Abstract

Sharing and discussing visual images in WhatsApp groups functions as a form of phatic news sharing to achieve a sense of togetherness and sociability. We explore how visual media content shared in personal WhatsApp interactions during the first strict lockdown months of the COVID-19 pandemic functions as phatic news. Our study addresses a gap in journalism studies in researching news-related and visual content from user perspectives. Our article provides insights into how the “semi-private” space of WhatsApp offers people a digital communication space to deal with becoming a news subject during the crisis: people appropriate news by shaping it into different visual forms which can be attractively shared on WhatsApp. We focus on working adults (aged 25–49) in urban areas in Spain, Italy, and the Netherlands. Visual phatic news sharing on WhatsApp combines public and private aspects, especially how people address issues of public concern through their private WhatsApp communication. Our conclusions reveal how WhatsApp functions as a sense-making practice and vehicle for ontological security in dealing with the fearful and unsettling crisis situation. The visual images shared are a hybrid form of communication, blurring boundaries between private life and public concerns presented on the news.

Introduction

At “perhaps the heaviest moment” of the COVID-19 crisis, with citizens’ confidence in Dutch government policy at an all-time low (NRC Handelsblad, 18 December 2021), a deepfake video of the Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte singing a Christmas carol goes viral: it is shared heavily in all kinds of groups on WhatsApp (; RTL News, 17 December 2021). For Dutch audiences the video is clearly news-related: the “line-up” of Rutte together with Jaap van Dissel, Diederik Gommers, and Hugo de Jonge—all key players in the COVID-19 crisis in the Netherlands—is all too familiar after months of news content about the pandemic. The video brings comic relief in hard times, but, as argued by Bart Jacobs (Professor of Computer Security at Radboud University Nijmegen), it also serves as a “warning” in showing how easy it is to manipulate images (RTL News, 17 December 2021). This example highlights three key characteristics of developments in sharing news-related content on WhatsApp: first, that such news sharing is a form of phatic communication (Miller Citation2008); second, that it blurs the boundaries between previously distinct genres and what constitutes “news” (for debates around “newsness” see Edgerly and Vraga Citation2020); and third, that such news sharing is increasingly visual (see e.g., Murru and Vicari Citation2021).

How does the fact that such news sharing happens in the “semi-private” space of WhatsApp change the perception of what news is, how it can be shared, and how it connects to everyday life? This article is concerned with how news is appropriated in (audio)visual content from screenshots and visual memes to viral videos, with added characteristics that may indicate satire and parody (Druick Citation2009), but also critical commentary—about the spread of disinformation for instance. It demonstrates the hybridity of visual phatic news sharing on WhatsApp: it both includes and ventures beyond news media content with underlying journalistic norms and modes of communication (Ekström Citation2000). This article will specifically examine visual media content shared in personal WhatsApp interactions during the first strict lockdown months of the COVID-19 pandemic, reflecting on visual images as a hybrid form of communication that blurs the boundaries between private life and public concerns presented on the news.

Figure 1. Viral video from the Netherlands, circulated heavily in WhatsApp groups (source video: Fake it or leave it YouTube channel, 16 December 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UEWnqDZ799U).

WhatsApp and Visual Phatic News Sharing

Literature Review

Recent studies (e.g., Swart, Peters, and Broersma Citation2018) have analysed the increasing shift of citizens in using digital platforms for private communication to discuss, interpret, and appropriate news, as part of media audiences’ “…continuing shift to more private networks” (Newman, et al. Citation2021, 23). As a digital space for communication across different scales of sociality (Miller, et al. Citation2016)—from one-to-one to large group interactions—WhatsApp is to many people an indispensable meso news-space for sharing news and news-related content. A meso news-space is an online space between private and public realms, where people are involved in news-related processes, that afford and sustain ongoing social interactions (Kligler-Vilenchik and Tenenboim Citation2020). WhatsApp dynamics are contingent upon the platform itself, the topic/s discussed, the participants, and the rules/guidelines for participation (Kligler-Vilenchik and Tenenboim Citation2020, 14). Research by amongst others Masip et al. (Citation2021, 1062) has demonstrated that users’ engagement with news is less obvious and harder to grasp on WhatsApp compared to other social platforms, because of the private or closed nature of the platform.

Messaging apps, such as WhatsApp are an integral part of social dynamics and communication systems in the modern media landscape (Boczkowski, Matassi, and Mitchelstein Citation2018; Karapanos, Teixeira, and Gouveia Citation2016), etched in people’s daily routines (Shove, Pantzar, and Watson Citation2012).Footnote1 WhatsApp is a free to download messaging and video calling app owned by Meta, and its functionalities include text and voice messaging, video calling, setting up a profile picture, and the sharing of diverse media types, such as videos, images (photos, GIFs, visual memes, stickers…), links and documents but also user locations and status updates. WhatsApp thus is also a social media platform. In their study on daily communication and the social mediation of everyday life, scholars Matassi, Boczkowski, and Mitchelstein (Citation2019, 2183) have defined WhatsApp as a “taken-for-granted platform” where “sociability is mainly produced in groups with friends and enacted through an ‘always on’ availability”: the authors argue here that differences in how people integrate the WhatsApp platform in their daily life is consequential to the different life stages of its users.

Sharing and appropriating of visual content in WhatsApp groups is a form of phatic news sharing, where “communications (…) have purely social (networking) and not informational or dialogic intents” (Miller Citation2008, 387). Duffy and Ling (Citation2020, 72) have drawn on theorisations of symbolic and meaningful dimensions of news sharing to understand phatic news sharing as an act of care (i.e., to build social cohesion), alongside its more practical or informational use (a.o. Feil Citation1982). Phatic news sharing serves the purpose of sociability (a sense of togetherness, De Gournay and Smoreda Citation2017), rather than an informational function (O’Hara, et al. Citation2014; Goh et al. Citation2019; Swart, Peters, and Broersma Citation2019). What stands out is the increased use of visual images (Rose Citation2016) for phatic news sharing on WhatsApp, and the hybridity of shared news-related content.

