Abstract

This article introduces the Generative Dialogue Framework (GDF) and explores its potential as a pedagogical intervention, one that could help reimagine the future of engaged journalism by bringing design-thinking practices, creativity, and deep-listening modalities into play. The framework is developed through design thinking and builds around principles from the field of design. It uses virtual meeting technologies to organize small-group conversations, allows for creative and playful activities to help people share stories and feelings, and aims to create an ambient atmosphere of mutual understanding and co-creative problem-solving. With this article, we aspire to initiate a conversation around the value of “pollinating” journalism studies with concepts and principles from design thinking and facilitation so that journalists could become empowered to connect with their audiences with greater empathy and compassion and thereby surface diverse and rich lived experiences using more active and reflective listening skills. To test the framework’s potential for enhancing engaged journalism curricula, we collaborated with 17 journalism students at a U.S. university in a series of activities, from initial training on the platform to hosting a conversation using the GDF to ultimately producing a news story based on the insights acquired through this design-centered approach.

Introduction and Conceptual Overview

In recent decades, as many journalism observers have worried about the apparent disconnection between news organizations and the communities they serve (for an overview, see Nelson Citation2021), a variety of concepts have been introduced to describe how journalists might develop more meaningful relationships with audiences. The idea, broadly speaking, is that improving how journalists understand their communities and their needs might lead to improved forms of journalism, which ultimately may help correct problems such as declining trust in news that have challenged the press as an institution in many western democracies. Drawing inspiration from the public/civic journalism movement of the 1990s, these approaches to reforming journalism have been framed, among others, as participatory (Singer et al. Citation2011), reciprocal (Lewis, Holton, and Coddington Citation2014), collaborative (Bruns Citation2005), and networked (Jarvis Citation2006)—each organized around the possibilities for digital media, in particular, to allow more people to share their stories, connect with one another, and participate in the shaping of news narratives. More recently, the concept of engaged journalism has been embraced by scholars and practitioners alike as a promising development (Ferrucci, Nelson, and Davis Citation2020; Lawrence, Radcliffe, and Schmidt Citation2018, Lawrence et al. Citation2019; Nelson Citation2018; Schmidt and Lawrence Citation2020; Wenzel Citation2019, Citation2020)—indeed, as something of “public journalism 2.0” that might finally realize decades-old ambitions to resituate journalism in a way that would make it more responsive to, and reflective of, communities (Schmidt, Nelson, and Lawrence Citation2022). Engaged journalism in this sense—which is different from a broader industry focus on “audience engagement” as captured primarily through digital audience analytics (Zamith Citation2018)—has thus been described as “an inclusive practice that prioritizes the information needs and wants of the community members it serves, creates collaborative spaces for the audience in all aspects of the journalistic process, and is dedicated to building and preserving trusting relationships between journalists and the public” (Green-Barber and McKinley Citation2019).

That sounds attractive in the abstract, but how do journalists actually develop such relationships? A growing body of scholarship has shown that the work of reorienting journalism around engagement with communities has proven elusive. Some journalists have resisted it, much as they have previous attempts at incorporating greater audience participation (e.g., Schmidt and Lawrence Citation2020; Xia et al. Citation2020). News organizations have struggled to retool their routines around engagement (e.g., Nelson Citation2018, Citation2021). And, there is a misalignment between engaged journalism theory and practice (Schmidt, Nelson, and Lawrence Citation2022), which may suggest a mismatch between what journalists believe people want from them and what audiences actually desire (cf. Coddington, Lewis, and Belair-Gagnon Citation2021), further compounding the journalist–audience disconnection. What is needed, therefore, is advancements in tangible tools and techniques that can help journalists put engagement into practice in ways not yet realized.

In this article, we introduce a first-of-its-kind Generative Dialogue Framework (GDF from here forward) and review its potential as a pedagogical intervention for advancing engaged journalism by drawing on concepts and principles from the fields of design and facilitation. This framework employs a structured process and a toolkit—which can be implemented in-person or virtually—to organize small-group conversations, allow for creative and playful activities (such as drawing) to help people share stories and feelings, and create an ambient atmosphere of mutual understanding and co-creative problem-solving. The GDF is built not on journalism studies literature or journalism-centric concepts but rather on principles from the field of design that inform a more bottom-up, user-centric orientation, one that uses design-thinking approaches to evaluating user experience. Because engaged journalism is premised on journalists tapping into the needs and concerns of their communities, the GDF tool that we outline here is designed to help journalists get out of their usual interviewing routines and develop new approaches for helping people feel seen and heard (cf. Robinson, Jensen, and Dávalos Citation2021). Moreover, the dialogic framework fits with two related trends in journalism research and practice: the “emotional turn” (Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2020) and the “audience turn” (Costera Meijer Citation2020). The GDF does so by encouraging the sharing of stories and feelings and lived experiences, all toward the aim of improving understanding at the intersection of journalists and their communities.

In particular, we highlight the need for journalists to engage in deep listening as part of a systematic effort to become more empathetic by exploring the world the way others see it and co-creating meaning with their audiences instead of creating it for them. While our goal in this article is to demonstrate the value of the framework for familiarizing journalism students with the fields of design, facilitation, and community-listening, we also aspire to open up a new way of thinking about the gathering of data through deep listening, conversation, and dialogue—in effect, expanding the repertoire of listening skills that journalists will need to cultivate in the future. The journalistic interview generally begins with a specific purpose—even an agenda—“to unearth quotes or sound bytes that add color to a journalist’s reporting” (DeJarnette Citation2016). In contrast, deep listening is a process that allows journalists to tune into and surface what community members say is important and meaningful for them.

Moving beyond just suggesting a different approach for journalists to engage with their audiences, we introduce a structure for deep listening and dialogue with members of the community, alongside the opportunity to make meaning out of a diversity of opinions and perspectives, one that advocates for an increased complexity rather than a conforming simplicity. In a world where journalism looks for coherence, clarity, and tension avoidance, we highlight the urgency of “reviving complexity in a time of false simplicity” (Ripley Citation2019). Dialogue, reflective listening, and connection through values rather than facts can be tools for “complexifying” issues (Grant Citation2021, 165), helping people tackle vexing problems by first seeing the world as complicated and full of gray.

