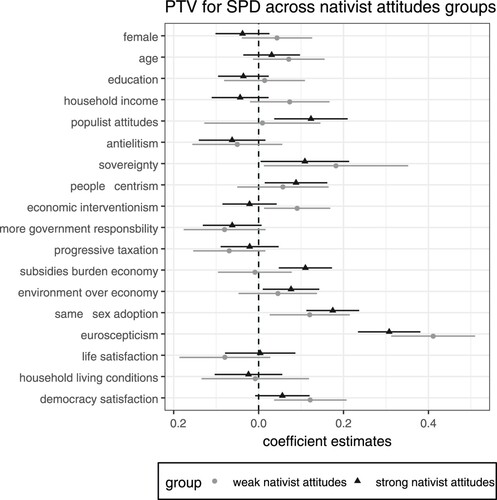

To evaluate the role of populist attitudes and their subdimensions in the propensity to vote for ANO and SPD, we focus on the standardised estimates of regression coefficients from our MGSEM analyses, and compare their values across the nativist attitudes groups (see and ). We proceed to the interpretation of the standardised estimates of regression coefficients despite the poor global fit of both SEM models of electoral support in our data (ANO: χ2(676) = 2158.692, p = .000, SRMR = .088, RMSEA = .057, 90% CI = .055 –.060, TLI = .737, CFI = .763; SPD: χ2(676) = 2154.153, p = .000, SRMR = .090, RMSEA = .057, 90% CI = .055 – .060, TLI = .742, CFI = .767). We do not aim to find the best-fitting model of electoral support for our variables of interest. Instead, our goal is to evaluate the effect of populist attitudes and their subdimensions on the propensity to vote for each populist party using the model commonly employed outside the SEM framework in existing research on populist voting. Our approach within the SEM framework differs only in the operationalisation strategy of populist attitudes. We employ the bifactor model of populist attitudes which allows us to simultaneously evaluate the effect of populist attitudes and the unique effects of their subdimensions on the propensity to vote for each populist party. These unique effects have not been addressed in existing research (compare with Castanho Silva, Fuks, and Tamaki Citation2022; Hieda, Zenkyo, and Nishikawa Citation2021). We thus argue that the interpretation of the standardised estimates of regression coefficients is valuable even in the conditions of the poor global fit, since this interpretation provides insight into the unique effects of subdimensions of populist attitudes in the propensity to vote for populist parties.Footnote12 Footnote13

Figure 8. The dot-and-whisker plot with standardised estimates of regression coefficients from the multi-group SEM analysis of the propensity to vote for ANO with nativist attitudes as the grouping variable

Figure 9. The dot-and-whisker plot with standardised estimates of regression coefficients from the multi-group SEM analysis of the propensity to vote for SPD with nativist attitudes as the grouping variable

In line with the existing research (Castanho Silva, Neuner, and Wratil Citation2022; Neuner and Wratil Citation2020), our results suggest that in their decision-making voters care not only about populist ideology as a whole, but also about some of its core components. Even though none of the subdimensions of populist attitudes has a unique effect on the propensity to vote for ANO, the propensity to vote for SPD is related to a belief in popular sovereignty and people-centrism, specifically among individuals holding strong nativist attitudes. In this nativist attitudes group, a belief in popular sovereignty and people-centrism are equally important predictors of the propensity to vote for SPD as populist attitudes. Furthermore, among individuals with weak nativist attitudes, the propensity to vote for SPD is associated only with a belief in popular sovereignty. Neither populist attitudes nor the remaining subdimensions contribute to the propensity to vote for SPD in this nativist attitudes group.

These patterns, however, provide only partial support for our hypotheses. First, these patterns do not fully correspond to the proposed logic linking the emphasis on individual components of populist ideology in political communication to the unique effects of corresponding subdimensions of populist attitudes. Contrary to our expectations, neither anti-elitism attitudes nor people-centrism are associated with the propensity to vote for ANO (H1a). The unique effects of subdimensions on the propensity to vote for SPD are a better match to our expectations (H1b), with anti-elitism attitudes being the only exception. Subdimensions of populist attitudes are stronger predictors of the propensity to vote for SPD than the propensity to vote for ANO. Contrary to our expectations (H1c), this pattern does not hold for populist attitudes. Based on the effect size, populist attitudes contribute to the propensity to vote for ANO to a similar extent as to the propensity to vote for SPD.

