ABSTRACT

Graphic design is a specialized form of creative practice in which images, typography, texts, shapes and other visual elements are created, selected, developed and integrated to form a coherent whole that conveys an intended message and user experience. Anecdotal evidence suggests that intuition is critical in this practice, but exactly how graphic designers rely on their intuition to support their creative design process is poorly understood. Using cultural probes and semi-structured interviews, this qualitative study evidences how twelve professional graphic designers relied on intuition as what we will call an ephemeral facility. Intuition was discerned as a feeling that briefly enters into consciousness and reinforces ongoing, nonconscious decision making, or causes a shift toward conscious reasoning strategies. The study reports how the graphic designers applied intuition throughout their creative design process––for obtaining and selecting information from clients, filling in informational gaps, envisioning a starting point and guiding subsequent actions and evaluations necessary for developing the design. This offers new empirically based insight into the role and relevance of intuition for progressing the creative graphic design process, including the social and material interactions therein.

1. Introduction

Graphic design is a broad domain in the creative industries (Alhajri, Citation2017) and includes tasks such as developing corporate visual identities (CVIs), analogue and digital media content for marketing and educational purposes, and signage for wayfinding. Historically, graphic design is closely linked to printing (Drucker & McVarish, Citation2009). Recent decades have seen a dramatic increase in ‘the vast and ever-increasing content on the Internet’ (Meggs & Purvis, Citation2012, p. 550), and although

the tools of design are changing with the advance of technology, [the] essence of graphic design, however, remains unchanged. That essence is to give order to information, form to ideas, and expression and feeling to artifacts that document human experience. (p. 572)

Graphic designers create, select, develop and integrate many types of elements, e.g. images, typography and interactive media to form a coherent whole that can convey an intended message and user experience (Alhajri, Citation2017). Anecdotal evidence suggests that intuition is critical in this practice, but exactly how graphic designers rely on intuition to support their creative design process is poorly understood (Darwich, Citation2016).

According to Luke Carson of Australian design studio Design by Bird, intuition ‘presents a non-rational pull prompting us to follow a particular path, explore a seemingly-incongruous idea, or form a surprising conclusion’. Graphic designers must ‘hand over the reins, trust our experience, and be led willingly wherever intuition takes us’ to ‘arrive at an unexpected but entirely meaningful conclusion’ (Carson, Citation2017, n.p.). Designer Daniel van der Velden of Dutch design studio Metahaven has a similar view: ‘intuition plays an important role in everything aesthetic and beautiful. As well as in anything political. The most important things in design are decided in a split second. Without any justification’ (The politics of aesthetics: What does it mean to design?, Citation2011).

This paper moves beyond such anecdotal evidence by presenting a qualitative study that contributes insight into how professional graphic designers rely on intuition as what we will call an ephemeral facility: A subjective, gradual, momentary experience of sensing a solution, at the frontier of consciousness and unconsciousness. We nuance this preliminary definition below. We first present related work on the creative process in graphic design and the conceptual complexity of intuition herein. We then introduce our method and results and consider suggestions for future design research on intuition.

2. Background

2.1. The creative process in graphic design

Graphic design can be seen as a specialized form of creative problem solving (Nini, Citation2006). Research into creative processes in graphic design is limited. The arguably most comprehensive graphic design process model was developed by Nini (Citation2006) and contains two phases. First, Investigation and Planning involves gathering and analyzing information and user needs. Criteria are formulated to develop visual design strategies toward a design solution, thereby setting the design constraints and scoping the project. Second, Development & User Testing, consists of an iterative process where visual design concepts such as typography, images, colors, layouts and signage elements are selected and processed to develop potential graphic design solutions to be tested in-the-wild and refined until the design solution is mature enough for the client and users to accept it. Although Nini’s (Citation2006) model might seem similar to other design process models (see e.g. Roozenburg & Cross, Citation1991), its domain focus makes it relevant as a guiding matrix for examining the role of intuition in the creative process of graphic designers.

2.2. Defining intuiting and intuition

Etymologically, intuition stems from the Latin intueri––to contemplate or look inside (Sadler-Smith, Citation2007). Intuition is different from insight, i.e. the successful result of a mainly logical thinking process that can be accounted for (Dane & Pratt, Citation2007) and denotes a ‘sudden and unexpected apprehension of the solution by recombining the single elements of a problem’ (Zander et al., Citation2016, p. 1). Intuition must also be distinguished from instinct, meaning the innate ability to automatically respond to stimuli to maximize chances of survival (Dane & Pratt, Citation2007). The present study assumes intuition to be both a process (intuiting) and an outcome (an intuition) (Dane & Pratt, Citation2007; Dörfler & Ackermann, Citation2012). Intuiting is an often-nonconscious thinking process that is rapid, spontaneous and alogical and concerned with a given situation as a whole (Dane & Pratt, Citation2007; Dörfler & Ackermann, Citation2012), where information from the environment is linked together (Raidl & Lubart, Citation2001). This information might come from external stimuli (e.g. surroundings, sounds), memory (e.g. knowledge, experiences) or subconscious concerns and emotions. As this synthesis reaches completion, an intuition occurs, experienced as a brief positive feeling (Dörfler & Ackermann, Citation2012; Faste, Citation2017). This brevity of intuition is central. Neuroscientific research has shown that neural activity predicting voluntary movement can be discerned as much as ten seconds before a person becomes aware of an urge to move, and, further, that the prefrontal cortex can affect behavior in response to clues that do not appear in consciousness (Isenman, Citation2018, p. xiii). Intuitive cognition is thus critical in decision making (Patterson & Eggleston, Citation2017).

