Abstract

User comments to digital news often contain media criticism, detrimentally affecting how others perceive the quality of news and possibly lowering media trust. It remains an open question, however, how journalistic reactions can mitigate these effects. Based on premises of engagement moderation, accountability, and transparency in digital journalism, we conducted an online experiment investigating how critical user comments and journalistic reactions affect quality perceptions and behavioral intentions towards a news media brand. Results show that media-critical comments lower perceived brand quality, but only among media cynics, whereby increasing it among media supporters. Journalists admitting mistakes only enhances perceived brand quality for media cynics, while denying does so for everyone and decreases cynics’ intention to comment negatively. Lastly, explaining why a mistake was made or not boosts brand quality perceptions overall, suggesting that transparency is a viable strategy for improving media trust in the long run.

Media criticism by the audience is prevalent in digital media, most prominently on social media pages of news brands or in comment sections below journalistic articles (Ziegele et al. Citation2017). Criticizing the news media is nothing new, however: the performance of news media has been the target of criticism by recipients for as long as news media exist (Wyatt Citation2007). Even more so: in democratic societies, (constructive) media criticism is necessary. A critical and cautious public that monitors news media’s performance and holds them accountable is an important corrective for journalism and can strengthen its position in society. Although there are many forms of user feedback, user comments are a particularly interesting and relevant space for such criticism. First, users’ criticism, journalistic reactions and subsequent discussions are public, potentially reaching the same audience as journalistic articles themselves. Second, recipients can address their concerns directly to journalists without having to go through editorial offices and journalists can immediately respond to criticism. A recent study by Risch and Krestel (Citation2020) shows that journalists are indeed most likely to react to comments that voice dissent with an article, making these situations the most frequent form of user-journalist interactions in comment sections. This is one manifestation of a larger paradigm shift in digital news environments, where audiences can act as “empowered networks” (Loosen and Schmidt Citation2012, 871) that increasingly interact with journalism.

Next to the presumably positive effects of increased interaction of journalism and its audience, research also shows worrisome effects. Most notably, user comments have considerable impact on how recipients perceive news articles and brands (Prochazka, Weber, and Schweiger Citation2018). Especially criticism in comments can damage the perceived quality of news (Kümpel and Springer Citation2016). In the long run, critical comments may therefore contribute to a loss of trust in news media at large (Pingree et al. Citation2018), since quality perceptions are a main prerequisite for generalized media trust (Vanacker and Belmas Citation2009). This is especially worrisome, since media criticism in user comments is not always constructive, but in many cases contains unjustified and generalized accusations, as has been shown during the “lying press” debate in Germany (Prochazka and Schweiger Citation2016). Moreover, media criticism in user comments can affect behavior. It could for example encourage other users to check the facts presented in the respective article (Pingree et al. Citation2018), but also to engage in discussion or refrain from using content by a specific news media brand overall. Thus, although media criticism promotes more reflective engagement with the reporting, (unjustified) accusations could reinforce negative attitudes towards the media or lead to news avoidance. The latter could in turn have negative effects for an informed citizenry and the economic foundation of news brands (Toff and Kalogeropoulos Citation2020).

This raises the question how journalists and news brands should deal with critical comments. However, research so far has neglected how journalists can mitigate the effects of critical user comments by confronting criticism and engaging with users. We aim to close this research gap with an experimental study investigating how media criticism and journalistic reactions in comments affect quality perceptions of a news media brand and behavior intentions towards that brand. Based on premises of engagement moderation, accountability, and transparency in journalism, we vary 1) media criticism in user comments (hasty work vs. lack of integrity), 2) journalistic reactions to a critical comment (denying vs. admitting a mistake) and 3) a transparent explanation for why a mistake was made or not (explanation vs. no explanation). Also, we look at whether cynical attitudes of recipients towards news media moderate the effects of those factors, since media criticism and journalistic reactions might be interpreted vastly different depending on what one thinks about the media in general.

Effects of Media Criticism in User Comments

Effects on Quality Perceptions

Perceptions of journalistic quality refer to how readers perceive certain indicators to be met in news stories, media brands or the media at large. However, there is no uniformly accepted definition or list of quality criteria, since there “is no quality in an item itself, but only some kind of convention to interpret certain objective indicators as high or low quality” (Urban and Schweiger Citation2014, 822). Most of those indicators are derived from normative functions journalism ought to fulfil in a democratic society (McQuail Citation2013). Thus, most scholars agree that they entail criteria such as accuracy, independence, diversity, impartiality, relevance, but also transparency and diligence (Fawzi and Mothes Citation2020; Neuberger Citation2014; Prochazka Citation2020; Urban and Schweiger Citation2014). Survey research has shown that there is a broad consensus among journalists and audiences that those are important quality criteria in journalism (Loosen, Reimer, and Hölig Citation2020). However, recipients are usually not particularly good at recognizing and differentiating these normative quality criteria in actual reporting (Dohle Citation2018; Urban and Schweiger Citation2014). Rather, they evaluate journalistic news holistically, which is reflected in high correlations between perceptions of different criteria (Yale et al. Citation2015). As suggested, recipients’ perceptions of journalistic quality are crucial because they are a key prerequisite for generalized trust in news media. While quality perceptions refer to evaluations of journalistic content at a given point in time, trust is oriented towards the future and entails the willingness to be vulnerable to news content, based on the expectation that the media will perform according to expectations (Hanitzsch, Van Dalen, and Steindl Citation2018; Prochazka Citation2020).

To our knowledge, Kümpel and Springer (Citation2016) were the first to investigate how critical comments shape quality perceptions of online news. In their study, praising an article in the comments increased its perceived quality among readers (see also Kümpel and Unkel Citation2020 for Facebook comments). Dohle (Citation2018) varied the valence of comments (positive vs. critical) as well as the actual journalistic quality of the article. Comments had an even stronger impact on how the quality of an article was perceived than the quality of the article itself. Most recently, Naab et al. (Citation2020) confirmed the negative effects of criticism in comments on the credibility of a news article.

One explanation for these effects of (critical) user comments can be found in theories of information processing: recipients are often neither motivated nor take the time to elaborate on the quality of journalistic content (Urban and Schweiger Citation2014), resulting in superficial processing. In these conditions, users base quality judgments on peripheral or heuristic cues like a news brand or the content of user comments (Masullo and Kim Citation2021; Prochazka, Weber, and Schweiger Citation2018; Weber, Prochazka, and Schweiger Citation2019). User comments are particularly influential, since they are more salient, easily readable, and short compared to journalistic articles.