Second, counter to our expectations, populist attitudes and their subdimensions do not act as both a contingent mechanism and a motivational substitute in the propensity to vote for each populist party (H1a, H1b). For each party, populist attitudes operate as an important predictor in a different nativist attitudes group. While populist attitudes are connected with the propensity to vote for ANO among individuals with weak nativist attitudes, they contribute to the propensity to vote for SPD among individuals holding strong nativist attitudes. As to the role of individual subdimensions, subdimensions operate neither as a contingent mechanism nor as a motivational substitute in the propensity to vote for ANO. Nevertheless, they play a much stronger role in the propensity to vote for SPD, particularly a belief in popular sovereignty which is associated with the propensity to vote for the party in both nativist attitudes groups. Within a single context, populist attitudes and their subdimensions can thus act as both a contingent mechanism and a motivational substitute, but not necessarily in the propensity to vote for each populist party (compare with Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Citation2018; and Andreadis et al. Citation2019 who find populist attitudes to act only as the contingent mechanism; see also Loew and Faas Citation2019 for the partial moderating role of populist attitudes).

Considering their thin-centred nature, our results suggest that both populist attitudes and their subdimensions are important factors in to the propensity to vote for populist parties. This applies particularly to the motivational role of populist attitudes in the propensity to vote for ANO and the motivational role of a belief in popular sovereignty in the propensity to vote for SPD, since they contribute to the propensity to vote for the respective party among individuals who reject its thick nativist policy visions but share its position on the state of political representation. Furthermore, these patterns suggest that the linkage between populism and nativism has likely transformed. More specifically, a new subgroup with strong populist and weak nativist attitudes might have emerged within the Czech context (compare with Dvořák Citation2022).

Populist attitudes and their subdimensions are also connected to the propensity to vote for most of the non-populist parties (see Figure A7 and Tables A28 to A34 in Appendix). The negative associations of populist attitudes and anti-elitism attitudes likely reflect the strong emphasis which parties placed on pluralism, resulting in part from their motivation to form pre-election coalitions in an attempt to defeat populist forces. Their willingness to unite and cooperate in order to achieve this goal particularly explains the negative associations of anti-elitism attitudes. These patterns do not apply to the propensity to vote for KSČM. The missing connection between the propensity to vote for the party and both populist attitudes and their subdimensions corresponds to the substantially different meaning of the party’s moderate emphasis on individual components of populist ideology, resulting from its far-left nature.Footnote14

Overall, the patterns in our data support the prominent position of populist cleavage in the 2021 Czech legislative election (see Havlík and Kluknavská Citation2022). Even though populism does not undermine the role of policy issues in voters’ decision-making, considering populism’s thin-centred nature, its role is notable. In this regard, our results do not match the findings of Havlík and Lysek (Citation2022) which indicate the negligible role of populist attitudes in the 2021 election. While the authors’ findings may in part arise from using the vote choice (rather than the propensity to vote for a party) as the dependent variable, the negligible role of populist attitudes is likely connected mainly to capturing populist attitudes only through a belief in popular sovereignty and not considering their interplay with nativist attitudes. Given their thin-centred nature, examining the effect of populist attitudes on populist support without considering their interplay with thick policy preferences can conceal their intrinsic role as a contingent mechanism.

Discussion

Existing research disputes the role of populist attitudes as a key driver of populist support (see Castanho Silva, Fuks, and Tamaki Citation2022). Building on the results from experimental studies which indicate that voters care not only about populist ideology as a whole but also about some of its core components (Castanho Silva, Neuner, and Wratil Citation2022; Neuner and Wratil Citation2020), we address the opposing findings concerning the role of populist attitudes by approaching populism simultaneously at the general level (i.e. as a whole) and the level of its core components. More specifically, we link the strong emphasis on individual components of populist ideology to the unique effects of corresponding subdimensions of populist attitudes on populist support, and evaluate to what extent populist attitudes matter to populist support compared to their subdimensions within the context of the 2021 Czech legislative election.