Many definitions of intuition have been suggested (see e.g. Dane & Pratt, Citation2007, p. 35), often through typologies rather than by one clear definition. Raidl and Lubart (Citation2001) differentiated between socio-affective intuition (sensitivity toward understanding another person or situation), applied intuition (directed toward a problem solution) and free intuition (a feeling of foreboding concerning the future). Although Dane and Pratt (Citation2007) argued for intuition as a ‘relatively homogenous concept’ (p. 47), they identified three related kinds, or rather facets, of intuition––problem-solving, moral and creative intuition. Sinclair (Citation2010) drew a distinction between intuitive expertise (using domain-specific knowledge from accrued expertise), intuitive creation (holistic information processing that combines disparate patterns in a new, associative way) and intuitive foresight (sensing opportunities or risks hidden to others). Despite minor differences across these typologies, they generally agree that intuition cannot arise without the process of intuiting (Dijksterhuis & Nordgren, Citation2006), and that intuiting and intuition are characterized by clear individual differences (Policastro, Citation1995). Scholars also agree that intuition entails a ‘feeling of knowing without knowing how or why’ (e.g. Dörfler & Ackermann, Citation2012; Raidl & Lubart, Citation2001). The consensus seems to be that intuition is ‘reached with little apparent effort, and typically without conscious awareness, [and tends to] involve little or no conscious deliberation’ (Hogarth, Citation2001, p. 14, original emphasis) with the addition that speed, holistic experience, learning and certainty are also relevant for conceptualizing intuition (Hogarth, Citation2001).

2.3. Intuition in graphic design

Intuition has seen a rejuvenation as a research topic after having been associated with fringe science-like studies. Although several methods for studying intuition have been proposed (Sinclair, Citation2014), intuition in creativity might be the least studied area (Dörfler & Ackermann, Citation2012). As opposed to other creative domains such as industrial design (Faste, Citation2017), haute cuisine (Stierand & Dörfler, Citation2015) and architecture (Çizgen & Uraz, Citation2019), research on intuition in graphic design is limited (Darwich, Citation2016). In addition, it is often studied indirectly as part of heuristics and design fixation (Kannengiesser & Gero, Citation2019) and (other) non-conscious influences on design (Badke-Schaub & Eris, Citation2014).

This is surprising for two reasons. First, the importance of intuition in graphic design is established. Waller (Citation1980) observed how graphic designers often select typography based on intuition, reflecting the above testimonials (Carson, Citation2017; The politics of aesthetics: What does it mean to design?, Citation2011). Second, as Nini’s (Citation2006) process model suggests, graphic design entails many creative choices that affect the user experience of all the products and services we rely on every day. Such choices range from overall strategic deliberations on a design’s impact on a user group, to fastidious choices about hues, font types and sizes. Since no definitive answers exist to questions such as whether one should choose Arial font size 24 over 25 for a website headline, intuition necessarily informs such decision making.

This essential ‘openness to extra-rational modes of thinking’ (Faste, Citation2017, p. 3404) among graphic designers has prompted the criticism that they ‘work intuitively, without knowing their audience’ (Taffe & Barnes, Citation2010, p. 211). One reason for this alleged tendency, is graphic designers’ strong disciplinary affinity with Art and Esthetics, which, the argument goes, might inadvertently cause graphic designers to work overly intuitively to fulfil a client’s goals. Involving non-designers such as the client or end users in the design process might assumingly lead to a mediocre design (Drucker & McVarish, Citation2009). This argued professional inclination entails that the process of graphic design still seems somewhat shrouded in (self-imposed) mystery. This invites anecdotal evidence about how graphic designers make creative choices purely based on (esoteric) expert intuition. This situation might not change until graphic designers overcome the ‘fear that sharing will “give away” some perceived competitive edge’ (Frascara, Citation2004, p. 60). In response, Taffe (Citation2017) found that co-designing with end users can yield more creative solutions if graphic designers relinquish creative control while still relying firmly on their intuition during the creative process.

Nowadays, it seems unlikely that graphic designers would be reluctant to share the details of their creative process. Intuition is invaluable (Bennett, Citation2006) for graphic designers, but they have abandoned the idea of ‘relying solely on their intuition’ (p. 17). How, then, might graphic designers be cognizant of the intuitive practices they rely on in their creative process? Attempting to answer such questions will advance the academic and professional design communities’ understanding of design creativity and enable continued development of theory, methods and tools to support graphic designers. This qualitative study therefore poses this research question: How do graphic designers rely on intuition in their creative process?

3. Method

3.1. Participants

Twelve Dutch professional graphic designers participated in the study (age = 21–61; six self-identified as females, six as males). The sample consisted of three junior (one-two years of experience), three medior (three-five years) and six senior designers (five+ years). Ten had a university degree, two a vocational degree in graphic design. Their work included developing corporate visual identities (logo, typeface, imagery and assets, brand guidelines), campaigns (websites, social media advertisements, audio-visual materials, posters, brochures) and publications (books, magazines, presentations). All were recruited using purposive sampling. The study was approved by the Ethics and Data Management committee of the Tilburg School of Humanities and Digital Sciences, Tilburg University, the Netherlands.

3.2. A dual-method approach

Most research on intuition relies on different qualitative techniques such as in-depth interviews and content analysis (Faste, Citation2017), because intuition is often nonconscious and ”inexpressible in words or other symbols” (Dörfler & Ackermann, Citation2012, p. 556). We therefore devised a dual-method approach: A cultural probe package and individual semi-structured interviews developed based on Visser et al. (Citation2005). All materials are available online via the study’s Open Science Framework (OSF) website.Footnote1

3.2.1. Cultural probe package

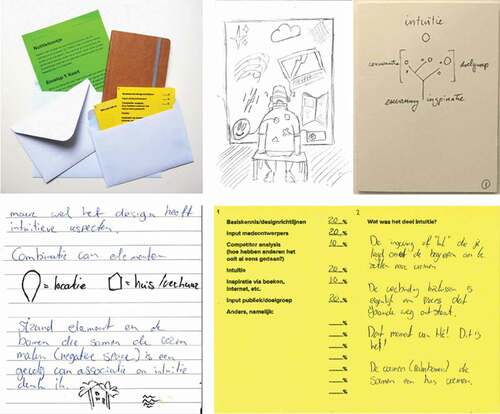

The cultural probe package comprised of three small assignments to be done by the participants. This was developed to help participants think about what intuition means to them and how it affected their day-to-day graphic design work (Visser et al., Citation2005). The cultural probe package consisted of a leaflet with instructions and three cultural probes: A postcard, a notebook and a yellow percentages leaflet (see ).