In this article, we follow-up our previous research by studying visual images shared in WhatsApp groups as a form of phatic news sharing (Duffy and Ling Citation2020). This term visual phatic news sharing. Our study addresses a gap in journalism studies in researching news-related content and visual content like photographs, visual memes, and viral videos (for exceptions see Al-Rawi, Al-Musalli, and Rigor Citation2022; MacDonald Citation2021) from user perspectives. Our conclusions provide insights into how WhatsApp offers a space that bridges the public and the private. In this meso space, people dealt with suddenly becoming a news subject during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the first lockdown months, WhatsApp afforded interviewees an online space to negotiate events impacting their own lives—events that are continuously narrated on the news in a continuous stream of “breaking-news” style crisis information (Miller and Volkmer Citation2006). The sharing of visual news-related content on WhatsApp functions as a sense-making practice and vehicle for ontological security (Giddens Citation1991; Kinnvall and Mitzen Citation2020) in dealing with the fearful and unsettling crisis situation. The visual images shared are a hybrid form of communication blurring boundaries between private life and public concerns presented on the news.

There are, then, several reasons why we wish to investigate the sharing of visual news-related content on WhatsApp. First, phatic communication (Miller Citation2008) and playfulness (Mortensen and Neumayer Citation2021) play a key role in news sharing (Duffy and Ling Citation2020; Swart, Peters, and Broersma Citation2019). Second, the sharing and discussing of content about current affairs increasingly takes place in meso spaces, such as WhatsApp, where news-related images are shared together with photos, humour, and visual objects unrelated to news (Matassi, Boczkowski, and Mitchelstein Citation2019; Valeriani and Vaccari Citation2018, Boczkowski, Matassi, and Mitchelstein Citation2018; Karapanos, Teixeira, and Gouveia Citation2016). Third and finally, the sharing of news and news-related content more and more takes place through the use of visual media types (Al-Rawi, Al-Musalli, and Rigor Citation2022; MacDonald Citation2021).

Research Question

Our study proposes to add to the body of research on WhatsApp as a meso news-space (Tenenboim and Kligler-Vilenchik Citation2020). It specifically contributes to understanding how phatic news sharing and discussing news-related content on WhatsApp is becoming more about sharing visuals, as part of modern media audiences’ continuing shift towards private communication channels and social media platforms (Newman, et al. Citation2021). We do so by presenting the insights of a transnational user study focusing on working adults (aged 25–49) in urban areas in Spain, Italy, and the Netherlands. According to market research, by the start of the pandemic, Spain, Italy, and the Netherlands were amongst the countries at the top of the list of WhatsApp users in Europe (eMarketer Citation2020). As the crisis situation of the pandemic continued in 2020, WhatsApp also was the platform which number of users grew the most with an increase of 40% (Kantar Citation2020). The COVID-19 crisis is a particularly relevant context to study this, as the public threat of the pandemic forced people into “lockdown” in their private homes. We, therefore, pose the following research question: How does visual media content shared in personal WhatsApp interactions during the first strict lockdown months of the COVID-19 pandemic function as phatic news? Specifically, we reflect on visual images as a hybrid form of communication that blurs the boundaries between private life and public concerns presented on the news.

Theoretical Framework

This article is part of a larger research project by an international team studying the communication by WhatsApp users (specifically, working adults) across Europe to cope with social isolation during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our research has previously shown how WhatsApp has facilitated information sharing and discussion during the first strictest lockdown months but also turned information into an expression of care towards others—particularly through one-on-one chats and discussion in small groups—to strengthen personal relationships and compensate for the lack of interactions in physical contexts. We have built on the notion of “scalable sociality” (Miller, et al. Citation2016)—i.e., people can choose the scale of the sociality that they want for any particular genre of communication—to understand WhatsApp (use) as a configuration of digital places, with different degrees of privacy, that is inhabited by groups of diverse size, affording multiple modes or genres of communication. To capture the multiple forms of co-presence and mediated proximity at a distance to others enabled by WhatsApp during the first months of strict lockdown, we formulated the concept of “scalable co-presence” (Costa, Esteve del Valle, and Hagedoorn Citation2022)—i.e., the experience of proximity to others across different scales of sociality. Our previous research revealed that the crisis shock of the first weeks of strict lockdown and social isolation “shrunk” WhatsApp communications, with interviewees relying more on their family members and close friends. Humorous communication exchanges with acquaintances (“weak ties”) during the pandemic crisis also seemed to have aided our participants in coping with the stress of the pandemic and in relieving anxiety (Esteve del Valle, Costa, and Hagedoorn Citation2022; compare Zhang, et al. Citation2021).

Our transnational research study was carried out by an international team, conducting in-depth, semi-structured interviews with working adults (25–49 years of age) from the urban areas of Barcelona (Spain), Milan (Italy), and Groningen (the Netherlands). Two methods of qualitative data analysis were employed: thematic analysis of interview data, and visual thematic analysis of collected (audio)visual content. On a theoretical-methodological level, this research draws on and adds to the body of research in media and journalism studies, and builds on a qualitative research design. We collected visual materials from the interviewees to understand the significance of visual news-related content on WhatsApp during the first strictest months of the COVID-19 lockdown. Interviewees discussed media use before and during the pandemic, their engagement on WhatsApp with news and entertainment about the COVID-19 crisis during March-June 2020, and sharing visual content—videos, personal photographs, screenshots (e.g., of graphs in news articles), visual memes—on topics ranging from local and international politics to anti-COVID-measures demonstrations, conspiracy theories, and distance learning.

Our study expands the previous research of the project by combining the analysis of our interview data together with an analysis of visual news-related content; the latter has not been explored in our previous works. Collected visual content consists of diverse media types—e.g., videos, photos, GIFs, visual memes, stickers, cartoons, or screenshots—shared via the WhatsApp platform. As Elleström (Citation2019) argues, media types have different narrative capacities, ranging from material, spatiotemporal, sensorial, and/or semiotic media modalities. Visual images afford multimodal narration, i.e., the use of various elements within a media text to tell a (news-related) story, such as language, images, sound, and moving pictures. Such elements may also be consumed separately, as there is no direct need to consume them all at once (Elleström Citation2019; Kress Citation2010). Added characteristics may indicate satire, parody, and critical commentary, but also very personal experiences and feelings. The hybridity of visual news-related content on WhatsApp includes and goes beyond news media content—from formats like cable news or daily newspapers—with underlying journalistic norms and modes of communication, such as information, storytelling, and attractions (Ekström Citation2000).