Given the thin nature of populist ideology, we acknowledge that the effect of populist attitudes and the unique effects of their subdimensions are conditional upon holding thick ideological beliefs corresponding to the host ideology to which populism is attached (see also Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Citation2018). Consequently, when evaluating the role of populist attitudes and their subdimensions in populist support we consider their interplay with nativist attitudes. We argue that as a result of the salience of populist cleavage within the 2021 election, populist attitudes and their subdimensions do not act only as a contingent mechanism. They also operate as a motivational substitute and contribute to populist support even among individuals who reject thick nativist visions advocated by populist parties.

Our results suggest that populist attitudes and their subdimensions are important predictors of electoral support. Populist attitudes, and to some extent their subdimensions, are related to the propensity to vote for populist as well as non-populist parties. The thin-centred nature of populist attitudes thus does not necessarily translate into their negligible role in populist support (but see Art Citation2022). Given the unique effects of subdimensions in our data, the missing connection between populist attitudes and populist support in several studies (see Marcos-Marne, Gil de Zúñiga, and Borah Citation2023 for a review) may be partly explained by the absence of the simultaneous consideration of the effect of populist attitudes and the unique effects of their subdimensions. Due to their multi-dimensional nature, consideration of populist attitudes merely as a whole can lead to misinterpretation of their effect (see Chen et al. Citation2012, 227).

The unique effects of subdimensions in our data match the findings from previous experimental studies indicating that voters care about components of populist ideology (see Castanho Silva, Neuner, and Wratil Citation2022; Neuner and Wratil Citation2020). Even though subdimensions do not seem to take primacy over populist attitudes in voters’ minds, in terms of the effect size, a belief in popular sovereignty and people-centrism contribute to the propensity to vote for SPD to a similar extent as populist attitudes. Furthermore, among individuals holding weak nativist attitudes, the propensity to vote for SPD is associated only with a belief in popular sovereignty. Although the propensity to vote for ANO seems unaffected by either of the subdimensions in our data, consideration of their unique effects is essential when explaining populist support as they can matter in populist support.

Nevertheless, future research needs to explore which factors contribute to the effect of subdimensions on populist support. While strong emphasis on a particular component of populist ideology in political communication may activate the corresponding subdimension of populist attitudes (Hameleers et al. Citation2021), it does not necessarily ensure its effect on populist support, not even within a context embodying an ideal breeding ground for the activation of populist attitudes (compare with Andreadis et al. Citation2019). Our results thus provide only partial support for the proposed logic linking the strong emphasis on specific components of populist ideology to the unique effects of the corresponding subdimensions on populist support. This logic does not hold especially for anti-elitism attitudes. Even though anti-elite rhetoric was prominent in the political communication of both ANO and SPD, anti-elitism attitudes do not contribute to the propensity to vote for either of them.

The absence of the unique effect of anti-elitism attitudes on populist support may be connected to the way these attitudes are measured in our dataset. In items designed to capture anti-elitism attitudes, the elite is defined only in political terms, specifically as MPs in parliament, the political elites or politicians. As both ANO and SPD have been holding seats in the Chamber of Deputies since the 2013 Czech legislative election, voters may perceive these parties as part of the political elite. In other words, when asked to evaluate whether the political elite cares about the ordinary people or is trustworthy, voters may think of ANO and/or SPD as the political elite. They may not associate the political elite solely with the mainstream non-populist parties which ANO and SPD blame for losing touch with ordinary people and acting in their own interests. Negative effect signs of anti-elitism attitudes support this reasoning and indicate that anti-elitism attitudes may be inadequately captured by items in our dataset (see also Jungkunz, Fahey, and Hino Citation2021).

Future research should address this issue and propose new ways to capture anti-elitism attitudes among voters of populist parties in government or with parliamentary representation. It may prove useful to replace references to MPs in parliament, the political elites or politicians in existing items with references to specific non-populist parties which are considered the elite in political communication of populist parties. In addressing this issue, we should not completely divert our attention from the political elites to other groups which fit the elite category in populist rhetoric, for example, the media or the EU. Consideration of certain groups in designing new items may not be feasible if one aims to capture anti-elitist attitudes independently of the host ideology.