However, many questions remain open regarding the effects of critical comments. First, studies have mainly investigated effects on the perceived quality of news articles. Thus, we do not know whether critical comments also affect perceptions of a media brand, which is possibly even more consequential for journalism at large. Second, previous studies have only compared positive and negative comments, ignoring that different accusations could also influence quality perceptions in different ways. There are numerous findings that media criticism in user comments and public discourse often refers to two core accusations that can be traced back to the early research on credibility (Hovland, Janis, and Kelley Citation1953). First, criticism of hasty work, and second, accusations of a lack of integrity in journalism (Craft, Vos, and Wolfgang Citation2016; Neurauter-Kessels Citation2011; Prochazka and Schweiger Citation2016). Recipients criticizing hasty work insinuate that journalists make mistakes due to a lack of resources and/or competence. In criticizing a lack of integrity, however, recipients suspect intentional manipulations so that journalists do not report balanced and fairly. These accusations are also constituent for a cynical attitude towards news media (Cappella and Jamieson Citation1997; Prochazka Citation2020). For our present study, we therefore focus on the accusations of hasty work and a lack of integrity that are voiced in user comments. Both points of criticism thus refer to misconduct within the journalistic work process. However, it is conceivable that a lack of integrity has stronger effects on perceptions of quality, since these shortcomings indicate systematic political or economic influences on journalistic work that are not easy to eliminate (Prochazka and Schweiger Citation2016). Hasty journalistic work, however, could be solved by changes in the editorial environment or personnel decisions. Thus, we assume:

H1a: Media criticism in user comments decreases the perceived quality of a news media brand compared to no user comments.

H1b: Media criticism in user comments decreases the perceived quality of a news media brand more strongly when user comments criticize a lack of journalistic integrity compared to criticizing hasty work.

Effects on Behavioral Intentions

Media criticism in user comments can also influence recipients’ behavioral intentions regarding news media brands. First, it can be assumed that media-critical comments motivate recipients to check the criticized content and its facts on their own initiative (Pingree et al. Citation2018), for example by comparing the content with the reporting of other media or discussing it with other people. Because comments critical of the media call aspects of journalistic quality into question, they might want to verify the claims made in the comments themselves before forming their opinion based on the reporting. Similarly, media criticism could motivate users to obtain further information and read more articles of the same brand before forming an opinion. Research on persuasive communication shows that product reviews in user comments affect purchase intentions according to the valence of the review (Cheung and Thadani Citation2012). Transferred to journalistic content, media-critical user comments may serve as a cue for recipients whether it is worthwhile to keep using a particular media brand. This may especially hold true for media brands unknown to recipients because they have not yet formed attitudes about their performance.

Moreover, a major motivation for users to comment on news is to publicly “correct” perceived deficiencies in media reporting (Springer, Engelmann, and Pfaffinger Citation2015). This is especially true if they perceive media coverage as biased against their view (Barnidge, Sayre, and Rojas Citation2015; Rojas Citation2010). Thus, criticism in comments may lead to corrective actions like posting another media-critical comment. Yet, when recipients perceive the journalistic quality standards to be met, they might be inclined to comment as well – to defend the media brand and to “correct” a possibly false accusation. However, due to the lack of research regarding recipients’ behavioral intentions following media criticism in user comments, we ask

RQ1: How does media criticism in user comments affect recipients’ behavioral intentions (regarding fact checking, media use, and writing user comments), compared to no user comments?

Effects of Journalistic Reactions to Media Criticism

Since media criticism in user comments may detrimentally affect perceptions of journalistic quality, the question arises how journalists should respond to such criticism. Digital communication has increased the possibilities for journalists and audiences to interact, which also reflects in increased public demands for dialogue, responsiveness, and transparency in journalism (Loosen, Reimer, and Hölig Citation2020). Moreover, in digital environments, news media increasingly compete with non-journalistic information providers like alternative media, laypeople, or organizations (Holt, Figenschou, and Frischlich Citation2019). Thus, potential effects and audience demands force news brands to address critical user comments. Of course, news media can delete critical comments from their websites or social media profiles (i.e. content moderation, Ziegele et al. Citation2018a). This is a reasonable approach for comments containing intolerant discourse or hate speech (Rossini Citation2020), but also leads to difficult decisions as to what the right to free speech covers and what not. In any case, reasonable criticism of the media is an important part of public discourse, a necessary corrective for journalism and a means to reinforce its professional norms (Craft, Vos, and Wolfgang Citation2016). Thus, when confronted with criticism in comments, journalists best adopt practices from interactive or engagement moderation (Masullo, Riedl, and Elyse Huang Citation2020; Ziegele and Jost Citation2020). These terms refer to journalists taking part in user discussions on the news and reacting to user comments, fostering a reciprocal relationship of journalism and its audience (Lewis, Holton, and Coddington Citation2014). Most research concerning engagement moderation has been done on (in)civility in user comments (Santana Citation2016), i.e. the question how journalists can improve the quality of online discussions by taking part in them. All in all, this work shows that journalists engaging with users in comments can increase the quality of discussions and the perception of a news media brand (Masullo, Riedl, and Elyse Huang Citation2020; Stroud et al. Citation2015; Ziegele and Jost Citation2020; Ziegele et al. Citation2018b). Regarding media criticism in comments, Naab et al. (Citation2020) show in the only study addressing this question that other users refuting critical comments positively affects credibility ratings of an article, whereas comments by the news media brand do not have the same effect. However, the study only investigated how disagreement of the news brand’s comment with the critical comment affects credibility ratings. It therefore remains open how different strategies and forms of engagement moderation fare in response to media-critical comments.

Accountability

We propose two strategies of engagement moderation in response to media-critical comments: accountability and transparency. According to McQuail (Citation2003, 19), media accountability is “when authors […] take responsibility for the quality and consequences of the publication, orient themselves to audiences and others affected, and respond to their expectations and those of the wider society.” Thus, accountability in engagement moderation to media criticism first means to respond to criticism as opposed to ignoring it. Second, it means to discuss the criticism in more detail and can include admitting (if criticism is legitimate) or denying mistakes (if criticism is unjustified) (Karlsson, Clerwall, and Nord Citation2017). In journalism research and practice, however, it is contested whether admitting mistakes is harmful or beneficial for the public perception of a media brand (Reimer Citation2017). For one, admitting mistakes may damage the perceived quality of a brand, because it shows journalism to be fallible. For another, since mistakes are human and inevitable, admitting them might signal that a news media brand is self-confident and strives for improvement.