Figure 1. Cultural probe package (1 (a)). Examples of postcard (P09, P08) (1 (b)), notebook entry (P09) (1 (c)), percentages leaflet (P09) (1 (d))

The primary purpose of the cultural probe package was to prepare participants for the semi-structured interviews. Cultural probes have successfully been deployed to sensitize participants to their nonconscious behaviors with the goal of supporting subsequent data collection using interview techniques (Visser et al., Citation2005). Intuition, and especially intuiting, is largely nonconscious (Dörfler & Ackermann, Citation2012). Sensitization before an interview thus supports the elicitation of a sufficiently rich data set during a later interview. The secondary purpose of the package was to support explanation and interpretation during the subsequent interviews (see below).

The cultural probe package was deployed approximately one week before the interview, and participants were free to choose themselves when to do each assignment within that week. Deployment within a single week was chosen to strike a balance between providing our professional participants with sufficient flexibility to do the assignments when it suited them, while ensuring that their memories were still fresh enough to support the interview, but also to prevent attrition that may result from long(er) deployment periods.

3.2.1.1. Postcard

To sensitize participants to their own understanding of intuition, a blank postcard was provided, instructing participants to explain to a graphic design student their view on intuition, using the front of the postcard for a visualization and the back for a supplementary explanation (). This cultural probe item lent itself well to sketching and drawing (Schenk, Citation1991), and was executed first to induce reflection and support the construct validity of the subsequent probes and semi-structured interview.

3.2.1.2. Notebook

To sensitize the participants to when and how intuition would occur in their work, a notebook was offered with the instruction to make a note to try to explain when, why and how intuition occurred (). The participants were free to put as much effort into this as they wanted throughout the week. This approach was intended to support the descriptive validity of the subsequent semi-structured interviews.

3.2.1.3. Percentages

To sensitize the participants to the degree that intuition played in their creative design process, a yellow two-page leaflet was provided on which participants could assign percentages (in sum, 100%) to sources of information that had informed their graphic design process and the importance of intuition (). In addition to intuition, input from colleagues, competitor analysis, inspirational materials and input target group could be added, as could other sources of information. The probe could be executed at any moment. This probe was designed to support the descriptive validity of the subsequent semi-structured interview.

3.2.2. Semi-structured interviews

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted to capture a sufficiently rich data set to suit the exploratory nature of the study and enable high ecological validity (Wengraf, Citation2001). Each interview started with the collection of socio-demographic information, i.e. age, self-identified gender, education, work experience, expertise and use of tools, and then addressed graphic design, design creativity and intuition as well as the interrelatedness of these three themes. Participants were encouraged to use the cultural probes and examples of their work to aid their explanations. What information was shared was up to the participants, so not all of the cultural probes were reviewed as part of the interview. Visual assignments were used as talking points in the interviews, which was assumed to aid the designers’ ability to express their thoughts during the interview. Participants were asked to define graphic design, describe their day-to-day creative design work, visualize their creative design process on paper (A4) and elaborate on the stages involved. Nini’s (Citation2006) process model served as a common starting point to establish a consensual terminology across participants. Participants were asked to define intuition and elaborate on the distinction between process (intuiting) and outcome (intuition) in their own (nonscientific) words. To support further elaboration on how they typically relied on intuition in their creative design process, participants visualized on paper (A3) how this reliance would change in their creative design process. They also explained when they used intuition, and why it was useful (or not) to rely on intuition; particularly focusing on design creativity. All interviews were carried out by the second author, who is a graphic designer by education and profession, which benefits interpretation validity. The interviews were audio-recorded (with explicit participant consent) and transcribed. We refer to the OSF page for further details about the questions, visual materials and structure used in the semi-structured interviews.1

3.3. Procedure

Potential participants were initially selected by browsing online portfolios of graphic designers in the region. Further selection criteria were that 1) the online portfolio matched the profile of a professional graphic designer (including projects for clients); and that 2) the portfolio suggested the graphic designer would regularly execute the full graphic design process (from briefing to final design). Many screened graphic designers worked in a business where they e.g. only developed design solutions, and so this would not enable them to comment on the role of intuition in other stages of the graphic design process as well. They were therefore excluded. If the above requirements were met, each selected graphic designer received an e-mail with information about the study and an invitation to participate. If the response was positive, two face-to-face meetings were scheduled approximately one week apart. In the first meeting, one of the authors visited the participant at their workplace to elaborate on the study, sign informed consent and deliver the cultural probe package. In the following week, each participant was free to choose when to execute the assignments in the package at their workplace. Then, each participant was revisited for a 20–40-minute interview. Each package and the other interview materials were collected, and the participant was thanked and offered to be informed about future findings. Since the author carrying out the interviews is a graphic designer, we followed Reich’s (Citation2017) research proposition, i.e. that design researchers should use design knowledge, methods and tools in designing their research, because such an approach improves outcomes.

3.4. Data analysis

Standard qualitative methods of interpretative analysis were used (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994; Zhang & Wildemuth, Citation2009). All audio data was fully transcribed, visualizations and cultural probes were digitized and all data was pseudonymised. First, units of coding were chosen based on an elaborate analysis of the transcriptions by the second author, who also conducted the interviews. Inductively generated codes served as guides to iteratively develop an initial coding scheme. This first coding process was designed to provide an initial and detailed overview of the themes present within the data, and how they would relate to the stages in Nini’s (Citation2006) creative design process. Transcribed interviews were coded focusing on the themes. Quotes deemed essential were placed in the relevant cells within the table. The first author reviewed the data transcripts to ensure all interpretation would err toward caution, thereby minimizing the risk of over-interpretation (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2005). The filled-out cultural probe assignments referred to in the interviews and the visualization assignments were reviewed alongside the interview transcripts to support interpretation. In the transcripts, participants would often refer to something in the probes or visualizations that they did not describe verbally, but did show during the interviews. This approach served to recreate that situation where needed. The resulting initial coding table is available at the study’s OSF page.1 Finally, the first and fourth author used thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) to condense the richly-coded data set into the following overarching themes: 1) Graphic design definitions and process; 2) Intuition in graphic designers’ creative design process, and 3) Reasoning depends on intuition. These resulting overarching themes were used to structure the Results section below.