The absence of the unique effect of anti-elitism attitudes on the propensity to vote for ANO can be also explained by the considerably lower emphasis which ANO placed on anti-elite rhetoric in its political communication compared to SPD, rather than by altering the frame of the corrupt elite from the domestic to the outside actors (see Balta, Kaltwasser, and Yagci Citation2022), since ANO strongly targeted and distanced itself from the domestic political elite even while in government. The same applies to the remaining subdimensions of populist attitudes. Consequently, the absence of the unique effects of subdimensions on the propensity to vote for ANO does not fully contradict the proposed linkage between the unique effects of subdimensions and the emphasis on the corresponding components of populist ideology in political communication. These patterns rather suggest that the association between the emphasis on individual components of populist ideology and the effect of corresponding subdimensions on populist support may not be linear. A certain degree of emphasis may be essential for subdimensions to contribute to populist support. Future research needs to explore how strongly a component of populist ideology needs to be emphasised for the corresponding subdimension to have the unique effect on populist support.

We should also explore whether the proposed relationship between the emphasis on individual components of populist ideology and the effect of the corresponding subdimensions on populist support is conditioned by the stability of this emphasis. This issue is particularly relevant since some parties do not employ populist ideology across multiple elections (Bonikowski and Gidron Citation2016) or alter their degree of populism in response to contextual incentives (Breyer Citation2023). Some mainstream non-populist parties may even strategically adopt populist rhetoric prior to the upcoming elections (Urbinati Citation2019, 117; see Schwörer Citation2021 for a review; see also Dai and Kustov Citation2022). Consequently, we need to explore whether a short-term and/or unstable emphasis on populist rhetoric suffices for populist attitudes and their subdimensions to shape electoral support, or whether a long-term emphasis is required. In this regard, it is necessary to consider whether, in a particular context, a populist party has already secured parliamentary representation, even though the presence of a significant populist party is not necessary for a non-populist party to adopt populist rhetoric (Mudde Citation2013, 9). While in the context with a successful populist party the long-term emphasis may be required for populist attitudes and their subdimensions to translate into votes, in the context without a successful populist party the short-term emphasis on populist ideology may suffice.

Future research also needs to explore when populist attitudes and their subdimensions act as a contingent mechanism and/or a motivational substitute. Our results suggest that the salience of populist cleavage is only one piece to this puzzle, as it does not ensure that populist attitudes and their subdimensions contribute to the propensity to vote for both populist parties among those who reject their thick nativist visions. Populist attitudes, and to some extent their subdimensions, perform different roles in the propensity to vote for each party. In the propensity to vote for ANO, populist attitudes act as the motivational substitute since they contribute to the propensity to vote for the party among individuals holding weak nativist attitudes. On the contrary, in the propensity to vote for SPD, populist attitudes, and to some extent their subdimensions, operate as the contingent mechanism, contributing to the propensity to vote for the party among individuals with strong nativist attitudes. Only a belief in popular sovereignty performs both roles in the propensity to vote for SPD.

This division of roles of populist attitudes and their subdimensions between the two populist parties may in part arise from the different stability each populist party has assigned to the host ideology in its political communication (Buštíková and Baboš Citation2020; Haughton and Deegan-Krause Citation2020). While SPD has attached populism to nativism since its establishment, ANO has freely combined populism with different host ideologies. Consequently, populist attitudes and in part their subdimensions contribute to the propensity to vote for SPD among individuals holding strong nativist attitudes, whereas in the propensity to vote for ANO populist attitudes matter among individuals with weak nativist attitudes. However, the coherence and stability of the host ideology may prove secondary to the salience of populist cleavage in a context with only one relevant populist party. Furthermore, in a context with multiple relevant populist parties, the coherence and stability of the host ideology may matter only if populist parties share the same host ideology. Within the German context, populist attitudes act as the partial motivational substitute in the electoral support for both the populist far-left Die Linke and the populist far-right Alternative für Deutschland (see Loew and Faas Citation2019).