Methodology

Participants in Countries under Strict Lockdown

This study was carried out by an international team, conducting 30 in-depth, semi-structured interviews of 50–90 min with working “middle-class” white adults (25–49 years of age) from the urban areas of three European cities—Barcelona (Spain), Milan (Italy) and Groningen (the Netherlands)—to understand their WhatsApp use and the meaning and significance of visual content in their personal WhatsApp interactions, during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic when the countries were under strict lockdown. We focused on adults from a self-identified white middle-class background to make our sample more homogeneous and because we wanted to investigate the use of digital technologies outside the context of transnational migration. The interviews were conducted by two of the authors and a trained media studies master’s student, and carried out between April and June of 2020. We invited interviewees to reflect on their media use before the lockdown in March 2020, during the strictest lockdown period (identified as March and April 2020), and in the subsequent period. For our participants, WhatsApp was the most used platform for mediating personal relationships before the start of the pandemic. We were specifically interested in working adults (25–49 years of age) as a social group affected by lockdown measures and restrictions. The sample of participants was selected through a combination of snowball sampling (starting with personal contacts of the researchers) and purposive sampling, based on the team’s access to the public (Battaglia Citation2008).

We interviewed 10 participants from Barcelona, 10 participants from Milan and 10 participants from Groningen because we aimed at studying three urban contexts in different European countries (as context relevant to understanding the impact of WhatsApp technology) and because the three researchers had direct knowledge of these cities and access to the research participants. The governmental and social distancing measures in the three cities were different (International Labor Organization Citation2021). Milan had the strictest lockdown: for entire weeks most of its inhabitants could leave their homes only for emergency reasons and to go to supermarkets. Similarly, on 14 March 2020, Spain activated the “state of alarm”, which, amongst other severe measures, limited the movement of all Spanish citizens, including those of Barcelona. The Netherlands, and thus the city of Groningen, adopted a so-called “intelligent lockdown” that restricted travel, closed schools and childcare, as well as many other services, and expected people to stay at home as much as possible, but people were allowed to leave their homes as long as they maintained a 1.5-meters distance.

The interviews took place via Skype (Lo Iacono, Symonds, and Brown Citation2016), Google Meet, or Zoom and were conducted in the respondents’ native languages: Catalan, Spanish, Dutch, and Italian. Our interview guide was tested by means of pilot interviews and refined following several discussions among the team members. Interviewees were informed about the purpose of the study, their voluntary role in participating in the research, and the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses. With permission, interviews were recorded and transcribed. All included names are pseudonyms reflecting the interviewees’ nationalities and gender. All the original quotes in this research article were freely translated into English by the authors. We included participants from diverse households and with varied living arrangements—living alone, with families and/or kids, in smaller or larger housing, and in more provisional or more stable living settings, with various employments. There is a similar gender ratio across the sample of participants (50–50% in Milan and Barcelona and 60–40% in Groningen). See in the Appendix for the sociodemographic characteristics of the interviewees.

Collection of Visual Content

By the end of the interview, we asked the interviewee to scroll on WhatsApp for visual materials that according to them were most significant to the lockdown period. We asked for materials shared on WhatsApp either during the beginning of the lockdown (the first week that restrictions were put in place), one month after, or two months after (when participants are experiencing the lifting of certain measures); which we identified as the months with the strictest measures in the three countries. We asked for 9 items in total per interviewee: 3 per each time period. We opted for this non-news centric approach to collect content, to identify phatic sharing of “significant” visual content. We were interested in materials that our participants recollected because it was more representative and descriptive of their lives and experiences in that specific period of the pandemic, as well as being exceptional or unusual. The resulting dataset consists of 158 still images and 39 moving images (videos and GIFs) from 25 participants in total (who were granted permission to sample this visual content from their WhatsApp profiles), including visual memes, GIFs, videos, and personal photos. All materials offered by our participants are visual news-related items in the context of COVID-19; except a very small portion of materials consisting of a decontextualized comic, GIF, meme, screenshot, or video (11 from Barcelona; four from Milan; five from Groningen). Our dataset allows for thick descriptions that “reveal participants” views, feelings, intentions, and actions as well as the contexts and structures of their lives’ (Charmaz Citation2014, 14; Geertz Citation1973). in the Appendix includes a categorization of the different media types (Elleström Citation2019) in WhatsApp communication that were most significant for visual phatic news sharing under lockdown in March-June 2020.

Thematic Analysis

The research follows the scientific principles of qualitative data analysis and qualitative interviewing (Warren Citation2001; Charters Citation2003; Bryman Citation2016). Two methods of qualitative data analysis were employed: thematic analysis of interview data, and visual thematic analysis of collected (audio)visual content. We began our study with a certain research interest and set of general ideas to pursue and ask questions about our main phenomena (Charmaz Citation2014). Our pragmatic iterative approach (Tracy Citation2013) aims to distinguish categories within the research dataset that relate to the research focus and provide us with a basis for a theoretical understanding of the data (Bryman Citation2016). As such, we did not begin our study with a pre-conceived theory in mind, but began with an area of study and then allowed for abstract concepts to emerge from the data. The interviews and (audio)visual materials were analysed to capture an important essence of the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 83). This is an inductive approach which means that the themes identified are strongly connected to the data (Patton Citation1990 as cited in Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 83) and with conclusions based on specific observations. The resulting thematic maps showcase the main categories present in the dataset (see Appendix). The first, initial phase of the thematic analysis concentrated on analysing the visual item by itself, studying elements within the item/text (Rose Citation2016; Pauwels Citation2020), without the additional information of the participant or the interview. In the second phase of the analysis, the content was re-viewed and analysed with its contextual information and associated relations as uncovered in the analysis of the interview data (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane Citation2006).

Methodological Challenges

Researcher’s Access to Private WhatsApp Communication

Our research also raises methodological concerns for doing media and journalism studies when the change in the sector is rapid and access is often restricted. Especially when communication takes place in private group chats on WhatsApp, that the researcher is not a part of. On the one hand, the collection of visual content during the interview process is a suitable method for navigating participants’ concerns, albeit the collection of the number of items is limited. On the other hand, this is a useful approach for making what is implicit, explicit. As argued by Pink, et al. (Citation2006, cited in Bryman Citation2016, 458) visual research methods are usually not just visual, and go together with other qualitative research methods—as in our case, interviews—and the visual is almost always accompanied by the non-visual (i.e., words in the accompanying interview) as a form of expression, to gain deeper insights into platform practices, topics, actors and rules of participation.