In the sections that follow, we illustrate how the GDF works and how it is built on principles of design and group facilitation. We then explain how we envision the GDF as an example of a potential pedagogical intervention to be introduced to journalism curricula, one that can support emerging journalists in connecting with their audiences with greater empathy and compassion as well as in designing interviewing practices that embrace an ambiance of dialogue and mutual understanding rather than the traditional interviewer-interviewee dynamic. To review the GDF’s potential impact as a pedagogical tool, we worked with a group of 17 students during the spring term of 2021. In what follows, we review how the students experienced the GDF process, including their experimenting with active and reflective listening skills to surface participants’ experiences and perspectives and use that information as leads to develop their news stories instead of predetermining what the story angle should be. We conclude by discussing how the study and practice of engaged journalism could benefit from a more intentional conversation with concepts and principles from the fields of design and facilitation.

Design Thinking as a Conceptual Guide

In this article, we look to design—and design thinking, in particular—as a method for creating innovative frameworks for practicing engaged journalism. Our goal is to develop and illustrate an actionable framework and provide future journalists with the skills and tools to listen deeply to their communities. In what follows, we demonstrate how the GDF can support journalists in engaging with their audiences in a meaningful way. With creativity being a defining aspect of design research, we developed, prototyped, and tested the GDF as an approach that empowers journalists to hone their listening skills as a way to invite deep and constructive conversations with their audiences.

To design the GDF, we built on design thinking, “a methodology that imbues the full spectrum of innovation activities with a human-centered design ethos” (Brown Citation2020: 1). Design thinking plays a prominent role in the framework on multiple levels. First, we employ design thinking to address “wicked problems” (Buchanan Citation1992) and complexity through creativity. Second, we introduce capabilities and skills that stem from design thinking, and which can prove powerful tools in the reflective listening process: to learn from others, navigate ambiguity, synthesize information, build and craft intentionally, and communicate deliberately (Kelley and Kelley Citation2013). Finally, we follow the phases of the design-thinking micro-cycle: understand, observe, define points of view, ideate, develop prototypes, test, and reflect (Lewrick, Link, and Leifer Citation2020). This process lets us explore, design, and imagine possibilities for conversational interactions between journalists and their audiences.

Building on a design-led process, the suggested framework we outline here is premised on a participatory mindset. It aims at engaging communities in a facilitated dialogue to explore a topic together and craft storytelling in uniquely creative ways. It is a human-centered approach to understanding people’s needs and harnessing the power of personal stories. Personal stories can help us understand the origin of people’s perceptions about complex issues and the impact of their personal experiences and narratives on their views and perspectives. The outcome of this design process is a dialogic experience that allows participants to engage with the topic under discussion individually and collectively and invites them to develop meaningful connections with others in the group who come from different backgrounds and who enter the dialogue space with diverse identities, beliefs, and personal experiences.

The Generative Dialogue Framework

With these goals in mind, the first author created the framework and a first-of-its-kind toolkit of generative activities, utilizing custom-designed visual prompts and semantic cues to construct an online space for hosting and facilitating such dialogic experiences.Footnote1 The framework and the toolkit were developed, tested, and iterated between March and July 2020, during which time the first author faced the challenge of having to move a series of in-person focus group-style conversations for her research on misinformation and childhood vaccines online because of the coronavirus pandemic. The original conversations were designed to be facilitated in-person by implementing an experiential and embodied process of interaction and engagement between the researcher and the participants as well as among the participants themselves. The process that was originally designed could not be seamlessly replicated online and still maintain its interactive and embodied design.

Through several iterations to address the different affordances of technology, the first author designed the process from scratch by employing the use of the virtual collaboration platform Mural (see https://www.mural.co/) and designing a new visual template with a set of generative activities that could be implemented online. The process was tested by the first author in facilitating 36 focus groups that were conducted over the videoconferencing platform Zoom and built around the framework’s structured step-by-step approach that was designed and visualized on Mural. The original objective of the research in 2020 was to study the origins of misinformation and misconceptions surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine by creating a space for participants to share their experiences around the topic as a means of gaining insight into their different perceptions, concerns, and misconceptions. After overwhelmingly positive feedback from the participants reflecting on their experience interacting with the researcher and each other in this intentional and creative way, the first author sought to explore other applications for the framework, ones that would go beyond the facilitation of focus groups as audience research and could be embedded into different professional practices. With this objective in mind, the first author conceptualized the idea of testing the framework and the toolkit to advance the study and the practice of engaged journalism. In particular, we wanted to test its efficacy as a pedagogical intervention for journalism students by exploring how such frameworks and toolkits can helpthem invite information from non-expert sources and actively connect with their audiences through active and reflective listening modalities (cf. Robinson, Jensen, and Dávalos Citation2021).

The designed experience includes seven steps, which serve as a guided dialogue process (see ). Each step is associated with an open-ended question and a generative activity. For every topic discussed, participants are involved in an activity that allows them to self-reflect, interact with the visual prompts, and actively construct meaning before engaging with the group to develop their thoughts and arguments. The generative activities vary from drawing with markers on paper to live brainstorming sessions to interactive, immersive tasks supported by the use of technology.

The philosophy of dialogue, as introduced by Buber (Citation1970, Citation1998), inspires the framework, which aims to design of a space in which people connect across differences, backgrounds, and opinions. Everyone is invited to share their lived experiences through storytelling as a point of departure, in comparison to debating facts (“my facts vs. your facts”), thus better enabling people to connect across divides (Kubin et al. Citation2021). The power of dialogue, listening, and personal storytelling has been well documented across disciplines. Personal stories invite dialogic moments because they facilitate the negotiation of one’s self-presentation while providing an effective space for perspective-taking and dealing with moral, cultural, and political differences (Black Citation2008; Stains Citation2014). Small-group discussions can also foster critical thinking, evaluation of ideas, analysis of evidence, and decision-making (Barge Citation2002).

The GDF is further conceptually influenced by Bohm’s (Citation1996) seminal contribution to the field of dialogue studies, which inquires into individual and collective presuppositions, beliefs, and feelings to afford a more creative form of collective knowing, learning, and thinking together (Gunnlaugson Citation2014). Building on Bohm’s work, Isaacs (Citation1999) and Scharmer (Citation2009) in organizational studies offer ways of understanding the concept of generative dialogue as a form of communication in which people let go of their positions and engage in a collective presence where ideas emerge collaboratively and build upon one another.

This article thus advances the concept of generativity by situating these conversations in a practical professional context where the quality of processes that lead to their emergence are as significant as the quality of data and results generated by them. In particular, we introduce generative methods and tools—that is, tangible frameworks for conversation facilitation—that may more fully elicit emotional responses and expressions from people while uncovering collective meaning and understanding. Generative tools encourage the discovery of a new language, so to speak, that is created from both visual and verbal components, allowing researchers and participants to communicate and interact visually with each other. This approach enables participants to develop artifacts that creatively express their ideas, thoughts, and feelings by introducing co-creation as a mindset, method, and tool.