4. Results

4.1. Definitions and process

4.1.1. Graphic design according to graphic designers

When asked to define graphic design, the participants initially refused to be concise. As P12 explained,

Graphic design is […] constantly evolving […] It can be the way you guide people from A to B. Multidisciplinary. [It] is constantly shifting and differs to everyone. The fact I find it hard to define it already says something […] It goes along with subareas and never stands on its own.

When probed further, some consistency emerged. Participants said graphic design involved visualizing information (P01, P03, P06, P07, P09, P10), creating concepts (P03, P07, P09, P10), combining text and image (P03, P08, P11) and imagining a story (P03, P06, P07, P09). P07 captured the gist of these descriptors, stating how a graphic designer is a ‘visual ambassador of the client’ hired to communicate visually a certain story to a target audience.

4.1.2. The creative design process of graphic designers

When asked to outline their creative design process, participants showed consensus. All participants engaged in information gathering, analysis, scoping and planning. Information gathering served to identify needs and problems via a client briefing. Gathered information was analyzed and unpacked by further research. Criteria were set and a strategy developed for the remainder of the creative design process, which entailed creating design concepts, gathering feedback and reaching a design solution. Design concepts of varying levels of fidelity were produced, selected and presented to the client (P03, P06, P08, P09), colleagues (P05, P10) or family or friends (P10) to get feedback. This feedback informed the creation of design solutions until the final design was reached. Participants alternated frequently between these stages (P03, P10, P12).

4.1.3. Intuition according to graphic designers

The participants defined intuition as a phenomenon or outcome of a cognitive process in two ways. Five participants defined intuition as knowledge, skills and past experience contained in memory, retrieved and used nonconsciously (P01, P02, P03, P04, P12). As P02 said, ‘Intuition secretly is knowledge’. Alternatively, five participants defined intuition as a feeling, the opposite of reason (P05, P06, P07, P08, P10). P07 said: ‘When you ask yourself “Does it feel good?” and you say yes or no to that question without reasoning, that decision is made by intuition’.

4.2. Intuition in graphic designers’ creative design process

4.2.1. Origins of intuition

All participants suggested intuition emerges from memories coming together with external stimuli. P09 referred to a drawing on the postcard (, left), saying:

That man sitting there represents me. Around him are all kinds of influences, such as what you have learned and taken in. So, books, music, happy feelings, graphic design skills. These elements are connected to me. In addition, there are some undefinable elements. These I have visualised as a rainbow and stars and some other abstract shapes. By taking all these things in, it creates a window which, eventually, will help you to take your design across the finish line.

Common memories mentioned include previous experiences (P01, P02, P03, P04, P07, P08, P1, P11, P12), knowledge (P03, P04, P05, P08, P09, P12) and background and education (P02, P03, P6). External stimuli included the direct environment (P05, P06, P07, P08, P09, P10, P11), inspirational materials (P06, P07, P08), the client brief (P05, P11) and impressions (P02). Emotion was also mentioned (P09).

4.2.2. Use of intuition according to the graphic designers

When asked to elaborate on when they used their intuition, all participants suggested that intuition was critical in their creative design process. Three participants relied upon intuition for information gathering to obtain and select information when working with clients, and later to fill in gaps in case of uncertainty about the utility of information provided by a client (P02, P05, P09). P09 described how ‘you have to ask proper questions’ at the beginning to obtain information, which requires intuition. P10 noted how intuition is used to select information relevant to advance the creative process: ‘Your intuition needs to assist you to recognize things you can pick up on’. Others relied less on their intuition, but admitted this was not always possible (P03, P10). As P10 said, ‘It starts with listening, that’s not intuitive. […] However, you can’t completely switch it off.’

The participants were less vocal about the use of intuition during information analysis, scoping and planning. However, P02 stated that when the client’s input turned out to not be sufficiently clear, intuition later helped to fill in the gaps. According to P02, ‘When you are talking about intuition, you have to try to think what your client thinks, and hope they think that as well’, elaborating how intuition functions when developing a strategy and setting criteria,

[…] that bit of intuition: What makes you believe how another person works, and how you yourself work. That intuition provides a starting point for making [design concepts], and when things are not clear, you follow your intuition to fill the gaps.

All participants used their intuition when creating design concepts. The section on gut feelings (below) provides detail.

For all but three participants (P02, P05, P11), intuition was decreasingly relied upon after gathering feedback on their design concepts. Just as during information gathering, intuition was instrumental in obtaining and selecting information as well as when filling in gaps in the information obtained. To get relevant feedback, ‘You need your intuition to present a design to the client’ (P11), and in the absence of (appropriate) feedback, intuition was used to fill in the gaps (P02, P05). Three participants noted that information gathering would not require intuition at all (P03, P06, P08).

The moment the design solution was finished marked another low point in reliance on intuition. The final graphic design simply needed to meet the set criteria. However, for three participants (P05, P09, P11), intuition could also be critical here. As P09 stated, ‘In the end, you still need your intuition to have a good feeling about the final design’.