(Non-)Availability of Visual Content

Our set of (audio)visual materials was collected at a noteworthy moment in time when interviewees could still actively remember or access which visual content affected them most. We noticed that this was already getting more difficult by May-June 2020 when we held our interviews, hence we did not ask for more than nine items in total per interviewee. There were further limitations to data availability and collection, which are telling of the significant albeit ephemeral quality of visual content. In the first place, emotional ones: the sharing of content was on a voluntary basis after our interviews had taken place, and the interviewers did not want to put extra pressure on participants, several of whom were going through exceptionally difficult times, with any follow-up requests for personal content. Second, technological ones: several of our participants in their personal life carried out practices of manually deleting (audio)visual materials from their phones and/or putting their phone settings to “not saving” WhatsApp images (to not clutter their phone, because their phone memory was limited, or because they simply were not interested in saving such materials). And finally, practical ones: during the period of data collection the researchers and the participants were all under the restrictions of lockdown and social distancing. Several of our participants used the practice of purposely “saving” videos, photographs, and GIFs or making screenshots for sentimental reasons or for the purpose to (re)share it. This aided our data collection of visual content from the period discussed in the interviews.

Visual Phatic News Sharing on WhatsApp during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain, Italy, and The Netherlands

Sense-Making in Pandemic Times

From March 2020 on, the pandemic lockdown was a total fact, and COVID-19 dominated the conversation. People were overcome with information and images related to public concerns around COVID-19. For our interviewees, WhatsApp was the most used platform before the start of the pandemic, and the use of the platform intensified during the first months of the lockdown. WhatsApp was used “24/7”. As Beatriz (43, female, Spain) who works as a nurse, narrates:

“During the lockdown I really noticed that we are very addicted to the mobile [phone] (…) Every day the first thing I take a look at is WhatsApp, and then Instagram. (…) WhatsApp is a hyper mega useful tool. Of course, it is a highly distracting tool too. But it is a very good communication tool. At work it is very useful because if you want to say something to everyone you can. (…) Of course, during the lockdown people send stupidities, but you can send audios, share contacts, videos…”

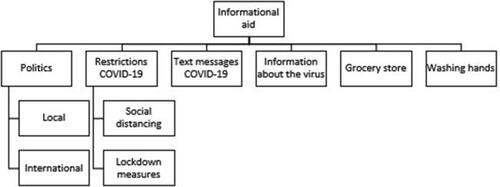

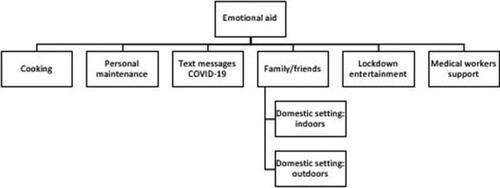

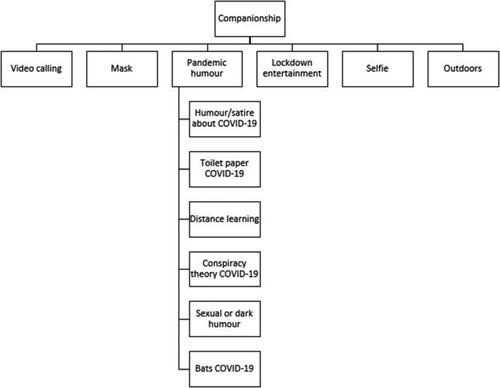

Previous research has underscored the complex mix of feelings around digital media use during the pandemic: as stressor, as resource, and as tool for coping (Karsay, Camerini, and Matthes Citation2023; Wolfers and Utz Citation2022). Based on our analysis, we outline main motivations for phatic sharing of visual content that is news-related—informational aid, emotional aid, and companionship (see the Appendix for the respective Thematic maps)—above all providing WhatsApp users with a sense of togetherness and sociability. Motivations range from sharing experiences from everyday life and showing care to coping strategies. We identified an increase towards sharing visual news-related content for emotional aid and sociability () over informational aid () as lockdowns continued. A significant portion of the visual content consists of phatic meta-commentary on the news—especially visual memes—shared by way of companionship ().

Sharing of Visual and Memetic Content

Visual memes were the main media type (see also ) that was shared, especially in groups, and content could be shared multiple times (for instance sent by a family member or friend, but then received from many other groups too). Similar to our interviewees, Carla (40, female, Italy) describes the first weeks of the lockdown as dominated by memes, and the following period with less memes, more conversations, and overall, less frequency of content. As Beatriz (43, female, Spain) explains: “People have calmed down [in comparison to the first wave] in terms of sending memes.” As Pedro (37, male, Spain) explains: “I’ve seen millions of memes (…) What I did was to share memes on a daily basis [and] I shared the memes in friend groups, exclusively.” Only a selection of content was further distributed, or not at all, like by Antonella (38, female, Italy) who received a lot of “silly” visual content that she did not share. Several interviewees describe motivations for sharing visual content about COVID-19 as similar to Carla, who when a meme makes her laugh shares it with others, but otherwise she does not. All interviewees described the initial “explosion” of COVID-19-related visual content, especially in memes, in this first period. Sander (32, male, the Netherlands) describes this experience in WhatsApp groups with friends from university:

“Funny enough, I’m in a few groups related to my studies (…) but (…) since the Corona crisis there is suddenly less communication there, because in the first weeks of the Corona crisis, that app [meaning the app group with friends, which he also calls the meme group] really exploded, and but now (…) that has decreased, and I have the idea that smaller groups are more busy… because those are the people you saw more often in your daily life, whilst those bigger app groups, of 30+ people, for some reason or other have become more silent, because those first week it was one big, how to say, it was a [uses expletive] mess.”

Across the dataset, a clear stand out is visual content about the restrictions during the pandemic and humour or satire about COVID-19—especially visual memes as (meta) commentary. It reflects information and responses to the limiting conditions or measures put into effect as a response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Such content could be shared also in a light-hearted, humourful way, to make fun of the situation by sharing memes or jokes, and in this way also as companionship during the situation. Content here branches out mainly into two directions: (1) social distancing measures and its results; and (2) lockdown measures and its real-life manifestations. Examples are sharing a photograph of the view from an apartment on an empty street, or a screenshot from the tv news featuring an empty city square; personal still images like sending a selfie wearing a mask to a friend or family member; visual memes (as a digital image, or e.g., Instagram screenshot of an image with text); but also, in the form of an informative video, such as sharing information on effectively wearing masks, by a participant who works as a nurse). Visual content about personal maintenance reflects the act or process of caring for oneself (physical looks): for example, a meme of a politician or a personal photograph of an interviewee with their “Corona hair”. The sharing of content from the outdoors is also considered meaningful, both from the open air or away from human habitation (in nature). For instance, being able to do sports outside during lockdown, or spending time with some family and/or friends outside (e.g., children), whilst contact with other family members (e.g., grandparents) is restricted to media platforms like WhatsApp.