Future research addressing the interplay between populist attitudes and thick ideological beliefs should also differentiate between the levels of thick ideological beliefs in a more nuanced manner. One of the key limitations of our findings arises from examining the effect of populist attitudes and their subdimensions in only two nativist attitudes groups. When creating these nativist attitudes groups, we merged voters holding moderate nativist attitudes with voters holding either weak or strong nativist attitudes. Since most people in the weak nativist attitudes group hold moderate rather than weak nativist attitudes, it remains unclear whether populist attitudes act as a motivational substitute in the propensity to vote for ANO even among individuals with weak nativist attitudes. Creating a separate group for individuals with weak nativist attitudes would allow us to better evaluate the scope of the motivational role of populist attitudes.

Furthermore, future research addressing the role of populist attitudes in populist support would benefit from experimental design over utilising cross-sectional survey data, since such data provide only limited insight into the causal effects of populist attitudes on populist support. Unlike existing experimental research (Castanho Silva, Neuner, and Wratil Citation2022; Dai and Kustov Citation2023; Neuner and Wratil Citation2020), future experimental studies need to address the interplay between populism and the host ideology at both the demand and the supply side. Additionally, they need to embrace the unique effects of individual subdimensions of populist attitudes and examine the link between these effects and the emphasis on individual components of populist ideology in political communication. To evaluate how populist demand matches with populist supply, populism among voters and political parties (or candidates) needs to be approached at the same level.

Nonetheless, focusing solely on thin populist attitudes and thick ideological beliefs does not suffice to explain populist support. Even our results indicate that the propensity to vote for each populist party is connected to other factors, particularly voters’ Euroscepticism. In explaining populist support, future research thus needs to consider alternative explanations which are not specific to populist parties. Given the increasing personalisation of politics (e.g. Garzia, da Silva, and De Angelis Citation2022), the effect of party leaders may be of particular research interest. Even though the role of party leaders in populist support has been explored (e.g. van der Brug and Mughan Citation2007; Gyárfášová and Hlatky Citation2023; Michel et al. Citation2020), we have yet to learn to what extent populist attitudes and thick policy preferences matter in populist support compared to evaluations of party leaders’ traits.

Despite its limitations, our article contributes to the existing research on populist voting in two ways. First, it introduces a novel approach for exploring the match between populist supply and populist demand which tackles the unclear role of populist attitudes in populist support (see Marcos-Marne, Gil de Zúñiga, and Borah Citation2023 for a review) by simultaneously addressing populism at the general level (i.e. as a whole) and the level of its core components. The proposed approach interconnects existing research indicating voters’ interest in individual components of populist ideology (Castanho Silva, Neuner, and Wratil Citation2022; Neuner and Wratil Citation2020) with studies emphasising empirical variations in populism among populist parties (e.g. Rooduijn and Pauwels Citation2011; Wiesehomeier Citation2019), specifically by linking the strong emphasis on individual components of populist ideology in political communication of these parties to the unique effects of the corresponding subdimensions of populist attitudes on their support. Second, our article demonstrates that within a single context populist attitudes, and to some extent their subdimensions, can operate as both a contingent mechanism and a motivational substitute, but not necessarily in propensity to vote for each populist party. The salience of populist cleavage thus does not suffice for populist attitudes and their subdimensions to contribute to the propensity to vote for a populist party among those who do not share its thick policy preferences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Veronika Dostálová

Veronika Dostálová is a PhD candidate at the Department of Political Science, Masaryk University, Brno. She addresses the role of populism in political behaviour. She has co-authored two book chapters on the 2017 Czech legislative election. In 2021 Veronika was the principal investigator of the grant project “Who is the Czech populist citizen?”, supported by the Internal Grant Agency of Masaryk University. As a successful AKTION scholarship holder, she has completed a short-term research stay at the University of Vienna, focusing on the measurement invariance of populist attitudes. From March to June 2022 she was a visiting researcher at the Department of Communication, University of Vienna.