4.2.3. Use of gut feelings according to the graphic designers

When creating design concepts, and to some extent design solutions, five participants (P05, P06, P07, P08, P10) claimed to often design based on their gut feelings. Gut feelings facilitated envisioning the design before creating design concepts, guiding actions to manipulate design materials, and evaluating the results of these actions during the creation of design concepts and design solutions. Three participants (P01, P02, P09) reported how envisioning a general direction provided a starting point for the design concepts. As P09 explained, ”It was related to the building industry, so pretty quickly I had a perspective projection in my head, which was supposed to represent some kind of building.” All participants reported using their gut feeling to inform which creative actions to undertake to manipulate their materials in order to achieve a relevant design. As P01 said, ‘Yesterday, I designed an animation, and how you make one image flow smoothly into another is not something you sort out. That is something you do by feeling’. The relationship between intuition and evaluations of the consequences of these actions, in turn, was described as a feeling that the actions undertaken were pushing the design in the proper direction, a ‘yes-moment’ (P09) or something that ‘feels right’ (P07). For example, ‘when you have to choose a certain color […] Like, I choose yellow and that feels right, then it is intuition. But when you choose yellow because it means happiness and positivity, it is not intuition’ (P07).

Intuition also played a role in higher-level evaluations and decisions, such as the choice of which design concepts, and ultimately design solution, to share with the client (or others) (P03, P06, P09, P11). P06 once designed a logo for a company, and his gut feeling helped choose the best option from his sketches, ‘We tried many different compositions, and eventually we chose the design that felt best and was right’.

4.3. Reasoning depends on intuition

4.3.1. Consciousness and nonconsciousness

Participants frequently discussed conscious and nonconscious subprocesses. During information gathering, information gained nonconsciously complemented information obtained consciously (P02, P08, P11). As P11 reported, ‘Direct input from the client you gain consciously. Environmental information, like your client’s office or clothing style, is gained nonconsciously.’ Information analysis and research were often said to be driven by conscious processes to which nonconscious processes contributed (P01, P04, P05, P12). Although the interviews provided limited insight, P01 explained that ‘When collecting information, you don’t think a lot […] you just look and internalize what you see.’ P03 and P05 mentioned that establishing a strategy and criteria partly happens nonconsciously. As results of nonconscious subprocesses enter into consciousness, they serve as inspiration and are acted upon consciously. P03 outlined it thus: ‘Establishing criteria […] partly happens nonconsciously […] I see something and realize that could have potential. Then, I zoom in on that consciously, resulting in guidelines. Those I establish consciously’.

While working with design materials in creating design concepts and design solutions, two behavioral patterns were reported, i.e. nonconscious processes are acted upon when they enter into awareness, and the nonconscious processes in designing are checked consciously for correctness (P03, P04, P05, P11). P05 described the former:

I think you act on things you experience nonconsciously. This acting, so the moment you do something, is conscious […] When you see two different shapes and your feeling tells you that you have to choose one, that thought is nonconscious and the acting is conscious.

Nonconscious subprocesses were said to emerge in cases of markedly low (P04) and high (P05, P12) uncertainty about what to do. P04 stated that ‘Sometimes, you make a conscious decision: Blue for business, green for bio-industry. Whenever the decision is less obvious, you let yourself be guided by nonconscious processes, and thus by intuition’. P05, on the other hand, stressed also that applying ‘basic graphic design rules you have learned during your studies’ is often guided by nonconscious processes. Such patterns also arose when participants described alternations between intuition and reasoning.

4.3.2. Intuition and reason

The above behavioral patterns resonated with participants’ descriptions of how they believed intuition and reason complement each other. Seven participants (P03, P04, P06, P08, P09, P10, P11) suggested that when intuition occurs, this inspires, as it were, how to take the creative design process forward by reasoning which steps to take next. P03 put it this way,

Sometimes you are working nonconsciously and suddenly you see something cool, which you develop further. That development you do by reasoning. […] For example, a line in the grid could go either way and connect things to each other. That arose purely out of intuition. I saw it happen, played with it and reinforced it with reason.

Five participants (P03, P04, P05, P08, P11) said that intuition (also) requires a so-called conscious check. Through reasoning, this critical check reviews if a given intuition fits within the constraints set for the particular graphic design project, thereby serving to correct the continued direction for the hitherto intuitively conceived creative design process. P08 used the postcard to explain this. He visualized intuition as a tree branching into different directions guided by his intuition with design project constraints as the brackets around the tree (, right).

5. Discussion

The idea that intuition pervades creative processes is not new. As Poincaré and Crosswhite (Citation1969) stated half a century ago, ‘logic and intuition have each their necessary role. Each is indispensable. Logic, which alone can give certainty, is the instrument of demonstration; intuition is the instrument of invention’ (p. 210). Our aim was to push beyond such widespread understandings and examine in more detail how professional graphic designers more concretely resort to intuition when engaged in creative design processes.

5.1. Intuition as an ephemeral facility

The graphic designers, we argue, rely on intuition as what we will call an ephemeral facility that serves to support their creative design process. We outline the grounds for this neologism below.

The data analysis revealed that graphic designers viewed intuiting as the nonconscious application of knowledge, past experiences and other types of memories to make creative decisions. This aligns with existing definitions of intuition in design creativity (e.g. Darwich, Citation2016; Faste, Citation2017). In the creative design process, intuiting was shaped by information contained in these memories combined with external stimuli, particularly from participants’ direct external environment and inspirational materials (Laing & Masoodian, Citation2016). This to some extent confirms work by Raidl and Lubart (Citation2001) where intuiting is seen as a ‘perceptual process, constructed through a mainly subconscious act of linking disparate elements of information: 1) external stimuli, 2) memory, 3) emotions, and 4) subconscious concerns’ (p. 219). In the present study, the most significant elements were found to be external stimuli and memory, whereas emotions were only reported by one participant (P06), and the analysis revealed no evident examples of subconscious concerns.