In line with that, research in corporate communications indicates that an accountable response to a critical situation can prevent reputational damage. Coombs (Citation2006) Situational Crisis Communication Theory suggests denying allegations in case of unjustified criticism. However, if a crisis could have been avoided and thus marks a (more or less serious) violation of social norms, it should be admitted and dealt with, e.g. by apologizing and affirming that usually the process works well (Coombs Citation2006). Moreover, survey research shows that audiences find it especially important that news media openly admit to mistakes (van der Wurff and Schoenbach Citation2014). However, we do not yet know enough about the effects of denying or admitting mistakes in journalism on perceptions of brand quality and behavior intentions. We therefore ask

RQ2: How does admitting or denying accusations in user comments affect a) brand quality perception and b) behavioral intentions towards the news media brand compared to no journalistic reaction?

Transparency

Next to accountability, transparency is an increasingly important concept in digital journalism (Lowrey and Anderson Citation2005). Broadly, it can be defined as openness regarding journalistic work routines and revolves around two dimensions: disclosure and participatory transparency (Karlsson Citation2010; Meier and Reimer Citation2011). Participatory transparency refers to laypersons taking part in journalistic work, e.g. providing input on story ideas, while disclosure transparency involves all background information about journalistic work routines and how stories come about (Craft and Heim Citation2009; Lasorsa Citation2012; Reimer Citation2017).

For engagement moderation, disclosure transparency is particularly relevant. Next to admitting or denying mistakes, journalists can disclose editorial processes and explain why a mistake was made or not. Scholars have long demanded that journalism better explains its editorial processes and recent research finds that increased knowledge about how the media work indeed can increase perceived brand quality (Masullo, Curry, and Whipple Citation2019; also see Masullo and Tenenboim Citation2020) and media trust (Pingree et al. Citation2018; also see Lehrman Citation2021). Moreover, research on correcting misinformation suggests that giving explanations is especially persuasive. Seifert (Citation2002) argues that simply contesting information only generates contradictions and leaves “causal gaps,” thus not convincing recipients. Giving an explanation as to why something is incorrect closes this gap and therefore makes a correction more persuasive (Ecker, Lewandowsky, and Tang Citation2010; Johnson and Seifert Citation1994). It is likely that this effect is also at play when correcting or admitting accusations against news media. Thus, we pose

H2: A transparent journalistic explanation for a mistake increases brand quality perception compared to a journalistic reaction without a transparent explanation.

So far, research has not addressed the effects of journalistic reactions to media criticism on behavior intentions. Hence, we ask

RQ3: How does a transparent journalistic explanation affect behavioral intentions compared to a journalistic reaction without a transparent explanation?

Moderating Effect of Media Cynicism

We conducted our study in Germany, which presents a particularly interesting case for our research questions. German news media still enjoy relatively high trust (Hölig and Hasebrink Citation2017). However, in the past years, the country has seen increasing attacks against the media and public discussions around bias, quality, and trustworthiness, following media coverage of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict in 2014, the refugee crisis of 2015, and the COVID-pandemic (Obermaier Citation2020; Prochazka Citation2020). Famously, the term “lying press” was coined on the far-right end of the political spectrum (Reinemann, Fawzi, and Obermaier Citation2017).

In the wake of this debate, attitudes towards journalism have become more polarized: the number of people ambivalent towards the media has decreased and more people have become either more supportive of the media, defending journalism against sweeping accusations – or more negative and cynical (Schultz et al. Citation2020). Media cynicism is a destructive, across-the-board dissatisfaction with journalistic performance (Pinkleton et al. Citation2012; Strömbäck et al. Citation2020). A cynical stance towards societal institutions such as journalism is potentially harmful to democracy because cynical citizens assume that democratic institutions act harmfully for society, regardless of indications for or against it (Cappella and Jamieson Citation1997). In this opinion climate in Germany, we have reason to believe that attitudes towards news media in general play a major role in how media criticism in user comments and subsequent journalistic reactions affect recipients (Karlsson, Clerwall, and Nord Citation2017). Therefore, we ask to what extent our presumed effects depend on the individual level of media cynicism in

RQ4: How do the effects of media criticism and journalistic reactions to criticism in user comments interact with media cynicism?

Experimental research with a single exposure often leaves the question whether the results are stable over time. We therefore also investigate if the effects of critical comments and journalistic reactions are still present five days after exposure. Since behavioral intentions such as writing a comment or checking the facts of an article only make sense immediately after exposure, we only ask for quality perceptions in

RQ5: Are the effects of media criticism and journalistic reactions on brand quality perceptions still present after five days?

Method

Design, Stimulus and Participants

We conducted an online experiment in a randomized 2x2x2 between-subjects design. Participants were presented with a Facebook post of a fictitious newspaper (‘Aktuelle Rundschau’). To enable respondents to make an informed assessment of the brand, they were given a short fact sheet about the newspaper and a brief interview with its editor-in-chief. After that, respondents saw the Facebook post in which the brand shared an article on a fictitious study on citizens’ willingness to change their habits to reduce carbon emissions. Allegedly, the study was funded by the government. We used a study on the topic of sustainable behavior because it allows us to create believable criticism (regarding an error in the interpretation of the study’s data) as well as the possibility to admit and deny a mistake followed by an explanation.

Below the post, there was a critical user comment and a response comment from the editorial staff of the newspaper. The user comment accused the newspaper of an error in the article and assumed that this was caused either by hasty journalistic work (“You knitted this article with a hot needle”) or a lack of journalistic integrity, namely political independence (“You spoke the government’s mouth”) (factor 1: media criticism). In the response comment, the editorial staff either admitted the mistake (“We have to agree with your criticism. Correctly, the article should state that young people in particular want to change their habits”) or denied it (“We cannot agree with your criticism. Correctly, the article states that young people in particular want to change their habits and that the attitude in the general population differs only slightly”) (factor 2: journalistic reaction). In addition, the editorial staff provided either no further information or a transparent explanation for why the mistake occurred (“We should have checked the information by comparing it to the original study”) or explained why no mistake was made (“We have also compared the information with the original study”) (factor 3: journalistic explanation). In addition to the eight experimental groups, there were three control groups: one without comments at all and two with only the respective forms of criticism without a journalistic reaction.