Design Principles of the Generative Dialogue Framework

The GDF builds on five design principles, synthesized below. These describe our approach to dialogue as a form of group communication, and lay the foundation for the framework’s implementation. In what follows, each principle is analyzed and linked to its contribution to the framework.

Principle 1: Each Group Is a System

The first principle of the framework speaks to systems thinking and the idea that a system is more than the sum of its parts (Meadows Citation2008). This principle provides a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than static “snapshots” (Senge Citation1990, 88). The discipline of systems thinking considers systems dynamics in their continual transformation and evolution and recognizes such a role in thinking, knowledge creation, communication, prediction, and the mastering of complexity.

Bringing systems thinking to our context of dialogue facilitation helps us interpret the group as more than a sum of its parts—as more than a collection of participating individuals. In a group dialogue, participants hold two roles: one as individuals with their own thoughts, perspectives, and perceptions, and another as parts of the whole group in which diverse dynamics and interactions take place. In that system, participants think collectively about the topic under discussion and co-create the experience of that dialogue. The facilitators also interact with the participants on two levels: on one level, they interact with each participant individually, taking into consideration the different personality traits, backgrounds, characteristics, and perspectives; on another level, they interact with the group as a collective entity that produces collective knowledge by blending the diversity of each participant’s lived experience. They make sure to provide space and time for the interactions within the group so that it moves through transitions seamlessly; provide a safe and trusted space for all participants to share their stories and experiences; and facilitate the dynamics within the group so that participants feel seen and heard.

Principle 2: Creativity as an Entry Point to Dialogue

Creativity and playfulness are key elements in the GDF—creativity because it correlates with producing innovative outcomes and generating ideas at both individual and group levels (Ulibarri et al. Citation2020, 276), and playfulness because of its ability to “reambiguate” the world (Sicart Citation2017, 28), making it less formalized and explained, and thereby more generatively open to interpretation and exploration.

Creativity and playfulness are featured in the design of the visual scaffold of the GDF that supports the dialogue as well as in the nature of the designed generative activities. Drawing, for example, is suggested as part of a creative and playful process, which opens up different perspectives, creates clarity, promotes memory, and is personal and authentic (Brand Citation2017; Qvist-Sørensen and Baarstrup Citation2019).

Principle 3: Build on Collective Understanding

One of the core challenges in a group conversation is the predispositions and perceptions of the topic that participants bring to the table, especially on complicated or polarizing issues. People’s diverse “frames,” the interpretations they use to make sense of an issue or event (Goffman Citation1974), can affect how the topic is perceived and discussed, and can turn the conversation into untuned parallel monologues. The objective of the GDF is to listen deeply to understand each other and learn from one another’s experiences and not to try to persuade others, solve each other’s problems, or find points of agreement. We foster these conditions by allowing the group to explore the topic together by building on their collective understanding.

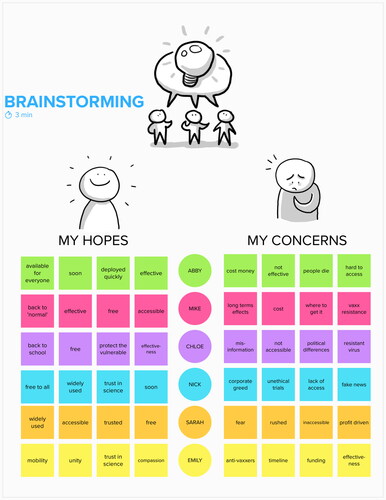

To set the stage, facilitators invite participants to a rapid brainstorming session, encouraging them to contribute their individual understandings of the issue at stake. Time constraints induce participants to be spontaneous and to avoid over-rationalizing their responses. An equitable space is afforded for participants to contribute their ideas without being dominated or “silenced” by the most vocal or eloquent participants. The brainstorming session is used as a framing mechanism to invite participants to open up a broad spectrum of ideas (Kelley and Kelley Citation2013), record their thoughts as they emerge, and create a visual memory of everyone’s contributions. With this activity, participants spontaneously engage in a collective issue definition (see ) that allows a smooth transition to the in-depth conversation on the topic. The wide diversity of input creates a canvas for the personal stories that participants are invited to share later.

Principle 4: Empower through Stories

Bruner (Citation2003) argues that stories are the building blocks of human experience. At its core, our brain is a story processor (Haidt Citation2012) that uses narratives to capture our diverse perspectives (Storr Citation2020). Stories constitute our own narrative versions of reality “whose acceptability is governed by convention and ‘narrative necessity’ rather than by empirical verification and logical requirements” (Bruner Citation1991: 4-5).

Sharing stories and lived experiences as part of a dialogic process helps us make sense of the world and can draw us closer together by encouraging empathy across shared types of experiences. In the GDF, storytelling happens after the brainstorming session and the conversation around it, and helps to give personal meaning to the compiled inputs from the previous activity. It allows participants to focus on their feelings and meanings while presenting their personal narratives. In this way, they close the loop of sharing their experiences by highlighting what is meaningful for them in their stories.

Principle 5: Engage Minds, Hearts, and Hands

Participatory and experiential activities form an intrinsic part of the framework. We frame these activities as “generative” as they elicit memories, evoke emotions and feelings, and express relationships between ideas (Sanders Citation2000). The activities are designed to stimulate and enhance the dialogic process. The collective participation in the activities creates a shared, safe, and trusted space, and helps participants become more aware of their own thoughts and perspectives, encouraging them to be more authentic as conversational partners.

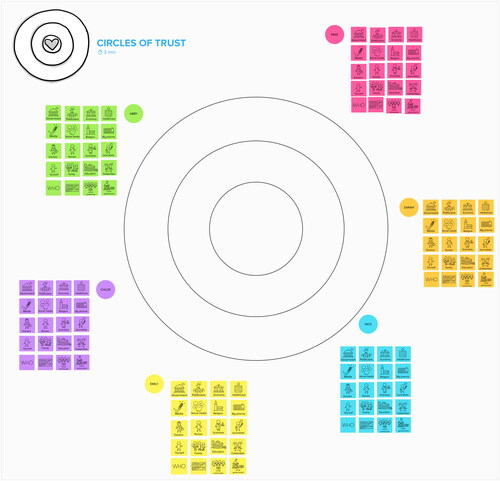

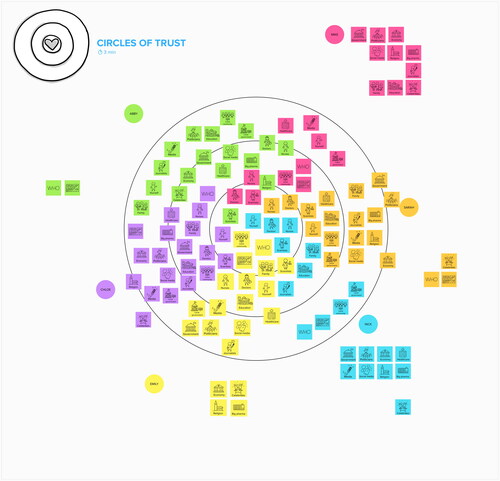

Generative activities have mainly visual components (see ). Visual prompts and semantic cues are employed to access and express the emotional aspect of participants’ experiences, acknowledging the subjective perspective of sensing, knowing, remembering, and expressing (Mitchell Citation2011; Guillemin & Drew Citation2010). In conjunction with the dialogic process, the ultimate goal of the activities is to produce a holistic experience of dialogue through shared meanings and a sense of accomplishment.