In Barcelona, Milan, and Groningen, a main pattern is the overall high number of visual memes and also personal photographs during the crisis period. These two media types were the most common, GIFs or Snapchats were less used for example. The use of visuals, such as GIFs was already common amongst WhatsApp users before the pandemic, but the use of short videos increased a lot in Spain during this period. The content that was typically shared was funny or humorous content that make fun of exceptional circumstances, and it was shared across the board with people who our interviewees considered more or less close to them, in one-one-chats, small groups, as well as large groups. The considerable increase in the use of specific visual content can be partially explained by the threatening deadly context of the pandemic and by social isolation. This is noticeable, for instance, because most of the videos are focused on narrating daily family experiences under lockdown, e.g., jokes between partners, the use of toilet paper, and staying at home during the pandemic crisis.

Some interviewees actively address others on WhatsApp in relation to or by means of visual content, for instance, to convey messages on how to not add to the spread of fake news, or how to follow the Corona regulations. As Maaike (42, female, the Netherlands) explains:

“What [content] I have shared is mainly social behaviour, say how … why one adheres well to the rules and the other does not, for example, so that. Yes… one more thing… Yes…, that video from the hospitals in Italy.”

Sharing of content is also related to differences in life stages (Matassi, Boczkowski, and Mitchelstein Citation2019), such as media literacy, or cultural differences. Like Antonella (38, female, Italy) says: “It happens that I often do not know what to answer to my mum’s memes. We have different cultural references; we don’t understand it together. While with friends it is a different story.” Visual memes can sometimes only be understood by members of a certain cultural community or specific region. Whilst a lot of Dutch content is also in the English language, Italian and Spanish visual content is more for native audiences.

News as a Social Trigger

The visual content shared on WhatsApp is not important to convey news as information. The content includes few news items and it is not distributed as news. What is shared through visual content is feelings and experiences around news as it relates to people’s daily lives. News (for instance, the recurrent press conference) is the social trigger, and then individuals add their personal experiences. This is the kind of hybridity that happens on WhatsApp during the pandemic. Whilst news and journalism may be shared, as Lisa (49, female, the Netherlands) describes there is an expectation that people will have read or seen the news:

“I kind of assume that everyone does that themselves, follows it themselves and that I’m not going to say: oh, have you read this… or that…. Yeah, you know, most people are adults and we can do that ourselves? I’m not going to send it to my son either, he will talk about it at school or with us after the press conferences. I personally assume that everyone watches the press conferences and is aware of it. So, then I’m not going to text or I think no… they are not… They are all adults; they would have seen that themselves.”

Private and Local Content

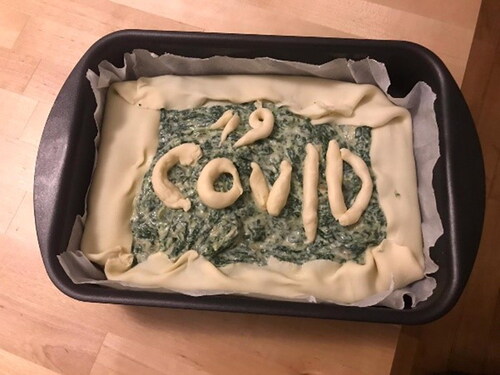

Our research study demonstrates how phatic sharing of visual content that is news-related occurs across different scales of public and private communication: from the very private or local to the national and global. However, it is shared in similar ways as phatic communication using the WhatsApp platform. Through visual phatic news sharing, these forms of content all link the macro event of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was a total fact, to the impact it had on the individual’s daily life. Shared visual images represent interviewees’ everyday life during lockdown, across different geographic scales. First, it includes very private or local content shared via WhatsApp. For example, an image of a participant of their children playing outside during lockdown, or an image or visual meme of baking a cake at home during lockdown. is a photograph of a cake most significant to Maddalena (41, female, Italy); it literally spelling out “COVID-19”. It is a personal photograph taken in the private and domestic context of the home. The primary reason for using WhatsApp for Maddalena—beyond work—is the exchange of greetings, hugs, kisses, photos, and visual memes: it is not so much about exchanging ideas, but rather about exchanging content. This image refers to the practice of baking at home during the pandemic. It became a global popular pastime, distraction, and way of emotionally coping—as well as a popular strategy for news avoidance (Ytre-Arne and Moe Citation2021).

National and Global Content

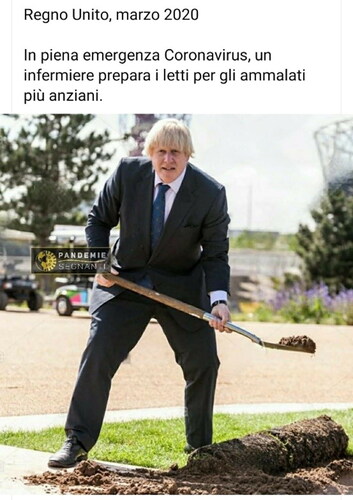

Second, shared visual images include national and global content shared via WhatsApp: like making fun of government measures in visual memes showing and making fun of hoarding groceries and toilet paper. is a visual meme from Italy, making fun of Boris Johnson’s health policies during the pandemic and the cut of funding on the NHS, it is an example of dark humour about UK COVID-19 politics. Re-using an image of Johnson digging the earth with a shovel, the English translation of the accompanying text reads: “UK, March 2020. In full COVID-19 emergency, a nurse is preparing beds for the eldest patients”. The visual meme went viral and was shared by our interviewees on WhatsApp, it also circulated massively on WhatsApp. Such content is an example of pandemic humour as companionship. Screenshots with humorous visual content taken from platforms like Twitter or other media platforms are also popular, with several reusing formal characteristics of news content, such as broadcast television. Such content underscores the global and widespread nature of the pandemic.

Specific news events during the lockdown are a main trigger for visual phatic news sharing. For instance, in multiple towns in Italy, people stuck at home during strict lockdown started playing and singing from their balconies, and several pictures and videos of or related to these spontaneous creative practices went viral. In this context, research by Denisova (Citation2019, 11) has recognised the importance of visual content, such as memes for “people to come together to express their ideas and opinions in a short-term, immediate perspective with the close reliance on the context” pointing out that visual media types like memes provide us with “the ability to connect the disconnected” through cultural references and their contextualization. As Jorge (29, male, Spain) explains: “There has been a difference in the content of the memes throughout the months. At the beginning, these [memes] were about the origin of the virus, about China, and afterwards about the political measures and how society has reacted to it, such as ‘I need to stay at home with my partner’.” Our analysis shows the very rapid change of these media forms across the different stages of the first lockdown, where each stage had its own particular type of short-term content, starting with the “novelty” of the pandemic, to the arrival of the COVID-19 virus in the interviewees’ own respective countries and resulting surprise and fear, to lockdown measures (e.g., an overload of toilet paper memes) and changes in relations to restrictions.