The data was collected in July 2020, using a German noncommercial online access panel (Leiner Citation2016), resulting in a total of n = 1,155 participants. If respondents agreed to leave their email address, we invited them to a second questionnaire five days after they completed the survey (t2, n = 809). In the t2 survey, we measured quality perceptions of the brand again.Footnote1 From both t1 and t2 datasets, we excluded participants who agreed completely that they did not answer the questions seriously or said they just clicked through (Aust et al. Citation2013). Moreover, we removed participants who completed the questionnaires faster than half the median time of all respondents. After deletion, the final sample consisted of n = 1,107 (t1) and n = 759 participants (t2). 54% of the participants in t1 were female (age: M = 50 years, SD = 15.39) and 84% indicated to hold at least a high school degree. In the t2 sample, there were 53% female participants (age: M = 49 years, SD = 15.38) with 86% holding a high school degree. Data, stimulus materials, and R scripts for the study are available online at the OSF at https://osf.io/xqbu4/.

Measures

We measured the perceived journalistic quality of the media brand using 11 items that were shown to correlate highly with trust in news media at large (Prochazka Citation2020) (1 = does not apply at all to 5 = fully applies): “presents the facts correctly,” “reports on topics that are important for society,” “separates carefully between news and opinion,” “reports seriously and professionally,” “is independent,” “works and researches carefully,” “is honest with its readers,” “is transparent,” “does not take sides,” “lets different opinions have their say,” “is trustworthy”. All items loaded on one factor in an exploratory factor analysis and were collapsed to a mean index (t1: M = 3.44, SD = .72, α = .93, t2: M = 3.40, SD = .70, α = .94).

Participants indicated their behavioral intentions towards the news brand (5 items, 1 = very unlikely to 5 = very likely) with the following items: “check the information from the article with other media,” “chat with friends and family to check the information in the article” (collapsed into a mean index for fact checking, M = 2.72, SD = 1.19, α = .68), “read further articles in the ‘Aktuelle Rundschau’” (M = 2.74, SD = 1.27), “write a comment praising the ‘Aktuelle Rundschau’” (M = 1.47, SD = .86), “write a comment criticizing the ‘Aktuelle Rundschau’” (M = 1.37, SD = .78).

Following Ziegele et al. (Citation2018b) and Obermaier (Citation2020), media cynicism was measured using 7 items (1 = does not apply at all to 5 = fully applies): “The media hide many important events from the public,” “the media often deliberately report falsehoods,” “the media dictate what people should think,” “the media all report the same thing,” “journalists adapt their reporting to the interests of politics,” “politicians forbid journalists to report on certain topics,” “journalists and politicians are in cahoots.” Items loaded on one factor and were collapsed to a mean index (M = 2.31, SD = 0.87, α = .87).

Results of Treatment Checks

We used several measures to check whether the respondents could identify the experimental manipulations. In the control group without comments, 88% correctly indicated that there was no comment below the post; in the control groups with only one critical comment 96%, and in the conditions with two comments 88% correctly identified the number. Respondents in both criticism-conditions correctly agreed that the comment criticized incorrect information in the article (hasty work: M = 4.26, SD = 1.18; lack of integrity: M = 4.15, SD = 1.28, p = .16). Further, they mostly agreed that the article was a result of hasty work (hasty work: M = 4.36, SD = 1.11; lack of integrity: M = 4.26, SD = 1.23; p = .16), which is probably a result of the question wording that may apply to both types of criticism. Yet, respondents in the lack-of-integrity-condition correctly recognized that the comment criticized the news brand for being influenced by the government (M = 3.44, SD = 1.59) and those in the hasty-work-condition did not agree (M = 1.27, SD = 0.72; p < .001). Respondents in the admit-condition fully agreed that the journalists admitted to a mistake (M = 4.86, SD = 0.47) while those in the deny-condition did not (M = 1.08, SD = 0.34; p < .001). Vice versa, respondents in the deny-condition correctly identified that the journalists denied the accusation (M = 4.41, SD = 1.15) whereas those in the admit-condition did not (M = 1.10, SD = 0.48; p < .001). Lastly, respondents in the condition with an explanation indicated that they had seen an explanation for a mistake or why no mistake was made (M = 4.57, SD = 0.91), while respondents in the condition without an explanation agreed significantly less (M = 3.23, SD = 1.71, p < .001). However, the means suggest that respondents without an explanation still often believed to have seen an explanation, indicating that a mere reaction was probably also sometimes interpreted as such.

Results

To investigate our hypotheses and research questions, we use multiple regressions with the dummy-coded experimental groups as predictors. We add media cynicism as a continuous moderatorFootnote2 to all models (West, Aiken, and Krull Citation1996) to investigate whether the effects of media criticism and journalistic reactions depend on media cynicism (RQ4). Subsequently, we can specify the regions of the moderator where our experimental manipulations show significant effects using the Johnson-Neyman technique (Hayes Citation2018, 253). It is important to note that our experimental design is an incomplete design because some combinations of control and experimental conditions are not possible (e.g., control groups without reactions cannot contain a transparent explanation). Therefore, not all interactions between factors with control groups can be computed and we use separate regression models.

Effects of Media Criticism

First, we look at the effects of media criticism in comments on brand quality perception (H1a, H1b, RQ4). To avoid intervening effects from journalistic reactions, we only take the control groups into account, i.e. we compare the baseline group without comments with the two groups containing only the critical comments ().

Table 1. Effects of media criticism on brand quality perception.

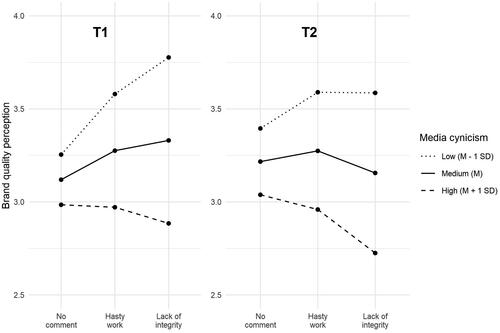

On average, the accusation of hasty work has no significant effect on the perceived quality of the media brand (b = 0.16, p = .11), but the interaction with media cynicism suggests different effects among media cynics and media supporters (bHasty work x cynicism = −0.19, p = .07)Footnote3. A simple slopes analysis shows that the accusation of hasty work even increases the perceived quality of the media brand among respondents with medium and low media cynicism (significant positive effect with p < .05 below media cynicism of 2.04). However, the accusation of hasty work does not significantly impact brand quality perceptions among media cynics (, left).

Similarly, the accusation of a lack of integrity shows a significant interaction with media cynicism (bIntegrity x cynicism = −0.36, p < .001). We can observe the same pattern as before, but even more pronounced: when the comment criticizes a lack of integrity, people low on media cynicism rate the brand even better, while media cynics follow the criticism and rate the brand worse (significant positive effect below media cynicism of 2.37, significant negative effect above 3.93) (, left).