The graphic designers’ intuition enabled them to engage in ‘designing by feeling’ (P08), as the results of their nonconscious creative decisions entered into consciousness very briefly as a positive feeling. This prompted a sense of reassurance, i.e. that something felt right (P07), which increased certainty about creative decisions taken nonconsciously, signaling that their intuitive work could be relied and acted upon to carry their creative design process forward. This aligns with earlier suggestions that an intuition, as the outcome of intuiting, is experienced as a (positive) feeling (Dörfler & Ackermann, Citation2012) and is critical for the progression of the creative design process (Raidl & Lubart, Citation2001).

The results further suggested that reasoning could depend on intuition in the creative graphic design process. Two cases stood out:

Inspiration: A positive feeling that prompts tracing back nonconscious creative decisions and consciously reason out the next creative steps to be taken;

Conscious check: A positive feeling that prompts a conscious check, e.g. to ensure that intuition had not led to violations of the set design criteria.

These results are in accordance with Faste’s (Citation2017) auto-ethnographic study of a free design task, which suggested that intuition helped to guide conscious approaches taken in the creative design process. This included working out creative decisions necessary to generate novel designs, supporting inspiration and curiosity, evaluating (intermediate) designs, and supporting critical thought about the creative direction needed to be undertaken. Similarly, the results align with previous work by Taura and Nagai (Citation2017), who conjectured that the creative design process comprises stages of intuition and gut feeling that are subsequently followed by analysis or synthesis. The present study augments these insights by showing that some graphic designers also employ a conscious check that is prompted by an intuition, which lets them correct their intuiting on-the-fly at a given point in a creative design process.

On this basis, we argue that the role of intuition among graphic designers may best be characterized as an ephemeral facility. Given the tangible connotations of the term instrument (Poincaré & Crosswhite, Citation1969), the neologism we propose aims to better capture the elusive and transitory nature of intuition as a feeling that only briefly enters into consciousness (ephemeral). In this view, the notion of ‘instrument’ could be seen as something the subject constructs, and to some extent is able to control; a perspective that bears some resemblance to the philosophy of Rabardel (Laisney & Chatoney, Citationin press). Moreover, intuition reinforces ongoing nonconscious creative decisions. This points to its enabling cognitive potential when applied in a creative graphic design process (facility). The latter happens by eliciting certainty that some creative decisions can either be relied upon and sustained, such as P09’s ‘yes moment’ or, conversely, can cause a shift toward an increased reliance on conscious reasoning, such as P03’s intuition that something has potential, prompting him to ‘zoom in on that consciously, resulting in guidelines’. We intentionally do not use the term ‘competence’, as this is semantically very complex and often used interchangeably with ‘ability’, ‘skill’, ‘aptitude’, etc. (Weinert, Citation1999). Our use of the term ‘facility’ is informed by Watson’s (Citation2018) ‘epistemic facility’, which captures the cognitive (and epistemic) aspects of expert authority in a given domain, in this case graphic design. below sums up how intuition serves as an ephemeral facility during the creative design process of graphic designers.

Figure 2. How graphic designers rely on intuition as an ephemeral facility to progress their creative design process

These findings further suggest that this ephemeral facility aids social and material interactions and decisions about when to switch from one stage to another in the creative design process.

5.2. Intuition Is critical for social interactions

Social interactions were necessary during information gathering and the gathering of feedback, and sometimes as a (imagined) resource for information analysis, scoping and planning. Here, some graphic designers reported that intuition could help where reasoning fell short; in particular in cases of uncertainty about what the client wanted, what the graphic designers believed their target group wants, and how this best aligned with what the graphic designers themselves needed (or wanted) in order to carry the creative design process forward. In such instances, the graphic designers relied on intuition to:

Obtain information by formulating questions to elicit information during information and feedback gathering;

Select information that appears relevant during information and feedback gathering;

Fill in gaps when information gathered turned out to be insufficient during information analysis, scoping or planning.

This suggests that some professional graphic designers developed a blend of what Raidl and Lubart (Citation2001) called socio-affective intuition and applied intuition (see above). During social interactions, this special kind of intuition was applied to acquire information needed to execute the creative design process effectively and solve the graphic design problem at hand. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to provide empirical evidence for these specialized types of intuition in the context of professional graphic design practice and, quite possibly, in design in general.

5.3. Intuition is critical for material interactions

Material interactions were central when the graphic designers worked with design materials to create design concepts and design solutions. In situations where it was not yet obvious how to proceed, intuition enabled the graphic designers to feel through stages of a high level of uncertainty in their creative design process to keep momentum. The same behavioral pattern could be discerned in stages of a high level of certainty, where the tried-and-true path could be followed. There, the graphic designers relied on intuition to:

Envision a starting point for the design, i.e. a vague direction needed to begin creating design concepts;

Act by manipulating design materials to create design concepts and solutions to ensure an apt design;

Evaluate results of the creative decisions and guiding the next actions to be taken to ensure an apt design.

The relevance of design materials for ideation is established (e.g. Biskjaer et al., Citation2017; Schön, Citation1992). While studying how novel ideas and concepts emerge, Hutchins (Citation2005) argued that materials can serve as ‘material anchors’ in a conceptual blending process in case the blend is so complex that it becomes too cognitively taxing. We speculate that there could be a connection between the familiar experience of ‘knowing without knowing how or why’ (e.g. Dörfler & Ackermann, Citation2012) and the cognitive mechanisms by which a conceptual blend such as a design concept emerges. This would relate to Dane and Pratt (Citation2007) creative intuition or Sinclair’s (Citation2010) intuitive creation. Pursuing this in depth, however, is beyond the scope of this paper.

5.4. Intuition is critical throughout the creative design process

Some graphic designers also relied upon intuition for switching between some stages in their creative design process:

Planning-Creating design concepts. A positive feeling during scoping and planning that signals alignment of the understanding of the needs and problems of the client, target group and graphic designers themselves, which helps to decide when to start creating design concepts;

Creating design concepts-Gathering feedback. Positive feelings about design concepts signal that these could be presented to the client (or others) to gather feedback;

Creating design solutions-Final design. A positive feeling about a created design solution helps to decide when to finalize and share with the client.