Interviewees demonstrate personal preferences for certain media types. Writing in the text is regarded as possibly “trickier” (Marisol, 38, female, Spain: “It is very tricky to explain oneself on WhatsApp. I have dedicated a lot of time to think about the correct verbs and the like, to not piss off people”). Visual media types are considered the most effective for being expressive. Visuals are regarded as more easily offering more experience, for example, Matthijs (27, male, the Netherlands) describes: “Yes of course it all depends a lot on the topic of the conversation. Having a chat with friends, then we also make jokes, and indeed send some GIFs to each other to add a little more experience [in Dutch: beleving] to the text.” Visual content is, therefore, a “mediator of emotional support” as well as a means of being able to be oneself “more fully” (Miller, et al. Citation2021). Importantly, the use of visual forms of communication has significantly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis (Murru and Vicari Citation2021). This can be understood as part of a shift towards more visual modes of communicating about current affairs in general (Bebić and Volarevic Citation2018). Notably, it also points to the important role that visual forms, such as photographs, videos, and visual memes, can play as cultural tools and in the creation of new forms of discourses (Al Zidjaly Citation2017, 591).

Conclusions from our thematic analysis reveal that the visual has become more central in news-related content and communication during lockdown, and the hybridity of such news-related content has the following consequences. In this particular crisis period, we observed (1) more humour and dark humour in visual news-related content; (2) more sharing of visual news-related content in groups, with an “explosion” of such content in the first weeks (before a general “fatigue” around news and screens set in) (3) the sharing of visual news-related content to search for support and companionship and (4) the sharing of visual news-related content across different scales of public and private communication: from the very private or local to the national and global. Our analysis reveals insights about the hybridity of news-related and personal content in WhatsApp communication during the fearful pandemic times, particularly in light of the shift to more visual communication forms. This hybridity blurs the borders between the public and the private spheres. According to Papacharissi, the merit of digital media—such as WhatsApp—is convergence, not only of multimedia content, but also of techno-social mediated practices: “convergence simultaneously melds and blurs traditional boundaries among media, and among audiences of different media, audiences and publics, citizens and consumers, consumers and producers” (2010, 52). In this convergent sphere, individuals combine the social, the cultural, the political, and the commercial, paving the way for new forms of civic engagement. To us, WhatsApp has become one of these meso-spaces (Kligler-Vilenchik and Tenenboim Citation2020) where people, through their involvement in news-related processes, experience these new forms of civic engagement.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this article, we explored how visual media content shared in personal WhatsApp interactions functions as phatic news during the first strict lockdown months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, our study shows how visual images as a hybrid form of communication blur the boundaries between private life and public concerns presented on the news. Recent studies have pointed out how important it is to understand more deeply the phatic dimension of communication, as media audiences today use social media platforms, including WhatsApp, first and foremost for sociability and to sustain social interactions, with “positive content” generating more interactions than “negative content” like health misinformation (Berriche and Altay Citation2020). Phatic communication using visual news-related content is about enacting sociability (Miller Citation2008) and an act of caring, rather than serving an informational news function (Swart, Peters, and Broersma Citation2019; Duffy and Ling Citation2020). Our results point to the increasingly significant role of visual images (Rose Citation2016) in phatic news sharing. Visual images are an especially effective medium for the expression of emotions, affection, and care as scholars Miller, et al. (Citation2021, 185) argue, and whilst visuals should not be understood as oppositional to speech and writing, visuals are “sometimes surpassing” the capacities of those other media (Miller, et al. Citation2021, 195). Our results reveal deeper understanding of motivations that underlie individuals’ engagement with WhatsApp as a digital space for sharing varied visual forms of public and private news-related content. Rather than sharing the news, which we understand as “the daily reporting of the large and small events that either challenge or affirm our concepts of normalcy” (Sjøvaag Citation2015, 101), motivations for sharing visual content on WhatsApp are to achieve “phatic” forms of sociability (including informational aid, emotional aid, and companionship) through which people make sense of the unfolding events and draw a sense of security as they confront the uncertain reality of the pandemic.

Our study addresses a gap in journalism studies in researching news-related content and visual content like photographs, visual memes and videos (for exceptions see Al-Rawi, Al-Musalli, and Rigor Citation2022; MacDonald Citation2021) from user perspectives. We investigate visual communication as an emerging force in the “semi-private” digital communication space of WhatsApp. Our conclusions provide insights into how WhatsApp offers people a space to deal with becoming a news subject during the COVID-19 pandemic. WhatsApp affords interviewees an online space to negotiate events impacting their own lives—narrated as a constant stream of “breaking-news” style crisis information (Miller and Volkmer Citation2006)—on an extreme level during the first crisis months. Our key finding is that WhatsApp users’ appropriate news (the reception of which is typically via other channels, such as traditional news outlets) and shape it into different visual forms which can be attractively shared on WhatsApp as phatic communication, during such a terrifying period of time in their lives. News here is the social trigger, and then individuals added their personal experiences. This sharing of visual news-related content on WhatsApp functions as a sense-making practice and vehicle for ontological security (Giddens Citation1991; Kinnvall and Mitzen Citation2020) in dealing with the fearful and unsettling crisis situation. We argue that the visual is further impacting the way people discuss around news on WhatsApp as an online meso news-space.

Visual phatic news sharing on WhatsApp during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands, Italy, and Spain combines public and private aspects, especially how people address issues of public concern through their private WhatsApp communication (Tenenboim and Kligler-Vilenchik Citation2020, 578). Such visual content includes personal photographs, visual memes, and videos that reveal a range of private and public forms of communication; from family snapshots to global viral videos that have turned into a meme. We argue that these visual materials function as devices to make sense of the COVID-19 crisis situation by linking the macro-level event of the pandemic to practices of individuals’ everyday lives. As part of modern media audiences’ continuing move towards private communication channels and social media platforms (Newman, et al. Citation2021), phatic news sharing and discussing news-related content on WhatsApp is becoming more about sharing visuals; because visuals are especially suitable to the private communication space of WhatsApp. The visual images shared via WhatsApp are a hybrid form of communication that blur the boundaries between private life and public concerns presented on the news—the visual is blurring these categories.