People with positive attitudes towards the media in general thus apparently take a defensive stance towards the brand in the face of criticism, which results in a better perception of quality. Media cynics, on the other hand, are encouraged in their attitudes towards the media, follow the criticism in the comment and rate the brand worse. These results are contrary to the current state of research, which shows negative effects of media criticism on quality perceptions by and large. The difference in the present study may first be due to previous research not looking at differential effects along levels of media cynicism. Second, the results probably also reflect a change in public opinion in Germany over recent years. As stated above, attitudes towards news media are now more polarized and more Germans than a few years ago defend the media against sweeping accusations (Schultz et al. Citation2020).

In RQ5, we asked whether the effects of media criticism hold over time. To investigate this, we conducted the same analysis for the data collected five days after exposure. We observe the same effects of media criticism on quality perceptions; however, effect sizes of both interactions are down (and p-values up) considerably, especially regarding the interaction of hasty work with media cynicism (bHasty work x cynicism t2 = −0.16, p = .21; bIntegrity x cynicism t2 = −0.29, p = 0.02). Thus, the effect of an accusation of lack of integrity is still present after five days’ time, whereas the effect of an accusation of hasty work is less pronounced (, right). This supports the finding that accusations of a lack of integrity are more serious and have graver effects than relatively benign accusations.

When looking at the effects of media criticism on subsequent behavior intentions regarding the news media brand (RQ1), we find that when a comment criticizes a lack of integrity, the intention to fact-check the information from the article increases significantly (b = 0.40, p = .03) – this effect is independent of media cynicism (RQ4, see ). However, criticism in the comments does not affect intentions to read other articles from the brand or intentions to comment the article.

Table 2. Effects of media criticism on behavior intentions.

Effects of Journalistic Reactions

The differential effects of criticism in user comments on quality perceptions raise the question whether journalists can influence these effects with their own reactions in comments (RQ2a). Therefore, we first compare the different reactions in journalists’ comments (deny or admit) to the control groups without a journalistic response, including the interactions with the type of criticism and media cynicism ().

Table 3. Effects of journalistic reactions on brand quality perception.

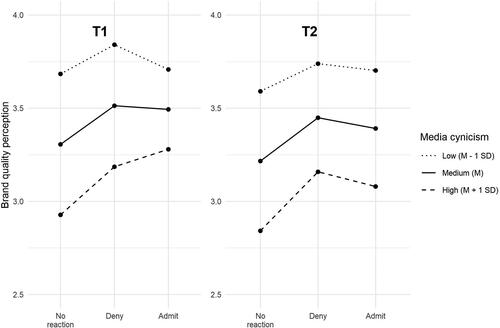

Denying a mistake increases the perceived quality of the brand compared to no reaction (b = 0.27, p < .001), irrespective of media cynicism. When journalists admit a mistake, there is a significant interaction with media cynicism (bAdmit x cynicism = 0.19, p < .001). For persons with low media cynicism, there is no significant change compared to no reaction (RQ4). However, among people with medium and high media cynicism (positive effect with p < .05 above 1.96 on the cynicism scale) there is an increase of brand quality perception when journalists admit a mistake compared to no reaction (, left). Thus, effects of a journalistic reaction on brand quality perception also depend on preexisting attitudes towards news media. Media cynics especially rate a media brand better when it admits mistakes, whereas media supporters only endorse it when a brand denies mistakes. However, not reacting to criticism in user comments results in the lowest brand quality scores across all respondents, suggesting that critical comments should not be left unattended. Notably, the effects of admitting and denying do not depend on the type of accusation, as evidenced by marginal and non-significant interactions.

When looking at the effects of journalistic reactions after five days (RQ5), the initial interaction has receded: now, denying (b = 0.24, p = .02) and admitting (b = 0.15, p = .13) (though not significantly) a mistake affect brand quality perception positively, regardless of media cynicism (, right). We assume that this is most likely a memory effect. After five days, respondents may have largely forgotten the content of the criticism and just remember that there was a reaction (especially so when it denied accusations) thus positively affecting their quality perceptions. This lends further support to the argument that reacting in any way is better than not reacting at all.

Regarding subsequent behavior intentions (RQ2b, RQ4), denying or admitting mistakes does not significantly affect the intention to check facts, the intention to read other articles from the same brand or to post a positive comment. Regarding the intention to post a negative comment, we again observe interactions of denying (bDeny x cynicism = −0.19, p = .02) and admitting a mistake (bAdmit x cynicism = −0.14, p = .08) with media cynicism. Denying mistakes reduces the likelihood to comment negatively among media cynics (significant negative effect above media cynicism of 3.32), whereas there is no significant effect among people with low and medium levels of cynicism. Admitting mistakes, on the other hand, only increases the likelihood to comment negatively among people with low to medium levels of cynicism (significant positive effect below media cynicism of 2.12) ().

Table 4. Effects of journalistic reactions on behavior intentions.

Effects of a Transparent Explanation

Lastly, we look at the effects of transparent explanations in journalists’ reactions to media criticism in user comments (H2, RQ3). We now employ a model with all experimental factors (without control groups) to investigate potential interaction effects between the factors that could not be included in previous models because of the incomplete design ().

Table 5. Effects of transparent explanations and other factors on brand quality perception – full model.

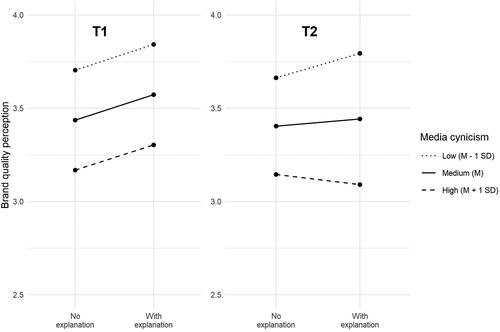

The media brand is rated better if the journalistic comments explain how the mistake was made or why no mistake was made (b = 0.22, p < .001) (, left). This applies regardless of the degree of media cynicism (RQ4), the type of criticism, and whether journalists deny or admit a mistake.Footnote4 Thus, providing a transparent explanation for reactions to media criticism seems to be the uniformly best strategy to deal with media criticism.

This is at least true for the initial effects of explanations. After five days, this main effect subsided (b = 0.16, p = .10) (, right). It is, however, still present in combination with denying a mistake (bExplanation x admit = −0.21, p = .05). Thus, the effect of a transparent explanation only increases brand quality perception five days after exposure if it was combined with denying a mistake (RQ5).