Figure 3. (a) Example of a generative activity on visualizing micro-maps of trust (before). (b) Example of a generative activity on visualizing micro-maps of trust (after).

Study Description and Research Methods

This study sought to evaluate how the GDF could be developed and implemented to advance the study and practice of engaged journalism, specifically by enhancing opportunities for deep listening by journalists. This process included testing the strengths and weaknesses of the framework for acquiring information from non-expert sources; stimulating participation by, and developing personal connections among, audiences/participants; and providing journalists with the skills and tools to facilitate forms of listening. In particular, we aspire to present the GDF as an example of designing scaffoldings for journalists who wish to engage in more organic, empathic, and dialogic conversations with their communities. We frame these conversations as “constructive” because they are grounded in listening and are nuanced, reflective, and connective (Roy Citation2021). We specifically aim at introducing the GDF as a pedagogical intervention in journalism that exposes students to new tools and skills for listening to the communities they work with and learning how to engage with greater empathy and compassion.

Acquiring and mastering those skills, sufficient to successfully employ them in everyday journalistic practice, requires embracing curiosity, learning by doing, and engaging with playful imagination. This creative and rigorous exploration can primarily flourish in academic settings that allow such learning journeys so that future journalists can experiment with better ways of engaging with their audiences through such principles and modalities. We argue that the academic environment affords the kind of time, flexibility, and structured supervision that is a more appropriate setting for testing experimental approaches such as the one we suggest in this article. With that in mind, we decided to pilot this intervention in the context of journalism education. Our hypothesis is that exposing and immersing journalism sstudents to such practices and tools early on can expand their skillset as future journalists and build on their exploratory mindset.

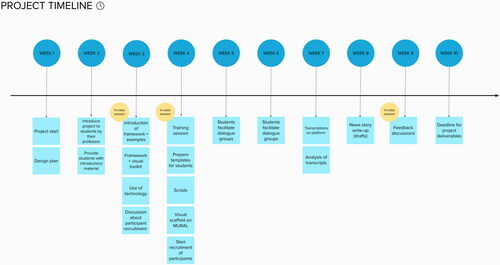

For these reasons, we worked closely throughout an entire academic term with a group of journalism students and their professor to explore the framework’s potential through a wide range of activities ().Footnote2 Our goal was to support them in developing the skills to (1) surface the GDF participants’ diverse and rich lived experiences through the application of principles of design and facilitation, (2) connect with their audiences with greater empathy and compassion, and (3) engage in more active and reflective listening skills to determine the leads for their news stories instead of predetermining what the story should be prior to the interview. Specifically, in spring 2021, the authors contacted an instructor who teaches a course on engaged journalism at the University of Oregon, and the instructor, in turn, invited their group of 17 students in the course to participate in an experimental and experiential process of learning and testing the framework. Neither the instructor nor the students were compensated, and their participation was voluntary.Footnote3

In particular, the students—all of them upper-division undergraduate majors in journalism—had the opportunity to join two training sessions with the first author to be introduced to the GDF and get basic training in facilitation skills. After the two trainings, the first author developed a series of resources for the students which they were invited to study asynchronously to prepare for facilitating a conversation with a group of participants. The resources ranged from readings on facilitation to step-by-step guides on how to use the GDF script and the online collaboration space Mural.

To further immerse the students into the framework, the first author invited the students to join two facilitated conversations as participants following the GDF so that they could experience the power of dialogue and familiarize themselves with the design of the conversation scaffolding before embarking on hosting a series of facilitated conversations themselves. After that firsthand experience, the students worked in pairsFootnote4 to practice and implement the design and facilitation of a deep-listening dialogue session each with a small group of 4–6 participants (drawn from a diverse pool of United States adults).Footnote5

Additionally, the students implemented the generative dialogue’s deep-listening framework as part of producing a news story, the final deliverable for their course. The recordings of the facilitated conversations were uploaded on the Local Voices Network, a platform of connected conversations that is developed by Cortico, a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization that collaborates closely with the Center for Constructive Communication at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology . This technology-supported system combines facilitated conversation and spoken language technologies to bring underheard community voices, perspectives, and stories into the center of a healthier public dialogue. The platform supports annotation, analysis, and visualization tools that help make sense of patterns within and across recorded conversations. The first author granted all students access to the platform where they had access to the full verbatim and time-stamped transcripts of the conversations they facilitated. The students had full access to all features of the platform, which allowed them to highlight, tag, and annotate specific quotes in the conversations they wanted to emphasize as well as share or download links to audio snippets of selected participant quotes to embed in their news stories.

For this study, we applied the GDF to tune into people’s voices and lived experiences as a means of understanding hopes and concerns around the COVID-19 vaccination while identifying trust deficits and information voids (for a detailed description of the process and the accompanying toolkit, see Dimitrakopoulou Citation2021). One aim of this research was to evaluate the experience that the journalism students had while working with and implementing the GDF. Although the term long collaboration with the students and the instructor of the course yielded diverse and rich data on multiple levels, for the purpose of this article we will focus on the structured feedback sessions that we hosted with the students. The sessions included 60 min of discussion with the whole group and three small-group discussions of 45 min, each via the videoconferencing platform Zoom and using Mural to facilitate the feedback.Footnote6 All sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Additionally, each student team produced a reflection document outlining their experience with the framework.

The resulting data were coded in three rounds. During the first round, the textual inputs on the online collaboration platform Mural recorded during the facilitation of the feedback sessions were individually coded to identify emerging patterns. This list was then used to identify central themes in the transcripts that were analyzed in the second stage. Finally, these clustered codes were again read against the entire data set of materials to confirm the main themes. In the results section, the student quotes have been anonymized.

