ABSTRACT

Fruit and vegetables (F&V) are nutritionally important for human health, and their perishability means that they are particularly vulnerable to supply chain delays. Ireland is a net importer of F&V. Brexit potentially heightens food system vulnerabilities for Ireland. Mapping is used to visualize the diversity of Ireland’s F&V supply across four regions of Europe and the UK. It appears that Ireland is highly reliant on the UK for F&V imports. However, when fresh potato imports, which contribute a small portion of Ireland’s potato consumption, are excluded from the analysis, Western Europe is more important for vegetable imports, and a significant supplier of other fresh food types. Options to build local food system resilience are discussed for Ireland. A graphical representation is a useful approach to investigate the impact of food system vulnerabilities and shocks such as Brexit.

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

Fruit and vegetables (F&V) are nutritionally important for human health, and the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted vulnerabilities in global supply chains (Garnett et al., Citation2020). As a result, there is heightened public interest in food security, nutrition and health. F&V are fresh foods prone to perish and spoil, and shorter supply chains support the movement of goods quickly. Ireland is a net importer of F&V. The UK is the main trading partner (Conefrey et al., Citation2018), due to proximity to Ireland. This means that the Irish economy is strongly exposed to the impacts of Brexit (McDonnell, Citation2018; Conefrey et al., Citation2018), including import tariffs, lengthier cross-border checks and changes to supply chain pathways. Mapping is a useful approach to visualize food imports and highlight where regional reliance and vulnerabilities may exist.

Food security is important to Ireland with a historical context of food shortages (Fry & Goodwin, Citation1997). Potatoes are an important staple food in Ireland and a component of many traditional Irish dishes (O’Sullivan & Byrne, Citation2020). Ireland produces a high proportion of the fresh produce consumed locally (Bord Bia, Citation2020), although an annual period known as the ‘hungry gap’ exists between the end of winter and mid-spring (Reilly et al., Citation2014; Cerrada-Serra et al., Citation2018; Reed & Keech, Citation2018) before the Irish climate warms up enough to support local food production. During the hungry gap Ireland relies more heavily on food imports, heightening food system vulnerability.

Diversifying supply chains is one way of building food system resilience by ensuring food supply can continue from a variety of sources (Tendall et al., Citation2015). Ireland also has substantial trade ties with Europe (Conefrey et al., Citation2018). For F&V imports, Ireland relies mainly on West and South Europe. To assess the diversity in Ireland’s F&V supply chain, data are summarized and mapped to quantify and visually compare Ireland’s imports of vegetables. Four EU regions and the UK are reviewed.Footnote1

INTERPRETATION OF THE GRAPHIC

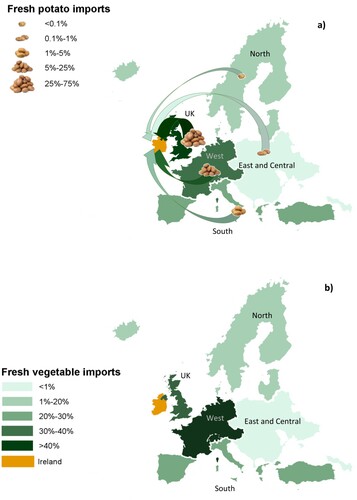

At an aggregate level the data () indicate that Ireland is most reliant on the UK for vegetables (124,019 tonnes imported). a shows that the UK, most proximate to Ireland, is the most important vegetable trading partner and most important potato trading partner. However, the ‘Potato Effect’ can be seen when potatoes are excluded from vegetable imports (b). The difference in the graphics highlight that for vegetables excluding potatoes, Ireland has a greater reliance on West Europe (). This suggests that the impact of Brexit on Ireland’s F&V imports will largely impact a single food crop: potatoes. also highlights the importance of West Europe to the supply of other products such as fruit, nuts and processed produce.

Figure 1. Potato effect, depicting imports of vegetables and potatoes from Europe, supported with graduated shading and flow pathways. Ireland is reliant on West Europe for vegetable imports while the UK is a major supplier of potatoes. (a) all fresh vegetable imports; and (b) fresh vegetable imports, excluding potatoes.