However, giving transparent explanations does not impact behavioral intentions (RQ3, RQ4). There are no effects of an explanation on fact-checking the article, reading further articles from the same brand, or commenting on the article ().

Table 6. Effects of transparent explanations and other factors on behavior intentions – full model.

Discussion

In this article, we investigated how media criticism in user comments and journalistic reactions to these comments affect the perceived quality of a news media brand and behavior intentions of its readers. Media criticism in comments (without journalistic reactions) affected quality perceptions of the news media brand dependent on media cynicism. Among respondents with a cynical attitude towards the media, we found the damaging effect of criticism that previous studies had detected. However, we also found that respondents with lower media cynicism rated a news media brand better when comments were critical. This shows that preexisting attitudes towards the news media play a vital role in how critical comments affect recipients. Opinions towards news media in Germany are already polarized with a majority supporting the media but a strong minority of media cynics (Schultz et al. Citation2020). Our study shows that critical comments may exacerbate this polarization: media cynics may become more cynical when confronted with criticism and media supporters may increase their support. This is especially true when users fundamentally criticize the media since the effects were more pronounced for accusations of a lack of integrity than for hasty work – and persisted five days after exposure, suggesting that these effects are long-lasting. Polarization may further be intensified by the fact that accusations of a lack of integrity increased the intention to check facts from the article, since this may lead to increased selective exposure to like-minded content both among media cynics and supporters.

However, journalists can mitigate these effects. Admitting and denying mistakes through own comments by the news media brand both showed an increase in brand quality perception. While denying mistakes increased quality perception independent of media cynicism, admitting only did so among media cynics. It remains open, however, if this translates to reduced media cynicism at large or if cynics just made an exception for one news media brand. Nevertheless, the brand was rated worst when journalists did not react to criticism among both groups. Hence, it is not a good strategy for news organizations to leave critical comments unattended. Rather, journalists should engage with critical comments and admit or deny mistakes where it is due. However, two other findings also support that it might be an especially viable strategy in dealing with criticism to deny mistakes and stand up for journalistic decisions (see Pingree et al. Citation2018 for a related argument). First, the effect of denying on brand quality perceptions was still present five days after exposure. Second, media cynics were less prone to comment negatively when a mistake was denied. Moreover, in a social media environment, it is certainly worth considering that journalistic responses to media criticism may result in the critical comments being displayed higher up in the discussion thread due to algorithmic amplification of official comments. This could increase the likelihood of exposure of other readers to media criticism, but also to the journalistic reactions. Thus, future research could try to use field experiments in a live social media environment to test the effects in a more naturalistic setting.

Moreover, transparent explanations for why the news brand did or did not make a mistake unconditionally increased the perceived brand quality. It did so regardless of the accusation, regardless of whether the mistake was admitted or denied and – most notably – regardless of media cynicism. Thus, a main contribution of our study is that accountability and transparency indeed gain merit for journalism that wants to be trustworthy in digital environments. Yet, these effects seem to be rather short-lived, since they were a lot weaker after five days and only present in combination with denying a mistake. Thus, it seems that transparent explanations must be repeated more often to better stay in memory.

Of course, our study is not without limitations. First, we used a sample where most respondents were highly educated and thus probably are more interested in current affairs and have a more nuanced perspective towards the news media. Thus, future research should try and test whether the effects also hold beyond this sample.

Second, our research questions limited the possible accusations in user comments as well as the journalistic responses. We had to choose a relatively mild accusation (a mistake in how the details of a study were reported) to be able to both use different reasons for this accusation and for the journalists to plausibly deny and admit the mistake and give a comprehensible explanation. However, accusations towards news media are often less ambivalent and obviously sometimes true, so that denying a mistake would not be plausible. The effects we found may therefore be limited to circumstances where it is not clear whether the news brand made a mistake or not. Future research should take the nature of accusations into account and look for different effects of different kinds of mistakes that users criticize in comments.

Third, we deliberately used a fictitious news brand and did not provide the article in question. On the upside, this approach allows us to investigate the effects of comments without interfering variables like brand images or perceptions of the article. On the downside, respondents must rate the quality of a news brand they know little about. We are confident that providing a short background story on the brand and an interview with the editor-in-chief minimized this problem, but we nevertheless do not know from our study whether the effects may be generalized to more well-known brands. Thus, future studies should investigate if and how critical comments and journalistic reactions affect quality perceptions depending on existing brand images. Moreover, in follow-up studies respondents should be given opportunity to check the information in the article themselves.

Fourth, our experiment only contained a one-time confrontation with the stimulus. We believe this adds to external validity because Internet users are often only confronted with single response comments and do not read multiple reactions to media criticism, simply because they only form a comparatively small fraction of all comments. Moreover, the fact that we detected effects by using a one-time exposure suggests that these effects exist outside the experimental setting. Nevertheless, we cannot make any statements about how repeated, long-term exposure to media criticism and subsequent journalistic reactions in user comments shape perceptions of brand quality. Future studies should address this and use longitudinal studies as well as different stimuli with different topics and comments. We also exploratively assessed effects of media-critical comments on a selection of behavioral intentions, namely fact checking, further media use, and writing user comments. Subsequent studies should thus expand the range of possible behaviors in response to media-critical comments and survey or track actual behavior. Lastly, future studies could also contribute to a better understanding as to how these effects come about, investigate psychological mechanisms that explain the effects and look at possible boundary conditions such as involvement or need for cognition.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our study gives solid empirical evidence that journalism can indeed positively influence how it is perceived by being accountable and transparent to users. Since the audience also increasingly articulates a desire for more dialogue and openness of news brands (Loosen, Reimer, and Hölig Citation2020), it seems timely for journalism to develop strategies and editorial policies to foster an editorial culture of transparency and engagement in user comments and beyond.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Julian Unkel for allowing us to use his unpublished, interactive Facebook mockup for the online survey software SoSci Survey. We are also grateful to him for his support in customizing the questionnaire for our project.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 For reasons of completeness, we also measured behavioral intentions again, even though we are convinced that looking for effects on behavioral intentions such as writing a comment or reading more articles only makes sense immediately after the exposure.

2 Media cynicism was mean centered for all analyses. Thus, the first-order effects of our experimental factors can be interpreted as the effect among respondents with average levels of media cynicism (Hayes Citation2018, p. 310).

3 We opted to probe interactions less restrictively with p values below .10, since this points to significant effects in the respective subgroups (for a discussion, see Hayes Citation2018, p. 259).