Results: Student Reactions and Reflections Regarding the Framework

To better understand the value of the GDF to journalists as a method for listening and engagement, we focused our analysis on three main areas: sourcing information, developing and fostering connections with their audiences, and developing skills and tools to facilitate forms of listening.Footnote7

Inviting a Variety of Voices to Diversify Data and Information-Gathering Techniques

The student journalists agreed that the GDF helped them hear a diversity of voices and create an equitable space where people were invited to contribute their thoughts and opinions on the issue in a structured and focused way. The process provided the students with “very rich content,” especially for topics that are controversial, such as the COVID-19 vaccine, because “it allows people to express not only their thoughts and beliefs, but also where they came from” (Team 7, reflections document), altogether accommodating “more comprehensive conversations on a given topic” (Team 6, reflections document).

Not being a typical interview, the GDF invites a diversity of experiences to be shared. In particular, the interactions between the participants and between the journalists and the participants foster the interlacement of personal stories. It eases the tensions and potential disagreements because it invites participants to connect through stories rather than facts or opinions. According to one student, “It allowed [participants] to discuss these hot-button issues in a way that wasn’t combative or confronting […] I just don’t think we would have gotten that kind of response with just one-on-one interviews” (Student 14, Team 7). Along those lines, a student from the same team confirmed that they were able to “get almost a more authentic reaction from people, instead of just their knee-jerk response to a question” (Student 13, Team 7).

The framework supports the development of a participant-led story that relays to both participants and journalists the agency to shape and craft stories that put the audience into the spotlight, rather than the particular agenda of journalists. The way the process is designed supports an inclusive and equitable space in which participants feel seen and heard when their lived experiences are validated as part of a reflective learning dialogue. As one student stated, “With this process, I feel like we talk to people first and then […] write a story from that” (Student 11, Team 6). The process allowed the participants to lead the storyline rather than the journalists coming to the conversation with specific questions in mind. Making space for participants to say what they wanted allowed them to feel heard, and to open up and express their feelings without feeling invalidated: “As the reporter, whether or not you agree, this is the best way to get the most honest, reliable information […] It’s incredible how much you can learn about people and about the world when you let them speak their mind” (Team 1, reflections document).

While for most of the students the structure was supportive and helpful, some students felt that the structure was inhibiting, and that it may have kept them from developing a more one-on-one personal connection with a single interviewee. This gap is illustrated by a student who said, “I felt like it was a great leaping-off point for a story but not necessarily structured in a way where I could dig deep into one specific person” (Student 8, Team 4). In some cases, students struggled with what they described as a tension between hearing more voices and perspectives on the topic but not having the time to dig deeper into individual personal experiences. As one put it, “It wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, I just noticed that we couldn’t operate in the way that we normally do” (Student 16, Team 8).

However, what some students felt was lacking in depth was made up for in breadth (Team 8, reflections document). Hearing many perspectives at once made it easier to notice trends and patterns in conversation, which is often a challenging task in the later stages in routine reporting when trying to bring together many separate interviews. The group setting component of the framework allowed the students to see how people interact and how those interactions build on each other. The framework was perceived as a way for journalists to gain “a deeper understanding of issues that have two diametrically opposed sides” (Team 7, reflections document).

Making Space for Empathy and Compassion

Reflecting on the experience of facilitating the dialogue and after getting training in the facilitation and listening skills introduced by the framework, the students reported having learned a lot, especially in relation to connecting with their interviewees in a more profound, empathetic, and compassionate way. The acquired skills were said to help the students authentically connect with the participants and support them in feeling seen and heard. In the words of one student, “I felt like I had a lot of empathy and compassion when they shared their stories compared to the beginning. [At first] I just was like, ‘Oh, these are just participants’. But then, as it went on, I felt like I got to know them as people more” (Student 5, Team 3).

The design and format of the process created a safe and inviting space for participants to open up and feel understood. It was characterized as “not a typical news story,” but rather a process that “really opened up the floor for all the participants to really speak their mind without feeling invalidated […] When we wrote the story, I felt like we were really allowing the story to sound like it was a subject story” (Student 1, Team 1).

As for the use of creativity as the entry point to difficult conversations, students shared that the introductory generative activity of drawing helped participants open up and took the edge off the discussion of a potentially disputatious and challenging topic. Student eight from Team four thought that the drawing activity at the beginning of the dialogue was “very smart” because it helped everyone open up about their personal experience rather quickly and focus on the emotional dimension of the experience. As a result, participants were able to move quickly into engaging conversations. Another student mentioned that starting with the creative space helped create a safe environment: “I could tell one or two of my participants came in defensive, and they were ready to defend their viewpoints. And starting with this a little bit creative, allowed for connection, softened their exterior a little bit and allowed them to listen better” (Student 14, Team 7).

The shared reflection space enabled both facilitators and participants to stay engaged in and focused on the conversation and see how their responses and experiences were compared to each other. Especially in a virtual setting, where there are no tangible artifacts to engage with, “it served as a shared space that helped participants navigate the dialogue collaboratively” (Student 16, Team 8). The students offered reflections and insights regarding the ability to engage with the participants in an empathetic and compassionate way, although the dialogues were performed in a virtual setting. These contributions suggest an encouraging shift to viewing technology not as a barrier to meaningful interactions but rather as a space that can contain and support constructive conversations if designed intentionally and purposefully.

Listening to Learn, Learning to Listen

The process and the experience proved to be empowering for the students’ self-awareness with regard to their own personality traits and interviewing skills. As one noted: “I find myself to be fairly introverted so […] it surprised me [how] much I was able to kind of break out of that shell and actually got to talk to these people and know them better. And understand them” (Student 4, Team 2).

Being exposed to people with different experiences appeared to be revealing to students as they were able to see outside of their own social circle and gain awareness of their own bounded point of view. As one student observed, “I think I kind of learned my own limited perspective […] Just hearing other people’s perspectives was really just good for me in general, but also for the news story” (Student 3, Team 2). The process also helped students engage with the participants with more nuance and intentionality, particularly when compared to interacting with people in a conventional reporting fashion. Students described being able to “actually talk to someone, even though I still disagreed with the participants we had, I was at least able to understand them and empathize” (Student 15, Team 8).

Students highlighted in diverse ways the value of allowing themselves to listen deeply and tune in with attention to the participants’ stories and experiences. Rather than a results-oriented interview, the framework afforded what they felt was a more empathetic and authentic connection with the participants. As one student put it, “[the framework] really wanted us to think about connection and deep listening, rather than just throwing together questions just to crank out a story” (Student 10, Team 5). An insightful comment added by the same student noted that interviewing assignments in reporting courses typically focus on the story rather than on the process or how to interview their source. She said: “Let’s put a lot of attention and care into the process, which in turn, probably just elicits better responses and the participants understand that this is a well-thought-out space” (Student 10, Team 5).