Our conclusions are based on specific observations of sharing visual content on WhatsApp as phatic news sharing, to explore and explain opportunities and challenges for the use of (audio)visual content—from visual memes and screenshots to viral videos—as shifting forms for sharing news, in the data-driven media production age. The use of the WhatsApp platform collapses both private and public communication. The hybridity of visual phatic news sharing leads to the collapse of pre-existing neat categories, such as “information” or “entertainment”. Whilst practices of deliberately sharing humorous but fake imagery and videos challenge classic Habermassian ideals of informed citizenship (Habermas, Burger, and Lawrence Citation1989), when sharing visual news-related content on the platform the social aspect is most important, even in potentially life-threatening situations like a pandemic. Humour memes about government restrictions and measures blur the boundaries of discussing news, for instance by making fun of it, with demonstrations of care and friendship. The visual content on WhatsApp cannot easily be delineated as either news/information or entertainment. The content suggests that these are not two discrete categories that exclude each other, but rather two components that simultaneously characterize the visual material we analysed. The hybridity of the visual content forces us to question these typologies. Such practices combine public and private aspects, especially WhatsApp users’ addressing issues of public concern through their private communication during the first strict lockdown months. This raises new questions about the boundaries of what can be considered as “news”, “information”, and “entertainment” (Edgerly and Vraga Citation2020). Furthermore, it raises questions about how media audiences make sense of “news” today in their use of certain visual media types that afford multimodal storytelling (Elleström Citation2019). Further research into visual phatic news sharing on WhatsApp can contribute to a broadening understanding of what media audiences consider “news” and the increasingly active role WhatsApp users play here “in the sense of deciding what matters to them” (Tenenboim and Kligler-Vilenchik Citation2020, 580) when they share, discuss and appropriate news-related content on the platform.

Acknowledgements

The researchers are very grateful to all the interviewees who participated in this research pro bono during an exceptional and extremely difficult time. The authors would like to thank Silke Wester and Kerttu Kopliste for their research assistance during data collection and data categorization, respectively. Joëlle Swart and Qinfeng Zhu are thanked for their useful commentary on an earlier draft of this research publication.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this context, WhatsApp is relatively under-employed as a tool for research (Kümpel Citation2022; Kaufmann and Peil Citation2020).

References

- Al Zidjaly, N. 2017. “Memes as Reasonably Hostile Laments: A Discourse Analysis of Political Dissent in Oman.” Discourse & Society 28 (6): 573–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926517721083

- Al-Rawi, A., A. Al-Musalli, and A. P. Rigor. 2022. “Networked Flak in CNN and Fox News Memes on Instagram.” Digital Journalism 10 (9): 1464–1481.

- Battaglia, M. P. 2008. “Purposive Sample.” In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods, edited by P. J. Lavrakas, 645–647. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Bebić, D., and M. Volarevic. 2018. “Do Not Mess with a Meme: The Use of Viral Content in Communicating Politics.” Communication and Society 31 (3): 43–56.

- Berriche, M., and S. Altay. 2020. “Internet Users Engage More with Phatic Posts than with Health Misinformation on Facebook.” Palgrave Communications 6 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0452-1

- Boczkowski, P. J., M. Matassi, and E. Mitchelstein. 2018. “How Young Users Deal with Multiple Platforms: The Role of Meaning-Making in Social Media Repertoires.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 23 (5): 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy012

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryman, A. 2016. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. London: SAGE.

- Charters, E. 2003. “The Use of Think-Aloud Methods in Qualitative Research. An Introduction to Think-Aloud Methods.” Brock Education 12 (2): 68–82.

- Costa, E., M. Esteve del Valle, and B. Hagedoorn. 2022. “Scalable Co-Presence: WhatsApp and the Mediation of Personal Relationships during the Covid-19 Lockdown.” Social Media + Society 8 (1): 1–10.

- De Gournay, C., and Z. Smoreda. 2017. “Communication Technology and Sociability: Between Local Ties and ‘Global Ghetto’?” In Machines That Become Us: The Social Context of Personal Communication Technology, 57–70. Routledge.

- Denisova, A. 2019. Internet Memes and Society: Social, Cultural, and Political Contexts. Routledge.

- Druick, Z. 2009. “Dialogic Absurdity: TV News Parody as a Critique of Genre.” Television & New Media 10 (3): 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476409332057

- Duffy, A., and R. Ling. 2020. “The Gift of News: Phatic News Sharing on Social Media for Social Cohesion.” Journalism Studies 21 (1): 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2019.1627900

- Edgerly, S., and E. K. Vraga. 2020. “Deciding What’s News: News-Ness as an Audience Concept for the Hybrid Media Environment.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 97 (2): 416–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699020916808

- Ekström, M. 2000. “Information, Storytelling and Attractions: TV Journalism in Three Modes of Communication.” Media, Culture and Society 22 (4): 465–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/016344300022004006

- Elleström, L. 2019. Transmedial Narration. Palgrave Pivot.

- eMarketer. 2020. https://www.emarketer.com/

- Esteve del Valle, M., E. Costa, and B. Hagedoorn. 2022. “Network Shocks and Social Support among Spanish, Dutch, and Italian WhatsApp Users during the First Wave of the Covid-19 Crisis: An Exploratory Analysis of Digital Social Resilience.” International Journal of Communication 16 (20): 2126–2145.

- Feil, D. 1982. “From Pigs to Pearl Shells: The Transformation of a New Guinea Highlands Exchange Economy.” American Ethnologist 9 (2): 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1982.9.2.02a00050

- Fereday, J., and E. Muir-Cochrane. 2006. “Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (1): 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Gal, N. 2018. “Internet Memes.” In The SAGE Encyclopaedia of the Internet, 529–530. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Geertz, C. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Goh, Debbie, Richard Ling, Liuyu Huang, and Doris Liew. 2019. “News Sharing as Reciprocal Exchanges in Social Cohesion Maintenance.” Information Communication and Society 22 (8): 1128–1144. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1406973

- Habermas, J., T. Burger, and F. G. Lawrence. 1989. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. MIT Press.

- International Labor Organization. 2021. “Country Policy Responses.” February 21. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/regional-country/country-responses/lang–en/index.htm

- Kantar. 2020. “Covid-19 Barometer: Consumer Attitudes, Media Habits and Expectations.” https://www.kantar.com/Inspiration/Coronavirus/COVID-19-Barometer-Consumer-attitudesmedia-habits-and-expectations

- Karapanos, E., P. Teixeira, and R. Gouveia. 2016. “Need Fulfilment and Experiences on Social Media: A Case on Facebook and WhatsApp.” Computers in Human Behavior 55: 888–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.015

- Karsay, K., A. L. Camerini, and J. Matthes. 2023. “COVID-19, Digital Media, and Health: Lessons Learned and the Way Ahead for the Study of Human Communication: Introduction.” International Journal of Communication 17 (8): 623–630.