Table 1. Quantity of imported fruits and vegetables (tonnes) into Ireland, 2020, across region and food type.

Ireland needs to build resilience either by looking to other regions for the supply of potatoes (e.g., West Europe) or efforts need to be taken to increase local production. This should focus on potatoes as well as other F&V, and may be achieved through controlled environment growing, processing, packaging and cold chain storage technologies that encourage local production and diverse supply chains. Ireland has already seen promising growth in national potato production, which increased by 40%, up from 273,000 tonnes in 2018 to 382,000 tonnes in 2019 (Central Statistics Office, Citation2020). Only 13% of Ireland’s potatoes are now imported from the UK, and this represents a notable effort to address food supply vulnerabilities posed by Brexit.

METHODOLOGY AND DATA

Data on Ireland’s imported horticulture products in 2020, categorized by Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) code (Eurostat, Citation2013), obtained from the Central Statistics Office for Ireland, were used as the primary data source. SITC codes were further categorized into the four food categories: Vegetables; Potatoes; Fruit and nuts; and Processed produce. The weight of imported vegetables/potatoes as a percentage of the total imports of that food categorized by region was calculated in Excel and then imported into ArcMap 10.5, where they were joined to shapefile data and mapped to display food flows (depicted by icons and arrows) and regional imports of vegetables and potatoes.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Europe is made up of four regions. North Europe includes Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway and Sweden. South Europe includes Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, San Marino, Spain and Turkey. Central and East Europe includes Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, San Marino, Slovakia, Slovenia, Serbia, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Moldova. West Europe includes Andorra, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, Netherlands, Switzerland, the UK and Ireland (which was excluded for the purposes of this analysis).

REFERENCES

- Bord Bia. (2020). Irish horticulture industry. https://www.bordbia.ie/industry/irish-sector-profiles/irish-horticulture-industry/

- Central Statistics Office. (2020). Area, yield and production of crops. https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/aypc/areayieldandproductionofcrops2019/

- Cerrada-Serra, P., Moragues-Faus, A., Zwart, T. A., Adlerova, B., Ortiz-Miranda, D., & Avermaete, T. (2018). Exploring the contribution of alternative food networks to food security. A comparative analysis. Food Security, 10(6), 1371–1388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-018-0860-x

- Conefrey, T., O’Reilly, G., & Walsh, G. (2018). Modelling external shocks in a small open economy: The case of Ireland. National Institute Economic Review, 244, R56–R63. https://doi.org/10.1177/002795011824400115

- Eurostat. (2013). Glossary: Standard international trade classification (SITC). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Standard_international_trade_classification_(SITC)

- Fry, W. E., & Goodwin, S. B. (1997). Resurgence of the Irish potato famine fungus. Bioscience, 47(6), 363–371. https://doi.org/10.2307/1313151

- Garnett, P., Doherty, B., & Heron, T. (2020). Vulnerability of the United Kingdom’s food supply chains exposed by COVID-19. Nature Food, 1(6), 315–318. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0097-7

- McDonnell, C. (2018). Brexit import analysis. Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Service, Economic Division. https://igees.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Brexit-Import-Analysis-by-Cliona-McDonnell-Department-of-Finance.pdf

- O’Sullivan, M. G., & Byrne, D. V. (2020). Nutrition and health, traditional foods and practices on the island of Ireland. In S. Braun, C. Zübert, D. Argyropoulos, & F. J. C. Hebrard (Eds.), Nutritional and health aspects of food in Western Europe (pp. 41–63). Elsevier.

- Reed, M., & Keech, D. (2018). The ‘hungry gap’: Twitter, local press reporting and urban agriculture activism. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 33(6), 558–568. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170517000448

- Reilly, K., Valverde, J., Finn, L., Rai, D. K., Brunton, N., Sorensen, J. C., Sorensen, H., & Gaffney, M. (2014). Potential of cultivar and crop management to affect phytochemical content in winter-grown sprouting broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 94(2), 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.6263

- Tendall, D. M., Joerin, J., Kopainsky, B., Edwards, P., Shreck, A., Le, Q. B., Kruetli, P., Grant, M., & Six, J. (2015). Food system resilience: Defining the concept. Global Food Security, 6, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2015.08.001