According to Weiser (Citation1994 7), “A good tool is an invisible tool” (our emphasis). For a deep-listening process to spark and thrive, tools need to be nonintrusive and mindfully embedded in the process. When facilitation is working effectively, the conversation transforms into dialogic relational interaction. A meeting full of strangers becomes a more open, connected, and accommodating space for people to share their authentic selves. This process is illustrated in this student’s words: “One person shared something a little more vulnerable once we got to the personal stories, and then we noticed that as we went around, people were like, ‘Oh, OK. It’s OK to talk about it here.’ It was just organically setting the stage” (Student 16, Team 8). The format of the interaction allowed for a high level of vulnerability: “As journalists, we often feel that we have to ask the hard-hitting questions and stay impartial, but this time, we engaged in organic conversations with our subjects in a relaxed environment” (Team 8, reflections document). The value of deep listening as a way to meaningfully engage with communities instead of speaking for them was “allowing journalists to write stories based on a community’s needs instead of assuming this information” (Team 5, reflections document).

The reflection process with the journalism students revealed a series of pedagogically related tensions that resulted from introducing and implementing the GDF. The framework challenged some of the students’ previous journalistic training, especially the idea that the journalist starts with a specific goal or objective in mind and then finds the sources which will support the writing of that particular story. As a student observed, “We were inversing the regular writing process, because usually […] my editor always asks me, ‘What’s the point of this? What are you trying to say?’ And then I go out and try to find people who back up what I’m trying to say, which I’m not saying [is] a better process. Still, in this [GDF] process, I feel like we talk to people first and then we try to figure out what all of them are saying together, and then write a story from that” (Student 11, Team 6). The participant-led approach and the somewhat agnostic stance the journalists are invited to take may be more empowering for the participants. It may also introduce a new challenge to the journalist when deciding the focus of the story: “We’re taught, ‘What’s your nut graf? What’s the meat of the story?’ And I didn’t know how to frame that in a specific way without just being like, ‘This happened. Then this, then this…’” (Student 5, Team 3). Finding the right balance to include all of the participants’ voices poses an additional challenge. While it adds a layer of complexity to the write-up of the story, one could argue that it demands the journalist’s careful deliberation in the selection of quotes and inputs so that all of the participants’ voices are heard in the story.

Discussion and Conclusion: Employing Design to Generate Listening Modalities

In this work, we employed design as a generative method concerned with what might be instead of making statements about what is (Gaver Citation2012). We introduced the concept of the dialogic interview in a group setting and an actionable toolkit called the Generative Dialogue Framework. The GDF aims to support dialogue to evolve organically, facilitate group learning and connection, and create a visual memory of the process. Drawing on design thinking and facilitation, we designed, prototyped, and tested an innovative approach to reimagining the diverse ways in which journalism students can learn and practice how to hone their listening skills to invite their prospective audiences to a reflective learning dialogue. Our objective for this work is threefold: First, we want to introduce an example of an actionable framework and toolkit to reimagine how we might facilitate deep listening in journalism to advance the theory and the methods of engaged journalism. Second, we aim at introducing actionable and applied processes for engaged journalism curricula. In particular, we want to demonstrate how design (and design thinking) can inspire pedagogical interventions—ones that support journalism educators and students in employing creativity as a modality to reimagine non-extractive interview approaches, ultimately bringing journalists and audiences together to discover, understand, and co-create stories that matter to the communities from which they emerge. Essentially, we argue that the intersection of design thinking, facilitation, and community-centered listening may create space for experimentation and innovation that could breathe new life and variation into the way journalism is taught. Finally, we want to open an academic discussion about what a future of conversation-oriented journalism might look like. For example, how journalism might tap into new skill sets of facilitation as well as work with community partners who are experts in this area to bring forward the questions and concerns of communities more effectively?

The GDF offers a structured setup to bring dialogue studies and design thinking into the context of journalism research, pedagogy, and practice. Through interacting and engaging with the framework, journalists can experiment with improving their listening skills and probe how they can engage with their audiences in a more empathetic and compassionate way. It provides a structured yet flexible process that can be iterated to accommodate interviewing and information-gathering purposes for a deeper exploration of social issues that journalists may choose to cover. Rather than seeking sources for relatively preplanned story frames, the framework invites a more agnostic stance into an issue by affording the space to facilitate reflective learning dialogues. Such spaces allow journalists to empower new voices to join the public sphere, share and reflect on their lived experiences, and identify common ground. The design of such spaces and processes can provide tools for community-centered and community-powered journalism, particularly organized around deep listening and non-extractive information gathering on the part of journalists.

Our research suggests that the study and practice of engaged journalism could benefit from a theoretical and methodological dialogue with concepts and principles at the intersection of design, facilitation, and technology, especially if this process starts early on during their studies to afford a culture of learning and exploration. Design thinking can offer a creative lens into a bottom-up, human-centered approach, one that could equip emerging journalists with a unique set of tools, methods, and mindsets to think outside the box of journalistic norms and routines. It can offer a helpful framework for them as they seek to develop innovative processes, exercise their creativity, and explore how journalistic performance could be reimagined (cf. Doherty Citation2018). As “a social technology at work” (Liedtka Citation2020, our emphasis), design thinking can provide an actionable mix of tools and insights to facilitate social interactions in the field of engaged journalism.

The framework we have introduced, combined with the design principles and the accompanying online toolkit, constitutes an actionable and tangible method that can be employed and further tested as a pedagogical intervention in journalism curricula to support future journalists in engaging in deep listening and creative approaches with their audiences—the kind of mutually beneficial interactions imagined for journalism built on reciprocity (Lewis, Holton, and Coddington Citation2014). The approach provides a process that is easy to follow, thus simplifying the work of group conversation facilitation by translating it into concrete steps without requiring extensive training in facilitation skills and techniques. The conversations facilitated by the journalism students in our study were conducted with minimal training, and yet they yielded impressive results in terms of attaining a deep feeling of connection and mutual understanding with the people interviewed. However, even while processes and tools like the GDF can offer rapid on-ramps for journalists interested in implementing the dialogue approach, we argue that such facilitation skills used more broadly could be a much-needed type of expertise for future journalists. This could be particularly the case for reporters and editors who are called upon to engage their communities on complex topics amid an increasingly polarized social and political climate. Ideally, such tools, principles, and skills for listening to and co-creating with communities would be instilled in journalism training, particularly in the testing grounds that are journalism undergraduate programs. In this way, the Generative Dialogue Framework we have described has value not only as a pedagogical intervention but also as a professional one by equipping the next generation of journalists with new approaches to reporting, interviewing, and storytelling.