Such decisions are typically framed as being based mainly on experience, such as in Schön’s (Citation1983) (practical) knowing-in-action, and rational decision-making (Nini, Citation2006). The present study shows that intuition not only complements, but indeed also contributes to these decisions, possibly in a way that resembles Sinclair’s (Citation2010) intuitive foresight by sensing opportunities (or risks) that seem hidden to others. These insights are summarized in below.

Figure 3. The roles of intuition in the creative process of graphic designers. Figure shows the creative graphic design process according to the participants (middle of image); where and how intuition weighs in on decisions to move from one stage in the creative process to the next (top of image); and where and how, within the stages of the creative process, intuition facilitates social (bottom left) and material (bottom right) interactions

5.5. Limitations

Although we followed Visser et al. (Citation2005) and made efforts to sensitize the graphic designers to their use of intuition before the semi-structured interviews, this procedure might not suffice for enabling the participants to report comprehensively how they regularly and consistently might employ and experience intuition in a creative graphic design process. Compared to other such process stages, less data was captured specifically on how intuition informs information analysis, scoping, planning and gathering feedback. This prioritization might affect the results’ descriptive validity. While the English language distinguishes between intuiting and intuition, the Dutch language (as spoken by the participants during the data collection) does not. Since this distinction is of theoretical relevance, the research team was forced to conjecture this distinction semantically based on textual indicators of process (intuiting) and outcome (intuition) contained in the data transcripts. This might have had a small impact on the results’ construct validity; however, we wish to stress that the participants were all able to differentiate between process and outcome using their own words. As indicates, the study did not contain any rich data on how reasoning is (also) crucial in the creative design process of graphic designers. Although most design decisions about checks and balances in client-based professional design practice are made rationally, this study cannot lend any substantial evidence to support further insights into this particular perspective. We have focused exclusively on the domain of professional graphic design, and so the data obtained herein cannot suggest how intuition might pervade creative processes in related domains such as interaction design or media art. Also, the sampling criteria used might have also introduced some degree of sampling bias. Next to participants being Dutch, their portfolios also needed to suggest that they executed the full graphic design process on a regular basis, potentially causing a biased selection toward participants who often work on a freelance basis. These limitations are relevant for the results’ external validity. Finally, since the analysis in this qualitative study is based on how the graphic designers report on understanding, using and relying upon intuition, this approach inevitably limits the study’s overall reliability and validity.

5.6. Future work

The results of the present study provide a rich basis for future work. We propose two immediate paths. Firstly, our research design has intentionally favored breadth over depth. The role of intuition in supporting social and material interactions in particular seems a fruitful starting point for more in-depth future research. A promising place to start would be Hutchins (Citation2005) work on distributed cognition and material anchors, predictive processing accounts of ideation (Valtulina & de Rooij, Citation2019) and Schön’s (Citation1992) design as a reflective conversation with the materials of a design situation. This might yield a more detailed model of intuition in creative graphic design processes, as graphic design practice is heavily based on working with concrete (mainly visual) materials. Secondly, the results suggest that graphic designers use their intuition as an ephemeral facility that emerges from the combination of memory, e.g. knowledge and previous experiences, and external stimuli, e.g. environmental stimuli and inspirational materials. This begs the question whether––and if so, how––intuition can be trained, ranging from learning to use the right knowledge, heuristics, and stimuli, to when and for what to rely on intuition or not. A starting point could be to study how intuition relates to Csikszentmihalyi’s (Citation2008) seminal concept of flow, especially among experts in a given domain, and to the closely related phenomenon design fixation, which has explored in detail the effects of stimuli and inspirational materials on creativity (Vasconcelos & Crilly, Citation2016). This research trajectory requires more insight into when intuition is effective––or ineffective or even detrimental––to creative design practice, how it is learned, and when it should be favored over reasoning. Investigating in detail how expert designers rely on intuition as compared to novice designers (see e.g. Stierand & Dörfler, Citation2015) seems like an expedient avenue for exploring how one might train intuition to become an even more efficient ephemeral facility. Such studies would be very valuable to graphic design education, professional practice and, not least, future interdisciplinary research on how to best advance our currently limited understanding of the critical and complex role of intuition in creative design processes.

Contribution statement

This study contributes new empirically based insight into the role and relevance of intuition for progressing the creative design process, including the social and material interactions therein.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Innovation Fund Denmark (CIBIS 1311-00001B) and the Velux Foundations grant: Digital Tools in Collaborative Creativity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The cultural probes, semi-structured interview questions, visual support materials and initial coding table can be found at https://osf.io/qy8z5/ Please contact the corresponding author for access to the pseudonymized dataset.

References

- Alhajri, S. A. (2017). Investigating creativity in graphic design education from psychological perspectives. Journal of Arts and Humanities, 6(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.18533/journal.v6i01.1079

- Badke-Schaub, P., & Eris, O. (2014). A theoretical approach to intuition in design: Does design methodology need to account for unconscious processes? In A. Chakrabarti & L. T. M. Blessing (Eds.), An anthology of theories and models of design (pp. 353–370). Springer.

- Bennett, A. (2006). The rise of research in graphic design. In A. Bennett (Ed.), Design studies–– Theory and research in graphic design (pp. 14–25). Princeton Architectural Press.

- Biskjaer, M. M., Dalsgaard, P., & Halskov, K. (2017). Understanding creativity methods in design. Proceedings of DIS 2017 (pp. 839–851), Edinburg, UK. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3064663.3064692

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Carson, L. (2017, July 7). The importance of intuition in the design process. Design by Bird. Retrieved November 12, 2019, from http://designbybird.com.au/perspective/intuition

- Çizgen, G., & Uraz, T. U. (2019). The unknown position of intuition in design activity. The Design Journal, 22(3), 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1589414

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper Perennial, Modern Classics.

- Dane, E., & Pratt, M. G. (2007). Exploring intuition and its role in managerial decision making. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 33–54. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.23463682

- Darwich, B. B. (2016). Re-cognition: Intuition as knowledge. In Proceedings of FEC 2016, art. 437. libreria universitaria, Florence, Italy.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage.