4 The other effects in Table 5 mirror the previously discussed results. However, note that compared to H1, we do not observe a significant interaction between lack of integrity and media cynicism, because in the first analysis we only used the control groups. When looking at all groups and the difference between the two types of criticism, the effect vanishes. This further suggests that journalistic reactions mitigate the negative effects of media criticism.

References

- Aust, F., B. Diedenhofen, S. Ullrich, and J. Musch. 2013. “Seriousness Checks Are Useful to Improve Data Validity in Online Research.” Behavior Research Methods 45 (2): 527–535.

- Barnidge, M., B. Sayre, and H. Rojas. 2015. “Perceptions of the Media and the Public and Their Effects on Political Participation in Colombia.” Mass Communication and Society 18 (3): 259–280.

- Cappella, J. N., and K. H. Jamieson. 1997. Spiral of Cynicism. The Press and the Public Good. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cheung, C. M., and D. R. Thadani. 2012. “The Impact of Electronic Word-of-Mouth Communication. A Literature Analysis and Integrative Model.” Decision Support Systems 54 (1): 461–470.

- Coombs, W. T. 2006. “The Protective Powers of Crisis Response Strategies: Managing Reputational Assets during a Crisis.” Journal of Promotion Management 12 (3–4): 241–260.

- Craft, S., and K. Heim. 2009. “Transparency in Journalism: Meanings, Merits, and Risks.” In The Handbook of Mass Media Ethics, edited by L. Wilkins and C. G. Christians, 217–228. New York: Routledge.

- Craft, S., T. P. Vos, and J. D. Wolfgang. 2016. “Reader Comments as Press Criticism: Implications for the Journalistic Field.” Journalism 17 (6): 677–693.

- Dohle, M. 2018. “Recipients’ Assessment of Journalistic Quality. Do Online User Comments or the Actual Journalistic Quality Matter?” Digital Journalism 6 (5): 563–582.

- Ecker, U. K. H., S. Lewandowsky, and D. T. W. Tang. 2010. “Explicit Warnings Reduce but Do Not Eliminate the Continued Influence of Misinformation.” Memory & Cognition 38 (8): 1087–1100.

- Fawzi, N., and C. Mothes. 2020. “Perceptions of Media Performance: Expectation-Evaluation Discrepancies and Their Relationship with Media-Related and Populist Attitudes.” Media and Communication 8 (3): 335–347.

- Hanitzsch, T., A. Van Dalen, and N. Steindl. 2018. “Caught in the Nexus: A Comparative and Longitudinal Analysis of Public Trust in the Press.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (1): 3–23.

- Hayes, A. F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Hölig, S., and U. Hasebrink. 2017. “Germany.” In Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017, edited by N. Newman, R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, D. A. Levy, and R. K. Nielsen, 70–71. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital%20News%20Report%202017%20web_0.pdf.

- Holt, K., T. U. Figenschou, and L. Frischlich. 2019. “Key Dimensions of Alternative News Media.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 860–869.

- Hovland, I., L. Janis, and H. H. Kelley. 1953. Communication and Persuasion: Psychological Studies of Opinion Change. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Johnson, H. M., and C. M. Seifert. 1994. “Sources of the Continued Influence Effect: When Misinformation in Memory Affects Later Inferences.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 20 (6): 1420–1436.

- Karlsson, M. 2010. “Rituals of Transparency.” Journalism Studies 11 (4): 535–545.

- Karlsson, M., C. Clerwall, and L. Nord. 2017. “Do Not Stand Corrected: Transparency and Users’ Attitudes to Inaccurate News and Corrections in Online Journalism.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 94 (1): 148–167.

- Kümpel, A. S., and N. Springer. 2016. “Commenting Quality. Effects of User Comments on Perceptions of Journalistic Quality.” Studies in Communication and Media 5: 353–366.

- Kümpel, A. S., and J. Unkel. 2020. “Negativity Wins at Last: How Presentation Order and Valence of User Comments Affect Perceptions of Journalistic Quality.” Journal of Media Psychology 32 (2): 89–99.

- Lasorsa, D. 2012. “Transparency and Other Journalistic Norms on Twitter: The Role of Gender.” Journalism Studies 13 (3): 402–417.

- Lehrman, S. 2021. “The 8 Trust Indicators.” The Trust Project. https://thetrustproject.org/#indicators

- Leiner, D. J. 2016. “Our Research’s Breadth Lives on Convenience Samples. A Case Study of the Online Respondent Pool “SoSci Panel.” Studies in Communication and Media 5 (4): 367–396.

- Lewis, S. C., A. E. Holton, and M. Coddington. 2014. “Reciprocal Journalism.” Journalism Practice 8 (2): 229–241.

- Loosen, W., J. Reimer, and S. Hölig. 2020. “What Journalists Want and What They Ought to Do: (in)Congruences between Journalists’ Role Conceptions and Audiences’ Expectations.” Journalism Studies 21 (12): 1744–1774.

- Loosen, W., and J. -H. Schmidt. 2012. “(Re-)Discovering the Audience.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (6): 867–887.

- Lowrey, W., and W. Anderson. 2005. “The Journalist behind the Curtain: Participatory Functions on the Internet and Their Impact on Perceptions of the Work of Journalism.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 10 (3).

- Masullo, G. M., and J. Kim. 2021. “Exploring “Angry” and “Like” Reactions on Uncivil Facebook Comments That Correct Misinformation in the News.” Digital Journalism 9 (8): 1103–1120.

- Masullo, G. M., M. J. Riedl, and Q. Elyse Huang. 2020. “Engagement Moderation: What Journalists Should Say to Improve Online Discussions.” Journalism Practice 30 (1): 1–17.

- Masullo, G. M., A. Curry, and K. Whipple. 2019. Building Trust: What Works for News Organizations. Austin, TX: Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/CME-Building-Trust-Final.pdf

- Masullo, G. M., and O. Tenenboim. 2020. Gaining Trust in TV News. Austin, TX: Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/research/trust-in-tv-news/

- McQuail, D. 2003. Media Accountability and Freedom of Publication. New York: Oxford University Press.

- McQuail, D. 2013. Journalism and Society. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Meier, K., and J. Reimer. 2011. “Transparenz im Journalismus.” Publizistik 56 (2): 133–155.

- Naab, T. K., D. Heinbach, M. Ziegele, and M. ‑T. Grasberger. 2020. “Comments and Credibility: How Critical User Comments Decrease Perceived News Article Credibility.” Journalism Studies 21 (6): 783–801.

- Neuberger, C. 2014. “The Journalistic Quality of Internet Formats and Services.” Digital Journalism 2 (3): 419–433.