Naturally, there are challenges and limitations posed by the GDF and broader efforts to develop engaged journalism in a dialogic way. First, the process of setting up the conversations, recruiting participants, and analyzing the resulting data can be time intensive, even with ready-made tools available. The students participating in this study had several weeks to learn the process, execute it, and write up their stories. Even while skilling up more quickly than students, professional journalists are unlikely to have such time and attention available, particularly in an environment where they are often expected to do more with less. And, by its very nature, the experience of conducting these small-group conversations does not easily “scale” (nor perhaps should it).

This challenge might suggest that attempting the GDF in a conventional news setting would be unrealistic. However, news organizations taking a more engaged approach to reporting are already having small-group conversations with community members and attempting to improve their reporting as a result (e.g., see Belair-Gagnon, Nelson, and Lewis Citation2019). Therefore, there is reason to believe that design thinking generally and actionable frameworks such as the GDF particularly could offer a more productive means of having those conversations—and, what’s more, could extend the scope and reach of those conversations by holding them online as opposed to in-person only. Ultimately, we acknowledge that our results need to be tempered by the reality that the GDF was tested on a small convenience sample of journalism students, including ones who had already indicated an interest in engaged journalism by virtue of signing up for the course.

We further acknowledge that the results of this study are limited to a subsection of undergraduate journalism students in a U.S. academic institution. Additional research is needed to unpack the opportunities and potential of the GDF more fully, both for education as well as, eventually, for journalism broadly. Further consideration of different geopolitics and media ecologies could also be taken into account. Additionally, the full potential of the GDF as a tool for advancing engaged journalism practice in the industry beyond the academic setting should be analyzed in future studies based on a more real-world kind of professional environment. Nevertheless, we suggest that approaches such as the GDF, while exploratory in nature, can offer exciting pathways to reimagine how the future of engaged journalism might bring into play facilitation, technology, and design, thus expanding the applications of deep-listening modalities.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the students in the School of Journalism and Communication at the University of Oregon who took part in the study. The authors wish to thank Andrew DeVigal, the endowed chair in journalism innovation and civic engagement and the director of the Agora Journalism Center at the University of Oregon, who supported the authors in conducting the study. Dimitra Dimitrakopoulou would like to thank Cortico for granting access to the Local Voices Network platform, where the conversations from the facilitated conversations were hosted and transcribed. The visual language developed for this project was designed by Bigger Picture.dk.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The framework, toolkit and visuals are available upon request from the first author, to be used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2 The study received an IRB Exempt Evaluation under the MIT COUHES Approval Code (E-2620).

3 While the second author works at the same university as the instructor involved and oversees the journalism program there, the instructor themself reports directly to another supervisory administrator. Additionally, the instructor was under no obligation to test the framework in the course but chose to do so on their own because of its practical potential for gathering information and because of its pedagogical potential for engaged journalism. Furthermore, the second author had not, to his knowledge, previously taught the students involved, and the first author—who was the lead researcher on this study overall and primary point of connection for study participants—had no prior connection either with the instructor or the students.

4 A total of 17 students participated in the final project, resulting in eight facilitated conversations (one group consisted of three students).

5 Participants were recruited through the MIT Behavioral Research Lab by inviting them to sign up to predetermined time slots for the live dialogue sessions. Confirmed participants were then invited to join a remote session held on the videoconferencing platform Zoom and the shared collaboration space Mural. In total, 43 participants between 18 and 65 years old across the USA joined eight dialogue groups. The sessions were facilitated by the journalism students in May 2021 and lasted 75–90 minutes each depending on the size of each group. Participants received a remuneration for the time they spent in the study per the research lab’s compensation policies.

6 The instructor of the course, while not a researcher on this study, is an expert in group facilitation exercises and therefore helped the authors by leading one of the small-group breakouts held via Zoom.

7 Because our primary research interest was to explore and evaluate the value of GDF to journalistic work, we decided to exclude from our analysis the data compiled by the journalism students during their sessions regarding people’s perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccination.

References

- Barge, Kevin J. 2002. “Enlarging the Meaning of Group Deliberation: From Discussion to Dialogue.” In New Directions in Group Communication, edited by Lawrence R. Frey, 159–178. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Belair-Gagnon, Valerie, Jacob L. Nelson, and Seth C. Lewis. 2019. “Audience Engagement, Reciprocity, and the Pursuit of Community Connectedness in Public Media Journalism.” Journalism Practice 13 (5): 558–575.

- Black, Laura W. 2008. “Deliberation, Storytelling, and Dialogic Moments.” Communication Theory 18 (1): 93–116.

- Bohm, David. 1996. On Dialogue. New York: Routledge.

- Brand, Williemien. 2017. Visual Thinking: Empowering People and Organisations through Visual Collaboration. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers.

- Brown, Tim. 2020. “Design Thinking.” In Harvard Business Review, edited by Tim Brown, Clayton M. Christensen, Indra Nooyi, Vijay Govindarajan. On Design Thinking, 1–22. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Bruner, Jerome. 1991. “The Narrative Construction of Reality.” Critical Inquiry 18 (1): 1–21.

- Bruner, Jerome. 2003. Making Stories: Law, Literature, Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bruns, Axel. 2005. Gatewatching: Collaborative Online News Production. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Buber, Martin. 1970. I and Thou. New York: Scribner.

- Buber, Martin. 1998. The Knowledge of Man: Selected Essays. New York: Humanity Books.

- Buchanan, Richard. 1992. “Wicked Problems in Design Thinking.” Design Issues 8 (2): 5–21.

- Coddington, Mark, Seth C. Lewis, and Valerie Belair-Gagnon. 2021. “The Imagined Audience for News: Where Does a Journalist’s Perception of the Audience Come from?” Journalism Studies 22 (8): 1028–1046.

- Costera Meijer, Irene. 2020. “Understanding the Audience Turn in Journalism: From Quality Discourse to Innovation Discourse as Anchoring Practices 1995–2020.” Journalism Studies 21 (16): 2326–2342.

- DeJarnette, Ben. 2016. “Before Interviewing, Journalists Must Listen Deeply.” MediaShift. http://mediashift.org/2016/01/before-interviewing-journalists-must-listen-deeply

- Dimitrakopoulou, Dimitra. 2021. “Designing Generative Dialogue Spaces to Enhance Focus Group Research: A Case Study in the Context of COVID-19 Vaccination.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods. DOI:10.1177/16094069211066704.