- Kaufmann, K., and C. Peil. 2020. “The Mobile Instant Messaging Interview (MIMI): Using WhatsApp to Enhance Self-Reporting and Explore Media Usage in Situ.” Mobile Media & Communication 8 (2): 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157919852392

- Kinnvall, C., and J. Mitzen. 2020. “Anxiety, Fear, and Ontological Security in World Politics: Thinking with and beyond Giddens.” International Theory 12 (2): 240–256. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175297192000010X

- Kligler-Vilenchik, N., and O. Tenenboim. 2020. “Sustained Journalist-Audience Reciprocity in a Meso News-Space: The Case of a Journalistic WhatsApp Group.” New Media & Society 22 (2): 264–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819856917

- Kress, G. R. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. Routledge.

- Kümpel, A. S. 2022. “Using Messaging Apps in Audience Research: An Approach to Study Everyday Information and News Use Practices.” Digital Journalism 10 (1): 188–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1864219

- Lo Iacono, V., P. Symonds, and D. H. K. Brown. 2016. “Skype as a Tool for Qualitative Research Interviews.” Sociological Research Online 21 (2): 103–117. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3952

- MacDonald, S. 2021. “What Do You (Really) Meme? Pandemic Memes as Social Political Repositories.” Leisure Sciences 43 (1–2): 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1773995

- Malhotra, P. 2023. “Misinformation in WhatsApp Family Groups: Generational Perceptions and Correction Considerations in a Meso-News Space.” Digital Journalism 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2023.2213731

- Masip, P., J. Suau, C. Ruiz-Caballero, P. Capilla, and K. Zilles. 2021. “News Engagement on Closed Platforms. Human Factors and Technological Affordances Influencing Exposure to News on Whatsapp.” Digital Journalism 9 (8): 1062–1084. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1927778

- Matassi, M., P. J. Boczkowski, and E. Mitchelstein. 2019. “Domesticating WhatsApp: Family, Friends, Work, and Study in Everyday Communication.” New Media & Society 21 (10): 2183–2200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819841890

- Miller, D., L. Abed Rabho, P. Awondo, M. de Vries, M. Duque, P. Garvey, and L. Haapio-Kirke, et al. 2021. The Global Smartphone: Beyond a Youth Technology. UCL Press.

- Miller, D., E. Costa, N. Haynes, T. McDonald, R. Nicolescu, J. Sinanan, and J. Spyer,. et al2016. How the World Changed Social Media. UCL Press.

- Miller, T., and I. Volkmer, eds. 2006. News in Public Memory: An International Study of Media Memories across Generations. Peter Lang.

- Miller, V. 2008. “New Media, Networking and Phatic Culture.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14 (4): 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856508094659

- Mortensen, M., and C. Neumayer. 2021. “The Playful Politics of Memes.” Information, Communication and Society 24 (16): 2367–2377. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1979622

- Murru, M. F., and S. Vicari. 2021. “Memetising the Pandemic: Memes, COVID-19 Mundanity and Political Cultures.” Information, Communication and Society 24 (16): 2422–2441. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1974518

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Schulz, S. Andi, C. T. Robertson, and R. K. Nielsen. 2021. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021. 10th ed. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Accessed February 5, 2023. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2021-06/Digital_News_Report_2021_FINAL.pdf

- O’Hara, K. P., M. Massimi, R. Harper, S. Rubens, and J. Morris. 2014. “Everyday Dwelling with WhatsApp.” In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, 1131–1143.

- Papacharissi, Z. 2010. A Private Sphere: Democracy in a Digital Age. Polity.

- Patton, M. Q. 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. SAGE.

- Pauwels, L. 2020. “An Integrated Conceptual and Methodological Framework for the Visual Study of Culture and Society.” In The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods, edited by L. Pauwels and D. Mannay, 15–36. London, UK: SAGE.

- Pink, S. 2006. “Visual Methods.” In Qualitative Research Practice, edited by C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. F. Gubrium, and D. Silverman, 361–376. London, UK: SAGE.

- Rose, G. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. SAGE.

- Shifman, L., ed. 2014. “Unpacking Viral and Memetic Success.” In Memes in Digital Culture, pp. 65–97. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Shove, E., M. Pantzar, and M. Watson. 2012. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes. SAGE.

- Sjøvaag, H. 2015. “Hard News/Soft News: The Hierarchy of Genres and the Boundaries of the Profession.” In Boundaries of Journalism, 101–117. Routledge.

- Swart, J., C. Peters, and M. Broersma. 2018. “Shedding Light on the Dark Social: The Connective Role of News and Journalism in Social Media Communities.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4329–4345. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818772063

- Swart, J., C. Peters, and M. Broersma. 2019. “Sharing and Discussing News in Private Social Media Groups: The Social Function of News and Current Affairs in Location-Based, Work-Oriented and Leisure-Focused Communities.” Digital Journalism 7 (2): 187–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1465351

- Tenenboim, O., and N. Kligler-Vilenchik. 2020. “The Meso News-Space: Engaging with the News between the Public and Private Domains.” Digital Journalism 8 (5): 576–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1745657

- Tracy, S. J. 2013. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell.

- Valeriani, A., and C. Vaccari. 2018. “Political Talk on Mobile Instant Messaging Services: A Comparative Analysis of Germany, Italy, and the UK.” Information Communication and Society 21 (11): 1715–1731. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1350730

- Warren, C. 2001. “Qualitative Interviewing.” In Handbook of Interview Research, edited by J. F. Gubrium and J. A. Holstein, 83–102. SAGE.

- Wolfers, L. N., and S. Utz. 2022. “Social Media Use, Stress, and Coping.” Current Opinion in Psychology 45: 101305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101305

- Ytre-Arne, B., and H. Moe. 2021. “Doomscrolling, Monitoring and Avoiding: News Use in COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown.” Journalism Studies 22 (13): 1739–1755. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1952475

- Zhang, J. S., B. Keegan, Q. Lv, and C. Tan. 2021. “Understanding the Diverging User Trajectories in Highly-Related Online Communities during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Vol. 15, 888–899.

Appendices

Table A1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the interviewees (10 Spain, 10 Italy, and 10 The Netherlands).

Table A2. Most significant media types in visual phatic news sharing on WhatsApp.