- Neurauter-Kessels, M. 2011. “Im/Polite Reader Responses on British Online News Sites.” Journal of Politeness Research. Language, Behaviour, Culture 7 (2): 187–214.

- Obermaier, M. 2020. Vertrauen in journalistische Medien aus Sicht der Rezipienten. Zum Einfluss von soziopolitischen und performanzbezogenen Erklärgrößen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Pingree, Raymond J., Brian Watson, Mingxiao Sui, Kathleen Searles, Nathan P. Kalmoe, Joshua P. Darr, Martina Santia, and Kirill Bryanov. 2018. “Checking Facts and Fighting Back. Why Journalists Should Defend Their Profession.” PloS One 13 (12): e0208600–14.

- Pinkleton, B. E., E. W. Austin, Y. Zhou, J. F. Willoughby, and M. Reiser. 2012. “Perceptions of News Media, External Efficacy, and Public Affairs Apathy in Political Decision Making and Disaffection.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 89 (1): 23–39.

- Prochazka, F., and W. Schweiger. 2016. “Medienkritik Online. Was Kommentierende Nutzer Am Journalismus Kritisieren.” Studies in Communication and Media 5: 454–469.

- Prochazka, F., P. Weber, and W. Schweiger. 2018. “Effects of Civility and Reasoning in User Comments on Perceived Journalistic Quality.” Journalism Studies 19 (1): 62–78.

- Prochazka, F. 2020. Vertrauen in Journalismus unter Online-Bedingungen: Zum Einfluss von Personenmerkmalen, Qualitätswahrnehmungen und Nachrichtennutzung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-30227-6

- Reimer, J. 2017. “Vertrauen Durch Transparenz? Potenziale Und Probleme Journalistischer Selbstoffenbarung.” In Öffentliches Vertrauen in der Mediengesellschaft, edited by M. Haller, 139–157. Köln: Herbert von Halem Verlag.

- Reinemann, C., N. Fawzi, and M. Obermaier. 2017. “Die „Vertrauenskrise“ der Medien – Fakt oder Fiktion? Zu Entwicklung, Stand und Ursachen des Medienvertrauens in Deutschland.” In Lügenpresse: Anatomie eines politischen Kampfbegriffs, edited by V. Lilienthal and I. Neverla, 77–94. Köln: Kiepenheuer & Witsch.

- Risch, J., and R. Krestel. 2020. “A Dataset of Journalists' Interactions with Their Readership.” In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, 3117–3124.

- Rojas, H. 2010. “Corrective” Actions in the Public Sphere. How Perceptions of Media and Media Effects Shape Political Behaviors.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 22 (3): 343–363.

- Rossini, P. 2020. “Beyond Incivility: Understanding Patterns of Uncivil and Intolerant Discourse in Online Political Talk.” Communication Research. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220921314

- Santana, A. D. 2016. “Controlling the Conversation. The Availability of Commenting Forums in Online Newspapers.” Journalism Studies 17 (2): 141–158.

- Schultz, T., M. Ziegele, I. Jakobs, N. Jackob, O. Quiring, and C. Schemer. 2020. “Medienzynismus weiterhin verbreitet, aber mehr Menschen widersprechen. Mainzer Langzeitstudie Medienvertrauen 2019.” Media Perspektiven 50 (6): 322–330.

- Seifert, C. M. 2002. “The Continued Influence of Misinformation in Memory: What Makes a Correction Effective?” The Psychology of Learning and Motivation 41: 265–292.

- Springer, N., I. Engelmann, and C. Pfaffinger. 2015. “User Comments: Motives and Inhibitors to Write and Read.” Information, Communication & Society 18 (7): 798–815.

- Strömbäck, J., Y. Tsfati, H. Boomgaarden, A. Damstra, E. Lindgren, R. Vliegenthart, and T. Lindholm. 2020. “News Media Trust and Its Impact on Media Use: Toward a Framework for Future Research.” Annals of the International Communication Association 44 (2): 139–156.

- Stroud, N. J., J. M. Scacco, A. Muddiman, and A. L. Curry. 2015. “Changing Deliberative Norms on News Organizations’ Facebook Sites.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20 (2): 188–203.

- Toff, B., and A. Kalogeropoulos. 2020. “All the News That’s Fit to Ignore.” Public Opinion Quarterly 84 (S1): 366–390.

- Urban, J., and W. Schweiger. 2014. “News Quality from the Recipients’ Perspective.” Journalism Studies 15 (6): 821–840.

- van der Wurff, Richard, and Klaus Schoenbach. 2014. “Civic and Citizen Demands of News Media and Journalists: What Does the Audience Expect from Good Journalism?” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 91 (3): 433–451.

- Vanacker, B., and G. Belmas. 2009. “Trust and the Economics of News.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 24 (2–3): 110–126.

- Weber, P., F. Prochazka, and W. Schweiger. 2019. “Why User Comments Affect the Perceived Quality of Journalistic Content.” Journal of Media Psychology 31 (1): 24–34.

- West, S. G., L. S. Aiken, and J. L. Krull. 1996. “Experimental Psychology Designs: Analyzing Categorical by Continuous Variable Interactions.” Journal of Personality 64 (1): 1–48.

- Wyatt, W. N. 2007. Critical Conversations. A Theory of Press Criticism. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Yale, R. N., J. D. Jensen, N. Carcioppolo, Y. Sun, and M. Liu. 2015. “Examining First- and Second-Order Factor Structures for News Credibility.” Communication Methods and Measures 9 (3): 152–169.

- Ziegele, M., and P. B. Jost. 2020. “Not Funny? The Effects of Factual versus Sarcastic Journalistic Responses to Uncivil User Comments.” Communication Research 47 (6): 891–920.

- Ziegele, M., P. Jost, M. Bormann, and D. Heinbach. 2018a. “Journalistic Counter-Voices in Comment Sections: Patterns, Determinants, and Potential Consequences of Interactive Moderation of Uncivil User Comments.” Studies in Communication and Media 7 (4): 525–554.

- Ziegele, M., T. Schultz, N. Jackob, V. Granow, O. Quiring, and C. Schemer. 2018b. “Lügenpresse-Hysterie ebbt ab. Mainzer Langzeitstudie „Medienvertrauen.” Media Perspektiven 48 (4): 150–162.

- Ziegele, M., N. Springer, P. Jost, and S. Wright. 2017. “Online User Comments across News and Other Content Formats: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, New Directions.” Studies in Communication and Media 6 (4): 315–332. Editorial.