- Doherty, Skye. 2018. Journalism Design Interactive Technologies and the Future of Storytelling. New York: Routledge.

- Ferrucci, Patrick, Jacob L. Nelson, and Miles P. Davis. 2020. “From ‘Public Journalism’ to ‘Engaged Journalism’: Imagined Audiences and Denigrating Discourse.” International Journal of Communication 14: 1586–1604.

- Gaver, William. 2012. “What Should We Expect from Research through Design?” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, Texas, May 2012, 937–946.

- Green-Barber, Lindsay, and Eric Garcia McKinley. 2019. “Engaged Journalism: Practices for Building Trust, Generating Revenue, and Fostering Civic Engagement.” Impact Architects/News Integrity Initiative: 1–62. https://bit.ly/3xGmbQD

- Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame Analysis. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

- Grant, Adam. 2021. Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

- Guillemin, Marilys, and Sarah Drew. 2010. “Questions of Process in Participant-Generated Visual Methodologies.” Visual Studies 25 (2): 175–188.

- Gunnlaugson, Olen. 2014. “Bohmian Dialogue: A Critical Retrospective of Bohm’s Approach to Dialogue as a Practice of Collective Communication.” Journal of Dialogue Studies 2 (1): 25–34.

- Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Isaacs, William. 1999. Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together: A Pioneering Approach to Communicating in Business and in Life. New York: Currency.

- Jarvis, Jeff. 2006. “Networked Journalism.” Buzzmachine, November 30. www.buzzmachine.com/2006/07/05/networked-journalism

- Kelley, Tom, and David Kelley. 2013. Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential within Us All. New York: Random House.

- Kubin, Emily, Curtis Puryearb, Chelsea Schein, and Kurt Gray. 2021. “Personal Experiences Bridge Moral and Political Divides Better than Facts.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118 (6): e2008389118.

- Lawrence, Regine G., Damian Radcliffe, and Thomas R. Schmidt. 2018. “Practicing Engagement: Participatory Journalism in the Web 2.0 Era.” Journalism Practice 12 (10): 1220–1240.

- Lawrence, Regina G., Eric Gordon, Andrew DeVigal, Caroline Mellor, and Jonathan Elbaz. 2019. “Building Engagement: Supporting the Practice of Relational Journalism.” Agora Journalism Center at the University of Oregon. http://bit.ly/building-engagement

- Lewis, Seth C., Avery E. Holton, and Mark. Coddington. 2014. “Reciprocal Journalism: A Concept of Mutual Exchange between Journalists and Audiences.” Journalism Practice 8 (2): 229–241.

- Lewrick, Michael, Patrick Link, and Larry J. Leifer. 2020. The Design Thinking Toolbox: A Guide to Mastering the Most Popular and Valuable Innovation Methods. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Liedtka, Jeanne. 2020. “Putting Technology in Its Place: Design Thinking’s Social Technology at Work.” California Management Review 62 (2): 53–83.

- Meadows, Donella H. 2008. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Mitchell, Claudia. 2011. Doing Visual Research. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Nelson, Jacob L. 2018. “The Elusive Engagement Metric.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 528–544.

- Nelson, Jacob L. 2021. Imagined Audiences: How Journalists Perceive and Pursue the Public. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Qvist-Sørensen, Ole, and Loa Baarstrup. 2019. Visual Collaboration: A Powerful Toolkit for Improving Meetings, Projects, and Processes. Hoboken, NJ: Willey.

- Ripley, Amanda. 2019. “Complicating the Narratives.” The Medium. https://thewholestory.solutionsjournalism.org/complicating-the-narratives-b91ea06ddf63

- Robinson, Sue, Kelly Jensen, and Carlos Dávalos. 2021. “Listening Literacies’ as Keys to Rebuilding Trust in Journalism: A Typology for a Changing News Audience.” Journalism Studies 22 (9): 1219–1237.

- Roy, D. K. 2021. “Trust, Society, and Democracy.” Talk delivered at the Chautauqua Institution, Chautauqua, July 15.

- Sanders, E. B.-N. 2000. “Generative Tools for CoDesigning.” In Collaborative Design, edited by Stephen A. R. Scrivener, Linden J. Ball, and Andrée Woodcock, 3–12. London: Springer-Verlag.

- Scharmer, Otto C. 2009. Theory U: Leading from the Future as It Emerges: The Social Technology of Presencing. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Schmidt, Thomas R., and Regina G. Lawrence. 2020. “Engaged Journalism and News Work: A Sociotechnical Analysis of Organizational Dynamics and Professional Challenges.” Journalism Practice 14 (5): 518–536.

- Schmidt, Thomas R., Jacob L. Nelson, and Regina G. Lawrence. 2022. “Conceptualizing the Active Audience: Rhetoric and Practice in ‘Engaged Journalism.” Journalism 23 (1): 3–21.

- Senge, Peter. 1990. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday/Currency.

- Sicart, Miguel. 2017. Play Matters. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Singer, Jane B., Alfred. Hermida, David. Domingo, Ari. Heinonen, Steve. Paulussen, Thorsten. Quandt, Zvi. Reich, and Marina. Vujnovic. 2011. Participatory Journalism: Guarding Open Gates at Online Newspapers. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Stains, Robert, Jr. 2014. “Repairing the Breach: The Power of Dialogue to Heal Relationships and Communities.” Journal of Public Deliberation 10 (1), Art. 7.

- Storr, Will. 2020. Science of Storytelling: Why Stories Make Us Human and How to Tell Them Better. London: William Collins.

- Ulibarri, Nicola, Amanda E. Cravens, Anja Svetina Nabergoj, Sebastian Kernbach, and Adam Royalty. 2020. Creativity in Research: Cultivate Clarity, Be Innovative, and Make Progress in Your Research Journey. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, Karin. 2020. “An Emotional Turn in Journalism Studies?” Digital Journalism 8 (2): 175–194.

- Weiser, Marc. 1994. “The World Is Not a Desktop.” Interactions 1 (1): 7–8.

- Wenzel, Andrea. 2019. “Public Media and Marginalized Publics: Online and Offline Engagement Strategies and Local Storytelling Networks.” Digital Journalism 7 (1): 146–163.

- Wenzel, Andrea. 2020. Community-Centered Journalism: Engaging People, Exploring Solutions, and Building Trust. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Xia, Yiping, Sue Robinson, Megan Zahay, and Deen Freelon. 2020. “The Evolving Journalistic Roles on Social Media: Exploring “Engagement” as Relationship-Building between Journalists and Citizens.” Journalism Practice 14 (5): 556–573.

- Zamith, Rodrigo. 2018. “Quantified Audiences in News Production.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 418–435.