- Dijksterhuis, A., & Nordgren, L. F. (2006). A theory of unconscious thought. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00007.x

- Dörfler, V., & Ackermann, F. (2012). Understanding intuition: The case for two forms of intuition. Management Learning, 43(5), 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507611434686

- Drucker, J., & McVarish, E. (2009). Graphic design history: A critical guide. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Faste, H. (2017). Intuition in design: Reflections on the iterative aesthetics of form. Proceedings CHI 2017 (pp. 3403–3413), Denver, CO, USA. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025534

- Frascara, J. (2004). Communication design: Principles, methods, and practice. Allworth Press.

- Hogarth, R. M. (2001). Educating intuition. University of Chicago Press.

- Hutchins, E. (2005). Material anchors for conceptual blends. Journal of Pragmatics, 37(10), 1555–1577. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2004.06.008

- Isenman, L. (2018). Understanding intuition:A journey in and out of science. Academic Press.

- Kannengiesser, U., & Gero, J. S. (2019). Design thinking, fast and slow: A framework for Kahneman’s dual-system theory in design. Design Science, 5(e10), 1–21. http://doi.org/10.1017/dsj.2019.9

- Laing, S., & Masoodian, M. (2016). A study of the influence of visual imagery on graphic design ideation. Design Studies, 45(Part B), 187–209. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2016.04.002

- Laisney, P., & Chatoney, M. (in press). Instrumented activity and theory of instrument of Pierre Rabardel. In Philosophy of technology for technology education. Brill Sense. Retrieved May 3rd, 2021, from https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01903109

- Meggs, P. B., & Purvis, A. W. (2012). Meggs’ history of graphic design. Wiley.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage.

- Nini, P. J. (2006). Sharpening one’s axe: Making a case for a comprehensive approach to research in the graphic design process.”. In A. Bennett (Ed.), Design studies––theory and research in graphic design (pp. 117–129). Princeton Architectural Press.

- Patterson, R. E., & Eggleston, R. G. (2017). Intuitive cognition. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 11(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555343416686476

- Poincaré, H., & Crosswhite, F. J. (1969). Intuition and logic in mathematics. The Mathematics Teacher, 62 (3), 205–212. Retrieved May 3rd, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/27958100.

- Policastro, E. (1995). Creative intuition: An integrative review. Creativity Research Journal, 8(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj0802_1

- Raidl, M.-H., & Lubart, T. I. (2001). An empirical study of intuition and creativity. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 20(3), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.2190/34QQ-EX6N-TF8V-7U3N

- Reich, Y. (2017). The principle of reflexive practice. Design Science, 3(e4), 1–27. http://doi.org/10.1017/dsj.2017.3

- Roozenburg, N. F. M., & Cross, N. G. (1991). Models of the design process: Integrating across the disciplines. Design Studies, 12(4), 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-694X(91)90034-T

- Sadler-Smith, E. (2007). Inside Intuition. Routledge.

- Schenk, P. (1991). The role of drawing in the graphic design process. Design Studies, 12(3), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-694X(91)90025-R

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. Basic Books.

- Schön, D. A. (1992). Designing as reflective conversation with the materials of a design situation. Knowledge-Based Systems, 5(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/0950-7051(92)90020-G

- Sinclair, M. (2010). Misconceptions about intuition. Psychological Inquiry, 21(4), 378–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840x.2010.523874

- Sinclair, M. (Ed.). (2014). Handbook of research methods on intuition. Edward Elgar.

- Stierand, M., & Dörfler, V. (2015). The role of intuition in the creative process of expert chefs. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 50(3), 178–185. http://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.100

- Taffe, S. (2017). Who’s in charge? End-users challenge graphic designers’ intuition through visual verbal Co-design. The Design Journal, 20(1), 390–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352916

- Taffe, S., & Barnes, C. (2010). Outcomes we didn’t expect: Participant’s shifting investment in graphic design.” Proceedings of PDC 2010, (pp. 211–214), Sydney, AU. ACM. https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1900482

- Taura, T., & Nagai, Y. (2017). Creativity in innovation design: The roles of intuition, synthesis, and hypothesis.”. International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation, 5(3–4), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2017.1313132

- The politics of aesthetics: What does it mean to design? (2011). That new design smell. Retrieved November 12th, 2019 from https://thatnewdesignsmell.net/daniel-van-der-velden-explains-himself

- Valtulina, J., & de Rooij, A. (2019). The predictive creative mind: A first look at spontaneous predictions and evaluations during idea generation. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(article 2465), 1–14. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02465

- Vasconcelos, L. A., & Crilly, N. (2016). Inspiration and fixation: Questions, methods, findings, and challenges. Design Studies, 42, 1–32.

- Visser, F. S., Stappers, P. J., van der Lugt, R., & Sanders, E. B.-N. (2005). Contextmapping: Experiences from practice. CoDesign, 1(2), 119–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880500135987

- Waller, R. (1980). Graphic aspects of complex texts: Typography as macropunctuation. In P. A. Wrolstad Koelers, M. Ernest, & H. Bouma (Eds.), Processing of visible language (pp. 241–253). Plenum Press.

- Watson, J. C. (2018). The shoulders of giants: A case for non-veritism about expert authority. Topoi, 37(1), 39–53. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-016-9421-0

- Weinert, F. E. (1999). Definition and selection of competencies: Concepts of competence.” Max Planck Institute for Psychological Research. Retrieved May 3rd, 2021, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?

- Wengraf, T. (2001). Qualitative research interviewing: Biographic narrative and semi-structured methods. Sage.

- Zander, T., Öllinger, M., & Volz, K. G. (2016). Intuition and insight: Two processes that build on each other or fundamentally differ? Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1395. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01395

- Zhang, Y., & Wildemuth, B. (2009). Qualitative analysis of content. Libraries Unlimited.