Vlastimil Havlík

Vlastimil Havlík is an Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science, Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University, Brno. He was a Fulbright-Masaryk Visiting Scholar at Northwestern University, United States (2017–2018). His main research and teaching focus include populism and political parties in Central and Eastern Europe. He regularly publishes texts dealing with these issues (e.g. in East European Politics and Societies, Communist and Post-Communist Studies or Problems of Post-Communism). He also wrote or edited several books focusing mostly on Czech politics and populism. Vlastimil Havlík is also the Editor in Chief of the Czech Journal of Political Science.

Notes

1 This democratic downswing was not an isolated incident. For many years, Czech politics had been facing unstable, ideologically heterogeneous and ineffective coalition governments while witnessing numerous corruption scandals. The resulting widespread failures of democratic governance (easily attributable to elite behaviour) had significantly deepened people’s distrust in mainstream political parties and party politics (Balík et al. Citation2017; Hanley Citation2012b; Havlík and Voda Citation2016). The Czech context had, therefore, embodied an ideal breeding ground for the activation of populist attitudes for a long time before the election.

2 By grounding the division between the people and the elite in moral foundations, ANO managed to keep anti-establishment discourse even while in government, and thus to distance itself from the political elite. The case of ANO demonstrates that entering the government does not necessarily entail losing the populist appeal (see also Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2017, 12).

3 ANO’s lower emphasis on the demands for popular sovereignty (5.36) is related to the party’s technocratic nature at the time of data collection. As a result of combining populism with technocracy, ANO did not strongly sympathize with the idea that the ordinary people, not the elite, should have the final say in politics. Instead, it advocated a government of experts whose expert solutions should benefit the ordinary people (Buštíková and Guasti Citation2019).

4 During the parliamentary term preceding the 2021 election, ANO experienced a strategic shift not only in its stance on socio-cultural, but also socio-economic issues. While in 2014 ANO scored 6.35 on the general left-right socio-economic scale (0 = extreme left, 10 = extreme right) in the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Jolly et al. Citation2022), in 2019 experts perceived its position on socio-economic issues to be closer to the extreme-left endpoint (4.5, Jolly et al. Citation2022). Based on the lack of a coherent host ideology and the controlling role of its leader and successful economic entrepreneur, Andrej Babiš, over its structure, ANO is best described as the entrepreneurial populist party (see also Hloušek, Kopeček, and Vodová Citation2020; Saxonberg and Heinisch Citation2022).

5 Note that in the 2018 Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey (Meijers and Zaslove Citation2018), which does not employ the pluralist endpoint, ANO and KSČM swap places. ANO scores a win on almost all components of populist ideology. The only exception is the component concerning popular sovereignty on which the parties tie. These patterns further support the non-populist nature of the political communication of KSČM.

6 The competing non-compensatory approach to populist attitudes does not enable consideration of these unique effects. Furthermore, this approach does not allow populist attitudes to be viewed as a trait. Their non-compensatory nature implies that populist attitudes do not exist as an independent entity, but are rather defined by the simultaneous presence of their constituent components – anti-elitism attitudes, a belief in popular sovereignty, and people-centrism. An individual cannot be considered populist when their anti-elitist orientations are low, even if they simultaneously strongly demand popular sovereignty and perceive that the ordinary people are of a good and honest character (Wuttke, Schimpf, and Schoen Citation2020). Populist attitudes thus merely represent high scores on all of its constituent components.

7 Modelling all factors as uncorrelated does not contradict the perception of populist attitudes as a multi-dimensional compensatory construct. The bifactor model is a suitable approach for representing general constructs comprised of several highly related subdimensions (see Chen, West, and Sousa Citation2006). The orthogonality of all factors within the bifactor approach is essential for the evaluation of the effects of individual subdimensions (respective regression coefficients) as the unique contributions of individual subdimensions (see Zhang et al. Citation2020).

8 The proportion of the domain-specific variance to the subdimension-specific variances in the measured populist attitudes scores impacts the effect of populist attitudes even when voters care only about individual components of populist ideology. If measured scores consist mostly of the domain specific-variance, the effect of populist attitudes will likely be weak, even when voters care about more components of populist ideology. In this case, the predominance of the domain-specific variance conceals the effect of subdimensions of populist attitudes and manifests itself as the weak to null effect of populist attitudes.